Abstract

Angiogenesis is fundamental to the expansion of the placental vasculature during pregnancy. Integrins are associated with vascular formation; and osteopontin is a candidate ligand for integrins to promote angiogenesis. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are released from bone marrow into the blood, and incorporate into newly vascularized tissue where they differentiate into mature endothelium. Results of studies in women suggest that EPCs may play an important role in maintaining placental vascular integrity during pregnancy, although little is known about how EPCs are recruited to these tissues. Our goal was to determine the αv integrin mediated effects of osteopontin on EPC adhesion and incorporation into angiogenic vascular networks. EPCs were isolated from 6 h old piglets. RT-PCR revealed that EPCs initially had a monocyte-like phenotype in culture that became more endothelial-like with cell passage. Immunofluorescence microscopy confirmed that the EPCs express platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule, vascular endothelial cadherin, and von Willebrand factor. When EPCs were cultured on OPN-coated slides, the αv integrin subunit was observed in focal adhesions at the basal surface of EPCs. Silencing of αv integrin reduced EPC binding to OPN and focal adhesion assembly. In vitro siRNA knockdown in EPCs, demonstrated that OPN stimulates EPC incorporation into human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) networks via αv-containing integrins. Finally, in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry localized osteopontin near placental blood vessels. In summary, OPN binds the αv integrin subunit on EPCs to support EPC adhesion and increase EPC incorporation into angiogenic vascular networks.

Keywords: Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs), Osteopontin, Alpha v Integrin, Vasculature

Introduction

Successful pregnancy requires expansion and juxtaposition of the placental and uterine vasculatures to facilitate exchange of nutrients, gasses and metabolic wastes between the mother and the fetal-placental tissues. Angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels from the existing vasculature, is fundamental to this process, and placental and uterine blood vessels elongate, dilate, and extend new sprouts during pregnancy. Multiple studies have demonstrated the involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in mediating angiogenic events (Ferrara et al., 1996; Fong et al., 1995; Shalaby et al., 1995). However, several additional key cell signaling pathways have been identified that mediate angiogenesis initiated by integrins and other cell surface receptors, growth factors, lipids and the extracellular matrix (ECM). In particular, integrins, which are transmembrane cell receptors composed of non-covalently linked α and β chains that serve as a link between the cellular cytoskeleton and ECM (Giancotti, Ruoslahti, 1999) during vascular formation (Davis, Camarillo 1993; Senger, et al., 1997; Bayless et al., 2000; Senger et al., 2002; Davis, Bayless 2003).

Osteopontin (OPN, also called secreted phosphoprotein 1, SPP1) is a secreted matricellular protein and a major constituent of uterine and placental tissues of several mammalian species, including humans, mice, sheep, goats, rabbits and pigs (Nomura et al., 1988; Apparao et al., 2003; Joyce et al., 2005; Mirkin et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2014). Therefore, OPN is an ECM ligand for integrins and a likely candidate to promote angiogenesis in the uterus and placenta. Although the αvβ3 integrin is accepted as the primary OPN receptor, OPN binds multiple integrins through Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD)-mediated or alternative integrin recognition sequences to mediate cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesion and haptotaxis driven cell migration (Senger, Perruzzi 1996; Johnson et al., 2003; Humphries et al., 2006; Erikson et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010). In pregnant pigs, OPN expression increases in scattered cells in the stratum compactum stroma directly beneath the uterine luminal epithelium (LE) between Days 9 and 12, and again between Days 30 and 40 of gestation (Garlow et al., 2002). OPN is also expressed at high levels in a population of mesenchymal cells within the placenta beginning on Day 20 after which the number and spatial distribution of these cells increases through Day 85 of gestation (White et al., 2005). OPN is also induced during angiogenesis in support of tumor growth and wound healing (Shijubo et al., 2000; Kelpke et al., 2004; Cook et al., 2005) and expression of OPN correlates with increased production of VEGF in breast cancer cells (Cook et al., 2005), and with acidic FGF (aFGF) in the healing of fractures (Kelpke et al., 2004).

Angiogenic vessels are classically thought to emerge from differentiated adult endothelial cells that line the pre-existing vasculature. However, circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) released from bone marrow have the capacity to migrate and incorporate into newly vascularized tissue where they differentiate into mature endothelium (Asahara et al., 1997; Asahara et al., 1999). EPCs are mononuclear endothelial cell precursors originating from the hematopoietic compartment of bone marrow that are mobilized into the circulation, where they are thought to be recruited to areas of angiogenesis (Asahara et al., 1999 Brunt et al., 2007). EPCs incorporate into cutaneous wounds (Asahara et al., 1999), injured vasculature (Iwakura et al., 2003), myocardial infarcts (Asahara et al., 1999; Orlic et al., 2001), tumors (Asahara et al., 1999), and the uterine endometrium post-ovulation (Asahara et al., 1999) to account for 5–50% of endothelial cells in angiogenic tissues (Crosby et al., 2000; Jackson et al., 2001; Murayama et al., 2002). EPCs are widely studied in cardiovascular medicine for their therapeutic potential in atherosclerosis, but they are now recognized as structural components of the placental vasculature. EPCs have recently been described during normal pregnancies, and numbers decrease in preeclampsia and gestational diabetes (Sugawara et al., 2005a; Buemi et al., 2007; Savvidou et al., 2008; Sugawara et al., 2005b). For the latter, maternal insulin therapy increases EPC numbers during diabetic pregnancy, suggesting that EPC incorporation is critical for proper vascularization during pregnancy (Fadini et al., 2008).

There is evidence that OPN modulates the migration and pro-angiogenic activity of mononuclear and endothelial cells in the progression of new blood vessel formation. OPN can regulate the recruitment (Leali et al., 2003), prevent reverse transmigration (recirculation), and enhance survival of pro-angiogenic monocytes (Burdo et al., 2007). Supernatants from OPN-treated monocytes are highly angiogenic (Naldini et al., 2006), and OPN null mice exhibit significantly decreased total hind limb vascular volume after induction of hind limb ischemia compared with wild type mice, suggesting that OPN is needed for collateral vessel formation and successful angiogenesis (Duvall et al., 2007). In addition, a 32 kDa OPN fragment, produced by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) cleavage, binds strongly to the surface of endothelial cells (Gao et al., 2004).

We hypothesize that OPN binds to integrins and recruits EPCs to sites of angiogenesis based on evidence that: 1) EPCs express integrins, and OPN is an integrin ligand (Denhardt, Guo 1993; Caiado, Dias 2012;); 2) EPCs are circulating monocytes that differentiate into endothelial cells, and OPN is a chemo-attractant to monocytes and endothelial cells (Asahara et al., 1999; Leali et al., 2003; Gao et al., 2004); 3) EPCs are involved in pathologic angiogenesis, and OPN is up-regulated in pathologic angiogenesis (Hristov, Weber 2004; Apte et al., 2005; Duvall et al., 2007); and 4) EPCs increase during healthy pregnancy, and OPN is highly and coordinately up-regulated during healthy pregnancies (Johnson et al., 2003; Matsubara et al., 2006; Sugawara et al., 2005a; Buemi et al., 2007). The objectives of this study were to isolate EPCs from the peripheral blood of pigs and determine the integrin-mediated effects of OPN on EPC adhesion and invasion in vitro.

Materials and Methods

EPC Isolation and Culture

Experimental procedures involving animals as a source of porcine EPCs complied with the Guide for Care and Use of Agricultural Animals and were approved by the Institutional Agricultural Animal Care and Use Committee of Texas A&M University.

EPCs from blood can be isolated and identified based on in vitro adhesion characteristics and by cell surface markers. As EPCs differentiate in culture, they acquire endothelial cell markers such as VE-cadherin, PECAM-1 (CD31) and von Willebrand Factor (vWF) (Parant et al., 2009; Urbich, Dimmeler 2004).

Porcine EPCs (pEPCs) were isolated and cultured following a combination of two methods used for purifying EPCs from human blood (Brunt, et al. 2007, Hirschi, et al. 2008). Whole blood (50cc) was obtained from piglets within 6 h of birth, diluted 1:1 in PBS and layered over Ficoll-Paque (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Following centrifugation (400 × g, 20 min), the mononuclear cell layer was transferred to a new tube and washed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1500 × g, 5 min). Cells were then resuspended in medium-199 (M199) containing 100 μg/ml heparin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.4 mg/ml lyophilized bovine hypothalamic extract (Pel-Freeze Biologicals, Rogers, AK) and 15% fetal bovine serum (Lonza, no. 14–471F, Walkersville, MD), and cultured in flasks coated with 5–10 μg/ml fibronectin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in this medium. After 1 h, nonadherent cells were removed, the flasks were washed, and fibronectin-adherent cells were cultured for 14–21 days or until a confluent monolayer of cells was obtained. These cells appeared to be a pure culture as can be observed in the immunofluorescence characterization data shown in the results of the present study, although the possibility of other cell-types surviving in the cultures cannot be ruled out at this time. At this time, cells were passaged onto gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. G2500, St. Louis, MO) -coated flasks (1 mg/ml) and used for the experiments outlined below.

RT-PCR Analyses

RNA was extracted using an RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for RT-PCR analysis. Partial mRNAs (3 μg) for pEPCs were amplified by RT-PCR using total RNA from different passages. Primers were derived from the porcine mRNA coding sequences for CD14, CD31, CD34 CD45, VEGFR2, CDH5, and integrins αv, α2–1, α2–2, α4, α5, α10, αIIb, β1, β3 and β5 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA.). All products were amplified along with a beta-actin control using a SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen, cat. no. 18080–051 San Diego, CA). The PCR amplification procedure were : 1) 95℃ for 2 min; 2) 58°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 45 sec, and 72°C for 1 min for 25 cycles; and 3) 72°C or 7 min. All samples were loaded in 2% agarose gel containing Bio-Safe (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for electrophoresis at 100 V for 1 h. Images were captured by a UVP PhotoDoc-It™ Imaging Systems fitted with a Canon A480 digital camera in a benchtop UV transilluminator (UVP, LLC Upland, CA). The gene-specific primer sets are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for RT-PCR and cloning

| Gene Name | Sequence forward (F) and reverse (R) |

|---|---|

| CD14 | F: 5’-GTTGCTGCTGCTGCTGCC-3” R: 5’-AAGTTGCAGACGCAGCGGA-3’ |

| CD31 | F: 5’-GAACGGAAGGCTCCCTTGA-3’ R: 5’-AGGGCAGGTTCATAAATAAGTGC-3’ |

| CD34 | F: 5’-GATTGCACTCGTGACCTCGG-3’ R: 5’-TCCGTGAATAAGGGTCTTCGC-3’ |

| CD45 | F: 5’-TGGTGGAATACAATCAGTTTGGAG-3’ R: 5’-CCAATGTGCTGTGTCCTCCAG-3’ |

| VEGFR2 | F: 5’-TCACAATTCCAAAAGTGATCGG-3’ R: 5’-GGTCACTAACAGAAGCAATAAATGG-3’ |

| CDH5 | F: 5’-CAACGAGGGCATCATCAAGC-3’ R: 5’-TCGATGGTGGGGTCTGCGG-3’ |

| αv | F: 5’- CTGGTCTTCGTTTCAGTGTGC-3’ R: 5’-GCCTTGCTGAATGAACTTGG-3’ |

| α2–1 | F: 5’-CATGCCAGATCCCTTCATCT-3’ R: 5’-CGCTTAAGGTTGGAAACTG-3’ |

| α2–2 | F: 5’-GTGCCTTTGGACAGGTTGTT-3’ R: 5’-TCATGGTCTTCTGCAAGCAC-3’ |

| α4 | F: 5’-CAGATGGGATCTCGTCCACC-3’ R: 5’-TCTGCTGGACACCTGTATGC-3’ |

| α5 | F: 5’-GAGCCTGTGGAGTACAAGTCC-3’ R: 5’-CCTTGCCAGAAATAGCTTCC-3’ |

| α10 | F: 5’-TCATTCAGATTCCTTCTACATCCTC-3’ R: 5’-GAATTGTACAGAATGTGTTGTGG-3’ |

| αIIb | F: 5’-GAGTTCCTACTACACCACGAATG-3’ R: 5’-ATCTTTTACAGACCGGGTACATTG-3’ |

| β1 | F: 5’-GACCTGCCTTGGTGTCTGTGC-3’ R: 5’-AGCAACCACACCAGCTACAAT-3’ |

| β3 | F: 5’-AGATTGGAGAACACGGTGAGC-3’ R: 5’-GTACTTGCCCGTGATCTTGC-3’ |

| β5 | F: 5’-TCAACAAGTTCAACAAGTCCTACAA-3’ R: 5’-ATCTCAGCAGTTCAGTGAGAAGAC-3’ |

Immunofluorescence

Porcine EPCs were seeded onto four-well chambered slides coated with fibronectin and cultured overnight (37°C, 5% CO2). Cells were washed once in PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Electron Microscopy Sciences, cat. no. 15712, Hatfield, PA) in PBS, then permeabilized in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100. Immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described (Johnson et al., 2001). After washing with PBS containing 0.3% vol/vol Tween 20, cells were blocked with 10% vol/vol goat serum and incubated overnight at 4°C with 2 μg/μl rabbit polyclonal antibodies to von Willebrand factor (vWF; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM-1; Santa Cruz, Dallas, Texas), vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), αv integrin subunit (AB1930; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and mouse antibodies to focal adhesion kinase (FAK; BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), vinculin (Sigma-Aldrich), and paxillin (Santa Cruz). Tissue-bound primary antibodies were detected with goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 488 (2 μg/μl; Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Rabbit IgG at the same concentration as the primary antibody was used as a negative control. Slides were overlaid with ProLong® Gold antifade reagents with DAPI (Life Technologies –Invitrogen, cat. no. P-36931, Carlsbad, CA) and a cover glass.

