Abstract

The main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 is an attractive target in anti-COVID-19 therapy for its high conservation and major role in the virus life cycle. The covalent Mpro inhibitor nirmatrelvir (in combination with ritonavir, a pharmacokinetic enhancer) and the non-covalent inhibitor ensitrelvir have shown efficacy in clinical trials and have been approved for therapeutic use. Effective antiviral drugs are needed to fight the pandemic, while non-covalent Mpro inhibitors could be promising alternatives due to their high selectivity and favorable druggability. Numerous non-covalent Mpro inhibitors with desirable properties have been developed based on available crystal structures of Mpro. In this article, we describe medicinal chemistry strategies applied for the discovery and optimization of non-covalent Mpro inhibitors, followed by a general overview and critical analysis of the available information. Prospective viewpoints and insights into current strategies for the development of non-covalent Mpro inhibitors are also discussed.

Key words: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Main protease, Non-covalent inhibitors, Medicinal chemistry strategies

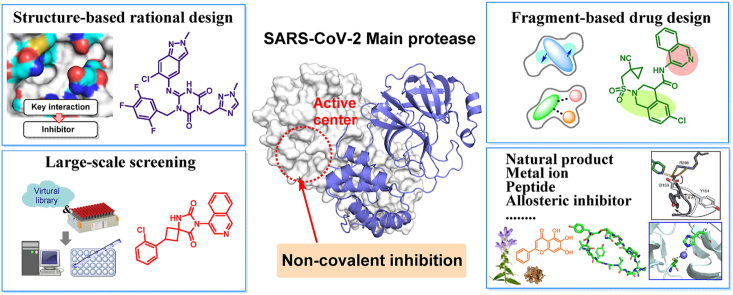

Graphical abstract

This graphical abstract is centered by co–crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, highlighting the theme of “non-covalent inhibitors targeting Mpro”. The surrounding boxes display some representative medicinal chemistry strategies and active compounds concluded in the article.

1. Introduction

In late 2019, an outbreak of a highly infectious disease with pneumonia-like symptoms (fever, dry cough, and fatigue) emerged and quickly deteriorated into a global pandemic and a major threat to global health1. The etiological agent of the disease was the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease was named as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). SARS-CoV-2 is a betacoronavirus that shares 82% genomic sequence identity with SARS-CoV-1, and is the seventh known coronavirus pathogenic to humans2. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were 767 million confirmed infections and 6.94 million deaths globally in early July 20233. Public health policy and massive vaccination are adopted as countermeasures in the battle against COVID-19 pandemic, but variants with increased transmissibility and immune resistance have become dominant among circulating viruses4. The Omicron variant bears dozens of mutations in the viral Spike protein, while threatening the efficacy of the vaccination program due to reduced immunological response, while hampering the effectiveness of antibody-based therapies5,6. Novel SARS-CoV-2 variants with enhanced infectivity have led to additional increases in the COVID-19 transmission rate, along with a swift increase in the number of infections7. With no end of the battle against SARS-CoV-2 in sight, the human public health and world economy profoundly depends on effective controlling COVID-19 and future SARS-CoV-2 emerging variants. Effective direct-acting antivirals, especially oral drugs easily administered, would be a last hurdle towards a robust defense against this threatening disease8. Early efforts produced several repurposed drugs that entered clinical trials, including remdesivir9, molnupiravir10, favipiravir11 and bemnifosbuvir hemisulfate (AT-527)12, but none of them has shown full effectiveness and convincing clinical efficacy13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18.

The viral main protease (Mpro) is one of the most attractive targets in anti-coronavirus therapy due to its high conservation, unique cleavage sequence preference and the absence of similar proteases in the host cell19. Major efforts focused on targeting Mpro have led to the discovery and approval of nirmatrelvir, a reversible covalent inhibitor developed by Pfizer, and administered in combination with ritonavir, a booster of protease inhibitors that acts by inhibiting the cytochrome major P450 isoforms 3A4 and 2D6, therefore helping to maintain high drug levels for longer periods of time18. The combination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (commercialized as Paxlovid®) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency use in December 2021 and its use has been authorized in several countries across the world. At the beginning of 2023, the Chinese National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) conditionally approved the commercialization of therapeutic drugs against COVID-19, namely, SIM041720 and RAY121621, whose chemical structures and antiviral activities are similar to that of nirmatrelvir, of which RAY1216 does not need to be combined with ritonavir.

In addition, Shionogi Inc. announced the emergency approval of ensitrelvir (S-217622) by Japanese authorities, which is the only marketed non-covalent Mpro inhibitor so far22. In the meantime, non-covalent Mpro inhibitors with different scaffolds are being extensively studied and developed, guided by traditional and novel medicinal chemistry strategies.

Recent reviews23, 24, 25 on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors mainly focus on nirmatrelvir and other covalent Mpro inhibitors since this was a productive line of research during the outbreak. However, the identification of effective non-covalent Mpro inhibitors came later and this area was considered to be less productive, despite being equally interesting. Insights into the non-covalent Mpro inhibitors, including strategies, experience, and future directions were rarely summarized. Considering the potential advantages of non-covalent Mpro inhibitors and the increasing number of reports focusing on Mpro as a target, we think that it is important to compile and interpret the available information in order to provide suitable guidelines towards the discovery and development of new drugs for clinical treatment of COVID-19. Herein, we summarize a wide range of promising non-covalent Mpro inhibitors obtained by using different medicinal chemistry strategies. Discussions, insights and future prospects centered on these strategies are also pursued.

2. Mpro: From structural biology to drug targeting

2.1. Mpro plays a key role in the replicative cycle of SARS-CoV-2

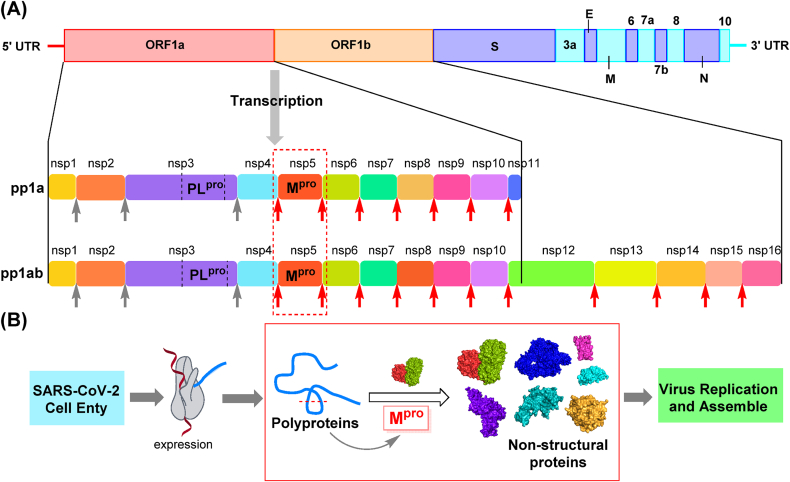

The SARS-CoV-2 genome contains 14 open reading frames (ORFs), among which ORF1a and ORF1b make up more than two-thirds of its full length26. Upon invasion of host cells, the two sequences are translated into two overlapping polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab. The pp1a contains sequences from nsp1 (non-structural protein) to nsp11, while pp1ab contains sequences from nsp1 to nsp16 (Fig. 1A)27. The Mpro (nsp5) and papain-like protease (PLpro, a domain of nsp3)28, generated by auto-cleavage29, are responsible for post-translational processing of polyproteins. Mpro is a cysteine protease responsible for the proteolytic cleavage at eleven sites from nsp5 to nsp16, specifically acting on the sequence LQ↓(S/A/G). The important role of Mpro in virus replication, as shown in Fig. 1B, warrants a lot of attention as a therapeutic target.

Figure 1.

SARS-CoV-2 genomic organization and viral proteins. (A) Sequence of SARS-CoV-2 polyprotein; Mpro cleavage sites are indicated by red arrows, and PLpro cleavage sites are indicated by gray arrows. (B) Diagram highlighting the role of Mpro in the replicative cycle of SARS-CoV-2.

2.2. The structural features and function of Mpro

2.2.1. Catalytic activity and properties

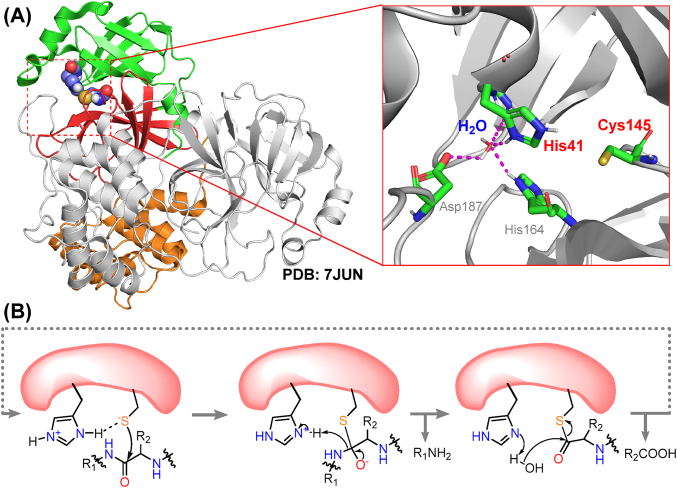

SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is a polypeptide of 306 amino acids with a molecular weight of 33.8 kDa. It belongs to the C30 family of proteolytic enzymes30 and has a similar sequence and superimposable tertiary structure compared with previously identified SARS-CoV-1 Mpro31,32. It contains distinct domains I (residues 8–101) and II (residues 102–184), responsible for forming the catalytic site, and the helical bundle domain III (residues 201–303) that stabilizes the protein dimer (Fig. 2A)33. The active site of Mpro is a catalytic dyad formed by residues His41 and Cys145. Neutron scattering combined with X-ray to reveal a zwitterionic form of the active center, where the thiol group of Cys145 bears a stable negative charge and His41 is doubly protonated34. The proteolytic reaction catalyzed by Mpro initiates with the electrophilic attack of the CH2S– side chain towards the carbonyl group of peptide bond, and is followed by the hydrolysis of the resulting thioester (Fig. 2B)35.

Figure 2.

Structure and catalytic mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. (A) Crystal structure of the Mpro homodimer and close-up view of its catalytic site (PDB ID: 7JUN). Domains I, II and III are represented with green, red and orange cartoons, respectively. All structures hereinafter are visualized by Pymol (pymol.org). (B) Proposed catalytic mechanism of Mpro.

2.2.2. Active site, key residues, and two types of inhibitors

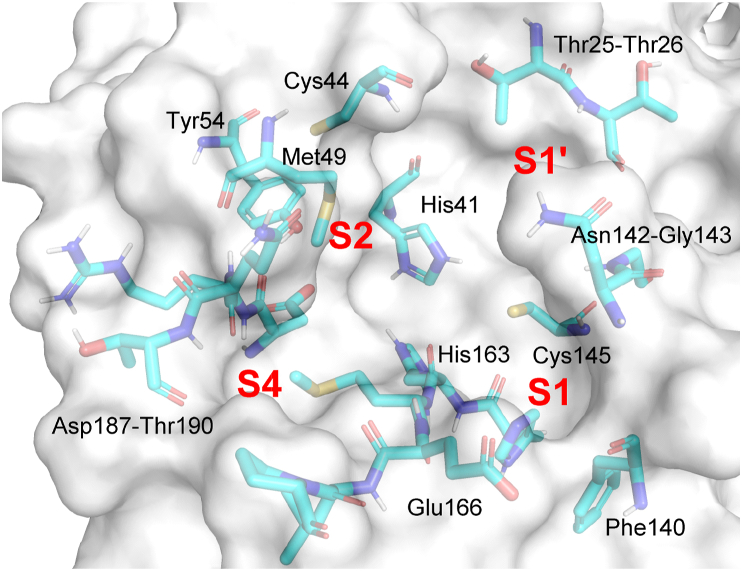

A series of sub-pockets for substrate recognition and binding are located around the catalytic center of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and form the substrate-binding pocket (Fig. 3)36,37. The hydrophilic cavity S1 is centered around the imidazole ring of His163, and surrounded by the side chains of Phe140, Leu141, Asn142 and Glu166. It shows a marked preference for CONH2 in the side-chain of Gln as peptide substrate. S1′ contains the catalytic dyad His41–Cys145, with Thr25, Thr26, Leu27 lining on the farther edge. S2 is defined by His41, Met49, Tyr54, and Met165, and is more likely to form hydrophobic and π–π stacking interactions with ligands38. S4 shares the side chain of Gln189 with S2, and is lined by residues Met165, Leu167, Phe185 and Gln192. In the ligand-free state, S4 is mostly closed37, but the greater flexibility of Gln189 facilitates the accommodation of various hydrophobic groups at this position39,40. Those cavities described above are considered the most important sites for substrate selectivity and Mpro activity, as well as for binding directly-acting protease inhibitors37.

