Abstract

Background and Objectives

Hippocampal volume (HV) atrophy is a well-known biomarker of memory impairment. However, compared with β-amyloid (Aβ) and tau imaging, it is less specific for Alzheimer disease (AD) pathology. This lack of specificity could provide indirect information about potential copathologies that cannot be observed in vivo. In this prospective cohort study, we aimed to assess the associations among Aβ, tau, HV, and cognition, measured over a 10-year follow-up period with a special focus on the contributions of HV atrophy to cognition after adjusting for Aβ and tau.

Methods

We enrolled 283 older adults without dementia or overt cognitive impairment in the Harvard Aging Brain Study. In this report, we only analyzed data from individuals with available longitudinal imaging and cognition data. Serial MRI (follow-up duration 1.3–7.0 years), neocortical Aβ imaging on Pittsburgh Compound B PET scans (1.9–8.5 years), entorhinal and inferior temporal tau on flortaucipir PET scans (0.8–6.0 years), and the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (3.0–9.8 years) were prospectively collected. We evaluated the longitudinal associations between Aβ, tau, volume, and cognition data and investigated sequential models to test the contribution of each biomarker to cognitive decline.

Results

We analyzed data from 128 clinically normal older adults, including 72 (56%) women and 56 (44%) men; median age at inclusion was 73 years (range 63–87). Thirty-four participants (27%) exhibited an initial high-Aβ burden on PET imaging. Faster HV atrophy was correlated with faster cognitive decline (R2 = 0.28, p < 0.0001). When comparing all biomarkers, HV slope was associated with cognitive decline independently of Aβ and tau measures, uniquely accounting for 10% of the variance. Altogether, 45% of the variance in cognitive decline was explained by combining the change measures in the different imaging biomarkers.

Discussion

In older adults, longitudinal hippocampal atrophy is associated with cognitive decline, independently of Aβ or tau, suggesting that non-AD pathologies (e.g., TDP-43, vascular) may contribute to hippocampal-mediated cognitive decline. Serial HV measures, in addition to AD-specific biomarkers, may help evaluate the contribution of non-AD pathologies that cannot be measured otherwise in vivo.

Introduction

In Alzheimer disease (AD), β-amyloid (Aβ) and tau pathologies gradually accumulate in the brain,1 leading to neuronal loss, cognitive decline, and ultimately, dementia.2 According to postmortem studies, the extent of tau pathology correlates with morphometric changes, specifically in the hippocampus,3 and with premortem cognitive impairment,4 suggesting causal relationships between AD pathology, brain volume loss, and dementia. In the past 2 decades, neuroimaging techniques, including molecular PET5 and volumetric MRI, have made it possible to measure AD pathologic and morphological changes in living individuals. Early accumulation of both Aβ and tau pathologies have been detected in clinically normal (CN) older adults,6 defining a preclinical stage of AD preceding symptomatic AD.7 Previous MRI studies demonstrated close associations between the regional patterns of tau deposition and atrophy.8 In CN older adults, this association is mainly observed in the (medial) temporal lobe,9 where the origin of tau neurofibrillary tangles has been identified.10 Furthermore, cognitive decline in CN adults is more closely associated with AD pathology, specifically tau biomarkers, than with volumetric measures9,11; and longitudinal studies have shown the rate of tau accumulation to be predictive of both cognitive decline6 and rates of volume loss.12 There is thus good evidence of an association between AD pathology and brain atrophy.

However, brain atrophy, including in the hippocampus, is also observed in the context of non-AD pathologies, such as TDP-43,13-15 vascular16 lesions, or primary age-related tauopathy (PART).17 Although TDP-43 cannot yet be imaged in vivo, increasing evidence suggests that non-AD pathologies contribute to age-related cognitive decline, both in isolation and in combination with AD pathology, making volumetric data difficult to interpret without specific analyses disentangling the respective contributions of longitudinal amyloid and tau accumulation to explain the association between progressive atrophy to cognitive decline.

To provide an insight into the complexity of age-related neuropathologies, we aimed to observe the temporal sequence of changes in pathologic and volumetric biomarkers and evaluate their synergistic or independent contributions to cognitive decline. Determining the typical sequence of pathologic and volumetric changes in the medial temporal lobe and neocortex is important for understanding AD-related vs non–AD-related clinical progression. This in turn can inform the planning of therapeutic trials in the most appropriate individuals, using the best possible outcome measures.

Methods

Participants

In this report, we analyzed data from the Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS), a longitudinal study of aging conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA) with the following inclusion criteria6: age from 60 to 90 years, Global Clinical Dementia Rating = 0, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and Wechsler Logical Memory II delayed recall (LM) within 1 SD of education-adjusted norms (MMSE ≥27 and LM ≥11 if ≥16 years of education). Exclusion criteria included recent drug or alcohol abuse, head trauma, and serious medical or psychiatric condition (Geriatric Depression Scale >10/30). Annual consensus meetings evaluated progression to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia. Here, we report prospective observations collected from January 1, 2010, to April 1, 2020, in 128 individuals who had at least 2 flortaucipir (FTP) and 2 Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET scans, assessing tau and Aβ pathology, and at least 2 brain MRI scans to evaluate longitudinal volumetric changes.

Study Design

The study design of HABS has been previously described in detail.6 In short, longitudinal data were acquired for PiB, MRI, and cognition from 2010. Because FTP was not available before 2013, the initial FTP was defined as “baseline” (timet = 0), and the terms “baseline FTPt = 0” and “initial FTPt = 0” are equivalent. The initial PiB (and MRI) sessions were acquired on average 3 years before baseline and are termed “initialt = −3,” with “baselinet = 0” referring to PiB or MRI at approximately the time of initial FTPt = 0. Participants had 2–4 FTP observations (median = 2), over a median follow-up of 2.1 years (0.8–6.0). Participants had 2–6 PiB observations (median = 3) over a median follow-up of 5.1 years (1.9–8.4), 2–5 MRI scans (median = 3) over a median follow-up of 4.8 years (1.3–7.0), and 4–9 annual cognitive evaluations (median = 8) over a median follow-up of 7.3 years (3.0–9.8). PiB, MRI, and cognition were thus evaluated both before and after baseline FTPt = 0, allowing us to distinguish between successive and concurrent changes between biomarkers.

