Abstract

Background

Erosive lichen planus (ELP) affecting mucosal surfaces is a chronic autoimmune disease of unknown aetiology. It is often more painful and debilitating than the non‐erosive types of lichen planus. Treatment of erosive lichen planus is difficult and aimed at palliation rather than cure. Several topical and systemic agents have been used with varying results. Another Cochrane review has already assessed interventions for lichen planus affecting the mouth.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions in the treatment of erosive lichen planus affecting the oral, anogenital, and oesophageal regions.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to September 2009: the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (from 2005), EMBASE (from 2007), and LILACS (from 1982). We also searched reference lists of articles and online trials registries for ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the effectiveness of any topical or systemic interventions for ELP affecting either the mouth, genital region, or both areas, in participants of any age, gender, or race.

Data collection and analysis

The primary outcome measures were as follows:

(a) Pain reduction using a visual analogue scale rated by participants; (b) Physician Global Assessment; and (c) Participant global self‐assessment.

Changes in scores at the end of therapy compared with baseline were analysed.

Main results

Fifteen RCTs were included, giving a total of 473 participants with ELP (study sizes ranged between 8‐94). All studies involved oral sites only. Six studies included participants with non‐erosive lichen planus but only the erosive subgroup was included for intended subgroup analysis. We were unable to pool data from any of the nine studies with only ELP participants or any of the six studies with the ELP subgroup, due to small numbers and the heterogeneity of the interventions, design methods, and outcome variables between studies.

One study involving 50 participants found that 0.025% clobetasol propionate administered as liquid microspheres significantly reduced pain compared to ointment (Mean difference (MD) ‐18.30, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐28.57 to ‐8.03), but outcome data was only available in 45 participants (high risk of performance bias for blinding of participants, low/unclear risk of bias overall). However, in another study, a significant difference in pain was seen in the small subgroup of 11 ELP participants, favouring ciclosporin solution over 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide in orabase (MD ‐1.40, 95% CI ‐1.86 to ‐0.94) (high risk of performance and detection bias due to likely lack of blinding, low/unclear risk of bias overall). Aloe vera gel was 6 times more likely to result in at least a 50% improvement in pain symptoms compared to placebo in a study involving 45 ELP participants (Risk ratio (RR) 6.16, 95% CI 2.35 to 16.13) (low risk of bias overall). No significant difference was seen in Physician Global Assessment in these three studies.

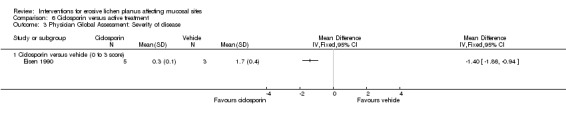

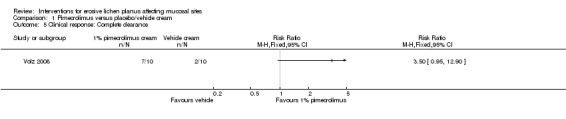

In a small single study involving 20 ELP participants, 1% pimecrolimus cream was 7 times more likely to result in a strong improvement as rated by the Physician Global Assessment when compared to vehicle cream (RR 7.00, 95% CI 1.04 to 46.95) (low risk of bias overall). In a study involving a small subgroup of 8 ELP participants, a significant difference was seen for an improvement in the severity of the disease as rated by the Physician Global Assessment, in favour of the ciclosporin group when compared to the vehicle (MD ‐1.40, 95% CI ‐1.86 to ‐0.94) (unclear risk of selection bias for allocation concealment, overall risk of bias low).

No statistically significant benefits were shown for topical tacrolimus or fluticasone spray in two separate studies of 29 and 44 participants respectively.

There is no overwhelming evidence for the efficacy of a single treatment, including topical steroids, which are the widely accepted first‐line therapy for ELP. Several side‐effects were reported, but none were serious. With topical corticosteroids, the main side‐effects were oral candidiasis and dyspepsia.

Authors' conclusions

This review suggests that there is only weak evidence for the effectiveness of any of the treatments for oral ELP, whilst no evidence was found for genital ELP. More RCTs on a larger scale are needed in the oral and genital ELP populations. We suggest that future studies should have standardised outcome variables that are clinically important to affected individuals. We recommend the measurement of a clinical severity score and a participant‐rated symptom score using agreed and validated severity scoring tools. We also recommend the development of a validated combined severity scoring tool for both oral and genital populations.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Male; Adrenal Cortex Hormones; Adrenal Cortex Hormones/adverse effects; Adrenal Cortex Hormones/therapeutic use; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/adverse effects; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/therapeutic use; Autoimmune Diseases; Autoimmune Diseases/drug therapy; Chronic Disease; Genital Diseases, Female; Genital Diseases, Female/drug therapy; Genital Diseases, Male; Genital Diseases, Male/drug therapy; Immunosuppressive Agents; Immunosuppressive Agents/adverse effects; Immunosuppressive Agents/therapeutic use; Lichen Planus; Lichen Planus/drug therapy; Lichen Planus, Oral; Lichen Planus, Oral/drug therapy; Mucous Membrane; Pain Measurement; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Treatments for erosive lichen planus affecting mucosal sites

Erosive lichen planus (ELP) is a condition that affects the mouth, oesophagus (food pipe or gullet), and anogenital region. It is caused by an over‐active immune system. It is often more painful and debilitating than the non‐erosive types of lichen planus. Depending on the site involved, affected individuals may experience pain, and difficulty eating; passing urine; or having sexual intercourse. Treatment is difficult and aimed at controlling symptoms, rather than cure. Several creams and tablets have been used with varying results.

This review looked at the effectiveness of treatments for ELP and included 15 studies, with 473 participants with ELP. All involved oral, but not genital, disease. Many studies were excluded either because they were not randomised controlled trials (where participants are divided into two groups at random) or because they recruited participants with all types of lichen planus, rather than just the erosive subtypes. All of these studies recruited small numbers of participants (12 to 94) and used a variety of different assessment methods and timings; hence, it was not possible to combine or compare results between studies directly.

We found only weak evidence for the effectiveness of any of the treatments for oral ELP. None of the studies involved genital or oesophageal disease; hence, no evidence was found for the treatment of these conditions. One small study found that 0.025% clobetasol propionate (a very potent topical steroid) administered as a spray significantly reduced pain when compared to ointment. In another study, a significant difference in pain was seen in the small subgroup of 11 ELP participants, favouring ciclosporin solution over 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide in orabase (a potent topical steroid). In a study involving 45 ELP participants, aloe vera gel was 6 times more likely to result in at least a 50% improvement in pain symptoms compared to placebo. In a study involving a small subgroup of 8 ELP participants, a significant difference was seen for an improvement in the severity of the disease in favour of the ciclosporin group when compared to the vehicle.

Several side‐effects were reported, but none were serious. With topical corticosteroids, the main side‐effects were oral candida (yeast) infection and pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen. Temporary burning was a common side‐effect reported with tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and pimecrolimus 0.1% cream.

Overall, there was no overwhelming evidence for the effectiveness of any single treatment, including topical steroids, which are the widely accepted first‐line therapy for ELP. This was mainly due to the lack of good‐quality, well‐conducted trials and small participant numbers. Another Cochrane review has already assessed interventions for lichen planus affecting the mouth.

Background

Description of the condition

Definition

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory condition that affects the skin and the squamous epithelium of mucosal surfaces lining the mouth, ears, eyes, and nose as well as the gastrointestinal and anogenital tracts. There are predominantly two patterns of inflammation described: the plaque (raised) type and the erosive (raw) type, although bullous, blistering, or hypertrophic (thickened) types also occasionally occur.

The plaque type occurs most commonly and is estimated to affect up to 2% of the population (Boyd 1991; Carrozzo 2008). It presents as purple raised areas with a surface made of a lacy, white network known as Wickham’s striae. The lesions are predominantly distributed on the inner aspect of the wrists and ankles, although they may occur on any body surface lined with squamous epithelium (Boyd 1991; Breathnach 2004). Plaques of LP are often itchy, and, without treatment, they may take up to two years to settle. Occasionally the lesions are present without many symptoms and may remain for years (Boyd 1991; Breathnach 2004).

