Abstract

Supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels are emerging biomaterials for tissue engineering, but it is difficult to fabricate multi-functional systems by simply mixing several short-motif-modified supramolecular peptides because relatively abundant motifs generally hinder nanofiber cross-linking or the formation of long nanofiber. Coupling bioactive factors to the assembling backbone is an ideal strategy to design multi-functional supramolecular peptides in spite of challenging synthesis and purification. Herein, a multi-functional supramolecular peptide, P1R16, is developed by coupling a bioactive factor, parathyroid hormone related peptide 1 (PTHrP-1), to the basic supramolecular peptide RADA16-Ⅰ via solid-phase synthesis. It is found that P1R16 self-assembles into long nanofibers and co-assembles with RADA16-Ⅰ to form nanofiber hydrogels, thus coupling PTHrP-1 to hydrogel matrix. P1R16 nanofiber retains osteoinductive activity in a dose-dependent manner, and P1R16/RADA16-Ⅰ nanofiber hydrogels promote osteogenesis, angiogenesis and osteoclastogenesis in vitro and induce multi-functionalized osteoregeneration by intramembranous ossification and bone remodeling in vivo when loaded to collagen (Col) scaffolds. Abundant red blood marrow formation, ideal osteointegration and adapted degradation are observed in the 50% P1R16/Col scaffold group. Therefore, this study provides a promising strategy to develop multi-functional supramolecular peptides and a new method to topically administrate parathyroid hormone or parathyroid hormone related peptides for non-healing bone defects.

Keywords: Supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels, Parathyroid hormone, Self-assembly, Co-assembly, Bone tissue engineering

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

This work proposed bioactive polypeptides could be coupled to basic supramolecular peptides.

-

•

PTHrP-1 coupled peptide hydrogels (P1R16/RADA16-I) were successfully prepared.

-

•

P1R16/RADA16-I hydrogels induced multi-functionalized osteoregeneration.

1. Introduction

While bone tissue shows self-healing properties after injuries, critical bone defects caused by severe trauma or surgical excision generally fail to obtain absolute union, resulting in nonunion or delayed union [1,2]. Autologous bone transplantation is currently the gold standard to treat this troublesome disease, but it may cause various complications, such as bleeding, infection and chronic pain [3]. Allogenic or xenogeneic bone transplantation are also indispensable strategies in the clinic, but they are normally correlated with detrimental inflammation and pathogen transmission, ultimately causing graft failure [4]. As a thriving therapeutic measure, bone tissue engineering shows promising potential for surgical bone repair, which combines four pillars, including scaffold materials, bioactive factors, biophysical stimuli and repair cells [5,6]. Bioactive factors are of great importance to be introduced to engineered regenerative system because they can exert multiple functions needed by the bone healing process [7,8].

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is an 84-amino-acid polypeptide secreted by the parathyroid gland, which can exert multiple functions including osteogenesis, angiogenesis, and bone remodeling [9]. PTH1-34, also named teriparatide, is the first 34 amino acids of the N-terminal of PTH, exerting nearly identical effects with PTH for bone tissue [10]. It has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis as an anabolic drug [11,12]. Intermittent subcutaneous injection of PTH1-34 has also been used to promote bone repair in preclinical trials [13]. However, daily injection of PTH1-34 is generally related to low patient compliance, high care costs and systemic adverse effects. Therefore, topical administration of PTH1-34 for local bone repair is superior to the systemic treatment, but it typically causes catabolic bone resorption because of the excessive activation of osteoclasts [14]. Therefore, three strategies have been developed for the topical application of PTH for bone regeneration. The first strategy is to fabricate pulsatile or continuous + pulsatile PTH delivery systems. However, the pulsatile delivery system is additionally placed outside the bone defect, so it is possible to induce heterotopic bone regeneration in practical applications [15,16]. The continuous + pulsatile delivery system allows the release of PTH by thermosensitive microspheres stimulated by near-infrared (NIR), but high temperature (45 °C) stimulated by NIR stimulation once a day may cause the loss of peptide activity, tissue damage and low patient compliance [14,17]. The second strategy is to locally sustain the release of PTH related peptides (PTHrPs) with enhanced osteogenesis and decreased osteoclastogenesis. Thus, PTHrP-1 and PTHrP-2 were developed and loaded to porous scaffolds, which promoted the healing of bone defects when topically released [[18], [19], [20]]. And PTHrP1-37 and abaloparatide, which are derived from PTH related protein, are also locally administrated for bone repair [21,22]. However, the initial relatively rapid release still exists, and peptides are directly exposed to the in vivo enzymatic environment, which are easily degraded by enzymes in the body. The third strategy is to anchor PTH prodrugs (such as TGplPTH1–34 [23,24] and cys-PTH1-34 [25,26]) to the side end of the polymer material through the N-terminal linker, which promote bone regeneration with the degradation of the scaffold material and the exposure or release of PTH1-34. However, the process to fabricate PTH-coupled materials is complicated, which includes two steps: PTH prodrug synthesis and chemical coupling of the PTH prodrug. Nevertheless, direct synthesis of PTH related supramolecular peptides which directly assemble into supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels (SPNHs) is becoming possible.

SPNHs are assembled by rationally designed supramolecular peptides through noncovalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic effects [27]. Basic supramolecular peptides that form building blocks can be easily functionalized during solid-phase peptide synthesis. Namely, bioactive motifs can be directly coupled to the lateral end to fabricate functional supramolecular peptides, which could further assemble into nanofiber hydrogels with or without basic supramolecular peptides. From the ionic-complementary self-assembling peptide group, RADA16-Ⅰ (also known as RADA16, Ac-RADARADARADARADA-NH2), one of common supramolecular peptides, has been used in the clinic for wound healing and in preclinical trials for bone repair [[28], [29], [30]]. To fabricate functional systems, assembling one bioactive motif coupled RADA16 with the basic RADA16 was generally adopted. For example, A bioactive peptide (EVYVVAENQQGKSKA) derived from neural cell adhesion molecule was coupled to RADA16, which was then assembled with RADA16 to form hydrogels [31]. The results showed that the functional hydrogel promoted the proliferation and migration of spinal cord-derived neural stem cells. Another study fabricated a functional hydrogel by assembling RADA16 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) derived peptide (KLTWQELYQLKYKGI) coupled RADA16, and found that the hydrogel apparently promoted angiogenesis when compared with the RADA16 hydrogel [32]. However, these grafted peptides are short fragments of extracellular matrix proteins or growth factors, which fail to simulate all functions and bioactivities [33,34]. Other common protein-derived short peptides which have been coupled to RADA16 for tissue repair include RGD derived from fibronectin [35], IKVAV derived from laminin [36], and RGIDKRHWNSQ derived from brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [37]. In addition, there are also some peptides discovered through a phage display technology, and the mostly common peptides that have been coupled to RADA16 for tissue healing were bone marrow homing peptides such as PFSSTKT [38] and SKPPGTSS [39]. However, the function of peptides designed by the phage display technology is limited because they generally target specific substrates during peptide identification [40,41]. In recent years, dual-functionalized hydrogels were developed by co-assembling the basic RADA16 with two RADA16-based functional supramolecular peptides coupling two different motifs. For example, a dual-functional hydrogel was fabricated by co-assembling RADA16 with RADA16-G-PRGDSGYRGDS for cell adhesion and RADA16-GGGG-KLTWQELYQLKYKGI for angiogenesis [42]. And the hydrogel was found to promote dental pulp tissue regeneration by stem cell adhesion and angiogenesis [42]. Another dual-functionalized hydrogel was also developed for peripheral nerve regeneration, which was fabricated by co-assembling RADA16 with two functional supramolecular peptides, RADA16 coupled with the BDNF derived peptide (RGIDKRHWNSQ) for neurite outgrowth and RADA16 coupled with the VEGF derived peptide (KLTWQELYQLKYKGI) for angiogenesis [43]. However, few studies incorporated three or more short-motif-coupled supramolecular peptides based on RADA16 into hydrogel systems. The overall proportion of motif-coupled supramolecular peptides based on RADA16 will increase when increasing their types, but relatively abundant motifs generally hinder nanofiber cross-linking or the formation of long nanofiber [44,45]. It has been reported that when the proportion of motif-coupled RADA16 reached 80%, the hydrogel could not form due to the formation of an evenly distributed nanofiber network but not an interlinked network [45]. When the motif coupled RADA16 accounts for 100%, the hydrogel failed to form because they did not form long nanofibers, but short nanofibers or even small nanoparticles [45]. Nevertheless, coupling multi-functional bioactive factors (mainly including bioactive proteins and bioactive polypeptides) is a potential strategy to fabricate multi-functional supramolecular peptides, which may form multi-functional SPNHs after assembly. For bioactive proteins, the long amino acid sequence leads to difficulties in synthesis and purification as well as high price, so they are not suitable for covalent coupling to the side ends of the RADA16. However, bioactive polypeptides also exert a variety of biological activities, and their amino acid sequences are relatively short, which indicates that bioactive polypeptides are more likely to be grafted to the side of the RADA16 than bioactive proteins. PTH1-34 is a prospective candidate because of its relatively few residues, which exhibited bioactivities similar to those of PTH, including osteogenesis, angiogenesis and bone remodeling. PTHrP-1 with a phosphorylated serine at the N-terminus and three aspartic acids at the C-terminus is the further optimization of PTH1-34, which shows enhanced osteogenesis and relatively reduced osteoclastogenesis [18]. Therefore, PTHrP-1 may be superior to PTH1-34 for topical bone repair.

