ABSTRACT

Objective

To establish priority gaps related to contextual factors (CFs) research and force-based manipulation (FBM)

Methods

A three-round Delphi following recommended guidelines for conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) involving international and interdisciplinary panelists with expertise in CFs and FBM. Round 1 was structured around two prompting questions created by the workgroup. Ranking of each priority gap was done by calculating composite scores for each theme generated. Consensus threshold was set with an agreement ≥75% among panelists. Median and interquartile range were calculated for each priority gap to provide the central tendency of responses. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to evaluate the consistency and stability of responses between rounds 2 and 3.

Results

Forty-six panelists participated in all three rounds of the Delphi. Consensus was reached for 16 of 19 generated themes for priority gaps in CFs research and FBM. The ranking of each identified gap was computed and presented. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was non-significant (P > .05), demonstrating consistency and stability of results between rounds.

Conclusion

The result of this Delphi provides international and interdisciplinary consensus-based priority gaps in CFs research and FBM. The gaps identified can be used to generate future research inquiries involving CFs research and FBM.

KEYWORDS: Contextual factors, Delphi study, force-based manipulation, manual therapy, priority gaps, outcomes

Background

Manual therapy, also referred to as force-based manipulation (FBM), is the passive application of mechanical force with a therapeutic intention [1]. Despite decades of laboratory and clinical research, the mechanism of action of FBM is still not fully understood [2]. Knowing the specific mechanism (how the treatment results in reduced pain and/or disability) for the various types of FBM (i.e. light touch, pressure, mobilization, thrust, adjustment) may help individualize the clinical application of FBM based on patient factors. Currently, there is speculation that many interventions share the same mechanisms [2], negating the need to provide higher cost multimodal care [3], or may signify a need to better differentiate who may benefit more from the delivery of specific combinations of care. Despite FBM being included in multiple professional clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), this inclusion is not universal, and a lack of consensus may be secondary to the known variability in patient response to this class of intervention [4]. One potential reason for the lack of clarity for FBM may be the existence of contextual factors (CFs) that may influence outcomes in clinical practice and research.

CFs can take the form of internal, external, or relational elements that characterize and influence the therapeutic encounter with the patient. Internal factors consist of memories, emotions, expectations, and psychological characteristics of the patient, while external factors include the physical aspects of therapy, such as the kind of treatment (pharmacological or manual) and the place in which the treatment is delivered [5]. Relational factors are represented by all the social cues that characterize the patient–physiotherapist relationships, such as the verbal information that the physiotherapist gives to the patient, the communication style, or the body language [5]. Evidence suggests that CFs related to personal and environmental domains of the biopsychosocial model are associated with the effectiveness of FBM [6]. However, there is insufficient data to support by what mechanism, CFs impact these treatment outcomes.

For future research to comprehensively explore the impact of CFs, there is a need to first appreciate the nature and extent of current knowledge gaps. It is believed that CFs may moderate the effects of FBM and, at times, provide important treatment effect, and should be considered in the clinical reasoning process. Recent research has emphasized the nonspecific effects of manual therapy, highlighting the complexity of the mechanism of action for FBM and the possible role of CFs. However, the mechanism and extent of CFs impact on outcomes is not fully understood and may ultimately show treatments provide improvement by similar mechanisms [7].

The purpose of this Delphi study was to establish priority gaps related to CFs evidence following FBM through a consensus decision of a panel of international and interdisciplinary research experts. With current knowledge gaps identified related to the interplay between FBM and CFs, future research may better isolate and investigate the role of CFs in supporting clinicians in improving clinical outcomes for their patients.

Objective

To establish priority gaps related to CFs research and FBM.

Methods

Study design

A 3-round International Delphi study following recommended guidelines for conducting and reporting of Delphi studies (CREDES) was performed [8]. Three rounds were selected offering sufficient reflection on group responses and are considered optimal for generating consensus [9]. An overview of the Delphi process can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Delphi process with responses rate in accordance with CREDES [8].

Ethics statement

This study was exempt by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University prior to performing (Pro00111279). All participants electronically signed an informed consent prior to screening and data collection using form M0345.

Workgroup

The workgroup consisted of eight individuals with expertise in CFs and FBM and experience with Delphi methodology. Workgroup members represented various clinical backgrounds (physical therapy (PT) and nursing) and professional profiles (clinicians, researchers, educators, and Delphi methodologists). Years of clinical experience ranged from 9 to 33. Five members resided in the United States and two resided in Italy.

