Abstract

The Metaverse, powered by a variety of key innovative technologies including 3D virtual reality (VR)/augmented reality (AR), artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain/cryptocurrency-based non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and the Internet of Things, has been proposed as the future of a virtual universe for education, work, business, and commerce. This research (∑ N = 954) presents the results of three cross-sectional surveys that examine the influence of third-level digital (in)equality and consumer (mis)trust on Metaverse adoption intention. Study 1, focusing on the Metaverse for hybrid education, reports the mediating effect of (mis)trust in the Metaverse on the relationship between the educational dimension of third-level digital (in)equality and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning as well as the moderating effect of social phobia. Study 2, focusing on the Metaverse for remote working, reports the mediating effect of (mis)trust in the Metaverse on the relationship between the economic labor dimension of third-level digital (in)equality and Metaverse adoption for virtual working as well as the moderating effect of neo-Luddism. Study 3, focusing on the Metaverse for business, reports the mediating effect of (mis)trust in the Metaverse on the relationship between the economic commerce dimension of third-level digital (in)equality and Metaverse adoption for virtual commerce as well as the moderating effect of blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception. This research can provide theoretical frameworks to examine people's hopes and fears about the Metaverse and consequential adoption versus non-adoption of the Metaverse for hybrid education, hybrid remote working, and omni-channel virtual commerce. Practical, managerial, and policy implications for the Metaverse and the NFT market are also discussed.

Keywords: metaverse, social phobia, neo-Luddism, blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency, virtual working, virtual commerce, non-fungible tokens (NFTs)

Introduction

The Metaverse, coined by cyberpunk author Neal Stephenson, was initially conceptualized as a virtual reality (VR)-based interface, where humans, in the form of virtual avatars, interact with one another in immersive virtual environments.1 “Virtual worlds,” “mirror worlds,” “augmented reality,” and “lifelogging” have been proposed as the four key components of the digital future of the Metaverse.2

In light of the evolving nature of the Metaverse in the emerging Web 3.0 environment, the Metaverse can be contemporarily defined as “a network of 3-D virtual worlds where people can interact, do business, and forge social connections through their virtual avatars.”3

More specifically, the Metaverse can be described as “an augmented digital world that is blending physical and virtual spaces through the use of extended reality (XR) and artificial intelligence-based systems for uses to interact, and/or trade virtual goods or services through cryptocurrencies (e.g., NFTs).”4(p18) The Metaverse has been proposed as the next big thing for social connection.5,6

In the Metaverse, people can engage in a variety of activities, including avatar-based real-time collaboration, multi-user game play, remote working, omni-channel marketing, virtual social gathering, hybrid learning, telemedicine, and so forth.7–10 Despite the great potential and many promises of the Metaverse, the interconnected nature of the Metaverse may raise users' concerns about personal privacy, information security, and (dis)trust in multi-user virtual environments (MUVE).11

The Metaverse environments integrating immersive VR and emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and Web 3.0, may introduce new paradigms for how we learn (shared, persistent, decentralized, and hybrid learning),5,12 how we work (e.g., hybrid, virtual, and remote work environments),5,13 and how we do business (e.g., virtual commerce via blockchain/cryptocurrency and virtual non-fungible tokens [NFTs]).13,14

The adoption and use of the Metaverse for hybrid education, remote work, and omni-channel business entail both promises and challenges. With regard to the potential of the Metaverse for hybrid education, the Metaverse can provide both instructors and students with alternative ways of teaching and learning such as engaging instructional strategy for inverted class/flipped classroom, collaborative learning via virtual avatars, diversification/scalability of the spectrum of teaching/learning curriculum according to instructors/students' research and academic needs, creation of virtual spaces for extracurricular activities, and so forth.12

Regarding the potential of the Metaverse for virtual working, the Metaverse can be proposed a virtual workplace solution that provides platforms for virtual offices, meeting rooms in real-time, efficient employee skill development/training, immersive teamwork/collaboration, and more.3

Metaverse may also offer exciting opportunities for virtual commerce such that there is an emerging business model of providing new products to consumers' avatars, which is called Direct-to-Avatar (D2A) model.15 The Metaverse also aligns with an emerging consumer marketing trend of “experiential luxury,” which indulges consumers' senses on multiple levels, transporting consumers to an immersive environment.16

In light of the potential ethical issues in the Metaverse, the current study proposes theoretical models and presents empirical data on the predictors of users' (dis)trust and behavioral intention (not) to adopt the Metaverse in (a) interactive learning environments for virtual learning, (b) hybrid work environments for virtual working, and (c) integrated marketing environments for virtual commerce.

The conceptual and theoretical models propose relevant variables as predictors of (non)adoption of the Metaverse, including (a) third-level digital inequality17 (i.e., gaps in users' capacity to translate their digital access and use into offline outcomes and resources); (b) concerns about privacy and data security11 in the Metaverse; and (c) feelings of (dis)trust in the Metaverse. The models propose positive correlations among “equality, trust, and adoption” as well as positive correlations among “inequality, mistrust, and non-adoption.”

