Abstract

Florida is one of the HIV epicenters with high incidence and marked sociodemographic disparities. We analyzed a decade of statewide electronic health record/claims data—OneFlorida+—to identify and characterize pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) recipients and newly diagnosed HIV cases in Florida. Refined computable phenotype algorithms were applied and a total of 2186 PrEP recipients and 7305 new HIV diagnoses were identified between January 2013 and April 2021. We examined patients' sociodemographic characteristics, stratified by self-reported sex, along with both frequency-driven and expert-selected descriptions of clinical conditions documented within 12 months before the first PrEP use or HIV diagnosis. PrEP utilization rate increased in both sexes; higher rates were observed among males with sex differences widening in recent years. HIV incidence peaked in 2016 and then decreased with minimal sex differences observed. Clinical characteristics were similar between the PrEP and new HIV diagnosis cohorts, characterized by a low prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and a high prevalence of mental health and substance use conditions. Study limitations include the overrepresentation of Medicaid recipients, with over 96% of female PrEP users on Medicaid, and the inclusion of those engaged in regular health care. Although PrEP uptake increased in Florida, and HIV incidence decreased, sex disparity among PrEP recipients remained. Screening efforts beyond individuals with documented prior STI and high-risk behavior, especially for females, including integration of mental health care with HIV counseling and testing, are crucial to further equalize PrEP access and improve HIV prevention programs.

Keywords: HIV incidence, PrEP, electronic health records, HIV prevention, HIV diagnosis

Introduction

The Federal effort of the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), named Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative: A Plan for America (EHE), aims to reduce HIV incidence by at least 90% by 2030 by focusing on the four pillars of “diagnose, treat, prevent, and respond.”1 Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a critical component of the “prevent” pillar. The use of PrEP as prescribed can reduce the risk of HIV infection from sexual contact by up to 99%2–4 and from injection drug use by at least 74%.5 Improving and prioritizing PrEP uptake among populations who are at high risk of HIV exposure is key to HIV prevention and the EHE initiative.

Florida is one of the US states with the highest rates of HIV incidence6; about 4500 people are newly diagnosed with HIV annually and over 110,000 people are living with HIV in the state.7 Seven Floridian counties with a high prevalence of HIV (Broward, Duval, Hillsborough, Miami-Dade, Orange, and Palm Beach) have been prioritized by the EHE initiative for targeted interventions and preventions.1 In 2021, ∼42,000 PrEP users were identified in Florida, and there were marked disparities in PrEP uptake by sex and race/ethnicity; females compared with males, African American/Black and Hispanic compared with White had high levels of unmet HIV prevention needs.8 Identifying additional factors associated with sociodemographic disparities in HIV incidence and PrEP usage is crucial to improve public health interventions and policies for HIV prevention.

Electronic health records (EHRs) and claims data can be used for disease surveillance, incidence, prevalence estimation,9 and for aiding intervention design, although there can be technical challenges.10 Using EHRs to establish, characterize, and compare real-world cohorts of PrEP recipients and people newly diagnosed with HIV can identify areas of improvement in HIV preventive care. In this analysis, we used EHRs and claims data from a large, statewide clinical research data network, the OneFlorida+, to (1) identify cohorts of PrEP recipients and people newly diagnosed with HIV in care, (2) analyze PrEP use and new HIV diagnoses in terms of temporal trends and sociodemographic factors by sex and geospatial distribution in Florida, and (3) analyze clinical diagnoses documented within the first year before the first PrEP use or HIV diagnosis.

Methods

Data source and ethics statement

The OneFlorida+ Data Trust (OneFL, https://onefloridaconsortium.org/) is a clinical research network funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI, https://www.pcori.org/) and one of the largest clinical data repositories in the US.11,12 OneFL comprises linked EHRs and administrative claims data since 2012 from several health systems in Florida, Alabama, and Georgia, the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration (which oversees Florida Medicaid), and the Florida Department of Health. The current analysis is focused on the Florida portion of the data (between January 2012 and April 2021), which includes longitudinal EHRs/claims data from over 17 million unique individuals (>40% of the state population). The demographic distribution in the Florida segment of OneFL sample is comparable to the Florida census.11 Besides, all the seven Floridian counties prioritized by the EHE include health care providers and clinics participating in OneFL.

The study has been approved by the University of Florida's Institutional Review Board (protocol no. IRB202002581). The OneFL data can be requested at: https://onefloridaconsortium.org/front-door/research-infrastructure-utilization-application/. Authors are available to share computable phenotype codes for reproducibility.

PrEP recipient identification

Building on past algorithms developed and validated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)13–16 to identify people who received Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) as PrEP using claims data, we implemented a computable phenotype [detailed in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2, and Supplementary Tables S1-S3), and expanded to include Tenofovir Alafenamide/Emtricitabine (TAF/FTC)] to identify the cohort of people who received PrEP since 2013 in OneFL. In brief, we identified all patients who received emtricitabine/tenofovir from both prescribing and dispensing records, then excluded HIV treatment, hepatitis B (HBV) treatment, and post-exposure prophylaxis. For all PrEP recipients identified through the algorithm, the time of the first PrEP prescribing/dispensing record was set as the index date and used in the subsequent analyses.

