Abstract

Brief ischemia prior to a sustained period of ischemia reduces myocardial infarct size, a phenomenon known as preconditioning. A cardiac ventricular myocyte model has been developed to investigate the role and signaling mechanism of adenosine receptor subtypes in cardiac preconditioning. A 5-min exposure of cardiac myocytes to simulated ischemia, termed preconditioning ischemia, prior to a subsequent 90-min period of ischemia protected them against injury incurred during the 90-min ischemia. Preconditioning ischemia preserved ATP content, reduced percentage of cells killed, and decreased release of creatine kinase into the medium. Activation of the adenosine A1 receptor with CCPA or the A3 receptor with IB-MECA can replace preconditioning ischemia and mimic the protective effect of preconditioning ischemia. Blockade of the A1 receptor with its selective antagonist DPCPX or of the A3 receptor with the A3 selective antagonist MRS1191 during the preconditioning ischemia resulted in only a partial attenuation of the subsequent protection. Incubation with both DPCPX and MRS1191 or with the nonselective antagonist 8-SPT during the preconditioning ischemia completely abolished the protective effect of preconditioning ischemia. The KATP channel opener pinacidil caused a large activation of the KATP channel current and was able to precondition the myocyte. The KATP channel antagonist glibenclamide blocked the cardioprotective effect of preconditioning ischemia when it was included during myocyte exposure to the preconditioning ischemia, indicating that KATP channel is a requisite effector in mediating preconditioning. A receptor-mediated stimulation of phospholipase C or phospholipase D, with consequent activation of protein kinase C and KATP channel, appears to be the signaling mechanism linking adenosine A1 and A3 receptors to the induction of preconditioning. A model of how ischemic preconditioning is triggered and mediated is proposed. Evidence is accumulating to support its validity.

Keywords: myocardium, adenosine, receptor, purinergic, ischemia

INTRODUCTION

Preconditioning has been demonstrated in isolated perfused hearts of a number of mammalian species, including dog, guinea pig, pig, rabbit, and rat [Murray et al., 1986; Deutsch et al., 1990; Li et al., 1990; Cribier et al., 1992; Downey, 1992; Ely and Berne, 1992; Auchampach et al., 1992; Miura et al., 1992; Schulz et al., 1994; Yao and Gross, 1994]. Evidence for such protective preconditioning also exists in humans [Deutsch et al., 1990; Cribier et al., 1992; Tomai et al., 1994]. Adenosine is released in large amounts during ischemia and plays a key role in triggering and mediating preconditioning and other cardioprotective effects in most animal species, including humans [Murray et al., 1986; Olafsson et al., 1987; Babbitt et al., 1989; Wyatt et al., 1989; Deutsch et al., 1990; Li et al., 1990; Auchampach et al., 1992; Cribier et al., 1992; Downey, 1992; Ely and Berne, 1992; Miura et al., 1992; Schulz et al., 1994; Tomai et al., 1994; Yao and Gross, 1994]. Studies [Armstrong and Ganote, 1994; Ikonomidis et al., 1994; Webster et al., 1995] of adult human and rabbit ventricular myocytes and cultured neonatal rat and embryonic chick cardiac myocytes provided important insights by indicating that the cardioprotective mechanism of preconditioning is exerted, at least in part, at the level of and by the cardiac myocytes in the intact heart. Cardiac ventricular myocytes cultured from chick embryos 14 days in ovo have been developed into a useful myocyte model to study the mechanism of ischemic preconditioning [Liang, 1996, 1997; Strickler et al., 1996; Stambaugh et al., 1997; Dougherty et al., 1998; Liang and Jacobson, 1998]. These myocytes retain many of the properties of the intact heart and have served as a useful model for a variety of experimental paradigms [DeHaan, 1967; Galper and Smith, 1978; Barry and Smith, 1982; Marsh et al., 1985; Liang et al., 1986; Stimers et al., 1991; Xu et al., 1992]. Previous studies have demonstrated that activation of adenosine receptors in these cultured heart cells produces physiologic effects similar to those elicited by adenosine in the adult mammalian heart [Liang, 1989, 1992; Liang and Haltiwanger, 1995; Liang and Morley, 1996]. The cultured ventricular myocytes contain predominantly (>90%) myocytes [Marsh et al., 1985; Strickler et al., 1996] and are largely devoid of neuronal, blood, or vascular cells. Thus, the confounding influence of changes in blood flow is avoided [DeHaan, 1967; Galper and Smith, 1978; Barry and Smith, 1982; Marsh et al., 1985; Liang et al., 1986; Liang, 1989, 1992; Stimers et al., 1991; Xu et al., 1992; Liang and Haltiwanger, 1995; Liang and Morley, 1996]. The myocyte model exhibits characteristics similar to those obtained in the intact heart model of ischemic preconditioning [Murray et al., 1986; Downey, 1992; Gross, 1992; Liang, 1996, 1997; Strickler et al., 1996; Stambaugh et al., 1997; Dougherty et al., 1998; Liang and Jacobson, 1998].

