Abstract

We review literature related to the assessment and identification of Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) and Intellectual Disabilities (ID). SLD and ID are the only two disorders requiring psychometric test performance for identification within the group of neurodevelopmental disorders in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – 5. SLD and ID are considered exclusionary of one another, but the processes for assessment and identification of each disorder vary. There is controversy about the identification and assessment methods for SLD, with little consensus. Unlike ID, SLD is weakly related to full-scale IQ, and there is insufficient evidence that the routine assessment of IQ or cognitive skills adds value to SLD identification and treatment. We have proposed a hybrid method based on the assessment of low achievement with norm-referenced tests, instructional response, and other disorders and contextual factors that may be comorbid or contraindicative of SLD. In contrast to SLD, there is strong consensus for a three-prong definition for the identification and assessment of ID: (a) significantly subaverage IQ, (b) adaptive behavior deficits that interfere with independent living in the community, and (c) age of onset in the developmental period. For both SLD and ID, we identify areas of controversy and best practices for identification and assessment.

Keywords: specific learning disabilities, intellectual disability, intelligence testing, IQ-discrepancy, patterns of strengths and weaknesses, response to intervention

Specific learning disabilities (SLD) and intellectual disabilities (ID) are part of the group of neurodevelopmental disorders in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – 5 (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Other neurodevelopmental disorders in DSM-5 include communication disorders, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and motor disorders. Neurodevelopmental disorders typically arise early in development and represent impairments of language, academic skills, social skills, intelligence, and adaptive behavior that are usually viewed as secondary to brain impairment but with prominent environmental risk factors.

In this article, we focus first on the assessment of SLD and then on ID. For SLD, we will explain why assessment procedures and identification are controversial, with no clearly established guidelines. After reviewing the empirical evidence for different approaches to the assessment and identification of SLD, we summarize an assessment and identification approach that we term a hybrid approach because it combines components of identification approaches consistent with findings from classification and measurement research (Fletcher et al., 2019). In contrast to SLD, there is a strong consensus about the assessment and identification of ID. We will present this consensus, relying on published, peer-reviewed guidelines from the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD; 2020) and the DSM-5 (APA, 2013).

It is appropriate to consider the assessment of SLD and ID in the same article because they are the only neurodevelopmental or childhood disorders in DSM-5 that require psychometric performance tests (e.g., achievement tests, IQ tests). In addition, they are exclusionary of one another in DSM-5 and under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which provides statutory guidance for school-based disability identification and services in the United States. Unlike other neurodevelopmental disorders, SLD and ID are not examples of co-occurring disorders (i.e., comorbidity) and differences in IQ and adaptive behavior help differentiate them. Historically, the identification of both disorders has required an assessment of IQ. However, SLD status is weakly related to IQ and the role of IQ testing as part of the identification process is controversial (Fletcher & Miciak, 2017; Siegel, 1992; Stanovich & Siegel, 1994). In contrast, intellectual deficits are a prominent part of the definition of ID, and assessment of IQ is necessary for ID identification but not sufficient (AAIDD, 2020). Adaptive behavior impairment is also a defining characteristic of ID that is at least equally weighted with IQ (APA, 2013), representing pervasive areas of difficulty sufficiently severe to prevent independent functioning in the community without support. Adaptive impairment in SLD is narrow and restricted to domains influenced by the development of reading, math, and writing skills (Bradley et al., 2002). The adaptation difficulties do not result in a general lack of independence or difficulty performing activities of daily living without support. The difference in adaptive functions is critical for accurate identification because some children with SLD perform close to the range of ID on IQ tests. Thus, assessment of adaptive behavior may be important for differentiating SLD and ID.

Specific Learning Disabilities

SLD is a highly prevalent disorder that represents a heterogeneous group of difficulties with the development of academic skills involving reading, mathematics, and writing. In the DSM-5, SLD replaced academic skills disorders first introduced in DSM-III and maintained in DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR. Historically, SLD is closely linked with ADHD and the concept of brain-based behavior disorders (Rutter, 1982). This conceptualization was important because it reduced the focus on SLD and ADHD as disorders that had largely environmental etiologies involving parenting, motivation, and psychopathology.

At one point, what we now call SLD and ADHD were lumped together as a group of heterogeneous conditions under terms like “minimal brain dysfunction” to emphasize the origins in the brain (Clements, 1966). However, the range of behavior was too broad to be useful, especially for assessment and treatment. In 1980, the DSM-III dropped “minimal brain dysfunction” and separated academic skills disorders (i.e., SLD) from ADHD while recognizing that these are often comorbid conditions requiring comprehensive treatment plans that address both learning and behavioral impairments.

Not surprising because SLD affects how well children perform in school, SLD also has origins in education with little involvement of the DSM-5. Kirk (1963) first used the term “learning disability” to refer to children who had unexpected difficulties learning to read, write, and do math. He emphasized that children with SLD often had strengths in nonacademic domains, learned differently from children with intellectual and behavioral difficulties, and that the difficulties were due to intrinsic factors involving the brain and not to environmental factors like motivation. Kirk argued that children with SLD needed specialized educational programs.

