Summary

Background

In 2016, Brazil scaled up the Criança Feliz Program (PCF, from the acronym in Portuguese), making it one of the largest Early Childhood Development (ECD) programs worldwide. However, the PCF has not been able to achieve its intended impact. We aimed to identify barriers and facilitators to achieving the PCF implementation outcomes across the RE-AIM dimensions (Reach, Effectiveness or Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This comparative case study analysis selected five contrasting municipalities based on population size, region of the country, implementation model, and length of time implementing the PCF. We conducted 244 interviews with PCF municipal team (municipal managers, supervisors, home visitors), families, and cross-sectoral professionals. A rapid qualitative analysis was used to identify themes across RE-AIM dimensions.

Findings

Families’ limited knowledge and trust in PCF goals were a barrier to its reach. While the perceived benefit of PCF on parenting skills and ECD enabled reach, the lack of referral protocols to address social needs, such as connecting food-insecure families to food resources, undermined effectiveness. Questions about whether the social assistance sector should be in charge of PCF challenged its adoption. Implementation barriers exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic included low salaries, temporary contracts, high turnover, infrequent supervision, lack of an effective monitoring system, and nonexistence or non-functioning multisectoral committees. The absence of institutionalized funding was a challenge for sustainability.

Interpretation

Complex intertwined system-level barriers may explain the unsuccessful implementation of PCF. These barriers must be addressed for Brazil to benefit from the enormous reach of the PCF and the evidence-based nurturing care principles it is based upon.

Funding

NIH/NICHD.

Keywords: Early child development, Home-visiting programs, Nurturing care, Brazil, Implementation science, Scale-up, Case study, Qualitative methods

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, Ovid Global Health, and LILACS and grey literature sources in English, Spanish, and Portuguese from inception through July 2022 for synonymous of “Care for Child Development”, “Reach Up”, “implementation”, and “multisectoral”. Studies were restricted to those conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). These searches resulted in 75 records that yielded implementation details for 33 programs across 23 LMICs. Evidence from this systematic search indicated that successful implementation of evidence-based early childhood development (ECD) programs such as Care for Child and Reach Up requires attention to the local context and the intentional use of evidence-based adaptations to ensure the quality of implementation and sustained long-term impacts. Poor quality and lack of fidelity represented a critical implementation barrier undermining program effectiveness and sustainability. However, there is currently limited knowledge of the implementation strategies required to sustain the high quality and fidelity of ECD programs at a large scale in LMIC.

In this context, Brazil is an important case study to understand why the largest ECD program globally (i.e., the Criança Feliz Program PCF—Happy Child Program in English) did not achieve an impact on parenting and ECD outcomes when implemented under real-world conditions during the timeframe that included the COVID-19 pandemic. The lack of PCF impact on ECD outcomes during a public health emergency should not be regarded as conclusive; instead, it calls for investing in understanding how implementation bottlenecks led to a lack of effectiveness. Evidence from in-depth interviews with PCF national and state managers identified challenges in the design of the PCF implementation that needed to be thoroughly evaluated at the municipal level—where the program is operated and delivered. To our knowledge, no research has specifically investigated PCF implementation outcomes across contrasting Brazilian municipal contexts, especially in large urban municipalities, where implementation has been more challenging.

Added value of this study

The findings of this qualitative comparative case studies analysis (total of 244 in-depth interviews) guided by the robust RE-AIM implementation framework add to the growing implementation science literature, specifically the evaluation of large-scale programs in LMIC. Our findings identified the home visit strategy as a strength, providing the municipalities and the social assistance sector the opportunity to develop the technical capacity and infrastructure to work on strengthening parenting skills, ECD outcomes, and enhancing family ties. On the other hand, complex intertwined system-level barriers concentrated in the adoption, reach, and implementation dimensions of PCF negatively affected the quality of home visits, implementation fidelity, and the multisectoral nurturing care approach to address the social needs of participating families (e.g., connecting food-insecure families to food resources) required for effective delivery of the PCF. Fidelity-inconsistent modifications exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the PCF dosage, content, and relationships, creating a strong loss of program “voltage,” which may explain why the largest ECD program in the world has failed to achieve its intended impact on parenting and ECD outcomes among vulnerable families in Brazil.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings can support implementers and policymakers to define evidence-informed strategies for optimizing the large-scale implementation and sustainability of home-visiting ECD programs. The use of implementation science frameworks such as the RE-AIM supported the integration of existing evidence into pragmatic implementation strategies to achieve quality, fidelity, and sustainability of large-scale ECD programs. These implementation strategies may include an outreach plan to promote equitable access (reach); fidelity-consistent protocols to adapt dosage, content, and relationships during home visits to increase the fit, relevance, and appropriateness of a nurturing care approach to the local contexts (effectiveness); integrate ECD services into existing health, social, education systems (adoption); innovative funding streams to increase fidelity of quality training, supervision, and monitoring to allow greater return of investments (implementation); establish a strategic plan for evidence-informed advocacy to promote ECD demand within and across systems (maintenance). Future mixed methods implementation research should investigate the mechanisms through which implementation strategies may improve quality, fidelity, and sustainability.

Introduction

Enabling nurturing care for early childhood development (ECD) requires stimulating and safe environments that are sensitive to children's health and nutrition needs, and provide them with timely and developmentally appropriate learning experiences, together with responsive and emotionally stimulating interactions.1 Based on this premise, the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, and the World Bank launched the Nurturing Care Framework that outlines a roadmap of five components—good health, adequate nutrition, safety and security, opportunities for early learning, and responsive caregiving, which are necessary for every child to survive and thrive. Therefore, investing in programs that support families in providing nurturing care has become a global priority to tackle inequities in ECD.1,2

Brazil is the largest country in Latin America and the Caribbean, with over 215 million people living across 5570 municipalities in 26 states and the Federal District. Approximately 11% of the population of Brazil are children under 6 years old. Almost a quarter of the population is poor, and strong racial and ethnic inequalities persist, disproportionately affecting access to the provision of nurturing care among the most disadvantaged families and preventing millions of children from achieving their optimal development.3 Nurturing care for ECD is a citizen's right established by the Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988 and the Statute of the Child and Adolescent of 1990 and reaffirmed in the 2016 Early Childhood Legal Framework.4,5 As a result, the Programa Criança Feliz (PCF, Happy Child Program in English) was launched in 2016 by the national government to implement an evidence-informed large-scale home-visiting program along with complementary multisectoral actions aimed at strengthening parenting skills, providing early stimulation, and reducing vulnerabilities of families with pregnant women and children under three years old living in poverty.6

The PCF has been scaled up to 3028 out of the 5570 Brazilian municipalities. Program scale-up is based on expanding the coverage of a quality program to broader geographic areas, to maximize reach, effectiveness, and long-term positive impact.7 During these seven years of scaling up, the Brazilian government commissioned mixed methods studies to assess the PCF process and impact outcomes.8, 9, 10, 11 The results of the process evaluation led to changes and adjustments to the implementation protocols; for example, in 2018, the PCF target population was expanded to any families living in poverty conditions who are registered with the National Database of Vulnerable Populations (CADÚNICO), replacing the original criterion that restricted PCF enrollment to beneficiaries of the conditional cash transfer program.6,8,9 By 2021, the PCF exceeded 57 million home visits, becoming one of the largest ECD programs globally.

