Abstract

Agnogenic practices—designed to create ignorance or doubt—are well-established strategies employed by health-harming industries (HHI). However, little is known about their use by industry-funded organizations delivering youth education programmes. We applied a previously published framework of corporate agnogenic practices to analyse how these organizations used them in three UK gambling industry-funded youth education programmes. Evidential strategies adopted previously by other HHI are prominent in the programmes’ practitioner-facing materials, evaluation design and reporting and in public statements about the programmes. We show how agnogenic practices are employed to portray these youth education programmes as ‘evidence-based’ and ‘evaluation-led’. These practices distort the already limited evidence on these educational initiatives while legitimizing industry-favourable policies, which prioritize commercial interests over public health. Given the similarities in political strategies adopted by different industries, these findings are relevant to research and policy on other HHI.

Keywords: children, evidence, health policy, agnogenic practices, commercial determinants of health

Contribution to Health Promotion.

We identify how industry-funded youth gambling education programmes are presented by the organizations delivering them as effective, evidence-based and evaluation-led measures to prevent gambling harm in ways that are not supported by the international evidence.

To ensure youth education prioritizes the health and best interests of children over commercial interests, youth education programmes need to be regulated and evaluated completely independent of industry and the limits of the evidence base acknowledged.

Our findings can help strengthen the governance of health education and its evaluation including the establishment of mechanisms to ensure independence from industry funding and prevent conflicts of interest.

INTRODUCTION

An emerging body of literature has begun to document the strategies employed by health-harming industries (HHI) to misrepresent and misuse evidence as part of wider strategies to promote their favoured policy agendas (Gilmore et al., 2023; Ulucanlar et al., 2023). Drawing on Robert Proctor’s concept of agnotology (Proctor and Schiebinger, 2008), such activities have been termed ‘corporate agnogenic practices’ (Fooks et al., 2019). They encompass a range of strategies to create and maintain doubt or ignorance about the harms associated with certain products and business practices, and the effectiveness of measures to address them (Fooks et al., 2019). Their effect is to distort public and policymakers’ perceptions of the overall body of policy-relevant evidence.

Despite the growing literature on corporate strategies, many sectors, such as the gambling industry, and their practices remain under-researched, despite growing evidence of gambling harms, including among children and young people (Riley et al., 2021; Marionneau et al., 2023). More specifically, there is limited evidence documenting the agnogenic practices of the gambling industry (Ulucanlar et al., 2023). Further attention needs to be paid to the promotion of youth education initiatives funded by gambling and other HHIs, and their effectiveness in reducing youth harms. In particular, greater attention must be paid to their use within industry corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies to promote gambling companies as socially responsible actors and, with this, to lobby for commercially supportive policy regimes (Ulucanlar et al. 2023). This study seeks to address this gap in understanding by analysing the agnogenic practices underpinning gambling industry-funded youth education programmes.

The lack of research on gambling industry-funded youth education initiatives is of particular concern given, firstly, the paucity of effective regulatory measures in place to protect children from gambling harm in many contexts, including the UK (Clark et al., 2020), and secondly, the claim of the leading UK gambling industry trade association, the Betting and Gaming Council (BGC), and other industry-funded organizations that their education programmes help to ‘safeguard’ children and young people from gambling harm. These programmes are promoted as evidence-based and evaluation-led. However, these assertions are in conflict with the international literature which provides limited robust evidence in support of the effectiveness of youth gambling education (Blank et al., 2021). This analysis therefore aims to examine whether, and if so how, previously documented corporate agnogenic practices are used to portray three UK-based gambling industry-funded youth education programmes as effective forms of harm prevention.

ANALYTICAL APPROACH

This qualitative analysis examines the social and political practices that reproduce certain understandings of youth gambling education as an effective, evidence-based way to safeguard children and young people from gambling harms. We understand corporate agnogenic practices to be social and political practices that construct a particular understanding of a body of evidence and legitimize industry-favourable policy measures. The field of ignorance studies rejects the idea that ignorance is simply the absence of knowledge or being misinformed (Gross and McGoey, 2022). Instead, ignorance is to be understood as being intimately interwoven with knowledge. Gross and McGoey (2022) propose that ‘ignorance needs to be understood and theorized as a regular feature of decision-making in general, in social interactions and in everyday communication’. This more dynamic and nuanced understanding of ignorance seeks to capture how and why certain ways of knowing come to be privileged over others, what remains unknown and why, and the strategic value to individuals and organizations of cultivating ignorance through evidential and other practices.

Data sources: youth gambling education programmes

A detailed account of the content and provenance of the programmes examined here can be found in a previous publication (van Schalkwyk et al., 2022). Here, we focus on the evidential practices used in (i) supporting documents supplied to teachers/practitioners, (ii) programme evaluation reports and (iii) public statements made about these programmes by their parent organizations.

Two of the three programmes included in the analysis are funded by GambleAware, an industry-funded charity that functions as a commissioning and grant-making body and is the main distributor of industry donations obtained under a voluntary agreement for funding and delivery of gambling research, education and treatment in the UK (GambleAware, n.d.). The first programme was developed through a partnership between GambleAware and the PSHE Association, a membership body and charity that supports the delivery of personal, social, health, and economic (PSHE) education (PSHE Association, n.d.). This partnership led to the production of a teacher’s handbook and teaching resources with background materials (Table 1). A ‘theory and evidence scope’ (referred to as the ‘commissioned literature review’ hereafter) was also produced from this partnership. These documents were included in the dataset.

