Abstract

Application of cardiac patches to the heart surface can be undertaken to provide support and facilitate regeneration of the damaged cardiac tissue following ischemic injury. Biomaterial composition is an important consideration in the design of cardiac patch materials as it governs host response to ultimately prevent the undesirable fibrotic response. Here, we investigate a novel patch material, poly (itaconate-co-citrate-co-octanediol) (PICO), in the context of cardiac implantation. Citric acid (CA) and itaconic acid (ITA), the molecular components of PICO, provided a level of protection for cardiac cells during ischemic reperfusion injury in vitro. Biofabricated PICO patches were shown to degrade in accelerated and hydrolytic conditions, with CA and ITA being released upon degradation. Furthermore, the host response to PICO patches after implantation on rat epicardium in vivo was explored and compared to two biocompatible cardiac patch materials, poly (octamethylene (anhydride) citrate) (POMaC) and poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA). PICO patches resulted in less macrophage infiltration and lower foreign body giant cell reaction compared to the other materials, with corresponding reduction in smooth muscle actin-positive vessel infiltration into the implant region. Overall, this work demonstrates that PICO patches release CA and ITA upon degradation, both of which demonstrate cardioprotective effects on cardiac cells after ischemic injury, and that PICO patches generate a reduced inflammatory response upon implantation to the heart compared to other materials, signifying promise for use in cardiac patch applications.

Keywords: Polymer, Cardiac patch, Myocardial infarction, Ischemia reperfusion injury, Biomaterial

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Cardiac patches were generated from a novel material, PICO.

-

•

Citric acid and itaconic acid protect inured cardiac cells in vitro.

-

•

PICO patches degrade and release citric acid and itaconic acid.

-

•

PICO patches were implanted on the heart and compared to two controls, PEGDA and POMaC.

-

•

PICO patches resulted in a reduced inflammatory response and fibrotic reaction in vivo.

1. Introduction

Cardiac ischemic injury occurs as a result of obstruction of blood flow, which inhibits the heart tissue from receiving enough oxygen, leading to death of myocardial tissue. Establishing timely reperfusion of the occluded region is the only way to mitigate damage to the myocardium; however, injury specific to the reperfusion process also ensues [1], with oxidative and microcirculatory stress, inflammation, and apoptosis involved [2]. In response to the damaged myocardial region, maladaptive remodelling of the ventricle occurs. Ventricular wall thinning and scar tissue formation leads to increased ventricular wall stress and volume, and decreased contraction force and ejection fraction [3], posing significant challenges to heart function. Post-infarction reduced left ventricular ejection fraction is, indeed, one of the main causes of chronic heart failure globally [4]. While medication can be used to manage the reduced cardiac function by reducing oxygen demand in the heart or strengthening heart muscle contraction [5], there is no currently implemented strategy to recover or regenerate the damaged myocardium.

The use of cardiac patches implanted on the heart is one approach aimed at supporting the myocardium following damage from cardiac ischemic injury from myocardial infarction (MI) and/or ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI), with recent examples including an acellular gel-point adhesive viscoelastic patch made from starch hydrogel [6], acellular and cardiomyocyte (CM)-seeded injectable, electrically conductive scaffolds made from methacrylated elastic and gelatin with carbon nanotubes [7], and an induced pluripotent stem cell-derived engineered human myocardium for implantation currently under investigation in a clinical trial [8]. The mechanisms of cardiac patch functioning can fall into one or both of two main categories: supportive or regenerative. The supportive approach involves physically supporting the ventricle using a material patch that prevents some of the negative remodelling by limiting myocardial wall stress and thus ventricular dilation [6,9]. The regenerative approach incorporates bioactive factors, cells, or tissue via a biomaterial scaffold for delivery to the to the damaged region [9,10]. In either approach, an appropriate biomaterial that modulates host response to attenuate fibrosis as a result of the implant itself is required.

The epicardium, the outer layer of the heart comprised of a layer of epicardial cells, serves as the preferred location for cardiac patch application. Patches cannot be applied within the dense myocardial layer and application on the endocardial layer is associated with risk of embolization and thrombosis. While placement on the epicardial surface is a feasible route, patch integration with the myocardium and electrophysiological coupling between graft and host remains an issue that could be further aggravated through implantation of inappropriate materials. Therefore, achieving sufficient integration with the host and attenuating the implant-associated fibrosis remain key design criteria for cardiac patch technology. As such, the patch should either be inert (i.e., minimize the immune response to the implanted material), or activate a favourable immune response to facilitate patch integration. Recruitment of macrophages, the main cells involved in biomaterial-mediated fibrosis, is an important metric of host response, with macrophage polarization as pro-inflammatory (M1) or non-inflammatory (M2) playing a role [11]. The chronic inflammatory response to biomaterials involves granulation tissue formation wherein fibroblast infiltration and neovascularization occurs, as well as eventual foreign body giant cell (FBGC) and fibrous capsule formation [12]. Macrophages oversee this foreign body response to biomaterials, and it is currently understood that both M1 and M2 macrophages are implicated in this process, either together or by hybrid M1-M2 phenotype macrophages [13]. Macrophages initially phagocytize foreign materials and debris, remodel the provisional matrix, and secrete signaling molecules to recruit support cells such as fibroblasts (FBs) [13]. Macrophage fusion into FBGCs can also occur to degrade the implant, or, in conjunction with FBs, to deposit collagen layers to form a fibrotic capsule to wall off the material, even rendering it non-functional [13]. Prevention of this frustrated immune response, with the patch being walled-off by a fibrous capsule, is vital for adequate patch integration. Furthermore, given the patch application to the epicardial surface, activation of the epicardium to undertake epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition should be controlled such that fibrosis resulting from extensive activation is minimized.

Cardiac patch materials should meet several additional design criteria to satisfy their specific purpose. The patch should possess suitable degradation properties, meaning the material should remain intact long enough to provide structural support during the remodelling process, and yet it should degrade over time as the material and any incorporated cells integrate. Therefore, the patch would ideally remain for a minimum of 6 weeks after MI during which most of the pathological remodelling occurs, and any subsequent changes are minimal thereafter [14,15]. Immune rejection of cardiac patches is a concern [10], and biodegradation is therefore important once the desired treatment has been achieved. Therefore, it is also important to consider the degradation products and their effects, with degradation products ideally contributing to a favourable outcome in terms of patch integration, or inflammatory and regenerative responses. For use in the regenerative approach, support of cells in culture is important, and the patch should incorporate chemical, topographical, and material properties that provide a favourable environment for cells and tissue prior to implantation. Finally, tuning of the material mechanical properties such that the patch supports the heart and does not constrain beating motion, including relaxation, is required [6].

Synthetic, elastic biomaterials are a category of materials that are useful in cardiac patch technology because they can be chemically and mechanically tailored to meet the desired properties. Citric acid (CA), a tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) intermediate, has been used as a nontoxic and multifunctional monomer of citrate-based polymers that are formed through polycondensation reactions with diols, generating biocompatible polyesters that possess elastic properties and that can degrade via hydrolysis [16]. Poly (octamethylene (anhydride) citrate) (POMaC) is one example of such a polymer shown to have great utility for a wide range of applications, including as a cardiac patch material [17,18]. Building off this work, we developed a novel polymer, poly (itaconate-co-citrate-co-octanediol) (PICO), which possesses several key properties and capabilities including mechanical tunability, ultraviolet (UV) crosslinkability, compatibility with microfabrication techniques, and biocompatibility [19]. Its use has been demonstrated for applications including 3D printed shape mimicry and vascularized tubule structures [20], aligned cardiac cell sheets for cardiac ventricle formation [21], and as a cardiac patch scaffold [19]. In terms of meeting cardiac patch design criteria, we have shown that PICO materials can be mechanically tuned to match the requirements of cardiac tissue [21], and that it can support the culture of cardiac tissue [19]. Therefore, the two design criteria we focused on assessing in this work are the PICO patch's host in the cardiac setting, and its degradability and degradation products.

Besides citrate being one component of the polymer, another key novelty in PICO polymer is its inclusion of the molecule itaconate (ITA) into the backbone of the material. ITA is produced in stimulated macrophages from citrate in the TCA by the mitochondria-associated enzyme aconitase decarboxylase, which is encoded by immune responsive gene 1 (Irg1), and it plays a significant role in inflammatory processes [22]. The development of other polyester materials that incorporate ITA has been undertaken with tunable degradation [23] and immune modulation [24] capabilities demonstrated. Both CA and ITA as TCA cycle metabolites are of interest for their role in cardiac ischemic injury. CA has been found to have cardioprotective effects in cardiac IRI both in vivo and in vitro [[25], [26], [27]]. ITA has also recently been considered of interest as it relates to treatment of IRI. For example, a membrane-permeable non-ionic form of itaconate, dimethyl itaconate (DMI), was shown to reduce myocardial infarct size and attenuate hypoxia-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and cell death in CMs [22]. Given this relevance, we sought to investigate our novel CA- and ITA-based biomaterial in the cardiac context.

