Summary

Abnormal neuronal and synapse growth is a core pathology resulting from deficiency of the Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), but molecular links underlying the excessive synthesis of key synaptic proteins remain incompletely defined. We find that basal brain levels of the growth suppressor let-7 microRNA (miRNA) family are selectively lowered in FMRP-deficient mice and activity-dependent let-7 downregulation is abrogated. Primary let-7 miRNA transcripts are not altered in FMRP-deficiency and posttranscriptional misregulation occurs downstream of MAPK pathway induction and elevation of Lin28a, a let-7 biogenesis inhibitor. Neonatal restoration of brain let-7 miRNAs corrects hallmarks of FMRP-deficiency, including dendritic spine overgrowth and social and cognitive behavioral deficits, in adult mice. Blockade of MAPK hyperactivation normalizes let-7 miRNA levels in both brain and peripheral blood plasma from Fmr1 KO mice. These results implicate dysregulated let-7 miRNA biogenesis in the pathogenesis of FMRP-deficiency, and highlight let-7 miRNA-based strategies for future biomarker and therapeutic development.

Subject areas: Behavioral neuroscience, Molecular neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

MAPK pathway activation contributes to let-7 miRNA dysregulation in FXS mouse model

-

•

Postnatal restoration of let-7 miRNAs rescues dendritic spine and behavioral deficits

-

•

Let-7 miRNA downregulation is observed in brain and plasma of mice deficient in FMRP

-

•

Ancient Lin28/let-7 miRNA developmental regulatory pathway implicated in FXS model

Behavioral neuroscience; Molecular neuroscience

Introduction

The Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), encoded by the FMR1 gene, is an RNA-binding protein that is broadly expressed in the nervous system and affects multiple aspects of RNA biology, including mRNA translation.1,2 Mutations in the FMR1 gene in humans, the amplification of CGG repeat expansions, are accompanied by hypermethylation and transcriptional silencing underlying Fragile X Syndrome (FXS). FXS is the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability and the leading monogenic cause of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Lowered brain levels of FMRP also correlate with a variety of complex neuropsychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia, and autism in individuals without FMR1 mutations,3,4 further underscoring the importance of understanding how deficiency of this RNA binding protein impacts brain development, function, and mRNA translation. Fragile X syndrome (FXS) displays characteristics of dysregulated protein synthesis, developmental overgrowth, and behavioral deficits which can be reproduced in FMRP-deficient mice used for preclinical study of FXS.5 Patients with FXS and mice lacking Fmr1 (Fmr1 KO) display an early overgrowth of neurons, overabundant immature synaptic contacts with aberrant connectivity, altered metabolism, and hyperactive MAPK signaling.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Abnormal synaptic plasticity and dendritic spine growth in the Fmr1 KO mouse has been linked to a range of behavioral and cognitive deficits, including altered hippocampal function in learning and memory.10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 FMRP deficiency produces excessive basal and activity-responsive protein synthesis, and FMRP has been proposed to serve as a break on the translation of mRNAs promoting neuronal and synaptic growth and excitation,17,21,22,23,24 but see.25 While some cellular and behavioral phenotypes resulting from FMRP-deficiency are rescued by generalized inhibition of protein synthesis,8,13,26 how mRNAs undergoing enhanced translation are selectively targeted to generate pro-growth effects in FMRP-deficiency remains enigmatic. Although FMRP-bound mRNAs are found among the transcripts differentially translated in FXS, the majority of mistranslated transcripts are not FMRP-bound targets and an identifiable FMRP-interaction motif is lacking.17,18,21,27 Defects in the control of mRNA translation are also observed in ASD occurring as a result of diverse genetic variants, which provides additional motivation to understand potential shared molecular features with FXS.28,29,30

Short non-coding miRNAs inhibit gene expression by binding to partially complementary sequences, typically in the 3′UTR, of target mRNA transcripts. The lethal-7 (let-7) miRNA was one of the first miRNAs discovered as a regulator of developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans and its functions show high evolutionary conservation across animal species.31,32 Mammals express multiple let-7 isoforms which are grouped as a family by a shared ‘seed sequence’ used for target mRNA recognition. Many pro-growth mRNAs harbor evolutionarily conserved binding sites for let-7 miRNAs, which are often termed ‘growth suppressor’ miRNAs,33,34 and let-7 miRNA biogenesis is tightly controlled to govern development, growth, and tumor-suppressor functions.34,35,36,37 Let-7 miRNAs are highly abundant in differentiated tissues, including the nervous system,38,39,40 where they can target mRNAs involved in neuronal growth and synaptic function, several of which are known to undergo dysregulated protein synthesis in autism and intellectual disability.41,42,43 High let-7 miRNA levels repress pro-growth mRNAs under basal conditions, but allow enhanced translation upon concerted activity-responsive reductions in let-7 miRNAs to support dendrite and dendritic spine growth.33,44 Lin28 RNA-binding proteins promote growth, in part, through a mutually antagonistic relationship with let-7 miRNAs. Lin28 binds a shared sequence motif in let-7 family precursors and inhibits their processing into mature functional let-7 miRNAs and Lin28 transcripts contain binding sites for let-7 family miRNAs.45,46,47,48,49,50,51 Tight control of the Lin28/let-7 pathway mediates timing of biological transitions during critical developmental periods, and also facilitates physiological functions of growth and neuroplasticity.33,44,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59

In this study, our data implicates a potent axis with evolutionarily conserved roles in regulating development, the Lin28/let-7 pathway, in pathology associated with the FXS neurodevelopmental disorder. The let-7 miRNA family, known to repress growth-related transcripts, has reduced levels under basal conditions in the Fmr1 KO mouse brain and fails to undergo normal downregulation in response to environmental stimulation. We find that let-7 family miRNA reductions are mediated post-transcriptionally, and use both in vitro and in vivo approaches to implicate hyperactive MAPK-dependent dysregulation of the Lin28/let-7 pathway by loss of FMRP. Significantly, brain expression of a Lin28-resistant let-7 precursor miRNA rescues both FXS-associated dendritic spine overgrowth and core social and cognitive phenotypes in Fmr1 KO mice. Let-7 miRNAs are also found to be dysregulated in plasma from FMRP-deficient mice, extending these findings to a compartment with relevance for diagnosis and disease management.

