Abstract

Objective

Survival outcomes of robotic radical hysterectomy (RRH) remain controversial. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to evaluate survival outcomes between RRH) and laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (LRH) in patients with early-stage cervical cancer.

Methods

Studies comparing between RRH and LRH published up to November 2022 were systemically searched in the PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases. Manual searches of related articles and relevant bibliographies of the published studies were also performed. Two researchers independently extracted data. Studies with information on recurrence and death after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy were also included. The extracted data were analyzed using the Stata MP software package version 17.0.

Results

Twenty eligible clinical trials were included in the meta-analysis. When all studies were pooled, the odds ratios of RRH for recurrence and death were 1.19 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.91–1.55; p=0.613; I2=0.0%) and 0.96 (95% CI=0.65–1.42; p=0.558; I2=0.0%), respectively. In a subgroup analysis, the quality of study methodology, study size, country where the study was conducted, and publication year were not associated with survival outcomes between RRH and LRH.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that the survival outcomes are comparable between RRH and LRH.

Trial Registration

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews Identifier: CRD42023387916

Keywords: Uterine Cervical Neoplasm, Laparoscopy, Robotic Surgical Procedures, Hysterectomy, Survival Analysis

Synopsis

Previous studies were underpowered to detect clinically meaningful difference in survival outcomes between robotic radical hysterectomy (RRH) and laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (LRH). We assessed the survival outcome between RRH and LRH in patients with early-stage cervical cancer. Survival outcomes are comparable between RRH and LRH.

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in women worldwide [1]. Radical hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection are the standard procedures for patients with early-stage cervical cancer. A previous trial [2] demonstrated that minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (MIRH), including robotic radical hysterectomy (RRH) and laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (LRH), had lower rates of disease-free and overall survival than abdominal radical hysterectomy (ARH). Recently, MIRH is no longer the mainstream method because of its poor survival outcomes after the LACC trial. Chiva et al. reported that patients who underwent MIRH without a uterine manipulator had a similar disease-free survival rate to the ARH group [3]. Although a prospective study is warranted, MIRH without a uterine manipulator is currently considered an acceptable method. Currently, the RACC and ROCC trials, which compare the survival outcomes between RRH and ARH, are underway. Once their results are available, the status of minimally invasive surgery will likely be reevaluated. If there is no difference in survival outcomes between MIRH and ARH, MIRH is beneficial as it offers several advantages over ARH [4].

Laparoscopic surgery has limitations in the straight instrument, amplified tremor, and uncomfortable position of surgeons. The da Vinci robotic surgery system has gained the favor of surgeons due to its 3-dimensional definition vision, multi-degree-of-freedom rotatable wrist device, tremor filtration, and better ergonomics [5]. Previous studies [6,7,8,9,10] comparing RRH and LRH have reported no difference in survival outcomes between RRH and LRH. However, most of the studies [6,8,9,10] were retrospective, and the number of study subjects was relatively small to evaluate survival outcomes. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the survival outcomes between RRH and LRH in uterine cervical cancer through a meta-analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Literature search

The protocol was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42023387916). We conducted a comprehensive literature search using the PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases for studies published from 2008 to November 2022 comparing RRH and LRH for the treatment of early-stage uterine cervical cancer. The following Medical Subject Heading terms and free-text terms were used for the search: “robotic radical hysterectomy,” “robotic surgery,” and “laparoscopic radical hysterectomy” in combination with “survival outcome,” “overall survival,” “disease-free survival,” “recurrence,” and “cervical cancer or carcinoma.” Additionally, we manually searched the references of the eligible studies to identify additional related studies.

2. Selection criteria

We included comparative studies on RRH and LRH in patients with early-stage cervical cancer. Studies assessing ARH and laparoscopic radical trachelectomy were excluded. Case series, editorials, letters to the editor, and conference abstracts were also excluded. Studies without available data on recurrence and death were excluded. We also excluded studies with fewer than 10 patients per arm. Non-English-language studies were excluded from the analysis.

3. Data extraction

Two researchers independently evaluated the eligibility of all the studies retrieved from the database based on the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements between authors were resolved through discussion. Among all articles found in the databases, we excluded duplicate articles and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria. We extracted the following data from the studies: first author, year of publication, published journal, year registered and enrolled, country where surgery was performed, study design, clinical stage (International Federation of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2008 staging system), study population, number of resected lymph nodes, overall follow-up period, and number of recurrences and deaths. When the follow-up period was different, the number of recurrences and deaths was corrected under the assumption that the hazard ratio was constant.

