Abstract

Background

Recent pandemics have had far-reaching effects on the world’s largest economies and amplified the need to estimate the full extent and range of socioeconomic impacts of infectious diseases outbreaks on multi-sectoral industries. This systematic review aims to evaluate the socioeconomic impacts of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases outbreaks on industries.

Methods

A structured, systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines. Databases of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, IDEAS/REPEC, OSHLINE, HSELINE, and NIOSHTIC-2 were reviewed. Study quality appraisal was performed using the Table of Evidence Levels from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Joanna Briggs Institute tools, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, and Center of Evidence Based Management case study critical appraisal checklist. Quantitative analysis was not attempted due to the heterogeneity of included studies. A qualitative synthesis of primary studies examining socioeconomic impact of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases outbreaks in any industry was performed and a framework based on empirical findings was conceptualized.

Results

A total of 55 studies conducted from 1984 to 2021 were included, reporting on 46,813,038 participants working in multiple industries across the globe. The quality of articles were good. On the whole, direct socioeconomic impacts of Coronavirus Disease 2019, influenza, influenza A (H1N1), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, tuberculosis and norovirus outbreaks include increased morbidity, mortality, and health costs. This had then led to indirect impacts including social impacts such as employment crises and reduced workforce size as well as economic impacts such as demand shock, supply chain disruptions, increased supply and production cost, service and business disruptions, and financial and Gross Domestic Product loss, attributable to productivity losses from illnesses as well as national policy responses to contain the diseases.

Conclusions

Evidence suggests that airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases have inflicted severe socioeconomic costs on regional and global industries. Further research is needed to better understand their long-term socioeconomic impacts to support improved industry preparedness and response capacity for outbreaks. Public and private stakeholders at local, national, and international levels must join forces to ensure informed systems and sector-specific cost-sharing strategies for optimal global health and economic security.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-024-08993-y.

Keywords: Infectious disease, Outbreak, Epidemic, Pandemic, Socioeconomic impact, Socioeconomic burden, Socioeconomic cost

Background

For every country across the globe, the industries and sectors have fundamental roles in both its economic and social development. Not only are industries a main contributor to a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and economic growth, it is critical for employment creation, technological advancements, and general improvements in living standards. In 2021, the services, manufacturing, agriculture, forestry, and fishing industries contribute to 65.7, 28.3, and 4.3% of the world GDP and accounts for 51, 23, and 27% of total employment, respectively [1]. Over the past decades, industrialisation and the accompanying economic growth in terms of increase in per capita GDP have resulted in increases in wages and household incomes, as well as improved nutrition, housing, sanitation, medical care, and literacy [2, 3].

Despite the era of modernization and public health advances, regional and global emerging and endemic infectious diseases outbreaks continue to not only adversely impact global health systems, but also give rise to wider socioeconomic consequences [4]. This includes airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases incidences of varying scale and magnitude, including endemics, outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics. The ongoing pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), declared a global emergency by the World Health Organisation (WHO) on January 30, 2020, has had far-reaching impacts on the world’s largest economies, including industries of the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors [5]. These include increased healthcare costs, job losses, macroeconomic instability, and dwindling in micro, small, medium-sized enterprises (MSME) as well as informal industries [5, 6]. Health disasters such as the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) pandemic in 2003, which lasted approximately 6 months, had led to a total global economic loss of approximately USD40 billion due to its impacts on the hospitality, commerce, transport and multi-national industries such as the oil industry [4]. Similarly, the influenza A (H1N1) 2009–2010 pandemic led to severe economic recession and crash in the stock market values of multiple industries [7].

These socioeconomic effects can be felt not only from large-scale infectious diseases outbreaks, but from outbreaks of a smaller scale as well. Seasonal influenza epidemics continue to pose direct and indirect costs to organisations, including absenteeism, losses in productivity, and impaired performance [8]. Norovirus outbreaks, a common occurrence in semi-enclosed settings, has led to a loss of USD2 billion in the United States of America (USA) alone, due to lost productivity and healthcare expenses [9]. Meanwhile, endemic infectious diseases such as tuberculosis adversely affects the labour force, disrupts local economies, and is projected to result in an economic loss of USD17.5 trillion based on estimations of tuberculosis mortality from 2020 to 2050 in 120 countries [10]. Evidence suggests that respiratory pathogens such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), and influenza virus have airborne transmission, culminating in numerous superspreading events that led to the spread of these diseases at alarming rates and causing huge devastations on global economies [11].

The escalating costs associated with airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases have amplified the need to estimate the full extent and range of socioeconomic impacts on multi-sectoral industries. A greater appreciation of these impacts would enable an assessment of burden of diseases as well as contribute towards the development of long-term prevention and preparedness measures, prioritization exercises, and optimization of resources. Unfortunately, there is presently limited evidence for the socioeconomic impacts of infectious diseases on industries. Previous studies that have explored this subject were studies focusing on particular geographical regions [12, 13] or specific infectious diseases such as COVID-19 [14, 15], influenza [8, 16, 17], and tuberculosis [10], or studies examining economic impacts exclusively [18, 19]. On the other hand, Smith et al. (2019) [4] illustrated the multi-sectoral socioeconomic impacts of infectious diseases using a case-study approach, but the findings relate to pre-COVID-19 pandemic era. With this in mind, this study aims to systematically examine the pool of evidence pertaining socioeconomic impacts of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases on industries and conceptualizing a framework based on empirical findings.

Methods

This systematic review was reported in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [20]. The systematic review protocol was registered in INPLASY Register (Registration No. INPLASY202190055).

Design and research aims

A structured, systematic review and qualitative synthesis of peer-reviewed publications was performed to explore the socioeconomic and safety and health impacts of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases in industries; however, due to the high numbers of included studies this review will be focused on socioeconomic impacts exclusively. Due to the heterogeneity of included studies, quantitative analysis was not attempted.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search of the literature was undertaken in August 2021 using three biomedical electronic database (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science), one economic database (IDEAS/REPEC) and three occupational safety and health databases (OSHLINE, HSELINE, and NIOSHTIC-2). The search aimed to identify relevant articles published in peer-reviewed journals written in English, with the assumption that most of the important findings will be reported in English regardless of country of origin. Boolean search was performed on each database, without restriction to date or publication, as illustrated in Supplementary Document 1.

The terms included in the Boolean search were chosen after careful consideration and consensus of terms identified from literature review, in view of the variation in keywords of interest. The first combination of keywords included various terms denoting socioeconomic and occupational safety and health impacts of infectious diseases at the workplace as described by previous studies [4, 21–24]. The second combination of keywords included key terms related to infectious diseases and common pathogens that may spread via droplets and airborne transmission [25]. Herein, droplet-borne infectious disease was defined as an infectious disease which is transmitted when a person is exposed to infective respiratory droplets, whereas airborne infectious disease was defined as an infectious disease which is transmitted when a person is exposed to droplet nuclei (aerosols) [26]. Finally, the third combination of keywords included terms that specify workplace settings. To broaden the search, the Boolean search operator “OR” was used with multiple analogous terms, whereas “AND” was used to narrow the search to studies examining socioeconomic and safety and health impacts of infectious diseases on workers in industries. The search was conducted by one reviewer. All searches were concluded by 29th August 2021.