Results

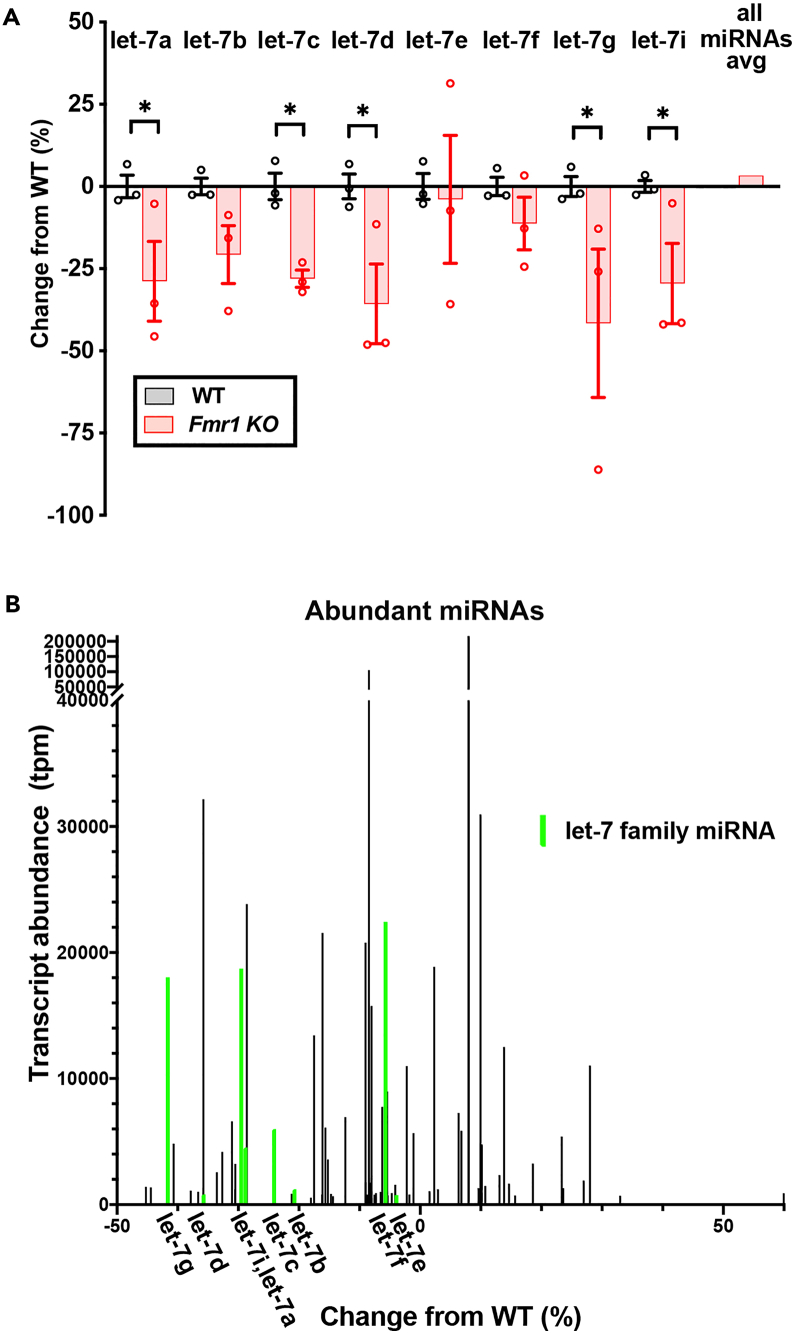

Downregulation of multiple let-7 miRNA family members in Fmr1 KO mouse brain

Altered levels of noncoding RNAs such as miRNA have the potential to mediate dysregulated translation in the Fmr1 KO brain. Prior work from our lab and others have shown that altered cellular MAPK pathway activation, as reported in the context of FMRP-deficiency, can impact miRNA biogenesis and mature miRNA levels.44,60,61,62 Accordingly, we conducted miRNA profiling by multiplexed Illumina small RNA sequencing from cortices of matched male siblings which were either deficient in FMRP (Fmr1 KO, n = 3) or wildtype for FMRP (Fmr1 WT, n = 3) at postnatal day 60 (P60). Consistent with the multiple post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms for miRNAs,63 amplitudes of fold change read counts of miRNAs between Fmr1 KO and Fmr1 WT were modest with relatively few exceeding significance for upregulation (11) or downregulation (11) by DESeq2 analysis (Figure S1A, dashed horizontal line is the p value threshold for a 5% false discovery rate). Let-7d-5p was significantly downregulated in the Fmr1 KO and we noted that other let-7 family members also appeared to share lower average read counts in Fmr1 KO compared to Fmr1 WT brain (Figures S1A and S1B). In expression data normalized for total counts per million (tpm), a subsetted comparison across all detectable let-7 family members revealed significantly lower let-7a, c, d, g, and i levels in Fmr1 KO compared to Fmr1 WT cortex. While decreases in remaining let-7 family members b, e, and f did not reach significance in this comparison, the average values for each let-7 family miRNA member were less in Fmr1 KO compared to Fmr1 WT cortex (Figure 1A); an average across all detectable miRNAs revealed no global change in miRNAs in the Fmr1 KO brain (Figure 1A). These results were consistent with prior work using an oligonucleotide microarray of miRNAs to compare Fmr1 KO to WT P7 mouse brain in which let-7 miRNA downregulation (let-7b,c,f) was apparent in supplemental data.64 Generally, prior miRNA profiling studies in Fragile X mouse models or humans either assayed a restricted number of miRNAs using microarray approaches or were conducted outside the brain with limited numbers of human participants (e.g., in human urine).65 While the relevance is not clear, multiple let-7 family members (let-7a1, a2, a3, let-7f, and let-7g) were reported downregulated with one let-7 member upregulated (let-7b) in urine from a male patient with FXS compared with the matched premutation carrier phenotypically unaffected twin brother.65

Figure 1.

Association of let-7 miRNA dysregulation with FMRP deficiency

(A and B) Expression profiles of let-7 family miRNAs from small RNA sequencing of cortex from matched male Fmr1 KO or Fmr1 WT (n = 3 each) sibling mice at postnatal day 60 (P60). (A) Expression data normalized for total counts per million (tpm) is compared across all reliably detected let-7 family miRNA members (counts ≥0.5 in 3 or more samples) by plotting as change of the miRNA in Fmr1 KO (red) compared to WT (black) levels of the miRNA. For let-7 family members, individual sample values shown as symbols and bars as average. The far right bar is the average change of all reliably detected miRNAs in all samples for Fmr1 KO compared to WT, with Fmr1 WT being zero change. Error bars represent SEM; ∗p < 0.05. (B) Average levels for all abundant miRNAs (≥500 tpm, y axis) plotted against change of Fmr1 KO miRNA levels from WT levels (x axis). Let-7 family member abundance is highlighted in green.

The abundance of a given miRNA, or miRNA family, is a salient factor influencing the extent of target mRNA repression achieved66,67 and, conversely, the expected elevation of target translation if that miRNA or miRNA family is lowered. We observed that multiple let-7 family members, all of which were downregulated relative to the WT condition, were amongst the most highly detected miRNAs in cortex (Figure 1B, plotting only miRNAs with >500 tpm). The propensity for target regulation is increased the greater the change in total levels of a miRNA, or miRNAs sharing the same targeting seed sequence (e.g., the let-7 family), in the Fmr1 KO relative to WT setting. Collectively, the downregulation of let-7 family members represented the greatest differential of miRNA levels (tpms) sharing the same seed sequence in the Fmr1 KO relative to wildtype setting. The other most abundantly detected miRNAs and their differential levels were miR-128-3p (−8.4% from WT), miR-26a-5p (−35.7% from WT), and miR-9-5p (+7.9% from WT). These results heightened the potential for altered levels of let-7 family miRNAs to physiologically impact the Fmr1 KO brain, and motivated further study. Functional genomics and gene ontology analyses have demonstrated conserved roles for let-7 family miRNAs in regulating mRNA targets with importance in developmental timing, growth responses, and metabolism.68,69,70,71 Several let-7 targeted mRNAs that support neuronal growth and plasticity, such as GRIA1 (encoding the GluA1 receptor subunit) and the calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II, CaMKIIα,33 are known to undergo elevated translation in the context of FMRP deficiency.42 In addition, mRNAs encoding proteins previously implicated in FXS pathogenesis, including Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), also contain seed-matched consensus binding sites for let-7 miRNAs.72,73,74 Collectively, these findings and sequencing results prompted us to further investigate dysregulation of let-7 family miRNAs and its impacts in the context of FMRP-deficiency.

Basal downregulation of mature let-7 miRNA levels in Fmr1 KO brain tissue

FMRP is highly expressed in multiple brain regions, including in neurons of the cortex and hippocampus in mice as well as humans.75,76,77,78,79 We next used a sensitive and reproducible qRT-PCR approach to quantitate levels of let-7 miRNA family members, and a control non-let-7 (and non-Lin28-regulated) miRNA, miR-132, all normalized to small RNA U6 snRNA, in homogenates of hippocampi isolated from Fmr1 KO or WT littermate controls (Figures 2A and 2B ). At both an early postnatal (P1-P3, Figure 2A) and an adult time-point (P50-P60, Figure 2B), we detected ∼20–25% reductions on average in levels of assayed canonical mature let-7 miRNA family members in Fmr1 KO hippocampi, compared to WT littermate controls. A similar pattern of reduced let-7 miRNA levels was observed in lysates from the cortex of Fmr1 KO compared to WT mice (Figure 2C). Levels of a control miRNA, miR-132, did not differ in hippocampus or cortex of Fmr1 KO and WT mice (Figures 2A–2C) suggesting a selective deficit rather than general reduction in mature miRNA biogenesis, which was also consistent with our cortical small RNA-seq data. The U6 snRNA used for normalization also did not show a genotype-specific trend. The shared seed region (conservation of nucleotides 2–8 from the 5′ end) of let-7 miRNAs can allow co-regulation of gene targets by multiple family members. Notably, the magnitude of observed reductions in individual mature let-7 miRNA levels were comparable to changes previously detected in response to growth factor stimulation in neurons, which were sufficient to evoke downstream elevations in pro-growth mRNA translation and to mediate physiological growth responses.33,44

Figure 2.

Fmr1 KO mice display chronic defects in basal and activity-dependent control of mature let-7 miRNA production

Error bars represent SEM; ∗∗∗p < 0.001 ∗∗p < 0.01 ∗p < 0.05, n.s. p> 0.1.

(A–D) Two-tailed unpaired t test with Holm-Sidak multiple testing correction. (A) Quantification of miRNA levels in whole hippocampal homogenates isolated from P2 Fmr1 KO and WT littermates. All miRNA levels were normalized to U6 snRNA and plotted relative to WT littermate controls within each experiment, set as 1.0 (data pooled from N = 6–17 mice of both sexes). (B) Quantification of miRNA levels in hippocampal homogenates from WT and Fmr1 KO littermates at P60, normalized to WT condition set as 1.0 (N = 6–12 mice of both sexes). (C) Quantification of miRNA levels in frontal cortex homogenates from Fmr1 KO and WT age-matched non-littermate mice at P60, normalized to WT condition set as 1.0 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; N = 7–16 mice). (D) Quantification of primary miRNA transcripts, pri-let-7a, pri-let7c and pri-let-7g, in whole hippocampal tissue from P60 Fmr1 KO and WT males. All pri-miRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH mRNA and plotted relative to WT condition set as 1.0 (N = 5 males from 3 litters). (E) Quantification of mature miRNA levels in whole hippocampal tissue from sham or environmentally enriched WT and Fmr1 KO mice at P60, normalized to WT sham condition (two-way ANOVA; post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; N = 7–16 males per condition from 7 to 11 independent replicates of non-siblings).

Mature let-7 family miRNAs are produced by stepwise post-transcriptional RNA processing of a primary miRNA precursor (pri-miRNA) transcript. To test whether transcriptional downregulation was responsible for the lowered levels of let-7 family miRNAs observed in Fmr1 KO mice, we conducted qRT-PCR using probes which are selective for the respective pri-miRNA precursors. In contrast to mature let-7a, let-7c, and let-7g, levels of pri-let-7a, pri-let-7c and pri-let-7g primary transcripts were unchanged in lysates from P50-P60 Fmr1 KO hippocampi, compared to WT littermate controls (Figure 2D), indicating that the lowered levels of mature let-7 miRNAs occur post-transcriptionally. Collectively, these results showed a selective decrease in basal mature let-7 family miRNA abundance during brain development that persisted into the adult Fmr1 KO brain, and implied a post-transcriptional mechanism of dysregulation.