This study also aims at examining the moderating effects of users' (a) social phobia (defined as “anxiety or apprehension experienced in social or performance situations”),18(p94),19 (b) neo-Luddism (referring to “critical evaluation of our relationship with technology” and “the task of putting new technology to examination”)20(pp263,266),21 perspective, and (c) blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency (blockchain referring to “a distributed database that stores transactions in cryptographically linked blocks, which creates an immutable ledger”13(p605) and blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency defined as “establishment and maintenance of the decentralized database network which is stored in the chronological order of cryptographically time-stamped entries which cannot be manipulated, amended, or removed”)22(p3) on intention to use the Metaverse for (a) virtual education; (b) virtual working; and (c) virtual commerce, respectively.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

One of the important principles for designing a humane Metaverse is to embrace inclusion and equity.23 The first-level digital inequality refers to unequal access to the Internet,24 whereas the second-level digital inequality refers to inequalities in Internet skills and uses.25 The third-level digital divides refer to differences in the gains from Internet use.26

“Third-level divides, therefore, relate to gaps in individuals' capacity to translate their Internet access and use into favorable offline outcomes.”17 (p30) It can be predicted that people with higher (vs. lower) educational/economic/commercial digital access and usage show higher (vs. lower) trust in the Metaverse (H1/H5/H9) since they tend to believe that they can further (vs. cannot) benefit from access to and usage of emerging technologies.

Their trust (vs. mistrust) in the Metaverse, in turn, will be a positive antecedent of intention to adopt (vs. not to adopt) the Metaverse for virtual learning/virtual working/virtual commerce (H2/H6/H10). Trust is an important mediator in consumers' adoption of a variety of emerging technologies (H3/H7/H11).22,27,28

The potential of VR as an educational and diagnostic tool for people with social anxiety has been reported.29–31 Prior research has explicated the theoretical relevance of social phobia to VR-based education.29–31 People with different levels of social phobia may indicate differential levels of Metaverse adoption intention, depending on their capacity to translate their digital access into educational outcomes in the real world.

It can be hypothesized that there will be a two-way interaction effect of the educational dimension of the third-level digital (in)equality and social phobia such that highly social phobic consumers with lower digital resources (higher digital inequality) may adopt the Metaverse as an educational solution to mitigate their social anxiety, whereas consumers with higher digital resources (lower digital inequality) are willing to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning regardless of their social phobia level (H4).

The emergence of AI that may surpass human intelligence is perceived as a threat to human existence.32 Neo-Luddism serves as relief from the fear of the eerie and the unknown.33,34 Neo-Luddism is historically rooted in “Luddites” and the concept of “Luddism” (human resistance to and protesting against the introduction of machinery perceived as a threat to human labor in working environments).34

Thus, neo-Luddism is theoretically relevant to the “labor” dimension of digital (in)equality in the contemporary context of the digital transformation of employment.35 AI-driven digital transformation of the economy and consequent ramifications for labor markets35 makes it imperative to examine the role of neo-Luddism in relation to the emerging concept of the Metaverse-based working environment.

Therefore, it can be hypothesized that there will be a two-way interaction effect of the economic labor dimension of the third-level digital (in)equality and neo-Luddism such that people with high neo-Luddism with lower digital resources (higher digital inequality) are least likely to adopt the Metaverse for virtual working whereas those with higher digital resources (lower digital inequality) and lower neo-Luddism are most likely to adopt the Metaverse for virtual working (H8).

Blockchain technologies, which fuel and drive innovation and increase efficiencies in a variety of new domains including creative digital arts rights management, supply chain management, entrepreneurship, health care, etc., form the bedrock for cryptocurrencies and play a vital role in virtual commerce.36 Transparency refers to “the extent to which information is easily accessible to both counterparts in exchange and external observers.”37(p4) Blockchain transparency is an important factor to consider in Metaverse-based virtual commerce since “a platform that allows the maintenance of a common database for consumers devoid of a trusted central controller”22(p3) may impact consumers' adoption of the emerging platform for virtual commerce.

Transparency, therefore, is a fundamental parameter of blockchain technology37 in the novel context of virtual commerce in the Metaverse. It can be hypothesized that there will be a two-way interaction effect of the economic commerce dimension of the third-level digital (in)equality and blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception such that people with higher blockchain transparency perception with higher digital resources (lower digital inequality) are most likely to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce whereas those with lower digital resources (higher digital inequality) and lower blockchain transparency perception are least likely to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce (H12).