Selection criteria and study selection

Upon completion of the searches, articles were organized into EndNote 20 Software. Duplicates were identified and removed. This was performed by one reviewer, firstly using the “Find and Remove Duplicate References” function, and secondly using manual screening given that a number of the same articles were entered differently into different databases. Following duplicates removal, articles were assessed for eligibility independently by two reviewers in two stages. In stage one, the title and abstract of search results were screened and assessed for relevance. In stage two, the full-text of potentially relevant publications were retrieved and reviewed for inclusion. Any primary studies in English examining socioeconomic impacts of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases outbreaks in any industry were included. Here, socioeconomic impacts in industries was defined as impacts related to social and economic aspects of industries, such as the morbidity and mortality, costs associated with disease diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, as well as productivity loss, employment, financial loss, and disruption in supply chain and services [7, 27]. Non-human studies, non-primary studies including reviews, editorials, commentaries, forewords, opinion pieces, and books, studies that examined infectious diseases transmitted via routes other than airborne and droplet-borne transmission, studies examining variables others than socioeconomic impacts, and studies not concerning industries or workers were excluded. The reason for excluding a publication following title and abstract review as well as full-text review was noted. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described previously, the list of studies included and excluded was cross-validated. Consensus was obtained where possible for any disagreement, and in cases when not, and a third reviewer was assigned. The per cent agreement and Cohen’s Kappa were 99.8% and 0.993 respectively for stage one and 98.4% and 0.955 respectively for stage two of the study selection process, which indicated excellent interrater reliability [28]. To allow for quality assessment, measures to contact authors for articles not available in full text were taken, and only full text articles were included in the review. Due to resource limitations, hand searching was not performed.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was examined by evaluating the level of evidence according to the Table of Evidence Levels from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) [29] and quality of study according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tools [30] and Center of Evidence Based Management (CEBMa) case study critical appraisal checklist [31] (Supplementary Document 2). The CCHMC classifies level of evidence for individual studies by study design, domain, and quality, with level 1 representing the highest level and indicating the strongest evidence, and level 5 representing the lowest level and indicating the weakest evidence [29]. In addition, the JBI and CEBMa tools were used to further subclassify studies at each level to either “a” or “b”, which signifies good quality and lesser quality study respectively in terms of methodological quality. The JBI tools are widely used critical appraisal tools developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute, a researching and development organisation based in the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at the University of Adelaide, South Australia [30]. Compared to other tools, the applicable range of the JBI tools are wide and they are deemed to be highly coherent appraisal instruments [32, 33]. On the other hand, the CEBMa tools were developed by CEBMa [31] for assessing the methodological quality of case studies. Both JBI and CEBMa tools include critical appraisal checklists for specific study designs. For longitudinal studies, the JBI tool for cohort studies was applied, and the ratings related to Question 1, 2 and 6 which are specific for cohort study were marked as not applicable. Based on a ‘star system’, a star was awarded for every quality criterion met by the study and the quality rating was assigned as follows:

Longitudinal studies: 8 maximum stars and a final rating of 0–2 stars as “poor”, 3–4 stars as “moderate”, 5–6 stars as “good” and 7–8 stars as “excellent”

Cohort studies: 11 maximum stars and a final rating of 0–2 stars as “poor”, 3–5 stars as “moderate”, 6–8 stars as “good” and 9–11 stars as “excellent”

Case-control studies: 10 maximum stars and a final rating of 0–2 stars as “poor”, 3–5 stars as “moderate”, 6–7 stars as “good”, and 8–10 stars as “excellent”

Analytical cross-sectional studies: 8 maximum stars and a final rating of 0–2 stars as “poor”, 3–4 stars as “moderate”, 5–6 stars as “good”, and 7–8 stars as “excellent”

Prevalence studies: 9 maximum stars and a final rating of 0–2 stars as “poor”, 3–5 stars as “moderate”, 6–7 stars as “good”, and 8–9 stars as “excellent”

Qualitative studies: 10 maximum stars and a final rating of 0–2 stars as “poor”, 3–5 stars as “moderate”, 6–7 stars as “good”, and 8–10 stars as “excellent”

Case studies: 10 maximum stars and a final rating of 0–2 stars as “poor”, 3–5 stars as “moderate”, 6–7 stars as “good”, and 8–10 stars as “excellent”

In the final quality rating, studies under the categories “excellent” and “good” were rated as “a” and those under the categories “poor” and “moderate” were rated as “b”. The quality assessment was performed independently by two reviewers. Data extraction and analysis were cross-validated to assess for disagreements. For any disagreement that was present, consensus was sought where possible. A third reviewer was assigned in cases where that were not possible.

Data extraction and analysis

For each of the included study, data on author, year of publication, location of study, industry, type of infectious disease, year of outbreak, study design, study population, number of participants included, study variables examined, study instruments used, and socioeconomic impacts were extracted. Using the web-based tool CCEMG – EPPI-Centre Cost Converter (v.1.6), all estimates of costs was converted to US dollars (USD) for consistency based on the International Monetary Fund source dataset for purchasing power parity values and same base-year as reported in the original study [34]. The data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers. For any disagreement that was present, consensus was sought where possible, and in cases where that were not possible, a third reviewer was assigned. Data was analysed qualitatively due to the heterogeneity of studies included in the systematic review, and meta-analysis was not attempted. Where applicable, data was analysed using descriptive statistics using Statistical Package of Social Science Version 27. The numerical data was analysed using mean and standard deviation, while the categorical data was analysed using frequency and percentage.

Results

Study characteristics and methodological quality of studies

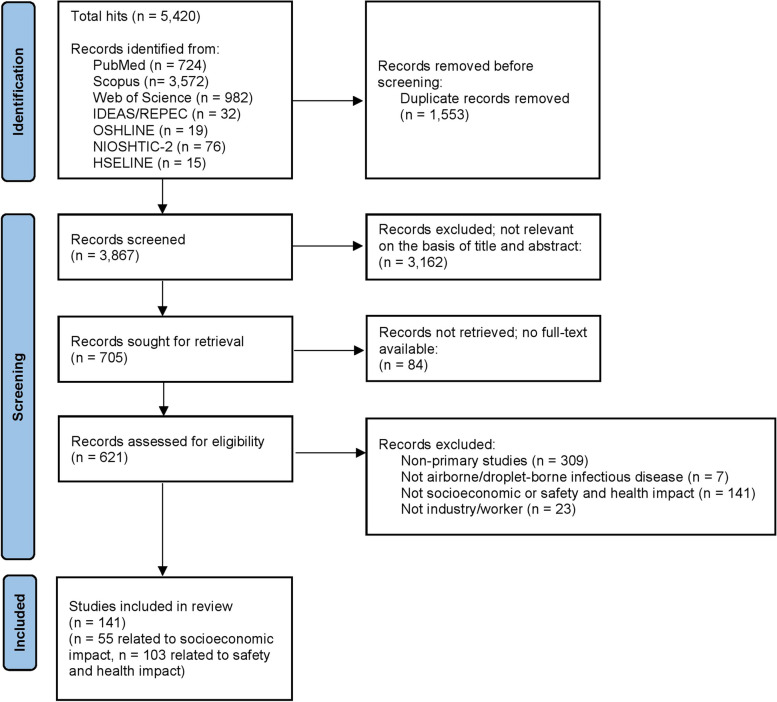

A total of 5420 articles were initially identified, and after removing duplicates, 3867 articles were screened. 3162 articles were excluded due to not being relevant on the basis of title and abstract. 84 articles were then excluded due to full-text non-availability. 480 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria, and a total of 141 articles were finally included. Of those, 55 studies were related to socioeconomic impact and were thus included in this review. The flow chart of the study search and selection is illustrated in Fig. 1, using the PRISMA format.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the systematic review based on the PRISMA statement

The summary of the studies included in this systematic review can be found in Table 1. The studies were published from 1984 to 2021, and were conducted in all parts of the world, including countries from North America (44%), South America (6%), Europe (24%), Asia (13%), Africa (4%), and Australasia (7%) regions, as well as globally (2%). Majority of studies (47%) were related to the healthcare industry, followed by multiple (31%), hospitality (5%), education (4%), transport (4%), agriculture (4%), construction (2%), chemical (2%), and commerce industries (2%). In terms of types of airborne or droplet-borne infectious diseases examined, the vast majority (62%) studied COVID-19, whereas 24% studied influenza (24%), followed by influenza A (H1N1) (9%), SARS (4%), tuberculosis (2%) and norovirus (2%).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies examining socioeconomic impact of airborne and droplet-borne infectious disease on industries

| Author (Year) / Location | Industry | Type of Infectious Disease | Year(s) Outbreak/Epidemic/Pandemic Occurred | Study Design | Study Population (N) | Study Variables | Study Instruments/Method | Socioeconomic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akazawa et al. (2003) [35] / USA | Multiple | Influenza | 1996 | Cross-sectional study | Workers across USA (N = 7037) | Absenteeism, work loss | 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data modelling |

1. The average number of workdays missed due to ILI was 1.30 days 2. The average work loss was valued at USD137 per person |

| Al-Ghunaim et al. (2021) [36] / UK | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Qualitative study | Surgeons across UK (N = 141) | Productivity, employee engagement | Qualtrics survey tool and thematic analysis |