In this work, we investigated the role of CA and ITA in treatment of cardiac cells during an in vitro process mimicking IRI (Fig. 1). Using CA and ITA as building blocks, we synthesized and characterized PICO polymer, and demonstrated its use in the biofabrication of a polymer patch material. Degradation of the patch in accelerated and hydrolytic conditions was assessed, and the release of CA and ITA was observed over time. PICO patches implanted into the cardiac setting were assessed for their interaction with the epicardial surface, elicitation of an immune response, and resulting neovascularization within the implant tissue and underlying cardiac tissue regions. Comparisons made to other implanted cardiac patch materials, POMaC and poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), revealed that PICO patches elicited a lower immune response. We envision this patch as having potential as a material that can assist in the injured cardiac setting via its favourable host response and release of cardioprotective degradation products.

Fig. 1.

Overall schematic of study indicating assessment of molecules of interest, PICO patch synthesis and characterization, and in vivo patch implantation.

2. Methods

2.1. CM CA ITA IRI experiment

CMs were differentiated from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC) line BJ1D reprogrammed from neonatal, male, foreskin fibroblasts (a gift from Dr. William Stanford) [28] according to established monolayer differentiation protocols [29,30]. CMs were finally dissociated into single cells using established methods [30], on days 18–20 of stem cell differentiation. BJ1D CMs were seeded in monolayers in a 96-well plate (50,000 cells per well) and cultured for two weeks in Induction 3 Medium (I3M) (supplemented Stempro34 media containing 1 % penicillin/streptomycin, 213 μg/mL 2-phospahte ascorbic acid, 150 μg/mL transferrin, 20 mM HEPES and 1 % GlutaMAX), with media changes every 2–3 days. Cells were imaged, and subsequently exposed to culture conditions that mimic ischemia-reperfusion injury according to previous reports [31], which included a 6-h period of hypoxia (95 % N2, 5 % CO2) with ischemic media (119 mM NaCl, 12 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 0.5 MgCl, 0.9 CaCl2, 20 mM sodium lactate, and 5 mM HEPES, pH = 6.4), followed by a 3-h period of reperfusion in normoxia and supplemented reperfusion media. Reperfusion media (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1.4 mM calcium chloride and 2 % B27 without antioxidants) was supplemented with CA and ITA at concentrations of 10 μM (termed low concentration) and 10 mM (termed high concentration), and the pH of the media was adjusted to 7.4 for all groups. The control group used standard reperfusion media, with pH adjusted to 7.4 and a positive control of 100 μM H2O2 in reperfusion media was used. Each group included five to seven wells of CMs, and the entire experiment was conducted twice, with each data point representing a separate well.

Cell culture supernatant from one experimental set was analyzed for LDH release using an LDH assay (Cayman Chemicals) according to manufacturer's instructions. Calibration curves were established with known number of CMs incubated in 1 % TritonX in the corresponding ischemic and reperfusion media to convert absorbance into cell number.

In a supplemental experiment, 2 μM of CA and ITA were used and observation of cell function was continued up to 7 days after reperfusion. As such, after the 3-h period of reperfusion, cells were switched to standard culture media (I3M), which was also supplemented with the molecules of interest. Supplemented media was changed every two days. Beating assessments were performed before IRI, immediately after ischemia, immediately after reperfusion, and 12 h, 2 days, 4 days and 7 days after reperfusion.

2.2. Polymer synthesis and characterization

PICO gel was synthesized according to previous reports [19]. Briefly, a two-step one-pot polycondensation reaction was performed wherein 15.0 g 1,8-octanediol (OD), 16.190 g tricarboxylate triethyl citrate (TEC), 0.831 g stannous octanoate (1 % mol/mol ester bond), and 0.0954 g 4-methoxyphenol (0.5 wt% of all reactants) were combined in a round bottom flask assembled to a water condenser and collection flask. The flask was heated to 120 °C for 2 h under nitrogen purge and stirring at 200 rpm. 6.970 g dimethyl itaconate (DMI) was added after 2 h for further reaction. A molar ratio of acid (TEC + DMI) to alcohol (OD) of 1:1 was achieved. The crude polymer gel was purified through precipitation in ice cold methanol, followed by decanting and drying for at least 48 h prior to use.

Purified polymer gels were dissolved in CDCl3 and analyzed by 1H NMR with a 700 MHz spectrometer (Agilent DD2 NMR Spectrometer). Spectra were generated using MestReNova software.

2.3. Biofabrication of patches

Patch molds were generated as previous described [21]. Briefly, photo- and soft lithography were used to generate a microgrooved mold. A negative mold was fabricated with PDMS elastomer and curing agent (10:1 ratio), followed by degassing and curing at 75 °C for 45 min. The PDMS molds were removed and placed on glass slides, forming a closed system through with PICO could be perfused. Purified PICO gel was mixed with 1 wt% Irgacure 2959 photoinitator at 60 °C with stirring, and the gel was subsequently added to the inlet of the PDMS mold. Perfusion was allowed overnight by placing the mold at a slight incline. Once the polymer had perfused through the whole mold, the system was exposed to 4000 mJ/cm2 of UV light at 365 nm (UVP Crosslinker CL-1000 L, Analytik Jena). Crosslinked PICO patches were then carefully removed from the glass slide using a razor blade and soaked in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) overnight. Following this, the PICO patches were cut to a consistent 1 cm by 1 cm shape and soaked in 70 % ethanol overnight.

PEGDA and POMaC scaffolds were prepared in previous work [17]. Briefly, POMaC was synthesized from 1,8-octanediol, maleic anhydride, and citric acid in a 5:4:1 M ratio at 140 °C for 3 h, followed by purification by dissolving in 1,4-dioxane and dropwise precipitation in water. For POMaC scaffolds, 5 % (w/w) Irgacure 2959 and 60 % (w/w) poly (ethylene glycol) dimethyl ether (Mw 500) were mixed with the POMaC prepolymer, and the mixture was perfused into the custom-designed PDMS mold, followed by UV crosslinking. PEGDA scaffolds were prepared by dissolving 30 % (w/w) PEDGA (Mn 6000 g/mol) in PBS, adding 5 % (w/w) Irgacure 2959, and then preparing patches in the same procedure as the POMaC scaffolds. POMaC and PEGDA scaffolds were soaked in PBS, followed by 70 % ethanol, and then additional washes in PBS.

2.4. Patch degradation

PICO patches were made as described above. After crosslinking, the patches were fully submerged and washed for 24 h in PBS, followed by another 24-h wash in 70 % ethanol. The patch was dabbed with a cellulose-fiber wipe to remove excess liquid after washing and the mass of the patch was measured. Each patch was placed in 1 mL of the solution for the selected timepoints for both accelerated and hydrolytic degradation assays. A total four patch replicates were used for each time point. Patches were placed in an incubated shaker at 100 rpm and 37 °C for the duration of the experiment. At each time point, the patches were removed from the solution, dabbed dry, and the mass of the patch was measured. Supernatant solutions were collected and sent for mass spectrometry (Thermo Q-Exactive, Biozone, University of Toronto) to analyze for concentrations of CA and ITA. For accelerated degradation, a solution of 2 M NaOH was used, and in hydrolytic conditions, a solution of 1× PBS was used. Standard curves were generated at the time of analysis for both ITA and CA in 2 M NaOH and PBS respectively. Two samples were discarded from day 7 accelerated condition due to inconsistency in experimental condition.

In a supplemental degradation experiment, PICO patches were placed in 1 mL PBS in the presence of lipase (from Thermomyces lanuginosus) at a concentration of 5000 U/g-polymer at 100 rpm and 37 °C. Patch mass was compared before submersion and at 7 days and 14 days (with solution replaced at day 7). Degradation in PBS was performed at the same time.

2.5. Patch implantation surgery

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Toronto Ethics Committee and adult male and female Lewis rats (200–250 g, 8–9 weeks) were used. Animals were housed with a standard diet and water ad libitum during the whole experiment. Rats were anesthetized by inhalation of 3 % isoflurane and given a dose of preoperative analgesia (burprenorphine, 1.2 mg/kg and meloxicam, 2 mg/kg). Animals underwent endotracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation. Chest cavity was accessed by left thoracotomy through the fifth intercostal space. Cardiac patch implantation was carried out in the epicardium layer after opening the pericardium, and patches were sutured to the epicardium using a 7-0 polypropylene suture (two suture points per patch). Patches were also coated with fibrin hydrogels in situ for certain groups. The fibrin hydrogel was synthesized according to previous reports [17] and applied by including one drop of fibrinogen followed by one drop of thrombin on the implanted patch region. Experimental groups included sham, PICO, and PICO + fibrin glue at both one week and six weeks. Following implantation, the chest was closed by suturing the intercostal space (with 4-0), muscular layer (with 5-0), and skin (with 4-0), Dexon (absorbable) suture and chest drainage was performed with about 8–10 cm H2O vacuum. Animals were then extubated when spontaneous respiration recovers. Rats were allowed to recover in a warmed and padded cage and post-operative subcutaneous injections of buprenorphine (sustained release, 1.2 mg/kg, first dose pre-op and second dose 48 h later) and meloxicam (2 mg/kg, once daily for 2–3 days) were administered. After one week or six weeks, animals were sacrificed for histological analysis. Right after, the chest cavity was opened by cutting the xifoides and ribs, hearts were perfused using cold PBS and subsequently 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) and hearts were harvested. Hearts were fixed in 4 % PFA for 24 h, moved to 70 % ethanol for 24 h, and then moved to PBS until processing for analysis. Hearts were subsequently paraffin embedded and sliced (5 μm slices).