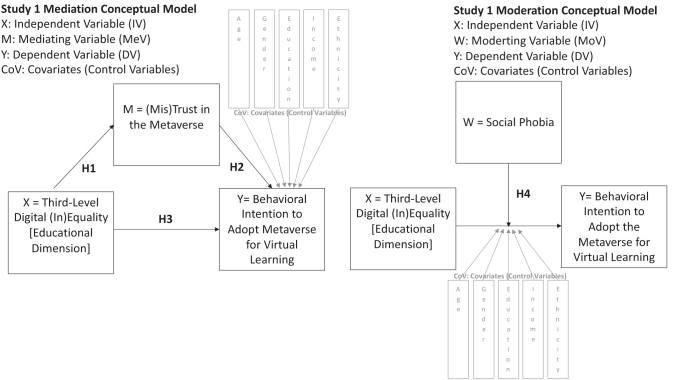

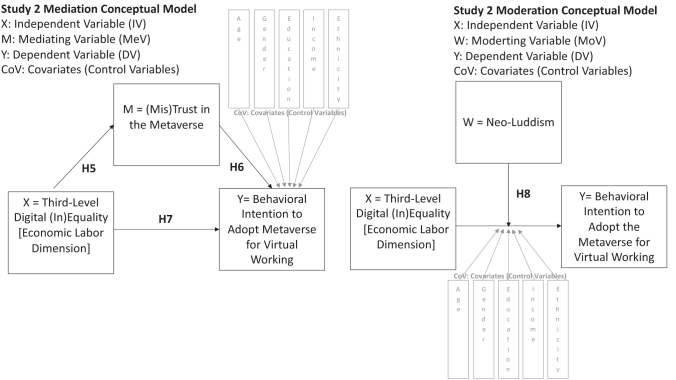

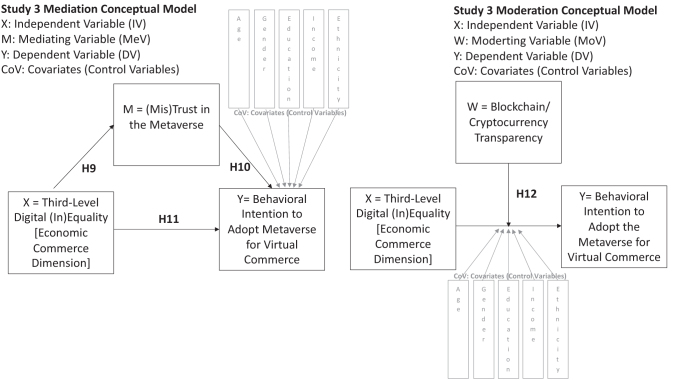

Based on these theoretical rationales and preliminary empirical findings, the following hypotheses are proposed for Study 1 (H1, H2, H3, and H4), Study 2 (H5, H6, H7, and H8), and Study 3 (H9, H10, H11, and H12) and the conceptual models are presented in Figures 1–3, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Study 1: mediation conceptual model (left) and moderation conceptual model (right).

FIG. 2.

Study 2: mediation conceptual model (left) and moderation conceptual model (right).

FIG. 3.

Study 3: mediation conceptual model (left) and moderation conceptual model (right).

H1: The third-level digital inequality (educational dimension) is a negative predictor of trust in the Metaverse (People's capacity to translate their digital access and use into offline educational outcomes and resources is a positive predictor of trust in the Metaverse).

H2: Trust in the Metaverse is a positive predictor of behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning.

H3: Trust mediates the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (educational dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning.

H4: Social phobia moderates the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (educational dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning.

H5: The third-level digital inequality (economic labor dimension) is a negative predictor of trust in the Metaverse (People's capacity to translate their digital access and use into offline economic labor outcomes and resources is a positive predictor of trust in the Metaverse).

H6: Trust in the Metaverse is a positive predictor of behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for remote working.

H7: Trust mediates the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (economic labor dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual working.

H8: Neo-Luddism moderates the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (economic labor dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual working.

H9: The third-level digital inequality (economic commerce dimension) is a negative predictor of trust in the Metaverse (People's capacity to translate their digital access and use into e-commerce outcomes and resources is a positive predictor of trust in the Metaverse).

H10: Trust in the Metaverse is a positive predictor of behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce.

H11: Trust mediates the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (economic commerce dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce.

H12: Blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception moderates the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (economic commerce dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce.

Methods

Control variables (covariates) and outlier control

Participants' demographic variables (age, gender, education level, income level, and ethnicity)17 were measured as statically controlled variables and entered in the PROCESS models as covariates. Regarding outlier control and outlier elimination procedure, three Distance criteria (Mahalanobis, Cook's, and Leverage values) in the SPSS regression analysis were examined. Based on the results of the outlier elimination procedure, outliers were excluded from the final data analysis.

Respondents, procedure, and measures

Participants were recruited from the CloudResearch Prime Panels38 in November 2022. Using the CloudResearch filtering criterion,38 participants were allowed to participate in only one of the three surveys. The principal investigator received approval from the university's institutional review board (IRB) before data collection. A total of 954 U.S. residents (Study 1: N = 321 after outlier elimination; Study 2: N = 318 after outlier elimination; Study 3: N = 315 after outlier elimination) completed the survey. Socio-demographic profiles of the participants in each study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Profiles of Participants in Study 1, Study 2, and Study 3

| Demographic variables | Categories | Study 1 (N = 321), percent | Study 2 (N = 318), percent | Study 3 (N = 315), percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Females | 60.4 | 61 | 66.3 |

| Males | 38.9 | 37.7 | 33.7 | |

| Others | 0.1 | 0.6 | ||

| Preferred not to answer | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||

| Age | ≤45 | 49.2 | 52.8 | 44.6 |

| ≤65 | 24.8 | 28 | 32.2 | |

| 66+ | 26 | 19.2 | 23.2 | |

| Education | High school | 31.7 | 39.6 | 34 |

| College | 54.2 | 50.4 | 55.2 | |

| Masters, PhD, above | 12.5 | 10 | 10.5 | |

| Preferred not to answer | 1.5 | 0.3 | ||

| Income | ≤$49,999 | 51.7 | 62.2 | 52.1 |

| ≤$99,999 | 27 | 24.5 | 28.6 | |

| ≤$149,999 | 11 | 7.6 | 10.1 | |

| $150,000+ | 6.9 | 3.8 | 6 | |

| Preferred not to answer | 3.4 | 1.9 | 3.2 | |

| Ethnicity | White/Caucasian | 71.8 | 67.9 | 75.9 |

| Black/African American | 16.9 | 19.2 | 15.2 | |

| Hispanic/Latin American | 5 | 3.5 | 3.8 | |

| Asian/Asian Indian | 3.1 | 4.4 | 4.1 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.3 | 0.9 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.3 | 0.3 | ||

| Mixed race | 0.9 | 2.8 | 0.3 | |

| Other | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Preferred not to answer | 1.6 | 0.6 | ||

| Metaverse awareness | Yes vs. No | 68.3 vs. 31.7 | 73.2 vs. 26.8 | 66.3 vs. 33.7 |

| Metaverse experience | Yes vs. No | 18.8 vs. 81.2 | 22.7 vs. 77.3 | 21 vs. 79 |

| Metaverse dissemination | Yes vs. No | 12.8 vs. 87.2 | 20.8 vs. 79.2 | 14.6 vs. 85.4 |

Participants' awareness of, experience with, and dissemination of the Metaverse were measured with three questions (“Have you ever heard of a new technology called the Metaverse?,” “Have you ever experienced the Metaverse?,” “Have you ever used social media to share your Metaverse experience?”) with dichotomous scales (Yes/No) (Table 1).

