Highlights

-

•

CEP can significantly inhibits PDCoV binding, entry, and replication in LLC-PK1 cells.

-

•

In silico data and SPR results indicate that CEP targets pAPN and PDCoV binding sites in cells to inhibits PDCoV infection.

-

•

CEP reduces inflammatory signaling caused by PDCoV infection.

-

•

CEP inhibits PDCoV replication by inducing autophagy.

-

•

CEP confers broad-spectrum resistance to other coronaviruses (TGEV and MHV).

Keywords: Porcine deltacoronavirus, Cepharanthine, Entry, Replication, Antivirals

Abstract

Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) is an emerging swine enteropathogenic coronavirus (CoV) that mainly causes acute diarrhea/vomiting, dehydration, and mortality in piglets, possessing economic losses and public health concerns. However, there are currently no proven effective antiviral agents against PDCoV. Cepharanthine (CEP) is a naturally occurring alkaloid used as a traditional remedy for radiation-induced symptoms, but its underlying mechanism of CEP against PDCoV has remained elusive. The aim of this study was to investigate the anti-PDCoV effects and mechanisms of CEP in LLC-PK1 cells. The results showed that the antiviral activity of CEP was based on direct action on cells, preventing the virus from attaching to host cells and virus replication. Importantly, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) results showed that CEP has a moderate affinity to PDCoV receptor, porcine aminopeptidase N (pAPN) protein. AutoDock predicted that CEP can form hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues (R740, N783, and R790) in the binding regions of PDCoV and pAPN. In addition, RT-PCR results showed that CEP treatment could significantly reduce the transcription of ZBP1, cytokine (IL-1β and IFN-α) and chemokine genes (CCL-2, CCL-4, CCL-5, CXCL-2, CXCL-8, and CXCL-10) induced by PDCoV. Western blot analysis revealed that CEP could inhibit viral replication by inducing autophagy. In conclusion, our results suggest that the anti-PDCoV activity of CEP is not only relies on competing the virus binding with pAPN, but also affects the proliferation of the virus in vitro by downregulating the excessive immune response caused by the virus and inducing autophagy. CEP emerges as a promising candidate for potential anti-PDCoV therapeutic development.

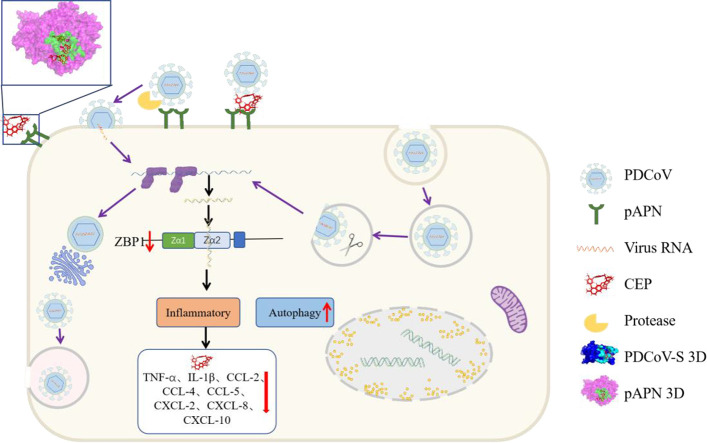

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) is an emerging porcine viral diarrhea pathogen that has the potential to infect humans thus attracting lot of attention (Lednicky et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020b). PDCoV is a member of the family Coronaviridae, the disease caused by PDCoV infection is characterized by vomiting, diarrhea, diarrhea, dehydration, and death in sows and piglets (Zhao et al., 2019). PDCoV in pigs was first detected in 2012 in Hong Kong, China (Lednicky et al., 2021), and has swept through many countries in the Americas and Asia, leading to adverse impacts and economic losses in the global pig industry. Vaccines remain the most effective means to control coronavirus infections. However, there are no specific treatments or effective vaccines against PDCoV infection. New strategies should be developed to address the current difficulties concerning the prevention and treatment of PDCoV.

Cepharanthine (CEP) is an alkaloid extracted from a traditional Chinese herb, has been used as a medicine to treat patients with leukopenia, alopecia areata, and alopecia pityrodes. In recent years, researchers have found that CEP has pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antiparasitic effects. Moreover, there is growing evidence that CEP has antiviral effects against various viruses (SARS, MERS-CoV, HIV, HSV-1, DENV, and Ebola virus) and exhibits immunomodulatory effects (Bailly, 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Matsuda et al., 2014; Phumesin et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2021). However, the efficacy of CEP and the mechanism by which it can inhibit PDCoV infection are still unknown.

Aminopeptidase N (APN)/CD13 is a metalloproteinase with multiple functions, including peptide metabolism, cell adhesion, and cholesterol uptake, which is widely located in the small intestinal epithelial cell membrane of many species (Lu et al., 2020). APN has been identified as a receptor for several coronaviruses, such as TGEV, HCoV-229E, FCoV, CCoV, and PDCoV (Li, 2015; Li et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2010; Tusell et al., 2007). Viral binding to target cells usually occurs by direct attachment of viral glycoproteins to receptors expressed on target cells (Morizono et al., 2011). The binding affinity between the receptor and the viral protein affects the efficiency of viral infection in target cells (Morizono et al., 2011). A previous study reported a significant reduction of symptoms in COVID-19 patients administered an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (Yan et al., 2021). The mutation of key residues on APN significantly affects the infection efficiency of PDCoV (Ji et al., 2022). Therefore, inhibiting the virus from binding to cell receptors and entering cells is essential to inhibit viral infection.

The innate immune response is the host first line of defense following viral infection, however, some viruses can induce exaggerated inflammation (Konopka et al., 2009); for example, influenza A virus, SARS-CoV-2 and dengue virus (Keshavarz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021). Z-DNA-binding protein 1 (ZBP1), with two Zα domains, is an emerging viral Z-RNA innate immune sensor that is involved in cellular innate immunity and inflammatory cell death during viral infection. ZBP1 in the infected nucleus is activated by Z-RNA, such as Influenza A virus (IAV), Influenza B virus (IBV), and SARS-CoV-2 (Koehler et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2020c), to induce cell inflammation and death. It's still unclear whether PDCoV produces Z-RNAs and whether ZBP1 activation by the Z-RNA conformation plays a role in triggering pathogenesis.

Autophagy is a cellular physiological pathway that engulfs its own cytoplasmic proteins or organelles to form autophagosomes. Autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes to form autophagylysosomes, which remove damaged cellular components and serve as a defense mechanism to protect the host from viral infection (Yordy and Iwasaki, 2011). Studies have shown that rapamycin limits PEDV, MERS-CoV and TGEV infection by inducing autophagy (Guo et al., 2016; Kindrachuk et al., 2015; Ko et al., 2017), and cinchonine-induced autophagy can inhibit PEDV infection (Ren et al., 2022). These results suggest that autophagy inducers can inhibit viral infection by inducing autophagy (Ren et al., 2022). CEP is a naturally occurring isoquinoline alkaloid that promotes autophagy (Gao et al., 2017; Law et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2021); however, the role of autophagy activation in limiting PDCoV remains unknown.