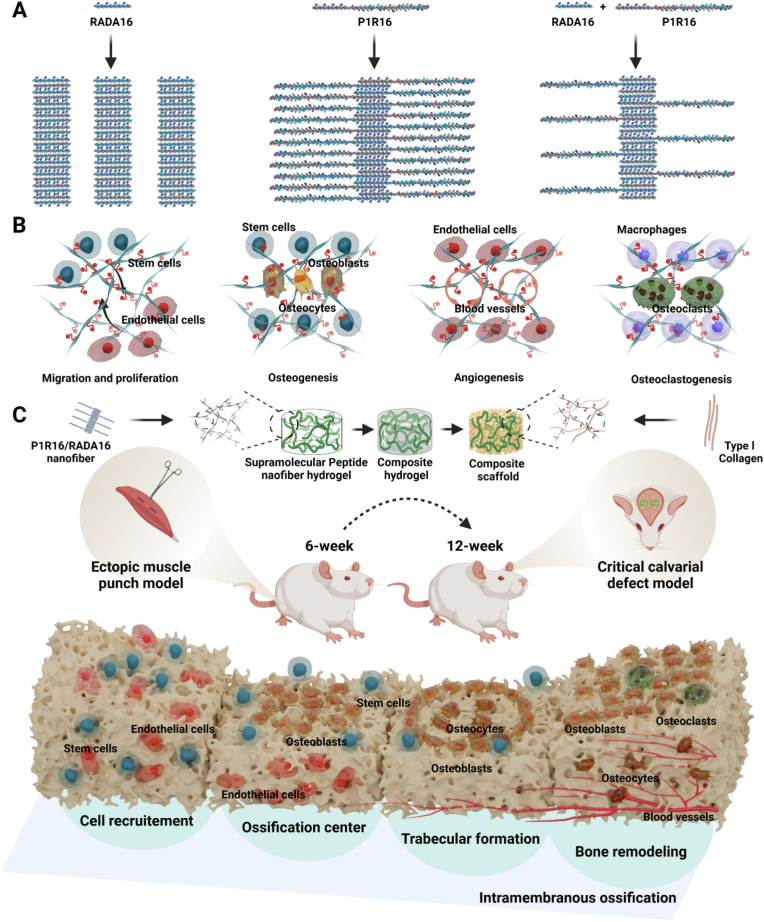

On the basis of the above logic, we developed a multi-functional supramolecular peptide by coupling PTHrP-1 to RADA16 via solid-phase synthesis, which could be used to fabricate multi-functional systems for topical bone regeneration by intramembranous ossification and bone remodeling. This group was termed PTH related supramolecular peptides, and the peptide was named P1R16. It was amazingly found that P1R16 could self-assemble into long nanofibers up to a few microns with higher height and wider width than RADA16 nanofibers, and the peptide retained osteoinductive activity. SPNHs were fabricated by co-assembly P1R16 with RADA16 in different proportions (Scheme 1A). Moreover, this study investigated the multiple functions of cell proliferation, cell migration, osteogenesis, angiogenesis, and osteoclastogenesis induced by SPNHs with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios (Scheme 1B). The SPNHs were then incorporated to collagen hydrogels by a sandwich strategy and lyophilized to obtain multi-functional composite scaffolds. The ossification pattern and bone regeneration effects were investigated by a sequential rat muscle punch model and a rat critical bone defect model. It was found that the composite scaffolds induced bone regeneration by intramembranous ossification and bone remodeling (Scheme 1C). And the 50% P1R16/Col scaffolds even completely promote bone defect healing with abundant red blood marrow formation, ideal osteointegration and adapted degradation. Therefore, the design of P1R16 may inspire the fabrication of multi-functional supramolecular peptides. And coupling PTHrP-1 to hydrogel matrix by co-assembly P1R16 and RADA16 is a new strategy to topically administrate PTH or PTHrPs for osteoregeneration.

Scheme 1.

Assembly and application of a novel parathyroid hormone (PTH) related supramolecular peptide, P1R16, to induce multi-functionalized osteoregeneration. (A) Self-assembly and co-assembly of RADA16 and P1R16. (B) Multiple functions of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels assembled by P1R16 and RADA16. (C) Fabrication of composite scaffolds and implantation to an ectopic muscle punch model and a critical calvarial defect model to induce multi-functionalized osteoregeneration.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Culture medium including Alpha-modified Eagle's medium (αMEM) and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) were purchased from Procell Life Science&Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate buffer saline (PBS), and 0.25% trypsin-EDTA were obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. MA, USA). Acetic acid and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Sinpharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Proteinase K, type Ⅰ collagenase, recombinant receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), dialysis bags, ascorbic acid, dexamethasone, β-glycerophosphate were purchased from Solarbio Life Science Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Transwell inserts and Matrigel were supplied by Corning (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA). The live/dead cell staining kit were purchased from BestBio Biotechnologies (Shanghai, China). Cell counting kit 8 (CCK8), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assay kits, ALP staining kits, actin-tracker red-594, and DAPI staining solution were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). Staining solution kits for Alizarin Red S (ARS), Von Kossa and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), paraformaldehyde solution as well as EDTA decalcification solution were obtained from Servicebio Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The peptides (P1R16, RADA16 and PTHrP-1) were supplied by Bankpeptide Ltd. (Hefei, China). And PTH1-34 was purchased from ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd. (Ness-Ziona, Israel).

2.2. Synthesis and characterization of P1R16

Fmoc/tBu solid-phase peptide synthesis was adopted to obtain P1R16. Specifically, Rink Resin was used for peptide elongation from the C-terminal to the N-terminal. The Fmoc group was removed by the 20% piperidine/DMF solution. Fmoc protected amino acids were added sequentially to the reaction system, with the carboxy group activated by NMM and HBTU. The obtained peptide was released by cracking reagent from the Resin, which was then precipitated by cold ether. The purification and purity verification of the synthesized P1R16 was adopted by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, LC-20AT, Shimadzu, Japan). A mass spectrometer (MS, LCMS2020, Shimadzu, Japan) was also used to obtain molecular weight information. To visualize the molecular design of P1R16, the section of RADA16 was directly constructed by ChimeraX software (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/), while the section of PTHrP-1 was modeled by modeleller plug for a sequence alignment pair-homologous modeling method. Finally, the two section were combined by the flexible linker (two glycine molecules) for P1R16.

2.3. Characterization of supramolecular structures assembled by P1R16 and RADA16

Peptide powders of P1R16 and RADA16 were separately dissolved in sterile Milli-Q water to obtain 1.0% w/v peptide stock solutions, which were subjected to 30 min sonication to lower viscosity and promote peptide dispersion. Then, gel-forming peptide precursors with different proportions of P1R16 (0%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 100% w/w) were prepared by blending RADA16 and P1R16, which were further mixed with isopycnic 2 × PBS (pH 7.4) to obtain SPNHs at a concentration of 0.5% w/v. The mixtures were then placed at 4 °C for at least 6 h to ensure the gelation of mixed peptide solutions. After gelation, 1× PBS was added and removed trice more to equilibrate the hydrogel to physiological pH. Macroscopic images of inverted and tilted hydrogels were obtained by a digital camera (80D, Canon, China). To further confirm the formation of SPNHs containing 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16, the hydrogels were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 6 h and then dehydrated by a graded ethanol series. The samples were then precooled at −20 °C and freeze-dried, and the morphologies of the hydrogel matrix were observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss GeminiSEM 500, Carl Zeiss Jena, Germany) after spraying gold. Since 100% P1R16 did not form hydrogel structure, the 100% P1R16 liquid was set on the mica sheet. After rinsed by Milli-Q water, the mica sheet was surrounded by conductive tape and sprayed with gold. The SEM was also adopted to detect the microstructure the 100% P1R16.

The detailed morphology of peptide nanofibers assembled by P1R16 and RADA16 was investigated by atomic force microscopy (AFM, SPM-9700HT, SHIMADZU, Japan). Hydrogel matrices were diluted 5 times with sterile Milli-Q water. Then, 10 μL samples were deposited on the fresh surface of a mica sheet for 30 s and rinsed with 100 μL Milli-Q water at least 3 times. After air drying, AFM images were taken at room temperature. The same method was adopted to investigate the self-assembling structure of P1R16 without the addition of RADA16.

A circular dichroism (CD) spectrum was implemented to obtain information on the secondary structures of peptide solutions with different proportions of P1R16 (0%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 100% w/w). They were diluted with sterile Milli-Q water to 0.1 mg/mL, which were then tested by a JASCO J-1500 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Tapan) with a 0.1 mm path length from 180 to 260 nm. The CD spectrum of PTHrP1, as a control, was also tested by the same method. The background spectrum of Milli-Q water was also collected. Raw data were transferred to mean residue ellipticity (θ) for further analysis. And the content of secondary structures can be simulated and estimated by the DichroWeb (http://dichroweb.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/html/home.shtml). Besides, 0.01% w/v peptide solutions with different proportions of P1R16 were adjusted to neutral, which were then tested by a Zetasizer (Nano ZS90, Malvern, UK) to obtain zeta potentials after sonication for 30 min. To examine the degradation characteristics of SPNHs with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios, natural degradation and enzymatic accelerated degradation were used. Two hundred microliters of SPNHs were placed in the bottom of a 0.5 mL Eppendorf tube. Eppendorf tubes with SPNHs were accurately weighted to get the initial total mass. Subsequently, two hundred microliters of sterile PBS with or without 5 unit mL−1 proteinase K was added to the top of SPNHs. The systems were then shaken by an incubator shaker at 100 rpm at 37 °C. At each scheduled time, Eppendorf tubes with residual SPNHs were accurately weighted after the supernatants were removed. Then two hundred microliters of fresh PBS with or without 5 unit mL−1 proteinase K was added to the top of residual SPNHs again until the last scheduled time.

2.4. Preparation and characterization of P1R16/Col scaffolds

Type Ⅰ collagen was isolated from rat tail tendons by acetic acid solution. First, rat tails were immersed in 75% ethanol for 30 min and 70% ethanol for another 20 min. Rat tail tendons were extracted from tails, which were then washed with sterile PBS. Then, they were dissolved in 0.1% acetic acid solution at 4 °C for 2 days. After centrifugation at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C for 45 min, the supernatant was collected and titrated with sterile 1 M NaOH solution. When the pH reached 6.5–7, it was centrifuged again at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C for 45 min, and the lower gel was collected and passed through a dialysis bag (MWCO:7000, Solarbio) for dialysis, which was then freeze-dried to obtain type I collagen.

