Abstract

We have constructed and analyzed a group of Shigella flexneri 5 auxotrophic mutants. The wild-type strain M90T was mutagenized in genes encoding enzymes involved in the synthesis of (i) aromatic amino acids, (ii) nucleotides, and (iii) diaminopimelic acid. In this way, strains with single (aroB, aroC, aroD, purE, thyA, and dapB) and double (purE aroB, purE aroC, purE aroD, purE thyA) mutations were obtained. Although the Aro mutants had the same nutritional requirements when grown in laboratory media, they showed different degrees of virulence in vitro and in vivo. The aroB mutant was not significantly attenuated, whereas both the aroC and aroD strains were severely attenuated. p-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) appeared to be the main requirement for the Aro mutants’ growth in tissue culture. Concerning nucleotides, thymine reduced the pathogenicity, whereas adenine did not. However, when combined with another virulence-affecting mutation, adenine auxotrophy appeared to potentiate that mutation’s effects. Consequently, the association of either the purE and aroC or the purE and aroD mutations had a great effect on virulence as measured by the Sereny test, whereas the purE aroB double mutation appeared to have only a small effect. All mutants except the dapB strain seemed to move within a Caco-2 cell monolayer after 3 h of infection. Nevertheless, the auxotrophs showing a high intracellular generation time were negative in the plaque assay. Knowledge of each mutation’s role in attenuating Shigella strains will provide useful tools in designing vaccine candidates.

Shigella flexneri is a human pathogen that provokes bacillary dysentery by invading the colonic mucosa (20). The pathogenic process encompasses several steps: (i) bacterial entry into colonic epithelial cells; (ii) intracellular multiplication; and (iii) intraintercellular spreading, which allows bacteria to infect neighboring cells (for reviews see references 9, 15, and 39).

Localized lesions at the colonic mucosa level result from cell destruction and inflammation (27). All of these events ultimately induce the symptoms of dysentery, which include fever and stools containing mucus and blood (15). The molecular and cellular basis of pathogenesis has been studied by using limited laboratory animal models and in vitro-grown mammalian cell lines which are susceptible to infection (16).

Entry into epithelial cells occurs by an engulfment of the host cell membrane at the interaction points with bacteria (1). The membrane rearrangements are associated with the formation of actin polymerization foci which are close to the sites of bacterium-cell contact. Components of both bacteria and host cells actively participate in this process. On the host cell side, several proteins such as plastin (1), the small GTPase Rho (2), and the proto-oncoprotein pp60 (10) have been found to be involved in this step. On the bacterial side, determinants necessary for mediating S. flexneri uptake are localized on a 31-kb fragment of a large plasmid (28, 44). Invasion plasmid antigens IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD are the real effectors of the entry phenotype (30).

After being internalized, S. flexneri lyses the phagosomal vacuole and multiplies within the cytoplasm of infected cells (43). Intracellular shigellae express and secrete the plasmid-encoded IcsA, which allows the spreading of bacteria within the cytoplasm and dissemination into adjacent cells (7, 25). IcsA, located at one pole of the bacterium, governs S. flexneri movement by interacting with F-actin and vinculin (12, 13, 49).

While several studies address the processes of bacterial penetration and movement, scant information is available regarding the intracellular multiplication process and particularly which metabolites required for replication are present, in limited amounts, in the cytoplasm of infected cells. Nevertheless, in recent years, studies on vaccine candidate construction have indicated that mutations in biosynthetic pathways of both aromatic amino acids and nucleotides may alter the intracellular replication of shigellae (4, 21, 22, 35, 36). Lindberg and coworkers showed that S. flexneri 2a microorganisms harboring an aroD mutation are attenuated not only in vitro but also in vivo (21, 22). Moreover, Noriega and coworkers also demonstrated that S. flexneri aroA mutants are affected in virulence (35). These two Aro mutants showed a reduced intracellular growth as demonstrated in the cell culture invasion assay. Aro mutants are auxotrophic for aromatic amino acids and other molecules such as p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) and dehydrobenzoic acid. Virulence phenotypes of these two mutants appear to be similar, but since they have not been directly compared, it is still unclear if mutations in aroA and aroD induce equivalent attenuation.

On the other hand, S. flexneri 2 Pur− mutants (not characterized at the genetic level) have been found not to be attenuated either in vitro in HeLa cells (23) or in vivo in a guinea pig model. This model measures the ability of virulent shigellae to induce keratoconjunctivitis when they are inoculated in the conjunctival sac (Sereny test) (47). By contrast, a recent study by Noriega et al. has shown that the guaB-A deletion mutant, unable to synthesize guanine nucleotides, is severely impaired in intracellular multiplication (36). Concerning pyrimidines, S. flexneri Y thymine auxotrophs (thyA) do not produce a cytopathic effect on a confluent HeLa cell monolayer and have low levels of virulence in vivo (4, 38). These auxotrophic mutants have been used as vaccine candidates. In particular, to obtain a strong virulence attenuation, either the ΔaroA, the ΔguaB-A, or the ΔthyA mutation (affecting the intracellular proliferation) has been combined with an icsA deletion (altering intracellular-intercellular spreading) (35, 36, 53).

These observations suggest that some products of the Aro pathway are present in host cell cytoplasm and tissues in a limited amount and that their availability may affect intracellular bacterial growth. Concerning purines, the findings presented by different groups at times appear to be contradictory.

The purpose of our study was to further investigate intracellular multiplication through the analysis of a group of auxotrophic mutants of the S. flexneri 5 wild-type strain M90T, with the aim of identifying those metabolites necessary to cell invasion whose absence could influence the intracellular behavior of shigellae and ultimately their degree of virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The bacterial strains used are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Bacteria were routinely cultured in tryptic soy broth (BBL, Becton Dickinson and Company, Cockeysville, Md.) or brain heart infusion (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). The ability of bacteria to bind the pigment Congo red was assessed by using tryptic soy broth plates containing 1.5% agar and 0.01% Congo red. M9 salts (32) were used for preparing minimal medium. Carbon sources were added to a final concentration of 0.2% with the addition of nicotinic acid (10 μg/ml) to support the growth of shigellae. M9 was supplemented with various nutrients required by the different auxotrophic mutants. Briefly, aroC, aroB, and aroD mutants grew on M9 medium with PABA and 3,4-dehydroxybenzoate (both to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml) plus tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine (all at 40 μg/ml). thyA, purE, and dapB mutants required thymine (50 μg/ml), adenine (50 μg/ml), and diaminopimelic acid (100 μg/ml), respectively. Kanamycin, spectinomycin, tetracycline, and ampicillin were added at 50, 100, 10, and 100 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and relevant characteristics

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | ||

| χ2904 | χ2842,thyA748::Tn10 Tcr | Curtiss collection |

| NK6051 | Δ(pro-lac)5 purE79::Tn10 relA1 spoT1 thi-1,Tpr Tcr | 52 |

| β159 | ΔdapB-Km Kmr | 40 |

| SM10 λpir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2Tc::Mu (Kmr) λpir | 48 |

| S. flexneri 2 SFL148 | SC602 aroC::Tn10 Tcr | Stocker collection |

| S. flexneri Y SF114 | aroD::Tn10 Tcr | 21 |

TABLE 2.