4. Main and subgroup analyses

We investigated the association between RRH and survival outcomes and compared the association between LRH and survival outcomes in the main meta-analysis. We also performed subgroup analyses for publication year, study size (small vs. large), quality of study methodology (high quality vs. low quality), and country to search for causes of heterogeneity. In this meta-analysis, matched retrospective and prospective cohort studies were classified as high quality, whereas retrospective studies were classified as low quality. When ≥40 patients were included in both the RRH and LRH groups, it was considered a large-scale study. The published articles were divided into the first and second halves of the time series. The countries were categorized as Asia, the USA, and Europe.

5. Statistical analyses

Data for dichotomous variables were analyzed using odds ratios (ORs); ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for recurrence and death after RRH and LRH. Forest plots were used to evaluate overall effects. We also performed a subgroup analysis to assess the effects of covariates, such as publication year, study size, quality of study methodology, and country where surgery was performed. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Higgins I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test [11]. The I2 values ranged from 0% to 100%; we considered an I2 value of >50% or a Q-test p-value of <0.1 as indicative of significant heterogeneity. We planned to estimate a pooled OR with a 95% CI using a fixed-effects model [12] in the absence of significant heterogeneity and a random-effects model [13] in the presence of significant heterogeneity. However, we only used the fixed-effects model because there was no heterogeneity in any of the analyses. Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to assess for publication bias. All meta-analyses were performed using the Stata MP software package version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

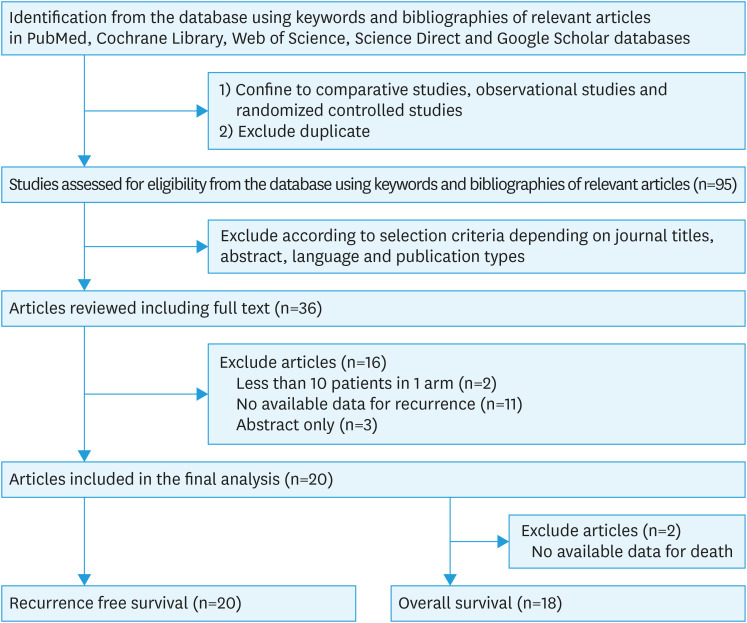

After identifying potentially relevant studies from electronic databases and deleting duplicate articles, 95 articles were screened by the reviewers according to their titles, abstracts, and article types. Of these articles, 59 did not meet the selection criteria and were excluded. After reviewing the full texts of the remaining 36 articles, we found 20 relevant studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], published between 2008 and 2019, suitable for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Eleven out of the 16 studies excluded from the final review had insufficient data regarding survival outcomes. Other articles were excluded because they reported only abstraction (n=3), and 2 articles were excluded because the number of patients in one arm was less than 10. Two of the 20 relevant studies were excluded from the analysis of overall survival owing to unavailable data (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram to identify relevant studies for the meta-analysis.

Table 1 presents the main characteristics of the 20 studies included in the final analysis. Their study design types were retrospective (n=12) [17,18,19,20,22,24,25,26,27,30,31,33], matched retrospective (n=2) [21,29], and prospective (n=6) [14,15,16,23,28,32]. The locations of these studies were Asia (n=8) [20,21,22,25,27,28,31,33], Europe (n=8) [17,18,19,23,26,29,30,32], and the USA (n=4) [14,15,16,24]. The countries with the largest representation in this meta-analysis were Italy (n=5) [18,23,26,29,30], South Korea (n=4) [21,22,27,31] and the USA (n=4) [14,15,16,24]. The enrollment period (year) of participants across the studies ranged from 2003 to 2017. We identified 1,050 patients who underwent RRH and 2,071 who underwent LRH. Out of the total 3,121 patients, 259 (8.3%) had recurrences (98 of the 1,050 patients underwent RRH, and 161 of the 2,071 patients underwent LRH), and 111 (3.6%) died of disease (38 of the 1,050 patients underwent RRH and 73 of the 2,071 patients underwent LRH). There were no statistically significant differences in the number of resected lymph nodes between RRH and LRH in all studies, except for 2 [16,24].