In contrast, erosive lichen planus (ELP) is a very painful and debilitating condition. The prevalence of ELP is unknown. It occurs predominantly, but not exclusively, on the mucosal surfaces of the mouth and genitals (oral, vulval, vaginal, and penile lichen planus). Other less commonly affected sites include the eyes (Neumann 1993) and oesophagus (Abraham 2000). There may also be bladder, nasal, laryngeal, gastric, and anal involvement (Eisen 1999). Erosive lichen planus can be accompanied by classical cutaneous LP or other forms of mucosal LP, namely reticular (lacy), papular (solid, raised bumps less than 5 mm in diameter), plaque (raised), atrophic (thinned), and bullous (blisters) variants.

A severe variant of ELP in women involving both the genital and oral mucosa was described by Pelisse et al (Pelisse 1982; Pelisse 1989) as the vulvovaginal‐gingival (VVG) syndrome. This syndrome is a triad of (erosive or desquamative) vulvitis, vaginitis, and gingivitis. The equivalent condition in men is known as the peno‐gingival (PG) syndrome, described by Cribier et al in 1993 (Cribier 1993).

Since ELP can affect different body sites, a number of healthcare specialists are involved in managing affected individuals: oral medicine physicians; dermatologists; gynaecologists; and, if the oesophagus is involved, gastroenterologists.

Impact of Erosive Lichen Planus

Erosive lichen planus is a chronic, painful condition, which is often difficult to treat. The psychological, emotional, and physical distress associated with ELP affecting any mucosal site can be significant with affected individuals suffering low moods with or without treatment. This has economic consequences both for the people affected and the health system. Affected individuals frequently attend hospital complaining of pain and loss of function, which interferes with their personal and working life. It is important that healthcare providers are able to identify and treat any psychological issues arising as a result of ELP. Engaging a counsellor, as part of the multidisciplinary team, may be beneficial in these instances.

Symptoms vary according to the site involved. Individuals with erosive oral lichen planus (OLP) present with pain and difficulty eating. With milder disease the discomfort is mainly from spicy or acidic foods, and fizzy drinks. With more extensive disease there are painful, persistent erosions on the gingivae (gums), and ulcers on the buccal (inside of cheek), tongue, and labial (lip) mucosae. Difficulty eating results in weight loss and nutritional deficiencies, such as iron deficiency (Eisen 1999). Painful erosions lead to suboptimal dental hygiene and increased tooth decay.

The areas commonly affected in the vulva are the labia minora (inner lips), introitus (entrance to the vagina), and vaginal vault (arched roof of the vaginal cavity). The affected areas may be erythematous, atrophic, and eroded. This makes them tender and extremely painful to light touch, such as pressure from sitting and walking. Individuals complain of pain and stinging on passing urine, and they are sometimes only able to urinate in comfort by sitting or standing in water in the bath or shower. Anatomical alterations, such as fusion of the labia minora, may cause impaired urine flow.

Sexual intercourse can be impossible due to pain and anatomical changes. In addition, the eroded vagina bleeds easily on contact; hence, postcoital bleeding (bleeding following sexual intercourse) is typical. Inflammation higher up in the vagina (desquamative vaginitis) presents as a yellow discharge. With ongoing inflammation, the clitoral hood typically disappears, the labia minora adheres to the labia majora, and the introitus closes over. Scarring in the vagina leads to narrowing and a fibrosed vaginal vault, making cervical smears either impossible or difficult. In addition to organic dysfunction, the architectural disfigurement will cause psychological distress.

In men, ELP characteristically affects the glans penis, producing similar painful, tender, red and raw lesions, and reduced sexual function.

Risk of Malignant Transformation

Lesions of LP are thought to have an increased risk of development of malignancies; therefore, it is mandatory to follow up these people. The World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (Kramer 1978) states that oral LP is a condition that predisposes to malignant transformation. Approximately 1% to 5% of oral LP lesions will undergo malignant changes into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the mouth (Gandolfo 2004; Holmstrup 1988; Lo Muzio 1998; Silverman 1985). Approximately 1% to 3% of vulval LP lesions develop into SCC (Cooper 2006; Lewis 1994) and a small, but unknown, percentage of penile LP lesions transform into SCC (Bain 1989; Leal‐Khouri 1994). High‐risk factors for malignant transformation in oral LP include smoking; excessive alcohol ingestion; erosive or atrophic clinical types; presence of erythroplakic lesions (reddened patches with a velvety surface found in the mouth); and sites involving the tongue, gingival, or buccal mucosa (Scully 2008). No risk factors are known for progression of vulval LP into carcinoma of the vulva. It is unknown if early treatment of ELP reduces the risk of malignancy.

Description of the intervention

The management of ELP is challenging, and there is no clear agreement with respect to the best first‐line treatment in oral or genital disease. Indeed, neither is there agreement as to whether first‐line therapy should be the same at both sites. People often respond poorly to the available treatments. The treatments for both oral and genital ELP are similar, but they have never previously been considered together in a systematic review. Clinical experience of combined oral medicine and dermatology clinics suggests that effective treatment for ELP in the oral region is likely to be beneficial in the genital region and vice versa. ELP is a chronic autoimmune condition with T‐cell mediated immunity playing a major role; hence, most interventions are targeted at the immune system and increasingly at treatments to reduce T‐cell activity.

Most clinicians use topical or intralesional steroids as first‐line treatment for both oral and genital ELP. There is no clinical agreement for second‐line therapy, although a short course of systemic steroids may be administered for rapid control of symptoms. Steroid‐sparing agents, such as azathioprine, methotrexate (Jang 2008), or ciclosporin, can be used. Topical or systemic retinoids, anti‐malarials, dapsone, psoralen + UVA treatment (PUVA) (Lundquist 1995), thalidomide (Camisa 2000), aloe vera gel (Rajar 2008), topical tacrolimus (Kaliakatsou 2002), or topical rapamycin (Soria 2009) may be considered in refractory cases. Surgical management, such as carbon dioxide laser, cryotherapy, and excision, is not recommended due to the possibility of triggering lesions (Koebner's phenomenon) and recurrence of the inflammatory condition.

In recent years, reports have been published on the use of biological therapies, such as efalizumab (Cheng 2006; Heffernan 2007) and alefacept (Chang 2008). However, the European Medicines Agency (EMEA), which is the European Union (EU) body responsible for monitoring the safety of medicines, has recommended the suspension of marketing authorisation for efalizumab (Raptiva) over possible links between the drug and progressive multifocal leukencephalopathy (PML). A recent small case series comparing alefacept to placebo reported that alefacept may confer a moderate therapeutic response in ELP (Chang 2008). Alefacept is approved by the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) for the treatment of psoriasis, but it is not approved in the UK.

How the intervention might work

The exact cause of ELP is poorly understood. It is thought to be autoimmune and idiopathic in most cases. Studies suggest that upregulation of T‐cell‐mediated immunity plays a major role (Baldo 2010; Boyd 1991; Porter 1997; Scully 2008; Thornhill 2001), resulting in apoptosis of epithelial cells and chronic inflammation. Most interventions that are reported to improve ELP, as described above, have immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive effects. This may explain why efalizumab has been beneficial in some cases (Cheng 2006; Heffernan 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

For years, the accepted first‐line therapy for ELP has been the use of ultra‐potent topical steroids (Carbone 2009). Whilst there appears to be symptomatic improvement for some people (Cooper 2006), the condition rarely goes into complete remission. In addition to assessing whether treatments can improve symptoms in the short‐term, it is important to assess the long‐term management of ELP. This is because it is a chronic condition and long‐term use of some treatments, like potent topical steroids, can have side‐effects, such as skin thinning. There is poor consensus for a second‐line therapy in individuals who have failed to adequately respond to topical steroids. This has resulted in the emergence of newer therapies, such as tacrolimus (Lozada‐Nur 2006) and efalizumab (Heffernan 2007), in recent years. In such a painful and disabling condition, it is important that affected individuals are given the most therapeutically efficacious treatments.

