Abstract

The aqueous two-phase system (ATPS) is an all-aqueous system fabricated from two immiscible aqueous phases. It is spontaneously assembled through physical liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and can create suitable templates like the multicompartment of the intracellular environment. Delicate structures containing multiple compartments make it possible to endow materials with advanced functions. Due to the properties of ATPSs, ATPS-based drug delivery systems exhibit excellent biocompatibility, extraordinary loading efficiency, and intelligently controlled content release, which are particularly advantageous for delivering drugs in vivo. Therefore, we will systematically review and evaluate ATPSs as an ideal drug delivery system. Based on the basic mechanisms and influencing factors in forming ATPSs, the transformation of ATPSs into valuable biomaterials is described. Afterward, we concentrate on the most recent cutting-edge research on ATPS-based delivery systems. Finally, the potential for further collaborations between ATPS-based drug-carrying biomaterials and disease diagnosis and treatment is also explored.

Key words: Aqueous two-phase systems, Drug delivery systems, Biomaterials, Microcapsules, Microparticles, Cell therapy, Cancer treatment, Organ regeneration

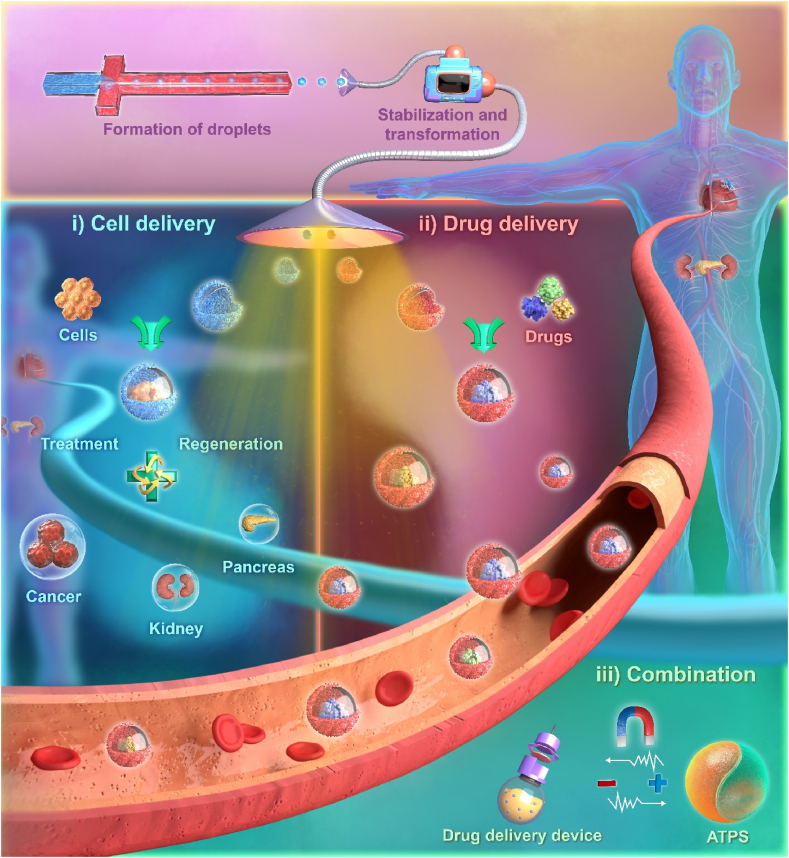

Graphical abstract

This review starts with the properties and principles of aqueous two-phase systems (ATPSs) and summarizes the process of transforming ATPSs into ideal delivery systems in a trilogy.

1. Introduction

Drugs are essential in preventing and treating cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and chronic respiratory disease1,2. However, biological barriers, insufficient selectivity, and complex enzyme systems may cause the drug to be destroyed before it reaches the diseased tissue, failing to achieve the desired therapeutic effect3,4. To address this dilemma, researchers are currently conducting intense research and hope to explore prospects for a safe, efficient, and stable drug delivery system5. Primarily, the ideal drug delivery system should have a high loading capacity and low biotoxicity without affecting drug activity6. Moreover, to achieve personalized drug release, a delicate structure and an intelligent release procedure are also expected7.

The aqueous two-phase system (ATPS)-based drug delivery system offers more precise and controlled strategies and is an appropriate candidate. As an all-aqueous system, ATPSs are fabricated from two immiscible aqueous phases8,9. The formation mechanism is the physical liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) that occurs when the concentration of the two aqueous solutions exceeds a critical value10. In most cases, the solutes are two incompatible polymers or one polymer and one salt11. Since being discovered in 1869, the applications of ATPSs in enriching biomolecules or cells12, designing membrane-less organelles13, artificial cells14, and biomaterials15 have been extensively studied.

ATPS-based biomaterials are favored in the biomedical field because of their unique application advantages16. The formation of ATPSs is spontaneously assembled and distributed through LLPS under mild conditions, which is similar to the formation progress of membrane-less compartments in eukaryotic cells17. In fact, the eukaryotic cell is an extremely complex multicompartment structure, where metabolic activities and signal transduction are regulated methodically with the aid of many different membrane-less subcompartments18. Therefore, the exquisite multicompartment structure is the basis for the realization of intelligent temporal and spatial adjustment functions19. Interestingly, ATPSs can utilize a similar formation mechanism to create suitable templates similar to the multicompartment of the intracellular environment. Based on these templates, advanced biomaterials with complex structures and functions are manufactured, namely, ATPS-based biomaterials20. The correlation between ATPSs and eukaryotic cells provides a sufficient theoretical basis for their applications in biotechnology and biomaterials. Additionally, thanks to the highly similar structure to that inside cells and the formation of the system without organic solvents, ATPS-based biomaterials have excellent biocompatibility and seem to be an ideal choice for biomaterials at present9.

Numerous reports have demonstrated that ATPS-based biomaterials have extraordinary loading capacity21, some even as high as 99%, because of the high enrichment ability of ATPSs22. In eukaryotic cells, membrane-less microcompartments can be formed by LLPS23. Cellular biomolecules, including nucleic acids and proteins, can be selectively enriched within specific microcompartments based on their distribution properties, facilitating precise microcompartment reactions24,25. Accordingly, in ATPSs, drugs can also be distributed within a specific phase of two independent phases according to their distribution characteristics. Thus, drugs can be locally enriched to achieve extremely high concentrations and encapsulation rates26. In addition, ATPS-based biomaterials are composed of nonorganic solvents and have significant biocompatibility27. This property can prevent the denaturation of hydrophilic drugs such as proteins, mitigate carrier cytotoxicity, and broaden the range of suitable drug cargoes. Generally, the microcapsule structure is the most representative structure of ATPS-based biomaterials. By controlling environmental factors such as pH and ionic strength, the microcapsule shell can be caused to disintegrate and break at a specific time and site and subsequently release the drug28. This mechanism enables personalized and intelligent drug delivery, ensures specific drug release at the targeted site, and improves drug safety and therapeutic effects29. In conclusion, ATPS-based biomaterials are an ideal delivery system for disease treatment.

At present, there are numerous studies on ATPSs in the field of biotechnology, and their basic properties, such as interface dynamics, have been reviewed and reported in detail. However, there is currently a lack of systematic reviews of ATPSs as effective delivery systems for disease treatment. Given the existing research on ATPS-based drug delivery systems, we start with the essential characteristics of ATPSs and summarize the process of transforming ATPSs into delivery systems in a trilogy.

-

1)

Formation of all-aqueous droplets;

-

2)

Stabilization and transformation of all-aqueous droplets;

-

3)

Application of ATPS-based delivery systems in disease treatment.

The trilogy transforms ATPSs into suitable drug delivery systems, which possess powerful drug delivery capability and show promise for application (Fig. 1). In this review, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the trilogy and evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of ATPS-based biomaterials as delivery systems. Finally, potential future developments will be discussed.

Figure 1.

This overview describes the formation of all-aqueous droplets from ATPS and the stabilization and transformation to obtain ATPS-based biomaterials, which can then participate in drug and cell delivery in vivo. The combination of ATPSs with other delivery systems to improve their delivery capacity is also an important part of ATPS-based delivery systems.

2. The cornerstone of the trilogy—properties and principles of ATPSs

The properties and principles of ATPSs are very important for the formation of ATPSs and ATPS-based delivery systems. Exploring the characteristics of ATPSs, the template of ATPS-based delivery systems, can provide a deeper understanding of the characteristics, design, and application of delivery systems. This section will start with the formation mechanism of ATPSs and analyze the properties of ATPSs. Furthermore, the advantages of ATPS-based delivery systems in drug delivery and disease treatment will be discussed, including high loading efficiency, low biotoxicity, and intelligent release program.