1. Participants reported being less productive and slower at work 2. Participants reported decreased motivation levels at work |

| Alsharef et al. (2021) [37] / USA | Con-struction | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Qualitative study | Professional organizations subject matter experts (N = 34) | Supply chain disruption, supply cost, production cost, service disruption, employment, workforce size, productivity, absenteeism, demand shock | Semi-structured interview |

1. Containment measures included provision of temporary shutdown and quarantining, PPE, and COVID-19 related training 2. Material shortages and material price escalation 3. Delays in material delivery, which caused significant schedule disruptions 4. Increased production cost due to need to offer larger compensations to subcontractors and additional cost and overhead 5. Large number of furloughs and layoffs due to cash flow challenge and workload reduction 6. Reduced workforce due to social distancing recommendations and absenteeism 7. Loss in productivity and efficiency 8. Increased demand for home improvement and renovation products and supplies from local supplier and manufacturers |

| Banerjee et al. (2021) [38] / global | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Longi-tudinal study | Oncology professionals from 101 countries (N = 1520 survey I, N = 272 survey I & II) | Productivity | Job Performance since COVID-19 tool | 1. 49% participants reported that they were unable to do their job to the same standard compared with pre-COVID-19 period |

| Bergeron et al. (2006) [39] / Canada | Health-care | SARS | 2003 | Cross-sectional study | Community nurses across Ontario (N = 941) | Workforce size, service disruption | Self-administered questionnaire and thematic analysis |

1. Containment measures included patient and visitor screening, and mandatory PPE 2. 66% participants cited staff shortages and program stoppages |

| Brophy et al. (2021) [40] / Canada | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Qua-litative study | Frontline HCW across Ontario (N = 10) | Workforce size, absenteeism | In-depth interview and thematic analysis |

1. Containment measures included PPE and sanization protocols 2. Increased staff shortages 3. Increased absenteeism among frontline HCW |

| Calvo-Bonacho et al. (2020) [41] / Spain | Multiple | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Workers covered by Spanish insurance company (N = 1,651,305) | Absenteeism, work loss | National Public Health System Register data analysis |

1. Dramatic increase of sick leave for respiratory diseases and infectious disease in March 2020 (4.9 cases vs 2.5 cases and 5.1 cases vs 1.3 cases per 1000 workers in 2020 vs. 2017, 2018, and 2019 respectively), representing 116% increase in total sick leave 2. The increased sick leave translated into an 40% increase of associated costs during the first trimester of 2020 compared with the same period of 2017–2019 (mean USD4374.81 vs. 3118.20 per 100 affiliated workers) |

| Caroll & Smith (2020) [42] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Case study | Hospital in Washington State (N = 1) | Financial loss, supply cost | 2019 hospital financial data analysis |

For duration of shift for 3-months: 1. 25–50% reduction in surgical volume resulting in USD12.46–24.9 million revenue loss, and 10–20% reduction in clinic volume resulting in USD0.64–1.29 million loss 2. Increase of USD107,040–535,198 in supply costs 3. Loss of USD124,480 (1% increase in ICU days) to a loss of USD2.49 million (20% increase in ICU days) due to substitution of acute care for critical care Per year: 1. Estimated financial loss of USD13–117 million/year |

| Challener et al. (2021) [43] / USA | Health-care | Influenza | 2009–2019 | Case study | Large academic medical centre workforce | Presenteeism, absenteeism | 2009–2019 biweekly institutional payroll data analysis |

1. ILI is a statistically significant predictor of unscheduled absences in both salaried and hourly workers (p < 0.01) 2. For every increase in ILI by 1% in the population of the state, hourly workers and salaried workers have an increase in percent of unscheduled absence hours of 0.14 and 0.04% respectively 3. For every increase in ILI by 1%, the proportion of paid hours that are worked increases by 0.2% (p = 0.04) in hourly workers |

| Considine et al. (2011) [44] / Australia | Health-care | H1N1 flu | 2009 | Cross-sectional study | EM and nursing staff across Australia (N = 618) | Absenteeism | Self-developed survey | 1. 35% participants reported ILI; the mean number of days away from work due to ILI was 3.73 (SD = 3.63) |

| Danial et al. (2016) [45] / Scotland | Health-care | Norovirus | 2013 | Case study | Hospital in Scotland (N = 1) | Work loss, healthcare cost | APEX system data analysis and economic analysis |

In the outbreak which occurred from January until March of 2013: 1. 30 HCW (3.10 cases per 1000 inpatient bed-days) were affected, i.e. developed gastroenteritis 2. Total cost of staff absence was USD16,232.42 3. Healthcare cost included loss due to empty beds (USD401,893.83), cleaning costs (USD5,021.52), incident management team (USD64,562.41), and laboratories (USD2,295.55) |

| Delaney et al. (2021) [46] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | University of Utah staff (N = 5030) | Employee engagement, productivity | Self-developed survey |

1. 21% participants moderately or very seriously considered leaving the workforce and 30% considered reducing hours 2. 39% participants felt their productivity decreased |

| Duarte et al. (2017) [47] / Chile | Health-care | Influenza | 2009 | Cross-sectional study | Employed, privately insured Chileans (N = 1.4 M) | Absenteeism, workforce size | Private health insurance claim data analysis |

1. Pandemic increased mean flu days missed by 0.042 days per person-month during the 2009 peak winter months (June and July), representing an 800% increase in missed days 2. Minimum of 0.2% reduction in Chile’s labour supply was observed |

| Escudero et al. (2005) [48] / Singapore | Health-care | SARS | 2003 | Cross-sectional study | Tan Tock Seng Hospital HCW (N = 4261) | Absenteeism | Surveillance data for staff on sick leave analysis |

1. Containment measures included surveillance 2. 4261 staff as of mid-Sept 2003 had episodes of staff MC for febrile illness 3. The rate of staff sick leave for febrile illness was 1.40 per 1000 staff-days observed 4. There were 57 cases of deaths with pneumonia |

| Fargen et al. (2020) [49] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Neurointerven-tional physician organization members (N = 151) | Employment | Self-developed survey |

1. COVID-19-positive infections occurred in 1% of respondents, and an additional 8% were quarantined for suspected infection. 2. 1% participants reported their employment position being terminated or furloughed 3. 30 and 23% participants reported reduction of 25% or less and greater than 25% of normal compensation respectively |

| Gashi et al. (2021) [50] / Kosovo | Multiple | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Micro, small, medium and large business enterprise workers (N = 205) | Employment, financial loss, supply chain disruption | Self-developed survey |

1. National containment measures included lockdown, closure of borders, and restriction of free movement 2. 37% participants had laid off employees: 25% have laid off 1–4 employees, 8% 5–10 employees, and 3% 11–90 employees 3. On average, microenterprises incurred losses of USD32,643.53, small enterprises USD316,624.61, medium enterprises USD804,205.05, and large companies USD864,353.31 4. 90% participants (40.5% greatly, 28% somewhat, and 22% a little) reported that they were affected by supply of materials |

| Gray et al. (2021) [51] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Longi-tudinal study | Critical care physicians across US (N = 2375 T0, N = 1356 T1) | Workforce size | Self-developed survey |

1. Substantial shortages of ICU-trained staff reported in T0, although declining slightly, persist in T1; 48% in T0 vs. 47% in T1 2. The largest staffing shortage reported for both T0 and T1 was in ICU-trained nurses (34% in T0 vs. 33% in T1) |

| Groenewold et al. (2013) [52] / USA | Multiple | H1N1 flu | 2009 | Cross-sectional study | Full-time US workers (N = 60,000 households) | Absenteeism | Current Population Survey database analysis |

1. There was a significant (p < .01) increase in health-related absenteeism among full-time workers above baseline, corresponding with pandemic peak in national occurrence of ILI 2. Total one-week absenteeism ranged from 2 to 4% 3. Peak workplace absenteeism was correlated with the highest occurrence of both ILI and influenza-positive laboratory tests |

| Groenewold et al. (2019) [53] / USA | Multiple | Influenza | 2017–2018 | Cross-sectional study | Full-time US workers (N = 60,000 households) | Absenteeism | Current Population Survey database analysis |

1. Prevalence of health-related work absenteeism among full-time workers peaked at 3.0% (95% CI 2.8–3.2%) in January 2018 2. Regional absenteeism peaks corresponded to concurrent peaks in ILI activity |

| Groenewold et al. (2020) [54] / USA | Multiple | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Full-time US workers (N = 60,000 households) | Absenteeism | Current Population Survey database analysis |