Figure 3.

Residues and sub-pockets at the dimerized SARS-CoV-2 Mpro catalytic site (PDB ID: 7JUN). The second monomer is not shown in the figure.

The prevailing peptide-based covalent Mpro inhibitors bear a peptidic scaffold with highly active warheads. Electrophilic warheads can “trap” the thiol group of Cys145 through an irreversible or reversible covalent bond41,42, thus inactivating the enzyme. The prevailing peptide-based covalent inhibitors bear a peptidic scaffold with highly active warheads. However, their low metabolic instability made most of these compounds only suitable for intravenous administration (e.g., PF-00835231). Most of the peptidomimetic Mpro inhibitors could be also effective inhibitors of human cathepsins43, which play significant roles in cellular metabolism. Meanwhile, the arising drug-resistant Mpro mutants have shown lower sensitivity to nirmatrelvir, and therefore, their spread represents a major threat to the efficacy of nirmatrelvir and related inhibitors44,45.

Non-covalent inhibitors act by competitively binding to the catalytic site through critical hydrogen bonds and non-polar interactions, which may trigger distortions of the sub-pockets and displace essential water molecules, finally blocking the sub-pockets and inhibitor access to the catalytic site25. The most potent non-covalent Mpro inhibitors occupy at least two of these cavities and build up strong interactions with multiple key residues. With reasonable means of development and modification, non-covalent Mpro inhibitors could avoid these problems and reach the same level of antiviral activity as covalent inhibitors. The unique advantages and diverse structural types of non-covalent Mpro inhibitors have led to growing interest in their development.

2.2.3. Dimer-dissociation equilibrium and inactivated state regulates Mpro activity

X-ray structures revealed that SARS-CoV-2 Mpro requires a homodimer to function properly, as observed for homologous Mpro enzymes of many viruses46. The two monomers are arranged in a nearly orthogonal position, stabilized by interface residues of domain III. A salt bridge between Glu290 and Arg4′ acts as the major force controlling dimerization47. In the dimerization state, the side chain of Ser1′ in the other monomer is brought near Glu166, eventually shaping the substrate binding area around S1 and S1′ sub-pockets. Therefore, dimerization is a prerequisite for the normal proteolytic activity of Mpro47,48. Small molecules, and mutations affecting Arg4, Met6, Gln11, Ser139, Glu290, Arg298 may significantly reduce the tendency of Mpro to dimerize and therefore impair proteolytic function49. A recent study also revealed an inactive conformation of Mpro in solution, characterized by a collapsed active site and weaker interactions at the dimer surface50. This conformation of Mpro provides potential targets for inhibitor design.

3. Strategies for the discovery of non-covalent Mpro inhibitors

Unlike covalent peptide-like inhibitors that have been widely studied clinically and even approved for therapeutic use, most of the available non-covalent Mpro inhibitors are at earlier stages of development. Further progress is highly dependent on the effective discovery rate of promising small-molecule leads and the rational modification of existing inhibitors. Published advances in the field result from a variety of medicinal chemistry strategies that are individually discussed in the following sections. Structural evolution, structure–activity relationships (SARs), and mode of interaction (MOI) of some representative compounds are presented all together.

3.1. Virtual screening

3.1.1. Classical virtual screening of diverse libraries

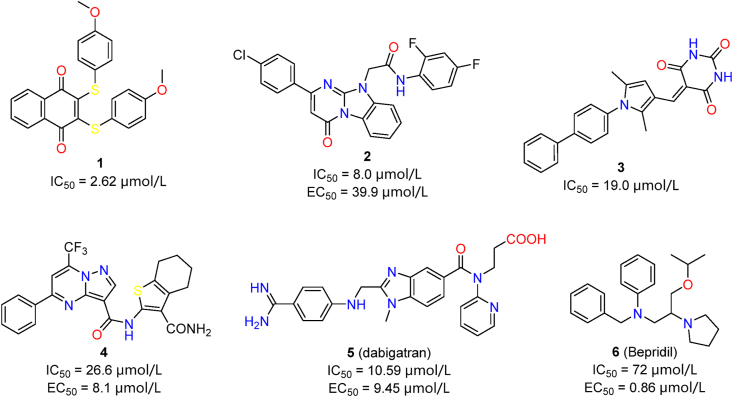

Virtual screening has been one of the most widely practiced strategies in discovering Mpro inhibitors. We classified representative studies by their key features, and discussed their reliability and contributions in a critical perspective. A representative example is the docking-based virtual screening of 688 compounds from a focused library of naphthoquinones51. Rigid docking, flexible docking and enzyme inhibition assay led to the identification of compound 1 (IC50 = 0.40 μmol/L, Fig. 4). Dithiothreitol (DTT) addition and dilution assays confirmed specific and reversible non-covalent Mpro inhibition by compound 1, and clearly distinguished it from other non-specific inhibitors in the same study. Similarly, compounds 2–4 were discovered from commercial libraries, showing modest Mpro inhibitory activities (Fig. 4)52, 53, 54. Apart from the general workflow of virtual screening, these studies also applied feasible and effective measures to increase accuracy and reliability. In the case of 3, a 3D-QSAR (quantitative structure–activity relationship) model was trained by existing Mpro inhibitors, which led to effective hit discovery53. Libraries containing approved small-molecule drugs were explored to identify compounds with acceptable safety profiles and druggability. 5 (dabigatran) and 6 (bepridil) were successively repurposed as potent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors, which were discovered via virtual screening of the approved drugs55,56. The strong inhibitory activities of these two compounds demonstrate the effectiveness of this screening strategy. Repurposed drugs have higher safety and feasibility than those random molecules in compound library, therefore should receive higher attention.

Figure 4.

Verified non-covalent hit compounds from virtual screening targeting Mpro.

3.1.2. Virtual screening combined with structural optimization

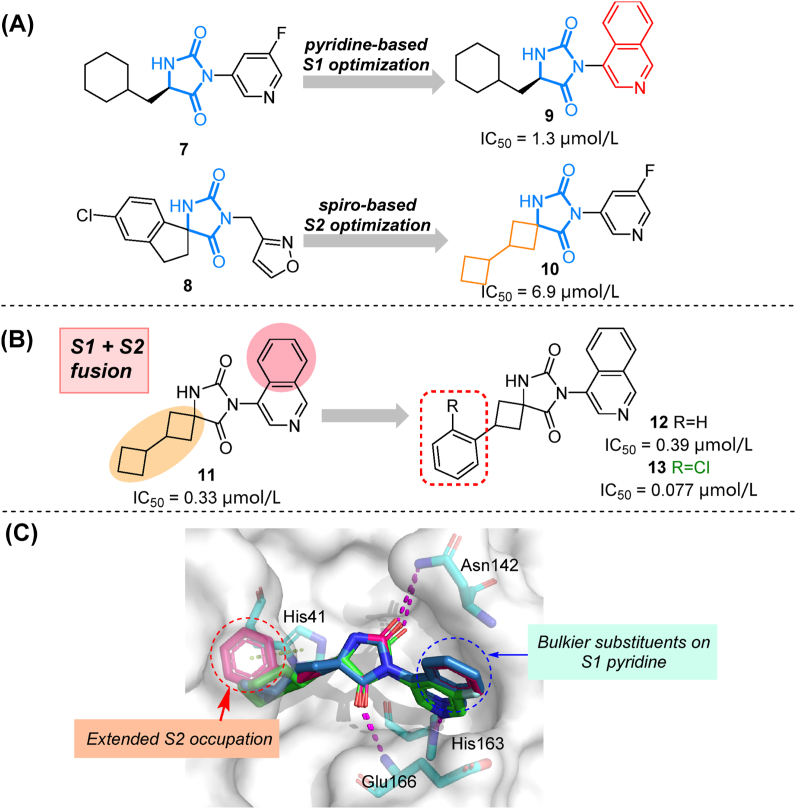

To improve activity and druggability of identified hits, modifications facilitated by virtual screening could be subsequently performed. Two compounds (7 and 8) with an imidazolidine-2,4-dione (hydantoin) scaffold were chosen as hits for further modifications after screening an ultra-large library containing 235 million molecules57. As depicted in co-crystal structures, the carbonyl oxygens from 7 and 8 formed hydrogen bonds with the backbone amido group of Gly143 and Glu166, while 3- and 5-substitutions target S1 and S2 sub-pockets, respectively. Systematic exploration of substituents around the hydantoin core were pursued. Pyridine ring was proved to be optimal as S1 binder as it targeted His163 effectively, while a spiro linker joining lipophilic groups towards the S2 cavity was preferred (Fig. 5A, 9–10). A combination of identified privileged groups led to the design of compound 11 with sub-micromolar inhibitory activity. Moreover, based on its co-crystal structure, the ortho-chlorophenyl group was introduced in the S2 cavity. The resulting compound 13 demonstrated a 5-fold improvement in Mpro inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.077 μmol/L, Fig. 5B), along with strong anti-coronavirus activity (SARS-CoV-2: EC50 = 0.11 μmol/L, SARS-CoV-1: EC50 = 0.39 μmol/L, and MERS-CoV: EC50 = 0.20 μmol/L). Low molecular weight and potent broad-spectrum activity make it an attractive lead compound for further evaluation. Here, efficient computing tools and large libraries play a key role in the rapid identification of hydantoin-based Mpro inhibitors.

Figure 5.

Screening-based modification of hydantoin-based Mpro inhibitors. (A) Structures and activities of hits/compounds (7–10) from two rounds of screening. (B) Structures and activities of compounds 11–13. (C) Co-crystal structures overlay and residue interactions of 7 (green, PDB ID: 7B2U), 11 (blue, PDB ID: 7O46) and 12 (magenta, PDB ID: 7QBB). Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines, π–π stacking are shown in green dashed lines.

