Abstract

Tertiary hospitals with expertise in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) are assuming a greater role in confirming and correcting HCM diagnoses at referring centers. The objectives were to establish the frequency of alternate diagnoses from referring centers and identify predictors of accuracy of an HCM diagnosis from the referring centers. Imaging findings from echocardiography, cardiac computed tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) in 210 patients referred to an HCM Center of Excellence between September 2020 and October 2022 were reviewed. Clinical and imaging characteristics from pre-referral studies were used to construct a model for predictors of ruling out HCM or confirming the diagnosis using machine learning methods (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator logistic regression). Alternative diagnoses were found in 38 of the 210 patients (18.1%) (median age 60 years, 50% female). A total of 17 of the 38 patients (44.7%) underwent a new CMR after their initial visit, and 14 of 38 patients (36.8%) underwent review of a previous CMR. Increased left ventricular end-diastolic volume, indexed, greater septal thickness measurements, greater left atrial size, asymmetric hypertrophy on echocardiography, and the presence of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator were associated with higher odds ratios for confirming a diagnosis of HCM, whereas increasing age and the presence of diabetes were more predictive of rejecting a diagnosis of HCM (area under the curve 0.902, p <0.0001). In conclusion, >1 in 6 patients with presumed HCM were found to have an alternate diagnosis after review at an HCM Center of Excellence, and both clinical findings and imaging parameters predicted an alternate diagnosis.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, Center of Excellence, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, echocardiography, genetic screening

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common inherited cardiovascular condition.1 HCM is defined by a left ventricular (LV) wall thickness ≥15 mm in adults,2 or by a wall thickness of 13 to 14 mm with a positive genotype or family history of HCM, in the absence of other causes of hypertrophy.2,3 With an oft-cited prevalence of 1:200 to 1:500 in the global population,2,4 HCM remains significantly underdiagnosed.5,6 HCM predisposes patients most notably to heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and sudden cardiac death (SCD), although there is a wide spectrum of symptoms and disease severity.2,7 Most patients achieve a near-normal life expectancy,8 but delays in identification and management of HCM take an emotional and physical toll on patients.6,9 Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend that evaluation of suspected HCM should include both echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).2,10 Echocardiography typically serves as the initial imaging modality but has limitations in assessing the maximal LV wall thickness.11 Echocardiography can underestimate thickness when 2-dimensional views fail to transect the thickest segment of myocardium or when patients have poor acoustic windows.12,13 Echocardiography can overestimate thickness when 2-dimensional views transect myocardium at non-perpendicular angles or when septal measurements incorrectly include prominent right ventricular moderator bands or trabeculations.11,13 Discrete upper septal thickening, a finding common in older adults, may give the visual appearance of significant septal hypertrophy without necessarily meeting HCM criteria.14,15 CMR creates images that interrogate the entire heart in 3 dimensions, identifying areas of focal hypertrophy potentially missed by echocardiography.13,16 Furthermore, tissue characterization with CMR can distinguish HCM from athlete’s heart,17 chronic hypertension (HTN),18 or other phenocopies such as amyloidosis.19,20 The presence/pattern of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is useful for both diagnostic and prognostic purposes.21–23 Although previous studies have attempted to quantify the prevalence of underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis of HCM,24 our current understanding of the role of advanced imaging and centers with high volume is incomplete. It may be that interpretation of echocardiography and CMR may be more challenging at centers who care for smaller numbers of HCM patients.25 Based on these considerations, the aims of this study were to establish the frequency of change in HCM diagnoses at a high-volume HCM tertiary referral center and to identify predictors of accuracy of diagnosis.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients who presented to establish care at the dedicated, multidisciplinary HCM clinic at the Center of Excellence at the University of Virginia (UVA) for a chief complaint of “HCM evaluation,” “HCM management,” “HCM screening,” and/or “LVH” during the period from September 2020 to October 2022. Patients with a presumed diagnosis of HCM were included; patients with only a family history of HCM who presented for screening but did not carry a personal diagnosis of HCM were excluded.

To confirm or reject the diagnosis of HCM at the referring center, imaging performed before and/or after the referral, including echocardiogram, cardiac computed tomography (CT), or CMR, was reviewed by the HCM subspecialist and HCM cardiac imaging team. Patients not meeting HCM criteria after review of previous imaging and/or imaging obtained after the initial visit were considered to have a diagnosis change. When echocardiography was used, diagnosis was changed based on either the maximal wall thickness or LV morphology. When magnetic resonance imaging was utilized, diagnosis was changed based on maximal LV wall thickness or the LGE pattern. When cardiac CT was used, morphology and ventricular thickness were evaluated.

Echocardiography and CMR reports from referring providers were reviewed for imaging studies conducted before the referral. For the purposes of this review, “referral providers” included clinicians at other hospitals/health systems, and clinicians within the UVA Health System who were not affiliated with the HCM clinic. Referral echocardiography reports included the following imaging parameters: mitral e′, mitral a′, mitral E/A ratio, left atrial (LA) size, LA volume index, interventricular septal diameter in diastole, left ventricle posterior wall thickness in diastole, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, LV ejection fraction, echo morphology (symmetric or asymmetric), and peak gradient. CMR parameters included maximum septal thickness, left ventricle end-diastolic volume and left ventricle end-diastolic volume indexed (LVEDVi), left ventricle end-systolic volume and left ventricle end-systolic volume indexed, and LGE. Septal and maximal wall thickness measurements were re-performed by the HCM subspecialist team at the time of the initial visit if pre-referral imaging was available.

The HCM center’s genetic counselor either primarily interpreted new results or re-reviewed outside results. Genotypes were classified as pathogenic, variants of unknown significance (VUS), or inconclusive.

Demographic data were collected for all patients, including age, gender, patient-reported race, body mass index, presence or absence of a known disease-causing variant, HTN, diabetes mellitus (DM) or prediabetes, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, use of β adrenergic blocking and/or calcium channel blocking agent, presence of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), and New York Heart Association Functional class.

All analyses were performed using R 4.2.3. Baseline characteristics in patients who had the HCM diagnosis confirmed versus those who had the HCM diagnosis rejected were described using the mean and SD for continuous variables and the frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using t tests, whereas categorical variables in the 2 groups were compared using chi-square tests. Multiple imputations were used to complete missing data fields.