2.1. Formation mechanism of ATPSs-basis for delivery capability

From a thermodynamic point of view, if a liquid phase is separated into two insoluble liquid phases, the change in enthalpy is greater than the change in entropy. The former drives liquid phase separation, and the latter contributes to liquid phase mixing30. Furthermore, from the perspective of quantitative analysis, phase separation depends on the Gibbs free energy of the system as in Eq. (1):

| ΔG = ΔH − TΔS | (1) |

where ΔG means the change in Gibbs free energy; ΔH means the change in enthalpy; T means the temperature, and ΔS means the change in entropy. When ΔG < 0, the two phases mix spontaneously, so phase separation cannot occur. Nevertheless, if ΔG > 0, which suggests that enthalpy contributes more to the system, the condition for separation is achieved31,32. For example, for the process of mutual exclusion between solutes (polymers or salts) in two liquid phases in an ATPS, ΔH > 0 and ΔS < 0; accordingly, their contributions to the system are decisive for the occurrence of phase separation33 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The properties and principles of ATPSs: The horizontal and vertical coordinates indicate the different phases. The blue area indicates the mixed phase (single phase), and the red area indicates two aqueous phases (phase separation). Points 1 and 3 of the tie lines indicate the final compositions of the two immiscible aqueous phases after complete phase separation, and the critical point and point 2 represent conditions in which the two phases are of equal concentration. The trend of phase separation is influenced by the variation in the influencing factors on the left and right sides.

The construction and exchange of ATPSs rely heavily on the reaction kinetics, particularly the diffusion and exchange rate between the solvent and nonsolvent components34. A necessary condition for separating liquid phases is reaching a critical comparatively high concentration35,36, which means that determining this concentration is vital in practical applications. In general, an increase in solute concentration in a solution can increase the tendency to phase separation. Other factors, such as temperature, solution conditions (including pH, viscosity, and osmotic pressure), and various external parameters, can also influence the phase separation31,37, 38, 39. Considering these influencing factors, a fictive binodal phase diagram mainly consisting of a binodal curve is plotted by connecting the dots at these critical concentrations to promote analyzing phase separation. Phase diagram is a useful tool for obtaining important information about the characteristics of a system, such as its global composition, top phase composition, bottom phase composition, and critical points40. The distance of a curve from the origin of a phase diagram can provide an indication of the minimum concentration required to form an ATPS; the closer the curve is to the origin, the lower the concentration required41. The critical concentration point of an ATPS is located at the center of the binodal curve, while the two endpoints represent the final aqueous phase compositions. The binodal curve also serves to divide the single-phase and two-phase zones. The phase diagram provides information about the concentration at which the two phases can form an ATPS—the region below the curve indicates that the system is monophasic, while the region above the curve suggests that the system is biphasic38. Additionally, state transitions between single and two phases can occur by altering conditions42. Generally, a higher pH43, lower temperature39, larger molecular weight of the ATPS components44,45, and greater density difference46 and hydrophobicity gap between the two solutes forming the ATPS31 cause the biphasic curve to move to the origin, that is, the biphasic region becomes larger (Fig. 2). The ATPS formation mechanism is affected by temperature, pH, and other conditions, so the rational application and regulation of the influencing factors will be of great benefit to the formation of ATPS-based delivery systems.

2.2. Unique properties of ATPSs—as micro delivery systems

2.2.1. Superior biocompatibility and similarity to the intracellular structure

Oil-water (o/w) systems were previously applied as carriers by generating water droplets in an oil environment. However, the toxicity of certain oils can potentially harm the activity of biological samples47. For instance, organic solvents such as petroleum have been shown to denature biomolecules such as proteins and enzymes, disrupt the formation of biologics and tissues, inhibit cell growth, and accelerate cell death47. However, an ATPS, as an all-aqueous system, ingeniously solves this problem and endows ATPS-based biomaterials with low cytotoxicity48.

As an all-aqueous environment, an ATPS establishes favorable conditions for simulating the intracellular cytoplasmic environment. Aqueous phase separation may be essential in constructing and assembling biological components. Biomolecules can be selectively partitioned into different aqueous phases to achieve a state of enrichment, and this selectivity is related to their properties and can be enhanced in the presence of protein ligands or enzymes48. The ability of ATPSs to enrich substances guarantees the efficient encapsulation of drugs in the drug-loading stage of ATPS-based delivery systems. In addition, semipermeable membranes can regulate the transfer of biochemical reactions and biomolecules between chambers within an aqueous phase, creating a stable and dynamic microenvironment for cellular metabolism49. Therefore, compartmentalizing different biomolecules and biological organelles in ATPSs represents a new way to achieve cell simulation9. The formation of an artificial cell simulation compartment enables protein and DNA synthesis to occur in a physiological microenvironment that effectively preserves the molecular structures and biological functions of these biomolecules. Accordingly, ATPS-based delivery systems based on the structure of the artificial cell simulation compartment, a delicate structure combining multiple compartments, have also formed corresponding advanced structures. On this basis, the controlled release of the drug can be designed individually, and the drug can be responsively released under certain conditions by adjusting the structure to obtain the ideal drug delivery effect.

2.2.2. Interface with extremely low interfacial tension

In a system comprising two immiscible aqueous phases, the interfacial tension of the water-water (w/w) interface is extremely low, sometimes even less than 1 μN/m, which is several orders of magnitude smaller than that of the usual o/w interface50. Due to this extremely low interfacial tension, the Rayleigh-Plateau instability of the all-aqueous jet has a low effective growth rate51. The Rayleigh-Plateau instability of the jet is the key to transforming the jet into droplets52. Therefore, ATPSs do not easily form droplets and instead tend to form all-aqueous jets in microfluidic devices53, which is a significant obstacle in transforming ATPSs into biomaterials. Several strategies have been proposed to address this dilemma and will be introduced later.

The manipulation of particles at low-tension w/w interfaces is also of increasing interest. Extremely low tension can be achieved in ATPSs by adjusting both solutes’ concentrations54. The comparatively softer and broader range of interfacial tension can help to elucidate the interfacial properties of w/w systems, such as the response to external stimuli55. Moreover, the low interfacial tension is advantageous for applications that require low-tension w/w systems, such as the interfacial assembly of microparticles or nanoparticles, particularly in specific transport systems with dynamic changes53. Therefore, the rational application of extremely low interfacial tension or resolution of its limitations would greatly benefit the preparation and formation of ATPS-based delivery systems.

3. Part one of the trilogy: Fabrication of all-aqueous droplets

Microfluidic technology is an important basis for the formation of ATPS droplets. In a suitable microfluidic device, the templates of ATPS-based biomaterials can be obtained by precisely designing and adjusting the structure of ATPS droplets56. However, due to the extremely low tension at the w/w interface of ATPSs, it is difficult for ATPSs to form droplets, and they tend to form all-aqueous jets in the microfluidic device instead. To overcome this dilemma and obtain ideal droplet templates, researchers have proposed several solutions to obtain satisfactory results in droplet formation by introducing external devices or mediums (Table 1)57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64.

Table 1.

Summary of methods used for the fabrication of all-aqueous droplets.

| Method used | The ingredient of the ATPSs | Production rate (drops/s) | Diameter (μm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Medium-induced formation | ||||

| (a) Water | PEG (35 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | ∼15–50 | ∼10–110 | 57 |

| (b) Oil | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (40 kDa) | 2100 | 10–360 | 58 |

| (2) Mechanical disturbance-induced formation | ||||

| (a) Piezo-electric bending disk | PEG (35 kDa) + DEX (110 kDa) | ∼50 | 30–60 | 59 |

| (b) Pin actuator | PEG (35 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | ∼2.5 | ∼0.9–3.4 nL | 60 |

| (c) Mechanical vibrator | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | ∼30 | 60–200 | 61 |

| PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | ∼9 | ∼140–200 | 62 | |

| (3) Electricity-induced formation | ||||

| (a) Electrospray | PEG (20 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | – | ∼45–2250 | 63 |

| (b) Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) perturbation | TBAB (322.38 Da) + AS (132.14 Da) | ∼5 | – | 64 |

‒, not applicable.

3.1. Medium-induced formation

All-aqueous droplets can be generated by introducing a medium and perturbing the all-aqueous interface with the aid of the medium. For biocompatibility considerations, water is the best choice65. With the highly biocompatible poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) phase as the medium and weak hydrostatic pressure applied to the flowing dextran (DEX) phase, ATPS droplets with low interfacial tension could be formed without any external disturbance, making the technique very easy to implement57. The difficulty in forming all-aqueous droplets is due to the very low interfacial tension, which, unlike the hydrostatic pressure drive, seems better compensated for by the high interfacial tension at the o/w interface. An oil droplet chopper has been shown to achieve this compensation. When an oil droplet passes through a narrow orifice in the collecting capillary, the water interface can become distorted. As the amplitude of the perturbation increases, the interface can eventually rupture and form droplets58. In this application, the dilemma of the low interfacial tension of ATPSs is solved by the oil phase medium with high interfacial tension. The resulting droplets are also easier to separate, which is a promising preparation strategy.

3.2. Mechanical disturbance-induced formation

The low interfacial tension of ATPSs restricts the range of flow rates that enable the spontaneous formation of droplets. When the interfacial tension is reduced hundreds of times compared to the o/w system, the flow rate must be correspondingly reduced before the spontaneous formation of droplets is possible51. Limited by the range of flow velocities in practical applications, this dilemma can be solved by applying an external mechanical force59. Theoretically, introducing a particular frequency of external mechanical disturbance can enhance the Rayleigh-Plateau instability of the liquid jet to avoid the need to reduce the flow rate. In addition, this disturbance often appears regular and consistent, making it an outstanding way to form droplets with controllable sizes and uniform specifications.

