Abstract

Introduction: The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) pandemic has been slowed with the advent of anti-retroviral therapy (ART). However, ART is not a cure and as such has pushed the disease into a chronic infection. One potential cure strategy that has shown promise is the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/Cas gene editing system. It has recently been shown to successfully edit and/or excise the integrated provirus from infected cells and inhibit HIV-1 in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo. These studies have primarily been conducted with SpCas9 or SaCas9. However, additional Cas proteins are discovered regularly and modifications to these known proteins are being engineered. The alternative Cas molecules have different requirements for protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs) which impact the possible targetable regions of HIV-1. Other modifications to the Cas protein or gRNA handle impact the tolerance for mismatches between gRNA and the target. While reducing off-target risk, this impacts the ability to fully account for HIV-1 genetic variability.

Methods: This manuscript strives to examine these parameter choices using a computational approach for surveying the suitability of a Cas editor for HIV-1 gene editing. The Nominate, Diversify, Narrow, Filter (NDNF) pipeline measures the safety, broadness, and effectiveness of a pool of potential gRNAs for any PAM. This technique was used to evaluate 46 different potential Cas editors for their HIV therapeutic potential.

Results: Our examination revealed that broader PAMs that improve the targeting potential of editors like SaCas9 and LbCas12a have larger pools of useful gRNAs, while broader PAMs reduced the pool of useful SpCas9 gRNAs yet increased the breadth of targetable locations. Investigation of the mismatch tolerance of Cas editors indicates a 2-missmatch tolerance is an ideal balance between on-target sensitivity and off-target specificity. Of all of the Cas editors examined, SpCas-NG and SPRY-Cas9 had the highest number of overall safe, broad, and effective gRNAs against HIV.

Discussion: Currently, larger proteins and wider PAMs lead to better targeting capacity. This implies that research should either be targeted towards delivering longer payloads or towards increasing the breadth of currently available small Cas editors. With the discovery and adoption of additional Cas editors, it is important for researchers in the HIV-1 gene editing field to explore the wider world of Cas editors.

Keywords: gene therapy, CRiSPR/Cas, HIV-1, guideRNA, cure strategy

1 Introduction

The CRISPR/Cas system has revolutionized the field of genetic engineering and biotechnology with applications to provide a cure to genetic diseases affected at a single locus as well as people living with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (Liao et al., 2015; Atkins et al., 2021). The CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) system is a naturally occurring mechanism found in bacteria and archaea which serves as an adaptive immune system, enabling these organisms to defend against viral infections by storing and recognizing fragments of viral DNA. The Cas (CRISPR-associated) protein is a key component of the CRISPR system which acts as an effector molecule that carries out the DNA editing/cleaving function and is accompanied by the guide RNA (gRNA) which acts as a targeting scaffold for the Cas protein to interact with and recognize DNA and RNA targets via complementary base pairing.

Cas proteins are divided into two main classes: Class 1 systems use multiple Cas proteins while Class 2 effectors use a single, multidomain protein with all activities required for DNA/RNA interference. This makes them ideal for use in biomolecular delivery and genetic engineering. The Cas protein classes are further subdivided into types based on distinctive signatures and architecture of the Cas endonucleases; Class 1 systems include types I, III, and IV, while Class 2 systems contain types II (Cas9), V (Cas12), and VI (Cas13). Type II Cas9 effectors contain RuvC and HNH nuclease domains while type V Cas12 proteins have a single RuvC domain and type VI Cas13 proteins lack a DNase domain but have two conserved HEPN domains involved in RNA cleavage (Shmakov et al., 2017; Konermann et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019a; Yan et al., 2019; Makarova et al., 2020).

Cas proteins surveil the genome randomly and recognize a specific sequence of nucleotides referred to as the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site. Upon PAM recognition, base-pairing between the adjacent target site and the 20 bp protospacer sequence of the gRNA provides the programable targeting to a specific instance of a PAM site on the genome (Doench et al., 2014). Upon sufficient gRNA:target homology, the Cas protein cuts genomic DNA in either a blunt (type II effectors) or staggered (type V effectors) fashion. Engineering this system to target a specific genomic locus involves finding a suitable PAM site within the target of interest and constructing a gRNA to match the adjacent region. The PAM site of an effector is an important design consideration when targeting a genomic locus as it limits the space of targetable locations. Recent advances in molecular engineering of the Cas effector have targeted expanding the available PAM sites.

Gene length is another important consideration when choosing a Cas effector. The type II Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) is the most well characterized Cas system and has been effectively used in gene therapy, but in terms of biomolecular delivery the SpCas9 is 4,104 bases in length which limits compact delivery systems like adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors with a carrying capacity of 4.7 kilobases (Cong et al., 2013; Hsu et al., 2013). This has fueled research in the Cas9 ortholog from Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9) which is markedly smaller than SpCas9 at 3,159 bases (Nishimasu et al., 2015; Ran et al., 2015). However, SaCas9 recognizes a restrictive PAM site of NNGRRT limiting its targeting potential relative to the shorter NGG of SpCas9. The type V Cas12 effectors, previously known as Cpf1, recognize T-rich PAM sites. Several of these from Lachnospiraceae bacterium (LbCas12a), Acidaminococcus sp. (AsCas12a), and Francisella novicida (FnCas12a) have shown potential in human cells (Zetsche et al., 2015; Hirano et al., 2016a; Dong et al., 2016; Yamano et al., 2016; Acharya et al., 2019). The type VI Cas13 systems have almost no PAM requirement and target RNA for degradation (Abudayyeh et al., 2017).

In attempts to generate both compact and broad effector Cas proteins, scientists have deepened the search into Cas orthologs in a bid to identify Cas effectors that are small and have PAM sites that allow for more flexibility (Esvelt et al., 2013; Shmakov et al., 2015; Burstein et al., 2017; Shmakov et al., 2017; Harrington et al., 2018; Gasiunas et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). To this end, variants of the Cas proteins have been engineered through base-editing the amino acids around the PAM recognition domain to enhance the efficiency of the Cas protein, such as HypaCas9 and eSpCas9 (Slaymaker et al., 2016; Tycko et al., 2016; Schmid-Burgk et al., 2020), or to alter the PAM recognition site of the Cas effector, such as SpCas9-NG or SaCas9-KKH which recognize NG and NNNRRT, respectively (Kleinstiver et al., 2015a; Kleinstiver et al., 2015b; Anders et al., 2016; Hirano et al., 2016b; Gao et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2018; Yuen et al., 2022; Spasskaya et al., 2023). Therefore, the Cas system has significantly expanded as a toolbox for targeting DNA or RNA and these orthologs and variants of Cas effectors have yet to be fully explored for their use in targeting the HIV-1 provirus.

Both HIV-1 viral and host components, such as the co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 (Allen et al., 2018), have been targeted in HIV-1 cure strategies, but the integrated proviral DNA remains as the main target to eliminate the latent viral reservoirs (Liu et al., 2017c; Yin et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2019b). The high variability of HIV-1 sequences both within and among patients requires careful engineering of gRNAs which are both safe and effective as well as broad-spectrum (Sullivan et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2020; Sullivan et al., 2020; Allen et al., 2023). HIV-1-specific gRNAs have been designed which are capable of broadly targeting quasispecies, and now we further our exploration into CRISPR/Cas system engineering by querying potential orthologous and/or variant Cas proteins for targeting HIV-1. The earliest methodologies considered the sequence of a single lab-strain (Hu et al., 2014; Dampier et al., 2017). These evolved to consider genetic variability across databases (Roychoudhury et al., 2018), within single individuals (Dampier et al., 2018), and across subtypes (Chung et al., 2021).