Despite the enormous reach, the impact study conducted in 30 municipalities with 3242 children did not find any effects of the PCF on childhood development, responsive parental interactions, or psychological attributes of children, including psycho-emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviours.11 The lack of impact of PCF found in the randomized evaluation study was attributed to challenges such as disruptions in the delivery of home visits due to COVID-19 pandemic and violation of the integrity of randomization procedures in some municipalities. Due to these challenges, several sensitivity analyses confirmed that the dosage of home visits received was not sufficient to impact ECD outcomes.11 These findings underscore that relying on the dosage of home visits, which in the case of PCF was low on average, without paying attention to quality is not a good use of resources. Therefore, contextual-sensitive and structural barriers to implementation quality were the focus of our study.

Quality implementation of ECD programs results from well-coordinated and delivered structural attributes, including dosage and content, and high-quality process attributes, which refer to how the intervention is delivered and the nature of the interactions between the home visitors, caregivers, and children.12 In addition, successful implementation of large-scale ECD programs requires attention to the local context and the intentional use of evidence-based program adaptations to ensure quality of implementation and sustained long-term impacts.13 Therefore, in 2019, we began a two-phase qualitative evaluation of the implementation at scale of the PCF.14,15 In the first phase, in-depth interviews with national and state key informants indicated challenges in the design and top-down approach of PCF implementation that needed to be thoroughly evaluated at the municipal level—the “frontline” where the program is operated and delivered,6 especially in large urban municipalities, where implementation was reported to be even more challenging. Thus, the objective of the second phase of our evaluation was to conduct an in-depth comparative case study analysis of five contrasting municipalities to identify barriers and facilitators to achieving implementation outcomes in the scaling up of the PCF during the acute and subsequent phases of the COVID-19 pandemic from the point of view of key informants, including families.

Methods

This comparative qualitative case study16 received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Institute of the São Paulo State Health Department (n. 3.320.733) and by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (n. 1702327-2). Additional approvals were granted by the research committees of the participating municipalities and departments. All participants provided verbal informed consent following a description of the study's purpose and design. We followed the Consolidated Advice for Reporting Early Childhood Development implementation research (C.A.R.E.)17 and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ)18 to report this study (Supplementary Table S1).

Study setting

An overview of the PCF implementation design is provided in Box 1, and the comparative implementation design across municipalities following the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)23 is summarized in Supplementary Table S2. The guidance provided by the national PCF coordination unit across different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, i.e., early in the pandemic (March 2020–June 2020), halfway through the pandemic (July 2020–May 2021), when this study was conducted (June 2021–May 2022, progressive reduction of physical distancing measures) is summarized in Supplementary Table S3. During data collection, we were able to assess barriers that persisted from before the pandemic as well as adaptations that occurred across different phases of the pandemic.

Box 1. Description of Criança Feliz Program following the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR).19.

The Criança Feliz Program (PCF, Happy Child Program in English), which aims to increase early learning opportunities by helping parents develop their responsive parenting skills, was launched on a large scale by the Brazilian federal government under the Unified Social Assistance System (SUAS)—which is a government-run universal social assistance system based on a participatory and decentralized management model that organizes and funds social assistance centers such as the Social Assistance Reference Centers (CRAS/SUAS) and the Social Assistance Specialized Reference Centers (CREAS/SUAS).20 Historically, the most vulnerable families have had access to benefits and social services, depending on the needs prioritized by CRAS teams, including services provided by non-profit organizations networks.20 Therefore, the integration of home visits and coordinated complementary multisectoral actions to support nurturing care services for families with pregnant individuals and young children into the SUAS was an innovation from the social sector perspective. Interestingly home visiting services for families with young children have been widely implemented in the health sector for decades in Brazil.21 The PCF is offered to families living under poverty conditions who are registered with the National Database of Vulnerable Populations (CADÚNICO). The implementation activities and strategies used to implement the PCF were operationalized at the municipal level, with technical support provided at the federal and state levels. PCF key implementation processes include (a) hiring the municipal workforce, (b) training, (c) supervision and monitoring, (d) home visits (e) complementary multisectoral actions, (f) funding and resources. In brief, the implementation is coordinated by the Multisectoral Management Committee (MMC) at the three government levels (national, state, and municipal). The MMC is formed by PCF supervisor and managers representing the social assistance, education, health, culture, and human rights sectors. The MMC coordinates social assistance services and public policies to operationalize the complementary nurturing care multisectoral actions of the PCF. At the national level, the PCF is coordinated by the Ministry of Development and Social Assistance, Family, and Fight against Hunger. At the state level, a technical team is formed by coordinator and technical assistance personnel known as facilitator who are responsible for providing technical support to municipalities for the implementation of the PCF. Facilitators are trained through a training cascade strategy and are responsible for delivering the 80-h initial training to municipal supervisors and home visitors, based on the Care for Child Development (CCD) curriculum22 and the PCF Home Visiting Guide. At the municipal level, municipal technical teams coordinate PCF implementation. The PCF municipal team is formed by at least one municipal coordinator (optional), supervisors (one for up to 15 home visitors), and home visitors (one for every 34 families). Higher education is required for the municipal coordinator and the supervisors, while the home visitors must have at least completed high school. The supervisors oversee the home visitors, which is essential for maintaining PCF home visiting implementation fidelity and the operationalization of the necessary complementary multisectoral actions. The home visits must be planned and carried out by the home visitors, and monitored by the supervisors. The PCF recommends monthly visits for pregnant individuals, weekly for young children under 36 months, and biweekly or monthly for children between 36 and 72 months who lost one of their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic, or children with disabilities enrolled in the Continuous Cash Benefit program. The perceived social needs of the families during the home visit must be reported to the supervisors who work together with the MMC to develop complementary multisectoral actions to provide a comprehensive nurturing care safety net for families. The municipal coordinator and supervisor monitor the reach and quality of visits through the electronic monitoring system (called e-PCF), which is critical for accounting for the monthly home visits targets that are needed to generate the PCF transfer of federal funding to municipalities. Box 2 The national guidance provided to municipalities to maintain PCF implementation during COVID-19 pandemic is summarized in Supplemental Table S3.