1. In March and April 2020, prevalence of health-related workplace absenteeism among all full-time workers estimates exceeded the epidemic threshold 2. In April 2020, absenteeism among the following occupational subgroups significantly exceeded their occupation-specific epidemic thresholds: personal care and service (include childcare workers and personal care aides) (5.1% [95% CI = 3.5–6.7]), healthcare support (5.0% [95% CI = 3.1–6.8], production (3.7% [95% CI = 2.7–4.7], transportation and material moving occupations (include bus drivers and subway and streetcar workers) (3.6% [95% CI = 2.6–4.6], and healthcare practitioner and technical occupations (2.8% [95% CI = 2.0–3.6] |

| Haidari et al. (2021) [55] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | California Mat-ernal/Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative webinar atten-dees (N = 288) | Work error, productivity | Self-developed survey |

1. 12% participants reported increased medical errors 2. 59% participants reported difficulty meeting home and work responsibilities |

| Hammond & Cheang (1984) [56] / USA | Health-care | Influenza | 1980–1981 | Cross-sectional study | Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre hospitals HCW (N = 1600) | Absenteeism, work loss | Hospital records data analysis |

1. Comparisons between the peak 2-week periods of absenteeism during the epidemic and baseline “control” period showed increase in absenteeism rate during the epidemic (0.0586 vs 0.0346) 2. The total salary paid out for sick leave in the 2-week period of peak absenteeism during the epidemic was much greater than that paid out in the comparable period the next year when no influenza epidemic occurred (USD60,776.13 vs. USD36,290.00) |

| Harrop et al. (2021) [57] / USA | Education | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | US early career university researchers (N = 150) | Productivity | Self-developed survey | 1. 85% participants reported a loss of productivity compared to “normal”, with the majority reporting they were currently working between 41 and 60% (33% participants) or 61–80% (38% participants) productivity |

| Hasan et al. (2021) [58] / Bangladesh | Agri-culture | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Farmers, middlemen and consumers across Dhobaura (N = 280) | Production cost, financial loss, employment, demand shock | Self-developed survey |

1. The total production costs (primary fixed costs, operation costs, feed costs, medicinal costs) has increased since the pandemic and gross margins reduced 2. To reduce labour costs, 80% of farms reduced staff; the number of staff employed decreased from 209 to 149 following the pandemic (median change − 1.5). Overall mean labor cost/day dropped from USD 3.93 to USD 3.52 (> 10% fall) 3. The finfish farmers were receiving less profits, suffering a real price reduction of USD0.16/kg. By contrast, the middlemen have increased their selling prices, presumably to offset increased costs and maintain profitability 4. Small decrease in demand for dish; fish main protein source for 85% respondents pre-COVID, which dropped to 64.2% after the pandemic, and the amount of fish purchased decreased with a reduction in consumers buying over 5 kg from 46.7 to 30% between pre- and post-COVID |

| Hemmington & Neill (2021) [59] / New Zealand | Hospitality & Tourism | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Senior industry executives from 105 restaurants, café, take-away outlet (N = 11) | Financial loss, demand shock, production cost, employment, business disruption | Self-developed qualitative survey |

1. National containment measures: COVID-19 Alert Level 1–4 2. No tourism and no large concert gatherings led to lower demand 3. As COVID-19 level rose, café incomes declined 4. As customers decreased, there was increased “spend per head” 5. Many staff laid off 6. Operators with low margins and poor cashflow have gone out of business |

| Iacus et al. (2020) [60] / Italy | Transport | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Global aviation sector | Demand shock, GDP loss, work loss | Forecasting modelling based on past pandemic crisis and observed flight volumes |

1. Travel ban imposed since start of pandemic led to demand shock 2. At the end of 2020 the GDP loss globally could be as high as 1.41–1.67% and job losses may reach the value of 25–30 millions in the worst case scenarios 3. Focusing on EU27, the GDP loss may amount to 1.66–1.98% by the end of 2020 and the number of job losses from 4.2 to 5 million in the worst case scenarios |

| Jazieh et al. (2021) [61] / Middle-east, North Africa, Brazil, Phillipines | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Middle-east, North Africa, Brazil, Phillipines oncologists (N = 1010) | Productivity | Self-developed survey |

1. 3% of participants contracted COVID-19 infection 2. 34% participants reported negative pandemic impact on their research productivity |

| Jha et al. (2020) [62] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians members (N = 100) | Employment, financial loss, employee engagement, business disruption | Self-developed survey |

1. 56% participants have reduced staffing through furloughs and/or layoffs, and 68% have reduced hours per staff 2. 91% participants have seen reduction in collections 3. 55% participants reported that feelings of burnout have made them want to quit practicing medicine 4. 19% participants reported having had to close office |

| Jiménez-Labaig et al. (2021) [63] / Spain | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Spanish oncology doctors (N = 243) | Employee engagement | Self-developed survey |

1. 17% participants reported having been infected with SARS-CoV-2 2. 23% participants reported doubts about their medical vocation |

| Jones et al. (2021) [64] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | US health system pharmacists (N = 484) | Employment | Self-developed survey | 1. 1, 6, and 17% participants reported having lost their job, being furloughed, and decreased salary respectively |

| Karatepe et al. (2021) [65] / Turkey | Hospitality & Tourism | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | 2 Turkish national 5-star hotels worker (N = 150) | Absenteeism | Autry & Daugherty (2003) absenteeism item | 1. COVID-19 pandemic significantly associated with absenteeism among participants (p < 0.01) |

| Karve et al. (2013) [66] / USA | Multiple | Influenza | 2000–2009 | Cross-sectional | MarketScan CCAE and HPM database workers (N = 40 M) | Healthcare cost, work loss | 2 MarketScan databases 2000–2009 data analysis |

1. The average per-patient influenza-related medical cost (ILI-related medical, inpatient, outpatient, physician office, emergency department, pharmacy, ancillary care utilization and costs) ranged from USD239.43 to USD300.83 2. 30% participants with influenza diagnosis had > 1 day of influenza-related work absence during the nine influenza seasons studied 3. The average per-patient cost associated with influenza-related work absence, across all seasons studies, was USD209.66 4. The cost of average influenza-related productivity losses per 100,000 plan members, across all seasons studied, was USD42.58 |

| Keech et al. (1998) [67] / UK | Chemical | Influenza | 1994–1995 | Longi-tudinal study | Large UK pharmaceutical company workers (N = 411) | Absenteeism, presenteeism, work loss, healthcare cost | Self-developed questionnaire and diary card |

1. The mean number of missed workdays was 2.8 days, with means ranging from 3.2 days for secretarial/administrative staff to 1.8 days for managers 2. For those who returned to work while symptomatic, 81% felt only moderately effective 3. 73% participants reported that the illness had interfered with work in or around the home ‘all or most of the time’ 4. Overall total cost of missed work days was an estimated USD159,769.67 5. Overall healthcare cost (pharmacist consultation, GP visits and consultations, ED visits, hospitalization, medication) for participants was estimated USD2,512.16 |

| Lee et al. (2008) [68] / Hong Kong | Hospitality & Tourism | Influenza | 2007 | Cross-sectional study | Hong Kong corporation staff (N = 2212) | Work loss, productivity | Self-developed survey |

1. Average equivalent days of perfect health loss per person per year was 10.71 days 2. Average productivity loss per person per year was USD152.12 |

| Leigh (2011) [69] / USA | Multiple | Tuber-culosis | 2007 | Longi-tudinal study | Workers across USA | Heathcare cost | Primary and secondary national data analysis |

1. In 2007, the number of deaths due to pulmonary tuberculosis was 25 2. In 2007, the medical cost for pulmonary tuberculosis was USD0.07 billion |

| Lim et al. (2020) [70] / Australia | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Emergency physicians (N = 32) | Productivity | Hospital administration database analysis | 1. 49% reduction in productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic from previously published data (p < 0.0001) |

| Matsuo et al. (2021) [71] / Japan | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross sectional study | Tertiary hospital HCW (N = 660) | Employee engagement | Self-developed survey | 1. 65% participants had dropout intentions |

| Mosteiro et al. (2020) [72] / Spain, Brazil, Portugal | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Primary health care and hospitals nurses (N = 659) | Presenteeism | SPS-6 | 1. Prevalence of presenteeism was 55, 36 and 30% for Portugese, Brazilian and Spanish participants respectively |

| Noorashid & Chin (2021) [73] / Brunei | Hospitality & Tourism | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Qualitative study | Community-based tourism owners (N = 16) | Business disruption, financial loss, demand shock | Semi-structured interview |