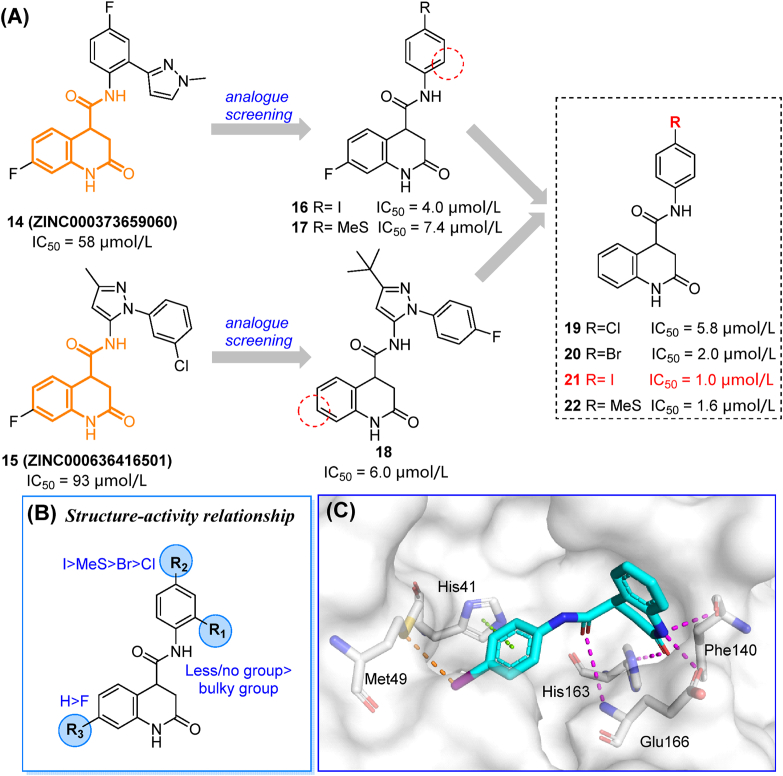

Compounds 14 and 15 were obtained from multipurpose screening against 17 targets related to COVID-19 therapy including Mpro58, and showed over 70% Mpro inhibition at 40 μmol/L59. In the screening of structure-related compounds based on an N-aryl-dihydroquinolinone-4-carboxamide scaffold, 16–22 were identified as potent Mpro inhibitors (Fig. 6A). These compounds showed enhanced enzymatic inhibition activities (IC50 = 1.0–5.8 μmol/L). The preliminary SAR of substituent groups is depicted in Fig. 6B. The co-crystal (PDB ID: 7P2G) structure of compound 21 indicated that the dihydroquinolinone moiety makes multiple H-bonds with key residue His163 of the S1 subsite, while the oxygen of the carboxamide linker reaches Glu166 and Cys145. The iodobenzene moiety occupies the S2 cavity while making π–π stacking and strong halogen bonds with His41 and Met49, respectively (Fig. 6C). Nonetheless, compound 21 only occupied two subsites of the Mpro active center. Further studies should be focused on extending this lead compound into the S1′ and S4 subsites, while assessing antiviral activities in different cell lines and animal models.

Figure 6.

The discovery, optimization, and co-crystal study of dihydroquinolinone derivatives. (A) Starting hits and their screening-based optimization. (B) Preliminary SAR of the screened compounds. (C) Co-crystal structure of compound 21 and Mpro demonstrating space occupancy and residue interactions (PDB ID: 7P2G). Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines. π–π stacking are shown in green dashed lines. Halogen bonds are shown in orange dashed lines.

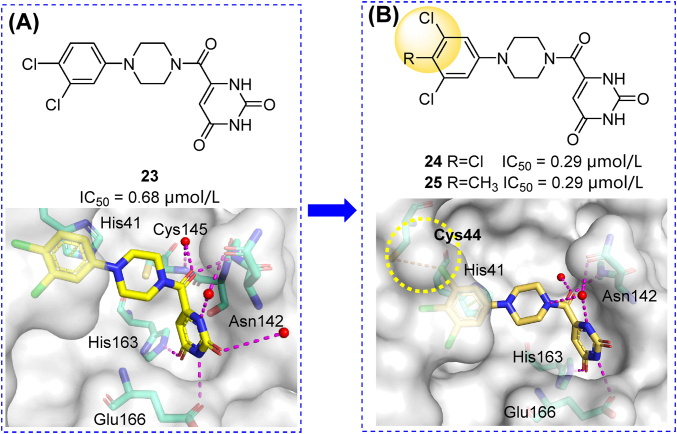

An MCULE library containing 6.5 million compounds was screened using five receptor models and two docking protocols60. Compound 23 (MCULE-5948770040) was identified as the most potent Mpro inhibitor (IC50 = 4.2 μmol/L). The crystal structure of 23 in complex with Mpro revealed its non-covalent binding mode and full occupation of the S1 and S2 cavities (Fig. 7A). Immediately afterward, a series of compounds with the modified S1- and S2- binding groups were synthesized. These efforts resulted in the generation of two compounds (24, 25) with 3,4,5-trisubstituted S2 groups that showed about two-fold increased inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.29 μmol/L, Fig. 7B)61. These piperazine derivatives are valuable lead compounds for further modification (see Section 3.3.4).

Figure 7.

Structures, activities and co-crystal analysis of compounds 23 (A, PDB ID: 7LTJ) and 24 (B, PDB ID: 7RLS). Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines. π–π stacking are shown in green dashed lines.

Structural modifications based on library screenings provide a shortcut to finding potential active analogs of specific hit compounds and a better interpretation of SAR. However, such a practice might be limited by the diversity, property and commercial availability of library compounds.

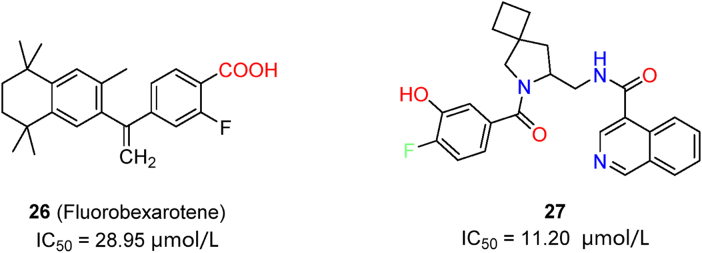

3.1.3. Virtual screening coupled with artificial intelligence and machine learning

Machine learning, based on previous data sets, proved to be more effective and accurate in discovering novel Mpro inhibitors. Complementary QSAR and BABM (biological activity-based modeling) modules can be combined in machine learning assays for the discovery of novel drug candidates62. The resulting activity-based models were trained by public databases. Among the selected compounds, 26 (fluorobexarotene, Fig. 8) exhibited moderate inhibitory activity in enzymatic assays and a cytopathic effect reduction in cell-based assays (HEK293-ACE2 cells). More importantly, this improved method showed 10.4-fold increase of the hit rate. In another effort involving the screening of a library including 40 billion compounds, candidate molecules were processed by a deep docking method driven by artificial-intelligence and pharmacophore model filtering63. Automated strategy and visual inspection were combined to select potent inhibitors (represented by compound 27, Fig. 8) with IC50 values around 10 μmol/L. As predicted by docking results, 27 spans over at least three pockets at the Mpro active center, and it is more suitable for further structural modifications Overall, automated artificial intelligence can be helpful to avoid randomness in docking simulations, while providing more valuable hit compounds for further improvement through modifications.

Figure 8.

Hit compounds discovered with the assistance of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

3.1.4. Lessons from virtual screening campaign

From the examples presented in the previous sections, we conclude that the outcome of virtual screening depends on several factors. Improving the predictability of the docking method is of utmost importance. For instance, considering the adaptability of the Mpro active site, receptor-flexible docking methods could be used to better predict ligand binding pattern64. A compound library with superior quantity and quality, a series of reasonable filters to remove undesired compounds and an evaluation system that better predicts ligand affinity are also indispensable. Experimental measurement of biochemical activity should be conducted, not only for validation, but also for demonstrating the correlation between predicted properties and compound activities65,66. Unfortunately, there are published studies with low-quality compounds and questionable data, which should be handled with caution. Those inhibitors bearing unstable structures or unspecific binding groups should not be considered for further development. The expanded size of virtual libraries may also lead to higher rate of false-positive compounds and fewer bioactive molecules67. In this scenario, future in silico screenings should learn from the past and avoid any conclusions without concrete experimental proof to assure integrity and reliability.

3.2. High-throughput screening

Compared with computational screening, high-throughput screening (HTS) provides reliable results based on experimental data from specific assay systems. HTS was a fruitful strategy for the identification of both covalent and non-covalent Mpro inhibitors68.

3.2.1. Advances in HTS aimed at the identification of Mpro inhibitors

FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) is the most typical assay for Mpro inhibitor screening. A peptidic substrate containing a fluorogenic group connected with quencher by linker sequence can be recognized by Mpro. Cleavage of the peptide linker leads to a detectable shift in the emission wavelength. Thus, enzymatic inhibition could be determined from the intensities of emission at two different wavelengths69. FRET-based assays can be further modified and improved to prevent misidentification of false-positive compounds while increasing assay sensitivity70,71. Analogously, a protein biosensor obtained by linking the fluorescent proteins eCFP (cyan fluorescent protein) and Venus (a yellow fluorescent protein) through the peptide sequence TSAVLQ↓SGFRK, which could be hydrolyzed by Mpro at the cleavage site (marked with the arrow “↓”), have been developed72. The luminescence-based assay73 involves the use of amnioluciferin which is released from a peptide probe by Mpro, and converted to a light signal by luciferase. This novel assay provided accurate measurements of IC50 values for Mpro inhibitors, and is a potential choice for HTS. Moreover, cell-based virus-free HTS assays are also widely used. FlipGFP (green fluorescent protein), cell lysate Protease-Glo luciferase and luciferase complementation assays were also reported as effective methods for the screening of Mpro inhibitors74,75. Cell-based HTS systems are encoded to express Mpro and probe proteins with an Mpro cleavage site. Upon Mpro cleavage, the light signal provided by the experimental system shows detectable changes, which reflect the relative activity of protease. Such systems could be helpful to rule out problematic compounds with high toxicity or low permeability.

3.2.2. Non-covalent Mpro inhibitors identified by HTS

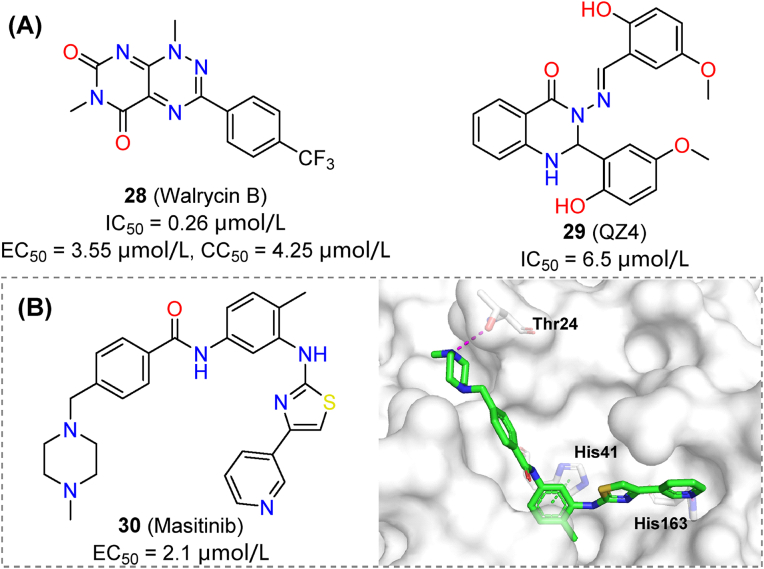

A quantitative HTS over 10,755 compounds was practiced using FRET assays. Among them, compound 28 (walrycin B) demonstrated remarkable inhibitory activity against Mpro (IC50 = 0.26 μmol/L, Fig. 9A), but was cytotoxic to Vero E6 cells (EC50 = 3.55 μmol/L, CC50 = 4.25 μmol/L)76. High toxicity made it useless as a therapeutic agent but could be tackled by rational modifications. Using a GFP cell-based assay, the quinazoline derivative 29 (QZ4, IC50 = 6.5 μmol/L, Fig. 9A) was identified from a small in-house library. The compound showed prominent activity in the GFP assay, similar to that of boceprevir77.

Figure 9.

Non-covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors identified by HTS. (A) Chemical structures and activities of compounds 28 and 29. (B) Chemical structure, activity and crystal structure of 30 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 7TVX).

Cell-based HTS has also been helpful for drug repurposing of non-covalent Mpro inhibitors. Representative compound 30 (masitinib) showed an EC50 of 2.1 μmol/L in an anti-coronavirus screening using HCoV-OC43 as a surrogate, while inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 with an EC50 of 3.2 μmol/L (A549 cells). Further structural studies also confirmed that masitinib was a potential Mpro inhibitor (Fig. 9B)78. Collectively, HTS is a practical and reliable method for identifying non-covalent inhibitors of Mpro. Great improvements in screening methodologies, combined with high-quality libraries are major contributors to these developments.

