Abstract

We developed a set of four community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership tools aimed at supporting community–academic research partnerships in strengthening their research processes, with the ultimate goal of improving research outcomes. The aim of this article is to describe the tools we developed to accomplish this goal: (1) the River of Life Exercise; (2) a Partnership Visioning Exercise; (3) a personalized Partnership Data Report of data from academic and community research partners; and (4) a Promising Practices Guide with aggregated survey data analyses on promising CBPR practices associated with CBPR and health outcomes from two national samples of CBPR projects that completed a series of two online surveys. Relying on Paulo Freire’s philosophy of praxis, or the cycles of collective reflection and action, we developed a set of tools designed to support research teams in holding discussions aimed at strengthening research partnership capacity, aligning research partnership efforts to achieve grant aims, and recalling and operationalizing larger social justice goals. This article describes the theoretical framework and process for tool development and provides preliminary data from small teams representing 25 partnerships who attended face-to-face workshops and provided their perceptions of tool accessibility and intended future use.

Keywords: CBPR tools/toolkit, community–academic research partnerships, community-based participatory research, community-engaged research, public health

Over the past 25 years, community-engaged research (CEnR) and community-based participatory research (CBPR) have prioritized starting from community priorities and strengths, establishing a long-term commitment to building a research relationship with community partners, and applying research results to community action (Israel et al., 2013; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010; Wallerstein et al., 2018). CBPR partnering practices, or the steps research partners take to sustain their collaboration, play a foundational role in the research process by supporting efforts to: establish trust with communities; enhance culture-centeredness of research methods and interventions, and build community and university capacity in research equity outcomes (Khodyakov et al., 2013; Lucero, 2013; Miranda et al., 2013). Notably, CEnR’s focus on equitably engaging with communities has been particularly effective among vulnerable populations and communities of color (Patel et al., 2018; Salinas-Miranda et al., 2017), groups that have historically experienced considerable harm from research. However, the lack of standardized, yet flexible approaches to strengthening partnering can present a major challenge to research partnerships questioning how and whether to expand and sustain a research partnership in the long term.

While CBPR has achieved national recognition as a valuable research framework, the validity and reliability of CBPR processes have yet to be established. Many CBPR projects report impacts on policies, practices, and health equity outcomes (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Israel et al., 2010; Wells et al., 2013), but CBPR partnering practices that influence outcomes are little understood. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017) report, Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity, calls for tools and measures to improve community health outcomes and truly achieve health equity. CBPR offers principles that may support community-centered research, yet many challenges persist in the implementation of CBPR approaches. The literature in this area remains limited. Based on previous research with CBPR partnerships, we identify three important challenges expressly identified by CBPR researchers to the use of CBPR among and within research partnerships, including (a) how to honor partnerships that are responsive to dynamic communities, especially when translating evidence-based interventions into cultural contexts (Youn et al., 2019); (b) how to identify measures acceptable to all partners (Whitesell et al., 2018); and (c) how to increase implementation of promising CBPR practices associated with project outcomes (Goodman et al., 2017).

Research partnerships that center community health and knowledge need measures and transferable tools for assessing partnership effectiveness, answering processrelated questions, promoting respect, overcoming bias and power hierarchies, and aligning key partnership characteristics to achieve equity (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017). Many toolkits on research partnerships have emerged, reflecting the need for effective resources to help support the development and sustainability of community–academic research partnerships. Most are targeted toward a specific area, such as domestic violence (Goodman et al., 2018), cervical cancer screening (Nguyen-Truong et al., 2017) or global social and behavior change communication efforts (Sood et al., 2018). While it may be useful to tailor toolkits for specific research content areas, questions remain around whether general tools can be developed and used by a diversity of partnerships, so that they can benefit from the most promising or best practices among all types of CBPR projects.

This article describes four “collective-reflection” CBPR tools developed by the Engage for Equity (E2) study, an National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded national intervention study, which aimed to support partners in engaging in reflexivity practices to more effectively achieve their outcomes. We developed these tools to develop processes by which research partnerships could explore aspects of their partnership that could be strengthened in order to benefit how the partnership functions, which, we hypothesized, would lead to improved outcomes for the partnerships. The tools were tested through workshop interventions with 25 diverse research partnerships which varied by health issue, population, geographies; and across the continuum of community engagement, ranging from minimal outreach to shared decision making and community-driven projects. E2 has hypothesized that collective-reflection tools can help research partnerships navigate challenges and adopt positive strategies for addressing the complexities of partnering, across power differentials and dynamic community systems, and with the goal of eliminating structural inequities. This article describes the development and implementation of the tools and provides a preliminary evaluation of the usefulness of the tools for strengthening partnerships. The following section describes the research we have conducted on CBPR partnership characteristics and practices that informed the tool development described in the present research study.

Prior Research Informing CBPR Tool Development

The ability to develop and test the feasibility of tools aimed at supporting CBPR partnership processes emerged from two previously funded NIH grants. The goals of these studies were to identify which partnership practices, under differing contexts, would be most useful for contributing to outcomes. Partnering with national CBPR leaders in 2006, we developed a CBPR conceptual model, based on a comprehensive literature review of CBPR studies, which includes four domains: research Contexts (i.e., environments, policies, funding, historic trust/mistrust, and capacity of partners), Partnership Processes (structural, individual, and relational dynamics among partners), Intervention and Research designs that are outputs of shared decision making, and CBPR and Health Outcomes (Kastelic et al., 2018; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010; Wallerstein et al., 2008). The second study included the implementation of online surveys among 200 federally funded partnerships, and detailed case studies with community and academic partners from seven CBPR research study teams, based on constructs from the CBPR model, to assess the variability across the nation of promising partnering processes that contribute to research outcomes (Duran et al., 2019; Lucero et al., 2018; Oetzel et al., 2018).

These previous studies enabled quantitative and qualitative data analyses, which provided the theory, and grounded the theory in specific practices, for the present E2 study (Wallerstein et al., 2020). The CBPR conceptual model (Figure 1) served as the overarching orienting framework for tool development and testing. Thus, we were able to draw from (a) our own evidence of promising partnering practice benchmarks that could serve as motivational comparisons with partners’ own project-level assessments (Duran et al., 2019; Oetzel et al., 2018), (b) our recognition of the collective reflection power-sharing approach from the seven case studies (Wallerstein, Muhammad, et al., 2019), also rooted in previous experience with Paulo Freire–based liberatory education methodologies (Freire, 1970; Rae et al., 2016), and (c) our analysis of the importance of culture-centered community knowledge systems, including community theories about health problem etiologies and the role of cultural epistemologies for solutions (Wallerstein, Oetzel, et al., 2019). We then added implementation science practices to evaluate testing of our tools of their best fit and acceptability by partnerships for adoption and adaptation (Brownson et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Community-based participatory research conceptual model.

