Abstract

In C. elegans, divergent Hedgehog-related (Hh-r) and Patched-related (PTR) proteins promote numerous processes ranging from epithelial and sense organ development to pathogen responses to cuticle shedding during the molt cycle. Here we show that Hh-r proteins are actual components of the cuticle and pre-cuticle apical extracellular matrices (aECMs) that coat, shape, and protect external epithelia. Different Hh-r proteins stably associate with the aECMs of specific tissues and with specific substructures such as furrows and alae. Hh-r mutations can disrupt matrix structure. These results provide a unifying model for the function of nematode Hh-r proteins and highlight ancient connections between Hh proteins and the extracellular matrix.

Introduction

C. elegans has no ortholog of Hedgehog (Hh) or most of its canonical signaling partners. However, the C. elegans genome encodes more than 60 secreted proteins thought to be evolutionarily related to Hh across four families: Warthog (WRT), Groundhog (GRD), Groundhog-like (GRL), and Quahog (QUA) (Bürglin 1996; Bürglin and Kuwabara 2006; Hao et al. 2006c; Bürglin 2008a; b). Some of these proteins contain a HOG/Hint domain similar to the autocatalytic C-terminus of Hh. However, none have any sequence similarity to the signaling domain of Hh; instead, they contain nematode-specific cysteine domains for which they are named (WRT, GRD, GRL, or QUA). The PTR protein family, related to the Hh receptor in other systems, has undergone coincident expansion in nematodes, suggesting that Hh-r and PTR proteins act together in some way (Zugasti et al. 2005; Bürglin and Kuwabara 2006; Zhang and Beachy 2023). There is evidence for potential signaling roles of a few Hh-r and PTR proteins, though the relevant downstream pathways remain unclear (Lin and Wang 2017; Kume et al. 2019; Templeman et al. 2020; Chiyoda et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2023; Emans et al. 2023). PTR proteins can also affect Hh-r endocytosis (Zugasti et al. 2005; Chiyoda et al. 2021). Hh-r and/or PTR proteins have been tied to numerous functions in development and physiology, but the most abundant evidence points to roles in the organization of apical extracellular matrices (aECMs) (Bürglin and Kuwabara 2006; Cohen and Sundaram 2020).

C. elegans external epithelia are covered by a collagenous cuticle aECM that is shed and replaced at each larval molt (Page and Johnstone 2007). Each cuticle is preceded by a transient pre-cuticle aECM that helps pattern the new cuticle and allows proper release of the old cuticle (Cohen and Sundaram 2020). Like cuticle and pre-cuticle genes, many Hh-r genes are expressed in external epithelia and show an oscillatory pattern of gene expression during the molt cycle (Hao et al. 2006c; Hendriks et al. 2014; Meeuse et al. 2020). QUA-1 (the only member of the QUA family) binds cuticle and loss or knockdown of qua-1 and several wrt or ptr genes causes cuticle or molting defects (Zugasti et al. 2005; Hao et al. 2006a; b; Baker et al. 2021). Recently, we reported that loss of ptr-4 disrupts organization of the pre-cuticle aECM, which can explain the ptr-4 mutant phenotypes (Cohen et al. 2021). Fung et al. (2023) also reported that GRL-18 localizes transiently to developing cuticle pores over sensory glia, suggesting GRL-18 could be a glial socket pre-cuticle factor. Finally, Chiyoda et al. (2021) reported a transient embryonic expression pattern for GRL-7 that we found reminiscent of known pre-cuticle components (Vuong-Brender et al. 2017; Birnbaum et al. 2023). Here we demonstrate that these and other Hh-r proteins are stable, tissue- and substructure-specific components of the cuticle or pre-cuticle.

Methods

C. elegans Maintenance and Strains

Animals were grown at 20° C under standard conditions (Brenner 1974). Strains used are shown in Table S1. GRL-2 and WRT-10 fusions were made by Suny Biotech (Fuzhou, China) using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. GRL-18 and GRL-7 fusions were kind gifts of Maxwell Heiman (Harvard U.) and Masamitsu Fukuyama (U. Tokyo).

