ABSTRACT.

About 75% cases of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) occur in India. Although the classic description of PKDL is the progression from initial hypopigmented macular lesions to papules to plaques and nodular lesions, atypical morphologies are also seen and are easily missed or misdiagnosed. We report a case of a 27-year-old man who presented to us with multiple acral ulcers and verrucous lesions for 5 years. A diagnosis of PKDL was made based on slit skin smear, histopathology, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The patient was given combination therapy with four doses of liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine 50 mg twice daily for 45 days. In this report, we discuss unusual morphologies of PKDL, the pathway to the diagnosis, and the therapeutic options available along with their efficacy.

INTRODUCTION

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) serves as a reservoir of Leishmania parasites in the community, and hence, its treatment is important for epidemiological reasons, apart from achieving clinical clearance in affected patients. India contributes to 75% of PKDL cases worldwide.1 Early diagnosis is of utmost importance because most cases of PKDL are asymptomatic, and thus, patients may not seek voluntary treatment. Although the classic presentation of PKDL entails progression from initial hypopigmented macular lesions to papules, plaques, and nodular lesions, atypical morphologies and presentation are also seen and are easily missed or misdiagnosed.2 We report an atypical case of PKDL, in which the patient presented to us with multiple de novo acral ulcers and verrucous lesions. We also discuss the unusual morphologies of PKDL, a pathway to the diagnosis, and available therapeutic strategies and their efficacy.

Case report.

A 27-year-old man who resided in an endemic district of Bihar state, India, presented to us with multiple ulcers over the dorsum of both hands and fingers, dorsum of the left foot, and plantar surface of the right foot of 5 years duration (Figure 1). Ulcers showed protuberant granulation tissue covered with hemorrhagic crusting and were present on a nonindurated base. In addition, verrucous nodules were present at the right elbow and wrist (Figure 2). The patient also had erythematous to skin-colored asymptomatic papules and nodules over the chin (muzzle area) and neck. The sensory and motor functions were intact, and there was no peripheral nerve enlargement. He had a history of kala-azar 15 years earlier, for which he had received both parenteral and oral medications. However, no records were available to confirm this. He also noted a history of kala-azar in his father.

Figure 1.

Well-demarcated ulcers with raised margins, granulation tissue, and necrotic yellowish slough on the floor, present over hands and feet.

Figure 2.

Verrucous nodule seen over the elbow.

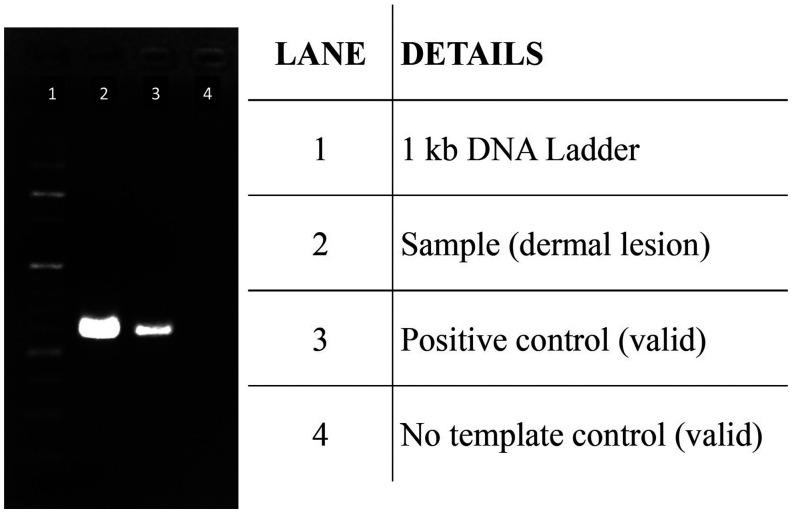

Baseline workup, including complete hemogram, liver and kidney function tests, and lipid profile, were within normal limits. Urine routine/culture and viral markers were negative. Abdominal ultrasound showed hepatosplenomegaly. Serum samples for Rk39 rapid diagnostic test (RDT), skin slit smears for Giemsa staining for Leishmania donovani bodies (LD bodies), and skin biopsy (from in and around the lesion) for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were sent to the Center for Arboviral and Zoonotic Diseases, at India’s national center for disease control in Delhi. A skin biopsy sample was sent for histopathological examination. The serum sample was positive for RK39 RDT, slit skin smear showed 5+ LD bodies (10–100 LD bodies/high-power field) (Figure 3), and skin biopsy showed foamy histiocytes laden with intracytoplasmic LD bodies (Figure 4). Fite stain for acid-fast bacilli and a PCR for Mycobacterium leprae3 (using three gene targets: RLEP, 16SrRNA, and sodA) were negative, and nerve electrophysiological studies were normal. Samples from the lesions and surrounding skin were also tested by amplifying a 557-bp fragment of kinetoplast DNA from L. donovani.4 Briefly, DNA from the clinical samples was extracted using QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR assay used forward (5′-AAATCGGCTCCGAGGCGGGAAAC-3′) and reverse primers (5′-GGTACACTCTATCAGTAGCAC-3′) and was performed using GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction conditions included initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 minutes followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 minute), annealing (45°C for 1 minute), and extension (72°C for 2 minutes). A final extension step of 72°C for 3 min was used. The amplification product was resolved in a 1% agarose gel with 10 v/cm voltage in TAE buffer. The gel was documented on the Azure 280 gel documentation system (Azure Biosystems, Dublin, CA) with an EtBr filter. The experiment yielded a positive result, confirming the presence of L. donovani in lesional skin biopsy samples (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Slit skin smear stained with Giemsa stain showing Leishmania donovani bodies (blue arrow) (10–100 L. donovani bodies/high-power field).