In this study, we evaluated the anti-PDCoV capacity of CEP in vitro and further explored the molecular basis of its role. We found that CEP has high anti-PDCoV activity, and this activity is mainly based on blocking virus entry and replication. Interestingly, when the cells were preincubated with CEP prior to PDCoV infection, a significant inhibitory effect on infection efficiency was observed compared with preincubation with virus prior to PDCoV infection.

In conclusion, our results indicate that viral infection was inhibited by hydrogen bonding of CEP to APN conserved regions (the PDCoV RBD binding site) rather than inhibition of APN expression. In addition, CEP could inhibit PDCoV replication by inducing cellular autophagy and reducing inflammatory signaling and necrosis caused by PDCoV. These data provide evidence that CEP is highly effective against PDCoV infection, which potentially suggests the possibility of exploiting CEP as a novel antiviral agent.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines, chemicals, and viruses

Porcine kidney cells (LLC-PK1) and swine testicle cells (ST) and LR7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Natocor, Cordoba, ARG), penicillin (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 U/ml) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere incubator with 5 % CO2. CEP was purchased from MedChemExpress (New Jersey, USA) and dissolved in DMSO as 10 mM. PDCoV-GFP was constructed by the deletion of NS6 and NS7 genes and the insertion of GFP genes in the PDCoV genome (GenBank: MF095123.1) (Zhang et al., 2020b). PDCoV strain CHN—HG-2017 (GenBank MF095123.1) was isolated and preserved in our laboratory. TGEV strain WH-1 and MHV-A59 were preserved in our laboratory.

2.2. Cell counting Kit-8 assay (CCK-8)

Cell activity was evaluated using the Cell Counting Kit (CCK8, Sigma). Briefly, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates for 24 h (5000 cells/well). The cells were treated with DMEM or DMEM-diluted CEP with different concentration gradients for 48 h, and then washed with PBS three times. Ten microliters of CCK8 was added to the wells (blank well without cells, control and experimental wells with cells) and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h before measurement. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm in an Envision II. Cell proliferation inhibition rate = (1—absorbance value of treated experimental group / absorbance value of untreated control group) × 100 %. The CC50 value of CEP were statistically analyzed through the non-linear regression analysis of the data using the GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.3. Quantitative reverse transcription‐PCR (RT‐qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using Tripure Isolation Reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and RNA was converted to cDNA using PrimescriptTM RT Master mix (Takara, Shiga, Japan) following the manufacturer's instructions. PDCoV gene transcription was detected using a real-time PCR assay (RT-PCR), and the sequences of PDCoV, GAPDH, and probe primers used for qPCR were as follows: PDCoV N protein-encoding gene Forward primer: 5′-ATCGACCACATGGCTCCAA-3′; Reverse primer: 5′-CAGCTCTTGCCCATGTAGCTT-3′; and PDCoV taq-Man probe: FAM-CACACCAGTCGTTAAGCATGGCAAGCT-TAMRA. Primers employed for the RT-PCR were as follows: GAPDH-F: 5′-CAGCCTCAAGATCGTCAGCA-3′; and GAPDH-R: 5′-CGTGGACTGTGGTCATGAGT-3′. Ct values were analyzed. All values were normalized to the values obtained for GAPDH for the same sample to correct differences in cell number.

2.4. Tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay

After 24 h of PDCoV challenge, porcine cells were homogenized in DMEM and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the cell supernatants were collected. The cell supernatant sample was serially diluted 1:10 before it was added to confluent LLC-PK1 cells in 96-well plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 and observed for 3–5 days. PDCoV titration was calculated by tissue culture infectious dose 50 (TCID50) following the Reed-Muench method established by Reed and Muench (1938).

2.5. Western blot

LLC-PK1 cells were cultured in 6-well plates and infected with PDCoV with or without CEP for 24 h. Then, the cells were washed gently with PBS and lysed with lysis buffer containing 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and then loading buffer was added. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted onto polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked with milk (5 %) in 0.2 % to 0.4 % TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were probed with specific primary antibodies for 1 h and then incubated with the corresponding HRP-labeled secondary antibody for 45 min at room temperature. After washing thrice, the membranes were visualized using an ECL detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.6. Flow cytometry

LLC-PK1 cells were digested with pancreatic enzymes and washed with PBS containing 2 % FBS. Cells were then fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 15 min. The infected cells were washed and analyzed with BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

2.7. Molecular docking

AUTODOCK 4.2.6 was used for molecular docking analysis of porcine aminopeptidase N ectodomain (pAPN) protein and CEP, supporting the calculation of atomic affinity potential energy (Morris et al., 2009). The chemical structures of CEP (GSNO; CID_10,206) were originally retrieved from a PubChem compound search. The X-ray structure of pAPN (PDB No. 5Z65) and the spike receptor binding domain of porcine respiratory coronavirus in complex with the pig aminopeptidase N ectodomain (PDB No. 4F5C) was prepared using Protein Preparation Wizard and Maestro 9.3 (Schrödinger, USA). The composite structure of the spike receptor binding domain of porcine respiratory coronavirus and pAPN (PDB No. 4F5C) was used as a predicate to investigate whether CEP affects the binding ability of S protein and pAPN.

2.8. Surface plasmon resonance assay (SPR)

The surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay was performed using the ProteOn XPR36 instrument (Bio-Rad). The pAPN proteins were immobilized in a Sensor Chip CM5 according to the manufacturer's instructions. To determine the binding affinity of pAPN, a series of CEP concentrations were run over the surface of the chip at room temperature with a constant flow rate of 30 μL/min in PBS buffer (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 and 0.005 % Tween 20). The dissociation constant (Kd) was analyzed using the ProteOn Manager 3.1 software program by using the steady-state affinity model.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All the experiments were repeated at least three times independently. Mean values and standard errors were calculated for all data using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and SPSS Version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A t-test or one-way analysis of variance was used to assess differences between groups, where a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