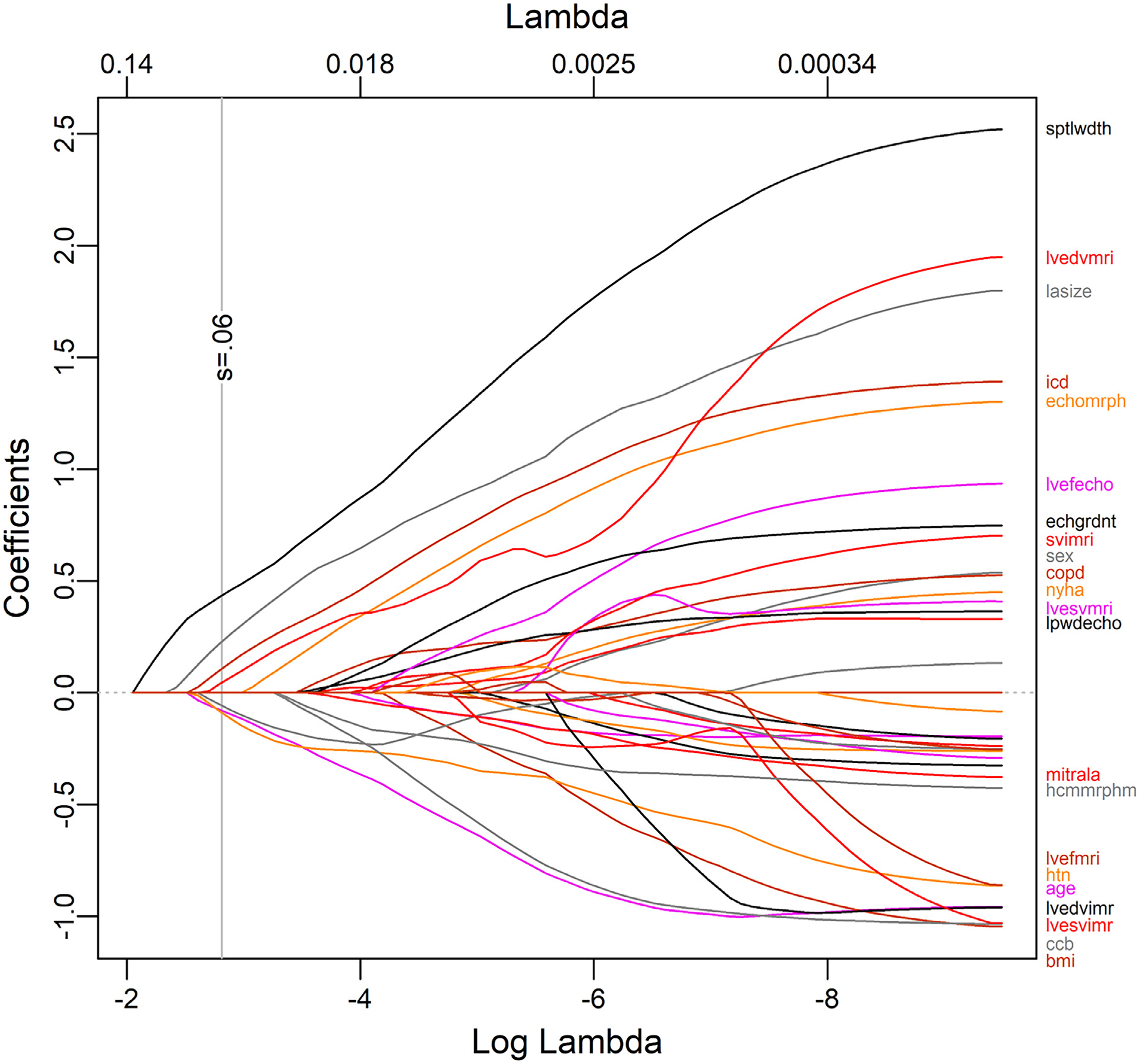

In order to determine clinical and imaging predictors from the referring centers that would result in a confirmation of HCM diagnosis by the tertiary center (binary outcome), logistic regression using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) was performed based on scaled predictors and based on a tuning parameter one standard error higher than the minimum mean cross validation error (0.06).26 With greater values of the tuning parameter (or less negative values of the log of the tuning parameter), the regression coefficients for more covariates shrink to 0. L1 regularization was used for this application to provide robust selection for the best predictors from among several candidate predictors with cross validation. Advantages of the method are automatic feature selection, reduction of overfitting, and robust performance with multicollinearity. Limitations of the procedure include potential bias in the variable coefficients related to the L1 penalty and some difficulty estimating standard errors. For this reason, our approach in this study was to use the LASSO method for feature selection and then calculate the coefficients and standard errors with standard multivariable logistic regression.