Fmr1 KO mice exhibit defects in activity-dependent control of let-7 miRNA levels

In previous work, we and others have reported activity-dependent downregulation of basally-abundant brain let-7 miRNAs both in vitro and in vivo33,44,80 which can selectively enhance translation of mRNAs supporting growth and plasticity and is required for trophic responses including enhanced dendrite arborization and dendritic spine growth in neurons.33,44 Our finding of lowered basal let-7 miRNAs in the context of FMRP-deficiency prompted us to test whether Fmr1 KO might also exhibit a deficit in neuronal activity-evoked let-7 miRNA responses, compared with WT mice. Environmental enrichment (EE) is a well-established in vivo experimental paradigm in which rodents are exposed to a stimulus rich novel environment that facilitates increased cognitive, sensory, and motor stimulation; short-term EE robustly activates excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus and cortex, and significantly elevates levels of plasticity-related genes.81,82 Neuronal activity induced by EE elevates trophic factors, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF), and MAPK activity, which have been associated with induction of the Lin28 RNA binding protein and consequent reduction in mature let-7 family miRNA levels.44,60,83,84,85 Short-term EE (or novel environment exposure) allows the study of primary responses, such as immediate-early genes or post-transcriptional impacts, rather than secondary responses which can be investigated with long-term EE.86,87,88,89 We exposed adult WT and Fmr1 KO mice (male, P60 age-matched) to either their acclimated home cage (sham) or to short-term EE in a cage containing both novel objects and mice for 2 h, followed by immediate isolation of hippocampi and qRT-PCR. Let-7 family miRNAs (let-7a, let-7c, and let-7g) were decreased (Figure 2E) in hippocampal lysates from WT mice exposed to EE compared to sham, whereas a control non-Lin28 targeted miRNA, miR-132, was unchanged. In contrast, neither mature let-7 or miR-132 miRNA levels were altered by the short-term EE compared to sham in lysates from Fmr1 KO hippocampi. The already lowered basal levels of mature let-7 miRNAs in lysates from Fmr1 KO hippocampi under sham conditions did not significantly differ from let-7 levels in WT mice exposed to EE (post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; p > 0.1 for let-7g and p > 0.9 for let-7a and let-7c) (Figure 2E). In the Fmr1 KO context, instead of lowering let-7 miRNA levels, EE now produced no significant effect across all assessed let-7 miRNAs. The activity-dependent increase of a transcription-dependent immediate-early gene, Arc, was robust and comparable in hippocampi from both WT and Fmr1 KO mice following short-term EE (Figure S2A), indicating that both genotypes experienced elevated neuronal activity. These data show that, in addition to chronic reductions in basal let-7 miRNA levels, Fmr1 KO mice are defective in initiating experience-dependent reductions in hippocampal let-7 miRNAs in response to heightened synaptic activation.

FMRP loss induces a let-7 regulator, Lin28a protein

We next considered the mechanism by which FMRP deficiency might mediate lowered brain levels of mature let-7 family miRNAs. Multiple aspects of our data including the co-regulation of multiple let-7 family members located at distinct genomic loci (Figures 1A and 1B; Figure 2) as well as the lack of Fmr1 genotype-related changes in the primary transcripts of let-7 precursor miRNAs (Figure 2D), suggested a post-transcriptional site of action. Work from our laboratory and others identified a MAPK-dependent mechanism for signal-induced stabilization and upregulation of Lin28a in differentiated cells, through Lin28a phosphorylation and binding to phosphorylated TAR RNA binding protein (TRBP), which result in consequent reduced levels of Lin28-targeted let-7 family miRNAs.44,60,61,83 MAPK pathway dysregulation has been reported in FXS, with elevated levels of phospho-extracellular signal-related kinase 1 and 2 (pERK1/2) in brain and peripheral tissues from Fmr1 KO mice and FXS patients.8,90,91,92 Given these observations, we hypothesized that hyperactive MAPK signaling might participate in the reductions in let-7 family miRNAs associated with loss of FMRP by induction of the Lin28a RNA binding protein. Previous work has indicated that early developmental misregulation of Lin28 can result in aberrations of growth and let-7 miRNAs levels which persist in the adult.93 Accordingly, we evaluated both MAPK pathway activation (pErk1/2) and Lin28a protein levels in lysates from embryonic forebrain (E15-E16) of matched Fmr1 KO and WT siblings, a time at which dysregulation might precipitate altered let-7 family miRNAs. Fmr1 KO brain was found to have elevated pERK1/2 in the absence of altered total ERK protein, yielding an elevated pERK1/2/total ERK1/2 ratio compared to WT (Figures 3A and S3A). We next probed the effect of FMRP-deficiency on levels of Lin28a protein in the embryonic forebrain. Anti-Lin28a antibodies can detect multiple species of differing mobility across tissues and developmental stages, possibly contributed to by diverse post-translational modifications.44,61,94,95,96,97,98,99 We knocked-in a myc epitope tag to the endogenous Lin28a locus to unambiguously identify Lin28a protein. Elevated levels of Lin28a protein were observed in the Fmr1 KO condition compared to Fmr1 WT siblings (Figures 3B and S3B) by immunoprecipitation and blotting of embryonic forebrain (E15 - E16) lysates against the myc epitope tag.

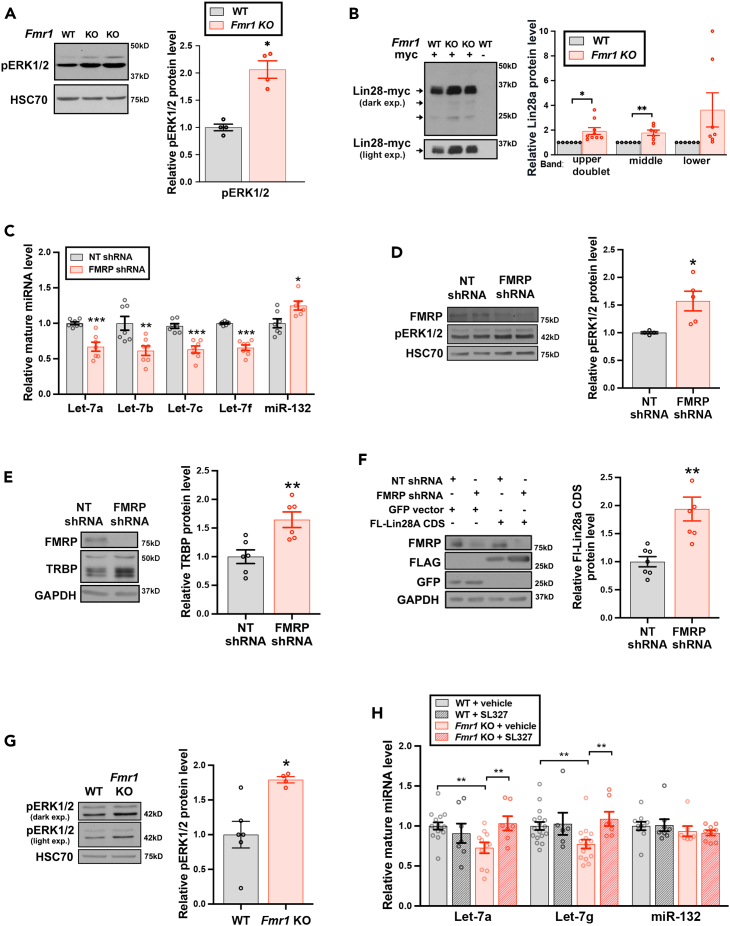

Figure 3.

MAPK hyperactivation underlies aberrant downregulation of let-7 miRNAs in the absence of FMRP

Error bars represent SEM; ∗∗∗p < 0.001 ∗∗p < 0.01 ∗p < 0.05.

(A) Representative immunoblot (left) and densitometric quantification of pERK1/2 protein levels normalized to HSC70 (right) of forebrain lysates from E15-E16 siblings which are either Fmr1 KO or Fmr1 WT. pERK1/2 levels are normalized to HSC70 and the average of WT sibling levels set as 1.0. Total ERK1/2 is not significantly altered by Fmr1 genotype (Figure S3A). (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; N = 4 biological replicates from 3 experiments).

(B) Lysates from forebrain of E15-E16 mice either lacking (myc -) or harboring (myc +) a myc tag at the endogenous Lin28a locus, and either WT or KO for Fmr1 as indicated, were immunopurified with myc-trap nanobody followed by immunoblot with anti-myc antibody. Shown are representative immunoblot (left) with arrows labeling the specific quantified bands and quantification (right) plotted with matched Fmr1 WT siblings set as 1.0. The lysates from mice lacking the myc tag (myc -) at the endogenous Lin28a locus serve as negative control for the IP and blotting. Additional representative immunoblots (Figure S3B). (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; N = 6–9 biological replicates from 4 experiments).

(C) Quantification of normalized miRNA levels from DIV14 hippocampal neurons treated with non-target shRNA control (NT shRNA) or FMRP shRNA for 4 days, plotted relative to NT shRNA condition set as 1.0. (two-tailed unpaired t test with Holm-Sidak multiple testing correction; N = 6–7 biological replicates from 2 experiments).

(D) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantification of pERK1/2 protein levels normalized to HSC70 (right) of lysates from DIV14 hippocampal neurons treated with NT shRNA or FMRP shRNA. (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; N = 4–5 biological replicates from 3 experiments).

(E) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantified endogenous TRBP protein levels (right), normalized to GAPDH, of lysates from hippocampal neurons treated with NT shRNA or FMRP shRNA. (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; N = 6 independent replicates).

(F) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantification of FL-Lin28A protein levels normalized to GAPDH (right) of lysates from DIV14 hippocampal neurons co-expressing either GFP (control) or FL-Lin28A and either NT shRNA or FMRP shRNA. (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; N = 7 independent replicates).

(G) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantification of pERK1/2 protein levels normalized to HSC70 (right) of whole hippocampal homogenates isolated from vehicle-treated (50% DMSO/saline) WT and Fmr1 KO mice at P60. Graph shows pERK1/2 protein levels plotted relative to the effect of WT + vehicle condition set as 1.0. ∗p < 0.05 WT + vehicle vs. Fmr1 KO + vehicle (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; N = 4–6 males).

(H) Quantification of mature miRNA levels in whole hippocampal homogenates from adult WT and Fmr1 KO mice 3h following vehicle or SL327 treatment, normalized to vehicle-treated WT condition. (two-way ANOVA; post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; N = 6–15 males per condition from 9 to 11 independent replicates of non-siblings).

We next established acute lentiviral shRNA-mediated knockdown (KD) of FMRP in primary murine hippocampal neuronal cultures to facilitate probing the molecular mechanisms of Lin28/let-7 dysregulation, to reduce possible obscuring of regulatory mechanisms by developmental compensatory effects, and to allow direct comparisons with matched controls expressing non-target (NT) shRNA (Figure S3C, FMRP KD ≥ 50% for included experiments). In agreement with our findings in Fmr1 KO mice, qRT-PCR showed that acute loss of FMRP recapitulated the decrease in mature let-7 family miRNAs (p < 0.05 two-tailed t test) (Figures 3C and 2A). A control non-Lin28-targeted miRNA, miR-132, was modestly increased by transient FMRP deficiency, while not significantly affected in Fmr1 KO mice. To probe the downstream impact of lowered let-7 miRNA levels associated with FMRP deficiency, we quantitated protein levels of two well-characterized representative let-7-regulated gene targets, CaMKIIα and GluA1, whose mRNA 3′UTRs harbor seed-matched sites for let-7 family members and other Lin28-regulated miRNAs.33 CaMKIIα and GluA1 protein levels showed significant or a trend toward elevation, respectively, under basal conditions in FMRP-deficient neurons, consistent with an expected functional impact of de-repression by the observed reductions in mature let-7 miRNA levels (Figure S3D).

