Abstract

Remote monitoring and artificial intelligence will become common and intertwined in anesthesiology by 2050.

In the intraoperative period, technology will lead to the development of integrated monitoring systems that will integrate multiple data streams and allow anesthesiologists to track patients more effectively. This will free up anesthesiologists to focus on more complex tasks, such as managing risk and making value-based decisions. This will also enable the continued integration of remote monitoring and control towers having profound effects on coverage and practice models..

In the PACU and ICU, the technology will lead to the development of early warning systems that can identify patients who are at risk of complications, enabling early interventions and more proactive care. The integration of augmented reality will allow for better integration of diverse types of data and better decision making.

Postoperatively, the proliferation of wearable devices that can monitor patient vital signs and track their progress will allow patients to be discharged from the hospital sooner and receive care at home. This will require increased use of telemedicine, which will allow patients to consult with doctors remotely.

All of these advances will require changes to legal and regulatory frameworks that will enable new workflows that are different than those familiar to today’s providers.

Introduction

“The vast possibilities of our great future will become realities only if we make ourselves responsible for that future”

Gifford Pinchot

Accurately predicting what the practice of anesthesiology will be like 30 years in the future is an exceedingly difficult and a complex undertaking. The rate of growth of technology and medical knowledge continues to accelerate, opening new avenues for therapeutics and synergistic applications of novel technologies. Combined with an ever-changing popular opinion, a dynamic regulatory landscape, and unknown unknowns like a pandemic, the waters are further muddied. In this article, we will attempt to create a window into how the interface between technology and providers might shape our practice 30 years from now, with a particular focus on monitoring. While these predictions will likely be inaccurate the purpose of this article is not for use as a time-capsule; rather, the purpose is to excite and inspire readers to take part in creating that future. We will begin with how technologies such as machine learning, artificial intelligence, and robotics might change and augment our intraoperative environment. We will then transition to analyze how they might impact care environments such as the PACU or ICU, followed by a discussion of the potential effects in the post-operative period, including wearable technologies and home monitoring. Finally, we will examine some of the legal and regulatory hurdles that may be encountered, including staffing challenges and other workforce implications.

The Intraoperative Period

Historical Context and Current State

The current workflow in anesthesiology – a preoperative evaluation, intraoperative 1:1 monitoring and care from an anesthesia provider (anesthesiologist or CRNA), and postoperative handoff to the PACU, dates to the 1940s after World War II. That is when the modern specialty of anesthesiology developed distinct from surgery. In the intervening 75 years the types of monitors and drugs have changed, but the underlying paradigm of 1:1 intraoperative care has not. The 1960s and 70s saw the introduction of non-invasive blood pressure and PA catheters, the 1980 pulse-oximetry, 1990s propofol, the 2000s ultrasound and TEE become more widespread, etc. While all of these advances improved the patient care and associated outcomes, the fundamental idea of one anesthesia provider for one patient remained constant. The next 25 years may not be as stable.

The Operating Room: Integrated monitoring, automated processes and control towers

In today’s operating room, the myriad of monitors exist as separate streams of data. In the future these will be integrated feeds into complex models and will not only enhance the human ability to do technical and cognitive tasks faster but also power closed-loop systems capable of practicing anesthesiology more safely and efficiently than a human could alone (See Figure 1). Today, the anesthesiologist’s analytical and decision-making abilities are challenged by increasingly vast amounts of intraoperative data collected during a single surgery.1 With the recognition that information overload contributes to perioperative complications,1,2 machine learning (ML) models already exist that can assimilate superhuman quantities of intraoperative data to identify critical events and notify anesthesiologists.3 Beyond synthesizing data to identify evolving critical events, existing systems like Edwards’ Hypotension Prediction Index show that ML-driven technologies can be used to predict intraoperative hypotension before it even occurs.4–7