1. National containment measures included lockdown and movement restrictions 2. Demand shock due to movement restriction and risk aversion 3. Participants reported disruption to local businesses, reduced earnings, and financial difficulties |

| Novak et al. (2021) [74] / Croatia and Serbia | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Pharmacists (N = 574) | Productivity | Self-developed survey |

1. Containment measures included isolation (working behind acrylic glass partitions), PPE, temperature screening, provision of hand sanitizer and disinfection of work area 2. 25% participants reported negative effect on productivity due to changes in working conditions |

| Palmer et al. (2010) [75] / USA | Multiple | Influenza | 2007–2008 | Cohort study | Retail, manu-facturing and transport staff (N = 2013) | Absenteeism, presenteeism | Self-developed survey; items adapted from HPQ |

1. The incidence of employee ILI ranged from 4.8 to 13.5% 2. Employees reporting ILI reported more absences than employees not reporting ILI (72% vs 30%, respectively; p < 0.001) 3. An average of 1.7 days of work absence were attributable to ILI 4. Mean ILI-related presenteeism was 2.5 hours |

| Richmond et al. (2020) [76] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Southeastern Surgical Congress members (N = 183) | Employment, productivity | Self-developed survey |

1. Practices reduced staffing through paid time off (48%), furlough (40%), and termination (7%). Most participants predicted annual compensation would be moderately reduced (63.4%) 2. Participants estimated clinical productivity would be moderately reduced (48%) or extremely reduced (42%) |

| Schanzer et al. (2011) [77] / Canada | Multiple | Influenza/H1N1 flu | 2009 | Cross-sectional study | Household | Absenteeism |

Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey data analysis |

1. Hours lost due to the H1N1/09 pandemic strain more than seasonal influenza (0.2% of potential hours worked annually) 2. Estimated 0.08% of hours worked annually were lost due to seasonal influenza illnesses 3. Absenteeism rates due to influenza were estimated at 12% per year for seasonal influenza over the 1997/98 to 2008/09 seasons, and 13% for the two H1N1/09 pandemic waves 4. Employees took an average of 14 hours off due to a seasonal influenza infection, and 25 hours for the pandemic strain |

| Slone et al. (2021) [78] / USA | Health-care | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Mental health providers (N = 500) | Employment | Self-developed survey | 1. 22, 21, and 0.2% participants reported reduced pay, being furloughed, and laid off respectively |

| Tilchin et al. (2021) [79] / USA | Multiple | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Amazon’s MTurk service worker (N = 220) | Presenteeism | Self-developed survey | 1. 35% participants reported an intention to still work if they felt a little sick with COVID-19 due to financial strain |

| Torá-Rocamora et al. (2011) [80] / Spain | Multiple | H1N1 flu | 2009 | Cohort study | Catalonia workers (N = 3,157,979) | Absenteeism | Time series analysis of surveillance data |

1. Containment measures included surveillance 2. Influenza activity peaked earlier in 2009 and yielded more cases than in previous years. Week 46 (in November 2009) had the highest number of new cases resulting in sickness absence (endemic-epidemic index 20.99; 95% CI 9.44 to 46.69) |

| Tsai et al. (2014) [81] / USA | Multiple | Influenza | 2007–2009 | Cross-sectional study | Privately insured workers (N = 1,860,562,007–2008, N = 1,953,662,008–2009) | Absenteeism | MarketScan database analysis |

1. There were 2406 ILI-related work absence records in 2007–2008 and 1675 in 2008–2009 2. The mean work-loss hours per ILI were 23.6 in 2007–2008 and 23.9 in 2008–2009 3. Work-loss hours per episode were greater if the ILI episode was associated with hospitalization: 47.0 in 2007–2008 and 46.1 in 2008–2009 |

| Turnea et al. (2020) [82] / Romania | Multiple | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Company decision-makers (N = 203) | Demand shock, service disruption, employment, financial loss, supply chain disruption, supply cost | Self-developed survey adapted from ILO |

1. Containment measures included state of emergency declaration, and quarantine of workers 2. 29% companies stopped operations 3. 81% companies reported that demand is lower than normal 4. 18% companies dismissed workers due to COVID-19 crises; 9, 2, 2, 2 and 3% dismissed 1–10%, 11–20%, 21–30%, 31–40% and over 41% workers respectively 5. 52% companies had workers on temporary leave (furlough); 4, 5, 2, 5 and 35% sent 1–10%, 11–20%, 21–30%, 31–40%, and over 41% to furlough respectively 6. 17, 27 and 44% companies reported low, medium, and high level of financial impact on business and company operations respectively 7. 9, 12, 7, 6 and 45% companies reported 10–20%, 21–30%, 31–40%, 41–50, and 51% and over average monthly revenue decrease since state of emergency established 8. 40% companies reported that raw materials are not in stock or their purchase has become very expensive |

| Van der Feltz-Cornelis et al. (2020) [83] / UK | Education | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | University staff (N = 1055) | Absenteeism, presenteeism | iPCQ |

1. 7% participant reported sickness absenteeism 2. 26% participant experienced presenteeism |

| Van der Merwe et al. (2021) [84] / South Africa | Agri-culture | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Wildlife ranching members (N = 601) | Demand shock, financial loss, employment | Self-developed survey |

1. National containment measures included total lockdown 2. The estimated financial impact of COVID-19 on the private wildlife industry is USD0.99 billion 3. Average financial loss due to cancellations of hunters and ecotourist (> 77%) was USD122,100 4. The total loss in live game sales and game meat sales over the lockdown approximately USD80 million 5. 33% employees received reduced wages, 21% had to take unpaid leave, and 19% were laid off |

| Van Wormer et al. (2017) [85] / USA | Multiple | Influenza/H1N1 flu | 2012–2016 | Cross-sectional study | Marshfield workers (N = 1278) | Productivity | WPAI |

1. There were 470 (37%) cases of influenza among workers, 179 (38%) of which are H1N1 flu 2. Influenza was significantly associated with workplace productivity loss (P < 0.001) 3. Regardless of vaccination, participants with A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, or B infection had the greatest mean productivity loss (range, 67 to 74%), while those with non-influenza ARI had the lowest productivity loss (58 to 59%) |

| Webster et al. (2021) [86] / Central America | Multiple | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Longi-tudinal study | El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras & Nicaragua workers (T1 N = 808, T2 N = 827) | Employment, financial loss | World Bank enterprise survey, COVID-19 survey |

1. Substantial total reduction (11.7%) in employment reported by firms both at T1 and T2; huge loss of employment for the hospitality sector (T1 41%, T2 26%), whereas some sectors reported increases in employment compared to pre-pandemic (e.g. chemicals, rubber) 2. All 4 countries reported average temporary closure of > 5 weeks at T1, implying overall loss of 322,000 labour weeks. At T2, an average of further temporary closures of 2.9 weeks was reported, with an implied loss of 159,000 labour weeks 3. Workers furloughed ranged from 11 to 30% in four countries 4. 26% of firms reduced the salaries of their employees and almost a third (32%) reduced hours of work 5. Average change in sales for firms was a reduction of just under one quarter of their sales one year previously |

| Widodo et al. (2020) [87] / Indonesia | Transport | COVID-19 | 2020-current | Cross-sectional study | Engineering employees (N = 65) | Productivity | Self-developed survey |

1. Containment measures included isolation policy, and physican distancing 2. R2 value (0.681) indicate that job stress and Covid-19 simultaneously affect workers’ productivity by 68%; with Covid-19 stress parameters being more influential than job stress on productivity |

| Yohannes et al. (2003) [88] / Australia | Multiple | Influenza | 2002 | Cross-sectional study | Australian workers | Absenteeism | National survei-llance system data analysis |

1. National containment measures included surveillance 2. Data suggested an association between the peak in influenza activity and absenteeism 3. Influenza was responsible for 9825 hospital days in 2000–2001 |

| Zaffina et al. (2019) [89] / Italy | Health-care | Influenza | 2016–2018 | Cross-sectional study | Paediatric hospital HCW (2016 N = 2090, 2017 N = 2097) | Absenteeism, work loss | Hospital record data analysis |