As in the Fmr1 KO mouse brain, acute FMRP KD also activated the MAPK signaling cascade with elevated pERK1/2 protein in immunoblotted lysates (Figure 3D). In line with a post-transcriptional mechanism for Lin28a protein stabilization and induction, we also observed a significant elevation in basal levels of TRBP, which can participate in a stabilizing protein complex with Lin28a,44 following acute KD of FMRP (Figure 3E). To further isolate the mechanism of Lin28a elevation by FMRP loss, we tested the effect of FMRP KD on levels of an expressed FLAG-tagged Lin28a construct containing solely the coding region of Lin28 (FL-Lin28a CDS) and so lacking potential regulation conferred by either the Lin28a promoter or by Lin28a 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Expression of the Lin28a CDS or a control GFP CDS were driven by the neuron-specific synapsin promoter, allowing selective assessment of Lin28a regulation in neurons; consistent with prior observations, exogenously expressed FL-Lin28a migrated near 25 kD.44 shRNA-mediated KD of FMRP, but not expression of a control non-target shRNA (NT shRNA), elevated protein levels of FL-Lin28a without altering levels of the GFP control protein (Figure 3F).

These results showed that the Lin28a protein coding region was sufficient for neuronal upregulation in response to FMRP-deficiency, further supporting post-transcriptional regulation of the Lin28a/let-7 pathway and consistent with previously observed MAPK-dependent regulation at the level of the Lin28a protein.44,60,61,83 Collectively, these in vitro results confirmed consequences of downregulated let-7 miRNA in a setting of acute FMRP-deficiency and provided insights to MAPK-regulated pathways underlying loss of let-7 family miRNAs that prompted us to examine the role of MAPK overactivation in the let-7 miRNA downregulation seen in Fmr1 KO brains.

Hyperactivated MAPK signaling mediates let-7 miRNA downregulation in Fmr1 KO mice

Blockade of ERK1/2 activation, using either selective MAPK pathway inhibitors (e.g., SL327) or FDA-approved drugs such as lovastatin, metformin, and acamprosate, has been shown to relieve excessive protein synthesis and attenuate behavioral deficits in Fmr1 KO mice,13,100,101 Fmr1 KO rats102 and FXS patients.103 MAPK pathway inhibition by SL327 has also normalized behavioral and dendritic spine defects in other genetic models of autism.104 We probed the importance of ERK1/2 hyperactivation in ongoing let-7 miRNA dysregulation in Fmr1 KO mice by assessing the effect of acute inhibition of the MAPK pathway on let-7 miRNA levels in Fmr1 KO mice. P50-P60 WT and Fmr1 KO mice were intraperitoneally (IP) injected with the selective MEK1/2 inhibitor, SL327 (30 mg/kg),8,105 and hippocampi harvested 3h post-injection. SL327 is blood-brain barrier permeant, as well as acting outside the brain92,104,106; single dose IP administration reduced levels of pERK1/2 protein in comparison to vehicle alone (DMSO) by 30 min and for up to 3h following injection (Figure S3E). Cleaved caspase-3, assayed by immunoblot, was not detected in hippocampal or cortical lysates from SL327- or vehicle-treated mice of either genotype, consistent with a lack of apparent brain toxicity with this SL327 administration design (Figure S3F). In agreement with prior reports of increased MAPK activation in Fmr1 KO mice,8,13,91,100,101 basal pERK1/2 levels were elevated in hippocampi from vehicle-treated Fmr1 KO compared to WT mice (Figure 3G). SL327 administration reversed aberrant downregulation of let-7a and let-7g miRNA levels in adult Fmr1 KO mice, without affecting baseline levels of let-7 miRNAs in WT controls (Figure 3H), indicating a reliance on chronic MAPK pathway hyperactivation. SL327 administration did not alter control miR-132 levels in either genotype (Figure 3H). Let-7 family miRNA reductions in vehicle-injected Fmr1 KO relative to vehicle-injected WT mice were comparable to reductions observed in uninjected mice (Figures 3H and 2C). These data indicate that deficiency in let-7 family miRNAs is an ongoing perturbation that occurs downstream of dysregulated MAPK activity, and that it may be acutely reversed in the adult state even though the pathway is affected during development.

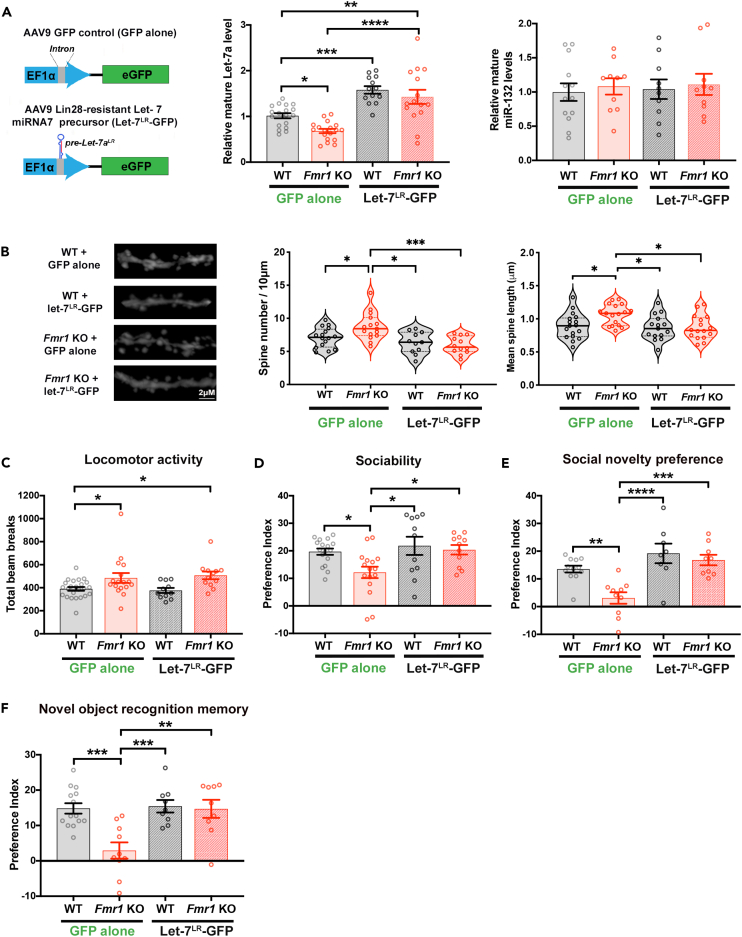

Restoration of let-7 miRNA levels rescues elevated dendritic spine density and autism-related behavioral deficits in Fmr1 KO mice

We next investigated whether the observed magnitude of aberrant let-7 miRNA pathway regulation might causally contribute to the development of FXS-associated phenotypes by examining the impact of normalizing let-7 miRNA levels during development on core neuroanatomical and behavioral abnormalities in adult Fmr1 KO mice. Adeno-associated virus (AAV2/9 serotype) expressing a Lin28-resistant let-7 miRNA precursor along with GFP (Let-7LR-GFP), or control AAV expressing GFP (GFP alone), both driven by the EF1α promoter, were delivered into brains of WT and Fmr1 KO mice by P0 lateral ventricle injection. The Let-7LR-GFP is engineered with a mutation of the Lin28 recognition motif in the pre-miRNA terminal loop which serves to block the binding and consequent inhibition of let-7 precursor processing by Lin28. This mutation allows processing of the let-7 precursor to the mature let-7a species despite elevation of Lin28.33 Mature let-7a harbors the highly conserved and canonical let-7 miRNA seed sequence for target recognition, and so shares an overlapping subset of mRNA targets with other let-7 miRNA family members.107,108 The Let-7LR-GFP was placed under the control of an EF1α promoter to drive ubiquitous expression (Figure 4A, left). At 3 months of age, we detected ∼1.5-fold overexpression of let-7a, but not miR-132, in whole hippocampal lysates from WT and Fmr1 KO mice expressing Let-7LR-GFP compared to GFP alone (Figure 4A, right). Immunostaining analysis at 3–6 months following P0 injection of AAV2/9 expressing either Let-7LR-GFP or GFP exhibited, on average, similar levels and patterns of brain expression. Substantial expression was observed in hippocampus and cortex, with modest midbrain expression and no expression observed in cerebellum (Figure S4A and S4B). Consistent with the reported preferential infection of neurons by AAV2/9 in the neonatal brain,109 we observed a tropism for neuronal expression (Figures S4C and S4D).

Figure 4.

Restoration of let-7 miRNA levels rescues dendritic spine overgrowth and behavioral deficits in Fmr1 KO mice

(A, B, D, E, F) two-way ANOVA; post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test ∗p < 0.05 ∗∗p < 0.01 ∗∗∗p < 0.001 ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). (A) (Left) Diagram of AAV expression constructs for Let-7LR-GFP and GFP alone control (Right) Quantification of mature let-7a or miR-132 miRNA levels in lysates from whole hippocampi isolated from P90 WT and Fmr1 KO mice expressing GFP or Let-7LR-GFP, normalized to WT + GFP condition (N = 10–18 mice per condition).

(B–E) Analysis of 3-month-old Fmr1 KO and WT mice injected i.c.v at P0 with Let-7LR-GFP or GFP alone. (B) Representative confocal projections of secondary dendrites from CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons (left; Scale bar 2μm). Quantification of dendritic spine density (center). Solid line represents median, dashed lines are quartiles. 95% confidence intervals of mean: WTGFP[6.29,7.89]; KOGFP[7.61,9.93]; WTLETLR[5.22,7.40]; KOLETLR [5.09,6.76]. Quantification of average dendritic spine length (right). Solid line represents median, dashed lines are quartiles. 95% confidence intervals of mean: WTGFP[0.79,0.09]; KOGFP[0.98,1.14]; WTLETLR[0.76,0.97]; KOLETLR [0.77,0.96]. (C) Total activity assessed by number of beam breaks during 30 min period in open field test. (two-way ANOVA; post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; N = 11–24 mice). (D) Sociability preference index, calculated as (time with mouse)/(time with mouse + time with object) x 100–50 (N = 11–17 mice). (E) Social novelty preference index, calculated as (time with novel stranger)/(time with novel stranger + time with familiar mouse) x 100–50 (N = 8–12 mice).