With the addition of a piezo-electric bending disk device, the all-aqueous jet was periodically perturbed to stably produce size-regulated droplets without being limited by the liquid flow rate and surface charge requirements59. In another case, a microfluidic system was developed that utilized rounded channels with orifices and incorporated braille pin valving to generate droplets through efficient periodic valving closure. The system could achieve finer control by adjusting the flow ratio and the operating frequency of the Braille pin60. In addition, the method of generating mechanical perturbation by connecting mechanical vibrators has become an essential method for the formation of all-aqueous droplets and has been widely used and developed61,62.

3.3. Electricity-induced formation

In addition to mechanical perturbation, the direct use of electricity to generate droplets is a sensible strategy. Electrospray technology has been widely used to produce droplets with adjustable size and height66. The technology can efficiently generate adjustable droplets by adjusting the voltage between the droplet and the continuous phase63,67. In addition to electrospray, microfluidic devices can also utilize electrostatic fields. For instance, tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB) and ammonium sulfate (AS), two incompatible solutes with different electrophoretic mobilities, have been used as ATPS solutes for electricity-induced droplet formation. With the participation of the electric field, droplets were formed64.

4. Part two of the trilogy: Stabilization and transformation of all-aqueous droplets

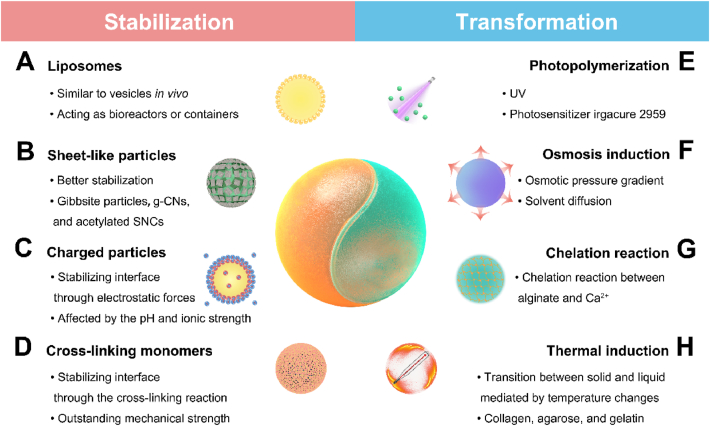

As a type of oil-free emulsion, all-aqueous droplets exhibit good biocompatibility and low toxicity compared to oil-containing emulsions. The all-aqueous droplets forming in ATPSs can fabricate advanced biomaterials, such as microparticles and microcapsules, with broad application prospects for delivering bioactive ingredients and drugs. The premise of these applications is to stabilize the template and complete the transformation of all-aqueous droplets to biomaterials. This section presents the latest advances in stabilizing ATPSs in recent years, and some ATPSs can even be directly transformed into functional biomaterials. On the basis of existing transformation concepts, we believe that more stabilized ATPSs may be converted into biomaterials (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the stabilization and transformation of all-aqueous droplets.

4.1. Stabilization of all-aqueous droplets

The first step in converting all-aqueous droplets into vehicles is to stabilize the all-aqueous interface. Due to the high interfacial thickness of the w/w interface, small molecules such as surfactants cannot effectively stabilize water-in-water emulsions. Only particles of comparable thickness can be incorporated into the interface68,69. Therefore, several strategies have been proposed, such as using liposomes70, sheet-like nanoparticles71, charged particles66, and cross-linking monomers72, to realize the interfacial stabilization of all-aqueous droplets and transform them into functional biomaterials. Most of these biomaterials consist of a stable shell and a core of droplets, that is, microcapsules (Table 2)66,68,70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77.

Table 2.

Summary of methods used to stabilize all-aqueous droplets.

| Microparticle to stabilize and transform | Diameter of microparticle (nm) (if available) | The ingredients of the ATPSs | The advantage of the materials obtained | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Liposomes | ||||

| (a) PEGylated liposomes | ∼130 | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (10 kDa) | (a) Possessing some characteristics of vesicles in vivo; (b) Being able to function as microreactors of the ribozyme cleavage reaction |

73 |

| (b) Lipid combinations containing equal mole fraction of zwitterionic phosphatidylcholine and anionic phosphatidylglycerol headgroups, with 2.8% (mol/mol) 2 kDa PEGylated lipid | – | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (10 kDa), Ficoll 70 kDa, Na2SO4 | (a) Broadening the range of compositions possible for liposome-inducing stabilization; (b) Being able to function as microreactors of enzyme reaction to form CaCO3 |

70,74 |

| (2) Sheet-like particles | ||||

| (a) Gibbsite particles | 167 ± 30 (thickness of 6.6 ± 1.1) | Fish gelatin (100 kDa) + DEX (100 kDa) | Blocking more interface regions while having a lower mass than nanospheres | 68 |

| (b) g-CNs | <300 | PEG (35 kDa) + DEX (40 kDa) | (a) Stabilizing the ATPS emulsions up to 16 weeks; (b) May be combined with photocatalysis to achieve light-controlled release |

71 |

| (c) SNCs | ∼100 (thickness of 8–10) | PEG (10 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | Regulating the emulsion types by changing surface properties and aggregation levels of SNCs | 75 |

| (3) Charged particles | ||||

| (a) Poly (allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) and PSS | – | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | Triggering the release of encapsulated components by changing the pH or ionic strength | 66 |

| (b) Demethylated citrus pectin and chitosan | – | PEG (6 kDa) + DEX (70 kDa) | Possessing excellent mechanical properties and sustained release ability | 76 |

| (4) Cross-linking monomers | ||||

| (a) Tetra-PEG | – | Tetra-PEG (10 kDa) + DEX (32–45 kDa) | (a) Possessing various hydrogel properties; (b) The reaction rate changed and the product structure altered at different pH |

72 |

| (b) Amyloid nanofibrils | The thickness of ∼15 and the average length of 600 | PEG (20 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | Fabricating highly robust vesicles with semipermeability | 77 |

‒, not applicable.

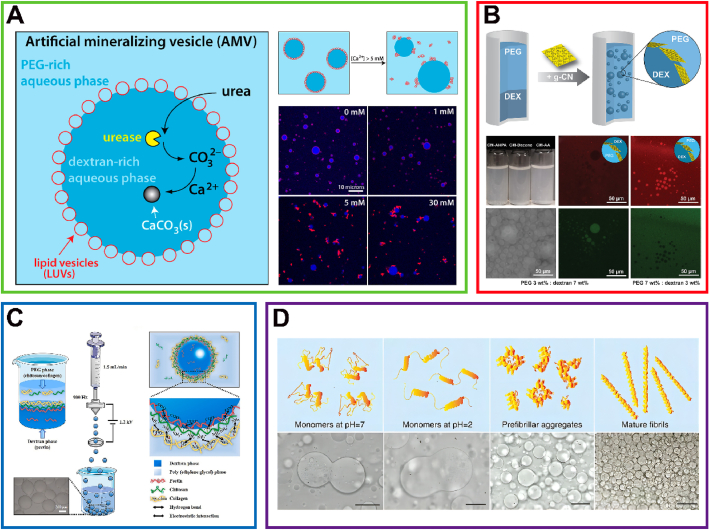

4.1.1. Liposomes

As biodegradable and highly biocompatible lipid vesicles, liposomes have been increasingly studied in cancer therapy as active drug carriers78. The lipid-stabilized all-aqueous droplet possesses some characteristics of vesicles in vivo. Therefore, similar to lipid-constructed vesicles79,80, these droplets can form suitable bioreactors or containers to encapsulate biomolecules. For instance, negatively charged liposomes were assembled into the w/w interface of a PEG/DEX ATPS. The resulting stabilized droplets were selectively permeable to some extent and could function as microreactors, simulating the environment inside the primitive cell, where the ribozyme cleavage reaction took place73. Subsequently, artificial vesicles stabilized by liposomes were also used to study artificial biomimetic mineralization, as shown in Fig. 4A. This vesicle was considered an ideal testbed due to its ease of preparation and high efficiency of macromolecule encapsulation compared with typical biomineralized vesicles70. Subsequently, more suitable compositions were explored for liposome-stabilized all-aqueous droplet bioreactors to facilitate their development. Furthermore, vortexing was found to be an effective method to reduce the time and cost of bioreactor production74. Overall, liposome-stabilized vesicles have similar properties to cells and organelles and seem promising in biomimetic research and for the encapsulation of biomolecules.

Figure 4.