S. flexneri 5 strains and relevant characteristics

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Growth requirement(s) | Reference or Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| M90T | Wild type harboring 220-kb invasion plasmid | Nicotinic acid | 44 |

| M90T-Sm | Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant derivative of M90T | Nicotinic acid | 5 |

| ZB2111 | M90T aroB-Ap | Nicotinic acid, Phe, Trp, Tyr, p-aminobenzoate, 2,3-dehydroxybenzoate | This study |

| ZB2102 | M90T aroC::Tn10 transductant of SFL148 donor, Tcr | Arg, Ala, His, Phe, Trp, Tyr, p-aminobenzoate nicotinic acid, 2,3-dehydroxybenzoate | This study |

| ZB2103 | M90T aroD::Tn10 transductant of SF114 donor, Tcr | Phe, Trp, Tyr, p-aminobenzoate, nicotinic acid, 2,3-dehydroxybenzoate | This study |

| ZB2101 | M90T purE::Tn10 transductant of NK6051, Tcr | Nicotinic acid, adenine | This study |

| ZB2106 | M90T ΔpurE derivative of M90T purE::Tn10 | Nicotinic acid, adenine | This study |

| ZB2100 | M90T thyA::Tn10 transductant of χ2904 donor, Tcr | Nicotinic acid, thymine | This study |

| ZB2104 | M90T ΔdapB-Km transductant of β159 donor, Kmr | Nicotinic acid, diaminopimelic acid | This study |

| ZB2112 | M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap | Nicotinic acid, adenine, Phe, Trp, Tyr, p-aminobenzoate, 2,3-dehydroxybenzoate | This study |

| ZB2108 | M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10 transductant of SFL148 donor, Tcr | Nicotinic acid, adenine, Phe, Trp, Tyr, p-aminobenzoate, 2,3-dehydroxybenzoate | This study |

| ZB2109 | M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10 transductant of SF114 donor, Tcr | Nicotinic acid, adenine, Phe, Trp, Tyr, p-aminobenzoate, 2,3-dehydroxybenzoate | This study |

| ZB2107 | M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10 transductant of χ2904 donor, Tcr | Nicotinic acid, adenine, thymine | This study |

Genetic procedures and strain construction.

Generalized transduction with bacteriophage P1 was performed as described by Miller (32). Depending on the marker transduced, transductants were selected on media supplemented with antibiotic or nutrients.

(i) Construction of ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10), ZB2101 (M90T purE::Tn10), ZB2102 (M90T aroC::Tn10), ZB2103 (M90T aroD::Tn10), and ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km).

Each insertion, namely, thyA::Tn10, purE::Tn10, aroC::Tn10, aroD::Tn10, and ΔdapB-Km, was transduced to M90T, using Escherichia coli χ2904 (thyA::Tn10), E. coli NK6051 (purE::Tn10), S. flexneri 2 SFL148 (aroC::Tn10), S. flexneri Y SF114 (aroD::Tn10), and E. coli β159 (ΔdapB-Km) as the respective donors. When Tn10 insertion was used as a selectable marker, transductants were isolated for tetracycline resistance, while kanamycin resistance, encoded by a cartridge inserted into dapB in β159, provided the means for positive selection in the construction of the M90T ΔdapB mutant. The transductants obtained were checked for the acquired auxotrophies: thymine for thyA, adenine for purE, PABA, 3,4-dehydroxybenzoate, tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine for Aro, and diaminopimelic acid for dapB. ZB2101 (M90T purE::Tn10), ZB2102 (M90T aroC::Tn10), ZB2103 (M90T aroD::Tn10), and ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km) were selected to be analyzed in the virulence assays.

(ii) Construction of ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap).

A fragment from nucleotides 580 to 1151 of S. flexneri 5 aroB was amplified by PCR using two primers derived from the corresponding E. coli aroB sequence (for 5′-TAATGAACCAGCT; for 3′-CCATGTAACCAAT) (31). The fragment was cloned in the SmaI site upstream of the lacZ gene in the suicide plasmid vector pLAC1 (5), thus obtaining plasmid pZB211. pZB211 was maintained in E. coli SM10 λpir (48) and then transferred by conjugation into M90T-Sm (5). The transconjugants were selected on plates containing streptomycin and ampicillin. Since pZB211 did not replicate in S. flexneri, the ampicillin-resistant clones arose through homologous recombination between the aroB fragment carried by pZB211 and the corresponding chromosomal aroB. The insertion of pZB211 into the aroB locus was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis with the 478-bp AvaII fragment (from positions 611 to 1089) as a probe. The resulting strain ZB2111 was checked for the acquired auxotrophies on minimal medium.

(iii) Construction of ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE).

To obtain a ΔpurE mutant, the S. flexneri purE::Tn10 strain (ZB2101) was submitted to selection on fusaric acid as described by Bochner et al. (8). This experimental procedure selects strains subject to the Tn10 excision and which have become sensitive to tetracycline. ZB2101 (purE::Tn10) derivatives were assumed to have simultaneously lost the Tn10 insertion and the purE gene, thus becoming tetracycline sensitive and auxotrophic for adenine. About 20 tetracycline-sensitive, fusaric acid-resistant, and adenine auxotrophic strains were chosen for further virulence analysis. ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) was submitted to molecular and phenotypic assays as detailed in Results and then used as recipient in the construction of double mutants. PCR analysis performed with 3′ and 5′ probes derived from the E. coli purE locus sequence confirmed that the purE gene was deleted in ZB2106.

(iv) Construction of the double mutants ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10), ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10), ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10), and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap).

Using ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) as a recipient and χ2904 (E. coli thyA::Tn10), SFL148 (S. flexneri 2 aroC::Tn10), SF114 (S. flexneri Y aroD::Tn10), and ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap), respectively, as donors, the ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10), ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10), ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10), and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) mutants were constructed by P1 generalized transduction as described above.

Virulence assays. (i) HeLa cell culture conditions.

Cells were routinely maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM; GIBCO-BRL) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, Utah) at a concentration of 5%. Twenty-four hours before both multiplication and plaque assay, MEM was supplemented, when necessary, with either thymine, diaminopimelic acid, PABA, or dehydroxybenzoate at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml.

(ii) Infection of HeLa cells.

The HeLa cell invasion assay was performed as described by Hale et al. (16).

(iii) Intracellular multiplication of bacteria in HeLa cells.