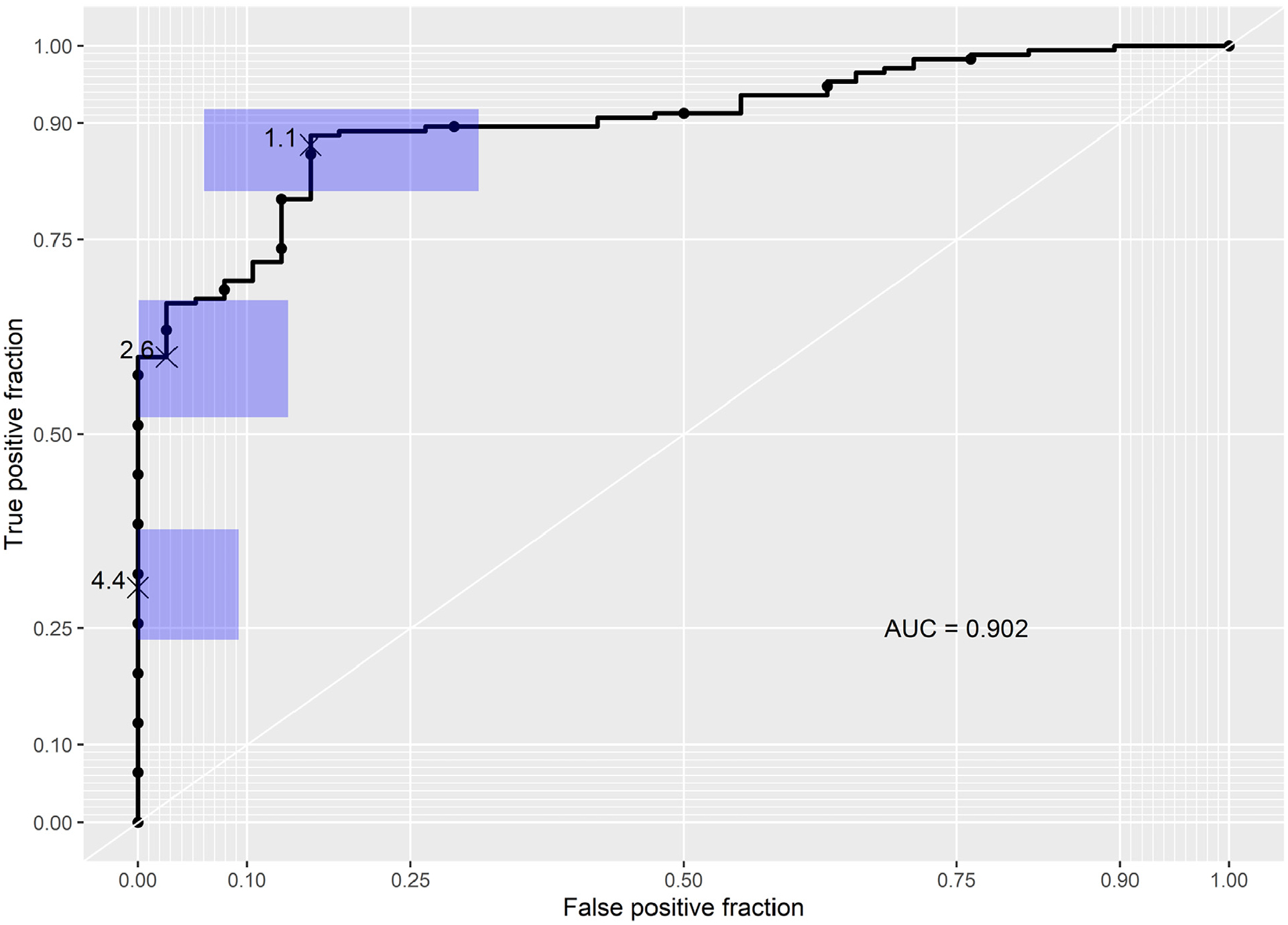

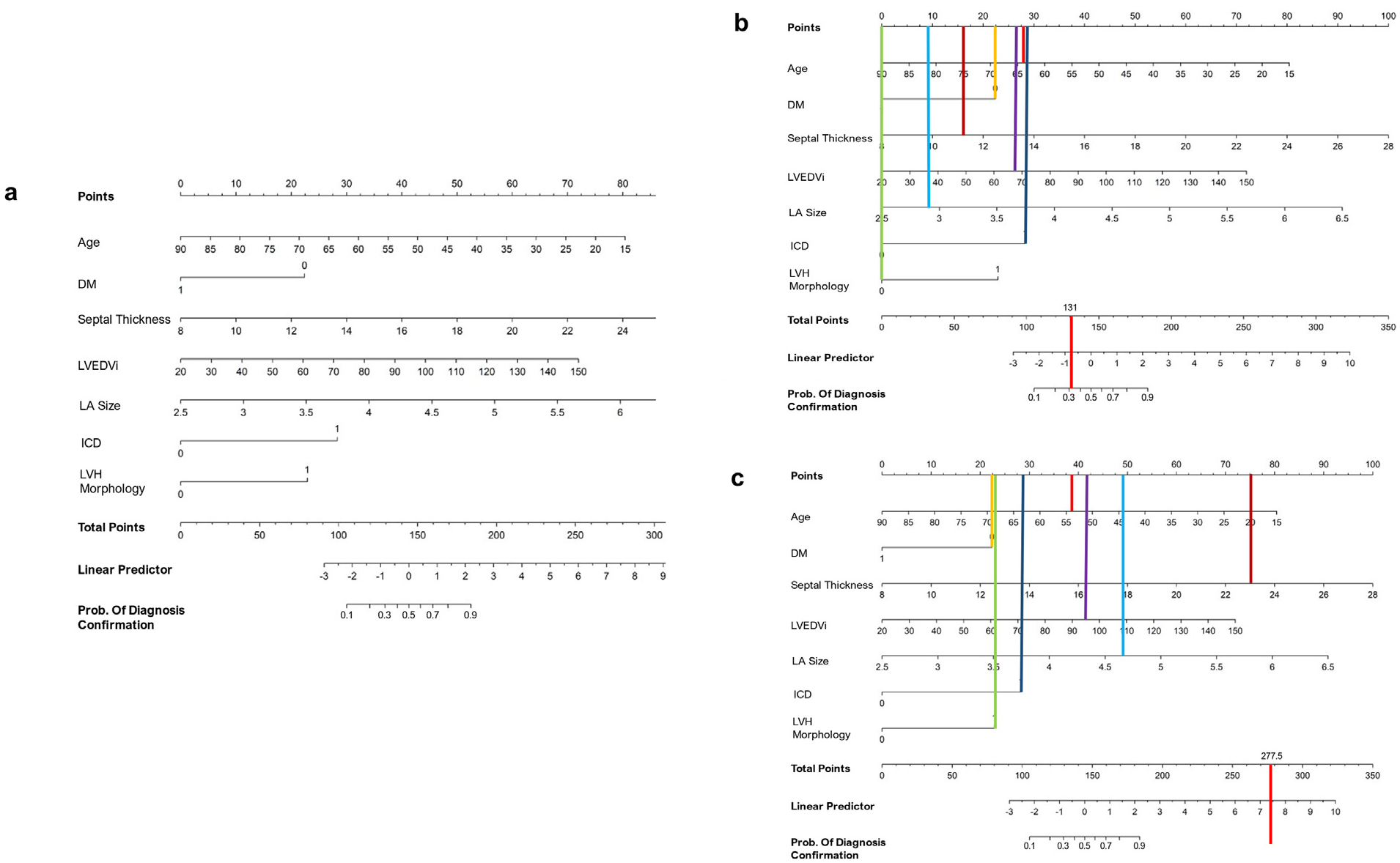

Receiver operating characteristic plots were constructed for the analysis, and the area under the curve (AUC) with associated p value were reported. The cohort was then split into a 70% training set and a 30% test set. The model with covariates identified using LASSO regression was derived from the training set only and then evaluated in the test set. Predictions from the model in the test set for diagnosis confirmation were compared with whether the diagnosis was actually confirmed, and accuracy was reported. A nomogram was then constructed to predict the probability of diagnosis confirmation. In the nomogram, points are determined for the 7 covariate values, leading to a calculation of the total number of points. By dropping a vertical line from total points to the linear predictor and probability rows, the probability of diagnosis confirmation may be determined.