Neuropsychological Evaluation

Participants in HABS are evaluated yearly with a battery of cognitive assessments, including tests of episodic memory, executive function, processing speed, and language. In this study, we evaluated cognition with the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (PACC5), an average of z-scored performances on 5 tests sensitive to cognitive decline in at-risk individuals6: LM, MMSE, Category Fluency (Animals, Names, Furniture), Digit-Symbol Coding, and the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, which uses 3 versions with different items, each version repeated every 3 years.18

Brain Imaging

Three-dimensional (3D) structural T1-weighted MRI scans were acquired using a Siemens 3 Tesla Tim Trio (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). T1 images were segmented and parcellated using FreeSurfer software (version 6.0). Hippocampal volume (HV) and total cortical volume (CV), adjusted for intracranial volumes, were used as proxies for allocortical and neocortical atrophy, respectively. Precuneus thickness was also tested for neocortical atrophy; and the volume of white matter hypointensities (WMHs) was used as a proxy for cerebrovascular burden. 11C-PiB and 18F-FTP tracers were synthesized onsite. PET images were acquired using a Siemens HR+ scanner. Both PiB and FTP measures were computed as standardized uptake value ratios (SUVrs, 4 frames of 5 minutes: 75–105 minutes for FTP; 40–60 minutes for PiB) using cerebral white matter as reference region, as in previous works.6 PET data were coregistered to each participant's base MRI. Partial volume correction was applied using geometric transfer matrix. PiB signal was extracted from a neocortical aggregate and FTP from entorhinal cortex (EC), an allocortical region, and inferior temporal (IT), a neocortical region where tau is commonly observed in preclinical AD.6 Primary analyses used continuous PET values. PiB groups (high and low) were used for figures and secondary analyses. PiB threshold was set at 0.72 SUVr (∼Centiloid = 25) using a Gaussian mixture model on the initial PiB data.

Statistics

Mixed-effect models with random intercept and time slope per participant predicting PACC, HV, WMH, FTP, and PiB were computed over time in separate models. Individual slopes of change were calculated by summing the estimated fixed and random effects of time. For PACC, PiB, and volume data, slopes were estimated over the entire follow-up (PACCt = −3 to t = +4, PiBt = −3 to t = +2, HVt = −3 to t = +2) and over shorter periods (referred to as PiBt = −3 to t = 0 before baseline and PiBt = 0 to t = +2 after baseline as in a study6). Cross-sectional measures and slope data were correlated and entered as predictors or outcomes in linear regressions evaluating the associations between PACC, HV, WMH, FTP, and PiB, and their respective slopes, covarying, age, education, sex, and APOE e4 genotype status. We did not correct for multiple comparisons to interpret the data, but we provided the threshold for correcting p-values using the Bonferroni method for each table of results. The results were summarized in a serial mediation model, providing evidence for sequential biomarker changes in preclinical AD and other age-related conditions. All possible indirect pathways between PiB, FTP, HV, and final PACCt = +4 scores were tested. Direct, indirect, and total effects were tested with a 5000-iteration bootstrap. All models were fit in MATLAB version 9.3 except mediations, which used R version 3.4.2 (Lavaan package).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board has approved the HABS protocol, and participants provided written informed consent before undergoing any procedures.

Data Availability

B.J. Hanseeuw and K.A. Johnson had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Request for data can be sent to the following email address: habsdata@mgh.harvard.edu.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Participants

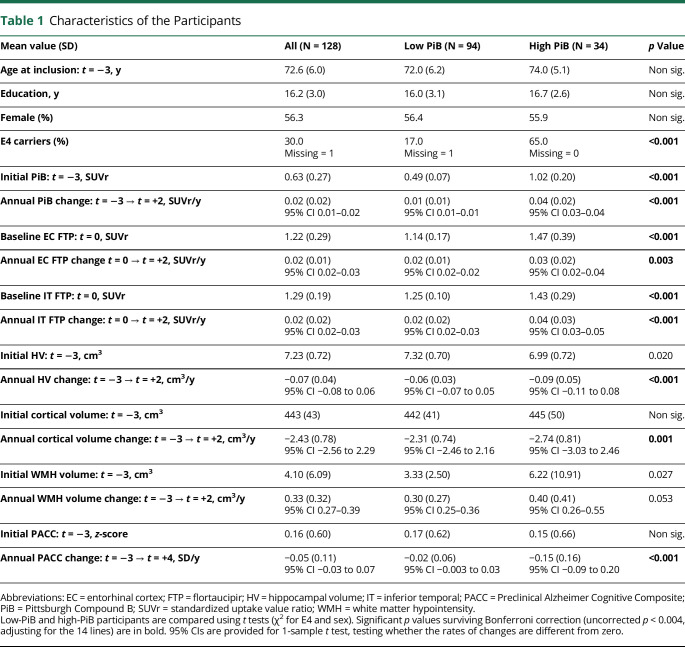

Table 1 provides the demographics, cognitive, and imaging data of the 128 participants. Based on the initial PiBt = −3 observation, 94 participants (73%) were classified as low-PiB and 34 (27%) were classified as high-PiB participants. Initial cognitive performance and demographics (age, sex, education) were not significantly different between groups, but high-PiB had lower initial HVt = −3 (p = 0.02), greater WMHt = −3 (p = 0.027), and greater baseline FTPt = 0 (p < 0.001) than low-PiB participants. During the follow-up, WMH, PiB, and FTP demonstrated significant increase and HV, CV, and cognition significant decrease, including in the low-PiB participants only (see 95% CI for change data in Table 1). High-PiB participants had faster rates of change for all imaging markers (PiB, FTP, HV, CV, WMH) and faster cognitive decline than low-PiB participants. At the end of the study, 8 high-PiB participants (24%) had progressed to either MCI (n = 6) or AD dementia (n = 2), whereas all low-PiB participants remained CN.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants

| Mean value (SD) | All (N = 128) | Low PiB (N = 94) | High PiB (N = 34) | p Value |

| Age at inclusion: t = −3, y | 72.6 (6.0) | 72.0 (6.2) | 74.0 (5.1) | Non sig. |

| Education, y | 16.2 (3.0) | 16.0 (3.1) | 16.7 (2.6) | Non sig. |

| Female (%) | 56.3 | 56.4 | 55.9 | Non sig. |

| E4 carriers (%) | 30.0 Missing = 1 |

17.0 Missing = 1 |

65.0 Missing = 0 |

<0.001 |

| Initial PiB: t = −3, SUVr | 0.63 (0.27) | 0.49 (0.07) | 1.02 (0.20) | <0.001 |

| Annual PiB change: t = −3 → t = +2, SUVr/y | 0.02 (0.02) 95% CI 0.01–0.02 |

0.01 (0.01) 95% CI 0.01–0.01 |

0.04 (0.02) 95% CI 0.03–0.04 |

<0.001 |

| Baseline EC FTP: t = 0, SUVr | 1.22 (0.29) | 1.14 (0.17) | 1.47 (0.39) | <0.001 |

