Abstract

The adhesion of listeriae to host cells employs mechanisms which are complex and not well understood. Listeria monocytogenes is a facultative intracellular pathogen responsible for meningoencephalitis, septicemia, and abortion in susceptible and immunocompromised individuals. Subsequent to colonization and penetration of the gut epithelium, the organism attaches to resident macrophages and replicates intracellularly, thus evading the humoral immune system of the infected host. The focus of these studies was to investigate the attachment of the organism to murine peritoneal macrophages in an opsonin-dependent and opsonin-independent fashion. Assessment of competitive binding experiments by immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays showed that adhesion of the organism to macrophages in the presence or absence of opsonins was inhibited (90%) by N-acetylneuraminic acid (NAcNeu). In addition, the lectin from Maackia amurensis, with affinity for NAcNeu-α(2,3)galactose, blocked binding of L. monocytogenes to host cells. Oxidation of the surface carbohydrates on the organism by using sodium metaperiodate resulted in a dose-dependent reduction (up to 98%) in adherence to macrophages. Monoclonal antibody to complement receptor 3 did not prevent listeriae from binding to mouse macrophages or from replicating within the infected cells whether or not normal mouse serum was present. Based on our results, we propose the involvement of NAcNeu, a member of the sialic acid group, in the attachment of L. monocytogenes to permissive murine macrophages.

Adherence is the necessary first step in the infectious process of many intracellular pathogens (17, 28). The molecular mechanisms by which adherence and subsequent phagocytosis of the pathogen occur either through an opsonin-mediated process, involving complement or antibody and their appropriate receptors on the host cell, or through an opsonin-independent process in which bacterial adhesins recognize and attach to specific host cell receptors are not well understood. However, the receptors involved in opsonin-dependent adherence may also be involved in opsonin-independent adherence, as in the case of group B streptococci (GBS), which recognize and bind to complement receptor type 3 (CR3) in the absence of opsonins (2). Direct bacterial attachment between adhesins and host cell receptors has also been reported for Legionella pneumophila (18, 26) as well as for Listeria monocytogenes (5, 8, 24).

L. monocytogenes is the causative agent of food-borne listeriosis, a disease which primarily affects immunocompromised individuals, pregnant women, and neonates. Clinical manifestations range from mild, flu-like symptoms to meningoencephalitis and septic abortion. The organism has long been recognized as a facultative intracellular pathogen capable of infecting and replicating within a wide variety of cells, including fibroblasts, epithelial cells, hepatocytes, and cells from the mononuclear phagocyte system (1, 4, 12, 33). It has been shown that mononuclear phagocytes constitute the major effector cells of immunity in experimental infections (1, 20). L. monocytogenes has been shown to induce the deposition of C3b and its cleavage products iC3b and C3d through ester and amide linkages, resulting in the activation of the alternative pathway of human complement (6, 10). Recent studies indicate that CR3 mediates phagocytosis of L. monocytogenes in the presence of opsonins by a population of listericidal macrophages (8). However, the same studies demonstrated that nonlistericidal macrophages used CR3 as a minor binding molecule for listeriae (8). Use of a monoclonal antibody (MAb) directed against CR3 (CD11b/CD18) inhibited killing of L. monocytogenes in a dose-dependent manner for listericidal macrophages; indeed, when the MAb was used at high doses, these treated cells became permissive hosts (9). In contrast, the use of anti-CR3 antibody to block adherence and phagocytosis by nonlistericidal, permissive macrophages was largely ineffective. This finding appears to indicate two possible mechanisms of adherence and uptake for this pathogen: an opsonin-dependent mechanism through CR3 in which the organism is killed by the host cell, and an opsonin-independent mechanism through some receptor other than CR3 in which the organism parasitizes the host cell (27).

Although phagocytosis of L. monocytogenes by macrophages in the presence of opsonins has been investigated (7, 21), the role of opsonin-independent phagocytosis in the initiation of infection is not clear. The aim of this study was to investigate the interaction of L. monocytogenes with permissive murine peritoneal macrophages prior to phagocytosis and to partially characterize the bacterial adhesive molecules responsible for binding L. monocytogenes to these cells both in the presence and in the absence of opsonic components of serum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The fully virulent strain, UNHNY89, of L. monocytogenes serotype 1/2b was isolated on blood agar from the cerebrospinal fluid of an infant who died of neonatal meningoencephalitis. This isolate was subcultured once only on Trypticase soy agar and stored as stock cultures frozen at −70°C in 1% serum-sorbitol. Organism virulence was periodically assessed by the fertile hen egg method (3), and the 50% lethal dose in this system remained at approximately 21 CFU throughout the study period. Aliquots thawed from −70°C were plated on Trypticase soy agar and incubated overnight. Colonies were harvested, resuspended in Trypticase soy broth, and cultured for 8.5 h in a shaking incubator at 37°C. Organisms were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g, washed with serum-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and resuspended in HBSS to give 109 CFU/ml prior to the inoculation of macrophages.

Collection and cultivation of murine peritoneal macrophages.

