Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the mechanisms involved in the induction of apoptosis in newborn cultured cardiomyocytes by activation of adenosine (ADO) A3 receptors and to examine the protective effects of β-adrenoceptors. The selective agonist for A3 ADO receptors Cl-IB-MECA (2-chloro-N6-iodobenzyl-5-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine) and the antagonist MRS1523 (5-propyl-2-ethyl-4-propyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate) were used. High concentrations of the Cl-IB-MECA (>10 µM) agonist induced morphological modifications of myogenic cells, such as rounding and retraction of cell body and dissolution of contractile filaments, followed by apoptotic death. In addition, Cl-IB-MECA caused a sustained and reversible increase in [Ca2+]i, which was prevented by the selective antagonist MRS1523. Furthermore, MRS1523 protected the cardiocytes if briefly exposed to Cl-IB-MECA and partially protected from prolonged (48 h) agonist exposure. Apoptosis induced by Cl-IB-MECA was not redox-dependent, since the mitochondrial membrane potential remained constant until the terminal stage of cell death. Cl-IB-MECA activated caspase-3 protease in a concentration-dependent manner after 7 h of treatment and more effectively after 18 h of exposure. Bcl-2 protein was readily detected in control cells, and its expression was significantly decreased after 24 and 48 h of treatment with Cl-IB-MECA. β-Adrenergic stimulation antagonized the proapoptotic effects of Cl-IB-MECA, probably through a cAMP/protein kinase A-independent mechanism, since addition of dibutyryl-cAMP did not abolish the apoptosis induced by Cl-IB-MECA. Incubation of cultured myocytes with isoproterenol (5 µM) for 3 or 24 h almost completely abolished the increase in [Ca2+]i. Prolonged incubation of cardiomyocytes with isoproterenol and Cl-IB-MECA did not induce apoptosis. Our data suggest that the apoptosis-inducing signal from activation of adenosine A3 receptors (or counteracting β-adrenergic signal) leads to the activation of the G-protein-coupled enzymes and downstream pathways to a self-amplifying cascade. Expression of different genes within this cascade is responsible for orchestrating either cardiomyocyte apoptosis or its protection.

Keywords: adenosine receptors, apoptosis, image analysis, light and electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, isoproterenol

INTRODUCTION

The multiple physiological effects of adenosine (ADO) are mediated by activation of cell surface adenosine receptors (ARs). At least four subtypes of ARs (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 receptors) are known to exist. The A3 AR is the most recently identified subtype and, like the A1 AR, negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase [1]. Activation of the A3 ARs in the heart has been implicated in therapeutic approaches to vasodilatation [2, 3] and ischemic cardioprotection [4]. Activation of the A3 ARs has a characteristic second messenger profile [5], in which it has been shown to stimulate directly phospholipases C and D [6, 7].

In cultured newborn rat cardiomyocytes, activation of the A3 ARs results in release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores [8]. It has been hypothesized that both A1 and A3 receptors are expressed in cardiomyocytes and that they serve a similar protective function [9]. The A3 ARs are also potentially involved in apoptosis. Intense, acute activation of the A3 receptors exerts a lethal input to cells [10–12]. We have recently demonstrated in neonatal rat cardiomyocyte cultures that high concentrations of the A3 AR agonist IB-MECA, ≥10 µM, induce apoptosis in myocytes [8]. In the present study, we have used the same myocyte culture model to investigate the apoptotic potential of the highly potent and more selective A3 AR agonist Cl-IB-MECA and its recently developed antagonist MRS1523 [13]. The need for selective antagonists is critical, as most effects of high concentrations of A3 agonists have not unequivocally been ascribed to activation of A3 receptors [5]. A2B ARs have been found in cultured fetal chick heart cells [14]. They are positively coupled to adenylyl cyclase and appear to antagonize the antiadrenergic effects of A1 and A3 ARs. Recently, Norton and co-workers [15] proposed that A2A receptors are expressed in rat ventricular cardiomyocytes and that they counteract the antiadrenergic effects of the A1 receptor. IB-MECA is 50-fold selective for A3 versus A1 or A2A receptors [5] and application of high doses of the agonist may stimulate not only A3 receptors. Moreover, there are indications that A3 receptors may not be present in ventricular myocardium in adult rats [9].

Wu et al. [16] reported that atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) induced apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiac cells and that this apoptosis was antagonized by catecholamine-induced increases in cAMP. Taking into consideration the antagonism of β-adrenergic and adenosinergic activation of receptors coupled to G-proteins we have analyzed the protective effects of β-adrenergic stimulation by measuring the apoptosis induced by Cl-IB-MECA in the presence of the nonselective β-adrenoceptor agonist isoproterenol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

The highly selective ADO A3 agonist, Cl-IB-MECA, was gift from the National Institute of Mental Health Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply Program. The selective ADO A3 antagonist MRS1523 was synthesized as described by Li et al. [13]. Indo 1 was from Teflabs (Texas Fluorescence Lab. U.S.A.). DASPMI (4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide) was from Molecular Probes Inc., the selective ADO A2A agonist CGS-21680 HCl was from RBI, and other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company.

Cell culture.

Rat hearts (1–2 days old) were removed under sterile conditions and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove excess blood cells. The hearts were minced to small fragments and then agitated gently in a solution of proteolytic enzymes, RDB (Biological Institute, Ness-Ziona, Israel), which was prepared from a fig tree extract. The RDB was diluted 1:100 in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PBS at 25°C for a few cycles of 10 min each, as described previously [17]. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% horse serum (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel) was added to supernatant suspensions containing dissociated cells. The mixture was centrifuged at 300g for 5 min. The supernatant phase was discarded, and the cells were resuspended again. The suspension of the cells was diluted to 1.0 × 106 cells/ml, and 1.5 ml was placed in 35-mm plastic culture dishes on collagen/gelatin-coated coverslips. The cultures were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air at 37°C. Confluent monolayer exhibiting spontaneous contractions was developed in culture within 2 days. Myocyte cultures were then washed in serum-free medium BIO-MPM-1 (Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel), containing 5 mg/ml glucose, and incubated in this medium for an additional 48 h. After 48 h in serum-free medium experiments were performed by incubating cells in the same medium in the presence of agonists and isoproterenol (5 µM). The growth medium was then replaced every 3 days.

Measurement of contractility.

Culture dishes were placed into a specially designed Plexiglas chamber exposed to a 95% air, 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. The chamber was placed on the stage of an inverted-phase contrast microscope (Olympus). The contractile state of the cardiomyocytes at baseline and in response to interventions was conducted using a video motion detector system, analogous to that described in [8]. Analog tracing was recorded using a oscilloscope joined through a specially designed interface to an IBM computer, and kinetic data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel.

Feulgen procedure.

Cells on coverslips were fixed in EFA (by volume, 75:20:5 of 96% ethanol:40% neutral formol:acetic acid) for 20 min. Rapidly fixed samples were placed in 5 N HCl for 60 min at 24°C to hydrolyze DNA and stained with the Schiff reagent as previously described [8].

Image analysis.

The image analysis was performed with Scan-Array 2 Image Analyzer (Galai, Israel). The analyzer consisted of an Axiovert 135TV microscope (Zeiss, Germany) and a black and white Sony camera, interfaced to an image analysis computer. Morphonuclear parameters were computed as described elsewhere [8]. For analysis of α-sarcomeric actin distribution and its relative quantification images were averaged during acquisition and recorded. A single background image was captured and digitally subtracted from each image of cardiomyocytes. Next, for every image a region containing only cells was selected by outlining with a light pen. The system enables definition and isolation of objects from the surrounding material. This process is referred to as segmentation by thresholding and is based on gray-level analysis. A range of gray levels is chosen corresponding to those within the objects of interest. The gray-level image is converted onto a binary image in which only those objects to be measured remain. There are three level ranges offered by the system: Level 1 (low threshold value, displays in blue pseudocolor), Level 2 (high threshold value, displays in red pseudocolor), and the background range (actual gray level). In the present work, the system described the following parameters: area, the morphometric parameter, which corresponds to the area of the objects profile and a densitometric parameter, and IOD, the integrated optical density, related to the total DNA content [8].

α-Sarcomeric actin assay.

For immunohistochemical demonstration of α-sarcomeric actin, mouse monoclonal antibody and goat anti-mouse biotinylated immunoglobulin conjugated with extrAvidin peroxidase. 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole was used as the chromogen [8].

Monitoring mitochondrial retention of DASPMI.

Living cells grown on round coverslips were exposed to DASPMI [18], dissolved in PBS at a final concentration 10 µg/ml for 15 min. The coverslips were then washed and mounted on chambers containing dye-free medium. DASPMI fluorescence was excited at 460 nm, and the emission wavelength was 540 nm. The digital ratio images were calculated using the Scan-Array 2 image analyzer. For the calculation of redox states the fluorescence values of individual mitochondria, expressed as the average gray value of a selected region of interest, were determined from the unprocessed digital video images [19].

Caspase-3 (CPP32) protease activity.

CPP32 protease activity was detected using ApoAlert CPP32 colorimetric assay kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.), based on spectrophotometric detection of the chromophore p-nitroanilide (pNA) after cleavage from the labeled substrate DEVD-pNA, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were harvested, washed in PBS, and sedimented. Extracts were prepared by adding ice-cold lysis buffer containing 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 100 mM sodium vanadate, 0.2 mM PMSF, 1% NP-40 in PBS. Samples containing 20 µg of protein were run on polyacrylamide–SDS gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose filters. The nitrocellulose sheet was immersed in blocking solution containing 2% bovine serum albumin and 0.02% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 18 h at 4°C. The sheet was then transferred to a blocking solution supplemented with mouse monoclonal anti-Bcl-2 (Transduction Laboratories). The nitrocellulose sheet was incubated overnight at 4°C and then washed three times with 0.02% Tween 20 in TBS. As a secondary detection antibody we used peroxidase labeled anti-mouse antibody and detection was performed using the ECL Western blotting procedure as described by the supplier (Amersham). Light emission was detected by an exposure to Fuji RX Medical X-ray film.

Electron microscopy.

The cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate for 1 h, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer for 1 h, en bloc [20], and stained in 0.5% uranyl acetate. The cultures were dehydrated in an ascending series of alcohols, infiltrated in Epon–Araldite epoxy resin, and heat polymerized. En face (with respect to the culture substratum) sections were cut on an LKB ultramicrotome, poststained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined in a JEOL-1200 transmission electron microscope at an operating voltage of 80 kV.

Intracellular Ca measurements.

Intracellular free calcium concentration, [Ca2+]i, was estimated from indo-1 fluorescence using the ratio method described by Grynkiewicz et al. [21]. The cardiac cells grown on a coverglass were transferred to a chamber on the stage of Zeiss inverted microscope filtered with UV epifluorescence illumination. Indo-1 was excited at 355 nm and the emitted light was then split by a dichroic mirror to two photomultipliers (Hamamatsu, Japan) with input filters at 405 and 495 nm. The fluorescence ratio of 405/495 nm, which is proportional to [Ca2+]i, was monitored.