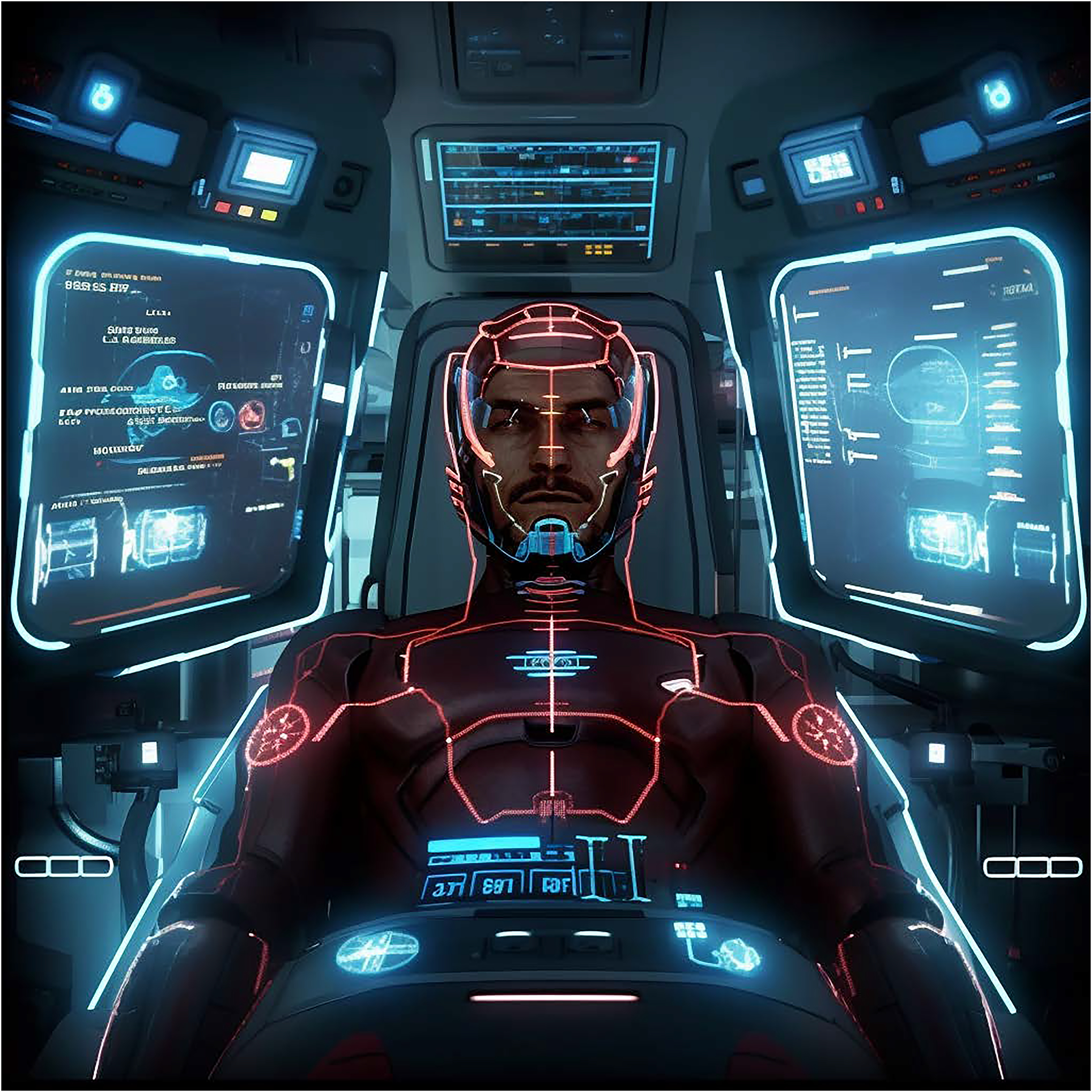

Figure 1:

Based on prompts to Midjourney, the digital operating room of the future with integrated data streams

While the complete closed-loop anesthesia system Sedasys was ultimately retired, the concept of an automated system for assessing and intervening on a patient’s depth of anesthesia lives on for future development.8,9 In many advanced technologies, the first attempt is often unsuccessful. Indeed, electric vehicles were conceptualized in the early 1900’s, and attempts made at commercialization during the 1970’s oil embargo and again in the 1990’s following the Clean Air and Energy Policy Acts. But only recently have these vehicles seen more widespread adoption. The future will likely come in incremental steps. For example, one recently deployed AI system focuses on the endoscopy images and provides cues which led to improved efficiencies for anesthesiologists in terms of timing emergence and gauging necessary depth of anesthesia.10 As a next step such a system could prompt the anesthesiologist to decrease anesthetic depth, and then future iterations could decrease the depth without anesthesiologist prompting. Similarly, modern closed loop hemodynamic systems automatically adjust vasopressor infusions to maintain a MAP within a certain target range. Separately, machine learning models can be developed to determine the “optimal” blood pressure target for a given patient to prevent acute kidney injury or myocardial injury. It does not take much foresight to see a world where the latter algorithm to set the target for the closed loop system.

Future iterations of systems based on artificial intelligence will not replace the anesthesiologist, but rather free them to focus on more cognitively intense tasks. For example, an algorithm that predicts a higher likelihood of intraoperative cardiac arrest would not intervene independently, but rather alert the anesthesiologist to decide whether to proceed with surgery. If that surgery does proceed, the complexity of the decision making (e.g., types of invasive monitors, optimal selection and changing of ionotropic and other drugs) would be beyond the task-oriented algorithms of a computer and require constant input and adjustment by the anesthesiologist. Despite this active involvement, some aspects of care may be automated, for instance the current use of target-controlled infusions that already automate maintenance propofol dosing may be extended to micro-titration of other medications like vasopressors or analgesics.11 What will also be augmented by several integrated machines, is much of the in-person patient management and workload management.