Integrin Affinity Chromatography

To identify pEPC integrins that directly bind to OPN, affinity chromatography experiments were performed (Bayless et al., 1998, Erikson et al., 2009). OPN was extracted from bovine milk as previously described (Bayless et al., 1998) coupled to cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose® 4B (Sigma) at 1 mg/ml according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Porcine EPCs were surface-labeled with biotin in 75 cm2 flasks for 1 h at room temperature and washed with PBS as previously described (Erikson et al., 2009). Cells were lysed with 50 mM octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG) (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) containing 1.5 mM MnCl2 and MgCl2 for 30 min on an orbital shaker at 4°C. Cell extracts were centrifuged and then mixed at 20 min intervals with OPN-Sepharose® (0.5 ml) for 2 h at 0°C. The column was washed with 20 ml of 1% OG plus Mg2+ and Mn2+, and 0.5 ml fractions were eluted with 4 ml of 1% wt/vol OG + 10 mM EDTA. Thirty μl of each fraction were separated on a 7% polyacrylamide gel under non-reducing conditions, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) and blocked for 30 min with 5% wt/vol nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% vol/vol Tween 20. Blots were probed for biotin using streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase as previously described (Erikson et al., 2009).

Integrin Immunoprecipitation

As previously described, (Erikson et al., 2009), protein samples were incubated with 2 μg of rabbit antisera directed to integrins αv (AB1930), α4 (AB1924), α5 (AB1928), β1 (MAB1981;), β3 (AB1968), β6 (MAB2076Z), αvβ3 (MAB1976Z), or αvβ5 (MAB1961) (All from Chemicon, Temecula, CA) in 500 μl of lysis buffer containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40 overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. Twenty μl of protein G Dynabeads® (Invitrogen, cat. no. 10003D, Carlsbad, CA) were added to each sample, incubated for another 2 h, and washed extensively. Magnetic beads were suspended in 1X Laemmli sample buffer (Santa Cruz Biotech, cat. no. 161–0737, Dallas, TX) containing 2% β-mercaptoethanol for Western blot analyses.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analyses

Porcine EPCs (approximately 40% confluent in a T25 flask) were trypsinized, centrifuged (350 × g, 3.5 min) and then extracted in 400 μl RIPA lysis buffer with protease inhibitors (Sigma, cat. no. P8340) and 3X protein sample buffer. Proteins in cell extracts (30 μl per lane) were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gels under non-reducing conditions, and transferred to PVDF membranes for 2 h with methanol on ice. Blots were then blocked with 2% milk on a shaker for 1 h at room temperature, incubated with milk containing polyclonal rabbit αv antibody (EMD Millipore, AB1930, Billerica, MA) at a 1:1000 dilution, mouse GAPDH antibody (Abcam, AB9483, Cambridge, MA) at a 1:10000 dilution, and mouse alpha tubulin antibody (Enzo Life Sciences, cat. no. IMG-80196, Farmingdale, NY) at a 1:10000 dilution overnight at 4°C with gentle mixing, and then incubated in the corresponding rabbit or mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) at a 1:5000 dilution in milk for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive proteins were detected using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (2 ml per blot) (EMD Millipore, lit. no. P36599A Billerica, MA) and blots were developed and scanned by a HP Scanjet G3010 Photo Scanner (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA).

Alpha v Integrin and GAPDH Knockdown Using siRNA

The following small interfering RNAs were obtained from Ambion (Carlsbad, CA): αv (5’-CCAACUUCAUUAUAGAUUU-3’ and 5’-AAAUCUAUAAUGAAGUUGG-3’) and GAPDH (5’-GCCUCAAGAUCAUCAGCAA-3’ and 5’-UUGCUGAUGAUCUUGAGG-3’). Small interference RNA stocks (5 nmol) were resuspended in 50 μl nuclease free H2O (100 μM) and stored at −20°C. siRNAs (3.9 μl) were mixed with 906.1 μl Opti-MEM® (Life Technologies–Invitrogen, cat. no. 31985–062, Carlsbad, CA) (final concentration = 75 nM). In a separate tube, 15.6 μl of siPORT™ amine (Life Technologies–Invitrogen, cat. no. AM4502, Carlsbad, CA) was mixed with 894.4 μl Opti-MEM®. Mixtures containing siRNA and siPORT amine were combined and incubated for at least 10 min at room temperature. Porcine EPCs (80% confluent, 0.8 × 106 cells) were resuspended in 800 μl of antibiotic-free DMEM, combined with 1.8 ml transfection mixture, and seeded onto 1 mg/ml gelatin in PBS-coated T25 flasks. Antibiotic-free DMEM adjusted to a final volume of 5.2 ml. After 8 h of transfection, cultures were spiked with 5.2 ml growth medium without antibiotics. Endothelial growth medium was prepared by combining 500 ml M199, 0.2 g lyophilized endothelial growth supplement, heparin, and 12.5% fetal bovine serum as previously described (Bayless et al., 2009). Medium was changed after 24 h and the cells were allowed to grow for another 48 h (37°C, 5% CO2) prior to use. Protein samples were extracted to confirm successful knockdown of αv or GAPDH by western blot analyses in all experiments (n=3).

Cell Attachment Assays

Cell attachment assays were conducted as previously described (Bayless et al., 1998, Erikson et al., 2009). High-binding polystyrene microwells (Corning-Costar, no. 3690, Corning, NY) were coated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl of recombinant and native forms of OPN (n=3 replicates/treatment). We used the recombinantly purified thrombin fragment of rat OPN containing intact RGD binding sequence (RGD) or the mutated RAD sequence (RAD; plasmids were a gift from Dr. Magnus Hook, Institute of Biosciences & Technology, Texas A&M Health Science Center) (McFarland et al., 1995), native bovine OPN (bOPN) (purified as in Bayless et al., 1997); bovine fibronectin as a positive control (bFN) (Sigma-Aldrich); or bovine serum albumin as a negative control (BSA). Proteins were coated at concentrations ranging from 0 – 20 μg/ml. After blocking each well in 10 mg/ml BSA in PBS (100 μl), 50,000 pEPCs were allowed to attach for 1 h (37°C, 5% CO2). In all cell attachment experiments, nonadherent cells were removed by washing in isotonic saline and wells were fixed in 4% formalin in PBS. Plates were stained with 0.1% wt/vol Amido black in 10% acetic acid and 30% methanol for 15 min, rinsed and Amido black was solubilized with 50 μl 2 N NaOH to obtain an absorbance reading at 595 nm which directly correlated with the number of cells stained in each well (Davis, Camarillo 1993). To demonstrate that binding of pEPCs to OPN was integrin-dependent, an attachment assay was performed in which levels of cations were varied. Polystyrene microwells (Corning-Costar, Corning, NY) were coated overnight at 4°C with 20 μg/ml of bOPN, rOPN, Type 1 Collagen, bFN and blocked for 1 hour with 10 mg/ml BSA. Cells were washed in cation-free Puck’s Saline A (PSA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and resuspended in PSA containing 100 μg/ml BSA. Cells were allowed to attach for 1 h in either PSA with 2 mM Ca2+ 1 mM Mg2+ or PSA with no cations (n=3 replicates/treatments). Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Collagen Gel Invasion Assays

Type I collagen was prepared from rat tail tendons by non-proteolytic isolation using acetic acid (Sigma, cat. no. A6283, Louis, MO) and collagen gel invasion assays performed as previously described (Bayless et al., 2009). Collagen matrices were prepared on ice by combining 350 μl of collagen type I (7.1 mg/ml), 39 μl 10X M199 (Invitrogen, cat. no. 11825–015, Carlsbad, CA), 2.1 μl 5N NaOH, and 609 μl M199 (Gibco–Invitrogen, cat. no. 11150, Carlsbad, CA) to reach a final concentration of 2.5 mg/ml. Eighty μl of the mixture was added to each 6.5 mm Transwell® with 3.0 μm pore polyester membrane insert in a 24 well plate (Corning-Costar, lot. 12602010, Corning, NY).). Confluent pEPCs (passage 22–26), (HUVECs, passage 3–6, Lonza, Allendale, NJ) or porcine trophectoderm cells (pTr2, passage 8–10; Frank et al., 2017) were washed with HEPES buffered saline (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) before trypsinization from T75 flasks. Cells were resuspended at 40,000 (HUVEC) and 30,000 (EPCs) cells per 10 μl in M199, based on counts obtained from a Cellometer® Auto 1000 (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA) or Bright-line hemacytometer (VWR, cat. no. 15170–168, Radnor, PA). Porcine EPCs were labeled in a 1 ml volume with 1 μM CellTracker™ CM-DiI (3×106 cells) (Molecular Probes®, cat. no. C-7001, Eugene, OR) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were washed four times with 1 ml of M199 following repeated centrifugation (350 × g, 3.5 min) to remove excess DiI. 10 μl of HUVEC (40,000 cells) and DiI-labeled EPC (30,000 cells) were added into each well insert. One hundred μl suspension of equilibrated M199 containing Reduced serum II (RSII) (Bayless et al., 2009) (1:250), VEGF (40 ng/ml, R&D, 293-VE, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), bFGF (40 ng/ml, 234-FSE, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml) were added on the top of each polymerized collagen matrix. One ml of the medium was added into the well under each insert with 1 μM sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) (Avanti Polar lipids, cat. no. 860492, Alabaster, AL). Both the top and the bottom media were supplemented with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) (50 ng/ml) (Sigma, cat. no. P1585, Louis, MO). In experiments testing the effects of OPN, bOPN or PBS, vehicle was added into lower chambers at a final concentration of 0, 30, and 100 μg/ml in a 1 ml volume. After 24 h of incubation (37°C, 5% CO2), the top medium (100 μl) was replaced with fresh medium after washing with HEPES. All inserts were washed with PBS without cations, fixed in 4% PFA overnight and then stained with 1 μM DAPI (Molecular Probes®, cat. no. D1306, Eugene, OR) for at least 30 min at room temperature (or 4°C overnight) and stored in double-distilled water for further analysis. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell Counting

All invading cells were counted using an Olympus CKX41 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) with an eyepiece equipped with a reticle displaying a 10 × 10 grid (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Monolayers were identified under the fluorescence DAPI channel initially, and then all DAPI or DiI stained cell nuclei below the surface were considered invading cells as the focus was adjusted up and down routinely to avoid duplicate counting. The center field was selected for quantification in each gel (n=3) and the total number was averaged for each experiment.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and presented as means and standard errors (SE). Tests of statistical significance were performed using the appropriate error terms according to the expectation of the mean squares for error with significance set at p < 0.05.