After measuring participants' awareness, experience, and dissemination, a brief description about the concept of the Metaverse was provided (“Metaverse is an AI-powered virtual world in which people can work, learn, shop, and interact with others. The Metaverse uses virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to transport people to a virtual world.”).

Third-level digital inequality, as the independent variable, was measured with the third-level digital divide scales17 (e.g., “Through the Internet ….” “I followed a course that I would not have been able to follow offline” [educational dimension] for Study 1 [Cronbach's α = 0.821]; “I found a (better) job” [economic labor dimension] for Study 2 [Cronbach's α = 0.892]; “I bought a product more cheaply than I could in the local store” [economic commerce dimension] for Study 3 [Cronbach's α = 0.844]). Trust, as the mediator, was measured with the four items from consumer trust scale39 (e.g., “The Metaverse can be relied on to keep its promises” [Study 1 Cronbach's α = 0.961; Study 2 Cronbach's α = 0.957; Study 3 Cronbach's α = 0.958]).

Behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse, as the dependent variable, was measured with items from the system adoption intention scale40 (e.g., “I intend to use Metaverse for virtual learning in the near future” Study 1 [Cronbach's α = 0.980]; “for virtual working” Study 2 [Cronbach's α = 0.980]; “for virtual commerce” for Study 3 [Cronbach's α = 0.976]).

Social phobia, as the moderator for Study 1, was measured with five items from the social phobia inventory (e.g., “Being embarrassed or looking stupid are among my worst fears” [Cronbach's α = 0.924]).19,41 Neo-luddism, as the moderator for Study 2, was measured with five items21 (e.g., “The Metaverse makes people lose their jobs” [Cronbach's α = 0.904]). Blockchain transparency, as the moderator for Study 3, was measured with three items22 (e.g., “Blockchain is a transparent technology” [Cronbach's α = 0.822]). Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlation

| Variables | M | SD | 1-1. | 1-2. | 1-3. | 1-4. | 2-1. | 2-2. | 2-3. | 2-4. | 3-1. | 3-2. | 3-3. | 3-4. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (N = 321) | ||||||||||||||

| 1-1. Digital equality (education) | 4.1485 | 1.8363 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 1-2. Trust in the Metaverse | 4.3411 | 1.7004 | 0.491** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 1-3. Social phobia | 3.4696 | 1.7164 | 0.214** | 0.138** | 1 | |||||||||

| 1-4. Metaverse adoption for virtual learning | 4.1246 | 1.9689 | 0.581** | 0.791** | 0.154** | 1 | ||||||||

| Study 2 (N = 318) | ||||||||||||||

| 2-1. Digital equality (labor) | 4.5314 | 1.6541 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2-2. Trust in the Metaverse | 4.2366 | 1.7583 | 0.661** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2-3. Neo-Luddism | 3.8698 | 1.6872 | −0.167* | −0.258** | 1 | |||||||||

| 2-4. Metaverse adoption for virtual working | 3.7742 | 2.0688 | 0.658** | 0.750** | −0.152** | 1 | ||||||||

| Study 3 (N = 315) | ||||||||||||||

| 3-1. Digital equality (economic commerce) | 4.7676 | 1.3911 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3-2. Trust in the Metaverse | 3.7968 | 1.6297 | 0.511** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 3-3. Blockchain transparency | 4.4360 | 1.3345 | 0.489** | 0.524** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3-4. Metaverse adoption for virtual commerce | 3.2032 | 1.8812 | 0.436** | 0.763** | 0.470** | 1 | ||||||||

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Results

Data were analyzed using PROCESS version 4.2 Macro with 5,000 bootstrap samples.42

Study 1: digital (in)equality, social phobia, and trust in the Metaverse for virtual learning

The third-level digital inequality (educational dimension) was a negative predictor of trust in the Metaverse. People's capacity to translate their digital access and use into offline educational outcomes and resources (digital equality) was a positive predictor of trust in the Metaverse (b = 0.4659, t = 9.0280, p = 0.0000), supporting H1. Trust was a positive predictor of behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning (b = 0.7619, t = 17.5988, p = 0.0000), supporting H2.

There was a significant indirect effect of the third-level digital (in)equality on behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning and education (b = 0.3550, Lower confidence interval [CI] = 0.2677, Upper CI = 0.4539), supporting H3. The direct effect of third-level digital (in)equality on adoption intention in the presence of the mediator (trust) was also found to be significant.

Hence, trust partially mediated the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (educational dimension) and Metaverse adoption intention. Mediation analysis summary for Study 1 is presented in Table 3 (top).

Table 3.

Mediation Analysis Summary (Study 1: Metaverse for Virtual Learning [Top]; Study 2: Metaverse for Virtual Working [Middle]; Study 3: Metaverse for Virtual Commerce [Bottom])

| Relationship | Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | Confidence interval |

Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound (LLCI) | Upper bound (ULCI) | |||||

| Study 1 Digital (In)equality [educational dimension] → trust → metaverse adoption for virtual learning |

0.6434 (p = 0.0000) | 0.2884 (p = 0.0000) | 0.3550 | 0.2677 | 0.4539 | Partial mediation |

| Study 2 Digital (In)equality [labor dimension] → trust → metaverse adoption for virtual working |

0.7175 (p = 0.0000) | 0.2828 (p = 0.0000) | 0.4346 | 0.3446 | 0.5272 | Partial mediation |

| Study 3 Digital (In)equality [economic commerce dimension] → trust → metaverse adoption for virtual commerce |

0.5281 (p = 0.0000) | 0.0829 (p = 0.1370) | 0.4452 | 0.3370 | 0.5526 | Total mediation |

LLCI, lower level confidence interval; ULCI, upper level confidence interval.