Computational selection of gRNAs is a burgeoning field with tools available for most purposes. End-to-End tools like Benchling (2023) and CHOPCHOP (Labun et al., 2019) are able to guide a researcher through the selection and in silico screening of high-quality gRNAs. However, they are limited to pre-defined Cas and genome searches and cannot be tuned to nominate from one genome and evaluate off-targets in a different genome. Tools like Crisflash (Jacquin et al., 2019) can be used to find targets in variable sequences through the use of a Variant Call Format (vcf) file; however, this tool is tuned to mammalian genetics and cannot handle a quasispecies as a list of phases. Other tools like CRISPR MultiTargeter (Prykhozhij et al., 2015) are designed to find a protospacer that is repeated multiple times across a transcript to improve targeting. None of these, have the required features for the proposed analysis. This manuscript introduces a new paradigm in searching for Cas targets in HIV-1 to address these issues. We call this pipeline the: Nominate, Diversify, Narrow, Filter (NDNF) pipeline.

2 Results

2.1 Cas editor literature review

The literature search was conducted by reviewing publications from PubMed and Google Scholar with the queries for CRISPR and Cas as well as current and previous nomenclature for individual class 2 Cas proteins, HIV-1 and CCR5/CXCR4 (last searched 6/23/2023) and all relevant articles were reviewed. Information relevant to gene editing potential was collected into Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. This includes information like the name, source organism, PAM recognition site, protospacer size, gene size, induced mutations, and specific references related to current application in HIV-1.

TABLE 1.

Cas effector protein variants and orthologs with potential for use in targeting HIV-1.

N/A, not applicable; nt, nucleotide(s); aa, amino acids; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif; PFS, protospacer flanking sequence PS, protospacer; N, any base; R = A/G; Y = C/T; W = A/T;V = A/C/G; H = A/C/T; D = A/G/T; M = A/C; B = G/T/C.

Using this literature review as a guide, a computational pipeline was developed to interrogate each enzyme on the targetable space of HIV-1. This pipeline simplifies each enzyme to a PAM recognition site search. While this removes knowledge about position specific mismatch tolerance, that information is unknown for novel enzymes. The intent is instead, to consider each PAM equally and understand how that engineering choice impacts the targetable space of HIV-1.

2.2 Cas editor choice influences the targetable HIV-1 genome

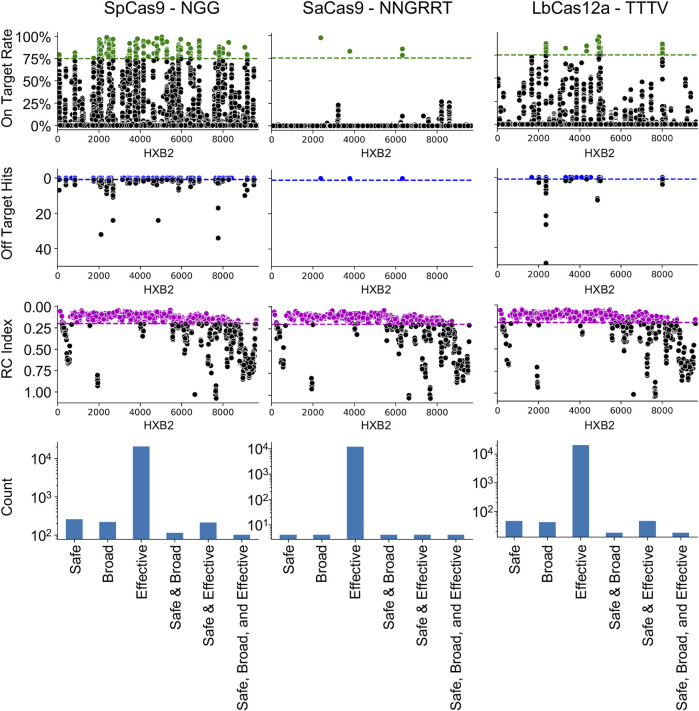

In brief, the NDNF pipeline considered all possible gRNAs nominated from a diverse set of HIV-1 sequences. These were further diversified through random mutations to a target pool size of 40,000. The pool was narrowed by comparison to an independent, globally representative set of HIV-1 genomes, labeling those capable of targeting >=75% of the sequences as broad. Finally, the gRNAs were filtered through a mismatch search against the human genome labeling only those with no hits as safe. Finally, in order to estimate the impact of mutations at a site, we considered an HIV-1 mutation dataset that interrogated the impact of point mutations on replication capacity to label gRNAs in areas of lethal mutations as effective. From this pipeline, each of the 40,000 potential gRNAs for each PAM was labeled as broad, safe, or effective, neither, or any combination. For the purposes of ranking and describing enzymes, we considered the number of gRNAs that were safe and broad and effective and termed them SBE gRNAs. The details of this pipeline are discussed in the Methods section.

The NDNF pipeline was first used on the three most common editors used in HIV-1 gene editing: SpCas9, SaCas9, and LbCas12a (Figure 1). The results demonstrated that the locations on HXB2 that are broadly targetable by the three different enzymes varies with SpCas9 having the largest number of SBE gRNAs (SBE = 75). Conversely, SaCas9, while having fewer broad targets, presented a better safety profile with fewer off-target risks (SBE = 9). LbCas12a had only 10 SBE gRNAs under this metric. All three enzymes target regions of lethal mutations across the HIV-1 genome (Figure 1: RC index).

FIGURE 1.

Cas9 editor influences the number of safe, broad, and effective (SBE) targets. Each column indicates the results of the NDNF pipeline for SpCas9 (left), SaCas9 (middle), and LbCas12a (right). The PAM sequence used is indicated in the graph labels. The top row indicates the broad gRNAs by plotting the on-target rate for each gRNA, those in green are above a 75% cutoff and considered broad. The second row indicates the safety of each gRNA by plotting the off-target count for each gRNA. Those with no hits are considered safe (above the blue line). The third row indicates the effectiveness of each gRNA by plotting the average RC index of the 40 bp window centered on the cut-site. The fourth row plots the counts of SBE gRNAs and their overlaps.

2.3 Mismatch tolerance is a double-edged sword

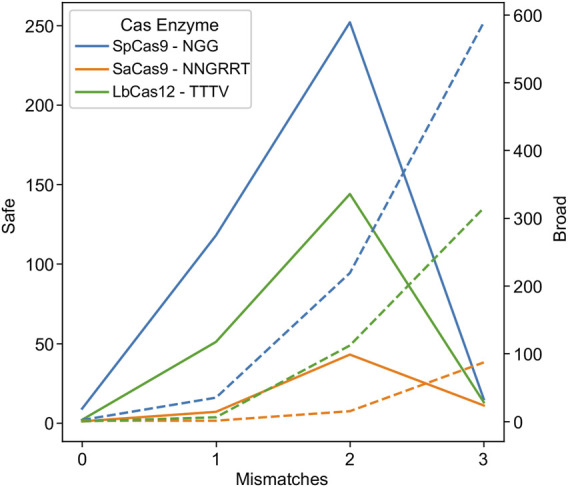

Researchers looking to reduce the risk of off-target effects have engineered mutations in the enzyme (Kleinstiver et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2023) or the sgRNA handle (Gupta et al., 2021) to require a tighter coupling between gRNA:target pairs before cleavage. This reduces the likelihood of an off-target effect, but conversely reduces the tolerance to HIV-1 genetic variability. In order to investigate this phenomenon and its impact on HIV-1 targeting, an experiment was performed where the mismatch tolerance was varied between 0 and 3 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Higher promiscuity leads to more broad targets but fewer safe ones. The number of safe gRNAs was calculated and plotted for the wild-type PAMs indicated in the key for SpCas9 (blue), SaCas9 (orange), and LbCas12a (green) in solid lines using the left axis. The number of broad gRNAs was calculated and plotted for the wild-type PAMs for SpCas9 (blue), SaCas9 (orange), and LbCas12a (green) in dotted lines using the right axis.

As hypothesized, low mismatch values led to few broad gRNAs, due to a decrease in the number of gRNAs that could target 75% of the validation dataset at a strict mismatch tolerance (Figure 2: dotted lines). Conversely, mismatch tolerances of three or greater led to a decrease in safe gRNAs, due to an ability to target increasingly distantly homologous human sites (Figure 2: solid lines). The ideal tradeoff between safe and broad was determined to be two mismatches for SpCas9, SaCas9, and LbCas12a, as shown by the peak in the solid lines in Figure 2.