As the act of opening the chest and manipulating the pericardium as well as suturing could cause enough inflammation to drive some physiological changes, we additionally used stringent sham animals. Out of 8 sham animals, 4 just had the chest opened and closed. Another four (4) animals had the chest open, suturing performed and patches placed on the pericardium, with no contact with the heart. Analysis of these two groups demonstrated no significant differences in scored inflammatory repsonse, and thus they were lumped into a single sham group. This enabled us to conclusively prove that the placement on the epicardium is what causes any changes on the surface of the heart as well as the myocardium and exclude passive manipulation of the pericardium as a potential source of the difference between the groups.

PEGDA and POMaC scaffolds were implanted into ∼250 g adult male Lewis rats in previous work [17], according to the same procedure and time points described above, followed by fixation.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry analysis

Paraffin embedding, sectioning and immunohistochemistry of heart tissues was performed at the pathology research program of the Toronto General Hospital and the SickKids Hospital (Toronto, ON) according to standard protocols. For PICO patches, paraffin embedded slides were sent for immunohistochemical staining for Masson's trichrome, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), CD31 (Novus Biologicals, NB100-2284 1/300), alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Abcam, ab5694, 1/1000), CD68 (Serotec/BioRad, MCA341 R, clone# ED1, 1/100), and CD206 (Abcam, ab6493, 1/2000). Colour was developed using DAB (DAKO Cat# K3468) and counterstained with Mayer's Hematoxylin.

For PEGDA and POMaC patches, paraffin embedded slices were stained previously for Masson's trichrome, H&E, CD31 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-1506, 1/4000), SMA (Abcam, ab5694, 1/800) and CD68 (Serotec/BioRad, MCA341R, clone# ED1, 1/600) [17]. CD206 (Abcam, ab6493, 1/2000) staining was performed along with PICO patch samples.

All stained slides were imaged by selecting regions where the patch sections were visible and obtaining 4 images from each heart. Images were separated into two sections: implant tissue, which included the tissue surrounding the patch region, and cardiac tissue, which was comprised of a 200 μm wide strip of the myocardium under the implant tissue region (Supplemental Fig. 1). The area considered as implant tissue region for the sham groups was solely the surface layer of the heart (seen in Supplemental Figs. 2 and 3). The areas of the implant region were measured from Masson's trichrome slides, and the epicardial layer integrity was visually scored. Ratings were assigned based on the level of integration of the epicardial layer with the myocardium, which was assessed by observing the presence of light green collagen-stained regions integrating from the patch implant tissue region into the red, dense, myocardial muscle tissue. Scores of the epicardial layer were assigned from 0 (not visible), 1 (intact), 2 (slightly mixed with epicardium), 3 (mixed with epicardium) to 4 (cannot be defined).

CD68 and CD206 quantification was performed in Fiji by measuring the area of each region and quantification of the stained regions was performed by applying colour deconvolution with the H DAB vector, selecting colour 2 (DAB) image, and thresholding with the Max Entropy auto threshold to determine the stained area (Supplemental Figs. 2 and 3). In few cases (mostly sham), the automatic thresholding was not representative of the area stained, and thresholding was performed manually to match. CD31 and SMA quantification was performed by counting the number of positively stained vessels (large and small) in each region.

2.7. Immune response scoring

Masson's trichome and H&E-stained histological sections were reviewed by a pathologist blinded to treatment condition and used to evaluate foreign body giant cell reaction, fibrous capsule, epicardial fibrous reaction, and other inflammatory cell burden (mononuclear cell inflammation and/or mixed inflammatory cell infiltrates). These histological parameters were assessed using a semi-quantitative scoring system from 0 to 3+.

2.8. Statistics

Statistical tests were performed using Graphpad Prism software (Prism 9). Sample numbers are included by individual points on the graph and statistical tests are reported in the figure captions. P values are indicated by stars or hashtags on graphs (increasing symbols corresponding to p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, p < 0.0001 respectively). For semi-quantitative scoring data, non-parametric tests were applied (see Fig. 1).

3. Results

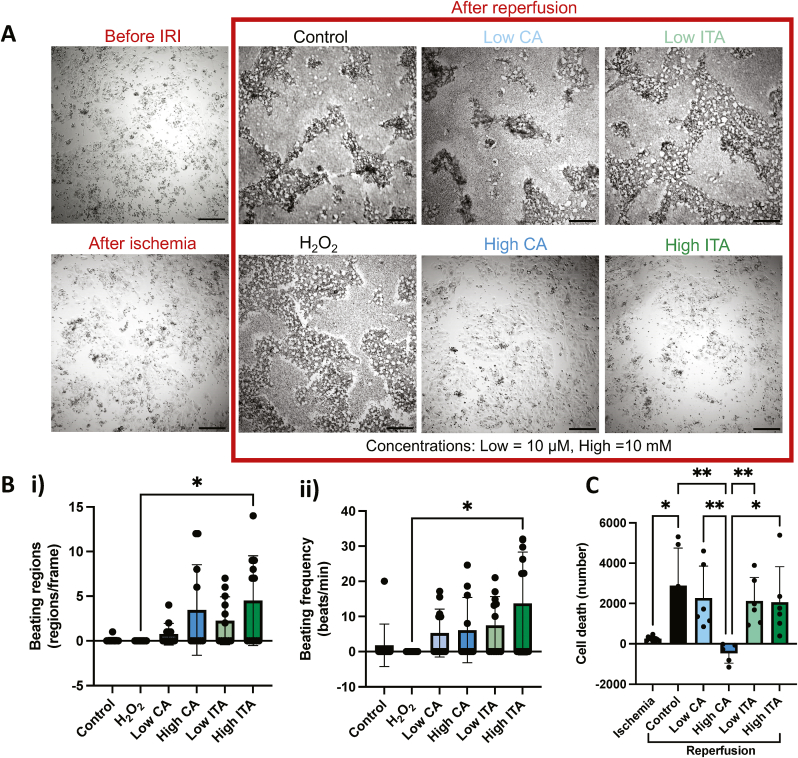

We investigated the effects that CA and ITA have in the injured cardiac setting by exposing CMs that underwent a process mimicking ischemia to two concentrations of CA and ITA during a period mimicking reperfusion. Based on previous reports showing cardioprotective effects of CA and ITA on CMs at concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 2 mM [22,25], we selected two concentrations – one near the literature values at 10 mM, and the other significantly lower at 10 μM. These concentrations are referred to as high and low respectively. CM monolayers before IRI were observed to have controlled beating with an average beating frequency of 55.3 ± 28.9 beats per minute and an average beating regions per frame of 18.5 ± 2.9 (Supplemental Fig. 4). After a period of ischemia, CM layers appeared intact, but beating was reduced, with only 29.5 % of imaged wells containing beating cells. After reperfusion, significant visible changes were observed in all wells except those that were given high doses of either CA or ITA during reperfusion (Fig. 2A). Cells in the control (i.e., no treatment), low CA, low ITA, and positive control (i.e., H2O2) groups all displayed death of cells with distinct morphology, possessing cavities where CMs appeared to have detached (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

CA and ITA during reperfusion have protective effects on cardiomyocytes after IRI.A) Brightfield images of cardiomyocytes before IRI, after ischemia, and after reperfusion with treatment. Scale bar = 200 µm. B) Cardiomyocyte beating regions per standardized field of view after IRI (i) and beating frequency after IRI (ii) are shown (n= 11 or 12). Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test were applied. C) Cardiomyocyte cell death during ischemia and after reperfusion (n = 5 to 10). Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s Multiple comparisons test was applied.

Comparing the CM beating, almost no wells exhibited viable CM contraction in the control and positive control groups, whereas wells in the CM and ITA treated groups still had regions where cell beating was present. The high CA and high ITA groups had the highest beating region count, with high ITA groups being significantly higher than the positive control (Fig. 2Bi). The beating frequency was also measured, and the high ITA group demonstrated significantly higher beating frequency compared to the positive control (Fig. 2Bii). All CA and ITA treated groups had greater average beating frequency than the control or positive control with an average of 5.27 ± 6.83 and 6.11 ± 9.28 beats per minute in the low and high CA groups respectively, and 7.46 ± 8.19 and 13.69 ± 14.61 beats per minute in the low and high ITA groups respectively, compared to 1.82 ± 6.03 and 0 beats per minute in the control and positive control groups respectively. We observed that the cells that beat with higher initial frequency were more sensitive to ischemia (Supplemental Fig. 4), which may be a result of different maturity levels between the batches [32] and possible links between sensitivity to ischemia and maturity level [33] or slight differences in composition of cardiomyocyte sub-types between the batches (e.g. ventricular vs nodal cells). Even lower concentrations were assessed over longer periods of time as well, and while there are hints of improvement with the addition of the molecules of interest at early time points, the results indicate this may be the lower threshold in terms of concentration of the molecules of interest having a measurable impact on CM function as assessed by these methods (Supplemental Fig. 5).