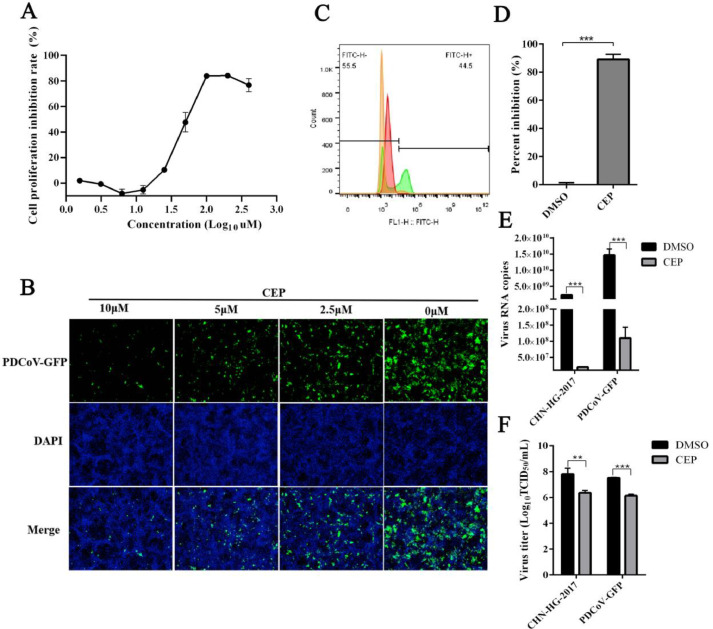

3.1. Cepharanthine inhibits PDCoV infection in LLC-PK1 cells

The cytotoxicity of CEP on the LLC-PK1 cell line was analyzed using the CCK8 assay. The CC50 value of CEP was 17 μM (Fig. 1A). To determine the inhibitory effect of CEP, Fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometric analysis were used to detect the effect of CEP on cells infected with PDCoV. As shown in Fig. 1B, as the concentration of CEP increases, the effect of PDCoV gradually decreases, and at 10 μM, only faint fluorescence was observed. Compared with DMSO control, PDCoV-infected cells were also significantly reduced by CEP (10 μM) in Fig. 1C and D. To further demonstrate and quantify the inhibitory effect of CEP on PDCoV-GFP and PDCoV strain CHN—HG-2017, the supernatant of PDCoV-infected cells was analyzed by qPCR and TCID50. Fig. 1E shows that PDCoV-GFP and PDCoV strain CHN—HG-2017 proliferation was significantly inhibited by CEP at concentration of 10 µM. The TCID50 results shown in Fig. 1F demonstrate that CEP reduced viral titers by a factor of 32. These results strongly suggest that CEP can inhibit PDCoV-GFP and PDCoV strain CHN—HG-2017 infection in LLC-PK1 cells at safe concentrations and suggest that CEP should be considered for further investigation on its mechanism of action.

Fig. 1.

Antiviral effect of CEP on PDCoV infection.

The effect of CEP on LL-CPK1 cell viability were was detected using the CCK8 assay. (B) The effect of different concentrations of CEP on PDCoV-infected cells determined by Fluorescence microscopy. Green fluorescence represents PDCoV distribution; blue fluorescence represents nuclei from DAPI. (C) Flow cytometric analysis was used to detect infected cells in the presence or absence of CEP with PDCoV (MOI=0.1) for 24 h. (D) Quantitative analysis of the data shown in C. (E-F) The infected LLC-PK1 cells were treated with or without CEP for 24 h, and the viral RNA copies and viral titers in the supernatant were examined by qPCR and TCID50. The shown results are representative of one experiment out of at least three experiments. Error bars represent ±1 SD; ns, no significant difference; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test.

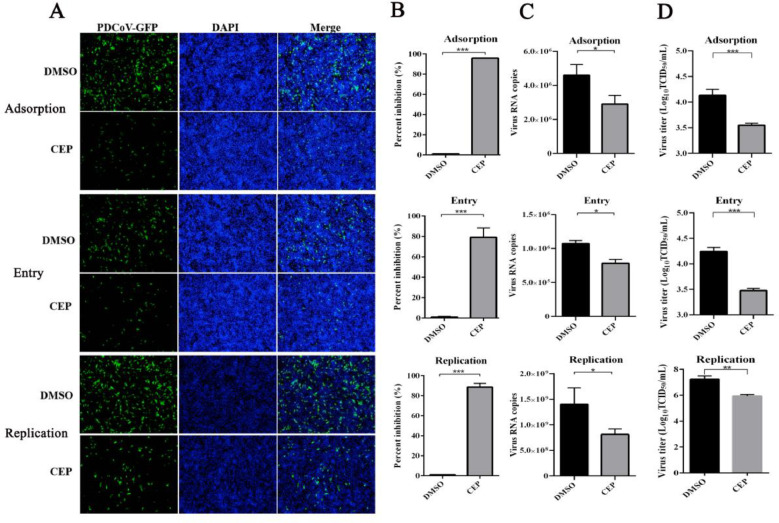

3.2. Effect of CEP on the PDCoV life cycle

To further explore on which stage of the PDCoV life cycle was inhibited by CEP; virus binding, entry, and replication assays were performed during PDCoV infection. First, the precooled cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and placed at 4 °C to allow virus adsorption for 1 h. Then, the unadsorbed virus was removed and replaced by serum-free medium with a concentration of 10 µg/mL trypsin. Detection of attached PDCoV RNA and PDCoV particles were determined by qPCR and TCID50. Importantly, the ratio of PDCoV RNA copy number was significantly decreased (∼2-fold) in LLC-PK1 cells compared with the DMSO group (Fig. 2A), and the adsorbed virus titer was reduced by more than 3.82 times (Fig. 2B). The PDCoV-GFP-infected cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy and evaluated using flow cytometry after 24 h. PDCoV-infected cells were reduced by 90 % in the presence of CEP (Fig. 2C and D), indicating that PDCoV adsorption was significantly reduced by CEP. Second, the precooled cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with PDCoV (MOI=0.1) at 4 °C for 1 h. The cell supernatants were replaced with serum-free medium with a CEP concentration of 1 μM at 37 °C for 15 min. We found that treatment with CEP during the entry of PDCoV into cells can significantly reduced the level of entering viral RNA (∼1.5-fold), viral titer (∼5.8-fold) and infected cells (∼78 %) (Fig. 2A–D). Third, the diluted PDCoV preparation was added to LLC-PK1 cells at 37 °C for 1 h, and the infected cells were washed with PBS and replaced with CEP at a concentration of 10 μM for 8 h. As shown in Figure (2A-D), treatment of PDCoV-infected cells with CEP resulted in significantly reduced viral RNA levels (∼1.7-fold), Virus titer (∼25-fold) and infected cells (∼88 %). Based on these results CEP could significantly inhibit viral binding, entry, and replication in vitro.

Fig. 2.

Effect of CEP on different stages of the PDCoV replication cycle.

The effect of CEP on PDCoV adsorption. CEP and PDCoV (MOI=5) were incubated with precooled cells for 2 h at 4 °C. Cells were washed with cold PBS three times, and cells were continued to grow for 8 h; The effect of CEP on PDCoV entry. Precooled cells were infected with PDCoV for 2 h at 4 °C and incubated with CEP for 1 h at 37 °C after washing with PBS, and cells were continued to grow for 8 h; The effect of CEP on PDCoV replication. Cells were infected with PDCoV for 1 h at 37 °C after washing with PBS, and cells were continued to grow with CEP for 8 h at 37 °C. PDCoV-infected cells were analyzed using Fluorescence microscopy (A) and flow cytometric analysis (B). (C) Viral RNA was extracted for qPCR quantification. (D) Viral titers in the supernatant were examined by TCID50. DMSO was added as the positive control. The experiments were repeated at least three times. Error bars represent ±SD; ns, no significant difference; ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test.

