Introduction

Professionals, including physicians, dentists, and lawyers, have earned a special place in society. They are characterized by a high level of education, devotion to selflessness and service, responsibility for self-governance, and adherence to a code of professional conduct.(1) Dentists are governed by the ADA Principles of Ethics and Code of Conduct which incorporates 5 fundamental principles to form its foundation: patient autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, justice and veracity.(2) Within the Code, nonmaleficence focuses on obligations of the provider: credentials, expertise, supervision of auxiliary staff, and fitness to perform, while beneficence speaks to a dentist’s obligation to individual patients, the public, and the profession. In a world of increasing misinformation and conflicting narratives often presented via social media without sound evidence, advancement of scientifically directed care is paramount. Continuing to study, apply and advance scientific knowledge is of critical importance. While explicitly stated in the AMA Code of Professional Conduct for physicians(3), it is only implied as part of the ADA code for dentists. Together principles of nonmaleficence and beneficence call for dental professionals to advance dental knowledge and skills for the greater good, improving the well-being of patients and the community. Dental schools and academic health centers have an obligation to not only conduct and lead oral health research but also ignite the passion of inquiry within their communities, contributing to the new workforce of research-minded clinicians.

Importance of Research

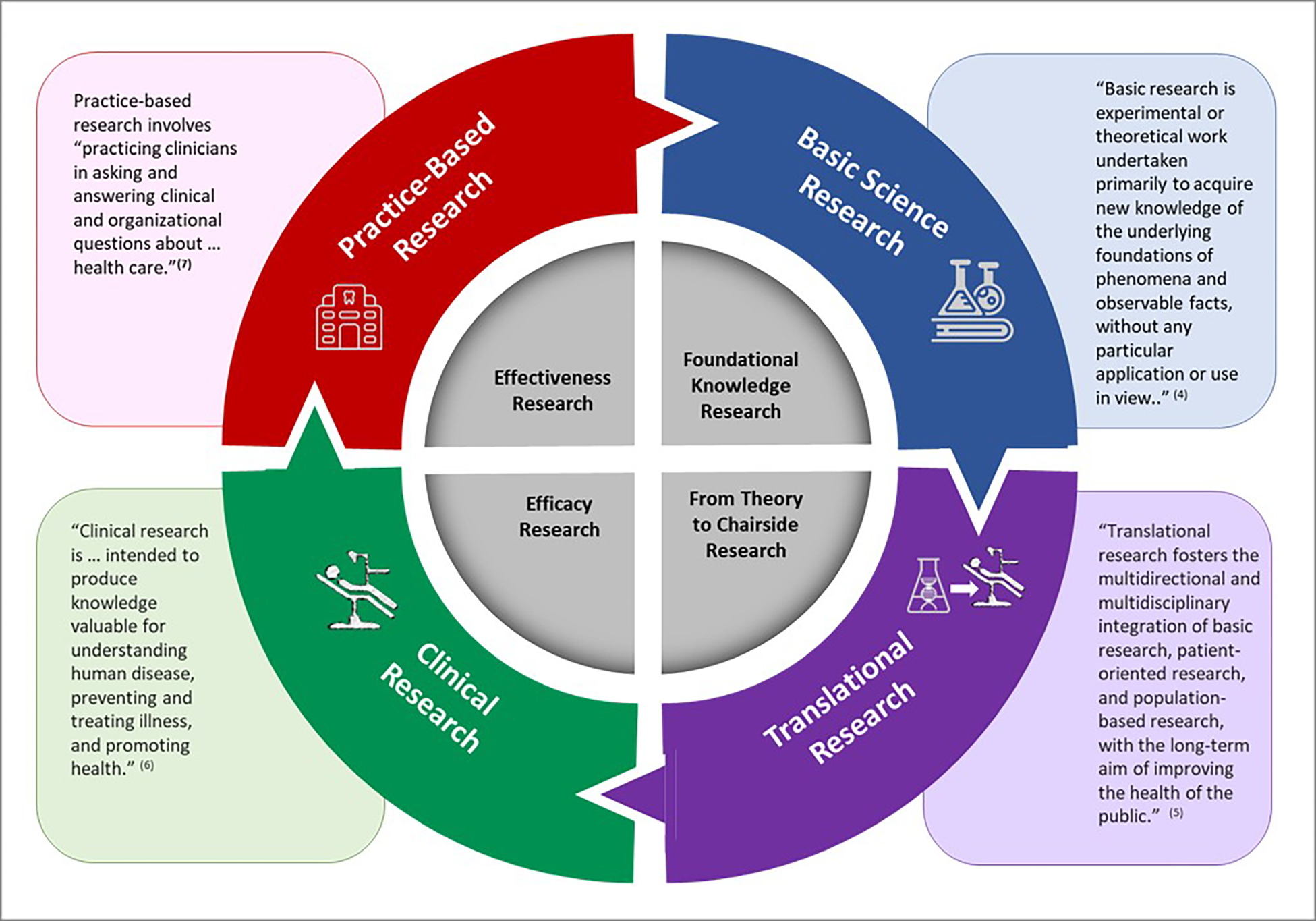

Today advances in biomedical sciences are expanding exponentially with science and knowledge evolving from basic science to practice-based research. Figure 1 illustrates the different types of research required to advance the health and well-being of our patients.(4–7) First, a strong foundation in biology, materials, information, social science is required, without which new interventions and therapies could not be developed.(8) Second, translational research is required to evaluate the clinical potential, bringing new knowledge from research labs into the clinical environment.(9,10) Third, clinical research is essential to determine the efficacy or impact of new therapies and interventions through rigorously conducted clinical trials. Lastly, practice-based research is necessary to determine pragmatically if the promise of these new therapies and interventions hold up in the real-world practice environment and in the case of dental products, unsupervised use.(11) Hence, practice-based clinicians have significant opportunities to contribute with each clinician able to decide upon their desired level of involvement. In addition, knowledge gained in the research process can lead to new ideas that will initiate scientific improvements in dental care.

Figure 1: Advancing Oral Health through Research.

Oral health research is a continuum consisting of basic, translational, clinical, and practice-based research. While there is overlap between the different classifications, all are required and contribute to advances in oral health.

Why Practice Based Research

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality defines practice-based research as research involving practicing clinicians in asking and answering clinical and organizational questions about health care.(7) Networks, such as the NIH/NIDCR supported National Dental Practice Based Research Network (PBRN), have been established to increase collaborations for conducting pragmatic research within the dental setting.(12,13,14) PBRNs have the potential to engage clinicians in research activities as part of daily practice thereby fostering an evidence-based culture. (15) To ensure patient safety and privacy, research undertaken by PBRNs undergo humans subjects protection review by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) contracted through the PBRN. Informed consents which PBRN investigators are required to obtain from their patients are also reviewed by the IRB to ensure benefits and risks are properly disclosed. Today, PBRNs are also viewed as places of learning, where clinicians, patients and academic researchers collaborate in the search for answers that lead to improved care.(16−19) Compensation is often available to both office and patient participants for time and effort.