Note. CBOs = community-based organizations; CBPR = community-based participatory research; P.I. = principal investigator.

Described first is the workshop intervention, in which facilitators from the Universities of New Mexico and Washington, along with members of the E2 Think Tank (a team of national CBPR academic and community research leaders), led small teams of academic and community partners in their first learning and application of the tools to their own community-engaged research projects. Each tool is then described, following the workshop agenda, with examples to illustrate their capacity to motivate and support collective reflection to strengthen partnering practice.

Method

Workshops

The tools were provided to 25 research partnerships, participating in one of three, 2-day, workshops that took place in the Fall 2017. These 25 partnerships were randomly selected from a sample of 68 partnerships funded in 2015, identified from community-engagement or CBPR-oriented abstracts published in the NIH RePORTer database (Dickson et al., 2020; Wallerstein et al., 2020). To qualify for selection, teams had to have completed two internet surveys, one for the principal investigator and one for all community and academic partners. The E2 survey items were based on refinements from the previous NIH-study of survey results of the 200 partnerships and case study insights (Boursaw et al., 2020). More in-depth details concerning collection and management of team survey data may be found in (Dickson et al., 2020; Wallerstein et al., 2020). Aggregate team responses from the surveys were used to develop a personalized data report (PDR) for each participating team. Over the 2-day period, eight to 10 partnership teams per workshop (with on average two to four members per partnership team) worked separately, guided by an E2 facilitator. The large group (including about 40 attendees total) of all participating research partnerships reconvened at key points to share learnings and progress. Gathering teams together, with multiple team members and multiple research partnerships attending, provided research partnerships a shared space to apply tools to their own projects and partnerships and to reflect on their practices. Team members also participated in a separate community and academic gathering, in recognition of implicit power hierarchies within academic–community partnerships and the need for peers of similar positions to provide each other support. The overall workshop intention was to honor differences in funding sources, level of engagement, and organizational structures; and to provide a mutual opportunity for honest dialogue about facilitators and challenges. By applying reflection tools to their own partnerships and sharing practices with others, we hoped they would identify key learnings to take back to their partnerships. This process was the same for all workshops.

CBPR Tools Description and Purpose

The following section provides a detailed description of each of the four CBPR tools that we developed and used with research teams in the workshops. Each tool represents a qualitative or quantitative strategy for teams to reflect on their past context, present experiences, and desired future. With the qualitative tools, teams created their own expressions of images and visions with butcher paper and markers and crayons during interactive exercises. (See the project website, https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/index.html, for examples of tools, two internet surveys, as well as interview and focus group guides.)

Tool 1: River of Life Reflection.

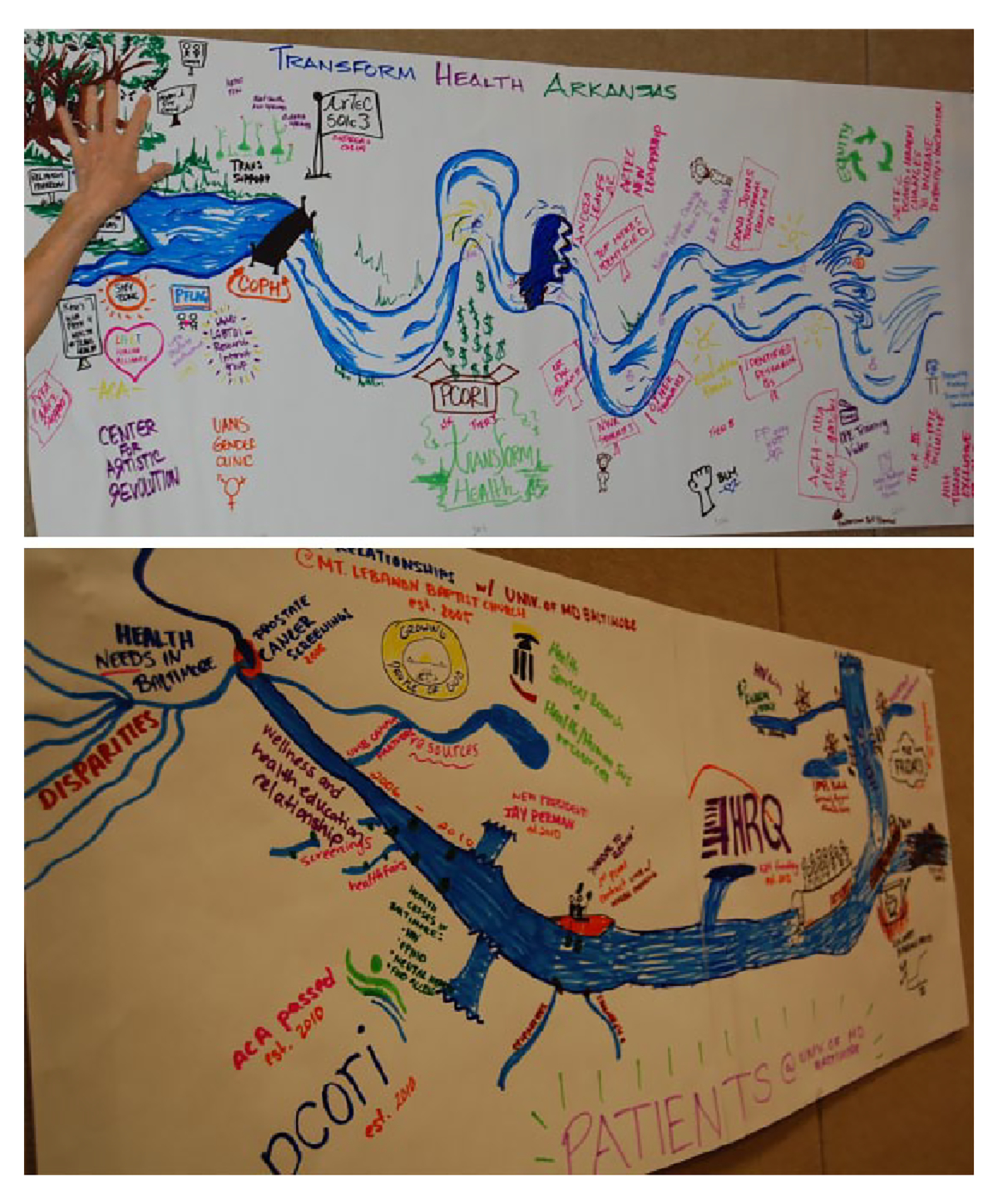

In the workshop, teams first created “Rivers of Life” as a document of their shared journey or historical timeline as a CBPR or community-engaged research project and partnership (Sanchez-Youngman & Wallerstein, 2018). The River of Life allows community-engaged research projects to document their community Context1 and advocacy histories, and to reflect on their collaborative journey, acknowledging major milestones and barriers along the way, and projecting into the future. The metaphor of a river provides a useful focus for research teams to review their origins and their collective progress. As a qualitative tool easily adapted to local contexts, teams created their own images, often incorporating community histories or collaborations before the funding; and using symbols, that is, bridges, dams, or rapids (to express barriers), boats as key partners, or tributaries for new mentors or connections. Figure 2 provides two examples from participating teams, Transform Health Arkansas and PATients-centered Involvement in Evaluating Effectiveness of Treatment. Both teams identify barriers and facilitators to their work, indicating not only team-specific events but also public health and contextual issues that serve to inform their partnership efforts. For example, both teams identify key infusions of resources from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, using water tributaries to indicate an improved “flow” for their respective project (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