1. The average absenteeism rate recorded a difference of 0.95 and 0.96 sickness absence days, respectively, between non-epidemic and epidemic periods 2. The total amount of days lost is 690.1 and 795.3 in 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 epidemic periods, respectively, for a total of 1.485,4 days lost 3. A total cost of USD 161,621.49 and USD 186,047.94 were calculated for 2016–2017 and 2017–2018, respectively |

ARI acute respiratory infection, COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019, EM emergency medicine, GDP gross domestic product, HCW healthcare workers, HPQ World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire, H1N1 influenza A virus subtype H1N1; ICU intensive care unit, ILI influenza like illness, ILO International Labour Organisation, iPCQ iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire, PPE personal protective equipment, SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SD standard deviation, SPS-6 Stanford Presenteeism Scale, WPAI Work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire

Most studies (47%) were assigned either a level of 3a or 3b according to the CCHMC’s Table of Evidence Levels, with 3a indicating a better-quality study than 3b, though of lower-level evidence than 1a/1b and 2a/2b. Meanwhile, several studies (36%) were assigned either a level 4a or 4b, 13% of studies either a level 2a or 2b, and 4% of studies a level 5a. According to the JBI and CEBMa tools, most studies (84%) were of good/excellent quality. The average score and range score for included studies according to the star system were as follows: (1) analytical cross-sectional studies (n = 22): average score 5.6, range score 3 to 8, (2) qualitative study (n = 6): average score 7, range score 6 to 8, (3) longitudinal studies (n = 5): average score 5.8, range score 3 to 7, (5) case study (n = 3): average score 7.3, range score 6 to 8, (6) prevalence study (n = 18): average score 7.3, range score 6 to 9, and (7) case control study (n = 1): score 6. The most frequent study design was analytical cross-sectional study (40%), followed by prevalence study (33%), qualitative study (11%), longitudinal study (9%), case study (4%), case control study (2%) and cohort study (2%). Sample sizes varied widely, ranging from 11 to 3,157,979. Of those that conducted primary studies (n = 34), majority (68%) utilised self-developed surveys as the mode of data collection, whereas a smaller number utilised validated tools (24%), qualitative methods (9%) and diary card (3%). Of those that performed economic analysis (n = 20), data analysis was performed using data retrieved from national databases (50%), hospital databases (35%), public or private insurance databases (10%), and online databases (5%). On the whole, the quality of evidence from this systematic review can be rated as good. A summary of the methodological quality of included studies is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality of included studies according to CCHMC Table of Evidence Levels, JBI tools, and CEBMa tool

| Author (Year) | Study Design | LOE | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Overall Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akazawa et al. (2003) [35] | ACS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent |

| Al-Ghunaim et al. (2021) [36] | QS | 2a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Good | ||||

| Alsharef et al. (2021) [37] | QS | 2a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Good | |||

| Banerjee et al. (2021) [38] | LS | 3a | N/A | N/A | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | * | Good | ||

| Bergeron et al. (2006) [39] | QS | 2a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Good | ||||

| Brophy et al. (2021) [40] | QS | 2a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Good | |||

| Calvo-Bonacho et al. (2020) [41] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Carroll & Smith (2020) [42] | CS | 5a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Good | ||||

| Challener et al. (2021) [43] | ACS | 4b | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | ||||

| Considine et al. (2011) [44] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Danial et al. (2016) [45] | CS | 5a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Excellent | ||

| Delaney et al. (2021) [46] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Duarte et al. (2017) [47] | ACS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Escudero et al. (2005) [48] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Fargen et al. (2020) [49] | ACS | 4b | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | ||||

| Gashi et al. (2021) [50] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | |||

| Gray et al. (2021) [51] | LS | 3a | N/A | N/A | * | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | * | Excellent | |

| Groenewold et al. (2013) [52] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Groenewold et al. (2019) [53] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Groenewold et al. (2020) [54] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Haidari et al. (2021) [55] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Hammond & Cheang (1984) [56] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Harrop et al. (2021) [57] | ACS | 3b | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | |||||

| Hasan et al. (2021) [58] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Hemmington & Neill (2021) [59] | QS | 2a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Excellent | ||

| Iacus et al. (2020) [60] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Jazieh et al. (2021) [61] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Jha et al. (2020) [62] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | |||

| Jiménez-Labaig et al. (2021) [63] | ACS | 4b | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | ||||

| Jones et al. (2021) [64] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Karatepe et al. (2021) [65] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Karve et al. (2013) [66] | LS | 3a | N/A | N/A | * | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | Good | ||

| Keech et al. (1998) [67] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Excellent |

| Lee et al. (2008) [68] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | |||

| Leigh (2011) [69] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Excellent |

| Lim et al. (2020) [70] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Matsuo et al. (2021) [71] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Mosteiro-Diaz et al. (2020) [72] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Noorashid & Chin (2021) [73] | QS | 2a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Excellent | ||

| Novak et al. (2021) [74] | ACS | 4b | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | ||||

| Palmer et al. (2010) [75] | Cohort study | 2a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Excellent | ||

| Richmond et al. (2020) [76] | ACS | 4b | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | ||||

| Schanzer et al. (2011) [77] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Slone et al. (2021) [78] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Good | |||

| Tilchin et al. (2021) [79] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Torá-Rocamora et al. (2011) [80] | LS | 3a | N/A | N/A | * | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | * | Excellent | |

| Tsai et al. (2014) [81] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Excellent | |

| Turnea et al. (2020) [82] | ACS | 4b | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | |||||

| Van der Feltz-Cornelis et al. (2020) [83] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Good | ||

| Van der Merwe et al. (2021) [84] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | |||

| Van Wormer et al. (2017) [85] | ACS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Excellent |

| Webster et al. (2021) [86] | LS | 3b | N/A | N/A | * | N/A | * | * | Moderate | |||||

| Widodo et al. (2020) [87] | ACS | 4b | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | |||||

| Yohannes et al. (2003) [88] | PS | 3a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | N/A | Good | |||

| Zaffina et al. (2019) [89] | CCS | 4a | * | * | * | * | * | * | N/A | Good |

ACS analytical cross-sectional study, CCS case-control study, CS case study, LOE level of evidence, LS longitudinal study, PS prevalence study, QS qualitative study, * star awarded, N/A not applicable

(1) The CCHMC Table of Evidence classifies level of evidence for individual studies by study design, domain, and quality, with level 1 representing the highest level and indicating the strongest evidence, and level 5 representing the lowest level and indicating the weakest evidence. In addition, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tools and Center of Evidence Based Management (CEBMa) case study critical appraisal checklist were used to further subclassify studies at each level to either “a” or “b”, which signifies good quality and lesser quality study respectively in terms of methodological quality

(2) Some questions are indicated as N/A because the quality tool for that specific study design has a certain number of quality appraisal checklist, e.g., JBI for ACS has 8 quality appraisal checklists, and Q9 to Q11 do not apply

Socioeconomic impacts of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases in industries

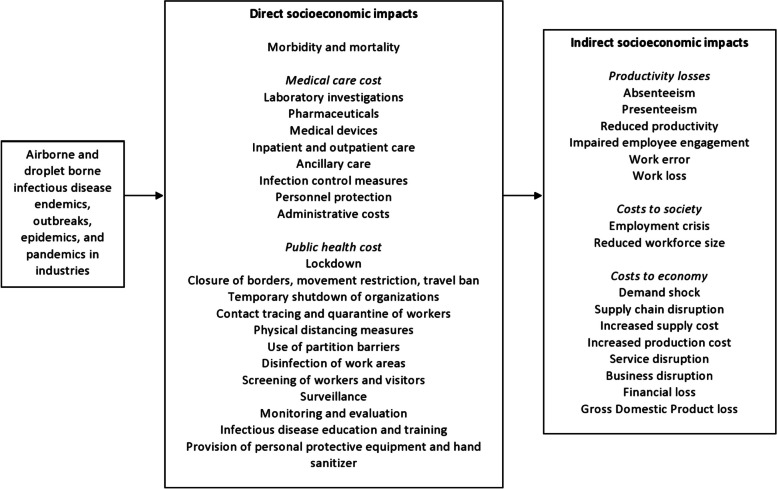

A variety of socioeconomic impacts were reported by studies included in this review, as outlined in Fig. 2. They include direct impacts, i.e. repercussions occurring during the hazard event, as well as indirect impacts, i.e. subsequent changes given the direct impact [90].