New HIV diagnosis identification

We previously developed and validated a computable phenotype to identify people with confirmed HIV diagnosis from claim-linked EHRs (sensitivity 99% and 98% specificity).17 A total of 71,313 people with HIV were identified with data updated to April 2021. To differentiate new HIV diagnoses from prevalent cases, we identified the date of the first clinical encounter with any HIV diagnostic code or laboratory test suggestive of HIV status, and medication prescriptions for HIV treatment, which we set as the HIV index date. People newly diagnosed with HIV were defined as having at least 1 year of EHRs or 1 year of continuous insurance enrollment and at least three clinical encounters before the HIV index date.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables

Demographic information, including race/ethnicity, self-reported sex, age, and insurance at index date was extracted. All EHRs documented 1 year before the index date were then used to retrieve the diagnosis of the following expert-selected (upon literature review of HIV risk predictors from EHR data18–20 and consensus among coauthors) conditions: sexually transmitted infections (STIs, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, anal warts, herpes, other STIs), mental health (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar, stress reaction/disorder, adjustment disorder), substance use disorder (alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, opioid, sedative, amphetamine, hallucinogen use disorders, and other substance use disorders), and other HIV risk-related factors/procedures (gender dysphoria, high-risk sexual behavior, domestic violence, adult sexual abuse, exposure to HIV/other viral diseases, exposure to other STIs, HIV screening, STI screening, other viral diseases screening, HIV counseling). Although not all these conditions are direct indications of PrEP eligibility, we included them as they are likely to be associated with HIV risk. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 and 10 codes used are listed in Supplement Table S1.

In addition to the expert-selected factors, a frequency-based method was used to extract the most common (top-10) diagnoses documented 12 months before the index date. In detail, all ICD 9 codes were converted to ICD 10 codes using the mapping equivalence developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services,21 and then the ICD 10 codes were aggregated at the three-digit level.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to characterize PrEP recipients and people with new HIV diagnoses in terms of sociodemographic factors; chi-square test was used to assess differences by sex. We plotted the PrEP utilization and HIV incidence rate per year between 2013 and 2020 (data from 2021 were excluded as we do not have data for a full year), stratified by sex. These rates were calculated using the number of PrEP recipients and new HIV diagnoses per year as the numerator, respectively. Two sets of denominators were used: (1) total number of people who had any care visit in OneFL each calendar year (excluding people with a prior HIV diagnosis),9 (2) Florida population size (15 years of age or above).22 The numbers of PrEP recipients and new HIV diagnoses (values used in the numerator) between 2013 and 2020 are reported in Supplement Fig. S2. Additionally, we plotted the geospatial distribution of PrEP recipients and new HIV diagnoses by the first three digits of patients' residential ZIP codes. In doing so, we defined hotspots as any area with values at or above the fourth quartile.

Results

Characteristics of the identified PrEP cohort

A total of 2186 PrEP recipients were identified. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the PrEP cohort: 1020 (48.9%) were females, the mean age at first PrEP prescription was 39.3 years [standard deviation (SD) 13.5], 40.8% were non-Hispanic Black, 22.3% non-Hispanic White, and 19.5% Hispanic. Around 80% were on Medicaid, and 9% were on private insurance. Twenty-eight percent of the people only had one record (i.e., the total number of PrEP prescription and dispensing records) of PrEP, one-third had 2–3 records, one quarter had 4–10 records, and ∼10% had 10+ records. No new HIV infection was observed in our identified PrEP cohort during follow-up times (time until the last visit documented). The median follow-up duration was 358 days after the first PrEP and 150 days after the last PrEP.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Cohort of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Recipients, Overall and by Sex (n = 2186)

| Total (%) | Female (%) | Male (%) | Chi-square p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2186 | 1020 | 1166 | |

| Mean age (age at first PrEP-event) | 39.3 (13.5) | 37.4 (12.1) | 41.0 (14.4) | |

| Age group (age at first PrEP-event) | ||||

| 13–24 | 320 (14.6) | 152 (14.9) | 168 (14.4) | |

| 25–34 | 622 (28.5) | 316 (31.0) | 306 (26.2) | |

| 35–44 | 485 (22.2) | 279 (27.4) | 206 (17.7) | |

| 45–54 | 330 (15.1) | 141 (13.8) | 189 (16.2) | |

| ≥55 | 429 (19.6) | 132 (12.9) | 297 (25.5) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.0029 | |||

| Hispanic | 427 (19.5) | 175 (17.2) | 252 (21.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 892 (40.8) | 523 (51.3) | 369 (31.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 488 (22.3) | 193 (18.9) | 295 (25.3) | |