The automation of process oriented tasks, does not eliminate the need for an anesthesiologist, it just changes their role. Machines may be able to quantify risk, but they are unable to make value-based decisions that require tradeoffs (i.e., lack the “art” of medicine potential). Thus, the question of what constitutes an unacceptably high risk of intraoperative cardiac arrest, for example, will ultimately be deferred to a human anesthesiologist. Preoperatively, this means an enhanced role for the anesthesiologist in having goal setting conversations with patients, explaining risks and understanding the patient’s goals of care. Intraoperatively, minor procedures may not require an anesthesiologist in the room 100% of the time, but rather allow for supervision of some portions of the case in a nearby “control tower”, making decisions about the flow of patients from operating rooms to various post-operative destinations and ensuring the patient remains stable. The anesthesia control tower model is already being implemented and heavily studied regarding it’s potential to improve outcomes by leveraging ML to assess risk, diagnose negative patient trajectories, and implement evidence-based practice.12–14 Overall, novel technologies will automate parts of current practice such that anesthesiologists can focus less on mundane tasks and more on critical decision-making and truly human patient interactions (e.g., allaying anxiety and explaining the anesthetic).

A requirement for any of these changes are modifications to current regulatory and billing requirements. For example, currently providers cannot bill for remote anesthesia monitoring, so if that does not change, a provider will always need to be in the room. Similarly, if an AI algorithm makes a mistake who is liable the anesthesiologist, or the device maker? These questions will need to be addressed in order to allow for change to occur. A catalyst for these changes, may be the projected workforce shortages that make it harder to cover all procedures with a provider in the room at all times.

The Postoperative Period

Historical Context and Current State

The concept of a recovery room adjacent to an operating theatre predates the practice of anesthesia, with reports describing such rooms in the early 19th century.15 Accompanying the introduction of ether as an anesthetic agent was a recovery room where patients would regain consciousness and body warmth.16 During World War II, nursing shortages in the United States catalyzed a dramatic increase in the number of recovery areas. In 1947, JAMA’s publication of the Anesthesia Study Commission cemented the role of post-anesthesia care, stating that, “the need for postoperative observation rooms under trained personnel and under the direction of anesthesia service was obvious” based on its role in reducing preventable deaths.17

The PACU and hospital stay: Early warning systems and augmented reality

Improvements in intraoperative anesthetic and analgesic agents and techniques will surely play a role in improving postoperative recovery, but respiratory, cardiac and neurologic outcomes will remain top priorities. Specific attention to concepts such as the team-focused failure-to-rescue (FTR),18 and patient-centric concepts like myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MINS),19 along with emerging concerns such as perioperative brain health20 and postoperative opioid use disorders will all be high-value targets for PACU physicians. A likely hard-fought cultural evolution towards acceptance of assistive algorithms will prove as essential as technological evolution, which is inevitable for the period after surgery as it is during surgery.

Medical early warning systems (MEWS) have been available and studied for some time and will represent the foundation of future PACU care, albeit with incredibly improved accuracy and complexity. In general, these systems help practitioners recognize early signs of patient decompensation.21 In the decades to come, MEWS will emerge as ubiquitous tools for augmented postoperative care.22 The MEWS of the future will incorporate preoperative predictive analytical models23 as well as classical patient and surgical variables, and will rest upon an AI/ML framework to accomplish the goals of improved care and safety,22,24 iterating patients’ propensity for risk in real time.25

ML systems have been shown to improve and personalize existing warning systems,26 with a strength in predicting outcomes such as acute kidney injury, sepsis, DVT, ICU admissions, wound, neurologic and cardiopulmonary complications.27–31 In addition, risk of future opioid dependence, readmission and long term function will be a major outcomes requiring predictive measures. Moreover, the MEWS of the future will integrate new and unexpected data sources such as rich intraoperative32,33 and continuous telemetry and biosensor data and/or cognitive measures (e.g., EEG), racial/ethnic and socioeconomic determinants of health, along with surgical data from robotic surgical and/or OR video-recording platforms.34–37 (See Figure 2)

Figure 2:

Based on prompts to Midjourney, the PACU of the future with integrated data and augmented reality

Our current approach to postoperative monitoring is essentially no different than it was decades ago, as described previously. Although some of the data points may have changed and the medical team approach has improved (e.g., with rapid response teams), technology will play a role in modernizing the capabilities of PACU providers and moving towards more integrated, “systems anesthesiology” approaches to patient care.38 An especially forward-looking integration of all of this data will include augmented reality (AR)39 (an integration of synthetic content with the real world), mixed reality (AR but with the ability to manipulate the synthetic data) and/or remote automated monitoring systems (a subset of telemedicine)40 in the recovery room. Head-mounted displays, for example, could show live-streaming risk scores for each patient, bed management and throughput data, computer vision-assisted interpretation of ultrasound images and widely available biomarker assays that guide prediction and management of an array of outcomes.41–43 This sort of interface will guide patient optimization in real-time with an intense focus on event prediction and the detection of early signs of deterioration.24