Multiplication of bacteria in HeLa cells was assayed as described previously (43), with minor modifications. Nonconfluent monolayers of HeLa cells (8 × 104 to 9 × 104/ml) on 35-mm-diameter dishes were inoculated with bacteria suspended in 2 ml of MEM at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100, centrifuged, and incubated for 40 min at 37°C to allow bacterial entry. Plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and covered with 2 ml of MEM containing gentamicin (50 μg/ml). This point was taken as time zero (T0). Incubation lasted for 5 or 8 h in different experiments. Two plates were removed at each time (T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5 or T1, T3, T6, and T8). One plate was washed three times with PBS and Giemsa stained to calculate the percentage of infected HeLa cells. The other plate was washed five times with PBS to eliminate viable extracellular bacteria. Cells were trypsinized, counted, and then lysed with 0.5% sodium deoxycholate in distilled water. Dilutions of this suspension were plated onto brain heart infusion agar supplemented with various nutrients required by the different auxotrophic mutants.

When infection lasted 12 h, the invasion assay procedure was slightly modified. To allow Shigella entry, dishes containing cells and bacteria were incubated for 2 h without centrifugation. After five washes, cells were covered with 2 ml of MEM supplemented with gentamicin. This was taken as T0. Only two times (T1 and T12), were evaluated. Since only a few cells were found infected after 12 h, we recorded the number of bacteria in the monolayer.

Intracellular survival in the presence of cefotaxime was analyzed by modifying the experimental procedure of the invasion assay. Briefly, HeLa cell monolayers were infected with bacteria; after 2 h postinfection in the presence of gentamicin, two plates for each strain were removed and treated as described above. This was taken as T0. The other plates were washed five times with PBS and covered with 2 ml of MEM supplemented with gentamicin and cefotaxime (300 μg/ml). Cells were incubated in the presence of cefotaxime for 6 h. After this time, the plates were treated to quantify surviving bacteria.

(iv) Plaque assay.

The plaque assay was carried out as originally described by Oaks et al. (37).

(v) Sereny test.

The keratoconjunctivitis assay in guinea pigs was performed as originally described (47), using two challenges, 108 and 109 CFU. The results were evaluated as suggested in a recent study (17).

Phase-contrast micrographs and labeling of bacteria.

Bacteria growing to mid-exponential phase were washed and fixed to polylysine-treated coverslips. IcsA was detected by using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against IcsA followed by a rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody as recently described by Egile et al. (11).

RESULTS

S. flexneri auxotroph construction.

The S. flexneri auxotrophic strains harboring a mutation in either one of the metabolic pathways which lead to the synthesis of (i) aromatic amino acids (M90T aroB-Ap, M90T aroC::Tn10, and M90T aroD::Tn10), (ii) adenine (M90T purE::Tn10), (iii) thymine (M90T thyA::Tn10), and (iv) diaminopimelic acid (M90T ΔdapB-Km) were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. To obtain mutants having more than one auxotrophy, we decided to combine the purE mutation with each of the mutations mentioned in categories i and iii. Therefore, ZB2101 (M90T purE::Tn10) was assessed in the plaque assay and in the Sereny test (at a challenge of 109 CFU) and gave positive results in both tests. To achieve the deletion of the purE locus, ZB2101 was submitted to fusaric acid selection and ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) was chosen for further analysis as detailed in Materials and Methods. ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) produced plaques similar in size and number to those of the parent strain (ZB2101) and gave positive results in the Sereny test. Using ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) as recipient, ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10), ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10), ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10), and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) were constructed by P1 generalized transduction (see Materials and Methods).

Since rough strains are avirulent when tested in a definitive assay system (42), lipopolysaccharide was prepared from each mutant strain. All mutants were found to have a complete O-polysaccharide side chain compared to M90T (data not shown). The ability of Shigella spp. to bind the dye Congo red (Pcr phenotype) has been correlated with their invasiveness (29). All mutants had a Pcr+ phenotype and were able to invade HeLa cell monolayers.

Intracellular multiplication kinetics of ZB2101 (M90T purE::Tn10), ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE), ZB2102 (M90T aroC::Tn10), ZB2103 (M90T aroD::Tn10), ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap), ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10), ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10), and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap).

To evaluate the real rate of intracellular multiplication in each invaded cell, experimental conditions that minimize intercellular spreading were adopted. Thus, by lowering the number of cells (maintaining the MOI of 100), a scattered monolayer consisting of groups of three to four cells was obtained.

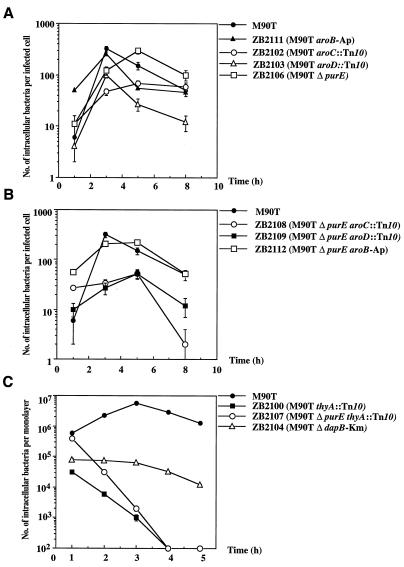

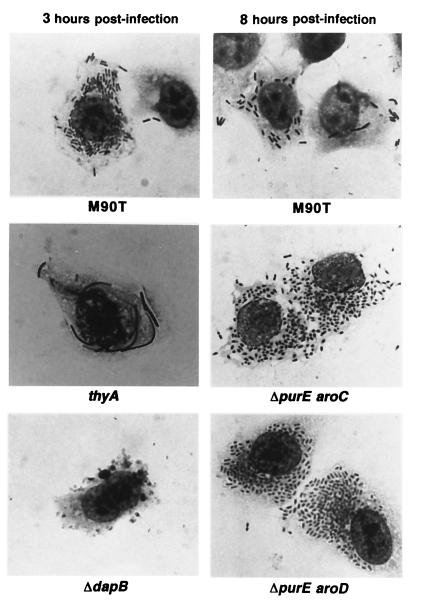

Among the Aro mutants, ZB2111 (aroB) presented an intracellular multiplication kinetics similar to that of the wild-type strain, whereas ZB2103 (aroD) and ZB2102 (aroC) appeared to be altered (Fig. 1A). The mutants’ shape and intracellular distribution did not differ significantly from that of the wild type, as demonstrated by Giemsa staining of intracellular bacteria (data not shown). The multiplication kinetics of the ΔpurE strain (and that of the parent purE::Tn10 strain) was similar to that of M90T except for the peak of the maximum number of intracellular bacteria that seemed to be delayed (Fig. 1A). As reported for the Aro− strains, the double mutants ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10), ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10), and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) had different capabilities to proliferate intracellularly. ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) behaved like ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap), whereas ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10) and ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10) (Fig. 1B) multiplied at a very low rate. Usually, the invasion cycle of the wild-type strain on HeLa cell monolayers does not last more than 6 to 7 h of infection (43). After this time, only a few bacteria are seen in the infected cells. In contrast, Giemsa staining of HeLa cells infected with either ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10) or ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10) (Fig. 2) showed that their cytoplasm was full of bacteria even after 8 h of invasion. At an MOI of 10 instead of 100, the behavior of these strains did not change and their intracellular multiplication kinetics remained alike.