Participants

An a priori sample of 30 panelists completing all three rounds is acceptable in Delphi methodology [10,11]. Anticipating a 30% attrition rate, a minimum of 48 panelists was targeted for round 1. Potential panelists were identified through professional international networking resources (Force-based Mechanisms Network, LinkedIn, and various manual therapy professional associations). A non-probability purposive sample of 208 individuals were invited to complete the initial screening via e-mail invitation. The e-mail included an informed consent statement, description of study objectives, definition of key terms, demographic data, publication record, professional credentials, and achievements. Primary inclusion was authorship of relevant publication in a peer-reviewed journal involving CFs and FBM. Additional criteria used to capture a diverse representation of panel experts included:

International participants (e.g. outside the United States);

Interdisciplinary (e.g. non-Physical Therapist) with varying background in force-based manipulations;

Advanced training in FBM by completing a formal training program (Residency or Fellowship);

Professional degree beyond bachelor’s degree (e.g. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Doctor of Science (DSc), Doctor of Education (EdD), Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO), Doctor of Chiropractic (DC), Master of Science (MS), Masters of Physiotherapy (MPT), Doctorate of Physical Therapy (DPT) or PhD candidate (cPhD));

Teaching experience involving manual therapy within fellowship, residency, or other advanced post-doctorate training program; and

Unique professional experience measuring biomechanical, neurophysiological, or CFs.

Data collection

Before distributing the survey to panelists, the questionnaire was pilot tested to establish face validity by sending the questionnaire to three individuals with backgrounds in CFs and FBM. The pilot data were not included in the main results. Each survey was administered using Qualtrics (Provo, USA), with survey links being shared via e-mail. Participants could only offer one response, and partial responses were accepted in all three rounds. In round 1, participants were provided the definition of CFs [12] and independently answered two open-ended questions [13].

Question 1:

What are the gaps in research with understanding how FBM works differently with CF;

Question 2:

What are the gaps in research in relation to how much of the treatment effect from FBM is associated with CF?

Qualitative thematic analysis and coding by commonality [14,15] was completed by the workgroup based on the responses from round 1. Participants were given approximately 2 weeks to complete a round. In round 2, participants rated their level of agreement with each theme using a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree, Somewhat Agree, Neutral, Somewhat Disagree, Strongly Disagree) [16]. In round 3, participants were shown the group’s responses from round 2 allowing the participants to alter their individual responses. All results from round 2 were sent to each participant for round 3 to determine whether consensus was met.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the participants demographic characteristics and group responses through each iteration. Consensus was achieved if ≥75% of the participants agreed or strongly agreed with a theme [17–19].

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) at the conclusion of each round. The open-ended list generated from round 1 was analyzed thematically. Demographic information and results from rounds 2 and 3 were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for each theme to identify the central tendency of responses. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used in round 3 to evaluate the consistency and stability of responses between rounds 2 and 3 for the identified themes. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Composite scores were calculated to provide the strength of the recommendation for each theme across participants for questions 1 and 2. Composite scores were calculated using the following formula.

(n1 × (−2)) + (n2 × (−1)) + (n3 × 1) + (n4 × 2)

n1 = number of respondents answering ‘Strongly Disagree’ with component of application

n2 = number of respondents answering ‘Disagree’ with component of application

n3 = number of respondents answering ‘Agree’ with the component of application

n4 = number of respondents answering ‘Strongly Agree’ with the component of application.