| Other | 70 (3.2) | 22 (2.2) | 48 (4.1) | |

| Unknown | 309 (14.1) | 107 (10.5) | 202 (17.3) | |

| Data source | 0.8211 | |||

| Both EHR and claim | 710 (32.5) | 420 (41.2) | 290 (24.9) | |

| EHR only | 441 (20.2) | 33 (3.3) | 408 (35.0) | |

| Claim only | 1035 (47.4) | 567 (56.6) | 468 (40.1) | |

| Insurance | <0.0001a | |||

| Medicaid | 1708 (78.1) | 979 (96.0) | 729 (62.5) | |

| Medicare | 30 (0.9) | 7 (0.7) | 13 (1.1) | |

| Other government | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Private | 204 (9.3) | 8 (0.8) | 196 (16.8) | |

| No insurance | 7 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | |

| Other/unknown | 245 (11.2) | 23 (2.3) | 222 (19.0) | |

| Number of PrEP events | <0.0001 | |||

| 1 event | 616 (28.2) | 334 (32.8) | 282 (24.2) | |

| 2–3 events | 776 (35.5) | 367 (36.0) | 409 (35.1) | |

| 4–10 events | 558 (25.5) | 22 (21.8) | 336 (28.8) | |

| 10+ events | 236 (10.8) | 97 (9.5) | 139 (11.9) | |

| Transition to HIV | NA | |||

| No | 2086 (100) | 1020 (100) | 1166 (100) | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Before performing the chi-square test, we combined other government, Medicare, no insurance, and other/unknown in the one class due to small sample size.

EHR, electronic health record; NA, not applicable; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Relative to male PrEP recipients, female recipients were younger (37.4 vs. 41.0 years), more likely to be non-Hispanic Black (51.3% vs. 31.6%), to be on Medicaid (96.0% vs. 62.5%), and to have fewer numbers of PrEP records (32.8% having only 1 record vs. 24.2%).