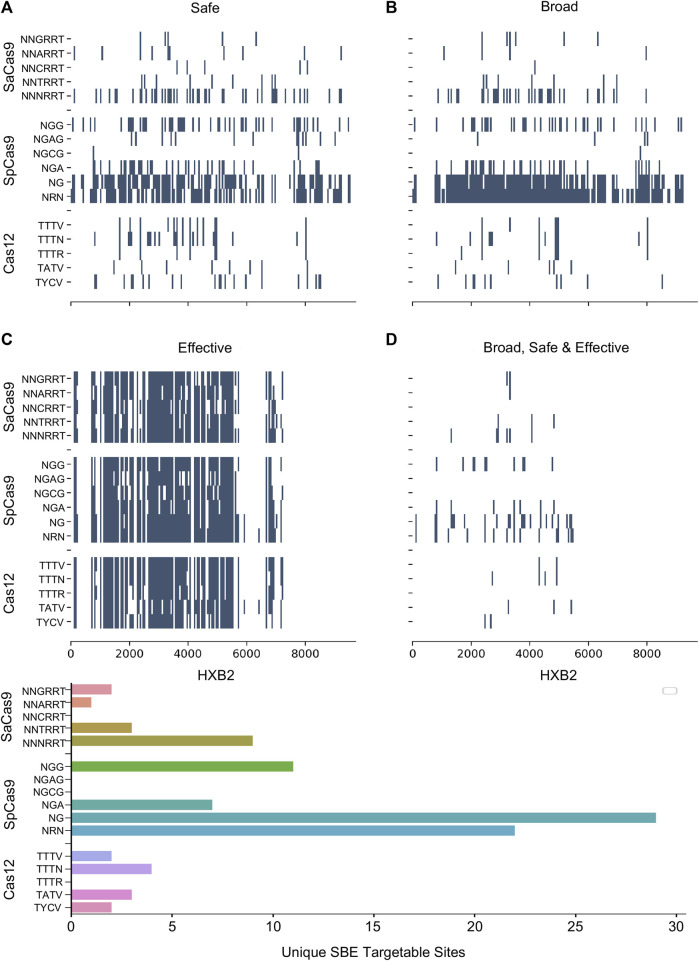

2.4 Modifications to PAM tolerance improves targetable sites

Numerous studies have generated Cas editor variants with altered PAM recognition sites described in Table 1. This can either be to broaden or restrict sites to increase targetable space or reduce off-target effects, respectively (Kleinstiver et al., 2015b; Hu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2022). The known modified PAMs for SpCas9, SaCas9, and LbCas12a were interrogated using the same NDNF pipeline (Figures 3A–D; Table 2). In each case, the broadening of the PAMs led to an increase in the number of targetable sites across the HIV-1 genome (Figure 3E). SaCas9 gains 28 new SBEs (9–37, Table 2) and can target 7 additional sites (Figure 3E) by moving from the NNGRRT to NNNRRT. LbCas12a gains 9 SBEs and 2 additional sites moving from TTTV to TTTN. SpCas9 has a mixed effect by moving to broader editors; changing from NGG to NG decreases the number of SBEs 75 versus 41 but increases the number of targetable sites from 11 to 29. Adjusting to the even broader NRN motif loses more SBEs (75 vs. 24) and only increases number of sites to 22.

FIGURE 3.

The pattern of targetable regions is altered by PAM mutations. For each of the SpCas9, SaCas9, and LbCas12a variants identified, the pattern of broad (A), safe (B), and effective (C) gRNA is plotted against the target position in the HXB2 reference genome. (D) Indicates the overlapping sites of safe, broad, and effective gRNAs. The counts of each category are provided in Table 2. E) A bar graph showing the number of unique genomic positions targetable by SBE gRNAs for each PAM choice.

TABLE 2.

The number of safe, broad, and effective (SBE) gRNAs found by the NDNF pipeline.

| Cas | PAM motif | Safe | Broad | Effective | SBE | Unique sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASp2Cas12l | CCY | 17 | 255 | 6,696 | 1 | 1 |