(F) Novel object recognition preference index, with 1h intersession delay before introduction of novel object, calculated as (time with novel object)/(time with novel object + time with familiar object) x 100–50 (N = 10–14 mice).

Abnormalities in dendritic spines which receive excitatory inputs, including increased dendritic spine density and immaturity in hippocampal and cortical pyramidal neurons, have been reported as a classic feature in Fmr1 KO mice and in postmortem analyses of FXS patient brain tissue.7,10,14 Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons from Fmr1 KO mice injected with the control GFP virus showed a significantly higher spine density and spine length, a correlate used to read out maturity, on average (measurements taken from the secondary branch of apical dendrites), as compared to WT controls (Figure 4B). Expression of Let-7LR-GFP abrogated differences in both dendritic spine density and spine length between adult Fmr1 KO and WT age and sex-matched mice. In WT animals, introduction of Let-7LR-GFP had no significant effect on basal spine density or length (Figure 4B), a result that is consistent with previous findings44 and may reflect that let-7 miRNAs are already amongst the most abundant miRNAs under basal conditions in the wildtype mammalian brain.40,110,111

To address whether rescue of let-7 miRNA deficiency through Let-7LR-GFP expression might alleviate ASD-relevant behavioral phenotypes in age-matched male and female Fmr1 KO and WT mice,112 we first examined potential effects on general locomotor activity. As previously reported,113,114 we observed that, at 3 months of age and following control AAV-GFP injection, Fmr1 KO mice displayed mildly elevated activity as measured by higher beam-break counts in the open field test compared to WT mice (Figure 4C). Differences between Fmr1 KO and WT mice were not observed in latency to fall on a rotarod assay (Figure S5A). AAV-mediated Let-7LR-GFP expression did not alter performance in either of these assays of motor activity and coordination for either WT or Fmr1 KO mice (Figures 4C and S5A), indicating that the injected viral titer did not detectably alter gross locomotor behaviors.

Social behaviors were assessed using the three-chambered test for sociability90 in which diminished preference for interacting with a social stimulus has been reported for FMRP-deficient mice. As anticipated, the quantified preference for investigating a cage with a stranger mouse relative to an empty cage was diminished for Fmr1 KO mice as compared to WT mice in the AAV-GFP condition, however, AAV-mediated expression of the Let-7LR-GFP rescued preference for interacting with the social stimulus in Fmr1 KO mice to levels comparable to that observed in WT mice expressing either GFP alone or Let-7LR-GFP (Figures 4D and S5B). In WT mice, where basal let-7 levels are already comparatively high, expression of the Let-7LR was not observed to alter sociability. The potential for rescue of let-7 miRNAs in FMRP-deficient mice to more broadly impact core social behaviors was further assessed using a social novelty test in which WT mice recall prior contact with a familiar mouse, and exhibit preference to spend more time with a new stranger mouse. In the AAV-GFP control condition, Fmr1 KO mice displayed a clear defect in this social task relative to WT mice, with strongly impaired preference for interacting with a novel stranger mouse compared to the familiar mouse. Expression of Let-7LR-GFP recovered the preference for a novel stranger mouse in Fmr1 KO mice to levels indistinguishable from WT controls, while Let-7LR-GFP expression did not alter social novelty preference in WT mice compared to expression of GFP alone (Figure 4E). We conclude that restoration of let-7 miRNA levels can normalize the assayed deficits in generalized sociability and social novelty in Fmr1 KO mice, and also that further elevation of abundant let-7 miRNAs in the wildtype context does not appear to impact these behaviors.

Hippocampal-dependent learning and memory deficits are also observed in Fmr1 KO mice,115 and we next assessed the impact of restoring let-7 miRNA levels using a novel object recognition test. Upon re-introduction of an object following a 1h delay, WT mice were able to distinguish the familiar from a preferred novel object with high fidelity, while Fmr1 KO mice exhibited significant defects measured as a lowered novel object preference index compared to WT mice, in the control AAV-GFP condition. In Fmr1 KO mice injected with Let-7LR-GFP, measured preference for the novel object was restored to WT levels (Figure 4F). In contrast, there was no difference in preference for the novel object between WT mice expressing GFP or Let-7LR-GFP (Figure 4F). Importantly, when the novel object was introduced after an abbreviated intersession interval (<5 min), both WT and Fmr1 KO mice displayed a similar degree of preference for the novel object over the familiar one (Figure S5C), consistent with Fmr1 KO mice exhibiting a selective defect in hippocampal-dependent memory formation, as opposed to a generalized aversion or anxiety toward novel stimuli. We conclude that normalizing let-7 miRNA levels in Fmr1 KO mice is capable of restoring appropriate hippocampal-based learning and memory. The behavioral data presented in Figure 4 are pooled results from analysis of age-matched male and female mice of each genotype. When males and females are analyzed separately, the main effect of genotype (Table S1) shows similar trends but fails to reach significance with the exception of novel object recognition in female Fmr1 KO and WT mice. Results from males and females analyzed separately exhibit shared patterns of abrogation of sociability and novel object hippocampal learning differences in Fmr1 KO mice receiving Let-7LR-GFP (Figures S5B and S5D). Taken together, these results show that rescue of let-7 miRNA levels is capable of ameliorating both synaptic and behavioral deficits in Fmr1 KO mice and support a role for a contribution of Lin28/let-7 miRNA pathway dysregulation to dendritic spine overgrowth and behavioral abnormalities in the context of FMRP-deficiency.

Peripheral blood plasma from Fmr1 KO mice recapitulate MAPK-mediated dysregulation of let-7 miRNAs

There is increasing focus in FXS research on the need to identify empirically valid biomarkers for future use in early diagnosis, prediction of risk or severity prior to onset of behavioral features, and for evaluation of therapeutic efficacy. The use of circulating miRNAs as stable, non-invasive blood-based biomarkers is supported for diseases ranging from cancer to ASD.116,117,118,119,120 Plasma (cell-free blood fraction) miRNAs are generally protected from RNases, and have reduced susceptibility to environmental or intracellular metabolic changes that could occur during storage. Our data revealing early onset and ongoing let-7 miRNA dysregulation in the Fmr1 KO mouse prompted us to investigate detection of let-7 dysregulation in plasma and the potential for use in biomarker development. Plasma-detected miRNAs can originate from tissues throughout the body, including brain, and FMRP is also highly expressed in lymphocytes. Accordingly, we used qRT-PCR to assay levels of let-7 family miRNAs in plasma fractions collected from Fmr1 KO and WT age-matched mice (incorporating sibling pairs); plasma-abundant non-let-7 family member RNAs, miRNA (miR-16) and small RNA (5S rRNA), were assayed as controls along with normalization to spike-in C. elegans miR-39. Multiple let-7 family members were tested, as abundance and detection might differ in plasma relative to brain tissue. Reliable detection and consistent reductions in mature let-7 levels in plasma from P2-P6 Fmr1 KO relative to Fmr1 WT mice were quantified across family members, let-7a, b, g, and i, while one let-7 family member, let-7c, did not differ significantly (Figure 5A). Levels of non-Lin28-regulated control RNAs, miR-16 and 5S rRNA were unchanged (Figure 5A). A shared pattern of selective reductions in let-7 family miRNAs a, b, g, and i in plasma from Fmr1 KO relative to WT was also observed in adult P50 - P60 mice (Figure 5B). let-7c changes did not reach significance between Fmr1 KO and WT in this adult plasma cohort, although changes were significant in a separate adult cohort (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Fmr1 KO mice exhibit MAPK-dependent downregulation of let-7 miRNAs in cell-free plasma from peripheral blood

Error bars represent SEM; ∗p < 0.05 ∗∗p < 0.01 ∗∗∗p < 0.001 ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 (A and B) Quantification of miRNA levels in cell-free peripheral blood plasma isolated from (A) P2 – P6 and (B) P60 Fmr1 KO and WT age-matched non-littermate mice. All miRNA levels were normalized to C. elegans miR-39 spike-in control and plotted relative to WT mice for each experiment, set as 1.0. (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; data pooled from 9 to 10 early postnatal and 8 - 14 adult mice of both sexes). Significantly affected miRNAs maintain p < 0.05 significance following multiple testing correction using Holm-Sidak method.

(C) Quantification of mature miRNA levels in cell-free peripheral blood plasma from adult WT and Fmr1 KO mice 3h following vehicle or SL327 treatment, normalized to vehicle-treated WT condition. (two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; N = 6–10 mice per condition).

An additional criterion for a useful biomarker, apart from disease association, is response of the biomarker to an intervention in disease outcome. Inhibition of MAPK pathway hyperactivation can ameliorate aberrant behavioral measures in both patients with FXS and in FMRP-deficient mice,8,13,91,92,103,121 and our data (Figure 3) revealed that MAPK inhibition could reverse chronically lowered let-7 miRNA levels in brain tissue from Fmr1 KO mice. We evaluated a potential response of plasma let-7 miRNAs to perturbation of the disease-relevant MAPK pathway. Acute blockade of MAPK signaling in adult P60 mice by IP-injection of MEK inhibitor SL327 increased plasma let-7 family miRNA levels in Fmr1 KO mice, while not changing let-7 levels in plasma from WT mice (Figure 5C) (Fmr1 KO vehicle vs. SL327 p < 0.05 and WT vehicle vs. SL327 p > 0.1 for all let-7 miRNAs tested; Table S1). In the vehicle control injected condition, lowered let-7 family miRNA levels in plasma from Fmr1 KO compared to Fmr1 WT mice were comparable to results from uninjected mice (Figures 5B and 5C). Plasma levels of miR-16 and 5SrRNA were not significantly different between vehicle-injected adult WT and Fmr1 KO mice, and also did not respond to MAPK inhibition with SL327 in either genotype. These plasma data are in alignment with our mechanistic findings in the hippocampus and lend support to further investigations into the potential for plasma let-7 miRNAs as objective blood-accessible biomarkers to facilitate early diagnosis and evaluation of treatment responsiveness in FXS.