Adult Animals, Tissue Collection, In situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry

Sexually mature gilts of similar age, weight and genetic background were observed daily for estrus (Day 0). Gilts exhibiting at least two estrous cycles of normal duration (18 to 21 days) were mated 12 and 24 h after the second estrus to boars of proven fertility, and hysterecomized on Day 85 of gestation (n=4). At hysterectomy (Oliveira et al., 2017) several sections (thickness ~ 1–1.5 cm) from the middle of each uterine horn were placed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde fixative for 24 h and then embedded in Paraplast Plus (Oxford Labware, St. Louis, MO.

Cell-specific expression of OPN mRNA in sections (5 μm) of the porcine uterine/placental tissue was determined by radioactive in situ hybridization analysis as described previously (Johnson et al., 1999). Sections from paraffin blocks from each animal were analyzed. Radiolabeled antisense or sense cRNA probes were generated by in vitro transcription using linearized plasmid template, RNA polymerases, and [α−35S]-UTP. Deparaffinized, rehydrated and deproteinated uterine tissue sections were hybridized with radiolabeled antisense or sense cRNA probes. After hybridization, washing and ribonuclease A digestion, slides were dipped in NTB-2 liquid photographic emulsion (Kodak, Rochester, NY), and exposed at 4°C for 7 to 10 days. Slides were developed in Kodak D-19 developer, counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Fairlawn, NJ), and then dehydrated through a graded series of alcohol to xylene. Coverslips were then affixed with Permount (Fisher).

OPN protein was immunolocalized in porcine uterine/placental tissues as described previously (Steinhauser et al., 2017). A rabbit anti-bovine OPN affinity-purified polyclonal IgG (kindly provided by Dr. G. Killian) was used at 25 μg/mL with a boiling citrate buffer antigen retrieval (Gabler et al., 2003). Purified non-relevant rabbit IgG, at a concentration equal to that for the primary IgG, was used as the negative control. Immunoreactive protein was visualized in paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm thick) using the Vectastain ABC Kit (catalog no. PK-4001; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) according to kit instructions with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (catalog no. D5637; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as the color substrate. Sections immunostained for OPN were counterstained with Harris modified hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific). Coverslips were affixed using Permount mounting medium (Fisher Scientific).

Digital images of representative fields were recorded under brightfield or darkfield illumination and evaluated using an Axioplan 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) interfaced with an Axioplan HR digital camera and Axiovision 4.3 software. Photographic plates were assembled using Adobe Photoshop (version 6.0, Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA).

Results

Porcine EPCs Develop an Endothelial-like Phenotype in Culture

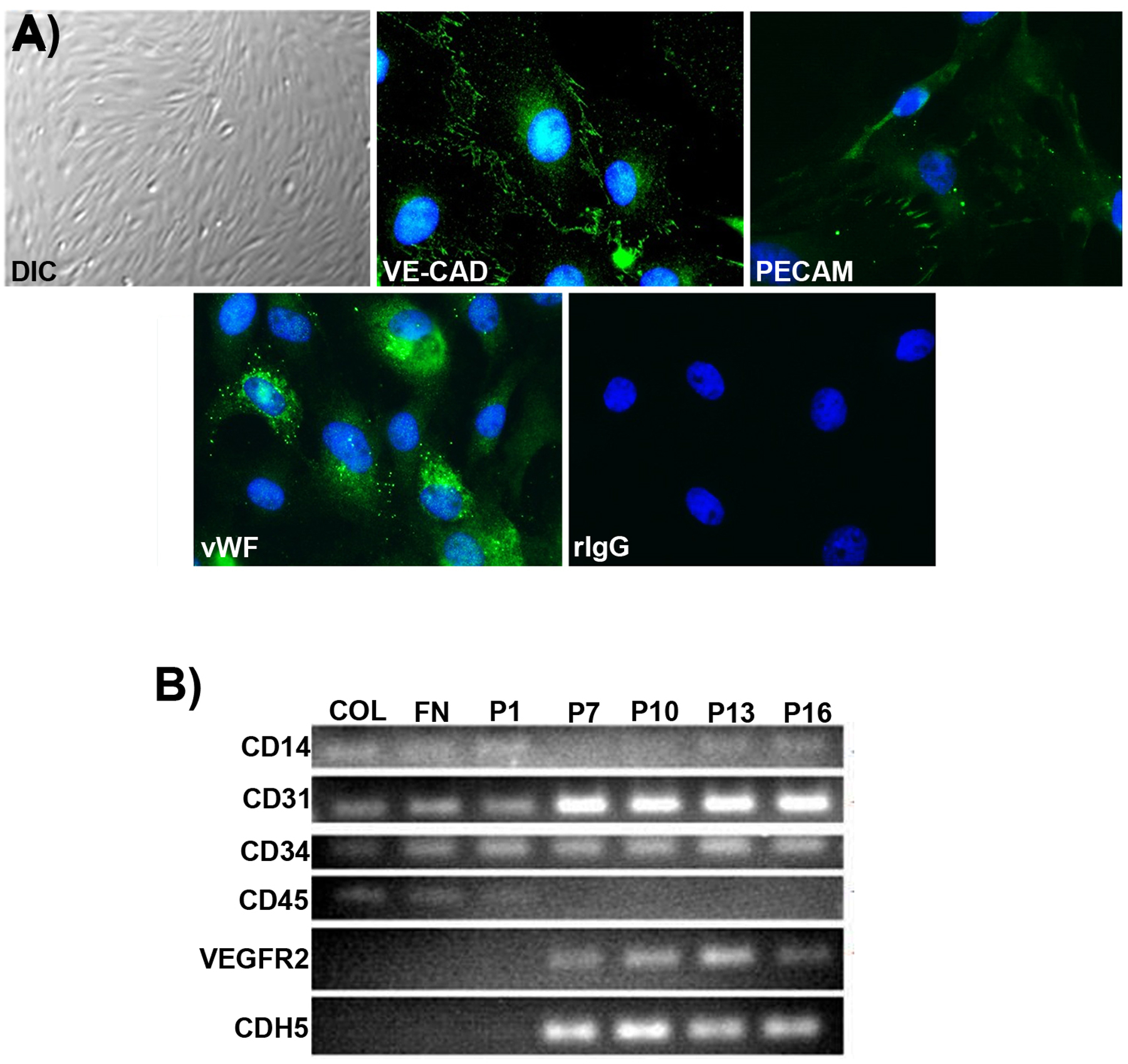

Cultured pEPCs had a cobblestone morphology and expressed vWF, PECAM-1, and VE-cadherin proteins (Figure 1A). PECAM and VE-cadherin localization was consistent with endothelial cell junctions, and vWF localization was consistent with Weibel-Palade bodies (Wagner et al., 1982). RT-PCR analyses of pEPCs indicated that expression of the endothelial cell markers CD31 (PECAM-1), VEGFR2, and CDH5 increased from passage 1 to passage 16, while expression of the monocyte markers, CD14 and CD45, decreased with passage. The expression of CD34 remained constant (Figure 1B). Therefore, pEPCs initially had a monocyte-like phenotype in culture that became more endothelial-like with cell passage. This progression in phenotype is similar to that observed for EPCs in vivo.

Figure 1.

Cultured pEPCs have an endothelial cell phenotype. A) Differential interference contrast (DIC) imaging and immunofluorescence staining demonstrate a cobblestone morphology, expression of VE-cadherin (VE-CAD) and PECAM-1 (PECAM) proteins at the junctions between cells, and vWF in Weibel-Palade bodies (passage 22). Non-relevant rabbit immunoglobulin (rIgG) was used as a negative control (width of field for the DIC image = 540 μm, and fluorescence images = 140μm). B) RT-PCR demonstrates that expression of CD31, VEGFR2, and CDH5 increased from passage 1 to passage 16, while expression of CD14 and CD45 decreased with passage. Expression of CD133 was not detected (data not shown) and CD34 remained constant across passages. Collagen, COL; FN, Fibronectin; P, Passage.

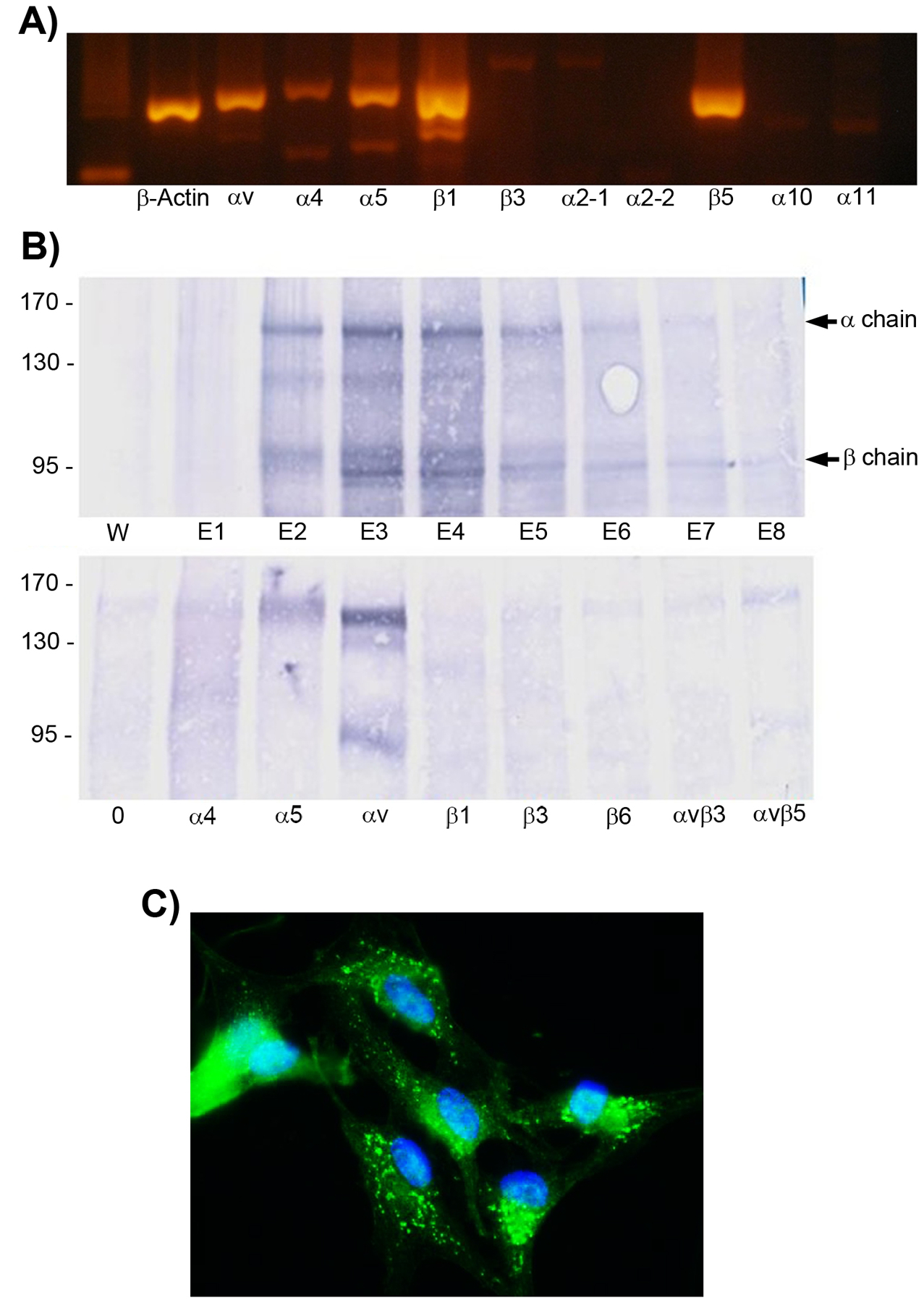

Porcine EPCs Express Integrins that Bind to OPN

RT-PCR analyses were conducted to determine integrin expression by cultured pEPCs (passage 22). Porcine EPCs contained mRNAs for integrin subunits αv, α4, α5, β1 and β5 (Figure 2A). Affinity chromatography experiments were performed with pEPCs to demonstrate direct binding of integrin receptors to OPN (Figure 2B). Integrins eluted in fractions E2, E3, and E4, with α integrin chains migrating at approximately 150 kDa and β integrin chains migrating at approximately 95–100 kDa (Figure 2B). To identify integrins contained within the eluted fractions, immunoprecipitation assays were performed on pEPC cell lysates using antibodies directed against the α4, α5, αv, β1, β3 and β5 integrin subunits and the αvβ3 and αvβ5 receptors. The αv integrin subunit was present in the eluted fractions (Figure 2B). Further, when pEPCs were cultured on OPN-coated slides, the αv integrin subunit was detected in large aggregates as components of focal adhesions at the basal surface of pEPCs cells (Figure 2C). Collectively, these results indicate that pEPCs express αv-containing integrin receptor that binds OPN to assemble focal adhesions.

