Summary:

Varying coefficient models have been used to explore dynamic effects in many scientific areas, such as in medicine, finance, and epidemiology. As most existing models ignore the existence of zero regions, we propose a new soft-thresholded varying coefficient model, where the coefficient functions are piecewise smooth with zero regions. Our new modeling approach enables us to perform variable selection, detect the zero regions of selected variables, obtain point estimates of the varying coefficients with zero regions and construct a new type of sparse confidence intervals that accommodate zero regions. We prove the asymptotic properties of the estimator, based on which we draw statistical inference. Our simulation study reveals that the proposed sparse confidence intervals achieve the desired coverage probability. We apply the proposed method to analyze a large scale preoperative opioid study.

Keywords: Non-parametric regression, Opioid use, Sparse confidence intervals, Varying coefficient with zero regions

1. Introduction

The World Drug Report UNDOC (2014) reveals that opioid use for pain treatment has risen sharply, but without much improvement in reducing the severity of chronic pain (CDCP, 2007). Patients with preoperative opioid use have worse surgical outcomes, greater postoperative pain, more pronounced morbidity, higher rates of use of health care services (Zywiel et al., 2011; Chapman et al., 2011; Pivec et al., 2014), and are less likely to stop opioid-based therapy after surgery (Goesling et al., 2016; Cron et al., 2017). To avoid unnecessary opioid use and prevent possible opioid addiction, effective strategies for opioid prescription management are needed for both patients and physicians. For obese patients, effective prescription management is especially important because of complex co-comorbidities associated with obesity (Schug and Raymann, 2011). It is critical to understand whether and how the association between preoperative opioid use and pain is modified by the level of body mass index (BMI) (Schug and Raymann, 2011).

This work was motivated by a study on the association of preoperative opioid use and the characteristics of patients in a broadly representative surgical cohort (Hilliard et al., 2018). Our preliminary analysis, based on a varying coefficient model (Hastie and Tibshirani, 1993), shows that the dose-relationship between opioid use and pain level changes from negative to positive with BMI increasing from 15.5 to 20.0, and the non-significant and significant regions are not well separated. A practical explanation is that there may exist zero-effect regions in terms of BMI for pain on opioid use. The zero-effect regions of BMI, that is, the regions where opioid use is not related to pain, may hint at possible opioid addictions. However, most existing methods ignore the existence of zero-effect regions. There is a need to develop a varying coefficient model that enables us to estimate zero-effect regions and quantify the associated uncertainty.

Varying coefficient models (Hastie and Tibshirani, 1993) are commonly used to characterize the dynamic changes of regression effects. Framing the model in the context of opioid use, we denote by the total amount of preoperative opioids, and by the covariates, consisting of demographic information and clinical symptoms, such as preoperative pain. The following model detects how the covariate effects on opioid use are modified by BMI (denoted by ):

| (1) |

where is the varying coefficient function representing the effect of , and is a random variable with mean zero and variance . We set to be 1, corresponding to the intercept function. The challenge lies in how to detect zero-effect regions and draw inference on varying coefficient functions simultaneously, and is aggravated when is large.

Local log-likelihood approaches have been proposed to estimate . Hoover et al. (1998) used the smoothing spline and local polynomial methods; Fan and Zhang (1999) proposed a two-step procedure to allow more flexibility of coefficient functions; Wu et al. (2000) and Chiang et al. (2001) proposed component-based kernel and smoothing spline estimators for varying coefficient models with repeated measurements. In high-dimensional settings, variable selection and screening with varying coefficient models were studied (Liu et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016). The local polynomial estimators may not provide adequate smoothing for all the coefficients simultaneously and the computational burden of smoothing splines can be heavy. Also proposed were other alternative methods, including global estimation and variable selection for varying coefficient models based on basis approximations (Huang et al., 2002, 2004) and penalized spline-based models (Eubank et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012; Xue and Qu, 2012; Cheng et al., 2014; Fan et al., 2014; Song et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2016; He et al., 2018). However, none of them can detect zero-effect regions.

Model (1) differs from functional linear models (Ramsay and Dalzell, 1991; Ramsay and Silverman, 2007; James et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013) and scalar-on-image regression models (Kang et al., 2018), of which both coefficients and covariates are functional. The roles and interpretations of functional coefficients deviate from those in model (1), as the latter is designed to characterize the varying effects of scalar covariates. Moreover, the methods of drawing statistical inference on zero-effect regions for functional linear models (James et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2018) are not applicable to model (1).

We propose a soft-thresholded varying coefficient model, where coefficients in model (1) are constructed by applying soft-thresholding operators to smooth functions. The soft-thresholded varying coefficients are continuous, piecewise smooth, and with zero-effect regions. The smooth functions before soft-thresholding can be approximated using B-splines (Silverman, 1985; Stone, 1986; Eilers and Marx, 1996), or some other basis functions, such as smoothing splines or reproducing kernel Hilbert space splines (Wahba, 1990; Berlinet and Thomas-Agnan, 2011). The soft-thresholded function, originally introduced to construct estimators for the wavelet coefficients (Donoho and Johnstone, 1994; Donoho, 1995), has been used for effect shrinkage. For example, Chiang et al. (2001) proposed an adaptive, data-driven threshold for image denoising in a Bayesian framework; Tibshirani (1996) pointed out that the lasso estimator is a soft-thresholded estimator when the covariate matrix is orthonormal. As all of these estimators were designed for finite dimensional parameters, their usage for functional coefficients, including varying coefficients, remains elusive.

Our approach distinguishes from the existing methods as follows. First, our method involves a novel application of a soft-thresholding operator in a functional space, which enables us to uncover zero-effect regions of varying coefficients. The soft-thresholded estimates are continuous, piecewise smooth and with zero-effect regions, and possess an easy interpretation for a range of applications. Second, our new modeling framework enables us to estimate varying coefficients and draw the statistical inference. We particularly develop a new type of confidence interval, termed sparse confidence intervals, which can be degenerated to a singleton with a non-zero probability. Finally, we have established theoretical properties, which inform valid statistical inference for high-dimensional varying coefficient models.