Discussion

We report a role for an evolutionarily conserved developmental growth and timing mechanism, the regulation of growth-suppressor let-7 miRNA biogenesis, in mediating phenotypes of an FXS mouse model. Our results provide evidence of a consequence of FMRP loss that results in upregulation of the Lin28a RNA binding protein with reductions of Lin28-targeted let-7 family miRNAs, downstream of MAPK pathway activation. Critically, phenotypes associated with loss of FMRP can be rescued by restoration of brain let-7 miRNA levels, and deficiency of the let-7 miRNAs can be assayed as a non-invasive biomarker in plasma of mice lacking FMRP. The family of let-7 miRNAs participates in growth-regulatory functions across the animal kingdom and its misregulation has been broadly linked to aberrant phenotypes in development and temporal patterning, cancer, and cellular plasticity. Recent studies implicating the Lin28/let-7 miRNA pathway in pubertal timing and hypothalamic regulation of glucose metabolism122,123,124 have begun to gather support for this developmental role in mammals. FMRP deficiency presents phenotypes in both the Fmr1 KO mouse and in humans with FXS that are consistent with underlying defects in pathways governing growth and development, including hyperactive Ras/MAPK, early overgrowth of synapses and immature dendritic spines with aberrant synaptic pruning,7,10,125,126,127 and increased regional brain volumes or mass at birth.5,128,129,130 Lin28, a post-transcriptional regulator of mature let-7 miRNA production, was first identified in C. elegans as a heterochronic gene for which mutations could either advance or delay maturation and juvenile to adult transitions.

FMRP protein was previously reported to interact with RNA-induced silencing (RISC) components and some miRNAs, including let-7c, though it is not essential for miRNA-mediated degradation.131,132,133,134,135 Several miRNAs were shown to immunoprecipitate with FMRP but, while FMRP deficiency was used as a control for immunoprecipitation specificity, effects of FMRP loss on the corresponding total cellular miRNA levels were not reported.133 Our finding that FMRP loss concertedly lowers growth suppressor let-7 family miRNAs provides a previously unappreciated link of MAPK hyperactivation and Lin28a induction with miRNA misregulation and phenotypes of FMRP-deficiency. Early postnatal let-7 miRNA reductions in Fmr1 KO mice, during a time of rapid synapse proliferation, supports the potential participation of this pathway in developmental pathophysiology. Normal brain let-7 miRNA expression is reported to rise between E12.5 and birth and to progressively increase during postnatal maturation.122 Persistent reductions in let-7 miRNAs, which target mRNAs involved in growth, autophagy, and plasticity, could impact synapse growth and activity-dependent maturation of brain circuits during critical periods. Requirements for Lin28a, and lowered let-7 levels, have been reported in plasticity of neuronal dendrites and synapses in mice.33,44,136 Elevated dendritic spine length and width are also observed in hippocampal neurons subjected to lowering of let-7 family levels using a sponge.133 Consistent with this hypothesis, a mouse model (Mecp2 KO) of Rett syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder showing autism-like behaviors but exhibiting undergrowth readouts of hypo-active MAPK pathway, lowered trophic factor BDNF, sparse synapse growth and reduced brain volumes, has been reported to have elevated brain levels of let-7 family miRNAs.72 Notably, however, forced overexpression of exogenous Lin28a in some cell types is reported to produce an apparent opposite effect of altered dendritic spine morphogenesis with spine loss.137,138

We observed that some FXS-relevant phenotypes of Fmr1 KO mice, including abnormal dendritic spine growth and behavioral deficits were rescued following neonatal introduction of Lin28-resistant let-7 miRNA precursors. Consistent with this timing, correction of abnormal behaviors has also been reported following neonatal re-introduction of FMRP into Fmr1 KO mice.139 Let-7LR expression did not impact assayed behaviors in wildtype mice; we speculate that this could be due to the already high basal levels of let-7 miRNAs in wildtype mice and potentially because the change from steady-state levels is also less in wildtype mice. Selective rescue of ASD-associated social interaction deficits without effects on wildtype mice has been previously observed.140 In contrast to amelioration of social and cognitive phenotypes, we did not observe reversal of a locomotor deficit in Fmr1 KO mice; this could be due to inefficient AAV transduction in the cerebellum, midbrain and amygdala, the apparent lack of Let-7LR-GFP expression in non-neuronal cell populations, or a requirement for rescue preceding the P0 timing of Let-7LR introduction in these studies. The capacity of acute in vivo MAPK pathway inhibition (SL327) to restore brain let-7 miRNA levels in adult Fmr1 KO mice to WT levels, suggests that ongoing, rather than solely developmental, disruption in signaling pathways impacts misregulated let-7 miRNA levels. Function of Lin28, which can inhibit let-7 miRNA biogenesis, in adult post-mitotic neurons has been reported by our lab33,44 and others52,58,124 in growth factor responses and neuroplasticity. It is worth noting, however, that deficiency of Lin28 (upregulating let-7 miRNAs) during the fetal period alone has been reported sufficient to produce lifelong growth and metabolic defects.93

Our in vitro studies in primary neuronal cultures support a post-transcriptional signaling mechanism in disrupting let-7 family miRNA biogenesis with elevated ERK1/2 phosphorylation and Lin28 downstream of acute loss of FMRP. Prior work from our lab and others has shown that hyperactive MAPK can act post-transcriptionally to stabilize Lin28 with resulting lowered let-7 levels.44,60,61,83 An opposing interaction of FMRP and Lin28 was also reported in a Drosophila genetic study which implicated aberrant Lin28-mediated translational control in FMRP deficiency as a cellular basis for stem cell-based tissue overgrowth and altered insulin sensitivity.141 Lin28a has been previously shown to regulate mRNA translation in a cell type-dependent manner. Lin28a is reported to inhibit the translation of a subset of mRNAs destined for the ER in embryonic stem cells142 while, in contrast, Lin28a enhances translation efficiency of distinct mRNAs in cultured myoblasts143 and in neural precursor cells and the embryonic mouse brain.144 In addition to phenotypes resulting from FMRP-deficiency, whole genome sequencing of families with simplex and multiplex ASD has identified intronic mutations in Lin28B, as well as missense mutations in Dicer1 and Ago2, which could potentially influence miRNA production, RISC assembly, and general efficacy of miRNA-mediated translational suppression.145,146 Lin28 plays a conserved essential role in embryonic development and dysregulation at the genomic level, by deletion or loss of function mutations, is embryonic or perinatal lethal and has not been linked to ASD. Interestingly, an SNP in Lin28 (rs3811463; located near the regulatory let-7 binding site) that was previously identified by GWAS studies to confer increased risk for type II diabetes has been linked to gestational diabetes mellitus, which is a significant risk factor for ASD susceptibility in offspring.147

Dysregulation of protein synthesis, including altered levels of autism-associated genes, has been detected in neuronal as well as non-neuronal cells in both Fmr1 KO mice and in patients with FXS.21,148 Likewise, elevations in active pERK1/2 are reported not only in brain tissue,8,92,101,149,150 but also in peripheral blood cells of Fmr1 KO mice and patients with FXS.91,151 MAPK pathway inhibition that ameliorates behavioral phenotypes associated with FXS can also normalize hyperactive ERK1/2 detected in peripheral platelets of FXS patients91,103,121 or peripheral lymphocytes in Fmr1 KO mice.151 These findings are in alignment with our observation of misregulation of the let-7 miRNA family in both brain and plasma of Fmr1 KO mice, and our finding that in vivo MAPK inhibition can normalize let-7 family miRNAs in brain tissue as well as plasma from Fmr1 KO mice. The comparative stability of small RNAs in plasma, relative to potential lability of upstream MAPK cascade phosphorylation during collection and storage, could benefit detection and quantitation and supports further investigation of plasma let-7 family miRNAs as an additional or alternative biomarker in FXS. Analyses of peripheral blood cells from patients with ASD from diverse etiologies have also reported MAPK pathway hyperactivation with elevations in ERK1/2 and phospo-ERK1/2,152,153,154 raising interest in possible broader utility of let-7 miRNA levels as a biomarker in ASD. A miRNA expression profiling study in a small cohort in China noted decreases in several mature let-7 miRNA family members, including let-7a, d, and f, in blood samples from children (mean age 4–5 years) diagnosed with ASD compared to age-matched controls.155 The let-7 miRNAs were not amongst the miRNAs selected for further evaluation in a recent small size clinical report (15 patients, 12 control subjects) surveying miRNA levels in erythrocytes156; conclusions are restricted by the limited data presented and the mixing of premutation, mosaic, and ‘full’ mutation FXS patients along with characteristics of sex, age (25–80 years), and comorbidity for seizures and for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, characteristics which were also not matched with control subjects. Differential miRNA expression patterns in postmortem brain tissue from a range of adults diagnosed with ASD also revealed collective and concerted changes in mature let-7 family miRNAs, as compared to controls157; let-7 miRNAs appeared collectively increased in these ASD patient samples. Such a result might occur as a result of potential compensatory changes or sample inclusion from patients with phenotypically undergrowth forms of autism, while concerted changes are consistent with post-transcriptional regulatory processes given the distinct genomic loci of let-7 family members.5

Aberrant mRNA translation has been prominently linked to both synaptic and behavioral phenotypes in FMRP-deficiency. Given the critical role of FMRP in neurodevelopment and function, the transcripts bound by FMRP have been intensively investigated in an effort to gain insights into FXS pathophysiology. Surprisingly, several unbiased mRNA and proteomic screens have not observed strong overlap between mRNAs mistranslated in FMRP-deficient mice, and the set of mRNAs shown to be bound by the FMRP RNA-binding protein.17,21,22,23 While changes in bulk translation are well-described in FMRP-deficiency, including under basal conditions,21 a molecular basis for the observed selective excessive levels of proteins which promote synaptic growth has remained poorly defined. Our results highlight a previously unappreciated role for dysregulated biogenesis of the let-7 miRNA family in FMRP-deficiency, providing a mechanistic link between an ancient and evolutionarily-conserved pathway governing selective gene expression during growth and development to neuropathology in FXS. Future efforts offer the potential to dissect critical signaling pathways impacted by FMRP loss through altered let-7 family miRNAs.