RESULTS

Morphological Study of Cl-IB-MECA-Induced Apoptosis

To test the ability of Cl-IB-MECA to induce apoptosis in cardiac myocytes, cultures of neonatal myocytes were treated with 10–30 µM agonist for 48–72 h on day 4 of culture. A time course of cardiomyocytes death in treated cells was evaluated by staining cells immunohistochemically with α-sarcomeric actin antibody and hematoxylin counterstaining. Under control conditions myocyte cultures contained a low percentage of dead cells. The structural appearance of control cells is depicted in Fig. 1A. Most cells were flattened, strands of well-organized cross-striated myofibrils ran in various directions, and the myocytes possessed one or two nuclei. Individual myofibrils densely packed only around the nucleus. Myofibrils appeared to be detaching from one another and no longer in register, with the absence of myofibrils at the cell periphery. Myocytes treated with Cl-IB-MECA for 24 h had begun to lose their flattened shape, to shorten, and to cease contracting (phase-contrast observation). These cells were rounded but remained attached to the substrate and maintained cellular integrity; propidium iodide, a marker for identification of necrotic cells [16, 22], did not penetrate the cells (Fig. 1B). After 48 h of treatment with Cl-IB-MECA a concentration-dependent apoptotic transformation of myocytes was evident. A concentration of 30 µM agonist caused complete destruction of the cultured myocytes (Fig. 1C). Only very shortened cells or particles of the myocytes with remaining sarcolemma were observed, with many containing pycnotic or fragmented nuclei. In these cells punctuate α-sarcomeric actin staining patterns remained of the once extensive actin fibril. Most myocytes were not attached to the substrate and formed a so-called “floating population” [23] of very small cells, which maintained their membrane integrity as determined by propidium iodide exclusion. After treatment with 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA more cardiomyocytes remained attached to the substrate (Fig. 1D). All myocytes were shortened, myofibrils were separated and no longer in register, and in many cells only short segments of myofilaments remained. Typical morphological signs of apoptosis were obvious: shrinking, extensive intracellular degeneration, condensation of cytoplasm, and fragmentation and condensation of the nucleus while the sarcolemma remained intact (Fig. 1D).

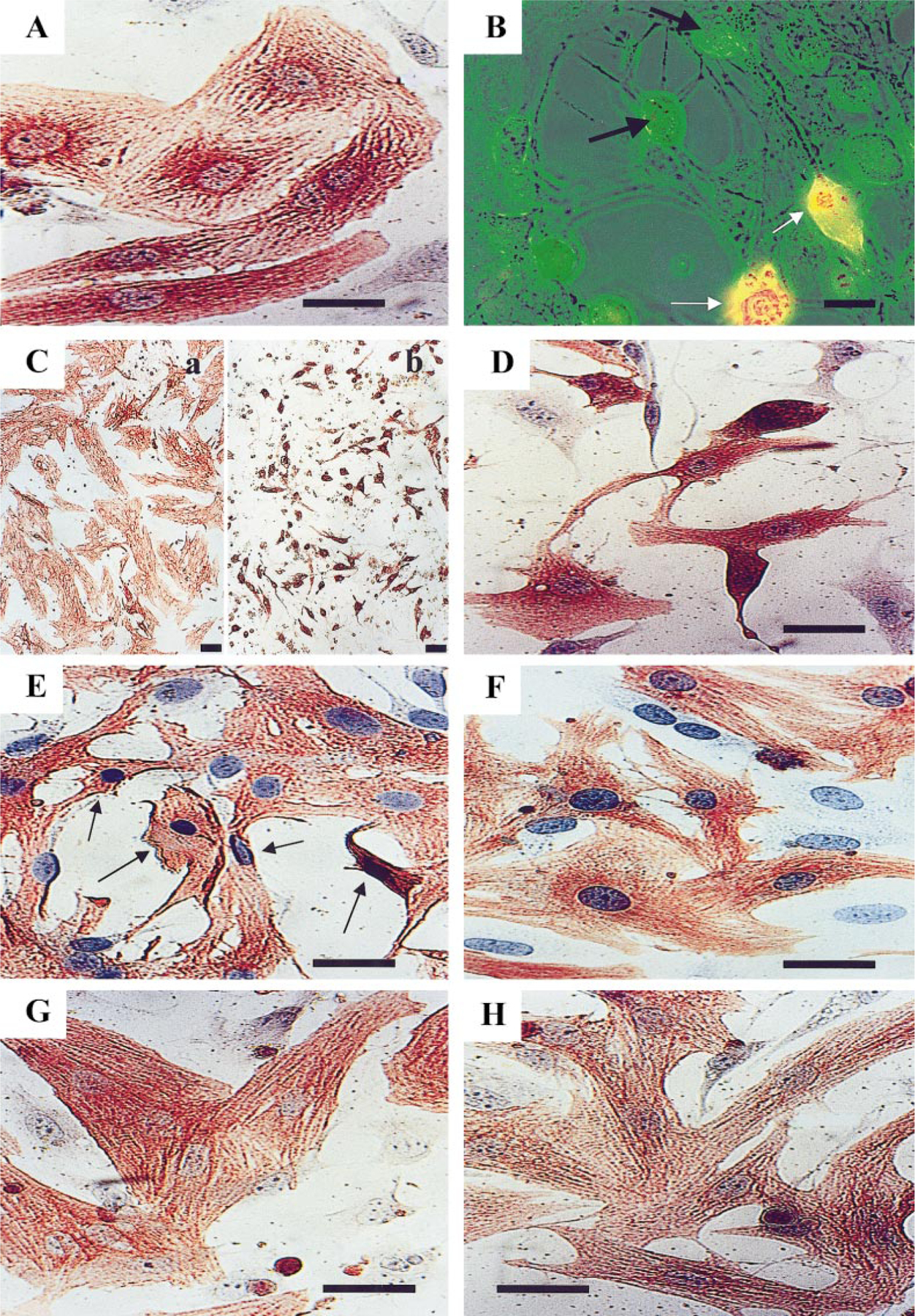

FIG. 1.

Light micrographs of cultured cardiac cells after exposure to Cl-IB-MECA. (A) Control cells cultured in serum-free medium. Cross-striated myofibrils arranged in perinuclear area of the cell. (B) Effect of 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA on cardiocytes after 24 h of exposure. Shortening and shrinkage of viable cells (exclude propidium iodide, black arrows). Propidium iodide-stained cells were scored as necrotic (white arrows). Combined visualization by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy. (C) Effect of 30 µM Cl-IB-MECA after 48 h of treatment. (Ca) Control, untreated cardiocytes. (Cb) Complete destruction of cardiomyocytes; only very shortened cells or particles (apoptotic bodies) were observed. (D) Effect of 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA after 48 h of treatment. (E) Effect of 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA after 2 h of treatment (arrows show apoptotic cells). (F) Cardiocytes treated with the antagonist MRS1523 before A3 agonist. The antagonist MRS1523 prevents the toxic effect of Cl-IB-MECA (20 µM for 2 h). (G) Morphology of cardiomyocytes 2 days incubated with 5 µM isoproterenol. (H) Reduction of apoptosis by isoproterenol in Cl-IB-MECA-stimulated cells. A and C–H, immunohistochemical staining of α-sarcomeric actin and counterstaining with hematoxylin. No counterstain in Ca and Cb. Bars, 10 µm. Ca and Cb, bars, 30 µm.

To establish whether Cl-IB-MECA-induced apoptotic cell death was mediated by the activation of the A3 AR, cultured cardiomyocytes were pretreated with the A3 AR antagonist MRS1523 (1 µM) and subsequently exposed to 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA for 2 or 48 h. MRS1523 prevented the apoptotic effect of the agonist, but only following exposure to 2 h in serum-free medium (Figs. 1E and 1F). In contrast, the antagonist failed to prevent the toxic effect of Cl-IB-MECA after long-term (24- to 48-h) exposure.

Effects of β-Adrenergic Stimulation

To analyze the effects of β-adrenergic stimulation on cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by Cl-IB-MECA, the cardiocytes were exposed to 5 µM β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol prior to Cl-IB-MECA treatment. Figure 1G depicts the morphology of cardiomyocytes 2 days following exposure to isoproterenol alone under identical culture conditions. Myofibrils within these cells were elongated, densely packed, and distributed throughout the thickness of the cell. Myofibrils demonstrated the typical striated, registered pattern. Nuclear phenotypes were clearly characterized by a few small granules of heterochromatin against a pale background. Treatment with isoproterenol significantly reduced the apoptosis in Cl-IB-MECA-stimulated cardiomyocytes. The interior of these cells showed that individual myofibrils were elongated and densely packed and uniformly distributed in the cells (Fig. 1H).

The myofibril degeneration in collapsed cardiomyocytes after exposure to Cl-IB-MECA and the protective effects of β-adrenergic stimulation were quantitatively analyzed using a Scan Array image analysis system. Total area of the cardiomyocyte was compared with area of dense α-sarcomeric actin-immunoreactive myofibrils. Areas of spreading cardiomyocytes were determined from a video image by an automated area measurement function. The captured image of the cell was densitometrically thresholded to include cell area and the dense myofibrils (red and blue pseudocolors) and exclude the brighter background area (see Materials and Methods). The thresholded areas were then automatically quantitated in square micrometers. Figure 2A shows the quantitation of the cells and cellular myofibrils area in bar graph form. Figures 2C–2E depict the distribution of cell area and myofibrils area in single cardiomyocytes treated with Cl-IB-MECA and the protective activity of isoproterenol.