Figure 4.

Histopathology showing foamy histiocytes laden with intracytoplasmic Leishmania donovani bodies (black arrow; hematoxylin & eosin stain, ×100).

Figure 5.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification of 557-bp region in the kinetoplast DNA of Leishmania donovani in samples from the lesion and perilesional area. The test was validated using positive control and no template control.

On the basis of clinical, histopathological, serological, and molecular tests, PKDL was diagnosed and the patient was given four doses of liposomal amphotericin B (LamB; 20 mg/kg given as 5 mg/kg per dose) with miltefosine (100 mg/day for 45 days), along with regular antiseptic dressings. This led to the complete resolution of all lesions within 6 weeks. The patient remains in our follow-up and has not had a relapse of skin lesions (at 6 months after treatment discontinuation).

DISCUSSION

Although a typical presentation with hypopigmented macules, papules, and nodules, along with a previous history of kala-azar, suggests a diagnosis of PKDL, atypical presentations and considerable epidemiological overlap of leprosy and kala-azar–endemic zones lead to diagnostic difficulties. Reported atypical presentations of PKDL include micropapular form (measles-like), erythrodermic form, photosensitivity (with erythema of butterfly area of the face), annular, verrucous, papillomatous, fibroid, and xanthomatous lesions. Other rare presentations include verrucous growth on heels, chronic paronychia-like lesions, and ulcerative lesions.5,6 The patient presented here had a long-standing disease and did not seek treatment early. Ulceration is not a common feature of either Indian or Sudanese PKDL and has mostly been reported to present over an underlying extensive dense maculopapular/nodular involvement extending to acral parts. This has been classified as grade 3 PKDL according to a severity scoring proposed by Sudanese researchers.7 A de novo presentation with acral ulcers with apparently normal surrounding skin, as in the reported patient, is highly unusual. Cutaneous leishmaniasis becomes a relevant differential here and was excluded in our case by molecular studies and epidemiological factors.

The approach to diagnosing a case of PKDL involves clinical examination, rk39 strip test, slit skin smear, histopathology, and molecular testing. Serological tests such as the direct agglutination test, ELISA, and the rK39 rapid diagnostic test are usually positive in PKDL but are of limited value8 because a positive result may be due to antibodies persisting after a past episode of visceral leishmaniasis. Nevertheless, serology can be helpful when other diseases (e.g., leprosy) are considered in the differential diagnosis or when a previous history of visceral leishmaniasis is uncertain. Slit skin smear is the gold standard owing to its high specificity and lower threshold to detect LD bodies (four parasites/microliter of slit aspirate) compared with tissue biopsy (60 parasites/microgram tissue DNA).9 Histopathology in our case showed the presence of foamy histiocytes akin to lepromatous leprosy, adding to the diagnostic confusion. However, foamy histiocytes have also been reported to occur in nodular PKDL lesions. In a report by Singh et al., foamy histiocytes were seen in 34% of cases of PKDL and were mostly loaded with LD bodies.10 Detecting kinetoplast DNA by PCR greatly increases sensitivity and permits species diagnosis in tissue specimens. PCR can be performed on skin biopsy samples or slit skin specimens in well-equipped laboratories and is substantially more sensitive. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) has the advantage of quantification, automation, high throughput possibility, and rapidity and is the preferred biomarker to measure the response to treatment objectively.11 In typical presentations, a histopathological and smear examination in the clinic may be sufficient to establish a diagnosis; however, atypical presentations warrant more extensive workup.