Results

Panel characteristics

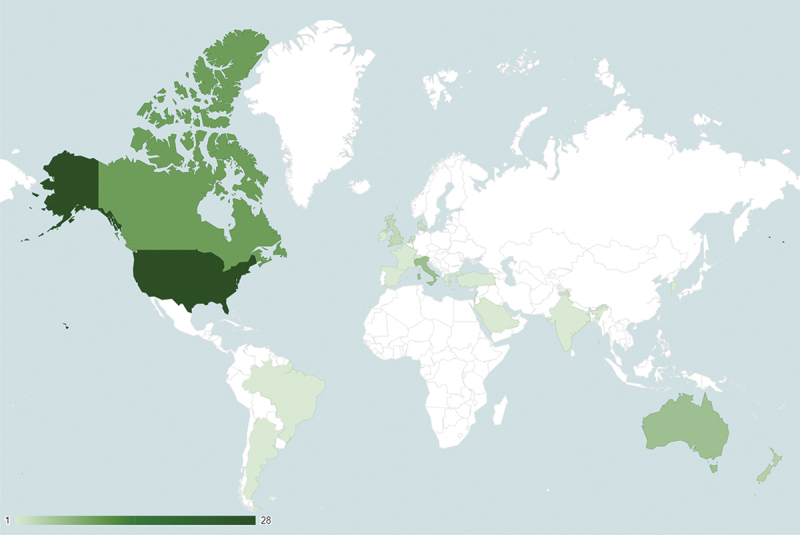

Two hundred and eight individuals were invited to fill out the panel screening and demographics and 165 responses were received. Seventy-seven experts representing 23 countries and 12 different professional backgrounds were eligible. Geographic representation can be viewed in Figure 2. Panel demographics and characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Geographic representation of panel experts.

Table 1.

Panel demographics and frequency of responses by round.

| Open-Ended Q’s (n = 77) |

Round 1 (n = 58) |

Round 2 (n = 59) |

Round 3 (n = 48) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Responses: 2 |

Incomplete Response: 3 |

Partial Response: 2 |

||

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | |

| Publication on Topic | 77 (100) | 56 (100) | 56 (100) | 46 (100) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 61 (79) | 44 (78) | 44 (78) | 35 (76) |

| Female | 15 (19) | 12 (21) | 12 (21) | 11 (23) |

| Undefined | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Teaching Experience on Topic | ||||

| Yes | 63 (81) | 52 (93) | 49 (87) | 39 (84) |

| No | 11 (14) | 2 (3) | 5 (8) | 5 (10) |

| Other a | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Practitioner Type | ||||

| Physiotherapy | 40 (51) | 32 (57) | 33 (58) | 26 (56) |

| Chiropractor | 15 (19) | 11 (19) | 11 (19) | 10 (21) |

| Neurology/Neuroscience | 7 (9) | 4 (7) | 4 (7) | 3 (6) |

| Osteopathy | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Biomechanics/Physics/Kinesiology | 5 (6) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | 2 (4) |

| Biomedical Engineering/Science | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Other b | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Educational Background | ||||

| Residency/Fellowship | 23 (29) | 13 (23) | 14 (25) | 8 (17) |

| Professional degree beyond bachelor’s degree (for example: MD, DC, MHA,MBA, JD, DPT) | 7 (9) | 5 (8) | 4 (7) | 5 (10) |

| Terminal degree (for example, PhD, EdD, DSc or cPhD) | 67 (87) | 46 (82) | 47 (83) | 41 (89) |

| Master’s Degree | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Interdisciplinary c | 45 (58) | 24 (42) | 22 (39) | 21 (45) |

| Region/Country | ||||

| New Zealand | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | 4 (7) | 3 (6) |

| Italy | 6 (7) | 4 (7) | 4 (7) | 3 (6) |

| Denmark | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Canada | 10 (12) | 6 (10) | 6 (10) | 7 (15) |

| USA | 28 (36) | 21 (37) | 18 (32) | 13 (28) |

| Netherlands | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Australia | 6 (7) | 4 (7) | 5 (8) | 5 (10) |

| United Kingdom | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 3 (6) |

| Israel | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Other d | 14 (18) | 12 (21) | 12 (21) | 10 (21) |

a Other Teaching Experience: Continuing Education.

b Other Practitioners: Acupuncture, Nursing, Medicine.

c Interdisciplinary: Unique professional position measuring biomechanical, neurophysiological, or contextual factors.

d Other Countries: South Korea, Brazil, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, France, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, Luxembourg, Ireland, Greece, India, and Lebanon.