River of Life: Examples from Transform Health Arkansas and PATients-centered Involvement in Evaluating Effectiveness of Treatment.

Note. Used with permission.

Tool 2: Visioning With the CBPR Model.

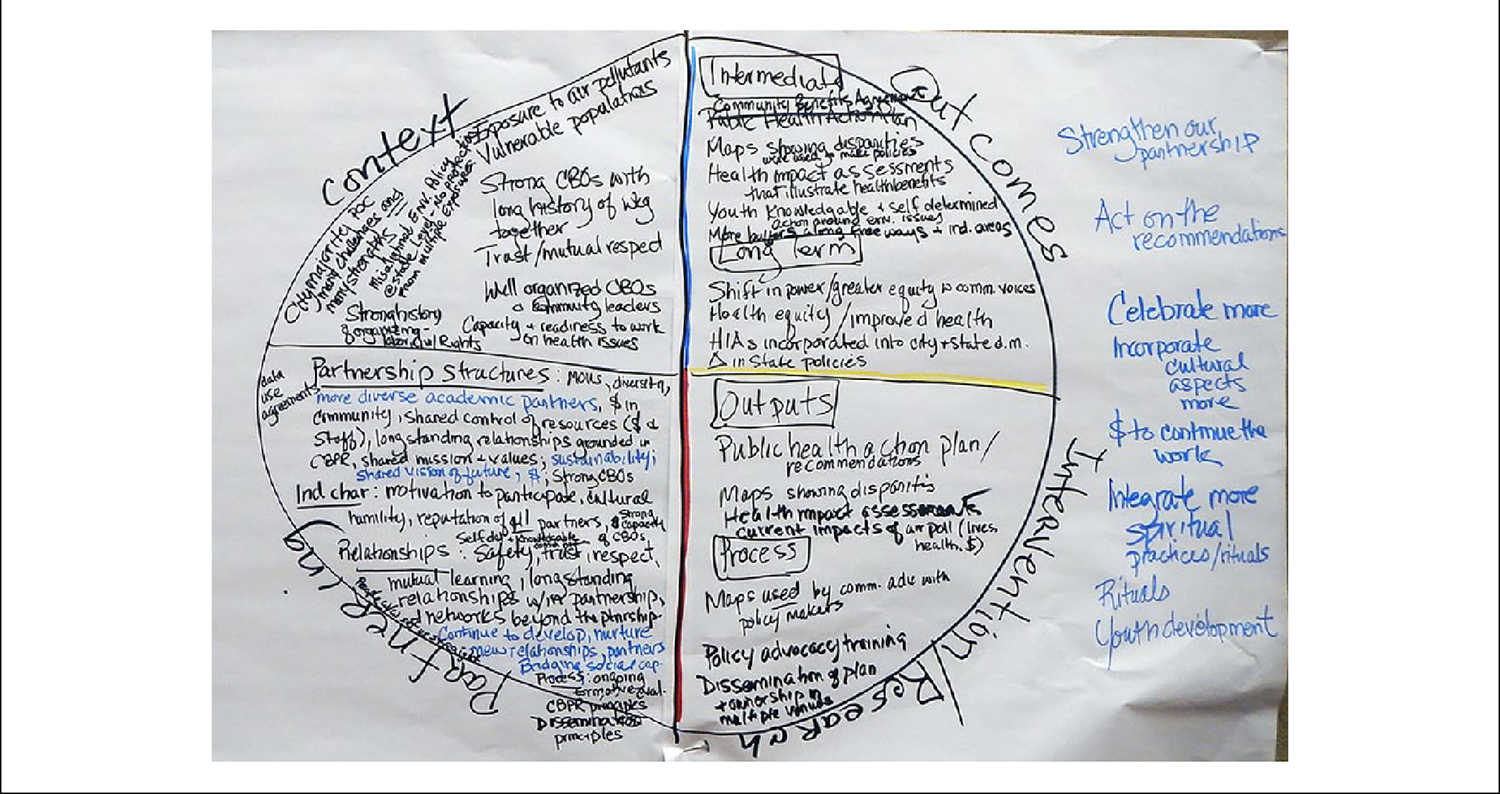

Teams then participated in a visioning exercise, using the frame of the CBPR model to create a vision of where they want to be in the future, and the steps they plan to take to achieve that vision. Each team first brainstormed the Outcomes they would like to achieve, then discussed the facilitators and barriers in their own social and political environments (often drawing on their River). Next, they identified which Partnering Processes from the model they were using well, and which could be strengthened. They then brainstormed how their collaborative practices affected their Research and Intervention actions, reflecting on how to better integrate community or cultural knowledge, or build greater community capacity around research. With this second qualitative tool, teams created their own images using the model as a living document, not restricted to the linear heavy-text approach but one reflecting their own context, practices/values, actions, and desired outcomes. While most used the model as a planning tool, others used it for process evaluation, looking backward and discussing what they could change. For example, Figure 3 provides an example of how the team from the Detroit Community to Action to Promote Healthy Environments adapted the model. While building from each of the four domains, their circular model demonstrates a creative reimaging of how they integrated their own sociocultural context (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Visioning: Example from Detroit community to action to promote healthy environments.

Note. Used with permission.

Tool 3: Partnership Data Report for Reflection.

Partnerships then reviewed their customized PDR, designed as a quantitative evaluation tool for community-academic partnerships to reflect on their CBPR practices. The PDR format is based on responses from the two Internet surveys, based on constructs within the four domains of the CBPR Model, and which were completed by 179 partnerships in late 2016 and Spring 2017 before the workshops took place (Dickson et al., 2020; and Wallerstein et al., 2020). The first internet survey was for the principal investigator who completes a baseline “key informant survey” (KIS), about the facts of the partnership, such as length of time working together, resources, approval processes, and existence of community advisory boards. For the second Internet survey, the community engagement survey (CES), two to six academic and community partners were invited to complete, which covers partner perceptions of the quality of their collaborative processes, the level of community involvement in research, and their outcomes reached or desired for the future (Dickson et al., 2020; Wallerstein et al., 2020). Response rate for the KIS was 53%: and for the CES was 69%.

