Abstract

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals in most countries face strong stigma and often rely on affirmative mental health care to foster coping and resilience. We tested an LGBTQ-affirmative mental health training for psychologists and psychiatrists by comparing in-person versus online modalities and the added benefit of supervision. Participants were randomized to a two-day training either in-person (n = 58) or via live-stream online broadcast (n = 55). Outcomes were assessed at baseline and 5, 10, and 15 months posttraining. Optional monthly online supervision was offered (n = 47) from months 5 to 15. Given the substantial need for LGBTQ-affirmative expertise in high-stigma contexts, the training took place in Romania, a Central-Eastern European country with some of the highest LGBTQ stigma in Europe. Participants (M age = 35.1) were mostly cisgender female (88%) and heterosexual (85%). Trainees, regardless of whether in-person or online, reported significant decreases from baseline to 15-month follow-up in implicit and explicit bias and significant increases in LGBTQ-affirmative clinical skills, beliefs, and behaviors. LGBTQ-affirmative practice intentions and number of LGBTQ clients did not change. Participants who attended at least one supervision session demonstrated greater reductions in explicit bias and increases in LGBTQ-affirmative behaviors from baseline to 15-month follow-up than participants who did not attend supervision. LGBTQ-affirmative mental health training can efficiently and sustainably improve LGBTQ competence and reduce provider bias in high-stigma contexts. Future research can identify additional ways to encourage mental health providers’ outreach to LGBTQ clients in need of affirmative care.

Keywords: discrimination, implicit bias, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ), mental health, provider training intervention

Stigma generates excess stress and depletes coping abilities for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals worldwide (Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer et al., 2008) and is associated with adverse physical (Kecojevic et al., 2012; Poteat et al., 2018) and mental health (Ferlatte et al., 2019; Shipherd et al., 2010; Wilton et al., 2018). In mental health care contexts, stigma generates provider mistrust (Ferlatte et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2020) and other barriers to accessing LGBTQ-affirmative services (Veltman & Chaimowitz, 2014). LGBTQ individuals’ negative interactions with providers have been associated with reduced health care engagement (James et al., 2016; Li et al., 2015), while lack of LGBTQ-specific or affirming expertise often results in inadequate and/or withheld treatment (Calabrese et al., 2018; James et al., 2016). These barriers are even stronger in settings with high anti-LGBTQ structural stigma, defined as discriminatory laws, policies, and attitudes that systematically constrain the life chances of the stigmatized (Hatzenbuehler, 2016).

Research shows that health care providers internalize and enact societal biases toward stigmatized populations (Van Ryn & Fu, 2003), and these biases are associated with inaccurate diagnose and, inadequate treatment (Strakowski et al., 2003), and poor outcomes (Fincher et al., 2004). Provider bias can be explicit (e.g., refusal of care) and implicit (e.g., unconscious beliefs; Foglia & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2014). However, a large longitudinal study of medical trainees showed that bias is modifiable; medical students who reported greater contact with LGBTQ persons in the final semester of medical school experienced decreased explicit and implicit bias during residency (Wittlin et al., 2019). Similarly, implicit bias by medical students toward another stigmatized population—African Americans—decreased after exposure to formal cultural competency curriculum, informal curriculum via medical school climate toward race, role modeling, and favorable interracial contact (van Ryn et al., 2015).

Interventions are emerging to facilitate bias reductions in health care. One intervention that trained primary care clinic staff in transgender health competency and clinic preparedness found significant decreases in negative attitudes toward transgender patients, and increases in transgender-specific clinical skills, awareness of transphobic behaviors, and practice readiness (Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2016). Another study evaluated a transgender competency training for health care providers in correctional settings (White Hughto et al., 2017) and found that willingness to provide gender-affirming care significantly improved immediately and 3 months postintervention, as did transgender cultural competence, knowledge, and self-efficacy for providing trans-affirmative care (White Hughto et al., 2017). Several interventions to increase LGBTQ-affirmative competence among counseling students (Bidell, 2013; Rutter et al., 2008) and mental health providers (Pepping et al., 2018) also show preliminary promise for these interventions’ associations with increased competence and self-efficacy and reduced bias in small open pilot studies and evaluations of university courses (Bidell, 2013; Carlson et al., 2013; Luke & Goodrich, 2017; Pepping et al., 2018; Rutter et al., 2008). For example, two semester-long module-based trainings on LGB competency provided to counseling students have been associated with significantly higher LGB skills and knowledge compared with a time-matched control group (Rutter et al., 2008). Similarly, a one-day training in LGBTQ-affirmative therapy among practicing mental health providers was associated with significant changes in negative LGBTQ attitudes, knowledge, advocacy, and awareness (Pepping et al., 2018). Finally, a two-day training in LGBTQ-affirmative mental health care in Romania was associated with a significant increase in perceived LGBTQ-affirmative clinical skills and knowledge, practice attitudes, and comfort in addressing the mental health of LGBTQ individuals; explicit anti-LGBTQ attitudes significantly decreased (Lelutiu-Weinberger & Pachankis, 2017).

The present study sought to extend the existing literature in several ways. First, the impact of the few existing mental health provider training interventions has not been examined past the immediate postintervention period. Further, although there is a growing body of research suggesting the promise of trainings to increase LGBTQ-affirmative therapy, it is also essential to establish the relative efficacy of various delivery formats. Leveraging easily accessible technology to reach providers across diverse geographic locations and structurally stigmatizing contexts, including high-stigma countries and remote areas with scant resources, would encourage dissemination to populations most in need. Relatedly, a notable contribution would be to test whether such interventions can enhance provider competence and reduce bias under conditions of high anti-LGBTQ structural stigma that characterize most countries (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2019). Finally, also unknown is whether follow-up supervision can improve on initial training gains.