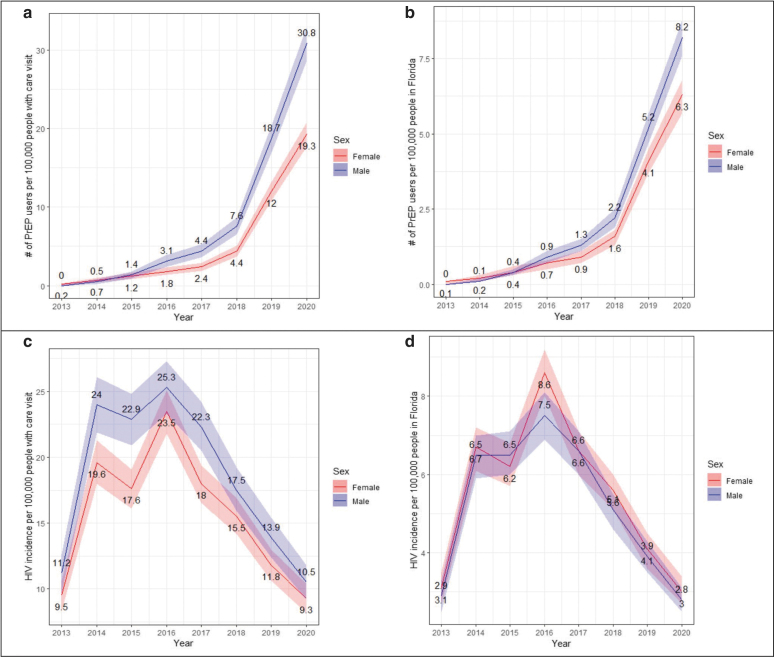

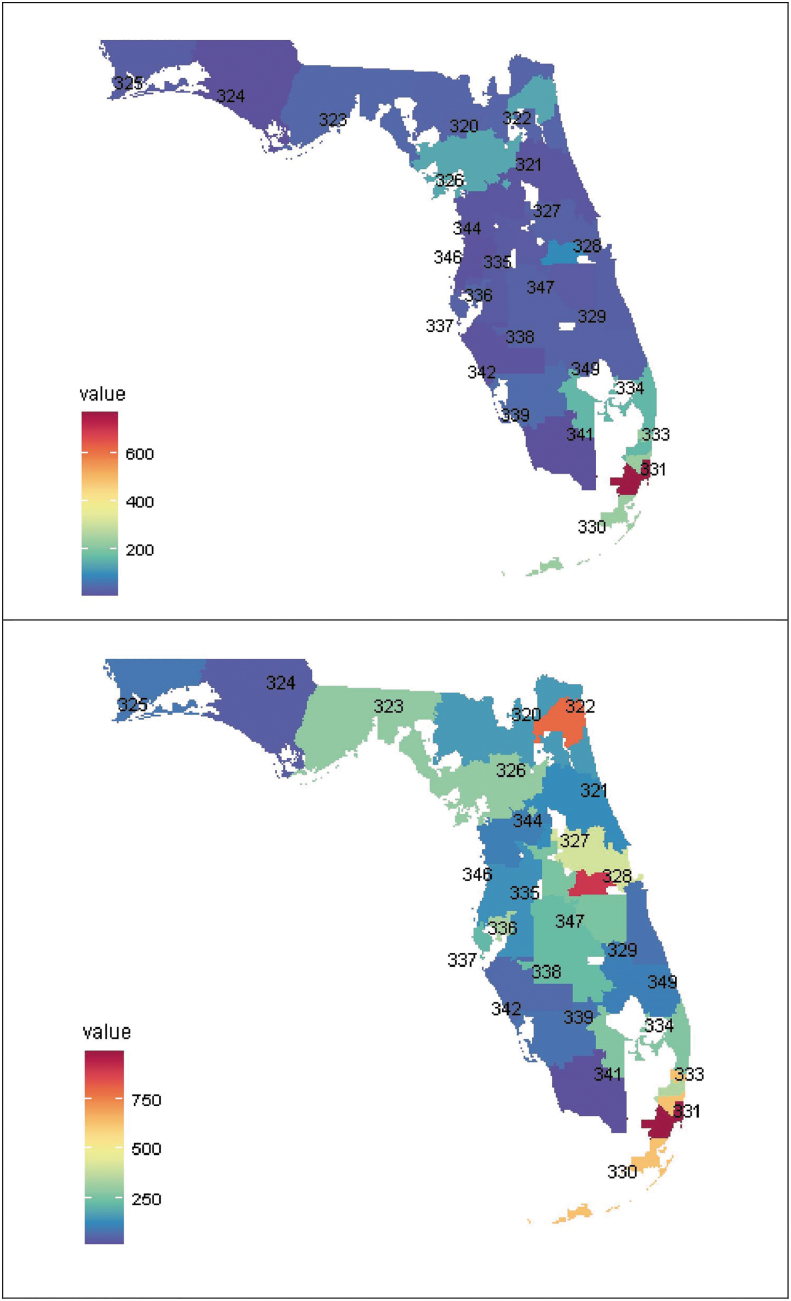

Between 2013 and 2020, the PrEP utilization rate in both females and males increased, but the rate among females lagged behind males with wider gaps in the most recent years (2019 and 2020) (Fig. 1). Only one geospatial hotspot of PrEP users was identified using the first three-digit ZIP code (311, Miami-Dade/Broward areas, Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Trends of HIV PrEP use (top) and new HIV diagnosis (bottom) in Florida between 2013 and 2020, overall and by sex, estimated from the OneFL EHR/claims data. (a) Trend of PrEP utilization rate with total number of people in OneFLwith any care visit as denominator; (b) trend of PrEP utilization rate with Florida population size as denominator; (c) trend of HIV incidence rate with total number of people in OneFLwith any care visit as denominator; and (d) trend of HIV incidence rate with Florida population size as denominator. Colored ribbon indicates 95% confidence interval. EHR, electronic health record; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

FIG. 2.

Geospatial distribution of PrEP recipient (top) and HIV incidence newly identified from OneFL EHR/claims data by the first three-digit ZIP code. EHR, electronic health record; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Characteristics of the identified cohort of people with new HIV diagnosis

A total of 7305 people with new HIV diagnoses were identified. Table 2 shows their characteristics: the mean age was 42.4 years (SD 16.6); 52.7% female, 49.7% non-Hispanic Black, 27.0% non-Hispanic White, and 14.3% Hispanic; 60.7% on Medicaid, 17.5% on Medicare, and 6.5% on private insurance.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Cohort of People Newly Diagnosed with HIV, Overall and by Sex (n = 7305)

| Total n (%) | Female n (%) | Male n (%) | Chi-square p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 7305 | 3851 | 3453 | |

| Mean age (age at new HIV diagnosis, SD) | 42.4 (16.6) | 40.6 (16.7) | 44.3 (16.1) | |

| Age group | <0.0001 | |||

| 13–24 | 1117 (15.3) | 609 (15.8) | 508 (14.7) | |

| 25–34 | 1634 (22.4) | 1033 (26.8) | 601 (17.4) | |

| 35–44 | 1294 (17.7) | 762 (19.8) | 532 (15.4) | |

| 45–54 | 1439 (19.7) | 680 (17.7) | 759 (22.0) | |

| ≥55 | 1821 (24.9) | 767 (19.9) | 1053 (30.5) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.7554 | |||

| Hispanic | 1047 (14.3) | 516 (13.4) | 531 (15.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3631 (49.7) | 2055 (53.4) | 1576 (45.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1970 (27.0) | 941 (24.4) | 1028 (29.8) | |

| Other | 134 (1.8) | 72 (1.8) | 62 (1.8) | |

| Unknown | 523 (7.2) | 267 (6.9) | 256 (7.4) | |

| Data source | 0.1689 | |||

| Both EHR and claim | 2754 (37.7) | 1569 (40.7) | 1185 (34.3) | |

| EHR only | 1607 (22.0) | 561 (14.6) | 1045 (30.3) | |

| Claim only | 2944 (40.3) | 1721 (44.7) | 1223 (35.4) | |

| Insurance | <0.0001a | |||

| Medicaid | 4431 (60.7) | 2758 (71.6) | 1673 (48.5) | |

| Medicare | 1281 (17.5) | 537 (13.9) | 744 (21.6) | |

| Other government | 20 (0.3) | 10 (0.3) | 10 (0.3) | |

| Private | 475 (6.5) | 176 (4.6) | 299 (8.7) | |

| No insurance | 176 (2.4) | 47 (1.2) | 129 (3.7) | |

| Other/unknown | 922 (12.6) | 323 (8.4) | 598 (17.3) |

Before performing the chi-square test, we combined other government, Medicare, no insurance, and other/unknown in the one class due to small sample size.