| Annual EC FTP change t = 0 → t = +2, SUVr/y | 0.02 (0.01) 95% CI 0.02–0.03 |

0.02 (0.01) 95% CI 0.02–0.02 |

0.03 (0.02) 95% CI 0.02–0.04 |

0.003 |

| Baseline IT FTP: t = 0, SUVr | 1.29 (0.19) | 1.25 (0.10) | 1.43 (0.29) | <0.001 |

| Annual IT FTP change: t = 0 → t = +2, SUVr/y | 0.02 (0.02) 95% CI 0.02–0.03 |

0.02 (0.02) 95% CI 0.02–0.03 |

0.04 (0.03) 95% CI 0.03–0.05 |

<0.001 |

| Initial HV: t = −3, cm3 | 7.23 (0.72) | 7.32 (0.70) | 6.99 (0.72) | 0.020 |

| Annual HV change: t = −3 → t = +2, cm3/y | −0.07 (0.04) 95% CI −0.08 to 0.06 |

−0.06 (0.03) 95% CI −0.07 to 0.05 |

−0.09 (0.05) 95% CI −0.11 to 0.08 |

<0.001 |

| Initial cortical volume: t = −3, cm3 | 443 (43) | 442 (41) | 445 (50) | Non sig. |

| Annual cortical volume change: t = −3 → t = +2, cm3/y | −2.43 (0.78) 95% CI −2.56 to 2.29 |

−2.31 (0.74) 95% CI −2.46 to 2.16 |

−2.74 (0.81) 95% CI −3.03 to 2.46 |

0.001 |

| Initial WMH volume: t = −3, cm3 | 4.10 (6.09) | 3.33 (2.50) | 6.22 (10.91) | 0.027 |

| Annual WMH volume change: t = −3 → t = +2, cm3/y | 0.33 (0.32) 95% CI 0.27–0.39 |

0.30 (0.27) 95% CI 0.25–0.36 |

0.40 (0.41) 95% CI 0.26–0.55 |

0.053 |

| Initial PACC: t = −3, z-score | 0.16 (0.60) | 0.17 (0.62) | 0.15 (0.66) | Non sig. |

| Annual PACC change: t = −3 → t = +4, SD/y | −0.05 (0.11) 95% CI −0.03 to 0.07 |

−0.02 (0.06) 95% CI −0.003 to 0.03 |

−0.15 (0.16) 95% CI −0.09 to 0.20 |

<0.001 |

Abbreviations: EC = entorhinal cortex; FTP = flortaucipir; HV = hippocampal volume; IT = inferior temporal; PACC = Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite; PiB = Pittsburgh Compound B; SUVr = standardized uptake value ratio; WMH = white matter hypointensity.

Low-PiB and high-PiB participants are compared using t tests (χ2 for E4 and sex). Significant p values surviving Bonferroni correction (uncorrected p < 0.004, adjusting for the 14 lines) are in bold. 95% CIs are provided for 1-sample t test, testing whether the rates of changes are different from zero.

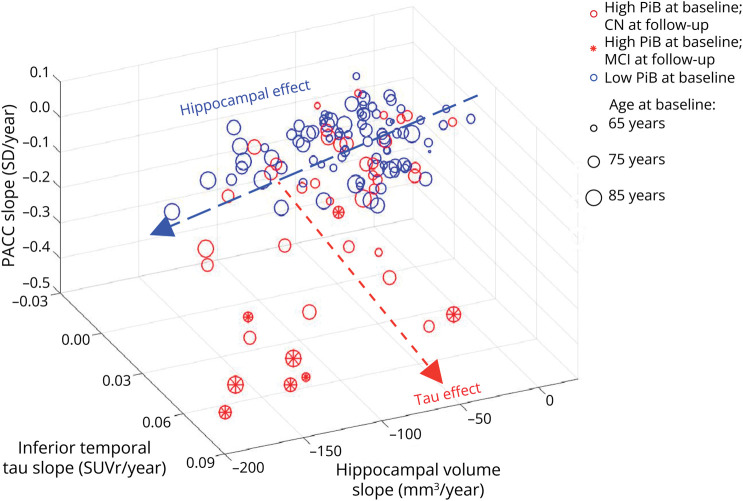

Correlation Between Baseline and Change Data

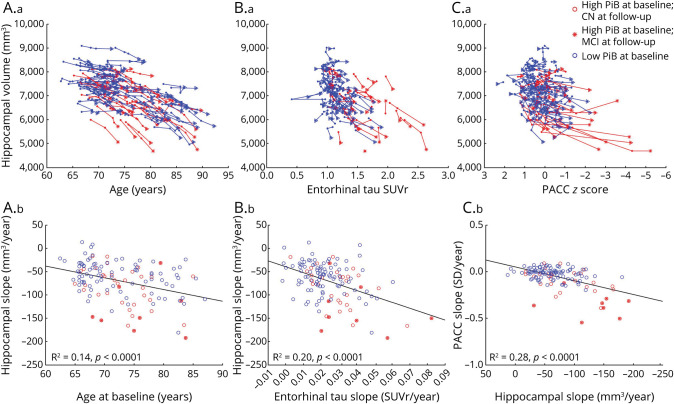

eTable 1 (links.lww.com/WNL/D224) provides Pearson's R2 correlations between PiB, FTP in EC and IT, HV, CV, WMH, and PACC scores. PACC change was most closely associated with IT FTP change (R2 = 0.30) and HV change (R2 = 0.28, Figure 1C). CV change was strongly associated with precuneus thickness change (R2 = 0.61), and to a lesser extent, with HV change (R2 = 0.15), but it was only weakly associated with change in cognition (R2 = 0.09), an association entirely explained by HV change. Therefore, we focused on HV change and did not include CV or precuneus thickness in subsequent analyses. WMH changes were associated with older ages and the initial volume of WMH. The association with change in cognition was weak after adjusting for age (R2 = 0.05), but independent of HV change.

Figure 1. Associations Between HV, Age, Entorhinal Tauopathy, and Cognition.

Spaghetti plots showing the longitudinal HV data plotted against (A.a) age, (B.a) entorhinal FTP data, and (C.a) PACC-5 data. Individuals who progressed to symptomatic AD (MCI or dementia) during the follow-up had fast hippocampal atrophy. (A.b, B.b, C.b) HV, entorhinal FTP, and PACC slope data are plotted against each other. All associations are significant, demonstrating that HV reduces in size with age, entorhinal tauopathy, and poorer cognition. eTable 1 (links.lww.com/WNL/D224) provides the correlations of HV slope with additional slope data. The 3 most significant ones are illustrated here. AD = Alzheimer disease; CN = clinically normal; FTP = flortaucipir; HV = hippocampal volume; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; PACC = Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite; PiB = Pittsburgh Compound B; SUVr = standardized uptake value ratio; WMH = white matter hypointensity.