Confocal microscopy

Confocal images were captured with a Leica TCS DMi8 confocal microscope and Leica Las X Software. Worms were immobilized with 10 mM levamisole in M9 buffer and mounted on 2% agarose pads supplemented with 2.5% sodium azide. L4 animals were staged based on vulva morphology (Mok et al. 2015). For each strain, at least n=10 animals were imaged at each stage shown in the figures and in 24-hour adults.

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP)

FRAP experiments were conducted using a Leica DMi8 laser scanning confocal microscope and the Leica Las X Software FRAP module. Pre and post bleach laser powers ranged from 12% depending on protein target. A 3μm × 3μm ROI was designated for each experiment. 20 pre-bleach frames were captured at 1 frame/ 0.4s, followed by 20 to 30 bleaching frames at 100% laser power power at 1 frame/ 0.4s depending on target. Recovery timecourse was 3 minutes with image capture at a rate of 1 frame/ 2 seconds for 90 recovery frames total. Replicate FRAP data was analyzed in Graphpad Prism software by fitting one-phase association curves to the data reliant on the following formula Y = Y0 + (Plateau-Y0)*[1–ê(2Kx)]. Mobile fraction was calculated by subtracting the Y0 value from Plateau.

Alae observation

The alae in late L4 and young adult worms were observed by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and by epifluorescence after staining with lipophilic DiI (Biotium) as in (Schultz and Gumienny 2012). Briefly, young adult worms were washed and pelleted from plates with M9 buffer and incubated in 30 μg/ml DiI shaking at 20 °C for 3 hours. After washing again with M9, worms were allowed to recover on OP50 seeded NGM plates for at least 30 minutes before mounting and imaging. Worms were observed with a Zeiss Axioskop (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) with an attached Leica DFC360 FX camera. Images were acquired using the software package Qcapture (Qimaging). Image cropping, scaling, and adjustment was handled in ImageJ.

Results and Discussion

To test if Hh-r proteins are found within the aECM, we systematically evaluated the localization patterns of 4 Hh-r proteins (GRL-2, GRL-7, GRL-18, and WRT-10) in larvae and adults using endogenously tagged fluorescent reporters. GRL-2 and GRL-18 fusions permanently labelled the cuticle of specific tube cells (Figures 1 and 2), while GRL-7 and WRT-10 fusions transiently labelled distinct substructures within epidermal and seam pre-cuticles (Figures 3 and 4). WRT-10 also labelled the pre-cuticles of specific interfacial tubes (Figure 4). The tissue distribution of each Hh-r protein was consistent with each gene’s reported transcriptional pattern based on transgenic reporters and/or single cell RNA sequencing (Soulavie et al. 2018; Packer et al. 2019; Fung et al. 2020, 2023). We conclude that Hh-r proteins label aECMs of those cells in which they are expressed.

Figure 1. GRL-2 is a tube specific cuticle component.

A. SfGFP::GRL-2 schematic. SfGFP was inserted immediately following the signal sequence (SS). B. Cartoon summary of expression pattern. C. SfGFP::GRL-2 labelled the cuticle of the excretory duct and pore tubes and the amphid and phasmid socket glia at all larval stages and in adults. D. It could also be detected in shed cuticles after a molt. E. SfGFP::GRL-2 showed no recovery after FRAP (n=12). See Table 1 for analysis.