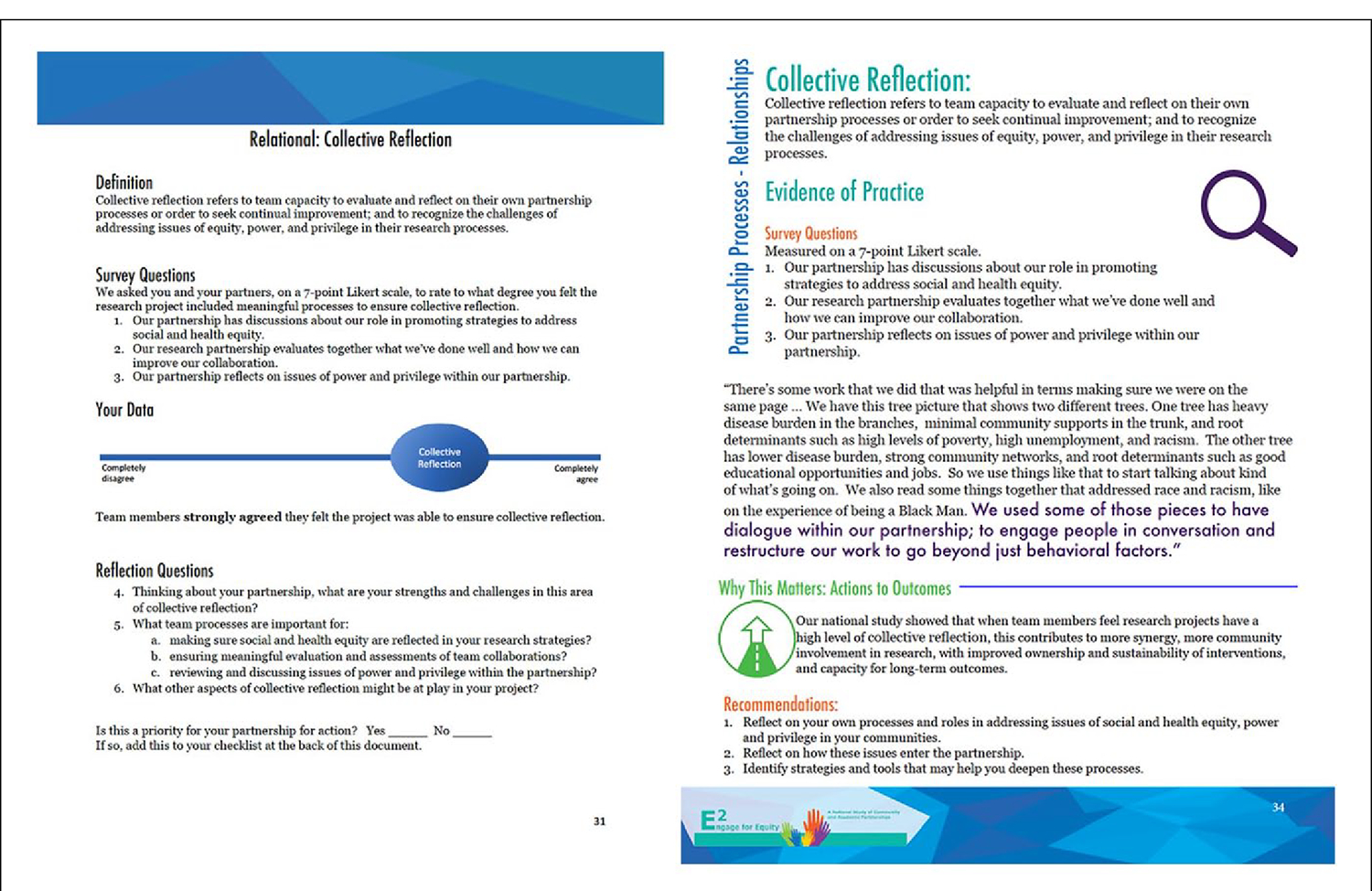

Sixty-eight partnerships, who completed two or more CES surveys, qualified to be selected into the workshop. Each of them then received their own PDR, prior to attending the workshop, which was organized into 20 partnering practices and eight outcomes. Each PDR page contains the definition, survey measures used for assessment, their data averages for each scale, and reflection questions. During the workshop, facilitators guided partner reflection on their data, and asked teams to select up to four priority areas for action. A key reflection question guiding the PDR group dialogue was “What stands out to you about the practices that matter most?” Figure 4 provides a sample page from the PDR focused on Collective Reflection. As demonstrated in the figure, the definition of collective reflection and the actual survey items from the KIS and/or CES are provided as a reference to the team. The average across team survey responses for items is represented as a “thermometer” to reduce the focus on a perceived “score” and to refocus team discussion on the reflection questions, which were the main emphasis during this portion of the workshop. The team then discussed the level of priority they decided this construct required (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Partnership data report and promising practices guide: Example of “collective reflection.”

Tool 4: Promising Practices Guide for Reflection.

The fourth reflection tool was the promising practices guide (PPG), which provided summary data analyzed from 379 federally funded partnerships: 179 collected in the E2 study in 2015, and 200 from the previous study collected in 2009, used to establish national benchmarks for CBPR praxis. These benchmarks are based on analyses of practices that have been shown to be associated with specific partnership outcomes (Duran et al., 2019; Oetzel et al., 2018; Wallerstein, Oetzel et al., 2019). Quotes from the case studies are integrated into the quantitative analyses to deepen meaning of practices; a glossary of terms provides an additional resource. Recommendations in the PPG for each “promising practice” enabled the teams to reflect on where they were with a particular practice (reviewing their PDR) and how they might strengthen this practice with their partnerships at home. Participants also were provided a short introduction to the E2 website (web address provided in the CBPR Tools Description and Purpose section), which provides these tools as well as other resources. Figure 4 also provides an example using the Collective Reflection page for reference. Again, as in the PDR, the definition of Collective Reflection is provided for team reference, along with the survey items for this construct. Qualitative quotes are also provided to illustrate how other teams viewed this construct in the context of their CBPR partnership. Teams also are provided a brief interpretation of national findings, along with suggested recommendations for their discussions.