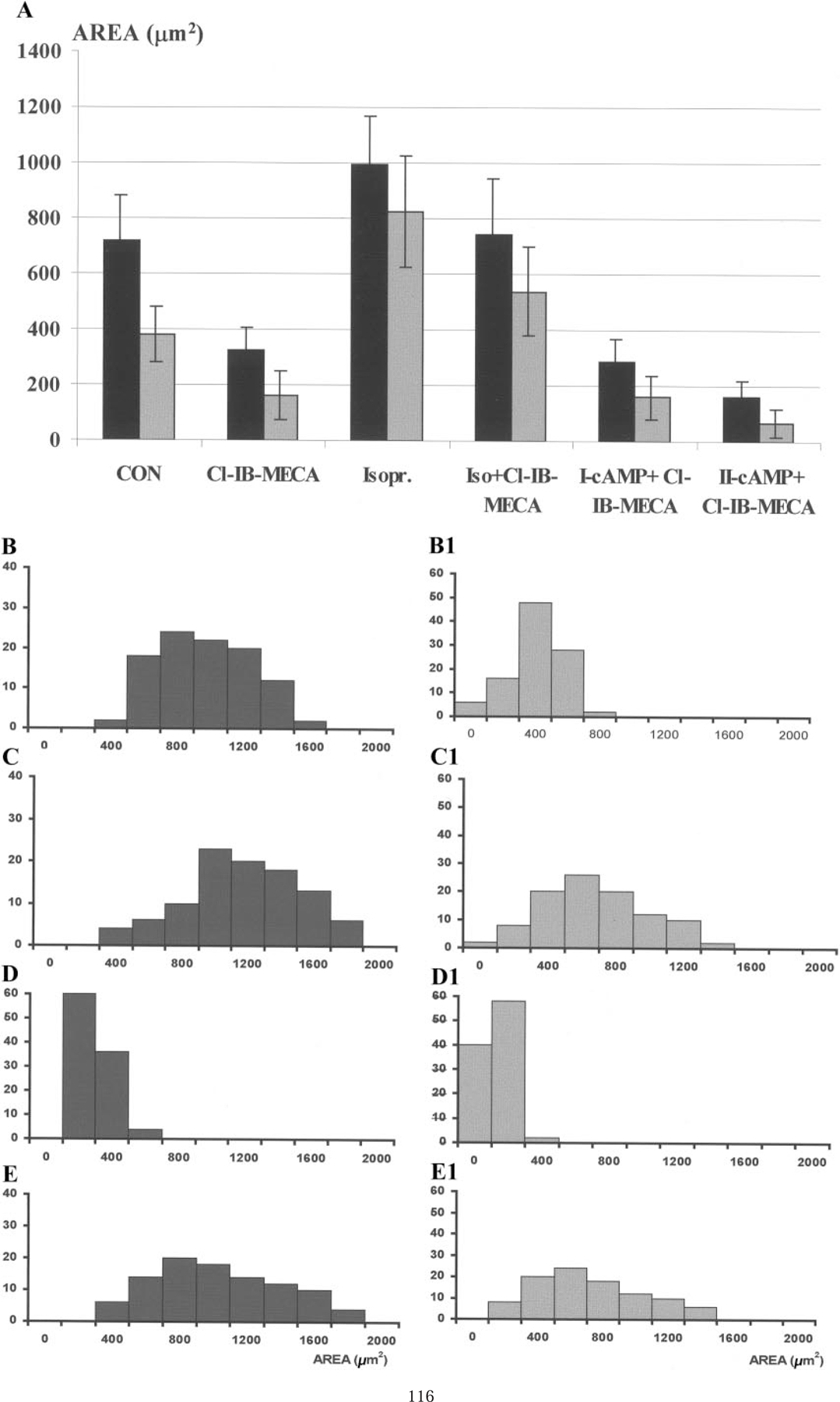

FIG. 2.

Histograms of cardiomyocytes area and myofibrils area after various treatments. (A) Cardiomyocyte area (black bars) and myofibril area (gray bars) following treatment with Cl-IB-MECA (20 µM), isoproterenol (5 µM), dibutyryl-cAMP, I- (1 µM), or II- (200 µM). (B–E) Histograms of cardiac cells distribution in control (B), isoproterenol (C), Cl-IB-MECA (D), Cl-IB-MECA, and isoproterenol (E) cultures. (B1–E1) distributions of intracellular myofibrillar area in the cultured cardiomyocytes. Y axis, cell number.

The average area of control spreading myocytes was 720 ± 160 µm2, and the area of myofibrils within these cells was 380 ± 100 µm2 (Fig. 2B). β-Adrenergic stimulation with isoproterenol stimulated myocyte growth, with the mean value of cardiomyocyte area after 48 h of stimulation being 996 ± 120 µm2 and the myofibril area increased to 825 ± 200 µm2 (Fig. 2C). After 48 h of exposure to 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA a decrease in myocytes area was pronounced (220 ± 80 µm2), and the area of α-sarcomeric actin containing segments in these cells was 164 ± 89 µm2 (Fig. 2D). Isoproterenol abolished cardiomyocyte degeneration after Cl-IB-MECA treatment. Mean value of cardiomyocyte area under these conditions was 741 ± 196 µm2, and myofibril area was 540 ± 160 µm2, which surpassed control values (Fig. 2E). Activation of protein kinase A in the antiapoptotic effect of isoproterenol was investigated by treating the cardiocytes with the cell permeable analogue dibutyryl cAMP (Bt2cAMP). Concentrations of Bt2cAMP 1–200 µM did not prevent the apoptotic effect of Cl-IB-MECA (Fig. 2A). On the contrary, concentration (100–200 µM) increased the apoptotic activity of the ADO agonist. These results suggest that the anti-apoptotic effect of β-adrenergic stimulation in A3 AR-mediated apoptosis is not via activation of protein kinase A, but likely requires calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum [8].

Feulgen Staining

Histograms of the distribution of integrated optical density (IOD) of Feulgen-stained cardiomyocytes versus cell number are shown in Figs. 3A–3D. Nuclei stained by the Feulgen technique show four distinct populations. For each population of diploid and tetraploid cells there is a constant value for IOD despite a wide variation in nuclear size. In control cultures individual interphase nuclei, the G0/G1 population covered 1.8–2.4 C of DNA content and was the predominant population (>90%). A second peak was recorded in the range of 2.5–4.9 C, corresponding to cells in S-phase and tetraploid cells (G2/M). The amount of nuclei with hypodiploid DNA content in control cultures was no more than 2–3% (Fig. 3A). Exposure of myocytes to the agonist for 48 h led to increased programmed cell death. Features of apoptotic nuclei such as condensation, compacting, and margination of nuclear chromatin were accompanied by a disappearance of the structural framework of the nucleus and nuclear breakdown. Histograms of DNA contents demonstrated a considerable increase in the hypodiploid peak over control cells and maintaining of cells in S- and G2/M-phases (Fig. 3B). Incubation of myocytes with 5 µM isoproterenol for 48 h did not changed the level of hypodiploid cells but decreased cells with more than 2C DNA content (Fig. 3C). Incubation of the cardiomyocytes treated with 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA in the presence of 5 µM isoproterenol caused a DNA distribution similar to control cells; only a small increase in hypodiploid peak was obtained (Fig. 3D). All preparations, while subjected to the Feulgen reaction and subsequent dehydration steps, were processed together for uniformity.

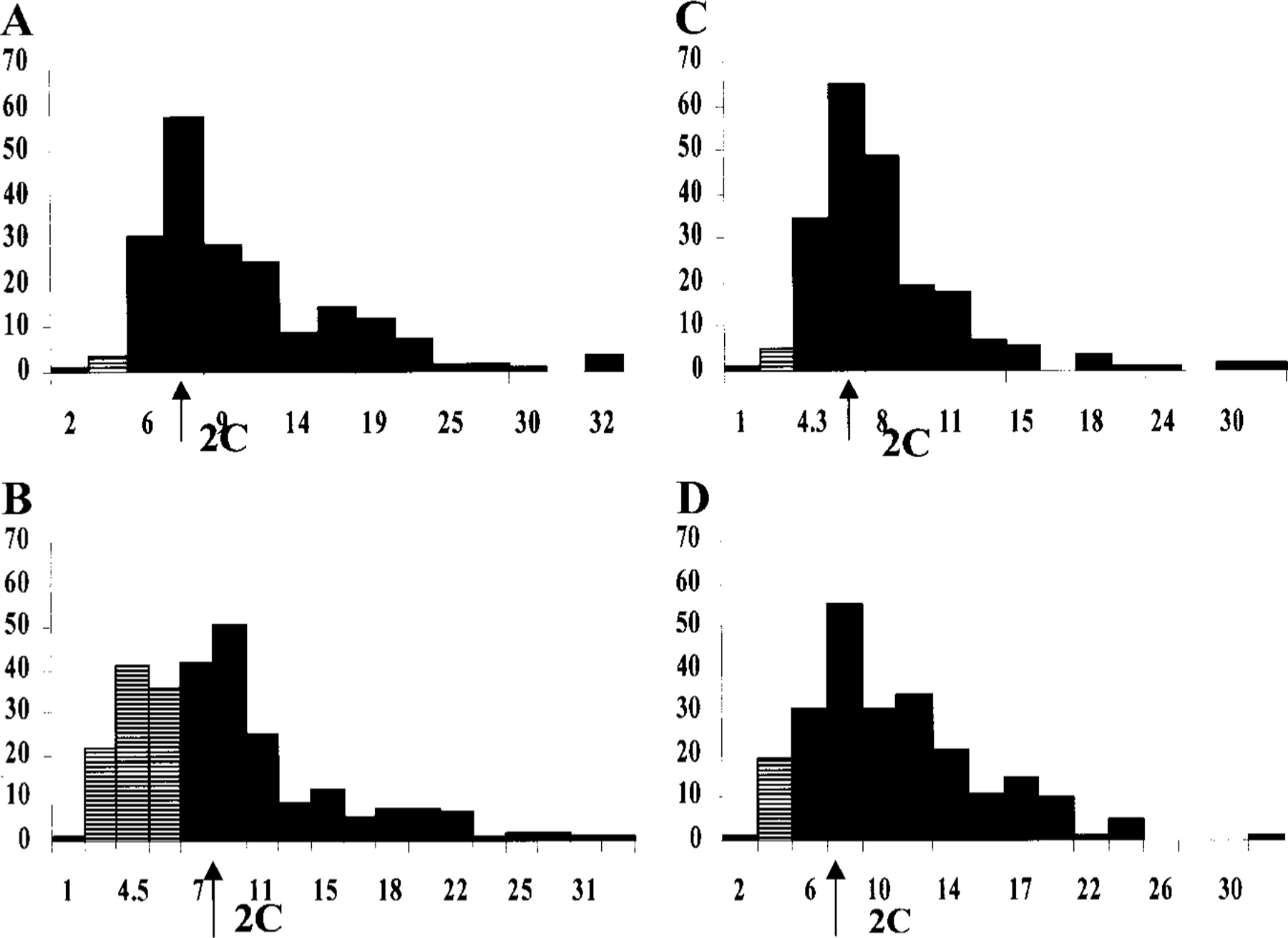

FIG. 3.

Histograms of DNA content by image analysis of Feulgen stained nuclei. ( x) Arbitrary units of IOD; ( y) frequency of cells; 2C, diploid content of DNA (arrow); crossed bars, hypodiploid nuclei. (A) Control. (B) 48-h incubation with 5 µM isoproterenol; slight increase in hypodiploid DNA content. (C) 48-h treatment with 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA; considerable increase in hypodiploid DNA transformation. (D) Protective effect of isoproterenol on Cl-IB-MECA-induced damage in cardiocytes DNA content.