Cell death was assessed by LDH release, and a small amount of cell death was quantified during ischemia, followed by a significant increase during reperfusion in the control group (Fig. 2C). The cell death measured in the low CA, low ITA, and high ITA groups during reperfusion was greater than during the ischemic period, but it was not found to be significantly higher than during ischemia. The high CA group demonstrated significantly lower cell death than all other groups. The positive control was not included since H2O2 interferes with LDH assay [34].

Synthesis of PICO pre-polymer based on CA and ITA was performed, with synthesis and degradation products of interest illustrated (Fig. 3A). Characterization by H1NMR revealed the expected peaks, consistent with the chemical structure (Fig. 3B). The solid, crosslinked polymer patches were fabricated by perfusing PICO pre-polymer mixed with 1 % (w/w) photoinitiator into microfabricated PDMS molds on glass slides and exposing to UV energy (Fig. 3C). Using a blade, removal of the patch from the glass could be performed and the result was intact patch films that could be manually manipulated and soaked in solution and imaged (Fig. 3D). Rectangular holes were incorporated within the patch to enhance mass transfer for improved integration, and groves were patterned on one side to drive cell alignment.

Fig. 3.

Fabrication and characterization of PICO patches. A) Chemical reaction of PICO polymer synthesis with select degradation products shown. B) NMR spectra of purified PICO polymer visous liquid. C) Schematic of PICO patch synthesis procedure. D) Prepared PICO patches are shown in a 12-well plate in PBS (i), with brightfield microscopy (ii), and scanning electron microscopy (iii).

Investigation of the degradation of the entire PICO patch, as well as the release of specific degradation products was performed in both accelerated basic conditions (2 M NaOH), and hydrolytic conditions (pH 7.4) (Fig. 4A). Patches had an initial average mass of 5.58 ± 0.94 mg. Under accelerated conditions, the percent of mass degraded reached 43 % over a two-week period, but it plateaued around 7 days, suggesting this is the maximum hydrolytic degradation (Fig. 4B, D). This is consistent with previous degradation of PICO polymers with relatively high ITA content, reaching mass loss plateaus between 26 and 44 % within 48 h under accelerated hydrolytic degradation conditions [19]. Under hydrolytic conditions, a linear degradation profile occurred over a period of two months, with 31 % of the mass degraded in this time (Fig. 4B, D). Enzymatic degradation in the presence of lipase results in patch degradation between those observed in the hydrolytic and accelerated conditions (Supplemental Fig. 6 and Supplemental Fig. 7). The quantified release of degradation products also provides useful information as to the ranges between which the molecules of interest could be released in an in vivo environment upon patch implantation. Thus, the release of two molecules of interest, CA and ITA, was measured over these time periods using mass spectroscopy. Under accelerated conditions, 897 μg CA and 78 μg ITA, which corresponds to 16 % and 1.4 % of the initial patch mass respectively, was released (Fig. 4C and D). The molecules released into solution translate to concentrations of over 4.6 mM and 600 μM into release media respectively (Fig. 4 C, D). In hydrolytic conditions, masses of 0.40 μg CA and 0.27 μg ITA were released over an 8-week period, corresponding to roughly 2 μM concentration of each into solution (Fig. 4C, D).

Fig. 4.

PICO patches release CA and ITA under accelerated and physiological conditions. A) Schematic of PICO patch degradation assessment under accelerated and physiological conditions. B) Degraded PICO patch mass under accelerated conditions in NaOH (n=4) (i) and in physiological conditions in PBS (n=4) (ii). C) CA and ITA release from PICO patches under accelerated conditions (i, ii) and physiological conditions (iii,iv). Data are presented as mass of the molecule release (i, iii) and concentration released into solution (ii, iv). Stars indicate statistical significance between CA and ITA at each time point by unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney test if Shapiro-wilk test for normality of residuals not passed (n=4, n=2 for day 7 accelerated).

To begin to establish PICO's relevance in the in vivo cardiac setting, PICO patches were implanted onto healthy rat hearts. We investigated several factors relating to the implant tissue size, interaction with the epicardial surface, angiogenesis, macrophage infiltration, and host immune response. Healthy hearts were selected to evaluate the host response under baseline conditions, without the confounding factors of tissue fibrosis that results from the infarct itself. To gauge these responses relative to other patch options, we compared to our previous patch implantation using a specially designed injectable POMaC patch and a PEGDA control material, both of which are known to be biocompatible materials [17]. All patches were implanted using the same preparation and implantation approach and were affixed with sutures and fibrin glue.

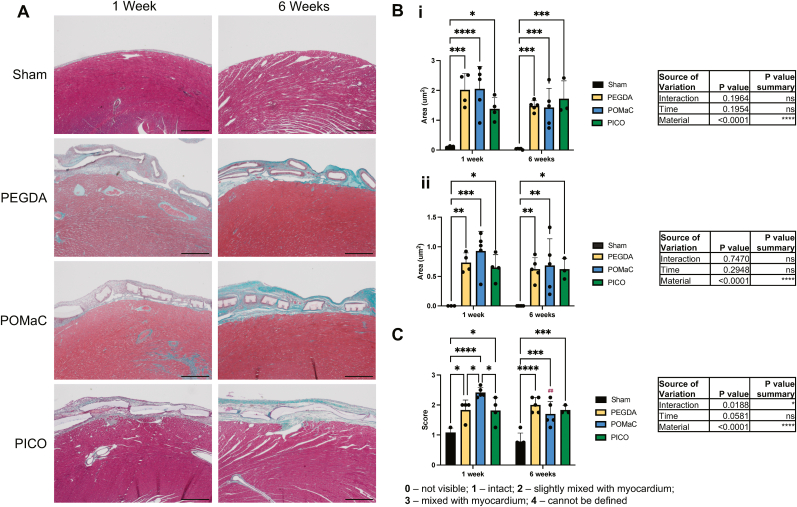

The gross morphology of the patch implantations was assessed using Masson's trichrome stained tissue slides (Fig. 5A). The area of tissue formed around the patch, termed implant tissue here, was assessed at both one-week and six-week time points after implantation. All patch types had increased total implant tissue areas (Fig. 5Bi) and implant tissue under the patch (Fig. 5Bii) compared to shams, but no differences were observed between patch types at either time point. The epicardial layer integrity was visually scored, with ratings correlating to the level of patch integration with the myocardium, visible by the presence of blue collagen-stained regions integrating from the patch implant tissue region into the red, dense, myocardial muscle tissue (Fig. 5C). All patch types had significantly less defined epicardium and more integration with the myocardium compared to controls, and at the one-week time point, POMaC had significantly higher levels than the other two patch types.

Fig. 5.

PICO patches implanted on the epicardial surface have similar implant area and epicardial integrity to PEGDA and POMaC patches. A) Masson’s trichrome images of patches on the heart at one week and six weeks after implantation. Scale bar = 500 µm. B) The total area of the implant tissue region including the patch (i) and the area of the implant tissue region below the patch (but above the myocardium) (ii) were quantified. C) Epicardial integrity score was assigned. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was applied (n = 3 to 5). Hashtags above the six-week data indicates significant difference from one week by Šidàk’s multiple comparison test.

Comparisons were also drawn between PICO patches applied with and without fibrin glue, in order to assess the contributions of the patch independently from the fixative (Supplemental Fig. 8). No differences in implant tissue area were observed between these two groups, and the epicardial integrity was reduced (i.e., higher score of integration) in the group without fibrin glue at one week.