BALB/c mice of both sexes were used at 3 to 6 months of age. Animals were housed at the University of New Hampshire animal maintenance facility according to Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (National Institutes of Health-approved protocols 1995). Murine peritoneal macrophages were elicited by intraperitoneal injection of each mouse with 2 ml of 4% thioglycolate broth aged for a minimum of 3 months. Mice were sacrificed by carbon dioxide asphyxiation 2.5 to 3.5 days poststimulation, and peritoneal exudate cells were extracted in HBSS by using three 10-ml peritoneal cavity lavages. These cell extracts were pooled, centrifuged at 220 × g for 10 min, and resuspended in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS; Sigma). Cells were enumerated by hemacytometer. For immunofluorescence assay (IFA), macrophages were seeded into six-well cell culture plates at 106 macrophages/well in 3 ml of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% HI-FBS. Each well contained a 22-mm-diameter glass coverslip. For enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), macrophages were seeded into 96-well plates at 105 macrophages/well in 200 μl of RPMI 1640 with 10% HI-FBS. All plates containing macrophages were incubated at 37°C for 6 to 8 h in the presence of 5% CO2 and washed three times with HBSS to remove unbound cells, and fresh serum-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.5 μg of cytochalasin D per ml was added to the cells to uncouple adherence from bacterial uptake in subsequent studies.

Host cell-organism interaction assays.

Cells were inoculated with 10-fold multiplicities of infection (MOI) ranging from 1 to 10,000. Following 1 h of incubation at 37°C, unbound bacteria were removed by washing and L. monocytogenes adherent to macrophages were assayed by IFA to determine the degree of organism binding at each MOI and hence define the kinetics of L. monocytogenes attachment to these cells. In this fashion, the optimum inoculation ratio of organisms to macrophage was determined to be an MOI of 100 (data not shown). This inoculum was used for all subsequent adherence assays.

Opsonin-independent adherence assays.

For organism treatment studies, bacteria were exposed to the various modifying agents listed in Table 1. After treatment, organisms were washed with serum-free HBSS and added to untreated host cells prior to assay for adherence. In duplicate experiments, macrophages were treated in a similar manner with those membrane-modifying agents described in Table 2. In the latter case, cells were washed with serum-free HBSS and inoculated with untreated listeriae.

TABLE 1.

Treatment protocol for the surface expressed adhesins of L. monocytogenes

| Agenta | Activity | Treatment time (min) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAc-neuraminic aldolase | 10 U/ml | 60 | Degradation of protein-, sugar-, and lipid-containing moieties on the surface of L. monocytogenes |

| β-Galactosidase | 100 U/ml | 60 | |

| Chymotrypsin | 500 U/ml | 60 | |

| Lipase | 100 U/ml | 60 | |

| Neuraminidase | 20 U/ml | 60 | |

| Protease | 10 U/ml | 60 | |

| Trypsin | 250 U/ml | 60 | |

| Glutaraldehyde | 0.1% | 10 | Immobilization of protein moieties |

| Sodium metaperiodate | 500 mM | 60 | Oxidation of carbohydrate moieties |

Prepared to pH 7.2 in HBSS (except for sodium metaperiodate, which was used at pH 5.0 in acetate buffer, and neuraminidase, used at pH 5.0 in HBSS) and added to bacterial cells for the specified time then washed to remove excess.

TABLE 2.

Treatment protocol for the modification of surface expressed receptors on macrophage host cells

| Agenta | Activity | Treatment time (min) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 0.1 U/ml | 30 | Degradation of sensitive host cell receptors |

| Lipase | 100 U/ml | 30 | |

| Pepsin | 100 U/ml | 30 | |

| Protease | 0.005 U/ml | 30 | |

| Trypsin | 50 U | 30 | |

| Formaldehyde | 1.0% | 10 | Immobilization of protein moieties |

| Glutaraldehyde | 0.1% | 10 | |

| Nonidet P-40 | 0.005% | 60 | Oxidation of lipids |

| Sodium metaperiodate | 5 mM | 10 | Oxidation of carbohydrate moieties |

Prepared to pH 7.2 in HBSS (except for sodium metaperiodate, which was used at pH 5.0) and added to macrophage host cells for the specified time then washed to remove excess.

In competitive binding studies, the monosaccharides fucose, galactose, glucose, mannose, N-acetylgalactosamine, N-acetylglucosamine (NAcGlu), and N-acetylneuraminic acid (NAcNeu) were tested individually at a concentration of 100 mM and were added to macrophages 1 h prior to inoculation with L. monocytogenes. In addition, the lectins derived from Canavalia ensiformis, Limulus polyphemus, Maackia amurensis, and Triticum vulgare (E-Y Laboratories, San Mateo, Calif.) were each added separately to macrophage monolayers at a concentration of 100 μg/ml 1 h before inoculation with listeriae. The common names and the binding affinities for each of the lectins used in these studies are given in Table 3. Bacterial attachment to host cells was determined in the presence of the sugars and lectins in a competitive fashion. For the sodium metaperiodate treatment regimen, the carbohydrate-oxidizing agent was applied to bacterial surfaces in acetate buffer at pH 5.0. Bacteria were washed to remove the treatment reagent prior to the addition to macrophages. Otherwise, all reagents were made in HBSS, adjusted to optimum pH, and filter sterilized through 0.22-μm-pore-size membranes prior to use. The attachment of L. monocytogenes to macrophages in the absence of the treatment regimens outlined in Tables 1 to 3 served as a control for all of these studies. Furthermore, the binding of GBS strain COH31 to macrophages was used as an additional control for the studies on carbohydrate oxidation with sodium metaperiodate at pH 5.0 to demonstrate enzyme activity at this pH. Following inoculation, listeriae were allowed to adhere to macrophages for 1 h, after which the cells were washed three times with HBSS to remove nonadherent bacteria, and the number of bound listeriae was assayed by IFA and ELISA.