A Cochrane review update on 'Interventions for oral lichen planus' has recently been published (Thongprasom 2011). The authors identified 28 randomised controlled trials (RCTs); however, due to the wide range of interventions compared, there is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of any specific treatment for oral LP as being superior. Another systematic review focusing on treatments used in oral LP (Zakrzewska 2005) concluded that due to small study sizes, lack of standardised outcome measures, and high likelihood of publication bias, the results are not reliable. Our review is different to these because it is not restricted to oral disease and focuses only on the erosive type of LP. Because ELP is a systemic disease affecting all mucosal surfaces, this review looks at not only oral sites, but all mucosal sites. Individuals with ELP affecting multiple mucosal sites represent a particularly challenging subset of individuals to treat.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions in the treatment of erosive lichen planus affecting the oral, anogenital, and oesophageal regions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the effectiveness of either topical or systemic interventions for ELP affecting either the mouth, genital region, or both areas. We included cross‐over studies, but not split body‐part designs because it is not possible to apply two topical treatments to either half of the oral mucosa or vulva without cross‐contamination.

Types of participants

We included any individual of any age, gender, or race who had been diagnosed by either a dermatologist, oral medicine physician, genitourinary physician, or a gynaecologist as having ELP affecting the mouth, oesophagus, and/or anogenital regions. A clinical diagnosis stating specifically 'erosive lichen planus' alone from an experienced physician was considered diagnostically sufficient. A histological diagnosis was not considered necessary since for erosive disease there are no specific histological features. Biopsy often serves to exclude dysplasia, rather than confirm the diagnosis of ELP.

We excluded any studies including individuals with idiopathic, plaque‐like LP (non‐erosive); individuals with lichenoid drug eruptions; or individuals showing evidence of dysplasia.

Types of interventions

We included all types of interventions, including topical treatments (such as potent topical steroids, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, and retinoids), oral medications (such as prednisolone, azathioprine, methotrexate, retinoids, ciclosporin, and mycophenolate), anti‐malarials, biologics, phototherapy, and surgical management.

We also included trials of different doses of the same intervention, comparison trials between different interventions, intervention versus placebo trials, intervention versus 'no treatment' trials, and cross‐over studies. We also explored intervention strategies, such as intermittent therapies that are designed to maintain remission and prevent further flares.

Types of outcome measures

Most outcome measures in ELP are assessed clinically. This includes a scale‐rating of improvement of clinical signs (e.g. erythema, ulceration) by investigators and symptoms (e.g. pain, discomfort) by participants as well as restoration of normal functions, such as sexual activity and a varied diet (ability to eat), as reported by participants.

Primary outcomes

(a) Pain reduction using a visual analogue scale rated by participants (e.g. 0 to 10).

(b) Physician Global Assessment (e.g. five‐point).

(c) Participant global self‐assessment.

Secondary outcomes

(a) Complete clinical response defined as the percentage of participants with complete resolution of clinical signs or symptoms.

(b) Partial response defined as the percentage of participants with at least 50% improvement.

A partial clinical response was defined as at least 50% improvement, mainly to test the literature. In practice, affected individuals would usually report that they are "better", "worse", or "the same".

(c) Reduction in severity of flares.

(d) Reduction in number of flares.

(e) Relapse rate when medications are stopped or reduced.

(f) Dermatology quality of life measures.

(g) Restoration of sexual activity (of most relevance to genital sites).

(h) Eating a normally varied diet (most relevant to oral involvement).

(i) Side‐effects reported.

(j) Reduction in target/mean lesion size (for oral lesions).

Timing of outcome assessment

Where possible, we recorded outcomes in the short‐term (less than six months) and long‐term (six months or more) from the beginning of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases up to 7 September 2009:

the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register using the following search terms: ((eros* or vulva* or oral or ulcerated or mucos*) and (lichen and planus)) or (lichen and planus);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library using the search strategy in Appendix 1;

MEDLINE (from 2005) using the search strategy in Appendix 2;

EMBASE (from 2007) using the search strategy in Appendix 3; and

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database, from 1982) using the search strategy in Appendix 4.

The UK and US Cochrane Centres (CCs) have an ongoing project to systematically search MEDLINE and EMBASE for reports of trials that are then included in the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials. Searches have been undertaken for this review by the Cochrane Skin Group to cover the years that have not been searched by the UK and US CCs.

A final prepublication search for this review was undertaken on 17 August 2011. Although it has not been possible to incorporate RCTs identified through this search within this review, relevant references are listed under Studies awaiting classification. They will be incorporated into the next update of the review.

Ongoing trials

We searched for ongoing trials in the following registers using the term 'erosive lichen planus' on 26 June 2011:

The metaRegister of Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com).

The US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au).

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry platform (www.who.int/trialsearch).

The Ongoing Skin Trials Register (www.nottingham.ac.uk/ongoingskintrials).

Searching other resources

Unpublished and Grey literature

We attempted to obtain unpublished trials through correspondence with authors.

Reference lists

We examined reference lists of the relevant trials and reviews identified.

Correspondence

We wrote to trial authors to clarify trial details.

Language

We did not impose language restrictions when searching for trials, and we sought translations where necessary.

Adverse Effects

We searched the included studies for reports of adverse effects.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (SCh and RM) independently reviewed the titles, abstracts, and key words of all records retrieved in the searches. SCh and RM obtained the full text of all relevant, or possibly relevant, references.

Data extraction and management

We designed a paper data extraction form according to the pre‐defined selection criteria. Two authors (SCh and RM) independently confirmed eligibility, assessed quality, and extracted data. Differences in opinion were resolved by discussion with a third author until a consensus was met. We kept logs of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion. One author (JL‐B) checked and entered data into Review Manager.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (SCh and RM) independently assessed the quality of the included studies by using the new features of Review Manager, as described in Table 8.5c of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), to assess the risk of bias (selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, and detection bias).

Measures of treatment effect

We presented binary data as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We presented continuous data as mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

There were no unit of analysis issues since all studies randomised whole participants. For studies that used a cross‐over trial design, we presented the results based on those reported in the original paper since we were unable to estimate appropriate statistics that allowed for the design (for example, conditional odds ratios).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the trial authors to try to obtain trial‐level data not originally reported, and we received replies from two authors. As we did not expect to have access to individual participant‐level data, we did not perform any imputation procedures.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to quantify statistical heterogeneity using I² statistic; however, no pooling of studies was performed due to the limited numbers of studies and clinical heterogeneity between the trials.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to generate a funnel plot to assess publication bias; however, this was not possible due to insufficient studies.

Data synthesis

Due to the limited number of studies and heterogeneity of interventions, we were unable to perform meta‐analyses but, where possible, we have presented the results from individual studies using forest plots.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analysis to explore treatment effect differences between ELP of the mouth and genitals; however, we were unable to do this since we did not identify any eligible studies of genital ELP.

Results

Description of studies

Please see Table 1 ('Summary of Included Studies') for a simple summary of the data in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables.

1. Summary of included studies.

| Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Frequency | Treatment Duration | Assessment Points | *Method of Diagnosis | Oral or Genital | Total Randomised | All Erosive? | ELP Randomised | Reported Results | ||

| 1 | Passeron 2007 | 1% Pimecrolimus cream |

Placebo | BD | 4 weeks | Week 0, 4, and 8 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 12 | Yes | 12 | 1% Pimecrolimus cream effective compared with placebo |

| 2 | Swift 2005 | 1% Pimecrolimus cream |

Placebo | BD | 4 weeks | Week 0, 2, and 4 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 20 | Yes | 20 | Significant reduction in VAS (P = 0.022) in treatment group, but not lesion size |

| 3 | Volz 2008 | 1% Pimecrolimus cream |

Placebo | BD | 30 days | Day 0, 30, and 60 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 20 | Yes | 20 | Significant reduction in Investigator Global Assessment (P = 0.032) in treatment group |

| 4 | Campisi 2004 | Clobetasol‐17‐propionate lipid‐loaded micro‐spheres 0.025% | Conventional lipophilic ointment in hydrophilic phase 0.025% | BD for 1 month then once daily | 2 months | Month 0, 1, and 7 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 50 | Yes | 50 | No significant difference |

| 5 | Carbone 2009 | Topical clobetasol propionate 0.025% | Topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% | BD | 2 months | Week 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 16 | Histology and clinical (WHO) | Oral | 35 | Yes | 35 | No significant difference |

| 6 | Radfar 2008 | Topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment | Topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment | QDS 2/52 ‐ TDS 2/52 ‐ BD 1/52 ‐ OD 1/52 | 6 weeks | Week 0, 2, and 6 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 29 | Yes | 29 | No significant difference |

| 7 | Conrotto 2006 | Topical ciclosporin 1.5% gel | Topical clobetasol 0.025% gel | BD | 2 months | Fortnightly for 4 months | Histology and clinical (WHO) | Oral | 40 | Yes | 40 | Topical clobetasol significantly better in inducing a clinical improvement, but no difference in improving symptoms |

| 8 | Hegarty 2002 | Fluticasone propionate spray 2 puffs | Betamethasone sodium phosphate mouthwash | 4 times per day | 14 weeks (cross‐over; 2‐week wash‐out) | Week 3, 6, 11, and 14 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 44 | Yes | 44 | At Week 6 fluticasone spray was significantly better in reducing clinical signs and pain, but no difference in VAS or QoL |

| 9 | Lin 2005 | Radix tripterygium hypoglaucum tablet (THT) | Tripterygium glucosides tablet (TGT) | THT ‐ 5 tablets TDS TGT ‐ 1.0 to 1.5 mg/kg TDS Taper dose after 2 to 4 weeks |

