Abstract

Objective:

Standard methods to evaluate tracheal pathology in children, including bronchoscopy, may require general anesthesia. Conventional dynamic proximal airway imaging in noncooperative children requires endotracheal intubation and/or medically induced apnea, which may affect airway mechanics and diagnostic performance. We describe a technique for unsedated dynamic volumetric computed tomography angiography (DV-CTA) of the proximal airway and surrounding vasculature in children and evaluate its performance compared to the reference-standard of rigid bronchoscopy.

Methods:

Children who had undergone DV-CTA and bronchoscopy in one-year were retrospectively identified. Imaging studies were reviewed by an expert reader blinded to the bronchoscopy findings of primary or secondary tracheomalacia. Airway narrowing, if present, was characterized as static and/or dynamic, with tracheomalacia defined as >50% collapse of the tracheal cross-sectional area in exhalation. Pearson correlation was used for comparison.

Results:

Over a 19-month period, we identified 32 children (median age 8 months, range 3–14 months) who had undergone DV-CTA and bronchoscopy within a 90-day period of each other. All studies were unsedated and free-breathing. The primary reasons for evaluation included noisy breathing, stridor, and screening for tracheomalacia. There was excellent agreement between DV-CTA and bronchoscopy for diagnosis of tracheomalacia (κ = 0.81, p < 0.001), which improved if children (n = 25) had the studies within 30 days of each other (κ = 0.91, p < 0.001). CTA provided incremental information on severity, and cause of secondary tracheomalacia.

Conclusion:

For most children, DV-CTA requires no sedation or respiratory manipulation and correlates strongly with bronchoscopy for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia.

Keywords: bronchomalacia, dynamic CT, dynamic volumetric CT, tracheomalacia

INTRODUCTION

Tracheomalacia is a common disease of childhood, affecting up to 1:2100 children.1,2 The symptoms of tracheomalacia are often nonspecific and can be intermittent, which can lead to a delay in diagnosis. Primary tracheomalacia is defined by inherent collapsibility of the trachea due to weakness of cartilage rings leading to airway collapse during respiration. Secondary or acquired tracheomalacia is the result of collapse of the normal tracheal framework from external compression, inflammation, or iatrogenic causes.3,4 Since the symptoms of tracheomalacia are often confused with other common diseases, including asthma, there is a need for rapid noninvasive screening modalities for the disease, which can characterize static and dynamic airway pathology. Conventional imaging approaches to diagnosis of proximal airway disease have required endotracheal intubation or controlled ventilation with a facemask to achieve paired inspiration and expiration images.5 The technique may itself alter airway mechanics, and artificially stent the airway open, thereby reducing sensitivity for diagnosis of airway compression or dynamic collapse. The reference standard for diagnosis of tracheomalacia is bronchoscopy under anesthesia with spontaneous ventilation, identifying collapse of the trachea with expiration.6 Unfortunately, this technique requires a precise plane of general anesthesia, and may also artifactually result in airway stenting or hypoventilation.7 In addition, children may require further investigation to determine the cause if extrinsic compression is suspected. Computed tomography (CT) is often used to assist with the diagnosis of tracheomalacia to distinguish primary from secondary causes, which requires the use of intravenous contrast for mediastinal and vascular assessment. The advent of newer CT technology, including multidetector computerized tomography (MDCT), volumetric CT, and dual-source CT has improved the ability to perform unsedated, dynamic assessment of the airway in adults and children due to their speed, and volumetric coverage of the airway.8–11 In adults, dynamic CTA has been shown to correlate strongly with bronchoscopy for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia.12 But the accuracy of these techniques for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia in children when compared to bronchoscopy has not been established. We describe our experience with evaluation of children with suspected tracheomalacia using unsedated, free-breathing dynamic volumetric CT angiography (DV-CTA) with a volumetric 320-detector array CT scanner. We hypothesized that DV-CTA accurately diagnoses tracheomalacia in children when compared to the reference-standard of bronchoscopy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

Permission for a retrospective chart review was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. A retrospective chart review was performed of all individuals <21 years of age who underwent imaging of the chest using a DV-CTA at our institution from March 2017 to September 2018. Within this sub-group, we identified children who also underwent bronchoscopy by pediatric otolaryngology within 90 days of DV-CTA. There was a subset of patients who underwent rigid bronchoscopy and CT imaging on the same day. This subset two major groups of patients: (1) patients followed by a pulmonologist and a concurrent imaging study of the lungs was scheduled prior to operative intervention where a multi-disciplinary procedure with both otolaryngology and pulmonary performed an airway evaluation (the most common scenario), or (2) operative findings identified concern for vascular ring or sling and the patient subsequently underwent DV-CTA to assess for this. We excluded patients who were deceased, had inadequate bronchoscopy records, or had bronchoscopy performed using a ventilating bronchoscope. Chart review was performed to collect demographic information, including sex, age, and medical comorbidities, and to identify the primary airway diagnosis.