TABLE 3.

Lectins used in competitive inhibition binding studies

| Lectin source | Common name (lectin) | Oligosaccharide recognitiona | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canavalia ensiformis | Jack bean (concanavalin A) | Branched N-linked hexasaccharides | 14 |

| Limulus polyphemus | Horseshoe crab (L. polyphemus agglutinin) | NAcNeu, NeuGNAc | 25 |

| Maackia amurensis | Maackia (M. amurensis agglutinin) | NAcNeu-α(2,3)Gal | 32 |

| Triticum vulgare | Wheat germ (wheat germ agglutinin) | Manβ(1,4)GlcNAc-β(1,4)GlcNAc | 34 |

| NAcNeu |

NAcNeu, N-acetylneuraminic acid; NeuGNAc, N-acetylglycolylneuraminic acid; Gal, galactose; Man, mannose; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine. Agents were prepared to pH 7.2 in HBSS and added to macrophage host cells for 1 h, cells were washed to remove excess, and assays were performed in a competitive fashion.

Opsonin-dependent adherence studies.

Listeriae were opsonized for 30 min in 5% normal mouse serum in HBSS at 37°C. Organisms were subsequently added to macrophages and allowed to adhere for 1 h. Nonadherent bacteria were removed by washing, and the plates were assayed for bacterial adherence by IFA and ELISA.

Role of CR3 in opsonin-independent and opsonin-dependent adherence.

The rat B-cell hybridoma line M1/70, expressing the MAb immunoglobulin G2b (IgG2b) anti-CR3, with specificity for mouse and human CR3 epitopes, was used to investigate the role of CR3 in opsonin-independent and opsonin-dependent adherence of L. monocytogenes to murine macrophages. This antibody blocks the binding of iC3b-coated targets to CR3 (9). The M1/70 cell line was cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum, and the supernatant was collected and concentrated in a Centriprep-10 (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.). The concentrated MAb was purified by protein G-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow column chromatography (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) and eluted with 0.2 M glycine at pH 2.0. Fractions were further concentrated after adjusting pH to neutrality, and the protein content was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Macrophage monolayers were incubated for 1 h with RPMI 1640 medium containing cytochalasin D (0.5 μg/ml) and rat IgG (10 μg/ml) to prevent organism uptake through phagocytosis and to block Fc receptor-mediated binding. Following cytochalasin treatment, macrophage monolayers were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with NAcNeu or for 30 min with increasing concentrations of the purified anti-CR3 MAb ranging from 0.1 to 25 μg/ml prior to the addition of listeriae.

Adherence assays. (i) Indirect IFA.

Macrophages, washed to remove nonadherent bacteria, were fixed in 10% (vol/vol) formalin in HBSS (pH 7.2) for 30 min at 25°C. After fixing, the cells were wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and treated with rabbit polyclonal anti-L. monocytogenes antiserum for 1 h at 37°C. Unbound globulin was removed, and goat anti-rabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) was added for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were stained with 0.01% propidium iodide in PBS for 20 min, washed, air dried, and mounted in glycerol containing 1% 1,4-diazobicyclo(2,2,2)octane. For the purposes of this study, a 50% decrease compared with untreated controls in the number of bacteria visualized as adherent to macrophages after a particular organism or host cell treatment was considered indicative of an interruption in adhesion of the organism to host cells (16).

(ii) ELISA.

Macrophages, washed to remove nonadherent bacteria, were fixed in absolute methanol for 10 min at 25°C and dried at 37°C. The plates were then washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 at pH 7.2, followed by incubation with 1% gelatin in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. After multiple washing with PBS-Tween 20, cells were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-L. monocytogenes antibody and probed with goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Boehringer Mannheim), each for 1 h at 37°C. After washing the cells, the chromogen 3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine and hydrogen peroxide were added. Development was halted at 10 min by addition of 2 M H2SO4, and the plates were read at 405 nm spectrophophotometrically on a model MA310 EIA reader (Whittaker M.A. Bioproducts, Walkersville, Md.). ELISA results enumerating bacteria were derived from a previously established standard curve. Furthermore, a similar 50% reduction in adherent bacteria was used to determine the activity of treatment regimens.

Statistical analysis.

IFA data were obtained from the average of three trials, counting the number of adherent bacteria on the first 100 cells counted per trial. Each trial consisted of a total of nine assays in which each treatment was performed in triplicate as one series of experiments using each batch of cells derived from mice at one harvesting; all treatment experiments were then performed three times to give a total of nine separate assays. ELISA data were generated in a similar fashion. Data from each assay method following each treatment were averaged and analyzed by the unpaired Student’s t test, using Abacus StatView software.