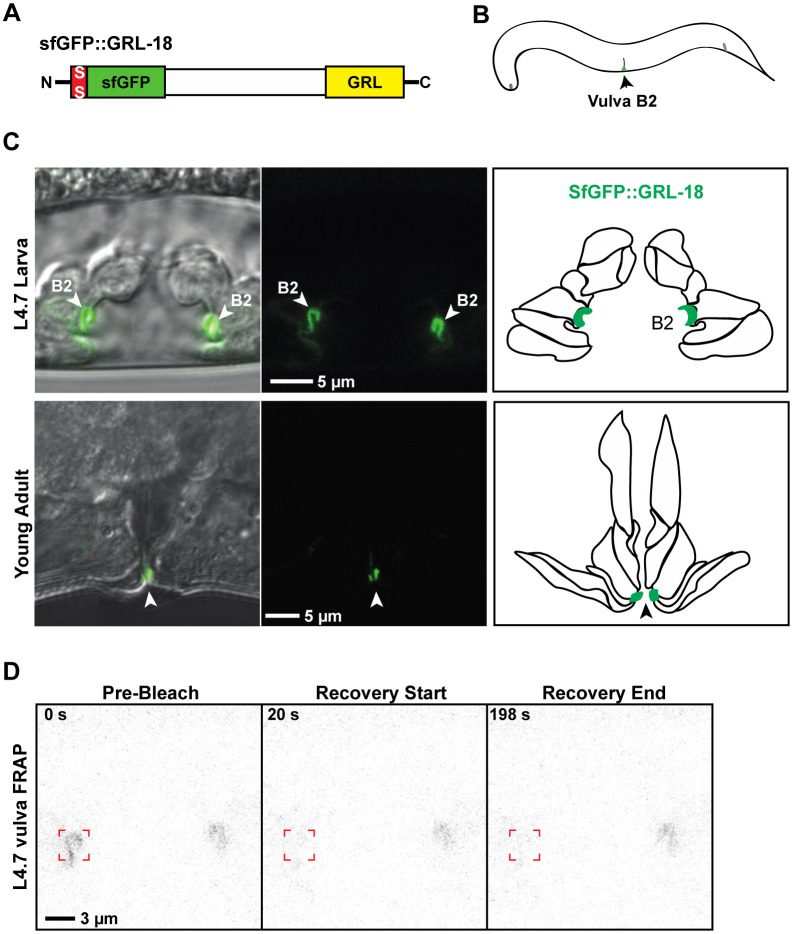

Figure 2. GRL-18 is a cell-specific cuticle component in the vulva.

A. SfGFP::GRL-18 schematic and B. Cartoon summary of expression pattern. C. In addition to labelling specific socket glial pores transiently in larvae as previously reported (Fung et al. 2023), SfGFP::GRL-18 labelled the cuticle of the vulB2 cell in the hermaphrodite vulva, beginning at the mid-L4 stage and continuing in the adult. Cartoons indicate the seven vulva cell types and the position of vulB2 cells at each stage, based on (Cohen et al. 2020). D. SfGFP:;GRL-18 showed no recovery after FRAP (n=15). See Table 1 for analysis.

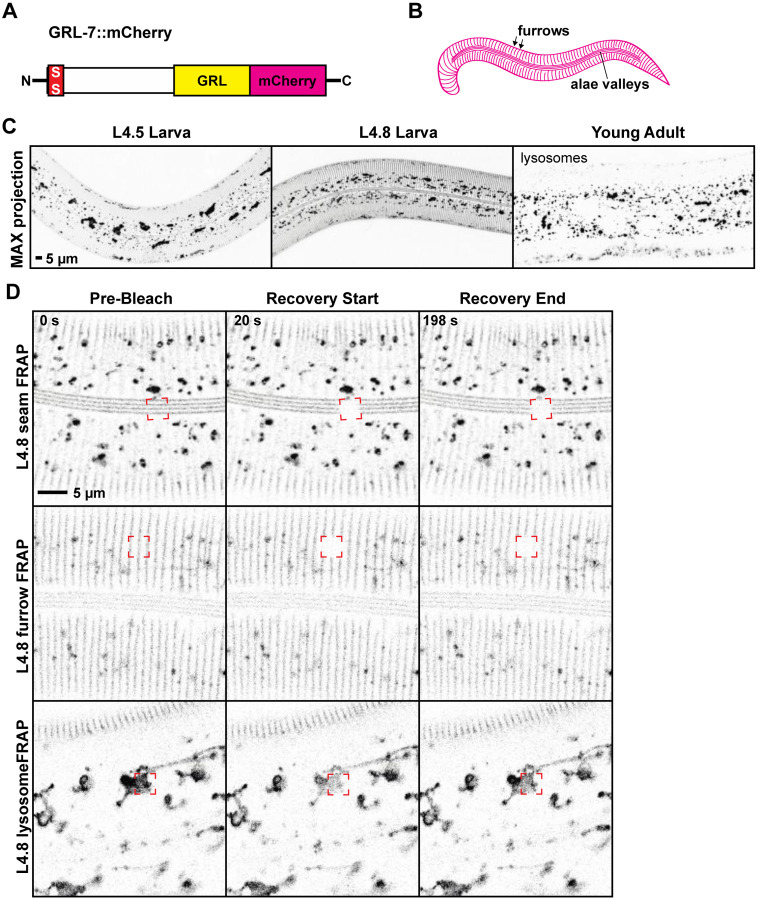

Figure 3. GRL-7 is a furrow-specific component of pre-cuticle.