Following from the above, the current study tested the relative efficacy of an LGBTQ-affirmative mental health training program delivered in-person and online in reducing provider LGBTQ bias and improving LGBTQ competence. The training was delivered to mental health providers in Romania based on its high degree of structural stigma toward sexual and gender minority individuals (Bränström & Pachankis, 2021; Pachankis & Bränström, 2018). Although homosexuality was decriminalized in 2001 as part of Romania’s becoming a European Union (EU) state, a recent survey indicates that the majority of sexual and gender minority individuals in Romania are closeted due to past experienced and/or anticipated discrimination (Bränström & Pachankis, 2021; Pachankis & Bränström, 2018). Public negative attitudes toward LGBTQ individuals in Romania are perpetuated by a strong religious discourse maintaining that “traditional values” of family and gender are threatened by diverse sexual orientation and gender identities (Krishnamoorthy, 2016; Morgan, 2016; Mutler, 2019). LGBTQ-related victimization, with little to no legal repercussions, remains common (Monro et al., 2016), perpetuating a culture of fear and identity concealment, associated with stress, erosion of coping abilities, and consequent mental illness. Owing to a lack of structural protections (e.g., legal protections and rights), Romania ranks in the bottom quartile on the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) human rights index for sexual minorities in Europe (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2020).

The training was grounded in LGBTQ-affirmative therapy practice principles (Ritter & Terndrup, 2002) and advances in the application of minority stress theory to evidence-based mental health practice (Pachankis et al., 2015, 2020). Moreover, building on the initial success of an in-person pilot training (Lelutiu-Weinberger & Pachankis, 2017), this study sought to establish whether in-person and online delivery modalities differ significantly in their associations with key outcomes. This knowledge would help identify optimal and efficient routes for dissemination of LGBTQ-affirmative practice training across high-stigma locales, globally.

Method

Participants

Recruitment took place between September and October 2017 via advertisements sent to mental health and general health care organizations, local university psychology departments, and mental health professionals with interest in LGBTQ mental health (Lelutiu-Weinberger & Pachankis, 2017). Advertisements were distributed via web-postings, listservs, emails, and closed national professional Romanian Facebook groups.

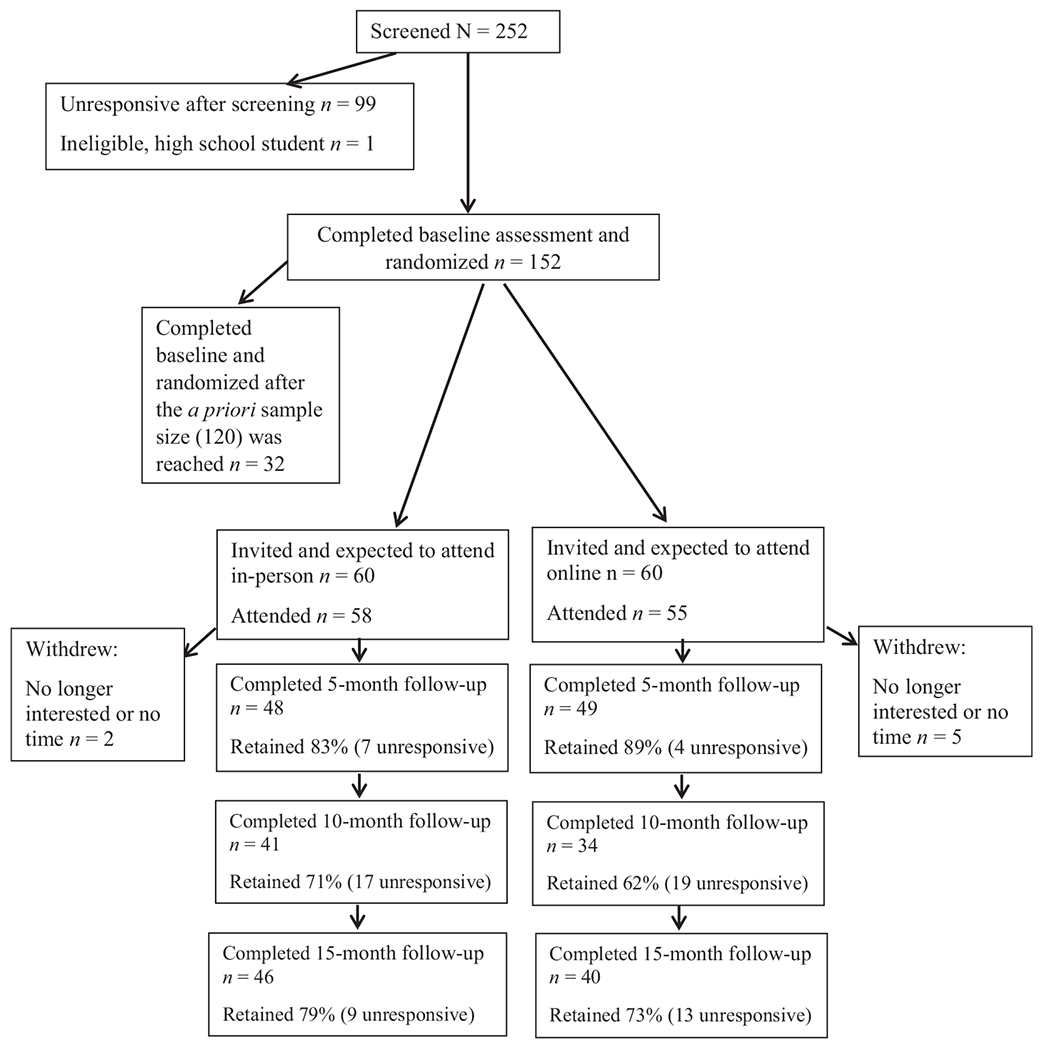

Figure 1 illustrates the number of participants who completed each part of the study, including those who were ineligible, withdrew, or declined to participate. The majority of participants identified as female (87.61%), practicing clinicians (63.71%), and heterosexual (84.95%). Their mean age was 35.09 (SD = 9.38; see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of Participants’ Progress Through Study Phases