Multiple Regressions Predicting Longitudinal Hippocampal Atrophy

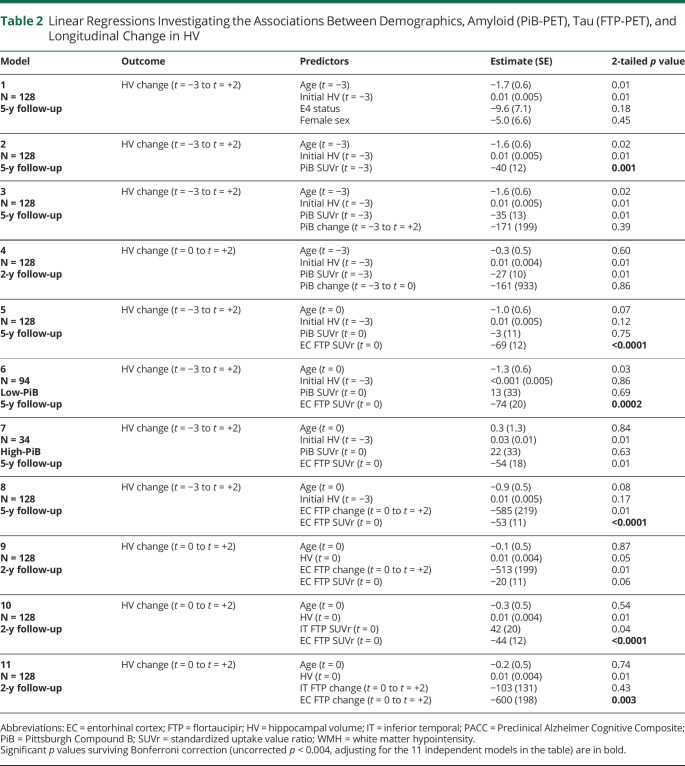

We next aimed to evaluate how these correlations were modified when adjusting for multiple biomarkers. We first focused our analyses on understanding the predictors of HV change (Table 2, Figure 1) and then the sequence of PiB and FTP change (Table 3, Figure 2). We did so because these were the predictors most strongly correlated with PACC change. Focusing on the predictors of HV was also motivated by the fact that HV may reflect both AD and non-AD pathology, such as limbic age-related TDP43 encephalopathy (LATE) or PART.

Table 2.

Linear Regressions Investigating the Associations Between Demographics, Amyloid (PiB-PET), Tau (FTP-PET), and Longitudinal Change in HV

| Model | Outcome | Predictors | Estimate (SE) | 2-tailed p value |

| 1 N = 128 5-y follow-up |

HV change (t = −3 to t = +2) | Age (t = −3) Initial HV (t = −3) E4 status Female sex |

−1.7 (0.6) 0.01 (0.005) −9.6 (7.1) −5.0 (6.6) |

0.01 0.01 0.18 0.45 |

| 2 N = 128 5-y follow-up |

HV change (t = −3 to t = +2) | Age (t = −3) Initial HV (t = −3) PiB SUVr (t = −3) |

−1.6 (0.6) 0.01 (0.005) −40 (12) |

0.02 0.01 0.001 |

| 3 N = 128 5-y follow-up |

HV change (t = −3 to t = +2) | Age (t = −3) Initial HV (t = −3) PiB SUVr (t = −3) PiB change (t = −3 to t = +2) |

−1.6 (0.6) 0.01 (0.005) −35 (13) −171 (199) |

0.02 0.01 0.01 0.39 |

| 4 N = 128 2-y follow-up |

HV change (t = 0 to t = +2) | Age (t = −3) Initial HV (t = −3) PiB SUVr (t = −3) PiB change (t = −3 to t = 0) |

−0.3 (0.5) 0.01 (0.004) −27 (10) −161 (933) |

0.60 0.01 0.01 0.86 |

| 5 N = 128 5-y follow-up |

HV change (t = −3 to t = +2) | Age (t = 0) Initial HV (t = −3) PiB SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

−1.0 (0.6) 0.01 (0.005) −3 (11) −69 (12) |

0.07 0.12 0.75 <0.0001 |

| 6 N = 94 Low-PiB 5-y follow-up |

HV change (t = −3 to t = +2) | Age (t = 0) Initial HV (t = −3) PiB SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

−1.3 (0.6) <0.001 (0.005) 13 (33) −74 (20) |

0.03 0.86 0.69 0.0002 |

| 7 N = 34 High-PiB 5-y follow-up |

HV change (t = −3 to t = +2) | Age (t = 0) Initial HV (t = −3) PiB SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

0.3 (1.3) 0.03 (0.01) 22 (33) −54 (18) |

0.84 0.01 0.63 0.01 |

| 8 N = 128 5-y follow-up |

HV change (t = −3 to t = +2) | Age (t = 0) Initial HV (t = −3) EC FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

−0.9 (0.5) 0.01 (0.005) −585 (219) −53 (11) |

0.08 0.17 0.01 <0.0001 |

| 9 N = 128 2-y follow-up |

HV change (t = 0 to t = +2) | Age (t = 0) HV (t = 0) EC FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

−0.1 (0.5) 0.01 (0.004) −513 (199) −20 (11) |

0.87 0.05 0.01 0.06 |

| 10 N = 128 2-y follow-up |

HV change (t = 0 to t = +2) | Age (t = 0) HV (t = 0) IT FTP SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

−0.3 (0.5) 0.01 (0.004) 42 (20) −44 (12) |

0.54 0.01 0.04 <0.0001 |

| 11 N = 128 2-y follow-up |

HV change (t = 0 to t = +2) | Age (t = 0) HV (t = 0) IT FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) EC FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) |

−0.2 (0.5) 0.01 (0.004) −103 (131) −600 (198) |

0.74 0.01 0.43 0.003 |

Abbreviations: EC = entorhinal cortex; FTP = flortaucipir; HV = hippocampal volume; IT = inferior temporal; PACC = Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite; PiB = Pittsburgh Compound B; SUVr = standardized uptake value ratio; WMH = white matter hypointensity.

Significant p values surviving Bonferroni correction (uncorrected p < 0.004, adjusting for the 11 independent models in the table) are in bold.