RESULTS

Host cell receptor saturation assays.

L. monocytogenes bound to murine peritoneal macrophages in the absence of either complement or specific antibody in a wash-resistant manner. Data from these assays indicated that at an MOI of approximately 1,000, host cell receptors were fully saturated with virulent L. monocytogenes. When an MOI of 100 was used, IFA data showed that macrophage host cell receptors bound approximately 19% of the bacterial inoculum whereas nonspecific binding was minimal. These host cell receptor-bacterial adhesin interaction studies showed that an inoculum of 100 organisms per macrophage was optimal for our purposes, and this was used for all subsequent opsonin-independent and opsonin-mediated investigations.

Bacterial surface treatment.

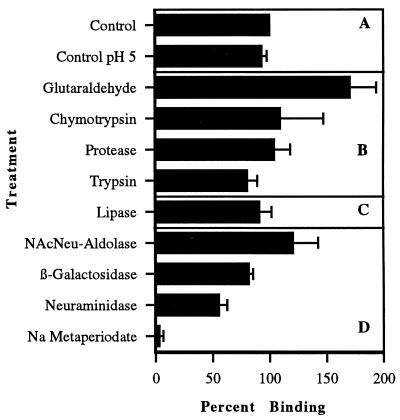

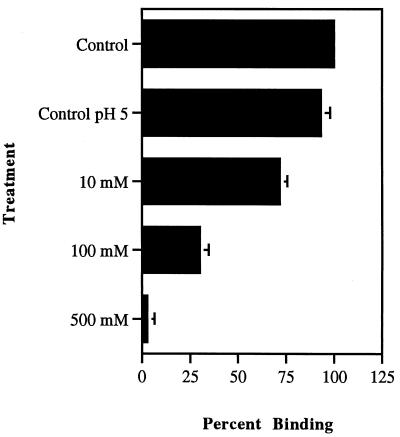

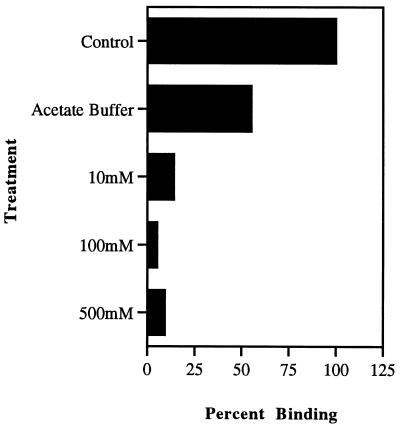

With the exception of glutaraldehyde, none of the bacterial cell surface-modifying agents listed in Table 1 were shown to decrease the viability of the bacterial population as determined by viable bacterial cell colony counts. However, modification of adhesin molecules on the bacterial surfaces showed that treatment with the carbohydrate-oxidizing agent sodium metaperiodate abolished binding of the organism to macrophages (Fig. 1). For L. monocytogenes, this destruction of binding by sodium metaperiodate was seen to be concentration dependent (Fig. 2). When GBS were treated with various concentrations of sodium metaperiodate, a similar dose-dependent decrease in binding of the organisms to macrophages was observed (Fig. 3). However, unlike Listeria attachment, which was unaffected by pH treatment alone, GBS binding was decreased by 45%. These data demonstrated that while sodium metaperiodate abolished binding, the use of pH 5.0 in the treatment buffers in the absence of the oxidizing agent had no effect on the attachment of listeriae to host cells. In addition, a 40% reduction in listeria binding (60% adhesion) to macrophages was effected following treatment with neuraminidase. With the exception of glutaraldehyde treatment, which showed an increase in binding of greater than 60% compared with control cells, no treatment protocol influenced adherence of listeriae to macrophages. These data indicated that the presence of neuraminidase-sensitive carbohydrate residues on the organism surface were involved in wash-resistant attachment to the receptors on the host cell and that bacterial viability was not essential for this binding to occur.

FIG. 1.

Adhesion of L. monocytogenes to murine peritoneal macrophages following surface treatment of the organism using the reagents listed in Table 1. (A) Control or untreated L. monocytogenes. The data represent 100% binding with all subsequent assays on treated bacteria expressed as a percentage of the control. (B) Effect of protein-cleaving agents and fixatives on organism binding. (C) Effect on organism attachment after treatment with a lipid-cleaving agent. (D) Changes in organism binding following treatment with carbohydrate-oxidizing or -cleaving agents. Binding data were generated by IFA; duplicate assays evaluated by ELISA gave similar results. Bars represent standard deviation of the mean. Statistical significance: sodium metaperiodate, P < 0.0001; neuraminidase, P ≤ 0.0004.

FIG. 2.

Adhesion of L. monocytogenes to macrophages following treatment of the organism with increasing concentrations of the carbohydrate-oxidizing compound sodium metaperiodate at pH 5.0. Binding data were generated by IFA. Controls were untreated L. monocytogenes (column 1) and L. monocytogenes in acetate buffer at pH 5.0 buffer (column 2). Bars represent standard deviation of the mean. Statistical significance at all concentrations: P < 0.0001.