2. Method

2.1. Varying coefficient models with zero-effect regions

We write in model (1) as a vector of varying coefficients, where may grow with the sample size. In the following, we use to denote the truth of ; when there is no ambiguity, we use the simplified form of for the true functions as well. Without loss of generality, we assume . To detect zero-effect regions of , we assume that each is continuous everywhere, with zero-effect regions (if existing) consisting of at least one interval, and is smooth over regions where its effect is non-zero. Specifically, let , , , and be the closure of any set . The functional space containing is defined below.

Definition 1: contains with: (continuity) , for any ; (zero-effect regions) either is empty or contains at least one interval with a non-zero Lebesgue measure; (piecewise smoothness) can be partitioned as a union of disjoint intervals, each with a non-zero Lebesgue measure. The derivative of exists and satisfies the Lipschitz condition on each interval: , where is a non-negative integer, and such that .

The smoothness requirement for in our definition is weaker than that in Kang et al. (2018). The full-zero coefficients are those with , and partial-zero coefficients are those with . Definition 1 implies a “buffer zone” when an effect switches signs, reflecting gradual degradation in real life. We assume that the each component of the true parameter , say, . Let be the number of full-zero coefficients, and be the number of partial-zero and non-zero coefficients, where is the indicator function. Without loss of generality, we assume the first coefficients are either partial-zero or non-zero. Sparsity conditions need to be imposed on to ensure the estimability of these partial- or non-zero coefficients; see Condition (C6) in the Web Appendix.

2.2. Soft-thresholding operator

Representing zero-effect regions for varying coefficients, we propose a soft-thresholding operator :

| (2) |

where is the thresholding parameter and is a real-valued function. Though resembling Donoho and Johnstone (1994), designed for denoising wavelet coefficients, our proposal (2) is a functional operator which transforms a function to a function (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1:

Panel (a) demonstrates the soft-thresholding operator, where various smooth functions (shown as dashed lines) with different thresholding values (, , and ) are mapped to the same curve with a zero-effect region (shown as a solid line). The dashed lines above the corresponding values have the same shape in all three scenarios, but the lines below the corresponding values differ. Comparison of (i) and (ii) in Figure 1(a) shows that they use the same smooth function but with different values of . Therefore, the shapes of the dashed lines are the same, but their intercepts are different. In comparison, (ii) and (iii) in Figure 1(a) use the same value of but for smooth functions with different shape and intercept. Panel (b) illustrates the concept of sparse confidence intervals (SCI), where the true varying coefficient is denoted by , its estimation by , and the coverage probability by CP. In the range of , the probability of is greater than 0.95, causing the 95% SCI to degenerate to [0, 0], while maintaining a coverage probability between 0.95 and 1.0 for each . For all , the coverage probability is exactly 0.95.

Let be a class of functions defined on , with the derivative satisfying the Lipschitz condition in Definition 1. According to Lemma 1 in the Web Appendix, we have that for any function and any , there exists at least one such that .

As illustrated by Figure 1(a), the soft-thresholding operator maps different smooth with different thresholding parameter to the same . Even for a fixed , may not be uniquely defined and, hence, is not estimable without further constraints. Our strategy is to consider a sieve space that approximates and shows that, within the sieve space, a penalized loss function can uniquely determine a , which after soft thresholding will approximate the desired . In theory, we may set a to be any positive number, but our numerical experience suggests that choosing an appropriate , which is comparable to the scale of , lead to more stable and efficient estimates. Thus, in a regression setting, we specify covariate-specific .

2.3. Spline approximation and differentiable approximation

We specify a B-spline function sieve space, denoted by , to approximate . Let be an integer with . Following Schumaker (2007), we let with be the B-spline basis functions of degree associated with the knots , satisfying .

Definition 2: Let be a functional vector of the B-spline bases. We define .

Let . With the observed data being independent samples of , we specify

| (3) |

Compared to model (1), model (3) should be viewed as a “working” model, wherein may not be unique or estimable. But with a penalized loss function specified below, the soft thresholded estimate based on a working sieve model can approximate the truth, .

We define a penalized least-squares loss function:

where and are the coefficients of bases. The penalty term aims to shrink the varying-coefficients, which can prevent over-fitting in model fitting and identify the unique inner functions in . Although we use the same for all coefficient functions, different can be chosen for different covariates.

Let be a non-random function, and be i.i.d. copies of random vector . We denote by the theoretical mean of and by the empirical mean of . Define as the true sieve parameters to estimate. Let and with .

For given and , we define the thresholded sieve space

By Lemma 3 in the Web Appendix, if for with and the same as in the penalized likelihood, ; if for , we have , where is the smoothness parameter as in Definition 1.

As in (2) is not differentiable everywhere, we consider a smooth approximation of it.

Definition 3: A smooth approximation of , denoted by , is continuous and twice differentiable with respect to everywhere and , where and .

For example, a smooth approximation of is defined as

| (4) |

where , and . The approximation error between and is bounded by and is continuous and differentiable. The proof can be found in the Web Appendix.

For simplicity, we drop and and write with . Then, we define a smoothed loss function:

| (5) |

2.4. Estimation

We minimize the empirical mean of (5) to obtain an estimate of . Then the estimate for is , where .

Computation of can be implemented by gradient-based methods and a coordinate descent algorithm. In simulations, we employ a gradient-based algorithm for low dimensional cases, while for high dimensional cases, we combine the gradient-based algorithm with coordinate descent to ensure convergence. The gradient-based optimizer theoretically exhibits linear or sublinear convergence (Mason et al., 1999). With appropriate initial values, global optimizers can be reached. For each , we set the initial to be the sample correlation between and , i.e. , where . In our experience, convergence can be achieved within a few iterations with this initial value.