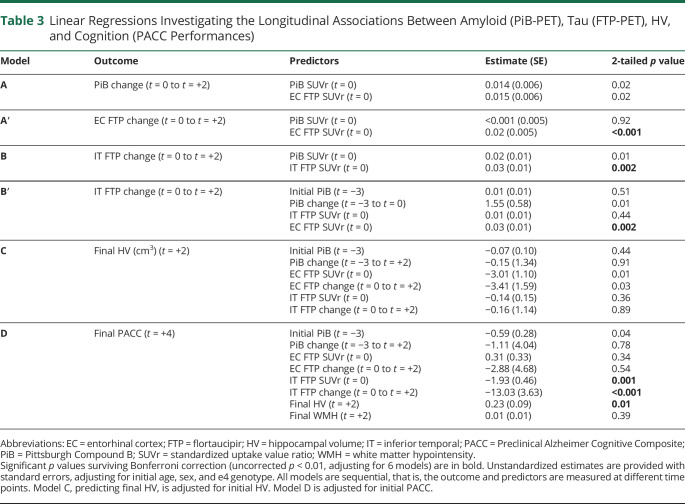

Table 3.

Linear Regressions Investigating the Longitudinal Associations Between Amyloid (PiB-PET), Tau (FTP-PET), HV, and Cognition (PACC Performances)

| Model | Outcome | Predictors | Estimate (SE) | 2-tailed p value |

| A | PiB change (t = 0 to t = +2) | PiB SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

0.014 (0.006) 0.015 (0.006) |

0.02 0.02 |

| A′ | EC FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) | PiB SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

<0.001 (0.005) 0.02 (0.005) |

0.92 <0.001 |

| B | IT FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) | PiB SUVr (t = 0) IT FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

0.02 (0.01) 0.03 (0.01) |

0.01 0.002 |

| B′ | IT FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) | Initial PiB (t = −3) PiB change (t = −3 to t = 0) IT FTP SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) |

0.01 (0.01) 1.55 (0.58) 0.01 (0.01) 0.03 (0.01) |

0.51 0.01 0.44 0.002 |

| C | Final HV (cm3) (t = +2) | Initial PiB (t = −3) PiB change (t = −3 to t = +2) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) IT FTP SUVr (t = 0) IT FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) |

−0.07 (0.10) −0.15 (1.34) −3.01 (1.10) −3.41 (1.59) −0.14 (0.15) −0.16 (1.14) |

0.44 0.91 0.01 0.03 0.36 0.89 |

| D | Final PACC (t = +4) | Initial PiB (t = −3) PiB change (t = −3 to t = +2) EC FTP SUVr (t = 0) EC FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) IT FTP SUVr (t = 0) IT FTP change (t = 0 to t = +2) Final HV (t = +2) Final WMH (t = +2) |

−0.59 (0.28) −1.11 (4.04) 0.31 (0.33) −2.88 (4.68) −1.93 (0.46) −13.03 (3.63) 0.23 (0.09) 0.01 (0.01) |

0.04 0.78 0.34 0.54 0.001 <0.001 0.01 0.39 |

Abbreviations: EC = entorhinal cortex; FTP = flortaucipir; HV = hippocampal volume; IT = inferior temporal; PACC = Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite; PiB = Pittsburgh Compound B; SUVr = standardized uptake value ratio; WMH = white matter hypointensity.

Significant p values surviving Bonferroni correction (uncorrected p < 0.01, adjusting for 6 models) are in bold. Unstandardized estimates are provided with standard errors, adjusting for initial age, sex, and e4 genotype. All models are sequential, that is, the outcome and predictors are measured at different time points. Model C, predicting final HV, is adjusted for initial HV. Model D is adjusted for initial PACC.

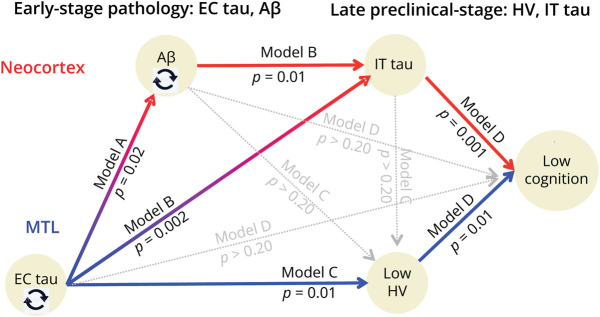

Figure 2. Schematic Illustration of the 2 Pathways Leading to Cognitive Decline.

The statistical details of the 3 sequential models (A–B, B–D, and C–D) are provided in Table 3. All models are adjusted for age, sex, education, and APOE4 genotype. The timing (baseline/change/final) of each observation depends on the specific model. Circling arrows indicate that the baseline data predict change in the same variable (e.g., baseline Aβ predicts Aβ slope) accounting for the other variables. Aβ accumulation mediates the effect of EC on IT tau, which mediates the effect of EC tau and Aβ on cognition (double mediation: A-B-D, red). Independently of Aβ, HV also mediates the effect of EC tau on cognition (C-D, in blue). Aβ = β-amyloid; EC = entorhinal cortex; HV = hippocampal volume; IT = inferior temporal.

We first evaluated the effects of covariates in models testing the associations of HV change with age, sex, APOE4 status, and initial HV (Table 2, model 1). Older ages and lower initial HV were associated with faster reductions in HV (Figure 1A), but sex and APOE4 status were not. Consequently, only age and initial HV were included in the next models of Table 2 evaluating the associations of PiB and FTP with HV changes. We then observed that high PiB SUVr was associated with faster HV reductions in the next 5 years (model 2). However, PiB change was not associated with contemporaneous (model 3) or subsequent (model 4) HV reductions, suggesting that amyloid pathology and hippocampal atrophy progress independently of each other. EC FTP was strongly correlated with HV change (R2 = 0.35), while the association between initial PiB and HV change was nonsignificant when adjusting for EC FTP (model 5), indicating that EC FTP mediated the effect of PiB on HV change (Sobel test = 3.8, p < 0.001). The association between EC FTP and HV change was significant in both the low-PiB (model 6) and the high-PiB (model 7) groups, and the estimates were of similar magnitude, indicating that the close association between EC FTP and HV change was independent of PiB. Faster HV reductions were also observed in individuals with faster EC FTP change, adjusting for the initial EC FTP measure (models 8–9 and Figure 1B). Finally, we observed that the association of EC FTP and HV change was stronger than that of IT FTP and HV change, both with cross-sectional (model 10) and longitudinal (model 11) FTP measures. In summary, the association of HV with EC FTP was stronger than that of HV with PiB or IT FTP.