EHR, electronic health record; SD, standard deviation.

Compared with males, females with new HIV diagnoses were younger (40.6 vs. 44.3 years), more likely to be non-Hispanic Black (53.4% vs. 45.6%), and to be on Medicaid (71.6% vs. 48.5%). An increasing trend in HIV incidence rate was observed between 2013 and 2016, and decreasing trend was observed after 2016. Minimal sex differences were observed in new incidence trends (Fig. 1). Three geospatial hotspots of HIV incidence were identified: areas where zip codes start with 311 in Miami-Dade/Broward areas, 328 in Orange areas, and 322 in Duval areas (Fig. 2).

Clinical conditions associated with HIV risk, and other high-frequency conditions

Table 3 summarizes the frequencies of the expert-selected health conditions among the two cohorts. Having a diagnosis of STI 1 year before the index date was rare among both cohorts (e.g., 1.4% of PrEP recipients and 1.2% of people with a new HIV diagnosis had a prior chlamydia diagnosis). A high prevalence of mental health conditions was observed in both cohorts. A similar prevalence of substance use disorders was observed in both cohorts, except cocaine use disorder, which was higher in the PrEP cohort (11.2% vs. 6.8%). High-risk sexual behavior (12.2% vs. 1.6%), exposure to HIV or other viral diseases (15.9% vs.1.2%), and exposure to other STIs (21.5% vs. 4.2%) had a higher prevalence in the PrEP cohort relative to the new HIV diagnosis cohort.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Expert-Selected Conditions Associated with HIV Risk in Florida Among Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Users or People Newly Diagnosed with HIV in Florida, Documented Within 1 Year from the First PrEP Prescription or HIV Diagnosis, Estimated Using OneFL Electronic Health Record/Claims Data (2012–2020)

| PrEP recipients, n = 2186 (%) | People newly diagnosed with HIV, n = 7305 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| STIs | ||

| Chlamydia | 30 (1.4%) | 89 (1.2%) |

| Gonorrhea | 25 (1.1%) | 52 (0.7%) |

| Syphilis | 39 (1.8%) | 86 (1.2%) |

| Anal warts | 14 (0.6%) | 54 (0.7%) |

| Herpes | 16 (0.7%) | 129 (1.8%) |

| Other STIs | 103 (4.7%) | 215 (2.9%) |

| Psychiatric conditions | ||

| Depression | 632 (28.9%) | 1511 (20.7%) |

| Anxiety | 544 (24.9%) | 1438 (19.7%) |

| PTSD | 110 (5.0%) | 258 (3.5%) |

| ADHD | 102 (4.7%) | 165 (2.3%) |

| Bipolar | 413 (18.9%) | 1034 (14.2%) |

| Stress reaction/disorder | 27 (1.2%) | 59 (0.8%) |

| Adjustment disorder | 76 (3.5%) | 189 (2.6%) |

| Substance use disorder | ||

| Alcohol use disorder | 256 (11.7%) | 760 (10.4%) |

| Cannabis use disorder | 213 (9.4%) | 577 (7.9%) |

| Cocaine use disorder | 245 (11.2%) | 496 (6.8%) |

| Opioid use disorder | 140 (6.4%) | 493 (6.8%) |

| Sedative use disorder | 38 (1.7%) | 137 (1.9%) |

| Amphetamine use disorder | 65 (3.0%) | 137 (1.9%) |

| Hallucinogen use disorder | 11 (0.5%) | 17 (0.2%) |

| Other substance use disorder | 205 (9.4%) | 643 (8.8%) |

| Other diagnoses | ||

| Gender disphoria | 22 (1.0%) | 20 (0.3%) |

| High-risk sexual behavior | 267 (12.2%) | 118 (1.6%) |

| Adult sexual abuse | 34 (1.6%) | 20 (0.3%) |

| Domestic violence | 2 (0.1%) | 9 (0.1%) |

| Exposure to HIV or other viral disease | 347 (15.9%) | 85 (1.2%) |

| Exposure to other STIs | 470 (21.5%) | 304 (4.2%) |

| HIV screening | 170 (7.8%) | 113 (1.6%) |

| STI screening | 181 (8.3%) | 232 (3.2%) |

| other viral diseases screening | 149 (6.8%) | 114 (1.6%) |

| HIV counseling | 34 (1.6%) | 27 (0.4%) |

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

Among the top 10 most common conditions present within 12 months from the index date derived from all diagnostic codes in each cohort, hypertension (36.1% before first PrEP and 34.6% before HIV diagnosis), nicotine dependence (31.9% and 28.6%), abdominal and pelvic pain (28.4% and 33.3%), and long-term drug therapy (30.1% and 26.8%) were documented in both cohorts. Pain in the throat and chest (26.8%), soft tissue disorders (23.5%), and abnormalities of breathing (21.8%) were among the top 10 conditions in the new HIV diagnosis cohort, but not in the PrEP cohort. All conditions and frequencies for each cohort are listed in Supplement Table S2.