2.5. Hyperparameter specifications

We choose the pre-specified parameters as follows. As a value of threshold parameter in the order of the scale of true coefficients works well, we set to be half of the absolute value of the corresponding coefficient estimate from a parametric model. The parameter controls how well the function in (4) approximates the soft-thresholding operator. A smaller gives a closer but less smooth approximation. The parameter controls shrinkage effects on the varying-coefficient. To ensure the theoretical properties of the estimation, the choices of and can be specified in accordance with Condition (C6) in the Web Appendix. In practice, we suggest and leading to excellent performance in estimation and inferences. Please refer to results in Sections 4 and 5. From our experiences, the results are not sensitive to the choice of , typically a small value of ranging from 0.0001 to 0.01 can provide a good result. The knots of B-spline are equally spaced over . The number of basis functions, , can be determined through -fold cross-validation. That is, partition the full data into equal-sized groups, denoted by , for , and let be the estimate obtained with bases using all the data except for . We obtain the optimal by minimizing the cross-validation error

| (6) |

3. Inference

3.1. Asymptotic properties

Let , and denote by and the first and second derivatives of with respect to respectively. It follows that and , where , and is a diagonal matrix. Let , an matrix with . Let , and . To establish the theoretical properties, we enumerate the needed technical conditions and discuss their implications and reasonableness in Section S1 in the Web Appendix.

Theorem 1 (Convergence Rate): Under Conditions (C1), (C4), (C6) and (C7) in the Web Appendix, given fixed , if for with and being the same as in, then ; if for , .

Of note, this convergence rate holds for any threshold parameter , due to the strong result of Lemma 1. By Condition (C6) in the Web Appendix and , Theorem 1 implies convergence of .

Let , where is -dimensional vector with -th entry being one and others being zero. We obtain the limiting distributions of the estimators.

Theorem 2: Under Conditions (C1)-(C7) in the Web Appendix, then for any , the limiting distribution of satisfies

where , and is the cumulative distribution function for . Here, are considered as fixed numbers.

The limiting distribution in Theorem 2 reveals that the probability of is greater than 0, which enables us to detect zero-effect regions even with finite sample size.

3.2. Sparse confidence intervals

To draw valid statistical inference, we develop a new type of confidence intervals for the varying coefficients with zero-effect regions. Classical confidence intervals are not applicable as the limiting distributions of the estimators involve zero point-masses.

Definition 4 (Sparse confidence interval): For any , let and be the lower and upper bound estimates of , and let .

i) when , is a level sparse confidence interval if, for any , ;

ii) when , is a level sparse confidence interval if there exists an integer , such that or for any , and .

When , a sparse confidence interval allows the upper bound or the lower bound or both to be zero with a non-zero probability; see Figure 1(b). This unique property distinguishes the sparse confidence interval from its classical counterpart and provides a useful means to draw inference on estimated zero-effect regions, which also differs from the post-selection inference (Lee et al., 2016; Tibshirani et al., 2016; Taylor and Tibshirani, 2018).

The derivation of sparse confidence intervals utilizes Lemma 6 and can be found in the Web Appendix. Under Conditions (C1)-(C7) and given , for any we construct a pointwise level asymptotic sparse confidence interval for , denoted by . Let and be the quantile and the cumulative distribution function of , respectively, and be with replaced by . Let and , which can be estimated by and using Theorem 2. We construct as follows:

If , ;

else if and , with and as defined in Lemma 6;

else if and , with ;

else .

Theorem 3: Under Conditions (C1)-(C7) in the Web Appendix, is a level sparse confidence interval of for and any .

4. Simulation Studies

4.1. Low dimensional covariates

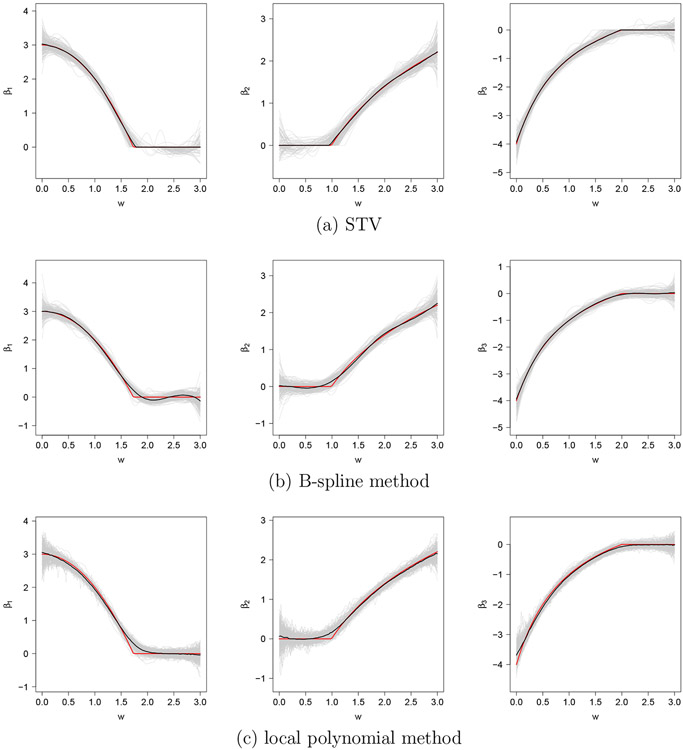

With , we compare the accuracy in estimation and inference between our method and two competing methods, the regular B-spline method (Eilers and Marx, 1996) and the local polynomial method (Fan and Zhang, 1999). We simulate data from (1), where are generated from a uniform distribution on [0, 3], the covariates are generated from a multivariate normal distribution with mean zero and , and are generated from a standard normal distribution such that the noise to effect ratio is 0.1. The coefficient functions are , , and . In simulation studies, the degree of B-spline is chosen to be 3.

