When endocarditis develops in the presence of a ventriculo-atrial shunt, the condition is unlikely to resolve without removal of the foreign body. This can demand the skills of several disciplines.

CASE HISTORY

A woman aged 31 was admitted after two days of general malaise, fever and rigors. Born with spina bifida and hydrocephalus, she had been treated with a ventriculo-atrial shunt at the age of 17. Her medical history included recurrent urinary infections as a result of her percutaneous ileo-urostomy, the last such episode having been a week before, when a seven-day course of ciprofloxacin had been prescribed. The urine at that time had yielded no growth, but blood cultures had grown Staphylococcus aureus sensitive to erythromycin, ciprofloxacin and flucloxacillin.

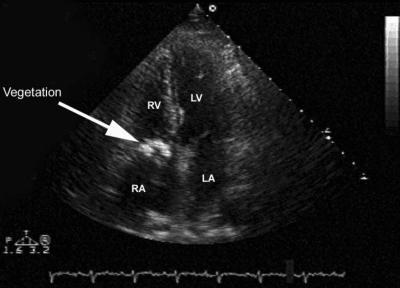

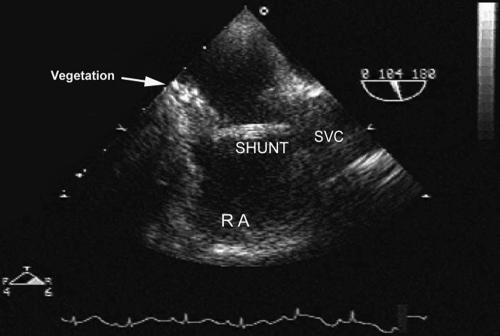

On examination she was pyrexial (39.6°C) and she had a purpuric rash over her arm, thighs and lower abdomen. No cardiac murmur was heard. White cell count was 24.9 × 109/L, platelets 587 × 109/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 87 mm/h, C-reactive protein 196 mg/L. There was blood in the urine but cultures were negative, and the biochemical profile was normal. Repeat blood culture grew S. aureus, which was again sensitive to erythromycin, ciprofloxacin and flucloxacillin. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a large echogenic structure in the tricuspid valve area (Figure 1), and transoesophageal echocardiography indicated that its superior location was to the tricuspid valve and its sessile base was on the right atrial endocardium (Figure 2). On CT of the brain, the upper part of the shunt was seen in the lateral cerebral ventricle; there was no evidence of intracranial sepsis or of intracranial hypertension. The patient was started on a long course of antibiotics—intravenous flucloxacillin and gentamicin for four weeks, to be followed by three weeks of oral flucloxacillin. Four days after starting this course the vegetation and the atrial part of her shunt were excised under cardiopulmonary bypass. Six days later the remaining part of the shunt was removed neurosurgically, with temporary external drainage of the cerebrospinal fluid. Microbiological cultures from both the shunt and the vegetation were negative, so a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt was then inserted. Her postoperative course was complicated by pulmonary embolism, but six months after discharge she seemed in good health.

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram; large, echo bright mass (arrow) in the right atrium

Figure 2.

Transoesophageal echocardiogram. Shunt in superior vena cava and right atrium; large vegetation (arrow) at the tip of shunt in right atrium

COMMENT

Bacteraemia and thrombus formation are known complications of ventriculo-atrial shunts,1 and central lines can lead to endocarditis even when the heart is normal.2 Where the condition is suspected, careful echocardiography is indicated.3,4

The present patient satisfied the Duke criteria for endocarditis5 but the echogenic mass in her right atrium was not typical of an oscillating vegetation. Echogenic ‘debris’ can build up from a longstanding ventriculo-atrial shunt. Nevertheless, we took the view that the right atrial mass might well harbour infection and she would require both cardiac surgery (necessary because blind pulling of the shunt might have dislodged the vegetation, causing pulmonary embolism) and neurosurgery—to remove the shunt and ensure cerebrospinal fluid sterility before it was replaced.

It is noteworthy that a cardiac murmur was never heard in this patient. Cardiac murmurs can be very soft or absent in the early stages of infective endocarditis, and also in sick patients with a low cardiac output or cardiogenic shock.

References

- 1.Buch J. Severe tricuspid incompetence due to endocarditis complicating a ventriculo-venous shunt. Neurochirurgia 1981;24: 180-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellamy CM, Roberts DH, Ramsdale DR. Ventriculo-atrial shunt causing tricuspid endocarditis. Int J Cardiol 1990;28: 260-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yavuzgil O, Ozerkan F, Erturk U, Islekel S, Atay U, Buket S. A rare cause of right atrial mass: thrombus formation and infection complicating a ventriculoatrial shunt for hydrocephalus. Surg Neurol 1999;52: 54-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheitlin MD, Alpert JS, Armstrong WF, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Clinical Applications of Echocardiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography. Circulation 1997;95: 1686-744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace SM, Walton BI, Kharbanda RK, Hardy R, Wilson AP, Swanton RH. Mortality from infective endocarditis: clinical predictors of outcome. Heart 2002;89: 53-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]