FIG. 1.

Intracellular growth kinetics of S. flexneri auxotrophic mutants. (A) Intracellular bacterial growth of M90T, ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap), ZB2102 (M90T aroC::Tn10), ZB2103 (M90T aroD::Tn10), and ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) during 8 h of incubation postinfection; (B) intracellular bacterial growth of M90T, ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10), ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10), and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) during 8 h of incubation postinfection; (C) intracellular bacterial growth of M90T, ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10), ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10) and ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km) during 5 h postinfection. Datum points represent the mean (± standard deviation of the mean) of the number of bacteria calculated in five separate invasion assays.

FIG. 2.

Giemsa stains of HeLa cells infected by Shigella strains. HeLa cells infected with Shigella strains were fixed and stained after incubation at 37°C with M90T, ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10), and ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km) for 3 h and with M90T, ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10) and ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10) for 8 h. Corresponding strains: thyA, ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10); ΔdapB, ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km); ΔpurE aroC, ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10); ΔpurE aroD, ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10).

Intracellular growth of ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10), ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km), and ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10).

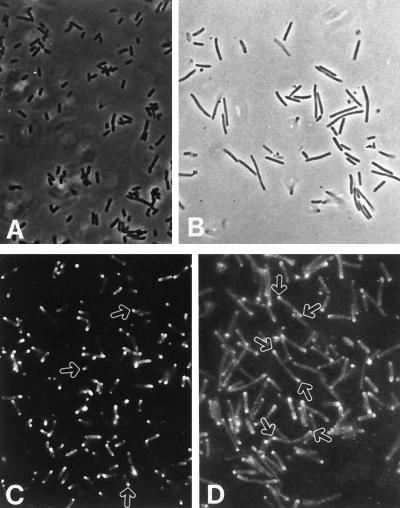

ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10), ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10), and ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km) did not appear to survive in host cells, making it impossible to evaluate the number of intracellular bacteria per infected cell. Figure 1C shows the number of bacteria in the monolayer. Although the number of intracellular ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10) and ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10) cells decreased considerably after 3 h postinfection, the bacteria were still observable within the cytoplasm of infected cells after this time (Fig. 2); they had a characteristic shape (long filaments). This form arose from the limiting availability of thymine in the infected cell cytoplasm. In fact, bacteria grown to mid-exponential phase in a medium unsupplemented by thymine exhibited this characteristic shape, as shown in Fig. 3A.

FIG. 3.

Surface distribution of IcsA. (A and B) Phase-contrast microphotographs of M90T and ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10), respectively; (C and D) immunofluorescence labeling of M90T and ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10), using an anti-IcsA antiserum. Bacteria were grown to mid-exponential phase in tryptic soy broth unsupplemented with thymine. Arrows indicate the areas where IcsA is polarized on the surface of M90T (C) and ZB2100 (D).

ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km) showed intracellular multiplication kinetics similar to that of ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10) and ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10) (Fig. 3), even though it did not produce filaments, and bacteria appeared engulfed in vesicles or in protrusions of the HeLa cell membranes (Fig. 2).

To test whether the impairment in intracellular multiplication observed with these three auxotrophs was due to low levels of thymine and diaminopimelic acid, HeLa cells were treated with either thymine or diaminopimelic acid as detailed in Materials and Methods. The invasion assays were performed in the presence of these substances. The addition of diaminopimelic acid to the cell medium restored the ability of ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km) to grow intracellularly, whereas thymine restored a correct shape of intracellular ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10) and ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10) along with their ability to proliferate (data not shown).

The generation times of all mutants were calculated after 3 and 6 h of infection and are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Virulence phenotypes of the auxotrophic mutants

| Strain | Intracellular generation time (min)a

|

Plaque assay | Sereny testd

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt Ab | Expt Bc | 108 CFU | 109 CFU | ||

| M90T | 41.3 ± 3.9 | 75 ± 5.1 | + | 3 | 3 |

| ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap) | 59.7 ± 7.1 | 119 ± 8.5 | + | 2f | 3f |

| ZB2102 (M90T aroC::Tn10) | 90.6 ± 9.3 | 178 ± 16.9 | − | 0 | 0 |

| ZB2103 (M90T aroD::Tn10) | 40.8 ± 5.4 | 126 ± 9.9 | +g | 0 | 0 |

| ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) | 52.0 ± 2.5 | 98.1 ± 5.3 | + | 2f | 3 |

| ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10) | NDe | ND | − | 0 | 0 |

| ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km) | ND | ND | − | 0 | 0 |

| ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) | 59.3 ± 7.2 | 122.9 ± 12.4 | + | 2f | 2f |

| ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10) | 129.8 ± 8.1 | 302 ± 15.0 | − | 0 | 0 |

| ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10) | 130.6 ± 9.7 | 154.0 ± 14.5 | − | 0 | 0 |

| ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10) | ND | ND | − | 0 | 0 |

Mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments.

Calculated during the first 3 h of intracellular growth.

Calculated during the first 6 h of intracellular growth.

The induction of keratoconjunctivitis was evaluated 48 h after bacterial challenge with 108 or 109 CFU. The symptoms were estimated according to the ratings suggested by Hartman et al. (17).

ND, not determined.

Reaction delayed of 18 h.

Small plaques.

Survival of the mutants after 12 h of infection and in the presence of cefotaxime.

Only strains that had an intracellular multiplication kinetics similar to that of the wild-type strain were able to survive after 12 h of infection, as shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Number of intracellular bacteria within the HeLa cell monolayers at 1, 6, and 12 h postinfection and 6 h postinfection in the presence of cefotaxime

| Strain | CFU/ml (log10)a per HeLa cell monolayer at indicated time (h) postinfection

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 6 + cefotaxime | 12 | |

| M90T | 330.0 ± 23.6 | 1,116.7 ± 236.29 | 0.016 ± 0.005 | 12.975 ± 4.582 |

| ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) | 466.7 ± 48.5 | 893.3 ± 52.4c | 0.109 ± 0.032 | 15.250 ± 2.986 |

| ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10) | 33.33 ± 3.0 | 0.044 ± 0.03 | 0.107 ± 0.024 | NGb |

| ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km) | 86.67 ± 8.5 | 2.173 ± 1.514 | 2.303 ± 0.135 | NG |

| ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap) | 300.0 ± 75.9 | 916.7 ± 80.71 | 0.036 ± 0.006 | 6.680 ± 2.523 |

| ZB2102 (M90T aroC::Tn10) | 216.7 ± 25.5 | 383.3 ± 99.62 | 4.360 ± 1.122 | NG |

| ZB2103 (M90T aroD::Tn10) | 94.33 ± 49.3 | 620.0 ± 45.6 | 0.230 ± 0.055 | 3.225 ± 1.330d |

| ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) | 390.0 ± 11.5 | 526.7 ± 29.14 | 0.221 ± 0.020 | 4.510 ± 1.957 |

| ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10) | 633.3 ± 101.5 | 1,187.0 ± 232.0 | 2.175 ± 0.902 | NG |

| ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10) | 360.0 ± 101.5 | 860.0 ± 79.05 | 1.735 ± 0.201 | NG |

| ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10) | 251.0 ± 114.2 | 0.084 ± 0.011 | 0.211 ± 0.022 | NG |

Mean ± standard deviation from three separate invasion assays.