The application of these tools, guided by Paulo Freire’s dialogue methodology, provided an opportunity for collective reflection on partnership strengths and challenges, motivating partners to seek shared power, identify targets for change, use evidence from previously established CBPR benchmarks of best practices, and identify strategies to reach their goals.

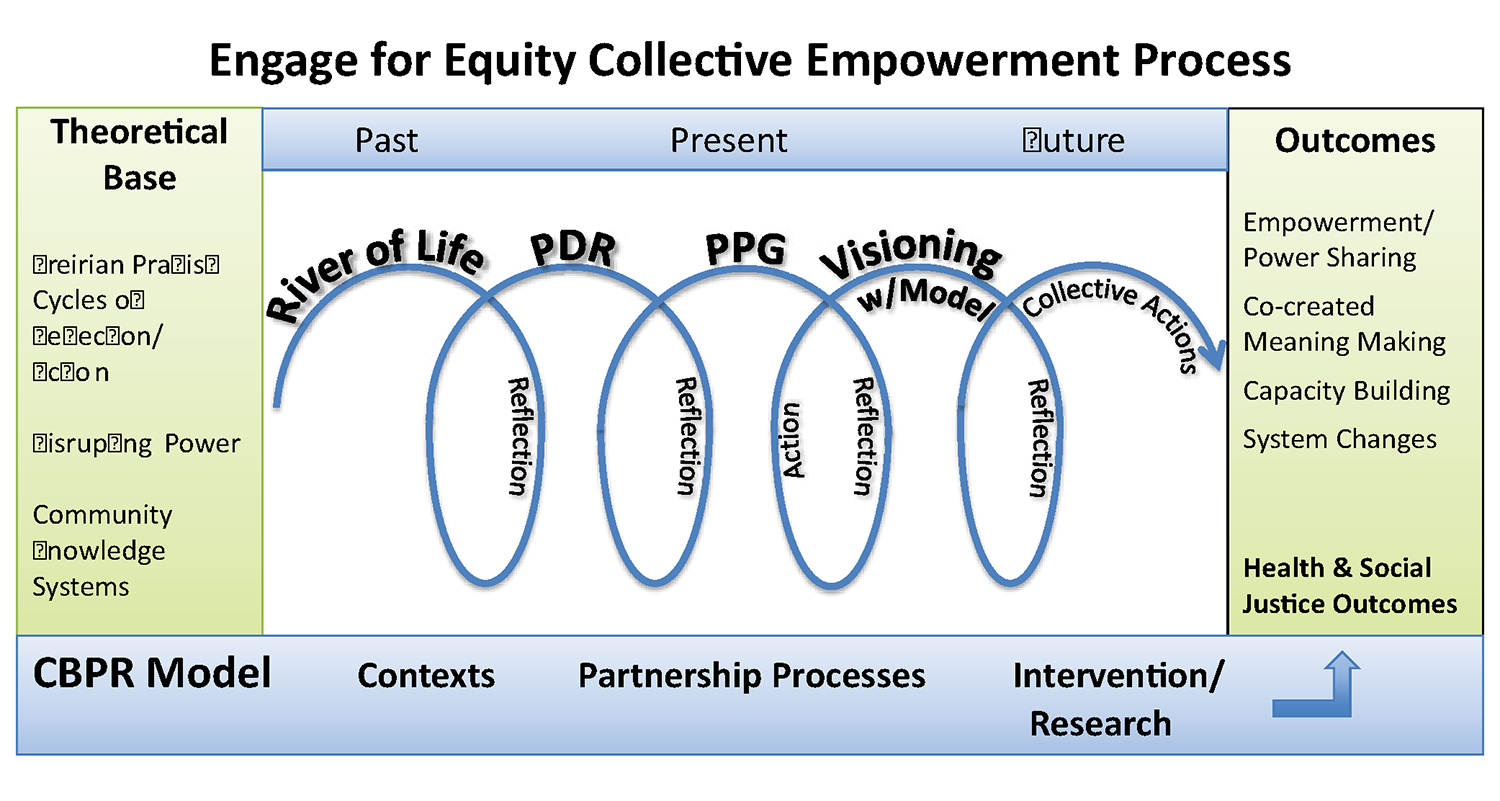

As teams moved through the orientation and use of the tools, they embarked on a “collective empowerment process” journey (see Figure 4). With each tool and relying on community knowledge systems as a basis for their work, teams were supported through successive rounds of reflection and action cycles, in line with the Freirian concept of “praxis.” The driver of disrupting power hierarchies is also central to empowerment, both in seeking shared power for community members within partnerships and in disrupting social and health inequities (Cook et al., 2019; Muhammad et al., 2015; Wallerstein, Muhammad, et al., 2019). The tools provided opportunities for praxis (i.e., ongoing reflection with eventual actions) on power and other issues which support sustained participation, commitment, and trust, necessary for partners as they move forward (see Lucero et al., 2020). The River of Life allowed teams to consider past efforts that influence their present work together. The PDR provided specific insights into their own processes and outcomes, identified in the CBPR model, connecting their past to the present practices. The PPG allowed teams to consider their present practices compared with national benchmarks and to strategize for their future. The Visioning exercise relied on a review of the entire CBPR model to identify future collective actions to pursue goals of health and social justice outcomes (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Theory of change: Collective empowerment process.

Note. PDR = partnership data reports; PPG = promising practices guide; CBPR = community-based participatory research.

To assess the acceptability and fit of the tools, we collected surveys from each of the 25 partnerships participating in the workshops at the conclusion of each workshop through invitation to participate in an online survey. Seventy-one out of 81 workshop participants completed the survey. Of the 71 respondents, we are missing the demographics from the CES for 25 (35%) of them. Of the 46 respondents we do have information for, 22 (48%) identified as community partners and 24 (52%) identified as academic partners.

The Intervention Tools Survey is a 23-item questionnaire that assesses respondents’ perception of the partnership tools, the likelihood that they will use them, and their overall confidence with implementing the tools after returning home. The questionnaire includes 19 Likert-type items and four openended questions. One set of questions was adapted from Rogers’s diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 2003), including items about the relative advantage, compatibility, and complexity of the tools. Additional items asked respondents to rate how likely they would be to implement each tool after the workshop. One open-ended question was asked about each tool: “How do you see yourself using or adapting the [tool] with the rest of your partnership?” Finally, participants were asked whether they felt capable of supporting their partnerships to use the tools, and whether they felt able to meet potential challenges that might arise when using the tools. These last two questions were adapted from the change efficacy framework of Shea et al. (2014). The survey was administered using REDCap software, and analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) were calculated for each item. As responses were skewed positive, the 7-point Likerttype scale is reported as a 4-point scale, with the three disagree categories and the neither agree nor disagree category collapsed into one response category, disagree or neutral.