FIG. 3.

Attachment of GBS to macrophages following treatment of the organism with increasing concentrations of the carbohydrate-oxidizing compound sodium metaperiodate at pH 5.0. Binding data were generated by IFA. Controls were untreated GBS (column 1) and GBS in acetate buffer at pH 5.0 (column 2). Standard deviations of the mean were too small for bars to be visible. Statistical significance at all concentrations: P < 0.0001.

Host cell surface modification.

In similar fashion, host cell surface-modifying agents, with the exception of the aldehyde fixatives and Nonidet P-40, did not adversely affect macrophage viability as assayed by cell counts and trypan blue vital staining. Macrophages exposed to those enzymes or oxidizing agents listed in Table 2 showed no significant change in ability to bind the pathogen in an opsonin-independent manner. However, treatment with either glutaraldehyde or formaldehyde abolished the ability of the macrophages to bind bacteria. These data suggested that host cell viability was essential to receptor activity. Alternatively, it is possible that cell surface protein moieties or complexes, which are resistant to those enzymes used, are involved but that conformational or mobile presentation is critical to function.

Competitive binding treatments with saccharides and lectins.

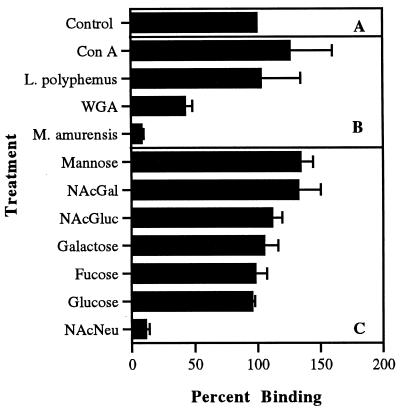

Coincubation of the saccharides with L. monocytogenes in the presence of host cells indicated that only NAcNeu competed effectively with the organism for receptor sites located on the host cell surfaces (Fig. 4). However, oxidation of the host cell surface carbohydrates by sodium metaperiodate had no effect on organism binding. Addition of the lectin from M. amurensis, and to a lesser degree the lectin from wheat germ agglutinin, caused a strong reduction in binding of the organism (Fig. 4). However, the lectins from concanavalin A and L. polyphemus had no effect on the adherence phenomenon.

FIG. 4.

Binding of L. monocytogenes to macrophages following treatment of the host cells with sugars and lectins in a competitive binding fashion. (A) Control preparations in the absence of agents competing for available receptor sites on the macrophage. The data represent 100% binding with all subsequent competitive assays expressed as a percentage of the control. (B) Adhesion of the organism in the presence of selected lectins. (C) Adhesion of the organism in the presence of selected sugar moieties. Binding data were generated by IFA; duplicate assays evaluated by ELISA gave similar results. Bars represent standard deviation of the mean. Statistical significance: M. amurensis lectin and NAcNeu, P < 0.0001. Con A, concanavalin A; WGA, wheat germ agglutinin; NAcGal, N-acetylgalactosamine.

The ability of NAcNeu to competitively interrupt the binding ability of the L. monocytogenes-host cell interaction was shown to be concentration dependent, in that the use of 10 or 25 mM NAcNeu reduced organism binding by 10% (90% adhesion) whereas 50 mM NAcNeu effected a decrease in attachment by approximately 30% (70% adhesion). The use of 100 mM NAcNeu reduced binding of the organism to macrophages by 90% (10% adhesion).

Opsonin-dependent adherence studies.

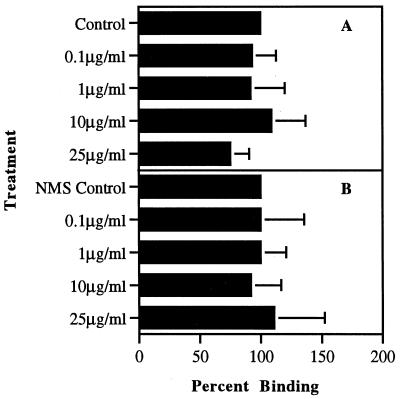

Compared with untreated controls, the presence of NAcNeu reduced L. monocytogenes binding to macrophages by approximately 80% (20% adhesion) when organisms had previously been opsonized with 5% normal mouse serum (Fig. 5). In addition, anti-CR3 MAb used as a blocking agent on the macrophages to prevent bacterial binding through CR3 components produced little or no effect on the adherence of either opsonized or nonopsonized L. monocytogenes to host cells (Fig. 6). This inability to prevent binding of the organism when the anti-CR3 MAb was used in a blocking fashion but in the absence of organism uptake was seen to be independent of the concentration of MAb used.

FIG. 5.

Binding of opsonized L. monocytogenes to macrophages following treatment with NAcNeu. Binding data were generated by IFA; duplicate assays evaluated by ELISA gave similar results. Controls were untreated L. monocytogenes. Bars represent standard deviation of the mean. Statistical significance: opsonized organisms treated with NAcNeu, P < 0.0001. NMS, normal mouse serum.

FIG. 6.