Using this myocyte model, prior studies demonstrated the existence of both adenosine A1 and A3 receptors on the cardiac ventricular myocyte and indicated that activation of both receptors is required to mediate the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning. The present study provides further evidence for these conclusions and provides additional data on the cellular electrophysiologic and biochemical mechanism underlying the receptor-mediated preconditioning effect. An overall working model on how ischemic preconditioning is triggered and mediated is proposed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and Preconditioning of Cultured Ventricular Cells

Cardiac ventricular myocytes were cultured from chick embryos 14 days in ovo, according to a previously described procedure [Barry and Smith, 1982; Liang and Haltiwanger, 1995]. Myocytes were cultivated in a humidified 5% CO2–95% air mixture at 37°C for 3 days, at which time cells grew to confluence and exhibited rhythmic spontaneous contraction. All experiments were performed on day 3 in culture. For preconditioning studies, the medium was changed to a HEPES-buffered medium containing (in mM) 139 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 0.9 CaCl2, 5 HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid), and 2% fetal bovine serum, pH 7.4, 37°C before exposing cells to the various conditions at 37°C. Control cells were maintained in the HEPES-buffered media under room air. Ischemia was simulated by placing the cells in a hypoxic incubator (NuAire) where O2 was replaced by N2; percent O2 was monitored by both an oxygen Fyrite Gas Analyzer (Bacharach) and an oxygen analyzer (Model OX630, Engineered Systems & Designs). Preconditioning was induced by exposing the cells to 5 min of simulated ischemia, termed preconditioning ischemia, prior to a second 90-min ischemia. In studying the ability of adenosine A1 or A3 receptor agonist or KATP channel opener to mimic the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning, cells were exposed to the agent for 5 min and incubated in fresh drug-free media for 10 min before being exposed to 90 min of simulated ischemia. Cells not subjected to preconditioning were exposed to 90 min of ischemia only (nonpreconditioned cells). The extracellular pH was similarly maintained at 7.4 by HEPES in both preconditioned and nonpreconditioned cells. Determination of basal level of cell injury was made after parallel incubation of control cells under normal O2. For all cells, determination of cell injury was made at the end of the 90-min ischemic period.

Quantitative Determination of the Extent of Myocyte Injury

The extent of hypoxia-induced injury to the ventricular cell was quantitatively determined by the percentages of cells killed, by the amount of creatine kinase (CK) released into the media, and by the myocyte content of ATP, according to previously described methods [Liang, 1996, 1997; Strickler et al., 1996; Stambaugh et al., 1997; Dougherty et al., 1998; Liang and Jacobson, 1998]. To quantitate the percentage of cells killed, cells were detached following exposure to a trypsin-EDTA Hanks’ balanced salt solution for 10 min for detachment. Viable cells were sedimented by centrifugation (300g for 10 min) and resuspended in culture media for counting in a hemocytometer. Only live cells sedimented and the cells counted represented those that survived [Mestril et al., 1994]. None of the sedimented cells subsequently counted included trypan blue. Control experiments carried out in prior studies [Strickler et al., 1996] indicated that trypsin treatment, reexposure to Ca2+-containing media or 300 g sedimentation did not cause any significant damage to the control, normoxia-exposed cells. In support of the notion that 90-min hypoxia caused significant cell injury and loss of membrane integrity, there was also marked release of LDH and proteins from the cells incubated under prolonged hypoxia [Liang, 1996]. Thus, the cell viability assay separated out the hypoxia-damaged from the control normoxia-exposed cells. Parallel changes in percent cells killed and CK released [Liang, 1996, 1997; Strickler et al., 1996; Stambaugh et al., 1997; Dougherty et al., 1998; Liang and Jacobson, 1998] further validated this assay for percent cells killed. The amount of CK was measured as enzyme activity (unit/mg) and increases in CK activity above the control level were determined. The percentage of cells killed was calculated as the number of cells obtained from the control group (representing cells not subjected to any hypoxia or drug treatment) minus the number of cells from the treatment group divided by the number of cells in control group multiplied by 100%.

