Abstract

Background & objectives:

In view of anecdotal reports of sudden unexplained deaths in India’s apparently healthy young adults, linking to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection or vaccination, we determined the factors associated with such deaths in individuals aged 18-45 years through a multicentric matched case–control study.

Methods:

This study was conducted through participation of 47 tertiary care hospitals across India. Cases were apparently healthy individuals aged 18-45 years without any known co-morbidity, who suddenly (<24 h of hospitalization or seen apparently healthy 24 h before death) died of unexplained causes during 1st October 2021-31st March 2023. Four controls were included per case matched for age, gender and neighborhood. We interviewed/perused records to collect data on COVID-19 vaccination/infection and post-COVID-19 conditions, family history of sudden death, smoking, recreational drug use, alcohol frequency and binge drinking and vigorous-intensity physical activity two days before death/interviews. We developed regression models considering COVID-19 vaccination ≤42 days before outcome, any vaccine received anytime and vaccine doses to compute an adjusted matched odds ratio (aOR) with 95 per cent confidence interval (CI).

Results:

Seven hundred twenty nine cases and 2916 controls were included in the analysis. Receipt of at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine lowered the odds [aOR (95% CI)] for unexplained sudden death [0.58 (0.37, 0.92)], whereas past COVID-19 hospitalization [3.8 (1.36, 10.61)], family history of sudden death [2.53 (1.52, 4.21)], binge drinking 48 h before death/interview [5.29 (2.57, 10.89)], use of recreational drug/substance [2.92 (1.1, 7.71)] and performing vigorous-intensity physical activity 48 h before death/interview [3.7 (1.36, 10.05)] were positively associated. Two doses lowered the odds of unexplained sudden death [0.51 (0.28, 0.91)], whereas single dose did not.

Interpretation & conclusions:

COVID-19 vaccination did not increase the risk of unexplained sudden death among young adults in India. Past COVID-19 hospitalization, family history of sudden death and certain lifestyle behaviors increased the likelihood of unexplained sudden death.

Keywords: Alcohol, case–control, coronavirus disease 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination, India, physical activity, smoking, sudden death, young adults

Globally, the incidence of sudden death among young adults had been estimated to be about 0.8-6.2 per 100,000/year1. Cardiovascular causes, including arrhythmia, myocardial ischaemia, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, aortic aneurysm and valvular diseases, are the most commonly reported causes of such deaths2,3. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in excess mortality and studies have documented the same in certain age groups4-6.

In India, there have been several anecdotal reports about sudden unexplained deaths among apparently healthy adults, purportedly linked to COVID-19 or COVID-19 vaccination7,8. The pathways through which COVID-19 may cause sudden deaths are currently not well-understood. However, it has been implicated that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection increases the risk of heart disease and stroke possibly through direct viral invasion of cardiomyocytes and subsequent cell death, endothelitis, transcription alteration, complement-mediated coagulopathy and downregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and dysregulation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system9. Although there is some evidence for the increased risk of death among COVID-19-recovered individuals and among those with breakthrough infections, the evidence for sudden deaths among such individuals is scarce10-13. COVID-19 vaccination by and large has been documented with preventing all-cause mortality across age groups and settings14,15.

Various consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been documented by many independent researchers. These include increased risk documented by Xie et al9 for ischaemic heart disease [hazard ratio (HR)=1.72; 1.56-1.90] and also for stroke (HR=1.52; 1.43-1.62) post 30 days of COVID-19. In a self-controlled case series, Katsoularis et al16 documented the increased rate for acute myocardial infarction in the first [Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR)=2.89; 1.51-5.55, second IRR=2.53; 1.29-4.94] and next two weeks (IRR=1.60; 0.84-3.04). Yeo et al8 estimated an excess risk (Risk Difference=5.3%; 1.6%-9.1%) for acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a nested case–control study conducted in India among individuals aged 18-45 yr and hospitalized for COVID-19; investigators had documented a protective role of COVID-19 vaccination for mortality subsequent to discharge from COVID-1917.

In the Indian context, the reports of sudden death among young adults have not been investigated in detail. In view of the uncertainty of evidence on the risk of sudden death among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a multicentric matched case–control study to determine the factors associated with unexplained sudden deaths among apparently healthy individuals aged 18-45 years in India.

Material & Methods

Study design and setting: A matched case–control study was conducted in 47 tertiary care hospitals across 19 States/Union Territories of India during May-August 2023 after obtaining approvals from the Institutional Ethics Committees of all the participating study centres.