NG, no growth was observed.

P = 0.0081 (Student’s t test).

P = 0.0145 (Student’s t test).

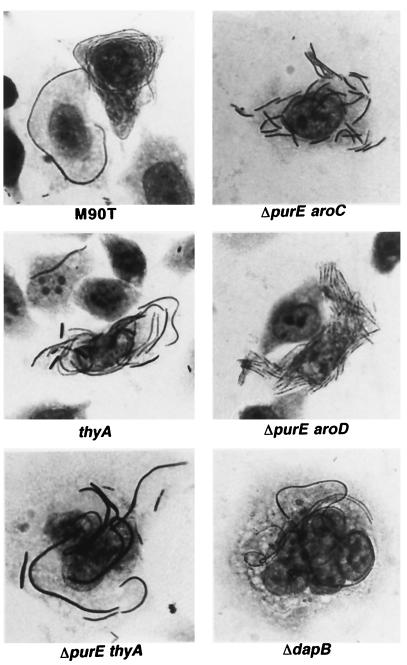

The antibiotic cefotaxime kills actively replicating bacteria, thereby selecting mutants which are unable to multiply intracellularly. In preliminary assays, we observed that a 6-h exposure to cefotaxime was necessary to kill the bacteria multiplying intracellularly and to select those unable to do so. Hence, survival in the presence of cefotaxime can be considered a good parameter to identify those strains that cannot replicate intracellularly. The results obtained are presented in Table 4. Figure 4 shows the Giemsa staining of intracellular shigellae grown in the presence of cefotaxime.

FIG. 4.

Giemsa stains of HeLa cells infected with Shigella strains in the presence of cefotaxime. HeLa cells were infected with Shigella auxotrophic mutants, and incubation postinfection was carried out in cell medium supplemented with the antibiotic cefotaxime (300 μg/ml). Cells were fixed and stained after 6 h of incubation at 37°C. Corresponding strains: ΔpurE aroC, ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10); ΔpurE aroD, ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD::Tn10); thyA, ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10); ΔpurE thyA, ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10); ΔdapB, ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km).

Plaque assay and intercellular movement.

The plaque assay reflects the ability of shigellae to spread within a cell monolayer and to damage host cells. The results of this process are detected as a plaque, i.e., a zone of dead cells destroyed by bacterial infection (37). As expected, ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap) and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) were positive in this assay. ZB2103 (M90T aroD::Tn10), at an MOI of 10, was seen to form tiny plaques. All other mutants were negative (Table 3).

The addition of thymine or diaminopimelic acid to the cell medium restored the ability to form plaques for ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10), ZB2107 (M90T ΔpurE thyA::Tn10), and ZB2104 (M90T ΔdapB-Km). Additionally, when the cell medium was supplemented with PABA, ZB2102 (M90T aroC::Tn10), ZB2103 (M90T aroD::Tn10), ZB2108 (M90T ΔpurE aroC::Tn10), and ZB2109 (M90T ΔpurE aroD:Tn10) gave a positive result in this test. The number and size of plaques were similar to those of the wild-type strain.

To determine whether the intercellular movement of the auxotrophic mutants was impaired, we assessed their capability to colonize the Caco-2 islets. S. flexneri strains enter the Caco-2 islets only through the basolateral pole of these cells (33). Only bacteria able to move intracellularly and from cell to cell can reach the center of the infected islet without passage in the extracellular medium. All mutants tested except one were able to move in the Caco-2 islets to various degrees (data not shown). The only exception was the ΔdapB mutant. Since IcsA is polarized on the bacterial cell surface, we also checked its distribution on the filament surface of ZB2100 (M90T thyA::Tn10) by immunostaining IcsA with a polyclonal antibody raised against it. After 2 h of bacterial growth in thymine-free medium, different forms of these bacteria coexisted. The immunofluorescence analysis revealed that most of the bacteria producing filaments still polarized IcsA on their surface (Fig. 3B).

Sereny test analysis.

Some of the mutations analyzed in this study have been already tested in other Shigella spp. or serotypes. SL114 (S. flexneri Y aroD::Tn10) and an S. flexneri 2 thymine auxotrophic mutant do not give a positive result in the Sereny test (21, 38). In this study, the Sereny test was performed with two challenges (108 and 109 CFU). When 109 bacteria were inoculated (Table 3), ZB2101 (M90T purE::Tn10), ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE), ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap), and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) induced a keratoconjunctivitis similar to that provoked by M90T. The only exception was ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap), which induced the appearance of symptoms about 18 h later than did the wild type. The intensity of the inflammatory reaction was weak. The symptoms induced by ZB2101 (M90T purE::Tn10) and ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE) were delayed, but the intensity of the keratoconjunctivitis was the same as that observed with M90T.

On the other hand, when an inoculum of 108 bacteria was used, the appearance of symptoms induced by ZB2101 (M90T purE::Tn10), ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurE), ZB2111 (M90T aroB-Ap), and ZB2112 (M90T ΔpurE aroB-Ap) was delayed for about 18 h, and the severity of conjunctivitis was mild (rating 2). The results are summarized in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have constructed and analyzed a group of S. flexneri 5 M90T auxotrophic mutants that harbor one or two mutations in the metabolic pathways which lead to the synthesis of aromatic amino acids, nucleotides, and diaminopimelic acid (aroB, aroC, aroD, purE, thyA, dapB, purE aroB, purE aroC, purE aroD, and purE thyA). These mutants proliferate poorly in media where nutrients are present in limited amounts. Since shigellae meet similar conditions in host tissues during natural infection, these strains were supposed to be potentially impaired in intracellular multiplication.

The Aro mutants show different virulence attenuated phenotypes.

Various Aro mutants selectively inactivated in either one or two steps of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis have been obtained by different groups (19, 22, 35, 51). The Aro mutants are auxotrophs for aromatic amino acids, PABA (a precursor of folic acid), and dehydroxybenzoic acid (a precursor for the iron-binding enterochelin).

We constructed three Aro mutants, each carrying a mutation in aroB, aroC, or aroD. Although all of these mutants show the same nutritional requirements in laboratory media, they have different degrees of virulence in vitro as well as in vivo. aroB encodes 3-dehydroquinate (DHQ) synthase, which converts 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate to DHQ. DHQ production is an early reaction in chorismate biosynthesis. S. flexneri aroB shows levels of virulence similar to those of the wild-type parent strain when assessed in tissue culture virulence tests. It proliferates in host cells with a generation time close to that of M90T and is positive in the plaque assay. Like other Aro mutants, M90T aroB needs PABA and aromatic amino acids to grow in culture media. Eukaryotic cells do not synthesize PABA and need exogenous folic acid that usually is incorporated as folate into folyl polyglutamate (41). Folate polyglutamate is subject to a certain degree of turnover in cultured human cells (18). Hence, intracellular aroB mutants might scavenge some intermediate metabolite of folate turnover to be used in chorismate biosynthesis to overcome the step controlled by the aroB product. Additionally, 3,7-dideoxy-d-threo-hepto-2,6-diulosonic acid, which is a precursor of DHQ, can be converted chemically to DHQ without any enzymatic reaction (3).

