Video

Endoscopic closure of a recto-pelvic fistula with a cardiac septal occluder device in a patient for whom other surgical and endoscopic interventions had failed.

Introduction

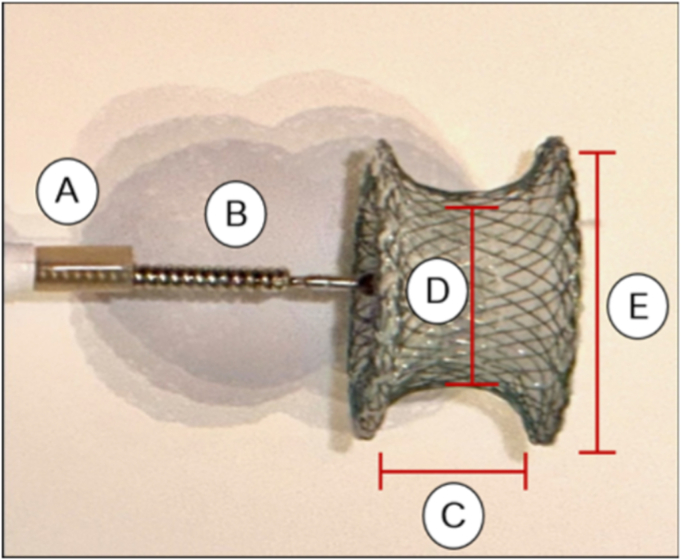

Anastomotic leaks and fistulas following colorectal surgery can be difficult to manage. Endoscopy offers a minimally invasive approach. Established management options include clips, stents, endoscopic suturing, and endoscopic vacuum therapy.1, 2, 3 Although these interventions can be effective, they may prove insufficient in certain cases. The off-label use of cardiac septal occluders (CSOs) in treating GI fistulas has been reported to be effective.4 CSOs are U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved to treat atrial and ventricular septal defects and consist of a self-expandable double disc made from nitinol and interwoven polyester that promotes occlusion and tissue ingrowth (Fig. 1). We present a case demonstrating the successful management of a recto-pelvic fistula using a CSO in a patient for whom other interventions had failed.

Figure 1.

Cardiac septal occluder device. A, Sheath. B, Delivery cable. C, Waist length. D, Device size (waist diameter). E, Disc diameter.

Case

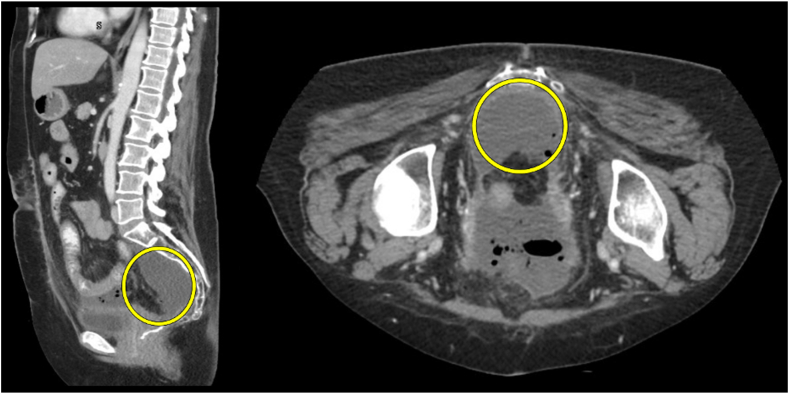

A 63-year-old woman with a history of rectal adenocarcinoma status postneoadjuvant chemoradiation and lower anterior colon resection with creation of a diverting ileostomy with a stapled coloanal anastomosis 2.5 cm from the anal verge 2 years prior was referred for evaluation of a recto-pelvic fistula. Her postoperative course was complicated by a presacral fluid collection, fistula, and persistent rectal drainage (Figs. 2 and 3). The collection was treated with multiple courses of antibiotics and percutaneous drainage twice. Surgical suture ligation of the fistula with drainage of purulent material from the collection decreased the size of the collection significantly (Figs. 4 and 5; Video 1, available online at www.videogie.org); however, the fistula failed to close. Multiple attempts at fistula closure with argon plasma coagulation (APC) and endoscopic suturing, along with over-the-scope clips, also failed to close the fistula permanently. The patient denied significant pelvic discomfort and recurrent signs of infection and only endorsed persistent rectal drainage. Complaints of rectal discharge improved with fistula closure in the short term; however, they recurred after the fistula failed to close permanently with the endoscopic closure. Therefore, the decision was made to perform fistula closure with a CSO and plan for percutaneous collection drainage if the patient became symptomatic.

Figure 2.

Chronic presacral fluid/air collection identified within the yellow circles.