Practice-based research is conducted in community-based and private practice environments, as well as academic health centers. Patients are recruited to participate in studies by physicians or dentists while engaged in everyday clinical practice. These physicians and dentists are “citizen-practitioner-scientists” who are passionate about providing the best evidence-based care to their patients while helping to advance knowledge and research in the field. Community-based and private practice-based environments are ideal for conducting pragmatic effectiveness studies, studies which determine outcomes of new treatments or procedures in “real-world” clinical settings.(18) Practice-based studies are therefore able to determine whether the benefits identified in strictly controlled clinical trials translate into today’s clinical practice. Research conducted in PBRNs benefits from the diversity of the providers, geography, and patients at these sites (20) with outcomes impacting practice.(21) As dental schools are major providers of treatment, particularly to underserved members of the population, dental schools are an ideal setting to conduct practice-based research, with an additional benefit of exposing students to the excitement of conducting practice-based research.

A Bright Future

It is exciting to see the interest the next generation of dental professionals have in participating in practice-based research. This enthusiasm is reflected in survey data collected at a dental school to assess student interest in learning about practice-based research. In a recent study conducted in a US dental school, 168 predoctoral and 52 postgraduate dental students/residents responded. Results include 72.0% of predoctoral students and 71.2% of postgraduate students/residents indicating interest in engaging in practice-based research while in school, 83.9% of predoctoral students and 51.9% of postgraduate students/residents in earning a micro-credential in practice-based research and 54.2% of predoctoral and 44.2% of postgraduate students/residents in earning a master’s degree in translational or clinical research. This level of interest suggest that students will readily embrace opportunities to enhance research knowledge and skills, which they can carry throughout their careers. As the vast majority of dental graduates engage in community, corporate or private practice after graduation, preparing graduates for practice-based research needs to become a priority. The recently announced Practice-Based Research Integrating Multidisciplinary Experiences in Dental Schools (PRIMED) can make this priority a reality. (22) For dental professionals already in practice, continuing education programs and study clubs can be created to enhance research competence. (23)

Conclusion:

As oral health professionals, we have an ethical obligation to further dental research. By participating in practice-based research, whether through a PBRN or a university sponsored practice-based study, dentists can fulfill their responsibility to advance dental knowledge dentistry and improve the health and well-being of patients and the community.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under awards X01DE030407, U19DE028717 and U01DE028727. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Biography

Dr. Feldman is dean and distinguished professor at the Rutgers University School of Dental Medicine, Newark, NJ; professor at the Rutgers University School of Public Health, Piscataway, NJ; and adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Fredericks-Younger is associate dean for graduate programs and assistant professor at the Rutgers University School of Dental Medicine, Newark, NJ.

Dr. Daniel Fine is chair and professor at the Rutgers University School of Dental Medicine, Newark, NJ

Dr. Kenneth Markowitz is director of faculty development and curriculum innovation and associate professor at the Rutgers University School of Dental Medicine, Newark, NJ.