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the current meta-analysis (n=20).

| Authors | Published year | Journal | Year enrolled | Country | Study design | Stage | Population | Follow-up (mo) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRH | LRH | RRH* | LRH* | |||||||

| Magrina et al. [14] | 2008 | Gynecol Oncol | 2003–2006 | USA | Prospective | IA2–IB2 | 27 | 31 | 31.1 | 31.1 |

| Nezhat et al. [15] | 2008 | JSLS | 2000–2008 | USA | Prospective | IA2–IIA | 13 | 30 | 12 | 29 |

| Estape et al. [16] | 2009 | Gynecol Oncol | 2006–2008 | USA | Prospective | IA2–IB2 | 32 | 17 | 7.8 | 31.4 |

| Lambaudie et al. [17] | 2010 | Eur J Surg Oncol | 2007–Unknown | France | Retrospective | IA2–IVA | 22 | 16 | 11.6 | 19.5 |

| Tinelli et al. [18] | 2011 | Ann Surg Oncol | 2003–2010 | Italy | Retrospective | IA1–IIA | 23 | 76 | 24.5 | 46.5 |

| Gortchev et al. [19] | 2012 | Gynecol Surg | 2006–2010 | Bulgaria | Retrospective | IB1 | 73 | 46 | 10.5 | 51.1 |

| Chen et al. [20] | 2014 | Int J Gynecol Cancer | Unknown | Taiwan | Retrospective | IA–IIB | 24 | 32 | 13.9 | 34.6 |

| Kim et al. [21] | 2014 | Int J Gynecol Cancer | 2008–2013 | ROK | Matched | IB1–IIA1 | 23 | 69 | UK | UK |

| Yim et al. [22] | 2014 | Yonsei Med J | 2009–2013 | ROK | Retrospective | IA1–IIA2 | 60 | 42 | 25 | 19.5 |

| Corrado et al. [23] | 2016 | Int J Gynecol Cancer | 2010–2013 | Italy | Prospective | IB2–IIB | 41 | 41 | 30 | 60.1 |

| Mendivil et al. [24] | 2016 | Surg Oncol | 2009–2013 | USA | Retrospective | IA2–IIB | 58 | 49 | 39 | 39 |

| Nie et al. [25] | 2017 | Int J Gynecol Cancer | 2009–2016 | China | Retrospective | IA2–IIA2 | 100 | 833 | UK | UK |

| Pellegrino et al. [26] | 2017 | Acta Biomed | 2010–2016 | Italy | Retrospective | IA2–IIA1 | 34 | 18 | 59 | 30 |

| Heo et al. [27] | 2018 | Obstet Gynecol Sci | 2009–2013 | ROK | Retrospective | IA1–IIB | 19 | 22 | UK | UK |

| Luo et al. [28] | 2018 | BMC Womens Health | 2014–2015 | China | Prospective | IA–IIB | 30 | 30 | UK | UK |

| Gallotta et al. [29] | 2018 | Eur J Surg Oncol | 2010–2016 | Italy | Matched | IA2–IIB | 70 | 140 | 24 | 36 |

| Corrado et al. [30] | 2018 | Int J Gynecol Cancer | 2001–2016 | Italy | Retrospective | IB1 | 88 | 152 | 46.6 | 41.7 |

| Chong et al. [31] | 2018 | Int J Gynecol Cancer | 2008–2013 | ROK | Retrospective | IB1–IIA2 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 72 |

| Ind et al. [32] | 2019 | Int J Med Robot | 2010–2017 | Unknown | Prospective | IB1 | 32 | 25 | UK | UK |

| Chen et al. [33] | 2019 | World J Clin Cases | 2014 | China | Retrospective | IA1–IIB | 216 | 342 | 29 | 30 |

LRH, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy; ROK, republic of Korea; RRH, robotic radical hysterectomy.