In 1975, the U.S. Congress passed Public Law 94–142, which required schools to provide free and appropriate public education for all children, including children identified with SLD and ID, and provided funds for special education programs (U.S. Office of Education [USOE], 1977). Before Public Law 94–142, many children with SLD, ID, and other neurodevelopmental disorders were not allowed to attend school or were simply allowed to fail, viewed as intellectually or motivationally impaired. Now all schools are required to find children with SLD and provide specialized intervention programs and accommodations under the IDEA. SLD is 1 of 13 separate categories of eligibility for special education in the most recent reauthorization of IDEA (US Department of Education, 2006), accounting for about a third of all children presently served under IDEA. Colleges are also required to provide accommodations for students with neurodevelopmental disorders under the Americans with Disabilities Act, although there is no proactive obligation to find and identify students with SLD, as under IDEA. Instead, secondary students must self-report their disability status.

Many other developed countries have similar programs for SLD. In many respects, IDEA (and similar international educational laws) has more influence on the assessment and identification of SLD than DSM-5, although neither is specific in terms of methods or approach. We will focus on the DSM-5 because of the charge for this special issue but bring up issues involving IDEA when appropriate.

Diagnosis, Identification, and Clinical Features

Exactly how to assess and identify SLD has been controversial, although there is broad consensus that SLD exists and leads to narrow difficulties with adaptation (Bradley et al., 2002). Part of the problem is that there is no “gold standard” for SLD; it is a latent construct that can be observed only in terms of how its manifestations are measured. There are multiple approaches to measurement depending on the conceptual model for understanding SLD (Fletcher et al., 2019).

In the DSM-5 (and IDEA), the primary characteristic is low achievement in reading, math, and/or writing. These areas can include difficulty (a) accurately reading and spelling words (basic reading, or dyslexia); (b) poor understanding of what is read despite adequate basic reading skills (specific reading comprehension disability); (c) difficulties with math calculations, representing a computational problem that involves number sense and math facts (dyscalculia); (d) difficulties with math reasoning, usually manifested in word problem difficulties; and (e) difficulties with writing that include the mechanical aspects of putting words on paper (dysgraphia) or compositional difficulties due to organizational and/or language problems.

The second feature of DSM-5 is persistence: difficulties in the development of academic skills persist despite receiving adequate instruction. In many situations, children with SLD are not identified until later in school and do not receive instruction in reading, math, and/or writing that is tailored to their needs. It is difficult to separate SLD from academic problems due to inadequate instruction, which might include ineffective general education classroom instruction and/or remedial instruction. IDEA requires evidence of adequate instruction in reading and math.

The third feature in DSM-5 is the age of onset. SLD involving basic reading, math, and writing skills typically develop early in schooling, although exceptions exist. If the SLD is specific to reading comprehension or written expression for stories and essays, it may become apparent later in school (Catts et al., 2012). However, SLD in any domain is often not identified until later in elementary and middle school, when academic deficits become more pronounced in comparison to typically developing peers.

The fourth feature in DSM-5 (and IDEA) represents exclusionary factors (i.e., absence of conditions or contextual factors that presumably contraindicate SLD). Although slightly different in the DSM-5 and IDEA, these factors include ID, uncorrected vision or hearing problems, behavioral or neurological conditions, psychosocial adversity, lack of proficiency in the language of instruction, sociocultural factors, and inadequate instruction. Differentiating academic problems associated with behavioral/ neurological conditions, psychosocial adversity, and inadequate instruction is difficult because the academic problems present similarly and the exclusionary condition may be comorbid.

Per the DSM-5, these features are evaluated through the administration of tests of academic achievement, a developmental history, and school reports involving performance, behavior, and instructional approaches. These evaluations are commonly completed by schools but are also conducted by professionals outside of schools identifying as child psychologists, neuropsychologists, speech pathologists, or school psychologists. Schools often use formulae that determine the severity of academic impairment required for special education services and for IDEA may involve discrepancies of achievement relative to measured intelligence or unevenness in performance on tests of cognitive skills. There is little empirical support for these methods of identification, which is why they are not included in DSM-5. Other assessments may be needed to address contraindicative problems, comorbid conditions, and contextual factors as presumptive causes of low achievement (Fletcher et al., 2019).

Children with SLD may have impairments in more than one academic domain. For example, a child who has problems with reading and spelling words (dyslexia) typically has co-occurring problems with reading comprehension and writing. Children with reading problems often struggle with math. Many identified with SLD have problems in all three domains. In the DSM-5 (and IDEA), SLD can be coded for each domain that is impaired in reading (word reading accuracy, reading fluency, reading comprehension); written expression (spelling, grammar and punctuation, organization of written products); and mathematics (number sense, math facts, accurate and/or fluent calculation, and accurate math reasoning). The DSM-5 also requires an onset of at least 6 months, evidence of adaptive impairment, and notes that while SLD originates in childhood, the magnitude may not be apparent until more complex demands are made, such as the need to read complex material (Catts et al., 2012). The onset and adaptive impairment requirements are not explicitly required for identification under IDEA, but IDEA does require evidence of educational need.