In parallel, ATP content was quantitated by rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen, followed by perchloric acid treatment, neutralization, centrifugation, and bioluminescent measurement. The light emitted following firefly luciferase-catalyzed oxidation of D-luciferin by ATP was determined by a luminometer [Holmsen et al., 1966; Doorey and Barry, 1983]. The ATP level was derived from an ATP calibration curve constructed by quantitating the relative light intensity vs. known amount of ATP. Measurement of basal level of cell injury was made after parallel incubation of control cells under normal O2.

Electrophysiologic Measurement of the KATP Channel Current

To measure the KATP channel current (IK,ATP) directly, patch clamp technique in the whole-cell configuration was employed [Hu et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1996]. Recording was performed in the presence and the absence of KATP opener pinacidil (30 μM) in the superfusate. After a gigaohm seal was formed, the whole-cell configuration was achieved by disrupting the membrane with gentle suction. The internal solution (pH 7.3, adjusted with KOH) contained (in mM) KCl 140, MgCl2 1.5, HEPES 10, ATP 1, glucose 5. The extracellular solution contained (in mM) NaCl 135, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 1.0, CaCl2 1.0, NaH2PO4 0.33, HEPES 10, and glucose 10 at pH 7.4 (adjusted with NaOH). IK,ATP was identified as a current that reversed between −90 and −80, and was stimulated by pinacidil. The voltage-dependence of the current was examined by using 500 ms voltage steps from a holding potential of −40 mV to between −120 and +40 mV, in steps of 10 mV.

Materials

The adenosine analogs 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyl-adenosine (CCPA), 8-sulfophenyltheophylline (8-SPT), and 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) were from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA). 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5’-N-methyluronamide (Cl-IB-MECA) and 3-ethyl 5-benzyl-2-methyl-6-phenyl-4-phenylethynyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (MRS 1191) were synthesized as described [Kim et al., 1994; Jiang et al., 1996]. Adenosine was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Embryonated chick eggs were from Spafas, Inc. (Storrs, CT).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ischemic Preconditioning of the Cultured Cardiac Ventricular Myocyte

Cardiac ventricular myocytes can be preconditioned by a 5-min preconditioning ischemia prior to a 90-min period of sustained simulated ischemia (Fig. 1A). Alternatively, the myocytes can also be preconditioned by a 5-min exposure to either the KATP channel opener pinacidil or the adenosine A1 or A3 receptor agonists CCPA or Cl-IB-MECA (Fig. 1B). Preconditioning, whether induced by the brief preconditioning ischemia or by the receptor agonist or channel opener, can successfully protect the myocytes against the deleterious effect of the prolonged ischemia [Liang, 1996, 1997; Strickler et al., 1996; Stambaugh et al., 1997; Dougherty et al., 1998; Liang and Jacobson, 1998]. To provide further evidence for a role of adenosine receptor in triggering the preconditioning response, myocyte content of ATP was determined and used as another index of injury. Figure 2A demonstrates that the myocyte content of ATP was significantly higher in cells preexposed to the preconditioning ischemia or to A1 agonist CCPA or A3 agonist Cl-IB-MECA. This preservation of ATP content correlated with a decrease in the percentage of cells killed and in the amount of CK released (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the present data further validate the cultured myocyte as a useful model to study the mechanism of ischemic preconditioning.

Fig. 1.