We also completed postworkshop qualitative interviews with each participating team to complement the individual Intervention Tools survey. We audio recorded the interview sessions, asking about team perceptions of the workshop overall, the facilitation, and their learnings. We also asked about each tool and their intentions to adapt, adopt, and integrate the tools into their larger partnership processes. We transcribed the recorded interviews, and coded the transcriptions using Atlas TI. Coders met weekly to develop a set of standard codes, and subcodes. Responses regarding perceptions of the tools were extracted using queries run in Atlas TI specific to respondent perceptions of the tools.

Results

Among the 25 partnerships participating in the workshops, the majority of projects (60%) had been initiated by both the community and academic partners. About half of participating partnerships were early stage, in which teams were developing a new project or collaboration. On average, projects’ planned duration was 3.2 years (SD = 2.8 years). Of the 24 partnerships responding to the KIS and CES surveys, the partnerships lasted for 6.4 years (SD = 5.3 years), on average (Table 1).

Table 1.

Project Features and Partnership Characteristics (N = 25).

| Project feature/partnership characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Project initiation | ||

| Community partners | 1 | 4 |

| Academic partners | 9 | 36 |

| Both | 15 | 60 |

| Stage of partnership by funding type | ||

| Early stage (planning grant/pilot or new collaboration) | 12 | 48 |

| Single-project partnership | 7 | 28 |

| Multiple-project partnership | 6 | 24 |

|

| ||

| M | SD | |

|

| ||

| Length of project in years | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| Length of partnership in years (n = 24) | 6.4 | 5.3 |

Our postworkshop quantitative surveys and qualitative team interviews completed at the end of the workshop examined the acceptability, feasibility, and intentions to use the tools. Table 2 presents the quantitative responses. The majority of participants indicated that the River of Life tool was compatible with their approach and easy to use, with 90% reporting it was consistent with their values and had benefits over current practice. More than 75% indicated their high agreement they would likely use the River of Life again. About 80% of respondents indicated they highly agreed that the Visioning Tool was beneficial, with about half indicating it was easy to use, nearly 80% indicating it had benefits over current practice, and about half they were likely to use it again.

Table 2.

Postworkshop Tool Assessment by Individual Participants (N = 71): Percentage of Responding High Agreement (Combining “Mostly or Completely Agree”).

| Tool | Consistent with valuesa (%) | Easy to useb (%) | Has benefits over current practicea (%) | Likely to usec (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| River of Life | 90 | 89 | 90 | 77 |

| CBPR model as a Visioning Tool | 86 | 52 | 79 | 54 |

| PDR | 80 | 70 | 77 | 69 |

| PPG | 77 | 63 | 73 | 68 |

Note. CBPR = community-based participatory research; PDR = Partnership Data Report; PPG = Promising Practices Guide.

N = 66 for PPG due to missing data.

N = 68 for PPG due to missing data.

N = 69 for River of Life, N = 70 for Personal Data Report, and N = 68 for PPG due to missing data.

About 80% of respondents highly agreed that the PDR was consistent with their values, and 70% highly agreed that it was easy to use. About 75% highly agreed that it had benefits of their current practice, with nearly 70% agreeing they were likely to use it again. The PPG was similarly positive across the board with percentage points only slightly lower than the PDR for each response. The majority of respondents found most tools very easy to use, with the exception of the need for more support to use the CBPR model as a Visioning Tool, with more than half, 52%, stating it was easy to use.

Table 3 provides examples of qualitative feedback on participant experiences with the four tools. Respondents especially felt the river was useful for understanding their histories and the driving forces of why their partnership was needed. Many community members felt it gave them equal power in the partnership to visually place on paper their own contributions and supporting their future use of the river for other community work (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Select Qualitative Team Feedback on Each Tool.

| Tool | Perceived use | Added value | Future use |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| River of Life | “It reminded me of why we were in this in the first place—what happened, how it happened, such that going back to conflicts, for me it would be helpful as a reminder to say you, in theory, form a strong partnership because of this, and hold onto that, and that should help get you through the conflicts and into where you’re going in the future.” | “It was really neat to like go through the history. So I think it’s something that could be helpful in our own onboarding and training, like if we hired someone tomorrow, do they know how impactful the civil unrest was for our program?” | “Using the River of Life as a great activity for families, for adults maybe and for older kids to really put some time and effort into thinking about their futures.” |

| Visioning with CBPR model | “I think there were a number of components that are were very reflective that stop and make us think about where we’re at and where we’re going. I feel as a group and with larger community engagement, we have so much momentum, we’re going to push forward and we have to do this.” | “I think this particular model would be most useful in situations where there’s a potential or perceived power differential . . .” | “I think this came at a very opportune time because, one, you’re giving us tools that are—that we can readily use.” |

| PDR | “The data report was really helpful . . . I feel like it’s gonna be so helpful for community partners with the colors and a full page you can just kind of focus on one thing at a time or pick the priorities, like three or four.” | “I think that was something very concrete that we could reflect back on. It’s what we’ve aimed to do in the evaluation activities that we’ve done, specifically for the patient advisory group. But I think it was helpful to think about it beyond just our patient engagement because there’s a lot of other groups that we need to engage and to get buy-in from and to work with to make this study successful.” | “I could see sharing that with community partners . . . it provided data in a visual way that many people could connect with and understand. It was a tool of equity, which I really appreciate.” |

| PPG | “I think that the promising practices guide, again it not only helps to define a lot of these areas that have been determined as important for a sustained partnership. I think that the reflections and the questions that are sort of used as guides to facilitate those conversations will make it easier when we go back.” | “For me looking at the PDR compared to the Promising Practicing Guide was important, because I think we had a framework of how we believe that we were doing our work and understanding that it was the three of us that actually did the survey. It helped me to see if we really were on the same page.” | “I know that in the future just with this [the PPG] and the data one, that I know somewhere along the way, I’ll use, just because I’m always looking for some new approach or to make the programs more effective.” |

Note. CBPR = community-based participatory research; PDR = Partnership Data Report; PPG = Promising Practices Guide.

The qualitative feedback on the Visioning Tool was mixed, with some respondents indicating it was complex, while others saw its value and utility. While the text is dense and made it challenging for some, the systematic process of creating their own models enabled teams to reach new understandings of their partnership, from their desired outcomes, to a deeper dive into their contexts, collaborative practices, and their research actions.

The quantitative tools were seen as helpful. Respondents indicated the PDR was concrete, breaking up issues into manageable pieces, one per page; and supporting reflection on underlying partnership processes. As a tangible product, they stated they planned to refer to it later in the project as an iterative thought piece. Teams felt the PPG was also positive, stating it provided additional information on key contributors to positive outcomes. The PPG was also considered an iterative reflection guide for future conversations, and for helping them reframe their work to enhance community research understanding.