Mitochondrial Redox State

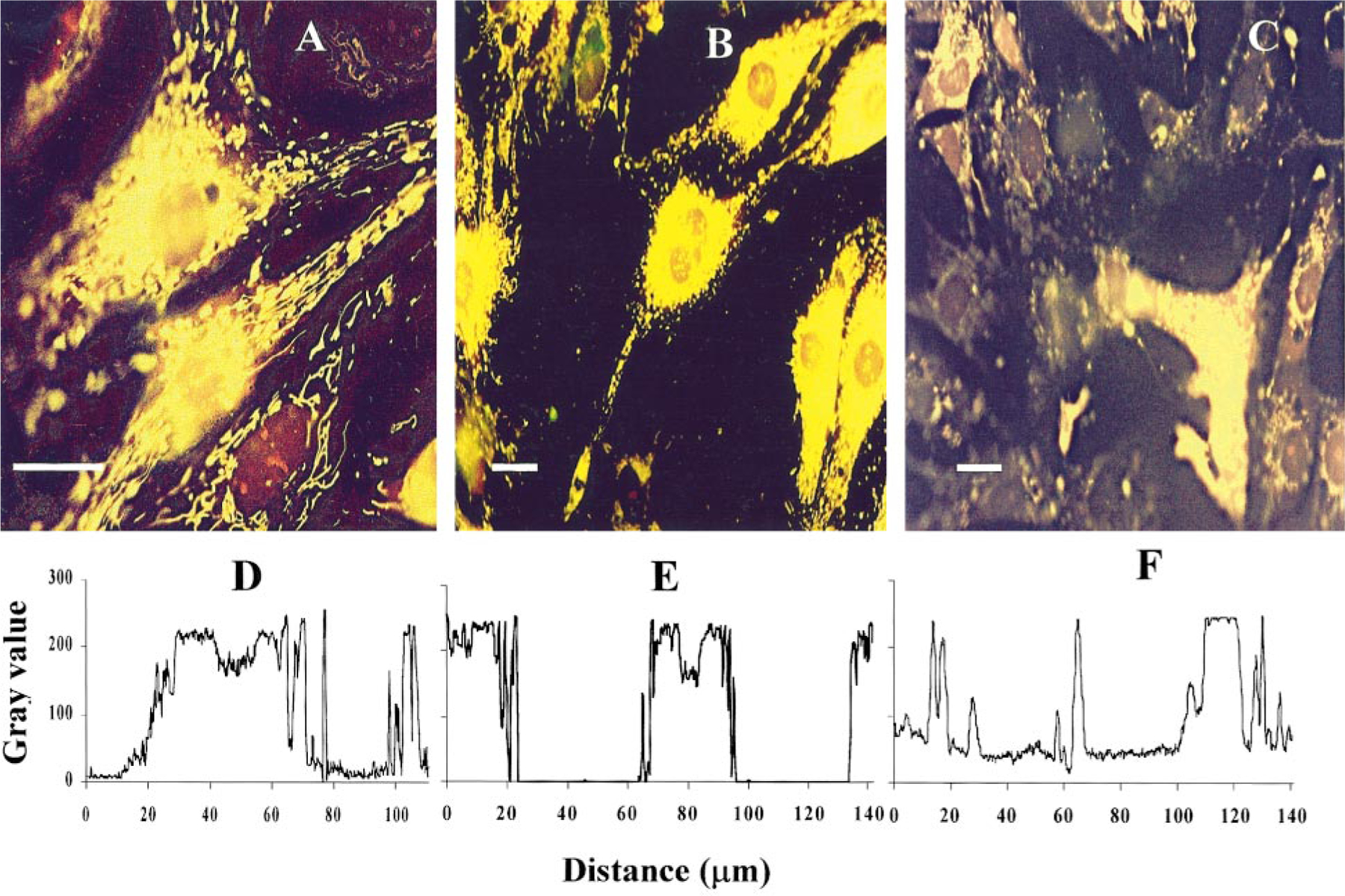

Cardiomyocytes exposed to Cl-IB-MECA were stained with the fluorescent dye DASPMI to monitor mitochondrial membrane potentials [18, 19]. Figure 4 shows the DASPMI fluorescence of cultured cardiomyocytes. In control cells (Fig. 4A) longitudinally oriented, stretched mitochondrial patterns were revealed in subsarcolemmal sections of the cytoplasm and oval mitochondria in perinuclear and intermyofibrillar region. Treatment for 48 h with 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA, leading to loss of cells and most of the organelles, did not cause a decrease in fluorescence intensity of mitochondria or dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Figs. 4B and 4C). To quantify the metabolic response of the mitochondria we extracted gray value histograms from the digital images from Scan Array image analysis system. These histograms, presented in Figs. 4D–4F, quantitatively show the preservation of higher fluorescence intensity associated with the sub-nuclear region of cells in spite of degenerative changes in the cardiomyocytes. These results indicate that the mitochondria are not the prime target of the agonist.

FIG. 4.

Mitochondrial fluorescence of DASPMI in Cl-IB-MECA-treated cardiocytes. (A) control. (B, C) Cells treated for 48 h with 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA. Intensity of DASPMI fluorescence did not change until the terminal state of cell death. (D–F) Histograms of gray-level distribution show the presentation fluorescence intensity of A–C, respectively. Bar, 10 µm.

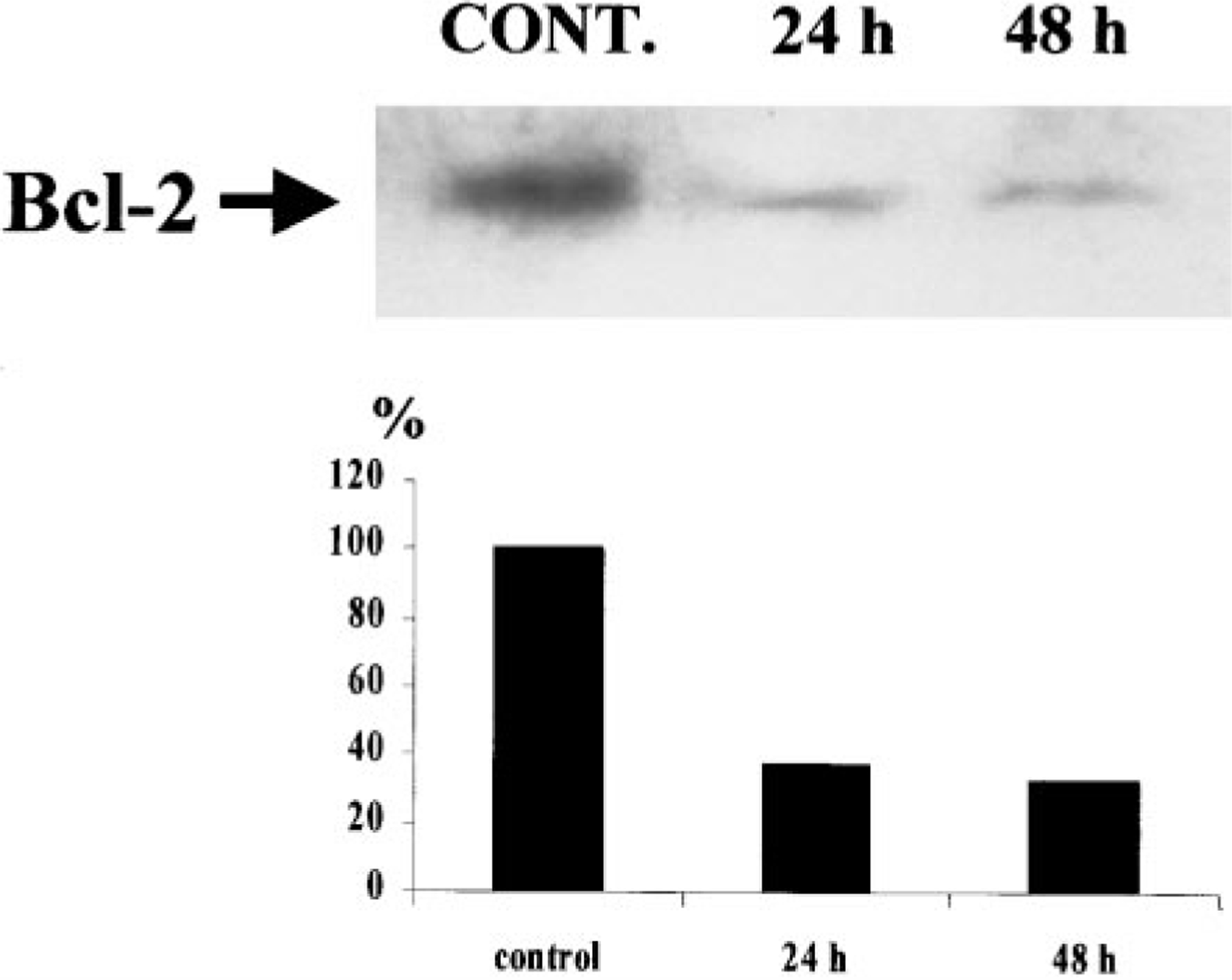

Expression of Bcl-2 Protein

To determine whether Bcl-2 could be involved in the regulation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis its expression was examined. Cultured myocytes were treated for 24 and 48 h with 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA, and relative Bcl-2 protein expression was evaluated by Western blotting. Figure 5 show that Bcl-2 protein was readily detected in control cardiomyocytes, and its expression was decreased in all periods after treatment with the A3 AR agonist.

FIG. 5.

Photographs of Western blots of Bcl-2 proteins, following Cl-IB-MECA treatment. Significant differences among control and treated cells after 24 and 48 h of exposure to A3 RC agonist.