Induction of preconditioning of the cardiac myocytes. Preconditioning can be induced by a 5-min exposure of the cardiac myocytes to (A) simulated ischemia or (B) the adenosine A1 agonist CCPA, the A3 agonist Cl-IB-MECA or KATP channel opener pinacidil. In myocytes preconditioned by the brief ischemia, cells were incubated under normal O2 for 10 min following the 5-min ischemia; cells were then exposed to 90 min of ischemia. In myocytes preconditioned by the receptor agonists or channel opener, the medium containing the receptor agonist or channel opener was replaced with fresh medium lacking the drug, and the myocytes were incubated for a further 10-min period before being exposed to 90 min of simulated ischemia.

Fig. 2.

Effects of prior exposure to preconditioning ischemia, CCPA or pinacidil on the myocyte ATP content, the percentage of cells killed, and the amount of CK released. Cardiac ventricular myocytes were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Myocytes were preconditioned either by a 5-min preexposure to simulated ischemia, CCPA (30 nM), Cl-IB-MECA (10 nM), or pinacidil (10 μM) as described in Figure legend 1. Data were presented as (A) myocyte ATP content and as (B) percent cells killed or as amount of CK released. Data were mean ± SE of six to eight experiments. *Significantly different from nonpreconditioned cells (one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test, P < 0.001).

Role of KATP Channel in Preconditioning of the Cardiac Myocyte

A number of studies suggested an important role of KATP channel in triggering and mediating the preconditioning response [Gross, 1992]. The KATP channel has been directly demonstrated in the human and rabbit cardiac myocytes [Wyatt et al., 1989; Hu et al., 1996]. The channel showed regulation by PKC, implicating its role in mediating the cardioprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning. Using the myocyte ATP content as an index of injury, the current study showed that the KATP channel opener pinacidil was able to precondition the cardiac myocyte. A 5-min preexposure of the myocyte to pinacidil resulted in a higher level of the myocyte ATP during the subsequent period of ischemia as compared to cells not preexposed to pinacidil (Fig. 2A). The pinacidil-induced preservation of ATP content correlated with a decreased number of cardiac myocytes killed and a reduced release of the CK into the medium (Fig. 2B). The data suggest the presence of a functional KATP channel capable of mediating a preconditioning response in the cultured chick ventricular myocyte.

To provide direct evidence for the presence of KATP channel, a patch clamp study was carried out on the myocyte using the whole-cell configuration. Figure 3 shows an inward rectifying current that reversed near the K+ equilibrium potential. Pinacidil caused an increase in the current at the hyperpolarizing potentials during the voltage steps. The presence of pinacidil was associated with an increase in the holding current at −40 mV (data not shown). These data are similar to those reported by others [Hu et al., 1996] and demonstrate directly the presence of the KATP channel current in the cultured chick ventricular myocyte.

Fig. 3.

Pinacidil stimulates the KATP channel current in the cultured cardiac myocyte. Cardiac ventricular myocytes were cultured as described in Materials and Methods. After 24 h in culture, myocytes were patch-clamped in the whole-cell configuration. After a stable patch was achieved, the baseline KATP channel current was obtained. Myocytes were then superfused with the same extracellular solution containing 30 μM pinacidil. The same voltage steps were applied and an increase in the KATP channel current at the hyperpolarizing potential was recorded. The tracing is representative of three other myocytes. In response to pinacidil, the holding current at −40 mV increased significantly (data not shown).