Discussion

This study identified two cohorts of people who received PrEP and who were newly diagnosed with HIV in Florida over 2012–2020 using EHR and claims data from a large multisite research consortium, OneFL. The overall trends of new HIV diagnoses identified in our sample were consistent with state estimates: a slight increase in HIV incidence rate between 2013 and 2016, and then a gradual decrease afterward.7 The increasing trends of PrEP utilization that we identified are consistent with the estimates from AIDSVu, which used a national pharmacy retail dataset.8,23 The recent reductions in HIV incidence rates and increase in PrEP users may indicate the success of integrated and targeted HIV prevention efforts in Florida24 that include increased PrEP uptake in Florida. A large increase in HIV incidence rate was observed in our sample from 2013 to 2014; this was not reflected in the Florida state estimate.

We are likely to have a higher proportion of underidentification of incident HIV cases in 2013 compared with other years as our data source includes EHRs starting from 2012, and some people newly diagnosed with HIV in 2013 may have been excluded due to the lack of documentation from at least three previous clinical encounters, which was one of the criteria used in our algorithm. Additionally, the HIV incidence rate calculated using the total number of patients receiving care services from OneFL as the denominator was closer to the Florida state estimate7 than the rate calculated with Florida population size as the denominator. Not all individuals in Florida receive HIV prevention and care from health systems in OneFL, and the health care penetration rate may vary by location. By using the total number of patients receiving any health care service within the system, we can partially account for the differential health care penetration rate and achieve a closer approximation to the state incidence estimation.

The age composition of our identified PrEP and new HIV diagnosis cohorts are both consistent with the Florida state estimates.8 The race/ethnicity composition in our new HIV diagnosis cohort was also consistent with the state estimates. However, we observed higher proportions of non-Hispanic Black PrEP recipients than the state data.8 Furthermore, AIDSVu and Florida state estimates indicate that 16% of PrEP recipients8 and 20% of HIV incidence were females.7 Our sample in OneFL found much higher proportions: 48.9% of PrEP recipients and 52.7% of HIV incidence were females. Several factors may contribute to these high proportions. Females are overrepresented in our data source. We have also found higher HIV prevalence among females with OneFL data in our previous study17; 42% of all HIV diagnoses were among females, while around 27% of HIV cases were among females in Florida.8 This is likely due to the fact that females are more likely to seek health care than males.25 Moreover, our PrEP cohort may be biased toward Medicaid beneficiaries as 96% of identified female PrEP recipients were on Medicaid.

If we only include people from OneFl who had EHR data, the proportion of female PrEP users would drop to 7.5% (data not shown), which is closer to the estimation from AIDSVu.8 HIV prevention efforts during and after pregnancy, when many women became Medicaid eligible, might contribute to the high proportion of females on PrEP in our sample.

While the proportion of female PrEP recipients was high in the study sample, one-third of them did not have an observed medication refill (i.e., having only one PrEP event); this proportion was higher than the 24.2% observed in males. Lower perceived risks among females may contribute to PrEP discontinuation.26 One encouraging finding was that none of the PrEP recipients was recorded as having HIV after they received PrEP, indicating the high effectiveness of PrEP in preventing HIV transmission.

Three geospatial hotspots of high HIV incidence rates were identified, roughly corresponding to the Duval, Orange, Miami-Dade/Broward counties prioritized by the EHE initiative.1 Only one hotspot of high PrEP utilization rate was identified in Miami-Dade/Broward areas, indicating potential underutilization of PrEP in some EHE counties. Hillsborough and Pinellas counties also have high burdens of HIV and are prioritized by the EHE, but we did not identify these areas as hotspots.

Examining the diagnoses documented before the first PrEP and new HIV diagnosis can shed light on the clinical and care pathways patients take before being diagnosed with HIV and starting PrEP. People with STI diagnosis are at increased risk of HIV infections and are candidates for PrEP.27–29 However, our analysis revealed a significantly lower prevalence of major STI diagnoses (<2%) compared with previous studies (24–35%), which primarily involve male PrEP users or men who have sex with men.30–32 This low prevalence indicates that a sole focus on individuals with documented STI diagnoses in HIV prevention efforts might miss a substantial portion of those who could benefit from PrEP.

Lastly, a high prevalence of psychiatric conditions and substance use disorder has been observed among both cohorts before receiving PrEP and HIV diagnosis, respectively. Addressing mental health and substance use disorders is critical for reducing HIV transmission, as these comorbidities can increase the risk of engaging in behaviors that lead to HIV acquisition33–35 and may interfere with adherence to PrEP.36 Our results highlight the need for the integration of mental health services into HIV prevention and care.37–39 Although we did not perform direct statistical comparisons for the prevalence of various diagnoses between the two cohorts, we observed a slightly higher prevalence of almost all diagnoses among the PrEP cohort compared with the new HIV cohort. This may suggest that the PrEP cohort may have better access to health care, including screening, counseling, and intervention. It may also suggest that providers were unaware of the patient's HIV risk (e.g., high-risk sexual behavior) and PrEP eligibility before HIV diagnosis.