Study 1 also tested the moderating role of social phobia on the relationship between digital (in)equality (educational dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning. The analysis revealed a significant moderating effect of social phobia (b = −0.0710, t = −2.5388, p = 0.0116), supporting H4. The results of moderation model testing are summarized in Table 4 (top).

Table 4.

Moderation Analysis Summary (Study 1: Metaverse for Virtual Learning; Study 2: Metaverse for Virtual Working; Study 3: Metaverse for Virtual Commerce)

| Moderation models | Predictors | Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 DV = metaverse adoption for virtual learning |

Intercept | 4.9912 | 0.5287 | 9.4406 | 0.0000 | 3.9510 | 6.0314 |

| IV: Digital (In)Equality | 0.6109 | 0.0561 | 10.8966 | 0.0000 | 0.5006 | 0.7212 | |

| MoV: Social phobia | 0.1119 | 0.0583 | 1.9184 | 0.0560 | −0.0029 | 0.2267 | |

| Interaction Term: Digital (In)Equality × Social Phobia | −0.0710 | 0.0280 | −2.5388 | 0.0116 | −0.1260 | −0.0160 | |

| R2 = 0.3425 | |||||||

| Study 2 DV = metaverse adoption for virtual working |

Intercept | 5.0566 | 0.4542 | 11.1335 | 0.0000 | 4.1630 | 5.9503 |

| IV: Digital (In)Equality | 0.6830 | 0.0540 | 12.6586 | 0.0000 | 0.5768 | 0.7891 | |

| MoV: Neo-Luddism | −0.1051 | 0.0521 | −2.0161 | 0.0446 | −0.2076 | −0.0025 | |

| Interaction Term: Digital (In)Equality × Neo-Luddism | 0.0645 | 0.0259 | 2.4928 | 0.0132 | 0.0136 | 0.1155 | |

| R2 = 0.4912 | |||||||

| Study 3 DV = metaverse adoption for virtual commerce |

Intercept | 5.4380 | 0.4816 | 11.2904 | 0.0000 | 4.4901 | 6.3858 |

| IV: Digital (In)Equality | 0.4120 | 0.0702 | 5.8676 | 0.0000 | 0.2738 | 0.5501 | |

| MoV: Blockchain Transparency | 0.4277 | 0.0722 | 5.9245 | 0.0000 | 0.2856 | 0.5697 | |

| Interaction Term: Digital (In)Equality × Blockchain Transparency | 0.1286 | 0.0343 | 3.7476 | 0.0002 | 0.0611 | 0.1961 | |

| R2 = 0.4609 |

DV, dependent variable; IV, independent variable; MoV, moderating variable; SE, standard error.

The results of slope analysis to further understand the nature of the moderating effects are graphically presented in Figure 4. The line is steeper for low social phobia, which shows that at the low level of social phobia, the impact of digital (in)equality is stronger in comparison to that at the high level of social phobia. Further, as the level of digital equality (educational dimension) increased, the strength of the relationship between social phobia and adoption decreased.

FIG. 4.

Study 1: two-way interaction effect of third-level digital (in)equality and social phobia on Metaverse-based virtual learning.

Study 2: digital (in)equality, neo-Luddism, and trust in the Metaverse for virtual working

The third-level digital inequality (economic labor dimension) was a negative predictor of trust in the Metaverse. People's capacity to translate their digital access and use into offline economic labor outcomes and resources (digital equality) was a positive predictor of trust in the Metaverse (b = 0.6861, t = 14.4060, p = 0.0000), supporting H5. Trust was a positive predictor of behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for remote working (b = 0.6334, t = 12.2015, p = 0.0000), supporting H6.

There was a significant indirect effect of the third-level digital (in)equality (economic labor dimension) on behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for remote working (b = 0.4346, Lower CI = 0.3446, Upper CI = 0.5272), supporting H7. The direct effect of the third-level digital (in)equality on adoption intention in the presence of the mediator (trust) was also found to be significant. Hence, trust partially mediated the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (economic labor dimension) and Metaverse adoption intention (Table 3, middle).

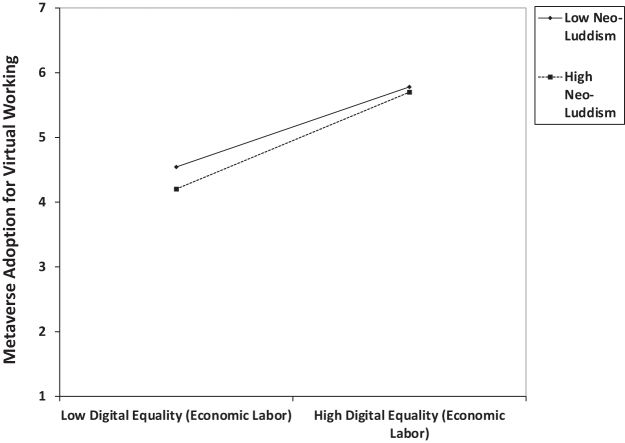

Study 2 also tested the moderating role of neo-Luddism perspectives on the Metaverse in accounting for the relationship between digital (in)equality (economic labor dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for remote working. The results revealed a significant moderating effect of neo-Luddism (b = 0.0645, t = 2.4928, p = 0.0132), supporting H8.