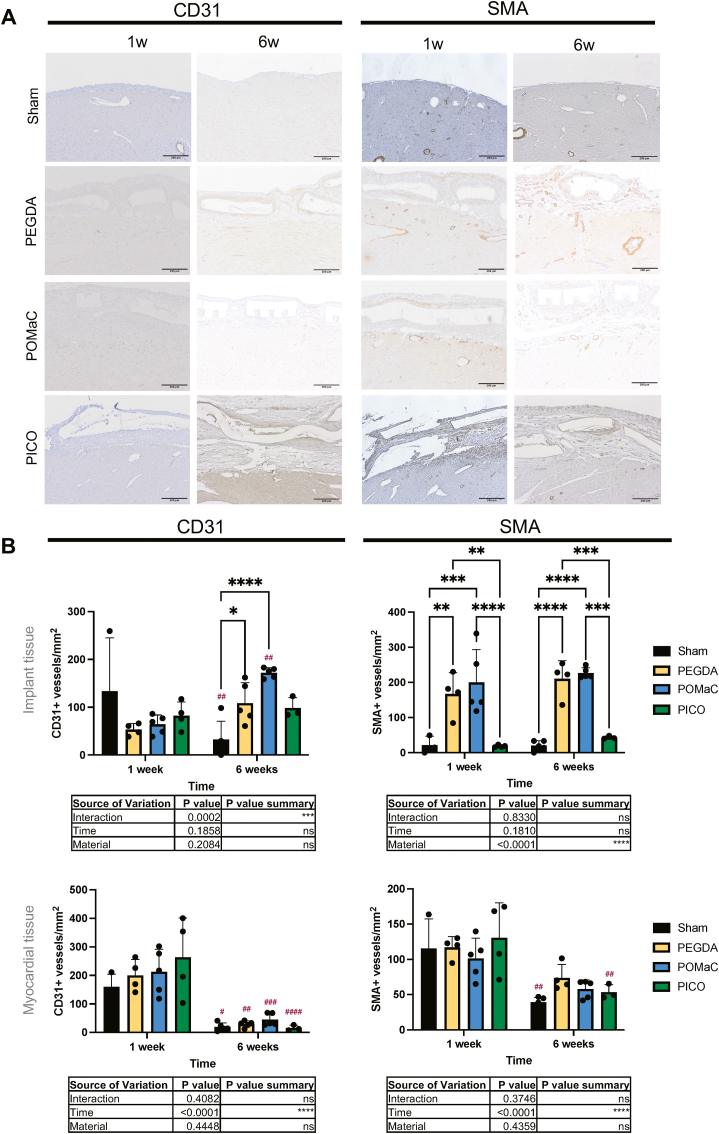

We assessed the angiogenic response to the PICO patches and again compared them to POMaC and PEGDA patches. CD31, a marker of endothelial cells, indicating the presence of vasculature, was compared in the implant tissue and the myocardial tissue (Fig. 6A). Little difference was observed between patch types in the myocardial tissue (Fig. 6B). In the implant tissue, similar CD31+ vessels per area was observed at one week, but both PEGDA and POMaC patches resulted in a higher presence of CD31+ compared to shams at six weeks. However, no significant difference in CD31+ was observed as a function of material variation at both time points. Comparisons of SMA + vessels, also indicating the presence of vasculature (Fig. 6A), revealed that no difference occurred in the myocardial tissue beneath a patch, but higher SMA + vessel density was observed in the PEGDA and POMaC patch samples in the implant region at both one week and six weeks compared to PICO (Fig. 6B). In terms of the role of fibrin glue, the only difference is observed in the implant tissue at six weeks, with PICO alone having a higher SMA + vessel density compared to PICO patch applied with fibrin (Supplemental Fig. 9).

Fig. 6.

Angiogenic response is lower with PICO patches around implant and comparable in the myocardial tissue across different types of materials. A) Immunohistochemistry slides stained for CD31 and SMA at one-week and six-week times points. Scale bar = 200 µm. B) Quantification of vessel density in the implant tissue (top row) and myocardial tissue (bottom row) regions (n = 3 to 5). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was applied and comparisons between groups are shown on graphs. Hashtags above the six-week data indicates significant difference from one week by Šidàk’s multiple comparison test.

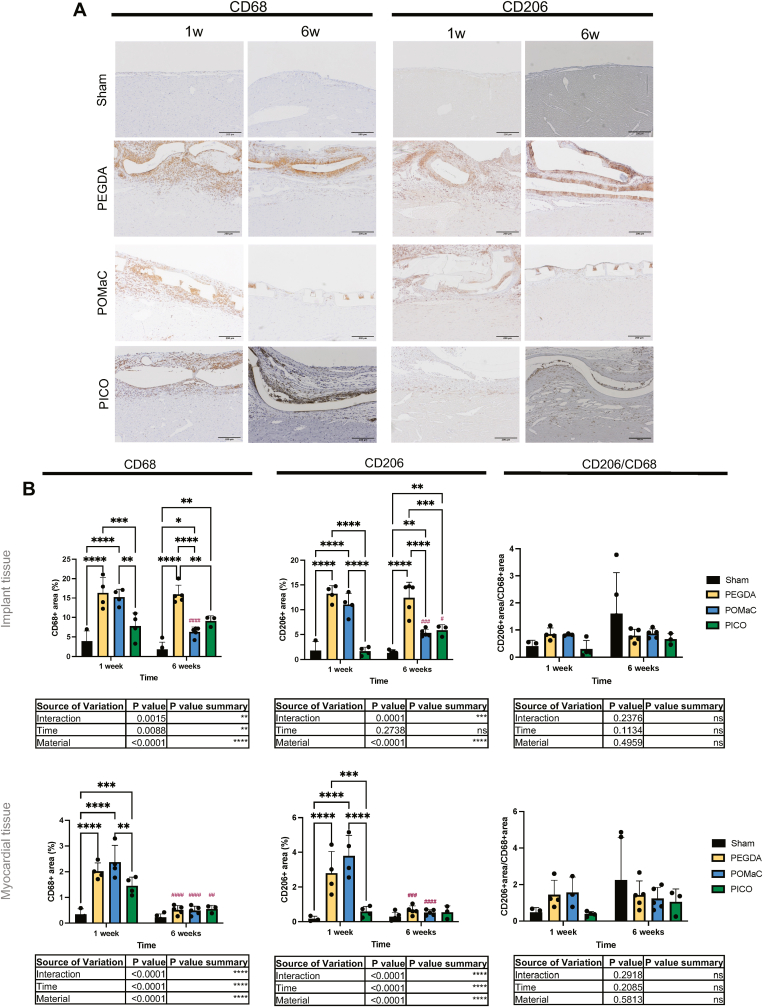

The immune response to patch implementation on the heart surface was assessed with immunohistochemical analysis of macrophage infiltration (Fig. 7A). Presence of CD68, a marker for all macrophages, and CD206, commonly a phenotypic marker of M2 polarized macrophages [[35], [36], [37]], was quantified in both the implant tissue and cardiac tissue regions. In general, greater presence of macrophages was observed in the implant tissue area compared to the underlying myocardial tissue space. At the one-week time point, CD68+ coverage of the implant tissue area was highest in PEGDA and POMaC patch samples, with a reduced CD68+ presence in the PICO patch samples (Fig. 7B). A significant reduction in CD68+ coverage occurred over time in the POMaC patch group, while the PEGDA patch group remained high, and the PICO patch group remained low (Fig. 7B). In the myocardial tissue section beneath the patch implant, the PICO patch group had again the lowest CD68+ coverage, and all groups demonstrated a significant decrease over time (Fig. 7B). In terms of CD206+ macrophage infiltration to the regions, a similar trend to those observed in the CD68+ results occurred. In the implant tissue, PICO patches had significantly lower CD206+ presence compared to the other patch materials at one week, and both PICO and POMaC had significantly lower CD206+ coverage than PEGDA at six weeks. Notably, while CD206+ coverage remained the same in the PEGDA group, and decreased over time in the POMaC group, CD206+ coverage significantly increased in the PICO group (Fig. 7B). In the myocardial tissue, PICO had significantly lower CD206+ coverage at one week, which also remained low over time, while a reduction occurred for the other two patch types at six weeks (Fig. 7B). Overall, there were no significant differences in the ratios of CD206+ area to CD68+ area at any time point across patch types. We also compared PICO patches applied alone and in conjugation with fibrin glue, and a significant difference between these two groups existed in CD68+ coverage in myocardial tissue at the early time point where fibrin containing patches exhibited attenuated CD68+ cell presence (Supplemental Fig. 10). The ratio of pro-regenerative CD206+ to total CD68+ macrophages increased with time with PICO alone, but not when fibrin was included (Supplemental Fig. 10).

Fig. 7.

PICO significantly attenuates total macrophage infiltration in both implant and myocardial tissue after cardiac patch implantation. A) Immunohistochemistry slides stained for CD68 and CD206 at one-week and six-week times points. Scale bar = 200 µm. B) Quantification of CD68, CD206, and CD206 over CD68 ratio in the implant tissue (top row) and cardiac tissue (bottom row) regions (n = 3 to 5). Two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test was applied and comparisons between groups are shown on graphs. Hashtags above the six-week data indicates significant difference from one week by Šidàk’s multiple comparison test.

The response in vivo to the patches was also assessed by a pathologist, with scores of several immune reactions assigned in a blinded manner based on Masson's trichrome (Fig. 5A) and H&E stained sections (Fig. 8A). FBGC reaction was greatest in the PEGDA patch group, with POMaC and PICO patches both having lower reactions at the one-week and six-week time points (Fig. 8B). The fibrous capsule formation around the samples was measured to be similar at one week, but at six weeks, PICO was the only group without a significantly higher score compared to the sham. The scores associated with other inflammatory burden revealed that all materials performed similarly, but with POMaC having a significantly increased response compared to sham. The inflammatory burden dissipated over time across materials. Finally, the epicardial fibrous reaction in all materials was similar at one week; however, PICO was the only material to not have a significant increase compared to sham. The epicardial fibrous reaction significantly reduced over time for PEDGA and POMaC, but at six weeks, PEGDA maintained the highest epicardial fibrous reaction. With respect to the role of fibrin glue, it appears that fibrin glue causes negligible difference in pathological responses compared to PICO patches without fibrin glue (Supplemental Fig. 11).