| AacCas12b | TTN | 6 | 1,047 | 8,946 | 1 | 1 |

| AsCas12a | TTTN | 14 | 329 | 8,427 | 3 | 2 |

| Asp2Cas12l | CCY | 11 | 267 | 6,742 | 2 | 1 |

| BthCas12b | ATTN | 12 | 135 | 7,379 | 8 | 2 |

| Cas12c2 | TN | 1 | 5,207 | 9,606 | 1 | 1 |

| Cas12d | TA | 7 | 850 | 8,809 | 0 | |

| Cas12e | TTCN | 19 | 83 | 6,313 | 0 | |

| Cas12h1 | RTR | 1 | 615 | 8,471 | 1 | 1 |

| Cas12j | TBN | 12 | 3,534 | 9,333 | 0 | |

| CasY | TA | 9 | 871 | 8,785 | 1 | 1 |

| CjeCas9 | NNNRYAC | 7 | 11 | 5,695 | 0 | |

| Cpf1-TATV | TATV | 41 | 21 | 6,981 | 6 | 3 |

| Cpf1-TTTN | TTTN | 132 | 105 | 8,573 | 19 | 4 |

| Cpf1-TTTR | TTTR | 48 | 35 | 6,710 | 0 | |

| Cpf1-TTTV | TTTV | 55 | 43 | 7,464 | 10 | 2 |

| Cpf1-TYCV | TYCV | 142 | 50 | 6,337 | 2 | 2 |

| ErCas12a | YTTN | 17 | 603 | 8,310 | 1 | 1 |

| FnCas12a | TTV | 8 | 529 | 7,900 | 1 | 1 |

| FnCas9-RHA | YG | 8 | 810 | 8,150 | 0 | |

| GeoCas9 | NNNNCRAA | 0 | 1 | 4,754 | 0 | |

| LbCas12a_Cpf1 | TTTN | 212 | 1,051 | 41,970 | 26 | 4 |

| Nme1Cas9 | NNNNGATT | 6 | 0 | 4,590 | 0 | |

| OspCas12c | TG | 11 | 595 | 7,912 | 0 | |

| SaCas9-KKH-A | NNARRT | 43 | 22 | 6,942 | 1 | 1 |

| SaCas9-KKH-C | NNCRRT | 33 | 2 | 6,043 | 0 | |

| SaCas9-KKH-N | NNNRRT | 236 | 227 | 8,808 | 37 | 9 |

| SaCas9-KKH-T | NNTRRT | 45 | 17 | 7,102 | 6 | 3 |

| SaCas9-WT | NNGRRT | 103 | 260 | 42,779 | 9 | 2 |

| SauriCas9 | NNGG | 27 | 600 | 7,841 | 5 | 4 |

| SauriCas9-KKH | NNRG | 11 | 1,936 | 8,506 | 1 | 1 |

| ScCas9 | NNG | 11 | 2,773 | 9,022 | 2 | 2 |

| SpCas9-EQR | NGAG | 62 | 22 | 5,033 | 0 | |

| SpCas9-NG | NG | 365 | 1,291 | 8,879 | 41 | 29 |

| SpCas9-VQR | NGA | 164 | 230 | 7,140 | 19 | 7 |

| SpCas9-VRER | NGCG | 6 | 4 | 3,852 | 0 | |

| SpCas9-WT | NGG | 633 | 2,027 | 46,571 | 73 | 14 |

| SpRY | NRN | 378 | 5,582 | 10,169 | 24 | 22 |

| SpaCas9 | NNGYRA | 3 | 11 | 6,290 | 1 | 1 |

| St1Cas9 | NNAGAAW | 27 | 15 | 4,716 | 11 | 1 |

| Un1Cas12f1 | TTTR | 16 | 110 | 6,724 | 0 | |

| spaCas9 | NNGYRA | 3 | 12 | 6,381 | 1 | 1 |

| xCas | NGN | 7 | 2,904 | 8,862 | 0 |

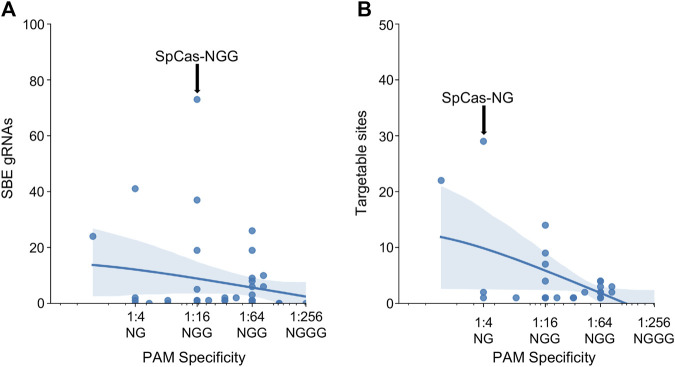

2.5 PAM specificity impacts targetability

After investigating the effect of specific PAM mutations for SpCas9, SaCas9, and LbCas12a, the exploration was broadened to all PAMs for all Cas molecules found across the study (N = 43). The PAM tolerance of each enzyme was plotted against the number of SBE gRNAs (Figure 4A) and unique targetable sites (Figure 4B). The analysis shows that more specific PAMs, those with lower levels of degeneracy, have less SBE gRNAs and target fewer unique sites in HIV-1. A regression was performed for SBE ∼ log10(PAM-promiscuity) and found no significant correlation. Alternatively, Unique-Sites ∼ log10(PAM-promiscuity) found a significant correlation (p = 0.0039) with a modest R 2 = 0.26.

FIGURE 4.

Increase PAM specificity leads to a decrease in SBE gRNAs and loss of targetable sites. The number of (A) SBE gRNAs and (B) targetable sites was plotted against the PAM specificity. The X-ticks are representative PAMs for each level of specificity. The blue line represents a y ∼ log(x) regression and the shadow indicates a 95% CI. A regression was performed for SBE ∼ log10(PAM-promiscuity) and found no significant correlation. Alternatively, Unique-Sites ∼ log10(PAM-promiscuity) found a significant correlation (p = 0.0039) with a modest R 2 = 0.26.

2.6 Numerical stability of estimates

Finally, the stability of the protospacers was evaluated for the SpCas9, SaCas9, and LbCas12a enzymes. A five-fold resampling was performed such that five different globally representative validation datasets were created along with the remaining nomination sets. For each of these samplings, the top 20,000 most common protospacers were collected. Figure 5A shows the likelihood of being nominated by 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 samplings. Most protospacers (82% SpCas9, 58% SaCas9, and 71% LbCas12a) are nominated in all five samplings with only a minority (4% SpCas9, 7% SaCas9, 7% LbCas12a) being nominated in a single sampling. Figure 5B shows the variability of the count between samplings. The average standard deviation across the same protospacer was (3.0 SpCas9, 0.8 SaCas9, and 1.7 LbCas12a). Together, these results indicate that one is unlikely to miss high-count protospacers during the nomination phase due to the sampling seed.

FIGURE 5.

Nomination and validation stages are unimpacted by random samplings. (A) The number of samplings each protospacer was nominated in during cross-validation. (B) A histogram of the standard deviation across each sampling for each protospacer. For (A) and (B) SpCas9 is in blue, SaCas9 is in orange, and Cpf1 is in green. (C) The mean validation hit rate was calculated across all samplings (x) and then was plotted against the hit rate obtained in each S(i) sampling (y). (D) A residual plot for the regression of Hit Rate S(i) ∼ Hit Rate Mean.

Evaluation of the validation stage was performed by first nominating the top 40,000 protospacers from the entire LANL dataset. Then, this set was then evaluated against each of the five samplings. Figure 5C shows the correlation between the mean score and the score generated from each sampling. The mean absolute error was calculated as 0.000425 indicating the value from each sampling is incredibly close to the average value. Figure 5D shows the residual between each sampling and the mean assuming a linear relationship. Some structure is observable with an increase in model variability near the 50% rate. As the purpose of this technique is to draw from the upper 75%, this is less concerning.

3 Discussion

As the HIV-1 gene editing field advances, it is important to look for advances in other areas of gene editing and how they can be optimally adapted. The wider gene editing field is extending the capabilities of Cas molecules and this manuscript presents a framework under which to evaluate different trade-offs being introduced into Cas systems. This study focused on exploring three major questions: 1) how Cas editors impact the targetable HIV-1 genome, 2) how mismatch tolerance impacts broad spectrum potential vs. off-target risk, and 3) how novel PAM variants enhance targeting potential.

This evaluation finds that the wider PAMs variants are a boon to HIV-1 gene editing. The NNNRRT PAM variants of SaCas9-KKH increases the number of SBE gRNAs and increases the number of targetable HIV-1 sites. The Cas12 system is new and has had less published molecular engineering, we explored other natural Type V PAMs and found the broader PAMs have more SBE gRNAs and more unique sites. New variants of the LbCas12a protein will likely widen the PAM. For SpCas9, the story is more complex, SpCas-NG and SpRY decrease the number of SBE gRNAs but increase the number of valid HIV-1 targets.

Mismatch tolerance is also an important tunable parameter. Our analysis indicates that for all editors, the peak of usefulness is at a 2-mismatch tolerance. Tuning the system to be more specific by decreasing the tolerance limits the ability of the system to cope with HIV-1 genetic variability. Similarly, adjusting the system to permit more mismatches may lead to unwanted off-target impacts.

This analysis is limited in several ways and should not be considered an exhaustive search for optimal anti-HIV-1 gRNAs for any Cas enzyme. This pipeline does not consider important parameters like position-specific mismatch penalties, differences in on-target gRNA activity, and considerations like CG content, poly-N-mers, etc. It is also reliant on a relatively small public dataset. Instead, it is intended as a framework to evaluate the effect of choices like PAM motif and mismatch tolerance on the feasibly targetable regions of the HIV-1 genome. It points to broader PAMs and a modest promiscuity of two mismatches.

There are also considerations beyond targeting potential when choosing a Cas editor. The size is a particularly notable one as it influences packaging efficiency across many delivery systems (Liu et al., 2017a). In those cases, smaller editors like SaCas9 and LbCas12a are attractive options. Another consideration is the type of edit and location relative to the PAM. Type II editors tend to cut near the PAM site, often leading to the erasure of the PAM site during DNA repair making retargeting difficult and leading to resistance profiles (Wang et al., 2016c; De Silva Feelixge et al., 2018). Conversely, Type V editors cut on the opposite side to the PAM, lowering this likelihood.

With these parameters taken together, it is difficult to arrive at a single definitive answer for the best Cas editor for HIV-1 targeting. The broad choice will be influenced by experimental setup, delivery strategy, and outcome variables. This manuscript indicates that it is useful to integrate editors with novel Cas mutations into next-generation strategies. This manuscript also indicates that techniques to decrease the mismatch penalty below 2 will reduce broad applicability and attempts to increase it above 2 will increase off-target effects. It is still early in the field of Cas9 gene editing and there will likely be further developments and improvements to Cas editors. HIV-1 researchers should stay abreast of upcoming technology to lead in the field.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Dataset

The dataset was constructed from the LANL full HIV-1 genome database from the Filtered web subset of full genome sequences including all sequences up to 2021 (last accessed 5/15/2023) and contains 4,725 sequences. However, this sequencing dataset is heavily biased towards Subtype B sequences (Figure 6A). To create a globally representative testing dataset, 1,497 sequences were randomly subsampled to match the proportions of global infections (Hemelaar et al., 2019) A: 10.3%, B: 12.1%, C: 46.6%, D: 2.7%, G: 4.6%, CRF01_AE: 5.3%, CRF02_AG: 7.7% (Figure 6B) and the remaining 3,228 sequences were used as the nomination dataset (Figure 6C).

FIGURE 6.

HIV-1 subtype distribution of full genomic sequences in the LANL dataset. (A) The entire 2021 LANL full genome dataset. (B) A subset of the LANL database randomly selected to be a globally representative validation dataset. (C) The remaining sequences used as a nomination set.