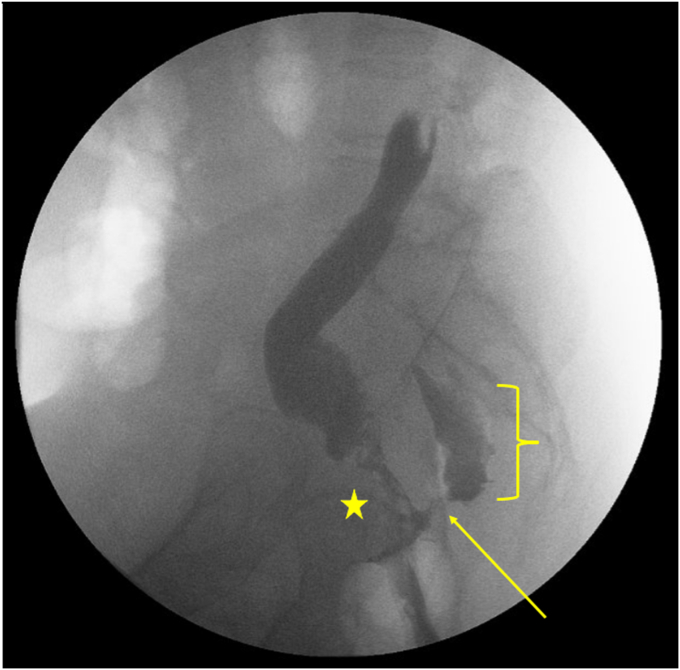

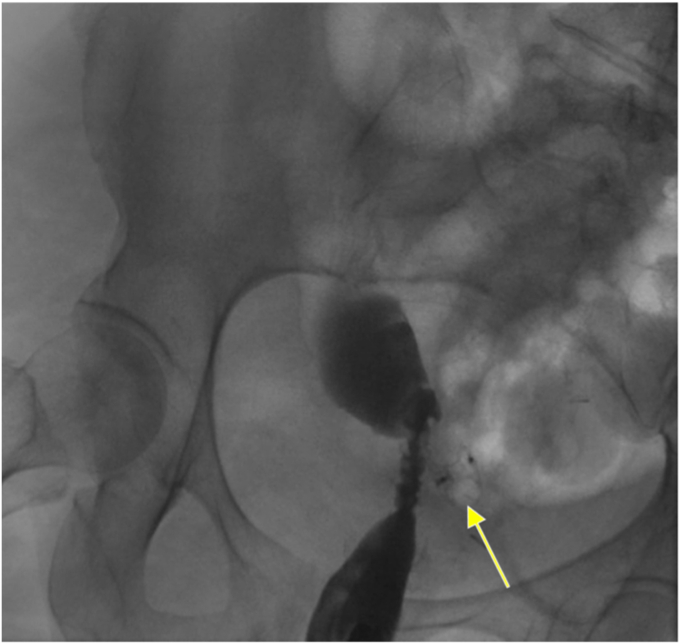

Figure 3.

Fluoro-gastrografin enema showing evidence of a persistent recto-pelvic anastomotic fistula with contrast pooling in the presacral fluid collection. The surgical coloanal anastomosis is identified to the right of the star, the fistula can be seen above the arrow, and the presacral fluid collection is seen within the bracket.

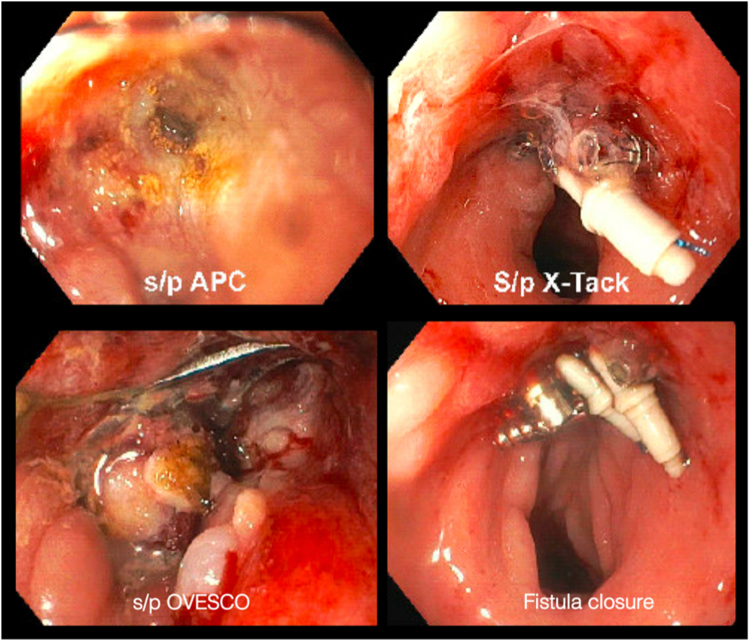

Figure 4.

Failed fistula closure attempts using argon plasma coagulation and endoscopic suturing with over-the-scope and through-the-scope clips.