3 months | Month 0 and 3 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 94 | Yes | 94 | TGT superior to THT in reducing clinical severity (P = 0.043) |

| Subtotal | 344 | Subtotal | 344 | |||||||||

| 10 | Choonhakarn 2008 | Aloe vera gel | Placebo | BD | 8 weeks | Week 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 54 | No | 45 | Unable to comment |

| 11 | Eisen 1990 | Ciclosporin rinse | Placebo | TDS | 8 weeks | Week 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 16 | No | 8 | Unable to comment |

| 12 | Voute 1993 | Fluocinonide in adhesive base | Placebo | At least 6 times daily | 9 weeks | Week 0, 3, and 9; and month 5 to 19 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 40 | No | 27 | Unable to comment |

| 13 | Malhotra 2008 | Betamethasone oral mini‐pulse therapy | Topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% paste | Betamethasone ‐ 5 mg 2 days/week Triamcinolone ‐ TDS Both for 3 months, then taper dose |

6 months | Week 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 20, and 24 | Clinical only | Oral | 49 | No | 22 | Unable to comment |

| 14 | Sardella 1998 | Clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% | 5% Topical mesalazine gel in adhesive base | BD | 4 weeks | Week 0 and 4 | Histology and clinical (WHO) | Oral | 25 | No | 12 | Unable to comment |

| 15 | Yoke 2006 | Triamcinolone acetonide in orabase | Ciclosporin solution | TDS | 8 weeks | Week 0, 2, 4, and 8; and month 3, 6, 9, and 12 | Histology and clinical | Oral | 139 | No | 15 | Unable to comment |

| Subtotal | 323 | Subtotal | 129 | |||||||||

| Total | 667 | Total | 473 |

*Histology ‐ Histological features consistent with mucosal LP

Clinical ‐ clinical features consistent with mucosal LP

WHO ‐ Clinical features based on 1978 WHO criteria for oral precancerous lesions

Results of the search

The database search identified 220 papers initially. Fifty‐one full text papers were retrieved, of which 15 were included (Campisi 2004; Carbone 2009; Choonhakarn 2008; Conrotto 2006; Eisen 1990; Hegarty 2002; Lin 2005; Malhotra 2008; Passeron 2007; Radfar 2008; Sardella 1998; Swift 2005; Volz 2008; Voute 1993; Yoke 2006).

Included studies

The 15 included RCTs had a total of 667 participants with LP affecting mucosal sites, of which 473 participants had the erosive subtype of LP. Please see the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables for detailed information about all of the included studies, which are summarised as follows.

Design

Fourteen studies were conducted as a parallel design, and 1 study was conducted as a cross‐over design (Hegarty 2002).

Sample sizes

The number of participants in each individual study ranged from 12 to 139. Table 1 summarises the range of therapies. All of the included studies recruited participants with only oral ‐ not genital ‐ disease. Six studies (Choonhakarn 2008; Eisen 1990; Malhotra 2008; Sardella 1998; Voute 1993; Yoke 2006) included participants with non‐erosive LP. The breakdown of data on the ELP subset was, either, already published or obtained directly from the authors on request; hence, these studies were included, but considered separately. This brings the total number of participants with ELP to 473 (individual studies ranged between 8 to 94 participants).

Setting

All included studies were performed in secondary care. One study (Yoke 2006) was a multicentre study.

Participants

The diagnosis of ELP was confirmed clinically in all studies and histologically in all but one (Malhotra 2008). Three studies (Carbone 2009; Conrotto 2006; Sardella 1998) were based on the WHO 1978 criteria for oral precancerous lesions (Kramer 1978).

Interventions

Multiple therapies were considered, as shown in Table 1.

Six studies compared an active topical agent (aloe vera gel, ciclosporin rinse, fluocinonide in adhesive base, and 1% pimecrolimus cream in three studies) to placebo.

Two studies compared topical clobetasol propionate, currently the most frequently used treatment in clinical practice, either in a different delivery vehicle (lipid‐loaded microspheres versus ointment) or a different concentration (0.025% versus 0.05%).

Seven studies compared an active agent against another active agent head‐to‐head. These therapies can be broadly divided into three groups:

(i) topical steroids ‐ clobetasol propionate ointment and gel, triamcinolone acetonide paste, fluticasone propionate spray, betamethasone sodium phosphate mouthwash;

(ii) other topical therapy ‐ tacrolimus ointment, ciclosporin gel and solution, mesalazine gel; or

(iii) systemic therapy ‐ betamethasone oral mini‐pulse therapy, root of (radix) tripterygium hypoglaucum tablet (THT), tripterygium glucosides tablet (TGT).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

There was no consensus in the included studies regarding the tools used for assessing the primary outcomes (see Table 2).

2. Severity Tools Used for Primary Outcomes.

| Study | Clinical Severity | Symptoms | |

| 1 | Passeron 2007 | Surface area ordinal scale 1 to 4 | Pain (basal and during feeding, visual scale 0 to 4) |

| 2 | Swift 2005 | Clinical score (weighted sums of ulceration mm2, erythema mm2, reticulation mm2) | VAS 0 to 100 |

| 3 | Volz 2008 |

Erosive surface area ordinal scale of 1 to 4 (< 5% = 1, 5% to 15% = 2, > 15% to 25% = 3, > 25% = 4) Investigator Global Assessment on a 5‐point scale was determined at day 30 by qualifying the overall status of the oral mucosa in comparison with baseline |

VAS 0 to 10 (continuous and food‐triggered pain) NB a composite score (made of erosive surface area and VAS) was reported |

| 4 | Campisi 2004 | Clinical score 0 to 5 (Thongprasom 1992) | VAS 0 to 100 |

| 5 | Carbone 2009 | Clinical score 0 to 5 (Thongprasom 1992) | VAS 0 to 100 |

| 6 | Radfar 2008 | Mean lesion size | VAS 0 to 10 |

| 7 | Conrotto 2006 | Clinical score 0 to 5 (Thongprasom 1992) | VAS 0 to 10 |

| 8 | Hegarty 2002 |

Clinical score 0 to 5 (Thongprasom 1992) Mean surface area |

1.VAS 0 to 100 2. McGill pain score |

| 9 | Lin 2005 |

Clinical severity Participants divided into Grade I (erosive and ulcerative lesions) or Grade II (erosive lesions only) Response reported, subdivided into 3 categories (cured completely, effective, ineffective) |

None |

| 10 | Choonhakarn 2008 | Clinical score 0 to 5 (Thongprasom 1992) | VAS 0 to 10 |

| 11 | Eisen 1990 | Clinical score (0 to 3) | Symptom score (0 to 3) |

| 12 | Voute 1993 | Clinical severity measured by comparing clinical photographs. Only response reported, subdivided into 5 categories | VAS (scale not stated) |

| 13 | Malhotra 2008 | Clinical score (semiquantitative system 0 to 12 based on site, area, and presence of erosions) | None |

| 14 | Sardella 1998 | None | VAS 0 to 10 |

| 15 | Yoke 2006 | Clinical score 0 to 5 (Thongprasom 1992) | VAS 0 to 100 |

(a) Pain reduction using a visual analogue scale rated by participants

Ten studies measured participant‐reported symptoms using a visual analogue scale of 0 to 10 or 0 to 100 (Campisi 2004; Carbone 2009; Choonhakarn 2008; Conrotto 2006; Hegarty 2002; Radfar 2008; Sardella 1998; Swift 2005; Volz 2008; Yoke 2006). Voute 1993 also measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS), but the scale was not specified. Two studies measured this using different tools: Passeron 2007 used a visual scale of 0 to 4, and Eisen 1990 measured global symptom scores on an ordinal scale of 0 to 3. Two studies (Lin 2005; Malhotra 2008) did not measure participant‐reported symptoms at all.

