Ganglioneuromas are benign tumours of the sympathetic nervous system. The occasional report of a paratesticular ganglioneuroma reflects embryological development.

CASE HISTORY

A man of 22 with insulin-dependent diabetes was referred for treatment of a phimosis secondary to balanitis xerotica obliterans. On routine examination he was found to have a smooth mobile mass in the right hemiscrotum. Scrotal ultrasound revealed several solid paratesticular lesions and a scrotal exploration was undertaken. Five small masses were identified and removed. All were paratesticular; the testicle, epididymis and vas deferens were entirely normal.

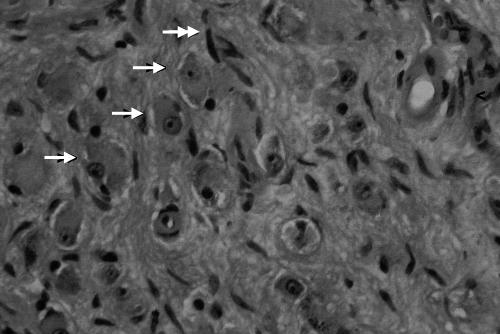

On histological examination the lesions proved to be composed of spindle cells resembling those of a nerve sheath tumour, as well as large round cells with abundant amphophilic cytoplasm and a large slightly eccentrically placed nucleus with a prominent nucleolus (Figure 1). There were no immature elements. They were judged to represent benign ganglioneuromata. MRI scanning excluded the presence of any synchronous retroperitoneal tumour.

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of ganglion cell-rich area. Arrows point to ganglion cells (→) and spindle cells (↠)

COMMENT

Ganglioneuromas are the most benign of the neuroblastic group of tumours, which include neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma.1 They consist of ganglion cells, Schwann cells and connective tissue.1,2 The most common locations are the posterior mediastinum, retroperitoneum, adrenal gland and neck.1 To our knowledge there have only been three previously reported cases of paratesticular ganglioneuromas,3–5 of which one was actually a composite tumour consisting of a ganglioneuroma and a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour.3 Two of these cases were in children, one5 in an adult.

The paratesticular region consists of many cell types and neoplasms arising therefrom are histologically heterogeneous.6 Tumours in this region present as discrete scrotal masses and may cause diagnostic confusion with testicular tumours. The commonest benign tumours are lipomata, adenomatoid tumours and leiomyomata; the more common malignant neoplasms are sarcomas, mesotheliomas, lymphomas and epididymal adenocarcinomas.6 This region may on rare occasions be the site of metastatic spread of other primary tumours, including lung, pleura, stomach, colon, prostate and kidney.6 Scrotal involvement by a tumour that commonly affects the retroperitoneum is not surprising in view of their common embryological origin. For this reason a patient with paratesticular ganglioneuromas should undergo imaging of the retroperitoneum and posterior mediastinum.

References

- 1.Lonergan GJ, Schwab CM, Suarez ES, Carlson CL. Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic–pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2002;22: 911–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain M, Subha BS, Sethi S, Banga V, Bagga D. Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma: report of a case diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology, with review of the literature. Diagnostic Cytopathol 1999;21: 194–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks E, Moonahm Y, Brodhecker C, Goheen M. A malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in association with a paratesticular ganglioneuroma. Cancer 1989;64: 1738–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceroni V, Di Lüttichau F. Su una rar osservazione di ganglioneuroma paratesticolare nell’infanzia. Pathologica 1975;67: 245–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardalidis NP, Grigoriadis K, Papatsoris A, Kosmaoglou EV, Horti M. Primary paratesticular adult ganglioneuroma. Urology 2004;63: 584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoubehi B, Mishra V, Ali M, Motiwala H, Karim O. Adult paratesticular tumours. BJU Int 2002;90: 707–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]