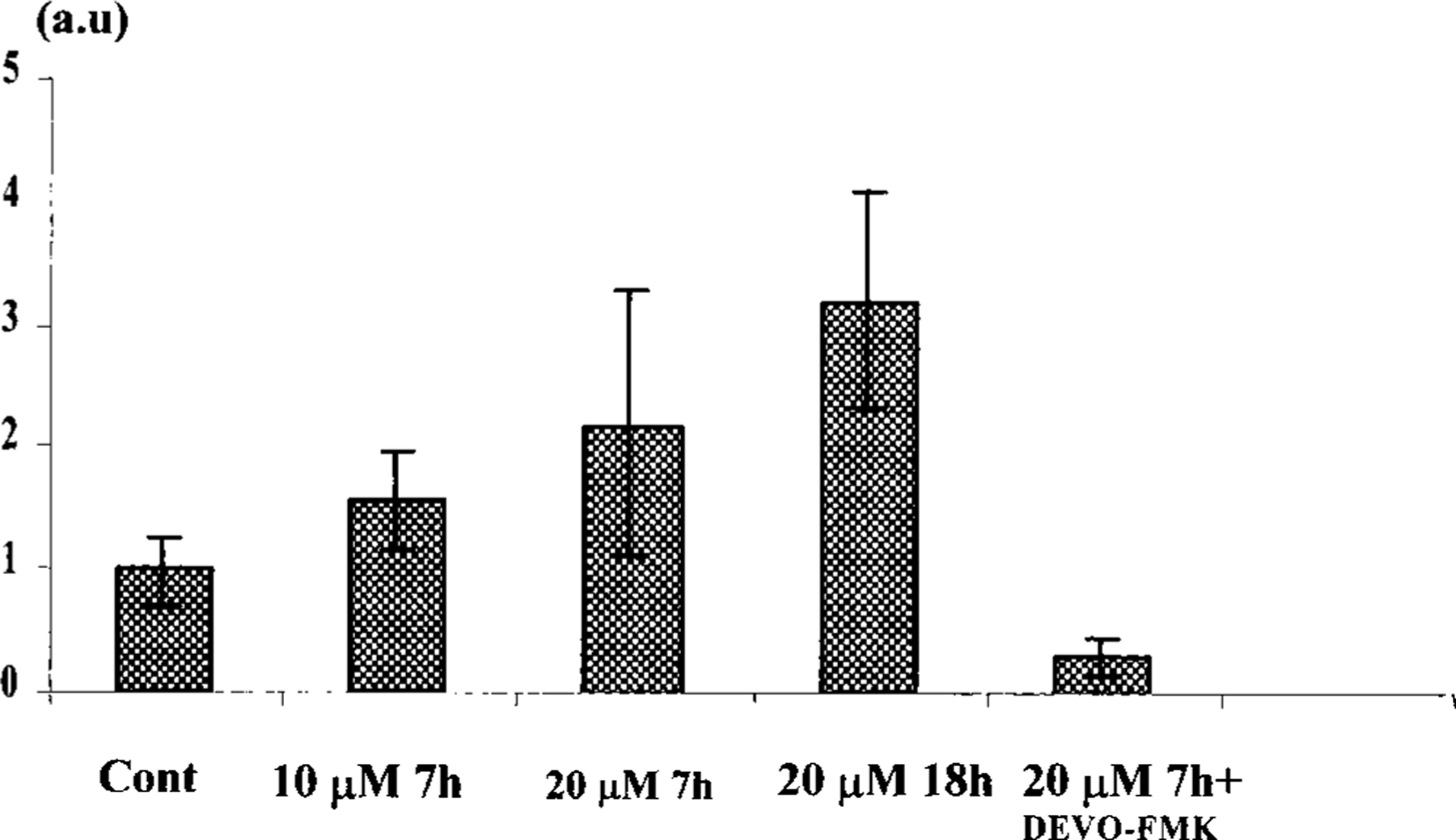

Activation of Caspase-3 Protease in Cardiomyocytes by Cl-IB-MECA

To determine whether caspase-3 is activated by an AR agonist-induced apoptotic process in myocytes, CPP32 protease activity was examined by colorimetric assay. Five-day-old cardiac cells were treated with Cl-IB-MECA, 10 or 20 µM, for 7 or 18 h. The cells were then solubilized with lysis buffer and incubated with chromogen, and protease activity was determined by a spectrophotometric method. Cl-IB-MECA activated caspase-3-like activity compared with unstimulated cells, in a concentration-dependent manner. The addition of the specific caspase-3 inhibitor DEVD-FMK (50 µM) decreased the protease activity below the level of the uninduced control (Fig. 6). When DEVD-FMK (10–50 µM) was added to cultured cardiac cells before Cl-IB-MECA it did not prevent apoptosis (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Caspase-3 (CPP32) protease activity in cardiocytes following Cl-IB-MECA. Seven and 18 h with Cl-IB-MECA (10 and 20 µM) induced two- to threefold increase in the protease activity. The CPP32 inhibitor DEVO-FMK (50 µM) decreases the caspase-3 activity below the control level.

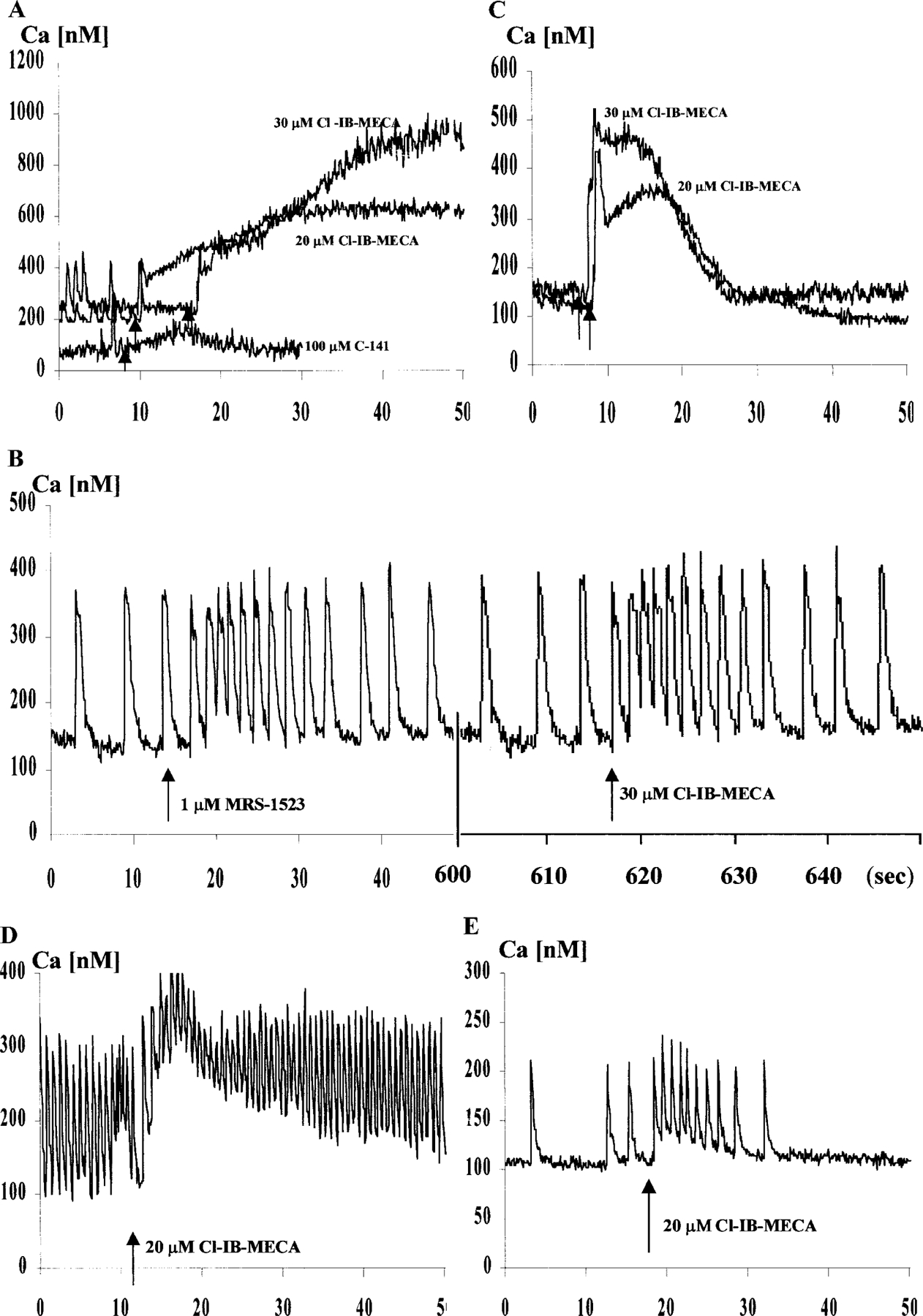

Effects of Cl-IB-MECA, MRS1523, and Isoproterenol on Intracellular Ca2+ Concentration

Cardiac cells demonstrate spontaneous, regular beating activity and Ca2+ transients. Exposure of myocytes to Cl-IB-MECA caused a concentration-dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration, which lasted 60–300 s (Fig. 7A). Pretreatment of cells with the antagonist MRS1523 blocked the Cl-IB-MECA-induced rise in intracellular calcium (Fig. 7B). Treatment of cells in a Ca2+-free medium abolished the spontaneous contraction and Ca2+ oscillations, but did not alter the intracellular Ca2+ rise induced by Cl-IB-MECA (Fig. 7C). That suggests that Ca2+ is released from intracellular storage sites, probably from the sarcoplasmic reticulum [24, 25]. Pretreatment with isoproterenol causes a transient positive chronotropic effect on cardiomyocytes contractility, which lasted beyond 24 h (Fig. 7D). The Ca2+ elevation in response to the A3 AR agonist Cl-IB-MECA within 3–24 h in both cases was significantly reduced or blocked completely (Fig. 7E).

FIG. 7.

Effect of Cl-IB-MECA on intracellular Ca2+ concentration in cultured cardiomyocytes. (A) Effects of Cl-IB-MECA (20 and 30 µM) and A2A-selective agonist CGS-21680 (C-141, 100 µM) on intracellular calcium level. The adenosine analogues were added at the indicated time (arrows). (B) Effect of the selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonist MRS1523. Ca elevation by Cl-IB-MECA was prevented. (C) Elevation of intracellular calcium levels by Cl-IB-MECA in cardiac cells in calcium-free medium. (D) Incubation with isoproterenol (5 µM) for 24 h causes positive chronotropic effect on cardiomyocyte contractility and significantly reduced calcium elevation after Cl-IB-MECA addition (arrow). (E) Response to Cl-IB-MECA (arrow) after a 3-h incubation with 5 µM isoproterenol.