Panelists’ response rate for each round is provided in Figure 1. Of the seventy-seven eligible experts, 56 individuals completed both questions in the first round. Two individuals were not included as they had a significant number of missing responses which made their data unanalyzable. From the first round, 19 distinct themes were generated representing the priority gaps related to CFs research and FBM. Members of the workgroup agreed on the themes and how they were displayed. In the second round, all 56 participants from the first round responded (100% retention). However, five participants provided partial data, leaving 51 complete data sets. Three other responses had to be excluded due to having substantial missing data. One theme was identified as a duplicate by participants and was eliminated before administering the third round. Out of the 56 participants, 46 (82% retention) participated in round 3. Of these, two submitted partial responses, yielding 44 complete data sets. Round 3 quantitative results are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Consensus agreement of the identified priority gaps in accordance with CREDES [8].

| Survey Item | CS | PAa R3 |

WQR | Outcomeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1: What are the gaps in research with understanding how force-based manipulations work differently with contextual factors? | ||||

|

75 | 97.8 | 0.51 | Agree |

|

71 | 95.6 | 0.61 | Agree |

|

73 | 93.5 | 0.90 | Agree |

|

61 | 87.0 | 0.12 | Agree |

|

57 | 84.8 | 0.57 | Agree |

|

62 | 84.7 | 0.82 | Agree |

|

59 | 8.5 | 0.43 | Agree |

|

45 | 8.5 | 0.70 | Agree |

|

47 | 73.9 | 0.89 | None |

| Question 2: What are the gaps in research in relation to how much of the treatment effect from force-based manipulation is associated with contextual factors? | ||||

|

68 | 95.4 | 0.45 | Agree |

|

67 | 93.1 | 0.40 | Agree |

|

64 | 9.9 | 0.14 | Agree |

|

51 | 84.1 | 0.89 | Agree |

|

53 | 77.3 | 0.55 | Agree |

|

46 | 77.3 | 0.54 | Agree |

|

46 | 77.2 | 0.24 | Agree |

|

52 | 75.0 | 0.65 | Agree |

|

43 | 7.5 | 0.12 | None |

|

32 | 63.6 | 0.12 | None |

Themes listed in simple of percent agreement.

PA; Percent Agreement, WQR; Wilcoxon Rank Sum, CS; Composite Score, R3; Round 3.

aPercent Agreement is the sum of ‘Agree’ and ‘Strongly Agree’ responses.

bOutcome is consensus defined as: ‘Agree’ = PA ≥ 75%, ‘None’ = PA < 75%.

Composite Score defined as: (number of strongly disagree × (−2)) + (number of somewhat disagree × (−1)) + (number of somewhat agree × 1) + (number of strongly agree × 2).

Main result

Question 1

Question 1 investigated the gaps in research with understanding how FBM works differently with CFs. The themes generated, level of agreement, and composite scores are available in Table 2. Eight of the nine themes met consensus. The highest level of agreement involved the need to investigate how different CFs interact with one another following FBM. The next highest ranked themes involved the need to investigate which CFs influence outcomes and the mechanisms by which the CFs influence outcomes. One theme not reaching consensus involved the mechanisms by which FBM influences CFs.

Question 2

Question 2 investigated the gaps in research with understanding how much of the treatment effect from FBM is associated with CFs. The themes generated, level of agreement, and composite scores are available in Table 2. Eight of the 10 themes reached consensus. The highest priority gap identified was the mechanisms by which outcomes are influenced by CFs following FBM. The next highest ranked themes involved the extent outcomes are influenced by CFs following FBM and the need to identify valid measures for determining how CFs influence the outcomes following FBM. Two themes did not reach consensus. One of those themes involved research designs, including control/placebo arms, that can consistently measure outcomes following FBM when CFs are present. The second theme, not reaching consensus, involved the need to better understand how the use of diagnostic terminology influences outcomes following FBM.

Discussion

Main findings

This Delphi study aimed to establish priority gaps related to CFs research and FBM among in international and interdisciplinary context. As a main finding, 16 of 19 themes reached consensus as priority gaps of CFs research and FBM. This outcome underscores the wide agreement among participants involved in the Delphi process, thereby highlighting the credibility and usefulness of this approach for gathering expert perspectives on specific topics within healthcare sciences such as physiotherapy [20].

Question 1

The need to investigate how different CFs interact with each other following FBM emergence as a top-rated topic. This finding highlights the importance of aligning future CFs research with clinical practice, where patients commonly experience multiple CFs simultaneously [21]. Furthermore, this novel element contributes to overcoming the limitations present in current literature which primarily concentrates on single CFs, such as exploring only the effects of positive/negative communication [22] or patient expectations [23] during the administration of FBM.