Participant selection

Selection of municipalities

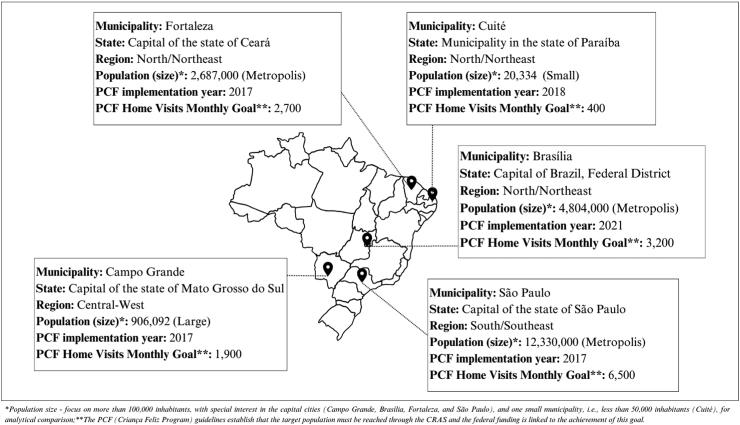

We used purposive sampling to select information-rich cases for the most effective use of limited evaluation resources.19 The municipalities engaged in the PCF impact study11 were excluded due to the potential for “research fatigue.”24 The criteria for selecting the municipalities were co-developed25,26 between the research team and the national PCF coordination team based on the identified challenges in the adoption and implementation of the PCF in large urban contexts.6,8 Five agreed-upon criteria were used to select the municipalities: (a) Large municipalities and capital cities were selected because they were not included in previous research11 and challenges with scale-up were identified in the first phase of the PCF evaluation.6,8 (b) Municipalities implementing PCF for at least 6 months; (c) Representing a unique implementation model, e.g., the integration of home-visiting programs in the health sector or with existing social assistance programs, to learn different lessons for national, state, and municipal administrations; (d) Represent a Brazilian region, including the North/Northeast, Central-West, and South/Southeast, to have geographical representation; (e) Availability and willingness of the municipality to participate.19 Based on these concepts, the national PCF coordination team connected the research team with municipalities eligible to participate in the in-depth qualitative case study. Five municipalities were selected: three capital cities that are large metropolitan areas with more than 100,000 inhabitants—Brasília, Fortaleza, and São Paulo—and one capital city that is a large municipality (Campo Grande). In addition, we included a small municipality with less than 50 thousand inhabitants (Cuité) to enrich the comparative case study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the municipalities included in the comparative case study of the Criança Feliz Program.

Sampling

In-depth interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of (a) municipal PCF teams, including municipal coordinators, supervisors, and home visitors (N = 132); (b) municipal managers from other sectors working on the implementation of the PCF, such as health, education, and social assistance (N = 17); and (c) families participating in the PCF (N = 95) (participant characteristics across the municipalities are detailed in Supplementary Table S4a and b). The inclusion criterion for all informants was involvement in implementing or participating in the PCF for at least six months. In each municipality, eligible informants from the municipal PCF teams and families were randomly identified by the research team through a list of PCF professionals working in the municipal teams and through a list of families enrolled in the PCF for at least six months. The random selection of families considered all categories of eligible PCF participants (i.e., pregnant individuals, children up to three years old, and children up to six years old, whose families were beneficiaries of the Continuous Cash Benefit program) to capture the diversity of experiences that families have had with the PCF. Municipal managers from other sectors working on the implementation of the PCF were selected through a convenience sampling process.

Method of approach

The research team hosted a virtual meeting with each municipality to introduce the study and establish the protocols for scheduling virtual or telephone interviews. For selected families, the supervisor and home visitor assigned to each family were contacted and granted authorization from the family to share their contact information with the research team. A research assistant contacted the families by phone to explain the study's purpose and interview procedures, as well as share a virtual copy of the consent form. If the participant agreed to be interviewed, the research assistant scheduled a convenient time for the interview. A similar approach was followed with PCF teams and municipal managers from other sectors working with PCF.

Setting of data collection and sample participation

The 244 interviews were conducted virtually between June 2021 and May 2022 (participant characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Table S4a and b). No participants refused to participate; however, 11 out of 95 families were unable to participate due to challenges in scheduling the telephone interviews.

Data collection

Interview scripts

The interview scripts were guided by the RE-AIM dimensions14,15 (definitions in Fig. 2) and included the following topics: strategies used to implement PCF in the local context, operationalization of home visits and multisectoral actions, process of monitoring and training, workforce characteristics, families’ nurturing care needs, and adaptations/changes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Questions within each topic were tailored to the different program audiences, i.e., PCF municipal teams, families, and municipal managers from other sectors, generating three tailored interview scripts. Because the data collection happened in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the script had specific questions to distinguish the different phases of the pandemic. The scripts were developed in Portuguese and reviewed by researchers with expertise in child development and public health in Brazil and the United States. Interview scripts were pre-tested with a member of the PCF municipal team and one family member that indicated adjustments to the scripts, including literacy and improvements in the flow of the questions.

Fig. 2.

Adaptation of the RE-AIM dimensions to the evaluation of the Criança Feliz Program.

Research team's positionality

The interviews were conducted in Portuguese by four female co-authors (GB, LG, PAP, LDAS), who are native Portuguese speakers. GB is a university faculty member in the US, PAP is a university faculty member in Brazil, and LG and LDAS are doctoral students in Brazil and interested in maternal-child health. They all had prior experience conducting qualitative interviews and had no prior relationship with the participants. Participants were told the goals of the study prior to the interview.

Data management

The data were collected in São Paulo from June to August 2021, in Campo Grande from September to October 2021, in Fortaleza from November to December 2021, in Cuité from January to March 2022, and in Brasília from March to May 2022. After each day of interviews, the research team held debriefing meetings where field notes were expanded, and preliminary data coding and analysis were conducted. Through this approach, when thematic saturation was achieved in each municipality, the sample size was deemed sufficient for that municipality.27 The interviews lasted 40–70 min each, were audio recorded with permission, and transcribed verbatim by a professional Portuguese-speaking service. The original audio recordings were compared to the transcripts by three co-authors (LG, PAP, LDAS) to ensure accuracy.

Analysis of the interviews

We used rapid qualitative methods defined as research designed to be responsive and adaptable to changes in context while the study was ongoing.28, 29, 30 Considering these advantages, our rapid qualitative analysis28 was developed in two phases, as summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Operationalization of the rapid qualitative analysis approach applied to the evaluation of the Criança Feliz Program.

Phase 1 of the thematic data analyses was operationalized in four steps adapted from prior rigorous rapid analysis techniques:28, 29, 30 Step 1: Ensure the data transcript is formatted similarly into a spreadsheet template. All transcripts were summarized into a data table following the RE-AIM dimensions: reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance.14,15 Researchers experienced in qualitative analysis listened to the audio and deductively recorded the transcripts in the spreadsheet template. A senior researcher compared and validated the recorded transcripts summaries. Any questions were discussed and confirmed using the original audio. Step 2: Open code transcript summaries by assigning labels representing barriers and facilitators. The same researchers used an open-coding process31 to inductively label barriers and facilitators. Step 3: Develop a codebook classifying themes by RE-AIM dimensions. The frequency, complementarity, expansion, and divergence of the labelled ideas were used to identify the central themes within each RE-AIM dimension.31,32 Step 4: Iterative refinement of the codebook based on continuous consensus on code usage and structure. The themes were organized into a codebook guided by the RE-AIM dimensions, and the codebook was revised through an interactive process validated at all stages by the four researchers involved in the data analysis (LG, MBG, PAP, GB). The four analytical steps were repeated for each municipality, generating five codebooks. The initial findings were shared with each municipality for feedback between February and March 2023 that promoted research team reflexivity informing the data integration presented in this manuscript.33

Phase 2 of the data analysis involved a deductive use of RE-AIM for data integration, identifying common and distinct themes of implementation barriers and facilitators across municipalities (Fig. 3). Two researchers (GE, GB) reviewed the five codebooks using a local and inclusive approach to consolidate the themes into one comprehensive codebook informed by all municipalities. Weiss34 describes “local integration” as assigning significance to transcript excerpts and “inclusive integration” as connecting transcript excerpts via a coherent story. Quotes from interviews that best represented each central theme were selected to illustrate the results. The best implementation practices from each municipality were selected and reported following the recommendations for specifying and reporting implementation strategies.35 All the authors participated and reached a consensus on the integration of findings into a cohesive and pragmatic set of recommendations guided by RE-AIM.