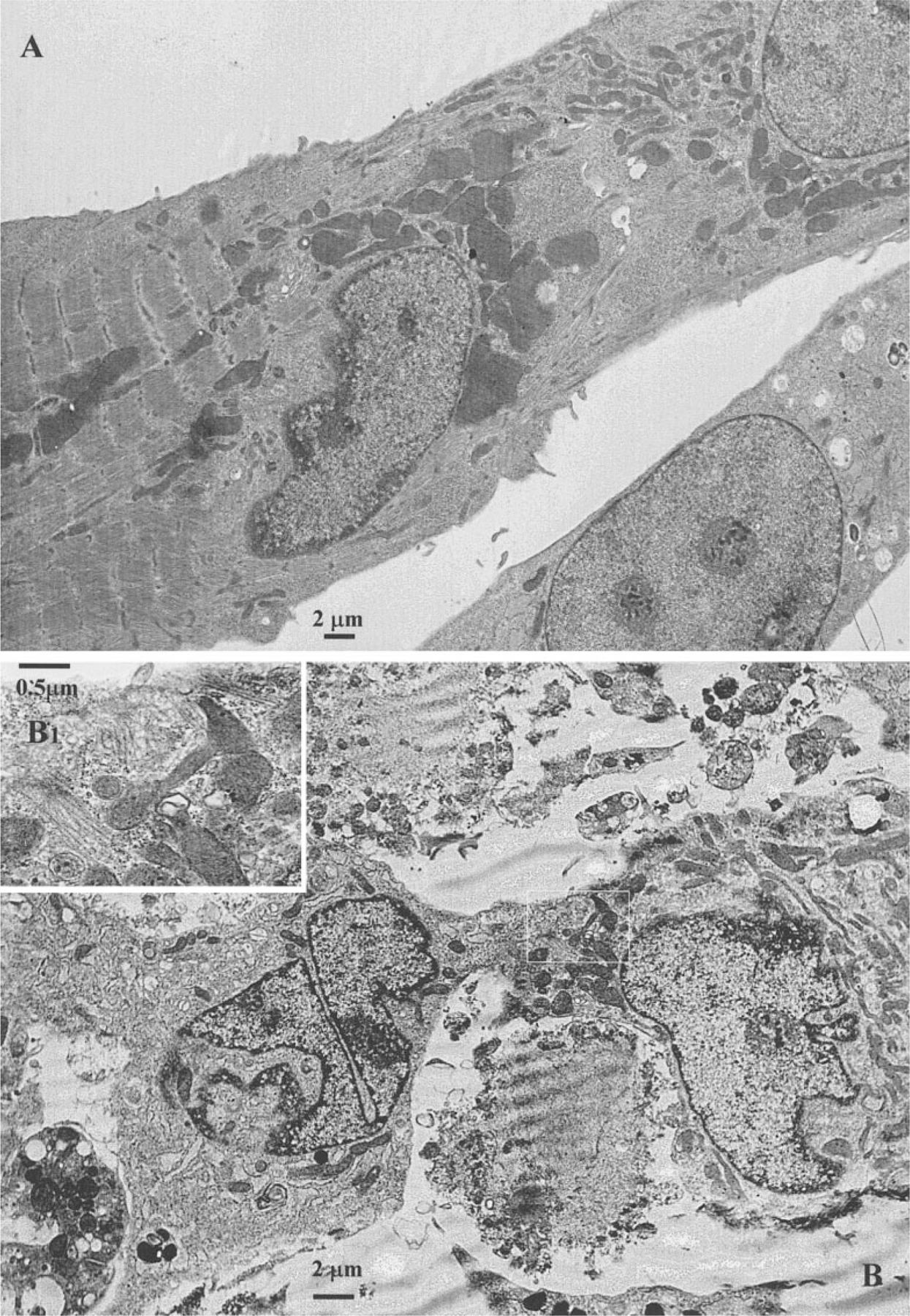

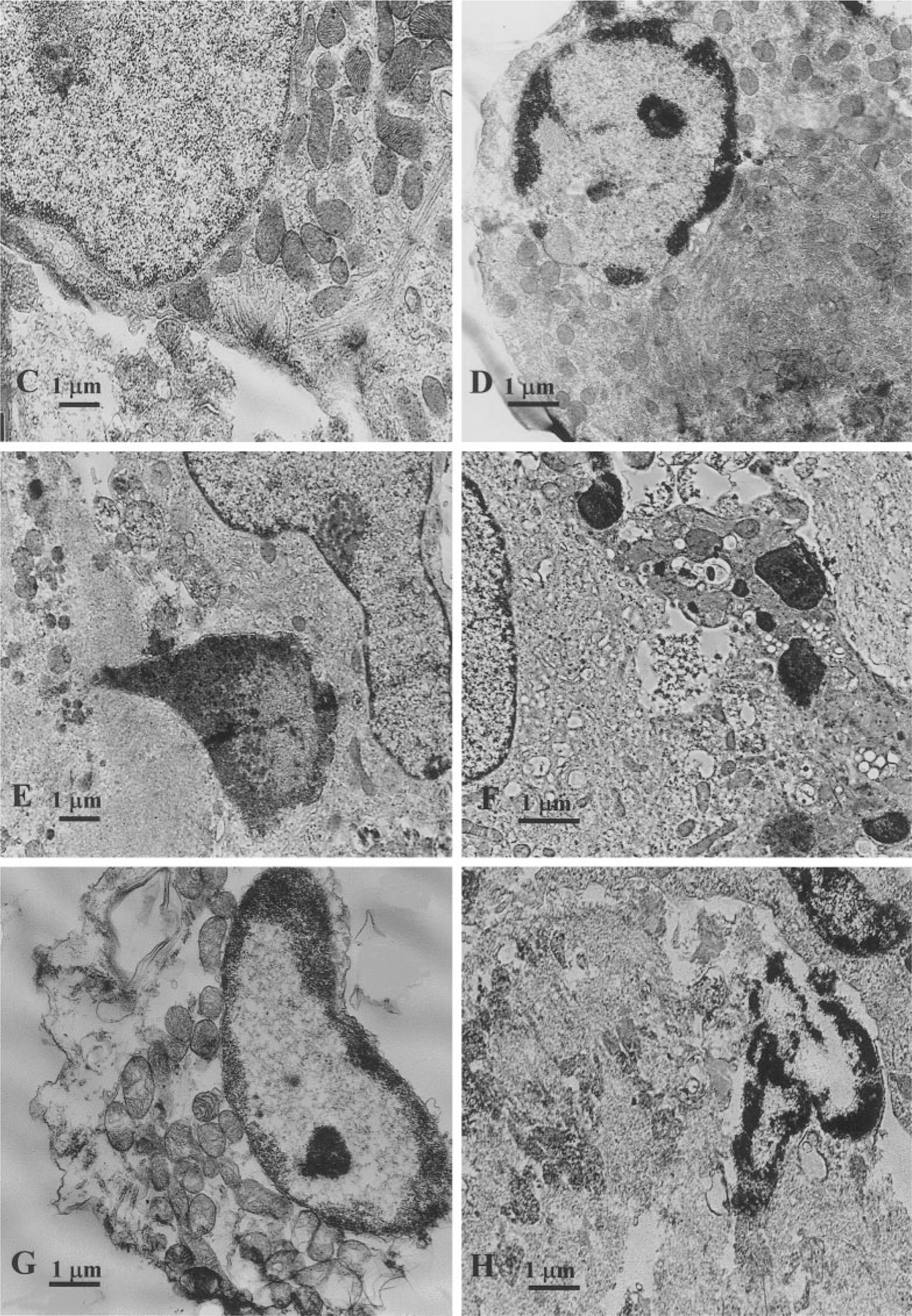

Electron Microscopy

The ultrastructure of control cultured myocytes in serum-free medium is shown in Fig. 8A. These myocytes have well-ordered myofibrils with a distinct sarcomeric registry, however, situated only in part of the sarcoplasm. In the same cell are areas with well-developed mitochondria and other ultrastructural features, including a T-system and well-developed Golgi complexes and only aberrant myofilaments. A concentration of 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA profoundly altered the ultrastructure of the cultured myocytes. Forty-eight hours of treatment of the cells altered the overall typical morphology of cardiomyocytes with highly structured myofibrillar organization. Nuclei were mainly oval and showed only a thin rim of peripheral heterochromatin. Other nuclei were irregular in shape, often showing one or more deep indentations, and there was a more conspicuous condensation of chromatin around the periphery. Many myocytes exhibited constrictions, which suggested that these cells had undergone fragmentation (Fig. 8B). Many cells were rounded and appeared to be reduced in size. Well-developed parallel myofibril arrangement was not observed in treated cells. Single fragmented myofibrils were observed near the myocyte periphery and consisted of alternating Z-lines and collections of actin filaments. A well-developed Golgi apparatus was evident near the nucleus. These preapoptotic cells responded by accumulating large amounts of mitochondria with developed cristae, rough endoplasmic reticulum, and free ribosomes. Signs of swelling of mitochondria were not observed (Fig. 8C). For such shrinking cells the condensation of chromatin was characteristic. Condensed chromatin occupied a considerable part of the cross-sectional nuclear area or was confined closely to the periphery as uniformly fine granular masses (Figs. 8D and 8E). Some cells contained discrete nuclear fragments of varying size and chromatin structure, which were surrounded by double nuclear membranes (Fig. 8F). Groups of small, membrane-bound structures between constricted cells appeared to be fragments of myocytes. They were irregular in shape and contained groups of mitochondria and fragments of nuclei, often hypercondensed. Some apoptotic bodies exhibited pronounced signs of “secondary necrosis” [26, 27], with extensive chromatinolysis, microvacuolation of sarcoplasm, and discontinuities of sarcolemma, forming cell remnants including a degraded nucleus with a rim of condensed chromatin (Figs. 8G and 8H).

FIG. 8.

Electron micrographs of a cardiac cells after exposure to 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA. (A) Ultrastructure of control cardiomyocyte, cultured in serum-free medium. (B) Loss of typical cardiomyocytes ultrastructure after 48-h treatment with the agonist, constriction, and fragmentation of nuclei. (B1) High magnification of B micrographs (inset) shows residual myofilaments of damaged cardiocyte. (C) Preapoptotic shrinking cardiomyocyte with reduced myofibrils and maintain of intact mitochondria. (D, E) Condensation of chromatin characteristic for apoptosis. Condensed chromatin occupies considerable part of cross-sectional nucleus area. (F) Nuclear fragments of varying size, surrounded by double nuclear membranes. (G, H) “Secondary necrosis” of apoptotic bodies with signs of extensive chromatinolysis, microvacuolation of sarcoplasm and cell remnants formation.

Exposing cultured cardiomyocytes to 5 µM isoproterenol prior to treatment with 20 µM Cl-IB-MECA made them more evident on the ultrastructural level in increased myofibrillar content. Well-developed parallel myofibril arrays were evident in many myocytes. Sarcomeric registry was even more highly developed in comparison to control cells cultured in serum-free medium. However, single small, membrane-bound fragments of myocytes, with dense cytoplasm and condensed nuclei (apoptotic bodies) were observed among these developed cells.

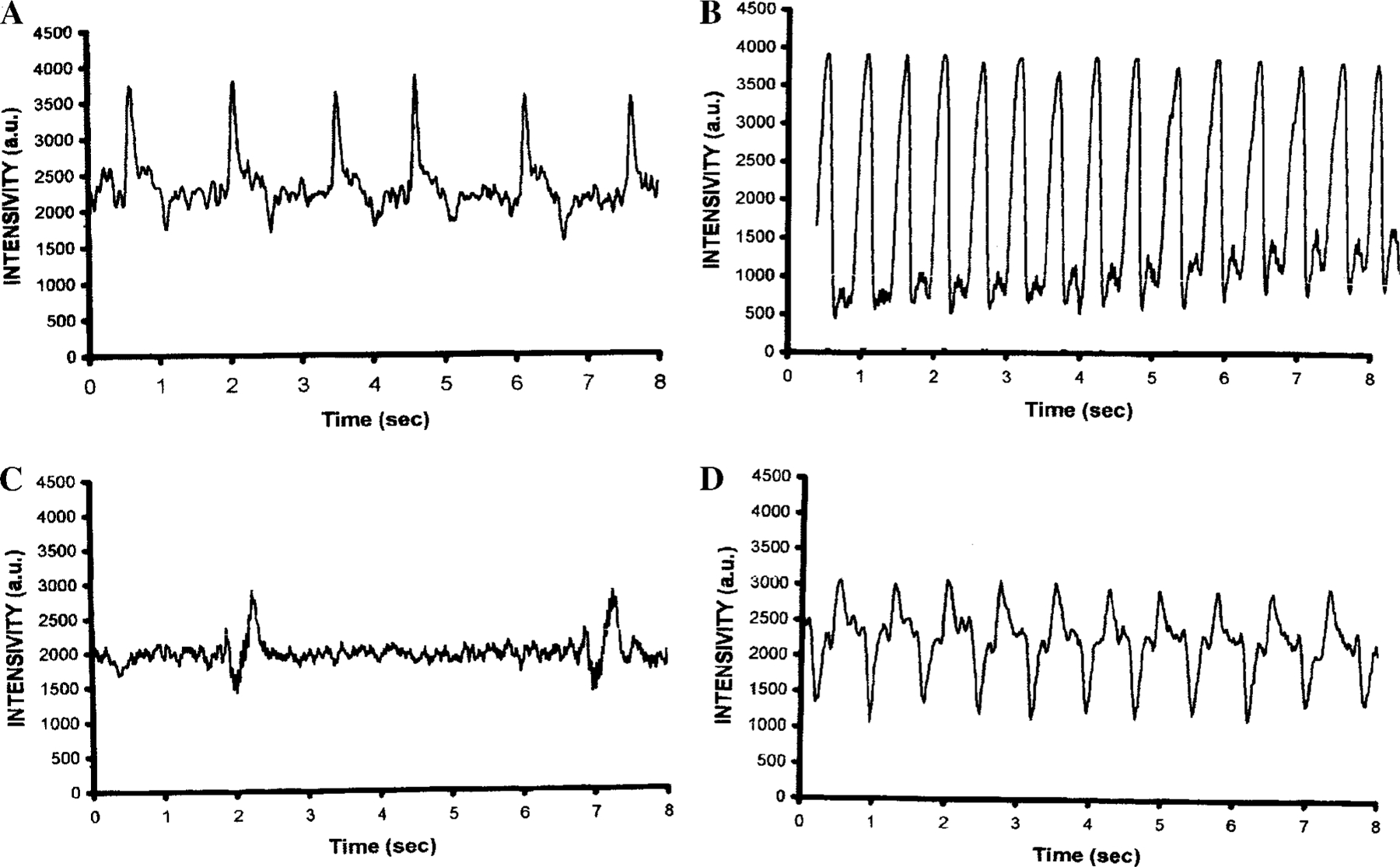

Effect of Cl-IB-MECA on Myocyte Contractility

Five-day-old myocytes, cultured in serum-free medium, exhibited a synchronous contraction with a beating rate of 45 ± 15 beats/min (Fig. 9A). Beating cardiomyocytes cultured in serum-free medium but maintained in 5 µM isoproterenol for 48 h regained a more rapid rate of contraction 140 ± 25 beats/min (Fig. 9B). Treatment with Cl-IB-MECA (20 µM) for 48 h caused inhibitory effects on contractility (Fig. 9C). The protective effect of isoproterenol on cell death induced by Cl-IB-MECA was more evident in preservation in contractility of the cells. Cells treated with Cl-IB-MECA and maintained in 5 µM isoproterenol for 48 h exhibited contraction with a beating rate of 60 ± 15 beats/min (Fig. 9D), which surpasses the beating rate of control myocytes cultured in serum-free medium.