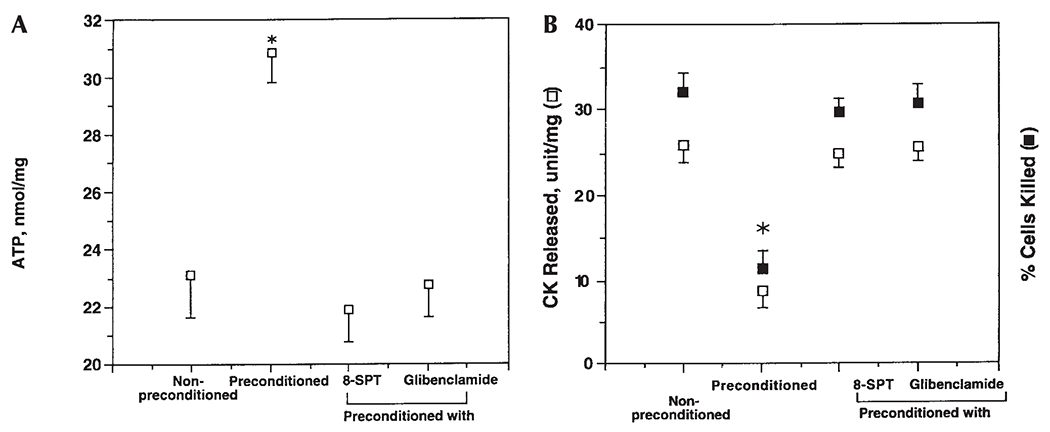

The next series of experiments studied the role of the KATP channel in mediating the cardioprotective effect of preconditioning ischemia. The KATP channel antagonist glibenclamide, when present during the myocyte exposure to preconditioning ischemia, blocked the preconditioning ischemia-induced preservation of ATP content (Fig. 4). Glibenclamide also abolished the preconditioning ischemia-induced decrease in the number of cardiac myocytes killed and the amount of CK released. Together, the data further support the hypothesis, advanced earlier [Gross, 1992; Liang, 1996], that the KATP channel is an important effector in preconditioning the cardiac myocyte.

Fig. 4.

Effects of 8-SPT and glibenclamide on the cardioprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning. Cardiac ventricular myocytes were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Myocytes were preconditioned by a 5-min preexposure to ischemia in the presence or the absence of the nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist 8-SPT (100 μM) or the KATP channel antagonist glibenclamide (1 μM). Data were presented as (A) myocyte ATP content or (B) percentage of cells killed or amount of CK released and were the mean ± SE of seven experiments. *Significantly different from cells preconditioned in the absence of 8-SPT or glibenclamide (one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test, P < 0.001).

Role of Adenosine A1 and A3 Receptors in Mediating the Cardioprotective Effect of Preconditioning Ischemia