Role of the funding source

We acknowledge that the funder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and writing of this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Results

A total of 244 in-depth interviews were conducted: 132 members of the municipal PCF team, 17 managers involved in the multisectoral implementation of the PCF, and 95 families (Supplementary Table S4a and b). Table 1 summarizes the 47 themes classified into barriers and facilitators according to the implementation dimensions proposed by RE-AIM: reach (3 themes), effectiveness (5 themes), adoption (5 themes), implementation (23 themes), and maintenance (5 themes). The five themes related to challenges early in and halfway through the COVID-19 pandemic are summarized in Supplementary Table S5.

Table 1.

Matrix of barriers and facilitators to scaling up the Criança Feliz Program across the five municipalities.

| Themes | Barriers (B) and facilitators (F) by municipality |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brasília | Campo Grande | Cuité | Fortaleza | São Paulo | |

| RE-AIMdomain | |||||

| Adoption | |||||

| National and state technical support during scale up | - | B | F | - | - |

| Integration with social assistance services | B | B | B | B | B |

| Questions about PCF scope of work | - | B | B | B | B |

| Integration with existing services | - | - | - | F | B |

| Reach | |||||

| Identification and enrollment of the target population | B | B | B | B | B |

| Development of strategies to identify the target population | F | F | F | F | F |

| Dissemination of awareness materials to the target population | B | B | B | B | B |

| Implementation | |||||

| HIRING MUNICIPAL WORKFORCE | |||||

| Profile of home visitors | F | B | B | B | B |

| Turnover of the PCF team | B | B | - | B | B |

| PCF staff work contracts | B | B | - | B | B |

| Workload of the PCF team | B | B | B | B | B |

| TRAINING | |||||

| Initial Training | F | F | F | F | B |

| Continuing education by external facilitators | - | F | - | - | F |

| Training in partnership with the multisectoral network | - | F | B | - | B |

| SUPERVISION AND MONITORING | |||||

| Supervision focused on reaching visits | B | B | F | B | B |

| Supervisors' workload | B | B | - | B | - |

| Field supervision | B | F | F | F | B |

| Forms for recording data from visits and supervision | B | B | B | B | B |

| HOME VISITS | |||||

| Use of the CCD methodology for home visits | F | F | F | B | B |

| Length time for planning home visits | B | B | B | B | B |

| Curriculum to follow up pregnant individuals | B | B | B | B | B |

| COMPLEMENTARY MULTISECTORAL ACTIONS | |||||

| Multisectoral approach during home visits | B | B | B | B | B |

| Collaboration within the social assistance network | B | B | F | B | B |

| Operation of the MMC | F | F | B | B | B |

| Visibility of the PCF among sectors | F | F | F | F | B |

| FUNDING AND RESOURCES | |||||

| Target-based national funding | B | B | - | B | B |

| Funding for materials, transportation, and other costs | B | F | - | - | B |

| Optimizing funding by integrating into existing structures or services | - | - | - | F | - |

| Effectiveness | |||||

| Limited understanding of PCF goals by families | B | B | B | B | B |

| Perceived improvement on child's development by families and PCF teams | F | F | F | F | F |

| Perceived changes in parenting skills by families and PCF teams | F | F | F | F | - |

| Trust and bond between home visitors and families | F | F | F | F | F |

| Unaddressed social determinants of health | B | B | B | B | B |

| Maintenance | |||||

| Continuity of the PCF as a policy | B | B | F | F | B |

| Co-dependence of national funding | B | B | B | B | B |

| Technical assistance to adapt to municipal contexts | B | B | B | B | B |

| Design of an effective multisectoral approach | B | B | B | B | B |

| COVID-19 pandemic (SeeSupplementary Table S5) | |||||

| Adaptations to the home visit curriculum and delivery | - | F | F | F | B |

| Adaptations of training | - | - | - | - | B |

| Suspension of municipal MMC activities | - | B | - | - | - |

| Increased social vulnerability of families | B | B | B | B | B |

| Continuity of the national funding | - | F | - | - | - |

- indicates not applicable.

Municipality-specific best practices included multisectoral design at local levels (Brasília), a bundle of strategies to achieve and sustain PCF reach (Campo Grande), formal cross-sectoral collaborations to meet families where they are (Cuité), integration of health and social assistance systems to deliver PCF (Fortaleza), and integration of PCF as a complementary service within an existing program in the social assistance sector (São Paulo) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Municipality-specific best practices reported following the recommendations for specifying and reporting implementation strategies.36

| Municipality | Brasília | Campo grande | Cuité | Fortaleza | São Paulo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Local-level multisectoral centers for early childhood | Bundle of strategies to achieve target-based monthly goals | Cross collaborations with the social assistance and education sectors | Integration with an existing home visit strategy in primary care setting | Integration with an existing home visit strategy in the community-based social assistance setting |

| Actor (s) | PCF supervisors and professionals from health, education, and social services at the local levels (i.e., district/neighborhood) | PCF supervisor | PCF supervisors and home visitors | Community Health Workers (CHW), primary health care nurses | PCF supervisors and home visitors |

| Action(s) | Operationalize complementary multisectoral actions at local levels to address the complex social needs identified during PCF home visits | Identify the target population timely to achieve target-based monthly goals by: I. Monitoring participant's age (if a participant ages out, the spot is replaced for a new participant on the waitlist) II. Monitoring whether participants are up-to-date on CADÚNICO III. Disseminating information about PCF to other services and communities |

Build cross-collaborations to deliver the home visit intervention at a place and time responsive to the family availability (“meeting the families where they are”- e.g., conducting visits in the school setting or the primary healthcare unit) | Integrate the early stimulation and parenting training methodology into home visits performed by CHW and supervised by primary health care nurses | Integrate the early stimulation and parenting training methodology into an existing social assistance home visiting strategy that did not previously target pregnant/children |

| Target(s) of the action | Promote cross collaborations among professionals from health, education, and social services offered at local levels | Achieve the reach of the target-based monthly home visits goals, which is required to receive national funds | Promote cross collaborations to deliver home visits at social assistance or childcare facilities to achieve the frequency of home visits | Integrate PCF home visits through both health and social assistance sectors | Offer PCF as a complementary service takes advantage of the existing structure and diffusion |

| Temporality | The first meeting was initiated after four months of PCF initial training of Phase 2 implementation (i.e., December 2021) | Since the beginning of the PCF implementation | Since the beginning of the PCF implementationa | The existing home visit strategy in Primary Care settings (named, “Grow with Your Child”) was implemented in 2014. In 2017, the “Grow with Your Child” was integrated with PCF | The existing home visit strategy (named, Family Social Assistance and Basic Social Protection at Home Services) was implemented in 2010. In 2017, the PCF started to be offered as an additional service to this existing strategy. |

| Dose | Meetings should happen regularly (at least once per month) plus continuing contact among actors if any urgent matters arise | Daily monitoring and monthly dissemination | Follow the PCF national guidelines regarding the number of monthly visits for each participant | CHW must follow the PCF national guidelines regarding the number of monthly visits for each participant | Follow the PCF national guidelines regarding the number of monthly visits for each participant |

| RE-AIM outcome(s) affected | Implementation, Effectiveness, and Maintenance | Reach, Implementation, and Maintenance | Reach and Implementation | Reach and Implementation | Implementation |

| Justification | Promoting a multisectoral approach at local levels has been identified as a major barrier across municipalities implementing PCF | Meeting the target monthly home visits has been identified as a challenge and it is the criterion for receiving the national funding reimbursement | Maintaining the frequency of weekly home visits is a barrier across municipalities implementing PCF | Integrating health and social assistance systems is proven to expand reach, strengthen care, and reduce disparities in early childhood development | Integrating PCF as an additional service within an existing home visiting structure decreased implementation costs with hiring workforce and infrastructure to accommodate them |

This implementation strategy was interrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adoption

Participants in all municipalities reported resistance to adopting the PCF. At the time of PCF launching, the social assistance sector experienced funding cuts, a shortage of professionals, and discontinuities of strategies. In this scenario, the creation of an unprecedented program requiring large financial contributions at the expense of investments in existing social policies became an overarching barrier, as noted by a participant:

“The moment the national government started dismantling the funding transfers for the social assistance sector, they [national government] created the PCF. So, everyone was kind of surprised: “What happened?” They stopped investing in existing social policies and created this new program. At first, it was very challenging to measure the importance of the PCF. Why? Because the social assistance sector was suffering a lot of funding losses, then, all of a sudden, they created a program with a completely different characteristic”.

