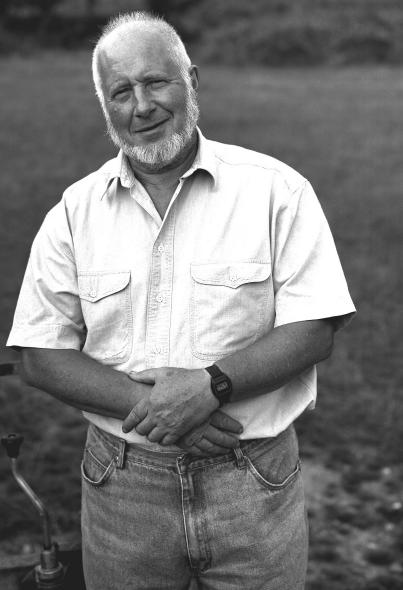

Born in 1927, Julian Tudor Hart (Figure 1) grew up in a home that served, among other things, as a transit camp for anti-fascist refugees from Continental Europe. His mother, Dr Alison Macbeth, was a member of the Labour Party. His father, Dr Alexander Tudor Hart, belonged to the Communist Party and represented the South Wales Miners' Federation in a dispute over medical care; later he volunteered as a surgeon for the International Brigades fighting against General Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Despite the efforts of his parents to discourage him from entering medicine, Julian's ambition was to be a general practitioner in a coal mining community; but as a medical student in Cambridge and London he recognized the dismal reputation of general practice as the least satisfying and most frustrating field of medicine. If serious-minded students were to be turned to this kind of work, the intolerable features of general practice had to modified.1 New recruits to medicine, he argued, should cultivate disciplined anger against the attitudes and circumstances that impeded effective delivery of medical science to sick people.2 These and subsequent opinions were doubtless coloured by his Marxist convictions. Later in life he expanded on his critique of the medical profession, declaring that medical education was `training the wrong people, at the wrong time, in the wrong skills and in the wrong place'.3

Figure 1.

Julian Tudor Hart, 1995 [Photograph by Nick Sinclair from the photograph collection of the National Portrait Gallery]

Hart graduated in 1952 and after hospital posts and experience in urban general practice he became involved in epidemiological research, first with Richard Doll and later with Archie Cochrane. At that time, the late 1950s, there was a growing perception that each general practice should be regarded as a population at risk4 and that general practitioners needed to couple their traditional curative medicine with the methods and techniques of the epidemiologist and the medical officer of health (in conjunction with colleagues in allied health professions). At the same time, four large changes were underway in medicine. First, the bioethics movement was encouraging patients and their families to share the overall responsibility for healthcare. Secondly, the family practice movement was emphasizing the holistic dimensions of healthcare, including lifestyle factors. Thirdly, the preventive medicine movement was starting to develop guidelines for practice.5 And, fourthly, the advent of new diuretics and sympathetic blocking agents was making the treatment of hypertension easier and freer from side-effects.6 In 1961 he moved to Glyncorrwg, South Wales, and set up a research practice.7

GLYNCORRWG

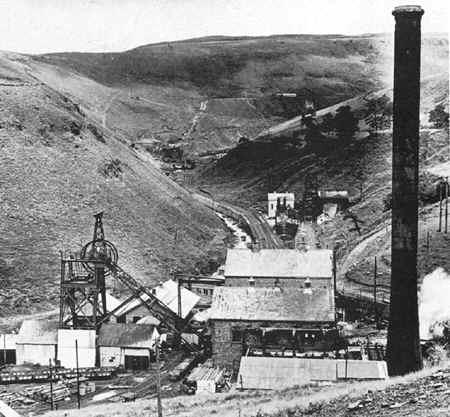

Glyncorrwg (Figure 2) was a small coal mining community in the Afan Valley. Within 4 years of Hart's arrival, almost all of the village was registered with the practice together with 200 from other villages in the valley. This gave a practice population of 1900. At that time, the village had a vigorous social, cultural and commercial life, with three working men's clubs, four pubs, a church and five competing chapels, branches of the Labour and Communist Parties, one cricket, three soccer and two rugby teams, a betting shop, a café, a hairdresser, a newsagent, an ironmonger, two drapers, three sweet shops and four grocers.8 However, between 1966 and 1986 Glyncorrwg saw a collapse of its basic industry which together with competition from supermarkets and hypermarkets, almost wiped out the small shops and accelerated the decline of religious, political and cultural groups. By 1986 the church and four chapels survived with dwindling congregations but the village was now down to one pub, one newsagent, and two grocers. The male unemployment rate had risen and the male population of working age (16–64) had declined. Nevertheless, there was little crime, venereal disease was almost absent and the only addictive drugs were alcohol and tobacco—though both these were widely used. Primary care in the valleys was delivered in general practices or not at all.9

Figure 2.