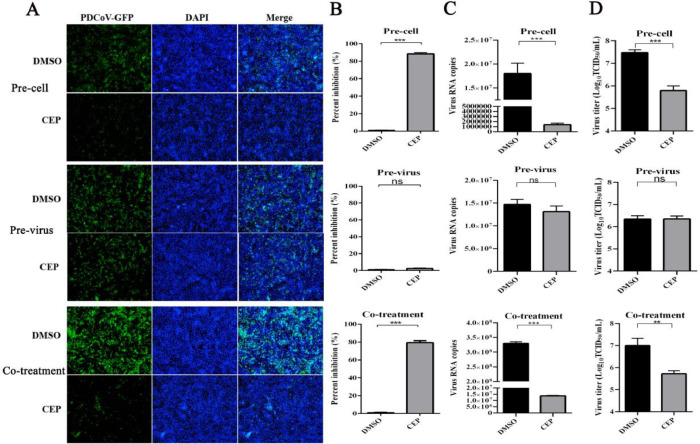

3.3. CEP indirectly inhibits viral proliferation by acting on cells

Inhibition of PDCoV entry indicates that CEP acts at the stage preceding viral entry into target cells by acting on target cells, cell-free virions, or the cell-virus interaction process to exert antiviral activity. To determine whether the antiviral effect of CEP acts on cells or viruses, cells were infected with PDCoV under 3 different conditions. Pre-treatment: LLC-PK1 cells were pretreated with CEP (10 μM) for 8 h and incubated with PDCoV-GFP for 1 h to allow virus adsorption. The results showed that viral RNA levels in preexposed CEP-treated cells were decreased significantly compared to those in untreated cells (Fig. 3). Pre-exposure assay: The virus was incubated with CEP at 37 °C for 1 h, and the mixtures containing the virus and CEP were diluted 1000 times with serum-free culture medium and then added to the cells at 37 °C for 1 h to allow attachment. The unbound virus was removed with PBS. Infection with pretreatment CEP virus had no significant effect on virus growth in cells or the yield of progeny virus (Fig. 3). Co-treatment: Cells were infected with CEP and virus and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The unbound viruses were removed, and replaced with fresh culture medium for 8 h. As shown in Fig. 3, CEP treatment at 10 μM significantly inhibited PDCoV in pre- and co-treatment assays. Notably, CEP could not inhibit PDCoV infection in the pre-exposure assay as shown in Fig 3. The cell-dependent antiviral activity of CEP suggested that CEP likely acts on the host cell and not the virus itself. At the same time, we added experiments in which the virus and drug were incubated in cells for 15 min, 30 min, 45 min and 1 h respectively, and the results showed that the longer the exposure time of CEP, the more obvious the effect of CEP on inhibiting PDCoV entry into cells (supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

CEP indirectly inhibits viral proliferation by acting on cells.

Cell pretreatment (Pre-cell): Cells were preincubated with CEP for 2 h at 37 °C and washed with PBS three times. The preincubated cells were infected with PDCoV at an MOI of 1 for 1 h; Virus pretreatment (Pre-virus): PDCoV was preincubated with CEP for 2 h at 37 °C and then diluted 1000 times and incubated with LLC-PK1 cells for 1 h; Co-treatment: PDCoV and CEP were simultaneously added to LLC-PK1 cells for 1 h. The unbound virus was washed away with PBS, and the cells were cultured at 37 °C for 8 h in fresh medium. (A-B) PDCoV infection was observed by fluorescence staining and analysed by flow cytometric analysis. (C) The RNAs levels of PDCoV in the culture supernatants were extracted and measured by qPCR. (D) Viral titers in the culture supernatants were calculated by TCID50. DMSO was added as the positive control. The data are representative of mean values from three independent experiments. Error bars represent±SD; ns, no significant difference; ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test.

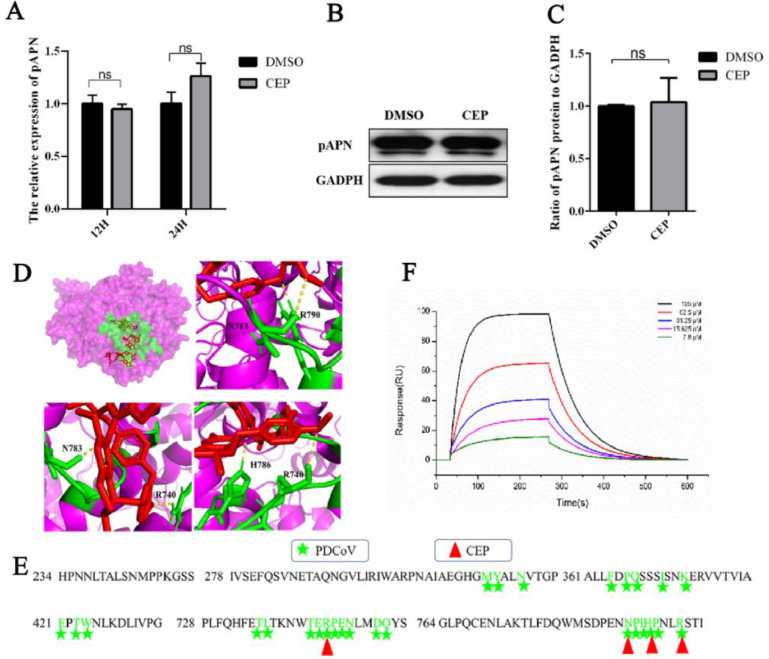

3.4. CEP does not affect the expression of pAPN but binds to the binding site of PDCoV and pAPN

Previous studies have shown that CEP acts on host cells to interfere with viral infection by affecting the expression of the viral receptor ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) (Chitsike et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021). In our study, we found that CEP interfered with PDCoV infection by acting on the host cell rather than the virus. We investigated whether CEP affects virus invasion by affecting the expression and activity of APN, which has been reported as an entry receptor for PDCoV (Li et al., 2018). We detected the RNA expression levels and protein expression levels of APN in CEP-incubated cells. The RT‒PCR and WB results showed that pAPN mRNA and protein expression levels were not significantly altered by CEP treatment (Fig. 4A–C). Hence, we molecularly docked CEP with the main target protein pAPN. There were 50 binding modes between CEP and APN, among which there were 23 binding modes of residues on pAPN that were in contact with PDCoV RBD, with binding energy rangeing from −9.75 to −6.87 and the binding constant range was 1.17 to 795.6 (Supplementary Table 1). CEP forms hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues (R740, N783, and R790) in the APN binding region of the PDCoV RBD, which mainly consists of the interaction between the β5 and β6 hairpins of the PDCoV RBD and the α19-α20 and α21-α22 loops of APN (Peng, et al., 2022)(Fig. 4D and E). These findings indicate that there is a strong affinity between CEP and pAPN. To demonstrate whether CEP binds directly to pAPN to compete with PDCoV; SPR assays were used to examine the molecular interaction between CEP and pAPN. The dissociation constant (the value of KdEGCG) was 88.7 µM (Fig. 4F). The results showed that CEP exhibited moderate binding affinity for pAPN, which could explain the significant inhibitory effect of CEP on PDCoV infection in vitro.

Fig. 4.

Effect of CEP on the relative expression of the pAPN gene.

(A) The relative gene expression level of pAPN in CEP-incubated cells was determined by RT‒PCR. (B) Verification of pAPN receptor expression in CEP-incubated cells by WB. (C) Quantitative analysis of the data shown in B. DMSO was added as the positive control. (D) The upper left of picture: Overlay of PDCoV footprints on pAPN. pAPN is shown as a surface representation, colored in pink. Residues on pAPN contacting the PDCoV RBD are colored green. The lower left and right of three picture: Atomic details of the interaction between pAPN RBD and CEP. Contacting residues on proteins are represented as sticks, with nitrogen and oxygen atoms colored green. CEP is represented as sticks colored in red. (E) Sequence alignment of pAPN. Residues on pAPN binding to PDCoV RBD are marked in green according to the code of the key above the sequences. The amino acids of PAPN that bind to CEP are marked by red triangles. (F) Analysis of the binding of pAPN and CEP using surface plasmon resonance (SPR).The experiments were repeated at least three times. Error bars represent ±SD; ns, no significant difference; ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test.