Our results shall be interpreted in light of some limitations. Our algorithm used to identify PrEP recipients and new HIV diagnoses has not been validated against medical chart review. Both PrEP and new HIV diagnosis algorithms require 1 year of prior continuous insurance enrollment or 1 year of medical records as inclusion criteria. This increases the information available to differentiate PrEP and HIV treatment and new vs. prevalent HIV cases. However, as a result, our sample comprised individuals engaged in care. People who lack health insurance and people with fewer medical records or only sporadic interaction with the health care system may be underrepresented in our sample, whereas people on Medicaid may be overrepresented due to the inclusion of Medicaid claims data in OneFl.. Additionally, as a consequence, the number of PrEP recipients and new HIV diagnoses may be subject to underestimation. Furthermore, when examining clinical characteristics before the index date, only ICD diagnosis codes were considered. The prevalence of some of the conditions was underestimated as we did not incorporate information from laboratory test results (e.g., positive laboratories from an STI condition) and medications.

Finally, our EHR data extraction period covers the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted the health care system's capacity for testing and patient access to HIV and STI prevention services and care.40 This could affect data from early 2020 to 2021, potentially resulting in underestimation of HIV risk due to the lack of HIV testing.

By analyzing real-world cohorts of PrEP recipients and people newly diagnosed with HIV identified from a statewide EHR clinical research data network, we identified gaps in HIV preventive services in Florida by sex, geo-locations, and clinical characteristics. The low STI diagnosis and high prevalence of mental health conditions identified among both PrEP and HIV incidence cohorts underscore the limitation of relying solely on STI/HIV clinics or focusing only on patients with documented STI diagnoses for HIV prevention efforts. To address this, it is critical to offer HIV risk assessment, HIV testing, and access to PrEP at non-STI/HIV clinics, including primary care, community health care, and behavioral and mental health care settings. Future research could develop novel strategies, such as a clinical decision support tool, to support this integration and better help providers in different health care settings offer effective HIV prevention services.

Supplementary Material

Authors' Contributions

Y.L.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing—original draft preparation. K.A.S.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, and funding acquisition. H.C.: writing—original draft. H.P.: writing—review and editing. M.P.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, and supervision. R.L.C.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and supervision.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by a pilot fund from the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute UL1TR001427-PRO00039875 (PI: K.A.S.), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) under award no. R01AI145552 (Salemi, Prosperi MPIs) and R01AI172875 (Prosperi, Bian MPIs). The OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium was funded by the PCORI numbers CDRN-1501-26692 and RI-CRN-2020-005; in part by the OneFlorida Cancer Control Alliance, funded by the Florida Department of Health's James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program no. 4KB16.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, et al. Ending the HIV epidemic: A plan for the United States. JAMA 2019;321(9):844–845; doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Nguyen DP, et al. Redefining human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) preexposure prophylaxis failures. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65(10):1768–1769; doi: 10.1093/cid/cix593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(10):1601–1603; doi: 10.1093/cid/civ778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2016;387(10013):53–60; doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381(9883):2083–2090; doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019. HIV Surv Suppl Rep 2020;26(1). [Google Scholar]

- 7. FLHealthCHARTS. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Diagnoses. flhealthcharts.gov. 2023. Available from: https://www.flhealthcharts.gov/ChartsDashboards/rdPage.aspx rdReport = HIVAIDS.Dataviewer&rdRequestForwarding = Form [Last accessed: May 10, 2023].

- 8. AIDSVu. Local Data: Florida. 2021. Available from: https://aidsvu.org/local-data/united-states/south/florida/ [Last accessed: May 4, 2021].

- 9. Bagley SC, Altman RB. Computing disease incidence, prevalence and comorbidity from electronic medical records. J Biomed Inform 2016;63:108–111; doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aliabadi A, Sheikhtaheri A, Ansari H. Electronic health record-based disease surveillance systems: A systematic literature review on challenges and solutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27(12):1977–1986; doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hogan WR, Shenkman EA, Robinson T, et al. The OneFlorida Data Trust: A centralized, translational research data infrastructure of statewide scope. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2022;29(4):686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shenkman E, Hurt M, Hogan W, et al. OneFlorida clinical research consortium: Linking a clinical and translational science institute with a community-based distributive medical education model. Acad Med 2018;93(3):451–455; doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, et al. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(41):1147–1150; doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang YA, Tao G, Samandari T, et al. Laboratory testing of a cohort of commercially insured users of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in the United States, 2011-2015. J Infect Dis 2018;217(4):617–621; doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang YA, Tao G, Smith DK, et al. Persistence with human immunodeficiency virus pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States, 2012-2017. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(3):379–385; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Furukawa NW, Smith DK, Gonzalez CJ, et al. Evaluation of algorithms used for PrEP surveillance using a reference population from New York City, July 2016-June 2018. Public Health Rep 2020;135(2):202–210; doi: 10.1177/0033354920904085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Y, Siddiqi KA, Cook RL, et al. Optimizing identification of people living with HIV from electronic medical records: Computable phenotype development and validation. Methods Inf Med 2021;60(3–04):84–94; doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1735619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Krakower DS, et al. Use of electronic health record data and machine learning to identify candidates for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: A modelling study. Lancet HIV 2019;6(10):e688–e695; doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30137-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krakower DS, Gruber S, Hsu K, et al. Development and validation of an automated HIV prediction algorithm to identify candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis: A modelling study. Lancet HIV 2019;6(10):e696–e704; doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30139-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burns CM, Pung L, Witt D, et al. Development of a human immunodeficiency virus risk prediction model using electronic health record data from an academic health system in the Southern United States. Clin Infect Dis 2023;76(2):299–306; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Bureau of Economic Research. ICD-9-CM to and from ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS Crosswalk or General Equivalence Mappings. 2023. Available from: https://www.nber.org/research/data/icd-9-cm-and-icd-10-cm-and-icd-10-pcs-crosswalk-or-general-equivalence-mappings [Last accessed: February 27, 2023].