Novel resources, such as a DNA-encoded library (DEL) were also effectively applied in HTS of Mpro inhibitors. A typical DEL is based on a cocktail of millions to billions of mixed compounds, each of them labeled by specific DNA sequences. Mpro was immobilized on magnetic beads. After co-incubation, active compounds immobilized on beads (solid phase) were separated and decoded to determine their chemical structures. Four promising candidates (31–34) were identified from a DEL containing 49 billion compounds, showing sub-micromolar IC50 values against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (Fig. 10A)79. Compound 33 (WU-04) displayed stronger antiviral activity than nirmatrelvir against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (Caco-2 cell line, 24 nmol/L versus 33 nmol/L, Fig. 10B), which binding mode with Mpro was revealed using crystallographic methods (Fig. 10C). In mice models, twice-a-day oral dosing (300 mg/kg per dose) of 33 reduced viral load in lungs below the detection limit, and an effect on lung inflammation was also observed. DEL screening has a huge advantage in efficacy and compound diversity. Stemmed from “split-and-pool” method of generating DEL libraries, a huge number of serial analogs based on certain scaffolds can be synthesized and screened80, therefore contributing to the optimization of potent hits targeting Mpro.

Figure 10.

Hit compounds from DEL-based Mpro inhibitor screening. (A) Chemical structures and IC50 values of 31–34. Common structures are highlighted in purple/blue. Chiralities of 31 and 34 are unspecified. (B) The antiviral activity towards various strains, in vivo half-life and oral bioavailability of 33. (C) Residue interactions of 33 revealed by its co-crystal structure with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 7EN8). Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines. π–π stacking are shown in green dashed lines. Halogen bonds are shown in orange dashed lines. Amnio–π interactions are shown in red dashed lines.

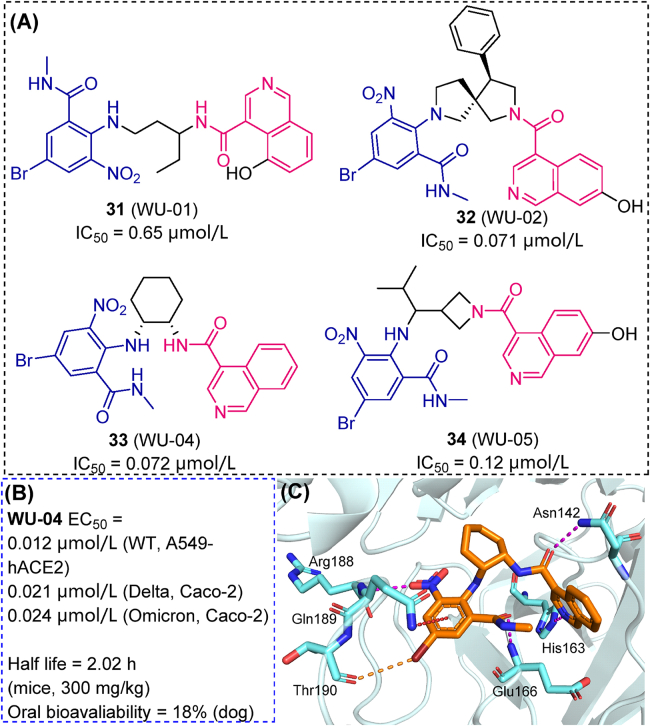

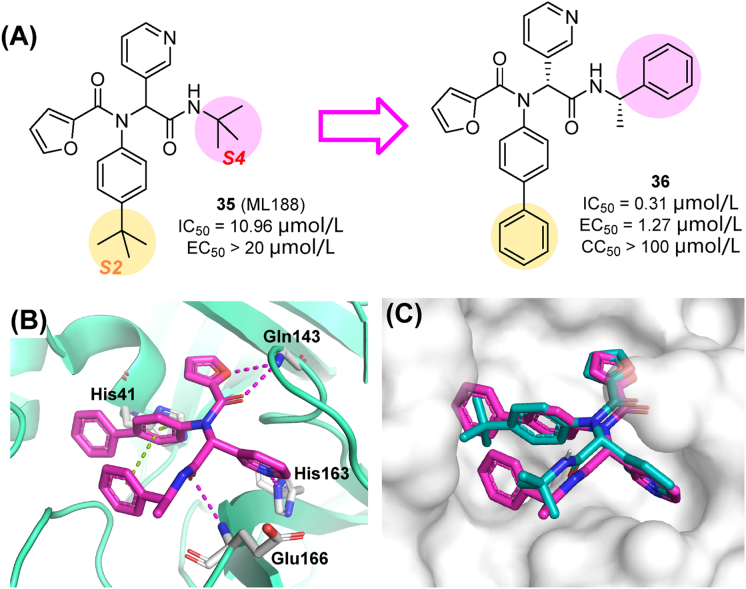

3.3. Target-based rational drug design

3.3.1. Molecules generated through the Ugi reaction

The first crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro was released in early 2020, opening the door to structure-based drug design69. The promising SARS-CoV-1-Mpro non-covalent inhibitor 35 (also known as ML188) was repurposed against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro81. Compound 35 had similar inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (IC50 value of 10.96 μmol/L) than against SARS-CoV-1 Mpro (IC50 = 11.23 μmol/L) (Fig. 11A)82. ML188 derivatives were designed by a step-wise optimization procedure and obtained through the Ugi four-component reaction. SAR studies indicated that the largest substituent that could be accommodated in the S2 sub-pocket was a biphenyl group, while the (S)-α-methylbenzyl moiety was preferred at the S4 subsite. Favorable substitutions at each subsite were combined, leading to compound 36 (IC50 = 0.31 μmol/L) with a 54-fold improvement in the enzymatic inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro relative to the lead 35. Besides, 36 exhibited potent antiviral activity towards SARS-CoV-2 in cell-based assays (EC50 in Vero E6 cells of 1.27 μmol/L), without significant cytotoxicity (CC50 > 100 μmol/L, Fig. 11A). As a non-covalent inhibitor, 36 was highly selective against human proteases. As revealed by the co-crystal structure of Mpro and 36 (PDB ID: 7KX5, Fig. 11B), the inhibitor reached the lipophilic surface of the S2 and S4 sites through its bulkier phenyl groups and showed an extended occupation, while conserving key H-bond interactions83.

Figure 11.

(A) Structures and activities of 35 and 36. (B) Mpro binding mode revealed by X-ray crystallography. 36 (magenta)/35 (cyan). Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines. π–π stacking are shown in green dashed lines (PDB ID: 7KX5).

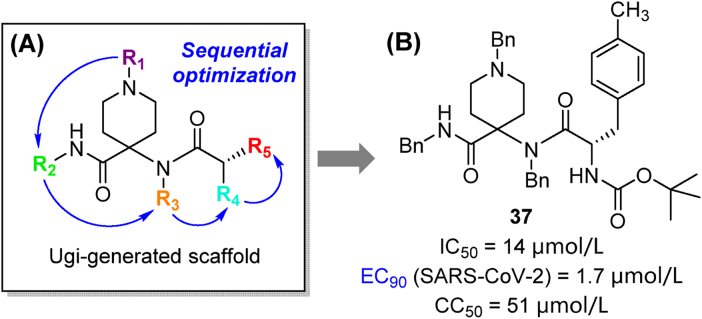

The Ugi four-component reaction was also applied to the introduction of substituents at five sites of the 1,4,4-trisubstituted piperidine scaffold (Fig. 12A)84. Multiple series of compounds were pre-screened in antiviral assays with HCoV-229E, and potent candidates were evaluated for their anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity. Notably, compound 37 (Fig. 12B) displayed an EC90 value towards SARS-CoV-2 as low as 1.7 μmol/L. Multi-component reaction has been proved as a powerful chemical tool for the fast library-building and derivatization of different series of Mpro inhibitors.

Figure 12.

Discovery of the trisubstituted piperidine analogs. (A) Rational design based on Ugi-generated scaffold; (B) Structure and activity of representative compound 37.

3.3.2. Triaryl pyridiones

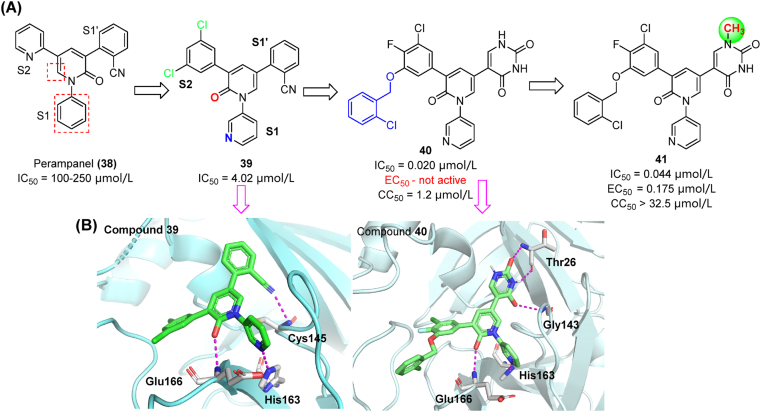

Perampanel (38), an FDA-approved antiepileptic drug, showed relatively poor inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (IC50 = 100–250 μmol/L), while showing non-covalent binding85. Its stereostructure is characterized by a clover-like pattern made by three aromatic rings around a pyridone core that facilitates binding into the S1/S1′/S2 subsites. A significant improvement of activity was achieved by switching the pyridine group to S1 subsite and adding chlorine atoms to the S2 phenyl ring (see compound 39 in Fig. 13A). Further modifications were conducted to investigate the uncharted chemical space in S4 by introducing alkyl, benzyl and heterocycle groups86,87. The resulting compound 40 was one of the most potent derivatives (IC50 = 0.020 μmol/L) in enzymatic assays. Co-crystal structures of Mpro in complex with perampanel analogues indicated that hydrophobic interactions in S4 could substantially affect their inhibitory activity (Fig. 13B)88. However, 40 has no detectable antiviral activity in cell-based assays, presumably due to the poor cell permeability of uracil groups. As a countermeasure, the S1′ uracil was N-methylated (41, Fig. 13A), leading to a remarkable improvement of antiviral activity in vitro (EC50 = 0.175 μmol/L). It should be noted that compound 41 has high aqueous solubility and low cytotoxicity in Vero E6 cells (CC50 > 32.5 μmol/L)87.

Figure 13.

Discovery and co-crystal studies of perampanel derivatives. (A) Optimization process starting from compound 38. (B) Co-crystal structure of compounds 39 (left) and 40 (right) with Mpro illustrating H-bond interactions (magenta) and spatial occupancy (PDB ID: 7L10).

3.3.3. Benzotriazoles

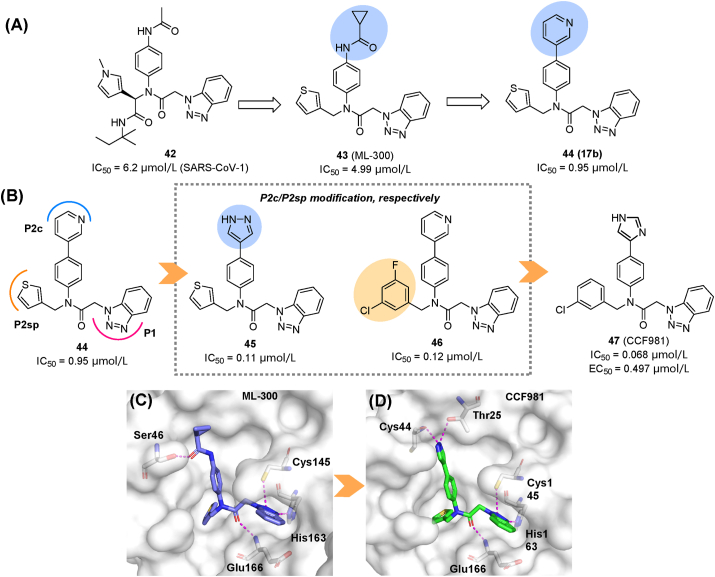

In an early effort aiming to discover non-covalent SARS-CoV-1 Mpro inhibitors, lead 42 was optimized to obtain 43 (ML300, IC50 = 4.99 μmol/L) and 44 (17b, IC50 = 0.95 μmol/L, Fig. 14A)89. The two compounds extended to the S2c channel, a hydrophilic region next to canonical S2 pocket (S2sp)90. In an effort to target SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, the thiophene (in S2c) and pyridine-3-yl (in S2sp) moieties of 44 were modified (Fig. 14B), while the benzotriazole-1-yl acetamide in S1 was conserved. This led to compounds 45 and 46 that increased their inhibitory activity about 8 times in comparison with 44. The pyrazole group, acting as hydrogen bond donor at the S2c site, produced a significant improvement in the inhibitory activity. Then, the optimal groups in S2c/S2sp subsites were combined to obtain compound 47 (CCF981), that showed the strongest antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in Vero E6 cells (IC50 = 0.068 μmol/L, EC50 = 0.497 μmol/L), comparable to that of remdesivir (EC50 = 0.34 μmol/L). The comparison of the co-crystal structures of 47 and 43 revealed closer contacts with the S2c cavity through dual H-bonds with Cys44 and Thr25 in compound 47 (Fig. 14C and D), proving that H-bond donors are preferred in the S2c cavity. Unfortunately, the unchanged benzotriazole group was easily metabolized, requiring modifications to improve its druggability.