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline

| In-Person Training (n = 58) |

Online Training (n = 55) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n [M] | % [SD] | n [M] | % [SD] | p Valuea |

| Age, y | [34.74] | [9.89] | [35.45] | [8.86] | 0.69 |

| Gender | 0.11 | ||||

| Female | 53 | 91.4 | 46 | 83.6 | |

| Male | 3 | 5.2 | 9 | 16.4 | |

| Transgender male | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gender nonbinary | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Current student | 0.44 | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 39.7 | 18 | 32.7 | |

| No | 35 | 60.3 | 37 | 67.3 | |

| Number of LGBTQ clients | 0.60 | ||||

| None | 44 | 75.9 | 42 | 76.4 | |

| 1 to 5 | 11 | 19.0 | 12 | 21.8 | |

| More than 5 | 3 | 5.2 | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Sexual orientation | 0.05 | ||||

| Heterosexual | 45 | 77.6 | 51 | 92.7 | |

| Gay, lesbian, or queer | 1 | 1.7 | 2 | 3.6 | |

| Bisexual | 7 | 12.1 | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Other or not sure | 5 | 8.6 | 1 | 1.8 | |

p value derived from t test for continuous, or chi-square test for categorical, variables.

Procedure

Screening

Potential participants took a five-minute online survey that gathered eligibility and contact information. Participants were asked to provide proof of their qualifications via e-mail and to complete an online consent form. All procedures were approved by and conducted in compliance with the Bioethics Commission of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases “Matei Balş.”

Experimental Design

On consent, participants received a link to the baseline survey. One hundred fifty-two individuals completed the survey and were randomized. Randomization occurred in a 1:1 manner to receive the training either in-person or online. Randomization was stratified based on place of residence (in or near Bucharest vs. elsewhere in the country). Given a priori sample size determinations, only the first 120 individuals who submitted verification of professional status after randomization were invited to the training. The remaining 32 individuals were placed on a waitlist. Because three randomized and invited participants confirmed that they could not attend the training, they were replaced with the first three individuals on the waitlist in their respective arm. This yielded a final sample size of 120 confirmed participants. Seven of 120 confirmed participants did not attend the training, yielding an analytic sample of 113. In-person trainees who needed to travel to Bucharest received travel stipends.

Training Intervention

Procedures

To expose both groups to the same information, the in-person training was live streamed to those randomized to the online condition, with technical support before and during the training. The online platform allowed video, audio, and text-based chat sharing. The training took place in English with live Romanian translation.

Facilitators

The first trainer was a U.S.-based clinical psychologist with clinical expertise with LGBTQ individuals and experience conceptualizing and conducting trainings in LGBTQ-affirmative mental health care. The second trainer was a Romanian social psychologist with 11 years of experience developing health-promotion interventions for LGBTQ populations. Two other trainers were licensed mental health providers who deliver LGBTQ-affirmative mental health care in Romania in independent practice and as part of two intervention studies.

Training Content

The training drew on the first trainer’s 12-year experience building and delivering LGBTQ-affirmative mental health provider trainings. He and the second trainer conducted local needs assessments with gay and bisexual Romanian men and two prior pilot studies in Romania which helped them tailor the content to the local context (e.g., normative structural stressors, discrimination, identity concealment). The training was comprised of three core components intended to impart information, motivation, and behavioral skills (Fisher et al., 2003) for LGBTQ-affirmative care, and included content that was generally consistent with that contained in previous trainings of mental health providers (Bidell, 2013; Pepping et al., 2018; Rutter et al., 2008).

The first training day introduced participants to LGBTQ-affirmative psychotherapy principles (Ritter & Terndrup, 2002) and focused on conceptualizations of minority sexual orientation and gender identity, identity formation and life course development, the impact of stigma and related stressors on mental health, and LGBTQ couples and families. Professional practice guidelines were reviewed (American Psychological Association, 2012).

The second training day reviewed the integration of minoritystress-informed LGBTQ-affirmative practice into cognitive–behavioral therapy and was informed by recent advances in evidence-based practice as applied to LGBTQ individuals (Pachankis et al., 2015; Pachankis et al., 2020; Pachankis & Safren, 2019). The training reviewed minority stress–informed CBT case conceptualization and associated principles (e.g., minority stress can drive avoidance patterns while forging resilience) and techniques (e.g., stigma consciousness raising, reducing minority stress cognitions, assertiveness training; Pachankis, 2015; Rodriguez-Seijas et al., 2019). These were further illustrated through roleplays and case discussions drawn from the trainers’ interventions and covered internalized homophobia, coming out, parental relationships, bisexuality, and sexual health.

Finally, after the first follow-up, all participants were invited to receive two-hour monthly supervision for 8 months to build continued motivation and enhance behavioral skills through real-world practice, led online by the training team. Supervision used real-life case examples drawn from the trainers’ clinical experiences. Trainees also shared current LGBTQ-focused cases for clinical consultation.

Measures

Measures assessed the intervention’s feasibility and acceptability, and the relative efficacy of the in-person and online delivery modalities. Participants completed assessments at baseline, and 5, 10, and 15 months later. Where possible, scales originally intended for sexual minorities or gay men only were modified to be applicable to practice with clients across the LGBTQ spectrum. The scales were translated from English to Romanian by one of the authors who is fluent in both Romanian and English. The translation was then cross-checked by the two Romanian trainers, who are also fluent in both languages and are practicing clinicians, therefore lending expert review during the translation to ensure that the concepts were interpretable and culturally meaningful. Thereafter, the scales were validated in the Romanian context in this study’s pilot, and they performed as expected (Lelutiu-Weinberger & Pachankis, 2017).

Demographics

Participants reported their age, sex at birth, sexual orientation, gender identity, clinician or student status, and number of LGBTQ clients ever treated.

Feasibility

Intervention feasibility was assessed as training and supervision attendance.

Acceptability

Training acceptability was assessed at the five-month follow-up with eight items created for this study (e.g., “How much did the course help you learn new knowledge?,” “How much did the training help you become prepared to treat LGBTQ individuals?,” “How much would you recommend participation in this program to other colleagues?”). Response options ranged from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating more positive training impact.

Outcome Measures

Explicit Bias

The Modern Homonegativity Scale (Morrison et al., 2009) consists of 11 items (α = .85, average across the four assessments), with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An example item is: “LGBTQ individuals should stop complaining about the way they are treated in society, and simply get on with their lives.”