Glyncorrwg Colliery, 1953 [Reproduced from www.welshcoalmines.co.uk with permission]

IDENTIFYING AND ATTACKING ILL-HEALTH

One of Hart's first moves was to examine local deaths—not at population level, in the manner of public health, but case by case. In his view, a search for avoidable factors in individual deaths was the most stringent form of self-criticism available to any clinical team. Of the consecutive 500 deaths audited between 1964 and 1985, 233 were thought to have avoidable causal factors; and, of these, 59% were attributed to the patient, 20% to the general practitioner, 4% to hospitals and 17% to others.10

Screening for chronic illness revealed that 23% of patients in the practice had lung disease (peak expiratory flow half or less of expected), 18% were obese (body mass index over 30) and 11% were hypertensive (diastolic pressure >100 mmHg in those under 40 years or 105 mmHg in those 40 years and older).8

Like other pioneers such as Will Pickles of Wensleydale11 and William Budd of North Tawton,12 Hart realized that he and his team needed to know the local population well and to keep accurate records. This was highlighted when rubella vaccination became available in 1969. The national policy was to immunize girls aged 11–13 at school. Hart knew that school absence was about 20% on any one day, so he wrote to the medical officer of health for the district, asking for a list of Glyncorrwg girls who had not been immunized so that he could contact them. The reply came, `I can give you a list of the ones we did, but how am I to know the ones we didn't?'. Hart saw that, for interventions not prompted by patient demand, what the practice needed was exactly that—not a list of acts but a list of omissions.8 Between 1982 and 1986 the percentage of women in Glyncorrwg who had had cervical smears in the past 5 years increased from 20% to 83%, and Hart's explanation was that `we knew the names and addresses of our whole population, we knew who had a uterus and who hadn't, and we knew who answered the back door because she owed money to a debt collector.'8

Hart also looked at the way patients consulted their general practitioners. Although he did not reject the Oslerian paradigm whereby patients initiate episodes of medical care, he came to see patients as joint producers (in conjunction with the professional) rather than as customers or consumers. The `products' of this transaction were solutions to healthcare problems. His perception was that, for people to change their habits and eat more thoughtfully, use their leisure time more vigorously or accept a life of pill-taking, they needed a stronger incentive than a brief chat in the consulting room and a leaflet to read.13 Doctors, he argued, must accept patients as equal or even dominant partners; without this, health production will not follow. He likewise declared that, for medical science to be applied effectively to whole populations, it must be democratized.14

As an example, Hart described the ongoing care of one of his patients—a coal miner who at age 36 had been hypertensive, hypercholesterolaemic, obese and a heavy drinker. This patient became diabetic 19 years later.

`For the staff at our health centre it was a steady unglamorous slog through a total of 310 consultations (over 26 years). For me it was about 41 hours of work with the patient, initially face to face, gradually shifting to side by side. Professionally, the most satisfying and exciting things have been the events which have not happened; no strokes, no coronary heart attacks, no complications of diabetes, no kidney failure with dialysis or transplant. This is the real stuff of primary medical care.

`Who was responsible for maintaining the health of this patient? I was, he was, and so were a lot of other people who helped me—orthopaedic surgeons (he had a fractured leg from the mine), renal physicians, radiologists and radiographers, laboratory technicians, nurses, etc, and his wife, sons, daughters, mates at work and drinking companions. We were not always successful, and all of us have counter-produced; but his present state of health is a social product of work done well or badly by many people, but usually starting from the general practitioner in joint consultation.'8

This sort of anticipatory care, he believed, could in future be facilitated by a properly equipped and staffed primary care service in which the general practitioner was backed by trained practice managers with computer-assisted clinical records. However, general practitioners should not be obliged to do this kind of work.9

Today, there is much evidence to support Hart's approach. For advice on health lifestyles, people do tend to consult general practitioners rather than other experts,15 and the continuity of care in general practice is recognized to favour prevention.16,17 (In Glyncorrwg, Hart found his local health authority unable to grasp the necessity for continuity in staffing to secure adherence to prevention programmes, so he employed and trained his own staff.) Although people of low socioeconomic status are the least likely to adopt preventive health strategies, the disparities do not arise from discrimination in general practice: audiotaped consultations have shown no differences in the advice given to different social groups.18 Hart's policy of working with the patient is supported by studies of diabetic control.19,20 Preventive care is helped by generous allocations of time;21,22 in Glyncorrwg the mean consulting time rose from 7 minutes in 1965 to 8 minutes in 1970 and 10 minutes in 1987.23