M90T aroD shows characteristics close to those described by Lindberg et al. (21, 22) and Karnell et al. (19) for S. flexneri Y aroD and S. flexneri 2a aroD, respectively (Table 3). M90T aroD exhibits an intracellular generation time which is slightly greater than that of M90T (126 ± 9.9 min versus 75 ± 5.1 min after 6 h of infection), and its intracellular survival is similar to that of M90T. At an MOI of 10, M90T aroD is positive in the plaque assay, though the zones of cell necrosis are smaller than those induced by the parent strain. aroD encodes DHQ dehydratase, which introduces the first double bound in the aromatic ring, thus converting DHQ to 3-dehydroshikimate. Several intermediate metabolites separate 3-dehydroshikimate from the final product, chorismate. Therefore, intracellular aroD could utilize some intermediate metabolite of folate turnover to synthesize chorismate, as suggested above for the aroB strain.

M90T aroC is severely affected in intracellular multiplication, as shown by (i) its very high intracellular doubling time (178 ± 16.9 min) and (ii) its ability to survive intracellularly in the presence of cefotaxime. aroC encodes the last enzyme involved in chorismate biosynthesis. This enzyme converts 5-enolpyruvoylshikimate-3-phosphate to chorismate by introducing the second double bound in the aromatic ring. In contrast to the other two Aro mutants, which harbor mutations in genes encoding enzymes involved in early steps, this strain is mutagenized in the last reaction yielding chorismate. Consequently, it cannot use eukaryotic cell metabolites to synthesize this molecule. Therefore, in the presence of low amounts of chorismate and/or PABA, its proliferation within host cells is greatly impaired.

The S. flexneri 2 aroA mutant created by Noriega et al. (35) was described as exhibiting a reduced intracellular growth and eliciting only a transient and slight inflammatory response in the Sereny test. The aroA product is the 5-enolpyruvoylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase involved in the penultimate reaction of the chorismate production. The analysis of both mutants, S. flexneri 5 aroC and S. flexneri 2 aroA, suggests that mutations in the terminal steps of the chorismate biosynthesis pathway confer a serious virulence attenuation. Our results indicate PABA as a key requirement for intracellular shigellae. All Aro simple and double mutants showing virulence attenuation in vitro can be restored to full virulence by treating tissue culture cells with PABA. Since folate is a normal constituent of cell culture media, this finding also suggests that shigellae cannot or may less easily utilize folate than PABA.

Results obtained in vivo reflect those observed in vitro. However, PABA and Aro products appear to be less available in host tissues than in infected cytoplasms. In fact, the aroB mutant provokes a moderate inflammatory response when administered at both low and high dose levels, while aroD and aroC strains do not elicit keratoconjunctivitis in the experimental conditions used. This observation has also been confirmed by Bacon et al., who demonstrated that Salmonella PABA auxotrophs do not grow in minimal medium supplemented with peritoneal fluid (6).

Thymine but not adenine auxotrophy lowers virulence levels.

The purE locus includes the purE1 and purE2 genes, which encode AIR (5′-phosphoribosyl-5-aminoimidazole) carboxylase, which is an intermediate step in IMP biosynthesis. S. flexneri purE mutants do not grow in laboratory media in the absence of adenine, but they proliferate intracellularly at the same rate as the parent strain. They are positive in the plaque assay and induce a strong inflammatory reaction in the Sereny test when administered at high doses (109 CFU). At a low inoculum (108 CFU), the reaction is mild and delayed. Nucleotides present in the growth medium may be utilized as nucleic acid precursors by bacteria only if they are dephosphorylated to nucleosides by periplasmic nucleotidases (54). Such an activity could reduce the intracellular multiplication of purE mutants. Since this is not the case (as demonstrated through tissue culture multiplication assay), it is conceivable that salvage pathways enable shigellae to utilize preformed nucleobases or nucleosides available within eukaryotic cytoplasm. This issue is not confirmed for Shigella guanine auxotrophs since, as described by Noriega et al. (36), mutants unable to synthesize guanine (harboring guaB-A deletion) show a dramatic reduction of virulence. In our laboratory, a purHD deletion mutant unable to synthesize hypoxanthine exhibits the same virulence attenuation pattern (6a). In contrast to these results, a Listeria monocytogenes adenine auxotrophic strain has been found to be severely attenuated (26). These data indicate that guanine but not adenine availability is a key factor influencing the virulence of shigellae. We realized that by combining adenine auxotrophy (ΔpurE) with one of the Aro mutations (in this way obtaining strains harboring either ΔpurE aroB, ΔpurE aroC, ΔpurE aroD mutations), virulence attenuation was potentiated. This is not an unexpected result since one of the final reactions yielding IMP synthesis requires 10-formyltetrahydrofolate, which is produced from PABA. Therefore, the addition of an Aro mutation strengthens the effect of the purE deletion.

Different groups reported that Shigella thymine auxotrophs do not form plaques in tissue culture and are avirulent in monkeys (4, 38). In our work, we introduced a thyA mutation into M90T. The reaction governed by thyA is a key step in thymine biosynthesis. thyA encodes thymidylate synthase, which converts dUMP to dTMP. E. coli thyA mutants are high-thymine-requiring strains which need thymine at the concentration of about 150 mM to grow in laboratory media. M90T thyA also requires a similar thymine concentration to grow. M90T thyA mutants are unable to replicate intracellularly. As a consequence, it is possible to recover only a few bacteria by lysing infected cells. Nevertheless, bacteria are observable within the cytoplasm, where they form long filaments. thyA and ΔpurE thyA mutants were restored to the ability to elicit a positive plaque assay by adding thymine to the tissue culture cell. This result suggests that this molecule is also essential to full virulence.

Introduced mutations selectively alter the interactions of shigellae with eukaryotic cells.

Main virulence-associated phenotypes such as invasion (34) and spreading (14) are related to the bacterial cell division process. Hence, shigella mutants having high generation times will be supposedly altered in phenotypes which rely on cell division. aroC, ΔpurE aroC, and ΔpurE aroD mutants exhibiting high generation times (Table 3) are negative in the plaque assay. However, within 3 h of infection these strains move from the peripheral cells to those centrally located through the Caco-2 islets. This is apparently in contrast to the finding of the plaque assay. We observed that the generation time of the auxotrophic mutants usually increases starting from 3 to 6 h of infection. This growth retardation could be due to the fact that the intrabacterial stocks of nutrients are exploited. Thus, as the generation time increases, bacteria move slowly, as shown by (i) the number of infected HeLa cells, which does not change after 3 h of infection (data not shown), and (ii) the inability to form observable plaques of lysis. As confirmation to this hypothesis, the aroD mutant, which has a slightly higher replication rate than the wild type, still disseminates within HeLa cell tissue cultures and thus is positive in the plaque assay.