Binding of nonopsonized (A) and opsonized (B) L. monocytogenes to macrophages following blocking of CR3 receptors on the host cells by using MAb M1/70. Controls in panel A consisted of nonopsonized L. monocytogenes; controls in panel B consisted of opsonized L. monocytogenes. Binding data were generated by ELISA. Rat IgG was used to saturate Fc receptors on the surface of murine macrophages prior to the addition of antibody M1/70. Bars represent standard deviation of the mean. Statistical significance: (A) P > 0.2; (B) P > 0.5. NMS, normal mouse serum.

DISCUSSION

Adherence to host cell surfaces is a necessary first step in infection by intracellular bacterial pathogens such as L. monocytogenes. However, it has been shown that this initial step can take place by two different mechanisms: an opsonin-dependent process, in which antibody and/or complement proteins become involved in the complex interaction between bacteria and host cell; and an opsonin-independent process, in which adhesins present on the bacterial cell surface recognize host cell receptors. It is possible that these two processes result in different reactions by the host cell to the bacterium. For L. monocytogenes, uptake by listericidal macrophages via the CR3 receptor resulted in death of the organism, whereas uptake by nonlistericidal macrophages occurred through some other recognition factor and resulted in intracellular replication of the organism (8). Adherence of L. monocytogenes to host cell membrane-associated structures is therefore a complex interaction.

Following preliminary studies which established the ability of L. monocytogenes to bind to macrophages in a wash-resistant manner (24), the rate at which host cell receptors were saturated with listeriae was investigated. In all cases, an MOI of 1,000 resulted in high levels of organism attachment to the receptors on macrophage surface membranes; however, at this inoculum, the level of nonspecific binding of L. monocytogenes to culture plates as seen by IFA proved problematic. An MOI of 100 resulted in a reduced background binding while affording the advantage of greater significance to a 50% reduction in binding as a result of a particular treatment. In essence, this resulted in an inhibition of adherence which was defined as the concentration and nature of a treatment agent that reduced the binding of the organism to the host cells by 50% or greater. In this study, the presence of opsonin-independent attachment of L. monocytogenes to murine peritoneal macrophages has been established.

Receptor modification studies showed decreased adherence of L. monocytogenes following treatment of the host cell surface structures with formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde. Enzyme treatment of the host cell membrane had little or no effect on the adhesion of the organism to macrophages, while Nonidet P-40 and sodium metaperiodate were also ineffective at influencing the microbe-host cell binding phenomenon. These results indicated that the macrophage receptors involved in the attachment of the organism are protein in nature but that these are either sterically protected from the effects of proteolytic enzymes or present in sufficient quantities on the host cell membranes to allow binding of listeriae to occur at numbers similar to that found in the control macrophage cells.

Attachment of bacteria to mammalian host cells is often mediated by sugar-lectin interactions (5, 17, 23). Mannose (27) and polysialic acid (29) have been shown to facilitate the attachment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Neisseria meningitidis, respectively, to host cells, while Salmonella typhimurium adheres to intestinally derived cells via the glycoconjugate receptor, Galβ(1-3)GalNAc (15). In the present study, the results of the competitive binding assays using sugars suggested a role for NAcNeu in the binding of L. monocytogenes to macrophages. Indeed, a strong inhibition of attachment (90%) was seen in the presence of 100 mM NAcNeu, while other sugars tested had no effect on the adherence process. Data similar to those reported here showed that the addition of NAcNeu in competitive binding assays impaired the adhesion of strains of Shigella dysenteriae and S. flexneri to epithelial cells (17). Results from the use of lectins in similar binding assays strongly support the involvement of NAcNeu in adhesion. The lectin from M. amurensis showed inhibitory effects similar to those of NAcNeu on binding of L. monocytogenes; this lectin has a binding affinity for oligosaccharides which possess the terminal NAcNeu-α(2,3)Gal linkage. Wheat germ agglutinin reduced binding of L. monocytogenes by almost 50%. This lectin has binding specificity for both NAcNeu and NAcGlu. L. polyphemus lectin is known to bind to NAcNeu as well as N-acetylglycolylneuraminic acid. However, this lectin is extremely large, with an aggregate molecular mass of between 35 and 50 kDa, with four major protein bands seen on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (25), whereas the lectin from M. amurensis is a single polypeptide of 8 to 9 kDa on SDS-PAGE (32). Steric hindrance may therefore be an important factor in preventing the competition of L. polyphemus lectin with the adhesins of this organism.

Bacterial surface treatments indicated a 40% decrease in the binding of the organism following treatment with neuraminidase when used at pH 5.0, the optimal pH for the functioning of this enzyme. Oxidation of the bacterial surface with sodium metaperiodate resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in the binding of L. monocytogenes to mouse macrophages. Following treatment with 10, 100, and 500 mM sodium metaperiodate, this microbial adhesion was reduced by 30, 70, and 98%, respectively. Treatment with other enzymes and fixatives did not inhibit adherence of the organism significantly; in contrast, glutaraldehyde appeared to increase binding by 60% as measured by IFA. This may be due to cross-linking of surface proteins between individual organisms and subsequent binding of these linked listeriae to the cell surface.