The panelists also agreed on the need to investigate which CFs influence outcomes and the mechanisms by which the CFs influence outcomes following FBM. In the field of physical therapy, it has been observed that CFs can affect treatment outcomes [24]. Anecdotally, scholars have suggested that among CFs, physical inputs (e.g. touch) may convey more contextual meaning than verbal inputs (e.g. words) or setting inputs (e.g. environment) [25]. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to determine whether some CFs can have a greater impact on patients’ perception compared to others (e.g. treatment rituals during spinal manipulation versus the healthcare setting’s wall color) [25], or how they operate consciously or unconsciously.

Despite the numerous proposed mechanisms of action for explaining how FBM operates [2] there is a lack of consensus among the respondents of this study regarding their influence on CFs. Nevertheless, in light of these findings, further research is needed to delve deeper into this topic.

Question 2

The mechanisms by which outcomes are influenced by CF following FBM represented the highest priority gap. Recent research has put forth several psychobiological theories to explain the mechanisms through which CFs affect clinical outcomes, such as those related to expectancy, classical and operant conditioning, social learning, mind-set, and genetic predisposition [26]. However, further investigation is required to determine which specific mechanism, among those described above, plays a primary role in influencing outcomes after FBM.

The panelist also emphasized the importance of examining the extent outcomes are influenced by CF following FBM. Given that 75% of pain outcomes in knee osteoarthritis can be attributed to these contextual effects [27], it is crucial to prioritize studying which specific outcomes are influenced by CFs and establishing the proportion of therapeutic effects attributable to them [5]. These areas present valuable opportunities for further research on CFs in FBM, enabling differentiation between their effect and other potential confounding variables such as the natural history of the disease or regression to the mean [28].

The need to establish valid measures for determining how CF influences the outcomes following FBM also found consensus among experts. To enhance the study of CFs, it is suggested to measure outcomes not only through self-administered instruments (e.g. questionnaires) but also by incorporating neurophysiological parameters that can provide an objective measure of its effects [24]. Previous studies in this field have begun investigating the role of CFs following CFs by including, for example, mechanical pain sensitivity, thermal pain sensitivity, supra-threshold heat response, and pressure pain thresholds [29]. This direction suggests a potential avenue for future studies to explore further advancements in this area.

One of the themes that failed to achieve consensus involved a gap in research designs, including control/placebo arms, that can consistently measure outcomes following FBM when CF is present. A recent proposal called the CoPPS Statement aims to offer recommendations for researchers while developing, implementing, and reporting of the control interventions used in efficacy and mechanistic trials of physical, psychological, and self-management therapies [30] This statement serves as a valuable resource for scholars seeking direction on incorporating placebo groups also within FBM studies.

While diagnostic terminology represents a CFs that has the potential to impact how patients with musculoskeletal pain perceive their condition [31], our participants did not consider it to be a significant area of research interest. The perceived lack of research priority regarding diagnostic terminology for patients with musculoskeletal pain in our findings’ study raises questions about the current understanding and importance placed on this aspect in FBM.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this Delphi study was its inclusion of a relatively large sampling of panel experts providing international and interdisciplinary perspectives with expertise in CF and FBM. The degree of successful participation at each round resulted in 46 panelists participating in all rounds.

However, there are several limitations to consider. First, in the entire process, we used the English language and some misunderstanding may have influenced the findings; secondly, although conducted rigorously, some priority gaps may have been missed in the process of thematic coding based on commonalities. Third, despite the efforts to be inclusive, some professions and geographical areas are not represented in the process, suggesting that a wider process in the future may be undertaken.

Conclusion

This Delphi provides international and interdisciplinary consensus-based priority gaps in CFs research and FBM. The results of this study can be used to generate future inquiries in CFs and FBM research capable of expanding both the evidence available and the method of investigations used.

Biographies

David Griswold PT, DPT, PhD is a Distinguished Associate Professor in the Department of Graduate Studies in Health & Rehabilitation Sciences at Youngstown State University. He completed his Doctorate of Physical Therapy from Youngstown State University and his Doctorate of Philosophy in Physical Therapy from Nova Southeastern University. He has more than 10 peer-reviewed publications in manual therapy and dry needling and is a national speaker and instructor in dry needling.

Ken Learman, PT, PhD, FAAOMPT is a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Graduate Studies in Health & Rehabilitation Sciences at Youngstown State University. He is the director for the Doctorate in Health Sciences along with teaching EBP and orthopedic manual therapy in the DPT program. With 34 years of OMT experience, he is a senior deputy editor for the Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy and has served as a reviewer for more than a dozen other journals. He has published over 40 manuscripts, 7 book chapters and co-edited an orthopedic cases textbook.