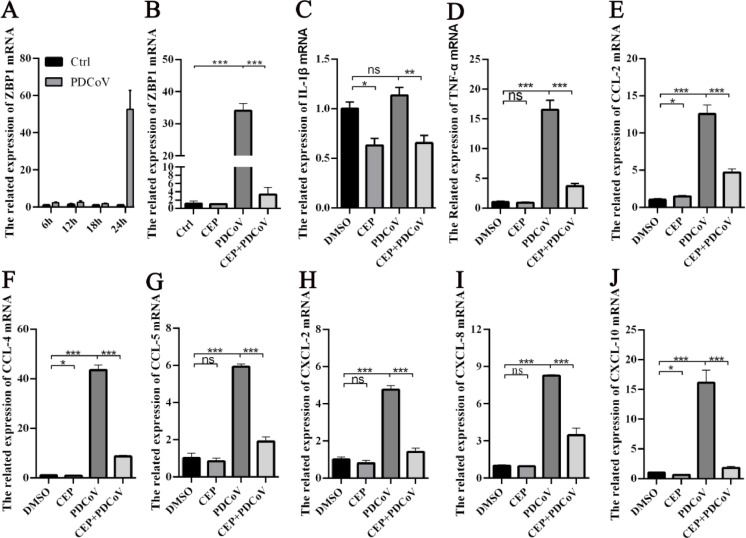

3.5. CEP reduces inflammatory signaling caused by PDCoV infection

Z-DNA-binding protein 1 (ZBP1), an emerging viral Z-RNA innate immune sensor, regulates programmed cell death pathways and host defense responses during viral infection (Kuriakose and Kanneganti, 2018). The Z-RNA of many viruses can induce the activation of ZBP1. Therefore, we used RT-PCR to measure the level of ZBP1 mRNA expression in PDCoV-infected cells at different times. We found that the expression levels of ZBP1 increased with increasing PDCoV infection time, peaking after 24 h (Fig. 5A). In addition, we found that the expression level of ZBP1 in PDCoV cells infected with 12.5 µM CEP was significantly lower than that in the cells without CEP (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that CEP could reduce the expression of ZBP1 induced by PDCoV. Viral infection induces the release of cytokines, which may contribute to its pathogenesis. PDCoV infection has been shown to induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) and chemokines (CCL-2, CCL-4, CCL-5, CXCL-2, CXCL-8, and CXCL-10) in vivo and in vitro. Therefore, we used RT‒qPCR to determine whether treatment of LLC-PK1 cells with CEP altered PDCoV infection-induced proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The results showed that CEP significantly decreased the expression of PDCoV-induced proinflammatory factors (IL-1β and TNF-α) and chemokines (CCL-2, CCL-4, CCL-5, CXCL-2, CXCL-8, and CXCL-10)(Fig. 5C–J). These data indicate that CEP can potentially modulate immune responses in PDCoV-infected cells by reducing cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression.

Fig. 5.

CEP reduces inflammatory signaling and necrosis caused by PDCoV infection.

The transcription level of ZBP1 in PDCoV-infected cells was determined by RT-qPCR after 6 h, 12 h, 18 h and 24 h, respectively. (B-J) LLC-PK1 cells were inoculated with DMSO or CEP and mock-infected or infected with PDCoV (MOI=) for 24 h. The total RNA of PDCoV-infected cells was harvested, and the relative mRNA levels of the ZBP1 and indicated cytokine (IL-1β and IFN-α) and chemokine genes (CCL-2, CCL-4, CCL-5, CXCL-2, CXCL-8, and CXCL-10) were measured by RT‒qPCR. For quantitative RT‒PCR analysis, β-actin mRNA was used as an internal control. The experiments were repeated at least three times. Error bars represent ±SD; ns, no significant difference; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001, ***p< 0.001 by Student's t-test.

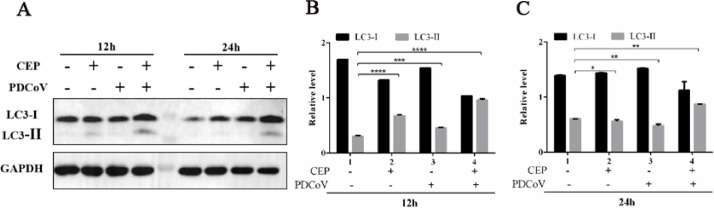

3.6. CEP inhibits PDCoV infection in LLC-PK1 cells by inducing autophagy

Based on the above findings which demonstrated that CEP could significantly reduce PEDV replication in LLC-PK1 cells, we investigated the antiviral mechanism by which CEP inhibits PDCoV infection. It has been reported that rapamycin could inhibit PEDV infection in porcine intestinal epithelial cells by inducing autophagy (Ko et al., 2017), and cinchonine can induce autophagy to inhibit porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (Ren et al., 2022). Therefore, we hypothesized that the inhibitory effects of CEP on PDCoV infection rely on autophagy. We monitored autophagy by detecting the expression of LC3-II and the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II protein, which is an autophagosome marker protein, involved in the formation of vesicles in autophagic body fluids. LLC-PK1 cells were incubated with DMSO, CEP, PDCoV, or CEP and PDCoV for 12 h, and western blotting was performed using antibodies against LC3-I, LC3-II, or GAPDH. The results showed that LC3-II protein levels were significantly increased in the CEP group compared with the DMSO group and in the CEP and PDCoV groups compared with the PDCoV group, and the conversion rate from LC3-I to LC3-II was also significantly increased (Fig. 6A-C). These findings suggest that CEP may regulate intracellular autophagy in LLC-PK1 cells to inhibit viral replication.

Fig. 6.

CEP inhibits PDCoV infection in LLC-PK1 cells by inducing autophagy.

CEP inhibits PDCoV infection by inducing autophagy, as determined by Western blot analysis. LLC-PK1 cells were incubated with DMSO or CEP and mock-infected or infected with PDCoV at an MOI of 1. The cells were further maintained in the presence of DMSO or CEP and fixed at 12 h of virus infection. Cellular lysates and viral lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting using an antibody against LC3-I, LC3-II, or GAPDH. (B-C) The expression levels of each protein were quantitatively analysed by densitometry and expressed as density values relative to the GAPDH gene, and multiples of changes in the GAPDH ratio for each protein were plotted. Data indicate the representative mean values from three independent experiments, and error bars represent ±SD; ns, no significant difference; ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test.