Stabilization of all-aqueous droplets. (A) Liposome-stabilized all-aqueous droplets. Diagram of the enzymatic reaction and production of artificial mineralizing vesicles to generate CaCO3(s). Additionally, the confocal images in the bottom right corner display the different calcium ion concentrations in the liposomes. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 70. Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society. (B) Sheet-like particle-stabilized all-aqueous droplets. Schematic representation of the formation of w/w Pickering emulsions via g-CN stabilization. Confocal images below show g-CN stabilized Pickering emulsions containing PEG (stained with FITC) and DEX (stained with RhB). Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 71. Copyright © 2020 Wiley-VCH. (C) Charged particle-stabilized all-aqueous droplets. Preparation and interface interactions of pectin-chitosan-collagen composite microcapsules. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 76. Copyright © 2021 Elsevier. (D) Cross-linking monomer-stabilized all-aqueous droplets. Graphics of lysozyme protein assembly during various fibrillization stages. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 77. Copyright © 2016 The Authors.

4.1.2. Sheet-like particles

Plate-like particles exhibit stronger adsorption than spherical particles with the same maximum cross-section and are therefore favored for stabilizing all-aqueous interfaces. A common strategy for the stabilization of all-aqueous droplets is adsorbing certain solid particles on the interface to suppress the coalescence of the droplets and thus achieve effective stabilization71. The extremely low interfacial tension of the all-aqueous interface weakens the interface's adsorption energy, which means that larger particles are required to be trapped in it. However, it also makes the particles settle quickly and causes system instability53. However, plate-like particles can stably remain blocking a relatively large area of the w/w interface and have thus proven to be an effective interface stabilizer.

For example, gibbsite nanoplates have been shown to effectively maintain and stabilize the ATPS composed of DEX and nongelling fish gelatin for over two weeks81. Not long ago, graphitic carbon nitride (g-CN) was applied as a Pickering stabilizer for the PEG-DEX all-aqueous emulsion system and lasted 16 weeks (Fig. 4B). In addition, the emulsion stabilized by g-CN could be demulsified via light irradiation, introducing photocatalytic properties to the all-aqueous system. This case also provides a new direction for the future application of all-aqueous systems in bioactive molecule loading and light-controlled release71. Taking inspiration from platelet-like starch nanocrystals (SNCs) as effective stabilizers for oil-in-water Pickering emulsions50, researchers also utilized surface-modified nanosheets with two strategies, crosslinking and acetylation, to stabilize the ATPS interface. Testing revealed that acetylated SNC exhibited higher emulsifying efficiency, resulting in processed emulsions with reduced viscosity and enhanced stabilization75. These nanosheet-like particles or nanorods hold promise for stabilizing interfaces due to their sizeable interfacial contact area and lighter mass.

4.1.3. Charged particles

Charged particles were used for the first time to stabilize interfaces by interfacial complexing. With the help of the electrospray technique, the interface between the droplet and PEG solution was gradually coated with a shell formed by the complexation of the pair of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes (PEs). Then, a capsule containing a core of biocompatible DEX solution was produced. This capsule could respond to changes in the pH or ionic strength of the external environment, thereby triggering the release of encapsulated materials66.

In a recent study, pectin-chitosan-collagen composite microcapsules (PCCMs) were manufactured in an ATPS76. As shown in Fig. 4C, the inner phase solution of 20% (w/w) DEX and 0.25% (w/w) demethylated citrus pectin was sprayed into droplets via the all-aqueous electrospray technique. Then, these droplets fell into the outer phase solution of 15% (w/w) PEG and 0.5% (w/w) chitosan with or without collagen. Through electrostatic interaction, the anionic pectin interacted with cationic chitosan. Weak electrostatic interactions also participate in the attachment of chitosan to collagen. All characteristics indicated that the PCCM showed extraordinary mechanical properties and sustained release ability, which would facilitate the encapsulation and delivery of active biomacromolecules. Through the electrostatic complexation of charged particles, the all-aqueous interface was well stabilized, and a shell was also established, which seemed extraordinarily promising for the practical application of biomaterials. In summary, charged particles can form microcapsules with excellent mechanical properties through electrostatic interaction. Additionally, the stability of the prepared microcapsules is easily affected by the pH and ionic strength of the surrounding environment due to the properties of charged particles. This property is conducive to carrying drugs and releasing them at specific sites and is therefore expected to enable the dual-conditional temporally and spatially controlled release of drugs, which broadens the pathway for ATPSs to deliver drugs or other small molecules in vivo.

4.1.4. Cross-linking monomers

In addition to electrostatic complexation, cross-linking reactions of macromonomers are also widely used72. For instance, microcapsules could also be formed through the cross-end coupling reaction of tetra-PEG. The terminal cross-coupling reaction occurred during the phase separation-induced migration of tetra-PEG macromonomers that could form a hydrogel shell outside the DEX core to prepare microcapsules. Research on the effect of protein cross-linking on the stabilization of interfaces has also been a hot topic in recent years. By adding amyloid nanofibrils to the DEX phase, when the DEX-rich dispersed phase formed an ATPS with the PEG-rich phase, robust fibrillosomes formed after reaction at 65 °C for 12 h. The results are shown in Fig. 4D, where the fibrillosomes were superior semipermeable stretchable capsules. Furthermore, the thickness of the capsule shell could be regulated by fibril growth and multilayer deposition77. Due to the cross-linking reaction, the mechanical strength of the microcapsules obtained is particularly outstanding. In one study, different cross-linking speeds and results at different pH values were also reported72, which should be valuable for research on biosensors and drug delivery.

4.2. Transformation of all-aqueous droplets

All-aqueous droplets can be readily transformed into microparticles with simple structures using methods such as light triggering and heat triggering. Microparticles have emerged as versatile functional biomaterials with applications ranging from drug delivery and tissue engineering to biosensing and beyond82,83. Herein, we briefly discuss several preparation strategies for transforming ATPS droplets into microparticles (Table 3)20,84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90.

Table 3.

Summary of strategies used to transform all-aqueous droplets.

| Strategy | The ingredient of the ATPSs | The advantage of the materials obtained | Application object or scenario | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Photopolymerization | DEX + GMA-gelatin + Irgacure 2959 |

Fast reaction speed and high cell survival rate |

Cell therapies or in vitro test systems |

84 |

| Gelatin + K2HPO4 | Stable structure | Release-controlled drug delivery vehicles for water-soluble drugs |

85 | |

| PEGDA (0.7 kDa) + DEX (20 kDa) |

Produces crescent-shaped hydrogel particles |

Cultivation and manipulation of cells in micro-buckets |

86 | |

| PEGDA + DEX | (a) Adjustability of the size, shape, and roughness of the gel particles (a) Design of hydrogel particles with autonomous movement capability |

Micro- and nanomotors |

87 | |

| (2) Osmosis induction | PEG (4, 6, 8, 10, and 20 kDa) + Soluble starch + DEX (500 kDa) |

Preservation of protein activity |

Protein encapsulation and 3D cell printing |

20 |

| (3) Chelation reaction | PEG (8 and 20 kDa) + DEX (70 and 500 kDa) |

Higher biocompatibility, stability, controllability, and flexibility in a high throughput manner |

Bio-oriented microparticles synthesizing, microcarriers fabricating, and tissue engineering |