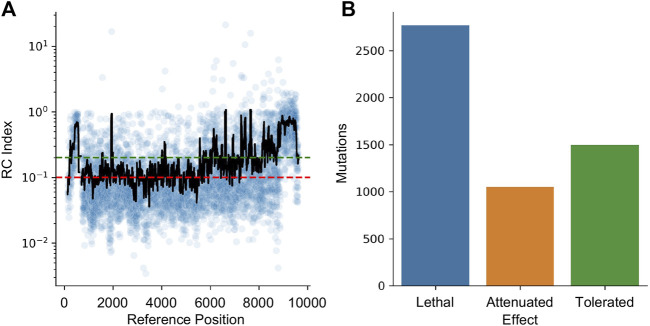

4.2 Estimating target effectiveness

HIV-1 is a highly mutable virus and as such, the impact of edits may be muted by a lack of functional impact. To quantify this effect, a dataset of random mutations was used to quantify the impact of variability across the genome. The dataset from Al-Mawsawi et al. was obtained from the Retrovirology Additional File #6 (last access 5/15/2023) (Al-Mawsawi et al., 2014). This experiment used random mutagenesis and subsequent selection to determine the Replicative Capacity (RC) index of each mutation. In their experiments, the RC index was calculated as the ratio of the frequency of the mutant in the 2nd passage to the frequency in the original infecting library; larger numbers indicating positive selection and smaller numbers indicating negative selection. The dataset was converted to HXB2 numbering and the RC index was averaged for all mutations reported within a 40 bpwindow centered at each position (Figure 7A). Using the cutoff from Al-Mawsawi et al., RC index below 0.1 is considered a lethal mutation, between 0.1 and 0.2 as attenuated, and above 0.2 as tolerated (Figure 7B). This cutoff found 2,771 sites where mutations are likely lethal, 1,052 sites that may lead to an attenuated phenotype, and 1,498 sites that are tolerant to mutations.

FIGURE 7.

The effect of mutations on HIV-1 replication capacity. (A) The RC index of each induced mutation was plotted in blue. The black line represents a 40 bp rolling average centered on each point. The red line indicates the maximum RC index of a lethal mutation (0.1) while the green line indicates the minimum value of a tolerated mutation (0.2). Between the green and red lines indicates attenuated. (B) The number of lethal, attenuated, and tolerated mutations is plotted.

4.3 Nominate, diversify, narrow, and filter (NDNF) pipeline

4.3.1 Nominate

The first step is to nominate potential protospacers from a collection of sequences. A custom python function was written to convert protospacer and PAM motifs into regular expressions targeting each strand. For example, the NGG SpCas9 PAM was converted into the regular expressions (.)[ACGT]GG and CC[ACGT](.). These regular expressions were then used to extract all extant protospacers in the nomination dataset. This was done independently for each Cas PAM motif. In our testing of 3,228 sequences, this yielded 5,000–3,00,000 unique protospacers depending on the promiscuity of the PAM.

4.3.2 Diversify

As the testing and nomination datasets are distinct, and the potential variability space of HIV-1 is vast, it is important to explore potential protospacers beyond those in the nomination dataset. The diversify step addresses this by randomly mutating the set of protospacers to create new ones. Custom python scripts (provided at https://github.com/DamLabResources/Cas_HIV_hits) were used to randomly change protospacers, keeping only unique ones. This randomization was run until there were 40,000 unique protospacers. This number of protospacers was chosen as a balance between an exhaustive search of all possible protospacers and the observation that rare protospacers are unlikely to be broadly targeting.

4.3.3 Narrow

The 40,000 unique protospacers were then evaluated against the validation dataset. CasOffinder was used to find all potential binding sites with mismatches (MM) in the protospacer; where MM was set to 2 for all experiments unless otherwise stated. All mismatch searches were performed with CasOffinder v2.4.1 (Bae et al., 2014). Due to limitations in CasOffinder v2.4.1 RNA and DNA bulges were not considered. Only protospacers which have matching sites within at least 75% of the validation dataset were considered broad and moved into the next stage. By introducing this filtering step, the computationally expensive search of the human genome can be limited to only those protospacers that are likely to be Safe, broad, and effective.

4.3.4 Filter

The broad-spectrum protospacers were then evaluated for off-target likelihood. Again, CasOffinder was used to search for all potential binding sites with 2 or fewer mismatches unless otherwise stated. A protospacer was deemed safe if there were 0 matching sites in the human genome (GRCh38, last access 5/15/2023) and unsafe if it had 1 or more hits.

4.4 Stability

The stability of this method to different samplings was tested through 5-fold resampling. In this, 5 different globally representative samplings were generated. The nomination stability was measured by nominating 40,000 protospacers from each of the folds and comparing the likelihood of being nominated in any given sampling and the deviation in the number of counts. The validation hit rate was tested by first nominating 40,000 protospacers from the entire dataset, to generate a consistent set of protospacers to evaluate. Subsequently, the 40,000 protospacers were tested against each of the five samplings to measure the difference between the hit rate measured in any given sampling to the mean of all samplings.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) R01 MH110360 (Contact PI, BW), NIMH Comprehensive NeuroAIDS Center (CNAC) P30 MH092177 (Kamel Khalili, PI; BW, PI of the Drexel subcontract), and the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 MH079785 (BW, Principal Investigator of the Drexel University College of Medicine component).

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://github.com/DamLabResources/Cas_HIV_hits.

Author contributions

Conceived idea and experimental design–WD, RB, MN, and BW. Performed experiments and data analysis—WD. Prepared manuscript WD, RB, MN, and BW. Intellectual contribution—WD, RB, MN, and BW. Critical reading of manuscript—WD, RB, MN, and BW. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The contents of the paper were solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgeed.2023.1248982/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abudayyeh O. O., Gootenberg J. S., Essletzbichler P., Han S., Joung J., Belanto J. J., et al. (2017). RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature 550, 280–284. 10.1038/nature24049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya S., Mishra A., Paul D., Ansari A. H., Azhar M., Kumar M., et al. (2019). Francisella novicida Cas9 interrogates genomic DNA with very high specificity and can be used for mammalian genome editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 20959–20968. 10.1073/pnas.1818461116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen A. G., Chung C. H., Atkins A., Dampier W., Khalili K., Nonnemacher M. R., et al. (2018). Gene editing of HIV-1 Co-receptors to prevent and/or cure virus infection. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2940. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen A. G., Chung C. H., Worrell S. D., Nwaozo G., Madrid R., Mele A. R., et al. (2023). Assessment of anti-HIV-1 guide RNA efficacy in cells containing the viral target sequence, corresponding gRNA, and CRISPR/Cas9. Front. Genome Ed. 5, 1101483. 10.3389/fgeed.2023.1101483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mawsawi, Wu N. C., Olson C. A., Shi V. C., Qi H., Zheng X., et al. (2014). High-throughput profiling of point mutations across the HIV-1 genome. Retrovirology 11, 124. 10.1186/s12977-014-0124-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders C., Bargsten K., Jinek M. (2016). Structural plasticity of PAM recognition by engineered variants of the RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Mol. Cell 61, 895–902. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D. A., Hudson T. R., Hodge C. A., Hampton T. H., Howell A. L., Hayden M. S. (2023). CAS12e (CASX2) CLEAVAGE OF CCR5: IMPACT OF GUIDE RNA LENGTH AND PAM SEQUENCE ON CLEAVAGE ACTIVITY. bioRxiv, 2023.01.02.522476. 10.1101/2023.01.02.522476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins A. J., Allen A. G., Dampier W., Haddad E. K., Nonnemacher M. R., Wigdahl B. (2021). HIV-1 cure strategies: why CRISPR? Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 21, 781–793. 10.1080/14712598.2021.1865302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S., Park J., Kim J. S. (2014). Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics 30, 1473–1475. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchling (2023). Benchling. [Google Scholar]