Figure 2.

A) Integrin expression by pEPCs. RT-PCR analyses of integrin subunits expressed in pEPCs from passage 22. A band indicates the presence of a particular integrin subunit. B) Alpha v integrin on EPCs directly binds to OPN. Top panel: pEPCs were surface-labeled with biotin. detergent extracts of the cells mixed with OPN-Sepharose, integrins bound to OPN eluted with EDTA, and wash (W) and EDTA eluates (E1–E8) separated by SDS-PAGE. Bottom panel: Immunoprecipitation of pooled EDTA eluates (E2–E4) was performed using Protein A-Sepharose and antibodies directed to the indicated integrin subunits. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions. C) Immunofluorescence staining of pEPCs cultured on OPN using antisera directed to the αv integrin subunit shows aggregates of immunoreactive αv integrin at the base of the cells suggesting the assembly of focal adhesions (width of field = 140 μm).

Silencing of αv Integrin Reduces pEPC binding to OPN and Focal Adhesion Assembly

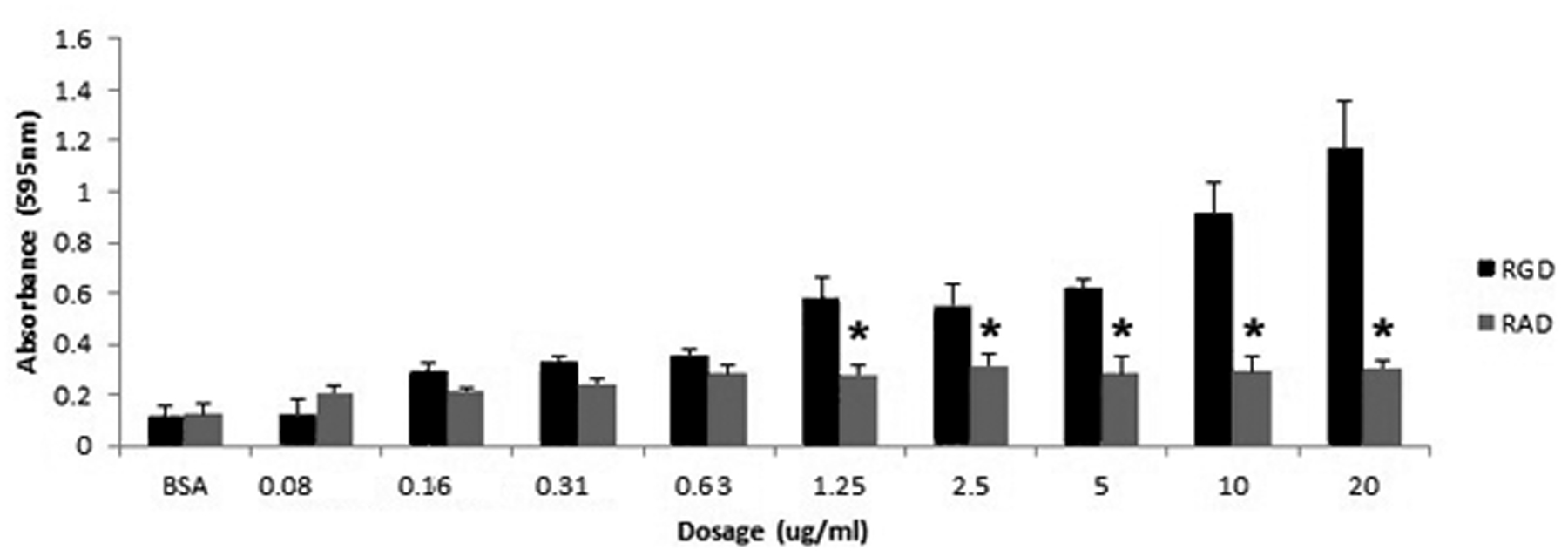

Figure 3 demonstrates pEPCs adhered to recombinant rat OPN (rOPN) in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, mutation of the rOPN RGD integrin attachment sequence to RAD decreased adhesion, suggesting that pEPC adheres to OPN through the RGD integrin-binding sequence.

Figure 3.

Porcine EPCs dose-dependently bind to recombinant rat OPN in an RGD-dependent manner. Adhesion assays were conducted with recombinant rat OPN containing an intact integrin binding sequence (RGD) or, rat OPN with a mutated integrin binding sequence (RAD). Porcine EPCs dose-dependently bound to recombinant rat OPN containing an RGD sequence, but not the mutated RAD control, indicating a dependence on the RGD sequence to promote pEPC attachment to OPN. Values represent average absorbance readings of adhered cells stained with Amido black (595 nm; 3 wells/data point).

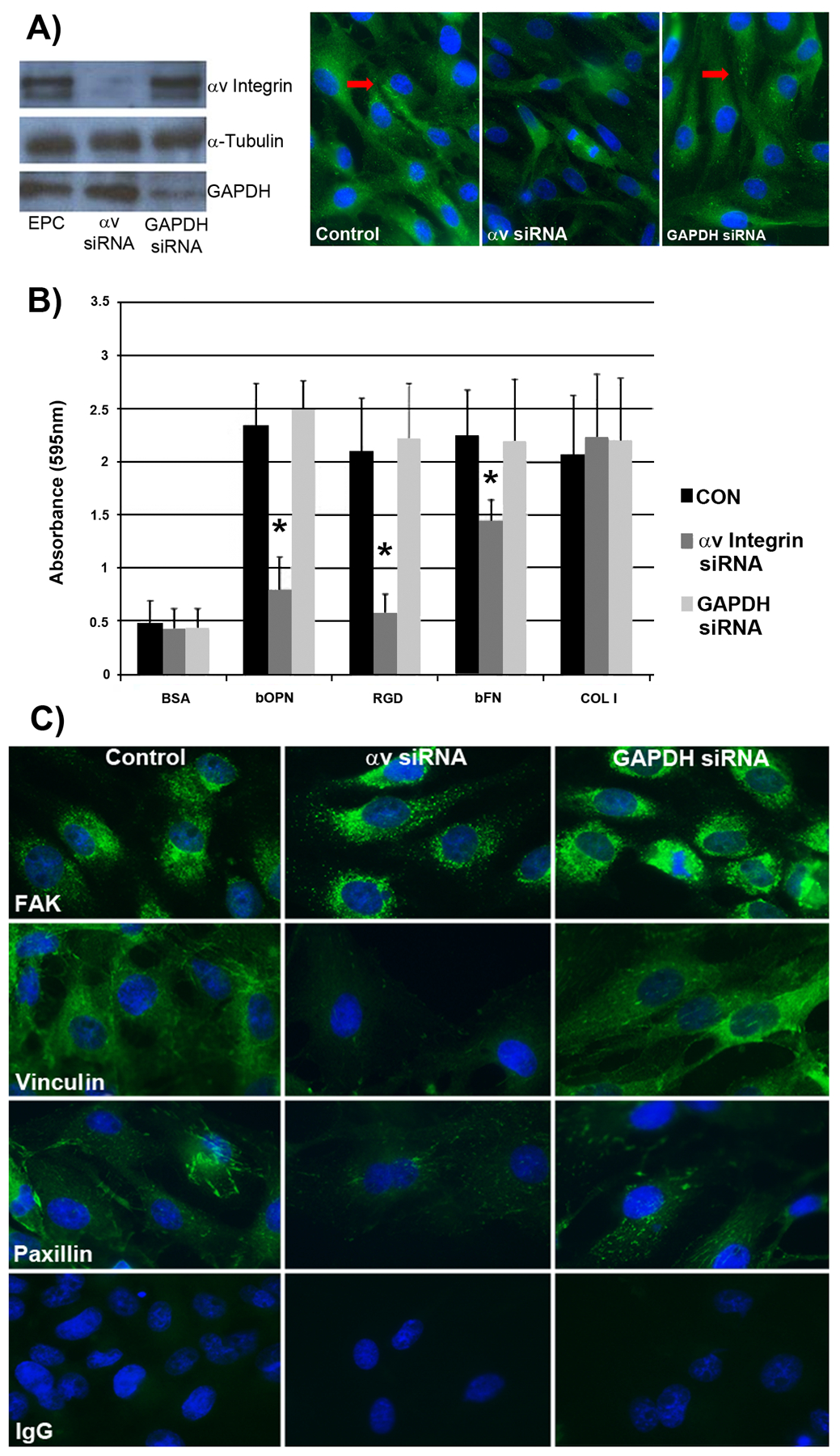

To confirm a direct functional role for αv integrin containing receptors in mediating pEPC attachment to OPN, siRNA experiments were conducted. Western blotting and immunofluorescence microscopy were utilized to determine the ability of relevant siRNAs to knock down αv protein in pEPCs. Porcine EPCs were treated with no siRNA (control) or siRNAs targeting either the αv subunit or GAPDH; the GAPDH siRNA was utilized to determine if the siRNA itself would affect the function of cells. Cells treated with αv siRNA had appreciably less αv protein in cell lysates when compared to the control and GAPDH treated cells (Figure 4A). Cells treated with GAPDH siRNA exhibited a decrease in GAPDH protein in cell lysates compared to control and αv siRNA treated cells. Further, knockdown of αv integrin decreased the ability of pEPCs to assemble αv-mediated focal adhesions in response to binding OPN in culture (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Silencing of αv integrin in pEPCs using siRNA demonstrates that αv is required for pEPC attachment to OPN to form focal adhesions. A) Left panel: Western blots confirming successful knockdown of αv integrin and GAPDH by their respective siRNA targeting sequences. Right panel: Immunofluorescence staining for αv integrin showing αv integrin knockdown, but not GAPDH knockdown, decreases focal adhesion assembly as pEPCs bind to OPN in culture. The arrows represent punctate immunostaining for the signals representing focal adhesion formation at the base of pEPCs (width of field = 140 μm). B) Adhesion assays were conducted with bovine OPN (bOPN), recombinant rat OPN with an intact RGD sequence (RGD), bovine fibronectin (bFN), and type I collagen (COL I). Adherent cells were fixed, stained with Amido black, and quantified. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) served as a negative control and Type I collagen served as a positive control. Values represent absorbance readings (595 nm; 3×3 wells/data point). C) Immunofluorescence staining of control (non-treated) pEPCs, and pEPCs treated with αv or GAPDH siRNAs (75 nM, 48 h transfection) demonstrate that silencing of αv integrin reduces vinculin and paxillin incorporation into focal adhesions as pEPCs attach to the underlying matrix. A nonrelevant immunoglobulin IgG (width of field = 140 μm).

To test whether the αv integrin is required for binding to OPN, pEPCs treated with no siRNA, or siRNA directed to αv integrin, or siRNA directed to GAPDH were evaluated to determine binding to various ECM proteins. Results from the cell adhesion assays (see Figure 4B) indicated decreased ability of pEPCs to bind to bOPN, recombinant rat OPN with an intact RGD sequence or bovine fibronectin (bFN) (P < 0.05). There was no effect of αv siRNA on pEPC adhesion to type I collagen, as expected, because αv integrins are not involved in collagen binding (Humphries 2006). Consistent adhesion to all substrates occurred when pEPCs were treated with siRNA directed to GAPDH, as well as non-transfected cells. There was little adhesion seen on BSA substrate, as expected (Figure 4B).

Because focal adhesions have been implicated in mediating cell attachment (Dumbauld et al., 2013), immunofluorescence staining was conducted on pEPCs attached to gelatin-coated coverslips. Punctate staining patterns indicative of focal adhesion assembly at the base of cells as they attach to the underlying matrix occurred in control and GAPDH siRNA-treated pEPCs. However, pEPCs treated with αv siRNA expressed less vinculin and paxillin immunostaining, although immunostaining for FAK did not appear to be affected (Figure 4C).