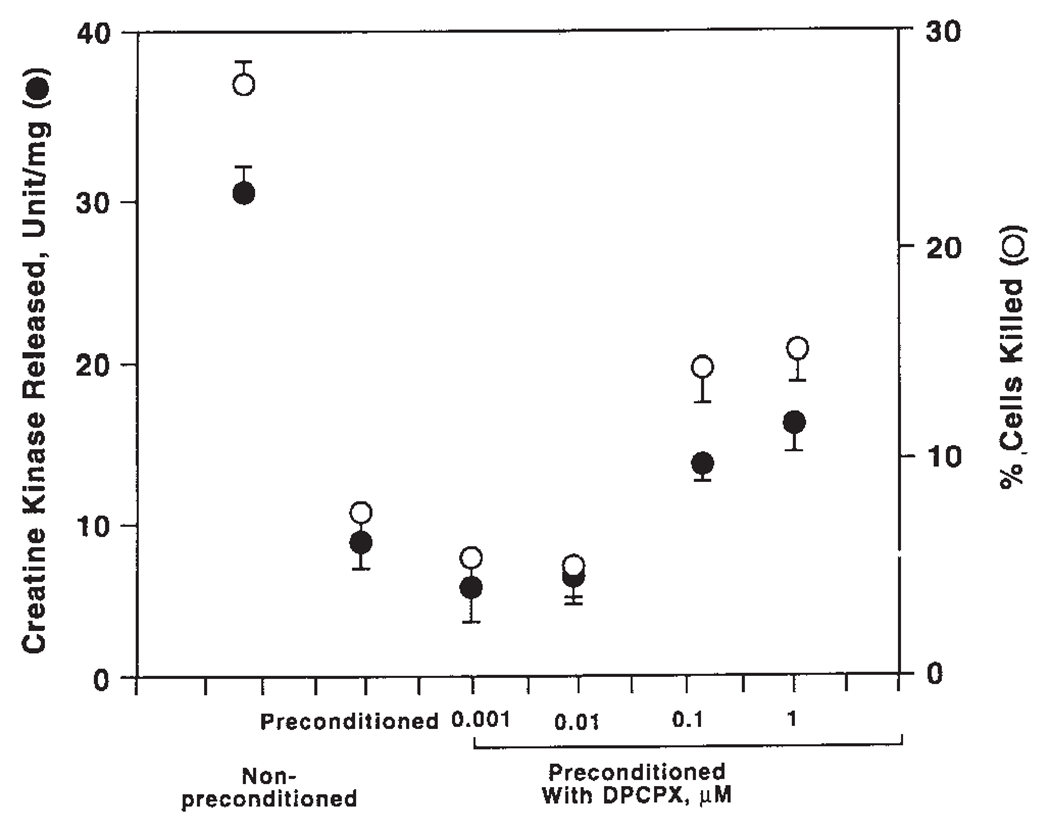

While activation of either the A1 or the A3 receptor can mimic the cardioprotective effect of preconditioning ischemia, the question arises whether both receptors are involved in actually triggering the protective effect of preconditioning ischemia. A prior study suggests that activation of both receptors is needed during the brief preconditioning ischemia to trigger the preconditioning response [Liang and Jacobson, 1998]. Figure 5 and Table 1 provided further evidence for this hypothesis. The A1 receptor-selective antagonist DPCPX, even at 10 μM, can only block part of the protective effect of preconditioning ischemia (Fig. 2A). However, the combined presence of DPCPX and the A3 receptor-selective antagonist MRS1191 during the exposure to preconditioning ischemia completely abolished its protective effect (Table 1). These data provide further support for an essential role of both adenosine receptor subtypes in triggering the cardioprotective effect of preconditioning ischemia.

Fig. 5.

Effects of DPCPX on the cardioprotective effect of preconditioning ischemia. Cardiac ventricular myocytes were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Myocytes were preconditioned in the presence or the absence of varying concentrations of DPCPX. Data were presented as percentage of cells killed or amount of CK released and were the mean ± SE of five experiments. *Significantly different from cells preconditioned in the absence of DPCPX (one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test, P < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Effects of the Combined Presence of Both A1 and A3 Receptor Antagonists on the Protective Effect of Preconditioing Ischemia

| % Cardiac cells killed | Amount of CK released | |

|---|---|---|

| Additions | ||

| None | 7.5 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 |

| DPCPX (1 μM) | 18 ± 3* | 20 ± 3* |

| MRS1191 (1 μM) | 16.5 ± 2* | 17.4 ± 2.2 |

| DPCPX (1 μM) plus | ||

| MRS1191 (1 μM) | 26.5 ± 3 | 29 ± 4 |

| No preconditioning | 28 ± 3 | 32 ± 3 |

Cultured cardiac ventricular myocytes were preexposed to the 5-min preconditioning ischemia in the absence or the presence of the various agents indicated. Myocytes preexposed to the brief preconditioning ischemia represent nonpreconditioned cells. The percentage of cells killed and the amount of CK released (unit/mg) are shown and represent mean ± SE of four experiments.

Significant difference from those determined in the absence of DPCPX or MRS1191 and from those determined in the presence of both DPCPX and MRS1191 (one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test, P < 0.01).

Signaling Mechanisms Underlying the Adenosine Receptor-Mediated Preconditioning Response: A Working Model

The development of a cardiac myocyte model of simulated ischemia and preconditioning should facilitate determination of the mechanisms responsible for the trigger (or initiation) of preconditioning as well as the actual exertion of protection during the subsequent prolonged ischemia (see the model illustrated in Fig. 6). The release of adenosine during the brief preconditioning ischemia activates the adenosine A1 and A3 receptors, resulting in the activation of phospholipase(s), which in turn causes accumulation of diacylglycerol and activation of protein kinase C. Protein kinase C will then activate the KATP channel and keep it “primed” so the channel will become more responsive to the cardioprotective effect of adenosine released during the second, prolonged ischemia. A growing body of evidence is accumulating to support this sequence of signaling events in exerting the protective effect of preconditioning.

Fig. 6.

Signaling mechanisms underlying adenosine receptor-mediated preconditioning effect. The preconditioning (PC) effect can be divided into two phases. In the first phase, the preconditioning effect is initiated. Signaling mechanisms are activated and remain in an activated state during the sustained ischemia. During the sustained ischemia in which the second phase occurs, the actual cardioprotective effect of preconditioning is exerted. A series of signaling events take place during each phase as outlined in a hypothetical working model.