Comorbidity

There is significant co-occurrence of SLD involving reading, math, and writing. Moll et al. (2014) reported that 30% to 50% of children with SLD had shared deficits in more than one academic domain. This is likely because the cognitive skills that underlie different academic skills overlap and can create problems in multiple areas, especially if language and working memory are factors.

Children with SLD also commonly show comorbidity with other disorders, especially ADHD. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) report from the National Survey of Children’s Health found that 13.8% of children aged 3 to 17 years had been diagnosed with either SLD or ADHD. Of these children, 4.2% were diagnosed only with SLD, 6% with ADHD only, and 3.6% with both SLD and ADHD (Zablonsky & Alford, 2020). Comorbidity estimates are best developed for children having problems with basic reading (dyslexia). Depending on whether the sample is derived from a clinic or a research sample, estimates of comorbidity range from 30% to 60% (Willcutt et al., 2007). In addition to ADHD, another common comorbidity is early problems with the development of oral language. About half of children identified with dyslexia show more general impairments of language (Pennington & Bishop, 2009). About 25% of children with dyslexia experience an internalizing behavior problem, and another 25% experience an externalizing behavior problem, in part reflecting ADHD comorbidity (Willcutt et al., 2007). Longitudinal studies show long-term associations between first-grade performance in reading and math and subsequent problem behaviors in adolescence, which most frequently manifest as aggressive behaviors for adolescent boys and mood problems for adolescent girls (Kellam et al., 1994). Although there are fewer studies of math and writing SLD, the same patterns are apparent, especially associations with ADHD (Willcutt et al., 2013).

The consideration of comorbidity is important for assessing SLD. Although SLD is referred to as specific, this term should be understood to refer to the primacy of the impairment of academic skills and the narrow impairment of adaptive behavior. In addition to overlapping cognitive effects, frequent comorbidity raises questions about whether single deficits in cognitive skills can fully account for SLD even when limiting to a single domain, such as dyslexia (Pennington, 2006). Although some cognitive skills have strong associations with specific academic domains, a single-deficit model does not seem adequate to account for all cases. Thus, Pennington (2006) proposed multiple deficit models to more fully capture how cognitive skills are expressed in academic deficits. Behavioral genetic studies show overlap in the heritability of reading and math SLD and ADHD. However, the overlap in heritability was much higher for reading and math SLD than for ADHD, suggesting that the common contribution of genes to reading and math SLD is much higher than with ADHD (Daucourt et al., 2020). According to the continuity hypothesis (Plomin & Kovas, 2005), there are genes that are specific to each type of disorder. However, there are also generalist genes that overlap across disorders. This view reflects the idea that the traits that underlie SLD represent correlated liabilities that are dimensional because shared risk variants are expressed to different degrees depending on academic proficiency and environmental influences, such as instruction. No child should be evaluated for SLD without considering comorbidity because treatment plans that only address academic deficits and do not consider comorbidities or contextual factors are less likely to produce a strong intervention response.

Specific Attributes of SLD

The assessment of SLD can be challenging because there is no strong consensus on its definition, on how psychological performance tests should be used, and because SLD often occurs with other difficulties in academics, behavior, and attention (see comorbidity above; Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014). The attributes of SLD to be measured may include IQ, cognitive skills, academic achievement, and instructional response. The problem of definition is partly due to the dimensional nature of these attributes (Ellis, 1984). In a dimensional disorder, the attributes (e.g., low achievement and instructional response) are not categorical but occur on unbroken continua as part of a normal distribution. There is no natural cut point to distinguish those with SLD from low achievers without SLD. As such, thresholds for low achievement or inadequate instructional response are somewhat arbitrary unless they are very severe (Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014). Below, we will discuss the consequences of dimensionality for the assessment of SLD.

The DSM-5 does not provide specific guidelines for the assessment of SLD. However, IDEA provides more explicit guidelines without specifying preferences for different methods or specific assessment procedures other than general guidelines for reliability, validity, and cultural appropriateness. The IDEA criteria for SLD identification are summarized in Table 1 (US Department of Education, 2006, p. 46786). There are eight domains of academic achievement in which SLD can occur and like the exclusionary criteria, are similar to DSM-5, except that oral expression and listening comprehension are not considered SLD in DSM-5. This exclusion is reasonable because oral expression and listening comprehension are not academic skills and are better-considered examples of communication disorders. These domains remained in IDEA because the Federal statutory definition of SLD, which has been unchanged since 1975 and Public Law 94–142 includes speaking and listening as examples of impairment. In practice, these domains are often not formally assessed when evaluating SLD (Fletcher et al., 2019).