(b) Physician Global Assessment (e.g. five‐point)

All but 2 studies (Radfar 2008; Sardella 1998) measured physician global assessment, but using several different methods: 6 studies (Campisi 2004; Carbone 2009; Choonhakarn 2008; Conrotto 2006; Hegarty 2002; Yoke 2006) used the clinical grading by Thongprasom 1992 consisting of a 6‐point ordinal scale from 0 (no lesions) to 5 (white striae with erosive area more than 1 cm²), 6 used their own clinical grading scale (Eisen 1990; Lin 2005; Malhotra 2008; Passeron 2007; Volz 2008; Voute 1993), whilst Swift 2005 measured clinical score as weighted sums of ulceration mm², erythema mm², and reticulation mm².

(c) Participant global self‐assessment

One study asked participants about their subjective evaluation of the efficacy of treatment at the end of the study (Passeron 2007) on a five‐point ordinal scale (worse, no effect, mild, moderate, or important improvement).

Secondary outcomes

The majority of the secondary outcomes specified in this review were not assessed in the included studies: e.g. (c) Reduction in severity of flares, (d) Reduction in number of flares, (g) Restoration of sexual activity (of most relevance to genital sites), and (h) Eating a normally varied diet (most relevant to oral involvement).

(a) Complete clinical response defined as the percentage of participants with complete resolution of clinical signs or symptoms

Volz 2008 reported complete clinical response.

(b) Partial response defined as the percentage of participants with at least 50% improvement

A partial clinical response was defined as at least 50% improvement, mainly to test the literature. In practice, affected individuals would usually report that they were 'better', 'worse', or 'the same'.

Carbone 2009, Conrotto 2006, Hegarty 2002, Lin 2005, Choonhakarn 2008, and Voute 1993 reported partial response.

(e) Relapse rate when medications are stopped or reduced

Passeron 2007 and Conrotto 2006 reported relapse rate when medication was stopped.

(f) Dermatology quality of life measures

Only one study measured quality of life (Hegarty 2002) using the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) and Oral Health QoL questionnaires (OHQOL). These two quality of life measurement tools are not specific to vulval disease.

(i) Side‐effects reported

All of the included studies measured side‐effects.

(j) Reduction in target/mean lesion size (for oral lesions)

Two studies reported a reduction in target/mean lesion size (Hegarty 2002; Radfar 2008).

Excluded studies

We excluded 36 studies, and the reasons for exclusion are listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Fifteen studies were excluded because initially they appeared to be RCTs, but on reading the full text, they were not RCTs.

Thirteen studies were not ELP, or recruited predominantly non‐erosive subtypes of mucosal LP (e.g. reticulate LP).

The authors of a further three papers were contacted for further information on breakdown of data for the erosive subtype, but no response was received. Of these three, one study recruited participants with vulval LP (Rajar 2008). This was the only study looking at vulval LP, but only 82% of subjects had erosive lesions. We excluded this study because no data for the erosive subtype was available. In addition, details of the randomisation method were not available.

The remaining five studies were excluded for the following reasons:

· one was a split body‐part design (Xia 2006);

· one was a review (Lehman 2009);

· one included participants with dysplasia (Scardina 2006);

· one trial compared circuminoids as an adjunct to oral steroids (Chainani‐Wu 2007); and

· one trial investigating the use of ignatia, a homeopathic remedy for hysteria, only included participants with "the mind and general symptom of ignatia" (Mousavi 2009).

Studies awaiting classification

As a result of the final search, we have identified six potential trials, which are detailed in the 'Characteristics of studies awaiting classification' tables. These will be dealt with in a future update of this review.

Ongoing Studies

We found four ongoing studies when we ran our pre‐publication search, details of which are in the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' tables. These will be dealt with in a future update of this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

We independently analysed the risk of bias for each individual study. This is discussed in detail in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables and summarised in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph ‐ review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary ‐ review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

Allocation

The randomisation method was stated in all but two studies (Voute 1993;Yoke 2006), which were rated as unclear. The methods used included random number tables (Carbone 2009; Choonhakarn 2008; Conrotto 2006; Eisen 1990; Hegarty 2002; Lin 2005; Malhotra 2008; Radfar 2008; Sardella 1998; Swift 2005), block randomisation (Campisi 2004; Passeron 2007), and an automated system of assigning randomisation numbers (Volz 2008).

Allocation concealment was stated in seven studies via a central office pharmacy and was, therefore, judged at low risk of bias (Choonhakarn 2008; Conrotto 2006; Radfar 2008; Swift 2005; Volz 2008; Voute 1993; Yoke 2006).

Blinding

Campisi 2004, Hegarty 2002, Malhotra 2008, and Yoke 2006 were not blinded to participants for practical reasons relating to the mode of therapy administration or use of different bases. It was unclear if Lin 2005, Passeron 2007, and Voute 1993 were blinded to participants.

Ten studies were blinded to clinicians. It was unclear if Lin 2005, Malhotra 2008, Passeron 2007, Voute 1993, and Yoke 2006 were blinded.

Incomplete outcome data

Of the nine studies which recruited only ELP participants, six studies performed intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses (Hegarty 2002; Lin 2005; Passeron 2007; Swift 2005; Volz 2008; Radfar 2008), of which one study (Swift 2005) had two losses early on that were replaced before the study commenced. These six studies were rated as at low risk of bias for this domain. Three studies with losses did not appear to be ITT (Campisi 2004; Carbone 2009; Conrotto 2006) and were, thus, rated as at unclear risk of bias.

Of the six studies that recruited both ELP and non‐ELP participants, five performed ITT analyses (Choonhakarn 2008; Eisen 1990; Sardella 1998; Voute 1993; Yoke 2006) and were rated as at low risk of bias for this domain. One study (Malhotra 2008) was rated as at high risk of bias for this domain because there were three losses to follow‐up that were not included in the final analysis.

Selective reporting

Hegarty 2002 did not report any data on clinical score 0 to 5 (Thongprasom 1992), even though this was mentioned in their methods section "clinician (objective) assessment", so it was the only study rated as at high risk of bias for this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not find any other potential sources of bias in any of the 15 included trials.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

(a) Pain reduction using a visual analogue scale (VAS) rated by participants

All of the studies reported pain as a pain score, rather than a reduction in pain. Additionally, the outcome relates to the pain score at follow‐up, and baseline scores were not taken into account for this review since using randomisation methods should eliminate differences at baseline between the two interventions groups.

In the Swift 2005 study (n = 20), which compared 1% pimecrolimus cream against placebo for 4 weeks, no significant reduction in pain was seen (MD ‐3.30, 95% CI ‐20.22 to 13.62) (see Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pimecrolimus versus placebo/vehicle cream, Outcome 1 Pain reduction using visual analogue scale (VAS).

In the Passeron 2007 study (n = 12), which compared 1% pimecrolimus cream against placebo, no significant reduction in basal pain (MD 0.16, 95% CI ‐0.86 to 1.18) or pain when feeding (MD 0.34, 95% CI ‐1.36 to 2.04) was seen (see Analysis 1.1).

In the Campisi 2004 study (n = 50 recruited, but follow‐up data was only available in 45 participants), 0.025% clobetasol propionate lipid‐loaded microspheres were found to significantly reduce pain when compared to a conventional formulation (0.025% lipophilic ointment in the hydrophilic phase) (MD ‐18.30, 95% CI ‐28.57 to ‐8.03) (see Analysis 2.1). However, in the Sardella 1998 study (n = 12), no significant reduction in pain was seen for 0.05% clobetasol propionate when compared to 5% mesalazine gel (MD ‐0.83, 95% CI ‐4.12 to 2.46) (see Analysis 2.1). Additionally, no significant difference in pain was seen when 0.025% was compared to 0.05% clobetasol propionate in the Carbone 2009 study (n = 30) when comparing the mean scores (MD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐1.42 to 0.90) (see Analysis 2.1) or when defined as at least a 50% improvement (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.67) (see Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clobetasol propionate versus active treatment, Outcome 1 Pain reduction using visual analogue scale (VAS).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clobetasol propionate versus active treatment, Outcome 2 Improvement in pain symptoms by VAS (> = 50%).