Table 1:

Details of youth gambling education programme documents included in the analysis

| Programme lead organization(s) | Intended audience | Teaching/practitioner-facing resources and materials included in the analysis | Identified agnogenic practices and associated techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| GambleAware and PSHE | Teachers of school years 3–11 | Four documents: Theory and evidence scopea Teacher handbook title How to Address Gambling Through PSHE Education Teacher handbook on how to address gambling through PSHE education Exploring risk in relation to gambling (KS2 lesson pack): Lesson pack—Exploring risk in relation to gambling Promoting resilience to gambling (KS4 lesson pack): Gambling, A Teaching Resource to Promote Resilience |

Misleading summaries: Omission of important qualifying information, Illicit generalization Evidential landscaping: Observational selection/cherry picking, Strategic ignorance, the ‘Hens’ teeth’ technique |

| GambleAware and Fast Forward | Anyone who works with young people ages 11–25 years and families | One document: Gambling education toolkit (2021 version) with general background information and lesson plans and resources on 6 topics:

|

Confounding referencing: Cryptic references, Out-of-place citation, Inaccessible source Misleading summaries: False attribution of focus, Omission of important qualifying information, the ‘tweezers method’, Illicit generalization Evidential landscaping: Observational selection/cherry picking, Strategic ignorance |

| YGAM | Teachers and other professionals who work with children and young people, years 3–16+ | 35 documents: Workshop and teaching resources with lesson plans based on 6 topics:

Specific resources for different stages and formats based on these topics are provided: Years 3–11, KS2-5, 13+, 16+, NCS, drop-down days |

See text for findings in relation to the YGAM materials. |

aReferred to as ‘commissioned literature review’ in the main text.

A second programme forms part of GambleAware’s youth education activities and is delivered by Fast Forward, a Scottish-based voluntary organization that ‘provides high-quality health education, prevention and early-intervention programmes’ (Fast Forward, n.d.-b). Fast Forward delivers the Scottish Gambling Education Hub, a prevention and education programme based on seven activities, including training sessions and peer-based theatre performances (Fast Forward, n.d.-a). One of the main outputs of the programme is a gambling education toolkit, and the 2021 version was included in the dataset (Table 1).

The dataset included resources from a third youth education programme delivered by an industry-funded charity, the Young Gamers and Gamblers Education Trust (YGAM). The charity delivers several programmes, with one main output being the industry-funded Young People’s Gambling Harm Prevention Programme. The BGC awarded a grant of £10 million in total to YGAM and another gambling charity, GamCare, to deliver what the BGC described as an ‘independent gambling education initiative’ (Betting and Gaming Council, 2020). This funding enabled YGAM to expand their education programme, which includes ‘train the trainer’ workshops and teaching resources (Table 1).

Data collection and analysis

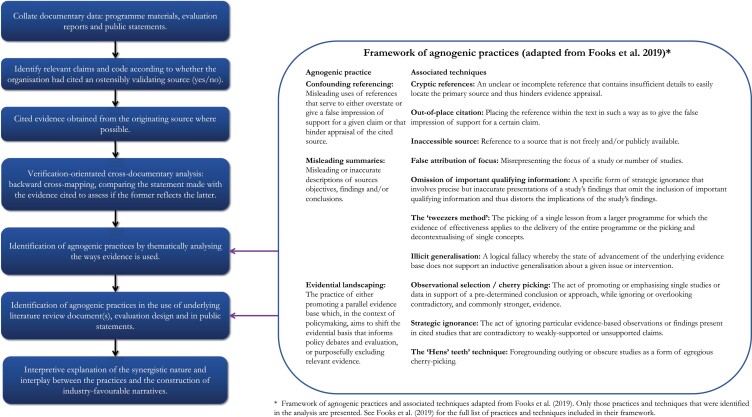

Documents relating to each of the programmes, including evaluation reports, were accessed via each organization’s website between October 2020 and May 2022, as were webpages, press releases and written submissions to relevant government consultations proactively published by the included organizations (with the latter being cross-checked against the corresponding government website). Our analytical approach was informed by previous studies of corporate agnogenic practices (Ulucanlar et al., 2014; Fooks et al., 2019; Lauber et al., 2021). As described in more detail below, this involved thematic analysis of the ways evidence and evaluations had been used to identify if and how agnogenic practices have been adopted and to examine how their use structured narratives about the evidence base and effectiveness of the programmes. Figure 1 provides an overview of the analytical approach including the framework of agnogenic practices used to thematically code the data.

Fig. 1:

Analytical approach to the identification and examination of agnogenic practices in gambling industry-funded youth education programmes.

Identification of agnogenic practices

To study the ways evidence was used, the first stage of analysis involved identifying relevant claims within the programme materials. For the purposes of the study, relevant claims were defined as statements describing anticipated impacts and effectiveness of (i) PSHE education, (ii) youth gambling education, (iii) a specific gambling youth education programme or (iv) a specific lesson plan (e.g. ‘PSHE (personal, social, health and economic) education is the school curriculum subject which prepares young people for life and work in a rapidly changing world, helping to keep pupils safe and healthy while boosting their life chances and supporting their academic attainment’ or ‘There is a growing body of evidence on how to deliver effective educational inputs to prevent gambling harm in young people’). Statements about what a given lesson will encourage or allow a class or student to do during the lesson (e.g. ‘this lesson will involve drawing a mind map’) were not included. Claims were collated in an Excel spreadsheet and coded according to whether the organization had cited an ostensibly validating source (yes/no).