Implicit Bias

Implicit bias against sexual minorities was measured using the Sexual Orientation Implicit Association test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 1998), a computer-based task in which individuals quickly categorize, as either sexual minority or heterosexual, and positive or negative, images representing same-sex and heterosexual couples, and positive and negative words. The IATgen utility in Qualtrics was used to calculate a D score (Carpenter et al., 2019; Greenwald et al., 2003). Higher scores indicate more implicit positive associations for heterosexual individuals relative to sexual minorities. This task was previously associated with exposure to LGBTQ people among medical students (Wittlin et al., 2019), and demonstrated weaker susceptibility to social desirability compared with self-report measures (Banse et al., 2001). The split-half reliability coefficient (Spearman-Brown correction) was .80 across the four assessments.

Perceived LGBTQ-Affirmative Clinical Skills

The skills subscale of the Sexual Orientation Provider Competency Scale (Bidell, 2005) consists of eight items (α = .86, average across the four assessments), with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An example item is: “I feel competent to assess the mental health needs of a person who is LGBTQ in a therapeutic setting.”

LGBTQ-Affirmative Practice Beliefs

Practice beliefs aligned with LGBTQ-affirmative psychotherapy were assessed with the respective subscale of the Gay Affirmative Practice Scale (Crisp, 2006), adapted to include the full spectrum of sexual minority and gender diversity (α = .93, average across the four assessments). Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An example item includes: “In their practice with LGBTQ clients, practitioners should support the diverse makeup of their families.”

LGBTQ-Affirmative Practice Behavior

Participants’ self-reported engagement in LGBTQ-affirmative psychotherapy was assessed with the respective 15-item subscale of the Gay Affirmative Practice Scale (Crisp, 2006), adapted to include the full spectrum of sexual minority and gender diversity (α = .98, average across the four assessments). Response options range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); an example item examples is: “I acknowledge to clients the impact of living in a homophobic/transphobic society.”

LGBTQ-Affirmative Practice Intentions

Participants reported their intentions to provide LGBTQ-affirmative care in response to a question created for this study: “How much do you intend to practice LGBTQ-affirmative care?” with response options ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much so).

Number of Clients

Participants reported their number of current LGBTQ clients.

Analysis

Feasibility and Acceptability

To examine feasibility, we calculated frequencies and percentages of participants attending the training and supervision. To examine acceptability, we calculated percentages of participants endorsing each of the acceptability questions and conducted t tests to compare differences in response across the two conditions.

Outcome Analyses

We calculated mean scores for each outcome of interest (see Measures). We determined that all continuous outcomes adhered to a Gaussian distribution. One outcome, number of LGBTQ clients, was a count measure and, therefore, all analyses of this outcome accounted for its Poisson distribution. To determine randomization effectiveness between the in-person training and online training conditions, we examined whether there were baseline demographic differences between conditions (see Table 1). Results suggested that there were marginally more women and nonheterosexually identified participants in the in-person condition as compared with the online condition; therefore, statistical analyses were adjusted for gender and sexual orientation. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 with statistical significance evaluated at p < .05.

In a first set of analyses, we conducted within-condition analyses to determine each condition’ s relative association with changes in outcomes over time. Mixed model regressions for repeated measures with maximum likelihood estimation assessed differences for each outcome between baseline and 5-month, 10-month, and 15-month follow-ups. For continuous outcomes, we used linear mixed models with an identity link and normal distribution; for number of LGBTQ clients, we used a generalized linear mixed model with a log link and Poisson distribution. We selected a compound symmetry covariance structure based on a priori model fit criteria (i.e., lowest Akaike information criteria [AIC]). For the two sets of within-group analyses, models adjusted for age, gender, sexual orientation, and student status to adjust for the potential confounding effect of these variables on measured outcomes. Effect sizes (d) for within-group analyses at each follow-up time-point were calculated by mean baseline minus follow-up change in the outcome divided by the pooled standard deviation (Morris, 2008).

In a second set of analyses, between-group analyses assessed the equivalence of the online versus in-person delivery modalities. We included all available data and used mixed model regressions for repeated measures to examine the Condition × Time interaction effect of attending the online (condition = 1) versus in-person (condition = 0) condition from baseline (time = 0) to 15-month follow-up (time = 1) for each outcome. Analyses were adjusted for gender and sexual orientation owing to baseline differences in these variables between conditions. Effect sizes for between-group analyses were calculated as 2t/√df.

In a third set of analyses, we assessed the moderating influence of supervision attendance on all outcomes in the entire sample regardless of intervention condition. To do so, we limited data to include baseline (time = 0) and 15-month follow-up (time = 1) assessments and ran mixed model regressions for repeated measures, including a Supervision (attended = 1) × Time interaction. The interaction coefficient delineated whether those participants who attended at least one supervision session over the course of the study demonstrated significantly improved outcomes at 15-month follow-up compared with those participants who did not attend supervision. Models assessing the moderating influence of supervision were adjusted for age, gender, sexual orientation, and student status.

Results

Feasibility

One hundred twenty individuals were invited to participate. Two participants randomized to the in-person group and five to the online group did not attend the training, yielding a final sample of 113 participants (see Figure 1). Fifty-eight in-person participants attended the first day and 54 attended the second; 55 online participants attended the first day and 52 attended the second, indicating nearequivalent participation in both groups and supporting the feasibility of both modalities. In total, 47 (42%) participants attended at least one supervision session over the course of the study. Of the 113 participants, 97 (86%), 75 (66%), and 86 (76%) were retained at the 5-, 10-, and 15-month follow-ups, respectively.

Acceptability

The majority (92%) of participants reported that the training was at least “quite informative.” Most (88%) reported that the training helped them “quite a lot” or “a lot” to learn new knowledge, whereas 87% reported that the training motivated them “quite a lot” or “a lot” in making changes in their interactions with LGBTQ individuals and helped them gain more knowledge of LGBTQ individuals. Most (84%) reported that the training helped them prepare “quite a lot” or “a lot” to treat LGBTQ persons. There were no differences by arm for any acceptability indicators. At the 15-month follow-up, 90% of participants indicated that they had discussed this training with colleagues and 98% indicated that they would recommend participation to others. Last, 89% of supervision attendees wished that it could continue.