(Social assistance municipal manager from Cuité)

Interestingly, some participants reported shifting their thoughts about PCF over time as they realized that PCF may bring attention to the long-neglected and underfunded social assistance sector, and as a result, this need would be more politically and financially appreciated. Participants reported the support from the PCF state technical team as a facilitator to promote adoption among social assistance workers. Cuité, the only small municipality in this study, reported that the support from the PCF state technical team in educating municipal social assistance decision-makers and social assistance workers, as well as training supervisors, benefited the delivery of social services in general. However, this support was not perceived as effective in the large municipalities studied.

Across municipalities, the majority of participants felt that PCF should be delivered by the health sector instead of the chosen social assistance sector platform, to overcome the major barrier for PCF adoption. From the participant's perspective, the scope of the program content, with a priority focus on ECD, and the program format to be delivered via home visits aligned with the current primary care home-visiting strategy in the health sector. Many of these participants were unfamiliar with the terminology used in initial training to sensitize social assistance workers, such as cognitive development, early stimulation, neurons, synapses, and assessment of developmental delays. Several interviewees reported that asking questions about the health and development of a child or pregnant person was not the role of social assistance workers, most of whom did not have the background or training in nurturing care and ECD. Similarly, many were reluctant to adopt a program that required the delivery of home visits weekly, as in their current workflow, this strategy was restricted to only severely vulnerable cases.

Due to persisting adoption barriers, the expected integration of the early childhood home visits into the Social Assistance Reference Centers from the Unified Social Assistance System (CRAS/SUAS),36,37 responsible for identifying needs and providing access to welfare benefits and social services, did not happen.

Reach

PCF teams reported initial difficulties in identifying and enrolling the target families, which hindered the achievement of the pre-established monthly number of required home visits. In some municipalities, the CRAS/SUAS provided lists of eligible families. However, due to outdated information on these lists, the PCF municipal teams found it challenging to locate the families. The strategies to overcome the initial failure in locating families included: (a) referral, publicity, and active screening in social assistance service spaces, (b) supplementary lists of eligible families provided by the health and education sectors, (c) active outreach by the home visitors, in visits to neighbourhoods and community, and thorough message apps (i.e., WhatsApp groups). When families were identified, the teams also faced difficulties convincing them to participate. Many families were unaware of the PCF goals and expected to receive a cash benefit for participating in the program. These reasons prevented families from enrolling in PCF and became reach or coverage barriers, as illustrated by the following quote:

“You have many families who refused [to enrol in the PCF] (...). I myself have knocked on many doors where families refused (...) Because many [families] asked right away if they are going to get any [financial] benefits, whether [a new benefit] or the conditional cash transfer was going to be increased a little bit more (…) We explain immediately: “Look, the PCF will not increase your cash transfer benefit. You’ll not gain an extra income.” Because that is what they ask the most; but do we gain anything from it? We explain, “You’ll gain better development for your child. You’ll work on bonding with your child. You’ll have more guidance about something that is happening in your family.” So, the PCF offers that to the family. Many accepted and love the PCF wholeheartedly, but there are many who refused for not having the financial [benefits] in return.”

(PCF coordinator from Cuité)

Strategies for making families aware of the benefits of the PCF included informational leaflets given to families and disseminated in public services and at community events, meetings, and word-of-mouth referrals to the PCF by neighbours and family members. Table 2 outlines the strategies developed by Campo Grande municipality to successfully achieve and sustain PCF reach. These strategies helped PCF to overcome some of the reach barriers, and all but one municipality (São Paulo) eventually reached the planned coverage of monthly home visits at the time of data collection.

Implementation

Hiring the municipal workforce

The high staff turnover and work overload were barriers in all municipalities during the entire period of implementation. Given the nature of national funding and the political uncertainties about the continuity of the PCF, most municipalities offered low salaries and temporary contracts with limited access to labour benefits, such as sick leave and vacation, which are guaranteed by Brazilian laws for employees with permanent contracts, as illustrated below:

“I don’t know, I keep thinking [about the reasons behind the high turnover of home visitors], maybe a [higher] salary that would be a little more attractive (...) better working conditions. We’ve already heard this. I remember a home visitor who said they couldn’t work with the structure we provided”.

(PCF coordinator from Campo Grande)

In addition, contributing factors to work overload reported by participants were the lack of resources for travel to conduct the home visits and the extension of home visitation time schedules to evenings and weekends to meet the monthly number of home visits required, which became a negative feedback loop leading to high staff turnover. The high turnover especially of home visitors was perceived as a barrier not only for the proper management and delivery of the program but also for the lack of continuity in the relationship of home visitors with families, as highlighted in the quote:

“To be a home visitor high school education is required. However, (...) practically all of our home visitors are graduated social workers or educators or psychologists, who are in the job market [seeking a better job opportunity] or waiting to be employed [elsewhere] (...) So, families have already complained [about the high turnover of home visitors]: “Oh dear, just this year about 4–5 home visitors have already been assigned to our family, I can’t stand it anymore.”

(PCF supervisor from Campo Grande)

Training the municipal workforce

The initial training component, i.e., the Care for Child Development (CCD) curriculum and the Home-Visiting Guide for PCF supervisors and home visitors, was perceived as a facilitator. However, local facilitators were sceptical about their qualification to replicate the PCF training cascade and to train about standard operation procedures, which became a barrier to fidelity. For example, in São Paulo, the CCD curriculum was not provided as part of the initial training; instead, only the Home-Visiting Guide was delivered. On the other hand, in Fortaleza, the local facilitators were confident to reproduce the training due to their extensive previous experience with ECD programs.

Another training barrier was the high staff turnover of PCF teams, leading to several professionals working for PCF without proper training. To proactively address this potential barrier, Brasília provided the initial training as one of the steps in the hiring process, allowing for quick replacement by an already-trained professional workforce. The following quote illustrates the tailoring of the training to the local context:

“The training required by the Ministry of Citizenship is just the online basic course available on their portal (…) We tailored what the mandatory training would be here in Brasília. It included the online basic course and an in-depth version conducted by us as follows: candidates for the home visitor and supervisor position have to take the online course and at the end of each day we meet them for two hours when we highlight the most important topics and tailor it to the reality of Brasília. The conclusion of the online training follows a mandatory face-to-face meeting that is part of the hiring process, where we can observe communication skills and personality, which are important because they’ll communicate with families(...) We’ve already done two face-to-face trainings. In the first one, it was right at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic (2019), so we trained around 200 people in small groups (...), about 106 were hired and around 80 remained on the reserve, which was exhausted at the end of the year (2021). In November 2021, we requested a new training, where this in-person supplemental training was offered to 300 people. If I’m not mistaken, 10 were hired immediately and 290 are in the reserve”.