When possible, the evidence cited to substantiate the relevant claims was obtained from the originating source, for example the underlying study that had been cited to back up a claim. We then performed a verification-orientated cross-documentary analysis to assess how evidence had been used and represented (Ulucanlar et al., 2014; Fooks et al., 2019; Lauber et al., 2021). This involved backward cross-mapping, comparing the statement made with the evidence cited to assess if the former reflected the latter. If the supporting source (the ‘primary’ source) was identified as not being the source of this cited evidence, the same backward cross-mapping approach was applied to attempt to find the underlying or ‘secondary’ source (Fooks et al., 2019). The ways evidence had been used were then analysed thematically using a framework of agnogenic practices developed by Fooks et al. (2019) which is comprised of four agnogenic practices and 23 related techniques. M.v.S. performed the primary verification-orientated cross-documentary analysis. N.M. double-coded all claims and agnogenic practices, with discrepancies being resolved through open discussion, consistent with previous analyses (Fooks et al., 2019; Lauber et al., 2021).

A further sub-analysis focused on the relationship between the teacher-facing materials and commissioned literature review, which were produced as part of the GambleAware and PSHE Association partnership. Specifically, drawing on the concept of intertextuality (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002; Fairclough, 2003), a forward cross-mapping (complementing the backward cross-mapping conducted above) was performed, exploring if and how the use of evidence observed in the commissioned literature review was reflected in the teacher-facing materials.

Finally, the evaluation reports were read in full, noting who had conducted them, using what data and methods, and the main findings. Claims about the strength of the evidence, limitations, and what counts as ‘best practice’ on educational measures were extracted and thematically analysed for the presence of agnogenic practices. Press releases and consultation responses were also searched for claims of effectiveness. M.v.S. and M.P. conducted this work and reached a consensus through discussion. This work forms part of a PhD fellowship that received ethical approval from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee (reference number 22936).

RESULTS

Agnogenic practices were identified in programme-related materials, in the evaluation design and in public statements. The following sections describe the agnogenic practices identified in each of these with illustrative examples (see Supplementary Materials for further examples), and their interlinked nature.

Agnogenic practices and techniques in youth education programmes

This section details the ways evidence was used to support claims made about the effectiveness and impacts of PSHE education and educational measures directed at youth gambling specifically. Few claims were supported by reference to an ostensibly validating source. When sources were cited, agnogenic practices described by Fooks et al. (2019) were apparent and reinforced the impression being given that any evidence that existed supported the use of education.

More specifically, we identified the use of three practices described by Fooks et al. (2019). Namely: (i) Confounding referencing, a practice composed of related techniques, cryptic references, out-of-place citations and inaccessible sources, each of which can mislead or confuse the reader about a claim being made, (ii) Misleading summaries, the practice, and associated techniques, of ‘inaccurate reporting of objectives, findings, and conclusions of sources’ and (iii) Evidential landscaping, the practice of either promoting a parallel evidence base which, in the context of policymaking, aims to shift the evidential basis that informs policy debates and evaluation or purposefully excludes relevant evidence, for example when responding to a public consultation. Fooks et al. (2019) describe the first as elevating a particular body of evidence over another qualitatively different one. The exclusion of evidence has two elements. The first is an observational selection/cherry picking, which excludes or ignores evidence that does not support a predetermined conclusion. The second is strategic ignorance described as ‘the technique of ignoring findings and evidence-backed observations in cited sources that contradict unsupported or weakly supported claims’ (see also McGoey, 2012).

However, some associated techniques described by Fooks et al. (2019) were not observed. For example, passé source or selective quotation, could have been used but were not. Others, such as double-counting, unmodelled data and data dredging, all of which relate to the practice of misusing quantitative and, specifically econometric data, are unlikely to have been used in the types of documents analysed. All the examples presented are from GambleAware-funded programmes. The YGAM materials did not cite any sources to support claims, instead simply stating that expert input had been provided. This itself may be seen as a form of evidential practice: appeals to authority (‘experts’) foreclose scrutiny and imply that the proposed approaches should be accepted at face value.

Confounding references

Cryptic references were used in the GambleAware/Fast Forward toolkit, where claims were justified by reference to entire organizations or programmes rather than evidence specifically related to the claim in question, an approach that precludes scrutiny of the source. Referencing entire strategies or education curricula were examples of out-of-place citations, placing a reference within the text to give the false impression of support for a particular claim. This was used in a circular fashion, citing the curriculum or strategy as evidence that it would somehow achieve its goals. Some references were to sources behind a paywall, constituting inaccessible sources. This latter technique is not uncommon to the academic literature, further demonstrating the importance of having openly accessible research.

Misleading summaries

Examples of misleading summaries were seen in the GambleAware/Fast Forward toolkit. These techniques make it possible to present evidence as strongly supportive of youth education even though it is really only weakly supportive of it or contradicts or is unrelated to it. For example, the toolkit claims that ‘[e]arly intervention to educate and support young people and families is an important tool for reducing gambling harms’, citing a review by Oh et al. (2017). Similarly, it claims that ‘[f]amily-based education and awareness programmes are another particularly effective way to improve outcomes for children and young people’, while citing a review by Kourgiantakis et al. (2016) that is actually concerned with the much narrower group of children exposed to parental problem gambling. Several features of misleading summaries, such as the omission of important qualifying information and illicit generalization, characterize these citations. The review by Oh et al. (2017) states that:

there is insufficient evidence from these programs to conclude that having good gambling knowledge and belief system [sic] can effectively reduce actual youth gambling behaviour. This implies that there is a lack of transference of knowledge and beliefs learnt towards behavioural change in gambling.