Intervention Outcomes

Changes Over Time in Outcomes of Interest (Within-Group)

In-Person Training.

We found significant reductions at each time point compared with baseline in explicit bias (average d across follow-up assessments = .41; see Table 2). Implicit bias was significantly reduced at 15-month follow-up compared with baseline (d = .25) but not at other follow-ups. Analyses also demonstrate increases in LGBTQ-affirmative clinical skills (average d = 1.06), beliefs (average d = .46), and behaviors (average d = .47) from baseline to follow-ups. LGBTQ-affirmative practice intentions and number of LGBTQ clients did not change.

Table 2.

LGBT-Affirmative Care Outcomes Over Time in In-Person (n = 58) and Online (n = 55) Training Modalities Groups

| Outcomes | Within-Group Comparisonsa |

Condition × Time Between-Group Comparisonb |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

5 Months |

10 Months |

15 Months |

Est. | [95% CI] | d | ||||||||

| M | SE | M | SE | d | M | SE | d | M | SE | d | ||||

| Explicit LGBTQ bias | −0.01 | [−0.21, 0.20] | 0.01 | |||||||||||

| In-person training (in-person) | 2.43 | 0.08 | 2.12 ** | 0.08 | 0.40 | 2.14 ** | 0.10 | 0.49 | 2.22 ** | 0.10 | 0.35 | |||

| Mobile training (online) | 2.60 | 0.08 | 2.48 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 2.38 * | 0.11 | 0.36 | 2.39 * | 0.12 | 0.31 | |||

| Implicit LGBTQ bias | −0.11 | [−0.32, 0.10] | 0.15 | |||||||||||

| In-person training (in-person) | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.15 † | 0.07 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.18 * | 0.07 | 0.25 | |||

| Mobile training (online) | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.22 † | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.12 ** | 0.07 | 0.64 | |||

| LGBTQ-affirmative practice clinical skills | 0.16 | [−0.14, 0.46] | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| In-person training (in-person) | 2.59 | 0.11 | 3.36 *** | 0.10 | 0.97 | 3.45 *** | 0.11 | 1.09 | 3.60 *** | 0.14 | 1.12 | |||

| Mobile training (online) | 2.42 | 0.11 | 3.13 *** | 0.10 | 0.97 | 3.28 *** | 0.13 | 1.11 | 3.53 *** | 0.12 | 1.45 | |||

| LGBTQ-affirmative practice beliefs | −0.02 | [−0.21, 0.17] | 0.03 | |||||||||||

| In-person training (in-person) | 4.27 | 0.07 | 4.45 * | 0.07 | 0.36 | 4.59 *** | 0.07 | 0.64 | 4.47 * | 0.08 | 0.38 | |||

| Mobile training (online) | 4.27 | 0.07 | 4.42 * | 0.07 | 0.31 | 4.53 ** | 0.08 | 0.54 | 4.43 * | 0.08 | 0.31 | |||

| LGBTQ-affirmative practice behaviors | 0.21 | [−0.54, 0.96] | 0.07 | |||||||||||

| In-person training (in-person) | 2.81 | 0.23 | 3.68 *** | 0.29 | 0.45 | 3.66 * | 0.34 | 0.43 | 3.86 *** | 0.31 | 0.54 | |||

| Mobile training (online) | 2.62 | 0.23 | 3.21 * | 0.31 | 0.32 | 3.40 * | 0.35 | 0.42 | 3.72 *** | 0.32 | 0.59 | |||

| LGBTQ-affirmative practice intentions | 0.17 | [−0.19, 0.52] | 0.12 | |||||||||||

| In-person training (in-person) | 4.00 | 0.11 | 4.04 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 3.93 | 0.15 | −0.08 | 3.87 | 0.15 | −0.14 | |||

| Mobile training (online) | 3.73 | 0.10 | 3.67 | 0.12 | −0.08 | 3.82 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 3.78 | 0.11 | 0.07 | |||

| Number of LGBTQ clientsc | −0.35 | [−1.13, 0.44] | 0.17 | |||||||||||

| In-person training (in-person) | 1.47 | 0.63 | 1.35 | 0.63 | −0.02 | 2.30 | 1.51 | 0.10 | 2.19 | 1.15 | 0.10 | |||

| Mobile training (online) | 0.75 | 0.22 | 0.32 ** | 0.10 | −0.34 | 0.40 | 0.11 | −0.27 | 0.81 | 0.22 | 0.04 | |||

Note. Effect sizes for within-group comparisons calculated by dividing the baseline minus follow-up mean difference by pooled standard deviation at each follow-up time point. Effect sizes for Condition × Time between-group comparisons calculated by 2t/√df.

Differences between baseline and each follow-up time within-group were assessed using linear mixed model regressions for repeated measures adjusted for age, gender (female vs. male, transgender male, or gender nonbinary), sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, or other), and student status (yes vs no).

Linear mixed effects model assessed treatment effect of online versus in-person by Condition × Time comparison from baseline to 15-month follow-up controlling for sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, or other).

Count outcome used generalized linear mixed model with a log link and Poisson distribution.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Online Training.

We found significant reductions in explicit bias at 10-month (d = .36) and 15-month (d = .31) follow-ups compared with baseline (see Table 2). Implicit bias was significantly reduced at 15-month follow-up compared with baseline (d = .64), but not compared with other follow-ups. Participants showed significant increases across follow-ups in LGBTQ-affirmative clinical skills (average d = 1.18), beliefs (average d = .39), and behaviors (average d = .44) from baseline to follow-ups. LGBTQ-affirmative practice intentions did not change. Participants reported significantly fewer LGBTQ clients at five-month follow-up compared with baseline (d=−.34), but no significant differences from baseline to other follow-up periods.