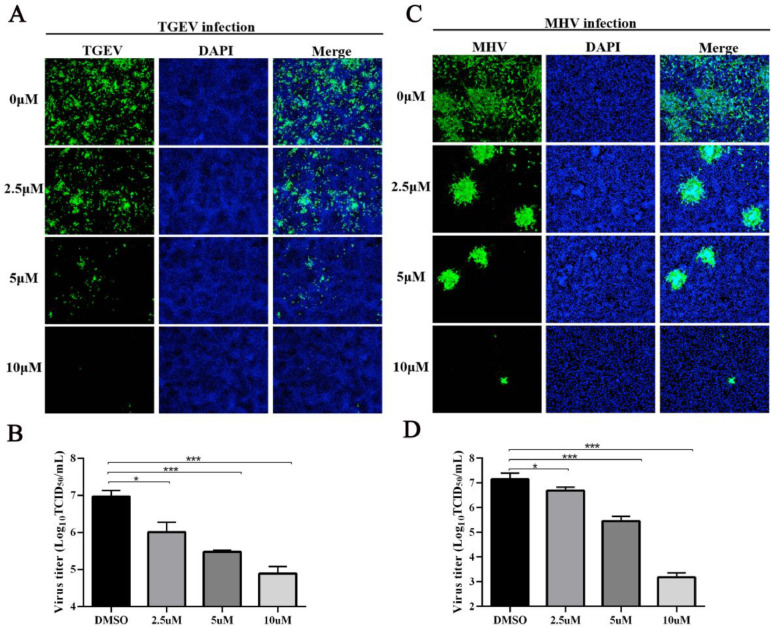

3.7. CEP confers broad-spectrum resistance to other coronaviruses (TGEV and MHV)

The above results demonstrated the inhibitory effect of CEP on PDCoV (δ-CoV) replication. Hence, to explore whether CEP has a broad antiviral spectrum against other coronaviruses; the antiviral activity of CEP on the replication of TGEV (α-CoV) and MHV (β-CoV) was tested by IFA and TCID50. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, the IFA results intuitively showed that CEP could effectively inhibit the propagation of TGEV and MHV. The TCID50 results also revealed that CEP could significantly reduce the virus titers of TGEV and MHV (Fig. 7C and D). These results hint at the broad-spectrum antiviral efficacy of CEP-based therapeutics against other coronaviruses.

Fig. 7.

CEP Confers Broad-Spectrum Resistance to other coronaviruses (TGEV and MHV).

LLC-PK1 cells were incubated with TGEV in the presence or absence of CEP for 24 h. The propagation of TGEV in porcine testis cells was observed by IFA (A), and the virus titer was measured in ST cells by TCID50 assay (B). LR7 cells were infected with MHV in the presence or absence of CEP for 24 h, MHV in cells was observed by immunofluorescence microscopy (C), and viral titers in cell supernatant were examined by TCID50 (D). The results are representative of one of at least three experiments. Error bars represent ±1 SD; ns, no significant difference; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test.

4. Discussion

Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) is a novel pathogen in the intestinal tract of pigs that can cause acute diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration in newborn piglets (Xu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020a). Since PDCoV was first detected in Hong Kong in 2012, it has spread to the United States, South Korea, mainland China, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, and other countries, and it has caused enormous economic losses to the global pork industry. Therefore, the development of an effective vaccine is essential for the prevention and control of PDCoV. However, there is currently no effective vaccine against PDCoV (Tang et al., 2021). Flavonoids, phenols, alcohols, and alkaloids in Chinese herbal extracts have attracted much attention and have been extensively studied in the new antiviral research (Sun et al., 2023). Diammonium glycyrrhizate (DG) has been reported to inhibit viral attachment and early replication in LLC-PK1 cells (Zhai et al., 2019). Curcumin inhibits the expression of PDCoV-induced inflammatory factors by inhibiting the RIG-I pathway and the expression of NF-κB protein, thereby inhibiting the replication of PDCoV (Wang et al., 2023). Ergosterol peroxide inhibits autophagy induced by PDCoV to inhibit viral replication through the p38 signaling pathway (Duan et al., 2021). However, inhibition of PDCoV infection by drugs has not been documented. In this study, we found that the alkaloids of Cephaloid from Lyceum japonica had effective anti-PDCoV properties in LLC-PK1 and ST cells, and CEP had antiviral activity against another TGEV, MHV, by reducing replication in ST and LR7 cells. By conducting add-on time experiments, we determined the cellular targets of the drug and the stage of the targeted virus's life cycle. We found that this CEP reduced the number of viral RNA copies in the cell supernatant by acting on the host during the PDCoV infection and replication phase.

The first step in the coronavirus replication cycle is the attachment between the viral spike protein (S protein) and the host. Prevention of viral infection can inhibit viral infectivity, which is one of the most attractive antiviral strategies in past antiviral drug research, where viral receptors and spike proteins (S proteins) are important targets. In this study, we found that CEP inhibited PDCoV attachment and entry to the cell surface by acting on host cells, suggesting that CEP may target viral receptors. Previous studies have reported that CEP could stably bind to ACE2, the receptor of SARS-CoV, and reduce the expression level of ACE2, thus interfering with virus-cell binding (Fan et al., 2022). Porcine APN is the only major identified cell-entry receptor for PDCoV (Li et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). CEP may affect the expression and activity of APN. Based on docking analysis, we found that CEP could interact with APN amino acids R740, N783, and R790 to form hydrogen bonds. According to relevant studies, there are two PDCoV RBD interaction regions in pAPN: the first region is the DII of pAPN (α2 helix (M315-Y316-N319), α5 helix (F364-P366-Q367-I371-K374) and α6-α7 ring (E-421-T423-W424)), and the second region involves the DIV of pAPN (α19-α20 ring (T738-R739-P740-E741-N742) and α21-α22 ring (N783-P784-I785-H786-P787-R790)) (Ji et al., 2022). Therefore, CEP has the potential to inhibit pAPN activity by binding the PDCoV RBD binding region of pAPN. We used SPR to confirm that there was a moderate binding affinity between CEP and pAPN, while WB results showed that CEP did not affect the mRNA and protein levels of pAPN.

Inhibiting the excessive inflammatory response caused by viral infection can affect the replication of the virus, which is also one of the attractive antiviral strategies in antiviral drug research. The innate immune response, the first line of host defense following viral infection, is usually activated, resulting in the production of interferons and proinflammatory cytokines, but their overrelease may mediate immunopathological symptoms (Konopka et al., 2009). For example, acute injury of respiratory epithelial cells caused by influenza A virus, SARS-CoV-2, and SARS-CoV viruses is closely related to an abnormal increase in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Keshavarz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021). Z-DNA-binding protein 1 (ZBP1), an emerging viral Z-RNA innate immune sensor, regulates programmed cell death pathways and host defense responses during viral infection (Kuriakose and Kanneganti, 2018). In this study, infection with PDCoV significantly activated ZBP1 expression in cells, which promoted cytokine (IL-1β, IFN-α) and chemokine gene (CCL-2, CCL-4, CCL-5, CXCL-2, CXCL-8, and CXCL-10) secretion. CPE treatment inhibited ZBP1 activation and decreased the mRNA expression of these cytokines. In addition, there is substantial evidence that ZBP1 is involved in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. For example, the activation of ZBP1 in the nucleus activated by influenza infection mediates the activation of MLKL to drive necrotic apoptosis caused by pathological inflammation (Zhang et al., 2020c). SARS-CoV-2 infection forms viral Z-RNA, activates the ZBP1-RIPK3 pathway, and promotes virus-induced inflammatory responses (Li et al., 2023). In addition, ZBP1 acts as a receptor for viral RNA (vRNA), triggering the cell death pathway mainly through necrotic apoptosis and the inflammatory response. Here, we demonstrated that CEP reduced the expression of ZBP1 induced by PDCoV infection to trigger an inflammatory response, but whether CEP inhibits cell death by inhibiting the expression of ZBP1 protein needs further investigations.