FIG. 9.

Effect of Cl-IB-MECA and isoproterenol on contractility of cardiac cells after 48-h exposure to the drugs. (A) Control, contracting cells incubated in serum-free medium. (B) Positive chronotropic effect of isoproterenol (5 µM). (C) After application of Cl-IB-MECA (20 µM) cells showed irregular and delayed contractions. (D) Cells treated with Cl-IB-MECA (20 µM) and maintained in 5 µM of isoproterenol.

DISCUSSION

Purines are known to function as signaling molecules 25], and now there is increasing evidence that both extracellular and intracellular purines have cytotoxic properties [25, 28]. Current evidence suggests that purine nucleosides induce cell death via apoptosis [26]. Apoptosis was originally distinguished from necrosis on the basis of its ultrastructure [27, 29, 30]. Rare examples of degeneration can be seen with the light microscope, but apoptosis is more readily defined with electron microscopic examination, which is the more useful method for accurate recognition of an apoptotic cell. Although a universal biochemical or anti-genic marker for apoptosis is lacking, in situ end labeling of DNA strand breaks (TUNEL-like methods) has been widely used as a tool to mark the apoptotic cells before the appearance of morphological changes [31]. Recent publications indicate that TUNEL is not specific for apoptosis only. The TUNEL staining technique is ineffective in distinguishing between the internucleosomal cleavage of apoptosis and the nonspecific DNA degradation of necrosis even by physiologically increasing DNA repair activity [32–39]. The ultrastructural criteria for identifying cells death are well recognized [26, 27]; however, concerning cardiomyocytes not much has changed since James [40] wrote “surprisingly, to my best knowledge there has been no published recognition of apoptosis in the human heart.” In spite of a dramatic increase in publication on apoptosis in vivo and in vitro in the cardiovascular system in the past 5 years, ultrastructural aspects of the programmed cell death in cardiomyocytes remain a poorly explored phenomenon. The ultrastructural investigation of the dying myocyte is critical for understanding the morphogenesis and pathogenesis of programmed cell death induced by various means. Our data show that in early stages of exposure to high doses of Cl-IB-MECA, cardiomyocytes lose many characteristic signs of highly differentiated cells, and further morphogenesis seems to be typical for apoptotically dying cells.

Adenosine and adenosine analogues have been previously demonstrated to induce apoptosis in cell types other than cardiomyocytes [5, 25, 28] and in cultured cardiac myocytes [8]. Promising results in several recent studies demonstrate that adenosine is effective in protecting against ischemic myocardial injury in many species including humans, in such diverse settings as coronary angioplasty, coronary artery, bypass surgery, and acute myocardial infarction [9]. Adenosine can mediate the preconditioning of myocardium in vivo, in keeping with experimental data [2, 4, 9]. Novel adenosinergic therapy may be a major development for cardiovascular medicine in the coming years [9], which necessitates understanding the toxicity of adenosine. Although the pharmacological effects of adenosine result from its interaction with cell surface purinoceptors, our knowledge about the role of these receptors in the cytotoxic effects of adenosine remains very incomplete [25]. Adenosine analogues were demonstrated to induce cell death via at least three independent pathways. One pathway seems to involve the activation of extracellular A2A ARs [12]. A second pathway involves the adenosine A3 receptor [8, 10, 41]. A third intracellular pathway seems to be directly activated following entry of adenosine into cells [11, 12]. Recently, we demonstrated that the A3 AR agonist IB-MECA induces apoptosis in cultured cardiac myocytes [8]. There is evidence that A3 ARs may be expressed in ventricular cardiomyocytes [4, 42], but observations of Norton et al. [15] support the concept stated earlier that A3 receptors may not be present in the ventricular myocardium in adult rats. A2A receptors exert proadrenergic effects in the intact rat heart. A2B ARs also are expressed in isolated embryonic cardiac myocytes [14], and A2B receptors have been found to inhibit growth of cardiac fibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells [43, 44]. In this report, we have investigated the apoptotic potential of the highly potent and selective A3 AR agonist Cl-IB-MECA (which shows selectivity for the A3 versus A1 and A2A receptors of 2500- and 1400-fold, respectively, whereas IB-MECA is 50-fold selective for A3 versus A1 or A2A receptor [5]). A recently developed, selective A3 AR antagonist MRS1523 [13] was prepared as an optimized ligand at rat A3 receptors. This derivative was highly potent at both human and rat A3 receptors, and in rat it corresponds to selectivities of 140- and 18-fold vs A1 and A2A receptors, respectively [13]. Our data exhibited that A3 ARs are expressed at least in newborn cardiac myocytes, and intensive activation of these receptors is responsible for the cytotoxic action of adenosine analogues.

Cell death by apoptosis requires gene expression. In general, each cell contains precursors to apoptogenic mediators, as well as counteracting, protective proteins. It is the balance between these two which determines the outcome after a given stimulus. Our data suggest that antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 may be the target in cardiac myocytes after intensive activation of A3 ARs. Bcl-2 proteins are expressed at high levels in the heart [16, 45]. Bcl-2 gene encodes a protein localized in intracellular membranes, including endoplasmic reticulum membranes [46] and mitochondrial membranes. Its function is to inhibit apoptosis, possibly through an antioxidant pathway [47]. Our data shows that exposure to A3 ADO agonist is accompanied by a dramatic downregulation of Bcl-2 gene expression. The decrease in Bcl-2 protein family expression suggests that the sensitivity of myocytes to undergo apoptosis is increased; however, attenuation of Bcl-2 alone cannot initiate apoptosis in myocytes [48]. Recently, we have reported that IB-MECA induces apoptosis in cultured myocytes and that a rise in sarcoplasmic free calcium is implicated in these cells [8]. We have hypothesized that the sustained elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ triggered by this nucleoside stimulates an endonuclease activity and initiates cardiomyocyte apoptosis. We now show that Cl-IB-MECA in micromolar concentrations causes a reversible rapid and sustained increase in the cytosolic free calcium, which was prevented by the selective antagonist MRS1523. These results suggest that an increase in intracellular Ca2+ may be a key event in A3 AR-induced apoptosis. However, both transient and sustained [Ca2+]i increases alone do not cause nuclear and cellular fragmentation, implying that specific apoptosis-inducing signals are required [49].

To gain further insights into the pathway of Cl-IB-MECA-induced apoptosis the role of caspase-3 activation was studied. There is emerging evidence that caspases have been implicated as the key enzymes involved in the execution of apoptosis in heart. Chow et al. [25] postulated that proteases belonging to ICE-enzyme family, also known as caspases, must “act as an intracellular convergence point that orchestrates the morphological and biochemical features of apoptosis” induced by purines. As was shown, an apoptotic signal requires activation of caspase-3 in a concentration-dependent manner 7 h after treatment with Cl-IB-MECA, and this upregulation was significantly increased after 20 h of exposure. However, when caspase inhibitor was applied to cultured cells before Cl-IB-MECA, prevention of apoptosis did not occur. These data indicates that caspase-3 activation is not necessary for the induction of apoptosis through this particular adenosine analogue. CPP32 normally exists as an inactive precursor that becomes activated proteolytically in cells undergoing apoptosis [50]. It may be suggested that in the present work caspase-3 participates on the later apoptotic death stage.

Recent studies have made significant progress in establishing the signal transduction pathways for apoptosis. A variety of key events in apoptosis focus on mitochondria, including the release of caspase activators (such as cytochrome c), changes in electron transport, loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, altered cellular oxidation–reduction, and participation of Bcl-2 family proteins [51]. The antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 inhibits the release of cytochrome c, the loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), and the opening of the pore [47, 51], which attenuates the downstream apoptotic process. The present findings indicate that in apoptosis induced by Cl-IB-MECA, mitochondria seem to be functionally intact during many phases of the programmed cell death. Indeed, they show no significant variation in membrane potential until 40 – 48 h of incubation with the agonist. DNA fragmentation seemed to precede all the events studied, including loss of DNA (revealed by the image analysis of Feulgen-stained chromatin by the presence of hypodiploid peak). By studying the retention of DASPMI dye in Cl-IB-MECA-treated cardiomyocytes and the ultrastructure it was shown that the mitochondria maintain their transmembrane potential and membrane intactness up to the terminal phase of the cell’s death. It appears that the damage of mitochondria is not responsible for Cl-IB-MECA-induced apoptosis. The same conclusion was made by Barbieri et al. [12], using the mitochondrial membrane-potential-specific dye JC-1, after a number of adenosine derivatives induced death of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