A. GRL-7::mCherry schematic and B. Cartoon summary of expression pattern. C. GRL-7::mCherry transiently labelled developing furrow structures in the epidermal aECM and valley regions between developing alae ridges over the seam. GRL-7::mCherry labelled these aECM structures from the L4.5 to L4.9 stages and then was endocytosed and cleared before the molt. In adults, it was observed only in internal lysosome-like structures, where mCherry fusions often persist (Clancy et al. 2023; Birnbaum et al. 2023). This pattern of expression and endocytosis is similar to that reported for other pre-cuticle factors (Birnbaum et al. 2023) and for GRL-7 in embryos (Chiyoda et al. 2021). D. In both the seam and epidermal aECM, GRL-7::mCherry showed no recovery after FRAP (n=11 each). However, lysosomal signal recovered rapidly (n=6). See Table 1 for analysis.

Figure 4. WRT-10 is a broadly expressed component of pre-cuticle.

A. WRT-10::SfGFP schematic and B. Cartoon summaries of expression pattern. The epidermal and tube expression are coincident but are shown separately for clarity. C. WRT-10::SfGFP transiently labelled the excretory duct and pore, rectum (not shown), and vulva tubes in the intermolt periods, along with developing annuli structures in the epidermal aECM and developing alae ridges over the seam - a pattern complementary to that of GRL-7 (see Fig. 3). Like GRL-7, WRT-10::SfGFP was endocytosed and cleared before the molt. It was not detectable in adults. D. In the vulva, WRT-10::SfGFP showed limited recovery after FRAP. See Table 1 for analysis. E) wrt-10(aus36) adults have fragmented alae ridges (n=17/17), shown here with DIC (top) and after DiI staining, which specifically labels ridges and not valleys (Schultz and Gumienny 2012). Similar results were seen with wrt-10(aus37) (n=15/16).

To test if Hh-r proteins are stably associated or labile within the aECM, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). GRL-2, GRL-18, and GRL-7 all showed essentially no recovery in these experiments (Figures 1E, 2D, 3D, 4D and Table 1). In contrast, lysosomal GRL-7::mCherry recovered rapidly (Figure 3E and Table 1). WRT-10 showed limited recovery (Figure 4D), with a small mobile fraction similar to that previously reported for other pre-cuticle components such as the Zona Pellucida (ZP) protein LET-653 (Gill et al. 2016; Forman-Rubinsky et al. 2017). Together with the presence of SfGFP::GRL-2 in shed cuticles (Figure 1D), these data are consistent with Hh-r proteins being stably incorporated into aECMs.

Table 1.

FRAP analyses

| FRAP Experiment | n | Y0 | Plateau | Half-time | Mobile Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sfGFP::GRL-2 in Duct Lumen | 12 | 0.1492 | 0.1977 | 8.839 | 0.0485 |

| sfGFP::GRL-18 in Vulva Lumen | 15 | 0.5214 | 0.5436 | 56.89 | 0.0222 |

| GRL-7::mCherry Alae Valleys | 11 | 0.2057 | 0.274 | 15.95 | 0.0683 |

| GRL-7::mCherry Furrows | 11 | 0.2747 | 0.3418 | 40.58 | 0.0671 |

| GRL-7::mCherry Lysosomes | 6 | 0.1023 | 0.5242 | 14.3 | 0.4219 |

| WRT-10::sfGFP Vulva Lumen | 12 | 0.2754 | 0.542 | 30.64 | 0.2666 |

Values were calculated from fitted one-phase association curves (see Methods).