We choose , 500 and 1,000 and generate 200 datasets for each setting. We set and . In theory, the choice of should not impact the fitting of the soft-thresholded varying coefficient model. However, our numerical experience suggests that a good performance is achieved by setting to be half of the absolute value of the least-squares estimate. We have opted to do so in the later simulations and data analysis. The number of knots, , is selected through cross-validation. For evaluation criteria, we use the integrated squared errors and the averaged integrated squared errors, defined as and , respectively, where are the grid points on . Table 1(a) shows that the soft-thresholded varying coefficient model has smaller integrated squared errors and averaged integrated squared errors than the other two methods. Figure 2 compares the true coefficients and the medians of the estimates obtained by the competing methods. Only the medians of the estimates obtained by the soft-thresholded varying coefficient model overlap with the truth, indicating the usefulness of our proposed method when estimating the zero-effect regions.

Table 1:

Simulation results under the low and high dimensional settings

| (a) Simulation results for three models with p = 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | AISE | ||||

| STV | 21 (16) | 21 (16) | 22 (17) | 21 (12) | |

| B-spline | 200 | 30 (19) | 28 (18) | 24 (16) | 28 (13) |

| local polynomial | 31 (15) | 23 (13) | 29 (16) | 28 (10) | |

| STV | 7 (5) | 7 (6) | 8 (5) | 8 (4) | |

| B-spline | 500 | 13 (6) | 11 (7) | 10 (6) | 11 (5) |

| local polynomial | 15 (6) | 11 (5) | 15 (8) | 14 (4) | |

| STV | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 4 (2) | |

| B-spline | 1000 | 8 (2) | 6 (3) | 4 (3) | 6 (2) |

| local polynomial | 9 (3) | 7 (3) | 9 (4) | 8 (2) | |

| ISE: the integrated squared errors; AISE: the averaged integrated squared errors. Values are means and standard deviations from 200 replications and multiplied by 103. | |||||

| (b) Simulation results under the high dimensional settings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | C (%) | O (%) | U (%) | FP | FN | TISE | PMSE | |

| n=200, p=250 | ||||||||

| STV | 7 | 93 | 0 | 2.63 (1.67) | 0 (0) | 1.64 (0.57) | 3.56 (0.63) | |

| Ind | grscad | 56 | 44 | 0 | 2.27 (5.65) | 0 (0) | 3.74 (2.19) | 6.97 (4.08) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 31.94 (12.7) | 0 (0) | 7.59 (1.62) | 7.81 (1.41) | |

| STV | 1 | 99 | 0 | 5.88 (2.62) | 0 (0) | 3.61 (1.14) | 3.67 (0.73) | |

| AR(1) | grscad | 24 | 69 | 7 | 5.87 (6.59) | 0.07 (0.26) | 7.89 (4.87) | 6.77 (3.29) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 34.25 (11.62) | 0 (0) | 11.73 (1.7) | 7.39 (1.24) | |

| STV | 4 | 93 | 3 | 3.95 (2.76) | 0.03 (0.17) | 2.69 (1.59) | 2.41 (0.81) | |

| CS | grscad | 68 | 28 | 4 | 2.25 (5.04) | 0.06 (0.31) | 5.77 (14.07) | 5.48 (12.8) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 37.95 (12.25) | 0 (0) | 9.06 (1.77) | 4.81 (1.23) | |

| n=500, p=750 | ||||||||

| STV | 99 | 1 | 0 | 0.01 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (0.07) | 2.66 (0.25) | |

| Ind | grscad | 63 | 37 | 0 | 5.3 (11.21) | 0 (0) | 0.64 (0.39) | 2.85 (0.3) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 48.85 (21.98) | 0 (0) | 2.88 (0.87) | 3.78 (0.43) | |

| STV | 88 | 12 | 0 | 0.13 (0.37) | 0 (0) | 0.87 (0.26) | 2.37 (0.25) | |

| AR(1) | grscad | 65 | 35 | 0 | 5.09 (10.55) | 0 (0) | 0.71 (0.32) | 2.19 (0.22) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 68.46 (21.49) | 0 (0) | 5.22 (0.96) | 3.49 (0.4) | |

| STV | 59 | 40 | 1 | 1.21 (2.12) | 0.01 (0.1) | 0.81 (0.58) | 1.58 (0.31) | |

| CS | grscad | 58 | 42 | 0 | 6.19 (9.73) | 0 (0) | 0.58 (0.29) | 1.44 (0.16) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 57.51 (19.2) | 0 (0) | 3.28 (0.77) | 2.03 (0.24) | |

| n=1000, p=1500 | ||||||||

| STV | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.18 (0.03) | 2.53 (0.17) | |

| Ind | grscad | 56 | 44 | 0 | 8.22 (20.01) | 0 (0) | 0.36 (0.42) | 2.56 (0.17) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 56.39 (26.67) | 0 (0) | 1.6 (0.61) | 2.95 (0.22) | |

| STV | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.59 (0.14) | 2.18 (0.16) | |

| AR(1) | grscad | 54 | 46 | 0 | 6.18 (12.93) | 0 (0) | 0.33 (0.21) | 1.96 (0.14) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 87.69 (28.54) | 0 (0) | 2.85 (0.63) | 2.5 (0.2) | |

| STV | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.37 (0.09) | 1.38 (0.11) | |

| CS | grscad | 57 | 43 | 0 | 5.34 (11.28) | 0 (0) | 0.26 (0.21) | 1.28 (0.09) |

| grlasso | 0 | 100 | 0 | 63.36 (25.84) | 0 (0) | 1.71 (0.56) | 1.51 (0.12) | |

STV: the soft-thresholded varying coefficient model; grscad: B-spline varying coefficient model with group SCAD penalty; grlasso: B-spline varying coefficient model with group lasso penalty; C: the percentage of correct-fitting; U: the percentage of under-fitting; O: the percentage of over-fitting; FP: the number of false positives; FN: the number of false negatives; TISE: the total integrated squared errors between and ; PMSE: the predictive mean squared errors between and on testing data; Ind, AR(1), and CS represent independent, autoregressive and compound symmetry correlation of covariates, respectively. Results are from 100 replications.