Sequential Models Predicting Associations Between Pathology, Volume, and Cognition

We first observed that initial measures of FTP signal in the EC were associated with subsequent increase in PiB (Table 3, model A). By contrast, baseline PiB did not predict subsequent FTP change in the EC (A′), although it predicted FTP change in the IT (model B).

These in vivo observations are consistent with postmortem observations suggesting that entorhinal, unlike neocortical, tauopathy occurs before neocortical amyloidosis.

Another observation suggested that IT FTP change was subsequent to PiB and EC FTP: PiB change and EC FTP change were both predicted by their own baseline values (A-A′, highlighted on Figure 2 using black circling arrows); however, IT FTP change was better predicted by previous PiB change and initial EC FTP measures than by initial IT FTP (B′). PiB changes partially mediated the effect of the initial EC FTP measure on subsequent IT tau changes (Sobel model 1 = 2.6, p = 0.008, schematic representation of models A-B in Figure 2).

We then predicted the final HV measure with previous cross-sectional and longitudinal measures of PiB and FTP and confirmed the strong association between EC FTP and HV (Table 3, model C). Both PiB and IT FTP (cross-sectional or change measures) were not significantly associated with final HV, adjusting for initial HV measured 5 years earlier. In this sequential model, we predicted final HV—and not HV change—to dissociate the timing of the outcome and the predictors, but the results are entirely consistent with the observations made when predicting HV change (Table 2).

EC FTP measures were not significantly associated with final PACC when taking into account final HV and cross-sectional and change measures in IT FTP (model D). Indeed, both IT FTP change (Sobel model 2 = 2.8, p = 0.006; models B–D) and final HV (Sobel model 3 = 2.6 p = 0.008, models C and D) mediated the effect of initial EC FTP SUVr on the final PACC score. WMH measures were not associated with cognition after adjusting for all biomarker changes. Figure 2 summarizes the sequential associations between biomarkers, demonstrating 2 paths: one from initial PiB to final PACC score through successive increase in PiB and IT FTP (red) and another from initial EC FTP to final PACC score through an increase in IT FTP and HV loss (blue). The 3 significant mediations (model 1: A–B, model 2, B–D, model 3 C–D) suggest that PiB and EC FTP are biomarkers that are detected earlier in the preclinical AD course than IT FTP and HV that are more closely related to cognition.

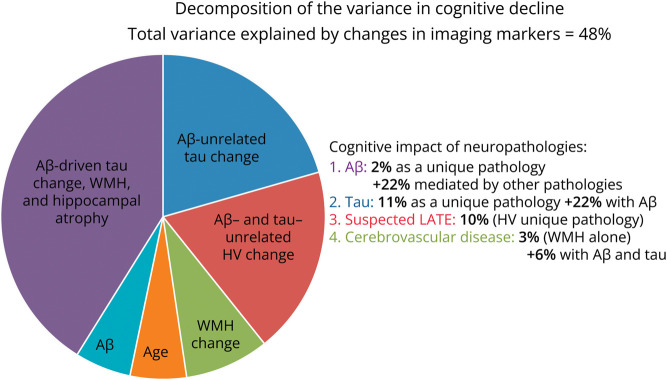

Figure 3 illustrates how the variance in PACC decline was explained by biomarker change. In total, 48% of the variance was explained by a model combining IT FTP change (unique variance explained 11%), HV change (10%), PiB slope (2%), and WMH slope (3%). Only 2% of the variance in cognitive changes was still explained by age at baseline after taking into account biomarker changes, indicating that most of the age-related cognitive decline was explained by this model. Change in EC FTP signal did not add any explanatory power when both IT FTP change and HV change were entered in the model, confirming that its association to cognitive decline was only indirect. Of note, 22% of the explanation of cognition provided from shared variance between biomarkers, indicating synergy between Aβ, tau, and atrophy that suggests AD as the cause for decline. By contrast, the variance uniquely explained by WMH and HV suggest non-AD pathologies, such as cerebrovascular disease and LATE, as the likely cause of clinical decline. When plotting the 2 most predictive biomarkers, HV change and IT FTP change, vs PACC decline in a 3D plot, the 2 independent effects are clearly visible (Figure 4). Individuals with a large HV atrophy but little IT FTP signal were older than individuals with the opposite pattern, confirming the possibility of LATE.

Figure 3. Impact of Neuropathologies on Cognition, as Measured Using Longitudinal Neuroimaging.

Only IT FTP, HV, PiB, and WMH data have been included in the analysis because the effect of EC FTP on PACC slope was entirely mediated by other biomarkers. Half of the variance explained was shared between 2 or 3 (22%) biomarkers and is suspected to reflect AD pathology (Aβ and tau-driven atrophy and WMH). IT FTP change uniquely explained the greatest amount of variance in PACC decline and is suspected to reflect a stage of AD pathology where neocortical tauopathy has become independent of Aβ pathology. Ten percent of the variance in cognition is uniquely explained by HV change and is suspected to reflect LATE. Cerebrovascular disease (WMH) explained 3% of the variance in cognition, independently of Aβ and tau. Aβ = β-amyloid; AD = Alzheimer disease; EC = entorhinal cortex; FTP = flortaucipir; HV = hippocampal volume; IT = inferior temporal; LATE = limbic age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy; PACC = Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite; WMH = white matter hypointensity.

Figure 4. Three-Dimensional Plot of Changes in Inferior Temporal Tau and Changes in Hippocampal Volume Predicting Changes in Cognition.

The effect of hippocampal volume on cognition is clearly observable in both high-Aβ and low-Aβ participants, with a greater effect in older participants (older ages are illustrated by larger dots). Independently of this effect, tau accumulation in the inferior temporal neocortex also has an effect on cognition, with a greater effect in the high-Aβ participants. Individuals who progressed to symptomatic AD (MCI) are mostly having a combination of hippocampal atrophy and neocortical tauopathy. Aβ = β-amyloid; AD = Alzheimer disease; CN = clinically normal; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; PACC = Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite; PiB = Pittsburgh Compound B; SUVr = standardized uptake value ratio.