Bronchoscopy and DV-CTA Technique and Diagnostic Criteria for Tracheomalacia

Bronchoscopy Technique and Interpretation.

All patients underwent rigid bronchoscopy under general anesthesia. Under spontaneous ventilation and laryngoscopy, the Hopkins rod telescope was guided into the tracheal airway. The presence of tracheomalacia on bronchoscopy was defined using standard clinical practice guidelines, which is >50% collapse of the airway during respiration.13,14 Static narrowing was characterized by identifying flattening or distortion of the native tracheal caliber, and dynamic narrowing as distortion that occurred with respiration. The primary operator was an experienced and board-certified pediatric otolaryngologist performing real-time observation and using a structured reporting template; the bronchoscopy report was used for final analysis. The reporting template includes subjective description of the airway subsites (oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, subglottis, trachea, and bronchi), endotracheal tube sizing, vocal cord mobility, and presence of a laryngeal cleft. The operator was aware of any radiographic and clinical findings at the time of the procedure since these procedures were performed as part of routine clinical care. Four patients in whom discordance was noted between CT and bronchoscopy findings also had bronchoscopy images and video and the CT images reviewed jointly by an expert otolaryngologist (T.C.) and expert imaging reader (R.K.) to ensure that all locations and elements of the structured reporting template were included in the report. There were four identified disagreements using these criteria, and one bronchoscopy diagnosis was changed on secondary review.

DV-CTA Technique and Interpretation.

All studies are performed using a Canon Aquilion One 320 detector array scanner (Canon Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). Our group has previously described the technical elements of a low-radiation dose, unsedated, free-breathing DV-CTA protocol for the detection and assessment of intrinsic and extrinsic airway compromise in children,15 and have described applications of this protocol in innominate artery compression in children.16 kVp of 80 is applied in all patients, mA between 10 and 40 depending on patient size, and rotation time of 0.35 s. Coverage is from the larynx (using hyoid bone as landmark) to below the mainstem bronchi (using top of diaphragm as landmark). The respiratory rate is determined prior to the study, with a cine approach with a temporal resolution of 0.35 s used in patients with RR > 30/min, and an intermittent volume every 1.4 s in RR < 30/min (Fig. 1). Typically, 5–8 volumes (dynamics) are obtained to sample 1.5–2 respiratory cycles with either the cine or the intermittent approach. The radiation exposure varies based on extent of coverage, body habitus, and number of dynamics, averaging between 0.1 and 0.3 mSv per dynamic. Average mAs was 36 (range 20–50), average number of dynamics was 6.5 (range 5–9), and average effective dose was 1.48 mSv (range 0.6–3.01). The studies are performed without sedation, and with free-breathing, allowing imaging during normal respiration.

Fig. 1.

DV-CTA overview. (A [a–d]) Axial CT images at the level of the aortic arch across four phases of a dynamic volumetric computed tomography angiography (DV-CTA) in a 4-year-old unsedated male showing the contrast moving from the pulmonary artery to the aorta during the acquisition providing angiographic information, while the lung windows show changes in volume and lucency consistent with transition across the respiratory cycle providing dynamic airway and lung information. The trachea demonstrates severe tracheomalacia with approximately 70% reduction in cross-sectional caliber in expiration (open yellow arrow); (B) Schematic of the continuous acquisition method in patients with respiratory rate of >30/min, and the intermittent acquisition method in patients with respiratory rate of <30/min. This allows sampling of approximately 5–8 volumes over 1.5–2 respiratory cycles, providing robust assessment of dynamic changes involving the proximal airway and lungs; (C) 3D DV-CTA reconstruction of secondary tracheomalacia due to a crossing innominate artery in a 3-year-old female (*trachea, solid arrow—secondary tracheomalacia.