The results of moderation model testing are summarized in Table 4 (middle). The results of slope analysis to further understand the nature of the moderating effects are graphically presented in Figure 5. The line is steeper for high Luddites, which shows that at the high level of neo-Luddism, the impact of digital (in)equality is stronger in comparison to the low level of neo-Luddism. Further, as the level of digital equality increased, the strength of the relationship between neo-Luddism and adoption decreased.

FIG. 5.

Study 2: two-way interaction effect of third-level digital (in)equality and neo-Luddism on Metaverse-based virtual working.

Study 3: digital (in)equality, blockchain transparency, and trust in the Metaverse for virtual commerce

The third-level digital inequality (economic commerce dimension) was a negative predictor of trust in the Metaverse. People's capacity to translate their digital access and use into real-life e-commerce outcomes and resources (digital equality) was a positive predictor of trust in the Metaverse (b = 0.5775, t = 9.8605, p = 0.0000), supporting H9. Trust was a positive predictor of behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce (b = 0.7709, t = 16.3378, p = 0.0000), supporting H10.

The results revealed a significant indirect effect of third-level digital (in)equality (e-commerce dimension) on behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce (b = 0.4452, Lower CI = 0.3370, Upper CI = 0.5526), supporting H11.

The direct effect of third-level digital (in)equality on adoption intention in the presence of the mediator (trust) was not significant. Therefore, trust totally mediated the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equality (economic commerce dimension) and Metaverse adoption intention (Table 3, bottom).

Study 3 also tested the moderating role of blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception on the relationship between digital (in)equality (economic commerce dimension) and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce. The results revealed a significant moderating effect of blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception (b = 0.1286, t = 3.7476, p = 0.0002), supporting H12.

The results of moderation model testing are summarized in Table 4 (bottom). The results of slope analysis to further understand the nature of the moderating effects are graphically shown in Figure 6. The line is steeper for high blockchain transparency, which shows that at the high level of blockchain transparency perception, the impact of digital (in)equality is stronger in comparison to the low level of blockchain transparency perception. Further, as the level of digital equality increased, the strength of the relationship between blockchain transparency perception and adoption increased.

FIG. 6.

Study 3: two-way interaction effect of third-level digital (in)equality and blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency on Metaverse-based virtual commerce.

Discussion

Key findings and theoretical contributions

Departing from the conventional Technology Acceptance Model,40,43 this research attempts to approach the special and emerging issue of the Humane Metaverse from the perspectives of “digital (in)equality and trust.” Empirical findings from the three surveys support the proposed hypotheses about the mediating effects of trust and the moderating effects of social phobia in virtual learning, neo-Luddism in virtual working, and blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency in virtual commerce on the relationship between the third-level digital (in)equalities and Metaverse adoption intention.

For those people with high educational digital equality (low educational digital inequality), social phobia did not have a significant effect on Metaverse adoption intention. People with high educational digital resources are willing to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning regardless of their social phobia level. In contrast, for those with low educational digital equality and resources (high educational digital inequality), high social phobia was associated with higher behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual learning.

People with different levels of social phobia indicate differential levels of adoption intention depending on their capacity to translate their digital access into educational outcomes. The interaction effect between social phobia and digital (in)equality is an interesting finding since it suggests the potential of the Metaverse in inviting people with low educational digital resources and with high social phobia for hybrid learning in the virtual environments that may mitigate social phobia. This finding is relevant to the recent empirical data about highly social phobic consumers' preference for anthropomorphic AI-empowered chatbots.19

For those people with high economic labor-related digital equality (low economic labor digital inequality), neo-Luddism did not have a significant effect on Metaverse adoption intention. People with high economic digital resources are willing to adopt the Metaverse for virtual working regardless of their neo-Luddism level. In contrast, for those with low economic digital equality (high economic digital inequality), high neo-Luddism was associated with even lower behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual working.

This study adds important data about the interaction effects of luddite views on the Metaverse and digital inequality to the literature on neo-Luddism. This finding is relevant to the recent empirical data about the moderating effect of technopian versus Luddite ideological views on consumer behavior.21

For those people with high economic commerce-related digital equality (low e-commerce digital inequality), blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception had stronger effects on Metaverse adoption intention. Most importantly, as the level of digital equality increased (the level of digital inequality decreased), the strength of the relationship between blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception and behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce increased, which implies the importance of blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception especially for those with high digital resources in adopting the Metaverse for virtual commerce.

When the blockchain technology is not perceived to be transparent (low blockchain transparency), even those with high economic commerce-related digital equality showed relatively low intention to adopt the Metaverse for virtual commerce.

Practical, managerial, and policy implications

Practical, managerial, and policy implications of the current findings include: (a) the importance of trust in tackling fears and doubts about the concept of the Metaverse and in increasing people's behavioral intention to adopt the Metaverse; (b) the significance of understanding consumers' personality and individual difference factors in segmenting the emerging market; and (c) policy implications regarding the role of digital inequality in emerging Web 3.0 environments.

Marketing communication and campaigns need to focus on designing messages that help build and increase people's trust in the emerging/evolving platform of the Metaverse. When crafting marketing messages and executing campaigns about the Metaverse, the empirical findings about the moderating effects of social phobia, neo-Luddism, and blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency perception may provide helpful insights for brand managers and social marketers in segmenting/customizing the consumer market based on the key characteristics of consumers relevant to the Metaverse interface for education, working, and commerce.