(PCF coordinator from Brasília)

Supervision and monitoring

PCF municipal teams acknowledged the need for sound supervision to ensure the quality of home visits and operationalize complementary multisectoral actions. The ratio of 15 home visitors per supervisor was followed in all municipalities. However, the excessive administrative workload of the supervisors, including too many administrative meetings, forms to fill out, and reports, emerged as a supervision barrier. Several home visitors expressed their frustration with the lack of supportive supervision, as illustrated below:

“There’s one thing that I think [needs to be improved] in the overall program; the supervisors would have to be more committed to do field supervision of home visits, understand? The supervisors need to see if what we [home visitors] are doing has had an effect (...) or could be better worked on (...) Many times we [home visitors] get frustrated, if the supervisor comes here and gives us some strength, maybe we’d get more things for these families”.

(Home visitor from Campo Grande)

Supervisors in Campo Grande and Cuité reported providing field supervision for newly hired visitors, and none reported using standardized protocols to monitor PCF implementation quality. Even though several paper or digital forms must be filled out daily by home visitors and supervisors, it was unclear to the PCF teams how these forms related to program evaluation and monitoring. Likewise, the electronic monitoring system (called e-PCF) was described by PCF teams as too complex. Barriers included technological difficulties and expecting the supervisor or municipal coordinator to enter the information into the system, exacerbating administrative burden.

Home visits

The home visitors appreciated the CCD curriculum20,38 for delivering home visits. While the recommended ratio of home visitors to number of families served (one for every 34 families), was followed in all municipalities, it was considered excessive, contributing to the work overload and poor quality of home visits. Specifically, home visitors reported the required home visit plan to promote quality delivery of home visits, and CCD fidelity was not consistently followed due to a lack of time to write the plan by the home visitors or for the supervisors to review it. The time spent planning activities suitable for different ages and home contexts was reported as a barrier in all municipalities. A successful experience in Fortaleza was the creation of a manual with predefined activities for different age groups. Another common challenge was the low quality of information provided during home visits for pregnant individuals. There were several reports of heterogeneous and sometimes non-evidence-based content in the information provided, as illustrated in the quote of a home visitor:

“Well, I notice that there is a lack of training when it comes to working with pregnant women. There is a significant lack of training because, you see, the PCF national guidelines are for us [home visitors] to provide [early stimulation] activities, right? Finding activities for children is relatively easy. You can find a lot of things, a lot of content, on the internet. But when it comes to pregnant women, it’s not easy to find suitable activities, you know? It’s an area where you need a lot of information because when you open up the dialogue with pregnant women, they have a lot of questions, you know? So, in a way, you find yourself in a situation where you are having a conversation, but you also don’t have much to contribute”.

(Home visitor from Brasília)

The frequency and number of home visits per month emerged as a theme. On the one hand, some families perceived the weekly frequency of home visits as excessive and sometimes felt that the government was “monitoring” them. On the other hand, many families reported that the weekly visits helped them bond with home visitors. Therefore, achieving the expected number of home visits per month was generally a challenge across municipalities. Some home visitors reported confirming the schedule a day prior and families “choosing” to not be at the household at the agreed-upon time. In Cuité, cross-sector collaboration strategies were developed to meet families where they were (e.g., conducting visits in the school setting or the primary healthcare unit) to facilitate achieving the recommended frequency of home visits (Table 2).

Complementary multisectoral actions

PCF teams acknowledged the importance of a functioning municipal Multisectoral Management Committee (MMC) to support the operationalization of complementary multisectoral actions. Campo Grande reported a successful experience pre-pandemic where the cross-sectoral professionals engaged in the MMC were able to enable multisectoral actions focusing on families as well as continuing education targeting PCF teams. However, home visitors and supervisors reported that the MMC disbanded due to the cross-sector overload resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic across the health and education sectors (Supplementary Table S5). Notably, none of the municipalities had a functioning MMC when the data was collected. The quote from a home visitor illustrates the persisting operational challenges for local-level MMC before and during the pandemic.

“I can’t get this family’s entitlement by myself [as a home visitor]. I need the multisectoral collaborators to work together, which still hasn’t been able to get off paper. The MMC has been proposed, but it needs to get off the ground”.

(Home visitor from São Paulo)

The multisectoral approach reported by home visitors included informal recommendations or formal referrals to social, health, and education services. Barriers reported by the home visitors and supervisors were the limited knowledge that they had about services provided by other sectors and the absence of formal mechanisms for referral and coordination. Thus, the multisectoral approach depended on personal relationships between the PCF team, professionals from other sectors, and local partners such as non-profits, churches, and neighbourhood associations. To facilitate cross-sector collaborations at local levels, Brasília successfully developed an innovative multisectoral strategy to systematically operationalize and promote complementary multisectoral actions at local levels (Table 2).

Funding and resources

The funding of the PCF is based on the achievement of the required monthly home visits target, which led PCF teams to feel discouraged and “punished” when the monthly targets were not met. Not meeting the home-visiting targets affected the transfer of national funding, which could lead to delays in payment or be considered a breach of contract, preventing the salary payment of PCF staff.

Regarding the monthly amount of national funding supporting the implementation at local levels, Cuité, the small municipality included, was the only municipality that reported that national funding was sufficient. Strategies to integrate the PCF with existing municipal services were identified as ways to optimize funding and resources. In São Paulo and Fortaleza, the PCF was delivered using existing human resources and infrastructure (Table 2).

To offset costs, municipal funding was required or expected for the PCF to support both infrastructure and resources for implementation, as illustrated in the quote below:

“There is an offset from the municipality, which is [the provision of a car and] a driver (…) The national funds pay the PCF staff, human resources, but these human resources need a [infrastructure such as] a chair to sit, a table, a computer, internet. Everything else is paid [with the national funds provided monthly]. So, there is a tightening of the funding (...)”.

(PCF coordinator from Campo Grande)

However, all the municipalities lacked the financial resources to purchase materials, and only one municipality (Campo Grande) provided transportation for the home visitors between the PCF hub and the households. In Brasília and São Paulo, the lack of transportation led to unequal access to PCF services as a function of household distance from the hub. Due to the long distances in these metropolitan areas, some municipalities prioritized the selection of families living in areas closer to the home visitors’ hub or provided in-person visits only once a month, with additional virtual visits through message apps (i.e., WhatsApp).

Effectiveness

Many families were unaware of the objectives of the PCF visits. In São Paulo, not all families knew that they were receiving PCF home visits, despite being enrolled in the program for at least six months. In spite of this lack of awareness about PCF, families generally perceived positive changes in the children's development and expressed interest in continuing to receive home visits. The appreciation and ways families valued early learning activities and the positive effects on their child's development are illustrated below:

“The PCF was a very good thing for me [as a mother]. By doing the activities together with her, [I noticed that] my daughter developed more because of the program. I liked the PCF a lot (...) [For example], the colours activity when she was doing this, now she already knows what the colour is (...) She says the colour of the tree; she says the yellow colour of the sun”.