Comparisons of In-Person and Online Training (Between-Group)

When examining changes from baseline to 15-month follow-up across arms, we found no significant Condition × Time interactions (average d = .04) suggesting the relative equivalence of associations between receiving online and in-person training and study outcomes.

Supervision

In moderation analyses comparing changes in outcomes from baseline to 15-month follow-up between those participants who did and did not attend at least one supervision session, we found significant Time × Supervision interactions for explicit bias (β = −.26, p < .05) and LGBTQ-affirmative practice behaviors (β = .97, p < .05) and a marginal effect for LGBTQ-affirmative practice intentions (β = .33, p < .10; see Table 3). We did not find significant Time × Supervision interactions for implicit bias, LGBTQ-affirmative practice skills or beliefs, or number of LGBTQ clients. These results suggest that participants who attended at least one supervision session over the course of the study demonstrated greater reductions in explicit bias and increases in LGBTQ-affirmative behaviors from baseline to 15-month follow-up compared with participants who did not attend supervision.

Table 3.

LGBTQ-Affirmative Care Outcomes From Baseline to 15-Month Follow-Up Moderated by Supervision Attendance At (n = 113)

| Outcomes | Explicit LGBTQ Bias |

Implicit LGB Bias |

LGBTQ-Affirmative Practice Clinical Skills |

LGBTQ-Affirmative Practice Beliefs |

LGBTQ-Affirmative Practice Behaviors |

LGB TQ-Affirmative Practice Intentions |

N of LGBTQ Clientsa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | [95% CI] | Est | [95% CI] | Est | [95% CI] | Est | [95% CI] | Est | [95% CI] | Est | [95% CI] | Est | [95% CI] | |

| Assessment | ||||||||||||||

| 15 months | −0.08 | [−0.25, 0.08] | −0.15 * | [−0.29, −0.01] | 0.90 *** | [0.64, 1.15] | 0.13 † | [−0.01, 0.27] | 0.05 † | [−0.02, 1.12] | −0.22 † | [−0.45, 0.01] | 0.22 | [−0.23, 0.67] |

| Baseline | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Attended supervision at least once | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.07 | [−0.17, 0.30] | 0.04 | [−0.13, 0.21] | 0.13 | [−0.16, 0.43] | 0.17 † | [−0.02, 0.37] | −0.36 | [−1.04, 0.31] | 0.01 | [−0.30, 0.32] | 1.16 † | [−0.07, 2.05] |

| No | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Assessment × Supervision | −0.26 * | [−0.50, −0.02] | −0.10 | [−0.31, 0.11] | 0.31 | [−0.07, 0.68] | 0.06 | [−0.15, 0.27] | 0.97 * | [0.14, 1.80] | 0.33 † | [−0.01, 0.67] | 0.11 | [−0.66, 0.89] |

Note. Models were adjusted for age, gender (female vs. male, transgender male, or gender nonbinary), sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, or other), and student status (yes vs. no).

Count outcome used generalized linear mixed model with a log link and Poisson distribution.

p <. 10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p <.001.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that a brief training intervention for mental health providers was feasible, acceptable, and associated with durable improvements in LGBTQ-affirmative practice competence and reduced bias. The fact that both in-person and online training modalities were equivalently associated with reduced bias and increases in LGBTQ-affirmative clinical skills, beliefs, and behaviors supports the future use of online modalities to train mental health providers, removing geographic location barriers (see Figure 2). That the training was implemented in a high-stigma setting, namely Romania, offers a promising approach for similar global settings lacking in LGBTQ-affirmative mental health support. Overall, results of this study join with others (Bidell, 2013; Carlson et al., 2013; Luke & Goodrich, 2017; Pepping et al., 2018; Rutter et al., 2008) to suggest that training mental health providers in LGBTQ-affirmative treatment approaches offers a viable solution for reducing provider stigma, an established barrier to effective mental health care for LGBTQ individuals (Ferlatte et al., 2019; Shipherd et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

Changes in Primary Outcomes Over Time by Condition

These findings extend previous research on LGBTQ-affirmative provider trainings in several ways. First, most studies of LGBTQ-affirmative training have focused on medical providers. However, given the significant mental health disparities among LGBTQ populations worldwide, especially in high-stigma locales (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2019), effective trainings in LGBTQ-affirmative mental health care are warranted. Although a growing body of research indicates the associations of such trainings with improved provider knowledge and skills, our study has included one of the largest samples to date, consisting of both mental health providers and trainees, strengthening the generalizability of knowledge regarding such trainings across participant types. Second, this study shows associations between training participation and reductions in both explicit and implicit bias. Although not previously used in studies of LGBTQ-affirmative trainings, measures of implicit bias are less vulnerable to social desirability, thereby strengthening the validity of the present study’s results. Third, the fact that we found support for sustained change in several outcomes across 15 months provides evidence of a potentially persistent impact of brief trainings. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to examine the effects of an LGBTQ competency and bias reduction mental health training intervention. Fourth, this study provides support for the relative comparability of in-person and online training modalities, advancing previous research on in-person delivery modalities (Bidell, 2013; Carlson et al., 2013; Lelutiu-Weinberger & Pachankis, 2017; Luke & Goodrich, 2017; Pepping et al., 2018; Rutter et al., 2008; White Hughto et al., 2017). This finding points to the advantage afforded by the effective online training modality, which may allow for scaled-up trainings that can reach large numbers of mental health providers across diverse geographic (e.g., rural) and sociopolitical (e.g., structurally stigmatizing) contexts. Finally, findings regarding the added benefit of supervision suggest its utility in sustaining initial training gains.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations are noted. First, the lack of a nonactive control group limits potential for causal conclusions. The present design does not rule out certain threats to validity (e.g., naturally occurring attitudinal changes) and thereby limits attributing improvements in outcomes solely to the training itself. Second, the study only measured provider-level outcomes. Future research should include client mental health and treatment experience to further validate the effectiveness of this LGBTQ-affirmative training. Third, this research attracted self-selected mental health providers motivated to support LGBTQ clients. We deemed motivation to acquire LGBTQ-affirmative therapeutic skills as an important aspect in this proof-of-concept research, especially as one of the questions of the present study was related to the feasibility of engaging mental health professionals working in a context where LGBTQ individuals are highly stigmatized. However, engaging less motivated providers with higher LGBTQ-bias is an important next step, which may be facilitated by collaborations with governmental agencies (e.g., ministries of health, national psychological associations). Fourth, our measure of LGBTQ-affirmative practice intentions entailed a single item, potentially explaining the lack of change for this outcome. Fifth, the implicit measure of bias used in this study only assessed bias toward sexual minorities; an implicit measure of bias toward gender minorities is needed. Finally, the sample was 88% female-identified, which may limit potential for generalizability to other genders. However, this largely reflects the fact that in the recent years, more than 70% of doctoral students in psychology and early career psychologists have been female (Willyard, 2011). Previous studies testing the impact of LGBTQ-affirmative training report similarly high proportions of female trainees (Pepping et al., 2018; Rutter et al., 2008). The gender distribution of our sample therefore reflects the gender distribution of the field and potentially enhances generalizability of findings to mental health practitioners and trainees.