Increasing trust in the blockchain/cryptocurrency technologies and emphasizing blockchain/cryptocurrency transparency will be (a) the most effective campaign/marketing strategies to attract not only commercial brands44 but also creative artists and digital content generators to enter the NFT market and (b) key to the success of the emerging, decentralized NFT market in the Metaverse.

Most importantly, the current research also highlights the importance of tackling “digital inequality” (“the rich get richer”) in a variety of areas for policy making (education, labor market, and commerce), which policy makers should factor into the AI-based Metaverse/NFT-related legislative process.

Limitations and avenues for future research

Several limitations of this research include: (a) one-time cross-sectional survey without experimental control, which limits the inference of cause-and-effect relationships among the proposed variables; (b) lack of qualitative comments collected from the participants regarding their sentiment about the Metaverse; and (c) data collection in the month of news about mega tech companies' layoffs (Google, Amazon, Meta, and Twitter),45–48 which might have induced the public skepticism about the future of AI-empowered Metaverse and technological innovation.

Follow-up studies may address these limitations by conducting mixed-method research with high-control experiments,49 qualitative ethnographic interviews,23 machine learning/AI neural network/deep learning-based sentiment analysis (opinion mining),50,51 and longitudinal surveys;52 and (d) no measurement of variables such as perceived system usefulness, ease of use, learner self-efficacy, and information quality, which may influence users' adoption of Metaverse for virtual learning.

These variables proposed from the Technology Acceptance Model40,43 are important factors, especially in the context of hybrid educational platforms for virtual learning. Despite these caveats, this research can provide theoretical frameworks to examine people's hopes and fears about the Metaverse and consequential adoption versus non-adoption of the Metaverse for hybrid education, omni-channel virtual commerce, and hybrid remote working.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my gratitude to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their time and insightful comments. I dedicate this article to my father and my inspiration, YounTae Jin, who gave me life and whom I love forever with all my heart.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was partially supported by Northwestern University in Qatar (NU-Q) Professional Development Fund.