Table 1.

IDEA Regulations for the Identification of Specific Learning Disabilities (US Department of Education, 2006, p. 46786).

A State must adopt … criteria for determining whether a child has a specific learning disability … In addition, the criteria adopted by the State:

|

A major difference between IDEA and DSM-5 is the indication in the second criterion of different identification methods in Table 1 that can be based on (a) “the child’s response to scientific, research-based intervention,” commonly referred to as Response to Intervention (RTI); or (b) “a pattern of strengths and weaknesses in performance, achievement, or both, relative to age, State-approved grade-level standards, or intellectual development.” (IDEA, 2006, 34 CFR §300.309). The most common approaches under the second criterion are (a) IQ-achievement discrepancy methods, which gained prominence in the 1977 guidelines for SLD for implementing Public law 94–142 (USOE, 1977) and (b) pattern of strengths and weaknesses (PSW) methods that were intended to replace IQ-achievement discrepancy methods by assessing cognitive and achievement skills more broadly. Both general methods include the use of formulae for defining significant discrepancies in some index of cognitive strength and an achievement weakness (weighted equally) with no consensus on the size of the discrepancy needed to indicate clinical significance. The most common is one standard deviation (which does not correct for the correlation of IQ and achievement, leading to regression to the mean; Reynolds, 1984–1985) or one standard error of measurement. We will term these latter approaches “cognitive discrepancy” methods and the former “instructional response” methods. The difference in the methods reflects different conceptualizations of the indicators of unexpected low achievement for SLD.

Reliability Issues Are Universal for SLD Identification Methods

All SLD identification methods have problems with reliability for individual identification. The tests that are used are typically highly reliable but have small amounts of measurement error. When imperfectly reliable tests are used to assess a firm threshold on a normal distribution, there will be fluctuations of individual children around the threshold if measurement error is not considered (Francis et al., 2005). In addition, different evaluations use different tests with different normative samples so that different assessments do not identify the same people with SLD or not-SLD even when the same method is used (Macmann et al., 1989).

This unreliability at the individual level is apparent across multiple methods and approaches to identification, including methods based on IQ-achievement discrepancies (Francis et al., 2005; Macmann & Barnett, 1985), patterns of cognitive strengths and weaknesses (Miciak et al., 2015, 2018; Taylor et al., 2017), and instructional response (Barth et al., 2008; Fletcher et al., 2014; Hendricks & Fuchs, 2020). Even seemingly straightforward methods that employ a single low achievement criterion (i.e., reading scores < 20th percentile) demonstrate fluctuation in individual identification decisions over time and across tests (Francis et al., 2005). If a formula or firm threshold is used, a student identified with one method may not be identified with SLD using another formula because of differences in tests, testing occasion, the threshold for identification, or how the discrepancy is defined.

If multiple tests within the same achievement domain are administered, and they are consistently below the threshold to mark an academic difficulty, we can be more confident that the student’s true score is below the threshold (Fletcher et al., 2014). Even better, the standard error of measurement of the test could be specified and represented as a confidence interval (as in assessments for ID) so that a range of scores could indicate the presence of SLD. Other data that might inform a clinical judgment of SLD could be utilized, but there is little research on how to incorporate this information reliably and some efforts are not promising because of the excessive influence of psychometric tests (Maki et al., 2022). These data could include previous academic and classroom performance, grades, observations of the child, and the parents’ and teacher’s perceptions of the student’s performance. The bottom line is that assessment and identification of SLD requires multiple, converging data and is not reliable at the individual level if identification relies only on psychometric tests and firm thresholds.

With this understanding of the reliability issue in hand, we turn to validity issues for cognitive discrepancy and instructional response methods. Here we focus on group comparisons of the proposed classification hypothesis where the reliability of individual identification decisions is less of an issue. The premise is that for an identification method to be valid, it must differentiate people the method defines as SLD and not-SLD on important attributes not used as part of the definition, such as cognition, behavior, or future treatment response (Morris & Fletcher, 1988).

Validity of SLD Identification Methods

Cognitive Discrepancy Methods.

There is a long history of research on the role of cognitive skills in SLD. Academic skills themselves are complex cognitive skills strongly related to domain-general and domain-specific cognitive skills. Such cognitive skills are frequently represented as proximal causes of SLD (Johnson et al., 2010; Vellutino et al., 2000), although these relations are correlational, not causal. The cognitive correlates of different types of SLD do vary with the academic skills that are impaired, reflecting the rich history of research on cognition and achievement (Grigorenko et al., 2020). This variation is depicted in Figure 1. This figure was developed by composing samples of 8- to 9-year-old children who met different definitions of SLD (IQ-discrepancy and simple low achievement <26th percentile, but not discrepant with IQ) in basic reading (Dyslexia) and math computations (math). All children had a verbal or performance IQ of at least 80. The typically developing group scored above the 25th percentile in reading and math and did not meet the criteria for ADHD, which is why they tend to score above average. Figure 1 shows cognitive profiles across measures associated with SLD in basic reading (dyslexia) and math (dyscalculia). These SLD subgroups are different in the pattern of cognitive skills (Fletcher et al., 1994).