Future implementation research can determine adaptations necessary for this intervention to address the needs of diverse practice contexts. Future research might also examine the mechanisms through which this treatment exerts its impact. Consistent with theories of behavior change (Fisher et al., 2003), knowing whether and which training components are primarily responsible for change is key to efficient interventions.

Conclusion

Mental health providers can propagate societal change given their influential positions. Providers trained in LGBTQ-affirmative practice can advocate for reductions in structural stigma within society and their profession, while at the same time serving as a buffer between structural stigma and their clients through affirmative treatment. The fact that a brief training was associated with sustained improvements in LGBTQ-affirmative competence demonstrates that such interventions occupy a central role in supporting mental health providers in fully harnessing their role in effecting both structural and individual change.

Public Significance Statement.

This study provides initial evidence that LGBTQ-affirmative mental health trainings can improve providers’ LGBTQ competence and reduce their bias, with sustained effects across time. The fact that online training showed similar effects as in-person training paves the way for efficient dissemination of such training, including in high-stigma global contexts.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (R21MH113673; PI: Lelutiu-Weinberger) and the Yale Fund for LGBTQ Studies. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Florentina Lăscut, Monica Manu, Jillian Scheer, and Dr. Craig Rodriguez-Seijas, who contributed expertise during training and supervision; Dr. Monica Dumbrava-Călugaru, Domniţa Damian, and Luiza Mocanu for facilitating training logistics; Hyperion University for hosting the training; the Romanian Association Against AIDS for disseminating the training opportunity; and T.J. Sullivan for data management consultation. We also thank all study participants.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. The American Psychologist, 67(1), 10–42. 10.1037/a0024659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banse R, Seise J, & Zerbes N (2001). Implicit attitudes towards homosexuality: Reliability, validity, and controllability of the IAT. Zeitschrift Für Experimentelle Psychologie, 48(2), 145–160. 10.1026/0949-3946.48.2.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidell MP (2005). The Sexual Orientation Counselor Competency Scale: Assessing attitudes, skills, and knowledge of counselors working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44(4), 267–279. 10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb01755.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bidell MP (2013). Addressing disparities: The impact of a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender graduate counselling course. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, 13(4), 300–307. 10.1080/14733145.2012.741139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bränström R, & Pachankis JE (2021). Country-level structural stigma, identity concealment, and day-to-day discrimination as determinants of transgender people’s life satisfaction. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(9), 1537–1545. 10.1007/s00127-021-02036-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Krakower DS, Underhill K, Vincent W, Magnus M, Hansen NB, Kershaw TS, Mayer KH, Betancourt JR, & Dovidio JF (2018). A closer look at racism and heterosexism in medical students’ clinical decision-making related to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Implications for PrEP education. AIDS and Behavior, 22(4), 1122–1138. 10.1007/s10461-017-1979-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson TS, McGeorge CR, & Toomey RB (2013). Establishing the validity of the affirmative training inventory: Assessing the relationship between lesbian, gay, and bisexual affirmative training and students’ clinical competence. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 39(2), 209–222. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter TP, Pogacar R, Pullig C, Kouril M, Aguilar S, LaBouff J, Isenberg N, & Chakroff A (2019). Survey-software implicit association tests: A methodological and empirical analysis. Behavior Research Methods, 51(5), 2194–2208. 10.3758/s13428-019-01293-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp C (2006). The Gay Affirmative Practice Scale (GAP): A new measure for assessing cultural competence with gay and lesbian clients. Social Work, 51(2), 115–126. 10.1093/sw/5L2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlatte O, Salway T, Rice S, Oliffe JL, Rich AJ, Knight R, Morgan J, & Ogrodniczuk JS (2019). Perceived barriers to mental health services among Canadian sexual and gender minorities with depression and at risk of suicide. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(8), 1313–1321. 10.1007/s10597-019-00445-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincher C, Williams JE, MacLean V, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, & Canto J (2004). Racial disparities in coronary heart disease: A sociological view of the medical literature on physician bias. Ethnicity & Disease, 14(3), 360–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Fisher J, & Harman J (2003). The information–motivation–behavioral skills model: A general social psychological approach to understanding and promoting health behavior. In Wallston JSKA (Ed.), Social psychological foundations of health and illness (pp. 82–106). Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. 10.1002/9780470753552.ch4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foglia MB, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2014). Health disparities among LGBT older adults and the role of nonconscious bias. The Hastings Center Report, 44(s4), S40–S44. 10.1002/hast.369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, & Schwartz JL (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, & Banaji MR (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2016). Structural stigma: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. The American Psychologist, 71(8), 742–751. 10.1037/amp0000068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association. (2019). State-sponsored homophobia. https://ilga.org/downloads/ILGA_State_Sponsored_Homophobia_2019.pdf

- International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association. (2020). Rainbow Europe package. Annual review and rainbow Europe map. https://www.ilga-europe.org/rainboweurope/2020