Figure 14.

Modifications of benzotriazole derivatives. All the IC50 values presented are for SARS-CoV-2. (A) Prior modifications led to compounds 43 and 44. (B) Rational design based on 44. (C, D) The co-crystal structure of 43 (C, PDB ID: 7LME) and 47 (D, PDB ID: 7LMD) in complex with Mpro. Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines.

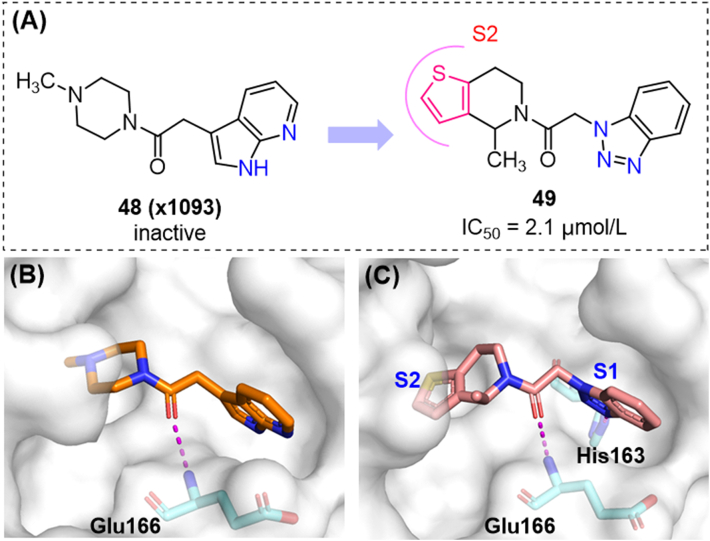

Fragment 48, as a weak binder of Mpro, was identified from a fragment screening by X-ray crystallography91, and chosen for hit-to-lead optimization57. This compound showed low affinity in SPR (surface plasmon resonance) assays (KD > 200 μmol/L) and no enzymatic inhibition at 50 μmol/L, but showed a good occupation of the S1 and S2 subsites. The aromatic heterocycles in the S1 cavity and the amide group directly interacting with Glu166 were conserved. More than 10 billion analogs of 48 were virtually screened and validated. The results suggested that the benzotriazole ring was preferred in the S1 subpocket. For the S2 subsite, the introduction of thiophene-fused piperidine led to the potent hit compound 49 (Fig. 15), which unexpectedly showed a strong similarity with compound 42. In further optimization of 49, the privileged groups in S2c could be fused onto the piperidine ring, obtaining promising compounds with novel scaffolds.

Figure 15.

Optimization of fragment 48. (A) Structures and activities of compounds 48, 49; (B) (C) Co-crystal structures of 48/49 with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 5RF7 and 7NBT).

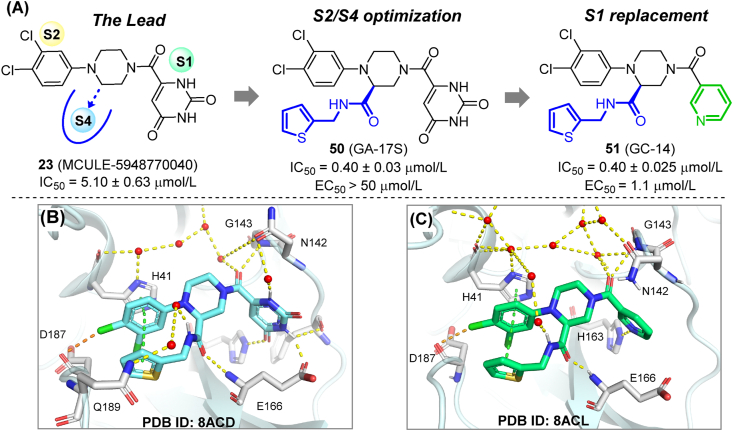

3.3.4. 1,2,4-Trisubstituted piperazines

The hit compound 23 (MCULE-5948770040), was taken as a lead compound in the rational design of highly potent and selective Mpro inhibitors60,92. Considering that 23 only occupied two subsites in the Mpro active center, a side arm was added to the piperazine scaffold to occupy S4 subsite while reaching the key residue Glu166 for additional interaction. The resulting compound 50 (GA-17S) showed a 10-fold increase in Mpro inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.4 μmol/L). However, 50 failed to show significant anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity in cell-based assays. This unexpected situation is assumed to be a consequence of the poor membrane permeability of the uracil group in S1, as discussed in section 3.3.2. Further medicinal chemistry efforts were pursued to replace the uridine moiety. Compound 51 (GC-14) with a nicotinoyl group retained potent enzymatic inhibition, while showing remarkably enhanced antiviral activity in cell-based assays (IC50 = 0.4 μmol/L, EC50 = 1.1 μmol/L, Vero E6 cells). Compound 51 has no significant cytotoxicity at 100 μmol/L, and no inhibitory activity against host proteases at 50 μmol/L (Fig. 16A). According to crystallographic studies, the newly introduced carboxamide groups in both compounds formed new hydrogen bonds with Glu166, while the terminal (thiophen-2-yl)-methyl group occupied the hydrophobic S4 subpocket. Thiophene/phenyl rings in S4/S2, together with the imidazole side-chain of His41 formed a sandwich-like stacking complex, which positioned the inhibitor in a favorable conformation, therefore increasing its affinity for the targeted protease (Fig. 16B and C). As the study highlighted, the occupation of multiple subpockets and effective interaction with key residues are critical issues to consider while developing novel Mpro inhibitors.

Figure 16.

Rational design and co-crystal study of trisubstituted piperazine Mpro inhibitors. (A) Structure and activity of 50 and 51. (B) Co-crystal structure of 50 with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 8ACD). (C) Co-crystal structure of 51 with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 8ACL). Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines. π–π stacking are shown in green dashed lines. Halogen bonds are shown in orange dashed lines.

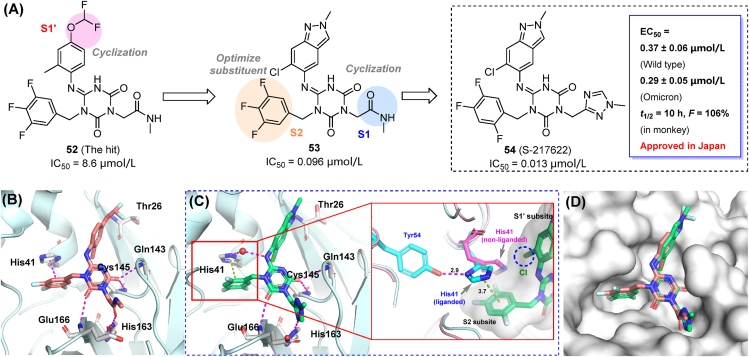

3.3.5. S-217622 (ensitrelvir)

Ensitrelvir (S-217622) was identified as a non-covalent inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (IC50 = 0.013 μmol/L), and a promising oral drug candidate by Shionogi Pharmaceutical Research Center93,94. The hit compound (52) was identified from an in-house compound library, and then modified through a structure-based drug design strategy, targeting pockets S1′, S1 and S2 of Mpro in a stepwise manner. Cyclization of S1/S1′-interacting groups and rearrangement of fluorine atoms in the S2-binding moiety enhanced target affinity, leading to compound 53 and the drug candidate S-217622 (54). S-217622 displayed potent antiviral activity ex vivo against wild-type SARS-CoV-2 (EC50 = 0.37 μmol/L) and several clinical variants (EC50 = 0.29–0.50 μmol/L, Fig. 17A), as well as the Omicron subvariants BA.4 and BA.5. Favorable pharmacokinetic profiles in monkeys were also observed for the selected compound (CL = 0.29 mL/min/kg; t1/2 = 10.0 h; F = 106%). In comparison with nirmatrelvir, S-217622 showed increased antiviral potency in mice95 and hamsters96, and ensured a 100% post-infection survival rate over 14 days (0% in those not receiving the compound)95. Inhibitory activity against host-cell proteases was not observed, indicating the high target specificity of the candidate. Ensitrelvir was approved in Japan after the completion of phase IIa and IIb clinical trials in February 2022, becoming the first marketed non-covalent Mpro inhibitor97. A recent report has demonstrated that ensitrelvir treatment leads to a rapid reduction of SARS-CoV-2 viral loads while ameliorating the symptoms of COVID-1998.

Figure 17.

Design and development of ensitrelvir (54, S-217622). (A) Structural optimization and representative compounds in the development of ensitrelvir. (B) Co-crystal structure of compound 52 (hit) with Mpro. (C) Co-crystal structure of ensitrelvir with Mpro and close-up view showing the conformational change of His41. (D) Binding pose comparison of compounds 52 and 54. Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines. π–π stacking are shown in green dashed lines.

Co-crystal structures of Mpro in complex with the hit compound 52 (Fig. 17B) and S-217622 (Fig. 17C) have been determined. The optimized S-217622 retained an identical binding pose to that shown by compound 52, and occupied the S1, S2 and S1′ sub-pockets (Fig. 17D). The 2,4,5-trifluorobenzylic substituent fits to the hydrophobic S2 sub-pocket, stacked with imidazole ring of His41, while the 1,2,4-triazole moiety formed a hydrogen bond with His163 in the S1 subsite. The indazole moiety occupied the S1′ sub-pocket and enabled the formation of a hydrogen bond with the backbone of Thr26. Yet another appealing fact is that the bulky 6-chlorine atom pushed against His41 side chain, leading to a flip of the imidazole ring. This displacement is stabilized by an additional H-bond with His41 and Tyr54, which was not observed in the apo-Mpro structure (Fig. 17C). The flip leads to a reduced S2 accommodation space, but renders a close distance between the imidazole ring and 1,2,4-triflourophenyl moiety, thereby facilitating the formation of π–π stacking interactions. Moreover, multiple hydrogen bonds were built among the heterocyclic scaffold involving residues Glu166, Gly143, and Cys145.

3.4. Fragment-based screening and optimization

Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) is a strategy that emerged in recent decades. It starts with the identification of a variety of fragments, i.e., weak binders of a specific target with lower molecular weight and fewer H-bond donor/acceptors than drug-like molecules. Three key factors are involved in the FBDD process: fragment libraries, screening methods and fragment modification strategies99. FBDD has unique distinctions and superiorities compared to traditional screening and has been a tremendous aid to the discovery and approval of new drugs.