Figure 1.

Cognitive Profiles for Children Who Are Only Impaired in Reading (RD) and in Math (MD) Relative to Typical Achievers (NL).

Note. The groups differ in shape and elevation, suggesting three distinct groups. From Fletcher et al. (2007). Reprinted with permission.

This observed pattern of variation is the premise on which cognitive discrepancy methods are based, seeking to document this pattern of strengths and weaknesses in cognitive and academic skills. However, the evidence that assessing this variation in cognitive skills independent of the academic domain contributes meaningful evidence for identification or treatment is weak. We will not discuss these relations in depth, but many sources have detailed expositions (Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014; Fletcher et al., 2019). There are five general principles. First, SLD is associated with weaknesses in specific processes rather than global intellectual impairment. Second, the cognitive components of SLD are dimensional and occur on a normally distributed continuum of ability. This is important because understanding typical development informs our understanding of atypical development, and vice versa; there is no need for separate theories of the typical development of academic skills and their manifestations in SLD. Third, each academic and cognitive component has overlapping, but distinct signatures in the genome and in the brain. The unique features support the validity of classifying SLD according to the area of academic impairment (Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014; Fletcher et al., 2019). Fourth, the overlap of cognitive skills across SLD partially explains comorbid associations (Willcutt et al., 2013). Finally, cognitive deficits that are strongly related to SLD (e.g., phonological processing deficits or deficits in working memory), like their academic manifestations, are chronic and lifelong in the absence of intervention (Cirino et al., 2005).

IQ-Achievement Discrepancy Methods.

The role of intelligence and IQ testing has a long history of controversy in research and practice on SLD. At one point, IQ tests were used to gauge the potential of a child for learning. For example, Burt (1937) stated, “Capacity must obviously limit content. It is impossible for a pint jug to hold more than a pint of milk and it is equally impossible for a child’s educational attainment to rise higher than his educable capacity” (p. 477). In this view, an IQ test is a measure of learning aptitude where IQ sets an upper limit on a child’s capacity to master academic skills. Termed “milk and jug” thinking (Share et al., 1989), there is little evidence that IQ scores truly function as indicators of aptitude. Rather, they are a less direct assessment of achievement that often declines over time in children with SLD because of impaired access to content learning when reading is involved (Bentum & Aaron, 2003). Nonetheless, IQ testing was at one point routine in assessments for the identification of SLD. From 1977 to 2004, U.S. federal regulations for the identification of SLD under IDEA required documentation of a significant discrepancy between higher IQ and lower achievement scores.

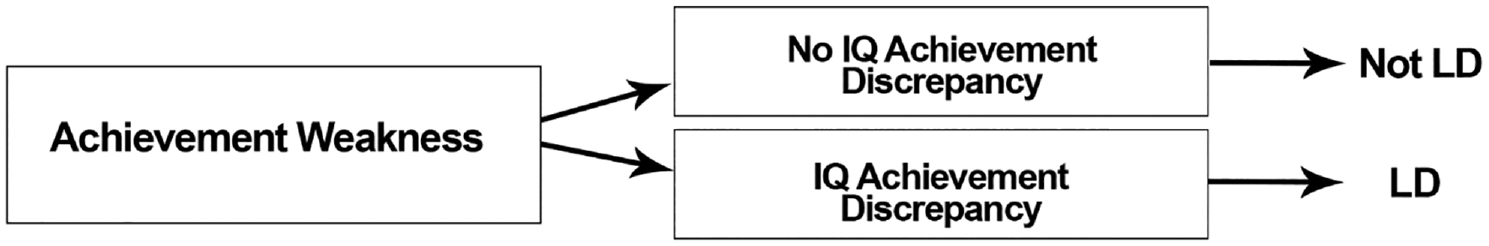

Figure 2 illustrates the framework for using an IQ-discrepancy method to differentiate people with putative SLD and low achievers who presumably are achieving at expected levels. There is extensive research on the validity of IQ-achievement discrepancy methods. This research shows that it is difficult to differentiate groups of children who meet IQ-discrepancy definitions from low achievers without a discrepancy in measures not used to define the groups. The low achiever groups do not include children with ID, but scores can range up to two standard deviations around the mean. These largely null results have been reported on external measures of achievement and cognitive skills in large studies (Fletcher et al., 1994; Siegel, 1992; Stanovich & Siegel, 1994) and two large-scale meta-analyses (Hoskyn & Swanson, 2000; Stuebing et al., 2002). Figure 3 shows cognitive profiles within the reading disability group from Figure 1. Note that the group profiles are parallel and do not meet the criteria for statistically significant differences between groups in elevation or shape (Fletcher et al., 1994). Although the difference between IQ and achievement is about one standard deviation, on other cognitive measures the differences average 0.3 standard deviations, consistent with the meta-analyses (Stuebing et al., 2002), with negligible differences on cognitive skills most closely associated with the academic domain. For example, there is little difference in phonological processing and rapid naming between IQ-discrepant and low-achieving children in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

IQ-Achievement Discrepancy Framework for Identification.