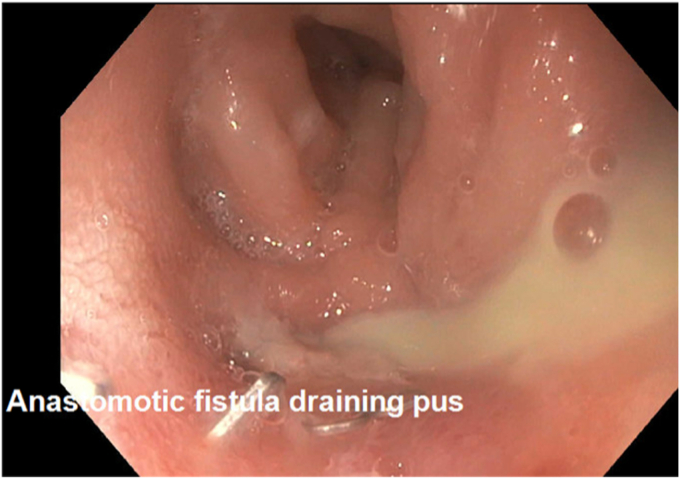

Figure 5.

Anastomotic fistula draining purulent fluid after interventional radiology attempts at percutaneous drainage.

Method

First, a CSO delivery system was created (Video 1). A therapeutic gastroscope equipped with the delivery system was then advanced to the level of the recto-pelvic fistula. Prior to deployment of the CSO, an extraction balloon catheter was passed through the fistula to estimate the fistula size and ensure easy traversability. The CSO was then deployed across the fistula under endoscopic guidance without fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 6). No antibiotics were given during CSO deployment, and because of multiple prior procedures with APC and repeat visualization of the fistulous opening, repeat APC was not pursued during CSO placement and an ultraslim transnasal endoscope was not used for inspection. The patient was advised to avoid constipation, but no specific diet recommendations were made. Following the procedure, the patient reported resolution of her rectal drainage on clinical follow-up at 11 months, and tissue ingrowth into the CSO and complete occlusion of the fistula were visualized during endoscopic follow-ups, respectively (Fig. 7, Video 1). While it was not anticipated, repeat imaging and external drainage catheter placement were planned if the patient endorsed any more pelvic discomfort or infectious symptomatology related to the pelvic collection.

Figure 6.

Confirmation of successful closure of the recto-pelvic fistula using the cardiac septal occluder device seen on a fluoro-gastrografin enema without extravasation of contrast. The cardiac septal occluder device is seen above the arrow completely occluding the recto-pelvic fistula.

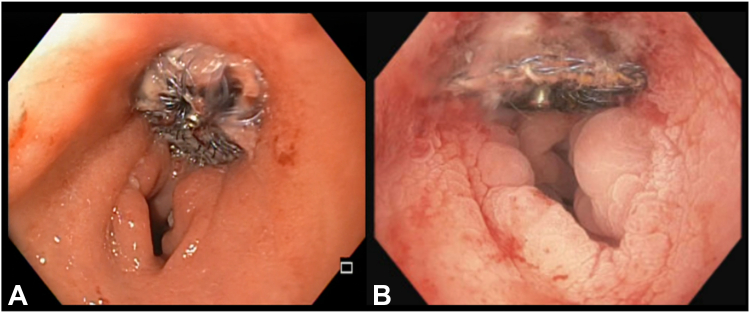

Figure 7.

Tissue ingrowth of the cardiac septal occluder device seen on sigmoidoscopy 4 months (A) and colonoscopy 7 months (B) after deployment.

Discussion

This case highlights the use of a CSO in managing a recto-pelvic fistula and adds to the literature supporting its use in the GI tract. Although there are numerous options for endoscopic management of GI fistulas, including endovacuum therapy and EUS-guided interventions, some require multiple sessions and appropriate angulation of the fistulous opening and have a high recurrence rate. CSOs offer an alternative for patients who fail traditional endoscopic therapies for fistula closure. Further studies are needed to validate its efficacy and safety in this context.

Disclosure

Dr Singh is a consultant for Apollo Endosurgery. The other authors did not disclose any financial relationships.

Supplementary data

Endoscopic closure of a recto-pelvic fistula with a cardiac septal occluder device in a patient for whom other surgical and endoscopic interventions had failed.

References

- 1.Singh R.R., Nussbaum J.S., Kumta N.A. Endoscopic management of perforations, leaks and fistulas. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:85. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2018.10.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manta R., Magno L., Conigliaro R., et al. Endoscopic repair of post-surgical gastrointestinal complications. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manta R., Caruso A., Cellini C., et al. Endoscopic management of patients with post-surgical leaks involving the gastrointestinal tract: a large case series. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:770–777. doi: 10.1177/2050640615626051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Moura D.T.H., Baptista A., Jirapinyo P., et al. Role of cardiac septal occluders in the treatment of gastrointestinal fistulas: a systematic review. Clin Endosc. 2020;53:37–48. doi: 10.5946/ce.2019.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Endoscopic closure of a recto-pelvic fistula with a cardiac septal occluder device in a patient for whom other surgical and endoscopic interventions had failed.

Endoscopic closure of a recto-pelvic fistula with a cardiac septal occluder device in a patient for whom other surgical and endoscopic interventions had failed.