- 22. FLHealthCHARTS. Population Query System—FL Health CHARTS—Florida Department of Health. 2023. Available from: https://www.flhealthcharts.gov/FLQUERY_New/Population/Count# [Last accessed: May 10, 2023].

- 23. Sullivan PS, Mouhanna F, Mera R, et al. Methods for county-level estimation of pre-exposure prophylaxis coverage and application to the U.S. Ending the HIV Epidemic jurisdictions. Ann Epidemiol 2020;44:16–30; doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Florida Department of Health. State of Florida Integrated HIV Prevention and Care Plan 2017–2021; 2016. Available from: https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/prevention/documents/State-of-Florida-Integrated-HIV-Prevention-and-Care-Plan-09-29-16_FINAL-Combined.pdf [Last accessed: May 10, 2023].

- 25. Thompson AE, Anisimowicz Y, Miedema B, et al. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: A QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:38; doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burns JA, Hull SJ, Inuwa A, et al. Understanding retention in the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis cascade among cisgender women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2023;37(4):205–211; doi: 10.1089/apc.2023.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peterman TA, Newman DR, Maddox L, et al. High risk for HIV following syphilis diagnosis among men in Florida, 2000-2011. Public Health Rep 2014;129(2):164–169; doi: 10.1177/003335491412900210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castro JG, Alcaide ML. High rates of STIs in HIV-infected patients attending an STI clinic. South Med J 2016;109(1):1–4; doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peterman TA, Newman DR, Maddox L, et al. Risk for HIV following a diagnosis of syphilis, gonorrhoea or chlamydia: 328,456 women in Florida, 2000–2011. Int J STD AIDS 2015;26(2):113–119; doi: 10.1177/0956462414531243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McLean J, Bartram L, Zucker J, et al. Back2PrEP: Rates of bacterial sexually transmitted infection diagnosis among individuals returning to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care: A retrospective review of a New York City comprehensive HIV prevention program. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2022;36(12):458–461; doi: 10.1089/apc.2022.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coyer L, Prins M, Davidovich U, et al. Trends in sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections after initiating human immunodeficiency virus pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men from Amsterdam, the Netherlands: A longitudinal exposure-matched study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2022;36(6):208–218; doi: 10.1089/apc.2021.0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simmons K, Fitzpatrick C, Richardson D. Sexually transmitted infection testing and prevalence among MSM using event-based dosing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Sex Health 2023;20(2):177–179; doi: 10.1071/SH22192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vosburgh HW, Mansergh G, Sullivan PS, et al. A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2012;16(6):1394–1410; doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Scivoletto S, Tsuji RK, Abdo C, et al. Use of psychoactive substances and sexual risk behavior in adolescents. Subst Use Misuse 2002;37(3):381–398; doi: 10.1081/ja-120002484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bishop TM, Maisto SA, Spinola S. Cocaine use and sexual risk among individuals with severe mental illness. J Dual Diagn 2016;12(3–4):205–217; doi: 10.1080/15504263.2016.1253903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gebru NM, Canidate SS, Liu Y, et al. Substance use and adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in studies enrolling men who have sex with men and transgender women: A systematic review. AIDS Behav 2022; doi: 10.1007/s10461-022-03948-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Remien RH, Patel V, Chibanda D, et al. Integrating mental health into HIV prevention and care: A call to action. J Int AIDS Soc 2021;24(Suppl 2):e25748; doi: 10.1002/jia2.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Operario D, Sun S, Bermudez AN, et al. Integrating HIV and mental health interventions to address a global syndemic among men who have sex with men. Lancet HIV 2022;9(8):e574–e584; doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Camp DM, Moore SJ, Wood-Palmer D, et al. Preferences of young black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men regarding integration of HIV and mental health care services. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2022;36(9):356–363; doi: 10.1089/apc.2022.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanne JH. Covid-19: Sexually transmitted diseases surged in US during pandemic. BMJ 2022;377;o1275; doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.