Note. From Fletcher and Miciak (2019, p. 12). Licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.

Figure 3.

Cognitive Profiles for Children in Figure 1 Who Meet IQ-Discrepancy Definitions of Reading Disability and Poor Readers Who Are Not Discrepant With IQ.

The null findings extend to prognosis (Shaywitz et al., 1999), intervention response (Morris et al., 2012; Stuebing et al., 2009; Vellutino et al., 2006), and brain function (Simos et al., 2014; Tanaka et al., 2011). Although a limited number of studies show small group differences in relation to IQ (e.g., (Hancock et al., 2016; Wadsworth et al., 2010), the majority of studies that include such group comparisons find no differences.

Null results also extend to other domains of SLD, the use of different IQ indices (e.g., Verbal IQ, Performance IQ), and even to communication disorders (Fletcher et al., 2019). These methods do not lack validity because individuals with an IQ achievement discrepancy are not SLD. The underlying classification lacks validity because groups formed based on the presence or absence of an IQ-achievement discrepancy do not differ in educationally meaningful ways.

Expressly disavowed by DSM-5, IDEA (2006) continued to allow IQ-achievement discrepancies because of concerns about the transition from commonly used methods but indicated that states could no longer require this method and provided alternatives (see Table 1). These results also call into question the routine use of IQ tests as a component of SLD identification because such tests are not strongly related to identification (or to SLD) and do not generate data useful for treatment planning. IQ tests should be used only if there is a question about ID (Fletcher et al., 2019).

Patterns of Strengths and Weaknesses (PSW).

An alternative, updated cognitive discrepancy approach eschews the use of Full Scale IQ scores but may use a composite or a subtest score from an IQ test or other measure to index a cognitive strength or weakness. These methods focus on intra-individual patterns of cognitive processing strengths and weaknesses as an inclusionary criterion for the identification of SLD. The operationalization of a PSW method is illustrated in Figure 4, with SLD indicated by an academic weakness in the presence of an unrelated cognitive processing strength and a cognitive processing weakness presumably contributory to the academic weakness. Composites and subtests from widely used norm-referenced cognitive and achievement test batteries are used and sometimes treated as interchangeable despite differences in content and normative samples.

Figure 4.

The Relation of Cognitive and Academic Strengths and Weaknesses in a Pattern of Strengths and Weaknesses (PSW) Identification Method.

Note. From Fletcher et al. (2019, p. 40). Licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.

Multiple methods have been proposed to operationally define these PSW methods, including (a) the concordance/discordance method (C/DM; Hale & Fiorello, 2004); (b) the dual discrepancy/consistency method (DDCM; Flanagan et al., 2018); (c) the discrepancy/consistency method (D/CM; Naglieri, 1999); and (d) the core selective evaluation process (C-SEP; Schultz & Stephens, 2015). These methods differ in multiple ways including their use of relative or normative comparisons to establish strengths and weaknesses, the size of the required discrepancy, what tests are required to be administered, and how exclusionary factors are considered. Although frequently presented as interchangeable (Hale et al., 2010), these methods do not identify groups with significant overlap (Miciak et al., 2016; Miciak, Fletcher, et al., 2014).

In both statistical simulations (Miciak et al., 2018; Stuebing et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2017) and actual data (Kranzler et al., 2016; Miciak et al., 2016; Miciak, Fletcher, et al., 2014) similar patterns emerge. The PSW methods that have been studied (C/DM, DDCM, and D/CM) identified a surprisingly low number of individuals as SLD. In simulations, these methods often identify less than 1% of the population with SLD at both the latent and the observed levels. This low rate of identification results in high specificity and negative predictive value estimates (e.g., good accuracy in identifying “Not SLD”). However, sensitivity and positive predictive values were low, suggesting these methods struggle to accurately identify individuals who truly have SLD. A large percentage of those who were SLD at the latent level were not identified as SLD by PSW methods at the observed level. Among those identified with SLD at the observed level, a low percentage were identified as SLD at the latent level. In addition, agreement across methods was poor, suggesting they are not interchangeable. In short, PSW methods subjected to empirical and statistical evaluation were highly accurate for identifying individuals who were not SLD (low false-negative error rates), but generated excessive false positives when indicating the presence of SLD.