To assess the possibility that Hh-r proteins play structural roles in aECM organization, we examined grl-2, grl-18, grl-7 and wrt-10 deletion mutants for matrix-related defects. All mutants were viable (Table S2) and most appeared morphologically normal. However, two independent wrt-10 mutants had fragmented cuticle alae ridges (Figure 4E), a phenotype similar to that seen in multiple other pre-cuticle mutants (Forman-Rubinsky et al. 2017; Katz et al. 2022). We conclude that Hh-r proteins can play structural roles in aECM organization, although their mutant phenotypes are generally milder than those caused by loss of PTR proteins.

Structural roles of Hh-r proteins within cuticle and pre-cuticle aECM could explain many of their reported functions in tissue shaping, molting, and pathogen responses (Hao et al. 2006a; b; Lin and Wang 2017; Baker et al. 2021; Zárate-Potes et al. 2022). Cuticle damage could also release Hh-r components for signaling to activate stress and immune pathways (Dodd et al. 2018; Martineau et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2023). Furthermore, aECM tethering could help present Hh-r signals at a particular time and place. In this regard, the precise timing at which different pre-cuticle factors are expressed, assembled, and disassembled from matrix (Hendriks et al. 2014; Meeuse et al. 2020; Cohen and Sundaram 2020; Birnbaum et al. 2023) makes pre-cuticle Hh-r proteins ideally positioned to serve as signals of developmental progression to help coordinate the timing of other events during the molt cycle. The ability of grl-7 and grd-1 mutants to suppress the failed L1 diapause or developmental timing defects of other mutants (Kume et al. 2019; Chiyoda et al. 2021; Emans et al. 2023) might be explained by such a model. Finally, the presence of specific Hh-r proteins in the cuticle of tube orifices such as the vulva also raises the possibility of inter-animal signaling to mediate social interactions (Weng et al. 2023); however, we did not find any obvious mating deficiency in grl-18 mutant hermaphrodites (Table S3).

Canonical Hh proteins bind matrix proteoglycans and have intriguing similarities to matrix proteases (Roelink 2018; Gude et al. 2023; Zhang and Beachy 2023). In mycobacteria, Patched-related RND transporters transport glycolipids and other cargo to form the outer cell envelope, which is a type of aECM (Nikaido 2018; Dulberger et al. 2020). Therefore, it appears that interactions with the ECM are an ancient feature of the Hh-r and PTR protein families. Although C. elegans Hh-r proteins are highly divergent from Hh and other types of non-nematode Hh-r proteins (Bürglin 2008a), their expansion suggests broad and important roles in nematode biology. The realization that Hh-r proteins are embedded within cell-specific and temporally dynamic aECMs provides a foundation for better understanding those roles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Maxwell Heiman and Masamitsu Fukuyama for strains, Wendy Fung and Maxwell Heiman for stimulating discussions, Mara Cowen for assistance with FRAP, and Wormbase for facilitating data retrieval. Some strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is supported by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs P40 OD10440. This work was funded by NIH R35GM136315 to M.V.S.