Similarly, the review the toolkit cites by Kourgiantakis et al. (2016) noted the need for more relevant studies of family-focused prevention programmes. It did not assess the effectiveness of the studies it included and had no studies of programmes directed at families. Thus, crucial qualifying information about both reviews is absent from the toolkit (omission of important qualifying information), and what was included mispresents the review by Kourgiantakis et al., a technique described as false attribution of focus. The two reviews are thus used to support an illicit generalization, which Fooks et al. (2019) describe as ‘[a] logical fallacy where the underlying evidence is insufficiently developed to support an inductive generalisation’.

A further example of misleading summaries can be seen in the way an external source is cited as having informed the design of one of the activities, Dice Game, which the toolkit implies takes 15–20 min to deliver and involves using a betting slip to bet on a dice game (Fast Forward and GambleAware, 2021). The toolkit states that:

This activity recreates a gambling experience, allowing young people to explore the feelings and perceptions around gambling. It also provides a practical example for participants to understand the meaning and implications of concepts such as the house edge and chasing losses, and to learn how probability affects one’s chances of winning and losing.

The passage is supported by a reference that implies that the activity derives from ‘Stack Deck: a programme to prevent problem gambling’ (Fast Forward and GambleAware, 2021). However, no effort is made to explain that Stacked Deck (the programme is incorrectly named in the toolkit) is a commercially available programme that comprises five core lessons of 35–45 min in length each and a sixth additional optional ‘booster’ lesson intended to be implemented in full with the aid of a facilitator’s guide and CD-ROM which ‘contains several key resources, including a digital slide show for each lesson, lesson handouts, take-home ‘family pages’ and other program components’ (Williams and Wood, 2010). Notably, the Stacked Deck facilitator’s guide explicitly states that ‘Stacked Deck is known to be effective when the entire program is delivered; only then can you expect similar results in your classroom or school’ (Williams and Wood, 2010).

This use of evidence represents an adapted form of the technique Fooks et al. (2019) refer to as the tweezers method, ‘the practice of picking phrases out of context, thereby changing the emphasis and intended meaning of the original text’, initially described by Ulucanlar et al. (2014). We use it here to capture the technique of selecting one element out of a larger package where the evidence relates to the implementation of that package in its entirety. This gives the appearance that the prescribed activity is evidence-based when, in fact, the delivery of the activity in isolation, in a shorter form and without the prescribed support materials is unevidenced. This also illustrates the omission of important qualifying information.

The GambleAware/PSHE Association Teacher handbook states that:

Donati et al. found that susceptibility to the gambler’s fallacy and superstitious thinking link to problem gambling. The researchers devised an intervention to reduce these cognitive distortions and tested it with adolescents in schools. Those receiving the intervention had reduced cognitive distortions and lower gambling participation. This suggests that reducing relevant ‘thinking errors’ through education has a positive effect.

This study was conducted in Italy on 34 male adolescents with a median age of 16.8 years (Donati et al., 2018). The authors report that, within one randomly selected school, they ‘chose a specific sample [of students] as it seems pertinent to deliver interventions to small groups of students that are homogenous in terms of risk factors, gambling habits, gender, and age’ (Donati et al., 2018). The intervention comprised two 2-hour lessons delivered over two weeks by ‘a developmental psychologist expert in the field of adolescent gambling research with a couple of operators belonging to the addiction unit of the socio-territorial service’ (Donati et al., 2018). A statistically significant decline in cognitive distortions, such as the gambler’s fallacy (the belief that a particular outcome is ‘due’ based on the sequence of outcomes that came before it) and superstitious thinking, was observed in the intervention group compared to controls. However, while self-reported gambling was significantly reduced in the intervention group at six months, the cross-sectional difference in this outcome between the two groups was not statistically significant, even though, as far as can be ascertained, that was the study’s prespecified aim. The authors proposed that this failure to find a significant difference may be because the study was underpowered. The authors also stated that further studies are needed to explore the role of other variables that act as predictors of gambling-related cognition distortions, and cautioned that further studies in other settings and populations (including girls) are needed to understand the generalisability of the study’s findings (Donati et al., 2018). Citing this study in this way provides a further example of misleading summaries, specifically the techniques of omission of important qualifying information and illicit generalization. Important qualifying information is omitted and this small study with major methodological limitations and findings with limited generalisability is presented as reflecting the totality of the evidence.

Evidential landscaping

We saw practices consistent with evidential landscaping in the education resources. This practice elevates bodies of research and findings supporting youth gambling education and the approaches adopted in the resources while overlooking evidence that undermines this perspective. Both the GambleAware/Fast Forward toolkit and the GambleAware/PSHE Association teaching resources demonstrated observational selection/cherry picking whereby studies favouring the approaches in the prescribed education activities (teaching about the mathematics of gambling and targeting erroneous cognitions) were presented while other evidence (e.g. on counter-marketing interventions and multi-faceted programmes that focus on youth empowerment and refusal skills) was not. The Fast Forward toolkit also ignored more recent and robust reviews than that conducted by Oh et al. that emphasize the limited evidence base for education-based interventions, such as those by Forsström et al. (2021) and Blank et al. (2021), both published online before other sources referenced in the toolkit.

