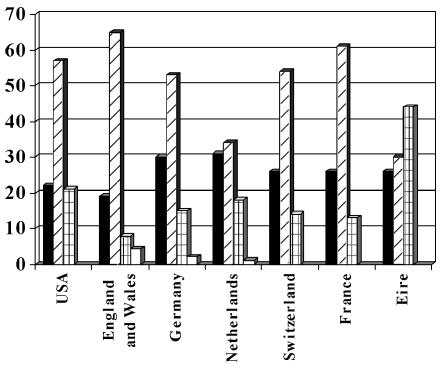

July 2004 saw the publication of two important documents in palliative care—the World Health Organization's Palliative Care: the Solid Facts1 and, in the UK, a report from the House of Commons Select Committee on Health.2 Both highlight a gap between patients' expressed wishes about where they should be cared for and die and what actually happens. There is consistent evidence showing that well over 50% of patients would choose to die at home.3 Yet in many countries hospitals are the places where most people come to the end of life, and the percentage for England and Wales stands out as particularly high (Figure 1). The average proportion favouring home conceals substantial variation between studies but the differences seldom favour hospitals. In some, the proportion expressing preference for death at home has been as high as 80–90%.4,5 However, when hospices are brought into the equation, the perspective may change: in a longitudinal study in the North West of England, only 36% favoured home and 32% had an equal preference for home or hospice.6 Is greater choice in this matter a realistic aim? The Select Committee, while expressing support for the aspiration to allow all patients to die at home if they choose, declared that the option 'will only be realisable if there is a guarantee of 24-hour care and support, with back-up from appropriate specialists'.

Figure 1.

Preliminary data on place of death by country. ▪Home;  Hospital;

Hospital; Nursing home; □Inpatient hospice. [Source: Palliative Care: the Solid Facts, WHO 2004 (1)]

Nursing home; □Inpatient hospice. [Source: Palliative Care: the Solid Facts, WHO 2004 (1)]

Data from the UK Office for National Statistics suggest that home deaths in patients with cancer are not rising but falling—27% in 1994, 22% in 2001—and such a widening of the gap between preference and reality is hardly what we would expect at a time when Government policy is to give patients more choice. Some may say that it is too soon for these policy efforts to have impact; others that insufficient Government funds have been assigned to this purpose. Whatever the answer, we seem at present to be failing patients in a fundamental aspect of healthcare.

To echo the Parliamentary Select Committee, can we realistically aim to meet patients' wishes on this matter? Clinicians, researchers and policy-makers need to look at three issues. First, the 'contextual' factors that hamper or facilitate home death operate as part of a complex web of clinical circumstances (including quality and quantity of resources), personal preferences, demographic determinants, and informal support networks. Moreover, contextual conditions are not static. They change as the disease progresses: clinical conditions usually get worse while resources for care tend to become eroded as time passes. Thus healthcare support needs to be increased over time to meet needs for care at home, and contextual factors become increasingly relevant to preferences, intentions and decisions—not just for patients but also for families and clinicians. When plans are made for palliative care these patterns of decline have to be recognized.

Second, are we making the best possible use of resources that already exist? Take community hospitals— the subject of the article by Professor Payne and colleagues on p. 428 of this issue.7 This report indicates that many community hospitals do possess the necessary professional expertise, though special beds are commonly lacking and few have written policies on palliative care. These aspects could be developed. Unlike district general hospitals, community hospitals can offer continuity of care by general practitioners and (sometimes) accommodation for families. They also represent a means to reach out to groups at present under-served—for instance, those living in rural areas, those with non-malignant diseases, and the old. Another resource is the informal carer, who often provides critical support. The Select Committee, looking at experience in Canada, wishes the Government to consider paid time off work for carers, on the lines of maternity leave. This idea, which would need careful evaluation before legislation, might offer a creative and fair means to nurture informal support networks.

Third, there are crucial gaps in our understanding of how a preference is formed, how and why it changes, and how to organize care to meet it. Of the many studies on people's preferences regarding place of care and death, most have been cross-sectional, assessing preferences at a specific point in time, usually during hospital admission. The few longitudinal investigations suggest that choices change over time, shifting slightly from home towards hospital death.6,8 People adjust their choices and renegotiate their priorities, and five aspects seem particularly influential in shaping patients' and carers' preferences regarding place of death—informal care resources; symptoms and physical management; patients' experiences of services and environments; existential perspectives; and quality of life.6,9,10 For many patients one of the greatest tensions arises from worry about being a burden to others yet wanting to be with them.9 On the matter of experiences, it must be recognized that an expressed preference for home care/death may not always be a positive judgment based on the 'intrinsic' qualities of a home environment. The decision may be driven by negative impressions of other care environments; thus, the gap between wishes and reality might be narrowed in the other direction, by attention to care environments other than home. Equally, the shift over time away from home care may be brought about by failings in care while patients are at home. A host of factors bear on these decisions, including cognition, emotions and social expectations.11

There will always be unknown variables, but we urgently need a better understanding of patients' priorities on place of death and why they sometimes change their minds. Meanwhile, choices—for home or hospice or community hospital or hospital—must be respected as far as possible. New initiatives such as wider use of community hospitals and paid leave for carers deserve rigorous investigation. The place of end-of-life care and death is just one of the many choices in which clinicians struggle to involve patients and carers. If we could find better ways to resolve these issues, we would probably be helped in coping with other perplexing choices, such as those on timing of care and treatment. 'Meeting individual preferences should be the ultimate measure of success.'1

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Palliative Care: the Solid Facts. [http://www.euro.who.int] (accessed 2 August 2004)

- 2.House of Commons HC. Palliative Care: Fourth Report of Session 2003–04.2004. [www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/health_committee.cfm] (accessed 2 August 2004)

- 3.Higginson I, Sen-Gupta G. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic review of patient preferences. J Pall Med 2000; 3: 287-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang ST, McCorkle R. Determinants of congruence between the preferred and actual place of death for terminally ill cancer patients. J Pall Care 2003;19: 230-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiernan E, O'Connor M, O'Siorain L, Kearney M. A prospective study of preferred versus actual place of death among patients referred to a palliative care home-care service. Ir Med J 2002;95: 232-5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas C, Morris SM, Clark D. Place of death: preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 2004;58: 2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payne S, Keer C, Hawker S, et al. Community hospitals: an under-recognized resource for palliative care. J R Soc Med 2004;97: 428-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Townsend J, Frank AO, Fermont D, et al. Terminal cancer care and patients' preference for place of death: a prospective study. BMJ 1990;301: 415-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray MA, O'Connor AM, Fiset V, Viola R. Women's decision-making needs regarding place of care at end of life. J Pall Care 2003;19: 176-84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang ST. When death is imminent: where terminally ill patients with cancer prefer to die and why. Cancer Nurs 2003;26: 245-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martineau I, Blondeau D, Godin G. Choosing a place of death: the influence of pain and of attitude toward death. J Appl Soc Psychol 2003; 33: 1973-93 [Google Scholar]