A significant difference in pain (MD 45.17, 95% CI 8.73 to 81.61) (see Analysis 3.1) was seen in the small sub‐sample of 11 ELP participants in the Yoke 2006 study in favour of ciclosporin solution when compared to 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide (potent topical steroid).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 0.1% Triamcinolone acetonide versus ciclosporin, Outcome 1 Pain reduction using visual analogue scale (VAS) (0 to 100 scale).

In the Radfar 2008 study comparing 0.1% tacrolimus against 0.05% clobetasol propionate, no significant reduction in pain was seen between the 2 groups (MD ‐0.64, 95% CI ‐1.91 to 0.63) (see Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 0.1% Tacrolimus versus 0.05% clobetasol, Outcome 1 Pain reduction using the VAS (0 to 10 score).

In the Choonhakarn 2008 study, aloe vera gel was 6 times more likely to result in at least 50% improvement in pain symptoms when compared to placebo (RR 6.16, 95% CI 2.35 to 16.13) (see Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Aloe vera gel versus placebo, Outcome 1 Improvement in pain symptoms by VAS (> = 50%) (Complete or good response versus poor or no response).

Additionally, in the Conrotto 2006 study comparing 1.5% ciclosporin against 0.025% clobetasol propionate, no significant difference was seen for at least a 50% improvement in pain (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.32) (see Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Ciclosporin versus active treatment, Outcome 1 Improvement in pain symptoms by VAS (> = 50%) (no symptoms versus partial or no response).

In the Hegarty 2002 cross‐over trial (n = 22) comparing fluticasone propionate spray against betamethasone sodium phosphate mouthwash, no statistical testing of the comparison for the pain score (VAS 0 to 100 score) was reported within the paper; therefore, it is not clear whether the difference is statistically significant or not (fluticasone [mean score 19.8] versus betamethasone [mean score 26]).

Volz 2008 only presented data for baseline and P values for changes in scores for each of the treatment groups without P values comparing the scores between the treatment groups.

We were unable to extract data on participant‐reported symptoms for Eisen 1990 because there was no breakdown of data for the ELP subgroup.

(b) Physician Global Assessment (e.g. five‐point)

No significant differences were seen for improvement in clinical response (defined using the Thongprasom score) between the 0.025% clobetasol‐17‐propionate and 0.025% conventional formulation groups in the Campisi 2004 study (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.61 to 0.61) (see Analysis 2.3), between 0.025% clobetasol propionate and 0.05% clobetasol propionate groups in the Carbone 2009 study (MD 0.47, 95% CI ‐0.26 to 1.20) (see Analysis 2.3), or between the 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide versus ciclosporin solution in the Yoke 2006 study (MD 0.61, 95% CI ‐0.79 to 2.01) (see Analysis 3.2).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clobetasol propionate versus active treatment, Outcome 3 Physician Global Assessment (Thongprasom score).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 0.1% Triamcinolone acetonide versus ciclosporin, Outcome 2 Physician Global Assessment (Thongprasom score).

No significant differences were seen for improvements in clinical response (defined using the Thongprasom score) between the 0.025% and 0.05% clobetasol propionate groups in the Carbone 2009 study (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.35) (see Analysis 2.4), or between the aloe vera and placebo groups in the Choonhakarn 2008 study (RR 2.64, 95% CI 0.11 to 61.54) (see Analysis 5.2). However, in the Conrotto 2006 study a significant difference was seen in favour of the 1.5% ciclosporin gel compared to 0.025% clobetasol propionate gel (RR 3.16, 95% CI 1.00 to 9.93) (see Analysis 6.2).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clobetasol propionate versus active treatment, Outcome 4 Physician Global Assessment (Thongprasom score).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Aloe vera gel versus placebo, Outcome 2 Physician Global Assessment (Thongprasom score).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Ciclosporin versus active treatment, Outcome 2 Physician Global Assessment (Thongprasom score).

In the Eisen 1990 study, a significant difference was seen for an improvement in the severity of the disease in favour of the ciclosporin group when compared to the vehicle (MD ‐1.40, 95% CI ‐1.86 to ‐0.94) (see Analysis 6.3).

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Ciclosporin versus active treatment, Outcome 3 Physician Global Assessment: Severity of disease.

In the Lin 2005 study, no significant difference was seen for an improvement in clinical response (defined as remarkably effective) in favour of TGT when compared to THT (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.20) for grade I (erosive and ulcerative) lesions or for grade II (erosive) lesions (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.28) (see Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Radix tripterygium hypoglaucum (THT) vs tripterygium glucosides (TGT), Outcome 1 Physician Global Assessment: Cure of erosive lesions.

In the Malhotra 2008 study, a significant improvement in clinical severity was seen at the end of the trial (at 24 weeks) in favour of 0.1% topical triamcinolone acetonide paste when compared to betamethasone oral mini‐pulse therapy (MD 1.78, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.39) (see Analysis 9.1). However, no significant differences between the treatment groups were detected at earlier outcome timings.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Betamethasone versus 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide, Outcome 1 Physician Global Assessment: Clinical severity (0 to 12 score).

In the Passeron 2007 study, no significant difference was seen for an improvement in clinical response (defined as surface of erosive lesions) between the 1% pimecrolimus and placebo groups (MD ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐1.39 to 0.39) (see Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pimecrolimus versus placebo/vehicle cream, Outcome 3 Physician Global Assessment: Surface of erosive lesions.

In the Volz 2008 study, 1% pimecrolimus cream was 7 times more likely to result in a strong improvement as rated by the Physician Global Assessment when compared to vehicle cream (RR 7.00, 95% CI 1.04 to 46.95) (see Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pimecrolimus versus placebo/vehicle cream, Outcome 4 Physician Global Assessment.

In the Voute 1993 study, no significant difference in improvement in clinical response (defined as complete response) was seen between the fluocinonide and placebo groups (RR 4.67, 95% CI 0.24 to 88.96) (see Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Flucinonide vs placebo, Outcome 1 Physician Global Assessment: Clinical signs (Complete vs good, partial, or no response).

In the Swift 2005 study, no significant difference was seen for an improvement in clinical response (defined as a weighted sum of ulceration, erythema, and reticulation between the 1% pimecrolimus and placebo groups) (MD ‐56.57 mm², 95% CI ‐134.02 to 20.88 mm²) (see Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pimecrolimus versus placebo/vehicle cream, Outcome 2 Physician Global Assessment: Weighted sums of ulceration, erythema and reticulation (mm²).

(c) Participant global self‐assessment

One study (Passeron 2007) assessed the participants global self‐assessment using a 5‐point scale, and found 5 out of 6 participants in the 1% pimecrolimus group rated their improvement as moderate or important, with the other participant rating no improvement. This was compared to 1 out of 6 participants in the placebo group who rated their improvement as moderate or important. Of the other 5 participants in this group, 2 rated their improvement as fair, 1 had no improvement, 1 was worse, and 1 gave no score (P = 0.316, Fishers Exact test).

Secondary outcomes

Again, there was no consensus regarding secondary outcome measures (Table 2).

(a) Complete clinical response defined as the percentage of participants with complete resolution of clinical signs or symptoms

In the Volz 2008 study, the difference in complete clearance between participants randomised to 1% pimecrolimus cream or vehicle cream was not statistically significant (RR 3.50, 95% CI 0.95 to 12.90) (see Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pimecrolimus versus placebo/vehicle cream, Outcome 5 Clinical response: Complete clearance.

(b) Partial response defined as the percentage of participants with at least 50% improvement

In the Carbone 2009 study, no significant difference was seen for an improvement in clinical response (defined as partial or complete response) between the 0.025% and 0.05% doses of clobetasol propionate groups (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.70).

In the Conrotto 2006 study, a significant difference was seen for an improvement in clinical response (defined as partial or complete response) in favour of 1.5% ciclosporin gel when compared to 0.025% clobetasol propionate gel (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.04).

In the Choonhakarn 2008 study, a significant difference in improvement in clinical response (defined as 50% or more improvement) was seen in favour of the aloe vera groups when compared to placebo (22/24 versus 1/21, respectively) (RR 19.25, 95% CI 2.83 to 130.85).