Palla et al. showed that the prediction of PACU hypotension was improved when anesthesiologists trusted and used an ML model.32 One ML tool, called “Prescience” was able to assist anesthesiologists in predicting hypoxemia, in a clear example of how a relationship between humans and machines may outperform either one alone.44 Similarly, Olsen et al. showed a predictive PACU algorithm led to an impressive reduction in early signs of deterioration while also reducing false alarms.45 The second tier of focus for AR would be on interventions aimed at improving the longer-term recovery of patients (discussed below). In each tier of utilization, erroneous data and alarm fatigue will continually be addressed and improved upon, though there will likely never come a day where zero error or perfect signal-noise ratio exist.25,46 One question that remains unanswered, is whether the heads-up display is best via goggles, a contact lens, or a holographic display projected at the bedside. Currently, companies such as Humane, and other AI start-ups like it, are patenting technologies that utilize laser projection systems and incorporate seemingly disparate data such as 3-D cameras and heart rate sensors for next-generation technological paradigms in industries outside healthcare. But these companies may build next generation devices that replace all of the devices and interfaces we have come to rely upon (from computers, to handheld devices and smart watches). The Hollywood fantasy of dragging and dropping projected icons from thin air and interacting with data this way may be closer than we imagine.

(Let us get a picture of a PACU, 1st person, with several patients in their bays, and a heads up overlay on the screen showing “Red and green” with risk scores and needed interventions, for example, a healthy patient with a discharge notification and an active bed-assignment streaming versus a red-zone patient where the troponins came back and borderline vitals are displayed with suggested management steps displayed—or at least an option that says something like “suggest next steps”).

The first 30 days and beyond: the perioperative surgical home enters your home

Enhanced recovery protocols and perioperative surgical home concepts have been successful philosophical drivers of improved perioperative care up until now,47 but the future will see these concepts become literal, as patients’ homes become monitored settings. Despite amazing strides made by our specialty in decreasing preventable anesthetic mortality, the first 30 days following surgery account for a major source of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with about 5% of all surgical patients dying in the first year (and 10% in the 65 and older age group)48, and post-operative mortality is overall the third leading cause of death worldwide. The major focus in the first 30 days will likely remain MINS, acute kidney injury, brain health, bleeding and infection as preventable causes of death.49 As surgical care becomes increasingly decentralized from large healthcare settings and more complex procedures are performed in an ambulatory setting, this will require an extension of the concept of and responsibility for postoperative monitoring into patients’ homes. Several key components will be necessary to maintain safety and integrity of recovery in this eventual healthcare ecosystem.

To illustrate how this might unfold, let us consider a hypothetical case example: total knee replacement in a 65-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease. When done as a same-day surgery in an ASC, this patient’s recovery will be dependent on three key technological cornerstones to prevent the most common or worrisome 30-day complications (in this case, acute coronary syndromes, deep venous thrombosis and/or infectious complications). First, a reliable internet connection needs to exist in an affordable and universal way, allowing for two-way communication and data streaming between patient and provider. Next, affordable and reliable wearable devices or testing media will be needed for at-home monitoring. These can be classic commercially available watches, although they are limited by battery power at present. More robust technologies that have sufficient battery life can fulfill this role, as can “next generation” biosensors that stream real time vital sign and physiologic data50–52 along with relevant sweat-derived laboratory sampling data (e.g., lactate)53,54 to a central server with an AI “eye in the sky” that integrates these data and reports to a monitoring team. Finally, telemedicine will serve to connect the human on the other end of all this technological input. This will allow for further discernment of incoming data and prevent unnecessary hospitalizations while preemptively addressing serious events before they occur. Realistic development of these paradigms will require technological and workflow evolutions and revolutions. With all these elements in place, for the patient above the detection of gradual tachycardia and hypotension, rising skin lactate and a new fever would immediately alert the monitoring team of potential evolving infection at home, and trigger a telemedicine evaluation for triage of the evolving event. (See Figure 3)

Figure 3:

Based on prompts to Midjourney, a conceptualization of remote home monitoring, with a virtual “doctor” watching patients at home.

Other items that will see robust support and development include integrated team models of care where, for example, a patient who experienced MINS in the hospital can see a cardiologist within days of discharge. Similarly, a patient who experienced delirium can get added nursing care for their home stay, where disorientation might prevent early ambulation or proper self-care (e.g., wound care), but likely be of shorter duration than in the unfamiliar (but more highly monitored) inpatient setting where sleep and noise disturbances are more common and counterproductive. Wearables and telemedicine capabilities will be key in supporting all of this as well, with robotics/drones being essential to delivery of medical devices to patients’ homes. Telemedicine capabilities will also be useful for instructions for aspects of home care that may be new for recovering patients and their families or those who live in remote locations. As will be the case for intraoperative decision making, while the technology can enable new options, the decision making of the anesthesiologist will still be necessary to weigh the complex risks and benefits of deciding which of these patients is best served recovering at home as opposed to in the hospital.

The long arc of recovery following surgery must be centered on decreasing morbidity and mortality in the first year(s) and not simply the first 30 days. Predictive analytics at work during a patient’s hospitalization will provide information to postoperative care teams, delineating patients’ preoperative risk profiles, immediate perioperative (additive) risks (e.g., if they experienced sustain hypotension in the OR or at home) and how these might further predict untoward events or how they may be reversed in the longer recovery period. For example, had this theoretical patient experienced MINS after their knee replacement, in addition to physical therapy for their joint recovery, might cardiac rehabilitation and pharmacologic interventions be warranted? Such care plans will be clearer regarding not just the primary organs of concern in the perioperative setting (e.g., heart, brain, kidneys), but also with regards to cancer recurrence, chronic pain and opioid dependence and even surgical site and deep-tissue infections, making the first year after surgery safer than at any time in the prior decades, with a new all-cause mortality half of that recorded previously.