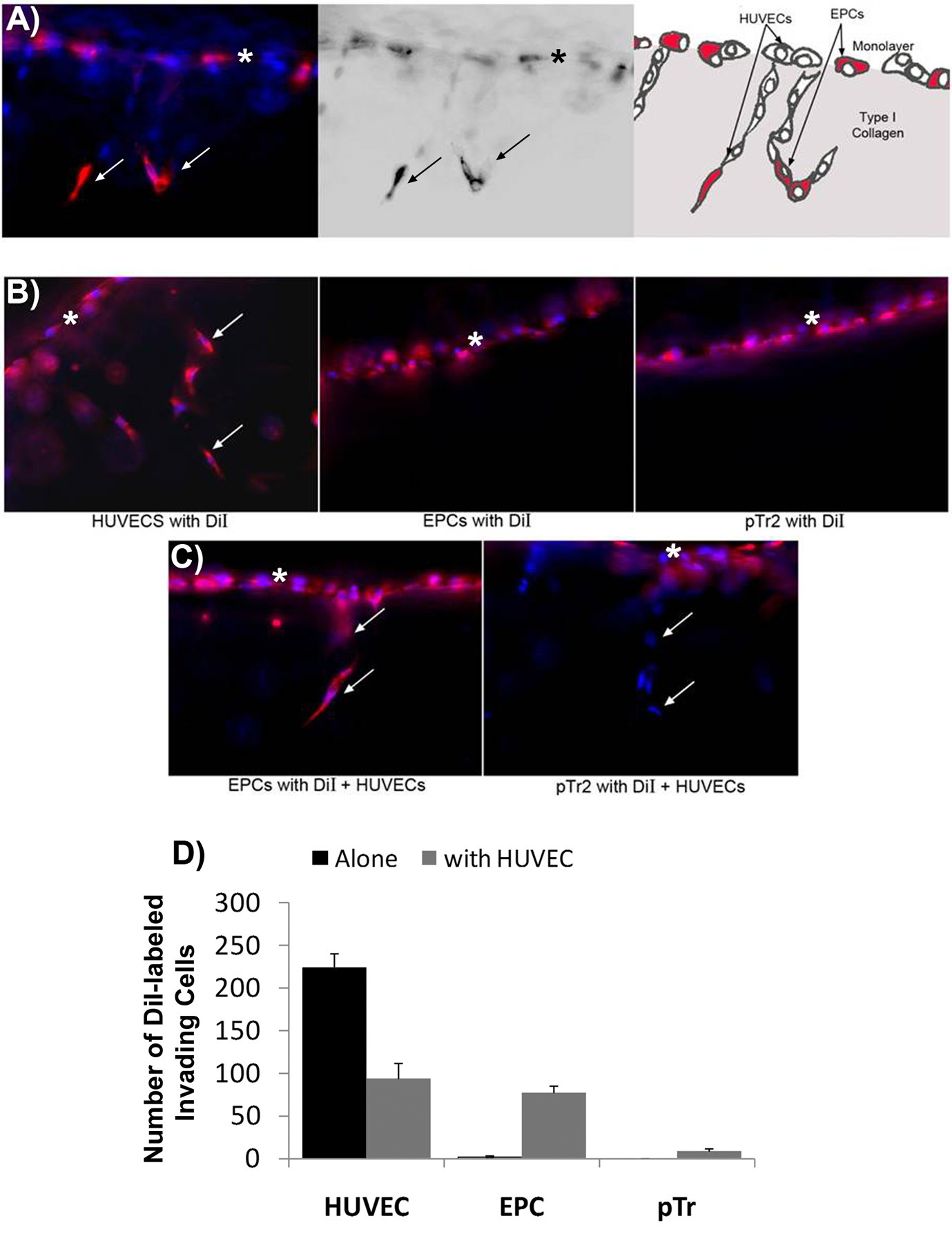

Porcine EPCs Incorporate into Sprouting HUVEC Networks

Porcine EPCs are mobilized from bone marrow, enter the bloodstream and respond to angiogenic cues to incorporate into newly-forming vascular networks (Asahara et al., 1999). Therefore we determined if pEPCs invade into a collagen matrix and form vascular tubes in vitro. Porcine EPCs, HUVECs, and pTr2 cells were labeled with DiI, placed on the surface of 3D type I collagen matrices in the presence of VEGF, bFGF, and S1P, and allowed to invade into the collagen (Bayless et al., 2009). The pTR2 cells were included in this experiment initially as a positive control, because as trophoblast cells we expected these cells to be invasive by nature. Even the porcine trophoblast will invade the endometrium if introduced beneath the uterine luminal epithelial barrier (Samuel, Perry 1972). Figures 5A–5C demonstrate these cultures from the side of vertically sliced collagen gels. HUVECs cultured alone invaded (arrows) below the original monolayer (*). However, when pEPCs or pTr2 cells were cultured alone they did not invade into the underlying type I collagen matrix, as only a single monolayer of cells was observed at the top of the collagen gel with no invading structures underneath (Figure 5B). The observation that pTR2 cells did not invade the matrix is interesting and warrants further investigation. During angiogenesis in vivo, EPCs incorporate into angiogenic networks composed of adult endothelial cells; therefore we tested whether pEPCs would incorporate into sprouting vascular networks of HUVECs. Porcine EPCs or control pTr2 cells were labeled with DiI and placed in monolayers at the surface of a type I collagen matrix with non-labeled HUVEC, cultured and then all cells were stained with DAPI to monitor invasion of both cell types. Porcine EPCs incorporated into sprouting HUVEC networks (see arrows), whereas pTr2 cells remained on the surface of the collagen matrix as a monolayer (Figure 5C). The number of invading cells were quantified as shown in Figure 5D.

Figure. 5.

Porcine EPCs incorporate into sprouting HUVEC networks. DiI-labeled HUVECs, pEPCs or porcine trophectoderm (pTr) cells were allowed to invade into type I collagen gels and vertical sections of the gels were photographed from the side. Arrows indicate DiI-labeled cells invading beneath the monolayer (*). A) Schematic representation of DiI-labeled pEPCs that have incorporated into sprouting HUVEC (DAPI-labeled) networks. Note the mixture of DiI-labeled EPCs (pink) and non-labeled HUVECs (blue) present in the initial monolayer culture. Also note the presence of both blue and pink cells within the underlying collagen indicating in vitro cell invasion to form vascular structures. B) HUVECs cultured alone invade into type I collagen gels, whereas pEPCs (EPC) or pTr2 cells cultured alone do not invade. C) Porcine EPCs invade into type I collagen gels when cultured with HUVECs, but co-culture with HUVECs does not affect pTr2 cell invasion. D) Quantification of pEPC invasion into collagen matrices. The x axis denotes the cell type that is labeled with DiI. The y axis denotes the number of labeled invading cells when no unlabeled HUVECs are included in the culture (blue bars) or the number of labeled invading cells if unlabeled HUVECs are included in the culture (orange bars). Note that labeled EPCs do not invade unless accompanied in culture by unlabeled HUVECs. Also note that if all HUVECs are labeled with DiI (HUVEC, blue bar), then more labeled cells invade than if both labeled and unlabeled HUVECs (HUVEC, orange bar) are added to the culture. The number of DiI labeled invading cells was quantified from experiments shown in panels B and C. Three fields from each treatment group were used to obtain average number of invading cells per 1mm2 field (+/− SD). Data shown are representative of n=4 experiments.

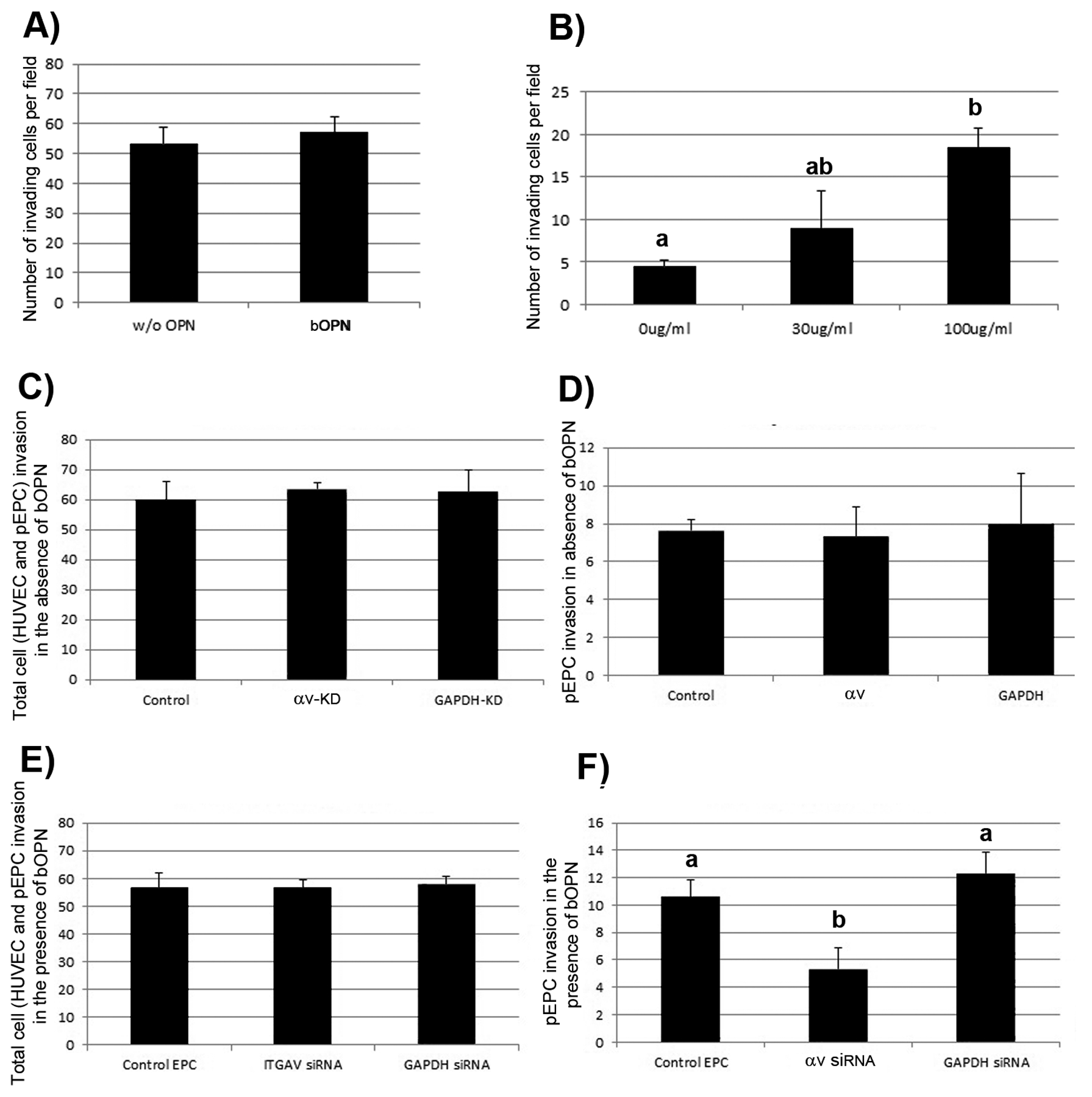

OPN Stimulates pEPC Incorporation into HUVEC Networks Via αv Integrin

We next tested whether placental and uterine OPN might attract EPCs into sites of active angiogenesis using the assay system described previously (Figure 5). In these experiments, culture medium with or without OPN was added to the lower chamber of collagen coated culture well inserts and HUVECs were placed on the surface of the collagen matrices in the presence or absence of DiI labeled pEPCs to monitor pEPC incorporation into sprouting HUVEC networks. HUVECs cultured alone were labeled with DiI, but HUVEC co-cultured with pEPC were unlabeled. While OPN did not affect HUVEC sprouting responses (Figure 6A, left panel), OPN dose-dependently stimulated pEPC incorporation into HUVEC networks (Figure 6A, right panel).

Figure 6.