Recent studies have indicated that CR3 is involved in the phagocytosis of L. monocytogenes by listericidal macrophages; however, CR3 is not involved in the phagocytosis of the organism by permissive, nonlistericidal macrophages (8, 9). Accordingly, we wished to determine the effect of the anti-CR3 MAb on adherence of L. monocytogenes as measured by our assay. The presence of this MAb had little or no inhibitory effect on the binding of L. monocytogenes to macrophages in the presence or absence of normal mouse serum. In the present study, a reduction of 30% in the binding of L. monocytogenes to nonlistericidal, thioglycolate-elicited macrophages was effected under non-opsonin-mediated conditions using anti-CR3 antibody. These results were similar to those reported by others (7, 8). However, in contrast to their reported results, the presence or absence of normal mouse serum in our system had no effect on binding in that approximately the same number of listeriae bound to both groups of control macrophage cells. The results reported here indicate that adherence and uptake in permissive macrophages occur by mechanisms other than through CR3 mediation. Significantly, NAcNeu at a concentration of 100 mM was highly inhibitory to the binding of opsonized-L. monocytogenes.

In contrast to GBS, L. monocytogenes does not utilize CR3 as a means for adhering to nonbactericidal, permissive macrophages (2, 8). However, the adhesin molecule used by listeriae to initiate the cellular infectious process was identical whether permissive or listericidal macrophages were used as host cells. Attachment in both the presence and absence of opsonins is strongly inhibited by NAcNeu. In addition, treatment of the bacterial cell surface with the carbohydrate-oxidizing agent sodium metaperiodate also inhibited listerial adhesion to macrophages. Based on our results, we propose the involvement of NAcNeu, a member of the sialic acid group, in the attachment of L. monocytogenes to nonlistericidal, permissive host cells. The process of attachment occurred through receptors other than CR3 and allowed the intracellular replication of the organism within host cells to proceed.

Entry of facultative intracellular pathogens into cells that are not professionally phagocytic has been described as a multifactorial process and has been studied extensively in Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella as well as Listeria. Indeed, it has been shown that entry and subsequent internalization is effected either through a trigger mechanism as is the case with Salmonella and Shigella or via a zipper mechanism as reported for Yersinia and Listeria (11, 19, 22, 30). Efforts to elucidate the nature of the bacterial ligand (invasin protein) as well as the host cell receptor (β1 integrin receptor) involved in the binding and entry of some facultative intracellular bacterial pathogens into cells has met with some success. Indeed, the critical role of the internalin molecule mediating bacterial entry and invasion of epithelial host cells has been demonstrated (13). In addition, E-cadherin, a calcium-dependent cell-to-cell adhesion glycoprotein located on the surface of epithelial cells, was shown to be the receptor for internalin (22). Further studies have shown that the bacterial surface protein p60 may be involved in uptake of L. monocytogenes by transformed nonproliferating epithelial cells, while the internalin proteins InlA and InlB mediate the invasion of these host cells when in an actively multiplying state (31). From the data presented here, it is possible that internalin proteins, in addition to regulating invasion, are involved in facilitating attachment to permissive peritoneal macrophages. However, the nature of the receptors located on macrophage membranes involved in opsonin-independent binding remains unclear. Additional studies are in progress to determine whether bacterial molecules other than internalin are involved in the attachment of L. monocytogenes to permissive macrophages. Understanding the mechanisms by which L. monocytogenes binds to host cells both in the presence and in the absence of opsonins is critical to elucidating the nature of the intracellular parasitism of this organism and may prove to be an important factor in the development of preventative treatment strategies for listeriosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture Hatch grant NH 333 and by a Central University Research Fund grant from the Office of Sponsored Research, UNH.

We thank Ronald Gibbons (now deceased) for helpful discussion during the course of this work; Jeffrey W. Hixon, Patricia A. Daggett, Kevin P. Richard, and Robert E. Gibson for technical assistance; and Thomas G. Pistole and Mary Smith for hybridoma cell line M1/70 and samples of purified antibody.