Although Hart's primary research interest was hypertension, he judged that the anticipatory and preventive approach could not be applied to this condition alone: other risk factors for heart disease and stroke had to be considered, and he adopted techniques of audit that made it increasingly difficult to bypass the time-consuming but necessary follow-up commitments. Better medical care, he said, demands more time and more labour.8 At present in the UK, consultations tend to be shortest in deprived areas, and strategies to deal with the resultant disparities of care might include a local increase in the ratio of general practitioners to population, removal of financial disincentives to long consultations, and strengthening of health promotion and community health services.24

OUTCOME

One of Hart's innovations in Glyncorrwg was the formation of a health centre committee with a public health focus. The committee made positive proposals and organized public pressure for their adoption. It also made the village aware of such matters as local black spots for road fatalities, the illegal selling of alcohol and cigarettes to minors and the danger of accidents to children from playing in derelict industrial buildings. The committee was elected at an open community meeting in 1975, with reserved places for some groups which Hart thought needed to be represented— mothers of young children, a local teacher, local health workers, a pensioner, a shift-worker, and so on. It met monthly, discussing and taking decisions on such issues as the frequency of general practitioner visits to the housebound elderly; provision of sleeping accommodation and meals for mothers accompanying their children in hospital; collection of patient opinions on the practice and on the effects on patients of prescription charges; training in resuscitation; campaigns for a local swimming pool (which failed) and for safe cycle and running tracks away from main roads and against closure of the local ambulance station (which succeeded); hospital waiting lists; and a continuing process of explanation and discussion of how the National Health Service is supposed to work, how it actually works, and how it might work in the future.8

As heavy industry collapsed, the first 10 years of the mortality audit showed a decline in male deaths outside the home, a drop in male smoking-related mortality from 43% to 30% and a rise in female smoking-related mortality from 10% to 26%.10

The Glyncorrwg age standardized mortality ratio in 1981–1986 was lower than in a neighbouring village which did not have a developed case finding programme. In 116 screened hypertensive patients, the group mean blood pressure fell from 186/110 mmHg before treatment to 146/84 mmHg at 1987 audit, and 25 years of audited screening showed a decline in the proportion of smokers from 56% to 20%—but no change in body mass index or total cholesterol.23

Watt has commented that, although not a rigorous scientific experiment, Hart's is still the only evidence we possess concerning the long-term effect of a system of care delivering evidence-based medicine with careful targeting of high risk patients whereby doctors work closely with nurses and receptionists using high-quality records and audit to measure what has been achieved and what has not.25

THE INVERSE CARE LAW

It was while working at Glyncorrwg that Hart developed his famous inverse care law—`The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served'. This law, he argued, `operates more completely where medical care is most exposed to market forces, and less so where such exposure is reduced. The market distribution of medical care is a primitive and historically outdated social form, and any return to it would further exaggerate the maldistribution of medical resources'.26

Reflecting on the continuing reality of the `law' after the passage of three decades, Hart identified some of the reasons why corrective action has been so difficult. One is that no market will ever shift corporate investment from where it is most profitable to where it is most needed.27 Another is `therapeutic nihilism' about the ability of clinical medicine to improve the health of the public.28 To these points Watts added that, in the British National Health Service, a major obstacle to progress is the absence of data quantifying the excess costs of clinical effectiveness in deprived areas; until such information is available, he says, deprived areas will continue to lose out in resource distribution.25

Needs and care can at times be difficult to quantify, but the continuing relevance of the inverse care law is shown by data on such issues as health expenditure, the management of depression, access to services, length of consultation in general practice, dental care for children and longitudinal care of people with hypertension.29–34

Looking back, Hart castigates himself for having begun in Glyncorrwg as an authoritarian paternalist. It was only through blind turns and false passages that he came to value cooperation with patients. The experience also honed his political conclusions about healthcare. The government of the day interpreted his Glyncorrwg experience as a lesson in good healthcare organization, and he came to be regarded as an `industrialist'—a label still attached to him by opponents of industrialization. But the industralizers, he says, tend to agree only with his views on organization, rejecting all else as `completely mad' (Personal communication). The British National Health Service, he feels, is a production system but, just because it produces measurable value it need not (and should not) try to produce market commodities. He fears that the product will be measured in terms of process rather than good and cost-effective outcomes. Also, the real currency of primary care is time—essential if doctors are to search for needs, create new understanding, or convert patients themselves into producers.35 Going to a doctor is not like eating ice cream.36

CONCLUSION

In Julian Tudor Hart's analysis, the inverse care law is a manifestation of dehumanized market economics. It could be unmade by a rehumanized society, and in medicine part of the answer lies in recruitment of more students who are socially mature.37 Hart himself exemplified this approach as the personal doctor who knew each of his patients well, saw them in their family and community context, and worked with them over many years to reverse risks and prevent complications.25

Human ecology has been defined as the study of the interaction of human beings with themselves, with living organisms and with their shared environments.38 Just as there are waterborne and airborne diseases there are culture borne diseases. Hart's work in Glyncorrwg has given us a way to approach these diseases and their complications, and to tackle injustice in healthcare.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Julian Tudor Hart, currently External Professor at the Welsh Institute for Health and Social Care, University of Glamorgan, for commenting on a draft of this article.