Fig. 8.

PICO patches attenuate fibrotic host response. A) H&E images of patches on the heart at one week and six weeks after implantation. Scale bar = 500 µm. B) Inflammatory response scores corresponding to FBGC reaction, fibrous capsule, other inflammatory burden, and epicardial fibrous reaction (n = 3 to 5). Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test was applied at each time point and comparisons between groups are shown on graphs and in tables. Hashtags above the six-week data indicates significant difference from one week, evaluated by Mann-Whitney test.

4. Discussion

Cardiac biomaterial patches applied to the epicardial surface with the goal of supporting the weakened ventricle after an ischemic event are in development. We postulate that an ideal candidate is a biodegradable elastomeric material that attenuates a fibrotic response, while at the same time releasing cardioprotective small molecules. Our focus here was on the design of materials that can contribute to the improved integration with the host by reducing the frustrated immune response and thus limiting the patch separation from the tissues by FBGCs and fibrous capsule, as well as achieving patch degradation into favourable molecular components that can provide benefit to the injured heart. Given the molecular composition of the novel material we developed, PICO, and the cardioprotective and immunomodulatory benefits of its components, ITA and CA, our investigations focused on these two aspects of the biomaterial patch interacting with the cardiac environment.

ITA and CA at 10 μM and 10 mM concentrations provided a degree of protection for CMs during reperfusion following ischemic injury. Even low concentrations (10 μM) of CA and ITA improved the appearance of cells and preserved beating activity in some wells. These in vitro findings are in line with previous reports that found a protective role of CA and ITA in cardiac ischemic injury. One in vitro study demonstrated that CA can ameliorate the impacts of IRI on CMs with concentrations of 200 μg/mL and 400 μg/mL (equivalent to roughly 1 and 2 mM respectively) shown to reduce LDH release, reduce apoptotic cell number, downregulate caspase-3, and upregulate phosphorylated Akt expression in CMs [25]. Another study demonstrated that CA at 0.5 and 1 mol/L had cardioprotective effects against hypoxia-reperfusion in CMs in vitro with decreased apoptosis and autophagy [27]. In vivo, pre-treatments with concentrations of 250 and 500 mg/kg of CA significantly reduced myocardial infarct size after IRI, and reduced TNF-α levels and platelet aggregation [25]. Another study in rats showed that pre-treatment of citrate via intravenous injections in the tail in concentrations of 25–100 mM resulted in reduced ventricular arrythmia, reduced serum calcium ion concentration, reduced caspase-3 expression, and reduced infarct area [26]. ITA and its derivatives, e.g. DMI, have also been shown to have potential impact in terms of cardioprotective effects during IRI, with DMI (4 mg/kg/min) delivered during ischemia in a mouse IRI model via intravenous infusion showing a reduction in myocardial infarct size. Follow up in vitro analyses demonstrated that neonatal CMs pretreated with DMI had attenuated hypoxia-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and reduced hypoxia-induced cell death at 0.25 mM and 1 mM concentrations [22].

Myocardial ischemic injury occurs as a result of a sequence of metabolic and structural cellular changes including modifications in ionic transport systems (e.g., increase in cytosolic Ca2+), increased permeability of the phospholipid bilayer, and physical disruption of the cell membrane [38]. With a lack of oxygen, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation stops and anaerobic glycolysis increases. The reduction in oxygen as an electron acceptor as well as the reduction in tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates limit mitochondrial metabolism, and one consequence is an increase in TCA cycle intermediate succinate [39]. With the addition of a reperfusion stage, additional mechanisms take place. As oxygen is reintroduced, mitochondrial metabolic changes cause a collapse in the membrane potential, Ca2+ overloading, disruption of cell membranes, and eventually cell necrosis [39]. Cardiac ROS production, controlled by various metabolic processes and oxygen levels, is also increased [39]. While the mechanisms of effect of CA and ITA in this context are not yet fully elucidated, CA is known to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [40], and can combine with free Ca2+, forming soluble complex-calcium citrate [27], signifying possible routes of action. Indeed, the chelation of calcium has been identified as a possible mechanism involved in the protective effects of CA [26]. ITA's mechanism of action should also be further investigated, but a possible pathway involves the ability of ITA to inhibit succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) [22]. The accumulation of succinate that occurs during ischemia causes mitochondrial ROS production during reperfusion via reoxidation by SDH, and it has been demonstrated that the inhibition of SDH can reduce mROS and IR injury [41].

Using our PICO polymer synthesized with CA, ITA, and 1,8-octanediol monomers, we fabricated a patch material. Building off previous work wherein this material was used for applications as a scaffold for cardiac tissue [19], perfusable tubule structures [20], and as a 3D cardiac ventricle construct [21], we developed a 1 cm by 1 cm biofabricated PICO patch. This patch material remained intact and stable in aqueous environments. We sought to investigate the degradation of PICO patches over time, and the release of valuable molecules of interest – CA and ITA. Looking first at the degradation and release in accelerated alkaline conditions, we observed that the total patch degradation plateaued after one week. Interestingly, the release of CA and ITA plateaued as quickly as one day. It appeared that in this alkaline environment, a limit of degradation is reached, suggesting that the hydrolytic degradation reaches a maximum. Polymer networks crosslinked via radial polymerization of vinyl groups are likely responsible for the material that remains intact. As such, the ITA and CA that are bonded through ester linkages would thus be able to be broken down hydrolytically, supporting the observation of free CA and ITA molecules released into solution reaching their maximum release at earliest time points. CA and ITA remaining in oligomers and crosslinked polymer chains would not be accessible for hydrolytic degradation and are thus not measured to continue to release past one day. Nevertheless, concentrations of CA and ITA of 4.6 mM and 0.6 mM were released into 1 mL solution over time, corresponding to the magnitude of the high concentrations to which we exposed injured CMs. Importantly, these physiologically relevant concentrations of CA and ITA were achieved through release of just 16 % CA and 1.4 % ITA from the lightweight patches with the initial mass of only 5 mg, demonstrating the feasibility of this approach for scaling up to larger animals.

In hydrolytic conditions at physiological pH, the greatest amount of total degradation occurred within one week, followed by a steady increase that reached 31 % total degradation over a two-month period. This patch degradation profile would lend itself well to a patch being used for regenerative strategies, wherein the patch is initially used to support cells for implantation and degrades over time as the delivered tissue integrates with the host and as the requirement for scaffold support decreases upon remodelling. The release of both CA and ITA in hydrolytic conditions follow similar release profiles, with steady, near zero-order release (R squared of 0.85 and 0.84 for linear regression of CA and ITA release curves respectively). Given that these concentrations are well below solubility limits of CA and ITA, and that we observe zero-order release in PBS, we do not expect there to be changes in amount released in different volumes of release solution. The concentrations of roughly 2 μM released into 1 mL solution over two months in hydrolytic conditions represent the lowest possible range of concentrations released in vivo due to additional degradative substances [42] and smaller surrounding solution volume in the in vivo cardiac setting. For example, macrophages secrete various enzymes such as lipoprotein lipase [42], and previous work demonstrates that a similar material composed of ITA and diol building blocks exhibited degradation rates (percent degradation over time in days) that were 42 times greater in lipase (5000 U/g polymer) compared to in PBS over a one month period [24]. Furthermore, with the patches placed on the epicardial surface of the rat heart, the release solution volume of the in vivo setting would correspond to something closer to the pericardial fluid volumes, which are measured at 0.5–0.9 mL/kg in catheter-instrumented rats (and therefore 0.25–0.35 mL/kg lower to account for catheter volume) [3]. For rats of 250 g, and assuming the larger end of the volume range (i.e., 0.65 mL/kg), the release solution volume would be 0.1625 mL. Assuming the smaller end of the volume range (i.e., 0.25 mL/kg), the release solution would be 0.0625 mL. Translating the 0.40 μg CA and 0.27 μg ITA released over 8 weeks from our in vitro experiment to these lower volumes, the concentrations could range anywhere from 12.8 μM to 33.3 μM. There would, however, be fluid clearance which would increase the total volume over time; but, the rate of pericardial fluid clearance is low compared to that of plasma [3]. Additionally, the release of degradation products would occur locally at one site of the heart, resulting in a higher concentration of CA and ITA on the injured tissue. Conversely, there are many degradative constituents that occur at the site of an implanted biomaterial in vivo that increase the degradation rate such as reactive oxygen species, proteolytic and hydrolytic enzymes, and phagocytic cells [4]. Therefore, while the 12.8–33.3 μM conversion is a simplification, it illustrates that the release concentrations of 2 μM presented from our in vitro experiments are in the conservative range. Nevertheless, this concentration is still in the same order of magnitude as the low concentrations to which we exposed injured CMs with resulting impact on function. Experimental results directly using 2 μM indicate that this represents the lower threshold for functional impact.