Figure 2:

Comparisons of three methods. The red solid line is the true curve, the gray solid lines are the estimated curves, and the black solid line is the median of the estimated curves.

We also conduct a simulation to study the robustness of the proposed model when the true varying coefficients are zero-crossing. The results, which are detailed in Section S6 in the Web Appendix, suggest a good performance of the soft-thresholded varying coefficient model even under this misspecified model.

4.2. High dimensional covariates

With , we compare variable selection and the prediction accuracy between our method and the penalized spline procedures with the group SCAD penalty and the group lasso penalty presented in Wei et al. (2011). We simulate data from (1), where are generated from a uniform distribution on [0, 3], the covariates are generated from a multivariate normal distribution with mean zero and covariance (independent) or (autoregressive) or (compound symmetry), and the random errors are generated from a standard normal distribution such that the noise to effect ratio is 0.1. The coefficient functions are , , and and for . We consider various (, ): (200, 250), (500, 750) and (1000, 1500). For each setting, a testing dataset with the same is also generated, and for each parameter configuration, a total of 100 datasets are generated.

We use the R package grpreg (Breheny and Zeng, 2019) to implement the group SCAD penalized B-spline model, and the group lasso penalized B-spline model. The penalty tuning parameters are chosen through 10-fold cross-validation with a default option in the grpreg package. The number of knots for B-spline is selected to be 12 and is fixed across all the methods for computational convenience. Table 1(b) summarizes selection and estimation accuracy, including the total integrated squared errors between and , which is defined as , the predictive mean squared errors between and on the testing data, the number of false positives and false negatives, and the percentages of correct-fitting, over-fitting and under-fitting. Following Xue and Qu (2012), correct-fitting is called if the selected set equals the true signal set, over-fitting if the selected set includes but is not equal to the true signal set, and under-fitting otherwise.

The results indicate that the soft-thresholded varying coefficient model outperforms the group SCAD penalized B-spline model and the group lasso penalized B-spline model with higher percentages of correct-fitting and fewer false positives; when comparing the total integrated squared errors and the predictive mean squared errors, the soft-thresholded varying coefficient model is always better than the group lasso penalized model, and outperforms the group SCAD penalized model for the independent case, and has similar results as the group SCAD penalized method for the autoregressive and compound symmetry cases.

We finally compare the computing time when implementing the competing methods with a CPU of 2.7 GHz and a memory of 8 GB. Our method is more computationally efficient. For example, with independent covariates and , the soft-thresholded varying coefficient model, the group SCAD penalized model and the group lasso penalized model respectively take 14.98, 25.03, and 23.24 seconds per dataset on average.

4.3. Confidence Intervals for Turning Points

We draw inference on the turning points and construct the confidence intervals. Specifically, we compare the coverage probability, bias, and mean squared error in estimation and inference under various settings when . To do so, we simulate data from (1), where is drawn from a uniform distribution on [0, 3], the covariates are generated from a multivariate normal distribution with mean zero and covariance (independent) or (autoregressive) or (compound symmetry), and the random error are generated from a standard normal distribution such that the noise to effect ratio is 0.1. We set the coefficient functions to be , , and .

We vary to be 200, 500 and 1,000, and generate 1,000 datasets for each setting. We concentrate on estimation of both the left and the right turning points for , which have the true values of 1 and 2, respectively. We construct bootstrap-based confidence intervals and compute the coverage probability based on 200 bootstrap samples. The bootstrapping procedure here quantifies the uncertainty associated with estimating the endpoints of coefficient regions, which differs from the purpose of sparse confidence intervals as discussed in Section 3.2. More specifically, we adopt a percentile- method (Hall, 1992), in conjunction with a local false discovery rate (FDR) control method (Efron et al., 2015), for constructing the confidence intervals by eliminating the influence of outliers. Detailed implementation can be found in Section S4 of the Web Appendix.

Table 2 presents the bias, mean squared error, and coverage probability for each setting. Our findings indicate that as increases, the coverage probability approaches 0.95 and the estimated value approaches its true value. We have further examined using a threshold of 0.1 for local FDR control. Our numerical experience suggests that deviating from this threshold slightly affects the coverage probability, and a threshold of 0.1 provides CIs with the closest coverage probability to the nominal level, particularly as the sample size increases. Furthermore, this threshold shows robustness to variations in the shape of true coefficient functions or the domain of zero regions.

Table 2:

Simulation results for the point estimates and confidence intervals of the turning points

| Cov | CI for | CI for | Bias1 | Bias2 | MSE1 | MSE2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 1.04 (0.12) | 1.96 (0.11) | (0.83, 1.22) | (1.79, 2.17) | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Ind | 500 | 1.02 (0.07) | 1.98 (0.07) | (0.86, 1.14) | (1.85, 2.14) | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 1000 | 1.01 (0.05) | 1.99 (0.04) | (0.88, 1.11) | (1.90, 2.11) | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 200 | 1.03 (0.12) | 1.97 (0.12) | (0.82, 1.22) | (1.78, 2.19) | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| CS | 500 | 1.01 (0.07) | 1.98 (0.08) | (0.85, 1.14) | (1.85, 2.15) | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 1000 | 1.00 (0.05) | 1.99 (0.04) | (0.87, 1.10) | (1.90, 2.13) | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 200 | 1.03 (0.12) | 1.97 (0.12) | (0.80, 1.21) | (1.79, 2.19) | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| AR1 | 500 | 1.01 (0.07) | 1.98 (0.08) | (0.85, 1.14) | (1.85, 2.16) | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 1000 | 1.00 (0.05) | 2.00 (0.05) | (0.87, 1.10) | (1.90, 2.13) | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

(left endpoint) and (right endpoint) show the estimated values for endpoints with parenthesis indicating the standard deviation from 1,000 simulations; the right and left limits of CIs are the averages of the 1,000 CIs.