(Participating family from Campo Grande)

Notwithstanding variations in the engagement of the families during home visits, the home visitors perceived qualitative changes in parenting skills. Specifically, increased caregivers’ knowledge about child development and the importance of playing, which they saw reflected in an enhanced bond with their children. Home visitors proudly reported that they were agents of change by transforming the future of these families. The trust and bond between the home visitors and the family were built through sensitive and empathetic communication approaches, as well as timely referrals, which were reported to increase PCF effectiveness. The qualitative improvement in parenting skills was shared as follows by a mother participating in PCF:

“The PCF is good for me [as a mother] because they teach me how to better deal with my child. There are times when the child is a little stressed. There are times when he is calmer. There are times when he wants to play with his friends. There are times when he wants to play alone. These are the things that they taught [me]”.

(Participating family from Campo Grande)

On the other hand, the participants collectively indicated that effective PCF implementation requires more training and support for home visitors, along with greater multisectoral collaborations for effective much-needed referrals. The inability of the PCF teams to meet the social service needs identified during the visits was identified as a barrier to effectiveness, as illustrated by the following quote:

“There are so many social needs involved that we cannot reach the final goal of PCF. This is not due to the lack of competence of the professionals or because the PCF is not good, but it’s the structure of society and of the public policies (...) There are various [complex social] vulnerabilities to confront”.

(Social assistance municipal manager from São Paulo)

Maintenance

PCF municipal teams reported concerns about the continuity of the program due to changes in governments with different social development commitments. Most participants considered that institutionalizing the PCF as a national policy approved by Congress would guarantee funding and stability to the program. Fortaleza, Cuité, and Brasília have incorporated the PCF into their municipal ECD policy. However, even in these municipalities, the program still strongly relies on national funding.

The lack of fit of the implementation guidelines provided by PCF manuals, along with the low technical support offered by the PCF national and state teams to intentionally adapt and tailor the implementation processes across contrasting municipal contexts, was listed as a persisting barrier to maintenance. The challenges in incorporating an effective nurturing care multisectoral approach were partially explained by the lack of knowledge about the PCF by the population and among professionals across sectors. The missing nurturing care multisectoral approach was mentioned as an overarching barrier to maintenance and poor program effectiveness of PCF, as illustrated below:

“It’s a program that cannot and will not sustain itself only in the social assistance sector. PCF won’t be sustained due to the lack of integration with the other sectors, especially with the health sector (...) Otherwise, it’s a program doomed to failure, because the social assistance sector will not handle it alone”.

(Social assistance municipal manager from São Paulo).

Discussion

Brazil's decision to scale up the PCF brought the country global recognition as it exemplified the full commitment of a government to fight early childhood inequities through the evidence-based nurturing care approach. By using the RE-AIM framework to document municipal scale-up pathways of the PCF during the acute and subsequent phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, our study helped elucidate how this commitment has unfortunately not translated into the expected results. Barriers and negative feedback loops exacerbated by the pandemic, concentrated in the Adoption, Reach, and Implementation dimensions of PCF implementation, which negatively affected the quality of home visits. Furthermore, these barriers undermined the multisectoral approach to nurturing care that must take place for effective PCF delivery and, ultimately, to improve ECD outcomes. Moreover, the lessons learned through this in-depth implementation science analysis in Brazil were integrated into pragmatic recommendations for improving structural and process attributes necessary to achieve sustainable evidence-based care in large-scale ECD home-visiting programs globally (Box 2).

Box 2. RE-AIM framework recommendations for improving implementation quality of Brazil's Crianca Feliz Program and lessons learned for scaling up and sustaining ECD programs globally.

| Recommendations for Brazil's Crianca Feliz program | Lessons learned for ECD programs globally | |

|---|---|---|

| Adoption | ||

|

|

|

| Reach | ||

|

|

|

| Effectiveness | ||

| Home visits |

|

|

| Complementary multisectoral actions |

|

|

| Implementation | ||

| Hiring municipal workforce |

|

|

| Training |

|

|

| Supervision and monitoring |

|

|

| Funding |

|

|

| Maintenance | ||

|

|

|

ECD, Early Childhood Development; PCF, Criança Feliz Program; SUAS, Unified Social Assistance System; CCD, Care for Child Development (CCD).

Our findings indicated great acceptability of the evidence-based home visits by the participating families, which translated into a perceived improvement in their parenting skills, especially before the pandemic. However, while these perceived benefits favoured reach, they did not translate into ECD impact.11 Unfortunately, the lack of PCF's impact was not a surprise, given that there were major pre-pandemic structural challenges in the operationalization of the home visits, such as the lack of institutional infrastructure to achieve the required number of and length of home visits (i.e., dosage of the intervention), and the lack of a multisectoral approach to tackle the social determinants of health.6 Our findings revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic severely worsened existing pre-pandemic challenges, impacting the three dimensions of the quality of home visitings12: reduced dosage of home visits, modifications in the content (not consistent with the CCD curriculum), and weakened relationships between (i) families-home visitors and (ii) PCF-other sectors. Evidence on the effectiveness of home visits in under-resourced contexts shows that the interplay between those three dimensions is just as important as each unique dimension; for example, dosage and content may have little impact on children's outcomes if the quality of the relationships fostered during the visits is low.12 Indeed, during the acute phase of the pandemic, the dosage of home visits was very low or inexistent, the content delivered did not follow the CCD curriculum, and the relationship between families and their home visitors weakened over time. In addition, the coordination of PCF across sectors, which our interviewees agreed is crucial for the operationalization of the multisectoral nurturing care approach, was severely and negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The fidelity-inconsistent modifications implemented to sustain the program during the pandemic negatively affected the PCF dosage, content, and relationships, creating a strong loss of program “voltage”,22,39 which may explain the reported lack of PCF impact on ECD outcomes.11

Considering the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the regular operations of the PCF (Supplementary Table S5), the lack of effectiveness of the program during a public health emergency should not be regarded as conclusive. Instead, it calls for investing in understanding the critical implementation bottleneck that led to its lack of effectiveness. Our analysis is an important step in this direction as it provides in-depth documentation of key implementation barriers that happened during the acute phase of the pandemic and beyond. Below, we discuss how the PCF teams can address each implementation dimension of the RE-AIM framework to improve sustainability and impact in their settings moving forward.