Discussion

In this cohort study, we followed CN adults over a decade, including individuals in the preclinical phase of AD and observed a sequence of events, starting with entorhinal tauopathy, which was associated with subsequent hippocampal atrophy and neocortical Aβ, which was associated with subsequent neocortical tauopathy. Hippocampal atrophy and neocortical tauopathy were both independent predictors of lower cognition at final follow-up, mediating the effects of initial entorhinal tau and Aβ pathology. Our results suggest 2 pathways leading to cognitive impairment in older adults, one restricted to the medial temporal lobe (blue arrows in Figure 2) and the second involving Aβ and tau in neocortex (red arrows). These pathways are partially independent, with HV loss explaining part of the variability in cognitive decline at similar levels of neocortical tau. Measuring longitudinal changes in HV as a secondary outcome in clinical trials, in addition to Aβ and tau pathologies, may thus be important to better predict individual trajectories of cognitive decline and the response (or lack of response) to AD drugs. Specifically, regarding anti-Aβ immunotherapies that were recently approved, the current data lead to the following observations: It is likely these drugs will provide the greatest clinical benefits in individuals with amyloidosis and only limited neocortical tauopathy and hippocampal atrophy because these 2 pathologies are associated with cognitive decline independently of Aβ. The mechanisms behind the reduced benefits may be different though because the effect of neocortical tau on cognition is initially mediated by Aβ, suggesting AD as the cause of cognitive impairment at a stage where tauopathy has become independent of Aβ, whereas major hippocampal atrophy in the absence of neocortical tauopathy suggests non-AD pathologies, such as LATE or PART.

The observation that HV strongly correlates to cognition has been made for at least 30 years.19 However, it is only recently that the contributions of different age-related neuropathologies responsible for hippocampal atrophy are disentangled. In our study, we observed that HV loss was predicted by older ages and that the impact of HV loss on cognition was greater at older ages. Because these observations were made adjusting for Aβ and tau pathologies, they suggest the contribution of non-AD neuropathologies.20 Some of these pathologies, such as LATE13-15 or cerebrovascular disorders,16 are known to be associated with hippocampal atrophy and could contribute to the strong correlation observed between HV and cognition, even after adjusting for AD pathologies. Measuring HV may thus provide information on the possibility of non-AD pathologies, either as the main cause21 (low-Aβ/tau) or as a copathology (high-Aβ/tau) contributing to cognitive decline. It is nevertheless important to acknowledge that even after including Aβ, tau, WMH, and atrophy in our predictive models, half the variance in cognitive decline could not be explained, suggesting that some neuropathologies (e.g., α-synuclein) or other contributions to cognitive decline (e.g., genetics or lower cognitive reserve) cannot be detected by measuring HV. However, a global measure of CV did not improve the prediction of cognitive decline. More detailed structural changes or specific biomarkers for non-AD neuropathologies should therefore be developed to improve our ability to predict, and ultimately prevent, age-related cognitive decline.

Of note, we did not observe a strong correlation between cognitive decline and total CV (or parietal atrophy), highlighting the regional specificity of the medial temporal lobe for cognitive decline in sporadic AD, whereas early parietal atrophy has been observed as a prominent feature in autosomal dominant AD studies.22,23

Besides age, HV was mostly predicted by entorhinal tauopathy, an early event in preclinical AD that was associated with subsequent Aβ and neocortical tauopathy. Structural and metabolic dysfunctions of the medial temporal lobe are well-known predictors of subsequent cognitive impairment in preclinical AD.24 However, HV was also associated with entorhinal tau when restricting analyses to the low-Aβ subgroup, suggesting that PART17 contributes to hippocampal atrophy and cognitive decline. Of note, the impact of entorhinal tau on cognition in the low-Aβ subgroup was entirely mediated by HV, indicating that HV could serve as a biomarker for monitoring this medial temporal lobe pathology after AD pathology is excluded. Similarly, medial temporal hypometabolism on FDG-PET was recently suggested as a biomarker of LATE, based on both autopsy-validated and a large cross-sectional FDG data set.25 Increasing evidence suggests that medial temporal atrophy and dysfunction occurring in the absence of Aβ26 or tau27 pathology are associated with cognitive decline. Further work should better determine the sensitivity of different tau-PET tracers to PART to better distinguish the respective contributions of PART and LATE to hippocampal atrophy and cognitive decline.

Our conclusions are limited by the convenience sample that has been included in HABS. Participants are indeed highly educated and mostly White, limiting the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the results are partially driven by a few individuals who progressed to MCI or dementia during the study. Removing these individuals from the analyses did not modify the results other than reducing the total amount of cognitive variance explained to 31%. The respective contributions of hippocampal atrophy and neocortical tau accumulation remained unchanged, suggesting that both AD and non-AD pathologies contribute to cognitive decline before clinical impairment is detectable.

We did not obtain tau PET scans at study start because the FTP tracer was not yet available. Although we provided some evidence in favor of entorhinal FTP preceding PiB signal, we could thus not observe the sequence between early tau changes and subsequent Aβ. In addition, the present work did not use specific regional data or a low threshold to detect early Aβ making it difficult to exclude an early contribution of Aβ pathology to entorhinal tau. Future work should include younger individuals to specifically focus on the onset of early AD pathology.

Group studies may be insensitive to atypical patterns of biomarker progression, and larger studies are required to evaluate interindividual variations in biomarkers trajectories. This study was not designed to detect atypical presentations of AD or non-AD pathologies. Studying genetic and lifestyle variations across individuals may also shed light on the different cognitive trajectories and explain part of the variance in HV and AD pathology. Longer studies or including more observations per participant might lead to different conclusions.

Developing biomarkers of non-AD pathology, whether through imaging or in biofluids, is of utmost importance to better understand cognitive decline in aging and pathologic conditions. Therefore, the utility of measuring morphometric changes, such as HV, will need to be re-evaluated when such novel biomarkers become available.

In this longitudinal study of CN older adults, we observed that decline in cognition after a 10-year follow-up resulted (1) from successive changes in Aβ and tau in the neocortex and (2) from medial temporal lobe pathologies, including entorhinal tauopathy, leading to hippocampal atrophy. Cerebrovascular disease, as measured using WMH, did not contribute much to cognitive decline. Larger and more diverse samples are needed to support the proposed sequential pathways. Biomarkers targeting non-AD pathologies such as TDP43 or α-synuclein are required to confirm the contributions of such pathologies to hippocampal atrophy. In the meantime, measuring HV in trials together with Aβ and tau may help identify individuals who are more likely to present with non-AD copathologies and therefore potentially respond differently to AD drugs.

Glossary

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- CN

clinically normal

- CV

cortical volume

- EC

entorhinal cortex

- FTP

flortaucipir

- HABS

Harvard Aging Brain Study

- HV

hippocampal volume

- IT

inferior temporal

- LATE

limbic age-related TDP43 encephalopathy

- LM

Wechsler Logical Memory II delayed recall

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- PART

primary age-related tauopathy

- PACC

Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite

- PiB

Pittsburgh Compound B

- SUVr

standardized uptake value ratio

- WMH

white matter hypointensity.