*Median or mean.

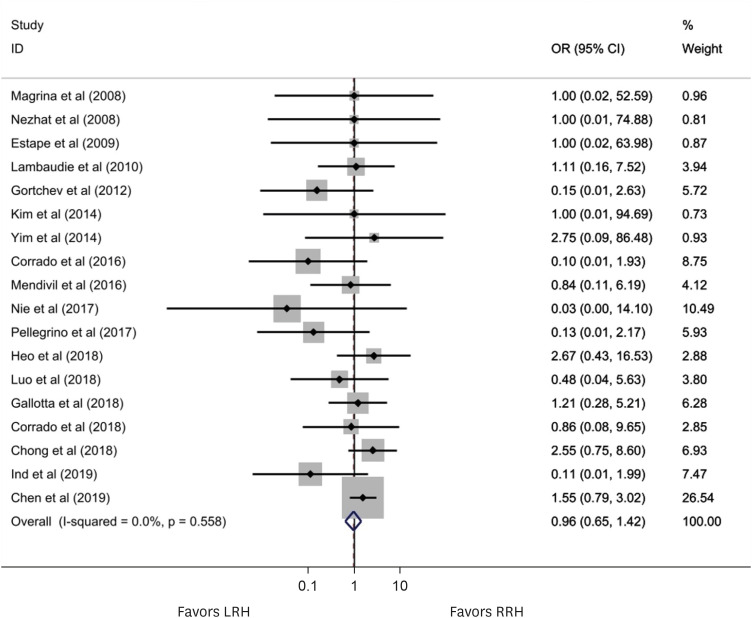

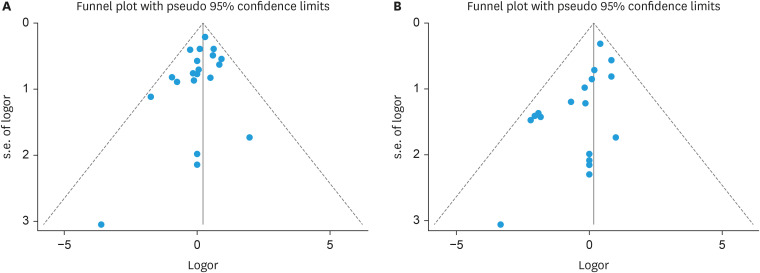

Figs. 2 and 3 present the effect of RRH compared to LRH on the risk of recurrence and death in this meta-analysis of 20 and 18 studies, respectively. In a fixed-effects meta-analysis of 20 studies investigating recurrence, there was no statistically significant difference between RRH and LRH (OR=1.19; 95% CI=0.91–1.55; p=0.204). In a fixed-effects meta-analysis of 18 studies investigating death, there was no statistically significant difference between RRH and LRH (OR=0.96; 95% CI=0.65–1.42; p=0.204). There was no heterogeneity among studies of recurrences (I2=0.0%; p=0.827) or among studies of deaths (I2=0.0%; p=0.558). Funnel plot analysis showed a lack of publication bias in the incidence of recurrence and death (Fig. 4). Egger’s regression plot also demonstrated no publication bias. A cumulative meta-analysis of recurrence after RRH compared with LRH was performed. As shown in the cumulative meta-analysis, the summary estimate for recurrence tended to decrease over time (Fig. S1). Table 2 presents a summary of the subgroup analysis that assessed the potential effects of publication year, study size, quality of study methodology, and study location. There were no significant differences between RRH and LRH in the subgroup analysis categories.

Fig. 2. The forest plot shows the incidence of recurrences of RRH compared to LRH in a fixed-effect model of 20 studies. No significant between-study heterogeneity was detected (I2=0.0%; p=0.613) (OR=1.19; 95% CI=0.91–1.55; p=0.204).

CI, confidence interval; LRH, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy; OR, odd ratio; RRH, robotic radical hysterectomy.

Fig. 3. The forest plot shows the incidence of deaths of RRH compared to LRH in a fixed-effect model of 18 studies. No significant between-study heterogeneity was detected (I2=0.0%; p=0.558) (OR=0.96; 95% CI=0.64–1.42; p=0.827).

CI, confidence interval; LRH, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy; OR, odd ratio; RRH, robotic radical hysterectomy.

Fig. 4. Funnel plots of the incidence of recurrences (A) and deaths (B) of robotic radical hysterectomy compared to laparoscopic radical hysterectomy.