0.5% w/v SPNHs with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios and 2% w/v type Ⅰ collagen hydrogel were preprepared, which were used to fabricate P1R16/Col scaffolds by a sandwich-like strategy. Specifically, the upper and lower layers were collagen hydrogels, and the middle layer was SPNHs. The volume ratio of the upper, middle and lower layers of the hydrogel was 2:1:2. Scaffolds for the rat limb muscle punch model were constructed in a 24-well plate. A total of 400 μl collagen hydrogel was placed on the lower layer, 200 μL SPNH was placed in the middle layer, and 400 μl collagen hydrogel was placed on the upper layer. Immediately after the addition, a syringe pillow was used to physically mix, and then ultrasound was further adopted to blend. Composite hydrogels were precooled and freeze-dried for subsequent characterization and animal experiments. An identical method was performed to prepare scaffolds for the rat critical calvarial defect model in a custom mold. Scaffolds for both animal models were visualized by a digital camera (80D, Canon, China). Scaffolds in water were used to test the shape memory property, which were compressed to the minimum and then added to αMEM culture medium. The cross-sectional morphologies of the scaffolds were observed by SEM (Zeiss GeminiSEM 500, Carl Zeiss Jena, Germany).

The porosity of the scaffolds was measured by ethanol replacement methods. Specifically, a beaker containing absolute ethanol to the scale line was accurately weighed as W1, and the freeze-dried scaffold was weighed as W0. After the scaffold was completely immersed in ethanol for 24 h, the absolute ethanol above the scale line was removed, and the beaker containing the remaining ethanol and the scaffold was precisely weighed as W2. Then, the scaffold was removed, and the mass of the remaining ethanol and the beaker was weighed as W3. The porosity was calculated according to the following formula: Porosity (%) = (W2–W3–W0)/(W1–W3) × 100%. To investigate the swelling ratio of the scaffold, the freeze-dried scaffold was weighed as W0, which was then completely soaked in PBS solution for 24 h. Then, the excess water on the surface of the scaffold was removed by dry filter paper, and the wet scaffold was weighed as W1. The swelling ratio of the scaffold was calculated by the formula: swelling ratio (%) = (W1–W0)/W0 × 100%. The diffraction patterns of the scaffolds were tested by X-ray diffraction (XRD, SmartLabSE, Rigaku, Japan) at a speed of 10° min−1. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy spectra of the scaffolds were obtained by a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (5700, Thermo, USA) with an attenuated total reflection (ATR) unit.

Based on economic considerations and the fact that a small amount of SPNH was physically loaded to a relatively large amount of collagen hydrogel, the 50% P1R16/Col scaffold was chosen for further mechanical testing, controlled release study and in vitro degradation. An Electronic Universal Testing Machine (CMT6103, MTS Systems Corporation, USA) was used to conduct compression tests and pull tests, which were performed on the basis of GB/T 1041-2008 and GB/T 13022-1991, respectively. For in vitro degradation, the freeze-dried scaffold was weighed as W0, which was then immersed in PBS and shaken by an incubator shaker at 100 rpm at 37 °C. At 1, 4, 7, and 14 days, the scaffold was removed and lyophilized to obtain its quality as Wd. The percentage of weight loss was calculated by the formula: Weight loss (%) = (Wd − W0)/W0 × 100%.

2.5. Cell acquisition and in vitro culture

Preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 subclone 14, RAW264.7 macrophages, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were isolated from Sprague‒Dawley (SD) rats at 3–4 weeks. MC3T3-E1 cells and BMSCs were cultured in αMEM medium (Procell, China) containing 10% FBS. DMEM (Procell, China) containing 10% FBS was used to culture RAW264.7 macrophages and HUVECs.

2.6. Responses of osteogenic progenitor cells to P1R16 nanofiber for osteogenic differentiation

To explore the biological activity of the PTH-related self-assembling peptide P1R16, P1R16 was dissolved in αMEM containing 10% FBS at concentrations of 0, 100, 250, 500, and 1000 ng mL−1. P1R16 assembled to form nanofibers in solution, which was confirmed by the above studies. The proliferation ability of P1R16 nanofiber on MC3T3-E1 cells was evaluated by a CCK8 assay. Briefly, 2 × 103 MC3T3-E1 cells were loaded in each well of 96-well plates and cultured for 1, 3 and 5 days. The medium in each well was replaced with fresh medium containing 10% CCK8 (Biosharp, China), which was then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The supernatant was then transferred to a new 96-well plate, which was tested by a spectrophotometric microplate reader (680, Bio-Rad, USA) to obtain the absorbance at 450 nm.

A Live/Dead Assay Kit (Bestbio, China) was used to evaluate the viability of MC3T3-E1 cells in response to P1R16 nanofiber. MC3T3-E1 cells (3 × 104) were resuspended in medium containing P1R16 nanofiber at different concentrations and then loaded into 24-well plates for 1 day. Subsequently, staining was performed using a staining solution containing 1 mM calcein-AM and 2 mM EthD-1 in the dark. An inverted fluorescence microscope (IX73, OLYMPUS, Japan) was used to observe green-stained living cells and red-stained dead cells. ImageJ software was adopted to calculate the percent of viable cells.

The migration activity of MC3T3-E1 cells was determined by Transwell chamber assay (pore size = 8 μm, Falcon, USA). A total of 5 × 104 cells were resuspended in 200 μl culture medium without FBS, which was then added to the upper chamber of a 24-well Transwell plate. Five hundred microliters of culture medium containing P1R16 nanofiber was placed in the lower chamber. After 12 h of incubation, cotton swabs were used to gently remove remaining cells on the upper chamber, and migrated cells were subjected to fixation by 4% polyformaldehyde solution for 20 min and subsequent staining by 0.1% crystal violet solution for another 30 min. An optical microscope was used to obtain results, and ImageJ software was used to quantify the migrated number of MC3T3-E1 cells.

The osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells induced by P1R16 nanofiber was determined by ALP staining, ARS staining, ALP activity and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR). αMEM medium (Procell, China) containing P1R16 nanofiber was supplemented with 50 μg mL−1 ascorbic acid (Solarbio, China), 100 nmol L−1 dexamethasone (Solarbio, China), and 10 mmol L−1 β-glycerophosphate (Solarbio, China) to obtain osteogenic induction medium.

ALP staining and ARS staining were conducted in a 24-well plate that was previously loaded with 5 × 104/well cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were then subjected to the induction of P1R16 nanofiber at different concentrations. ALP staining was conducted after induction for 7 days. The samples were gently rinsed with PBS three times and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. In the dark, a BCIP/NBT ALP Color Development Kit (Beyotime, China) was used to stain ALP-positive cells. Images were obtained by a super-resolution digital microscope. After induction for 14 days, ARS staining was performed. Cells were washed with PBS three times and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. ARS solution (Oricell, China) was used to stain fixed samples for 15 min at room temperature. Images were obtained by a superresolution digital microscope. To further quantify mineralization, 10% cetylpyridinium chloride (Sigma–Aldrich) was added to stained samples, which were subjected to shaking at room temperature for 1 h. Then, the supernatants were transferred to a 96-well plate, and the absorbance at 562 nm was detected by a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, USA).

ALP activity was measured in a 6-well plate that was previously loaded with 2 × 105 cells/well. MC3T3-E1 cells were then induced by P1R16 nanofiber at different concentrations. After 7 days of incubation, the samples were gently rinsed with PBS three times and then lysed in cell lysis buffer for Western blotting and IP without inhibitors (Beyotime, China) at 4 °C for 15 min, after which they were transferred to 1.5 mL EP tubes and subjected to high-speed centrifugation to obtain protein extracts. The protein concentrations were tested by a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, China), and the ALP activity of each sample was tested by an ALP activity kit (Beyotime, China). The results of ALP activity were defined as millimoles of p-nitrophenol produced per milligram of protein per hour.

Osteogenesis-related mRNA expression was tested by qRT–PCR, which included Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), collagen-I (Col-1), osteocalcin (OCN), and osteopontin (OPN). Briefly, 1.5 × 105 cells were loaded into each well of a 6-well plate and then induced by P1R16 nanofiber at different concentrations. After induction for 7 days, total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent, which was then reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) by a HiScript III RT SuperMix reverse transcription kit. A 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used to perform qRT–PCR. The relative expression of target genes was normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin and analyzed by the 2-△△CT method. Related primers for target genes were listed in Table S3.

2.7. Osteogenic differentiation of stem cells by SPNHs

Based on the response of MC3T3-E1 cells to different concentrations of P1R16 nanofiber, 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16/R16 SPNHs were diluted to 1000 ng mL−1 by culture medium. The experimental methods of cell proliferation, cell activity, and cell migration were similar to those of MC3T3-E1. For cell proliferation, 2 × 103/well BMSCs were loaded into a 96-well plate. To detect BMSC viability, 2 × 104/well BMSCs were loaded into a 24-well plate. In addition, 5 × 104 cells in 200 μL culture medium without FBS were added to the upper chamber of a 24-well Transwell plate to detect cell migration.

The osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs induced by the P1R16 hydrogel matrix was also determined by ALP staining, ARS staining, ALP activity and qRT–PCR. For ALP staining and ARS staining, 5 × 104 cells were placed in each well of a 24-well plate, which were tested after treatment for 7 and 14 days, respectively. For ALP activity and qRT–PCR, 2 × 105 cells were placed in each well of 6-well plates, which were tested after incubation for 7 days. The related primers for the target genes were listed in Table S4. Furthermore, Von Kossa staining and immunofluorescence staining were carried out.

Von Kossa staining was carried out in a 24-well plate that was previously loaded with 5 × 104 cells/well. BMSCs were then subjected to induction with the P1R16 hydrogel matrix for 21 days. After washing with PBS three times and immobilization with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, 5% silver nitrate staining solution was added to the samples, which were then exposed to UV light for 10 min. Images were obtained by a super-resolution digital microscope.