During initiation phase, adenosine is released from the ischemic myocardium, which triggers the preconditioning by activating the adenosine receptor. The receptor is coupled to stimulation of diacylglyceride (DAG) via either phospholipase C or D. A sustained increase in the level of DAG stimulates protein kinase C (PKC), which in turn causes an activated KATP channel. Thus, inhibition of PKC blocks the preconditioning effect elicited by adenosine receptor activation. KATP channel antagonist blocks the preconditioning effect elicited by adenosine agonist or phorbol ester, establishing the sequential activation of adenosine receptor, PKC, and KATP channel as the sequence of signaling events during the initiation of preconditioning. During the second phase, activation of both adenosine receptor and KATP channel is required to exert the actual cardioprotective effect of preconditioning. Central to this hypothesis is the concept that the KATP channel is first primed in an activated state during the initiation phase, and becomes more sensitive to the protective effect of adenosine during the second phase. Ultimately, activation of the channel is responsible for protection against ischemia-induced injury.

Glossary

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- CCPA

2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- Cl-IB-MECA

2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide

- MRS1191

3-ethyl 5-benzyl-2-methyl-6-phenyl-4-phenylethynyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate

- 8-SPT

8-sulfophenyltheophylline

REFERENCES

- Armstrong S, Ganote CE. 1994. Adenosine receptor specificity in preconditioning of isolated rabbit cardiomyocytes: Evidence of A3 receptor involvement. Cardiovasc Res 28:1049–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchampach JA, Grover GJ, Gross GJ. 1992. Blockade of ischemic preconditioning in dogs by the novel ATP dependent potassium channel antagonist sodium 5-hydroxydecanoate. Cardiovas Res 26:1054–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbitt DG, Virmani R, Forman MB. 1989. Intracoronary adenosine administered after reperfusion limits vascular injury after prolonged ischemia in the canine model. Circulation 80:1388–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry WH, Smith TW. 1982. Mechanisms of transmembrane calcium movement in cultured chick embryo ventricular cells. J Physiol 325:243–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribier AL, Korsatz R, Koning P Rath H, Gamra H, Stix G, Merchant S, Chan C, Letac B. 1992. Improved myocardial ischemic response and enhanced collateral circulation with long repetitive coronary occlusion during angioplasty: A prospective study. J Am Coll Cariol 20:578–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaan RL. 1967. Developmental changes in the calcium currents in embryonic chick ventricular myocytes. Dev Biol 16:216–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch E, Berger M, Kussmaul WG, Hirshfield JW, Hermann HC, Laskey WK. 1990. Adaptation to ischemia during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: Clinical, hemodynamic, and metabolic features. Circulation 82:2044–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorey AJ, Barry WH. 1983. The effects of inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis on contractility and high-energy phosphate content in cultured chick heart cells. Circ Res 53:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty C, Barucha J, Jacobson KA, Liang BT. 1998. Cardiac myocytes rendered ischemia-resistant by expressing the human adenosine A1 or A3 receptor. FASEB J (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey JM. 1992. Ischemic preconditioning. Nature’s own cardioprotective intervention. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2:170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely SW, Berne RM. 1992. Protective effects of adenosine in myocardial ischemia. Circulation 85:893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galper JB, Smith TW. 1978. Properties of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in heart cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 75:5831–5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross GJ. 1992. ATP-sensitive potassium channels and myocardial preconditioning. Basic Res Cardiol 90:85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmsen H, Holmsen I, Bernhardsen A. 1966. Microdetermination of adenosine diphosphate and adenosine triphosphate in plasma with the firefly luciferase system. Anal Biochem 17:456–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K, Duan D, Li G-R, Nattel S. 1996. Protein kinase C activates ATP-sensitive K+ current in human and rabbit ventricular myocytes. Circ Res 78:492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidis JS, Tumiati LC, Weisel RD, Mickle DAG, Li R-K (1994): Preconditioning human ventricular cardiomyocytes with brief periods of simulated ischemia. Cardiovasc Res 28:1285–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J-L, van Rhee AM, Melman N, Ji XD, Jacobson KA. 1996. 6-Phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives as potent and selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J Med Chem 39:4667–4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HO, Ji X, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 1994. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5′-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem 37:3614–3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GC, Vasquez JA, Gallagher KP, Lucchesi BR. 1990. Myocardial protection with preconditioning. Circulation 82:609–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT. 1989. Characterization of the adenosine receptor in cultured embryonic chick atrial myocytes: Coupling to modulation of contractility and adenylyl cyclase activity and identification by direct radioligand binding. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 249:775–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT. 1992. Adenosine receptors and cardiovascular function. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2:100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT. 1996. Direct preconditioning of cardiac ventricular myocytes via adenosine A1 receptor and KATP channel. Am J Physiol 271(Heart Circ. Physiol 40):H1769–H1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT. 1997. Protein kinase C-mediated preconditioning of cardiac myocyte: Role of adenosine receptor and KATP channel. Am J Physiol 273(Heart Circ. Physiol. 42):H847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT, Haltiwanger B. 1995. Adenosine A2a and A2b receptors in cultured fetal chick ventricular cells. High- and low-affinity coupling to stimulation of myocyte contractility and cyclic AMP accumulation. Circ Res 76:242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT, Jacobson KA. 1998. A physiological role of adenosine A3 receptor: Sustained cardioprotection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:6995–6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT, Morley FJ. 1996. A new Gs-mediated, cyclic AMP-independent stimulatory mechanism via adenosine A2a receptor in the intact cardiac cell. J Biol Chem 271:18678–18685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT, Hellmich MR, Neer EJ, Galper JB. 1986. Development of muscarinic cholinergic inhibition of adenylate cyclase in embryonic chick hearts: Its relationship to changes in the inhibitory guanine nucleotide regulatory protein. J Biol Chem 261:9011–9021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Gao WD, O’Rourke B, Marban E. 1996. Synergistic modulation of ATP-sensitive K+ currents by protein kinase C and adenosine. Implications for ischemic preconditioning. Circ Res 78:443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JD, Lachance D, Kim D. 1985. Mechanism of β-adrenergic receptor regulation in cultured chick heart cells. Circ Res 57:171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestril R, Chi S-H, Sayen MR, O’Reilly K, Dillmann WH. 1994. Expression of inducible stress protein 70 in rat heart myogenic cells confers protection against simulated ischemia-induced injury. J Clin Invest 93:759–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Ogawa T, Iwamoto T, Shimamoto K, Iimura O. 1992. Dipyridamole potentiates the myocardial infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning. Circulation 86:979–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. 1986. Preconditioning with ischemia: A delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 74:1124–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsson B, Forman MB, Puett DW, Pou A, Cates CU. 1987. Reduction of reperfusion injury in the canine preparation by intracoronary adenosine: Importance of the endothelium and the no-reflow phenomenon. Circulation 76:1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Rose J, Heusch G. 1994. Involvement of activation of ATP-dependent potassium channels in ischemic preconditioning in swine. Am J Physiol 267:H1341–H1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambaugh K, Jiang J-L, Jacobson KA, Liang BT. 1997. Novel cardioprotective function of adenosine A3 receptor during prolonged simulated ischemia. Am J Physiol 273(Heart Circ Physiol 42):H501–H505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimers JR, Liu S, Lieberman MJ. 1991. Apparent affinity of the Na/K pump for ouabain in cultured chick cardiac myocytes. J Gen Physiol 98:815–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickler J, Jacobson KA, Liang BT. 1996. Direct preconditioning of cultured chick ventricular myocytes: Novel functions of cardiac adenosine A2a and A3 receptors. J Clin Invest 98(8):1773–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomai F, Crea F, Caspardone A, Versaci F, DePaulis R, Penta de Peppo A, Chiariello L, Gioffré PA. 1994. Ischemic preconditioning during coronary angioplasty is prevented by gliben-cladmide, a selective ATP-sensitive K+ channel blocker. Circulation 90:700–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster KA, Discher DJ, Bishopric NH. 1995. Cardioprotection in an in vitro model of hypoxic preconditioning. J Mol Cell Cardiol 27:453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt D, Ely SW, Lasley RD, Walsh R, Mainwaring R, Berne RM, Mentzer RM. 1989. Purine-enriched asanguineous cardioplegia retards adenosine triphosphate degradation during ischemia and improves post ischemic ventricular function. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 97:771–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Miller J, Liang BT. 1992. High-efficiency gene transfer into cardiac myocytes. Nucleic Acids Res 20:6425–6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Gross GJ. 1994. A comparison of adenosine-induced cardioprotection and ischemic preconditioning in dogs. Efficacy, time course, and role of KATP channels. Circulation 89:1229–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]