OPN increases incorporation of pEPCs into sprouting HUVEC networks. A): DiI labeled HUVECs were allowed to invade in the presence of 0 μg/ml (w/o bOPN) or 100 μg/ml bOPN. B): unlabeled HUVECs were seeded along with DiI labeled pEPCs onto collagen gels, and soluble bOPN was added to culture medium in the bottom chamber at the concentrations indicated. Cultures were fixed, stained with DAPI, and the number of invading HUVEC (left panel) and pEPCs (right panel) was quantified. Four fields from each treatment group were used to obtain average number of invading cells per 1 mm2 field (+/− SD). Data shown are representative of 4 independent experiments (bars that are significantly different do not share the same letter). C-D) Alpha v integrin knockdown does not affect HUVEC and/or pEPC invasion in the absence of bOPN. DiI-labeled EPCs expressing no siRNA (Control) or siRNA directed to αv integrin (αv--KD) or GAPDH (GAPDH-KD) were co-cultured on the surface of collagen gels C): Total cell (HUVEC and pEPC) invasion in the absence of bOPN. D): pEPC invasion in the absence of bOPN. Four fields from each treatment group were used to obtain average number of invading cells per 1 mm2 field (+/− SD). Each experiment was performed in triplicate (p=0.10). E-F) bOPN requires αv integrin expressed on pEPCs to increase incorporation of pEPCs into sprouting HUVEC networks. DiI-labeled pEPCs expressing no siRNA (Control) or siRNA directed to αv integrin (αV-KD) or GAPDH (GAPDH-KD) were co-cultured in the presence of 100μg/ml soluble bOPN added to the culture medium in the bottom chamber. E): Total cell (HUVEC and pEPC) invasion in the presence of bOPN. F): pEPC invasion in the presence of bOPN. Four fields from each treatment group per experiment were used to obtain average number of invading cells per 1 mm2 field (+/− SD). Data shown represent 3 independent experiments (P<0.05).

We next asked whether OPN binds to αv-containing integrin receptors on pEPCs to increase pEPC incorporation into assembling HUVEC networks. HUVECs were co-cultured in invasion assays with control pEPCs (no siRNA treatment), or pEPCs treated with siRNA directed against αv integrin or GAPDH. In the absence of OPN, the total number of invading cells, DAPI-stained HUVEC plus DiI-labeled EPCs, was not different between cultures containing control- or siRNA-treated pEPCs (Figure 6B, left panel). Porcine EPCs (DiI-labeled) lacking αv integrin or GAPDH expression invaded the collagen matrices similarly to control pEPCs, indicating no role for αv integrin in stimulating pEPC incorporation into HUVEC networks in the absence of OPN (Figure 6B, right panel).

Next, the same experiment was conducted as in Figure 6B, except for in the presence of OPN introduced into the lower chamber of the Transwell plate. Control pEPCs (no siRNA treatment), or pEPCs treated with siRNA directed to αv integrin or GAPDH were tested in invasion assays with HUVECs in the presence of 100 μg/ml OPN. In the presence of OPN, the total number of invading cells, HUVEC plus DiI-labeled pEPCs, was not affected by αv knockdown (Figure 6C, left panel). However knockdown of αv expression in pEPCs decreased the number of pEPCs that incorporated into sprouting HUVEC networks, indicating that OPN binds αv-containing integrin receptors on pEPCs to increase pEPC incorporation into HUVEC networks (Figure 6C, right panel).

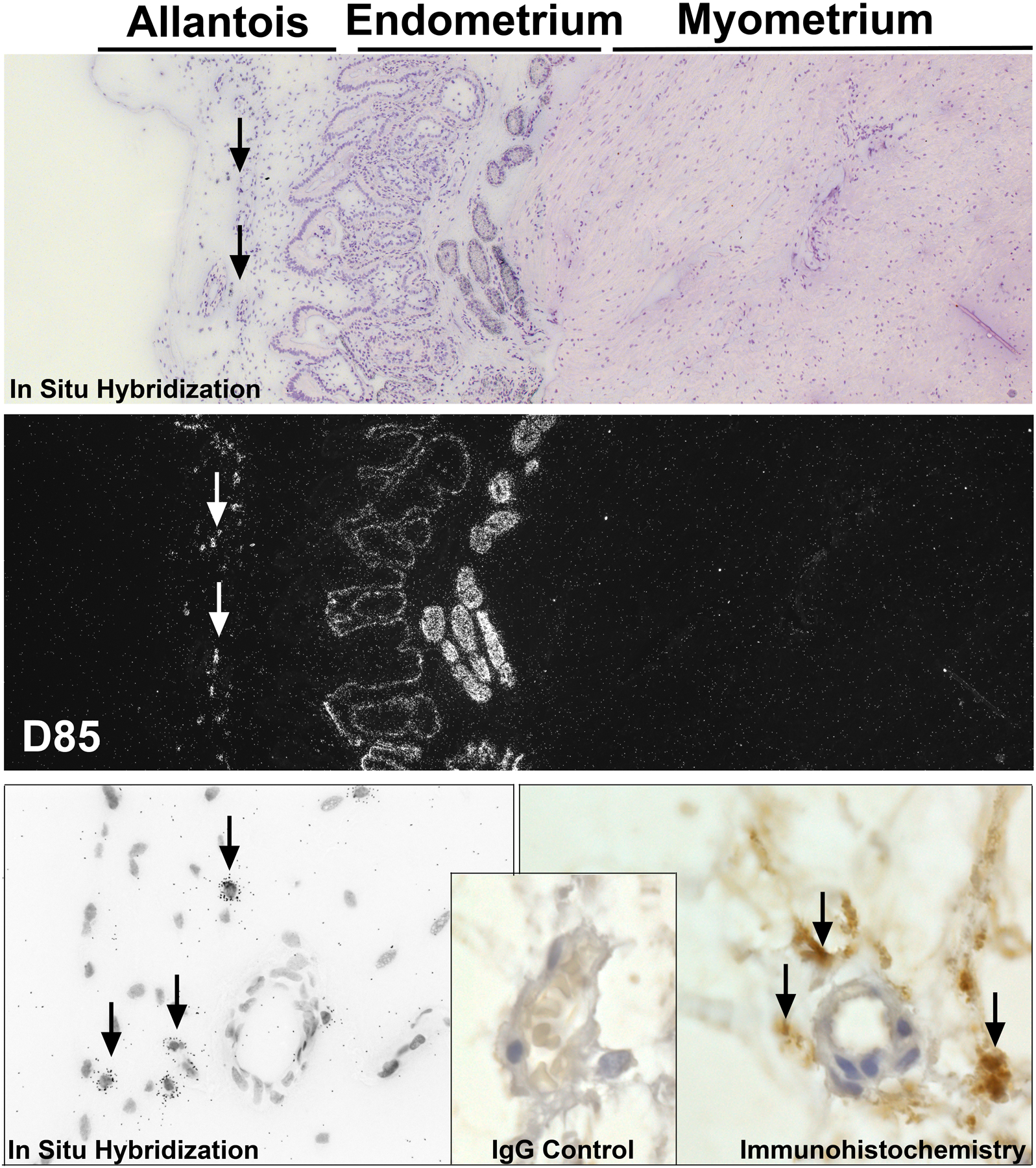

OPN is Expressed Near Placental Blood Vessels

We localized OPN mRNA by in situ hybridization and OPN protein by immunohistochemistry within uterine/placental tissues from pigs on Day 85 of pregnancy (Figure 7). As previously reported, OPN mRNA was present in the uterine LE and GE (Garlow et al., 2002; White et al., 2005). However, a population of cells was localized near blood vessels within the allantois of the placenta also contained OPN mRNA, and OPN protein accumulated in the ECM near the blood vessels of the allantois (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

OPN accumulates in the ECM around the placental vasculature. Localization of OPN mRNA, top panels (Corresponding brightfield and darkfield images from in situ hybridization) and bottom left panel (brightfield image at higher magnification), and localization of OPN protein by immunohistochemistry, bottom right panel. Arrows indicate OPN mRNA within cells or OPN protein in the ECM of the mesenchyme of the allantois.

Discussion

During pregnancy, survival and growth of the conceptus (embryo/fetus and associated placental membranes) depends on the transplacental exchange of gases, micronutrients (amino acids, glucose) and macromolecules (proteins), as well as the production of hormones, cytokines and other regulatory molecules that affect growth and development of the conceptus throughout gestation (Enders, 1999). Maternal and fetal microvasculatures must be brought into close apposition to allow for this transplacental exchange of molecules while maintaining separation of the maternal and fetal-placental circulatory systems. Regardless of whether the placenta is epitheliochrial, synepitheliochorial, endotheliochorial or hemochorial, the necessary reduction in interhaemal distance is achieved through extensive tissue remodeling to form chorionic (placental) ridges and corresponding endometrial (uterine) invaginations that increase the surface area for uterine-placental exchange of molecules (Enders, Carter 2004). In association with these structural changes placental and uterine vasculatures undergo significant expansion towards the uterine-placental interface to maximize the juxtaposition of these vasculatures to facilitate exchange between mother and fetus. Angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels from the existing vasculature, is fundamental to this process. Poor transport of nutrients during development can lead to intra-uterine growth restriction of the fetus and long-term metabolic syndrome throughout adulthood (Findlay 1986; Jaffe 2000; Zygmunt et al., 2003). Defective placental and uterine angiogenesis contribute to infertility in several gestational pathologies including gestational diabetes, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia, as well as increased life-long cardiovascular risk (Barker 2004; Lain, Roberts 2002; Mayhew et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2003). Placentation is epitheliochorial in pigs, as the uterine LE remains intact throughout pregnancy. Porcine placental trophoblast directly attaches to the LE, and these epithelia serve as the conduit for maternal hemotrophic support for conceptus growth and development (Renegar et al., 1982). Thus, nutrient exchange between the uterus and placenta must penetrate two epithelial layers, and successful nutrient transfer is highly dependent on new blood vessel formation. As a result, the maternal/fetal interface of pigs is a site of rapid and robust angiogenic blood vessel formation (Ford et al., 1982).

Angiogenic vessels emerge from differentiated adult endothelial cells that line the pre-existing vasculature. However, in 1997, a population of cells was shown to be recruited from the bone marrow to and migrate and incorporate into newly-vascularized tissue where they differentiate into mature endothelial cells, thus forming de novo endothelium. These cells that could be isolated as outgrowths from peripheral blood, were once referred to as angioblasts, and are now known as endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) (Asahara et al., 1997; Kovacic 2008). EPCs continue to be studied in cardiovascular medicine for their therapeutic potential, and a firm relationship has been established between EPCs and pulmonary hypertension, cardiovascular risk, ischaemia and atherosclerosis. Indeed, EPCs incorporate into cutaneous wounds, injured vasculature, myocardial infarcts, vascularizing tumors, and endometrium after induced ovulation to account for between 5–50% of endothelial cells in angiogenic tissues (Hu et al., 2001; Hill et al., 2003; Loomans et al., 2004; Imanishi et al., 2005; Fadini et al., 2007). Although previous studies in women suggest that EPCs may play an important role in maintaining placental and uterine vascular integrity during pregnancy (Buemi et al., 2007; Savvidou et al., 2008; Sugawara et al., 2005a; Sugawara et al., 2005b), little is known about how EPCs are recruited to these tissues during either normal or abnormal pregnancies. Results of the present study we establish that OPN, a major ECM protein found in the uteri and placentae of several mammalian species (Johnson et al., 2003), has the potential to increase incorporation of EPCs into growing vascular networks.

We have isolated, and initially characterized (Figure 1A and 1B), EPCs from the peripheral blood of newborn pigs using a hybrid of previously described methods (Asahara 1997). These pEPCs use integrin receptors to adhere to OPN, because pEPCs bind to OPN that contains an intact RGD integrin binding sequence, but do not bind OPN in which the RGD sequence has been mutated to become nonfunctional (RGD mutated to RAD; Figure 3). Further, this αv integrin-OPN binding results in the assembly of focal adhesions at the base of cultured pEPCs (Figure 1B). We are confident that αv integrin is involved in pEPC binding to OPN in these experiments because when αv function is silenced by siRNA, both the number of pEPCs that bind OPN and the frequency of αv-, vinculin- and paxillin-positive focal adhesions decreases (Figure 4A–C). Vinculin has been implicated in force transmission mechanosensing (Dufour et al., 2013), while paxillin is a signal transduction adaptor protein found at the interface between the plasma membrane and the actin cytoskeleton (Turner 2000). Both vinculin and paxillin regulate force transmission and cell-cell or cell-ECM interaction which could be involved in the recruitment of EPCs into developing vasculature. In support of this, we utilized a novel in vitro model of endothelial cell invasion that has advantages over other in vitro systems in that the endothelial invasion events incorporate multi-cell networks, lumen formation, and angiogenic sprout formation. These are all similar to characteristics of angiogenesis in vivo (Su et al., 2008; Bayless et al., 2009; Su et al., 2010; Dunlap et al., 2010).