Footnotes

Scientific contribution no. 1942 of the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez Dominguez C, Carrasco-Marin E, Leyva-Cobian F. Role of complement C1q in phagocytosis of Listeria monocytogenes by murine macrophage-like cell lines. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3665–3672. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3664-3672.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antal J M, Cunningham J V, Goodrum K J. Opsonin-independent phagocytosis of group B streptococci: role of complement receptor type 3. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1114–1121. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1114-1121.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basher H A, Fowler D R, Rodgers F G, Seaman A, Woodbine M. Pathogenicity of natural and experimental listeriosis in newly hatched chicks. Res Vet Sci. 1984;36:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conlan J W, Dunn P L, North R J. Leukocyte-mediated lysis of infected hepatocytes during listeriosis occurs in mice depleted of NK cells or CD4+ CD8+ Thy1.2+ T cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2703–2707. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2703-2707.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowart R E, Lashmet J, McIntosh M E, Adams T J. Adherence of a virulent strain of Listeria monocytogenes to the surface of a hepatocarcinoma cell line via lectin-substrate interaction. Arch Microbiol. 1990;153:282–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00249083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croize J, Arvieux J, Berche P, Colomb M G. Activation of the human complement alternative pathway by Listeria monocytogenes: evidence for direct binding and proteolysis of the C3 component on bacteria. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5134–5139. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5134-5139.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drevets D A, Campbell P A. Roles of complement and complement receptor type 3 in phagocytosis of Listeria monocytogenes by inflammatory mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2645–2652. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2645-2652.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drevets D A, Canono B P, Campbell P A. Listericidal and nonlistericidal mouse macrophages differ in complement receptor type 3-mediated phagocytosis of L. monocytogenes and in preventing escape of the bacteria into the cytoplasm. J Leukocyte Biol. 1992;52:70–79. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drevets D A, Leenen P J M, Campbell P A. Complement receptor type 3 (CD11b/CD18) involvement is essential for killing of Listeria monocytogenes by mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 1993;151:5431–5439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fallman M, Andersson R, Andersson T. Signalling properties of CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and CR1 (CD35) in relation to phagocytosis of complement-opsonized particles. J Immunol. 1993;151:330–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finlay B B, Cossart P. Exploitation of mammalian host cell functions by bacterial pathogens. Science. 1997;276:718–725. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaillard J-L, Berche P, Mounier J, Richard S, Sansonetti P. In vitro model of penetration and intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes in the human enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2822–2829. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2822-2829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaillard J-L, Berche P, Frehel C, Gouin E, Cossart P. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminiscent of surface antigens from gram-positive cocci. Cell. 1991;65:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gesundheit N. Effect of thyrotropin-releasing hormone on the carbohydrate structure of secreted mouse thyrotropin. Analysis by lectin affinity chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5197–5203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannasca K T, Giannasca J P, Neutra M R. Adherence of Salmonella typhimurium to Caco-2 cells: identification of a glycoconjugate receptor. Infect Immun. 1996;64:135–145. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.135-145.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson F C, Tzianabos A O, Rodgers F G. Adherence of Legionella pneumophila to U-937 cells, guinea-pig alveolar macrophages, and MRC-5 cells by a novel, complement-independent binding mechanism. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:865–872. doi: 10.1139/m94-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guhathakurta B, Sasmal D, Datta A. Adhesion of Shigella dysenteriae type 1 and Shigella flexneri to guinea-pig colonic epithelial cells in vitro. J Med Microbiol. 1992;36:403–405. doi: 10.1099/00222615-36-6-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horwitz M A. Phagocytosis of the Legionnaires’ disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) occurs by a novel mechanism: engulfment within a pseudopod coil. Cell. 1984;36:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isberg R R, Tran Van Nhieu G. Binding and internalization of microorganisms by integrin receptors. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:10–14. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufman S H E. Immunity to intracellular bacteria. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:129–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacGowan A P, Peterson P K, Keane W, Quie P G. Human peritoneal macrophage phagocytic, killing, and chemiluminescent responses to opsonized Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1983;40:440–443. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.440-443.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mengaud J, Ohayon H, Mege R M, Cossart P. E-Cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell. 1996;84:923–932. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ofek I, Sharon N. Lectinophagocytosis: a molecular mechanism of recognition between cell surface sugars and lectins in the phagocytosis of bacteria. Infect Immun. 1988;56:539–547. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.3.539-547.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierce M M, Gibson R E, Rodgers F G. Opsonin-independent adherence and phagocytosis of Listeria monocytogenes by murine peritoneal macrophages. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:258–262. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-4-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roche A C, Monsigny M. Purification and properties of limulin: a lectin (agglutinin) from hemolymph of Limulus polyphemus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;371:242–254. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(74)90174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodgers F G, Gibson F C. Opsonin-independent adherence and intracellular development of Legionella pneumophila within U-937 cells. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:718–722. doi: 10.1139/m93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlesinger L S. Macrophage phagocytosis of virulent but not attenuated strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by mannose receptors in addition to complement receptors. J Immunol. 1993;150:2920–2930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Small P L C, Ramakrishnan L, Falkow S. Remodeling schemes of intracellular pathogens. Science. 1994;263:637–639. doi: 10.1126/science.8303269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephens D S, Spellman P A, Swartley J S. Effect of the (α2-8)-lined polysialic acid capsule on adherence of Neisseria meningitidis to human mucosal cells. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:475–479. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson J A, Baer J C. Phagocytosis by zippers and triggers. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:89–93. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88956-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velge P, Bottreau E, Van-Langendonck N, Kaeffer B. Cell proliferation enhances entry of Listeria monocytogenes into intestinal epithelial cells by two proliferation-dependent entry pathways. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:681–692. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-8-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W C, Cummings R D. The immobilized leukagglutin from the seeds of Maackia amurensis bind with high affinity to complex-type Asn-linked oligosaccharides containing terminal sialic acid-linked alpha-2,3 to penultimate galactose residues. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4576–4585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood S, Maroushek N, Czuprynski C J. Multiplication of Listeria monocytogenes in a murine hepatocyte cell line. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3068–3072. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.3068-3072.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto K, Tsuji T, Matsumoto I, Osawa T. Structural requirements for the binding of oligosaccharides and glycopeptides to immobilized wheat germ agglutinin. Biochemistry. 1981;20:5894–5899. doi: 10.1021/bi00523a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]