There is little research on the validity of these widely implemented methods (Benson et al., 2018; McGill & Busse, 2017; Schneider & Kaufman, 2017), but most empirical studies yield null results. For example, Miciak, Fletcher, et al. (2014) compared academic profiles of struggling learners who met CDM or DDCM criteria for SLD and low achievers who did not meet SLD criteria. These comparisons did not yield differences in level or patterns of performance (Figure 5). Miciak et al. (2016) evaluated whether PSW status was associated with differential intervention response within a sample of struggling readers in upper elementary school. Comparisons of posttest performance for those who met PSW criteria for SLD with those who did not meet these criteria were largely null. In addition, PSW status at baseline did not improve the prediction of instructional response beyond baseline assessments of reading skills.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Achievement Profiles Not Used to Define Groups of Children With Specific Learning Disability and Slow Learners in Two Patterns of Strengths and Weaknesses (PSW) Methods.

Note. There are no significant differences in the shape or elevation of the achievement profiles. TOSREC, Test of Silent Reading Efficiency and Comprehension; WJ, Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement; Grade, Group Reading Assessment and Diagnostic Evaluation. C-DM, consistency-discrepancy method; XBA, cross battery assessment method. Data from Miciak, Fletcher, et al. (2014). From Fletcher et al. (2019, p. 53). Reprinted with permission.

A premise of many PSW proponents is that an assessment of cognitive processes permits the customization of interventions for a person identified with SLD. However, multiple literature reviews and meta-analyses have concluded that support for aptitude by treatment interactions and cognitively tailored interventions is largely null because such interventions are not strongly associated with improved academic skills (Burns et al., 2016; Kearns & Fuchs, 2013; Melby-Lervag et al., 2016). The overriding concerns about the relation of these methods to treatment are laid on a longer history of lack of support for different methods of cognitive profile analysis for IQ subtests (McGill et al., 2018). The utility of extensive assessments of cognitive skills for the identification of SLD—with or without profile analysis and discrepancy scores—has been widely questioned, especially given the time and expense of these assessments (Burns et al., 2016; Fletcher & Miciak, 2017) and the absence of evidence for value-added information facilitating identification or treatment (Hajovsky et al., 2022).

Instructional Response Methods.

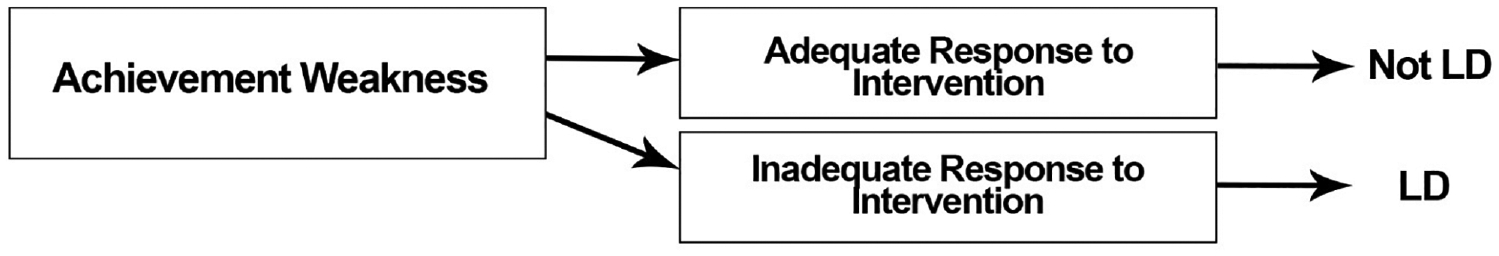

In a method based on instructional response, the key attribute of the classification is the documentation of inadequate or poor instructional response. A person with SLD has as a defining characteristic inadequate response to appropriate instruction (see Figure 6). Assessment of instructional response can be based on short assessments of reading or math fluency repeated multiple times during instruction or intervention (curriculum-based measurement; CBM), or based on standardized achievement measures administered following intensive intervention. There is a long history of research on these methods with good evidence for validity and enhanced instructional outcomes (Kovaleski et al., 2013; Stecker et al., 2005). How inadequate instructional response is operationalized varies in practice and in research on methods that incorporate CBM. Fuchs and Deshler (2007) identified at least three methods: (a) student growth over time (slope); (b) post-intervention performance (final status), or (c) both (dual discrepancy). However, none of these methods is free of the universal unreliability at the individual level because these methods force the imposition of thresholds on continuous, normally distributed measures that are imperfect because of measurement error (Fletcher et al., 2014). Multiple assessments of the same construct using tests with similar normative bases and confidence intervals may help with (but not fully ameliorate) this problem. Additional data documenting fidelity of implementation of the evidence-based intervention are also helpful for ruling out inadequate instructional opportunity (Kovaleski et al., 2013). These assessments of instructional response are best collected in the context of a service delivery framework known as multitier systems of support (MTSS), which includes universal screening, interventions of increasing intensity, and ongoing progress monitoring using CBM (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009; Fuchs et al., 2008). Although often reduced to its role in the SLD identification process because of the ease with which such data are collected, the goal of MTSS is to prevent and treat academic difficulties—data for SLD identification are a by-product.

Figure 6.

Instructional Response Framework for Identification.

Note. From Fletcher and Miciak (2019, p. 20). Licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.