The use of strategic ignorance was evident in how some findings and limitations of cited sources were omitted. For example, there was no engagement with a lack of long-term outcome data, evidence of equity impacts, or evidence of reducing gambling harms in the referenced sources. This demonstrates the synergistic nature of agnogenic practices, as discussed by Fooks et al., in that omission of qualifying information, false attribution of focus, and illicit generalizations facilitate the construction of this strategically ignorant account of the evidence.

Use of the commissioned literature review

Differences and similarities were identified between the GambleAware/PSHE Association commissioned literature review and the GambleAware/PSHE Association teacher-facing resources. While there were some similar claims about evidence and educational approaches, we identified important differences in the use of evidence and narratives about what is (un)known concerning effective gambling prevention education. Notably, the GambleAware/PSHE Association commissioned review explicitly acknowledges that literature reviews on educational interventions have found important limitations in the research base and outlines the gaps in current understanding (Hanson, n.d.). The author also discussed how any benefit from education is likely to be limited if contextual factors undermine it, as well as pointing to ethical concerns about failing to protect children and young people from the very harms they are being taught about:

On a more fundamental and ethical level, education should not be used to build young people’s resilience against something which in fact they could more simply be protected from. […] It would appear societal hypocrisy to teach young people truths about gambling in education, and yet simultaneously leave them unprotected from persistent industry attempts to obscure, undermine or challenge these truths […] And it is possible that at high levels of exposure and ‘nudging’, preventative education could have less impact (Hanson n.d.).

The teachers’ guidance discussed the ‘dark nudges’ that can be adopted by the gambling industry. However, the suggestion that education ‘should not be used to build young people’s resilience against something which in fact they could more simply be protected from’ and how the presence of such nudging could undermine the impact of preventative education was not discussed.

Agnogenic practices in evaluation and impact claims

Five evaluations of the included youth education programmes were identified. Two were located on the YGAM website: one by City Law School and another by NCVO. Three were located on the PSHE Association and GambleAware websites: a Demos evaluation of the KS4 materials, an Educari evaluation, described as an ‘external’ evaluation of two ‘internal’ evaluations, one being the Demos evaluation and another evaluation of a training session provided by Fast Forward, which could not be located, and an IFF Research evaluation of the Scottish Gambling Education Hub that was not designed to measure the impacts of individual elements such as the toolkit. Each had limitations. All evaluations relied heavily on indirect outcome measures, and only the Demos evaluation included classroom observations and a control group (Wybron, 2018). None of the evaluations were randomized (involving randomization to control and intervention groups). The NCVO report acknowledges that while it is likely that students have gained some form of knowledge and awareness from the YGAM programme, it is impossible to say with confidence what impacts can be attributed to it without a baseline or control. The findings of the evaluations are thus at high risk of bias. Notable reasons for concern include the 6.9% response rate for the YGAM teacher survey used in the NCVO report and the failure to report selection criteria. The focus groups in the NCVO evaluation were conducted with young people chosen ‘specifically because they were more likely to engage with the materials’ (Evanics and Latif, 2020). It is also impossible to understand what occurred during the focus groups as the relevant appendix is missing from the report as published on the YGAM website (Evanics and Latif, 2020).

While some of the reports present results based on self-reported increases in awareness, confidence and knowledge, the evaluations, which were not designed to establish effectiveness, do not permit us to say whether exposure to these programmes has increased knowledge, understanding or skills. They offer no robust evidence that they have significantly contributed to preventing or reducing gambling harms, particularly in those most at risk. It is also impossible to draw conclusions about any long-term impacts, nor their unintended consequences or impacts on inequalities. These evaluations therefore contribute to the production of ignorance.

The use of misleading summaries and evidential landscaping can be observed, reproducing an industry-favourable discourse in which educational initiatives are promoted as effective, evidence-based and evaluation-led. The Demos report demonstrates the techniques of omission of qualifying information as well as observational selection/cherry picking of supportive studies and strategic ignorance regarding the limitations of the evidence-base, in particular the lack of evidence that findings from the field of substance abuse can be transferred to a product such as gambling that is highly normalized and ubiquitous in the UK. A modified form of what Fooks et al. describe as the Hen’s teeth technique, ‘[a]n egregious form of cherry-picking that involves foregrounding obscure, outlying studies’, can be observed in the way the unrelated Marshmallow Test, whose validity is now disputed, is used in the Demos evaluation to legitimize teaching children about delayed gratification.

Another modified version of the tweezers method is seen in the way the concept of avoiding ‘scare tactics’ was tweezered from the literature on prison and parole programmes, like Scared Straight, targeted at addressing juvenile delinquency, so that informing about serious gambling harms, something young people expressed as desirable during evaluation focus groups, was dismissed as ‘contrary to best practice’. This view was reinforced by citing a report produced by Mentor-ADEPSIS, School-based alcohol and drug education and prevention—what works? (Mentor ADEPSIS, 2017). Yet the Mentor-ADEPSIS report says nothing about gambling. The statements made in the Demos report, therefore, seem to rely on extrapolating from other issues and conflate the act of informing with that of scaring and overlook the specificity of the studies from which this conclusion seems to have arisen. In contrast, the Educari evaluation provided a lengthy discussion about challenges yet to be overcome in delivering effective gambling prevention education, and the lack of evidence on the transferability of substance misuse education to gambling education (Ives, 2018).