In recent years, targeting autophagy has also become a very popular and promising method of inhibiting viral replication, and several drugs have been shown to induce autophagy (Gao et al., 2017; Law et al., 2014). Autophagy has been extensively studied not only for its protective role in cell survival under stress but also in pathogen infection (Pei et al., 2014). Viruses have developed various strategies to block autophagy or use autophagy for their own benefit; on the other hand, host cells use autophagy as a defense mechanism to inhibit viral replication or deliver the virus to the lysosomal compartment for elimination (Ko et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2022). It has been reported that each coronavirus may interact with the autophagy pathway and its components in its own unique way. For example, nsp6 of IBV, MHV,and SARS-CoV induce typical autophagy pathways, and viral replication complexes are commonly associated with these structures (Cottam et al., 2011, 2014). Chloroquine and its derivatives, which inhibit the autophagy pathway, have been proposed as a treatment for COVID-19. However, rapamycin-induced autophagy can inhibit the infection of MERS-CoV, TGEV, and PEDV (Guo et al., 2016; Kindrachuk et al., 2015; Ko et al., 2017), and cinchonine-induced autophagy can inhibit PEDV replication in Vero and LLC-PK1 cells (Ren et al., 2022). In this study, we found that autophagy induced by CEP inhibited the replication of PDCoV in LLC-PK1 cells.

Taken together, our findings suggest that CEP could inhibit PDCoV infection in vitro by targeting multiple phases of the PDCoV life cycle, including the attachment, entry, and postinfection phases. In addition, CEP indirectly inhibited cytopathic effects caused by PDCoV infection through pAPN binding, which is a receptor for PDCoV. In addition, CEP inhibited PDCoV-induced cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1β, IFN-α CCL-2, CCL-4, CCL-5, CXCL-2, CXCL-8, and CXCL-10, and inhibits ZBP1 induced by PDCoV infection. At the same time, CPE significantly inhibited autophagy in PDCoV infection. Therefore, the antiviral and immunomodulatory capacity of CEP against PDCoV could be attributed to the inhibition of ZBP1 and the induction of autophagy. These results provide new strategies for the development of novel antiviral drugs.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yumei Sun: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Zhongzhu Liu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Shiyi Shen: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Mengjia Zhang: Writing – review & editing. Lina Liu: Writing – review & editing. Ahmed H Ghonaim: Writing – review & editing. Yongtao Li: Writing – review & editing. Shujun Zhang: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision. Wentao Li: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32272990, 31872328), the Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Province ([2020]4Y217), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2662023DKPY004).

Schematic illustration of the mechanism by which CEP inhibits PDCoV infection

As a small molecule compound, the anti-PDCoV activity of CEP is through competition with the virus to bind the porcine aminopeptidase N (pAPN) protein on the cell, which is a receptor for PDCoV and prevents the virus from attaching and entering the host cell. At the same time, it also affects the proliferation of the virus in vitro by down-regulating the excessive immune response caused by the virus and inducing autophagy. CEP as a potential candidate for the development of PDCoV therapy.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2023.199303.

Contributor Information

Shujun Zhang, Email: sjxiaozhang@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Wentao Li, Email: wentao@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bailly C. Cepharanthine: an update of its mode of action, pharmacological properties and medical applications. Phytomedicine. 2019;62 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitsike L., Krstenansky J., Duerksen-Hughes P.J. Advances in Pharmacological and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2021. 2021. ACE2: S1 RBD interaction-targeted peptides and small molecules as potential COVID-19 therapeutics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottam E.M., Maier H.J., Manifava M., Vaux L.C., Chandra-Schoenfelder P., Gerner W., Britton P., Ktistakis N.T., Wileman T. Coronavirus NSP6 proteins generate autophagosomes from the endoplasmic reticulum via an omegasome intermediate. Autophagy. 2011;7:1335–1347. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.11.16642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottam E.M., Whelband M.C., Wileman T. Coronavirus NSP6 restricts autophagosome expansion. Autophagy. 2014;10:1426–1441. doi: 10.4161/auto.29309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan C., Ge X., Wang J., Wei Z., Feng W.H., Wang J. Ergosterol peroxide exhibits antiviral and immunomodulatory abilities against porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) via suppression of NF-kappaB and p38/MAPK signaling pathways in vitro. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021;93 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H., He S.T., Han P., Hong B., Liu K., Li M., Wang S., Tong Y. Cepharanthine: A Promising Old Drug against SARS-CoV-2. Adv. Biol. (Weinh) 2022;6(12) doi: 10.1002/adbi.202200148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S., Li X., Ding X., Qi W., Yang Q. Apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017;41:1633–1648. doi: 10.1159/000471234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Yu H., Gu W., Luo X., Li R., Zhang J., Xu Y., Yang L., Shen N., Feng L., Wang Y. Autophagy negatively regulates transmissible gastroenteritis virus replication. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23864. doi: 10.1038/srep23864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W., Peng Q., Fang X., Li Z., Li Y., Xu C., Zhao S., Li J., Chen R., Mo G., Wei Z., Xu Y., Li B., Zhang S. Structures of a deltacoronavirus spike protein bound to porcine and human receptors. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1467. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29062-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz M., Namdari H., Farahmand M., Mehrbod P., Mokhtari-Azad T., Rezaei F. Association of polymorphisms in inflammatory cytokines encoding genes with severe cases of influenza A/H1N1 and B in an Iranian population. Virol. J. 2019;16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1187-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S., Shafiei M.S., Longoria C., Schoggins J.W., Savani R.C., Zaki H. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces inflammation via TLR2-dependent activation of the NF-kappaB pathway. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.68563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Min J., Jang M., Lee J., Shin Y., Park C., Song J., Kim H., Kim S., Jin Y.H., Kwon S. Natural bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloids-tetrandrine, fangchinoline, and cepharanthine, inhibit human coronavirus OC43 infection of MRC-5 human lung cells. Biomolecules. 2019;9:696. doi: 10.3390/biom9110696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindrachuk J., Ork B., Hart B.J., Mazur S., Holbrook M.R., Frieman M.B., Traynor D., Johnson R.F., Dyall J., Kuhn J.H., Olinger G.G., Hensley L.E., Jahrling P.B. Antiviral potential of ERK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling modulation for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection as identified by temporal kinome analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1088–1099. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03659-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko S., Gu M.J., Kim C.G., Kye Y.C., Lim Y., Lee J.E., Park B.C., Chu H., Han S.H., Yun C.H. Rapamycin-induced autophagy restricts porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infectivity in porcine intestinal epithelial cells. Antiviral Res. 2017;146:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler H., Cotsmire S., Zhang T., Balachandran S., Upton J.W., Langland J., Kalman D., Jacobs B.L., Mocarski E.S. Vaccinia virus E3 prevents sensing of Z-RNA to block ZBP1-dependent necroptosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:1266–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.05.009. e1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka J.L., Thompson J.M., Whitmore A.C., Webb D.L., Johnston R.E. Acute infection with venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particles catalyzes a systemic antiviral state and protects from lethal virus challenge. J. Virol. 2009;83:12432–12442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00564-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose T., Kanneganti T.D. ZBP1: innate sensor regulating cell death and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law B.Y.K., Chan W.K., Xu S.W., Wang J.R., Bai L.P., Liu L., Wong V.K.W. Natural small-molecule enhancers of autophagy induce autophagic cell death in apoptosis-defective cells. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:5510. doi: 10.1038/srep05510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lednicky J.A., Tagliamonte M.S., White S.K., Elbadry M.A., Alam M.M., Stephenson C.J., Bonny T.S., Loeb J.C., Telisma T., Chavannes S., Ostrov D.A., Mavian C., Beau De Rochars V.M., Salemi M., Morris J.G., Jr. Emergence of porcine delta-coronavirus pathogenic infections among children in Haiti through independent zoonoses and convergent evolution. medRxiv: the preprint server for health sciences. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Cho K., Kook H., Kang S., Lee Y., Lee J. The different immune responses by age are due to the ability of the fetal immune system to secrete primal immunoglobulins responding to unexperienced antigens. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022;18:617–636. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.67203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Hulswit R.J.G., Kenney S.P., Widjaja I., Jung K., Alhamo M.A., van Dieren B., van Kuppeveld F.J.M., Saif L.J., Bosch B.J. Broad receptor engagement of an emerging global coronavirus may potentiate its diverse cross-species transmissibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:E5135–E5143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1802879115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Zhang Y., Guan Z., Ye M., Li H., You M., Zhou Z., Zhang C., Zhang F., Lu B., Zhou P., Peng K. SARS-CoV-2 Z-RNA activates the ZBP1-RIPK3 pathway to promote virus-induced inflammatory responses. Cell Res. 2023;33:201–214. doi: 10.1038/s41422-022-00775-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Receptor recognition mechanisms of coronaviruses: a decade of structural studies. J. Virol. 2015;89:1954–1964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02615-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Tang Q., Rao Z., Fang Y., Jiang X., Liu W., Luan F., Zeng N. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus 1 by cepharanthine via promoting cellular autophagy through up-regulation of STING/TBK1/P62 pathway. Antiviral Res. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Amin M.A., Fox D.A. CD13/Aminopeptidase N is a potential therapeutic target for inflammatory disorders. J. Immunol. 2020;204:3–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda K., Hattori S., Komizu Y., Kariya R., Ueoka R., Okada S. Cepharanthine inhibited HIV-1 cell–cell transmission and cell-free infection via modification of cell membrane fluidity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:2115–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morizono K., Xie Y., Olafsen T., Lee B., Dasgupta A., Wu A.M., Chen I.S. The soluble serum protein Gas6 bridges virion envelope phosphatidylserine to the TAM receptor tyrosine kinase Axl to mediate viral entry. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9(4):286–298. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morizono K., Xie Y., Olafsen T., Lee B., Dasgupta A., Wu AM., Chen IS.Y. The soluble serum protein Gas6 bridges virion envelope phosphatidylserine to the TAM receptor tyrosine kinase Axl to mediate viral entry. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:286–298. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J., Zhao M., Ye Z., Gou H., Wang J., Yi L., Dong X., Liu W., Luo Y., Liao M., Chen J. Autophagy enhances the replication of classical swine fever virus in vitro. Autophagy. 2014;10:93–110. doi: 10.4161/auto.26843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phumesin P., Panaampon J., Kariya R., Limjindaporn T., Yenchitsomanus P.T., Okada S. Cepharanthine inhibits dengue virus production and cytokine secretion. Virus Res. 2023;325 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2022.199030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L.J., Muench H. A simple method of estimating 50% endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., Zeng W., Jiang C., Li C., Zhang C., Cao H., Li W., He Q. Inhibition of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus by cinchonine via inducing cellular autophagy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.856711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Li G., Liu B. Binding characterization of determinants in porcine aminopeptidase N, the cellular receptor for transmissible gastroenteritis virus. J. Biotechnol. 2010;150:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Li C., Liu Z., Zeng W., Ahmad M.J., Zhang M., Liu L., Zhang S., Li W., He Q. Chinese herbal extracts with antiviral activity: evaluation, mechanisms, and potential for preventing PRV, PEDV and PRRSV infections. Animal Dis. 2023;3 [Google Scholar]