Results

In the cohort of 210 patients with a previous diagnosis of HCM referred to UVA between September 2020 and October 2022, 38 patients (18%) were found to have an alternate diagnosis after comprehensive evaluation. Baseline characteristics of patients with the HCM diagnosis confirmed or changed by the tertiary center are shown in Table 1. Patients with the diagnosis changed were older than those with confirmed HCM (median age 68 and 58, p <0.001) and significantly more likely to have HTN (82% and 57%, p = 0.008) and DM (47% and 24%, p = 0.008). No significant differences were found between the groups regarding body mass index, race, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the use of β adrenergic blocking or calcium channel blocking therapy, or New York Heart Association functional class.

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Demographic | Confirmed HCM n = 172) | HCM excluded (n = 38) | χ2 | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 92 (53.5%) | 13 (34.2%) | 3.888 | 0.049* | |

| Female | 80 (46.5%) | 25 (65.8%) | |||

| Age, n (%) | 4.806 | <0.001* | |||

| 18–34 | 19 (11%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 35–49 | 33 (19.2%) | 2 (5.3%) | |||

| 50–64 | 56 (32.6%) | 12 (31.6%) | |||

| ≥65 | 64 (37.2%) | 24 (63.2%) | |||

| BMI, n (%) | 0.108 | 0.941 | |||

| < 18.5 | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |||

| 18.5–24.9 | 28 (16.2%) | 3 (7.9%) | |||

| 25–29.9 | 56 (32.6%) | 13 (34.2%) | |||

| ≥ 30.0 | 88 (51.2%) | 21 (55.3%) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | 1.354 | 0.508 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 137 (79.7%) | 27 (71.1%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 25 (14.5%) | 8 (21.1%) | |||

| Other (Hispanic, Asian, patient declined) | 10 (5.8%) | 3 (7.9%) | |||

| HTN, n (%) | 98 (57%) | 31 (81.6%) | 6.946 | 0.008* | |

| DM or prediabetes, n (%) | 42 (24.4%) | 18 (47.4%) | 6.947 | 0.008* | |

| CAD, n (%) | 38 (22.1%) | 7 (18.4%) | 0.079 | 0.779 | |

| COPD, n (%) | 9 (5.2%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0.068 | 0.795 | |

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 109 (63.4%) | 23 (60.5%) | 0.020 | 0.886 | |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 46 (26.7%) | 14 (36.8%) | 1.100 | 0.294 | |

| ICD in place, n (%) | 62 (36%) | 3 (7.9%) | |||

| NYHA class 3 or 4, n (%) | 17 (9.9%) | 3 (7.9%) | 0.005 | 0.942 | |

| Known HCM genetic variant, n (%) | 50 (29.1%) | — |

Denotes p-value <0.05.

BMI = body mass index; CAD = coronary artery disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM = diabetes mellitus; HTN = hypertension; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

The frequencies of patients with a diagnosis change according to new imaging studies and reviews of previous imaging studies at the tertiary center are shown in Table 2. Among the 38 patients with rejection of the HCM diagnosis, 17 patients (45%) received a new CMR after their initial visit, and 14 patients (37%) underwent review of previous CMR. For patients who received a new CMR or review of previous CMR, the measurement of the interventricular septum was a common reason cited for changing the diagnosis. One patient (3%) received a new echocardiogram at the time of the initial visit, and an additional 3 patients (8%) underwent review of a previous echocardiogram. One patient received a cardiac CT scan because of incompatibility of the magnetic resonance imaging machine with an indwelling bladder stimulator. One patient received a diagnosis change after receiving a technetium pyrophosphate (PYP) scan, and one patient received a diagnosis change after who underwent cardiac biopsy.

Table 2.

Imaging modality and characteristics used to exclude a diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in patients with a diagnosis change

| Imaging Modality | Patients with a diagnosis change (N=38) | Diagnosis changed by thickness of the interventricular septum | Diagnosis changed by morphology, tissue characterization* and/or LGE pattern* of the LV |

|---|---|---|---|

| New cardiac MRI (%) | 17 (45%) | 15 (40%) | 2 (5%) |

| Review of prior MRI (%) | 14 (37%) | 12 (32%) | 2 (5%) |

| New echocardiogram (%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | — |

| Review of prior echocardiogram (%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) |

| New cardiac CT (%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | — |

| PYP scan, cardiac biopsy (%) | 2 (5%) | — | — |

MRI only.

CT = computerized tomography; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LV = left ventricle; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PYP = pyrophosphate.

Comprehensive imaging review identified alternative etiologies of LV hypertrophy (LVH) in patients with a diagnosis change, including amyloidosis, concentric LVH suggestive of hypertensive cardiomyopathy, and a variety of anatomic variants. Measurement confounders, such as prominent right ventricle trabeculations and/or moderator bands, were commonly elucidated by CMR. The most common changes to management were to optimize other cardiac risk factors and to decrease or discontinue familial screening (Table 3). Of note, some patients had multiple changes to their management. Alternatively, some patients did not require further cardiac follow-up after the exclusion of an HCM diagnosis.

Table 3.

Management changes according to alternative etiology of left ventricular hypertrophy following a diagnosis change

| Optimized other cardiac risk factors | Decreased familial screening | Stopped empiric beta blocker | Undergoing further workup | No change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentric LVH, n=11 (%) | 9 (82%) | 3 (27%) | 1 (9%) | 1 (9%) | 1 (9%) |

| Eccentric LVH, n=20 (%) | 15 (75%) | 7 (35%) | 3 (15%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| Anatomic variants*, n=3 (%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | — | — | — |

| Amyloidosis, n=2 (%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (50%) | — | — | 1 (50%) |

| Normal LV thickness, n=2 (%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (50%) | — | 1 (50%) | — |

3 anatomic variants were reviewed, including prior myocarditis, a sub-aortic membrane, and aortic stenosis.

LV = left ventricle; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy.