Immunofluorescence staining was carried out to detect the expression of RANKL and OCN in BMSCs after induction with the hydrogel matrix. Briefly, after induction for 7 days, the samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for another 10 min. The samples were then incubated in 4% BSA for 1 h to block nonspecific binding. Primary antibodies against RANKL (Proteintech, USA) and RUNX2 (Proteintech, USA) at a dilution of 1:100 were added to incubate samples at 4 °C overnight. After washing with TBST, the samples were incubated in the dark with Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, China) at a dilution of 1:200 for 1 h. The cytoskeleton and nuclei were stained with phalloidin and DAPI, respectively. An inverted fluorescence microscope (IX73, OLYMPUS, Japan) was used to obtain fluorescent images, and ImageJ software was further used to quantify the average fluorescence intensities of positive RANKL and OCN staining.

2.8. Vascularization of endothelial cells by SPNHs

SPNHs containing 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16 were diluted to 1000 ng mL−1 by culture medium for the response of HUVECs. The experimental methods of cell proliferation, cell activity, and cell migration were similar to those of MC3T3-E1. For cell proliferation, 1.5 × 103 cells were loaded into a 96-well plate. To detect HUVEC viability, 2 × 104 cells were loaded into a 24-well plate. In addition, 3 × 104 cells were loaded into the upper chamber of a 24-well Transwell plate to detect cell migration. The angiogenic capacity of the P1R16 hydrogel matrix was determined by tube formation assay, qRT–PCR and immunofluorescence staining.

A tube formation assay was performed in a 48-well plate that was previously coated with growth factor-reduced basement membrane matrix (Matrigel). Cells at a density of 3.5 × 104 cells/well were resuspended in culture medium containing different hydrogel matrices, which were then added to the surface of Matrigel. After incubation for 8 h, calcein AM (2 mM) was used to stain HUVECs. Then, the samples were observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX73, Tokyo, Japan). ImageJ was used to quantify the vessel percentage area and the number of junctions.

Angiogenic-related mRNA expression was tested by qRT–PCR, which included VEGF, hypoxia-inducing factor 1α (HIF-1α) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). Briefly, 1 × 105 cells were loaded into a 6-well plate. After induction for 7 days, total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent, which was then reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) by a HiScript III RT SuperMix reverse transcription kit. A 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used to perform qRT–PCR. The relative expression of target genes was normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin and analyzed by the 2-△△CT method. Related primers for target genes were listed in Table S5.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to detect the angiogenic expression of VEGF and CD31 in HUVECs. Briefly, after induction for 7 days, the samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for another 10 min. The samples were then incubated in 4% BSA for 1 h to block nonspecific binding. Primary antibodies against VEGF (Proteintech, USA) and CD31 (Proteintech, USA) at a dilution of 1:100 were added to incubate samples at 4 °C overnight. After washing with TBST, the samples were incubated in the dark with Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, China) at a dilution of 1:200 for 1 h. The cytoskeleton and nuclei were stained with phalloidin and DAPI, respectively. An inverted fluorescence microscope (IX73, OLYMPUS, Japan) was used to obtain fluorescent images, and ImageJ software was further used to quantify the average fluorescence intensities of positive VEGF and CD31 staining.

2.9. Osteoclast formation of macrophages by co-culture with SPNHs pretreated stem cells

Hydrogel matrix-pretreated BMSC culture medium was collected on day 3 and mixed with an equal volume of fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS and 100 ng mL−1 RANKL (Solarbio, China). The experimental methods of cell activity and cell migration are similar to those of MC3T3-E1. 3 × 103 were loaded into a 96-well plate. To detect RAW264.7 cell viability, 4.5 × 104 cells were loaded into a 24-well plate. In addition, 6 × 104 cells were loaded into the upper chamber of a 24-well Transwell plate to detect cell migration. The osteoclast formation of RAW264.7 cells was determined by TRAP staining, F-actin ring fluorescence staining, qRT–PCR and immunofluorescence staining.

TRAP staining and F-actin ring fluorescence staining were carried out in a 48-well plate that was previously loaded with 2 × 104 cells. After incubation for 6 days, the samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. For TRAP staining, the samples were then stained with a TRAP stain kit at room temperature for 1 h. An optical microscope was used to obtain images and quantify the number of TRAP-positive cells. For F-actin ring fluorescence staining, the samples were stained with TRITC-labeled phalloidin. Images were obtained by an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX73, OLYMPUS, Japan).

Osteoclastegenesis-related mRNA expression was tested by qRT–PCR, which included nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFATc1), cathepsin K (CTSK), receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B (RANK), TRAP, and dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP). Briefly, 1 × 105 cells were loaded into a 6-well plate. After induction for 6 days, total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent, which was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA by a HiScript III RT SuperMix reverse transcription kit. A 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used to perform qRT–PCR. The relative expression of target genes was normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin and analyzed by the 2-△△CT method. Related primers for target genes were listed in Table S6.

Immunofluorescence staining was carried out to detect the osteoclastic expression of NFATc1 and CTSK in RAW264.7 macrophages. Briefly, after induction for 6 days, the samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for another 10 min. The samples were then incubated in 4% BSA for 1 h to block nonspecific binding. Primary antibodies against NFATc1 (Proteintech, USA) and CTSK (Proteintech, USA) at a dilution of 1:100 were added to incubate samples at 4 °C overnight. After washing with TBST, the samples were incubated in the dark with Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, China) at a dilution of 1:200 for 1 h. The cytoskeleton and nuclei were stained with phalloidin and DAPI, respectively. An inverted fluorescence microscope (IX73, OLYMPUS, Japan) was used to obtain fluorescent images, and ImageJ software was further used to quantify the average fluorescence intensities of positive NFATc1 and CTSK staining.

2.10. Animals and surgical procedure

The use of the rat limb muscle punch model to observe ectopic bone formation and the use of the rat critical calvarial defect model for bone repair were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, and related methods in this work were performed on the basis of ‘‘Guiding Opinions on the Treatment of Animals (09/30/2006)” published by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China.

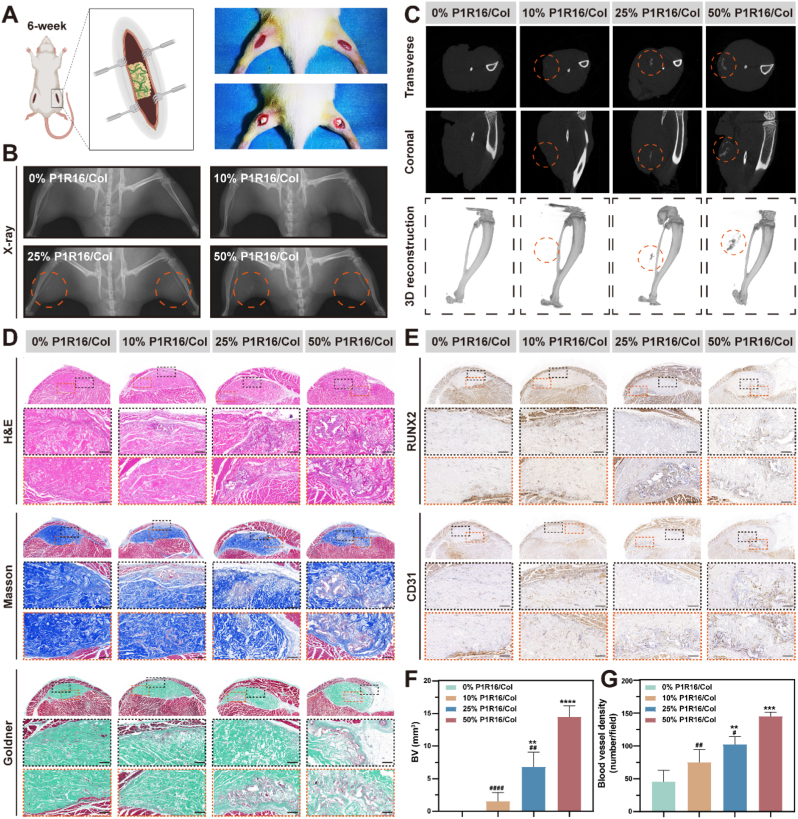

The rat limb muscle punch model was established according to a published procedure [46]. Twenty 6-week-old male SD rats were divided into four groups: (1) 0% P1R16/Col (implantation with 0% P1R16/Col scaffolds); (2) 10% P1R16/Col (implantation with 10% P1R16/Col scaffolds); (3) 25% P1R16/Col (implantation with 25% P1R16/Col scaffolds); and (4) 50% P1R16/Col (implantation with 50% P1R16/Col scaffolds). For surgery, 1% pentobarbital was used to anesthetize rats. All rats were operated on in the prone position, and a 1.5 cm incision was separately made on the bilateral limb after skin preparation and disinfection. Limb muscle punches were established by blunt dissection and then implanted with scaffolds for different groups after compression. Bilateral incisions were closed by 4-0 nylon sutures layer-by-layer. Three consecutive days after surgery, all rats were subjected to 1 mg kg−1 meloxicam and 10 mg kg−1 enrofloxacin postoperatively.