M90T thyA at first appears to move from an infected cell to an adjacent one. In fact, after 2 h in the absence of thymine, it still exhibits a polar distribution of IcsA, as shown by the immunostaining of this molecule on the bacterial surface. After a few generations, the physical shape and size of filamentous forms prevent intercellular spreading, possibly by altering the correct actin tail production on the bacterial cell surface. A similar phenotype has been described for the ispA S. flexneri mutant, which also exhibits a filamentous form (24). The inability to survive and move intraintercellularly supports the negativity in the plaque assay shown by the thyA mutants.

The dapB mutant does not form peptidoglycan in the absence of diaminopimelate. When diaminopimelate is not added to culture media, dapB mutants continue to proliferate without forming a correct peptidoglycan until they burst. Since diaminopimelate is not a constituent of eukaryotic cells, the majority of bacteria carrying the dapB mutation burst shortly after HeLa cell invasion. By exploding, they might release molecules (IpaA and IcsA) and/or molecular complexes known to interact with cell structures like actin and actin-binding proteins (7, 12, 13, 49, 50). This massive release of toxic molecules might account for the structural changes induced by dapB mutants within host cells (Fig. 3).

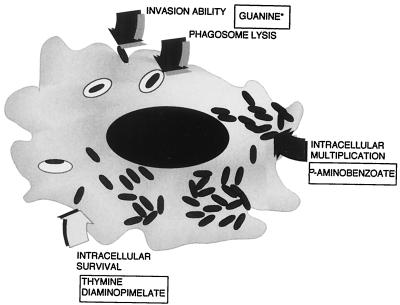

On the basis of these data, we can indicate a group of molecules present, in a limited amount, within infected cytoplasms. These molecules are necessary to perform the various steps of epithelial cell invasion by shigellae, as summarized in Fig. 5. On the other hand, this study may also contribute to the characterization of mutations to be associated in Shigella vaccine candidate construction. To date, in order to obtain minimal reactogenicity and maximal immunogenicity, most Shigella vaccine candidates have carried the icsA deletion associated with another mutation like aroA, thyA, iuc, ompB, and guaA-B (35, 36, 45, 46, 53). The combination of these mutations often hyperattenuates Shigella virulence, thereby affecting the immunogenicity of candidates. A detailed knowledge of each mutation’s role in terms of its effects on the bacterial interaction with a single host cell and host tissues is a key step in vaccine design and will provide the tools essential to construct a new generation of Shigella vaccines.

FIG. 5.

Possible outline of the nutritional requirements of S. flexneri during cell invasion. The ability to invade and/or to escape from the phagocytic vacuole depends on the bacterial synthesis of guanine (36). Intracellular multiplication is modulated by the availability of PABA, whereas intracellular survival of shigellae requires thymine and diaminopimelate. ∗, the guanine requirement is an issue that arises from the study of Noriega et al. (36) and from our unpublished results.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Stocker, R. Curtiss III, and C. Richaud for providing strains. We are also pleased to acknowledge P. Sansonetti’s laboratory team for helpful discussion and K. Pepper for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by an EC biotechnology program (BIO2-CT92-0134) and by a WHO/GPV program (V27/181/79). A. Cersini benefited from a fellowship by Fondazione Istituto Pasteur-Cenci Bolognetti of Rome.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam T, Arpin M, Prevost M C, Gounon P, Sansonetti P J. Cytoskeletal rearrangements during entry of Shigella flexneri into HeLa cells. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:367–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam T, Giry M, Boquet P, Sansonetti P J. Rho-dependent membrane folding causes Shigella entry into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:3315–3321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adlersberg M, Sprinson D B. Synthesis of 3,7-dideoxy-d-threo-hepto-2,6-diulosonic acid: a study in 5-dehydroquinic acid formation. Biochemistry. 1964;3:1855–1860. doi: 10.1021/bi00900a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed Z U, Mahfuzur R S, Sack D A. Protection of adult rabbits and monkeys against shigellosis by oral immunization with a thymine-requiring and temperature-sensitive mutant of Shigella flexneri Y. Vaccine. 1990;8:153–158. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90139-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alloui A, Mounier J, Prevost M-C, Sansonetti P J, Parsot C. icsB: a Shigella flexneri virulence gene necessary for the lysis of protrusions during intercellular spread. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1605–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacon G A, Burrows T W, Yates M. The effects of biochemical mutation on the virulence of Bacterium typhosum: the loss of virulence of certain mutants. Br J Exp Pathol. 1951;32:85–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Bernardini, M. L., et al. Unpublished results.