- Bogerd H. P., Kornepati A. V., Marshall J. B., Kennedy E. M., Cullen B. R. (2015). Specific induction of endogenous viral restriction factors using CRISPR/Cas-derived transcriptional activators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, E7249–E7256. 10.1073/pnas.1516305112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein D., Harrington L. B., Strutt S. C., Probst A. J., Anantharaman K., Thomas B. C., et al. (2017). New CRISPR-Cas systems from uncultivated microbes. Nature 542, 237–241. 10.1038/nature21059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. S., Ma E., Harrington L. B., Da Costa M., Tian X., Palefsky J. M., et al. (2018). CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science 360, 436–439. 10.1126/science.aar6245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Li Z., Shan R., Li Z., Wang S., Zhao W., et al. (2023). Modeling CRISPR-Cas13d on-target and off-target effects using machine learning approaches. Nat. Commun. 14, 752. 10.1038/s41467-023-36316-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C. H., Allen A. G., Atkins A. J., Sullivan N. T., Homan G., Costello R., et al. (2020). Safe CRISPR-cas9 inhibition of HIV-1 with high specificity and broad-spectrum activity by targeting LTR NF-κB binding sites. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 21, 965–982. 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C. H., Allen A. G., Atkins A., Link R. W., Nonnemacher M. R., Dampier W., et al. (2021). Computational design of gRNAs targeting genetic variants across HIV-1 subtypes for CRISPR-mediated antiviral therapy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 593077. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.593077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., et al. (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823. 10.1126/science.1231143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampier W., Sullivan N. T., Chung C. H., Mell J. C., Nonnemacher M. R., Wigdahl B. (2017). Designing broad-spectrum anti-HIV-1 gRNAs to target patient-derived variants. Sci. Rep. 7, 14413. 10.1038/s41598-017-12612-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampier W., Sullivan N. T., Mell J. C., Pirrone V., Ehrlich G. D., Chung C. H., et al. (2018). Broad-spectrum and personalized guide RNAs for CRISPR/Cas9 HIV-1 therapeutics. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 34, 950–960. 10.1089/AID.2017.0274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash P. K., Chen C., Kaminski R., Su H., Mancuso P., Sillman B., et al. (2023). CRISPR editing of CCR5 and HIV-1 facilitates viral elimination in antiretroviral drug-suppressed virus-infected humanized mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 120, e2217887120. 10.1073/pnas.2217887120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash P. K., Kaminski R., Bella R., Su H., Mathews S., Ahooyi T. M., et al. (2019). Sequential LASER ART and CRISPR treatments eliminate HIV-1 in a subset of infected humanized mice. Nat. Commun. 10, 2753. 10.1038/s41467-019-10366-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva Feelixge H. S., Stone D., Roychoudhury P., Aubert M., Jerome K. R. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9 and genome editing for viral disease-is resistance futile? ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 871–880. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench J. G., Hartenian E., Graham D. B., Tothova Z., Hegde M., Smith I., et al. (2014). Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1262–1267. 10.1038/nbt.3026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D., Ren K., Qiu X., Zheng J., Guo M., Guan X., et al. (2016). The crystal structure of Cpf1 in complex with CRISPR RNA. Nature 532, 522–526. 10.1038/nature17944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebina H., Misawa N., Kanemura Y., Koyanagi Y. (2013). Harnessing the CRISPR/Cas9 system to disrupt latent HIV-1 provirus. Sci. Rep. 3, 2510. 10.1038/srep02510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrke-Schulz E., Schiwon M., Leitner T., David S., Bergmann T., Liu J., et al. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9 delivery with one single adenoviral vector devoid of all viral genes. Sci. Rep. 7, 17113. 10.1038/s41598-017-17180-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esvelt K. M., Mali P., Braff J. L., Moosburner M., Yaung S. J., Church G. M. (2013). Orthogonal Cas9 proteins for RNA-guided gene regulation and editing. Nat. Methods 10, 1116–1121. 10.1038/nmeth.2681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M., Berkhout B., Herrera-Carrillo E. (2022). A combinatorial CRISPR-Cas12a attack on HIV DNA. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 25, 43–51. 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Cox D. B. T., Yan W. X., Manteiga J. C., Schneider M. W., Yamano T., et al. (2017). Engineered Cpf1 variants with altered PAM specificities. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 789–792. 10.1038/nbt.3900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Fan M., Das A. T., Herrera-Carrillo E., Berkhout B. (2020). Extinction of all infectious HIV in cell culture by the CRISPR-Cas12a system with only a single crRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 5527–5539. 10.1093/nar/gkaa226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasiunas G., Young J. K., Karvelis T., Kazlauskas D., Urbaitis T., Jasnauskaite M., et al. (2020). A catalogue of biochemically diverse CRISPR-Cas9 orthologs. Nat. Commun. 11, 5512. 10.1038/s41467-020-19344-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Gupta D., Ahmed K. T., Dey D., Singh R., Swarnakar S., et al. (2021). Modification of Cas9, gRNA and PAM: key to further regulate genome editing and its applications. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 178, 85–98. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2020.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington L. B., Burstein D., Chen J. S., Paez-Espino D., Ma E., Witte I. P., et al. (2018). Programmed DNA destruction by miniature CRISPR-Cas14 enzymes. Science 362, 839–842. 10.1126/science.aav4294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemelaar J., Elangovan R., Yun J., Dickson-Tetteh L., Fleminger I., Kirtley S., et al. (2019). Global and regional molecular epidemiology of HIV-1, 1990-2015: a systematic review, global survey, and trend analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19, 143–155. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30647-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovitz J., Hasan M., Patel M., Blomberg W. R., Cohen J. D., Machhi J., et al. (2021). CRISPR-Cas9 mediated exonic disruption for HIV-1 elimination. EBioMedicine 73, 103678. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano H., Gootenberg J. S., Horii T., Abudayyeh O. O., Kimura M., Hsu P. D., et al. (2016a). Structure and engineering of Francisella novicida Cas9. Cell 164, 950–961. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano S., Nishimasu H., Ishitani R., Nureki O. (2016b). Structural basis for the altered PAM specificities of engineered CRISPR-cas9. Mol. Cell 61, 886–894. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. D., Scott D. A., Weinstein J. A., Ran F. A., Konermann S., Agarwala V., et al. (2013). DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 827–832. 10.1038/nbt.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J. H., Miller S. M., Geurts M. H., Tang W., Chen L., Sun N., et al. (2018). Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 556, 57–63. 10.1038/nature26155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Kaminski R., Yang F., Zhang Y., Cosentino L., Li F., et al. (2014). RNA-directed gene editing specifically eradicates latent and prevents new HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 11461–11466. 10.1073/pnas.1405186111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Wang S., Zhang C., Gao N., Li M., Wang D., et al. (2020). A compact Cas9 ortholog from Staphylococcus Auricularis (SauriCas9) expands the DNA targeting scope. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000686. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin A. L. S., Odom D. T., Lukk M. (2019). Crisflash: open-source software to generate CRISPR guide RNAs against genomes annotated with individual variation. Bioinformatics 35, 3146–3147. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski R., Bella R., Yin C., Otte J., Ferrante P., Gendelman H. E., et al. (2016a). Excision of HIV-1 DNA by gene editing: a proof-of-concept in vivo study. Gene Ther. 23, 690–695. 10.1038/gt.2016.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski R., Chen Y., Fischer T., Tedaldi E., Napoli A., Zhang Y., et al. (2016b). Elimination of HIV-1 genomes from human T-lymphoid cells by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Sci. Rep. 6, 22555. 10.1038/srep22555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski R., Chen Y., Salkind J., Bella R., Young W. B., Ferrante P., et al. (2016c). Negative feedback regulation of HIV-1 by gene editing strategy. Sci. Rep. 6, 31527. 10.1038/srep31527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanal S., Cao D., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Schank M., Dang X., et al. (2022). Synthetic gRNA/cas9 ribonucleoprotein inhibits HIV reactivation and replication. Viruses 14, 1902. 