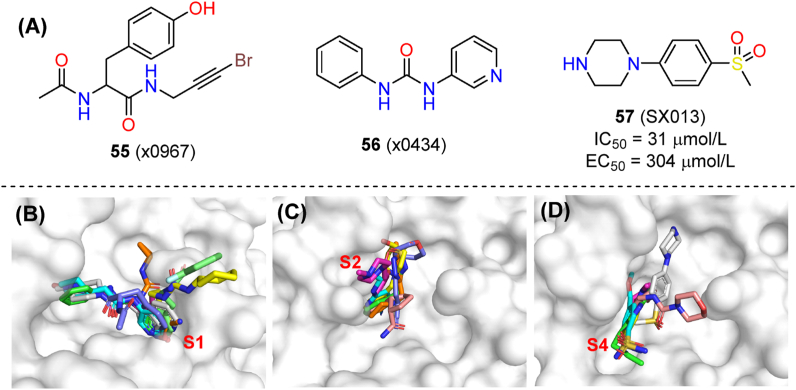

3.4.1. Screening of fragments targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

A massive screen of both covalent and non-covalent fragments targeting Mpro was set out from Diamond Light Source91. A new resolving method named pan-DDA (pan-Dataset Density Analysis) was applied in the co-crystal resolution of fragments, which could interpret signals from the electron density of low-occupying ligands100. As a result, a variety of non-covalent fragments and their binding poses in the protease active site were identified, along with some electrophilic fragments acting non-covalently (x0967, 55, PDB ID: 5RG1).

Alignment analysis showed that fragments spread over the three major sub-pockets of Mpro (Fig. 18B–D), although the preferred binding site of each individual fragment was variable. The S1 cavity was occupied by 56 (x0434, PDB ID: 5R83) and eight other fragments containing the 3-amniopyridinyl moiety, with concurrent interactions with His163, Glu166 and even His41. In the S2 subsite, rigid aromatic rings were absolutely preferred for their π–π stacking with the His41 side chain, and their hydrophobic interaction with Met49. The S4 cavity also favors hydrophobic fragments. These fragments showed a broad chemical space for merging and modification. A follow-up study confirmed 57 (SX013, PDB ID: 5RHD) as a fragment that binds to the Mpro active site, and showing an EC50 value of 304 μmol/L101.

Figure 18.

Fragment-based screening and optimization of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. (A) Chemical structures of 55 (x0967), 56 (x0434) and 57 (SX013) and biological activities of 57. Superpositions of fragments occupying subsites S1, S2 and S4 subsites are shown in panels (B), (C) and (D), respectively.

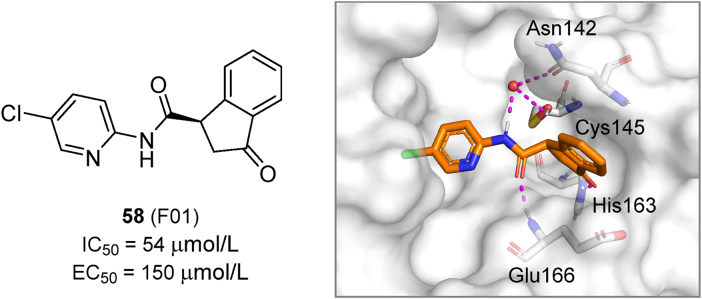

NMR is also a powerful tool for Mpro fragment screening102. In NMR assays, effective binding of fragments leads to a shift of the 2D-correlation signal of Mpro 1H and 15N. This type of studies led to the identification of the top hit 58 (F01), which was then evaluated in enzymatic and cell-based assays and co-crystalized with Mpro (Fig. 19). The compound showed a relatively weak activity with an IC50 value of 54 μmol/L and an EC50 value of 150 μmol/L. Considering that most fragments are too small to present measurable biological activity, 58 could be considered as potentially useful for further development.

Figure 19.

Chemical structure, biological activity and crystal structure of compound 58 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 7P51). Hydrogen bonds are shown as magenta dashed lines.

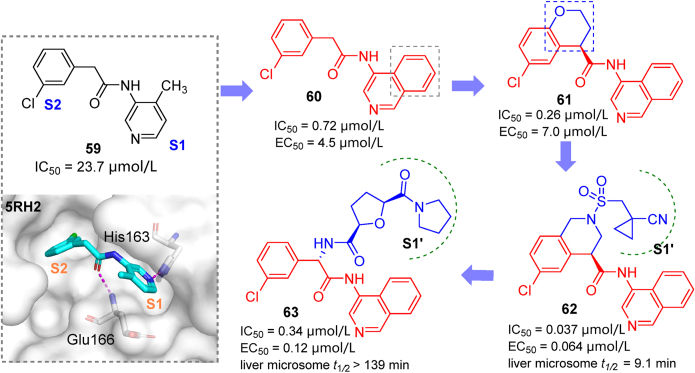

3.4.2. Fragment-to-lead optimization

The COVID Moonshot initiative is a collaborative open-science project that uses high-throughput X-ray fragment screening to identify novel active hits against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The fragment 59 (TRY-UNI-714a760b-6, Fig. 20) was identified and chosen as the starting point for further modification in this initiative, and the results have been published in a preprint server103. For the S1 subsite, replacing pyridine with isoquinoline produced a remarkable increase in potency (60, IC50 = 0.72 μmol/L). The introduction of a chromane ring in S2 and its further replacement by a tetrahydroisoquinoline moiety concomitant with N-functionalization rendered compounds 61 and 62, respectively. Compound 62 was found to be rather potent (IC50 = 0.037 μmol/L; EC50 = 0.064 μmol/L). Furthermore, using hundreds of crystal structures of Mpro bound to different ligands, a computational model was trained to predict and rank novel Mpro inhibitors104. From synthetically-accessible virtual libraries, 40 analogs were identified by the algorithm and synthesized. The most promising compound 63 (IC50 = 0.34 μmol/L, EC50(Vero E6 cells) = 0.12 μmol/L), with an additional S1′ binding group attached to main scaffold, had slightly weaker activity compared to 62, but was characterized with high metabolic stability and low plasma binding. The large accommodation space in the S2/S1′ subsites allowed researchers to conduct next-step derivatizations of aminoisoquinoline analogs assisted by the ranking model described above.

Figure 20.

Derivatives (60–63) identified through lead discovery based on an aminoisoquinoline fragment 59.

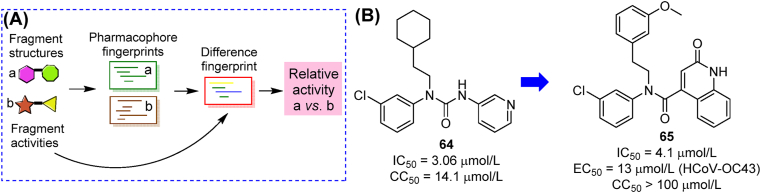

The structures and activities of fragments/hits in COVID-19 moonshot submission (represented by compound 64) were collected to produce a ranking framework (Fig. 21A)105. Instead of predicting accurate values of any compounds, this model could compare the estimated activity of two given compounds with high accuracy. From a library generated by adjusting substituents on training set compounds, three new inhibitors were identified, among which compound 65 showed the most potent activity (Fig. 21B). The ranking model could be a helpful aid in future screening of fragments targeting Mpro.

Figure 21.

Schematic diagram and outcome of the ranking model driven by COVID-19 moonshot fragments. (A) Activity ranking based on pharmacophore fingerprints of two compounds; (B) Structures and activities of top training model compound 64 and predicted compound 65.

The fragment library with co-crystal structures and the online COVID-19 Moonshot project provided great inspiration for the discovery of novel non-covalent Mpro inhibitors. In the future, more active compounds could be identified through the on-line crowdsourcing platform106. FBDD possesses great potential in identifying lead compounds targeting Mpro. Available fragment libraries can be enriched by computer-based screening with minimum cost and in a shorter period107, while the critical evolution from fragments to leads requires greater efforts of medicinal chemists.

3.5. Discovering non-covalent Mpro inhibitors using other strategies

3.5.1. Targeting Mpro by exploiting natural products

Natural compounds had been a rich source of antiviral agents, both in ancient medicine and modern medicinal chemistry. Shikonin (66, Fig. 22A) was identified in HTS studies, inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with an IC50 value of 15.75 μmol/L69. Co-crystal studies confirmed its non-covalent binding mode (Fig. 22B)108. However, the observed cytotoxicity of shikonin precluded further antiviral characterization and development. Based on a traditional Chinese medicine formulae for treating viral infections, baicalein (67) was identified as a potent Mpro inhibitor in enzymatic assay and in phenotypic assay using Vero E6 cells109. Multiple non-covalent interactions between baicalein and Mpro were revealed by crystallographic studies (Fig. 22C).

Figure 22.

(A) Chemical structures and biological activities of the discussed natural products (66–69) targeting Mpro; (B) Co-crystal structure of shikonin and Mpro (PDB ID: 7CA8); (C) Co-crystal structure of baicalein and Mpro (PDB ID: 6M2N). H-bonds are shown in magenta dashed lines. π–π stacking interactions are shown in green dashed lines.

Quercetin (68) was reported to target Mpro with modest affinity110. Considering that selenium-functionalized natural compounds are known to exhibit different biological activities, aryl organoselenium groups were selectively introduced onto the C8 position of the quercetin scaffold. The obtained compound 69 (2d) showed significantly increased inhibitory activity in enzymatic assay (IC50 = 11 μmol/L) and antiviral activity in Vero cells (EC50 = 8 μmol/L, Fig. 22A)111. However, for most natural products identified in bioactivity screening assays, the frequent occurrence of PAINS scaffolds112 and a lack of drug-like properties of those compounds limit their further development towards clinical studies. Improved HTS methods and proper structural modifications are expected to provide suitable solutions to these caveats. In this scenario, the membrane permeability and pharmacokinetic properties of polyphenolic compounds should receive more attention, since prodrug derivatizations are frequently used for modifying phenolic hydroxyl structures.

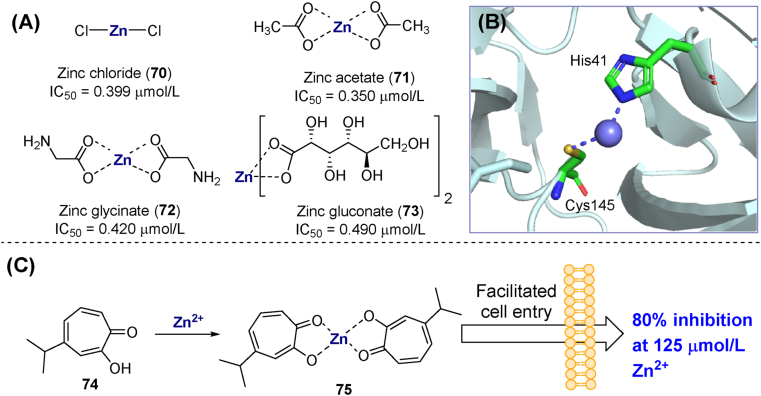

3.5.2. Targeting Mpro by metal ions and complexes

Zinc ions (Zn2+) play critical roles in biochemical reactions and protein structure. Previous research suggested that Zn2+ could inhibit SARS-CoV-1 by targeting Mpro113. Several zinc salts (70–73, Fig. 23A) showed inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 in the sub-micromolar range. Thus, zinc chloride (70) showed 50% and 100% inhibition at concentrations of 0.399 and 6.25 μmol/L, respectively. However, this inhibition was reversible in the presence of high concentrations of substrate or EDTA. Co-crystallization studies confirmed that Zn2+ impairs Mpro function by chelating with the side chains of His41 and Cys145 and interacting at the S1′ subsite (Fig. 23B, PDB ID: 7DK1)114. Based on this finding, the metal ion promoter hinokitol (74, β-thujaplicin) was used to increase the zinc concentration in the cytoplasm. The results showed that 125 μmol/L Zn2+ and 30 μmol/L compound 75 inhibited 80% virus infection in Vero E6 cells without significant toxicity (Fig. 23C)115. Despite these findings, the antiviral potency and safety profile of metal-based Mpro inhibitors are not good enough to turn them into therapeutic agents.

Figure 23.

Metal complexes targeting Mpro. (A) Chemical structures and biological activities of zinc salts/coordinates inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. (B) Crystal structure of zinc ion bound to the Mpro catalytic site (PDB ID: 7DK1). (C) Chemical structures and activity of zinc–hinokitol complexes.