Moving beyond the technology.

All of these predictions only lead to more probing questions and these questions are as interesting as the predictions we may ponder. Who monitors, recovers and cares for patients once AI/ML/AR achieve widespread acceptance and validation? Who pays? What happens to patient consent for all this data to go “flying” into space and then beamed back down to a control center? Who owns the data? Who is qualified to integrate all this information and what is the bare minimum practitioner who can perform the monitoring role? What would an insurer think of this entire enterprise if it decreases mortality only very slightly? Might all this integration improve health equity? Might it worsen it? What is the environmental impact and footprint of all this extra plastic, electricity and chip usage?

The altered role of the anesthesiologist will necessitate changes in training, to be sure. What does training become for future anesthesiologists who would be expected to manage all of these disparate streams of information? Will there be both an anesthesiology-technologist and an anesthesiology-clinician pathway separation to serve these purposes? Initially, training to work with these modalities may be incorporated as a year-long fellowship (or longer) after a traditional residency in anesthesiology. However, it eventually is likely that many of these skills will be incorporated into residency to teach not only skills in the operating room (e.g., IV placement, intubation, medication titration) to decision-making in front of a computer screen in the control tower. This will require more than just technical skills but increased training in “soft science”-based subjects like ethics of healthcare, intraoperative decision-making for life-and-death circumstances, and interpersonal communication. Similar analogs can be found in the adoption of new modalities such as ultrasound and TEE which started as skills possessed by a few providers with advanced training but over time migrated into the mainstream.

While the practice model of the future will still rely heavily on ethical decisions and more complex decision making by anesthesiologists, autonomous machines may nevertheless become entangled in questions of liability in the face of bad outcomes. Faulty equipment, incorrect predictive algorithms, or even racist/biased machine learning55 may lead autonomous machines to potentially harm human patients. Who, or what, will be blamed when bad outcomes involving autonomous machines occur? Does the anesthesiologist have ultimate responsibility (as they do with residents or CRNAs), or are the manufacturers liable? At the present time, society is already starting to answer this question as posed by autonomous vehicles. At least for now, a popular approach to mitigating blameworthiness of machines is by ensuring that humans have at least “light” control over otherwise autonomous machines.56 Thus, the anesthesiologist in the control tower may always retain a certain degree of control over autonomous machines in the operating room, if for no other reason than to ensure that humans are ultimately liable for clinical outcomes.

Billing and regulatory requirements will need alteration. How are telemonitoring services reimbursed? Some models, such as the global fee for surgeons (which covers a preoperative and a certain period of postoperative visits) are challenging in a care team model and conflict with regulatory requirements of supervision ratios. However, potentially changing ratios (e.g., 1:10 anesthesiologist to CRNAs) brings up other questions of liability and oversight. These changes will need to be aligned if we are to allow for, and encourage, innovation. Even beyond the perioperative provider, will an insurance company be sufficiently incentivized to pay now for preventative care that may reduce complications years down the road?

Conclusions

As we noted initially, it is impossible to predict the future with any true accuracy. The only certainty is change, and the pace certainly seems to be accelerating. Consider the anesthesiologist who began practice 30 years ago. They have seen the introduction of propofol, rocuronium, and ondansetron in the first few years of their career. Automated blood pressure cuffs gained traction in operating rooms, and pulse oximetry quickly became a standard of care. It would seem impossible to practice today without these innovations, and yet, prior to their introduction that is exactly what our anesthesiology progenitors accomplished.

The developments of futuristic monitoring modalities that incorporate AI and wearable technology, to name a few, will similarly alter our specialty while building on its strong foundation. 40 years ago intraoperative mortality was a major concern for anesthesiologists. A combination of technical and system based changes has made this a less than six sigma event. However, postoperative morbidity and mortality has now risen to provide new challenges. The same ingenuity, willingness to change, and applications of technology will be necessary to make postoperative morbidity and mortality as rare tomorrow as intraoperative mortality is today.

Table:

Current Factors incorporated in MEWS versus Factors to be integrated in the future

| Current | Future | |

|---|---|---|

| Platform | Statistical/regression-driven | ML/AI-driven |

| Data sources | EMR | EMR, real-time hemodynamic monitors |

| Data points | Patient characteristics | Real time hemodynamic data |

| Surgical coding | Cognitive data | |

| Lab work | Surgical/OR video monitoring | |

| Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic determinants of health | ||

| Genetic/precision medicine screens |

Acknowledgements:

Dr. Hofer is the founder and President of Extrico health a company that helps hospitals leverage data from their electronic health record for decision making purposes. Dr. Hofer receives research support and serves as a consultant for Merck. This work was funded by NIH grant 1K01HL150318.