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, & Anafi M (2016, December). Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kecojevic A, Wong CF, Schrager SM, Silva K, Bloom JJ, Iverson E, & Lankenau SE (2012). Initiation into prescription drug misuse: Differences between lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) and heterosexual high-risk young adults in Los Angeles and New York. Addictive Behaviors, 37(11), 1289–1293. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy N (2016). Romanian activists call for ban on same-sex marriages in the country. International Business Times. http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/romanian-activists-call-ban-same-sex-marriages-country-1561657

- Lelutiu-Weinberger C, & Pachankis JE (2017). Acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-affirmative mental health practice training in a highly stigmatizing national context. LGBT Health, 4(5), 360–370. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pollard-Thomas P, Pagano W, Levitt N, Lopez EI, Golub SA, & Radix AE (2016). Implementation and evaluation of a pilot training to improve transgender competency among medical staff in an urban clinic. Transgender Health, 1(1), 45–53. 10.1089/trgh.2015.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C-C, Matthews AK, Aranda F, Patel C, & Patel M (2015). Predictors and consequences of negative patient-provider interactions among a sample of African American sexual minority women. LGBT Health, 2(2), 140–146. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke M, & Goodrich KM (2017). Assessing an LGBTQ responsive training intervention for school counselor trainees. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 3(2), 103–119. 10.1080/23727810.2017.1313629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, & Cochran SD (2001). Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91(11), 1869–1876. 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, & Frost DM (2008). Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 368–379. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monro S, Christmann K, Gibbs GR, & Monchuk L (2016). Professionally speaking: Challenges to achieving equality for LGBT people. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/31334/1/FRA-2016-LGBT-public-officials.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Moore KL, Lopez L, Camacho D, & Munson MR (2020). A qualitative investigation of engagement in mental health services among Black and Hispanic LGB young adults. Psychiatric Services, 71(6), 555–561. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J (2016). Three million people want to ban same-sex marriage in Romania. Gay Star News. http://www.gaystarnews.com/article/three-million-people-want-ban-sex-marriage-romania/#gs._EsgV2U

- Morris SB (2008). Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 364–386. 10.1177/1094428106291059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MA, Morrison TG, & Franklin R (2009). Modern and old-fashioned homonegativity among samples of Canadian and American university students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(4), 523–542. 10.1177/0022022109335053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mutler A (2019). Same-sex couples in Romania face hostility as they challenge discrimination. RadioFreeEurope. RadioLiberty. Romania. https://www.rferl.org/a/same-sex-couples-in-romania-face-hostility-as-they-challenge-discrimination/30057755.html

- Pachankis JE (2015). A transdiagnostic minority stress treatment approach for gay and bisexual men’s syndemic health conditions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7), 1843–1860. 10.1007/s10508-015-0480-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, & Bränström R (2018). Hidden from happiness: Structural stigma, concealment, and life satisfaction among sexual minorities across 28 countries. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(5), 403–415. 10.1037/ccp0000299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, & Safren SA (2019). Handbook of evidence-based mental health practice with sexual and gender minorities. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/med-psych/9780190669300.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina HJ, Safren SA, & Parsons JT (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875–889. 10.1037/ccp0000037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, McConocha EM, Clark KA, Wang K, Behari K, Fetzner BK, Brisbin CD, Scheer JR, & Lehavot K (2020). A transdiagnostic minority stress intervention for gender diverse sexual minority women’s depression, anxiety, and unhealthy alcohol use: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(7), 613–630. 10.1037/ccp0000508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepping CA, Lyons A, & Morris EMJ (2018). Affirmative LGBT psychotherapy: Outcomes of a therapist training protocol. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, & Practice, 55(1), 52–62. 10.1037/pst0000149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat TC, Malik M, & Beyrer C (2018). Epidemiology of HIV, sexually transmitted infections, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis among incarcerated transgender people: A case of limited data. Epidemiologic Reviews, 40(1), 27–39. 10.1093/epirev/mxx012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter K, & Terndrup AI (2002). Handbook of affirmative psychotherapy with lesbians and gay men. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Seijas C, Burton CL, Adeyinka O, & Pachankis JE (2019). On the quantitative study of multiple marginalization: Paradox and potential solution. Stigma and Health, 4(4), 495–502. 10.1037/sah0000166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter PA, Estrada D, Ferguson LK, & Diggs GA (2008). Sexual orientation and counselor competency: The impact of training on enhancing awareness, knowledge and skills. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 2(2), 109–125. 10.1080/15538600802125472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shipherd JC, Green KE, & Abramovitz S (2010). Transgender clients: Identifying and minimizing barriers to mental health treatment. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 14(2), 94–108. 10.1080/19359701003622875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, Keck PE, Arnold LM, Collins J, Wilson RM, Fleck DE, Corey KB, Amicone J, & Adebimpe VR (2003). Ethnicity and diagnosis in patients with affective disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64(7), 747–754. 10.4088/JCP.v64n0702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn M, & Fu SS (2003). Paved with good intentions: Do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? American Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 248–255. 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, Herrin J, Burke SE, Nelson DB, Perry W, Yeazel M, & Przedworski JM (2015). Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: A medical student CHANGES study report. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(12), 1748–1756. 10.1007/s11606-015-3447-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman A, & Chaimowitz G (2014). Mental health care for people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and (or) queer. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(11), 1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Clark KA, Altice FL, Reisner SL, Kershaw TS, & Pachankis JE (2017). Improving correctional healthcare providers’ ability to care for transgender patients: Development and evaluation of a theory-driven cultural and clinical competence intervention. Social Science & Medicine, 195, 159–169. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willyard C (2011). Men: A growing minority. GradPSYCH Magazine, 9(1), 40. [Google Scholar]

- Wilton L, Chiasson MA, Nandi V, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Frye V, Hirshfield S, & Koblin B (2018). Characteristics and correlates of lifetime suicidal thoughts and attempts among young black men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(3), 273–290. 10.1177/0095798418771819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wittlin NM, Dovidio JF, Burke SE, Przedworski JM, Herrin J, Dyrbye L, Onyeador IN, Phelan SM, & van Ryn M (2019). Contact and role modeling predict bias against lesbian and gay individuals among early-career physicians: A longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 238, 112422. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]