In both accelerated and hydrolytic conditions, a greater amount of CA was released compared to ITA. In the accelerated conditions, the difference between total mass or molar concentration of CA relative to ITA was much greater than in hydrolytic conditions. We hypothesize that ITA, possessing pendant vinyl groups, is more extensively involved in crosslinking polymer chains, thus releasing into solution as monomers to a lesser extent. This difference may not be extensively captured at the lower release rates exhibited in the hydrolytic setting, since most labile, least crosslinked molecules will be released first under hydrolytic conditions. The accelerated conditions will also degrade less labile sections. These less labile areas, because of greater crosslinking will lead to less chain mobility and access to water, and will be rich in CA, but poor in ITA that can be released, as the double bond will have reacted. As a result, the release of CA is expected to be more persistent and long term than ITA release. Nevertheless, the controlled release profile of CA and ITA over time in hydrolytic conditions is desirable, and the range of concentrations spanning three orders of magnitude from a minimum hydrolytic release to the theoretical maximum hydrolytic release in accelerated conditions are relevant concentrations for influencing injured CMs as shown by our previous experiment. Therefore, this material is promising for use in the cardiac patch setting and in alignment with our previous work [19], its chemical composition can be further tuned to optimize release properties.

As a first step to understand whether the PICO patches would succeed in a cardiac setting, they were implanted onto healthy rat hearts. Success in this setting is determined by several factors: remaining affixed to the heart surface, integration of the patch with the host tissue, limiting negative immune responses to the foreign biomaterial, and appropriate patch degradation. First, no differences were observed in the area of the implant region in the PICO patch group compared to POMaC and PEGDA patches.

In terms of angiogenesis into the patch implant area, PICO showed lower presence of blood vessels compared to the other materials. This trend did not, however, translate to the underlying myocardial tissue region below the patch, which is of even greater importance when it comes to vasculature formation given the metabolic demand of cardiac muscle. The lower angiogenic response to PICO in the implant region corresponds to a notably lower presence of macrophages observed in the PICO patch group compared to POMaC and PEGDA. Decrease in both CD31+ and SMA + vessels in the sham group between week 1 and 6 could be attributed in part by the small area of the surface of the heart in this group, which increases measurement error as well as the fact that the act of opening the chest and manipulating the pericardium could cause enough inflammation to transiently drive angiogenesis in the surround tissue, which resolves over long term as expected.

In the implant region, PEGDA and POMaC have higher levels of both macrophage markers at the early time point, and PEGDA maintained this significantly higher response compared to PICO over time. In the myocardial tissue region, in the acute time point, we again observed that PICO had the lowest macrophage infiltration (CD68+) and lowest CD206+ presence as well. These findings are important, as a high and persistent macrophage infiltration into implant materials may ultimately lead to chronic inflammation and implant fibrosis, that would undermine the functional effects of cardiac patches.

To further elucidate the inflammatory response, scoring of the host reactions to the biomaterial patches showed that the PICO patches did not have significantly higher scores of fibrotic host response compared to the sham, whereas both other materials did. A notable difference in FBGC reaction occurred between the patch materials, with PEGDA having a starkly higher reaction than POMaC and PICO. FBGCs are collection of biomaterial-fused macrophages that result as a typical reaction to the presence of foreign bodies such as implants [12]. The consistent trends in CD68 and FBGC reaction across the biomaterial patches is expected given that CD68 is stained in the cytoplasm of FBGCs [12]. In addition, fibrous capsule formation around patches at the six-week time point was lower with PICO patches compared to the other materials.

Taking the angiogenesis, macrophage, and inflammatory score results together, we can conclude that the materials that elicited a stronger immune response as measured by macrophage presence and host inflammatory metrics also demonstrated greater infiltration of SMA + vessels at both time points within the implant tissue. Given that factors secreted by macrophages promote angiogenesis, and both M1 and M2 macrophages contribute to the various stages of the vascularization processes [43], it aligns that we observe both greater macrophage presence and increased vasculature formation in the implant region for PEGDA and POMaC. Across several metrics including chronic macrophage presence and FBGC reaction, PICO patches caused a less aggressive immune response compared to both other evaluated patch materials. Given the nature of the inflammatory response, it is a “double-edged sword” in that it is a necessary response to a foreign material and can establish a regenerative microenvironment, but too much inflammation can also cause fibrosis, tissue degradation and destruction, and can thwart biomaterial integration. Therefore, even though we observe greater vessel infiltration with PEGDA and POMaC patches, the persistent inflammatory response that is observed with macrophage presence, FBGC reaction, and fibrous capsule formation are indicative of less biocompatible materials and frustrated inflammatory response compared to that of PICO.

Findings here also align with what is known about the time course of the inflammatory response. While the acute inflammatory response to biomaterials involving mast cells and neutrophils typically resolves in less than one week, the chronic inflammatory response follows, and is characterized by the presence of monocytes and lymphocytes, as well as macrophages and FBGCs at the biomaterial interface [12]. This chronic inflammation usually resolves within two weeks for biocompatible materials. After these two phases, granulation tissue is formed, noted with the presence of macrophages, fibroblast infiltration, and neovascularization. Finally, fibrous capsule formation can occur, with granulation tissue separating from the biomaterial by layers of monocytes, macrophages, and FBGCs [12]. We observed several important differences in the time-dependent nature of inflammatory response between the examined patch materials. First, all responses in the underlying myocardial region for all materials dissipate over time, which is expected due to the initial infiltration of cells to the region and subsequent resolution at a distance from the implanted biomaterial. Next, nearly all responses around the biomaterial implant remain high over time for the PEDGA patches, which elicited the greatest inflammatory response overall. POMaC patches exhibited resolution of some metrics (macrophage presence), while others increased at later time points (fibrous capsule formation). Importantly, when looking at the time course of the response to PICO, almost every metric remained low over time, with the exception of CD206, which increased over time.

The overall lower inflammatory response to PICO patches compared to PEGDA and POMaC patches may be understood as a result of the chemical composition of the material. Given ITA's role in attenuating inflammation through mechanisms such as SDH reduction in macrophages, ITA-based polymers have been shown to result in rapid resolution of biomaterial-associated inflammation in vivo [24]. Relating to the molecular component release from our PICO patches, the most conservative release of ITA and CA from PICO patches into 1 mL solution within six weeks is over 1 μM. The true in vivo degradation and release that occurs due to enzymatic or cell-mediated degradation would be significantly greater, likely between the ranges of the hydrolytic and accelerated release profiles as shown in experimental and theoretical results (i.e., up to a maximum of 74.7 mM CA and 9.6 mM ITA assuming minimal solution around the heart and ignoring fluid clearance) (Supplemental Fig. 6 and Supplemental Fig. 7). Indeed, as part of the foreign body response to biomaterials, macrophages and FBGCs can cause further degradation through the release of degradative enzymes, reactive oxygen intermediates, and acid at the biomaterial surface [12]. Furthermore, with patches placed in a localized region of the heart, and the solution surrounding the heart being much less than 1 mL [44], it is feasible that these released molecules of interest modulate the immune response, especially given the role of ITA as an anti-inflammatory metabolite [45].

ITA is involved in numerous mechanisms of immune modulation including SDH inhibition, electrophilic stress regulation, and modification of multiple proteins with roles in inflammation such as nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) and activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) [45]. Recent studies are beginning to elucidate ITA's role in promoting M2 macrophage polarization as well [45]. For example, a hydrogel loaded with ITA derivative, 4-octyl itaconate (OI), resulted in M2 macrophage polarization [46], and DMI-loaded PCL nanofibers polarized M1 macrophages into M2 macrophages [47]. Notably, our results show that the PICO patch was the only material that demonstrated an increase in the CD206 expression over time, which could correspond to M2 macrophage polarization upon release of ITA from the patches, which occurs to a much greater extent at 6 weeks compared to 1 week. However, another study indicated that itaconate and OI block M2 polarization [48], and it has also been shown that ITA, produced by pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophages, can be taken up by non-inflammatory (M2) macrophages, in which it reprograms glucose metabolism [49]. While more work needs to be done to fully understand ITA's role in macrophage polarization, there is potential that this molecule can influence the macrophage response upon release.

Citrate also plays a role in cellular immunity and antioxidant activity [50,51]. While its exact function in macrophage response or inflammation is not fully elucidated, as a TCA cycle intermediate, it does play a role [52]. For example, CA has been shown to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory role in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [53]. It is important to note that POMaC, while not comprised of ITA, does have CA as a monomeric component. PEGDA on the other hand, contains neither ITA nor CA monomers.

Finally, our comparisons of biofabricated PICO patches with and without fibrin glue revealed that there is little difference across most metrics. The group that used fibrin glue had more intact epicardial layer and lower CD68+ presence in the myocardial tissue at one week, and lower SMA + vessel density in the implant tissue at six weeks. These results suggest that fibrin may play a role in reducing patch integration. Perhaps protein adsorption is different with fibrin present or the interaction with the PICO material is slightly impeded when fibrin glue is used. However, these effects are minimal, and most metrics revealed a similar response between the patch with and without fibrin glue.