Sample size: At the time of developing the protocol, the WHO guidance document18 provided a cutoff of 42 days since vaccination for linking to any adverse events of special interest. Considering India’s overall COVID-19 vaccination coverage data, we assumed 15 per cent average coverage for at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine in the past 42 days (proportion of controls exposed). Further, we considered an odds ratio (OR) of 1.3, correlation of 0.2, case: control ratio of 1:4, 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) and 80 per cent power. Based on these assumptions, we required 1145 cases and 4580 matched controls.

Definition of cases: Cases were those aged 18-45 yr, who experienced unexpected sudden death, including sudden cardiac death and were registered in the study hospitals between 1st October 2021 and 31st March 2023. Unexplained sudden death was defined as a natural, non-traumatic death of an apparently healthy individual (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision codes R96, R98 and R99)19. Case could have been a ‘witnessed’ death, wherein death occurred in a hospital within 24 h of hospitalization or an ‘unwitnessed’ death, wherein death occurred outside the hospital setting within 24 h of previously seen to be apparently healthy, including a person brought dead to the hospital. We excluded individuals with known medical condition(s) that can explain death, those taking long-term medications and those who died of injury, accident, poisoning, suicide, homicide or drug overdose. Further, for logistic reasons, we did not consider individuals residing in a locality requiring investigators to undertake more than a day’s travel (~100 km distance) from the study hospital.

Definition of controls: We defined controls as apparently healthy individuals aged 18-45 yr matched with the cases based on age (±5 yr), gender and locality (residing in the same neighbourhood as the matched case for at least six months before the case’s death). Individuals with any known morbid condition requiring long-term medications were excluded as controls.

Selection of cases: The study hospitals prepared a line list of witnessed or unwitnessed deaths that occurred between October 1, 2021, and March 31, 2023, from hospital records, including death registers, medical certificates of cause of death and autopsy reports maintained in the various hospital departments. Two trained site physicians reviewed the records of witnessed deaths and determined their eligibility for the study as cases. For unwitnessed deaths, the study investigators perused available records or confirmed over telephone or at the time of interview of the best respondent the investigators whether the deceased (case) was apparently healthy 24 h before death. Following this, the study investigators visited the case household and conducted a verbal autopsy using a modified version of the 2022 WHO Verbal Autopsy instrument20. Two trained physicians reviewed the findings of the verbal autopsy and other information collected during the house visit and decided their eligibility for the study. The physicians were trained in the cause of death ascertainment through verbal autopsy using the ‘Mortality in India Established through Verbal Autopsy’21.

Selection of controls: Once case selection and interviews were over, the investigators searched for potential controls (matching for age and gender) from the households neighboring the case residence. For a selected case, the investigators visited households on either side of the case residence [left, right (within same street/lane) and over/below in in multistorey apartment]. We recruited one control per household; the first four eligible and willing controls were included per case.

Definitions of exposure variables: Information on COVID-19 vaccination and dates of vaccination were collected from records available with the respondents or the centralized database (search based on name, telephone number and address) wherever possible, or based on recall if the vaccination records were not available. Days since COVID-19 vaccination were calculated by using the date of most recent vaccination and date of death of cases. We used the date of death of cases for calculating the same interval for controls.

We considered laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection based on either of the following: self-reporting, past records or information obtained from ICMR laboratory surveillance database. Hospitalization, specifically for COVID-19, was considered for those reported positive for COVID-19 and information was collected on the nature and ways of receiving oxygen or intensive care. Determination of post-COVID-19 conditions (PCC) was based on the WHO22 and CDC23 definitions; presence of any of the symptoms (tiredness/fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog, altered smell, altered taste, chest pain, headache, cough, memory issue, joint pain, pain/spasm, post-exertional malaise, sleep problems and tachycardia/palpitations) after COVID-19, not present before COVID-19, affected daily functioning and not attributed to any other diagnosis were the characteristics. We considered the presence of PCC at one month and three months after COVID-19 diagnosis.

Current tobacco smoking was ascertained by determining whether the person was engaged in tobacco smoking at the time of interview for controls and up to the point of death for cases. Further, we ascertained a history of smoking at any time in the past to classify past smoking among non-current smokers; smoking-related questions were based on the Global Adult Tobacco Survey24. We ascertained consumption of any of the alcoholic beverages (beer, wine, whisky, rum, gin, vodka or locally prepared alcohol) at the time of interview for controls or up to the point of death for cases. Among those reporting consumption of alcohol, we ascertained binge drinking behavior (6 or more alcoholic drinks on a single occasion25) in the past one year and 48 h before death (for cases) or interview (for controls). Data was collected also on the frequency of use of recreational drugs/substances (Marijuana/Pot/Weed/Cocaine/Crack/heroine/LSD, methamphetamine) in the past one year before death/interview.