Public statements by GambleAware and YGAM make claims about reach, impact and effectiveness of their programmes that are unsupported by available evaluations. While some of their statements acknowledge the limited extent to which education can be expected to change behaviour in ways that prevent gambling harms, other statements sometimes contradicted this (GambleAware, 2018). YGAM’s submission to the UK Government’s consultation on the review of the Gambling Act 2005 overlooks these limitations. Their claim that the NCVO evaluation provides ‘strong evidence’ of impact is not supported by the findings of this analysis. GambleAware’s statements to the UK Department of Education’s Call for evidence: ‘Changes to the teaching of Sex and Relationship Education and PSHE’, did not reflect the important limitations of the Demos evaluation, such as major differences at baseline between the two samples and the lack of objective measures of skills or knowledge acquisition or that the student data could not be matched as originally planned. Demos and GambleAware described the approach as ‘quasi-experimental’ which is ‘short of a randomised control’ and acknowledged the limits of such a design. However, this deflects from questioning why randomization was not performed given its feasibility and value in evaluating education-based interventions (Connolly et al., 2018).

These practices contribute to the construction of a chain of agnogenesis as the claims made about the evaluations obscure the important limitations of the evaluations (omission of qualifying information) and overstate what can be said about the programmes’ effectiveness given the limitations of the evidence described above (a form of confounding referencing). This reinforces the agnogenic practices adopted in the guidance and other teacher-facing documents themselves, thereby maintaining ignorance about the lack of robust evidence that can be used to design and implement educational measures. At the same time, this facilitates the construction of a public-facing reassuring narrative in which ‘best practice’ principles are said to be informing the delivery of effective, evidence-based, and evaluation-led gambling prevention education programmes to ‘safeguard’ children and young people.

DISCUSSION

By analysing UK-based youth gambling educational programmes, we have demonstrated how agnogenic practices are used to construct particular narratives about evidence, evaluation and ‘best practice’ and how they contribute to the production of ignorance: in concealing from the public and policymakers the weakness of the evidence supporting industry-favoured measures such as youth education. Of particular concern is how evidence has been used strategically to present this as best practice while downplaying the limitations of the evaluations that have been performed. Notably, the commissioned literature review, which expressed reservations about these programmes, was much less easily accessible than the teacher handbook, teaching materials, and evaluations. We could not identify a press release from GambleAware announcing the review, and it has yet to feature on the relevant education page of the GambleAware website, being accessible only by searching the PHSE website. This observation is in keeping with Suprans and Oreskes (2017) analysis of ExxonMobil’s climate change communications activities that public-facing documents adopted a more overtly denialist narrative about climate change than internal communications or those directed at decision-makers in private fora. This means that inaccurate, but industry-favourable narratives were more visible than those more accurately reflecting the state of the evidence, but which were less favourable to industry interests.

Our study has some limitations. It employs an analysis of documentary data related to three UK-based programmes. The analysis did not seek to understand or prove the motivations for ways that evidence has been used, teaching materials designed, or claims made about their effectiveness. More research is needed to understand the decision-making processes in the organizations that deliver the programmes we analysed and those involved in their accreditation and selection for use in schools. It should also be recognized that any interest group can ‘bend’ science to advance their interests (McGarity and Wagner, 2008). Importantly, we do not question the right of children and young people to be informed about the harms of gambling and how to help themselves or others. Our concern is to ensure they receive high-quality, well-evidenced and accurate education.

The aim and content of youth health education programmes therefore require more attention, including the need for robust evidence on how to tailor such interventions if they are to prevent harm in an equitable way. Yet statements made by both YGAM and GambleAware suggest that their programmes are evidence-based and evaluation-led. This approach serves as public relations for the industry who promote their funding of such programmes as evidence of their CSR. Previous studies of tobacco industry strategies suggest that the companies involved know that their education campaigns are at best ineffective and at worst counterproductive in reducing consumption but do promote a positive image of their corporate behaviour (Landman et al., 2002; Mandel et al., 2006; Sebrié and Glantz, 2007).

The application of findings and methods from studies or interventions in other fields to gambling education, and the way this discourse is used to legitimise not informing about gambling harms as ‘best practice’ must be questioned. Minimum standards for evaluation must be established, particularly concerning interventions claiming to be directed at ‘protecting’ children. The evaluations analysed for this study were not designed to measure effectiveness or detect unintended negative consequences and were not undertaken independent of the industry-funded organizations delivering the programme. Our findings should also guide how more recent materials produced by these organizations, such as the 2022 Gambling Education Framework (Boughelaf, 2022) and the November 2022 version of the toolkit (Fast Forward and GambleAware, 2022), are assessed by external stakeholders.

Implications

Our findings have implications for children and young people. New approaches to problematizing the practices we describe here are needed to identify how to counter them in ways that prioritize the best interests of children and young people. Considering the study findings from the perspective of children’s rights provides such a new lens. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) states that all children (defined in Article 1 as any person below 18 years of age) hold inalienable civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights (Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989), including the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health (or right to health) (Article 24) and related rights such as the right to education (Articles 28 and 29).