References

- Baker E. A., Gilbert S. P. R., Shimeld S. M., and Woollard A., 2021. Extensive non-redundancy in a recently duplicated developmental gene family. BMC Ecol Evol 21: 33. 10.1186/s12862-020-01735-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum S. K., Cohen J. D., Belfi A., Murray J. I., Adams J. R. G., et al. , 2023. The proprotein convertase BLI-4 promotes collagen secretion prior to assembly of the Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle. PLoS Genet 19: e1010944. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürglin T. R., 1996. Warthog and groundhog, novel families related to hedgehog. Curr Biol 6: 1047–1050. 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70659-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürglin T. R., and Kuwabara P. E., 2006. Homologs of the Hh signalling network in C. elegans. WormBook 1–14. 10.1895/wormbook.1.76.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürglin T. R., 2008a. The Hedgehog protein family. Genome Biol 9: 241. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-11-241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürglin T. R., 2008b. Evolution of hedgehog and hedgehog-related genes, their origin from Hog proteins in ancestral eukaryotes and discovery of a novel Hint motif. BMC Genomics 9: 127. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C. elegans Deletion Mutant Consortium, 2012. large-scale screening for targeted knockouts in the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. G3 (Bethesda) 2: 1415–1425. 10.1534/g3.112.003830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiyoda H., Kume M., Del Castillo C. C., Kontani K., Spang A., et al. , 2021. Caenorhabditis elegans PTR/PTCHD PTR-18 promotes the clearance of extracellular hedgehog-related protein via endocytosis. PLoS Genet 17: e1009457. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy J. C., Vo A. A., Myles K. M., Levenson M. T., Ragle J. M., et al. , 2023. Experimental considerations for study of C. elegans lysosomal proteins. G3 (Bethesda) 13: jkad032. 10.1093/g3journal/jkad032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. D., Sparacio A. P., Belfi A. C., Forman-Rubinsky R., Hall D. H., et al. , 2020. A multi-layered and dynamic apical extracellular matrix shapes the vulva lumen in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife 9: e57874. 10.7554/eLife.57874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. D., and Sundaram M. V., 2020. C. elegans Apical Extracellular Matrices Shape Epithelia. J Dev Biol 8: E23. 10.3390/jdb8040023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. D., Cadena Del Castillo C. E., Serra N. D., Kaech A., Spang A., et al. , 2021. The Caenorhabditis elegans Patched domain protein PTR-4 is required for proper organization of the precuticular apical extracellular matrix. Genetics 219: iyab132. 10.1093/genetics/iyab132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd W., Tang L., Lone J.-C., Wimberly K., Wu C.-W., et al. , 2018. A Damage Sensor Associated with the Cuticle Coordinates Three Core Environmental Stress Responses in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 208: 1467–1482. 10.1534/genetics.118.300827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulberger C. L., Rubin E. J., and Boutte C. C., 2020. The mycobacterial cell envelope - a moving target. Nat Rev Microbiol 18: 47–59. 10.1038/s41579-019-0273-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emans S. W., Yerevanian A., Ahsan F. M., Rotti J. F., Zhou Y., et al. , 2023. GRD-1/PTR-11, the C. elegans hedgehog/patched-like morphogen-receptor pair, modulates developmental rate. Development 150: dev201974. 10.1242/dev.201974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman-Rubinsky R., Cohen J. D., and Sundaram M. V., 2017. Lipocalins Are Required for Apical Extracellular Matrix Organization and Remodeling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 207: 625–642. 10.1534/genetics.117.300207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung W., Wexler L., and Heiman M. G., 2020. Cell-type-specific promoters for C. elegans glia. J Neurogenet 34: 335–346. 10.1080/01677063.2020.1781851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung W., Tan T. M., Kolotuev I., and Heiman M. G., 2023. A sex-specific switch in a single glial cell patterns the apical extracellular matrix. Curr Biol 33: 4174–4186.e7. 10.1016/j.cub.2023.08.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill H. K., Cohen J. D., Ayala-Figueroa J., Forman-Rubinsky R., Poggioli C., et al. , 2016. Integrity of Narrow Epithelial Tubes in the C. elegans Excretory System Requires a Transient Luminal Matrix. PLoS Genet 12: e1006205. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gude F., Froese J., Steffes G., and Grobe K., 2023. The role of glycosaminoglycan modification in Hedgehog regulated tissue morphogenesis. Biochem Soc Trans 51: 983–993. 10.1042/BST20220719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao L., Aspöck G., and Bürglin T. R., 2006a. The hedgehog-related gene wrt-5 is essential for hypodermal development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology 290: 323–336. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao L., Mukherjee K., Liegeois S., Baillie D., Labouesse M., et al. , 2006b. The hedgehog-related gene qua-1 is required for molting in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Dyn 235: 1469–1481. 