Table 2. Association between type of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy and recurrence in subgroup analysis (n=20).

| Category | No. of studies | Summary OR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity, I2 (%) | p | Model used | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 20 | 1.19 (0.91–1.55) | 0.0 | 0.613 | Fixed effect | |

| Published year | ||||||

| Before 2015 | 9 | 1.30 (0.70–2.39) | 0.0 | 0.874 | Fixed effect | |

| After 2015 | 11 | 1.16 (0.87–1.56) | 23.1 | 0.224 | Fixed effect | |

| Study size | ||||||

| Large (both arm >40) | 8 | 1.11 (0.81–1.52) | 0.0 | 0.529 | Fixed effect | |

| Small (at least 1 arm <40) | 12 | 1.40 (0.86–2.29) | 0.0 | 0.486 | Fixed effect | |

| Quality of study methodology | ||||||

| High quality | 9 | 1.33 (0.81–2.19) | 0.0 | 0.479 | Fixed effect | |

| Low quality | 11 | 1.14 (0.83–1.55) | 0.0 | 0.503 | Fixed effect | |

| Country | ||||||

| Asia | 8 | 1.23 (0.86–1.76) | 0.0 | 0.544 | Fixed effect | |

| USA | 4 | 1.46 (0.52–4.10) | 0.0 | 0.726 | Fixed effect | |

| Europe | 8 | 1.09 (0.71–1.67) | 22.9 | 0.247 | Fixed effect | |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odd ratio.

DISCUSSION

Radical hysterectomy is the standard treatment for early-stage cervical cancer. The LACC trial [2] and subsequent meta-analyses [34,35] demonstrated that the survival outcomes of MIRH were not as good as those of ARH. Subsequently, the number of ARH increased relative to MIRH [36]. The LACC trial has been criticized for various reasons, such as inadequate preoperative imaging and evaluation, the utilization of transcervical uterine manipulators, and insufficient tumor containment, which resulted in peritoneal contamination. Several studies [3,37] have shown no difference in survival between the 2 groups without the use of a cervical manipulator. Moreover, a prior study demonstrated no significant difference in survival rates between ARH and MIRH even when using a uterine manipulator in small cervical cancer <2 cm [34]. A vaginal cuff closure technique can be used to prevent tumor exposure and manipulation during MIRH [38]. Although current evidence favors ARH and the frequency of performing MIRH is relatively lower than before, MIRH remains a valid strategy in a limited range without compromising oncological outcomes. Several meta-analyses [34,35] have analyzed the survival outcomes of MRIH and ARH, but few have compared RRH and LRH.

RRH is superior to LRH in terms of estimated blood loss, but there is no difference in survival outcomes and perioperative complications between LRH and RRH. Radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer has a survival rate of more than 90%. As most of the studies were retrospective and the follow-up period was short, the number of patients who experienced recurrence may have been underestimated. Therefore, we attempted to confirm this finding through meta-analysis. We attempted a meta-analysis using the hazard ratio to compare the survival outcomes of RRH and LRH, but there were no studies presenting hazard ratios. Only 9 [18,19,21,23,24,26,27,30,31] of the 20 studies included in the meta-analysis showed survival curves. Therefore, we evaluated the OR for the risk of recurrence and death after RRH compared with that after LRH.

Guo et al. [39] performed a network meta-analysis to evaluate survival and surgical outcomes according to different surgical approaches for uterine cervical cancer. There were no significant differences in the recurrence or overall mortality between the RRH and LRH groups. However, they did not focus on survival outcomes. Zhang et al. [40] evaluated the efficacy of RRH for cervical cancer compared with LRH through a meta-analysis. They reported that there were no significant differences in recurrences between RRH and LRH using pooled data from 7 studies (OR=0.96; 95% CI=0.50–1.87; p=0.91). Meta-analysis for overall survival was not performed owing to limited data.