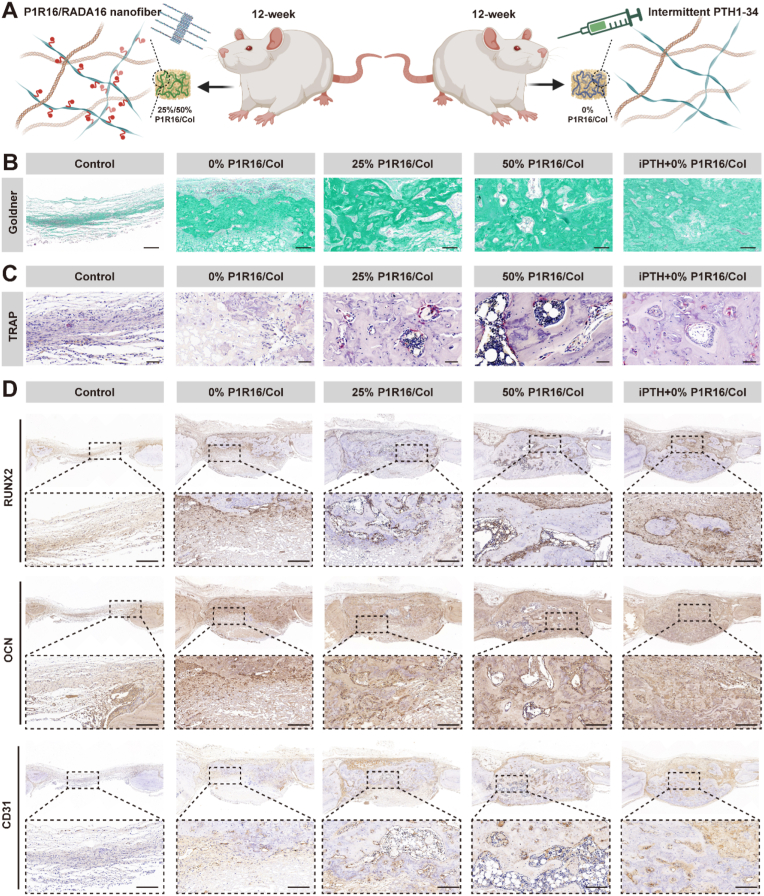

The rat critical calvarial defect model was established in 12-week-old male SD rats. Thirty SD rats were randomly divided into five groups: (1) control (implantation without scaffolds); (2) 0% P1R16/Col (implantation with 0% P1R16/Col scaffolds); (3) 25% P1R16/Col (implantation with 25% P1R16/Col scaffolds); (4) 50% P1R16/Col (implantation with 50% P1R16/Col scaffolds); and (5) iPTH+0% P1R16/Col (intermittent injection of PTH1-34 (30 μg kg−1, daily) and implantation with 0% P1R16/Col scaffolds). After being anesthetized by 1% pentobarbital (3 mL kg−1) as well as skin preparation and disinfection, all rats were operated on in the prone position and were subjected to a 1.5 cm sagittal incision on the scalp to sequentially dissect the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and periosteum. Then, an electrical bone trephine bur was used to make two full-thickness critical-sized calvarial defects (5 mm in diameter), which were then implanted with different scaffolds according to groups. The incisions were closed by 4-0 nylon sutures layer-by-layer. Three consecutive days after surgery, all rats were subjected to 1 mg kg−1 meloxicam and 10 mg kg−1 enrofloxacin postoperatively. Eight weeks after surgery, rats were euthanized by injection with an overdose of anesthetic. Then, calvarial samples were obtained for further radiographic and histological analyses.

2.11. Radiographic analyses

Rats undergoing limb muscle punch surgery were anesthetized by 1% pentobarbital (3 mL kg−1) at 5 weeks after operations, which were tested by X-ray. They were then sacrificed to obtain limb samples containing implanted scaffolds. After being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, the samples were tested by a micro-CT imaging system (SkyScan 1276 system, Bruker, Germany) under a source voltage of 45 kV, a current of 200 μA, and an aluminum filter of 0.25 mm with an image pixel size of 6.5 μm. NRecon software (Bruker, USA) was used to reconstruct the scanned images. DataViewer (Bruker, USA) and CTAn software (Bruker, USA) were used to analyze the newly formed bone volume (BV).

Rats undergoing surgery for critical calvarial defects were sacrificed at 8 weeks to obtain calvarial samples containing defects. The samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then examined by a micro-CT imaging system (SkyScan 1276 system, Bruker, Germany) under a source voltage of 45 kV, a current of 200 μA, and an aluminum filter of 0.25 mm with an image pixel size of 6.5 μm. The raw data were reconstructed by Recon software (Bruker, USA). The parameters reflecting bone regeneration were analyzed by DataViewer (Bruker, USA) and CTAn software (Bruker, USA), which included the newly formed BV, BV/tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb. N), and trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp).

2.12. Histological analyses

After being scanned by micro-CT, the limb samples and the calvarial samples were decalcified by using a 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) buffer solution (pH = 7.4) for 4 weeks at 37 °C. Then, the samples were dehydrated by a graded ethanol series and embedded in paraffin to obtain 5 μm thick sections. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome, and Goldner's trichrome staining were used to evaluate bone neoformation in limb and calvarial samples. Sections of calvarial samples were further stained with a Leukocyte Acid Phosphatase Assay kit (Sigma) to analyze osteoclastogenesis by observing TRAP-positive cells. Immunohistochemical staining was also performed to assess the expression of RUNX2 and OCN reflecting osteogenesis, and CD31 indicating angiogenesis. In addition, major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) of rats undergoing limb muscle punch implantation were also harvested, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, rehydrated with a graded ethanol series and embedded in paraffin. H&E staining was performed to evaluate the potential toxicity of the implanted materials in each group.

2.13. Statistical analysis

All evaluations in this study were repeated at least three times. Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences were discerned by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) coupled with Tukey's test, which were performed by SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, USA). In each experiment, a p value < 0.05 was represented by *, # or &, a p value < 0.01 was reflected by **, ## or &&, and a p value < 0.001 was reflected by ***, ### or &&&, a p value < 0.0001 was reflected by ****, #### or &&&&.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of P1R16 and supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels

The designer-functionalized PTH related supramolecular peptide, named P1R16, was synthesized by coupling the multi-functional polypeptide, PTHrP-1 (S[PO4] VSEI-QLMHN-LGKHL-NSMER-VEWLR-KKLQD-VHNF-DDD), to the C-terminus of RADA16 by a universal linker (GG), as illustrated in Fig. 1A. The successful synthesis of P1R16 was verified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry (MS). The HPLC results showed that the purity of P1R16 was 95.099% (Fig. S1 and Table S1). Depending on the MS spectrogram, the molecular weight of P1R16 was approximately 6352.20 g mol−1 by analyzing the m/z values of molecular [M + nH] nH+ ions produced from the peptide (Fig. S2). The observed molecular weight was close to its theoretical molecular weight (6352.81 g mol−1), further confirming the successful synthesis of P1R16.

Fig. 1.

Synthesis and characterization of P1R16 and supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels assembled by P1R16 and RADA16. (A) The molecular design of P1R16. (B) Macroscopic assembling structures with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios. (C) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels containing 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16 as well as SEM image of 100% P1R16 nanofiber, scale bar: 50 μm (0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16) and 200 nm (100% P1R16). (D) Atomic force microscope (AFM) images of microscopic assembling structures with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios. (E) Height curve crossed by white arrows in nanostructures assembled by pure RADA16 and P1R16. (F) Circular dichroism (CD) spectra and (G) zeta potentials of assembling structures with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios and the multi-functional polypeptide PTHrP-1. (H) Degradation curves of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels containing 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16 in the absence or presence of proteinase K. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 0% P1R16; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ####P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to PTHrP-1.

Pure P1R16, at the concentration of 0.5% w/v, failed to form a SPNH in aqueous solution induced by salt ions (Fig. 1B). Therefore, a co-assembly strategy was adopted by mixing P1R16 with RADA16. The P1R16 could assemble with RADA16 to form hydrogels when the proportion of P1R16 is less than or equal to 50%, and the stability of the hydrogel decreased with the elevated P1R16 to RADA16 ratios (Fig. 1B). To further confirm that 0–50% P1R16 assembled to form hydrogels, the morphology of SPNHs was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) after freeze drying. It was found that SPNHs containing 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16 exhibited porous structures (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the above results elucidate that SPNHs were formed when the mass ratio of P1R16 was 0%–50% w/w. Since 100% P1R16 did not form SPNHs, the sample for SEM was prepared in a different method. The peptide solution of 100% P1R16 was dropped on the mica sheet surrounded by conductive tape, which was sprayed with gold after air drying for observation. And the result showed that P1R16 self-assembled assembled into long nanofibers (Fig. 1C).

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was adopted to characterize nanostructures assembled by various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios (Figs. 1D and S3–4). It was also found that 100% P1R16 self-assembled into long nanofibers up to a few microns. The result challenged the traditional concept that functional segments (such as EVYVVAENQQGKSKA [31], PRGDSGYRGDS [44], and FRKKWNKWALSR [45]) blocked the formation of long nanofibers but formed short nanofibers or even nanoparticles. However, only a few crosslinks existed among nanofibers assembled by pure P1R16, implying that pure P1R16 failed to further assemble into peptide nanofibers. In addition, pure RADA16 (0% P1R16) also self-assembled into long nanofibers up to a few microns, but the crosslinks among nanofibers assembled by pure RADA16 were apparently more than those assembled by pure P1R16. Nanofibers assembled by RADA16 tended to form a multilayer network but not a single-layer structure assembled by P1R16. Upon the addition of P1R16, the assembled nanofiber networks were similar to those assembled by pure RADA16, in which many nanofibers entangled and tended to form a multilayer matrix. Nevertheless, thicker sections could be observed within nanofibers co-assembled by P1R16 and RADA16, which may suggest the presence of the functional motif PTHrP-1. With the increase in the P1R16 proportion, the existence of thicker sections also increased, especially for nanofibers assembled by 50% P1R16 and 50% RADA16. Moreover, it could be observed that the pure P1R16 formed aligned nanofibers, which were quite different from other nanostructures assembled by 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16 nanofibers. Potential reason may be that abundant PTHrP-1 on both sides of the 100% P1R16 nanofibers carried the same charge which may hinder the mutual cross-linking of nanofibers, thus forming aligned nanofibers. But for 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16 nanofibers, the nanofibers contained RADA16 without coupling PTHrP-1, so they formed mutually cross-linked networks. And it could be also observed that the 50% P1R16 nanofibers also presented a relatively aligned nanostructure compared to the 0%, 10% and 25% P1R16 groups, but there were still relatively more cross-linking points than the pure P1R16. In addition, the heights and widths of nanofibers assembled by pure RADA16 and P1R16 were collected by AFM. Each curve in Fig. 1E reflected the nanofibers that were crossed by white arrows in nanostructures assembled by pure RADA16 and P1R16. The results showed that nanofibers assembled by pure P1R16 were higher and wider than nanofibers assembled by pure RADA16.