Interpretation of DV-CTA.

A single-expert reader, blinded to the clinical data and to the bronchoscopy findings, reinterpreted all the studies on a dedicated 3D workstation according to a structured interpretation template. Peak inspiratory and end-expiratory phases were identified based on lung and thoracic motion. Static or fixed narrowing, termed Maximal Airway Change (MAC) at any location was determined in inspiration and quantified using tracheal cross-sectional area (CSA) compared to a normal segment of the trachea as follows: MAC = CSA at narrowed segment in inspiration/CSA of trachea at thoracic inlet in inspiration. Severity of MAC was classified as follows: mild: 33%–49%, moderate: 50%–66%, severe: >67%. Dynamic narrowing, termed excessive dynamic airway collapse (EDAC), was defined as >50% reduction in CSA in expiration at any given location as follows: (EDAC = CSA at airway segment in expiration/CSA at same location in inspiration). Severity of EDAC was classified as follows: mild: 50%–74%, moderate: 75%–89%, severe: >90%. If tracheomalacia was identified, it was characterized as purely dynamic narrowing or combined static and dynamic narrowing, since secondary tracheomalacia is frequently characterized by the latter. Primary versus secondary tracheomalacia was determined based on the presence of identifiable extrinsic causes, including vascular mediated airway compromise or mediastinal pathology. Figure 1 shows an example of the types of clinical images obtained. The presence of air trapping and atelectasis in the lung parenchyma was also evaluated.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). The interuser agreement of bronchoscopy and DV-CTA was compared using a Cohen’s Kappa statistic as previously described for the presence or absence of tracheomalacia,17 with excellent agreement as 0.81–1.00 and substantial agreement as 0.61–0.80.