We defined vigorous-intensity physical activity as any activity that caused large increases in breathing or heart rate for at least 10 min continuously26 and ascertained if the same was part of their routine work or undertaken in the past one year and 48 h before interview (controls) or death (cases). Family history of sudden death was recorded if there were any first-degree relatives reported to have suddenly died within 24 h of being apparently healthy.

Data collection: Trained investigators obtained appointments telephonically before making house visits for data collection. On the day of house visit, the study investigators obtained written informed consent from the respondent of the case and collected information about sociodemographic characteristics, past medical history and other exposure variables using a structured questionnaire created with Open Data Kit (https://getodk.org/). The investigators identified the best adult respondent for the case as one who was with the deceased individual before and until the time of death and was expected to have knowledge about the details required for the study. For both cases and controls, wherever needed (especially for medical history, COVID-19 infection or vaccination), efforts were made to collect data from medical records available with the hospital or records/reports available with the respondents or from centralized databases (CoWIN or ICMR COVID-19 Testing Database).

Statistical analysis: Sociodemographic and exposure characteristics of cases and controls were presented as proportions. Univariate conditional logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the unadjusted matched odd ratio (OR) for each exposure variable. We considered variables from the univariate analysis with P<0.25 of OR in the multivariable conditional logistic regression models for computing adjusted matched OR (aOR) and 95 per cent CI. We constructed three multivariable models taking into account site-level heterogeneity using variance-covariance matrix (cluster) option and the interaction between hospitalization and vaccination. In model 1, we included receipt of any dose of the COVID-19 vaccine 42 days before death of cases, whereas model 2 included receipt of any dose of vaccine at any time and model 3 included the number of doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. In order to examine the dose-response trend for doses of vaccine received, we used post-estimation Wald test and compared the aORs between single versus two dose groups. We estimated statistical power for each of the exposure variables based on OR, the total number of observations and number of matches per case–control set for each model. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA SE software version 17 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Human participant protection: The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee (IHEC) of ICMR-National Institute of Epidemiology, Chennai and by the IHECs of all the participating study hospitals.

Results

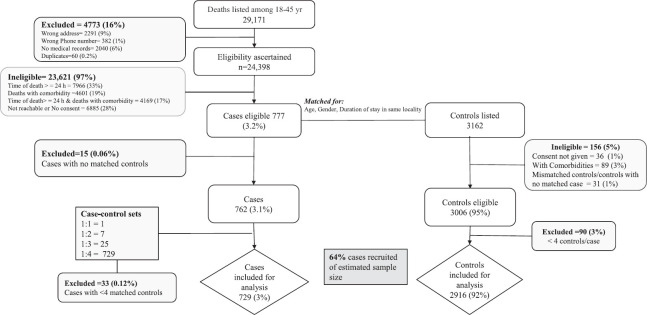

We listed 29,171 sudden deaths among individuals aged 18-45 yr as potential cases. Of these deaths, eligibility was ascertained for 24,398 (84%) and 777 (3.2%) met the eligibility criteria. We excluded 246 of the 3162 potential matched controls approached for various reasons. We also excluded 48 cases with less than four matched controls from the analysis (Figure).

Figure.

Flowchart of eligibility ascertainment of the cases and controls, multicentric matched case–control study of unexplained sudden deaths among young adults, India, 2023.

Characteristics of cases and controls: We included 729 cases and 2916 controls in the analysis. The majority of participants (87% cases and 81% controls) had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination any time before the outcome. A small proportion (2% of cases and 1% of controls) had been hospitalized for COVID-19 among which (2% of cases and 1% of controls) had a history of PCC at one month after COVID-19 diagnosis (none reported at three months). Nearly 10 per cent of the cases and 4 per cent of the controls had a family history of sudden death. About 27 per cent of cases and 19 per cent of controls were smokers. Alcohol use was reported among 27 per cent of cases and 13 per cent of controls. Among these, almost seven per cent of the cases and a little over 1 per cent of the controls reported binge drinking 48 h before death or interview. Vigorous intensity physical activity in the past one year was reported by 18 per cent of cases and 17 per cent of controls (Table I).

Table I.