Results of the present study demonstrated that OPN binds αv integrin to increase the incorporation of pEPCs into sprouting HUVEC networks (Figures 5 and 6). OPN dose-dependently increased pEPC incorporation in actively invading HUVEC in the three-dimensional matrix model, but when pEPCs in which the αv integrin was silenced were cultured with actively invading HUVEC, they failed to invade (Figure 6A–C). Integrins are critical mediators and regulators of angiogenesis and homeostasis by providing the physical interaction with the ECM necessary for cell adhesion, migration and signaling involved in survival, proliferation and differentiation of cells. Interfering with signaling pathways downstream of integrins, including αvβ3, suppresses angiogenesis (Rüegg, Mariotti 2003). The αv subunit of the integrin family, initially called CD51 antigen, forms multiple integrin heterodimer receptors, including αvβ3, which is present both in normal arteries and in sites of angiogenesis (Hoshiga et al., 1995). Indeed expression of OPN and αvβ3 correlate temporally and spatially with active endothelial proliferation and migration, with highest levels observed at the edge of wounds undergoing angiogenesis (Liam et al., 1995). Results of the present studies delineate these important roles for OPN and αv-containing integrins in regenerating endothelium through the recruitment and incorporation of EPCs into growing blood vessels.

Current dogma suggests that EPCs cultured in endothelial growth media have the ability to form vascular networks or cords on the surface of matrigel substrates. However, we have isolated and cultured pEPCs using a more rigorous 3D model of endothelial network formation and find that pEPCs do not invade and form sprouts unless cultured with mature endothelial cells i.e., HUVEC (Figure 5A and 5B). Our results indicate that pEPCs invade into a collagen matrix only when they can communicate directly with differentiated endothelium actively forming vascular tubes. The mechanism of pEPC-endothelium crosstalk is unknown and begs futher investigation. Silencing of αv integrin does not completely block pEPC incorporation into sprouting HUVEC networks, suggesting that other mechanisms are involved. Previous studies in our laboratory showed that soluble factors secreted by HUVEC do not stimulate pEPC invasion (data not shown), strongly suggesting that pEPC incorporation into the vasculature is the result of direct physical communication between pEPCs and HUVECs. Since direct contact between cell types is required, it is tempting to speculate that junctional communication between HUVECs and pEPCs play a role in crosstalk between the two cell types. Adherens, gap, and tight junctions play a critical role in angiogenic responses (Gärtner et al., 2012; Wallez, Huber 2008; Wallez et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2011). Thus, one or more of these cell-cell signals may be an important component of HUVEC directed pEPC incorporation into new vascular networks.

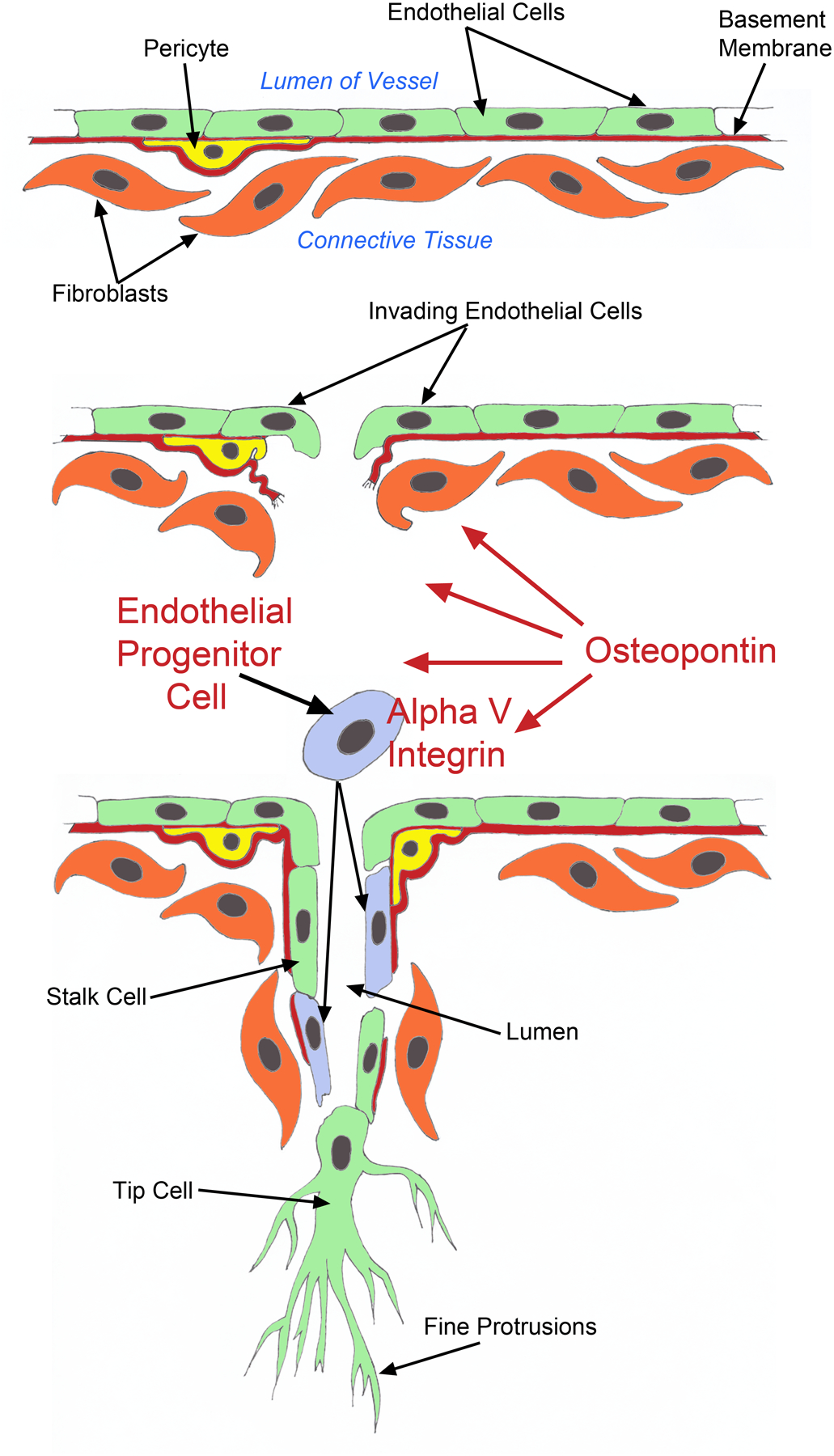

In conclusion, we propose a shift in paradigms of placental angiogenesis to include the recruitment of circulating EPCs through OPN binding to the αv integrin on EPCs. The EPCs then integrate into the growing vasculature to potentially augment the rate and magnitude of angiogenesis (Figure 8). It is intriguing that OPN accumulates within the ECM near blood vessels of the highly vascularized placental allantois, placing this matricellular protein in an appropriate location to function in the manner described (Figure 8)

Figure 8.

OPN in the ECM surrounding placental blood vessels binds to αv integrin on circulating EPCs to stimulate EPC incorporation into the growing vasculature.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R21HD071468-01 to GAJ and KJB, and by a Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine Mini-Grant Award to TTW.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported. Greg Johnson is on the editorial board of Reproduction. Greg. Johnson was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which he/she is listed as an author.