Circular dichroism (CD) was further carried out to visualize the secondary structures of SPNHs with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios, nanofibers assembled by pure P1R16, and the multi-functional polypeptide PTHrP-1 (Fig. 1F). The pure multi-functional polypeptide PTHrP-1 exhibited a structure containing an α-helix with double negative peaks at 221 nm and 204 nm as well as a positive peak at 190 nm. The pure RADA16 nanofiber exhibited a typical β-sheet structure which showed two peaks: a negative peak at 216 nm showing β-sheet contents and a positive peak at 195 nm reflecting β-sheet twist [47]. The pure P1R16 nanofiber showed a similar structure to PTHrP-1, which implied that the multi-functional motif was exposed to the lateral ends of the nanofiber. The content of the α-helix and β-sheet for P1R16 was smaller than those of pure PTHrP-1 and RADA16, respectively (Table S2). When P1R16 accounted for 10%, the structure of the co-assembling nanofibers retained the β-sheet structure. Upon increasing the P1R16 proportion to 25% and 50%, the nanostructures co-assembled by P1R16 to RADA16 were between the structures of pure P1R16 and pure RADA16. Subsequently, the zeta potentials of the above systems were tested after sonication for 30 min. The zeta potentials of RADA16 nanofiber and P1R16 nanofiber were 29.4 ± 0.1 and 35.6 ± 0.3 mV, respectively (Fig. 1G). The zeta potentials of nanofibers assembled by both RADA16 and P1R16 were between the above two potentials. In contrast, the zeta potential of PTHrP-1 was −4.9 ± 0.1 mV. The results showed that PTHrP-1 was negatively charged and the systems assembled by P1R16 and RADA16 were positively charged. Since the absolute value of zeta potential for PTHrP-1 was less than 5 mV, PTHrP-1 conjugated quickly in the liquid environment due to van der Waals interparticle attraction. In contrast, the absolute values of zeta potentials for systems assembled by P1R16 and RADA16 were all above 25 mV. The results showed that the stability of the systems assembled by P1R16 and RADA16 were enhanced, which further confirmed the formation of nanostructures.

The potential assembling process of SPNHs by both P1R16 and RADA16 may be mainly attributed to the RADA16 section, which may assemble by a molecular diffusion model [47]. The RADA16 section mainly contains hydrophobic Alanine (A) and hydrophilic Arginine (R) and Aspartic acid (D). When P1R16 and RADA16 were added to the solution, they may co-assemble to form a β-sheet structure by intermolecular hydrogen bonds along the assembling backbone. Hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions may also be involved in the assembling process. The hydrophobic A may converge to the inner layer of a sandwich-like structure, while hydrophilic R and D may tend to the outer layer of a sandwich-like structure, which may be further enhanced by electrostatic interactions because they have opposite charges. PTHrP-1 may not be involved in the formation of the β-sheet fold, thus being exposed to the side ends of the nanofibers (Fig. S5).

To evaluate the biodegradation of SPNHs assembled by different P1R16 to RADA16 ratios, they were incubated in the absence or presence of proteinase K (Fig. 1H). Proteinase K is a serine protease with broad substrate specificity, which preferentially breaks down peptide bonds adjacent to the C-terminus of hydrophobic, sulfur-containing, and aromatic amino acids. And it has been widely used in previous studies to explore the degradation of peptide hydrogels in vitro [48,49]. SPNHs in different groups showed comparable digestion trends under the action of proteinase K, which were almost completely digested in ten days. However, in PBS solution without proteinase K, more than 60% of SPNHs in all groups were still maintained after 14 days of incubation, which meant that a considerable part of the peptide nanofibers anchored PTHrP-1 were retained for a long time. Meanwhile, the 50% P1R16 hydrogel in PBS solution degraded the fastest, followed by the 25%, 10% and 0% hydrogels. The phenomenon that SPNHs with elevated P1R16 to RADA16 ratios exhibited an increased degradation rate in PBS without proteinase K may be attributed to the decreased stability of SPNHs with the increase of P1R16 proportion.

3.2. Fabrication and characterization of composite scaffolds

To avoid rapid degradation by enzymes after implantation in vivo, SPNHs with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios were incorporated into collagen hydrogels by a sandwich strategy, which were then lyophilized to fabricate composite scaffolds (Fig. 2A). Visually, scaffolds for the limb muscle punch model and the critical calvarial defect model were white porous sponges (Fig. 2B). To assess the shape memory capacity of wet composite scaffolds, they were compressed to the minimum and then culture medium was added to the surface of the scaffolds. Similar to the pure collagen scaffold as previously reported [50], P1R16/Col scaffolds could also recover to their original state (Fig. 2C).

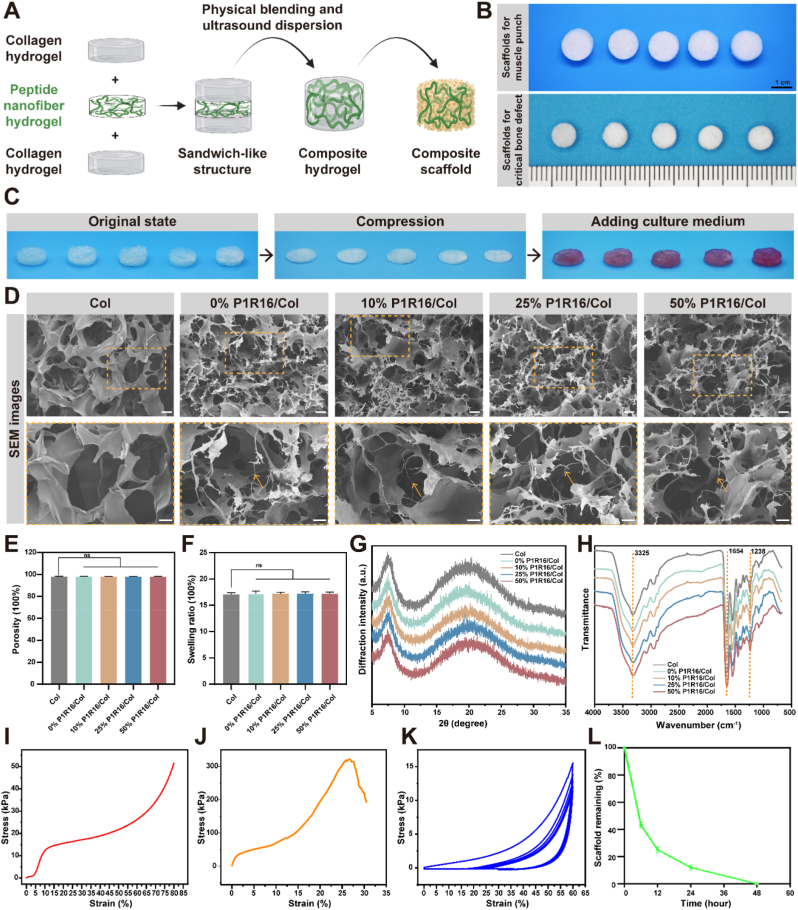

Fig. 2.

Construction and characterization of composite scaffolds. (A) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of P1R16/Col scaffolds by a sandwich-like strategy. (B) Representative macroscopic photographs of the pure collagen scaffold as well as 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16/Col scaffolds from left to right for the ectopic muscle punch model and the critical calvarial defect model. (C) Self-healing property of the pure collagen scaffold and distinctive P1R16/Col scaffolds. (D) SEM images of the pure collagen scaffold and distinctive P1R16/Col scaffolds (the orange arrows indicate the representative fiber-like structures), scale bar: 40 μm (up) and 20 μm (down). (E) Porosity and (F) swelling ratio of the pure collagen scaffold and distinctive P1R16/Col scaffolds. (G) X-ray diffraction (XRD) and (H) Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) characterization of the pure collagen scaffold and distinctive P1R16/Col scaffolds. (I) Compressive stress–strain curve, (J) tensile stress–strain curve and (K) cyclic compressive stress–strain curve of the 50% P1R16/Col scaffold. (L) Degradation curve of the 50% P1R16/Col scaffold in the presence of type Ⅰ collagenase.

SEM was used to observe the porous structure of different scaffolds. As shown in Fig. 2D, the pure collagen scaffold and composite P1R16/Col scaffolds exhibited interconnected porous network structures with pore sizes of 108.77 ± 41.91 μm, 96.70 ± 27.47 μm, 97.39 ± 32.90 μm, 96.70 ± 27.47 μm, 97.23 ± 27.96 μm, and 97.35 ± 26.54 μm. Fiber-like structures could be observed in P1R16/Col scaffolds when compared with the pure collagen scaffolds. In addition, Fig. 2E shows that the porosities of the pure collagen scaffold and P1R16/Col scaffolds were over 98%. It has been reported that high porosity and macropore size (>100 μm) are beneficial to cell infiltration, nutrient/waste transportation, bone ingrowth and vascularization [51]. Therefore, P1R16/Col scaffolds were promising for implantation in vivo. Water absorption reflected by the swelling ratio is a critical index to reflect the biological and chemical properties of polymer scaffolds. As shown in Fig. 2F, the swelling ratio of the pure collagen scaffold was 1750 ± 35%. The P1R16/Col scaffolds exhibited similar swelling ratios without significant differences from the pure collagen scaffold, 1723 ± 40%, 1720 ± 24%, 1719 ± 30%, and 1718 ± 29% for the 0%, 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16/Col scaffolds, respectively. The results showed that the introduction of SPNHs to the collagen scaffold did not affect its water absorption.

The scaffolds were further detected by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The diffraction pattern of pure collagen scaffolds was consistent with previously reported results of type Ⅰ collagen [52]. A spike was observed at approximately 8°, which indicates the longest distances between the triple helix molecular chains, and a broad peak that represented amorphous scatter due to unordered components of collagen was observed at approximately 16–25°. P1R16/Col scaffolds also exhibited diffraction patterns similar to that of the pure collagen scaffold (Fig. 2G). For the FTIR of type I collagen, the main characteristic peaks include the amide III band (N–H bending, C–N stretching and triple helical structure) at 1200~1300 cm−1, amide A band (N–H stretching) at approximately 3300 cm−1, and amide I band (C]O stretching and α-helical structure) at approximately 1660 cm−1 [52]. As shown in Fig. 2H, strong peaks at 1238 cm−1 were observed in all scaffolds, indicating that collagen in all scaffolds retained the triple helix structure. Amide A band and amide I band were observed at 3325 cm−1 and 1654 cm−1, respectively. There were no other special peaks in the P1R16/Col scaffolds, which may be attributed to that the SPNHs were amino acid organic substances like collagen and the composition of the composite scaffold was mainly type I collagen (99.375% by mass).