Footnotes

Contributions:

IH: This author helped with manuscript writing

MF: This author helped with manuscript writing

DK: This author helped with manuscript writing

SD: This author helped with manuscript writing

References

- 1.Fritz BA, Cui Z, Zhang M, He Y, Chen Y, Kronzer A, Abdallah A Ben, King CR, Avidan MS. Deep-learning model for predicting 30-day postoperative mortality. Br J Anaesth 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham J, Meng A, Holzer KJ, Brawer L, Casarella A, Avidan M, Politi MC. Exploring patient perspectives on telemedicine monitoring within the operating room. Int J Med Inform 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregory S, Murray-Torres TM, Fritz BA, Abdallah A Ben, Helsten DL, Wildes TS, Sharma A, Avidan MS. Study protocol for the Anesthesiology Control Tower—Feedback Alerts to Supplement Treatments (ACTFAST-3) trial: a pilot randomized controlled trial in intraoperative telemedicine. F1000Res 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frassanito L, Giuri PP, Vassalli F, Piersanti A, Garcia MIM, Sonnino C, Zanfini BA, Catarci S, Antonelli M, Draisci G. Hypotension Prediction Index guided Goal Directed therapy and the amount of Hypotension during Major Gynaecologic Oncologic Surgery: a Randomized Controlled clinical Trial. J Clin Monit Comput 2023. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37119322/. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.YANG S-M, CHO H-Y, LEE H-C, KIM H-S. Performance of the Hypotension Prediction Index in living donor liver transplant recipients. Minerva Anestesiol 2023;89. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37000016/. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Šribar A, Jurinjak IS, Almahariq H, Bandić I, Matošević J, Pejić J, Peršec J. Hypotension prediction index guided versus conventional goal directed therapy to reduce intraoperative hypotension during thoracic surgery: a randomized trial. BMC Anesthesiol 2023;23:101. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36997847/. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szrama J, Gradys A, Bartkowiak T, Woźniak A, Kusza K, Molnar Z. Intraoperative Hypotension Prediction-A Proactive Perioperative Hemodynamic Management-A Literature Review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59:491. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36984493/. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goudra B, Singh PM. Failure of sedasys: Destiny or poor design? In: Anesthesia and Analgesia., 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pambianco DJ, Vargo JJ, Pruitt RE, Hardi R, Martin JF. Computer-assisted personalized sedation for upper endoscopy and colonoscopy: a comparative, multicenter randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:765–72. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21168841/. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu C, Zhu Y, Wu L, Yu H, Liu J, Zhou F, Xiong Q, Wang S, Cui S, Huang X, Yin A, Xu T, Lei S, Xia Z. Evaluating the effect of an artificial intelligence system on the anesthesia quality control during gastrointestinal endoscopy with sedation: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol 2022;22. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36207701/. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Struys MMRF, De Smet T, Glen JB, Vereecke HEM, Absalom AR, Schnider TW. The History of Target-Controlled Infusion. Anesth Analg 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray-Torres TM, Wallace F, Bollini M, Avidan MS, Politi MC. Anesthesiology Control Tower: Feasibility Assessment to Support Translation (ACT-FAST)-a feasibility study protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2018;4:38. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29416871. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory S, Murray-Torres TM, Fritz BA, Abdallah A Ben, Helsten DL, Wildes TS, Sharma A, Avidan MS. Study protocol for the Anesthesiology Control Tower—Feedback Alerts to Supplement Treatments (ACTFAST-3) trial: a pilot randomized controlled trial in intraoperative telemedicine. F1000Res 2018;7:623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray-Torres T, Casarella A, Bollini M, Wallace F, Avidan MS, Politi MC. Anesthesiology Control Tower-Feasibility Assessment to Support Translation (ACTFAST): Mixed-Methods Study of a Novel Telemedicine-Based Support System for the Operating Room. JMIR Hum Factors 2019;6. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31012859/. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ZUCK D. Anaesthetic and postoperative recovery rooms: Some notes on their early history. Anaesthesia 1995;50:435–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barone CP, Pablo CS, Barone GW. A history of the PACU. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing 2003;18:237–41. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12923750/. Accessed June 11, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruth HS, Haugen FP, Grove DD. Anesthesia Study Commission; findings of 11 years’ activity. J Am Med Assoc 1947;135:881–4. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18897592/. Accessed June 11, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosero EB, Romito BT, Joshi GP. Failure to rescue: A quality indicator for postoperative care. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruetzler K, Khanna AK, Sessler DI. Myocardial Injury After Noncardiac Surgery: Preoperative, Intraoperative, and Postoperative Aspects, Implications, and Directions. Anesth Analg 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramaniyan S, Terrando N. Neuroinflammation and Perioperative Neurocognitive Disorders. Anesth Analg 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Lagadec MD, Dwyer T. Scoping review: The use of early warning systems for the identification of in-hospital patients at risk of deterioration. Australian Critical Care 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellini V, Rafano Carnà E, Russo M, Di Vincenzo F, Berghenti M, Baciarello M, Bignami E. Artificial intelligence and anesthesia: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med 2022;10:528–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenwald S, Chamoun GF, Chamoun NG, Clain D, Hong Z, Jordan R, Manberg PJ, Maheshwari K, Sessler DI. Risk Stratification Index 3.0, a Broad Set of Models for Predicting Adverse Events During and After Hospital Admission. Anesthesiology 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Culley DJ, Hashimoto DA, Witkowski E, Gao L, Meireles O, Rosman G. Artificial Intelligence in Anesthesiology Current Techniques, Clinical Applications, and Limitations. Anesthesiology 2020;132:379–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muralitharan S, Nelson W, Di S, McGillion M, Devereaux PJ, Barr NG, Petch J. Machine Learning-Based Early Warning Systems for Clinical Deterioration: Systematic Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res 2021;23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kia A, Timsina P, Joshi HN, Klang E, Gupta RR, Freeman RM, Reich DL, Tomlinson MS, Dudley JT, Kohli-Seth R, Mazumdar M, Levin MA. MEWS++: Enhancing the prediction of clinical deterioration in admitted patients through a machine learning model. J Clin Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue B, Li D, Lu C, King CR, Wildes T, Avidan MS, Kannampallil T, Abraham J. Use of Machine Learning to Develop and Evaluate Models Using Preoperative and Intraoperative Data to Identify Risks of Postoperative Complications. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan M, Puri S, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Feng Z, Ruppert M, Hashemighouchani H, Momcilovic P, Li X, Wang DZ, Bihorac A. Comparing clinical judgment with the MySurgeryRisk algorithm for preoperative risk assessment: A pilot usability study. Surgery (United States) 2019;165:1035–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon L, Austin P, Rudzicz F, Grantcharov T. MySurgeryRisk and Machine Learning: A Promising Start to Real-time Clinical Decision Support. Ann Surg 2019;269:E14–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bihorac A, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ebadi A, Motaei A, Madkour M, Pardalos PM, Lipori G, Hogan WR, Efron PA, Moore F, Moldawer LL, Wang DZ, Hobson CE, Rashidi P, Li X, Momcilovic P. MySurgeryRisk: Development and Validation of a Machine-learning Risk Algorithm for Major Complications and Death After Surgery. Ann Surg 2019;269:652–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L, Fabbri D, Lasko TA, Ehrenfeld JM, Wanderer JP. A System for Automated Determination of Perioperative Patient Acuity. J Med Syst 2018;42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palla K, Hyland SL, Posner K, Ghosh P, Nair B, Bristow M, Paleva Y, Williams B, Fong C, Van Cleve W, Long DR, Pauldine R, O’Hara K, Takeda K, Vavilala MS. Intraoperative prediction of postanaesthesia care unit hypotension. Br J Anaesth 2022;128:623–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Datta S, Loftus TJ, Ruppert MM, Giordano C, Upchurch GR, Rashidi P, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Bihorac A. Added Value of Intraoperative Data for Predicting Postoperative Complications: The MySurgeryRisk PostOp Extension. J Surg Res 2020;254:350–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward TM, Mascagni P, Madani A, Padoy N, Perretta S, Hashimoto DA. Surgical data science and artificial intelligence for surgical education. J Surg Oncol 2021;124:221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maier-Hein L, Eisenmann M, Sarikaya D, März K, Collins T, Malpani A, Fallert J, Feussner H, Giannarou S, Mascagni P, Nakawala H, Park A, Pugh C, Stoyanov D, Vedula SS, Cleary K, Fichtinger G, Forestier G, Gibaud B, Grantcharov T, Hashizume M, Heckmann-Nötzel D, Kenngott HG, Kikinis R, Mündermann L, Navab N, Onogur S, Roß T, Sznitman R, Taylor RH, et al. Surgical data science - from concepts toward clinical translation. Med Image Anal 2022;76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gil AM, Birdi S, Kishibe T, Grantcharov TP. Eye Tracking Use in Surgical Research: A Systematic Review. J Surg Res 2022;279:774–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Dalen ASHM, Jung JJ, Nieveen van Dijkum EJM, Buskens CJ, Grantcharov TP, Bemelman WA, Schijven MP. Analyzing and Discussing Human Factors Affecting Surgical Patient Safety Using Innovative Technology: Creating a Safer Operating Culture. J Patient Saf 2022;18:617–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruscic KJ, Hanidziar D, Shaw KM, Wiener-Kronish J, Shelton KT. Systems Anesthesiology: Integrating Insights From Diverse Disciplines to Improve Perioperative Care. Anesth Analg 2022;135:673–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Privorotskiy A, Garcia VA, Babbitt LE, Choi JE, Cata JP. Augmented reality in anesthesia, pain medicine and critical care: a narrative review. J Clin Monit Comput 2022;36:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGillion MH, Duceppe E, Allan K, Marcucci M, Yang S, Johnson AP, Ross-Howe S, Peter E, Scott T, Ouellette C, Henry S, Le Manach Y, Paré G, Downey B, Carroll SL, Mills J, Turner A, Clyne W, Dvirnik N, Mierdel S, Poole L, Nelson M, Harvey V, Good A, Pettit S, Sanchez K, Harsha P, Mohajer D, Ponnambalam S, Bhavnani S, et al. Postoperative Remote Automated Monitoring: Need for and State of the Science. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sweeney TE, Azad TD, Donato M, Haynes WA, Perumal TM, Henao R, Bermejo-Martin JF, Almansa R, Tamayo E, Howrylak JA, Choi A, Parnell GP, Tang B, Nichols M, Woods CW, Ginsburg GS, Kingsmore SF, Omberg L, Mangravite LM, Wong HR, Tsalik EL, Langley RJ, Khatri P. Unsupervised analysis of transcriptomics in bacterial sepsis across multiple datasets reveals three robust clusters. Crit Care Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen J, Blumenthal A, Cuellar-Partida G, Evans DM, Finfer S, Li Q, Ljungberg J, Myburgh J, Peach E, Powell J, Rajbhandari D, Rhodes A, Senabouth A, Venkatesh B. The relationship between adrenocortical candidate gene expression and clinical response to hydrocortisone in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reyes M, Filbin MR, Bhattacharyya RP, Billman K, Eisenhaure T, Hung DT, Levy BD, Baron RM, Blainey PC, Goldberg MB, Hacohen N. An immune-cell signature of bacterial sepsis. Nat Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundberg SM, Nair B, Vavilala MS, Horibe M, Eisses MJ, Adams T, Liston DE, Low DKW, Newman SF, Kim J, Lee SI. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat Biomed Eng 2018;2:749–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olsen RM, Aasvang EK, Meyhoff CS, Dissing Sorensen HB. Towards an automated multimodal clinical decision support system at the post anesthesia care unit. Comput Biol Med 2018;101:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kristiansen TB, Kristensen K, Uffelmann J, Brandslund I. Erroneous data: The Achilles’ heel of AI and personalized medicine. Front Digit Health 2022;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrison TG, Ronksley PE, James MT, Brindle ME, Ruzycki SM, Graham MM, McRae AD, Zarnke KB, McCaughey D, Ball CG, Dixon E, Hemmelgarn BR. The Perioperative Surgical Home, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery and how integration of these models may improve care for medically complex patients. Can J Surg 2021;64:E381–90. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34296705/. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon BC, Sigl JC. Anesthetic management and one-year mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2005;100:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devereaux PJ, Biccard BM, Sigamani A, Xavier D, Chan MTV, Srinathan SK, Walsh M, Abraham V, Pearse R, Wang CY, Sessler DI, Kurz A, Szczeklik W, Berwanger O, Villar JC, Malaga G, Garg AX, Chow CK, Ackland G, Patel A, Borges FK, Belley-Cote EP, Duceppe E, Spence J, Tandon V, Williams C, Sapsford RJ, Polanczyk CA, Tiboni M, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Association of Postoperative High-Sensitivity Troponin Levels With Myocardial Injury and 30-Day Mortality Among Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. JAMA 2017;317:1642–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim Y-S, Kim J, Chicas R, Xiuhtecutli N, Matthews J, Zavanelli N, Kwon S, Lee SH, Hertzberg VS, Yeo W-H, Kim Y-S, Kim J, Matthews J, Zavanelli N, Kwon S, Lee SH, Yeo W-H, Woodruff GW, Chicas R, Hertzberg VS, Petit PH, Xiuhtecutli N. Soft Wireless Bioelectronics Designed for Real-Time, Continuous Health Monitoring of Farmworkers. Adv Healthc Mater 2022;11. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/adhm.202200170. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zavanelli N, Kim H, Kim J, Herbert R, Mahmood M, Kim YS, Kwon S, Bolus NB, Torstrick FB, Lee CSD, Yeo WH. At-home wireless monitoring of acute hemodynamic disturbances to detect sleep apnea and sleep stages via a soft sternal patch. Sci Adv 2021;7:4146. Available at: https://www.science.org. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee SH, Kim YS, Yeo MK, Mahmood M, Zavanelli N, Chung C, Heo JY, Kim Y, Jung SS, Yeo WH. Fully portable continuous real-time auscultation with a soft wearable stethoscope designed for automated disease diagnosis. Sci Adv 2022;8:5867. Available at: https://www.science.org. Accessed May 19, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sempionatto JR, Lasalde-Ramírez JA, Mahato K, Wang J, Gao W. Wearable chemical sensors for biomarker discovery in the omics era. Nat Rev Chem 2022;6:899–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Min J, Tu J, Xu C, Lukas H, Shin S, Yang Y, Solomon SA, Mukasa D, Gao W. Skin-Interfaced Wearable Sweat Sensors for Precision Medicine. Chem Rev 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sveen W, Dewan M, Dexheimer JW. The Risk of Coding Racism into Pediatric Sepsis Care: The Necessity of Antiracism in Machine Learning. J Pediatr 2022;247:129–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taeihagh A, Lim HSM. Governing autonomous vehicles: emerging responses for safety, liability, privacy, cybersecurity, and industry risks. Transp Rev 2019;39:103–28. [Google Scholar]