Giacomo Rossettini, PhD, PT, is a clinical physiotherapist, researcher, and lecturer from Italy. He earned his PhD at the Department of Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health - University of Genova in 2018, with a thesis on “Contextual Factors, Placebo And Nocebo Effects In Physical Therapy: Clinical Relevance And Impact On Research”. Giacomo Rossettini is the author of over 70 peer-reviewed publications in physiotherapy journals. He has given over 60 presentations at universities and national and international conferences. His didactic, clinical, and scientific interests concern the field of musculoskeletal rehabilitation, with an emphasis on placebo and nocebo effects, contextual factors, patient’s expectation and preferences.

Alvisa Palese, RN, MNS, PhD. She is Full Professor in Nursing, at serves as the Dean of the Bachelor of Nursing Science, and in the Master of Nursing and Midwifery Sciences, in Udine University and Udine/Trieste University Italy. She completed her Doctor of Nursing Science in Hull (UK). She published over than 400 peer reviewed journal articles and passionate in research.

Edmund Ickert PT, DPT, PhD, CLT serves as an Assistant Professor in the Doctor of Physical Therapy Program at Youngstown State University. He completed his Doctor of Physical Therapy and Doctor of Philosophy in Health Sciences from Youngstown state University in Ohio. Dr. Ickert’s scholarship includes over 5 peer reviewed journal articles and he has served as a peer reviewer for multiple journals.

Mark Wilhelm PT, DPT, PhD, serves as the Director of Admissions and Associate Professor in the Doctor of Physical Therapy Program at Tufts University School of Medicine. He completed his Bachelor of Science in Exercise Science from the University of Akron, his Doctor of Physical Therapy from Walsh University in Ohio, and his Doctor of Philosophy in Rehabilitation Sciences from Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Dr. Wilhelm’s scholarship includes over 20 peer reviewed journal articles and he has co-authored two book chapters.

Chad Cook PT, PhD, FAPTA is a Professor in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery in Duke University. He also has appointments in Population Health Sciences and the Duke Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Cook is an NIH and DoD funded researcher and is the Director of the Duke Center of Excellence in Manual and Manipulative Therapy.

Jennifer Bent, MPT, CMTPT, OCS, FAAOMPT is a board-certified orthopedic physical therapist with over 10 years of experience in the management of acute and chronic musculoskeletal conditions at Duke University Healthcare System using a contemporary approach to rehabilitation. She completed her Bachelor of Science in Exercise Science with a minor in Sport Coaching from UNC-Greensboro, her Master’s degree in Physical Therapy from Winston Salem State University. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopedic Manual Therapists and a graduate of the Myopain Seminar Series.

Funding Statement

No funding sources to disclose.

Disclosure statement

David Griswold teaches continuing education seminars in manual therapy and dry needling.

Chad Cook is the Director of the Center of Excellence in Manual and Manipulative Therapy at Duke University, and a portion of his salary is supported by that role. Chad published a book on OMT and a course with AGENCE EBP on Manual Therapy in which he receives royalties. He is also a consultant for the Hawkins Foundation, Zimmer Biomedical, and Akron Children’s.

Giacomo Rossettini leads education programs on placebo, nocebo effects and contextual factors in healthcare to under- and post-graduate students along with private CPD courses.

References

- [1].National Institutes of Health . Neural Mechanisms Of Force-Based Manipulations: High Priority Research Networks (U24 Clinical Trial Optional). National Institutes Of Health (HHS-NIH11); 2021. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-AT-21-006.html. Accessed July, 2023.