References

- 1. Stephenson N. Snow Crash. Bantam Spectra: New York, NY; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smart JM, Cascio J, Paffendorf J. Metaverse Roadmap Overview. 2007. Available from: https://www.w3.org/2008/WebVideo/Annotations/wiki/images/1/19/MetaverseRoadmapOverview.pdf [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 3. Purdy M. How the Metaverse Could Change Work. Harvard Business Review; 2022. Available from: https://hbr.org/2022/04/how-the-metaverse-could-change-work [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 4. Cho J, Tom Dieck MC, Jung T. What Is the Metaverse? Challenges, Opportunities, Definition, and Future Research Directions. In: Extended Reality and Metaverse. (Jung T, Tom Dieck MC, Corriea Loureiro SM. eds.) Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer: Cham, 2002; pp. 3–26; doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-25390-4_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hwang GJ, Chien SY. Definition, roles, and potential research issues of the metaverse in education: An artificial intelligence perspective. Comput Educ Artif Intell 2022;3:10082; doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Riva G, Wiederhold BK. What the metaverse is (really) and why we need to know about it. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2022;25(6):355–359; doi: 10.1089/cyber.2022.0124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Riva G, Villani D, Wiederhold BK. Humane Metaverse: Opportunities and challenges towards the development of a humane-centered Metaverse. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2022;23(6):323–333; doi: 10.1089/cyber.2022.29250.cfp [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiederhold BK. Metaverse games: Game changer for healthcare? Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2022;25(5):267–269; doi: 10.1089/cyber.2022.29246.editorial [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiederhold BK. Ready (or not) player one: Initial musings on the Metaverse. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2022;25(1):1–2; doi: 10.1089/cyber.2021.29234.editorial [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomason J. Metaverse, token economies, and non-communicable diseases. Glob Health J 2022;6:164–167; doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2022.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Di Pietro R, Cresci S. Metaverse: Security and Privacy Issues. The 3rd IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy, and Security in Intelligent Systems and Applications 2022; doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2205.07590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Díaz JEM, Saldaña CAD, Ávila CAR. Virtual world as a resource for hybrid education. Int J Emerg Technol Learn 2020;15(15):94–109; doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i15.13025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. French AM, Risius M, Shim J. The interaction of virtual reality, blockchain, and 5G new radio: Disrupting business and society. Commun Assoc Inform Syst 2020;46:603–618; doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.04625 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barrera KG, Shah D. Marketing in the Metaverse: Conceptual understanding, framework, and research agenda. J Bus Res 2023;155:113420; doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hackl C. Metaverse Commerce: Understanding the New Virtual to Physical and Physical to Virtual Commerce Models. Forbes; 2022. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/cathyhackl/2022/07/05/metaverse-commerce-understanding-the-new-virtual-to-physical-and-physical-to-virtual-commerce-models/?sh=3eac194d5632 [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 16. Girod SJG. The Metaverse Is Much More than a Cool New Channel for Luxury Brands. Forbes; 2023. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/stephanegirod/2023/03/29/the-metaverse-is-much-more-than-a-cool-new-channel-for-luxury-brands/?sh=4cc442946c32 [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 17. Van Deursen A, Helsper E. The third-level digital divide: Who benefits most from being online? Commun Inform Technol Annu 2015;10:29–52; doi: 10.1108/S2050-206020150000010002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carleton RN, Collimore KC, Asmundson GJG, et al. SPINning factors: Factor analytic evaluation of the social phobia inventory in clinical and nonclinical undergraduate samples. J Anxiety Disord 2010;24:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jin SV, Youn S. Why do consumers with social phobia prefer anthropomorphic customer service chatbots? Evolutionary explanations of the moderating roles of social phobia. Telemat Inform 2021;62:101644; doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2021.101644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coulthard D, Keller S. Technophilia, neo-luddism, edependency and judgement of thamus. J Inform Commun Ethics Soc 2012;10:262–272; doi: 10.1108/14779961211285881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Youn S, Jin VS. In AI we trust? The effects of parasocial interaction and technopian versus luddite ideological views on chatbot-based customer relationship management in the emerging feeling economy. Comput Hum Behav 2021;119:106721; doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koroma J, Rongting Z, Muhideen S, et al. Assessing citizens' behavior towards blockchain cryptocurrency adoption in the Mano River Union States: Mediation, moderating role of trust and ethical issues. Technol Soc 2022;68:101885; doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zallio M, Clarkson PJ. Designing the metaverse: A study on inclusion, diversity, equity, accessibility and safety for digital immersive environments. Telemat Inform 2022;75:101909; doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2022.101909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Dijk J. Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics 2006;34(4–5):221–235; doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hargittai E. Second-level digital divide: Differences in people's online skills. First Monday 2002;7(4):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lutz C. Digital inequalities in the age of artificial intelligence and big data. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 2019;1(2):141–148; doi: 10.1002/hbe2.140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lu Y, Ti B, Song X, et al. Can we adapt to highly automated vehicles as passengers? The mediating effect of trust and situational awareness on role adaptation moderated by automated driving style. Transport Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav 2022;90:269–286; doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2022.08.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Amoako GK, Dzogbenuju RK, Jumi DK. Service recovery and loyalty of Uber sharing economy: The mediating effect of trust. Res Transport Bus Manage 2021;41:100647; doi: 10.1016/j.rtbm.2021.100647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zainal NH, Chan WW, Saxena AP, et al. Pilot randomized trial of self-guided virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther 2021;147:103984; doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2021.103984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dechant M, Trimpl S, Wolff C, et al. Potential of virtual reality as a diagnostic tool for social anxiety: A pilot study. Comput Hum Behav 2017;76:128–134; doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim HE, Hong Y-J, Kim M-K, et al. Effectiveness of self-training using the mobile-based virtual reality program in patients with social anxiety disorder. Comput Hum Behav 2017;73:614–619; doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Diederich J. The Psychology of Artificial Superintelligence. Springer Cham: Edinburgh, UK; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kryszczuk MD, Wenzel M. Neo-luddism: Contemporary work and beyond. Przegląd Socjologiczny [Sociol Rev] 2017;66(4):45–65; doi: 10.26485/PS/2017/66.4/3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones SE. Against Technology: From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism. Routledge: New York, NY; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Piwowarska K. Contemporary Neo-Luddism in the Digital Transformation of Employment. In: Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights. 1st ed. (Martín LM, Załucki M, Gonçalves RM, Partyk A. eds.) Dykinson, S.L.: Madrid, Spain; 2021; pp. 354–370. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hughes A, Park A, Kietzmann J, et al. Beyond Bitcoin: What blockchain and distributed ledger technologies mean for firms. Bus Horizons 2019;62(3):273–281; doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2019.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Centobelli P, Cerchione R, Del Vecchio P, et al. Blockchain technology for bridging trust, traceability, and transparency in circular supply chain. Inform Manage 2022;59(7):103508; doi: 10.1016/j.im.2021.103508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chandler J, Rosenzweig C, Moss AJ, et al. Online panels in social science research: Expanding sampling methods beyond Mechanical Turk. Behav Res Methods 2019;51(5):2022–2038; doi: 10.3758/s13428-019-01273-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pan Y, Zinkhan GM. Exploring the impact of online privacy disclosures on consumer trust. J Retail 2006;82(4):331–338; doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2006.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Venkatesh V, Morris GM, Davis BG, et al. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q 2003;27(3):425–478; doi: 10.2307/30036540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, et al. Psychometric properties of the social phobia inventory (SPIN): New self-rating scale. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176(4):379–386; doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. The Guilford Press: New York, NY; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 1989;13(3):319–340; doi: 10.2307/249008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lawrence D. Blockchain Technology and NFTs: How to Have a More Transparent and Trusted Future. Available from: https://www.cryptopolitan.com/blockchain-technology-nfts-trusted-future [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 45. Wall Street Journal. Amazon, Meta, and Twitter: Tech Layoffs by the Numbers. Available from: https://www.wsj.com/story/from-twitter-to-meta-tech-layoffs-by-the-numbers-0afd8714 [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 46. Huang K. A Host of Tech Companies Announce Hiring Freezes and Job Cuts. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/03/technology/tech-companies-hiring-freeze-job-cuts.html [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 47. Corse A, Rodriguez S. Twitter Drafts Broad Job Layoffs in Elon Musk's First Week as Owner. Available from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/twitter-is-drafting-broad-job-cuts-days-after-elon-musks-takeover-11667143301 [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 48. Horwitz J, Rodriguez S. Facebook Parent Meta Is Preparing to Notify Employees of Large-Scale Layoffs This Week. Available from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/meta-is-preparing-to-notify-employees-of-large-scale-layoffs-this-week-11667767794 [Last accessed: October 5, 2023].

- 49. Jaung W. Digital forest recreation in the metaverse: Opportunities and challenges. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2022;185:122090; doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen J, Song N, Su Y, et al. Learning user sentiment orientation in social networks for sentiment analysis. Inform Sci 2022;616:526–538; doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2022.10.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krittanawong C, Isath A, Katz CL, et al. Public perception of metaverse and mental health on Twitter: A sentiment analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2022;76:99–101; doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2022.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huynh-The T, Pham Q-V, Pham X-Q, et al. Artificial intelligence for the metaverse: A survey. Eng Appl Artif Intell 2023;117(A):105581; doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]