RESULTS

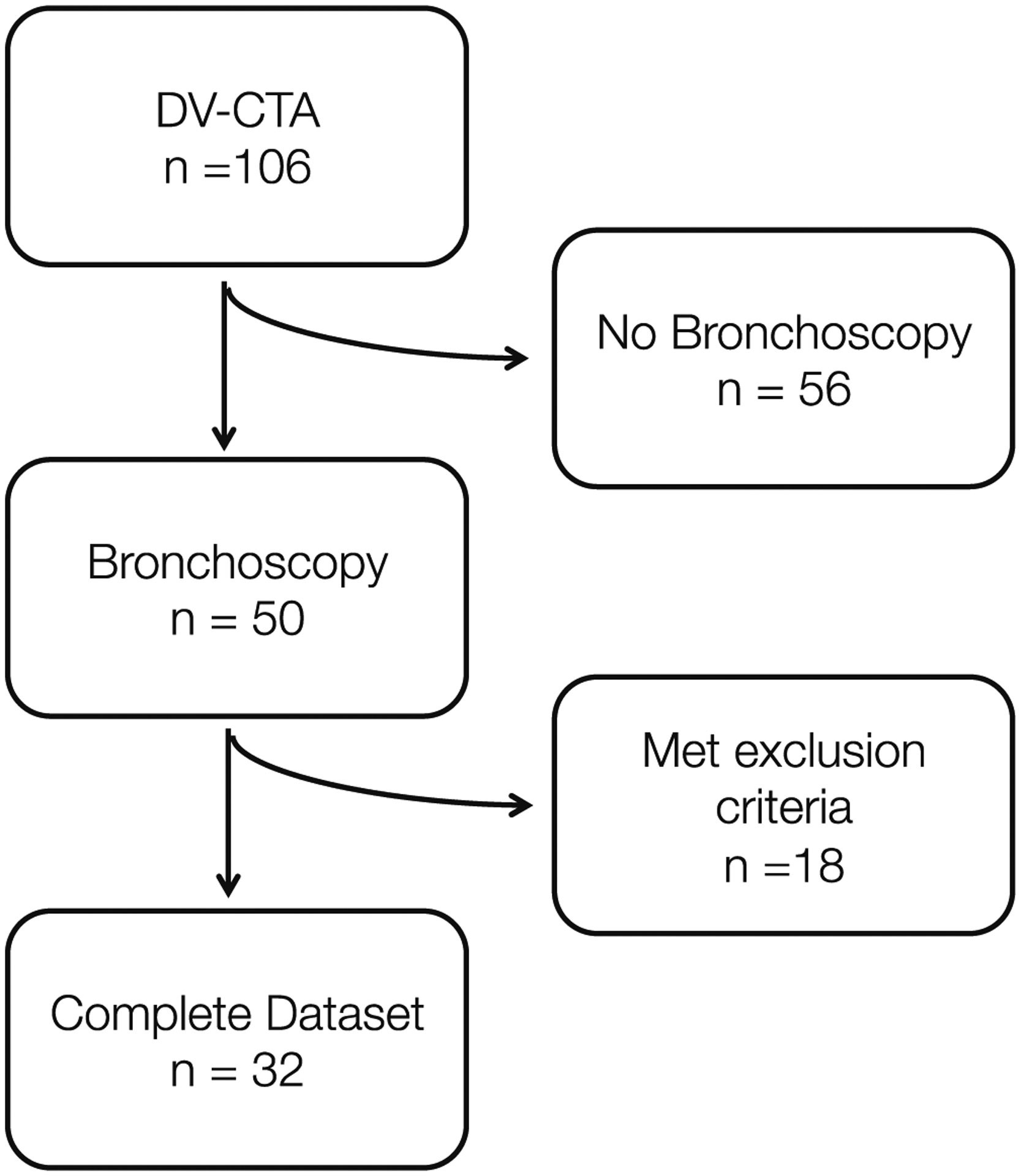

In the 19-month study period, 106 patients underwent DV-CTA. Of these, 50 also underwent rigid bronchoscopy by a pediatric otolaryngologist. After further review, six were excluded for not having a bronchoscopy within 90 days of imaging, six for insufficient bronchoscopy documentation, one for being deceased, one for advanced age (32 years), and four for concerns of iatrogenic airway manipulation during the procedure (three from ventilating bronchoscope, and one for being intubated during DV-CTA) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of inclusion into DV-CTA cohort analysis. DV-CTA, dynamic volumetric computed tomography angiography.

Of the remaining 32 children in the cohort, 23 (68.8%) were male. The cohort had a median age of 8 months (interquartile range 3–14 months). The most common medical comorbidities were gastroesophageal reflux (n = 12), congenital heart disease (n = 12), pulmonary infection (n = 8), and trisomy 21 (n = 5) (Table I).

TABLE I.

Cohort Characteristics and Demographics.

| Demographic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 22 (68.8) |

| Medical comorbidity | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 12 (37.5) |

| Feeding intolerance | 4 (12.5) |

| G-tube dependent | 3 (9.4) |

| Congenital heart disease | 12 (37.5) |

| Pulmonary HTN | 2 (6.3) |

| Pulmonary infection | 8 (25) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 2 (6.3) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 2 (6.3) |

| Trisomy 21 | 5 (15.6) |

| Other genetic disorder | 1 (3) |

| Bronchoscopy | |

| Same day | 10 (31.3) |

| Bronchoscopy first | 8 (25) |

| DV-CTA first | 14 (43.8) |

| Within 30 days of each other | 24 (75) |

Abbreviation: DV-CTA, dynamic volumetric computed tomography angiography.

The most common primary indication for DV-CTA was screening for tracheomalacia (n = 13, 40.6%). Other reasons for obtaining DV-CTA included noisy breathing/stridor (n = 8, 25%), evaluation for a vascular ring/anomaly (n = 7, 21.9%), or for other reasons (n = 4, 12.5%). Imaging was obtained on the same day as bronchoscopy for 10 children (31.3%), prior to bronchoscopy for 14 children (43.8%), and after bronchoscopy for 9 (25%) (Table I).

Approximately one-third of children were found to have a normal airway either on imaging (n = 11, 34%) or on bronchoscopy (n = 9, 28.1%) (Table II). Fourteen children (43.8%) were diagnosed with tracheomalacia on DV-CTA, of which 11 (34.4%) had secondary tracheomalacia and 3 primary tracheomalacia (9.4%). On bronchoscopy, 15 (46.9%) patients had tracheomalacia, with 12 suspected to have secondary tracheomalacia. The interobserver agreement between radiologists and surgeons was excellent (κ = 0.81, p < 0.001), with three disagreements (two patients diagnosed on bronchoscopy but not on DV-CTA and one diagnosed on DV-CTA but not on bronchoscopy). Considering bronchoscopy as the reference-standard, DV-CTA has a sensitivity of 93.3% and a specificity of 88.2% for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia. When looking at a subpopulation of children (n = 24) who had bronchoscopy within 30 days of DV-CTA, the interobserver agreement improved (κ = 0.91, p < 0.001), with only one child being diagnosed on DV-CTA and not on bronchoscopy, yielding a specificity and sensitivity of 100% and 92.9% for CTA for tracheomalacia. For the 12 children who had static narrowing of the trachea there was complete agreement between surgical and radiologic diagnosis, with CT determining intrinsic versus extrinsic cause (i.e., vascular ring or vascular compression) of the narrowing in all cases (Fig. 3).