Direct impacts of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases in industries

Fig. 2.

Framework for socioeconomic impact of airborne and droplet-borne infectious disease on industries based on empirical findings

Direct socioeconomic impacts such as morbidity and mortality and its associated healthcare costs due to infectious diseases outbreaks were reported by included studies. Exposure to influenza, influenza A (H1N1), SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 viruses, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and norovirus had resulted in influenza like illness (ILI), febrile illness, pneumonia, COVID-19 infection, pulmonary tuberculosis, and gastroenteritis among workers [45, 48, 49, 61, 63, 69, 75, 85]. Moreover, a small percentage of those who developed pneumonia from exposure to SARS-CoV virus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis had succumbed to death [48, 69].

In addition, substantial healthcare costs were reported because of these outbreaks. During influenza epidemics, the average per-patient influenza-related medical cost ranged from USD239 to USD301, whereas the total healthcare expenditure for workers of a United Kingdom (UK) pharmaceutical company amounted to USD2,512.16, due to ILI-related medical, inpatient, outpatient, general practitioner/physician office, emergency department, pharmacy, and ancillary care utilization and costs [66, 67]. Meanwhile, the average medical costs due to hospital, professional services, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and nursing homes for workers with pulmonary tuberculosis was reported to amount to USD0.07 billion in 2017 [69]. Included studies had also highlighted public health costs taken to contain infectious diseases outbreaks such as lockdown, closure of borders, restriction of free movement, travel ban, temporary shutdown of organisations, screening of workers and visitors, quarantining of workers, physical distancing measures, use of partition barriers, infection control and disinfection of work areas, infectious disease-related training, provision of personal protective equipment and hand sanitizers, and surveillance [37, 39, 40, 48, 50, 59, 60, 73, 74, 80, 82, 84, 87, 88]. To control the three-month norovirus outbreak in a Scottish hospital, the healthcare costs included cleaning costs (USD5,021.52), incident management team (USD64,562.41), and laboratories (USD2,295.55) [45].

-

b)

Indirect impacts of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases in industries

Following the impacts above, indirect socioeconomic impacts of infectious diseases outbreaks including productivity losses, costs to society, and costs to economy were also reported. Absenteeism was observed among workers across multiple industries during influenza, H1N1 flu, SARS, and COVID-19 outbreaks. Workers who were exposed to influenza had 1.3 to 2.8 workdays missed and 14.0 to 23.9 work hours lost per ILI [35, 43, 53, 67, 75, 77, 81], and there was a 800% increase in absenteeism rate during epidemics compared to non-epidemic periods [47, 56, 88, 89]. Compared to seasonal influenza, hours lost due to the H1N1 pandemic strain were higher (0.2% of potential hours worked annually) [77], and workers with H1N1 flu had 3.73 workdays missed and 25 hours work hours lost [44, 52, 77, 80]. Meanwhile, exposure to SARS had resulted in 1.4 missed workdays per 100 staff-days observed [48]. Finally, an average of 4.9 cases of sickness leave per 1000 workers were observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which represented a dramatic increase compared to previous years (4.9 cases vs 2.5 cases per 1000 workers in March 2020 vs. 2017, 2018, and 2019) [41, 54, 65, 83]. All activity sectors were impacted, with the highest rate of absenteeism observed among workers in the healthcare, services, production, and transportation industries [41, 54].

Concurrently, presenteeism among workers was also reported during influenza, H1N1 and COVID-19 outbreaks [43, 67, 72, 79, 83]. During the influenza/H1N1 flu epidemic, 73% workers reported that the illness had interfered with work, 81% workers who had returned to work while symptomatic felt only moderately effective, and a mean productivity loss ranging from 67 to 74% was reported [67, 85]. This culminated in workers with ILI being less productive for 4.8 hours each day worked while ill (2.5 hours each day with ILI symptoms) [75]. Meanwhile, workers across industries reported being less productive and efficient at work during the COVID-19 pandemic, which amounted to a 49% reduction in productivity from previously published data (p < 0.0001) [36–38, 46, 55, 57, 61, 70, 74, 76, 87]. For healthcare workers in particular, in addition to productivity losses during the pandemic, impaired work quality and reduced employee engagement were also observed [36], as 12% reported increased medical errors [55], 23% had doubts about their medical vocation [63], and 21 to 65% had moderate or very serious consideration about leaving the workforce [46, 62, 71].

Correspondingly, increased costs to industries in the form of work loss were observed during infectious diseases outbreaks. In the USA, the total salary paid out for sickness absenteeism in the two-week period of peak absenteeism during the epidemic were much greater compared to non-epidemic periods (USD60,776 vs. USD36,290) [56], and the average work loss and influenza-related productivity loss were valued at USD137 per person [35] and USD42,581 per 100,000 health plan member [66] respectively. In the UK, the overall total cost of missed workdays for ILI among workers of a large UK pharmaceutical company was valued at USD159,769.67 [67]. Meanwhile, work loss due to exposure to influenza resulted in a total cost of USD161,621.49 and USD186,047.94 for 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 respectively in Italy [89], and led to USD152.12 average productivity loss per person per year in Hong Kong [68]. On the other hand, the total cost of staff absence due to norovirus exposure was estimated to be USD16,232.42 [45]. Finally, the increased sick leave during COVID-19 pandemic had translated into USD4374.81 per 100 affiliated workers across industries [41].

In terms of costs to society, employment crises and reduced workforce size were reported by included studies, especially in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. Studies reported workers across industries being terminated (0.2–41%), furloughed (6–56%), or made to go on paid time off (48%) during the COVID-19 pandemic [49, 50, 58, 59, 62, 64, 76, 78, 82, 84, 86]. During this period, companies across multiple industries had also reduced either the salaries (17–33%) or hours of work (32–68%) of their employees [62, 64, 78, 84, 86]. Correspondingly, studies had also reported reduced workforce size and staff shortages (48%) during the COVID-19 pandemic [37, 40, 51], which was similarly apparent during the SARS [39] and H1N1 flu epidemics [47]. A small number of industrial sectors (e.g. chemical, plastics and rubber industry) had however showed increases in employment during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to pre-pandemic periods [86]. In the aviation industry alone, job losses in the aviation industry had been forecasted to reach 25 to 30 million at the end of 2020 [60].

Costs to economy was also extensively reported by included studies, especially as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies conducted in multiple industries [82], including the transport [60], hospitality and tourism [59, 73], and agriculture industries [58, 84] reported demand shock during the COVID-19 pandemic due to movement restrictions, risk aversion, and lower consumerism. The exception to this is the study conducted in the construction industry, which had reported that there was increased demand for home improvement and renovation products and supplies from local supplier and manufacturers [37]. Disruptions to supply chain, services, as well as businesses were also observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies conducted across multiple industries described material shortages and delays in material delivery, which caused significant schedule disruptions [37, 50, 82] as well as cessation of operations during this time [62, 82]. This was similarly reported during the SARS outbreak, where healthcare workers had reported program stoppages [39]. Besides that, increased supply and production costs were also noted since the onset of COVID-19 pandemic. In the healthcare industry, an increase of USD107,040 to USD535,198 in supply costs were reported [42]. Similarly, the total production costs (primary fixed costs, operation costs, feed costs, medicinal costs) in the agriculture industry had also increased [58] and 40% companies across industries reported that raw materials were not in stock or their purchase has become very expensive [82].

The COVID-19 pandemic had also reportedly led to companies suffering financial losses. In the healthcare industry, the reduction in surgical and clinic volume as well as substitution of acute care for critical care in a Washington hospital were estimated to result in revenue loss amounting to USD13 to 117 million per year [42]. In the agriculture industry, the estimated financial loss incurred due to cancellations of hunters and ecotourist as well as loss in live game sales and game meat sales over lockdown in South Africa were reported to amount to USD0.99 billion loss to the private wildlife industry, whereas finfish farmers across Dhobaura, Bangladesh described receiving less profits and suffering a real price reduction of USD0.16/kg [58, 84]. In the hospitality and tourism industry, café income had decreased in New Zealand and tourism owners in Brunei reported reduced earnings and financial difficulties, which had led to companies with low margins and poor cashflow going out of business [59, 73]. Meanwhile, across multiple industries in Central America, Romania, and Kosovo, firms observed 25% reduction in sales compared to the year previously [86], reduced average revenue since state of emergency was established [82], and losses of USD32,643.53, USD316,624.61, USD804,205.05, and USD864,353.31 for microenterprises, small enterprises, medium enterprises, and large companies respectively [50]. In the transport industry alone, GDP loss in the transport industry were forecasted to range from 1.41 to 1.67% globally by the end of 2020 [60].