- [2].Bialosky JE, Beneciuk JM, Bishop MD, et al. Unraveling the mechanisms of manual therapy: modeling an approach. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018. Jan;48(1):8–18. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.7476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].O’Keeffe M, Purtill H, Kennedy N, et al. Comparative effectiveness of conservative interventions for nonspecific chronic spinal pain: physical, behavioral/psychologically informed, or combined? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2016. Jul;17(7):755–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.01.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Damian K, Chad C, Kenneth L, et al. Time to evolve: the applicability of pain phenotyping in manual therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2022. Apr;30(2):61–67. doi: 10.1080/10669817.2022.2052560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rossettini G, Carlino E, Testa M.. Clinical relevance of contextual factors as triggers of placebo and nocebo effects in musculoskeletal pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018 Jan 22;19(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-1943-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dissing KB, Vach W, Hartvigsen J, et al. Potential treatment effect modifiers for manipulative therapy for children complaining of spinal pain.Secondary analyses of a randomised controlled trial. Chiropr Man Therap. 2019;27(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12998-019-0282-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Burns JW. Mechanisms, mechanisms, mechanisms: it really does all boil down to mechanisms. Pain. 2016. Nov;157(11):2393–2394. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Junger S, Payne SA, Brine J, et al. Guidance on conducting and REporting DElphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017. Sep;31(8):684–706. doi: 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Iqbal SP-Y. The Delphi method. Psychologist. 2009;22(7):598–601. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vogel C, Zwolinsky S, Griffiths C, et al. A Delphi study to build consensus on the definition and use of big data in obesity research. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019. Dec;43(12):2573–2586. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0313-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nasa P, Jain R, Juneja D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: how to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. 2021 Jul 20;11(4):116–129. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cook CE, Bailliard A, Bent JA, et al. An international consensus definition for contextual factors: findings from a nominal group technique. Frontiers In Psychology. 2023;14:1178560. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1178560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Keeney S, McKenna H, Hasson F. He Delphi technique in nursing and health research. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2011. doi: 10.1002/9781444392029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Norman Dalkey OH. An experimental application of the DELPHI method to the use of experts. Manage Sci. 1963;9(3):458–467. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.9.3.458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi method. MA: Addison-Wesley Reading; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- [16].DeCastellarnau A. A classification of response scale characteristics that affect data quality: a literature review. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1523–1559. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0533-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, et al. Standardised method for reporting exercise programmes: protocol for a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2014 Dec 30;4(12):e006682. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Henderson EJ, Rubin GP. Development of a community-based model for respiratory care services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012 Jul 9;12(1):193. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014. Apr;67(4):401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Requejo-Salinas N, Lewis J, Michener LA, et al. International physical therapists consensus on clinical descriptors for diagnosing rotator cuff related shoulder pain: a Delphi study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2022. Mar-Apr;26(2):100395. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2022.100395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sherriff B, Clark C, Killingback C, et al. Impact of contextual factors on patient outcomes following conservative low back pain treatment: systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2022 Apr 21;30(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s12998-022-00430-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Malfliet A, Lluch Girbes E, Pecos-Martin D, et al. The influence of treatment expectations on clinical outcomes and cortisol levels in patients with chronic neck pain: an experimental study. Pain Pract. 2019. Apr;19(4):370–381. doi: 10.1111/papr.12749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bishop MD, Mintken PE, Bialosky JE, et al. Patient expectations of benefit from interventions for neck pain and resulting influence on outcomes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(7):457–465. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Testa M, Rossettini G. Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: how contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes. Man Ther. 2016. Aug;24:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Newell D, Lothe LR, Raven TJL. Contextually Aided Recovery (CARe): a scientific theory for innate healing. Chiropr Man Therap. 2017;25(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12998-017-0137-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rossettini G, Camerone EM, Carlino E, et al. Context matters: the psychoneurobiological determinants of placebo, nocebo and context-related effects in physiotherapy. Arch Physiother. 2020;10(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s40945-020-00082-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zou K, Wong J, Abdullah N, et al. Examination of overall treatment effect and the proportion attributable to contextual effect in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016. Nov;75(11):1964–1970. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cashin AG, McAuley JH, Lamb SE, et al. Disentangling contextual effects from musculoskeletal treatments. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021. Mar;29(3):297–299. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gallego-Sendarrubias GM, Voogt L, Arias-Buria JL, et al. Can patient expectations modulate the short-term effects of dry needling on sensitivity outcomes in patients with mechanical neck pain? a randomized clinical trial. Pain Med. 2022 May 4;23(5):965–976. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hohenschurz-Schmidt D, Vase L, Scott W, et al. Recommendations for the development, implementation, and reporting of control interventions in efficacy and mechanistic trials of physical, psychological, and self-management therapies: the CoPPS statement. BMJ. 2023 May 25;381:e072108. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stewart M, Loftus S. Sticks and stones: the impact of language in musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018. Jul;48(7):519–522. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.0610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]