References

- 1.Hart J T. General practice today. Lancet 1950;i: 737–8 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart J T. Relation of primary care to undergraduate education. Lancet 1973;ii: 778–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart J T. George Swift Lecture. The world turned upside down: proposals for community based undergraduate medical education. J R Coll Gen Pract 1985;35: 63–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott R. The Eleventh James Mackenzie Lecture. Practitioner 1965;194: 137–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aita V, Crabtree B. Historical reflections on current preventive practice. Prev Med 2000;30: 5–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smirk H. Advances in the treatment of hypertension. Practitioner 1960;185: 471–82 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas H. Medical research in the Rhondda valleys. Postgrad Med J 1999;75: 257–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart JT. A New Kind of Doctor: the General Practitioner's Part in the Health of the Community. London: Merlin, 1988

- 9.Hart JT. Community general practitioners. BMJ 1984;288: 1670–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart JT, Humphreys C. Be your own coroner: an audit of 500 consecutive deaths in general practice. BMJ 1987;294: 871–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moorhead R. Pickles of Wensleydale. J R Soc Med 2001;94: 536–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moorhead R. William Budd and typhoid fever. J R Soc Med 2002:95: 561–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart JT, Stilwell B, Gray JAM. Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: a Workbook for Primary Care Teams. London: Faber & Faber, 1988: 85

- 14.Hart JT. James Mackenzie Lecture 1989: reactive and proactive care. Br J Gen Pract 1990;330: 4–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moorhead RG. Who do people talk to about healthy lifestyle? A South Australian survey. Fam Pract 1992:4: 472–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steven ID, Dickens E, Thomas SA, Browning C, Eckerman E. Preventive care and continuity of attendance. Is there a risk? Med J Aust 1998;27(suppl): S44–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIsaac WJ, Fuller-Thomson E, Talbot Y. Does having regular care by a family physician improve preventive care? Can Fam Physician 2001;47: 945. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiggers JH, Sanson-Fisher R. Practitioner provision of preventive care to patients of different socioeconomic status. Soc Sci Med 1997;44: 137–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolpert HA, Anderson BJ. Management of diabetes: are doctors framing the benefits from the wrong perspective? BMJ 2001;323: 994–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware CE, et al. Patients' participation in medical care—effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 1988;3: 448–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson A. Consultation length in general practice: a review. Br J Gen Pract 1991;41: 119–22 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howie JG, Porter AM, Heaney DJ, Hopton JL. Long to short consultation ratio: a proxy measure of quality of care for general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1991;41: 48–54 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart JT, Thomas C, Gibbons B, Edwards C, Hart M, Jones J et al. Twenty five years of audited screening in a socially deprived community. BMJ 1991;302: 1509–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furler JS, Harris E, Chondros P, et al. The inverse care law revisited: impact of disadvantaged location on accessing longer GP consultation times. Med J Aust 2002;177: 78–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watt G. The inverse care law today. Lancet 2002;360: 252–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;i: 405–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hart JT. Why are doctors so unhappy? Unhappiness will be defeated when doctors accept full social responsibility. BMJ 2001;322: 1363–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart JT. Commentary: Three decades of the inverse care law. BMJ 2000;320: 18–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malcolm L. Major inequities between district health boards in referred services expenditure: a critical challenge facing the primary care strategy. NZ Med J 2002;115: U273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chew-Graham CA, Mullin S, May CR, Hedley S, Cole H. Managing depression in primary are: another example of the inverse care law? Fam Pract 2002;19: 632–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovett A, Haynes R, Sunnenberg G, Gale S. Car travel time and accessibility by bus to general practitioner services: a study using patient registers and GIS. Soc Sci Med 2002;55: 97–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stirling AM, Wilson P, McConnachie A. Deprivation, psychological distress and consultation length in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51: 456–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones CM. Capitation registration and social deprivation in England. An inverse dental law? Br Dent J 2001;190: 203–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearse E, Hannaford PC, Taylor MW. Gender, age and deprivation differences in the primary care management of hypertension in Scotland: a cross sectional database study. Fam Practice 2003;1: 22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hart JT. Two paths for medical practice. Lancet 1992;340: 772–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart JT. Expectations of health care: promoted, managed or shared? Health Expectations 2003;1: 3–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hart JT. Clinical judgment. J R Soc Med 2000;93: 605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murrell T. The GP as human ecologist. Aust Fam Phys 2001;10: 991–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]