Our meta-analysis has some limitations. First, this meta-analysis failed to provide the highest level of evidence because of the retrospective nature of the included studies. Thus, selection bias and missing data may have reduced the quality of this study. Second, survival outcomes were calculated using ORs because most studies did not suggest hazard ratios or Kaplan-Meier curves. When the overall follow-up differed, the number of recurrences and deaths was revised under the assumption that the hazard ratio was the same. However, the overall follow-up period of each group was not specified in 30% of studies included in this meta-analysis. Third, the number of patients who underwent RRH in most studies was small, and the follow-up period was short because RRH was introduced later than LRH. The learning curve of early RRH might have influenced the results. Cumulative meta-analysis showed that the summary estimate of RRH compared to LRH for recurrence tended to decrease over time. A better survival outcome might be obtained in the RRH group if performed by surgeons who have mastered robotic surgery. Fourth, several techniques, such as routine use of a uterine manipulator [2,3] or an effect of the insufflation gas that might affect survival outcomes in MIRH, were not considered. Fifth, most patients had early-stage uterine cervical cancer from IA to IIA. However, among the 20 studies, 8 included stage IIB disease. Patients with stage IIB disease have been treated with radical hysterectomy in several countries. In the high-risk group with lymph node metastasis, parametrial involvement, positive resection margins, large tumors, and postoperative adjuvant therapies could have affected the results. Sixth, the mass size of cervical cancer, which could affect survival outcomes, was not considered. Finally, excluding languages other than English may have affected our outcomes.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest meta-analysis to focus on survival outcomes between RRH and LRH. The meta-analysis included 20 studies. Publication bias was minimal in this study. Although most of the included studies were retrospective and nonrandomized, this study included more than 3,121 patients and a comprehensive review of the available literature. The current meta-analysis demonstrated that oncological efficacy was comparable between RRH and LRH. Well-designed, prospective, randomized controlled trials are required to verify our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Conceptualization: H.J.H.

- Data curation: H.J.H.

- Formal analysis: H.J.H.

- Investigation: H.J.H., K.B.

- Methodology: H.J.H.

- Writing - original draft: H.J.H.

- Writing - review & editing: H.J.H., K.B.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Cumulative meta-analysis of the incidence of recurrences of robotic radical hysterectomy compared to laparoscopic radical hysterectomy.