5. Analysis of the Preoperative Opioid Use Data

We apply the proposed method to analyze the data of preoperative patients, collected from 2010 to 2016 as part of the Michigan Genomics Initiative and Analgesic Outcome Study (Hilliard et al., 2018). The analyzable data contain 27,367 patients, along with the records of preoperative opioid use and pre-surgical characteristics (see Table 4 in the Supplementary Material). Risk factors associated with preoperative opioid use include pain severity, Fibromyalgia survey score (on a scale of 0 to 30 measuring centralized pain) and American Society of Anesthesiology score [ASA; on a scale of 0 (perfect) to 4 (worst) measuring health conditions] (Hilliard et al., 2018). Body mass index, which may reflect an individual’s socioeconomic status (Sundquist and Johansson, 1998) as well as overall fitness (Aires et al., 2008), can be a major effect modifier for these risk factors. With the daily dose level of preoperative opioid use, measured in morphine milligram equivalents (MME), as the outcome , we study if and how BMI modifies the associations of these risk factors with .

We initially fitted a varying coefficient model, with BMI as the index variable, by expanding the coefficient functions as linear combinations of cubic B-spline basis functions, a commonly used approximation approach (Eilers and Marx, 2010). The preliminary analysis showed that the effects of these factors tend to vary by BMI, as seen from Figure 3(a). We suspect that zero-effect regions might exist around the transition points, where the effects switch directions or where the estimates were near 0. To more properly characterize the possible BMI-dependent effects and identify the corresponding zero-effect regions, we apply the proposed STV model (1).

Figure 3:

3(a): Estimation results (I) for the preoperative opioid use data using the B-spline method and the STV method: the black solid lines are the estimated coefficient function curves for each variable; the dotted lines are the pointwise (sparse) confidence intervals.

3(b): Estimation results of zero region endpoints of ASA (3 or 4).

Aside from the outcome of the daily dose of opioid, the covariates in the model include categorical variables, such as sex, race, depression status, anxiety status, alcohol use, apnea status, illicit drug use, tobacco use, and ASA score (< 3 vs ⩾ 3), as well as continuous variables, such as age, worst pain score, Charlson comorbidity index (a weighted combination of comorbidity conditions), Fibromyalgia survey scores, average overall body pain score, and life satisfaction score (higher values meaning more satisfied with life). BMI, ranging from 15.0 to 55.0, is used as . We set the initial values required by STV to be the estimates from a linear regression model and set the thresholding parameter to be half of the absolute value of the corresponding coefficient estimate from this model, which works well in simulations. The knots of B-spline are equally spaced over the range of BMI, while the number of basis functions, , is determined by minimizing the 10-fold cross-validation error in (6) over a candidate set of {6, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24}. We set the penalty parameter to be .

We also apply the regular B-spline method for comparisons. When implementing it, we use the same spline bases as in STV. However, we do not apply the local polynomial method to analyze the data as the method cannot handle a dataset with more than 27 thousand observations. Moreover, the simulation results indicate that the local polynomial method in general under-performs STV and the B-spline method.

Figures 3(a) and 3(b) reveal that the estimates obtained by the B-spline method have larger variations near the boundary and cannot detect zero-effect regions, whereas STV can detect zero-effect regions and produce stable estimates even near the boundary. For example, both STV and the regular B-spline method detect significant impacts of pain severity over the entire BMI region, but STV produces much tighter confidence intervals at the two ends of the BMI spectrum; when BMI>43, the regular B-spline method estimates that the worse ASA condition (>3) even has a protective effect, which is not biologically plausible. In contrast, STV detects a zero-effect region for ASA when BMI>43. However, in Figure 3(b), the confidence intervals for the turning points, especially the left turning point, are wide. This is primarily because the number of patients with a BMI > 40 is limited. Therefore, when the confidence intervals include the other endpoints, we should exercise caution when determining the existence of the zero region or the sufficiency of information to draw a conclusion.

For ease of presentation, Table 3 summarizes the effects of risk factors stratified by the BMI categories, < 30.0 (non-obesity), 30.0 – 45.0 (obesity), and > 45.0 (severe obseity), and identifies several patterns of impacts on opioid use. The classification in the table is based on the estimates of the effects and their significance as illustrated in Figure 3(a).

Table 3:

Effects of risk factors by BMI categories.

| BMI category | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (<30.0) | (30.0 - 45.0) | (> 45.0) | |

| Pain severity | +* | +* | +* |

| Fibromyalgia score | +* | +* | +* |

| Tobacco use | +* | +* | +* |

| ASA >= 3 | +* | +* | 0 |

| Illicit drug use | +* | +* | +* |

| Apnea | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alcohol | 0 | 0 | +* |

| Anxiety | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | +* | +* | + |

| Sex (male) | + | +* | +* |

| Age | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Race (black) | +* | 0 | 0 |

| Life satisfaction | − * | − * | 0 |

| Charlson comorbidity | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: 0: no effects; +/−: positive/negative

significant

When BMI is less than 30.0, Fibromyalgia survey scores, ASA, tobacco, depression, and race have significantly positive effects on opioid use and life satisfaction has a significantly negative effect, indicating that among the patients with BMI less than 30.0, those with more severe central pain, worse health conditions, smoking history, or depression may tend to take more opioids than those without, whereas those with higher life satisfaction scores tend to consume less opioids than those with lower scores.

For patients whose BMI was between 30.0 and 45.0, Fibromyalgia survey scores, tobacco use, illicit drug use, ASA, depression, and life satisfaction remain to be significantly associated with opioid use, suggesting that obese patients with these adverse conditions tend to take more opioids than the obese patients without these adverse conditions. But race is no longer associated with opioid use among these patients, whereas sex is significantly associated with opioid use. That is, among those whose BMI was between 30.0 and 45.0, male patients tend to consume more opioids than female patients.