Discussion

The primary aim of this systematic review was to determine the socioeconomic impacts of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases on industries. The findings of 55 studies encompassing multiple industries across the globe indicate that significant direct and indirect socioeconomic costs were incurred as a result of COVID-19, influenza, influenza A (H1N1), SARS, tuberculosis and norovirus outbreaks, as highlighted in Fig. 2. According to the framework derived from empirical findings, outbreaks of airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases in industries cause illnesses, deaths, high medical and public health costs, which in turn lead to significant productivity, social, and economic costs. These observations are in line with the model published by Phua (2005) [91], in which the most apparent costs following infectious diseases outbreaks include morbidity, mortality and direct costs of medical care and public health interventions, as well as indirect costs attributable to the loss of productivity resulting from morbidity, mortality, and related health interventions. Following the methodological assessment of included studies according to the JBI and CEBMa tools, the quality of evidence from this systematic review can be rated as good. Thus, the findings from this systematic review provide reasonably robust evidence of the socioeconomic impacts of airborne and droplet-borne diseases on industries.

As shown in this systematic review, airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases were significant causes of morbidity and mortality among workers, which ranged from self-limiting ILI from influenza infection to pneumonia from SARS infection to death from pulmonary tuberculosis. Concurrently, substantial costs incurred from the use of healthcare resources including healthcare expenditures for the diagnosis and treatment of workers, as well as public health preventive and control measures for managing the diseases at workplaces and communities. Indeed, influenza epidemics had accounted for USD1–3 billion, USD1.1 billion, USD300 million, and USD7.90 million in direct medical costs in USA, Germany, France and South Korea respectively [8, 92]. Meanwhile, the direct medical costs due to 2009 H1N1 pandemic were estimated at USD291.7 million, 37 times the costs compared to seasonal influenza [92], whereas the COVID-19 pandemic had led to a total direct medical cost of USD163.4 billion in the USA alone [93]. On the other hand, direct medical costs attributable to tuberculosis, an endemic disease, was USD0.07 billion [69]. In this regard, the morbidity and mortality of infectious diseases and associated health costs varied widely, and is dependent on multiple factors. These factors include the transmissibility, virulence, and case fatality rate of the pathogen, viral variants, national demography, prevalence of comorbidities, as well as the scale of the outbreak, public health capacity and response, and availability of treatment [94].

In addition to the direct costs of infectious diseases outbreaks, the indirect costs has been shown to be 5 to 10-fold greater than direct costs and stems largely from losses in work productivity [8]. In this study, the average workdays missed due to exposure to airborne and droplet-borne infectious diseases ranged from 1.3 to 3.73. This may be attributable not only to workers getting ill but also to risk aversion behaviours adopted by workers to prevent becoming infected [54]. Moreover, for large-scale infectious diseases outbreaks, sickness absence from school as well as closure of schools may lead to parents having to take time off work to care for their children [5, 8]. Concurrently, presenteeism, which had resulted in 49 to 74% reduction in productivity, was also reported in this study. This may be due to various factors, including professional obligation, “lack of cover”, job insecurity, high job demand, inflexible work condition, peer pressure, and presenteeism culture [95]. According to Smith et al. (1993) [96], even mild influenza had resulted in a reduction of reaction times by 20 to 40%, which may contribute towards impaired work performance with adverse effects on health and safety at work (e.g. medical errors) as observed in this study. Furthermore, studies suggest that the increased tendency of workers to remain indoors due to public health measures instituted during infectious diseases outbreaks may also adversely impact health and lead to poorer work performance, due to increased exposure to indoor air pollutants [97].

Due to the outbreak scale of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and COVID-19 pandemic, national policies such as lockdowns, movement restrictions, and restricting industries sector operation to only those considered essential services had to be undertaken in efforts to control the pandemic [92]. These measures, coupled with risk aversion among the general public, had led to supply shock due to temporary closure of businesses deemed non-essential, as well as demand shock due to decreased consumption and travel among the general public [98]. Due to the above, hundreds of millions of workers found themselves losing work, both in formal and informal labour markets [99]. As demonstrated in this study, workers across industries had reported being terminated, furloughed, made to go on paid leave, or having their wages or hours of work reduced during infectious diseases outbreaks. In the USA alone, nearly 6.6 million workers filed for unemployment benefits by the end of March 2020 due to COVID-19, disrupting a decade-long streak of growth in employment [98]. In this aspect, industries with high proportions of temporary jobs, inflexible working arrangements, and reliance on migrant workforces experienced greater labour losses [6, 100, 101]. As an aftermath of infectious diseases outbreaks, the employment crises may lead to more systemic long-term effect changes, including multiplier effects on employment, household income, and food security [6].

In terms of infectious diseases’ costs to economy, the health services, transport, hospitality and tourism industries were affected the most [5, 6, 102]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, countries’ health systems had been partly or entirely interrupted [102]. High numbers of active cases had overwhelmed the health delivery system and its capacity to maintain other essential health services [103]. Moreover, frontline healthcare providers were getting infected at a greater rate compared to the general public and the quarantine measures to control the spread of infectious diseases had resulted in shortage in healthcare staffing, further stressing the health system [6, 101]. Meanwhile, border closure, travel ban, suspension of flight operations globally, restrictions on public gatherings, as well as contagion fears had inhibited social and recreational activities and reduced spending activities, negatively impacting the transport, tourism and hospitality industries [4, 101, 102]. During the 2003 SARS outbreak, Asia-Pacific carriers and North American carriers saw USD6 billion and USD1 billion loss in revenue respectively [104], whereas H1N1 influenza led to USD2.8 billion loss in revenue for Mexico’s tourism industry [105]. The 2015 MERS outbreak in South Korea and Saudi Arabia had led to USD10 billion and USD5 billion loss in revenue respectively for the tourism industry [4, 106]. On a larger scale, the COVID-19 pandemic had led to an immediate collapse in demand in the global tourism and leisure industry, 50 million job loss globally, and USD2.86 trillion loss in revenue due to significant slumps in domestic and international tourism [5, 6, 107].

Closure of borders, reduced personal spending and demand for goods, and halts in non-essential imports during infectious diseases outbreaks had also led to demand shocks across multiple industries [6]. The 2015 MERS outbreak had resulted in 10, 8.6, 6.3, 2.4, 1.6, and 0.9% drop in production for the accommodation and food, entertainment and recreation, publishing, communication, and information, transportation and storage, wholesale and retail, and electricity and air conditioning sectors respectively [106]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, government-imposed shutdown had led to the temporary closure of major manufacturing companies across the globe, causing global supply chain disruptions for raw materials and intermediate products as well as disruptions in international and regional trade [5, 98, 108], which had led to material shortages, increased supply and production costs, as well as service disruptions as observed in this study. Indeed, entire systems including production, transportation, marketing, distribution and consumption had been adversely impacted, leading to reduced profit margins and financial strain on businesses [6, 98]. MSME, especially those reliant on intermediate goods imported from affected regions, faced greater difficulty in enduring the disruption [98]. Indeed, according to previous studies, almost all MSME in South Asia were unable to sustain themselves through lockdown and were forced to close their operations during the COVID-19 pandemic [6].

Other industries were not spared from infectious diseases outbreaks, as impacts on industries have knock-on effects on one another due to their interdependencies [98]. Indeed, as an aftermath to the 2003 SARS outbreak, restrictions and cancellation in the transport industry had impacted multinational industries such as oil, for which demand had reduced by 300,000 barrels a day in Asia [104]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, all sectors of the world economy had been affected [5], and in fact, it became a global systemic economic risk due to the high globalization and interconnectedness among the different industries and sectors of the economy [6, 101]. Nevertheless, a small number of industries had performed better during pandemic, reflecting changes in consumer spending and market behaviour [101]. For example, South Korea market chain stores reported increased online sales [4], and the food sector, including distribution and retailing, experienced huge demands on food products due to panic-buying and stockpiling of food among the general public [5]. Similarly, stay-at-home orders had contributed to the increased demand for home improvement and renovation products in the construction industry, as observed in this study.