It is now widely acknowledged that the obligation to protect human rights requires that States adopt a preventative approach and effectively regulate the commercial determinants of health (Garde et al., 2020). To this effect, governments should adopt the measures necessary to protect children’s rights from the practices of the gambling industry, both in the classroom and beyond. In particular, they must ensure that children have access to quality health promotion and education. In accordance with the CRC, education systems must be, among others, dedicated to child well-being, dignity, and skills attainment. Urgent consideration should therefore be given to reducing the exposure of children to industry-funded education campaigns when such activity infringes on children’s rights. There is little evidence to support the provision of the programmes analysed in this study as a means to protect children from gambling harms whilst the use of agnogenic practices and the narratives that emerge can potentially displace more beneficial educational curricula content. At worst, the materials can have significant detrimental impacts on children.

This paper does not attempt to discuss in detail the implications of adopting a child rights-based approach to gambling harm and the extent to which it mandates the regulation of the commercial practices of the gambling industry. However, we argue that a child rights-based approach should support future analyses of industry engagement in the provision of education and related activities, and the implications for States as the guardians of children’s rights with the legal obligation to uphold their best interests as a primary consideration (Article 3(1) CRC, Garde and Byrne, 2020).

CONCLUSION

Our analysis reveals that agnogenic practices, previously identified among corporate strategies in other sectors, are being employed by those in receipt of gambling industry funding to construct industry-favourable narratives about the supporting evidence for, and the impacts of, the youth education programmes they deliver in the UK. While they claim to safeguard children and young people from gambling harms, the evidence presented to support these claims is limited and they may distract attention and divert resources from more effective policy measures. These practices need to be challenged and greater scrutiny and oversight of these forms of intervention are needed. The analytical approach presented here can be used to guide future studies in other contexts and in other industries.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was completed as part of a PhD undertaken by the first author (M.v.S.) for which M.P., A.R., M.M. and B.H. are PhD Supervisors. The authors wish to thank Mr Martin Jones for sharing his expertise and for insightful and valuable input which has very much enhanced the manuscript.

Contributor Information

May C I van Schalkwyk, Department of Health Services Research and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Pl, London WC1H 9SH, UK.

Benjamin Hawkins, MRC Epidemiology Unit, Institute of Metabolic Science, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambrdige CB2 0SL, UK.

Mark Petticrew, Department of Public Health, Environments and Society, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Pl, London WC1H 9SH, UK.

Nason Maani, Global Health Policy Unit, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh Chrystal Macmillan Building 15a George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LD, UK.

Amandine Garde, Law & NCD Unit, School of Law and Social Justice, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZR, UK.

Aaron Reeves, Department of Social Policy and Intervention, Barnett House, 32 -37 Wellington Square, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 2ER, UK.

Martin McKee, Department of Health Services Research and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Pl, London WC1H 9SH, UK.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.v.S. collated the data and conceptualized, designed and conducted the primary analysis, with input from all other authors. M.P. and N.M. conducted secondary coding of the data. M.v.S. led on writing of the initial draft of the manuscript will all authors contributing to the writing of subsequent versions of the manuscript and its finalization.

FUNDING

M.v.S. is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Fellowship (NIHR3000156) and her research is also partially supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North Thames. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. M.v.S. and M.P. has funding through and is a co-investigator, respectively, in the SPECTRUM consortium which is funded by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (UKPRP), a consortium of UK funders [UKRI Research Councils: Medical Research Council (MRC), Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Natural Environment Research Council (NERC); Charities: British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Wellcome and The Health Foundation; Government: Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office, Health and Care Research Wales, National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and Public Health Agency (NI)]. NM (co-investigator) and MP (principal investigator) have grant funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ‘Three Schools’ Mental Health Programme. A.R. is funded by Wellcome Trust (220206/Z/20/Z). B.H.’s position is supported by the Medical Research Council [Grant Number MC_UU_00006/7]. This work forms part of a PhD fellowship that received ethical approval from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee (reference number 22936).CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENTThe authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Betting and Gaming Council. (2020) £10m National Gambling Education and Support Programme Launched in the UK.https://bettingandgamingcouncil.com/news/10m-national-gambling-education-and-support-programme-launched-in-the-uk (last accessed January 27, 2022).

- Blank, L., Baxter, S., Woods, H. B. and Goyder, E. (2021) Interventions to reduce the public health burden of gambling-related harms: a mapping review. The Lancet Public Health, 6, e50–e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boughelaf, J. (2022) Effective Gambling Education and Prevention. GamCare, YGAM and Fast Forward. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, H., Coll-Seck, A. M., Banerjee, A., Peterson, S., Dalglish, S. L., Ameratunga, S.et al. (2020) A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 395, 605–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, P., Keenan, C. and Urbanska, K. (2018) The trials of evidence-based practice in education: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials in education research 1980–2016. Educational Research, 60, 276–291. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1989) Treaty no. 27531. United Na tions Treaty Series, 1577, pp. 3–178. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, M. A., Chiesi, F., Iozzi, A., Manfredi, A., Fagni, F. and Primi, C. (2018) Gambling-related distortions and problem gambling in adolescents: a model to explain mechanisms and develop interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanics, R. and Latif, S. (2020) Evaluation of YGAM’s Education Programme January 2018 to September 2019 Reducing The Risks of Gaming and Gambling for Young People. NCVO, England. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. (2003) Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. Routledge, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Fast Forward. (n.d.-a) What We Do. https://gamblingeducationhub.fastforward.org.uk/what-we-do/ (last accessed March 21, 2022).

- Fast Forward. (n.d.-b) Who We Are. https://www.fastforward.org.uk/who-we-are/ (last accessed January 28, 2022).