88 |

| PEG (35 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) |

All-biocompatible | Drug delivery vehicles |

89 | |

| (4) Thermal induction | PEG (6 kDa) + DEX (200 kDa) |

Produces uniformly shaped particles |

Simulation of artificial cells and membrane-less organelles |

90 |

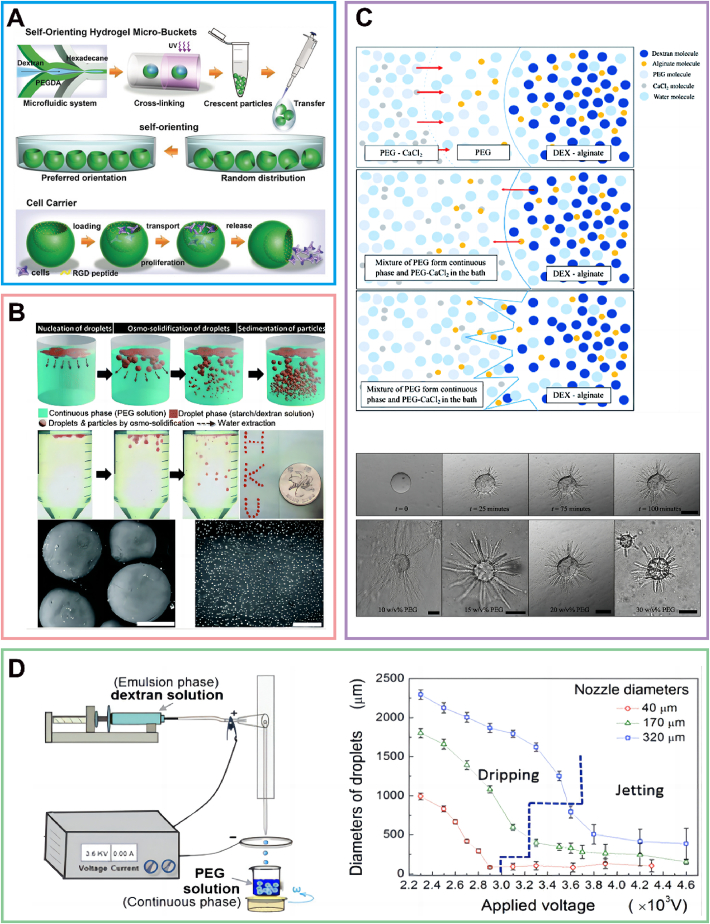

4.2.1. Photopolymerization

As the material choice is flexible and the reaction can be completed in a short time, photopolymerization is a widely used way to transform droplets into microparticles91. For instance, in one study, microparticles were formed using a water-in-water emulsion technique by simultaneously irradiating the system with 365 nm light in the presence of the photosensitizer Irgacure 2959. The resulting microparticles exhibited potential applications in cell-based therapy or in vitro test systems. Additionally, the appropriate conditions were identified in experiments utilizing glycidyl methacrylate gelatin and cells84. In addition, considering the phosphate salts in physiologic buffers and the broadly known biocompatible properties of gelatin, ATPS-based gelatin hydrogel particles with K2HPO4 buffer and gelatin prepolymer have been proposed as a biocompatible therapeutic delivery platform85. A crescent-shaped hydrogel particle, the “king” of complex particles, was created in a microfluidic device through the selective photocrosslinking of a component in the ATPS (Fig. 5A). Loading cells into the microbuckets was achieved with ease when the cavity was oriented upward. After cell adhesion and/or proliferation, the hydrogel microbuckets were capable of transporting and releasing the cells86,92. This approach fully showed the high biocompatibility of these ATPS-based microparticles. Interestingly, in another study, a hydrogel microparticle with autonomous movement was designed based on photopolymerization87.

Figure 5.

Transformation of all-aqueous droplets. (A) Crescent-shaped, peptide-modified hydrogel microparticles fabricated via microfluidics, self-orient underwater and function as cell carriers. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 86. Copyright © 2018 Wiley-VCH. (B) A schematic of the osmo-solidification process is presented alongside optical images of the procedure and the final particles dyed with Nile red, as well as SEM images of osmo-solidified starch particles (scale bar: 400 μm) and DEX nanoparticles (scale bar: 4 μm). Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 20. Copyright © 2016 Royal Society of Chemistry. (C) The figure illustrates the process and outcomes of spike formation on DEX-alginate droplets in a PEG-CaCl2 polymerization bath, emphasizing the roles of diffusion, chemical equilibrium, and concentration gradients in shaping the unique morphology of the polymerized particles. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 89. Copyright © 2019 Royal Society of Chemistry. (D) Depiction of the production of size-tunable water-in-water emulsions via all-aqueous electrospray and their size dependence on an applied voltage. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 63. Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society.

4.2.2. Osmosis induction

Maximizing the use of solvent diffusion is an effective approach to induce the transformation of emulsion droplets into microparticles. It is generally observed that the biological activity of bioactive ingredients, such as proteins encapsulated in solidified particles, can be lost irreversibly if nonaqueous solvents or unfavorable conditions cannot be removed. In a typical study, an osmo-solidification method was developed to enable protein encapsulation and solidification of droplets into particles in a single step, resulting in enhanced stability of the encapsulated proteins to an unparalleled level (Fig. 5B)20. To elaborate, if the concentrations of the two phases in the ATPS are not in equilibrium, an osmotic pressure gradient across the w/w interface will be present. This results in the movement of water from one aqueous phase to the other9. Experimentally, water with 10% (w/w) starch was pumped using a syringe pump and electrospray into the PEG solution, resulting in the matrix concentration build-up triggering the solidification of droplets. Accordingly, 8% (w/w) DEX solution mixed with PEG solution was also used to prepare the nanodroplets. Then, these nanodroplets transformed into DEX nanoparticles after osmo-solidification20.

4.2.3. Chelation reaction

ATPS has exhibited remarkable proficiency in generating gel microspheres, particularly in the context of alginate-based microspheres, by employing the principle of chelation reaction. Alginate, a linear copolymer derived from various kelp species, has the unique ability to crosslink in aqueous environments93. The resulting gel microspheres showcase the tremendous potential for cell delivery applications88,94. Furthermore, a biocompatible spiky microparticle was synthesized through the chelation of alginate and calcium chloride (CaCl2) within a PEG/DEX ATPS. As shown in Fig. 5C, the length of these spikes could be controlled by adjusting the PEG concentration in the polymerization bath, and this feature could be utilized to create biocompatible spiky surfaces or spiky threads89.

4.2.4. Thermal induction

Because of the transition between solid and liquid droplets made up of collagen, agarose, and gelatin with ambient temperature changes, thermal induction is an effective way to produce microparticles95,96. For example, in Fig. 5D, 1.5 mg/mL collagen was added to the emulsion of a mixture of DEX and PEG. After phase equilibrium, no less than 90% (w/w) of collagens entered the DEX-rich phase spontaneously, where the partitioning effect allowed the formation of collagen porous microparticles by thermal gelation at 37 °C63. In addition to the traditional use of thermally induced solid-liquid conversion to produce microparticles, a recent study used the principle of DNA denaturation and renaturation to prepare hydrogel microparticles. In an experimental study, a microarray of DEX droplets containing DNA wrapped by a continuous polyethylene PEG phase with magnesium ions and spermine was produced. Next, DNA droplets were formed inside the DEX phase by heating the device and refrigerating the apparatus, resulting in uniform-sized DNA hydrogel particles at the interface of the DEX/PEG droplets. This approach serves as a parallel model for creating artificial cells and membrane-less organelles90.

5. Part three of the trilogy: ATPS-based delivery systems and disease treatment

ATPS-based disease treatment mainly delivers drugs in vivo with the help of biomaterials or systems obtained from the stabilization or transformation of droplets derived from ATPSs. Moreover, cells can be delivered as a special kind of drug for cancer treatment and even the more popular in vivo in-situ tissue regeneration. In addition, ATPSs can be combined with other drug delivery systems to enhance the delivery capacity of the system. In summary, ATPS-based delivery systems have become an essential tool for disease treatment.

5.1. Drug delivery with ATPS-based biomaterials

Drug delivery requires the carrier to possess high biocompatibility and even temporally and spatially controlled release characteristics. The aqueous environment of ATPS-based biomaterials, which is rich in water, can effectively protect cells and fragile drugs such as peptides, proteins, oligonucleotides, and DNA97,98. Moreover, the biomaterials use ATPS-derived droplets as a template and often have a variety of delicate structures that facilitate the precise regulation of drug release. In summary, ATPS-based biomaterials have significant advantages in drug delivery. Here, we introduce some applications of ATPS-based biomaterials in drug delivery.

5.1.1. Application of ATPS-based biomaterials with simple structures

In most cases, microgel particles based on ATPSs possess simple structures and appear as simple spherical particles. Microgel particles are often generated from natural macromolecular materials with good biocompatibility. Furthermore, ATPS-based biomaterials have the advantages of a high drug loading efficiency and controlled release ability, making them highly promising for drug delivery. In recent years, microparticle materials have received increasing attention as vehicles for delivering active substances99. Here, we discuss the properties and applications of microgel particles prepared from natural and synthetic macromolecular monomers in drug delivery (Table 4)22,100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105.

Table 4.

Summary of ATPS-based biomaterials with simple structures for drug delivery.

| ATPS-based biomaterial used for drug delivery | Delivered component | The ingredient of the ATPSs | The advantage of the materials obtained | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Natural macromolecular monomers | ||||

| (a) Gelatin microgels | EGFP | PEG (1.9–12.5 kDa) + gelatin (0.03–100 kDa) | The EGFP was encapsulated in the gelatin microgels owing to the electrostatic attraction between gelatin and EGFP | 22 |

| (b) Gelatin methacrylate microparticles | FGF2 | PEG (7.3–9.3 kDa) + gelatin | The FGF2 was well loaded and exerted good therapeutic effects | 100 |

| (c) HES-HEMA microparticles | Lysozyme | PEG + HES-HEMA | Lysozyme-loaded microparticles released in vitro for more than 4 months | 101 |

| (d) CMCH microparticles | Naproxen and ropivacaine | PEG (10 kDa) + CMCH | The microparticles delivering drugs can be embedded in the thermosensitive hydrogels to achieve drug delivery for local wound | 102 |

| (e) CMCH microparticles | Calcium ions, polymerized dopamine | PEG (10 kDa) + CMCH | Possessing potential for rapid hemostasis | 103 |

| (2) Synthetic macromolecular monomers | ||||

| (a) PEG-CaM-PEG microparticles | VEGF, BMP-2 | PEG-CaM-PEG + raffinose + Ca2+ | Possessing high encapsulation efficiencies and releasing drugs at a predetermined time | 104 |

| (b) Macromonomers hydrogel microparticles | BSA and lysozyme | Norbornene- and thiol-modified four- and eight-armed poly (ethylene glycol) (10 kDa) + DEX (100–200 kDa) | Inhalable controlled drugs release system evading alveolar macrophages | 105 |

5.1.1.1. Natural macromolecular monomers

Starch and gelatin are natural macromolecular materials106. The simple conversion of ATPSs could prepare corresponding microgel particles with high drug-loading performance. For instance, we can confirm that enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was successfully and stably embedded in the gelatin microgel by adopting EGFP as the model protein and observing the green fluorescence. The results also indicate that the gelatin microgel generated by the ATPS comprising PEG and gelatin had excellent drug-carrying potential22. Gelatin methacrylate microparticles were prepared in a w/w system triggered by ultraviolet light. The microspheres were stably loaded with fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) with high loading efficiency and effectively activated the proliferation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs), indicating efficient release of FGF2. In further experiments, the microspheres significantly improved the therapeutic efficacy of ACSs in a wound-healing mouse model100. In addition to gelatin, starch was converted into microparticles for drug delivery107. Through photopolymerization, the hydroxyethyl starch derivative hydroxyethyl starch-carbonyloxy ethyl methacrylate (HES-HEMA) could be used to produce microparticles. These microparticles possessed cavities and pores with diameters of 50–100 nm. When loaded with lysozyme, these microparticles exhibited an initial burst release followed by a slower, sustained release of the incorporated protein from the hydrogel. This release mechanism is advantageous for drug delivery applications101.