TABLE II.

Primary Diagnosis Made on DV-CTA and Bronchoscopy.

| DV-CTA | Bronchoscopy | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Normal | 11 (34.4) | 9 (28.1) |

| Tracheomalacia | 14 (43.8) | 15 (46.9) |

| Primary tracheomalacia | 3 (9.4) | - |

| Secondary tracheomalacia | 11 (34.4) | - |

| Subglottic stenosis | 3 (9.4) | 2 (6.3) |

| Laryngomalacia | NA | 4 (12.5) |

| Other | 4 (12.5) | 2 (6.3) |

Abbreviation: DV-CTA, dynamic volumetric computed tomography angiography.

Fig. 3.

Secondary tracheomalacia due to innominate artery compression. (A,B) Bronchoscopy and corresponding DV-CTA reveals patent proximal trachea (open arrow on axial scan), (C,D) Endoscopic view of fixed collapse of distal trachea secondary to innominate artery compression (solid arrow on axial scan). (E,F) 3D reconstructions of anterior (E) and sagittal view (F) of the airway demonstrate collapse (solid arrow). DV-CTA, dynamic volumetric computed tomography angiography.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we demonstrate that DV-CTA, an unsedated, volumetric, free-breathing CT technique, accurately diagnosed tracheomalacia when compared with reference-standard bronchoscopy in children. In addition, DV-CTA was able to determine the etiology of secondary tracheomalacia in all patients. This study is the first to compare DV-CTA findings to bronchoscopy for pediatric tracheomalacia.

Like most pediatric aerodigestive patient populations, our cohort was medically complex and exhibited pulmonary and gastrointestinal manifestations in addition to those typically ascribed to tracheomalacia. Many of the patients in our cohort were co-managed with pediatric medical sub-specialties, and the decision to proceed with DV-CTA was multifactorial (i.e., beyond evaluation of tracheomalacia, including the evaluation of aspiration, recurrent pneumonia, bronchitis, and chronic cough). The decision to proceed with diagnostic evaluations, particularly those that require general anesthesia, can be challenging. DV-CTA presents an alternative that may reveal opportunities to guide additional medical and surgical management without the burden of operative intervention.

Although bronchoscopy remains the reference-standard for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia, it is not without limitations. During operative bronchoscopy, the operator cannot definitively differentiate between primary and secondary tracheomalacia without further imaging. Quantitative assessment of the severity of static and dynamic narrowing in bronchoscopy is visual and subjective and plagued by observer differences. DV-CTA may be a better primary modality for initial assessment since it provides quantitative metrics of the severity of the static and dynamic components of airway compromise, determines the presence and cause of secondary tracheomalacia, while also evaluating end-organ changes and complications in the lungs. However, due to the low dose technique of DV-CTA, parenchymal evaluation of the lungs is limited when compared to higher dose chest CT protocols. Other advantages of DV-CTA over previous approaches include free-breathing assessment at tidal volumes, avoidance of sedation and respiratory manipulation, and simultaneous angiographic assessment of the cardiovascular structures, mediastinum, and lungs, possibly serving as a one-stop-shop for pediatric airway assessment.

Conventional MDCT protocols for the airway require sedation with controlled apnea or general endotracheal intubation18 in children that are unable to follow breath-holding commands. General anesthesia is also required for bronchoscopy in children. There has been a growing understanding that exposure to anesthesia in young children may not be without long-term effects; in animal models, early exposure to anesthetics leads to neurotoxicity and neurocognitive compromise.19–21 Although the clinical evidence for the role of early anesthesia exposures in children is less conclusive,22,23 there is still a current push to limit anesthetic exposure in children. This goal needs to be balanced against the risk of diagnostic errors and poor image quality related to motion and to abbreviated studies, especially for high-risk children (premature children or children with significant medical co-morbidities) who may be at greater risk for anesthetic complications, DV-CTA may provide a reliable nonsedated alternative with excellent sensitivity for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia.