Based on economic considerations and the above results that P1R16/Col scaffolds exhibited similar physicochemical properties to the pure collagen scaffold, the 50% R1R16/Col scaffold was used for mechanical tests and in vitro degradation. The mechanical properties were comprehensively evaluated by compression test, pull test and cyclic compression test. The results of the compression test showed that the compression of the 50% P1R16/Col scaffold was 53 ± 25 kPa, which indicated that the scaffold should be only used for the repair of bone defects in non-weight-bearing areas (Fig. 2I). For the tensile test, it is generally required that the tensile strength of the collagen film implanted in the body is higher than 100 kPa. The tensile strength of the 50% P1R16/Col scaffold was 330 ± 39 kPa, which met the basic requirements (Fig. 2J). For the cyclic compression test, the scaffold in the wet state showed elastic property, which further confirmed the self-healing property (Fig. 2K). Furthermore, the degradation of the 50% P1R16/Col scaffold was tested under condition with or without type I collagenase. Type I collagenase is a protease dedicated to the degradation of type I collagen because it specifically recognizes the Pro-X-Gly-Pro sequence and cleaves the peptide bond between the neutral amino acid (X) and glycine (Gly) of the sequence. And it has been used for the degradation of composite Col scaffolds in the previous study [53]. The in vitro degradation study showed that the scaffold degraded slowly in vitro without type Ⅰ collagenase, and the degradation mainly occurred on the first day (Fig. S6). Under the action of type Ⅰ collagenase, the scaffold was completely degraded in 48 h (Fig. 2L). Therefore, the R1R16/Col scaffolds might ensure the migration of cells in the early stage instead of rapid hydrolysis. And the scaffolds showed satisfactory degradability, which might be completely degraded after implantation because of the enzymatic microenvironment in vivo.

3.3. Dose-dependent osteoinductive activity of P1R16 nanofiber

The critical question of coupling the multi-functional polypeptide PTHrP-1 to RADA16 is whether peptide modification retained the osteoinductive ability of PTHrP-1. MC3T3-T1 subclone 14, one of mouse preosteoblast cell lines, was used to evaluate the viability, proliferation, migration and osteogenic differentiation of 0, 100, 250, 500, and 1000 ng mL−1 P1R16 nanofiber.

Maintaining cell viability, promoting proliferation, and inducing migration are basic functions of bioactive factors for bone tissue engineering. The viability of MC3T3-E1 cells was investigated by live/dead assay, and the results showed that P1R16 nanofiber of different concentrations showed ideal cytocompatibility on account that most of MC3T3-E1 cells were viable after incubation for 24 h (Fig. 3A). The quantitative results further revealed that the survival rates of cells incubated by different concentrations were over 95% (Fig. S7). The potential reason for the low cytotoxicity is that P1R16 is entirely composed of a biocompatible amino acid sequence. The proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells was evaluated by CCK8 assay on days 1, 3, and 5. As depicted in Fig. 3C, relatively low concentrations of P1R16 nanofiber (less than 500 ng mL−1) induced cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. However, proliferation was reduced in the high concentration (1000 ng mL−1) group compared with the 500 ng mL−1 group. Further studies also demonstrated that derivatives from PTH or PTH related protein showed a dose-dependent proliferation to MC3T3-E1 cells. Moreover, the migration and infiltration of MC3T3-E1 cells was assessed by transwell migration assay under the induction of P1R16 at different concentrations. As shown in Fig. 3C, the number of stained MC3T3-E1 cells first increased and then decreased with increasing concentrations of P1R16, indicating that there was a dose-dependent relationship when the concentration was lower than 500 ng mL−1 and that the upward trend was inhibited when the concentration was higher (1000 ng mL−1). The quantitative result also confirmed the above trend (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these results revealed that the P1R16 nanofiber was biocompatible, and the optical concentration to promote proliferation and migration was 500 ng mL−1.

Fig. 3.

Dose-dependent osteoinductive activity of P1R16 Nanofiber. (A) Live/dead staining for cell viability and transwell assay for cell migration of MC3T3-E1, scale bar: 200 μm (up) and 100 μm (down). (B) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining and Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining for osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1, scale bar: 100 μm. (C) CCK8 assay for cell proliferation, (D) migration quantitative analysis, (E) ALP activity and (F) mineralization quantitative analysis and osteogenesis-related gene expression (G) RUNX2, (H) Col-1, (I) OCN and (J) OPN of MC3T3-E1. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 0 ng mL−1 P1R16; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ####P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 1000 ng mL−1 P1R16.

The osteogenic properties and mineralization of P1R16 nanofiber were assessed by ALP activity, ALP staining, ARS staining and qRT–PCR. During initial osteogenic differentiation, ALP exerts critical roles in mineralization. After 7 days of induction, ALP-positive MC3T3-E1 cells gradually increased with increasing P1R16 nanofiber concentration at 0–500 ng mL−1, but the ALP-positive area of the 1000 ng mL−1 P1R16 group was less than that of the 500 ng mL−1 group (Fig. 3B). As expected, the ALP activity in groups containing P1R16 nanofiber were significantly higher than that in the control group on day 7, and the activity was highest in the 500 ng mL−1 group (Fig. 3E). In addition, ARS staining was carried out to estimate the late state of mineralization by observing the formation of calcium nodules (Fig. 3B). In accordance with the above ALP staining and quantitative activity, the results of ARS staining also verified the dose dependence of osteogenic properties when the concentration of P1R16 nanofiber was less than 500 ng mL−1. The number of calcium nodules formed in the 1000 ng mL−1 group was less than that in the 500 ng mL−1 group. The quantitative results were consistent with the ARS staining results (Fig. 3F). Additionally, osteogenesis-related markers, including RUNX2, ALP, Col-1, OCN and OPN, were estimated at the genetic level after 7 days of intervention, among which Runx2 is a critical transcription factor during initial osteogenesis. It could further induce the transcription and expression of ALP, Col-1, OCN and OPN. As shown in Fig. 3G–J, 0–500 ng mL−1 P1R16 nanofiber induced the gene expression of osteogenic markers in a dose-dependent manner, while the 1000 ng mL−1 group induced lower osteogenic differentiation than the 500 ng mL−1 group. Therefore, these results collaboratively verified the effectiveness of P1R16 nanofiber in inducing the osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells. The osteoinductive properties showed a dose-dependent model when the concentration was less than 500 ng mL−1.

The above results showed that the capacities of P1R16 nanofiber to promote the proliferation, migration and osteogenic differentiation increased in a dose-dependent manner, but decreased at the high concentration. A similar phenomenon was also reported in a previous study which showed that a PTHrP named abaloparatide promoted the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells below 100 ng mL−1, but the capacities decreased at the concentration of 400 ng mL−1 [21]. The potential reason for the high concentration reduced the capacities may resist in the desensitization of PTH receptor [54]. And another study also reported that the expression of PTH receptor was reduced at the high concentration [23]. As far as the optimal concentration was concentrated, our previous study showed that the optimal osteogenic dose of PTHrP-1 for MC3T3-E1 cells was 100–200 ng mL−1 [55]. Another study reported that the optimal osteoinductive dose of abaloparatide was 100 ng mL−1 [21]. Therefore, the results in this study indicated that the biological activity of P1R16 was decreased compared with that of PTHrP-1, but the osteoinductive capacity of PTHrP-1 was still maintained. A previous study showed that a PTH prodrug, TGplPTH1–34 (NQEQV-SPLYL-NR-SVSEI-QLMHN-LGKHL-NSMER-VEWLR-KKLQD-VHNF), maintained biological activities but was reduced by 80 times compared to PTH1- 34 [23]. A potential reason for the relatively low reduction in biological activity of P1R16 compared with TGplPTH1–34 may be that P1R16 could assemble to form nanofibers, while TGplPTH1–34 has no assembly property. PTHrP-1 was exposed to the side ends of P1R16 nanofiber, which may be released to induce osteogenic differentiation. Another potential reason lies in the abundant phosphorylated serine epitopes in P1R16 nanofiber. It has been confirmed that phosphorylated serine in nanofibers induces osteogenic differentiation [56,57].

3.4. Osteogenic effects of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels

Stem cells, as one of important pillars of bone tissue engineering, are the seed cells to repair bone tissue [58]. Based on the above osteoinductive effects of P1R16 nanofiber on MC3T3-E1 cells, SPNHs with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios (0%, 10%, 25%, and 50% P1R16) were diluted to 1000 ng mL−1 to evaluate their effects on cell viability, proliferation, migration and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs.

Cell viability, proliferation and migration induced by SPNHs with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios were investigated by live/dead assay, CCK8 assay, and transwell migration assay, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4A, the majority of cells were viable in all intervention groups. The results of quantitative analysis also confirmed that the cell survival rates of different groups were above 95% (Fig. S8). In addition, SPNHs containing P1R16 showed strong proliferation of BMSCs on days 3 and 5, among which the 50% P1R16 SPNH exhibited the best effect of promoting cell proliferation (Fig. 4B). However, the cell proliferation result on day 1 showed no significant difference between the groups, potentially due to the short duration of the intervention. BMSC migration was shown in Fig. 4A and C. SPNHs containing 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16 promoted cell migration, and the most migrated cells were observed in the 50% P1R16 SPNH. To evaluate the osteogenic ability of SPNHs with various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios, ALP activity, ALP staining, ARS staining, Von Kossa staining, qRT–PCR, and immunofluorescence staining were applied. ALP staining was used to assess early osteogenesis, while ARS staining and Von Kossa staining were used to assess late calcium nodule formation (Fig. 4D). The results showed that SPNHs containing P1R16 significantly promoted the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs at both early and late stages and that the higher the P1R16 content was, the stronger the osteogenic induction ability. The results of ALP activity and quantitative analysis for calcium nodule formation were consistent with the osteogenic trends in the staining images (Fig. 4E–F).