Characteristics of cases and controls, multi-centric matched case–control study of unexplained sudden deaths among young adults, India, 2023

| Variables | Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Vaccination status | n=710 | n=2874 |

| Not vaccinated | 133 (18.7) | 359 (12.5) |

| One dose | 145 (20.4) | 355 (12.4) |

| Two doses | 401 (56.5) | 1944 (67.6) |

| Three doses | 31 (4.4) | 216 (7.5) |

| Any vaccination | 577 (81.3) | 2515 (87.5) |

| Days between vaccination and death of cases, median (IQR) | 257.8 (239.5) | 266.3 (251) |

| Interval between date of the most recent COVID-19 vaccination and date of death of cases* | n=421 | n=1522 |

| ≤42 days | 22 (5.2) | 90 (5.9) |

| >42 days | 266 (63.1) | 1073 (70.5) |

| Unvaccinated | 133 (31.6) | 359 (23.6) |

| Hospitalized for COVID-19 | n=706 16 (2.3) | n=2827 17 (0.6) |

| Post-COVID-19 condition (at one month) | n=688 14 (2) | n=2781 31 (1.1) |

| Family history of sudden death | n=719 69 (9.6) | n=2869 127 (4.4) |

| Smoking status | n=713 | n=2872 |

| Never smoker | 523 (73.4) | 2316 (80.6) |

| Current smoker | 163 (22.9) | 473 (16.5) |

| Past smoker | 27 (3.8) | 83 (2.9) |

| Alcohol use frequency | n=715 | n=2870 |

| Never user | 519 (72.6) | 2483 (86.5) |

| Moderate user | 82 (11.5) | 266 (9.3) |

| Heavy user | 114 (15.9) | 121 (4.2) |

| Binge drinking 48 h before death/interview | n=677 | n=2853 |

| 48 (7.1) | 46 (1.6) | |

| Recreational drug/substance use | n=717 | n=2870 |

| 12 (1.7) | 17 (0.6) | |

| Vigorous intensity physical activity | n=692 | n=2815 |

| Never performed | 561 (81.1) | 2334 (82.9) |

| Performed in the last year but not 48 h before death/interview | 107 (15.5) | 436 (15.5) |

| Performed 48 h before death/interview | 24 (3.5) | 45 (1.6) |

*Date of death of cases was used for calculating the interval for controls

Univariate analysis: In the univariate analysis, the odds of receipt of any dose of COVID-19 vaccine were lower for cases as compared to controls irrespective of when they received [received 42 days before death of cases (OR [95% CI]: 0.56 [0.32, 0.97]) received anytime (OR [95% CI]: 0.55 [0.34, 0.89])]. ORs differed by vaccine doses received for one dose [OR (95% CI): 1.05 (0.78, 1.44)] and for two doses [OR (95% CI): 0.46 (0.25, 0.58)] (Table II).

Table II.

Univariate analysis, multi-centric matched case–control study of unexplained sudden deaths among young adults, India, 2023

| Variables | Unadjusted matched OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Received COVID-19 vaccine ≤42 days before death of cases | 0.56 (0.32-0.97) | 0.041 |

| Received COVID-19 vaccine any time before death of cases | 0.55 (0.34-0.89) | 0.017 |

| Number of doses of COVID-19 vaccine | ||

| One dose | 1.05 (0.78-1.44) | 0.802 |

| Two doses | 0.46 (0.25-0.58) | 0.01 |

| Hospitalized for COVID-19 | 3.88 (1.94-7.79) | <0.001 |

| Post-COVID-19 condition | 1.79 (0.90-3.59) | 0.095 |

| Family history of sudden death | 2.7 (1.92-3.79) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current smoker | 1.94 (1.51-2.51) | <0.001 |

| Past smoker | 1.63 (1.03-2.59) | 0.038 |

| Alcohol use frequency | ||

| Moderate user | 2.72 (1.92-3.85) | <0.001 |

| Heavy user | 10.79 (7.27-16) | <0.001 |

| Binge drinking 48 h before death/interview | 6.38 (3.91-10.45) | <0.001 |

| Recreational drug/substance use | 3.78 (1.58-9.06) | 0.003 |

| Vigorous intensity physical activity | ||

| Performed in the last year | 1.09 (0.77-1.53) | 0.615 |

| Performed 48 h before death/interview | 2.75 (1.55-4.88) | <0.001 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Patients with unexplained sudden death were four times more likely to have had been hospitalized for COVID-19 [OR (95% CI): 3.88 (1.94, 7.79)], whereas PCC was not associated. Family history of sudden death was almost three times more likely to be associated with unexplained sudden death [OR (95% CI): 2.7 (1.92, 3.79)]. Lifestyle factors such as current smoking status, alcohol use frequency, recent binge drinking, recreational drug/substance use and vigorous-intensity activity were positively associated with unexplained sudden death. As compared to never users, the more the frequency of alcohol use, the higher was the odds for unexplained sudden death (Table II).