Limitations of the study

This study reports molecular links between FMRP deficiency and posttranscriptional dysregulation of the let-7 miRNAs, a potent miRNA family with conserved regulation of numerous transcripts supporting growth and metabolism. These studies were carried out in mice deficient in FMRP and it is yet to be determined whether this dysregulation may also be observed in human patients with FXS.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Goat polyclonal Anti-GFP | SICGEN | AB0020-200 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-GFP | Invitrogen | A-11122 |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-NeuN | Millipore | MAB-377, clone A60 |

| Anti-IgG secondary Alexa-labeled | Life Technologies | 488, 568 |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-FMRP | DSHB | 2F5-1 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-FMRP | Cell Signaling | G468 |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-FLAG | Sigma | F3165, Clone M2 RRID:AB_259529; |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-FLAG | Sigma | F7425, RRID:AB_439687 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-phosphoERK1/2 | Cell Signaling | 9101 |

| Rabbit monoclonal Anti-Total ERK1/2 | Cell Signaling | 4695, Clone 137F5 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-TRBP | Abcam or Proteintech | ab72110; 15753-1-AP |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-Arc | Santa Cruz | sc-17839, Clone C-7 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-caspase-3 | Cell Signaling | 9662 |

| Rabbit polyclonal Anti-GluA1 | Millipore | AB1504 |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-CaMKIIα | ThermoFisher | 13-7300, Clone Cba-2 |

| Rabbit monoclonal Anti-myc-tag | Cell Signaling | 2278, Clone 71D10 |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-HSC70 | Santa Cruz | sc-7298, Clone B-6 |

| myc-nanobody coupled beads | Chromotek | yta, Myc-trap |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-GAPDH | Millipore | CB1001, Clone 6C5 |

| Mouse monoclonal Anti-β-tubulin | DSHB | Clone E7 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| pENN.AAV.EF1a.eGFP.WPRE.rBG | Gift from Hames M. Wilson; generated by Penn Vector Core | Addgene plasmid #105547 |

| PlKO.1 | Addgene | Addgene plasmid #10878 |

| FSW | Gift from Guoping Feng | 158 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Hoechst 33342 | ThermoScientfic | 62249 |

| Neurobasal A Medium | Gibco | 10888 |

| B27 supplement | GIbco | 17504-44 |

| SL327 | Sigma Aldrich | S4069 |

| TRI Reagent | Sigma Aldrich | T9424 |

| TrizolITM Reagent | Invitrogen | 15596026 |

| Qiazol lysis reagent | Qiagen | 79306 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| miRNeasy serum/plasma kit | Qiagen | Cat# 217184 |

| miRNeasy micro kit | Qiagen | Cat# 217084 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay let-7a | Life Technologies | Assay ID 000377 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay let-7b | Life Technologies | Assay ID 002619 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay let-7c | Life Technologies | Assay ID 000379 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay let-7f | Life Technologies | Assay ID 000382 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay let-7g | Life Technologies | Assay ID 002282 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay miR-132 | Life Technologies | Assay ID 000457 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay U6 snRNA | Life Technologies | Assay ID 002282 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay sno-234 | Life Technologies | Assay ID 001234 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay sno-412 | Life Technologies | Assay ID 001243 |

| TaqMan miRNA assay mir-16 | Life Technologies | Assay ID 000391 |

| TaqMan snRNA assay 5s rRNA | Life Technologies | Assay ID hs03682751_gH |

| TaqMan pri-miRNA assay let-7a | Life Technologies | Assay ID mm03306744_pri |

| TaqMan pri-miRNA assay let-7c | Life Technologies | Assay ID mm03306764_pri |

| TaqMan pri-miRNA assay let-7g | Life Technologies | Assay ID mm03306155_pri |

| Taqman mRNA assay GAPDH | Life Technologies | Assay ID Mm99999915_g1 |

| bicinchoninic acid protein assay | ThermoScientific | Pierce 23225 |

| Deposited data | ||

| GSE234111 small RNA seq FASTQ | This paper | NCBI Geo repository: GSE234111 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Congenic Fmr1 KO stock #003025 Fmr1tm1Cgr/J | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID:IMSR_JAX:003025 |

| WT mice C57BL/6J stock #000664 | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| Lin28a-Myc/ C57BL/6J | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| CRISPR RNA targeted the sequence 5’-CTCCCA GAAGCCCAGAATTG-3’ |

This paper | N/A |

| DNA template for homology-directed repair was: 5’ – GAGGAAGAGGAAGAGATCCACAGCCCTG CCCTGCTCCCAGAAGCCCAGAATGAGCAGAA ACTCATATCTGAAGAAGACCTGGAACAAAAAC TGATCTCCGAGGAAGATCTTAATTGAGGCCCA GGAGTCAGGGTTATTC TTTGGCTAATGGGGAGTTTAAGGA-3’ |

This paper | N/A |

| primers Ex5-F (GTG ATA GAA TAT GCA GCA TGT G); primer Ex5-R (TCC AGC TTG ATC TTA TGG AAA G) |

This paper | N/A |

| Primers S1 (GTG GTT AGC TAA AGT GAG GAT) and N2 (TGG GCT CTA TGG CTT CTG A) | This paper | N/A |

| spike-in control cel-miR-39-3p | Qiagen | 219610 |

| spike-in control ath-miR159a | Qiagen | 219600; GeneGlobe ID: MSY0000177 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Non-target shRNA | Sigma | SHC002 |

| shRNA targeting FMR1 | Sigma | TRCN0000102621 |

| shRNA targeting FMR1 | Sigma | TRCN0000102622 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | 159 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, RRID: SCR_003070 |

| GraphPad Prism, version 9 | GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA USA | www.graphpad.com |

| miRBase 20.0 | 160 | mirDeep2 |

| Imaris™ | 7.6.5 Bitplane, Inc. | https://Imaris.oxinst.com/ |

| Zen Blue | Zeiss | www.Zeiss.com |

| Bowtie2 | 160 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| DESEq2 | 161 | http://bioconductor.org/packages/3.6/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Mollie Meffert (mkm@jhmi.edu).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact, with a completed Material Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

Code:

This paper does not report original code

Data:

Raw FASTQ files for miRNA-sequencing libraries were deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

Mouse models

All studies were carried out under protocols and care guidelines approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and were in compliance with Association for Assessment of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) guidelines for animal use. Adult mice were group housed (up to 4 sex-matched animals per cage) on a standard 12:12 hour light-dark cycle and provided access to food and water ad libitum. All mice in this study were maintained on the C57BL/6J background.

Method details

Animals

Congenic Fmr1 KO (Fmr1tm1Cgr/J; stock #003025, RRID:IMSR_JAX:003025) and WT mice (stock #000664, RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664) on the C57BL/6J background were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. All experiments were performed in age-matched non-littermates derived from homozygous WT and Fmr1 KO matings, unless otherwise specified. Male Fmr1 KO and WT littermates were generated by crossing heterozygous Fmr1+/- females with hemizygous Fmr1-/y males. Biochemical experiments were performed on male mice unless otherwise stated and behavioral analyses were conducted in both sexes.

Commercial antibodies to Lin28a have detected different protein species across tissues and developmental timepoints, potentially due to alternative splicing or Lin28a post-translational modifications including phosphorylations,61,83 acetylation,96 methylation,97 glycosylation, sumoylation95 and ubiquitination.98 To unambiguously detect Lin28a proteins, we generated mice with the myc epitope knocked-in to the c-terminus of the endogenous Lin28a locus by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in C57BL/6J embryos essentially as described,162,163 and subsequently bred this engineered line to homozygosity in the Fmr1KO mouse line. A synthetic CRISPR RNA targeted the sequence 5’-CTCCCAGAAGCCCAGAATTG-3’ and the DNA template for homology-directed repair was: 5’ – GAGGAAGAGGAAGAGATCCACAGCCCTGCCCTGCTCCCAGAAGCCCAGAATGAGCAGAAACTCATATCTGAAGAAGACCTGGAACAAAAACTGATCTCCGAGGAAGATCTTAATTGAGGCCCAGGAGTCAGGGTTATTCTTTGGCTAATGGGGAGTTTAAGGA-3’. The CRISPR RNA, trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), recombinant Cas9, and homology-directed repair template were injected into embryos by the Transgenic Core Laboratory at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Primers spanning the edited genomic region were used for PCR amplification, TA subcloning (ThermoFisher) and sequencing to identify correctly edited DNA from pups.

Genotyping PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from mouse tails or ears using phenol chloroform extraction. Screening for the presence or absence of the wild-type allele at the Fmr1 locus was performed using primers Ex5-F (GTG ATA GAA TAT GCA GCA TGT G) and Ex5-R (TCC AGC TTG ATC TTA TGG AAA G). Primers S1 (GTG GTT AGC TAA AGT GAG GAT) and N2 (TGG GCT CTA TGG CTT CTG A) were used to screen for the Fmr1 knockout allele. The following thermocycler settings were used: 95°C for 5 mins, 35 cycles composed of 30s at 95°C, 30s at 56°C, and 1 min at 72°C, following by 72°C for 10 min. WT and KO PCR reactions were run separately and products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel [WT: 120bp band; KO: 501bp band].

Dissociated hippocampal culture and stimulation

Neuronal cultures were prepared from the hippocampal regions of P0 WT mice as described.164 Neurons were plated at a density of 50,000cells/cm2 in Neurobasal A medium (GIBCO 10888) supplemented with 2% B27 (GIBCO 17504-44) and 0.5% glutamine. Cultures were washed at 1 day in vitro (DIV1), and media was replaced twice a week thereafter. For lentiviral infection, neuronal cultures at DIV9 were switched into a low volume of reduced serum medium (NBA + 0.5% B27 + 0.5% glutamine) immediately prior to viral infection; incubation with virus was 8 - 12 hours followed by replacement with normal growth media.