β-Adrenergic stimulation antagonized the proapoptotic effect of Cl-IB-MECA. In mammalian cardiomyocytes the signal transduction of β-adrenoceptors includes several steps of interaction of functionally coupled downstream components [52]. A receptor-activated guanine nucleotide-binding protein (Gs-protein) triggers the activation of adenylyl cyclase and, in turn, increases the level of cytosolic cAMP. This is followed by the phosphorylation of the Ca2+ channel through the activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A [52]. Wu et al. [16], demonstrated that norepinephrine or isoproterenol antagonized the apoptogenic effect of ANP in cultured cardiomyocytes through a cAMP/protein kinase A-dependent mechanism. In the present study, the cAMP analog dibutyryl-cAMP increased the apoptotic activity of Cl-IB-MECA in a concentration-dependent manner. These results suggest that the apoptotic effect of the GI-protein-coupled A3 AR is counteracted by activation of the Gs-protein-coupled β-adrenergic receptor, through a cAMP/protein kinase A-independent mechanism associated with calcium influx. Bishopric et al. [53, 54] demonstrated in a neonatal rat cell culture system that isoproterenol stimulates myocytes to enlarge and contract synchronously. This process is associated with a selective induction of the skeletal α-actin gene. They suggest a novel mechanism for β-adrenergic gene regulation involving calcium influx coupled to sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release, independent of cAMP. The role of a cAMP-independent pathway in induction and protection of myocytes apoptosis is extremely essential, because A3 AR, like the A1-AR, is negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase, and an A3 AR agonist was shown to inhibit isoproterenol-induced increases in cAMP [42]. In conclusion, high concentrations of Cl-IB-MECA induced morphological modifications of rat cardiomyocytes, such as rounding and retraction of the cell body and dissolution of actin filaments followed by apoptotic death. The adenosine analogue caused a sustained and reversible increase in [Ca2+]i, which was blocked by selective antagonist MRS1523. In addition, MRS1523 protected the cells from dying following a brief exposure to Cl-IB-MECA. Our data suggested that the apoptosis-inducing signal from the A3 AR or an attenuating β-adrenergic signal leads to modulation in the domain of G-protein-coupled enzymes and downstream. This modulation also involves a self-amplifying cascade including the expression of different genes that are responsible for orchestrating cardiomyocyte apoptosis or its protection.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Ms. A. Isaac and to Ms. T. Zinman for their valuable technical assistance. This research is supported by grant from United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), Jerusalem, and Ministry of Health, State of Israel.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou Q, Li C, Olah ME, Jonson RA, Stiles GL, and Civelli O (1992). Molecular cloning and characterization of an adenosine receptor: The A3 adenosine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 7432–7436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giannella E, Mochmann HC, and Levi R (1997). Ischemic preconditioning prevents the impairment of hypoxic coronary vasodilatation caused by ischemia/reperfusion: Role of adenosine A1/A3 and bradykinin B2 receptor activation. Circ. Res 81, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fozard JR, Pfannkuche HJ, and Schuurman HJ (1996). Mast cell degranulation following adenosine A3 receptor activation in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol 298, 293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang BT, and Jacobson KA (1998). A physiological role of the adenosine A3 receptor: Sustained cardioprotection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6995–6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson KA (1998). Adenosine A3 receptors: Novel ligands and paradoxical effects. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 19, 184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbracchio M, Brambilla R, Ceruti S, Kim HO, Von Lubitz DKJE, Jacobson KA, and Cattabeni F (1995). G protein-dependent activation of phospholipase C by adenosine A3 receptors in rat brain. Mol. Pharmacol 48, 1038–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali H, Choi OH, Fraundorfer PF, Yamada K, Gonzaga HM, and Beaven MA (1996). Sustained activation of phospholipase D via adenosine A3 receptors is associated with enhancement of antigen- and Ca2+-ionophore-induced secretion in a rat mast cell line. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 276, 837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shneyvays V, Nawrath H, Jacobson KA, and Shainberg A (1998). Induction of apoptosis in cardiac myocytes by an A3 adenosine receptor agonist. Exp. Cell Res 243, 383–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auchampach JA, and Bolli R (1999). Adenosine receptor subtypes in the heart: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Am. J. Physiol 276, H1113–H1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohno Y, Yoshitatsu S, Koshiba M, Kim HO, and Jacobson KA (1996). Induction of apoptosis in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells by adenosine A3 receptor agonists. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 219, 904–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbracchio MP, Ceruti S, Brambilla R, Franceschi C, Malorni W, Jacobson KA, von Lubitz DK, and Cattabeni F (1997). Modulation of apoptosis by adenosine in the central nervous system: A possible role for the A3 receptor—Pathophysiological significance and therapeutic implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 825, 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbieri D, Abbracchio MP, Salvioli S, Monti D, Cossarizza A, Ceruti S, Brambilla R, Cattabeni F, Jacobson KA, and Franceschi C (1998). Apoptosis by 2-chloro-2’-de-oxy-adenosine and 2-chloro-adenosine in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Neurochem. Int 32, 493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li AH, Moro S, Melman N, Ji XD, and Jacobson KA (1998). Structure–activity relationships and molecular modeling of 3,5-diacyl-2,4-dialkylpyridine derivatives as selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem 41, 3186–3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang BT, and Haltiwanger B (1995). Adenosine A2a and A2b receptors in cultured fetal chick heart cells: High- and low-affinity coupling to stimulation of myocyte contractility and cAMP accumulation. Circ. Res 76, 242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norton GR, Woodiwiss AJ, McGinn RJ, Lorbar M, Chung ES, Honeyman TW, Fenton RA, Dobson JGJ, and Meyer TE (1999). Adenosine A1 receptor-mediated anti-adrenergic effects are modulated by A2a receptor activation in rat heart. Am. J. Physiol 276, H341–H349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu CF, Bishopric NH, and Pratt RE (1997). Atrial natriuretic peptide induces apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem 272, 14860–14866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein L, Brik H, Rotmench HH, and Shainberg A (1991). Characterization of sarcoplasmic reticulum in skinned heart muscle cultures. J. Cell. Physiol 148, 124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bereiter-Hahn J (1976). Dimethylaminostyrylmethylpyridiniumiodine (DASPMI) as a fluorescent probe for mitochondria in situ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 423, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuznetsov AV, Mayboroda O, Kunz D, Winkler K, Schubert W, and Kunz WS (1998). Functional imaging of mitochondria in saponin-permeabilized mice muscle fibers. J. Cell Biol 140, 1091–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claycomb WC, and Moses RL (1988). Growth factor and TPA stimulate DNA synthesis and alter the morphology of cultured terminally differentiated adult rat cardiac muscle cells. Dev. Biol 127, 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, and Tsien TY (1985). A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem 260, 3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geng YJ, Ishikawa Y, Vatner DE, Wagner TE, Bishop SP, Vatner SF, and Homcy CJ (1999). Apoptosis of cardiac myocytes in Gsalpha transgenic mice. Circ. Res 84, 34– 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desjardins LM, and MacManus JP (1995). An adherent cell model to study different stages of apoptosis. Exp. Cell Res 216, 380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wibo M, Bravo G, and Godfraind T (1991). Postnatal maturation of excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricle in relation to the subcellular localization and surface density of 1,4-dihydropyridine and ryanodine receptors. Circ. Res 68, 662–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chow SC, Kass GE, and Orrenius S (1997). Purines and their roles in apoptosis. Neuropharmacology 36, 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyllie AH, Kerr JF, and Currie AR (1980). Cell death: The significance of apoptosis. Int. Rev. Cytol 68, 251–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr JF, Gobe GC, Winterford CM, and Harmon BV (1995). Anatomical methods in cell death. Methods Cell Biol 46, 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbracchio MP, and Burnstock G (1998). Purinergic signalling: Pathophysiological roles. Jpn. J. Pharmacol 78, 113–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr JF (1971). Shrinkage necrosis: A distinct mode of cellular death. J. Pathol 105, 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, and Currie AR (1972). Apoptosis: A basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 26, 239–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, and Ben Sasson SA (1992). Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Cell Biol 119, 493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bobryshev YV, Babaev VR, Lord RS, and Watanabe T (1997). Cell death in atheromatous plaque of the carotid artery occurs through necrosis rather than apoptosis. In Vivo 11, 441–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gold R, Schmied M, Giegerich G, Breitschopf H, Hartung HP, Toyka KV, and Lassmann H (1994). Differentiation between cellular apoptosis and necrosis by the combined use of in situ tailing and nick translation techniques. Lab. Invest 71, 219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Migheli A, Attanasio A, and Schiffer D (1995). Ultrastructural detection of DNA strand breaks in apoptotic neural cells by in situ end-labelling techniques. J. Pathol 176, 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hegyi L, Hardwick SJ, Mitchinson MJ, and Skepper JN (1997). The presence of apoptotic cells in human atherosclerotic lesions. Am. J. Pathol 150, 371–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saraste A, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Parvinen M, and Pulkki K (1997). Apoptosis in the heart. N. Engl. J. Med 336, 1025–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanoh M, Takemura G, Misao J, Hayakawa Y, Aoyama T, Nishigaki K, Noda T, Fujiwara T, Fukuda K, Minatoguchi S, and Fujiwara H (1999). Significance of myocytes with positive DNA in situ nick end-labeling (TUNEL) in hearts with dilated cardiomyopathy: Not apoptosis but DNA repair. Circulation 99, 2757–2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takemura G, Ohno M, and Fujiwara H (1997). Ischemic heart disease and apoptosis. Rinsho Byori 45, 606– 613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takemura G, Ohno M, Hayakawa Y, Misao J, Kanoh M, Ohno A, Uno Y, Minatoguchi S, Fujiwara T, and Fujiwara H (1998). Role of apoptosis in the disappearance of infiltrated and proliferated interstitial cells after myocardial infarction. Circ. Res 82, 1130–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.James TN (1994). Normal and abnormal consequences of apoptosis in the human heart. Circulation 90, 556–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao Y, Sei Y, Abbracchio MP, Jiang J, Kim Y, and Jacobson KA (1997). Adenosine A3 receptor agonist protect HL-60 and U-937 cells from apoptosis induced by A 3 antagonists. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 232, 317–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strickler J, Jacobson KA, and Liang BT (1996). Direct preconditioning of cultured chick ventricular myocytes: Novel functions of cardiac adenosine A2a and A3 receptors. J. Clin. Invest 98, 1773–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, and Jackson EK (1998). Adenosine inhibits collagen and protein synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts: role of A2B receptors. Hypertension 31, 943–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Mi Z, and Jackson EK (1998). Adenosine inhibits growth of human aortic smooth muscle cells via A2B receptors. Hypertension 31, 516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Ellerby LM, Welsh K, Xie Z, Deveraux QL, Salvesen GS, Bredesen DE, Rosenthal RE, Fiskum G, and Reed JC (1999). Release of caspase-9 from mitochondria during neuronal apoptosis and cerebral ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5752–5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haldar S, Chintapalli J, and Croce CM (1996). Taxol induces bcl-2 phosphorylation and death of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 56, 1253–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamata H, and Hirata H (1999). Redox regulation of cellular signalling. Cell Signal 11, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pierzchalski P, Reiss K, Cheng W, Cirielli C, Kajstura J, Nitahara JA, Rizk M, Capogrossi MC, and Anversa P (1997). p53 induces myocyte apoptosis via the activation of the renin–angiotensin system. Exp. Cell Res 234, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oshimi Y, Oshimi K, and Miyazaki S (1996). Necrosis and apoptosis associated with distinct Ca2+ response patterns in target cells attacked by human natural killer cells. J. Physiol. (London) 495, 319–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang L, Ma W, Markovich R, Chen JW, and Wang PH (1998). Regulation of cardiomyocyte apoptotic signaling by insulin-like growth factor I. Circ. Res 83, 516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green DR, and Reed JC (1998). Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 281, 1309–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maltsev VA, Ji GJ, Wobus AM, Fleischmann BK, and Hescheler J (1999). Establishment of beta-adrenergic modulation of L-type Ca2+ current in the early stages of cardiomyocyte development. Circ. Res 84, 136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bishopric NH, and Kedes L (1991). Adrenergic regulation of the skeletal alpha-actin gene promoter during myocardial cell hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 2132–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bishopric NH, Sato B, and Webster KA (1992). Beta-adrenergic regulation of a myocardial actin gene via a cyclic AMP-independent pathway. J. Biol. Chem 267, 20932–20936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]