In the Lin 2005 study, a significant difference was seen in improvement in clinical response (defined as remarkably effective or effective) in favour of TGT when compared to THT (THT versus TGT ‐ RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.82) for grade I (erosive and ulcerative) lesions; however, no significant difference was seen for grade II (erosive) lesions (THT versus TGT ‐ RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.27).

In the Voute 1993 study, no significant difference in improvement in clinical response (defined as more than 33% improvement) was seen between the fluocinonide and placebo groups (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.62 to 14.62).

(c) Reduction in severity of flares

No studies reported this outcome.

(d) Reduction in number of flares

No studies reported this outcome.

(e) Relapse rate when medications are stopped or reduced

In Passeron 2007's study (n = 12) comparing 1% pimecrolimus cream to placebo for 4 weeks to treat erosive oral lichen planus, all participants who improved during treatment relapsed within 1 month of ceasing treatment.

Topical clobetasol gave less stable results than ciclosporin when therapy ended and showed a higher incidence of side‐effects (Conrotto 2006) (n = 40).

(f) Dermatology quality of life measures

In the Hegarty 2002 cross‐over trial (n = 22) comparing fluticasone propionate spray against betamethasone sodium phosphate mouthwash, no statistical testing of the comparison for the Oral Health Quality of Life index (OHQoL16) was reported within the paper. Therefore, it is not clear whether the difference is statistically significant or not (fluticasone [mean score 0.7] versus betamethasone [mean score ‐0.8]).

(g) Restoration of sexual activity (of most relevance to genital sites)

None of the included studies assessed the effectiveness of treatments of genital ELP; thus, this outcome was not reported.

(h) Eating a normally varied diet (most relevant to oral involvement)

No studies reported this outcome.

(i) Side‐effects reported

Several side‐effects were reported, but none were serious (see Table 3). With topical corticosteroids, the main side‐effects were oral candidiasis and dyspepsia (Campisi 2004; Conrotto 2006; Malhotra 2008; Yoke 2006). Fluticasone propionate spray caused nausea, swollen mouth, bad taste and smell, dry mouth, and a sore throat (Hegarty 2002) in a small proportion of participants, but they did not necessitate withdrawal of therapy. There were no reported side‐effects with topical mesalazine gel (Sardella 1998). Up to one‐third of participants receiving betamethasone oral mini‐pulse therapy reported transient oedema of the face, hands, and feet; epigastric discomfort; and fatigue (Malhotra 2008).

3. Side‐effects.

| Study | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Side‐effects | |

| 1 | Passeron 2007 | 1% pimecrolimus cream | Placebo | Pimecrolimus well‐tolerated, transient burning (2) during 1st 2 weeks |

| 2 | Swift 2005 | 1% pimecrolimus cream | Placebo | Pimecrolimus: slight burning tip of tongue after applying 1% pimecrolimus on gingiva lesions. Resolved within minutes |

| 3 | Volz 2008 | 1% pimecrolimus cream | Placebo | Pimecrolimus: burning sensation (4) and mucosal paraesthesia (1) Placebo: burning sensation (1) and mucosal paraesthesia (1) |

| 4 | Campisi 2004 | Clobetasol‐17‐propionate lipid‐loaded micro‐spheres 0.025% | Conventional lipophilic ointment in hydrophilic phase 0.025% | Oral candidiasis (1 in lipid‐loaded microspheres group, 2 in conventional ointment group) |

| 5 | Carbone 2009 | Topical clobetasol propionate 0.025% | Topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% | No side‐effects |

| 6 | Radfar 2008 | Topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment | Topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment | Burning sensation with topical tacrolimus |

| 7 | Conrotto 2006 | Topical ciclosporin 1.5% gel | Topical clobetasol 0.025% gel | Ciclosporin: skin rashes (2), parotid swelling (1), and dyspepsia (3) Clobetasol: dyspepsia (1) |

| 8 | Hegarty 2002 | Fluticasone propionate spray, 2 puffs | Betamethasone sodium phosphate mouthwash | Nausea (4); swollen mouth (1); bad taste and smell (6); difficulty in spray application (7); dry mouth (2); sore throat (1); red, painful tongue (1); and pseudomembranous candidiasis (1) |

| 9 | Lin 2005 | Radix tripterygium hypoglaucum tablet (THT) | Tripterygium glucosides tablet (TGT) | TGT ‐ menstrual disturbance (6) and leucopenia (1) |

| 10 | Choonhakarn 2008 | Aloe vera gel | Placebo | No serious side‐effects. 2 receiving aloe vera gel reported stinging and mild itching at lesions within 1st week, but symptoms spontaneously disappeared with continued use |

| 11 | Eisen 1990 | Ciclosporin rinse | Placebo | No adverse side‐effects. Transient burning sensation of mucosal surfaces during swishing of medication reported in all participants |

| 12 | Voute 1993 | Fluocinonide in adhesive base | Placebo | No side‐effects during study and follow‐up period |

| 13 | Malhotra 2008 | Betamethasone oral mini‐pulse therapy | Topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% paste | Betamethasone: oedema over face (transient) (7), oedema over hands and feet (4), epigastric discomfort (7), weakness/fatigue (5), loose stools (1), headache (1), diabetes mellitus (1), weight gain (1), and dry mouth (1) Triamcinolone: epigastric discomfort (1) and candidiasis (5) |

| 14 | Sardella 1998 | Clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% | 5% Topical mesalazine gel in adhesive base | No side‐effects |

| 15 | Yoke 2006 | Triamcinolone acetonide in orabase | Ciclosporin solution | No significant adverse events. Transient burning sensation upon initial application with both treatments |

Two participants receiving aloe vera gel reported transient stinging and mild itching at lesions that disappeared after the first week (Choonhakarn 2008). Transient burning of mucosal surfaces during swishing of ciclosporin rinse was reported (Eisen 1990). Participants receiving topical ciclosporin reported rashes (n = 2), parotid (salivary gland) swelling (n = 1), dyspepsia (n = 3) (Conrotto 2006), and transient burning (Yoke 2006). Participants receiving pimecrolimus 1% cream (Passeron 2007; Swift 2005) and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment (Radfar 2008) reported transient burning within the first 2 weeks, resulting in withdrawal of therapy in 1 participant in the latter study.

Menstrual disturbance was reported in six participants and leucopenia in one participant receiving tripterygium glycosides tablets (Lin 2005), which are known to be cytotoxic and unsuitable for individuals of child‐bearing age.

(j) Reduction in target/mean lesion size (for oral lesions)

In the Hegarty 2002 cross‐over trial (n = 22) comparing fluticasone propionate spray against betamethasone sodium phosphate mouthwash, no statistical testing of the comparison for the mean surface area of lesions was reported within the paper; therefore, it is not clear whether the difference is statistically significant or not (fluticasone [mean score 547.2 mm²] versus betamethasone [mean score 671.9 mm²]).

In the Radfar 2008 study, no significant difference in lesion size was seen between the 0.1% tacrolimus and 0.025% clobetasol propionate groups (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐1.09 to 1.10).

Discussion

Summary of main results

There are very few RCTs in the literature for the treatment of erosive lichen planus (ELP) affecting mucosal sites. Most RCTs that do exist focus only on oral disease. Topical potent steroids are the widely accepted first‐line treatment, but no overwhelming evidence exists to support this. There is weak evidence that 0.025% clobetasol propionate lipid‐loaded microspheres significantly reduce pain compared to conventional ointment in a study of 50 participants (however, outcome data were only available from 45 of the participants recruited). Ciclosporin solution reduced pain significantly compared to 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide in a small subset of 11 participants. Aloe vera gel was 6 times more likely to produce at least 50% improvement in pain compared to placebo. There was no significant difference in clinical severity rated by physicians or participants in any of the included studies (Carbone 2009; Conrotto 2006; Radfar 2008; Voute 1993; Yoke 2006).

This review suggests that there is only weak evidence for the effectiveness of any of the treatments for oral ELP. No evidence was found for genital ELP; this may be because studies on genital ELP are more difficult to conduct than oral ELP. In addition, the RCTs were heterogenous in disease definition, outcome variables, measurement scales, and assessment intervals; hence, pooling of data was not possible for meta‐analysis. Three studies based their clinical diagnosis on the WHO criteria 1978 for oral precancerous lesions (Kramer 1978). This clearly defines their criteria for clinical assessment. However, there is no WHO criteria for the diagnosis of vulval ELP.

