The diagnosis of acute renal infarction is often delayed or missed. The condition is an important cause of renal loss and can point to serious cardiovascular disease.

CASE HISTORIES

Case 1

A man aged 62 and previously in good health was seen an hour after the abrupt onset of left iliac fossa pain and vomiting. He was afebrile, normotensive, and in sinus rhythm, and the only abnormality on examination was an area of tenderness in the lower left quadrant of the abdomen. Urine analysis, blood count, serum amylase, and tests of renal and liver function were all normal. A chest radiograph showed borderline cardiomegaly; abdominal X-ray was unremarkable. The pain improved with opioids and he was discharged home. He returned a week later, troubled by dull and unrelenting abdominal discomfort. This time he had epigastric tenderness and he was in atrial fibrillation. The electrocardiogram also showed borderline intraventricular conduction delay and non-specific repolarization abnormalities. The previous heart tracing was examined for signs of ventricular pre-excitation but none were found. (Blood specimens taken at this time subsequently revealed above-normal C-reactive protein [119 mg/L] and D-dimer [0.44 μg/mL] and normal serum amylase and renal function tests.) An intra-abdominal abscess was suspected and CT imaging was arranged, but he had a sudden cardiac arrest from which he could not be resuscitated.

Necropsy revealed extensive infarction of the left kidney, the artery to which was completely occluded by an embolus. From its appearance the infarction was judged to have occurred several days before death. The heart was greatly enlarged; the left ventricle in particular was severely hypertrophied. The heart valves were normal, and no intracardiac thrombus was found. Serial myocardial slices revealed no evidence of acute or old ischaemic changes, and the coronary arteries were only mildly atherosclerotic. Despite a diligent search including other abdominal organs and the brain, there was no evidence of embolism elsewhere. The death was attributed to a lethal arrhythmia that had arisen from previously unrecognized structural heart disease.

Case 2

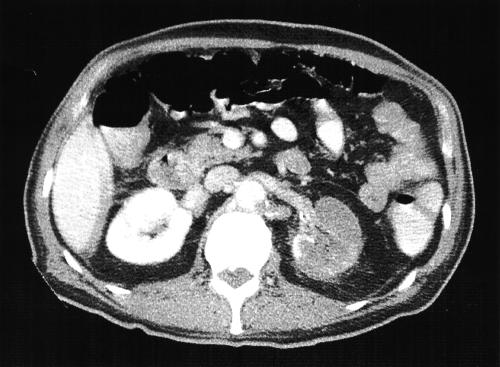

A man of 76 who had been experiencing intermittent angina for the past three months was seen after two days of left-sided flank pain and nausea. Two weeks previously, while on holiday in the USA, he had had a sudden and severe attack of right lower quadrant abdominal pain with vomiting. A CT scan there had revealed two hypodense lesions in his right kidney, thought to represent possible malignant disease, and a small splenic infarct was also noted. No gastrointestinal abnormalities were found. His abdominal pain was attributed to the muscular strain of vomiting and was treated with simple analgesics. Now he had a low-grade fever and a tender left loin and his urine contained blood and leukocytes. Serum creatinine was 150 μmol/L, lactate dehydrogenase 1694 U/L (reference range 270–620). CT revealed bilateral renal infarcts, more numerous in the left kidney (Figure 1) than the right; the left renal artery was also obstructed. At echocardiography the left ventricle was found to be dilated and severely impaired in function; its apex appeared aneurysmal and contained a mobile thrombus. He was anticoagulated and made a slow recovery.

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT in case 2

COMMENT

Renal infarction commonly occurs against a background of heart disease or a thromboembolic tendency.1 Although an intracardiac thrombus was not identified in case 1, the presence of atrial fibrillation and a structurally abnormal heart make this the likely source of his renal embolism. We suspect that it arose in the left atrium, as a result of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, because his left ventricle, although hypertrophied, had a geometrically normal lumen. Dilated cardiomyopathy is another risk factor,2 as demonstrated by case 2.

The manifestations of acute renal artery occlusion are non-specific and the diagnosis tends to be made late.1,3,4 Flank pain, persistent and often accompanied by nausea or vomiting, appears to be the most common initial symptom. Other presenting complaints include pain in the abdomen, back or chest. Small kidney infarcts can be painless and some patients present simply with fatigue.3 Positive findings on examination include fever, abdominal tenderness, and new-onset hypertension.4 Urine analysis may reveal red cells or protein or both; but it may also be normal.3,4 Blood levels of lactate dehydrogenase, C-reactive protein and aminotransferases are commonly raised;1,3,4 lactate dehydrogenase is probably the most useful marker, though non-specific. The diagnosis, once suspected, can be confirmed by contrast enhanced CT, isotope perfusion scanning or renal arteriography; conventional ultrasonography is insufficiently sensitive.1,4 On CT scanning in particular, a kidney infarct can be mistaken for malignant disease5 (as in case 2).

References

- 1.Domanovits H, Paulis M, Nikfardjam M, et al. Acute renal infarction. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999; 78: 386-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koniaris LS, Goldhaber SZ. Anticoagulation in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 31: 745-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iga K, Izumi C, Nakano A, et al. Problems in the initial diagnosis of renal infarction. Intern Med 1997; 36: 330-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lumerman JH, Hom D, Eiley D, et al. Heightened suspicion and rapid evaluation with CT for early diagnosis of partial renal infarction. J Endourol 1999; 13: 209-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzer O, Shirkhoda A, Jafri SZ, et al. CT features of renal infarction. Eur J Radiol 2002; 44: 59-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]