Multivariable analysis: Due to intrinsic dependencies within our data, we omitted PCC and alcohol frequency in the multivariable analysis. After including the interaction between hospitalization and vaccination, the first model did not achieve convergence. Hence, the interaction term was considered in the models 2 and 3.

In model 1, receipt of any dose of the COVID-19 vaccine within 42 days of the outcome was not significantly associated [aOR (95% CI): 0.53 (0.25, 1.14)] with unexplained sudden death. Hospitalization for COVID-19, binge drinking 48 h before death/interview and vigorous-intensity physical activity performed 48 h before death were significantly associated with increased odds for unexplained sudden death. The OR for current smokers [aOR (95% CI): 1.56 (1, 2.4)] was consistent with an increased likelihood of unexplained sudden death (Table III).

Table III.

Multivariable conditional logistic regression analysis, multi-centric matched case–control study of unexplained sudden deaths among young adults, India, 2023

| Variables | Model 1* (any dose of vaccine ≤42 days) | Model 2† (any vaccine, any time) | Model 3‡ (number of doses of vaccine, anytime) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Adjusted matched OR (95% CI) | Power (%) | Adjusted matched OR (95% CI) | Power (%) | Adjusted matched OR (95% CI) | Power (%) | |

| Received COVID-19 vaccine ≤42 days before death of cases | 0.53 (0.25-1.14) | 98 | - | - | - | - |

| Received COVID-19 vaccine any time before death of cases | - | 0.58 (0.37-0.92) | 100 | - | - | |

| Number of doses of COVID-19 vaccine | ||||||

| One dose | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.73-1.36) | 5 |

| Two doses | - | - | - | - | 0.51 (0.28-0.91)§ | 100 |

| Hospitalized for COVID-19 | 14.22 (4.01-50.38) | 100 | 3.8 (1.36-10.61) | 100 | 2.24 (0.48-10.32) | 95 |

| Family history of sudden death | 2.15 (0.98-4.75) | 99 | 2.53 (1.52-4.21) | 100 | 2.11 (1.26-3.51) | 100 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Current smoker | 1.56 (1-2.4) | 99 | 1.37 (0.95-1.99) | 100 | 1.38 (0.94-2.03) | 99 |

| Past smoker | 1.71 (0.63-4.67) | 100 | 1.69 (0.69-4.14) | 100 | 1.78 (0.69-4.62) | 99 |

| Binge drinking 48 h before death/interview | 5.96 (2.44-14.6) | 100 | 5.29 (2.57-10.89) | 100 | 5.56 (2.46-12.58) | 100 |

| Recreational drug/substance use | 0.96 (0.21-4.35) | 5 | 2.92 (1.12-7.71) | 100 | 2.91 (1.03-8.19) | 99 |

| Vigorous intensity physical activity | ||||||

| Performed in the last year | 0.97 (0.47-1.99) | 6 | 1.15 (0.61-2.17) | 65 | 1.09 (0.54-2.19) | 49 |

| Performed 48 h before death/interview | 4.64 (1.25-17.21) | 100 | 3.7 (1.36-10.05) | 100 | 3.82 (1.26-11.54) | 100 |

Number of observations included in each model: *Model 1=1259; †Model 2=2952; ‡Model 3=2670; §P=0.01 for post-estimation Wald test. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019

After adjusting for all other variables in model 2, receipt of any dose of COVID-19 vaccine was associated with lower odds [aOR (95% CI): 0.58 (0.37, 0.92)] of unexplained sudden death (Table III). Hospitalization for COVID-19 [aOR (95% CI): 3.8 (1.36, 10.61), family history of sudden death [aOR (95% CI): 2.54 (1.52, 4.21)], binge drinking 48 h before death [aOR (95% CI): 5.29 (2.56, 10.89)], recreational drug/substance use [aOR (95% CI): 2.91 (1.12, 7.71)] and vigorous-intensity physical activity 48 h before death [aOR (95% CI): 3.7 (1.36, 10.05)] were significantly associated with increased odds for unexplained sudden death. The OR for current smokers [aOR (95% CI): 1.37 (0.95, 1.99)] was consistent with an increased likelihood of unexplained sudden death (Table III).