Chitin, a natural polysaccharide with a wide range of sources, excellent biocompatibility, and biodegradability, has garnered significant attention for its potential applications in biomaterials108,109. Despite many advantageous properties, chitin is almost insoluble in physiological solvents due to its strong intermolecular hydrogen bonds. As a result, carboxymethyl chitin (CMCH) obtained through group modification is preferred for its high solubility110. One example of the use of CMCH is embedding drug-loaded CMCH microparticles (CMCHms) formed in the ATPS into thermosensitive hydroxypropyl chitin (HPCH) hydrogels, which can be directly injected into the desired site in vivo for drug delivery. Under physiological conditions, injected mixtures rapidly formed hydrogels in situ111, enabling the precise and sustained release of drugs. Naproxen and ropivacaine hydrochloride were chosen as model drugs for drug loading in this system and successfully shown to be suitable for minimally invasive local drug delivery102. In another study, two modified hemostatic materials, CMCHm-Ca2+ and CMCHm-PDA, were obtained by loading calcium ions and polymerizing dopamine in situ on CMCHm. Both showed better hemostatic effects than commercial agents and were ideal materials103. Thus, natural polymers and their derivatives have exhibited excellent drug-loading properties with the help of microgels formed from ATPSs.

5.1.1.2. Synthetic macro-molecular monomers

In addition to natural polymers and their derivatives, some synthetic macromolecular monomers are widely used to form microgel particles. Hydrogel microparticles were generated using aqueous two-phase suspension polymerization with PEG-calmodulin-PEG (PEG-CaM-PEG) conjugates. These microparticles could load vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) with high encapsulation efficiencies104. Notably, the hydrogel microparticles could respond to a specific biochemical ligand and thus undergo corresponding ligand-induced volume changes. This phenomenon indicates that hydrogel microparticles show a relatively sensitive release mechanism in response to other physical and chemical stimuli.

In a microgel prepared from norbornene- and thiol-modified four- and eight-armed poly (ethylene glycol) with an average molecular mass of 10 kDa, drugs such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) could achieve high loads. In addition, the drug-carrying microgel could evade alveolar macrophages and continuously release drugs due to its hydrophilic surface and large particle size, which makes it an ideal drug carrier in treating lung diseases such as lung cancer105. Perhaps it will be developed for application to more diseases. Synthetic macromolecules possess more widely varied structures than natural macromolecules. Therefore, synthetic macromolecules can largely compensate for the defects of natural macromolecules for improved functions. For instance, synthetic macromolecules can be used to prevent the interference of the internal immune system and enable specific controlled release of drugs to increase therapeutic efficiency.

5.1.2. Application of ATPS-based biomaterials with complex structures

Some ATPS-based biomaterials, such as hollow microcapsules and multichambered proteinosomes, have complex structures. The personalized and precise delivery of drugs or therapeutic proteins can be achieved by regulating the specific structures and drug loading of carriers, which has significant application prospects in the pharmaceutical industry112. In general, most of these ATPS-based biomaterials exhibit two characteristics: (a) the release of the loaded drugs in response to a stimulus and (b) a multicompartment structure similar to eukaryotic cells. This section will discuss these two characteristics (Fig. 6A, Table 5)21,113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119.

Figure 6.

Application of ATPS-based biomaterials with complex structures. (A) Characteristics of ATPS-based biomaterials with complex structures: multiple independent compartments structure and mechanisms triggering drug release. (B) A series of diagrams illustrating the fabrication, drug loading, ultrasound-triggered actuation, and subsequent payload release of biphasic microcapsules created with mixed molecular weight PEGDA and high molecular weight DEX. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 114. Copyright © 2022 Wiley-VCH. (C) Diagram of preparing alginate microcapsules and confocal images reflecting their structure. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 117. Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society. (D) Depiction of the creation of a triple-compartment system with real-time pH-monitoring capabilities and glucose-responsive, spatiotemporally regulated insulin-PEG-PBA transportation. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 118. Copyright © 2022 Wiley-VCH. (E) The figures illustrate the use of a microfluidic aqueous two-phase system for fabricating multi-aqueous core hydrogel capsules, showcasing the system layout, microfluidic chip structure, capsule generation, and an alginate reaction under acidic conditions. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 119. Copyright © 2020 Wiley-VCH.

Table 5.

Summary of ATPS-based biomaterials with complex structures for drug delivery.

| ATPS-based biomaterial used for drug delivery | Delivered component | The ingredient of the ATPSs | The advantage of the materials obtained | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) CaCO3/PEs composite microcapsules | BSA | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | Showing pH-triggered release ability | 21 |

| (2) (collagen + pectin)/chitosan microcapsule | Anthocyanin cations | Chitosan (30 kDa) + pectin (149.6 kDa) and collagen (<5 kDa) | The release of loaded anthocyanins was pH-dependent, and its delayed release was realized with the increase in pH | 113 |

| (3) PEGDA microcapsules | FITC-DEX | PEGDA (0.575 and 10 kDa) + DEX (450–650 kDa) | Achieving precise drug delivery by real-time adjustment of FUS parameters | 114 |

| (4) PSS/PDDA microcapsules | PDGF-BB molecules and streptavidin | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | The release of loaded molecules can be controlled with the use of external stimuli, such as pH or temperature | 115 |

| (5) PSS/PDDA microcapsules | Trypsin | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | The enzyme was wrapped around the core of the microcapsule and released when pH or osmotic pressure changes | 116 |

| (6) Alginate microcapsules | GOX + HRP | PEG (8 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | GOX and HRP were spatially confined in the shell and core of microcapsules and achieved efficient enzyme cascade reaction | 117 |

| (7) Multicompartmental proteinosomes | GOX + insulin | Polyethylene oxide (PEO) (300 kDa) + DEX (70 kDa) | Achieving pH self-monitoring and spatiotemporal regulation of insulin release | 118 |

| (8) Multi-aqueous core hydrogel capsules | Heterogeneous cells | PEG (20 kDa) + DEX (500 kDa) | Possessing two independent aqueous phase chambers | 119 |

5.1.2.1. Stimulus-triggered release

The release of the drug from the microcapsule is usually accomplished through the rupture of the shell. When the shell is complete, the carried drug is enclosed inside the microcapsule. To achieve the dual spatially and temporally controlled release of drugs, the control of shell rupture of microcapsules is particularly critical. The most used strategy to trigger the release of drugs is to leverage properties of the microenvironment of the target site in vivo, such as acidic pH, tumor-specific enzymes, hypoxia, and oxidative stress. When the carriers reach the target site, the encapsulated drugs are released in response to a specific stimulus, achieving an intelligent release procedure120. Here, some factors regulating the response release of ATPS-based biomaterials are introduced, including pH, ionic strength, ultrasonication, and composite response.

Inspired by the biocatalyzed mineralization of uratolytic bacteria, a CaCO3/PEs composite microcapsule with a calcium carbonate solid shell synthesized in situ was prepared in an ATPS. The microcapsules could carry protein drugs at high loading efficiency (up to 93%) and release the drug when exposed to the gastric environment21. It also suggested that pH-triggered release microcapsules were especially suitable for focal environments with low pH values in the body, such as the stomach. Such microcapsules may also be used in low-pH environments such as tumors121. In a (collagen + pectin)/chitosan microcapsule formed from an ATPS, the anthocyanin cations were well encapsulated into the central pectin due to electrostatic interactions, and the encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity reached 92.58% and 12.34 g/100 g, respectively. The release of the loaded anthocyanins showed pH dependence, and the delayed release of anthocyanins was realized with increasing pH of the phase solution113. In addition, the shell of the previously mentioned microcapsules was developed by the complexation of the pair of oppositely charged PEs. The collapse of the shell could be affected by both pH and ionic strength66. Here, the range of factors affecting encapsulated drug release is broadened, suggesting that ionic strength should also be considered when designing controllable drug carriers. In fact, in addition to lower pH, the tumor microenvironment often has higher ROS levels than normal tissues. Inspired by the existing ROS-triggered release strategies, it may be possible to develop similar ROS-triggered release ATPS-based delivery systems, which would take full advantage of the tumor microenvironment, attenuate oxidative stress damage caused by high ROS to surrounding tissues, and promote drug release122.