- 7.Bernardini M L, Mounier J, d’Hauteville H, Coquis-Rondon M, Sansonetti P J. Identification of icsA, a plasmid locus of Shigella flexneri that governs intra and intercellular spread through interaction with F-actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3867–3871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bochner B R, Huang H C, Schieven G L, Ames B N. Positive selection for loss of tetracycline resistance. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:926–933. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.926-933.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cossart P. Actin-based bacterial motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:94–101. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehio C, Prevost M C, Sansonetti P J. Invasion of epithelial cells by Shigella flexneri induces tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin by a pp60-src mediated signalling pathway. EMBO J. 1995;14:2471–2482. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egile C, d’Hauteville H, Parsot C, Sansonetti P J. SopA, the outer membrane protease responsible for polar localization of IcsA in Shigella flexneri. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1063–1073. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2871652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg M, Barzu O, Parsot C, Sansonetti P J. Actin-binding and unipolar localization of IcsA, a Shigella flexneri protein involved in intracellular movement. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2189–2196. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2189-2196.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg M B, Theriot A J. Shigella flexneri surface protein IcsA is sufficient to direct actin-based motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6572–6576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg M B, Theriot J A, Sansonetti P J. Regulation of surface presentation of IcsA, a Shigella protein essential to intracellular movement and spread, is growth phase dependent. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5664–5668. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5664-5668.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hale T L. Genetic bases of virulence in Shigella species. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:206–224. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.2.206-224.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hale T L, Morris R E, Bonventre P F. Shigella infection of Henle intestinal epithelial cells: role of the host cell. Infect Immun. 1979;24:887–894. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.3.887-894.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartman A B, Powell C J, Schultz C L, Oaks E V, Eckels K H. Small-animal model to measure efficacy and immunogenicity of Shigella vaccine strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4075–4083. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.4075-4083.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilton J C, Cooper B A, Rosenblatt D S. Folate polyglutamate synthesis and turnover in cultured human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8398–8403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karnell A, Li A, Zhao C R, Karlsson K, Minh N B, Lindberg A A. Safety and immunogenicity study of the auxotrophic Shigella flexneri2a vaccine SFL1070 with a deleted aroD gene in adult Swedish volunteers. Vaccine. 1995;13:88–99. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)80017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labrec E H, Schneider H, Magnani T J, Formal S B. Epithelial cell penetration as an essential step in pathogenesis of bacillary dysentery. J Bacteriol. 1964;88:1503–1518. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.5.1503-1518.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg A A, Kärnell A, Stocker B A D, Katakura S, Sweiha H, Reinholt F. Development of an auxotrophic oral live Shigella flexneri vaccine. Vaccine. 1988;6:1946–1950. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(88)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindberg A A, Kärnell A, Pal T, Sweiha H, Hultenby K, Stocker B A D. Construction of an auxotrophic Shigella flexneri strain for use as a live vaccine. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90030-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linde K, Dentchev V, Bondarensko V, Marinova S, Randhagen B, Bratoyeva M, Tsvetanov Y, Romanova Y. Live Shigella flexneri 2a and Shigella sonnei I vaccine candidate strains with two attenuating markers. Construction of vaccine candidate strains with retained invasiveness but reduced intracellular multiplication. Vaccine. 1990;8:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90173-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacSiomoin R A, Nakata N, Murai T, Yoshikawa M, Tsuji H, Sasakawa C. Identification and characterization of ispa, a Shigella flexneri chromosomal gene essential for normal in vivo cell division and intercellular spreading. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:599–609. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.405941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makino S, Sasakawa C, Kamata K, Kurata T, Yoshikawa M. A genetic determinant required for continuous reinfection of adjacent cells on large plasmid in Shigella flexneri 2a. Cell. 1986;46:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90880-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marquis H, Bouwer H G, Hinrichs D J, Portnoy D A. Intracytoplasmic growth and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes auxotrophic mutants. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3756–3760. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3756-3760.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathan M M, Mathan M V. Ultrastructural pathology of the rectal mucosa in Shigella dysentery. Am J Pathol. 1986;123:25–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurelli A T, Baudry B, d’Hauteville H, Hale T L, Sansonetti P J. Cloning of plasmid DNA sequences involved in invasion of HeLa cells by Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 1985;49:164–171. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.1.164-171.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maurelli A T, Blackmon B, Curtiss R., III Temperature-dependent expression of virulence genes in Shigella species. Infect Immun. 1984;43:397–401. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.195-201.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ménard R, Sansonetti P J, Parsot C. Non polar mutagenesis of ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5899–5906. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5899-5906.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Millar G, Coggins J R. The complete aminoacid sequence of 3-dehydroquinate synthase of Escherichia coli K-12. FEBS Lett. 1986;200:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mounier J, Vasselon T, Hellio R, Lesourd M, Sansonetti P J. Shigella flexneri enters human colonic Caco-2 epithelial cells through the basolateral pole. Infect Immun. 1992;60:237–248. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.237-248.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mounier J, Bahrani F K, Sansonetti P J. Secretion of Shigella flexneri Ipa invasins on contact with epithelial cells and subsequent entry of the bacterium into cells are growth stage dependent. Infect Immun. 1997;65:774–782. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.774-782.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noriega F R, Wang J Y, Losonsky G, Maneval D R, Hone D M, Levine M M. Construction and characterization of attenuated ΔaroA and ΔicsA Shigella flexneri strain CVD 1203, a prototype live oral vaccine. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5168–5172. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5168-5172.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noriega F R, Losonsky G, Lauderbaugh C, Liao F M, Wang J Y, Levine M M. Engineered ΔguaB-A ΔvirG Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1205: construction, safety, Immunogenicity, and potential efficacy as a mucosal vaccine. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3055–3061. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3055-3061.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oaks E V, Wingfield M E, Formal S B. Plaque formation by virulent Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 1986;48:124–129. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.1.124-129.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okada N, Sasakawa C, Tobe T, Yamada M, Nakai S, Talukder K A, Komatsu K, Kanegasaki S, Yoshikawa M. Virulence-associated chromosomal loci of Shigella flexneri identified by random Tn5 insertion mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsot C, Sansonetti P J. Invasion and pathogenesis of Shigella infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;209:25–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85216-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richaud C, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Pochet S, Johnson E J, Cohen G N, Marliere P. Directed evolution of biosynthetic pathways. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26827–26835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rong N, Selhub J, Goldin B R, Rosenberg I H. Bacterially synthesized folate in rat large intestine is incorporated into host tissue folyl polyglutamate. J Nutr. 1991;121:1955–1959. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.12.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadlin C R, Lampel K A, Keasler S P, Goldberg M B, Stolzer A L, Maurelli A T. Avirulence of rough mutants of Shigella flexneri: requirement of O antigen for correct unipolar localization of IcsA in the bacterial outer membrane. Infect Immun. 1995;63:229–237. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.229-237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sansonetti P J, Ryter A, Clerc P, Maurelli A T, Mounier J. Multiplication of Shigella flexneri within HeLa cells: lysis of the phagocytic vacuole and plasmid-mediated contact hemolysis. Infect Immun. 1986;51:461–469. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.461-469.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sansonetti P J, Kopecko D J, Formal S B. Involvement of a plasmid in the invasive ability of Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 1982;35:852–860. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.852-860.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sansonetti P J, Arondel J, Fontaine A, d’Hauteville H, Bernardini M L. ompB (osmo-regulation) and icsA (cell-to-cell spread) mutants of Shigella flexneri: vaccine candidates and probes to study the pathogenesis of shigellosis. Vaccine. 1991;9:416–422. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90128-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sansonetti P J, Arondel J. Construction and evaluation of a double mutant of Shigella flexneri as a candidate for oral vaccination against shigellosis. Vaccine. 1989;7:416–422. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(89)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sereny B. Experimental Shigella conjunctivitis. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung. 1955;2:293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki T, Saga S, Sasakawa C. Functional analysis of Shigella VirG domains essential for interaction with vinculin and actin-based motility. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21878–21885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tran V N, Ben-Ze’ev G, A, Sansonetti P J. Modulation of bacterial entry in epithelial cells by association between vinculin and the Shigella IpaA invasin. EMBO J. 1997;10:2703–2717. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verna N K, Lindberg A A. Construction of aromatic dependent Shigella flexneri 2a live vaccine candidate strains: deletion mutations in the aroA and the aroD genes. Vaccine. 1991;9:6–9. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90308-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wanner A, Barry L. Novel regulatory mutants of the phosphate regulon in E. coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1986;191:39–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshikawa M, Sasakawa C, Okada N, Takasaka M, Nakayama M, Yoshikawa Y, Kohno A, Danbara H, Nariuchi H, Shimada H, Toriumi M. Construction and evaluation of a virG thyA double mutant of Shigella flexneri 2a as a candidate live-attenuated oral vaccine. Vaccine. 1995;13:1436–1440. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimmerman H. 5′-Nucleotididase: molecular structure and functional aspects. Biochem J. 1992;285:345–365. doi: 10.1042/bj2850345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]