- Fast Forward and GambleAware. (2021) Gamble Education Toolkit 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fast Forward and GambleAware. (2022) Gamble Education Toolkit 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fooks, G. J., Williams, S., Box, G. and Sacks, G. (2019) Corporations’ use and misuse of evidence to influence health policy: a case study of sugar-sweetened beverage taxation. Globalization and Health, 15, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsström, D., Spångberg, J., Petterson, A., Brolund, A. and Odeberg, J. (2021) A systematic review of educational programs and consumer protection measures for gambling: an extension of previous reviews. Addiction Research & Theory, 29, 398–412. [Google Scholar]

- GambleAware. (2018) GambleAware publishes Educari Evaluation of Education Initiatives. https://www.begambleaware.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2018-09-13-educari-evaluation.pdf (last accessed January 31, 2022).

- GambleAware. (n.d.) About Us. https://www.begambleaware.org/for-professionals/about-us (last accessed April 22, 2022).

- Garde, A., Curtis, J. and De Schutter, O. (2020) Ending Childhood Obesity: A Challenge at the Crossroads of International Economic and Human Rights Law. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Garde, A. and Byrne, S. (2020) Combatting obesogenic commercial practices through the implementation of the best interests of the child principle. In Garde, A., Curtis, J. and De Schutter, O. (eds.), Ending Childhood Obesity: A Challenge at the Crossroads of International Economic and Human Rights Law. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, A. B., Fabbri, A., Baum, F., Bertscher, A., Bondy, K., Chang, H. -J.et al. (2023) Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. The Lancet, 401, 1194–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M. and McGoey, L. (2022) Revolutionary epistemology the promise and peril of ignorance studies. In Gross, M. and McGoey, L. (eds.), Routledge International Handbook of Ignorance Studies. Routledge, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, E. (n.d) Gambling Education Current Practice and Future Directions A Theory and Evidence Scope. GambleAware & PSHE Association, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Ives, R. (2018) Evaluation of GambleAware’s Harm Minimisation Programme: Demos and Fast Forward Projects Final’. Educari, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, M. W. and Phillips L. J.. (2002) Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. SAGE Publications, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Kourgiantakis, T., Stark, S., Lobo, D. S. S. and Tepperman, L. (2016) Parent problem gambling: a systematic review of prevention programs for children. Journal of Gambling Issues, 33, 8–29. [Google Scholar]

- Landman, A., Ling, P. M. and Glantz, S. A. (2002) Tobacco industry youth smoking prevention programs: protecting the industry and hurting tobacco control. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 917–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber, K., McGee, D. and Gilmore, A. B. (2021) Commercial use of evidence in public health policy: a critical assessment of food industry submissions to global-level consultations on non-communicable disease prevention. BMJ Global Health, 6, e006176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, L., Bialous, S. A. and Glantz, S. A. (2006) Avoiding ‘Truth’: tobacco industry promotion of life skills training. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 868–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marionneau, V., Järvinen-Tassopoulos, J. and Pirskanen, H. (2023) Intimacy, relationality and interdependencies: relationships in families dealing with gambling harms during COVID-19. Families, Relationships and Societies, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- McGarity, T. and Wagner, W. (2008) Bending Science: How Special Interests Corrupt Public Health Research. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McGoey, L. (2012) The logic of strategic ignorance. The British Journal of Sociology, 63, 533–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentor ADEPSIS. (2017) School-based Alcohol and Drug Education and Prevention—What Works?. Mentor ADEPSIS, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, B. C., Ong, Y. J. and Loo, J. M. Y. (2017) A review of educational-based gambling prevention programs for adolescents. Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health, 7, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, R. and Schiebinger L. (2008) Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance. Stanford University Press, Standford, CA. [Google Scholar]

- PSHE Association. (n.d.) About Us. https://pshe-association.org.uk/about-us (last accessed April 22, 2022).

- Riley, B. J., Harvey, P., Crisp, B. R., Battersby, M. and Lawn, S. (2021) Gambling-related harm as reported by concerned significant others: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of empirical studies. Journal of Family Studies, 27, 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sebrié, E. M. and Glantz, S. A. (2007) Attempts to undermine tobacco control: tobacco industry ‘youth smoking prevention’ programs to undermine meaningful tobacco control in Latin America. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1357–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supran, G. and Oreskes, N. (2017) Assessing ExxonMobil’s climate change communications (1977–2014). Environmental Research Letters, 12, 084019. [Google Scholar]

- Ulucanlar, S., Fooks, G. J., Hatchard, J. L. and Gilmore, A. B. (2014) Representation and misrepresentation of scientific evidence in contemporary tobacco regulation: a review of tobacco industry submissions to the UK government consultation on standardised packaging. PLoS Medicine, 11, e1001629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulucanlar, S., Lauber, K., Fabbri, A., Hawkins, B., Mialon, M., Hancock, L.et al. (2023) Corporate political activity: taxonomies and model of corporate influence on public policy. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 12, 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schalkwyk, M. C. I., Hawkins, B. and Petticrew, M. (2022) The politics and fantasy of the gambling education discourse: an analysis of gambling industry-funded youth education programmes in the United Kingdom. SSM—Population Health, 18, 101122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. J, and Wood, R. T. (2010) Stacked Deck: Facilitators Guide: A Programme to Prevent Problem Gambling Grades 9-12. Hazelden Information & Educational Services, Minnesota, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wybron, I. (2018) Reducing the Odds: An Education Pilot to Prevent Gambling Harms. Demos, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.