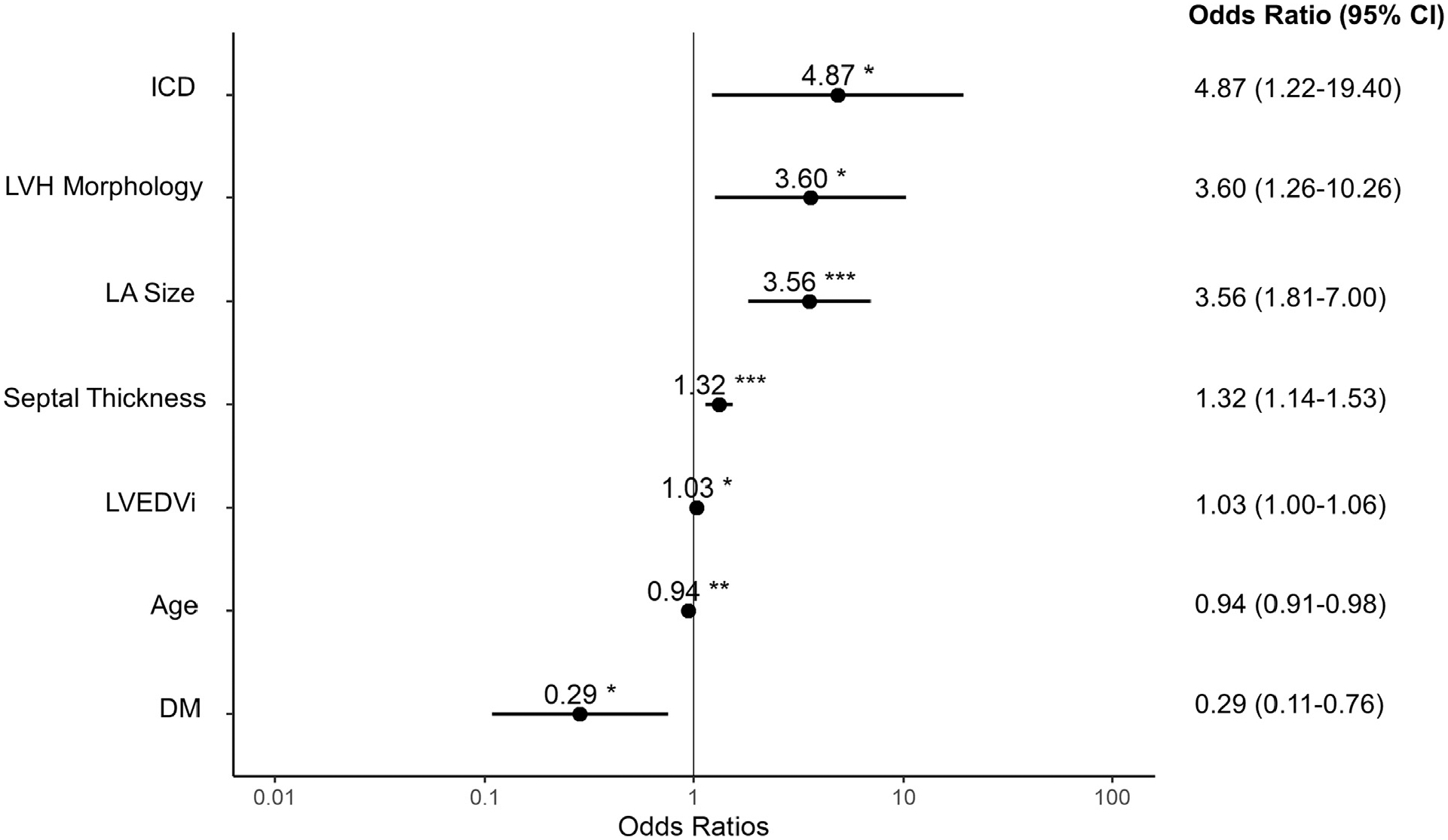

A total of 123 distinct pre-referral CMR reports and 161 echocardiograms were then reviewed to establish clinical and imaging predictors of an alternate diagnosis. Notably, this included 87 patients for whom both previous outside echocardiography and CMR were conducted. For various reasons, no outside imaging reports were available for 16 patients at the time of the initial visit. In the LASSO logistic regression model, 7 covariates were identified as the best predictors of confirmation or rejection of a diagnosis of HCM. Regression coefficients for all covariates considered in the model are shown in Figure 1 as a function of the log of the tuning parameter. Diagnosis confirmation was more likely with a greater septal thickness, greater LA size, greater LVEDVi, ICD presence, and asymmetric LVH morphology characteristics by echocardiography favoring HCM, whereas a diagnosis change was more likely with increasing age and the presence of diabetes. The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are shown in Figure 2. Overall performance based on receiver operating characteristic curve analysis is shown in Figure 3. The AUC was 0.902 (p <0.0001), and the R2 index for the model was 0.50, indicating that the model was a strong predictive tool for identifying patients likely to have HCM ruled out. Agreement between the training and test set was 88.9%, which was consistent with the AUC previously determined.

Figure 1.

LASSO regression of clinical and imaging parameters.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of clinical and imaging parameters associated with a diagnosis change. *OR <1 favors a diagnosis change. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis. The AUC was 0.902 (p <0.0001). AUC = area under the curve.

For the ease of clinical use, a nomogram (Figure 4) was generated with the predictors in the model for predicting the likelihood of confirmation of the diagnosis. The clinical and imaging parameters of a patient with a rejected diagnosis of HCM (Figure 4) and a confirmed diagnosis of HCM (Figure 4) are plotted on the nomogram, with the resultant probabilities of diagnosis confirmation displayed above the probability row.

Figure 4.

Nomogram of clinical and imaging parameters and likelihood of diagnosis confirmation. (A) Nomogram (B) Nomogram applied to a 64-year-old female with a diagnosis change (asymmetric LVH not meeting criteria, septal thickness 11 mm) (C) 54-year-old male with confirmed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and known disease-causing variant. DM = 0 signifies no DM, and 1 indicates the patient has DM; ICD = 1 indicates ICD in place, and 0 indicates no ICD; LVH morphology = 1 indicates eccentric LVH, and 0 indicates concentric LVH.