- Tang P., Cui E., Song Y., Yan R., Wang J. Porcine deltacoronavirus and its prevalence in China: a review of epidemiology, evolution, and vaccine development. Arch. Virol. 2021;166:2975–2988. doi: 10.1007/s00705-021-05226-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusell S.M., Schittone S.A., Holmes K.V. Mutational analysis of aminopeptidase N, a receptor for several group 1 coronaviruses, identifies key determinants of viral host range. J. Virol. 2007;81:1261–1273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01510-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Liu Y., Ji C.M., Yang Y.L., Liang Q.Z., Zhao P., Xu L.D., Lei X.M., Luo W.T., Qin P., Zhou J., Huang Y.W. Porcine deltacoronavirus engages the transmissible gastroenteritis virus functional receptor porcine aminopeptidase N for infectious cellular entry. J. Virol. 2018:92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00318-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wang X., Zhang J., Shan Q., Zhu Y., Xu C., Wang J. Prediction and verification of curcumin as a potential drug for inhibition of PDCoV replication in LLC-PK1 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms24065870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Zhong H., Zhou Q., Du Y., Chen L., Zhang Y., Xue C., Cao Y. A highly pathogenic strain of porcine deltacoronavirus caused watery diarrhea in newborn piglets. Virol. Sin. 2018;33:131–141. doi: 10.1007/s12250-018-0003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M., Dong Y., Bo X., Cheng Y., Cheng J. Large screening identifies ACE2 positively correlates With NF-kappaB signaling activity and targeting NF-kappaB signaling drugs suppress ACE2 levels. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.771555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yordy B., Iwasaki A. Autophagy in the control and pathogenesis of viral infection. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011;1:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai X., Wang S., Zhu M., He W., Pan Z., Su S. Antiviral effect of lithium chloride and diammonium glycyrrhizinate on porcine deltacoronavirus in vitro. Pathogens. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/pathogens8030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Chen J., Liu Y., Da S., Shi H., Zhang X., Liu J., Cao L., Zhu X., Wang X., Ji Z., Feng L. Pathogenicity of porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) strain NH and immunization of pregnant sows with an inactivated PDCoV vaccine protects 5-day-old neonatal piglets from virulent challenge. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020;67:572–583. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Li W., Zhou P., Liu D., Luo R., Jongkaewwattana A., He Q. Genetic manipulation of porcine deltacoronavirus reveals insights into NS6 and NS7 functions: a novel strategy for vaccine design. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:20–31. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1701391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Yin C., Boyd D.F., Quarato G., Ingram J.P., Shubina M., Ragan K.B., Ishizuka T., Crawford J.C., Tummers B., Rodriguez D.A., Xue J., Peri S., Kaiser W.J., Lopez C.B., Xu Y., Upton J.W., Thomas P.G., Green D.R., Balachandran S. Influenza virus Z-RNAs induce ZBP1-mediated necroptosis. Cell. 2020;180:1115–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.050. e1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Huang W., Ren L., Ju X., Gong M., Rao J., Sun L., Li P., Ding Q., Wang J., Zhang Q.C. Comparison of viral RNA–host protein interactomes across pathogenic RNA viruses informs rapid antiviral drug discovery for SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res. 2021;32:9–23. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00581-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Qu H., Hu J., Fu J., Chen R., Li C., Cao S., Wen Y., Wu R., Zhao Q., Yan Q., Wen X., Huang X. Characterization and pathogenicity of the porcine deltacoronavirus isolated in Southwest China. Viruses. 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/v11111074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.