Finally, for patients with BMI larger than 45.0, most of the risk factors remain to be significantly associated with opioid use, with the notable exception of ASA. Also, in contrast to patients with a lower BMI, alcohol drinking has become a significant risk factor among patients with BMI greater than 45.0. The findings are consistent with the previous studies (Bartels et al., 2018), which have reported that the ASA category is significantly related to opioid use only among the non-obese patients, and alcohol use may significantly increase the odds of opioid use only for obese patients, but has no effects among the normal weight or overweight patients.

In summary, leveraging a large-scale dataset, we have examined the conjectures proposed from the previous literature (Hooten et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2004; Correa et al., 2015; Manchikanti et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2016) and, in particular, elucidated the effect changes over BMI on opioid use. The obtained results can potentially inform pain management, aid in physicians’ prescription, and eventually relieve the persistent use of opioids.

6. Discussion

To address the challenge of modeling varying coefficients with zero-effect regions, we have proposed a new soft-thresholded varying coefficient model, where the varying coefficients are piecewise smooth with zero-effect regions. We have designed an efficient estimation method and a new class of sparse confidence intervals, which extend the classical confidence intervals by accommodating the exact zero estimates. Our framework enables us to perform variable selection and detect the zero-effect regions of selected variables simultaneously, and to obtain point estimates of the varying coefficients with zero-effect regions and construct the associated sparse confidence intervals.

Due to the requirement of certain smoothness in the underlying function near the endpoints of zero regions, the performance of the proposed method may deteriorate when the true coefficients become steeper around the zero points. Our future work will investigate possible remedies to address them.

Moreover, it would be of interest to examine whether the estimated endpoints of zero-regions follow the standard asymptotic theory, though our simulation study has shown that the empirical coverage probability by bootstrap-based confidence intervals closely approximated the normal level. Proving the estimates are root- consistent and asymptotically normal is technical and may be beyond the scope of our current work. We will pursue it as our future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Yuan Yang and Ziyang Pan contributed equally to the work. The work was partially supported by the NIH grants and the Precision Health Award of the University of Michigan.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Web Appendices, Tables, and Figures referenced Sections 2, 3 and 4 in the paper along with the implemented C++/R codes and the demonstrating simulation data are available with this paper at the Biometrics website on Wiley Online Library.

Data Availability Statement

The Michigan Genomics Initiative and Analgesic Outcome Study data that support the findings in this paper are available on request. Please visit https://precisionhealth.umich.edu/our-research/michigangenomics/ for more details.

References

- Aires L, Silva P, Santos R, Santos P, Ribeiro J, Mota J, et al. (2008). Association of physical fitness and body mass index in youth. Minerva Pediatrica 60, 397–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels K, Fernandez-Bustamante A, McWilliams SK, Hopfer CJ, and Mikulich-Gilbertson SK (2018). Long-term opioid use after inpatient surgery–a retrospective cohort study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 187, 61–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlinet A and Thomas-Agnan C (2011). Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Spaces in Probability and Statistics. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Breheny P and Zeng Y (2019). grpreg: Regularization Paths for Regression Models with Grouped Covariates. R package version 3.2-1. [Google Scholar]

- CDCP (2007). Unintentional poisoning deaths – United States, 1999-2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 56, 93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CR, Davis J, Donaldson GW, Naylor J, and Winchester D (2011). Postoperative pain trajectories in chronic pain patients undergoing surgery: The effects of chronic opioid pharmacotherapy on acute pain. The Journal of Pain 12, 1240–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M-Y, Honda T, Li J, Peng H, et al. (2014). Nonparametric independence screening and structure identification for ultra-high dimensional longitudinal data. The Annals of Statistics 42, 1819–1849. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M-Y, Honda T, and Zhang J-T (2016). Forward variable selection for sparse ultra-high dimensional varying coefficient models. Journal of the American Statistical Association 111, 1209–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C-T, Rice J. a., and Wu CO (2001). Smoothing spline estimation for varying coefficient models with repeatedly measured dependent variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association 96, 605–619. [Google Scholar]

- Correa D, Farney RJ, Chung F, Prasad A, Lam D, and Wong J (2015). Chronic opioid use and central sleep apnea: A review of the prevalence, mechanisms, and preoperative considerations. Anesthesia & Analgesia 120, 1273–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cron DC, Englesbe MJ, Bolton CJ, Joseph MT, Carrier KL, Moser SE, Waljee JF, Hilliard PE, Kheterpal S, and Brummett CM (2017). Preoperative opioid use is independently associated with increased costs and worse outcomes after major abdominal surgery. Annals of Surgery 265, 695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoho DL (1995). De-noising by soft-thresholding. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 41, 613–627. [Google Scholar]

- Donoho DL and Johnstone JM (1994). Ideal spatial adaptation by wavelet shrinkage. Biometrika 81, 425–455. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Turnbull B, and Narasimhan B (2015). locfdr: Computes Local False Discovery Rates. R package version 1.1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Eilers PH and Marx BD (2010). Splines, knots, and penalties. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics 2, 637–653. [Google Scholar]

- Eilers PHC and Marx BD (1996). Flexible smoothing with B-Splines and penalties. Statistical Science 11, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Eubank RL, Huang C, Maldonado YM, Wang N, Wang S, and Buchanan RJ (2004). Smoothing spline estimation in varying-coefficient models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 66, 653–667. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Ma Y, and Dai W (2014). Nonparametric independence screening in sparse ultra-high-dimensional varying coefficient models. Journal of the American Statistical Association 109, 1270–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J and Zhang W (1999). Statistical estimation in varying coefficient models. The Annals of Statistics 27, 1491–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Goesling J, Moser SE, Zaidi B, Hassett AL, Hilliard P, Hallstrom B, Clauw DJ, and Brummett CM (2016). Trends and predictors of opioid use following total knee and total hip arthroplasty. PAIN 157, 1259–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, and Kaplan K (2004). Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 61, 807–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P (1992). Effect of bias estimation on coverage accuracy of bootstrap confidence intervals for a probability density. The Annals of Statistics 20, 675 – 694. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T and Tibshirani R (1993). Varying-coefficient models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 55, 757–796. [Google Scholar]