The most commonly used clinical severity tool was adopted from the criteria first used by Thongprasom 1992, although this is not validated and applies only to oral lesions. No validated clinical severity tool is available for genital lesions. The most commonly used symptom‐scoring tool was a visual analogue scale (VAS) of 0 to 10 or 0 to 100 for pain, rated by participants. It has been suggested that the VAS is non‐linear and prone to bias, which limits its use as a serial measure of pain (Langley 1985). One study utilised the McGill Pain Questionaire, which measures several dimensions of pain and may be a better alternative to VAS (Langley 1985). Severity and duration of lesions were reported in only two studies (Passeron 2007; Radfar 2008). This is important because new‐onset, previously untreated lesions may respond more readily to treatment than long‐standing refractory lesions, even after the wash‐out period.

Therapeutic regimens were continued over four weeks to six months. All but one study (Lin 2005) had assessment intervals of two to four weeks during the trial period, which made assessments at baseline and at three months. Most of the outcome assessment points ended too early after the completion of the therapeutic regimen. Only 7 studies followed up participants after completion of the treatment regimen for 1 to 17 months (Campisi 2004; Carbone 2009; Conrotto 2006; Passeron 2007; Volz 2008; Voute 1993; Yoke 2006); hence, long‐term data on relapse rate and side‐effects is unknown. This is important as ELP is a chronic, relapsing, and remitting condition, and many affected individuals flare on cessation of therapy.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most of the studies in this review had small numbers of participants (range 12 to 139). The majority of the studies were heterogenous in outcome variables and disease severity scoring tools. All of the included studies recruited participants with oral disease; almost half of the studies recruited participants with all types of OLP and presented data for the erosive subset. Pooling of data was not possible with any of the studies. More RCTs on a larger scale are needed, using standardised outcome measures and well‐validated severity scoring tools in the oral and genital ELP populations.

Quality of the evidence

There were only a very small number of included RCTs, none of which included vulval ELP. All but three included studies specifically stated the method of randomisation. Only half of the included studies stated the method of allocation concealment. Blinding of participants was not possible in four studies as different delivery systems were used. Of the nine studies that recruited only ELP participants, six studies performed intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses. Of the six studies which recruited both ELP and non‐ELP participants, five performed ITT analyses.

Potential biases in the review process

Two authors (SCh and RM) reviewed the full texts separately using a data extraction proforma. Two authors (SCh and RM) independently confirmed eligibility, assessed quality, and extracted data. The method of randomisation was not clarified in three studies (Campisi 2004; Voute 1993; Yoke 2006). Where the allocation concealment method was not specified (in eight studies), no further clarification was sought. This may be a potential source of bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A Cochrane review update on 'Interventions for oral lichen planus' has recently been published (Thongprasom 2011). The authors concluded that there is a lack of strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of any therapy for oral lichen planus. Another systematic review focusing on treatments used in oral LP (Zakrzewska 2005) concluded that due to small study sizes, lack of standardised outcome measures, and high likelihood of publication bias, the results are not reliable.These conclusions are similar to our study results in terms of lack of evidence of efficacy of any type of treatment for erosive lichen planus, small study sizes, and lack of standardised outcome measures.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is a lack of strong evidence supporting the efficacy of any therapy for ELP affecting mucosal surfaces. Very few well‐conducted RCTs exist for the treatment of ELP. Most of those that do exist come from the oral medicine literature with small numbers of participants. Even though topical steroids are universally used as first‐line therapy for ELP, there is no overwhelming evidence for the efficacy of any single treatment.

Implications for research.

We suggest that future studies should have standardised outcome variables that are clinically important to affected individuals, such as the use of a modified standardised dermatology quality of life (QOL) questionnaire (e.g. the Dermatology Quality of Life Index [DLQI]), to measure the impact on daily activities of mucosal disease. Erosive lichen planus potentially interferes with daily activities, such as eating and sexual function; hence, QOL is an important parameter to measure. Moreover, many individuals may not necessarily divulge such difficulties in daily life due to embarrassment unless asked specifically; thus, this should be assessed routinely.

The measurement of clinical severity score and participant‐rated symptom score should be performed using agreed and/or validated severity scoring tools, such as the scoring system validated for oral lichen planus (Escudier 2007). Studies including both oral and genital sites should be encouraged due to the pattern of the disease. We suggest the development of an agreed and/or validated combined severity scoring tool for oral and genital disease. In addition, there is a real need for well‐designed RCTs on systemic therapy with newer biological agents for the treatment of severe ELP refractory to first‐line treatment with topical steroids.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 December 2015 | Amended | Author information (affiliation) updated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2009 Review first published: Issue 2, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 October 2015 | Amended | Author information (affiliation) updated: Gudula Kirtschig |

| 9 September 2015 | Amended | Author information (affiliation) updated |

| 1 June 2015 | Review declared as stable | A search of MEDLINE in February 2013 found just 3 trials that were all on oral lichen planus (LP), which is the subject of another Cochrane review. A search of MEDLINE in April 2014 found a few studies, but the update of this review will not include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that exclusively deal with oral LP or only oral erosive LP; all RCTs that include vulval and oral LP will be included. Our Trials Search Co‐ordinator ran a new search in 2015 to re‐assess whether an update was needed and did not find any RCTs for the topic; she will re‐run the search in May 2017. Thus, this review has been marked stable because the 6 studies awaiting classification in the last published review are all about oral lichen planus, and of the most recent search results, only 1 paper was potentially relevant. An update has not been considered necessary for three successive years. |

| 29 April 2014 | Review declared as stable | A search of MEDLINE in February 2013 found just 3 trials that were all on oral lichen planus (LP), which is the subject of another Cochrane review. A search of MEDLINE in April 2014 found a few studies, but the update of this review will not include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that exclusively deal with oral LP or only oral erosive LP; all RCTs that include vulval and oral LP will be included. Thus, this review has been marked stable because the 6 studies awaiting classification in the last published review are all about oral lichen planus, and of the most recent search results, only 1 paper was potentially relevant. An update has not been considered necessary for two successive years. Our Trials Search Co‐ordinator will run a new search in 2015 to re‐assess whether an update is needed. |

| 16 May 2012 | Amended | Reference has been made to the updated Cochrane review on "Interventions for Oral Lichen Planus" (Thongprasom 2011). Minor amendments have been made to the Abstract and the Plain Language Summary. |

Notes

A search of MEDLINE in February 2013 found just 3 trials that were all on oral lichen planus (LP), which is the subject of another Cochrane review. A search of MEDLINE in April 2014 found a few studies, but the update of this review will not include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that exclusively deal with oral LP or only oral erosive LP; all RCTs that include vulval and oral LP will be included. Thus, this review has been marked stable because the 6 studies awaiting classification in the last published review are all about oral lichen planus, and of the most recent search results, only 1 paper was potentially relevant. An update has not been considered necessary for two successive years. Our Trials Search Co‐ordinator will run a new search in 2015 to re‐assess whether an update is needed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Lichen Planus Support Group for their contribution to the review. We would also like to thank Paul Silcocks who was the statistical co‐author on the protocol.

The Cochrane Skin Group editorial base would like to thank the following people who commented on this review: our Key Editor Sue Jessop, our Assistant Statistical Editor Matthew Grainge, our Methodological Editor Philippa Middleton, Sheelagh Littlewood and Fenella Wojnarowska who were the clinical referees, and Lynne Chadburn who was the consumer referee.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL (Cochrane Library) search strategy

#1((eros* or vulva* or oral or ulcerated or mucos*) and (lichen and planus)) #2MeSH descriptor Lichen Planus explode all trees #3(lichen planus) #4(#1 OR #2 OR #3)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (OVID) search strategy

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized.ab. 4. placebo.ab. 5. clinical trials as topic.sh. 6. randomly.ab. 7. trial.ti. 8. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9. (animals not (human and animals)).sh. 10. 8 not 9 11. erosive lichen planus.mp. 12. Lichen planus.mp. or exp Lichen Planus/ 13. vulval lichen planus.mp. 14. vulvar lichen planus.mp. 15. oral erosive lichen planus.mp. 16. ulcerated lichen planus.mp. 17. mucosal lichen planus.mp. 18. 11 or 16 or 13 or 17 or 12 or 15 or 14 19. 18 and 10

Appendix 3. EMBASE (OVID) search strategy