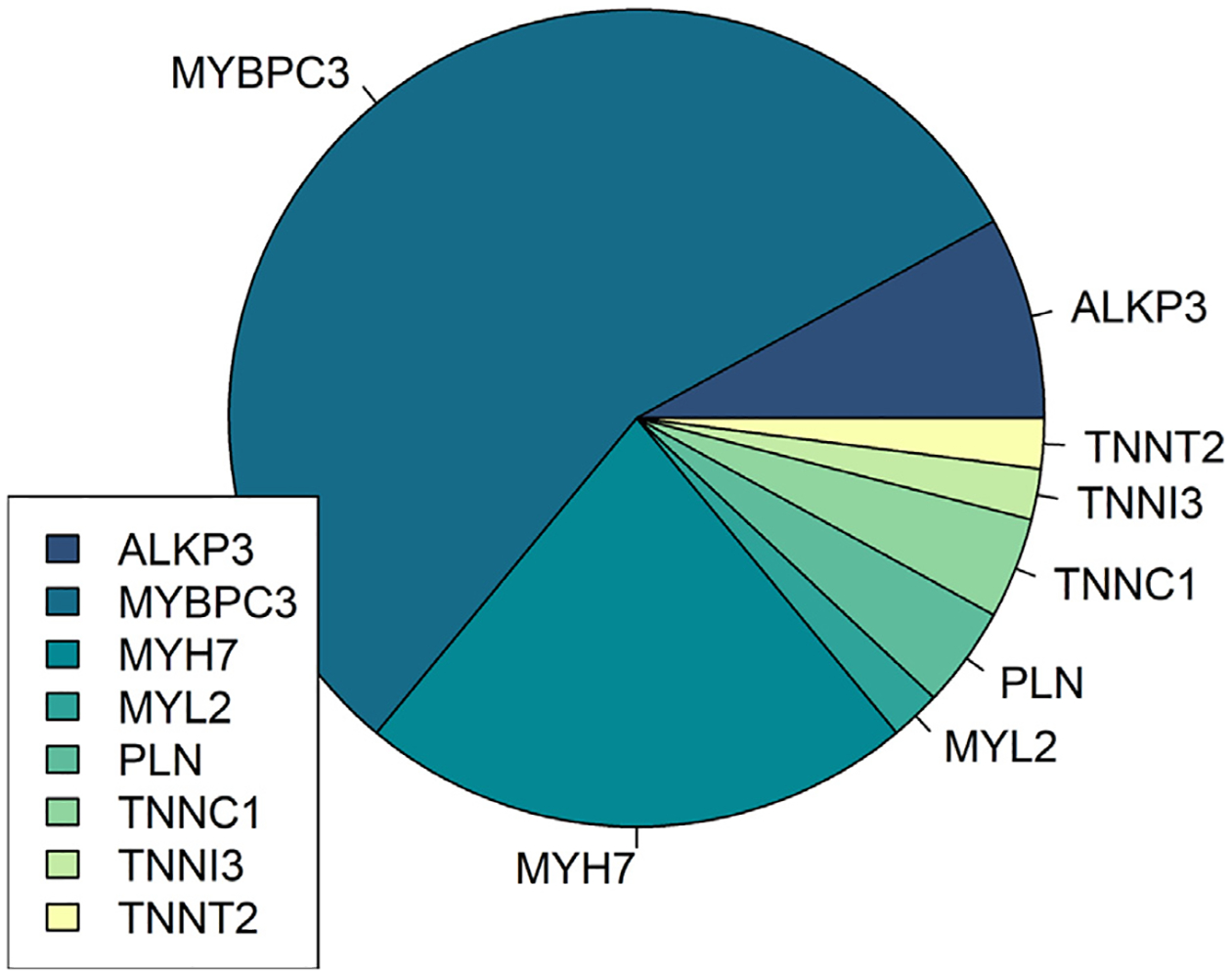

A total of 172 patients (82%) were found to carry an appropriate diagnosis of HCM. Of these, 32 patients (19%) had a positive genotype, and 21 patients (12%) had a VUS before referral. After the initial visit at the HCM clinic, 18 additional patients were found to be genotype positive for a known pathogenic variant (Figure 5), leading to an overall genotype-positive prevalence of 29% (n = 50). Among the 21 patients with a VUS detected on the initial outside genetic assay, 2 were reclassified as pathogenic and 3 were reclassified as benign upon repeat testing. Notably, 7% of patients did not complete genetic testing.

Figure 5.

Frequency of known pathogenic variants in patients with confirmed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (n = 50).

Discussion

In total, 38 of 210 patients (18%), or just over 1 in 6, presenting to establish care for HCM during this 26-month period had an alternative diagnosis after comprehensive evaluation. The female predominance in the diagnosis change group may reflect a larger disparity in symptom presentation and diagnosis of HCM in females.27 The presence of HTN and DM was also more prevalent in patients found not to have HCM, which may correlate with a diagnosis change based on the presence of another systemic disease process. Patients confirmed to have HCM were more likely to have an ICD in place. ICD presence is likely associated with several unmeasured confounders that might increase the likelihood of HCM. Patients with ICDs have been presumably evaluated by multiple cardiology providers who have reached a diagnostic consensus to offer primary or secondary prevention devices. As such, these patients with ICDs may have medical histories or structural morphologies that strongly associate with not just HCM but also with higher-risk disease.

Several clinical and imaging parameters were significantly associated with a diagnosis change. Older age and diabetes were independently stronger predictors of a diagnosis other than HCM. Older age is well-linked to LV remodeling and particularly basal septal wall thickening14,15; thus, a new diagnosis of HCM in a geriatric patient should prompt careful assessment of LV thickness on imaging, particularly CMR. Furthermore, patients with diabetes may be predisposed to septal and ventricular hypertrophy by way of multiple systemic mechanisms, which may produce a phenotypic mimic of HCM.28

A greater LVEDVi was more indicative of HCM. Patients with etiologies of LVH because of high afterload states, such as aortic stenosis or chronic severe HTN, often experience concentric remodeling with smaller cavity volumes. Larger reported septal thickness was also more indicative of HCM. Larger reported septal thickness from pre-referral imaging was less likely to change even with careful reassessment at the referral center, making it less likely that a patient would no longer meet diagnostic criteria. Reported septal thicknesses nearer to 15 mm, on the other hand, might fail to meet HCM criteria after even minor changes on re-measurement. Lastly, a large LA size was indicative of the diagnosis of HCM, reflecting the significant LA dilation often seen in HCM.29

Consistent with the previous analyses, patients of older age or with co-morbid diabetes would receive a lower number of points on the nomogram, with lower overall scores corresponding to a greater likelihood of a diagnosis change. Conversely, greater septal thickness, increased LA size, increased LVEDVi, the presence of an ICD, and asymmetric LVH earned a greater number of points, supporting confirmation of an HCM diagnosis.

CMR was the most powerful tool with respect to a diagnosis change in 31 of 38 patients (82%). Accurate measurement of the septal thickness was sufficient to rule out a diagnosis of HCM in the majority of these cases. Septal thickness is most accurately measured with cine images to prevent inclusion of RV trabeculations or the moderator band in the measurement. For 2 patients presenting with a previous diagnosis of “possible HCM,” review of CMR with the cardiac imager revealed morphologies consistent with LVH but with an LGE pattern not representative of HCM, prompting evaluation for amyloidosis. Subsequent PYP scan in 1 patient and a cardiac biopsy in the other patient were confirmatory of cardiac amyloidosis in these 2 cases. In addition to the need for advanced cardiac imaging techniques in properly evaluating a possible diagnosis of HCM, these cases highlight the need for collaborative clinical expertise in correctly interpreting diagnostic imaging.