10.3390/v14091902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. K., Lee S., Kim Y., Park J., Min S., Choi J. W., et al. (2020). High-throughput analysis of the activities of xCas9, SpCas9-NG and SpCas9 at matched and mismatched target sequences in human cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 111–124. 10.1038/s41551-019-0505-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. H., Kim N., Okafor I., Choi S., Min S., Lee J., et al. (2023). Sniper2L is a high-fidelity Cas9 variant with high activity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 972–980. 10.1038/s41589-023-01279-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver B. P., Pattanayak V., Prew M. S., Tsai S. Q., Nguyen N. T., Zheng Z., et al. (2016). High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 529, 490–495. 10.1038/nature16526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver B. P., Prew M. S., Tsai S. Q., Nguyen N. T., Topkar V. V., Zheng Z., et al. (2015a). Broadening the targeting range of Staphylococcus aureus CRISPR-Cas9 by modifying PAM recognition. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1293–1298. 10.1038/nbt.3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver B. P., Prew M. S., Tsai S. Q., Topkar V. V., Nguyen N. T., Zheng Z., et al. (2015b). Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature 523, 481–485. 10.1038/nature14592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipping F., Newby G. A., Eide C. R., Mcelroy A. N., Nielsen S. C., Smith K., et al. (2022). Disruption of HIV-1 co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 in primary human T cells and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells using base editing. Mol. Ther. 30, 130–144. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S., Lotfy P., Brideau N. J., Oki J., Shokhirev M. N., Hsu P. D. (2018). Transcriptome engineering with RNA-targeting type VI-D CRISPR effectors. Cell 173, 665–676. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysler A. R., Cromwell C. R., Tu T., Jovel J., Hubbard B. P. (2022). Guide RNAs containing universal bases enable Cas9/Cas12a recognition of polymorphic sequences. Nat. Commun. 13, 1617. 10.1038/s41467-022-29202-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labun K., Montague T. G., Krause M., Torres Cleuren Y. N., Tjeldnes H., Valen E. (2019). CHOPCHOP v3: expanding the CRISPR web toolbox beyond genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W171–W174. 10.1093/nar/gkz365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebbink R. J., De Jong D. C., Wolters F., Kruse E. M., Van Ham P. M., Wiertz E. J., et al. (2017). A combinational CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing approach can halt HIV replication and prevent viral escape. Sci. Rep. 7, 41968. 10.1038/srep41968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H. K., Gu Y., Diaz A., Marlett J., Takahashi Y., Li M., et al. (2015). Use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system as an intracellular defense against HIV-1 infection in human cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 6413. 10.1038/ncomms7413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Guan X., Du T., Jin W., Wu B., Liu Y., et al. (2015). Inhibition of HIV-1 infection of primary CD4+ T-cells by gene editing of CCR5 using adenovirus-delivered CRISPR/Cas9. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 2381–2393. 10.1099/vir.0.000139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Holguin L., Burnett J. C. (2022). CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene disruption of HIV-1 co-receptors confers broad resistance to infection in human T cells and humanized mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 24, 321–331. 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. J., Orlova N., Oakes B. L., Ma E., Spinner H. B., Baney K. L. M., et al. (2019). CasX enzymes comprise a distinct family of RNA-guided genome editors. Nature 566, 218–223. 10.1038/s41586-019-0908-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Zhang L., Liu H., Cheng K. (2017a). Delivery strategies of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing system for therapeutic applications. J. Control Release 266, 17–26. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Li X., Ma J., Li Z., You L., Wang J., et al. (2017b). The molecular architecture for RNA-guided RNA cleavage by Cas13a. Cell 170, 714–726. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Liang S. Q., Zheng C., Mintzer E., Zhao Y. G., Ponnienselvan K., et al. (2021a). Improved prime editors enable pathogenic allele correction and cancer modelling in adult mice. Nat. Commun. 12, 2121. 10.1038/s41467-021-22295-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhang X., Qi W., Yang Y., Liu Z., An T., et al. (2021b). Prevention and control strategies of african swine fever and progress on pig farm repopulation in China. Viruses 13, 2552. 10.3390/v13122552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Chen S., Jin X., Wang Q., Yang K., Li C., et al. (2017c). Genome editing of the HIV co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 by CRISPR-Cas9 protects CD4(+) T cells from HIV-1 infection. Cell Biosci. 7, 47. 10.1186/s13578-017-0174-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Liang J., Chen S., Wang K., Liu X., Liu B., et al. (2020). Genome editing of CCR5 by AsCpf1 renders CD4(+)T cells resistance to HIV-1 infection. Cell Biosci. 10, 85. 10.1186/s13578-020-00444-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma E., Chen K., Shi H., Stahl E. C., Adler B., Trinidad M., et al. (2022). Improved genome editing by an engineered CRISPR-Cas12a. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 12689–12701. 10.1093/nar/gkac1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Iranzo J., Shmakov S. A., Alkhnbashi O. S., Brouns S. J. J., et al. (2020). Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 67–83. 10.1038/s41579-019-0299-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K. M., Aach J., Guell M., Dicarlo J. E., et al. (2013). RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339, 823–826. 10.1126/science.1232033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H., Wilson H., Jayakumar S., Kulkarni V., Kulkarni S. (2021). Efficient inhibition of HIV using CRISPR/Cas13d nuclease system. Viruses 13, 1850. 10.3390/v13091850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimasu H., Cong L., Yan W. X., Ran F. A., Zetsche B., Li Y., et al. (2015). Crystal structure of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Cell 162, 1113–1126. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimasu H., Ran F. A., Hsu P. D., Konermann S., Shehata S. I., Dohmae N., et al. (2014). Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell 156, 935–949. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimasu H., Shi X., Ishiguro S., Gao L., Hirano S., Okazaki S., et al. (2018). Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease with expanded targeting space. Science 361, 1259–1262. 10.1126/science.aas9129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophinni Y., Inoue M., Kotaki T., Kameoka M. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9 system targeting regulatory genes of HIV-1 inhibits viral replication in infected T-cell cultures. Sci. Rep. 8, 7784. 10.1038/s41598-018-26190-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophinni Y., Miki S., Hayashi Y., Kameoka M. (2020). Multiplexed tat-targeting CRISPR-cas9 protects T cells from acute HIV-1 infection with inhibition of viral escape. Viruses 12, 1223. 10.3390/v12111223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oura S., Noda T., Morimura N., Hitoshi S., Nishimasu H., Nagai Y., et al. (2021). Precise CAG repeat contraction in a Huntington's Disease mouse model is enabled by gene editing with SpCas9-NG. Commun. Biol. 4, 771. 10.1038/s42003-021-02304-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prykhozhij S. V., Rajan V., Gaston D., Berman J. N. (2015). Correction: CRISPR MultiTargeter: a web tool to find common and unique CRISPR single guide RNA targets in a set of similar sequences. PLoS One 10, e0138634. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran F. A., Cong L., Yan W. X., Scott D. A., Gootenberg J. S., Kriz A. J., et al. (2015). In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature 520, 186–191. 10.1038/nature14299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran F. A., Hsu P. D., Lin C. Y., Gootenberg J. S., Konermann S., Trevino A. E., et al. (2013). Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell 154, 1380–1389. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychoudhury P., De Silva Feelixge H., Reeves D., Mayer B. T., Stone D., Schiffer J. T., et al. (2018). Viral diversity is an obligate consideration in CRISPR/Cas9 designs for targeting the HIV reservoir. BMC Biol. 16, 75. 10.1186/s12915-018-0544-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangree A. K., Griffith A. L., Szegletes Z. M., Roy P., Deweirdt P. C., Hegde M., et al. (2022). Benchmarking of SpCas9 variants enables deeper base editor screens of BRCA1 and BCL2. Nat. Commun. 13, 1318. 10.1038/s41467-022-28884-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller S. H., Rashad Y., Saleh F. M., Willingham K. A., Reilich A., Lin D., et al. (2022). Biallelic, selectable, knock-in targeting of CCR5 via CRISPR-cas9 mediated homology directed repair inhibits HIV-1 replication. Front. Immunol. 13, 821190. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.821190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid-Burgk J. L., Gao L., Li D., Gardner Z., Strecker J., Lash B., et al. (2020). Highly parallel profiling of Cas9 variant specificity. Mol. Cell 78, 794–800. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkova P., Vasileva A., Pobegalov G., Musharova O., Arseniev A., Kazalov M., et al. (2020). Position of Deltaproteobacteria Cas12e nuclease cleavage sites depends on spacer length of guide RNA. RNA Biol. 17, 1472–1479. 10.1080/15476286.2020.1777378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions K. J., Chen Y. Y., Hodge C. A., Hudson T. R., Eszterhas S. K., Hayden M. S., et al. (2020). Analysis of CRISPR/Cas9 guide RNA efficiency and specificity against genetically diverse HIV-1 isolates. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 36, 862–874. 10.1089/AID.2020.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmakov S., Abudayyeh O. O., Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Gootenberg J. S., Semenova E., et al. (2015). Discovery and functional characterization of diverse class 2 CRISPR-cas systems. Mol. Cell 60, 385–397. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmakov S., Smargon A., Scott D., Cox D., Pyzocha N., Yan W., et al. (2017). Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 169–182. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker I. M., Gao L., Zetsche B., Scott D. A., Yan W. X., Zhang F. (2016). Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 351, 84–88. 10.1126/science.aad5227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasskaya D. S., Davletshin A. I., Bachurin S. S., Tutyaeva V. V., Garbuz D. G., Karpov D. S. (2023). Improving the on-target activity of high-fidelity Cas9 editors by combining rational design and random mutagenesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 107, 2385–2401. 10.1007/s00253-023-12469-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan N. T., Allen A. G., Atkins A. J., Chung C. H., Dampier W., Nonnemacher M. R., et al. (2020). Designing safer CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics for HIV: defining factors that regulate and technologies used to detect off-target editing. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1872. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan N. T., Dampier W., Chung C. H., Allen A. G., Atkins A., Pirrone V., et al. (2019). Novel gRNA design pipeline to develop broad-spectrum CRISPR/Cas9 gRNAs for safe targeting of the HIV-1 quasispecies in patients. Sci. Rep. 9, 17088. 10.1038/s41598-019-52353-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng F., Cui T., Feng G., Guo L., Xu K., Gao Q., et al. (2018). Repurposing CRISPR-Cas12b for mammalian genome engineering. Cell Discov. 4, 63. 10.1038/s41421-018-0069-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tycko J., Myer V. E., Hsu P. D. (2016). Methods for optimizing CRISPR-cas9 genome editing specificity. Mol. Cell 63, 355–370. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Zhao N., Berkhout B., Das A. T. (2016a). A combinatorial CRISPR-cas9 attack on HIV-1 DNA extinguishes all infectious provirus in infected T cell cultures. Cell Rep. 17, 2819–2826. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Zhao N., Berkhout B., Das A. T. (2016b). CRISPR-Cas9 can inhibit HIV-1 replication but NHEJ repair facilitates virus escape. Mol. Ther. 24, 522–526. 10.1038/mt.2016.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Zhang C., Feng B. (2020). The rapidly advancing Class 2 CRISPR-Cas technologies: a customizable toolbox for molecular manipulations. J. Cell Mol. Med. 24, 3256–3270. 10.1111/jcmm.15039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Chen S., Xiao Q., Liu Z., Liu S., Hou P., et al. (2017). Genome modification of CXCR4 by Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 renders cells resistance to HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology 14, 51. 10.1186/s12977-017-0375-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Liu S., Liu Z., Ke Z., Li C., Yu X., et al. (2018). Genome scale screening identification of SaCas9/gRNAs for targeting HIV-1 provirus and suppression of HIV-1 infection. Virus Res. 250, 21–30. 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Pan Q., Gendron P., Zhu W., Guo F., Cen S., et al. (2016c). CRISPR/Cas9-Derived mutations both inhibit HIV-1 replication and accelerate viral escape. Cell Rep. 15, 481–489. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Scott D. A., Kriz A. J., Chiu A. C., Hsu P. D., Dadon D. B., et al. (2014). Genome-wide binding of the CRISPR endonuclease Cas9 in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 670–676. 10.1038/nbt.2889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Chen S., Wang Q., Liu Z., Liu S., Deng H., et al. (2019a). CCR5 editing by Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 in human primary CD4(+) T cells and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells promotes HIV-1 resistance and CD4(+) T cell enrichment in humanized mice. Retrovirology 16, 15. 10.1186/s12977-019-0477-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Guo D., Chen S. (2019b). Application of CRISPR/Cas9-Based gene editing in HIV-1/AIDS therapy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 69. 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Yang H., Gao Y., Chen Z., Xie L., Liu Y., et al. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated CCR5 ablation in human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells confers HIV-1 resistance in vivo . Mol. Ther. 25, 1782–1789. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T., Nishimasu H., Zetsche B., Hirano H., Slaymaker I. M., Li Y., et al. (2016). Crystal structure of Cpf1 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell 165, 949–962. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T., Zetsche B., Ishitani R., Zhang F., Nishimasu H., Nureki O. (2017). Structural basis for the canonical and non-canonical PAM recognition by CRISPR-cpf1. Mol. Cell 67, 633–645. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W. X., Chong S., Zhang H., Makarova K. S., Koonin E. V., Cheng D. R., et al. (2018). Cas13d is a compact RNA-targeting type VI CRISPR effector positively modulated by a WYL-domain-containing accessory protein. Mol. Cell 70, 327–339. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W. X., Hunnewell P., Alfonse L. E., Carte J. M., Keston-Smith E., Sothiselvam S., et al. (2019). Functionally diverse type V CRISPR-Cas systems. Science 363, 88–91. 10.1126/science.aav7271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Patel D. J. (2019). CasX: a new and small CRISPR gene-editing protein. Cell Res. 29, 345–346. 10.1038/s41422-019-0165-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Zhang T., Li F., Yang F., Putatunda R., Young W. B., et al. (2016). Functional screening of guide RNAs targeting the regulatory and structural HIV-1 viral genome for a cure of AIDS. AIDS 30, 1163–1174. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Zhang T., Qu X., Zhang Y., Putatunda R., Xiao X., et al. (2017). In vivo excision of HIV-1 provirus by saCas9 and multiplex single-guide RNAs in animal models. Mol. Ther. 25, 1168–1186. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L., Zhao F., Sun H., Wang Z., Huang Y., Zhu W., et al. (2020). CRISPR-Cas13a inhibits HIV-1 infection. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 21, 147–155. 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen C. T. L., Thean D. G. L., Chan B. K. C., Zhou P., Kwok C. C. S., Chu H. Y., et al. (2022). High-fidelity KKH variant of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 nucleases with improved base mismatch discrimination. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 1650–1660. 10.1093/nar/gkab1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetsche B., Gootenberg J. S., Abudayyeh O. O., Slaymaker I. M., Makarova K. S., Essletzbichler P., et al. (2015). Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 163, 759–771. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Ye Y., Ye W., Perculija V., Jiang H., Chen Y., et al. (2019a). Two HEPN domains dictate CRISPR RNA maturation and target cleavage in Cas13d. Nat. Commun. 10, 2544. 10.1038/s41467-019-10507-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Konermann S., Brideau N. J., Lotfy P., Wu X., Novick S. J., et al. (2018). Structural basis for the RNA-guided ribonuclease activity of CRISPR-cas13d. Cell 175, 212–223. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Yin J., Zhang-Ding Z., Xin C., Liu M., Wang Y., et al. (2021). In-depth assessment of the PAM compatibility and editing activities of Cas9 variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 8785–8795. 10.1093/nar/gkab507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ozono S., Yao W., Tobiume M., Yamaoka S., Kishigami S., et al. (2019b). CRISPR-mediated activation of endogenous BST-2/tetherin expression inhibits wild-type HIV-1 production. Sci. Rep. 9, 3134. 10.1038/s41598-019-40003-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Shi J., Mu Y. (2018). Dynamics changes of CRISPR-Cas9 systems induced by high fidelity mutations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 27439–27448. 10.1039/c8cp04226h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Lei R., Le Duff Y., Li J., Guo F., Wainberg M. A., et al. (2015). The CRISPR/Cas9 system inactivates latent HIV-1 proviral DNA. Retrovirology 12, 22. 10.1186/s12977-015-0150-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://github.com/DamLabResources/Cas_HIV_hits.