References

- 1.Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Saraiya M, Ferlay J, et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e191–e203. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30482-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, Lopez A, Vieira M, Ribeiro R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895–1904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiva L, Zanagnolo V, Querleu D, Martin-Calvo N, Arévalo-Serrano J, Căpîlna ME, et al. SUCCOR study: an international European cohort observational study comparing minimally invasive surgery versus open abdominal radical hysterectomy in patients with stage IB1 cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020;30:1269–1277. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Summitt RL, Jr, Stovall TG, Steege JF, Lipscomb GH. A multicenter randomized comparison of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy in abdominal hysterectomy candidates. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herron DM, Marohn M SAGES-MIRA Robotic Surgery Consensus Group. A consensus document on robotic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:313–325. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soliman PT, Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Dos Reis R, Schmeler KM, Nick AM, et al. Radical hysterectomy: a comparison of surgical approaches after adoption of robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:333–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Neugut AI, Burke WM, Lu YS, Lewin SN, et al. Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive and abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong GO, Lee YH, Hong DG, Cho YL, Park IS, Lee YS. Robot versus laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a comparison of the intraoperative and perioperative results of a single surgeon’s initial experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1145–1149. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31829a5db0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vizza E, Corrado G, Mancini E, Vici P, Sergi D, Baiocco E, et al. Laparoscopic versus robotic radical hysterectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: a case control study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyama K, Kanno K, Kojima R, Shirane A, Yanai S, Ota Y, et al. Short-term outcomes of robotic-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a single-center study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:405–411. doi: 10.1111/jog.13858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolf B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann Hum Genet. 1955;19:251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1955.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magrina JF, Kho RM, Weaver AL, Montero RP, Magtibay PM. Robotic radical hysterectomy: comparison with laparoscopy and laparotomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nezhat FR, Datta MS, Liu C, Chuang L, Zakashansky K. Robotic radical hysterectomy versus total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for treatment of early cervical cancer. JSLS. 2008;12:227–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estape R, Lambrou N, Diaz R, Estape E, Dunkin N, Rivera A. A case matched analysis of robotic radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy compared with laparoscopy and laparotomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:357–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambaudie E, Narducci F, Bannier M, Jauffret C, Pouget N, Leblanc E, et al. Role of robot-assisted laparoscopy in adjuvant surgery for locally advanced cervical cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:409–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tinelli R, Malzoni M, Cosentino F, Perone C, Fusco A, Cicinelli E, et al. Robotics versus laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy in patients with early cervical cancer: a multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2622–2628. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gortchev G, Tomov S, Tantchev L, Velkova A, Radionova Z. Robot-assisted radical hysterectomy—perioperative and survival outcomes in patients with cervical cancer compared to laparoscopic and open radical surgery. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CH, Chiu LH, Chang CW, Yen YK, Huang YH, Liu WM. Comparing robotic surgery with conventional laparoscopy and laparotomy for cervical cancer management. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1105–1111. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim TH, Choi CH, Choi JK, Yoon A, Lee YY, Kim TJ, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic radical hysterectomy in cervical cancer patients: a matched-case comparative study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1466–1473. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yim GW, Kim SW, Nam EJ, Kim S, Kim HJ, Kim YT. Surgical outcomes of robotic radical hysterectomy using three robotic arms versus conventional multiport laparoscopy in patients with cervical cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55:1222–1230. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.5.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corrado G, Cutillo G, Saltari M, Mancini E, Sindico S, Vici P, et al. Surgical and oncological outcome of robotic surgery compared with laparoscopic and abdominal surgery in the management of locally advanced cervical cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:539–546. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendivil AA, Rettenmaier MA, Abaid LN, Brown JV, 3rd, Micha JP, Lopez KL, et al. Survival rate comparisons amongst cervical cancer patients treated with an open, robotic-assisted or laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: a five year experience. Surg Oncol. 2016;25:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nie JC, Yan AQ, Liu XS. Robotic-assisted radical hysterectomy results in better surgical outcomes compared with the traditional laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for the treatment of cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:1990–1999. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellegrino A, Damiani GR, Loverro M, Pirovano C, Fachechi G, Corso S, et al. Comparison of robotic and laparoscopic radical type-B and C hysterectomy for cervical cancer: long term-outcomes. Acta Biomed. 2017;88:289–296. doi: 10.23750/abm.v%vi%i.6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heo YJ, Kim S, Min KJ, Lee S, Hong JH, Lee JK, et al. The comparison of surgical outcomes and learning curves of radical hysterectomy by laparoscopy and robotic system for cervical cancer: an experience of a single surgeon. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61:468–476. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.4.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo C, Liu M, Li X. Efficacy and safety outcomes of robotic radical hysterectomy in Chinese older women with cervical cancer compared with laparoscopic radical hysterectomy. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:61. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0544-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallotta V, Conte C, Federico A, Vizzielli G, Gueli Alletti S, Tortorella L, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic radical hysterectomy in early cervical cancer: a case matched control study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corrado G, Vizza E, Legge F, Pedone Anchora L, Sperduti I, Fagotti A, et al. Comparison of different surgical approaches for stage IB1 cervical cancer patients: a multi-institution study and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28:1020–1028. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chong GO, Lee YH, Lee HJ, Hong DG, Lee YS. Comparison of the long-term oncological outcomes between the initial learning period of robotic and the experienced period of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28:226–232. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ind TE, Marshall C, Kasius J, Butler J, Barton D, Nobbenhuis M. Introducing robotic radical hysterectomy for stage 1bi cervical cancer-a prospective evaluation of clinical and economic outcomes in a single UK institution. Int J Med Robot. 2019;15:e1970. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, Liu LP, Wen N, Qiao X, Meng YG. Comparative analysis of robotic vs laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3185–3193. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang JH, Kim BW. Comparison of survival outcomes after laparoscopic radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy in patients with cervical cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:971–981.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nitecki R, Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Krause KJ, Tergas AI, Wright JD, et al. Survival after minimally invasive vs open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1019–1027. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang JH, Kim BW, Jeong H, Kim H. Comparison of urologic complications between laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and abdominal radical hysterectomy: a nationwide study from the National Health Insurance. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.04.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng S, Li Z, Chen L, Yang X, Su P, Wang Y, et al. Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer by pulling the round ligament without a uterine manipulator. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;264:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lago V, Tiermes M, Padilla-Iserte P, Matute L, Gurrea M, Domingo S. Protective maneuver to avoid tumor spillage during laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: vaginal cuff closure. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:174–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo X, Tian S, Wang H, Zhang J, Cheng Y, Yao Y. Outcomes associated with different surgical approaches to radical hysterectomy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023;160:28–37. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang SS, Ding T, Cui ZH, Lv Y, Jiang RA. Efficacy of robotic radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer compared with that of open and laparoscopic surgery: a separate meta-analysis of high-quality studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e14171. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cumulative meta-analysis of the incidence of recurrences of robotic radical hysterectomy compared to laparoscopic radical hysterectomy.