In model 3, compared to no vaccination and adjusted for all other variables in the model, single dose of the COVID-19 vaccine did not show a statistically significant protective effect. However, receipt of two doses of vaccine was associated with lower odds for unexplained sudden death [aOR (95% CI): 0.51 (0.28, 0.91)]. The post-estimation test confirmed a significant dose–response trend (P=0.01), substantiating the higher level of protection offered by two doses. Family history of sudden death [aOR (95% CI): 2.11 (1.26, 3.51)], behaviours such as binge drinking 48 h before death and vigorous-intensity physical activity performed 48 h before death significantly increased the odds for unexplained sudden death among young adults. The OR for current smokers [aOR (95% CI): 1.38 (0.94, 2.03)] was consistent with an increased likelihood of unexplained sudden death (Table III).

Discussion

In view of media reports of unexplained sudden deaths among young adults allegedly linked to COVID-19 vaccination, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) commissioned a case–control study involving hospitals across India. Our findings did not indicate any evidence of positive association of unexplained sudden death with COVID-19 vaccination. However, a history of sudden death in the family, COVID-19 hospitalization and certain high-risk behavioral factors were positively associated with unexplained sudden death among young Indians.

We found no evidence of a positive association of COVID-19 vaccination with unexplained sudden death among young adults. On the contrary, the present study documents that COVID-19 vaccination indeed reduced the risk of unexplained sudden death in this age group. In terms of assessing27 the given association between vaccine and unexplained sudden death, we ruled out the role of chance through a statistically significant matched OR and adjusted for known confounders. Further, we documented a gradient of the association with the vaccine doses. The primary purpose of vaccination is to prevent COVID-19-associated severity28. Studies have documented adverse events, predominantly thromboembolic events, following COVID-19 vaccination29,30. However, evidence, although scant, exists for its protection offered against all-cause mortality across age groups14,15. Thus, our findings of reduced risk of unexplained sudden death among young adults are consistent with the findings on prevention of all-cause mortality and it is reasonable that an analogy could be made to that of a reduced risk of death among a subset of the population. As noted earlier, an Indian study documented such preventive role of COVID-19 vaccination for post-discharge mortality among young adults post-COVID-1917.

The biological plausibility of this reduced risk of unexplained sudden death among vaccine recipients requires deeper examination. Globally, studies have documented an increased risk of cardiovascular complications following COVID-1931,32. In the present study, we documented that reported hospitalization for COVID-19 independently increased the risk of unexplained sudden death by fourfold. Further, studies have documented that COVID-19 vaccination reduces the risk of severe COVID-19 as measured through hospitalization following COVID-1928,33. As per the published report, an increased risk for cardiovascular complications following COVID-19 infection leading to sudden cardiac death is a suggested plausibility through multifactorial mechanisms34. The reduced risk following COVID-19 vaccination, as observed in our study, could possibly be due to the protection offered by COVID-19 vaccination against severe COVID-19, leading to reduced chances of cardiovascular events and thereby reducing the risk of death among them. However, longitudinal studies are required to understand such causal pathways.

The effect size for hospitalization in model 1 (wherein interaction between hospitalization and vaccination could not be included) was contrastingly higher (almost four times) as compared to the effect size estimated from model 2 and was not significant in model 3. This difference could be explained on the basis of number of exposed included in these models. In this study, a total of 33 individuals reported a history of hospitalization for COVID-19. In model 1, wherein we considered duration since vaccination before the outcome, of the 33 hospitalized, vaccination dates were available for 21, of whom, only one had received vaccination ≤42 days and thus was considered as exposed. However, in model 2 considering vaccination anytime, of the 33 with hospitalization history, 28 were considered exposed. These numbers could have influenced the differences in the effect size and the precision thereof. However, the direction of the effect was similar in the first two models.

In addition to the COVID-19-specific factors, we identified two lifestyle related high-risk behaviours associated with unexplained sudden death. Binge drinking 48 h before death/interview was identified to be associated. Several studies have documented that heavy and binge drinkers are at increased risk of stroke, cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death35. It has been shown that large amount of alcohol can lead to QT prolongation and cardiac arrhythmias, in turn leading to sudden death35,36. Unaccustomed physical activity of vigorous and intense nature 48 h before death was associated with unexplained sudden death. Exertion during physical exercise is known to increase the chances of acute plaque rupture making partial or complete blockage of coronary arteries and thus leading to sudden death37,38.