- He K, Lian H, Ma S, and Huang JZ (2018). Dimensionality reduction and variable selection in multivariate varying-coefficient models with a large number of covariates. Journal of the American Statistical Association 113, 746–754. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard PE, Waljee J, Moser S, Metz L, Mathis M, Goesling J, Cron D, Clauw DJ, Englesbe M, Abecasis G, and Brummett CM (2018). Prevalence of preoperative opioid use and characteristics associated with opioid use among patients presenting for surgery. JAMA Surgery 153, 929–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooten WM, Shi Y, Gazelka HM, and Warner DO (2011). The effects of depression and smoking on pain severity and opioid use in patients with chronic pain. PAIN® 152, 223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover DR, Rice JA, Wu CO, and Yang L-P (1998). Nonparametric smoothing estimates of time-varying coefficient models with longitudinal data. Biometrika 85, 809–822. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Breheny P, and Ma S (2012). A selective review of group selection in high-dimensional models. Statistical Science 27, 481 – 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JZ, Wu CO, and Zhou L (2002). Varying-coefficient models and basis function approximations for the analysis of repeated measurements. Biometrika 89, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Huang JZ, Wu CO, and Zhou L (2004). Polynomial spline estimation and inference for varying coefficient models with longitudinal data. Statistica Sinica 14, 763–788. [Google Scholar]

- James GM, Wang J, Zhu J, et al. (2009). Functional linear regression that’s inter-pretable. The Annals of Statistics 37, 2083–2108. [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Reich BJ, and Staicu A-M (2018). Scalar-on-image regression via the soft-thresholded Gaussian process. Biometrika 105, 165–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ER, Mammen E, et al. (2016). Local linear smoothing for sparse high dimensional varying coefficient models. Electronic Journal of Statistics 10, 855–894. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Sun DL, Sun Y, Taylor JE, et al. (2016). Exact post-selection inference, with application to the lasso. The Annals of Statistics 44, 907–927. [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Ke Y, and Zhang W (2015). Model selection and structure specification in ultra-high dimensional generalised semi-varying coefficient models. The Annals of Statistics 43, 2676–2705. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Li R, and Wu R (2014). Feature selection for varying coefficient models with ultrahigh-dimensional covariates. Journal of the American Statistical Association 109, 266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti L, Damron K, McManus C, and Barnhill R (2004). Patterns of illicit drug use and opioid abuse in patients with chronic pain at initial evaluation: A prospective, observational study. Pain Physician 7, 431–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason L, Baxter J, Bartlett P, and Frean M (1999). Boosting algorithms as gradient descent. In Solla S, Leen T, and Müller K, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 12, pages 512–518. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pivec R, Issa K, Naziri Q, Kapadia BH, Bonutti PM, and Mont MA (2014). Opioid use prior to total hip arthroplasty leads to worse clinical outcomes. International Orthopaedics 38, 1159–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JO and Dalzell CJ (1991). Some tools for functional data analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 53, 539–561. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JO and Silverman BW (2007). Applied Functional Data Analysis: Methods and Case Studies. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schug SA and Raymann A (2011). Postoperative pain management of the obese patient. Best Practice and Research Clinical Anaesthesiology 25, 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker L (2007). Spline Functions: Basic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman BW (1985). Some aspects of the spline smoothing approach to non-parametric regression curve fitting. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 47, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Song R, Yi F, and Zou H (2014). On varying-coefficient independence screening for high-dimensional varying-coefficient models. Statistica Sinica 24, 1735. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone CJ (1986). The dimensionality reduction principle for generalized additive models. The Annals of Statistics 14, 590–606. [Google Scholar]

- Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, and Mackey S (2016). Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Internal Medicine 176, 1286–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundquist J and Johansson S-E (1998). The influence of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and lifestyle on body mass index in a longitudinal study. International Journal of Epidemiology 27, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J and Tibshirani R (2018). Post-selection inference for-penalized likelihood models. Canadian Journal of Statistics 46, 41–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani RJ, Taylor J, Lockhart R, and Tibshirani R (2016). Exact post-selection inference for sequential regression procedures. Journal of the American Statistical Association 111, 600–620. [Google Scholar]

- UNDOC (2014). World Drug Report 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wahba G (1990). Spline Models for Observational Data, volume 59. Philadelphia: SIAM. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Liu X, Liang H, and Carroll RJ (2011). Estimation and variable selection for generalized additive partial linear models. Annals of Statistics 39, 1827–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F, Huang J, and Li H (2011). Variable selection and estimation in high-dimensional varying-coefficient models. Statistica Sinica 21, 1515–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CO, Yu KF, and Chiang C-T (2000). A two-step smoothing method for varying-coefficient models with repeated measurements. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics 52, 519–543. [Google Scholar]

- Xue L and Qu A (2012). Variable selection in high-dimensional varying-coefficient models with global optimality. Journal of Machine Learning Research 13, 1973–1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wang N-Y, and Wang N (2013). Functional linear model with zero-value coefficient function at sub-regions. Statistica Sinica 23, 25–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiel MG, Stroh DA, Lee SY, Bonutti PM, and Mont MA (2011). Chronic opioid use prior to total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 93, 1988–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Michigan Genomics Initiative and Analgesic Outcome Study data that support the findings in this paper are available on request. Please visit https://precisionhealth.umich.edu/our-research/michigangenomics/ for more details.