References

- Apparao KB, Illera MJ, Beyler SA, Olson GE, Osteen KG, Corjay MH, Boggess K & Lessey BA 2003. Regulated expression of osteopontin in the peri-implantation rabbit uterus. Biol Reprod 68:1484–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apte U, Banerjee B, McRee R, Wellberg E &Ramaiah S 2005. Role of Osteopontin in Hepatic Neutrophil Infiltration During Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 207 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, Van DerZee R, Li T, Witxenbichler B, Schatteman G & Isner JM 1997. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 275 964–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M, Kearne M, Magner M & Isner JM 1999. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res 85 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D 2004. Developmental Origins of Adult Health and Disease. J Epidemiol Community Health 58 114–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Meininger GA Scholtz J & Davis GE 1998. Osteopontin is a Ligand for the α4β1 Integrin. Journal of Cell Science 111 1165–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Salazar R & Davis GE 2000. RGD-Dependent Vacuolation and Lumen Formation Observed during Endothelial Cell Morphogenesis in Three-Dimensional Fibrin Matrices Involves the αvβ3 and α5β1 Integrins. The Amer J of Path 156 1673–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Kwak H-I & Su S-C 2009. Investigating Endothelial Invasion and Sprouting Behavior in Three-dimensional Collagen Matrices. Nature Protocols 4:1888–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt K, Hall S, Ward C & Melo L 2007. Endothelial Progenitor Cell and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Isolation, Characterization, Viral Transduction. Methods Mol Med 139 197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buemi M, Allegra A, D’anna R, Coppolino G, Crasci E, Giordano D, Loddo S, Cucinotta M, Musclino C & Teti D 2007. Concentration of circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) in normal pregnancy and in pregnant women with diabetes and hypertension. Am J Obstet 196 68.e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdo TH, Wood MR & Fox HS 2007. Osteopontin Prevents Monocyte Recirculation and Apoptosis. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 81 1504–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiado F & Dias S 2012. Endothelial Progenitor Cells and Integrins: Adhesive Needs. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 5 4–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook AC, Tuck AB, McCarthy S, Turner JG, Irby RB, Bloom GC, Yeatman TJ & Chambers AF 2005. Osteopontin induces multiple changes in gene expression that reflect the six “hallmarks of cancer” in a model of breast cancer progression. Mol Carcinog 43 225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby JR, Kaminski WE, Schatteman G, Martin PJ, Raines EW, Seifert RA & Bowen-Pope DF 2000. Endothelial cells of hematopoietic origin make a significant contribution to adult blood vessel formation. Circ Res 87 728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE & Camarillo CW 1993. Regulation of integrin-mediated myeloid cell adhesion to fibronectin: influence of disulfide reducing agents, divalent cations and phorbol ester. J Immunol 151 7138–7150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G & Bayless K 2003. An Integrin and Rho GTPase-dependent Pinocytic Vacuole Mechanism Controls Capillary Lumen Formation in Collagen and Fibrin Matrices. Microcirculation 10:27–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denhardt D & Guo X 1993. Osteopontin: a Protein with Diverse Functions. FASEB J 7:1475–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour S, Mège R & Thiery J 2013. α-catenin, Vinculin, and F-actin in Strengthening E-cadherin Cell-cell Adhesions and Mechanosensing. Cell Adh Migr 7 345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumbauld D, Lee T, Singh A, Scrimgeour J, Gersbach C, Zamir E, Fu J, Chen C, Curtis J, Craig S & García A 2013. How Vinculin Regulates Force Transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110 9788–9793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap KA, Kwak HI, Burghardt RC, Bazer FW, Magness RR, Johnson GA & Bayless KJ 2010. The sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) signaling pathway is regulated during pregnancy in sheep. Biol Reprod 82 876–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall CL, Weiss D, Robinson ST, Alameddine FMF, Guldberg RE & Taylor WR 2007. The Role of Osteopontin in Recovery from Hind Limb Ischemia. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 28 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders AC 1999. Comparative placental structure. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 38 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders AC & Carter AM 2004. What can comparative studies of placental structure tell us? – A review. Placenta 25 (supple. 1) S3–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson DW, Burghardt RC, Bayless KJ & Johnson GA 2009. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1, osteopontin) binds to integrin alphavbeta6 on porcine trophectoderm cells and integrin alphavbeta3 on uterine luminal epithelial cells, and promotes trophectoderm cell adhesion and migration. Biol Reprod 81:814–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadini GP, Schiavan M, Avogaro A & Agostini C 2007. The emerging role of endothelial progenitor cells in pulmonary hypertension and diffuse lung diseases. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2 85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadini GP, Baesso I, Agostini C, Cuccato E, Nardelli GB, Lapolla A & Avogaro A 2008. Maternal insulin therapy increases fetal endothelial progenitor cells during diabetic pregnancy. Diabetes Care 31 808–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea K, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan K, & Moore M 1996. Heterozygous Embryonic Lethality Induced by Targeted Inactivation of the VEGF Gene. Nature 4:380 439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay JK 1986. Angiogenesis in Reproductive Tissues. J Endocrinol 111 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong G, Rossant J, Gertsenstein M & Breitman M 1995. Role of the Flt-1 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase in Regulating the Assembly of Vascular Endothelium. Nature 376 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford S, Christenson R & Ford J 1982. Uterine Blood Flow and Uterine Arterial, Venous and Luminal Concentrations of Oestrogens on Days 11, 13, and 15 After Oestrus in Pregnant and Non-pregnant Sows. J Repord Fertil 64 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JW, Seo H, Burghardt RC, Bayless KJ & Johnson GA 2017. ITGAV (Alpha V Integrins) Bind SPP1 (Osteopontin) to Support Trophoblast Cell Adhesion. Reproduction 153:695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabler C, Chapman D & Killian G 2003. Expression and presence of osteopontin and integrins in the bovine oviduct during the oestrous cycle. Reproduction. 126 721–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Alice Y, Agnihotri R, Vary CPH & Liaw L 2004. Expression and characterization of recombinant osteopontin peptides representing matrix metalloproteinase proteolytic fragments. Matrix Biology 23 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlow JE, Ka H, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Jaeger LA & Bazer FW 2002. Analysis of osteopontin at the maternal-placental interface in pigs. Biol Reprod 66 718–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner C, Ziegelhöffer B, Kostelka M, Stepan H, Mohr F & Dheins 2012. Knock-down of Endothelial Connexins Impairs Angiogenesis. Pharmacol Res 65 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti F & Ruoslahti E 1999. Integrin Signaling. Science 28 1028–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA & Finkel T 2003. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 348 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi KK, Ingram DA & Yoder MC 2008. Assessing Identity, Phenotype, and Fate of Endothelial Progenitor Cells. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 28 1584–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiga M, Alpers CE, Smith LL, Ciachelli CM & Schwartz SM 1995. Alpha-v beta-3 integrin expression in normal and atherosclerotic artery. Circ Res 77 1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov M & Weber C 2004. Endothelial Progenitor Cells: Characterization, Pathophysiology, and Possible Clinical Relevance. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 8 498–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Zhang F, Yang Z, Yang N, Zhang D, Zhang J & Cao K 2001. Combination of simvastatin and EPC transplantation enhances angiogenesis and protects against apoptosis for hindlimb ischemia. J Biomed Sci 15 509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JD, Byron A & Humphries MJ 2006. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Science 119:1901–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Moriwaki C, Hano T & Nishio I 2005. Endothelial progenitor cell senescence is accelerated in both experimental hypertensive rats and patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens 10 1831–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura A, Luedemann C, Shastry S, Hanley A, Kearney M, Aikawa R, Isner JM, Asahara T & Losordo DW 2003. Estrogen-mediated, endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells contributes to reendothelialization after arterial injury. Circulation 108 3115–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KA, Majka SM, Wang H, Pocius J, Hartley CJ, Majesky MW, Entman ML, Michael LH, Hirschi KK & Goodell MA 2001. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J Clin Invest 107 1395–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe RB 2000. Importance of Angiogenesis in Reproductive Physiology. Semin. Perinatol 24 79–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GA, Spencer TE, Burghardt RC & Bazer FW 1999. Ovine Osteopontin: I. Cloning and expression of mRNA in the uterus during the peri-implantation period. Biol Reprod 61 884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GA, Bazer FW, Jaeger LA, Ka H, Garlow JE, Pfarrer C, Spencer TE & Burghardt RC 2001. Muc-1, integrin and osteopontin expression during the implantation cascade in sheep. Biol Reprod 65 820–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Bazer FW & Spencer TE 2003. Osteopontin: Roles in implantation and placentation. Biol Reprod 69 1458–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GA, Burghardt RC & Bazer FW 2014. Osteopontin: A leading candidate adhesion molecule for implantation in pigs and sheep. J Anim Sci & Biotechnol 5 56–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce MM, Gonzalez JF, Lewis S, Woldesenbet S, Burghardt RC, Newton GR & Johnson GA 2005. Caprine uterine and placental osteopontin expression is distinct among epitheliochorial implanting species. Placenta 26 160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelpke SS, Zinn KR, Rue LW & Thompson JA 2004. Site-specific delivery of acidic fibroblast growth factor stimulates angiogenic and osteogenic responses in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res A 71 316–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Erikson DW, Burghardt RC, Spencer TE, Wu G, Bayless KJ, Johnson GA & Bazer FW 2010. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 binds integrins to initiate multiple cell signaling pathways, including FRAP1/mTOR, to support attachment and force-generated migration of trophectoderm cells. Matrix Biol 29 369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacic JC, Moore J, Herbert A, Ma D, Boehm M & Graham RM 2008. Endothelial Progenitor Cells, Angioblasts, and Angiogenesis Old Terms Reconsidered From a Current Perspective. Trends Cardiovasc Med 18 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lain K & Roberts J 2002. Contemporary Concepts of the Pathogenesis and Management of Preeclampsia. Jama 287 3183–3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leali D, Dell’Era P, Stabile H, Sennino B, Chambers A, Naldini A, Sozzani S, Nico B, Ribatti D & Presta M 2003. Osteopontin (Eta-1) and Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 Cross-Talk in Angiogenesis. J Immunol 171 1085–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liam L, Linder V, Schwartz SM, Chamber AF & Giachelli CM 1995. Osteopontin and beta 3 integrin are coordinately expressed in regenerating endothelium in vivo and stimulate Arg-Gly-Asp-dependent endothelial migration in vitro. Circ Res 77:665–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomans CJ, De Koning EJ, Staal FJ, Rookmaaker MB, Verseyden C, De Boer HC, Verhaar MC, Braam B, Rabelink TJ & van Zonneveld AJ 2004. Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of vascular complications of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 53 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K, Abe E, Matsubara Y, Kameda K & Ito M 2006. Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells During Normal Pregnancy and Pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 56 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew T, Charnock-Jones D & Kaufmann P 2004. Aspects of Human Fetoplacental Vasculogenesis and Angiogenesis. III. Changes in Complicated Pregnancies. Placenta 25 127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland RJ, Garza S, Butler WT & Hook M 1995. The mutagenesis of the RGD sequence of recombinant osteopontin causes it to lose its cell adhesion ability. Ann N Y Acad Sci 760 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkin S, Arslan M, Churikov D, Corica A, Diaz JI, Williams S, Bocca S & Oehninger S 2005. In search of candidate genes critically expressed in the human endometrium during the window of implantation. Hum Reprod 20 2104–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama T, Tepper OM, Silver M, Ma H, Losordo DW, Isner JM, Asahara T & Kalka C 2002. Determination of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell significance in angiogenic growth factor-induced neovascularization in vivo. Exp Hematol 30 967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldini A, Leali D, Pucci A, Morena E, Carraro F, Nico B, Ribatti D & Presta M 2006. Cutting Edge- IL-1β Mediates the Proangiogenic Activity of Osteopontin-Activated Human Monocytes. J Immunol 177 4267–4270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura S, Wills A, Edwards D, Heath J & Hogan B 1988. Developmental Expression of 2ar (Osteopontin) and SPARC (Osteonectin) RNA as Revealed by in situ Hybridization. J Cell Biol 106 441–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira E, Tavares KADS, Gomes MTV, Salzedas-Netto AA, Sartori MGF, Castro RA, Fernandes CE & Girao MJBC 2017. Description and evaluation of experimental models for uterine transplantation in pigs. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 15:481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Limana F, Jakoniuk I, Quaini F, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A & Anversa P 2001. Mobilized bone marrow cells repair the infarcted heart, improving function and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:10344–10349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parant O, Dubernard G, Challier J-C, Oster M, Uzan S, Aractingi S & Khosrotehrani K 2009. CD34+ cells in Maternal Placental Blood are Mainly Fetal in Origin and Express Endothelial Markers. Laboratory Investigation 89 915–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renegar RH, Bazer FW & Roberts RM 1982. Placental transport and distribution of uteroferrin in the fetal pig. Biol Reprod 27 1247–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüegg C & Mariotti A 2003. Vascular integrins: pleiotropic adhesion and signaling molecules in vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci 60 1135–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CA & Perry JS 1972. The ultrastructure of pig trophoblast tranplanted to an ectopic site in the uterine wall. J Anat 113:139–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvidou MD, Xiao Q, Kaihura C, Anderson JM & Nicolaides KH 2008. Maternal circulating endothelial progenitor cells in normal singleton and twin pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 4 e411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger DR & Perruzzi Ca 1996. Cell migration promoted by a potent GRGDS-containing thrombin-cleavage fragment of osteopontin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1314 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger DR, Claffey K, Benes J, Perruzzi C, Sergiou A & Detmar M 1997. Angiogenesis Promoted by Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor: Regulation Through α1β1 and α2β1 Integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94 13612–13617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger DR, Perruzzi CA, Streit M, Koteliansky VE, de Fougerolles AR & Detmar M 2002. The α1β1 and α2β1 Integrins Provide Critical Support for Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Signaling, Endothelial Cell Migration, and Tumor Angiogenesis. The Amer J of Path 160 195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi T, Gertsenstein M, Wu X, Breitman M & Schuh A 1995. Failure of Blood-island Formation and Vasculogenesis in Flk-1-deficient Mice. Nature 376 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shijubo N, Uede T, Kon S, Nagata M & Abe S 2000. Vascular endothelial growth factor and osteopontin in tumor biology. Crit Rev Oncog 11 135–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Pfeifer S & Collins J 2003. Diagnosis and Management of Female Infertility. Jama 290 1767–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser CB, Bazer FB, Burghardt RC & Johnson GA 2017. Expression of Progesterone Receptor in the Porcine Uterus and Placenta throughout Gestation: Correlation with Expression of Uteroferrin and Osteopontin. Domestic Anim Endocrinol 58 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su SC, Mendoza EA & Bayless KJ 2008. Molecular profile of endothelial invasion of three-dimensional collagen matrices: insights into angiogenic sprout induction in wound healing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295 C1215–C1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su SC, Maxwell SA & Bayless KJ 2010. Annexin 2 regulates endothelial morphogenesis by controlling AKT activation and junctional integrity. J Biol Chem 285 40624–40634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara J, Mitsui-Saito M, Hoshiai T, Hayashi C, Kimura Y & Okamura K 2005a. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells during human pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 3 1845–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara J, Mitsui-Saito M, Hayashi C, Hoshiai T, Senoo M, Chisaka H, Yaegashi N & Okamura K 2005b. Decrease and senescence of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90 5329–5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C 2000. Paxillin and Focal Adhesion Signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbich C Dimmeler S 2004. Endothelial Progenitor Cells: Characterization and Role in Vascular Biology. Circulation Research 95 343–353.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D, Olmsted J & Marder V 1982. Immunolocalization of von Willebrand Protein in Weibel-Palade Bodies of Human Endothelial Cells. J Cell Biol 95 355–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallez Y, Vilgrain I & Huber P 2006. Angiogenesis: the VE-cadherin Switch. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 16 55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallez Y & Huber P 2008. Endothelial Adherens and Tight Junctions in Cascular Homeostasis, Inflammation and Angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778 794–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FJ, Foss JW, Joyce MM, Geisert RD, Burghardt RC & Johnson GA 2005. Steroid regulation of cell-specific secreted phosphoprotein 1 (osteopontin) expression in the pregnant porcine uterus. Biol Reprod 73 1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Wuj J, Bagchi I, Bagchi M, Sidell N & Taylor R 2011. Disruption of Gap Junctions Reduces Biomarkers of Decidualization and Angiogenesis and Increases Inflammatory Mediators in Human Endometrial Stromal Cell Cultures. Mol Cell Endocrinol 344 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt M, Herr F, Münstedt K, Lang U & Liang OD 2003. Angiogenesis and Vasculogenesis in Pregnancy. Eur J Obstet & Gyn & Reprod Biol 110 S10–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]