Lentiviral and AAV plasmids

Mouse FL-Lin28A and GFP were subcloned into the synapsin promoter driven FSW lentiviral backbone.158 Lin28-resistant let-7a precursor was cloned into AAV9 EF1α-GFP vector (pENN.AAV.EF1a.eGFP.WPRE.rBG, gift from Hames M. Wilson, Addgene plasmid #105547), and AAV virus was generated by Penn Vector Core. Non-target shRNA (Sigma SHC002) or shRNA against FMRP (Sigma TRCN0000102621 or TRCN0000102622) were in lentiviral vector PlKO.1.

Lentivirus preparation and transduction

Lentiviral stocks were prepared as previously described164 or generated by Vigene Biosciences. KD was achieved by lentiviral-mediated delivery of non-target shRNA (Sigma SHC002) or shRNA against FMRP to DIV9 hippocampal cultures at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5-10 for 4-5 days. shRNA sequences are inserted downstream of a U6 promoter in the pLKO.1 lentiviral vector. In some instances, cultures were also co-infected with FL-Lin28A or GFP for biochemical analyses.

Drug treatments

The brain-penetrant MEK inhibitor, SL327 (Sigma Aldrich S4069; IC50 of 0.18 and 0.22μM for MEK1 and MEK2, respectively), was initially solubilized in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored in aliquots at -30 oC. After habituation for 2h, P60 WT and Fmr1 KO males were injected intraperitoneally with either 30 mg/kg SL327 or vehicle (40% DMSO in 0.9% saline). 3h after injection, animals were immediately sacrificed under isoflurane anesthesia and hippocampi were harvested directly into TRI reagent or lysis buffer.

Environmental enrichment

Age-matched WT and Fmr1 KO males were habituated in their respective home cages containing soiled bedding material for 2h, before being randomly assigned to the sham or EE condition. Mice were either left in their standard home cages or placed in an environmentally enriched cage for 2h. During EE, mice were allowed to explore a larger cage containing an assortment of toys, wood chunks, tunnels, igloos, and beads suspended from the cage lid. Mice also received novel social stimulation by being environmentally enriched in groups of 2-3 at a time. Immediately after EE, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed by decapitation. Hippocampi were harvested in ice-cold PBS and homogenized directly into lysis buffer or TRI reagent. All samples were kept at -80oC until further analysis.

RNA analysis

Brain tissues and hippocampal cultures were directly homogenized in TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center) or TrizolITM Reagent (Invitrogen) and total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For qRT-PCR, RNA pellets were washed with 75% (v/v) ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in DNase/RNase-free water. RNA concentration and purity were assayed by measurements of optical density (OD) at 280/260/230nm (Nanodrop). For RNAseq, total RNA was cleaned using the RNA Clean & ConcentratorTM-5 Kit (Zymo Research, R1014) with on-column DNase I treatment according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was resuspended in DNase/RNase-free water and its concentration determined by the Qubit® RNA BR Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Q10211).

RNASeq: Compared and biological replicate samples were handled in parallel following RNA integrity assessment (Bioanalyzer2100,Agilent). Libraries were prepared by ligation of 3’ and 5’ adaptors, reverse transcription, minimal PCR amplification, gel purification and size selection, following by library quality control and sequencing on SE50 Illumina platform. Raw reads were filtered to remove adaptor contamination, reads missing an insert or 3’adaptor, reads containing N >10% or with Qscore of over 50% bases ≥ 5. Clean reads (∼97 % of raw) were mapped (Bowtie)160 to the mouse mm10 reference genome and miRBase 20.0 using modified mirdeep2 software.165 Following total RNA comparisons, sample miRNA expression was statistically analyzed and normalized by transcripts per million (tpm; 106 ∗ readcount/ library miRNA readcount).166,167 Differential expression was assessed using DESeq2 and biological replicates to calculate log2(FoldChange) with padj < 0.05.161

qRT-PCR: For measurements of miRNA abundance, 10ng of isolated RNA were reverse transcribed using the TaqMan miRNA RT kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stem-looped primers specific for each mature miRNA species. The following PCR program was utilized in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines: 1) 4°C for 5min, 16°C for 30 min, 2) 42°C for 30 min, 3) 85°C for 5 min. The product was diluted 1:5 in RNase-free water and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using sensitive and specific TaqMan miRNA assays (Life Technologies) for let-7a (000377), let-7b (002619), let-7c (000379), let-7f (000382), let-7g (002282), and miR-132 (000457). Levels of U6 snRNA (002282), or sno-234 (001234) and sno-412 (001243), were used as internal normalization controls for all mature miRNAs. Pri-let-7 assay (Life Technologies) were pri-let-7a (mm03306744_pri), pri-let-7c (mm03306764_pri), pri-let-7g (mm03306155_pri), with normalization to GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1). qRT-PCR was performed in 20μL reactions on a 96-well optical plate (CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System, BioRad) using the following thermal cycling conditions: 1) 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min 2) 40 cycles of 95°C for 30s and 60°C for 1 min. Relative miRNA abundance was typically quantified using a standard curve method. A 1:5 serial dilution series of an independent standard sample is amplified to generate a standard curve, against which cycle threshold (Ct) values are compared to interpolate initial starting quantities of sample templates. For plasma samples, relative transcript levels were determined using the 2-ΔΔCt method with normalization to spike-in control miRNA (cel-miR-39-3p or ath-miR159a; Qiagen, 1.6 x 108 copies/ul)168; two control non-let-7 family plasma-abundant small RNAs, 5s rRNA and miR-16, were included in each experiment.

Plasma collection

Blood was collected from P2-P6 or P60 mice in EDTA-coated tubes and cell-free plasma fractions (which may include clotting factors) separated by centrifugation (0.6 x g) at 4°C. Samples were processed immediately and evaluated for hemolysis by an individual blind to the sample identity using visual inspection against a white background or by comparing A414 nm of sample to buffer (NanoDropt™); samples with significant hemolysis were not further processed. Plasma fractions were lysed (QIAzol, Qiagen) in the presence of spike-in control RNA (cel-miR-39-3p, or ath-miR159a; Qiagen, 1.6 x 108 copies/ul), and RNA isolated (miRNeasy serum/plasma, Qiagen)

Immunoblotting and immunopurification

For immunoblotting, brain tissues and primary cultures of hippocampal neurons were washed with ice-cold PBS with MgCl2 (0.9mM) and homogenized in lysis buffer (50mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1mM EDTA, 1% Triton X -100, 0.2% SDS) containing fresh Halt protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (ThermoScientific). Following centrifugation (13,000xg, 15 min), protein supernatants were quantitated by bicinchoninic acid (BCA, ThermoScientific) protein assay, separated on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel and electrotransferred to PVDF membrane. For immunopurification (IP), brain tissues were lysed in (25mM Tris-HCl(pH7.5), 150mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.1% SDS, 1% Na deoxycholate), containing freshly added N-ethylmaleimide (NEM, 10 mM) and Halt protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (ThermoScientific). Following centrifugation, lysate supernatants were pre-cleared by 30 min incubation with recombinant protein G-agarose beads. For IP, equal amounts of lysate protein (1 – 2 mg, determined by BCA), were incubated by tumbling at 4°C with myc-trap agarose beads (Chromotek, ) which were pre-equilibrated in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NEM. The anti-myc tag nanobody of myc-trap eliminates conventional heavy and light chain contamination in the IP. IP were washed 4x (wash buffer: 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1% Igepal, 10 mM NEM); washed beads were incubated in SDS-sample buffer at 95°C for 10 min, eluates resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and electrotransferred to PVDF. Input and depleted lysate samples were saved for analysis of IP completion. Myc-trap (capacity ∼ 0.7 ug myc-tag / ul resin slurry) was used at excess in order to deplete the IPd protein.

PVDF membranes were blocked in 5% BSA or 5% nonfat milk, in Tris-buffered saline tween 20 (0.1% TBST) for 2-4h and then incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4oC: FMRP (DSHB 2F5-1 or Cell Signaling G468, 1:1000), FLAG (M2 Sigma F3165, RRID:AB_259529 or Sigma F7425, RRID:AB_439687), pERK1/2 (Cell Signaling 9101, 1:1000), Total ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling 4695, 1:1000), TRBP (Abcam ab72110 or Proteintech 15753-1-AP, 1:1000), GFP (Invitrogen A-11122), Arc (C-7; Santa Cruz sc-17839), caspase-3 (Cell Signaling 9662), GluA1 (Millipore AB1504), CaMKIIα (ThermoFisher Cba-2, 13-7300), myc (Cell Signaling 71D10, 1:1000), HSC70 (Santa Cruz sc-7298, 1:6000), GAPDH (Millipore 6C5), β-tubulin (DSHB E7). All immunoblots were quantified using Image J/Fiji.159 In some cases, representative images were uniformly levels-adjusted for visualization purposes only.

Immunostaining

Mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and whole mouse brains were removed and immediately post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4oC. The brains were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for an additional 48h at 4oC, submerged in OCT (Tissue-Tek, Sakura), and flash-frozen. 100 μm or 12 μm free-floating coronal sections, were collected on Superfrost Plus microscope slides, briefly rinsed with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and subsequently blocked and permeabilized in 10% normal donkey serum containing 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS (10% NDST) for 2h. Sections were stained with the following primary antibodies diluted in 1% NDST overnight at 4oC: GFP (SICGEN AB0020-200) and NeuN (Millipore MAB-377). Alexa-Fluor (488, 568; Life Technologies) labeled secondary antibodies were used to visualize staining. Sections were mounted and coverslipped.

P0 intracerebroventricular injection

Injection was performed as previously described.169 Neonatal animals were collected within 6 hours after birth and injected with 1x1011 AAV9 viral particles expressing EF1α-GFP alone or EF1α-Let-7LR-GFP. Virus was diluted in sterile PBS (137mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 10mM Na2HPO4, 1.8mM KH2PO4, 0.5mM MgCl2, 1mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) to appropriate dilution and visualized by diluting into 1mg/mL Fastgreen dye to a final concentration of 0.05%.

Imaging and analysis of dendritic spines