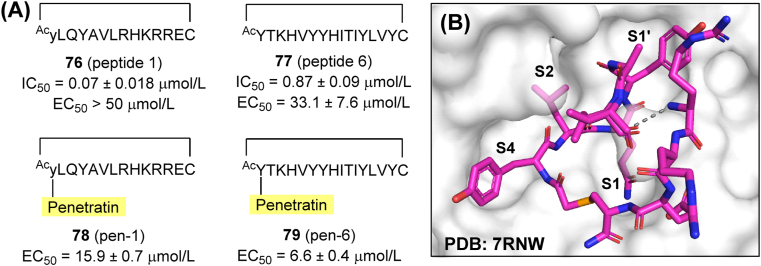

3.5.3. Targeting Mpro by non-covalent binding of peptides

Peptide-like covalent inhibitors play a significant role in antiviral research. However, a few non-covalent cyclic peptide Mpro inhibitors have been reported as well. Screening over a mRNA/cDNA-encoded peptide library using an immobilized Mpro led to the identification of compounds 76 (peptide 1) and 77 (peptide 6) (Fig. 24A). Both of them showed low IC50 values (0.07 and 0.87 μmol/L, respectively) and high selectivity towards host targets, while their concentration was stably maintained in human plasma116. However, in cell-based antiviral assays, the most potent inhibitor (76) had no activity up to a concentration of 50 μmol/L. To address this problem, penetratin, a 16-amino acid peptide promoting cell entry, was conjugated to the C-terminal of 76 and 77 to obtain compounds 78 (pen-1) and 79 (pen-6). The two modified peptides displayed enhanced antiviral activity as intended (Fig. 24A). The co-crystal structure of a selenoether analog of 76 with Mpro revealed its interaction mode with the active site and even the dimer surface (Fig. 24B). Despite showing high potency, previously reported non-covalent peptide Mpro inhibitors may have limited bioavailability and poor metabolic stability.

Figure 24.

Peptides as non-covalent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. (A) Amino acid sequences and biological activities of peptides 76–79. (B) Co-crystal structure of 76 in complex with Mpro (PDB ID: 7RNW). The gray dashed line represents undetermined atoms.

3.5.4. Targeting non-catalytic sites of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

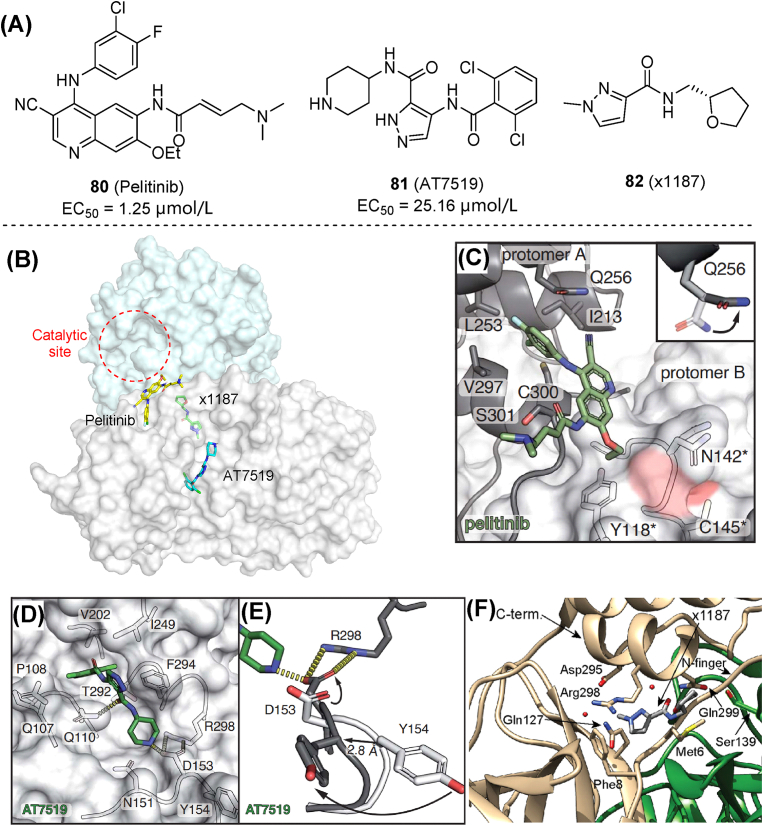

Non-catalytic sites of Mpro refer to potential allosteric sites and binding positions on the dimer surface, which may accommodate small molecules and thus disrupt enzymatic function117. Two allosteric sites of Mpro were revealed by co-crystallization studies with small molecules118. The first site is at the C-terminal dimerization domain and was targeted by five molecules in a screening study. Among them, 80 (pelitinib, Fig. 25A and B) exhibited the most potent antiviral activity (EC50 = 1.25 μmol/L). Pelitinib shows hydrophobic interactions with terminal amino acid residues in a key pocket, whose integrity is critical for enzymatic activity (Fig. 25C). Molecules binding to this site may directly disrupt dimer stability. The second site is a groove between domains II and III, occupied by 81 (AT7519). The amino group from piperidine ring of 81 facilitated the displacement of Asp153, enabling it to form a new salt bridge with the side chain of Arg298 (Fig. 25D and E). As mutations or disruptions of Arg298 were known to destabilize dimerization and affect the active site, this fact explains the inhibition mechanism of 81. Follow-up studies developed a native mass spectrometry assay, confirming that fragment 82 (x1187) interacts with the dimerization interface and promoted Mpro dissociation119. Co-crystal structures of Mpro complexed with 82 showed that this molecule is also approximate to Arg298, but located at a slightly different position compared with 81 (Fig. 25F). The mechanism of action of Mpro allosteric inhibitors needs to be understood, before serving as a guide for designing new compounds.

Figure 25.

Small molecules targeting non-catalytic sites. (A, B) Chemical structures, activities, and binding sites of 80 (pelitinib), 81 (AT7519) and 82 (x1187). (C) Co-crystal structures of pelitinib bound at the Mpro dimer surface (PDB ID: 7AXM). (D) Ligand interactions of 81 with Mpro (PDB ID: 7AGA). (E) Conformational changes of Arg298 and Tyr154 in the 81-bound Mpro structure (black) compared with apo-Mpro (light gray). (F) Co-crystal structure of 82 bound at the Mpro dimer surface (PDB ID: 5RFA)118,119.

There is no doubt that advances in discovering allosteric Mpro inhibitors provide an alternative path for the discovery of non-covalent inhibitors, although more detailed binding analyses and SAR studies are needed to improve their potential capabilities. Moreover, drug design strategies targeting allosteric sites have been widely applied to HIV reverse transcriptases, integrases, and herpes simplex viruses120. Allosteric sites have several advantages over active site binders121, 122, 123: (i) all allosteric inhibitors identified so far have reversible effects, making them safer than many covalent Mpro inhibitors previously discovered124,125; (ii) inhibitors targeting allosteric sites could help to overcome the effects of drug resistance-associated mutations appearing in the active site of the enzyme117. Therefore, the Mpro allosteric sites might be another promising start for the discovery of broad-spectrum anti-coronavirus agents that can act alone or in combination with the other competitive Mpro inhibitors.

How to verify that specific compounds act on allosteric sites rather than the catalytic site also requires special attention. As complements to X-ray crystallography, we believe that changes in the relative amounts of monomeric and dimeric Mpro could also be measured in biochemical assays, such as native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, size exclusion chromatography, or native mass spectrometry.

4. Conclusions, challenges and future directions

Although the search for non-covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors had just started, remarkable achievements and future contributions in the battle against COVID-19 cannot be ignored. To date, it is becoming clearer that non-covalent Mpro inhibitors have a larger space for optimization, and are more likely to develop into potential oral agents with lower clinical risks. Positive outcomes from clinical trials of ensitrelvir (S-217622) and future candidates will also boost the rising interest in this field, which will act as an indispensable counterpart of traditional covalent peptidomimetics. From this perspective, we summarized the development concepts, strategies and methods under the whole course of non-covalent Mpro inhibitors discovery, from primitive hits to pre-clinical evaluations. Various strategies have shown strong interconnections and are valuable references for future developments in this field. We aim to provide a reliable source of information for this emerging field of anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug discovery, aiming to explore prospective non-covalent Mpro inhibitors with diverse structures and prominent antiviral potency comparable with approved therapeutics.

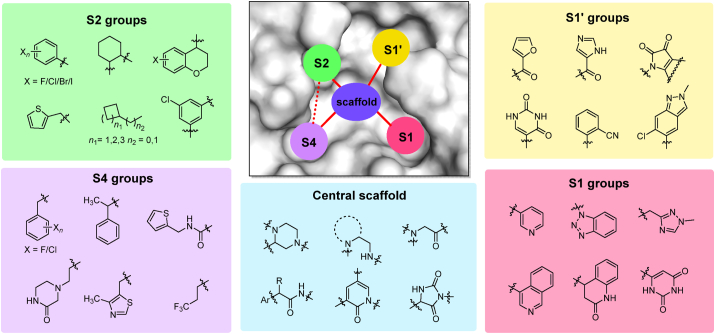

4.1. Progress and challenge in developing non-covalent Mpro inhibitors

Most of the compounds discussed above share similar scaffolds and pharmacophores in each subsite, despite being identified through different strategies. The most representative privileged fragments among existing non-covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors are summarized in Fig. 26. Important features of the inhibitor binding site include the lipophilic pockets S2 and S4, where His41, Gln189 and Glu166 are critical components. while the key amino acids of S1 and S1′ are His163, Gly143, Cys145 and Thr26. These structural constraints facilitate the molecular hybridization strategy in the discovery of non-covalent Mpro inhibitors. The application of advanced computational methods (such as pharmacophore-linked fragment virtual screening, or auto core fragment in silico screening)126,127 in the assembly of pharmacophore fragments at each subsite with optimizable scaffolds may also contribute to the rational design of Mpro inhibitors.

Figure 26.

Overview of key pharmacophores and privileged groups in non-covalent Mpro inhibitors.

Although some seemingly good non-covalent Mpro inhibitors have been reported, there is still a long way ahead for many non-covalent Mpro inhibitors to advance into clinical trials and eventually approval. Several major barriers need to be solved in this effort. First, the inhibitory activity of most of the non-covalent inhibitors is significantly weaker than that of peptide-like covalent inhibitors. Second, there is a need for structurally diverse inhibitors. The scaffolds of current Mpro inhibitors usually derive from previous SARS-CoV-1 inhibitors, thereby requiring further exploration of disparate new scaffolds with better occupation of the Mpro active site. Third, unfavorable DMPK properties and high toxicity is a common weakness of most summarized compounds, which limit the development of Mpro inhibitors86,92. Thus, PK profiles should be considered in structural optimization. Fourth, advanced computer screening technologies have not been effectively combined with experimental practice.

4.2. Improvement of current strategies

On the solid foundation of previous studies, there are several necessary complements and improvements to current strategies. First, multiple parameters of candidate compounds should be considered simultaneously in optimization128. Encouraging progress in the determination of activity profiles has been already attained, but this was not the endpoint of rational optimization. Besides inhibitory activity, compound druggability including solubility, metabolic stability, hERG toxicity and potential side effects should also be addressed.

Second, accurate and efficient screening methods are still needed to provide hit compounds for future modification. Discovery of ensitrelvir highlights the importance of efficient virtual screening and rational follow-up modification. As alternatives to the classical HTS paradigm, miniaturized high-throughput synthesis (including DNA-encoding and click-chemistry-based combinatorial libraries)129, 130, 131 and high-throughput protein crystallography (X-ray crystallographic screening)132, 133, 134 can accelerate the early steps of Mpro-targeted drug discovery.

Third, ligand efficacy should receive further attention in the optimization of Mpro hit compounds. Although extended pocket occupation may lead to higher activity, ligand efficacy may be reduced if bulkier molecules are involved in these developments. In contrast, “magic” groups such as single CH3 or Cl which allow a high gain in potency135,136, are expected to improve ligand efficacy of current lead compounds.