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Bernard J. Hanseeuw, MD, PhD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA; Department of Neurology, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Heidi I.L. Jacobs, PhD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA; Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, Alzheimer Centre Limburg, Maastricht University, the Netherlands | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Aaron P. Schultz, PhD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Rachel F. Buckley, PhD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences, University of Melbourne, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Michelle E. Farrell, PhD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Nicolas J. Guehl, PhD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| John A. Becker, PhD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Michael Properzi, BEng, BSc | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Justin S. Sanchez, BS | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Yakeel T. Quiroz, PhD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Patrizia Vannini, PhD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Jorge Sepulcre, MD, PhD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Hyun-Sik Yang, MD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Jasmeer P. Chhatwal, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Jennifer Gatchel, MD, PhD | Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Gad A. Marshall, MD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Rebecca Amariglio, PhD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Kathryn Papp, PhD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Dorene M. Rentz, PsyD | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Marc Normandin, PhD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Julie C. Price, PhD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Brian C. Healy, PhD | Department of Biostatistics, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Georges El Fakhri, PhD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Reisa A. Sperling, MD, MMSc | Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design |

| Keith A. Johnson, MD | Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging; Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Footnotes

Editorial, page 1087

Study Funding

This work was supported with funding from the NIH, including P01 AG036694 (Sperling, Johnson), R01 AG046396 (Johnson), the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS #CCL40010417, Welbio #40010035, Hanseeuw), and the Queen Elizabeth Medical Foundation (Hanseeuw).

Disclosure

B.J. Hanseeuw reports funding from the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS #CCL40010417, Welbio #40010035). H.I.L. Jacobs reports funding from the NIH (R01 AG062559, R01 AG068062, R21 AG074220) and the Alzheimer's Association (AARG-22-920434). She serves as chair on the Neuromodulatory Subcortical Systems Professional Interest Area, as advisory council member of ISTAART, and as associate editor for the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. Y.T. Quiroz serves as consultant for Biogen. H.S. Yang reports funding from the NIH (K23 AG062750). J.P. Chhatwal reports funding from the NIH (R01 AG062667, R01AG071865). He has served on advisory boards for Humana Healthcare, Leerink Partners, and Expert connect. G.A. Marshall reports funding from the NIH (R01 AG067021, R01 AG053184, R01 AG071074, R42 AG069629, and R21 AG070877) and research salary support unrelated to the current study from Eisai Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, and Genentech. J.C. Price reports funding from the NIH (R01 AG050436, R01 AG052414). B.C. Healy has received research support from Analysis Group, Celgene (Bristol-Myers Squibb), Verily Life Sciences, Merck-Serono, Novartis, and Genzyme. R.A. Sperling reports funding from the NIH (P01 AG036694). K.A. Johnson reports funding from the NIH (P01 AG036694, R01 AG046396). All other authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apostolova L, Zarow C, Biado K, et al. Relationship between hippocampal atrophy and neuropathology markers: a 7T MRI validation study of the EADC-ADNI Harmonized Hippocampal Segmentation Protocol. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(2):139-150. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(5):362-381. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(1):110-119. doi: 10.1002/ana.24546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanseeuw BJ, Betensky RA, Jacobs HI, et al. Association of amyloid and tau with cognition in preclinical Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal study. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(8):915-924. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280-292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmers T, Ossenkoppele R, Wolters E, et al. Associations between quantitative [18F]flortaucipir tau PET and atrophy across the Alzheimer's disease spectrum. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0510-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berron D, Vogel JW, Insel PS, et al. Early stages of tau pathology and its associations with functional connectivity, atrophy and memory. Brain. 2021;144(9):2771-2783. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez JS, Becker JA, Jacobs HIL, et al. The cortical origin and initial spread of medial temporal tauopathy in Alzheimer's disease assessed with positron emission tomography. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(577):eabc0655. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc0655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tosun D, Demir Z, Veitch DP, et al. Contribution of Alzheimer's biomarkers and risk factors to cognitive impairment and decline across the Alzheimer's disease continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(7):1370-1382. doi: 10.1002/alz.12480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison TM, La Joie R, Maass A, et al. Longitudinal tau accumulation and atrophy in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(2):229-240. doi: 10.1002/ana.25406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson PT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): consensus working group report. Brain. 2019;142(6):1503-1527. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josephs KA, Dickson DW, Tosakulwong N, et al. Rates of hippocampal atrophy and presence of post-mortem TDP-43 in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a longitudinal retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(11):917-924. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30284-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josephs KA, Martin PR, Weigand SD, et al. Protein contributions to brain atrophy acceleration in Alzheimer's disease and primary age-related tauopathy. Brain. 2020;143(11):3463-3476. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabin JS, Pruzin J, Scott M, et al. Association of β-amyloid and vascular risk on longitudinal patterns of brain atrophy. Neurology. 2022;99(3):e270-e280. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, et al. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(6):755-766. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1349-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mormino EC, Papp KV, Rentz DM, et al. Early and late change on the preclinical Alzheimer's cognitive composite in clinically normal older individuals with elevated amyloid β. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(9):1004-1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheltens P, Leys D, Barkhof F, et al. Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in “probable” Alzheimer's disease and normal ageing: diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(10):967-972. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.10.967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider JA. Neuropathology of dementia disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2022;28(3):834-851. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000001137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botha H, Mantyh WG, Graff-Radford J, et al. Tau-negative amnestic dementia masquerading as Alzheimer disease dementia. Neurology. 2018;90(11):e940-e946. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon BA, Blazey TM, Su Y, et al. Spatial patterns of neuroimaging biomarker change in individuals from families with autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(3):241-250. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30028-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuller JT, Cronin-Golomb A, Gatchel JR, et al. Biological and cognitive markers of presenilin1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease: a comprehensive review of the Colombian Kindred. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019;6(2):112-120. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2019.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayblyum DV, Becker JA, Jacobs HIL, et al. Comparing PET and MRI biomarkers predicting cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2021;96(24):e2933-e2943. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grothe MJ, Moscoso A, Silva-Rodríguez J, et al. Differential diagnosis of amnestic dementia patients based on an FDG-PET signature of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(4):1234-1244. doi: 10.1002/alz.12763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wisse LEM, de Flores R, Xie L, et al. Pathological drivers of neurodegeneration in suspected non-Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00835-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCollum L, Das SR, Xie L, et al. Oh brother, where art tau? Amyloid, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline without elevated tau. Neuroimage Clin. 2021;31:102717. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

B.J. Hanseeuw and K.A. Johnson had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Request for data can be sent to the following email address: habsdata@mgh.harvard.edu.