Dr. Emily Sabato is associate dean for academic and assistant professor at the Rutgers University School of Dental Medicine, Newark, NJ.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

None of the authors have any financial, economic, or professional interests that may influence positions presented in the commentary.

Human Subjects:

The referenced survey was approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board DHHS Federal Wide Assurance Identifier FWA00003913 approved Study ID Pro2022001687. Informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gardner H, Shulman LS. The professions in America Today. Daedalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Vol 134, No 3. Summer 2005. Pg. 13–18. ISBN 0–87724-050–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Dental Association. Principles of Ethics and Professional Conduct. https://www.ada.org/-media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/about/ada_code_of_ethics.pdf?rev=f9a73c582a1d4f4b9c780799bd58db33&hash=30930C28F79FEAD862A87018D89B748A. Accessed on January 4, 2023.

- 3.American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/principles-of-medical-ethics.pdf. Accessed on January 6, 2023.

- 4.OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=192. Accessed on January 23, 2023.

- 5.Rubio DM, Schoenbaum EE, Lee LS, Schteingart DE, Marantz PR, Anderson KE, Platt LD, Baez A, Esposito K. Defining translational research: implications for training. Acad Med. 2010. Mar;85(3):470–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ccd618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Library of Medicine National Center for Biotechnology Information. Appendix V Definition of Clinical Research and Components of the Enterprise.

- 7.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. About PBRNs. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/research-transform-primary-care/pbrn/index.html. Accessed on January 4, 2023.

- 8.NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Translation Science Spectrum. https://ncats.nih.gov/translation/spectrum. Accessed on January 6, 2023.

- 9.Zarbin M What Constitutes Translational Research? Implications for the Scope of Translational Vision Science and Technology. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020. Jul 14;9(8):22. doi: 10.1167/tvst.9.8.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008. Jan 9;299(2):211–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartung DM, Guise JM, Fagnan LJ, Davis MM, Stange KC. Role of practice-based research networks in comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res. 2012. Jan;1(1):45–55. doi: 10.2217/cer.11.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, Fellows JL, Gordan VV, Makhija SK, Meyerowitz C, Oates TW, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Foy PJ; National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent. 2013. Nov;41(11):1051–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.04.002. Epub 2013 Apr 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mungia R, Funkhouser E, Buchberg Trejo MK, Cohen R, Reyes SC, Cochran DL, Makhija SK, Meyerowitz C, Rindal BD, Gordan VV, Fellows JL, McCargar JD, McMahon PA, Gilbert GH; National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Practitioner Participation in National Dental Practice-based Research Network (PBRN) Studies: 12-Year Results. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018. Nov-Dec;31(6):844–856. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.06.180019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Watershed Of Practice-Based Research: Lessons And Opportunities From The COVID Pandemic”, Health Affairs Forefront, January 20, 2022. DOI: 10.1377/forefront.20220118.451069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curro FA, Grill AC, Thompson VP, Craig RG, Vena D, Keenan AV, Naftolin F. Advantages of the dental practice-based research network initiative and its role in dental education. J Dent Educ. 2011. Aug;75(8):1053–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Primary Care Practice Based Research Networks An AHRQ Initiative. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/primary/pbrn/index.html. Accessed on January 4, 2023.

- 17.Davis MM, Gunn R, Kenzie E, Dickinson C, Conway C, Chau A, Michaels L, Brantley S, Check DK, Elder N. Integration of Improvement and Implementation Science in Practice-Based Research Networks: a Longitudinal, Comparative Case Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021. Jun;36(6):1503–1513. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06610-1. Epub 2021 Apr 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mjör IA. Controlled clinical trials and practice-based research in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2008. Jul;87(7):605. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curro FA, Vena D, Naftolin F, Terracio L, Thompson VP. The PBRN initiative: transforming new technologies to improve patient care. J Dent Res. 2012. Jul;91(7 Suppl):12S–20S. doi: 10.1177/0022034512447948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB et al. Practices participating in a dental PBRN have substantial and advantageous diversity even though as a group they have much in common with dentists at large. BMC Oral Health 9, 26 (2009). 10.1186/1472-6831-9-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert GH, Fellows JL, Allareddy V, Cochran DL, Cunha-Cruz J, Gordan VV, McBurnie MA, Meyerowitz C, Mungia R, Rindal DB; National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Structure, function, and productivity from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Clin Transl Sci. 2022. Jun 22;6(1):e87. doi: 10.1017/cts.2022.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Practice-Based Research Integrating Multidisciplinary Experiences in Dental Schools (PRIMED). https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-DE-23-012.html. Accessed on February 17, 2023.

- 23.DeRouen TA, Hujoel P, Leroux B, Mancl L, Sherman J, Hilton T, Berg J, Ferracane J; Northwest Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based Dentistry. Preparing practicing dentists to engage in practice-based research. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008. Mar;139(3):339–45. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]