It should be stated that the comparisons drawn in this work are based on the patches as they have been fabricated. Slight differences in porosity would occur due to differing chemical composition between patches and the exact impact of patch geometry would have to be determined in future studies. The purpose of these comparisons was to benchmark host response to PICO, relative to our previously investigated biomaterial patches, and to determine whether further investigations should be continued with this material. This work has concluded that the PICO patch fabricated here is worth investigating further in the cardiac context given the attenuation of the foreign body response in vivo and its promising material composition. Further tuning of the material composition and degradation could be undertaken such that the inflammatory response is modulated to achieve an optimal response of both biocompatibility and promotion of regenerative processes. In addition, PICO patches should be considered an option for investigations in the injured cardiac in vivo setting using models of MI or IRI. Indeed, the envisioned application is a patch applied to the heart following MI. In line with recent strategies aimed to achieve cardioprotective effects for IRI including the injection of a nitric-oxide loaded hydrogel immediately after reperfusion [54], and an adenosine-loaded patch applied to the infarcted heart directly prior to reperfusion [55], a similar timeline of delivery of PICO patches could be attempted in future. In fact, with the proven ability to achieve delivery of polymer patches via injection [17], a possible concept for investigation to improve clinical outcomes of IRI could include the non-invasive delivery of cardiac patches, designed to release favourable cardioprotective molecules locally, at the point of clinical intervention during or immediately after reperfusion is performed. Indeed, a downside to explored antioxidant treatment for IRI has been that very high levels of oral treatment are needed to achieve the local concentrations that could have protective impacts on cardiac tissue [56], suggesting a possible role for more localized, sustained delivery. Therefore, in the future, dual mechanisms of support could be achieved via patches for MI or IRI wherein mechanical support to prevent negative remodelling and cardioprotective molecules could be simultaneously administered. Recent work using poly-e-caprolactone nanofibers loaded with DMI showed immune modulation and myocardial protection after MI [47], indicating the interest in this molecule for its immune modulatory and cardioprotective effects in the injured cardiac setting.

5. Conclusion

CA and ITA are of interest as molecular components of synthetic biomaterials. CA has been widely used in biomaterials, and specifically, as a monomer in biocompatible elastic polyesters. ITA is more recently under investigation and has begun to be incorporated into biomaterial systems due to its interesting immunomodulatory roles. We first demonstrated that CA and ITA favourably impact cardiac cells during IRI in vitro, preserving cell morphology and beating function. Using CA and ITA as building blocks, PICO polymer was synthesized, from which PICO patches were fabricated. Degradation assessments of the PICO patches demonstrate favourable degradation profiles over time as well as release of CA and ITA in physiologically relevant concentrations. PICO patches were then implanted onto the epicardial surface of rat hearts, and compared to other cardiac patch materials, POMaC and PEGDA. PICO elicited a significantly lower immune response, with less infiltration of macrophages, and lower FBGC reaction. SMA + vessel infiltration into the patch implant region was higher in the other materials compared to PICO, consistent with the greater immune cell infiltration. Overall, this work demonstrates that biofabricated PICO patch materials, and their molecular components released upon degradation, show promise for use in cardiac patch applications for treatment of myocardial ischemic injury and produce a less severe inflammatory response upon implantation to the heart.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dawn Bannerman: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Simon Pascual-Gil: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Scott Campbell: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Richard Jiang: Formal analysis, Investigation. Qinghua Wu: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Sargol Okhovatian: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Karl T. Wagner: Investigation. Miles Montgomery: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Michael A. Laflamme: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Locke Davenport Huyer: Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Milica Radisic: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

LDH, MM and MR are coinventors on an issued US Patent "Biomaterial comprising poly(itaconate-co-citrate-co-octanediol)" Patent # 11,666,598).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation Grant-in-Aid (G-18-0022356), National Institutes of Health Grant (2R01 HL076485), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (RGPIN 326982-10), NSERC Strategic Grant (STPGP 506689-17), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Foundation Grant (FDN-167274), Canada Foundation for Innovation/Ontario Research Fund grant (36442). M.R. was supported by Canada Research Chairs and Killam Fellowship. D.B. holds an NSERC-CREATE TOeP scholarship, S.P.G held an ORT UHN Post-doctoral Fellowship. S.C. was supported by the NSERC Postdoctoral Fellowship and NSERC-CREATE ToeP Scholarship Q.W. holds a CIHR Postdoctoral Fellowship. S.O. holds a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship. K.T.W. holds an Ontario Graduate Scholarship.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100917.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

https://data.mendeley.com/preview/wbn54698w6?a=0f1ec797-65ab-40c8-8b9c-93d87dcb7354 https://data.mendeley.com/preview/phnzbnmkwn?a=73a8db42-f9c3-45a3-ba27-0a957ade01ef

References

- 1.Heusch G. Myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury and cardioprotection in perspective. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020;17(12):773–789. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0403-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soares R.O., et al. Ischemia/reperfusion injury revisited: an overview of the latest pharmacological strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(20):5034. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laflamme M.A., M C.E. Regenerating the heart. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:845–856. doi: 10.1038/nbt1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibáñez B., Heusch G., Ovize M., Van de Werf F. Evolving therapies for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015;65(14):1454–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu L., et al. Myocardial infarction: symptoms and treatments. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015;72:865–867. doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin X., et al. A viscoelastic adhesive epicardial patch for treating myocardial infarction. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3(8):632–643. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L., et al. Injectable and conductive cardiac patches repair infarcted myocardium in rats and minipigs. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021;5(10):1157–1173. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safety and Efficacy of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Engineered Human Myocardium as Biological Ventricular Assist Tissue in Terminal Heart Failure (BioVAT-HF) 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04396899 -03-27 [cited 2023 August 15]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., et al. Recent advances in cardiac patches: materials, preparations, and properties. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022;8(9):3659–3675. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c00348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mei X., Cheng K. Recent development in therapeutic cardiac patches. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.610364. 610364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witherel C.E., Abebayehu D., Barker T.H., Spiller K.L. Macrophage and fibroblast interactions in biomaterial‐mediated fibrosis. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2019;8(4) doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson J.M., Rodriguez A., Chang D.T. Seminars in Immunology. Elsevier; 2008. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Segura T. Biomaterials-mediated regulation of macrophage cell fate. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.609297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krzemiński T.F., Nożyński J.K., Grzyb J., Porc M. Wide-spread myocardial remodeling after acute myocardial infarction in rat. Features for heart failure progression. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2008;48(2–3):100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reis L.A., et al. Biomaterials in myocardial tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016;10(1):11–28. doi: 10.1002/term.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran R.T., Yang J., Ameer G.A. Citrate-based biomaterials and their applications in regenerative engineering. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2015;45:277–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev-matsci-070214-020815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery M., et al. Flexible shape-memory scaffold for minimally invasive delivery of functional tissues. Nat. Mater. 2017;16(10):1038–1046. doi: 10.1038/nmat4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang B., et al. Platform technology for scalable assembly of instantaneously functional mosaic tissues. Sci. Adv. 2015;1(7) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davenport Huyer L., et al. One‐pot synthesis of unsaturated polyester bioelastomer with controllable material curing for microscale designs. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2019 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C., et al. High throughput omnidirectional printing of tubular microstructures from elastomeric polymers. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2022;11(23) doi: 10.1002/adhm.202201346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammadi M.H., et al. Toward hierarchical assembly of aligned cell sheets into a conical cardiac ventricle using microfabricated elastomers. Advanced Biology. 2022;6(11) doi: 10.1002/adbi.202101165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lampropoulou V., et al. Itaconate links inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase with macrophage metabolic remodeling and regulation of inflammation. Cell Metabol. 2016;24(1):158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shou Y., et al. Toward renewable and functional biomedical polymers with tunable degradation rates based on itaconic acid and 1, 8-octanediol. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021;3(4):1943–1955. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davenport Huyer L., et al. Macrophage immunomodulation through new polymers that recapitulate functional effects of itaconate as a power house of innate immunity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31(6) doi: 10.1002/adfm.202003341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang X., et al. The cardioprotective effects of citric acid and L-malic acid on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2013:2013.11. doi: 10.1155/2013/820695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Q., et al. Impact of citrate pretreatment on ventricular arrhythmia and myocardial capase-3 expression in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Genet. Mol. Res.: GMR. 2016;15(4) doi: 10.4238/gmr15048848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiang H., et al. Citrate pretreatment attenuates hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte injury via regulating microRNA-142-3p/Rac1 aix. J. Recept. Signal Transduction. 2020;40(6):560–569. doi: 10.1080/10799893.2020.1768548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Y., et al. A platform for generation of chamber-specific cardiac tissues and disease modeling. Cell. 2019;176(4):913–927. e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lian X., et al. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8(1):162–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L., et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453(7194):524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen T., Vunjak-Novakovic G. Human tissue-engineered model of myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Tissue Eng. 2019;25(9–10):711–724. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2018.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eng G., et al. Autonomous beating rate adaptation in human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7(1) doi: 10.1038/ncomms10312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]