10.1002/dvdy.20721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao L., Johnsen R., Lauter G., Baillie D., and Bürglin T. R., 2006c. Comprehensive analysis of gene expression patterns of hedgehog-related genes. BMC Genomics 7: 280. 10.1186/1471-2164-7-280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks G.-J., Gaidatzis D., Aeschimann F., and Großhans H., 2014. Extensive oscillatory gene expression during C. elegans larval development. Mol Cell 53: 380–392. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. S., Barker T. J., Maul-Newby H. M., Sparacio A. P., Nguyen K. C. Q., et al. , 2022. A transient apical extracellular matrix relays cytoskeletal patterns to shape permanent acellular ridges on the surface of adult C. elegans. PLoS Genet 18: e1010348. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume M., Chiyoda H., Kontani K., Katada T., and Fukuyama M., 2019. Hedgehog-related genes regulate reactivation of quiescent neural progenitors in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 520: 532–537. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-C. J., and Wang M. C., 2017. Microbial Metabolites Regulate Host Lipid Metabolism through NR5A-Hedgehog Signaling. Nat Cell Biol 19: 550–557. 10.1038/ncb3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martineau C. N., Kirienko N. V., and Pujol N., 2021. Innate immunity in C. elegans. Curr Top Dev Biol 144: 309–351. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2020.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeuse M. W., Hauser Y. P., Morales Moya L. J., Hendriks G.-J., Eglinger J., et al. , 2020. Developmental function and state transitions of a gene expression oscillator in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Syst Biol 16: e9498. 10.15252/msb.20209498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok D. Z. L., Sternberg P. W., and Inoue T., 2015. Morphologically defined sub-stages of C. elegans vulval development in the fourth larval stage. BMC Dev Biol 15: 26. 10.1186/s12861-015-0076-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H., 2018. RND transporters in the living world. Res Microbiol 169: 363–371. 10.1016/j.resmic.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer J. S., Zhu Q., Huynh C., Sivaramakrishnan P., Preston E., et al. , 2019. A lineage-resolved molecular atlas of C. elegans embryogenesis at single-cell resolution. Science 365: eaax1971. 10.1126/science.aax1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A. P., and Johnstone I. L., 2007. The cuticle. WormBook 1–15. 10.1895/wormbook.1.138.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelink H., 2018. Sonic Hedgehog Is a Member of the Hh/DD-Peptidase Family That Spans the Eukaryotic and Bacterial Domains of Life. J Dev Biol 6: 12. 10.3390/jdb6020012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz R. D., and Gumienny T. L., 2012. Visualization of Caenorhabditis elegans cuticular structures using the lipophilic vital dye DiI. J Vis Exp e3362. 10.3791/3362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry T., Nicholas H. R., and Pocock R., 2019. New deletion alleles for Caenorhabditis elegans Hedgehog pathway-related genes wrt-6 and wrt-10. microPublication Biology. 10.17912/micropub.biology.000169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulavie F., Hall D. H., and Sundaram M. V., 2018. The AFF-1 exoplasmic fusogen is required for endocytic scission and seamless tube elongation. Nat Commun 9: 1741. 10.1038/s41467-018-04091-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeman N. M., Cota V., Keyes W., Kaletsky R., and Murphy C. T., 2020. CREB Non-autonomously Controls Reproductive Aging through Hedgehog/Patched Signaling. Dev Cell 54: 92–105.e5. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong-Brender T. T. K., Suman S. K., and Labouesse M., 2017. The apical ECM preserves embryonic integrity and distributes mechanical stress during morphogenesis. Development 144: 4336–4349. 10.1242/dev.150383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Fu R., Li G., Xiong S., Zhu Y., et al. , 2023. Hedgehog receptors exert immune-surveillance roles in the epidermis across species. Cell Rep 42: 112929. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng J.-W., Park H., Valotteau C., Chen R.-T., Essmann C. L., et al. , 2023. Body stiffness is a mechanical property that facilitates contact-mediated mate recognition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol 33: 3585–3596.e5. 10.1016/j.cub.2023.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zárate-Potes A., Ali I., Ribeiro Camacho M., Brownless H., and Benedetto A., 2022. Meta-Analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans Transcriptomics Implicates Hedgehog-Like Signaling in Host-Microbe Interactions. Front Microbiol 13: 853629. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.853629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., and Beachy P. A., 2023. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24: 668–687. 10.1038/s41580-023-00591-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zugasti O., Rajan J., and Kuwabara P. E., 2005. The function and expansion of the Patched- and Hedgehog-related homologs in C. elegans. Genome Res 15: 1402–1410. 10.1101/gr.3935405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.