A very high load of LD bodies (≥ 5) in smears from the patient’s ulcers underscored the need for effective antiparasitic treatment to achieve disease remission, prevent relapses, and halt possible disease transmission from these highly infected lesions. Treatment protocols for PKDL have largely followed those researched for visceral leishmaniasis. However, endpoints are more difficult to define when treating PKDL because clinical features take variable time to resolve after successful treatment, and qPCR is not routinely available in endemic areas. Miltefosine is the first-line oral drug approved by WHO at 50 mg twice daily for adult patients. However, cure rates with the drug have declined over time. Although initial cure rates reported with miltefosine were ∼95%,12 more recent studies estimate this to be ∼85%.13 Further, relapse rates after miltefosine treatment have recently increased from nil initially to 10% to 30% (higher with shorter treatment durations). The availability of the drug in endemic areas is also erratic, and frequent gastrointestinal side effects hamper compliance with long treatment durations recommended. With the waning clinical efficacy of miltefosine,14 LamB is increasingly being used for PKDL, akin to its use in visceral leishmaniasis, either alone or in combination with miltefosine. Initially, LamB was used in a dose of 30 mg/kg15 and shown to achieve 86% cure rates but was associated with six unexpected cases of hypokalemia-associated rhabdomyolysis,16 a possible dose-related adverse effect of LamB. Subsequently, a lower cumulative dose of 15 mg/kg was tried and shown to achieve a complete cure in 78% of patients.17 With a view to improve cure rates and relapse rates while keeping treatment duration and adverse effects to a minimum, a combination of both drugs (miltefosine 100 mg/day for 45 days and LamB 15 mg/kg) was studied and shown to achieve a 100% cure rate, with no relapses at 18 months follow-up.18 Thus, we similarly used the combination treatment in our patient with an aim to clear his very high parasitic load. We report this case to highlight the rare and unusual (de novo) ulcerated and verrucous presentation of PKDL, the importance of diagnostics tools in diagnosing atypical forms of PKDL, and the efficacy of the combination therapy (miltefosine and LamB) in this context.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Nupur Roy, National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, New Delhi, for her valuable contribution. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene assisted with publication expenses.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ghosh P, Roy P, Chaudhuri SJ, Das NK, 2021. Epidemiology of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol 66: 12–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar P, Chatterjee M, Das NK, 2021. Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: clinical features and differential diagnosis. Indian J Dermatol 66: 24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pathak VK, Singh I, Turankar RP, Lavania M, Ahuja M, Singh V, Sengupta U, 2019. Utility of multiplex PCR for early diagnosis and household contact surveillance for leprosy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 95: 114855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salotra P, Sreenivas G, Pogue GP, Lee N, Nakhasi HL, Ramesh V, Negi NS, 2001. Development of a species-specific PCR assay for detection of Leishmania donovani in clinical samples from patients with kala-azar and post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol 39: 849–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jha AK, Mallik SK, Ganguly S, Jaykar KC, 2012. An unusual case of multiple erythematous nodules with ulcerative lesion. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 78: 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jha AK, Anand V, Mallik SK, Kumar P, 2012. Post kala azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) presenting with ulcerated chronic paronychia-like lesion. Kathmandu Univ Med J 10: 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zijlstra EE, el-Hassan AM, Ismael A, 1995. Endemic kala-azar in eastern Sudan: post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 52: 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization , 2010. Control of Leishmaniasis. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-TRS-949. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- 9. Bhargava A, Ramesh V, Verma S, Salotra P, Bala M, 2018. Revisiting the role of the slit-skin smear in the diagnosis of Indian post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 84: 690–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Singh A, Ramesh V, Ramam M, 2015. Histopathological characteristics of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: a series of 88 patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 81: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dixit KK, Singh R, Salotra P, 2020. Advancement in molecular diagnosis of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol 65: 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramesh V, Katara GK, Verma S, Salotra P, 2011. Miltefosine as an effective choice in the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol 165: 411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramesh V, Singh R, Avishek K, Verma A, Deep DK, Verma S, Salotra P, 2015. Decline in clinical efficacy of oral miltefosine in treatment of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) in India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0004093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramesh V, Singh R, Avishek K, Verma A, Deep DK, Verma S, Salotra P, 2015. Decline in clinical efficacy of oral miltefosine in treatment of post kala-azar. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0004093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zijlstra EE, Alves F, Rijal S, Arana B, Alvar J, 2017. Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in the Indian subcontinent: a threat to the South-East Asia Region Kala-azar Elimination Programme. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0005877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marking U, den Boer M, Das AK, Ahmed EM, Rollason V, Ahmed BN, Davidson RN, Ritmeijer K, 2014. Hypokalaemia-induced rhabdomyolysis after treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) with high-dose AmBisome in Bangladesh – a case report. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. den Boer M, Das AK, Akhter F, Burza S, Ramesh V, Ahmed BN, Zijlstra EE, Ritmeijer K, 2018. Safety and effectiveness of short-course AmBisome in the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: a prospective cohort study in Bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis 67: 667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramesh V, Dixit KK, Sharma N, Singh R, Salotra P, 2020. Assessing the efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine in combination for treatment of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis 221: 608–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]