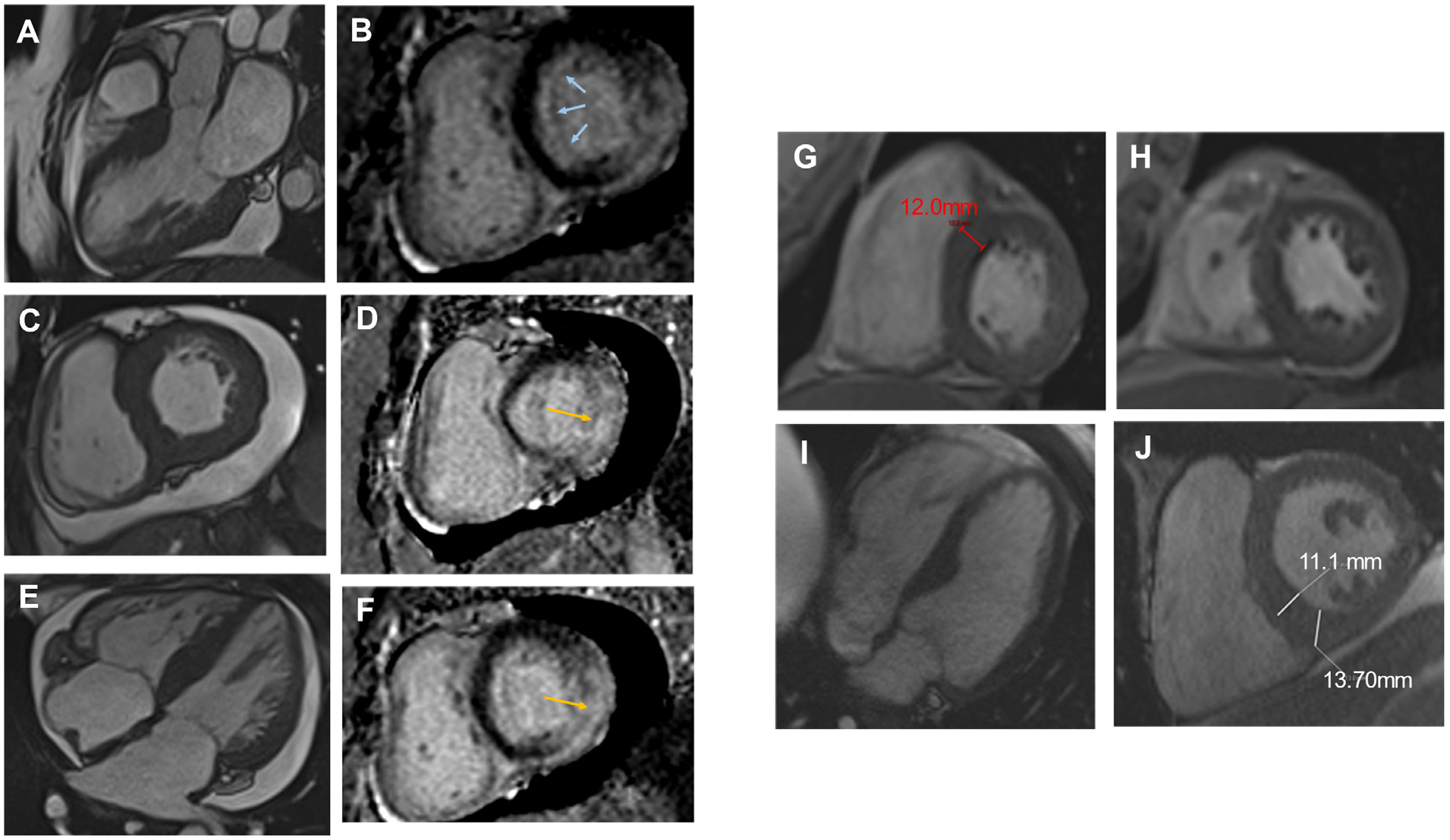

Alternative explanations of LVH obviated the need for further familial screening for several patients, and some were able to discontinue empiric β-blocker therapy. In those found to have hypertensive cardiomyopathy, providers were able to intensify and/or optimize blood pressure management to better control symptoms of LV outflow tract obstruction, if present. One patient was listed for and later received a liver transplant for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency after HCM was definitively ruled out. Representative images and clinical vignettes for patients in whom an alternate diagnosis was found are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Clinical vignettes and CMR studies in patients with a rejected diagnosis of HCM. (A–F) 54-year-old female with a history of ventricular tachycardia complicated by SCD, longstanding HTN, DM, bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome, and a significant family history of heart failure and SCD referred for HCM. CMR was notable for pronounced hypertrophy in the basal anterior and anteroseptal segments with transmural scar in the inferolateral well and midmyocardial scar in the septum and inferior wall, atypical for HCM. This patient eventually underwent PYP, which was negative, but given clinical suspicion of amyloid, cardiac biopsy was obtained and was consistent with cardiac amyloid.(G–H) A 69-year-old female with a history of HTN, prediabetes, NAFLD, family history of SCD presented for HCM with an interventricular septum measuring 1.5 cm by echocardiography. CMR was obtained and revealed concentric LVH without meeting HCM criteria (1.2 cm). This case supported the utility of CMR in borderline cases, as the echocardiogram was measuring moderator band.(I–J) 65-year-old male with a history of a1AT with cirrhosis and bronchiectasis presented for evaluation of HCM after an echocardiography study notable for borderline septal measurement of 1.3 to 1.4 cm. CMR was obtained and did not meet HCM criteria, and genetic testing was normal. This patient was able to proceed with a liver transplant after this evaluation. A1AT = alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency; IVS = interventricular septum; NAFLD = non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Finally, this study identified a 29% prevalence for a known HCM genetic variant in those confirmed to have HCM, which is on the lower end for reported prevalence of sarcomeric mutations in patients with HCM.30 It is possible that the incomplete genetic testing data may have contributed to the slightly lower prevalence of sarcomeric mutation in our population. Additionally, this review excluded patients who presented with a positive genotype but without a phenotype meeting diagnostic criteria, which may have further diluted the genetic yield.

Conclusions

HCM remains a complicated diagnosis, requiring detailed family history, genetic testing, clinical examination, and advanced imaging. This study analyzed the prevalence of HCM in patients referred to a tertiary care center for presumed HCM and identified common parameters that predict the likelihood of confirming or changing a diagnosis of HCM. Furthermore, this work provides a diagnostic framework for patients with a suspected diagnosis of HCM before referral to this tertiary center. Overall, this study demonstrates that center experience, availability of advanced imaging, and appropriate interpretation of those techniques are key to diagnosis. Early referral to a tertiary care center for a suspected diagnosis of HCM may improve patient care by reducing the frequency of potential misdiagnosis and avoiding unnecessary treatment, whereas patients with confirmed HCM may further benefit from early connection to specialized care in line with the current guidelines.