Although standard MDCT has been described for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia in young children, traditional MDCT usually necessitates a general anesthestic with intubation to obtain paired inspiratory and expiratory images.4,6 Intubation may create artifactual airway stenting and mask underlying intrinsic disease. Additionally, breath-holding techniques using maximal inspiration and expiration require an artificial re-creation of the respiratory cycle by the anesthesiologist and underestimate airway collapse.14 By comparison, DV-CTA captures a child’s natural respiratory cycle at tidal volumes without sedation, providing a clinically relevant and physiological assessment of the airway.

A pitfall of using cine CT or intermittent dynamic CT for volumetric airway assessment is increased exposure to ionizing radiation, exacerbated by the need for multiple acquisitions at inspiration and expiration for detection of dynamic changes. The use of advanced iterative reconstruction techniques and volumetric detector array as opposed to a helical approach have facilitated a reduction in radiation exposure in DV-CTA. Dynamic volumetric CT has been described previously in adults24,25 and children10,11,24,26 with doses less than for traditional chest imaging. In a group of 24 children, a previous study reported a mean effective dose of 1.7 mSv without compromising image quality.11 Recent papers have described ultra-low-dose dynamic volume CT using practiced breath-holding to obtain optimal images, while decreasing the overall CT dose to <0.01 mSv.27 Although this specific technique has less utility in young children because of their inability to cooperate with breath-holding instructions, future methodologies that use respiratory gating combined with volumetric coverage will allow acquisition of 2 low dose volumes at peak inspiration and end-expiration, which might lead to further reduction (60%–70%) in radiation exposure associated with low dose dynamic CT. Because of these previous investigations of this imaging technique with acceptable quality results, DV-CTA was introduced in our institution as a lower-dose alternative for angiography and chest imaging for children but this is the first study, to our knowledge, that compares imaging findings between DV-CTA and bronchoscopy.

In our cohort DV-CTA was particularly effective for children with secondary tracheomalacia, as there was perfect interuser agreement between surgeons and radiologists regarding these techniques. For children with secondary tracheomalacia, DV-CTA is particularly powerful as it can show both degree of airway compression and etiology, helping to determine the need for further surgical intervention. Because of the retrospective of the study and complexity of the patient population, less information was available on initial symptom presentation of patients in our cohort. Because the clinical symptoms of tracheomalacia can be difficult to differentiate from other airway disease, future work should examine which symptoms should trigger early evaluation of the airway to help determine which children are the best candidates for DV-CTA.

This study is not without limitations. Because of its retrospective nature, surgeons were not blinded to the imaging diagnosis at the time of operative bronchoscopy. There also may concern selection bias for children undergoing bronchoscopy, for instance if a child underwent a DV-CTA which showed no evidence of tracheomalacia, the surgeon may have elected not to proceed with bronchoscopy. For some children, including children with severe autism or developmental delay, despite the limited time required for imaging, they still may not be able to cooperate to allow imaging to happen without sedation. Furthermore, the low dose technique of DV-CTA, parenchymal evaluation of the lungs is limited when compared to higher dose chest CT protocols so may not be as helpful to identify pulmonary pathology.

In addition, there was variability in the assessment of severity of tracheomalacia that is surgeon dependent on bronchoscopy, limiting comparison with CT. Also, the use of a single-expert radiology reviewer may introduce bias in definitive diagnosis. Future studies should examine how the radiologic interrater reliability compares to bronchoscopic interrater reliability to help better compare these two important methods of airway evaluation. A better standardized approach to quantitation of static and dynamic airway collapse on bronchoscopy that corresponds with analogous findings on CT needs to be developed, along with a shared structured interpretation template as described in this article.