Strengths of the study: Our study has certain strengths. During the design of the study, we considered various issues to overcome biases and limitations. This included matched design to increase the statistical efficiency and operational ease of recruiting controls in the field as well. In the absence of prior data to calculate meaningful sample size, we did assume days since COVID-19 vaccination based on prevailing data and the plausible time interval for documenting the adverse events of special interest post-vaccination suggested by the WHO18. Our sample size, although lesser than computed, we had almost 100 per cent power for key variables under consideration. The challenges of recruiting cases with reasonable accuracy and meeting the sample size were overcome through the inclusion of witnessed and unwitnessed deaths, confirmation of case status through rigorous scrutiny by multiple physicians and training of investigators through the adaptation of the WHO’s VA instrument20. This study drew strength by including sites across the country from a variety of settings and the site heterogeneity was accounted in the statistical model as well.

Study limitations: Our study has a few limitations. First, there is a potential for misclassification of cases or controls. We might not have been able to fully satisfy the inclusion criteria in terms of ‘explainability’ of the cause of death, possibly due to the inability of the health facility to ascertain any undiagnosed/unreported conditions or lack of documentation in the records on self-reported medications. However, this is unlikely to have played a major role in this study due to the specific methods used. Three-fourth of the cases in our study belonged to the witnessed death category, and hence, likely to have had better documentation of diagnosis or medical history and thereby allowing subsequent review by study site clinicians. In the remaining cases of unwitnessed deaths, we relied on verbal autopsy in the field by trained investigators followed by the assignment of medical cause after review by two study site clinicians. Although minimal, such misclassification of outcome would thus be differential and could have biased our effect estimate in either direction. We could have had bias in the selection of controls, if potential controls were not available for the interview, specifically, on account of being in a state of inebriation. This could have led to an overestimation of the association for binge drinking.

In terms of exposure ascertainment, our study could suffer from information bias during data collection. We could have had differential misclassification of exposure variables of vaccination status and lifestyle risk factors such as accurate recording of alcohol or substance use. While for cases, we relied on information provided by the best proxy respondents, the information from controls was obtained directly. This could have biased our effect estimates in either direction.

The information on the dates of vaccination was not available from all the study participants. To maximize the availability of dates of vaccination, in addition to self-reported dates, we did obtain the dates of vaccination from centralized databases. Further, we noted that the availability of dates of vaccination was almost equal for the cases and controls and the power for this analysis was 98 per cent.

Overall, based on the findings from this multi-centric case–control study, it was concluded that COVID-19 vaccination was not associated with an increased risk of unexplained sudden death among young adults. At the same time, family history of sudden death, hospitalization for COVID-19 and lifestyle behaviours such as recent binge drinking and vigorous-intensity physical activity were risk factors for unexplained sudden death. Addressing these factors among young adults could potentially modify their risk of unexplained sudden death.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study received funding support from Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India (VIR/8/2023/ECD-1).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgment:

The authors acknowledge the contributions of all study participants and field investigators from all the collaborating institutions. Ms Jeen Melfha M and Shri Sabarinathan R are acknowledged for developing the data collection tool in Open Data Kit.