None of the five municipalities had fully adopted or integrated PCF into the social assistance sector or early childhood systems. Our findings indicate that funding cuts, workforce shortages, and discontinuation of social services generated initial resistance to adopting the PCF. The dismantling of government initiatives in the social assistance sector has been described as a cause of mistrust among sectors40,41 and may explain the resistance to adopting a newly funded initiative such as the PCF. The identified uncertainty about the fit of the PCF scope of work in the CRAS/SUAS has persisted since 2018 as a barrier.6 Nonetheless, in our study, we observed changes in the narrative of some professionals in the social assistance sector who reported PCF as an opportunity to add social value and funding to the sector. This change in the narrative may be due to national and state outreach efforts to promote its adoption by sensitizing social assistance municipal workers about the appropriateness of PCF, as previously reported.6 Although national and state technical support was essential in the adoption of the PCF, their role in supporting quality scale-up was found to be limited, especially in large municipalities. Because adoption can be a function of appropriateness (i.e., perceived fit) and feasibility (i.e., actual fit),42 we hypothesise that large municipalities have a complex structure, which requires adaptations to the PCF protocols to improve its actual fit; however, the national and state technical teams were not equipped to provide support for this adaptation. Implementation science principles highlight the need to continuously adapt interventions to fit local populations, settings, and contexts for effective implementation.43 Therefore, Brazil needs to invest in qualified technical support to ensure the quality and fidelity of PCF implementation,44 while also supporting consistent adaptations across different municipal contexts. Moving forward, it will be important to systematically record and explain the rationale behind adaptations done to improve feasibility as well as integrate PCF within the Unified Social Assistance System (SUAS) policies to promote sustainability across municipalities.45

The extensive reach of home visiting was considered a success by the PCF municipal teams. Expanding the target audience to all families registered in the National Database of Vulnerable Populations (CADÚNICO) facilitated reach. Despite the larger number of Brazilian families that became eligible for the PCF, families were systematically left out or did not receive the expected number of home visits due to long distances from the PCF hub to the homes, combined with a lack of transportation. The literature has consistently shown that extending the reach of behavioural health programs without focusing on eliminating systemic barriers can increase inequities.46 Therefore, to promote equitable access,42 PCF must improve access in hard-to-reach geographical areas and enhance fidelity and sustain delivery of high-quality care to all target populations across settings. Our results indicated the specific need to enhance the PCF evidence-based content for pregnant individuals. Nurturing care interventions during pregnancy are known to facilitate the development of bonds between caregiver and infant, with a favourable impact on postpartum care and infant development.47,48 Thus, improving the quality of PCF for pregnant individuals is necessary for the recommended integration of a life course approach to nurturing care.1,48

Operationalizing the nurturing care approach within PCF was identified as a major weakness, resulting in a low reach of complementary multisectoral actions. Qualitative interviews with families in Brasília found that PCF missed opportunities to enhance the nurturing care environment by addressing unmet social needs, including food insecurity and domestic violence.49 The mechanisms to promote nurturing care multisectoral collaborations within the PCF have been disorganized, and referrals to address household social needs were perceived by families as slow and ineffective. Evidence from low- and middle-income countries indicates the need for well-structured multisectoral actions to strengthen the impact of ECD programs considering the social determinants of health.50, 51, 52 Facilitation strategies to promote multisectoral collaborations may include institutionalizing shared discussion spaces, coordination between the Unified Health System (SUS)53 and the Unified Social Assistance System (SUAS),36,37 identifying and tracking indicators to monitor multisectoral actions, and continuing education training on social determinants of health and equity targeting the multisectoral network. In addition, the experience of Brasília, described in our study, in creating multi-sectoral centres in neighbourhoods can be a model to scale up to other municipalities, especially metropolitan areas and large municipalities.

Implementation barriers, such as the lack of robust training, supportive supervision, and a “smart” monitoring system, were found to be the source of negative feedback loops, negatively affecting the fidelity and quality of the PCF and ultimately reducing program impact. The training, supervision, and monitoring components of the PCF were characterized by a lack of systematization in relation to fidelity to the CCD curriculum. A global literature review found many problems with the implementation fidelity and quality of CCD due to the difficulties in training the workforce and monitoring.21 These findings collectively call for a better understanding of how to improve the implementation fidelity and quality of CCD. In response to this need, a scoping review on CCD and Reach Up mapped the best practices for large-scale implementation of ECD programs in low- and middle-income countries, including strategies for workforce training, supportive supervision, and program monitoring.13 The proactive use of evidence-based implementation strategies and careful consideration of the municipal contexts are needed to enable high-quality PCF implementation. The massive administrative workload of PCF supervisors has hampered supportive supervision. This is concerning because supportive supervision and standardized instruments for supervision, such as the home visit plan and checklists, are positively associated with the quality of ECD programs.13 The lack of supportive supervision and the high turnover of home visitors due to precarious labour contracts generated another negative feedback loop affecting the quality of the PCF. Consistent with these findings, other studies in low- and middle-income countries have confirmed the importance of valuing and retaining trained human resources, as well as regular supervision for quality implementation.50,54 The lack of appropriateness of the PCF monitoring system, including no identification of smart indicators, was found to be a barrier to quality assurance. Therefore, PCF lacks empirical evidence to inform quality improvements, critical for effective scaling and sustainability.13 In this sense, our study makes an important contribution by identifying seven critical implementation activities within PCF—hiring the municipal workforce, training the staff, conducting home visits, multisectoral actions, technical assistance, supervision and monitoring, and funding—which must be monitored for quality improvement. The use of implementation science methods,43 including program impact pathways analysis,55 can be useful to map PCF core functions and implementation mechanisms,56 to guide revision of PCF protocols and enhance adaptations across contrasting municipal contexts.

While the extensive reach of the home visiting was found to be a strength for maintenance, insufficient funding and the lack of sustainable funding were identified barriers. Specifically, Brazil has a history of underfunding or discontinuing successful large-scale programs based on the political context (e.g., the discontinuation of the Bolsa Família Program during Bolsonaro's administration).40,41 Therefore, the continuity and long-term sustainability of PCF was perceived as subjected to the political climate. Evidence from low- and middle-income countries indicates the need for at least five years of funding and commitment of resources for continuing large-scale, long-term workforce retention for ECD programs to provide a greater impact on the return of investments.50 Currently, the national guidelines only consider it “desirable” for municipalities to have funding for PCF implementation. Innovative funding streams, for example, matching funds from the three levels of government, extra reimbursements for high performance in multisectoral actions and fidelity monitoring, and incentives to focus on the population living in hard-to-reach geographical areas, could facilitate high coverage, quality operations, and maintenance. In addition, decentralizing the coordination and leadership of ECD programs to the states and municipalities could be a successful strategy, which has been reported in middle-income countries with similar governance structures as Brazil.2,57,58 Our findings across RE-AIM dimensions can inform critical components of a sustainability plan, including the technical support needed for quality improvement and adaptation to fit different municipal contexts,59 and codesigning strategies for well-structured multisectoral approaches to promote equity.60

Our study is limited because it included only five municipalities in a very large country characterized by sharp inequalities. However, the comparison between municipalities from different geographic regions allowed us to identify similarities and differences in barriers and facilitators as well as understand the complexity of the implementation processes in the scale-up of the PCF, especially in complex contexts such as municipalities located in metropolitan or large population areas. The selection of four capital cities (three metropolises and one large municipality) and one small municipality left medium municipalities without representation in our study. Because capital cities usually have highly contrasting inequities as well as more implementation capacity to scale up policies in Brazil, they have been used to “test” the potential for implementation, scalability, and sustainability of national maternal-child health and nutrition programs61,62; hence, their inclusion is a strength of our study. Additionally, the implementation challenges affecting the quality of PCF were similar in the large and the small municipalities included, which suggests that our findings may have captured structural and process barriers that are likely to be encountered across municipalities independent of population size. Our efforts to represent contrasting municipal scenarios during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond is another strength, but it may have led to recall bias, emphasizing the dramatic challenges during the public health emergency. The evidence-based rapid qualitative analysis methodology28,29 used in our study represents a methodological innovation in knowledge translation in the ECD field. The deductive use of the RE-AIM dimensions—a widely known evidence-based program implementation evaluation framework–14,63 for thematic analysis helped us to identify pragmatic recommendations for optimizing PCF scale-up. Furthermore, extensive interviews with PCF teams and families allowed us to reach thematic saturation.27