Discussion

While all tools are intended to support collective reflection and action, each offers a unique focus and timeframe. For example, the River of Life is process-oriented and grounds the partnership within community context and collaborative history. Teams that had worked together for a decade and those that were newly formed both found the River of Life exercise helpful in centering their discussions on their partnership and recalling the overarching reason for working together. The Model Visioning is both process and outcomes oriented, with a focus on strategizing for the future. Long-term partnerships found this exercise useful in exploring new possibilities, and unknown paths. Newly formed partnerships found this exercise helpful in supporting their brainstorming and “dreaming” of how their work could serve as the foundation for larger, more intensive inquiry. The inward facing, PDR is outcomes oriented, enabling teams to review their collective perceptions of their work. Both long-term and newly formed partnerships used the PDR as a compass for guiding partnership discussions. For long-term partnerships, it served to highlight existing partnership practices. For newly formed teams, it served as a launch pad for new ideas and approaches. The outward facing, PPG is outcomes oriented, supporting teams to think about their practices against national level averages. The full set of reflection tools, enabling review of partnership histories, perceptions of current practices, and comparisons with national-level promising practices, embodies the Freirian approach toward productive change through engaging in “reflection and action directed at the structures to be transformed” (Freire, 1993).

These tools also align with multiple domains of our CBPR model. The PDR, for example, represents one way to generate larger discussions about the team’s approach to partnering, research actions, and outcomes, regardless of partnership and/or project status. In the workshop, one large partnership, which had been working together for more than 10 years, used the PDR as an evaluation tool to help measure both what they had done well, and where they want to improve as they move to a new research phase. Other partnerships with short histories used it to identify their readiness for change; it gave them the language to begin discussions on potentially difficult subjects such as power and resources.

In general, teams responded positively to the tools. Quantitative and qualitative results demonstrate a high level of agreement that the tools are perceived as beneficial, that they have added value above and beyond learnings during the workshop, and that there are ways to revisit the tools and their use with community members and other stakeholders. Noting that the CBPR model seemed complex with the dense text in the first workshop, in subsequent workshops, our E2 team presented two versions of the model for visioning. We first showed the full model that contains process and outcome variables from the literature; and secondly showed just the four large rectangles with the titles of each domain inside each rectangle: contexts, partnering processes, intervention/research, and outcomes. This allowed for partners to focus on the larger categories and see the model as a living document to reshape for their own purposes. This more open process enabled teams to add their own text of which context issues matter, which practices are most important, which strategies they use to involve community members in research and intervention planning, and which outcomes they care about. For more examples of the usefulness of the CBPR model, distinct applications have been recently compiled from several global contexts. Specifically, the model has been used as a planning framework in Sweden, an evaluation strategy in Australia, an organizational development tool in Nicaragua, and an overarching guide for Morgan State, Baltimore’s research training center, for which the model supported pilot academic–community partnerships in their developmental processes (Wallerstein et al., in press).

The workshops hosted by E2 were the first effort to test all four tools with CBPR partnerships from a national sample. More research would be useful in examining the applicability and use of these tools within specific partnership settings. For example, given the relatively low number of teams that participated, we may not have a comprehensive understanding of tool performance across all types of CBPR projects. Examining tool use within specific settings, or with teams at the early stages of partnership development compared with teams at more mature levels of partnership development, might yield more information on how these tools can be useful, or what the limits of use may be for certain types of teams.

While we developed the tools with the aim of supporting a wide variety of CBPR partnerships, it is unclear how the tools might be perceived differently depending on the length of time the partnership has been together, the focus of the CBPR project, or the level of individual exposure and uptake of the tools. Continuing to examine the tools use across diverse settings will help establish the overall fit. In addition, a longitudinal study of research teams that used the tools would also provide data on whether these tools support partnerships over the course of the partnership.

In general, these innovative reflection-action tools provided community and academic partners structured yet flexible ways to examine their partnering practices and identify collaborative approaches toward greater collective empowerment, with the aim to improve project outcomes. Specific process tools and activities that enliven our values and commitment to equity and align our work with others who share our vision and ideals contribute to broader project outcomes and reinforce partnership aims to improve health at the community level. The tools in this intervention remind us of why we entered our fields in the first place, and energize our work going forward. Viewing community as an ecologically connected system requires contexts and cultural knowledge to be factored into partnership practices (Trickett & Beehler, 2013). The tools discussed in this article were developed to enhance the science of CBPR/CEnR, including partnership contexts and cultural knowledge, with the ultimate goal of improving health and social equity.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge our partners with the E2 study: the University of New Mexico (UNM) Center for Participatory Research, University of Washington (UW) Indigenous Wellness Research Institute and School of Medicine, Community Campus Partnerships for Health, National Indian Child Welfare Association, University of Waikato, RAND Corporation, and the national Think Tank of community and academic CBPR scholars and experts.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for Engage for Equity: Advancing CBPR Practice Through a Collective Reflection and Measurement Toolkit was from the National Institute of Nursing Research: 1 R01 NR015241-01A1. We are thankful for our previous Research for Improved Health NARCH study and partners, which led to Engage for Equity (UNM, UW and the National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center), with support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences in partnership with the Indian Health Service (U26IHS300009 and U26IHS300293), with additional funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research, the National Cancer Institute, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Please note that we have bolded the terms in the text that are major constructs in the CBPR conceptual model (Figure 1) to provide a guide to the content we developed and standardized across the CBPR Tools.