References

- 1.Eckart RE, Shry EA, Burke AP, McNear JA, Appel DA, Castillo-Rojas LM, et al. Sudden death in young adults: An autopsy-based series of a population undergoing active surveillance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1254–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daş T, Buğra A. Natural causes of sudden young adult deaths in forensic autopsies. Cureus. 2022;14:e21856. doi: 10.7759/cureus.21856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saadi S, Ben Jomaa S, Bel Hadj M, Oualha D, Haj Salem N. Sudden death in the young adult: A Tunisian autopsy-based series. BMC Public Health. 2020;1915;20 doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10012-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu D, Dhanoa S, Cheema H, Lewis K, Geeraert P, Merrick B, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) excess mortality outcomes associated with pandemic effects study (COPES): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:999225. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.999225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azarudeen MJ, Aroskar K, Kurup KK, Dikid T, Chauhan H, Jain SK, et al. Comparing COVID-19 mortality across selected states in India: The role of age structure. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;12:100877. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.COVID-19 Excess Mortality Collaborators. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020-21. Lancet. 2022;399:1513–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02796-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sessa F, Salerno M, Esposito M, Di Nunno N, Zamboni P, Pomara C. Autopsy findings and causality relationship between death and COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review. J Clin Med. 2021;5876;10 doi: 10.3390/jcm10245876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeo YH, Wang M, He X, Lv F, Zhang Y, Zu J, et al. Excess risk for acute myocardial infarction mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Virol. 2023;95:e28187. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583–90. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, McDonald D, Magedson A, Wolf CR, et al. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e210830. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proal AD, VanElzakker MB. Long COVID or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): An overview of biological factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:698169. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.698169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naik S, Haldar SN, Soneja M, Mundadan NG, Garg P, Mittal A, et al. Post COVID-19 sequelae: A prospective observational study from Northern India. Drug Discov Ther. 2021;15:254–60. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2021.01093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259–64. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchand G, Masoud AT, Medi S. Risk of all-cause and cardiac-related mortality after vaccination against COVID-19: A meta-analysis of self-controlled case series studies. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19:2230828. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2023.2230828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu B, Stepien S, Dobbins T, Gidding H, Henry D, Korda R, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination against COVID-19 specific and all-cause mortality in older Australians: A population based study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;40:100928. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsoularis I, Fonseca-Rodríguez O, Farrington P, Lindmark K, Fors Connolly AM. Risk of acute myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke following COVID-19 in Sweden: A self-controlled case series and matched cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:599–607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00896-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar G, Talukdar A, Turuk A, Bhalla A, Mukherjee S, Bhardwaj P, et al. Determinants of post discharge mortality among hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Indian J Med Res. 2023;158:136–44. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.ijmr_973_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Protocol template to be used as template for observational study protocols for cohort event monitoring (CEM) for safety signal detection after vaccination with COVID-19 vaccines. Geneva: WHO; 2021. p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10)-WHO Version for; 2019-covid-expanded. ICD-10 version: 2019. [accessed on October 14, 2023]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/R95-R99 .

- 20.World Health Organization. 2022 WHO verbal autopsy instrument. Geneva: WHO; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MINErVA network India 2023. [accessed on October 12, 2023]. Available from: https://causeofdeathindia.com/

- 22.Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV. WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e102–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Post-COVID conditions; 2023. [accessed on October 12, 2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html .

- 24.Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group. Global adult tobacco survey (GATS): question by question specifications. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- 25.CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Excessive alcohol use; 2022. [accessed on October 12, 2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/alcohol.htm .

- 26.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Geneva: WHO; 2020. p. 104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill AB. The environment and disease:association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang ZR, Jiang YW, Li FX, Liu D, Lin TF, Zhao ZY, et al. Efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the dose-response relationship with three major antibodies: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4:e236–46. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasmin F, Najeeb H, Naeem U, Moeed A, Atif AR, Asghar MS, et al. Adverse events following COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: A systematic review of cardiovascular complication, thrombosis, and thrombocytopenia. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023;11:e807. doi: 10.1002/iid3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Burn E, Duarte-Salles T, Yin C, Reich C, Delmestri A, et al. Comparative risk of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome or thromboembolic events associated with different Covid-19 vaccines: International network cohort study from five European countries and the US. BMJ. 2022;379:e071594. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loo J, Spittle DA, Newnham M. COVID-19, immunothrombosis and venous thromboembolism: Biological mechanisms. Thorax. 2021;76:412–20. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malas MB, Naazie IN, Elsayed N, Mathlouthi A, Marmor R, Clary B. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29:100639. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhatnagar T, Chaudhuri S, Ponnaiah M, Yadav PD, Sabarinathan R, Sahay RR, et al. Effectiveness of BBV152/Covaxin and AZD1222/Covishield vaccines against severe COVID-19 and B.1.617.2/Delta variant in India, 2021: A multi-centric hospital-based case-control study. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:693–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yadav R, Bansal R, Budakoty S, Barwad P. COVID-19 and sudden cardiac death: A new potential risk. Indian Heart J. 2020;72:333–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmström L, Kauppila J, Vähätalo J, Pakanen L, Perkiömäki J, Huikuri H, et al. Sudden cardiac death after alcohol intake: Classification and autopsy findings. Sci Rep. 2022;12:16771. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20250-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Day CP, James OF, Butler TJ, Campbell RW. QT prolongation and sudden cardiac death in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Lancet. 1993;341:1423–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90879-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Rosendael AR, de Graaf MA, Scholte AJ. Cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise: Coronary plaque rupture or myocardial ischaemia? Neth Heart J. 2015;23:130–2. doi: 10.1007/s12471-014-0647-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson PD, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, Blair SN, Corrado D, Estes NA, 3rd, et al. Exercise and acute cardiovascular events placing the risks into perspective: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism and the council on clinical cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2358–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]