Finally, developing inhibitors targeting non-catalytic sites based on the crystal structure could be successful alternatives. For targeting the dimer interface of Mpro, inhibitors should be able to disrupt critical protein–protein interactions while maintaining high affinity for relatively large structures, as demonstrated for well-characterized inhibitors of HIV-1 capsid137. Rational design and SAR studies of Mpro allosteric inhibitors are required.

4.3. Moving on to the “second phase” in the discovery of Mpro inhibitors

The emerging and transmission of coronavirus over past decades reminded us of the necessity to develop and stock effective antiviral drugs while getting ready to combat next waves of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic or future coronavirus breaks. A turning point in race has been reached. In the past “first phase”, we have accumulated hit compounds, assay systems and crystal structures for non-covalent Mpro inhibitor development. From the beginning of the second phase, effective, oral-available, and Mpro inhibitors active against drug-resistant strains are greatly needed. Among the clinically dominant SARS-CoV-2 strains, resistance towards Mpro inhibitors is rare. However, a broad use of nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir will likely select resistant strains. To prevent future epidemics caused by drug-resistant strains, principles based on the substrate envelope138,139 hypotheses could be applied. From the defined Mpro substrate envelope, researchers could find a balance between high activity and resilience, identifying next-generation drug candidates140, 141, 142. Other prevailing strategies, including macrocyclization, multivalent ligands and targeted protein degradation (PROTAC, molecular glues and hydrophobic tags) also have great potential143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148.

In summary, we hope this comprehensive analysis will provide a novel perspective on drug discovery approaches currently targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Retrospective and critical analysis of established strategies, accompanied by the exploration of novel scaffolds, would effectively boost the identification of potent Mpro inhibitors with an expected clinical impact in the future.

Author contributions

Letian Song and Shenghua Gao contributed equally to this work. Letian Song and Shenghua Gao drafted the manuscript; Bing Ye, Mianling Yang and Yusen Cheng drew figures of the manuscript; Dongwei Kang, Fan Yi, Jin-Peng Sun, Luis Menéndez-Arias and Johan Neyts revised and checked the manuscript. Peng Zhan and Xinyong Liu polished the manuscript and supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from Major Basic Research Project of Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2021ZD17, China), Science Foundation for Outstanding Young Scholars of Shandong Province (ZR2020JQ31, China), Foreign Cultural and Educational Experts Project (GXL20200015001, China), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021A1515110740, China), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M702003). This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain through grant PID2019-104176RB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 awarded to Luis Menéndez-Arias; An institutional grant of the Fundación Ramón Areces (Madrid, Spain) to the CBMSO is also acknowledged. Luis Menéndez-Arias is member of the Global Virus Network.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Luis Menéndez-Arias, Email: lmenendez@cbm.csic.es.

Johan Neyts, Email: johan.neyts@kuleuven.be.

Xinyong Liu, Email: xinyongl@sdu.edu.cn.

Peng Zhan, Email: zhanpeng1982@163.com.

References

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu B., Guo H., Zhou P., Shi Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:141–154. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

- 4.Choi J.Y., Smith D.M. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Yonsei Med J. 2021;62:961–968. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2021.62.11.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameroni E., Bowen J.E., Rosen L.E., Saliba C., Zepeda S.K., Culap K., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. Nature. 2022;602:664–670. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feikin D.R., Higdon M.M., Abu-Raddad L.J., Andrews N., Araos R., Goldberg Y., et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and covid-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399:924–944. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J., Wang R., Gilby N.B., Wei G.W. Omicron variant (B.1.1.529): infectivity, vaccine breakthrough, and antibody resistance. J Chem Inf Model. 2022;62:412–422. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c01451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agost-Beltrán L., de la Hoz-Rodríguez S., Bou-Iserte L., Rodríguez S., Fernández-de-la-Pradilla A., González F.V. Advances in the development of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. Molecules. 2022;27:2523. doi: 10.3390/molecules27082523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian L., Qiang T., Liang C., Ren X., Jia M., Zhang J., et al. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitors: the current landscape and repurposing for the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;213 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian L., Pang Z., Li M., Lou F., An X., Zhu S., et al. Molnupiravir and its antiviral activity against COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2022;4 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.855496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilkington V., Pepperrell T., Hill A. A review of the safety of favipiravir–a potential treatment in the COVID-19 pandemic?. J Virus Erad. 2020;6:45–51. doi: 10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Good S.S., Westover J., Jung K.H., Zhou X.J., Moussa A., La Colla P., et al. AT-527, a double prodrug of a guanosine nucleotide analog, is a potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and a promising oral antiviral for treatment of COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02479-20. 024799-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y., Zhang D., Du G., Du R., Zhao J., Jin Y., et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao S., Huang T., Song L., Xu S., Cheng Y., Cherukupalli S., et al. Medicinal chemistry strategies towards the development of effective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:581–599. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical trials arena. Atea's AT-527 fails to meet primary goal of Phase II Covid-19 trial. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/news/atea-at-527-primary-goal/.

- 16.Eloy P., Le Grand R., Malvy D., Guedj J. Combined treatment of molnupiravir and favipiravir against SARS-CoV-2 infection: one + zero equals two?. EBioMedicine. 2021;74 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashemian S.M.R., Pourhanifeh M.H., Hamblin M.R., Shahrzad M.K., Mirzaei H. RdRp inhibitors and COVID-19: is molnupiravir a good option?. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;146 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drożdżal S., Rosik J., Lechowicz K., Machaj F., Szostak B., Przybyciński J., et al. An update on drugs with therapeutic potential for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) treatment. Drug Resist Updates. 2021;59 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2021.100794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui W., Yang K., Yang H. Recent progress in the drug development targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease as treatment for COVID-19. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.616341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simcere. XIANNUOXIN is put into production and launched today, contributing to China's economic development and the public's health. Available from: http://en.simcere.com/news/detail.aspx?mtt=328..

- 21.Chen X., Wang J., Huang J., Liu Z., Long C., Chen S., et al. 2023. Keto-amide derivative and application thereof in treatment of coronavirus infection. CN 115594734 A. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shionogi. Xocova® (ensitrelvir fumaric acid) tablets 125 mg aapproved in Japan for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 iinfection, under the emergency regulatory approval system. Available from: https://www.shionogi.com/us/en/news/2022/11/xocova-ensitrelvir-fumaric-acid-tablets-125mg-approved-in-japan-for-the-treatment-of-sars-cov-2-infection,-under-the-emergency-regulatory-approval-system.html.

- 23.Pang X., Xu W., Liu Y., Li H., Chen L. The research progress of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors from 2020 to 2022. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;257 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macip G., Garcia-Segura P., Mestres-Truyol J., Saldivar-Espinoza B., Pujadas G., Garcia-Vallvé S. A review of the current landscape of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: have we hit the bullseye yet? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;23:259. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Citarella A., Scala A., Piperno A., Micale N. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro: a potential target for peptidomimetics and small-molecule inhibitors. Biomolecules. 2021;11:607. doi: 10.3390/biom11040607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahimi A., Mirzazadeh A., Tavakolpour S. Genetics and genomics of SARS-CoV-2: a review of the literature with the special focus on genetic diversity and SARS-CoV-2 genome detection. Genomics. 2021;113(1 Pt 2):1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fehr A.R., Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin D., Mukherjee R., Grewe D., Bojkova D., Baek K., Bhattacharya A., et al. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature. 2020;587:657–662. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirtipal N., Bharadwaj S., Kang S.G. From SARS to SARS-CoV-2, insights on structure, pathogenicity and immunity aspects of pandemic human coronaviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;85 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rawlings N.D., Barrett A.J., Thomas P.D., Huang X., Bateman A., Finn R.D. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D624–D632. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bafna K., Cioffi C.L., Krug R.M., Montelione G.T. Structural similarities between SARS-CoV2 3CLpro and other viral proteases suggest potential lead molecules for developing broad spectrum antivirals. Front Chem. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.948553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melo-Filho C.C., Bobrowski T., Martin H.J., Sessions Z., Popov K.I., Moorman N.J., et al. Conserved coronavirus proteins as targets of broad-spectrum antivirals. Antivir Res. 2022;204 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabbah D.A., Hajjo R., Bardaweel S.K., Zhong H.A. An updated review on SARS-CoV-2 main proteinase (Mpro): protein structure and small-molecule inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2021;21:442–460. doi: 10.2174/1568026620666201207095117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kneller D.W., Phillips G., Weiss K.L., Pant S., Zhang Q., O'Neill H.M., et al. Unusual zwitterionic catalytic site of SARS-CoV-2 main protease revealed by neutron crystallography. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:17365–17373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC120.016154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banerjee R., Perera L., Tillekeratne L.M.V. Potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26:804–816. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arya R., Kumari S., Pandey B., Mistry H., Bihani S.C., Das A., et al. Structural insights into SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J Mol Biol. 2021;433 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y., Zhu Y., Liu X., Jin Z., Duan Y., Zhang Q., et al. Structural basis for replicase polyprotein cleavage and substrate specificity of main protease from SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2117142119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sepay N., Saha P.C., Shahzadi Z., Chakraborty A., Halder U.C. A crystallography-based investigation of weak interactions for drug design against COVID-19. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2021;23:7261–7270. doi: 10.1039/d0cp05714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shitrit A., Zaidman D., Kalid O., Bloch I., Doron D., Yarnizky T., et al. Conserved interactions required for inhibition of the main protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Sci Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77794-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Said M.A., Albohy A., Abdelrahman M.A., Ibrahim H.S. Importance of glutamine 189 flexibility in SARS-CoV-2 main protease: lesson learned from in silico virtual screening of ChEMBL database and molecular dynamics. Eur J Pharmaceut Sci. 2021;160 doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2021.105744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ábrányi-Balogh P., Petri L., Imre T., Szijj P., Scarpino A., Hrast M., et al. A road map for prioritizing warheads for cysteine targeting covalent inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;160:94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pillaiyar T., Flury P., Krüger N., Su H., Schäkel L., Barbosa Da Silva E., et al. Small-molecule thioesters as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: enzyme inhibition, structure–activity relationships, antiviral activity, and X-ray structure determination. J Med Chem. 2022;65:9376–9395. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma X.R., Alugubelli Y.R., Ma Y., Vatansever E.C., Scott D.A., Qiao Y., et al. MPI8 is potent against SARS-CoV-2 by inhibiting dually and delectively the SARS-CoV-2 main protease and the host Cathepsin L. ChemMedChem. 2022;17 doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iketani S., Mohri H., Culbertson B., Hong S.J., Duan Y., Luck M.I., et al. Multiple pathways for SARS-CoV-2 resistance to nirmatrelvir. Nature. 2023;613:558–564. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05514-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Oliveira V.M., Ibrahim M.F., Sun X., Hilgenfeld R., Shen J. H172Y mutation perturbs the S1 pocket and nirmatrelvir binding of SARS-CoV-2 main protease through a nonnative hydrogen bond. Research square. 2022 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1915291/v1. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hilgenfeld R. From SARS to MERS: crystallographic studies on coronaviral proteases enable antiviral drug design. FEBS J. 2014;281:4085–4096. doi: 10.1111/febs.12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goyal B., Goyal D. Targeting the dimerization of the main protease of coronaviruses: a potential broad-spectrum therapeutic strategy. ACS Comb Sci. 2020;22:297–305. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.0c00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pekel H., Ilter M., Sensoy O. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: a repurposing study that targets the dimer interface of the protein. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;13:1–16. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1910571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nashed N.T., Aniana A., Ghirlando R., Chiliveri S.C., Louis J.M. Modulation of the monomer-dimer equilibrium and catalytic activity of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by a transition-state analog inhibitor. Commun Biol. 2022;5:160. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03084-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fornasier E., Macchia M.L., Giachin G., Sosic A., Pavan M., Sturlese M., et al. A new inactive conformation of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2022;78(Pt 3):363–378. doi: 10.1107/S2059798322000948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]