Ultrasound features non-invasiveness and high tissue penetration, thus suitable for treating deep-seated tumors in vivo123. To take advantage of this property, a poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) microcapsule triggered to release by focused ultrasound (FUS) was created (Fig. 6B). By adjusting the parameters of the FUS, the microcapsule could release drugs on demand for days to weeks114. This expands the methods for treating deep subcutaneous tissue. With the help of ultrasound, microcapsules containing drugs can be enriched at the target site and triggered to release drugs, thus achieving precise drug delivery.

Microcapsules with multimechanism-driven release often show more significant drug-loading advantages in sensitivity and accuracy. A biologically friendly polyelectrolyte microcapsule (PEMC) was fabricated by the interfacial complexation of oppositely charged PEs, including polycations of poly (diallyl dimethylammonium chloride) (PDDA) and polyanions of polystyrene sodium sulfate (PSS). Platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB) molecules and streptavidin were encapsulated as model drugs and maintained good activity115. Silica nanoparticles (SiO2NPs) were incorporated to improve the mechanical stability and permeability of PEMC shells. Additionally, external stimuli such as pH and osmotic pressure could induce changes in the permeability of PEMCs, enabling control of the release of encapsulated biomolecules. Using trypsin molecules as a model, the researchers confirmed that PEMCs had efficient encapsulation ability and could release trypsin without compromising its catalytic activity116.

In addition, among the transformable nanoparticles that have attracted much attention recently, nanoparticles with shell structures can change from a large to a small size through stimulus-triggered degradation of the shell124. The size transformation of the nanoparticles is extremely important for promoting multiple delivery cascades, which will help to improve delivery efficiency and achieve better anticancer effects. Interestingly, the size transformation of these nanoparticles is often also mediated by pH changes and enzymes125. Thus, it is possible to develop ATPS-based biomaterials integrating the two mechanisms, a promising research field with the potential to make the entire drug delivery process from transport to release more intelligent.

5.1.2.2. Multiple independent compartments

Natural compartments in cells allow reactions to proceed in an orderly and efficient manner126. ATPS-based biomaterials with complex structures often have multicompartment structures. These structures enable ATPS-based biomaterials to exhibit the same regulatory mechanism as cells, making the controlled release of drugs more intelligent and accurate. A microcapsule was constructed as a combination of two natural compartments (including a core and a shell), both of which possessed availability and enabled the delivery of multiple drugs127. As shown in Fig. 6C, dual-compartment alginate microcapsules were formed using the ATPS to separately confine two different bioactive molecules, glucose oxidase (GOX) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP), in the shell and core of the microcapsules due to the partitioning effect of ATPSs. Simultaneously, these microcapsules were proved to have a highly efficient enzymatic cascade, indicating their potential for the controlled sequential release of multiple drugs117.

In addition to microcapsules, with the help of ATPSs, multicompartment structures with spatially entrapped and intact biomacromolecules can also be formed, which seems to be a kind of biomimetic for eukaryotic cells. This feature will release the loaded drug more naturally and dynamically in a controlled manner128. In a delicate heterogeneous proteinosome-based multicompartment system, the pH of the multicompartment proteinosome changed according to different glucose concentrations (1 and 10 mg/mL) in the environment. This change leads to control of the release of Ins-PEG-PBA through different pathways and achieves the spatiotemporally controlled release of insulin. In addition, as shown in Fig. 6D, a pH indicator, both rhodamine B and fluorescein-labeled BSA (BSA-FITC/RBITC), was incorporated into the system to achieve a pH self-monitoring function118. In another study, a multi-aqueous core hydrogel capsule was successfully prepared using a flow-focusing microfluidic device. Notably, the system could contain two independent aqueous phase chambers and has been shown to achieve separate encapsulation of heterogeneous cells (Fig. 6E)119. This expands the preparation method of multichamber systems and provides ideas for designing multidrug cotransporters and intelligent drug delivery programs. In conclusion, the multicompartment structure of microcapsules or more complex ATPS-based biomaterials is conducive to realizing highly regulated intelligent drug delivery similar to eukaryotic cells, which is promising for future research on drug delivery materials.

5.2. Cell delivery with ATPS-based biomaterials

In addition to the delivery of drugs and other bioactive substance components, cell delivery is becoming an important function of ATPS-based delivery systems. An appropriate cell delivery system can provide the cell with a semipermeable microenvironment, which will help to release continuous secretions while protecting cells from host clearance or preventing their activity from being affected129. Studies have shown that hydrogel particles can encapsulate and deliver cells130, and much research has focused on disease therapy based on hydrogel-mediated cell delivery131. Due to the characteristics of nonorganic solvent composition and high biocompatibility similar to that of hydrogels, ATPS-based biomaterials may also be a promising tool for cell delivery in vivo. This will aid in the treatment of cancer or organ and tissue regeneration (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Cancer treatment and organ regeneration based on cell delivery in vivo. (A) Cancer treatment: (i) Multiple chemokines released from tumor tissue activate the relevant receptors on MSCs, attracting MSCs to migrate toward the tumor tissue. (ii) After the chemotactic effect, MSCs with genetic modification express the corresponding cytotoxic proteins, thus inhibiting cancer cell proliferation or inducing apoptosis. (B) Organ regeneration: (i) MSCs regulate cells in injured kidney tissue through the paracrine effect. (ii) Regulated renal cells can complete kidney repair and regeneration.

5.2.1. Cancer treatment

Stem cells such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) often exhibit tumor-homing abilities due to chemotaxis, which pursue cytokines produced by tumor cells132. Notably, if stem cells are transformed into tumor-targeting drug carriers, they can reach tumor lesions through cell homing. The homing cells can inhibit tumor growth by secreting cytotoxic proteins or cytokines133,134. The most critical part of this application is cell modification, loading, and transportation. Here, we mainly discuss the loading and transportation of cells by ATPS-based biomaterials.

NIH/3T3 cells were loaded, delivered, and released by a crescent-shaped PEGDA particle containing a cavity formed by the ATPS by modifying the cell adhesion peptide in the cavity. In this case, the cells showed good viability (up to 93%)86. Calcium alginate particles were obtained by the classical all-aqueous electrospray approach. After adjusting the appropriate osmotic pressure, HEK293 cells were successfully encapsulated and maintained good cell viability for 24 and 72 h. Here, ATPSs have high biocompatibility in the absence of an organic phase, and the ability of ATPS-based biomaterials to load cells is also demonstrated. These indicate that this cell carrier possesses extraordinary advantages in future cancer treatment. With the recent development of cell and molecular biology, the application of cell membranes (CMs) to modify nanomaterials has become a hot topic in biomimetic technology135. Using cancer CMs (CCMs) to modify the nanomaterial can confer excellent biocompatibility and low immunogenicity. In addition, the modification of CCMs can allow the nanomaterials to perform homologous targeting to cancer cells and immune system evasion136. Based on recent research, modifying ATPS-based biomaterials with engineered cancer cell membranes may be a feasible way to strengthen the tumor-targeting specificity and further enhance their antitumor ability.

5.2.2. Organ and tissue regeneration

Compared with the skin and stomach, some organs like the kidney have limited regenerative capacity137. These organs cannot regenerate completely from serious injury, resulting in loss of function, leading to more severe disease and even death. A treatment method that could make these tissues and organs regenerate would be highly desirable138. The regeneration of organs and tissue by implanting cells in the body is a research topic of intense interest. 3D spherical cell transplantation is suitable for almost all human systems, demonstrating the great potential of this therapy38. Injection of MSCs has been shown to have the ability to regenerate the kidney. MSCs triggered various signaling pathways in a paracrine manner to stimulate renal cell repair and regeneration. In addition, exogenous islet cell cluster transplantation is also used for type 1 diabetes139. All of these results illustrate the potential of transporting cells into the human body for tissue and organ repair and regeneration. However, injected cells rarely reach the site of tissue damage and quickly disappear from the injection site140,141. Therefore, an effective delivery system is necessary to facilitate cell concentration and function at the target site. Based on the outstanding cell loading capacity of ATPS-based biomaterials, we believe that ATPS-based biomaterials will play an essential role in tissue regeneration in vivo.

Intraoperative bioprinting is an emerging method for tissue repair and regeneration. In situ cell printing on wounds could be achieved using a two-phase aqueous emulsion bio-ink based on gelatin methacryloyl. The hydrogel generated was conducive to cell survival, proliferation, and diffusion, which is suitable for wound recovery142. Here, research on cell therapy for skin wounds has achieved initial results. Moreover, ATPSs were capable of helping treat skin wounds by simulating cells with an extracellular matrix143. In such a cell–matrix simulation system, the ratio of substances such as enzymes and collagen fibers could be artificially regulated and thus applied to different scenarios144. However, ATPSs still have many untapped potential and challenges in other organizational applications. For instance, utilizing neuronal cell reuptake to deliver ATPSs into neurons and promote neuronal repair or using ATPSs to heal brain tissue is of interest, but transferring the entire system across the blood‒brain barrier is a challenge. It is believed that with the improvement of ATPSs and ATPS-based biomaterial transportation capacity, more tissues and organs can be regenerated with the help of these cell-loading ATPS-based biomaterials.