References

- Brownson RC, Colditz GA, & Proctor EK (2017). Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boursaw B, Oetzel J, Dickson E, Thein T, Sanchez-Youngman S, Peña J, Parker M, Magarati M, Littledeer L, Duran B, & Wallerstein N (2020). Psychometrics of measures of community-academic research partnership practices and outcomes. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, & Mercer S (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29(1), 325–350. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T, Brandon T, Zonouzi M, & Thomson L (2019). Destabilizing equilibriums: Harnessing the power of disruption in participatory action research. Educational Action Research, 27(3), 379–395. 10.1080/09650792.2019.1618721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson E, Magarati M, Boursaw B, Oetzel J, Devia C, Ortiz K, & Wallerstein N (2020). Characteristics and practices within research partnerships addressing health and social equity. Journal of Nursing Research, 69(1), 51–61. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, Parker M, Belone L, Oetzel J, Magarati M, Zhou C, Roubideaux Y, Muhammad M, Pearson C, Belone L, Kastelic SH, & Wallerstein N (2019). Towards health equity: A national study of promising practices in community-based participatory research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 13(4), 337–352. 10.1353/cpr.2019.0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (A Continuum book). Herder & Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Rev. 20th anniversary ed.). Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman L, Thomas A, Nnawulezi K, Lippy N, Serrata C, Ghanbarpour J, Sullivan C, & Bair-Merritt S (2018). Bringing community based participatory research to domestic violence scholarship: An online toolkit. Journal of Family Violence, 33(2), 103–107. 10.1007/s10896-017-9944-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M, Thompson V, Arroyo Johnson C, Gennarelli R, Drake B, Bajwa P, Witherspoon M, & Bowen D (2017). Evaluating community engagement in research: Quantitative measure development. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(1), 17–32. 10.1002/jcop.21828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Coombe C, Cheezum R, Schulz A, Mcgranaghan R, Lichtenstein R, Reyes AG, Clement J, & Burris A (2010). Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 100(11), 2094–2102. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Shultz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.). (2013). Methods for community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Kastelic SL, Wallerstein N, Duran B, & Oetzel JG (2018). Socio-ecologic framework for CBPR: Development and testing of a model. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 363–367). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones A, Mango J, Jones F, & Lizaola E (2013). On measuring community participation in research. Health Education & Behavior, 40(3), 346–354. 10.1177/1090198112459050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero JE (2013). Trust as an ethical construct in community based participatory research partnerships (Order No. 3588107) [Doctoral dissertation, University of New Mexico]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero JE, Boursaw B, Eder M, Greene-Moton E, Wallerstein N, & Oetzel JG (2020). Engage for equity: The role of trust and synergy in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 372–379. 10.1177/1090198120918838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Alegria M, Greene-Moton E, Israel B, Kastelic S, Magarati M, Oetzel J, Pearson C, Schulz A, Villegas M, & White Hat ER (2018). Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12(1), 55–74. 10.1177/1558689816633309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Ong M, Jones K, Chung L, Dixon B, Tang E, Gilmore J, Sherbourne C, Ngo VK, Stockdale S, Ramos E, Belin TR, & Wells E (2013). Community-partnered evaluation of depression services for clients of community-based agencies in under-resourced communities in Los Angeles. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(10), 1279–1287. 10.1007/s11606-013-2480-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman A, Avila M, & Belone L (2015). Reflections on researcher identity and power: The impact of positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Critical Sociology, 41(7–8), 1045–1063. 10.1177/0896920513516025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. National Academies Press. 10.17226/24624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Truong CKY, Tang J, & Hsiao C (2017). Community interactive research workshop series: Community members engaged as team teachers to conduct research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 11(2), 215–221. 10.1353/cpr.2017.0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel JG, Duran B, Sussman A, Pearson C, Magarati M, Khodyakov D, & Wallerstein N (2018). Evaluation of CBPR partnerships and outcomes: Lessons and tools from the Research for Improved Health study. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 363–367). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Patel MR, TerHaar L, Alattar Z, Rubyan M, Tariq M, Worthington K, Pettway J, Tatko J, & Lichtenstein R (2018). Use of storytelling to increase navigation capacity around the Affordable Care Act in communities of color. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 12(3), 307–319. 10.1353/cpr.2018.0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae R, Jones M, Handal A, Bluehorse-Anderson M, Frazier S, Maltrud K, Percy C, Tso T, Varela F, & Wallerstein N (2016). Healthy Native community fellowship: An Indigenous leadership program to enhance community wellness. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 7(4). 10.18584/iipj.2016.7.4.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Miranda AA, King LM, Salihu HM, Berry E, Austin D, Nash S, Scarborough K, Best E, Cox L, King G, Hepburn C, Burpee C, Richardson E, Ducket M, Briscoe R, & Baldwin J (2017). Exploring the life course perspective in maternal and child health through community-based participatory focus groups: Social risks assessment. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 10(1), 143–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Youngman S, & Wallerstein N (2018). Partnership river of life: Creating a historical time line. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 363–367). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Shea CM, Jacobs SR, Esserman DA, Bruce K, & Weiner BJ (2014). Organizational readiness for implementing change: A psychometric assessment of a new measure. Implementation Science: IS, 9, Article 7. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood S, Cronin C, & Kostizak K (2018). Participatory research toolkit. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5df678c23b758e75366c17cd/t/5e65c84187bd3863b8389431/1583728710133/Participatory+Research+Toolkit+Rain+Barrel+Communications.pdf

- Trickett E, & Beehler S (2013). The ecology of multi-level interventions to reduce social inequalities in health. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1227–1246. 10.1177/0002764213487342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Belone L, Burgess E, Dickson E, Gibbs L, Parajon LC, Ramgard M, Sheikhattari P, & Silver G (in press). Community based participatory research: Embracing praxis for transformation. In International SAGE handbook for participatory research. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Duran B (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100(Suppl. 1), S40–S46. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, & Minkler M (2018). Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Muhammad M, Avila M, Belone L, Lucero J, Noyes E, Roubideaux Y, Sigo R, & Duran B (2019). Power dynamics in community based participatory research: A multi-case study analysis partnering contexts, histories and practices. Health Education and Behavior, 46(1 Suppl.), 19S–32S. 10.1177/1090198119852998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Duran B, Belone L, Tafoya G, & Rae R (2008). What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In Minkler M & Wallerstein N (Eds.). Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Duran B, Magarati M, Pearson C, Belone L, Davis J, DeWindt L, Kastelic S, Lucero J, Ruddock C, Sutter E, & Dutta M (2019). Culture-centeredness in community based participatory research: Its impact on health intervention research. Health Education Research, 34(4), 372–388. 10.1093/her/cyz021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Sanchez-Youngman S, Boursaw B, Dickson E, Kastelic S, Koegel P, Lucero JE, Magarati M, Ortiz K, Parker M, Peña J, Richmond A, & Duran B (2020). Engage for equity: A long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 380–390. 10.1177/1090198119897075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Jones B, Chung L, Dixon B, Tang E, Gilmore L, Sherbourne C, Ngo VK, Ong MK, Stockdale S, Ramos E, Belin TR, & Miranda S (2013). Community-partnered cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning or resources for services to address depression disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(10), 1268–1278. 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell N, Sarche M, Keane E, Mousseau A, & Kaufman C (2018). Advancing scientific methods in community and cultural context to promote health equity: Lessons from intervention outcomes research with American Indian and Alaska Native communities. American Journal of Evaluation, 39(1), 42–57. 10.1177/1098214017726872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn S, Valentine S, Patrick K, Baldwin M, Chablani-Medley A, Aguilar Silvan Y, Shtasel DL, & Marques L (2019). Practical solutions for sustaining long-term academic-community partnerships. Psychotherapy, 56(1), 115–125. 10.1037/pst0000188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]