CONCLUSION

Dynamic volumetric CT chest angiography demonstrates high accuracy for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia when compared to bronchoscopy. This noninvasive, diagnostic technique avoids the need for sedation or respiratory manipulation, provides quantitative data on static and dynamic airway compromise, and diagnoses the etiology of secondary tracheomalacia.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: 3

REFERENCES

- 1.Boogaard R, Huijsmans SH, Pijnenburg MW, Tiddens HA, de Jongste JC, Merkus PJ. Tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children: incidence and patient characteristics. Chest. 2005;128:3391–3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallis C, Alexopoulou E, Anton-Pacheco JL, et al. ERS statement on tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children. Eur Respir J. 2019;54: 1902271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deacon JWF, Widger J, Soma MA. Paediatric tracheomalacia—a review of clinical features and comparison of diagnostic imaging techniques. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;98:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snijders D, Barbato A. An update on diagnosis of tracheomalacia in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2015;25:333–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee EY, Boiselle PM. Tracheobronchomalacia in infants and children: multidetector CT evaluation. Radiology. 2009;252:7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masters IB, Chang AB. Tracheobronchomalacia in children. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2009;3:425–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngerncham M, Lee EY, Zurakowski D, Tracy DA, Jennings R. Tracheobronchomalacia in pediatric patients with esophageal atresia: comparison of diagnostic laryngoscopy/bronchoscopy and dynamic airway multidetector computed tomography. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagnetz U, Roberts HC, Chung T, Patsios D, Chapman KR, Paul NS. Dynamic airway evaluation with volume CT: initial experience. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2010;61:90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goo HW. Free-breathing cine CT for the diagnosis of tracheomalacia in young children. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:922–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan JZ, Crossett M, Ditchfield M. Dynamic volumetric computed tomographic assessment of the young paediatric airway: initial experience of rapid, non-invasive, four-dimensional technique. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2013;57:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg SB, Dyamenahalli U. Dynamic pulmonary computed tomography angiography: a new standard for evaluation of combined airway and vascular abnormalities in infants. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KS, Sun MRM, Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Majid A, Boiselle PM. Comparison of dynamic expiratory CT with bronchoscopy for diagnosing airway malacia: a pilot evaluation. Chest. 2007;131:758–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin B Tracheomalacia in infants and children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93:438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi S, Lawlor C, Rahbar R, Jennings R. Diagnosis, classification, and management of pediatric tracheobronchomalacia: a review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodd NLK, Masand P, Jadhav S, Bisset G, Krishnamurthy R. Dynamic volume CTA of the airway and vasculature in children: technical report. Paper presented at 58th Annual Meeting and Post-Graduate Course, Society of Pediatric Radiology. Bellevue, WA, May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons KDN, Sorensen J, Jadhav S, Krishnamurthy R, Masand P. Low-dose free breathing dynamic volume CT angiography in the evaluation of innominate artery compression of the trachea. Paper presented at 58th Annual Meeting and Post-Graduate Course, Society of Pediatric Radiology. Bellevue, WA, May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landis JR, Koch GG. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics. 1977;33:363–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee EY, Litmanovich D, Boiselle PM. Multidetector CT evaluation of tracheobronchomalacia. Radiol Clin North Am. 2009;47:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creeley C, Dikranian K, Dissen G, Martin L, Olney J, Brambrink A. Propofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(Suppl 1): i29–i38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Absalom AR, Blomgren K, et al. Anaesthetic neurotoxicity and neuroplasticity: an expert group report and statement based on the BJA Salzburg Seminar. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rappaport BA, Suresh S, Hertz S, Evers AS, Orser BA. Anesthetic neurotoxicity—clinical implications of animal models. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:796–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clausen NG, Kahler S, Hansen TG. Systematic review of the neurocognitive outcomes used in studies of paediatric anaesthesia neurotoxicity. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:1255–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun LS, Li G, Miller TL, et al. Association between a single general anesthesia exposure before age 36 months and neurocognitive outcomes in later childhood. JAMA. 2016;315:2312–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleck RJ, Ishman SL, Shott SR, et al. Dynamic volume computed tomography imaging of the upper airway in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:189–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wielputz MO, Eberhardt R, Puderbach M, Weinheimer O, Kauczor HU, Heussel CP. Simultaneous assessment of airway instability and respiratory dynamics with low-dose 4D-CT in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a technical note. Respiration. 2014;87:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May LA, Jadhav SP, Guillerman RP, et al. A novel approach using volumetric dynamic airway computed tomography to determine positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) settings to maintain airway patency in ventilated infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49: 1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen SL, Ben-Levi E, Karp JB, et al. Ultralow dose dynamic expiratory computed tomography for evaluation of tracheomalacia. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2019;43:307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]