The comprehensiveness of the weekly multidisciplinary HCM clinic at UVA is such that this study likely captured all patients presenting to establish care for presumed HCM during the study period. It is possible that some patients may have been seen outside of the designated HCM clinic, although this would only represent a small number of patients. Heterogeneity in the outside imaging reports may not have accurately represented true cardiac measurements, although this was a known limitation before construction of the predictive model.

There are several potential future directions of this work. The predictive model described here would benefit from validation by applying the nomogram to referrals at separate or multiple tertiary HCM centers. For the cohort of patients with a change in diagnosis, longitudinal follow-up is necessary to ensure they do not “convert” to an HCM diagnosis with progression of LV thickness. Further work is needed to explore the impact of unnecessary treatment in patients with a diagnosis change, including the emotional impact of recurrent family screenings. There are inherent socioeconomic biases in referral patterns to tertiary centers, which limit the generalizability of the results. Analysis of the impact of socioeconomic factors in the wait time and referral patterns to tertiary care centers in cases of suspected HCM might increase health equity.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Sabater-Molina M, Pèrez-Sánchez I, Hern andez del Rincón JP, Gimeno JR. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a review of current state. Clin Genet 2018;93:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, Spirito P, Rakowski H, Towbin JA, Rowin EJ, Maron MS, Sherrid MV. Diagnosis and evaluation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:372–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirino AL, Ho C. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy overview. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1768/ Accessed on November 1, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2013; 381:242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1249–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naidu SS, Sutton MB, Gao W, Fine JT, Xie J, Desai NR, Owens AT. Frequency and clinicoeconomic impact of delays to definitive diagnosis of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the United States. J Med Econ 2023;26:682–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, Bernabò P, Bruzzi P, Maron BJ. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1778–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Casey SA, Haas TS, Chan RHM, Udelson JE, Garberich RF, Lesser JR, Appelbaum E, Manning WJ, Maron MS. Risk stratification and outcome of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy >=60 years of age. Circulation 2013;127:585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owens AT, Sutton MB, Gao W, Fine JT, Xie J, Naidu SS, Desai NR. Treatment changes, healthcare resource utilization, and costs among patients with symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a claims database study. Cardiol Ther 2022;11:249–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, Day SM, Deswal A, Elliott P, Evanovich LL, Hung J, Joglar JA, Kantor P, Kimmelstiel C, Kittleson M, Link MS, Maron MS, Martinez MW, Miyake CY, Schaff HV, Semsarian C, Sorajja P. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.’. Circulation 2020;142: e558–e631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandeş L, Roşca M, Ciupercă D, Popescu BA. The role of echocardiography for diagnosis and prognostic stratification in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Echocardiogr 2020;18:137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagueh SF, Bierig SM, Budoff MJ, Desai M, Dilsizian V, Eidem B, Goldstein SA, Hung J, Maron MS, Ommen SR, Woo A, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. American Society of Echocardiography clinical recommendations for multimodality cardiovascular imaging of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: endorsed by the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:473–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rickers C, Wilke NM, Jerosch-Herold M, Casey SA, Panse P, Panse N, Weil J, Zenovich AG, Maron BJ. Utility of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2005;112:855–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz T, Pencina MJ, Benjamin EJ, Aragam J, Fuller DL, Pencina KM, Levy D, Vasan RS. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and prognosis of discrete upper septal thickening on echocardiography: the Framing-ham Heart Study. Echocardiography 2009;26:247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng S, Fernandes VRS, Bluemke DA, McClelland RL, Kronmal RA, Lima JAC. Age-related left ventricular remodeling and associated risk for cardiovascular outcomes: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baggiano A, Del Torto A, Guglielmo M, Muscogiuri G, Fusini L, Babbaro M, Collevecchio A, Mollace R, Scafuri S, Mushtaq S, Conte E, Annoni AD, Formenti A, Mancini ME, Mostardini G, Andreini D, Guaricci AI, Pepi M, Fontana M, Pontone G. Role of CMR mapping techniques in cardiac hypertrophic phenotype. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10:770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakogiannis C, Mouselimis D, Tsarouchas A, Papatheodorou E, Vassilikos VP, Androulakis E. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or athlete’s heart? A systematic review of novel cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging parameters. Eur J Sport Sci 2023;23:143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sankaranarayanan R, J Fleming E, J Garratt C. Mimics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy − diagnostic clues to aid early identification of phenocopies. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2013;2:36–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syed IS, Glockner JF, Feng D, Araoz PA, Martinez MW, Edwards WD, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Oh JK, Bellavia D, Tajik AJ, Grogan M. Role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;3:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks J, Kramer CM, Salerno M. Markedly increased volume of distribution of gadolinium in cardiac amyloidosis demonstrated by T1 mapping. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013;38:1591–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jao T, Nayak K. Analysis of physiological noise in quantitative cardiac magnetic resonance. PLoS One 2019;14:e0214566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noureldin RA, Liu S, Nacif MS, Judge DP, Halushka MK, Abraham TP, Ho C, Bluemke DA. The diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2012;14:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowin EJ, Maron MS. The role of cardiac MRI in the diagnosis and risk stratification of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2016;5:197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magnusson P, Palm A, Branden E, Mörner S. Misclassification of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: validation of diagnostic codes. Clin Epidemiol 2017;9:403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quarta G, Aquaro GD, Pedrotti P, Pontone G, Dellegrottaglie S, Iacovoni A, Brambilla P, Pradella S, Todiere G, Rigo F, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Limongelli G, Roghi A, Olivotto I. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the importance of clinical context. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;19:601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranstam J, Cook JA. Lasso regression. Br J Surg 2018;105:1348. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubo T, Kitaoka H, Okawa M, Hirota T, Hayato K, Yamasaki N, Matsumura Y, Yabe T, Doi YL. Gender-specific differences in the clinical features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a community-based Japanese population: results from Kochi RYOMA study. J Cardiol 2010;56:314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia G, Hill MA, Sowers JR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: an update of mechanisms contributing to this clinical entity. Circ Res 2018; 122:624–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farhad H, Seidelmann SB, Vigneault D, Abbasi SA, Yang E, Day SM, Colan SD, Russell MW, Towbin J, Sherrid MV, Canter CE, Shi L, Jerosch-Herold M, Bluemke DA, Ho C, Neilan TG. Left Atrial structure and function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy sarcomere mutation carriers with and without left ventricular hypertrophy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017;19:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Driest SL, Ommen SR, Tajik AJ, Gersh BJ, Ackerman MJ. Sarcomeric genotyping in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]