Fig. 4.

Osteogenic effects of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels. (A) Live/dead staining for cell viability and transwell assay for cell migration of BMSCs, scale bar: 200 μm (up) and 100 μm (down). (B) CCK8 assay for cell proliferation and (C) migration quantitative analysis of BMSCs. (D) ALP staining, ARS staining, and Von Kossa staining for osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, scale bar: 100 μm. (E) ALP activity, (F) mineralization quantitative analysis and osteogenesis-related gene expression (G) RUNX2, (H) Col-1, (I) OCN and (J) OPN of BMSCs. (K) RANKL fluorescence intensity of BMSCs. Immunofluorescence staining of (L) RUNX2 and (M) RANKL, scale bar: 100 μm *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 0% P1R16; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ####P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 50% P1R16.

The osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs induced by SPNHs containing P1R16 was further evaluated at the gene and protein levels. The expression and transcription of osteogenesis-related gene markers, including RUNX2, Col-1, OCN and OPN, were also upregulated in the presence of P1R16 and were highest in the 50% P1R16 SPNH (Fig. 4G–J). Consistent with the RUNX2 gene expression by qRT‒PCR, the results of immunofluorescence staining also showed that SPNHs containing P1R16 promoted the expression of RUNX2, and the RUNX2 expression level of the 50% P1R16 SPNH was the highest (Fig. 4L). The quantitative analysis to detect fluorescent intensity revealed that RUNX2 expression in the 50% P1R16 SPNH was the highest, followed by the 25%, 10% and 0% P1R16 SPNHs (Fig. S9). Therefore, the above results showed that all SPNHs were biocompatible, and those assembled by both P1R16 and RADA16 showed stronger cell proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiation. A potential reason was that the existence and release of the multi-functional polypeptide PTHrP-1 at both lateral sides of the nanofibers to form SPNHs.

3.5. Angiogenic properties of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels

Angiogenesis is important for bone regeneration because of oxygen and nutrient transportation by neoformative blood vessels [[59], [60], [61]]. It has been reported that the administration of intermittent PTH1-34 promoted vascularization in fracture callus [62]. And our previous results showed that PTHrP-1 could also promote angiogenesis during bone healing when locally released from scaffolds [18]. The potential reason is the fact that PTH or PTHrPs act on endothelial cells to induce VEGF expression, which further promotes vascularization and angiogenesis [18,63]. However, the ability of SPNHs assembled by both P1R16 and RADA16 to vascularize remains unknown. Therefore, the angiogenic abilities of SPNHs assembled by various P1R16 to RADA16 ratios (0%, 10%, 25%, and 50% P1R16) were evaluated by assessing their effects of cell viability, proliferation, migration and angiogenic differentiation on HUVECs.

Cell viability was assessed by live/dead assay, which revealed that all intervention groups ensured the survival of more than 95% of HUVECs (Figs. 5A and S10). The proliferation of HUVECs was investigated by CCK8 assay as shown in Fig. 5B. It was found that SPNHs containing P1R16 promoted the proliferation of HUVECs on days 3 and 5, and the highest proliferative activity was observed in the 50% P1R16 SPNH. The transwell migration assay was used to estimate the pro-migratory activity of different SPNHs. As shown in Fig. 5A and C, HUVECs treated with SPNHs containing P1R16 showed faster migration rates, and the higher the proportion of P1R16 was, the faster the migration of HUVECs. Furthermore, the capacities of different SPNHs to induce vascularization were estimated by tube forming assay. The results of the tube forming assay revealed that capillary-like structures were formed in the P1R16-containing groups, with the highest junction points and segments lengths in the SPNH assembled by 50% P1R16 (Fig. 5D–F). HUVECs treated with SPNH assembled by RADA16 only, however, remained segregated and spherical with few vessel-like structures.

Fig. 5.

Angiogenic properties of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels. (A) Live/dead staining for cell viability and transwell assay for cell migration of HUVECs, scale bar: 200 μm (up) and 100 μm (down). (B) CCK8 assay for cell proliferation and (C) migration quantitative analysis of HUVECs. (D) Tube formation of HUVECs, scale bar: 100 μm. The quantitative analyses of (E) junction points and (F) segments length for vascularization. Angiogenesis-related gene expression (G) VEGF, (H) bFGF, and (I) HIF-1α and angiogenesis-related protein fluorescence intensity (J) CD31 and (K) VEGF of HUVECs. Immunofluorescence staining of (L) CD31 and (M) VEGF, scale bar: 100 μm *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 0% P1R16; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ####P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 50% P1R16.

The angiogenesis of HUVECs induced by SPNHs containing P1R16 was further evaluated at the gene and protein levels. Angiogenesis-related gene markers, including VEGF, bFGF and HIF-1α, were estimated by qRT‒PCR. The results depicted in Fig. 5G–I showed that P1R16 contained SPNHs significantly promoted their expression. The results of immunofluorescence staining also indicated that SPNHs containing P1R16 promoted the expression of CD31 and VEGF, and the 50% P1R16 SPNH showed the highest angiogenic activity (Fig. 5J–M). Taken together, the above results showed that SPNHs assembled by both P1R16 and RADA16 retained angiogenic activities due to the existence and release of the multi-functional polypeptide PTHrP-1 at both lateral sides of the nanofibers.

3.6. Pro-osteoclastic capacities of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels

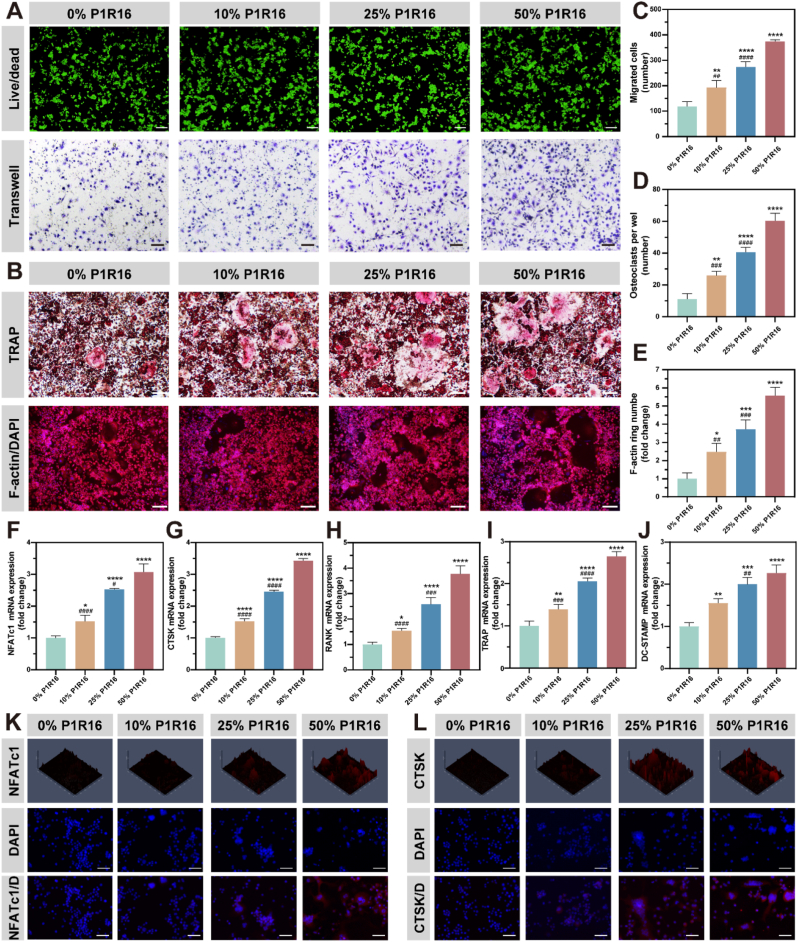

PTH has been reported to promote the expression of RANKL by stem cells and osteoblasts, which could further indirectly promote osteoclast formation [9]. Immunofluorescence staining and intensity analysis of RANKL illustrated that the BMSC expression of RANKL was upregulated after intervention with SPNHs containing 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16, which were 1.92-fold, 3.99-fold, and 6.57-fold higher than that in the 0% SPNH (Fig. 4K and M). Therefore, the osteoclastogenic effect of SPNHs containing P1R16 may be due to its prestimulation of stem cells to secrete pro-osteoclastic RANKL.

An indirect co-culture model of BMSCs and macrophages was further performed to evaluate the capacities of SPNHs containing P1R16 to stimulate osteoclastogenesis. The results of the live/dead assay showed that all SPNHs were biocompatible to macrophages, which maintained more than 95% cell viability after intervention (Figs. 6A and S11). The results of the transwell migration assay illustrated that 10%, 25% and 50% P1R16 SPNHs promoted the infiltration of macrophages when compared with the 0% SPNH, especially for the 50% SPNH (Fig. 6A and C). In addition, TRAP staining and F-actin ring immunofluorescence were carried out to assess osteoclast formation (Figs. 6B and S12). The results revealed that SPNHs containing P1R16 dramatically promoted osteoclast formation when compared with the hydrogel assembled by RADA16 only, and the highest osteoclast properties were found in the SPNH containing 50% P1R16 (Fig. 6D–E).

Fig. 6.

Pro-osteoclastic capacities of supramolecular peptide nanofiber hydrogels. (A) Live/dead staining for cell viability and Transwell assay for cell migration of RAW264.7 cells, scale bar: 200 μm (up) and 100 μm (down). (B) Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining and F-actin ring immunofluorescence staining for osteoclastogenesis of RAW264.7 cells, scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Migration quantitative analysis, (D) TRAP-positive osteoclast quantitative analysis, (E) F-actin ring quantitative analysis and osteoclastogenic-related gene expression (F) NFATc1, (G) CTSK, (H) RANK, (I) TRAP and (J) DC-STAMP of RAW264.7 cells. Immunofluorescence staining of (K) NFATc1 and (L) CTSK, scale bar: 100 μm *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 0% P1R16; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ####P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared to 50% P1R16.