5.3. Drug delivery combined with ATPSs

In addition to the direct use of ATPS-based biomaterials, some applications incorporating ATPSs are also under investigation. These applications often do not directly use ATPS-based biomaterials but exploit the characteristics of ATPSs. ATPSs can be combined with other drug delivery systems to enrich drugs at specific stages and achieve efficient and safe drug delivery.

With the ability of ATPSs to enrich substances, many drug-loading particles can be produced and show the extraordinary encapsulation effect. Microscaffolds are typically characterized by their porous structure, which can provide a high protein loading capacity. Additionally, when the pores of the particles are sealed, a reservoir for proteins can be formed, allowing sustained release of the loaded protein145. However, existing methods of loading proteins into pores are not ideal146. For instance, α-amylase was encapsulated into porous microscaffolds by exploiting the partitioning properties of an aqueous two-phase system (PEG/Sulfate). This method was demonstrated to achieve encapsulation with a high loading amount of 9.67 ± 6.28% (w/w)147. On the other hand, doxorubicin (DOX) was distributed in PEG/lysine ATPS and modified on the surface of SiO2 nanoparticles by exploiting the ability of ATPSs to enrich substances in a specific phase. The resulting DOX-loaded nanoparticles had a high drug loading rate (63.84%), exhibited high biocompatibility and pH-triggered drug release, and were very valuable for drug delivery. In conclusion, ATPSs have demonstrated extraordinary performance in terms of drug encapsulation, and the obtained drug-carrying particles are potential transportation options.

The enrichment characteristics of ATPSs can also improve the safety and efficiency of drug delivery. In a recent study, ATPSs have been used in the field of iontophoresis. For instance, a new device dubbed a hydrogel ionic circuit (HIC) was generated with the help of ATPSs formed from saturated phosphate salt solution and PEG hydrogel matrix. This device allowed the safe application of high current intensities (up to 87 mA/cm, more than 10 times higher than the current method)148 to the eye. HIC could enhance intraocular drug delivery efficiency (approximately 300 times) by reducing side effects caused by high current intensities and minimizing damage to eyes and tissues. This system limited phosphate ion diffusion by phosphate-PEG ATPS, while efficient ion current transmission was guaranteed. This study improved the safety and efficiency of intraocular drug delivery devices and provides a paradigm of combining ATPSs with other drug delivery systems149. As mentioned above, the characteristics of ATPSs have been used to significantly improve the efficacy of many drug delivery systems.

6. Prospective discussion

ATPS-based biomaterials have shown outstanding performance in drug delivery and disease treatment. However, research on ATPS-based biomaterials in the treatment of disease is still insufficient. Because the composition and formation of ATPS-based biomaterials are different from those of traditional o/w emulsion-based biomaterials, their preparation and development are still limited, hindering their further application91. In addition, the composition types of ATPSs are not yet rich enough, and many stable ATPSs have not yet been converted into useable ATPS-based drug carriers. All these issues limit the biomedical applications of ATPSs, and more creative research is still needed to address diverse and specialized application needs150. Delivering RNAs to maximize their therapeutic and diagnostic potency is a recent research hotspot151. The low cytotoxicity and structural similarity to eukaryotic cells of ATPS-based delivery systems may provide unique advantages in RNA delivery, which need to be further explored. Here, we mainly analyze some potential research areas for ATPS-based drug delivery systems, such as rapid diagnosis of diseases, real-time fluorescence imaging, and the clearance of pathogens. If more exploration is completed in these and other fields, ATPS-based delivery systems will undoubtedly provide incredible breakthroughs in disease treatment.

6.1. Rapid diagnosis of diseases

The key to disease treatment is accurate and rapid diagnosis, especially for tumors, infectious diseases, and autoimmune diseases. Only a negligible increase in atypical components can occur during the early stages of these diseases’ in vivo development. The exceptional capacity of ATPSs to enrich biomolecules is applicable here. Enrichment increases the concentration of tumor-targeting markers in the local range, which strengthens the utility of diagnostic reagents152. This ability may facilitate the prevention and treatment of some chronic infectious diseases, such as hepatitis B. Moreover, this property can increase diagnostic precision during the asymptomatic latent period of some viruses, including COVID-19. Another noteworthy aspect is the inherent flexibility of the ATPS volume, which allows the simultaneous integration of multiple detection factors into the system, facilitating the parallel diagnosis of multiple suspected diseases. This optimization of diagnostic efficiency can potentially save treatment time (Fig. 8A).

Figure 8.

Prospective discussion of ATPS-based biomaterials in drug delivery and disease therapy. (A) Rapid sample identification and disease diagnosis can be achieved by adding ATPS-based carriers containing immunoglobulin to exploit the enrichment of the ATPS system. (B) Real-time fluorescence imaging can be achieved in vitro by adding fluorescent markers to ATPS-based carriers. (C) Targeted-modified ATPS-based carriers carrying drugs can achieve vaccine-like functions and clear pathogens.

6.2. Real-time fluorescence imaging

Real-time fluorescence imaging is often necessary when delivering drugs in vivo. For some drugs that need targeted delivery, real-time detection and quantification of drug concentration are required in addition to focusing on where the carrier precisely delivers the drug153. Moreover, angiogenic reactions often occur in many tumors, potentially leading to tumor vasculature confusion and leakage. In cancer treatment, such changes can hinder the efficient delivery of drugs154. Real-time fluorescence imaging can provide feedback on the intensity and range of fluorescence in vivo, making it possible to monitor the drug distribution in the target organ. Thus, the administration rate and plan can be adjusted to achieve the ideal therapeutic effect.

In addition to targeted drug delivery, real-time monitoring should be considered when developing ATPS-based biomaterial drug delivery systems. The most common method is to label drugs with fluorescence22. However, not all drugs are suitable for fluorescent labeling. In fact, ATPS-based biomaterials are often formed from macromolecular polymers. Since a single carrier can carry multiple drugs nonspecifically, it is possible to visualize most drugs in vivo by labeling these macromolecular polymers that form carriers. In addition, it may also be ideal to carry a mixture of the target drug and fluorescent molecule in the carrier. In conclusion, combining ATPS-based biomaterials and real-time fluorescence imaging will be a highly interesting research topic. The types of imaging molecules used and the methods of binding imaging molecules to the carrier both need to be further explored (Fig. 8B).

6.3. Clearance of pathogens

The level of pathogens profoundly affects the healing progress and prognosis of diseases. ATPSs have been investigated extensively as drug or biomaterial carriers for killing tumor cells and pathogenic bacteria. As immunotherapy advances in treatment strategies, ATPSs are gaining increasing recognition for their potential application. ATPSs offer a simple and efficient alternative to the traditional viral particle purification method155. This will aid in developing more effective recombinant virus-like particle vaccines at a lower cost and in a shorter time frame156, effectively containing global epidemics. From a more in-depth perspective, one potential area for future research is whether ATPSs can function as carriers in the composition of immune vaccines. Concerning antimicrobial activity, ATPSs have demonstrated the ability to entrap bacteria in biofilms and restrict their growth157. Another application prospect is the incorporation of molecules that bind to specific proteins on the bacterial surface to improve the antibacterial targeting of ATPSs (Fig. 8C).

7. Conclusions

In summary, we have elucidated the process from fabricating the original ATPSs to their application in disease treatment as a delivery system. First, we briefly introduced the basic properties of ATPSs and the factors influencing their formation to provide a relatively basic understanding of the ATPS and its subsequent transformation and application. The first major problem in applying ATPSs in biomedicine is the formation of all-aqueous droplets. Low interfacial tension makes it challenging to obtain all-aqueous droplets, but approaches such as medium initiation, mechanical disturbance initiation, and electric initiation can address the problem. Furthermore, the initial all-aqueous droplets cannot be defined as biomaterials. However, several techniques are applied to transform primitive ATPS-derived droplets into functional biomaterials—ATPS-based delivery systems. Finally, the potential of ATPSs as a delivery system for disease treatment is also discussed. Here, we introduce the extensive applications and advantages of ATPS-based biomaterials in drug and cell delivery and improve drug delivery efficiency by combining ATPSs with other drug delivery systems. In summary, ATPS-based biomaterials are an emerging drug delivery system with high loading efficiency, low biotoxicity, and an intelligent release program. They show unique advantages in the treatment of diseases, such as tumor therapy, organ and tissue regeneration, and other large-scale diseases. It is believed that with the completion of more creative work, the application of ATPS-based delivery systems will be expanded to a broader field (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

An overview illustrating the emerging delivery systems based on ATPSs and application prospects.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Science Fund Project (Grant number 82001107) and the Applied Basic Research Project of Sichuan province (Grant number 2022NSFSC1345, China). Thanks are given to the Home for Researchers (www.home-for-researchers.com) for drawing the figures.

Author contributions