In IDEA, instructional response data is explicitly required regardless of the SLD identification process to document an adequate opportunity to learn (US Department of Education, 2006, p. 46786). This helps to ensure that students will not be identified as SLD if they have not had adequate instructional opportunities. For identification methods based on instructional response, inadequate instructional response is considered inclusionary and represents a necessary, but not sufficient attribute of SLD. In contrast, cognitive discrepancy methods consider instructional response as exclusionary because of inadequate opportunity to learn (Fletcher et al., 2019). While cognitive discrepancy methods are based on traditional referral systems after the child begins to struggle, MTSS frameworks are designed to prevent academic difficulties in all children, including those at risk of SLD (Fuchs et al., 2008). The data on instructional response that might be used to determine SLD is a by-product of the MTSS process, and the child may need an evaluation to determine why they are not responding. These reasons can include SLD and may indicate a need for more intensive instruction and the civil rights protections afforded by SLD identification.

Many critics of instructional methods for SLD identification suggest that the methods attempt to identify SLD based solely on instructional response criteria (Reynolds & Shaywitz, 2009) or that these methods ignore the need for a comprehensive evaluation that includes the examination of comorbid and contextual factors (Hale et al., 2010). However, implementation of instructional response methods for identification typically documents multiple criteria: low achievement, inadequate instructional response, and consideration of exclusionary factors (Bradley et al., 2002; Kovaleski et al., 2013). A comprehensive evaluation is always recommended because eligibility decisions are high-stakes (Fletcher & Miciak, 2019).

Evidence for the validity of methods based on instructional response continues to accumulate. Groups defined as adequate and inadequate responders to instruction demonstrate different academic, behavioral, and cognitive characteristics (Al Otaiba & Fuchs, 2002; Cho et al., 2015; Miciak, Stuebing, et al., 2014). Neuroimaging research shows differences in the brain activation patterns of adequate and inadequate responders following intensive interventions in reading (Molfese et al., 2013; Nugiel et al., 2019; Rezaie et al., 2011). Figure 7 provides an illustration of the cognitive findings, showing significant differences in profile elevation, but not shape, among two groups of elementary school inadequate responders based on final status accuracy and fluency measures and groups of adequate responders and typical readers (Fletcher et al., 2011). These differences in elevation are consistent with a continuum of severity hypothesis (Vellutino et al., 2006) that posits a dimensional view of the attributes of SLD.

Figure 7.

Cognitive Profiles of Inadequate Responders With Decoding and Fluency Deficits and Only Fluency Deficits, Responders, and Typically Developing Children.

Note. Data from Fletcher et al. (2014). From Fletcher et al. (2019, p. 57). Reprinted with permission.

A Hybrid Method

A consensus group convened by the Office of Special Education Programs in the Department of Education recommended three essential criteria for SLD (Bradley et al., 2002). This consensus concluded that an assessment for SLD must document: (1) low achievement; (2) insufficient response to evidence-based interventions; and (3) absence of exclusionary factors: IDs, sensory deficits, serious emotional disturbances, lack of opportunity to learn, and lack of proficiency in English.

Figure 8 highlights the three components, which combine methods based on simple low achievement using norm-referenced tests and instructional methods based on curriculum-based measures, thus applying more than one indicator of low achievement and inadequate instructional response (Fletcher et al., 2019). In addition, comorbid conditions associated with SLD are evaluated as well as contextual factors that may indicate issues other than SLD, representing an assessment of the exclusionary factors that is broader and oriented toward intervention. There is no use of IQ tests except to rule out ID. Cognitive skills are not systematically evaluated outside academic domains because of the lack of evidence that such measures provide unique information not captured by achievement tests (Hajovsky et al., 2022).

Figure 8.

Rubric for Identifying SLDs in a Hybrid Model.

Note. The three components are evaluations for low achievement, inadequate instructional response, and other conditions and contextual factors associated with low achievement. From Fletcher et al. (2019, p. 62). Reprinted with permission.

In general, we interpret the evidence as favoring shorter, hypothesis-oriented approaches to SLD assessment where the assessment measures may vary, especially when comorbidity is considered. We propose that every person would receive a set of norm-referenced tests from the same battery and additional testing as indicated to complement the instructional response data. Even if the person has not been in an intervention where curriculum-based measures have been collected, there should be a review of instructional history including school reports, interventions attempted, and other academic services and accommodations. Screening assessments for ADHD and for behavior problems should be administered, along with additional assessments of language, especially if the individual does not have English as a primary language.

The approach we have proposed integrates assessment features involving simple low achievement with instructional response methods, providing multiple criteria and consideration of exclusionary factors outlined in DSM-5 and IDEA (Fletcher et al., 2019). For IDEA (2006), it meets the criteria for the required comprehensive evaluation, including (a) the use of a variety of assessment tools; (b) use of multiple criteria for identification; (C) use of technically sound instruments; (d) assessment of multiple areas of suspected disability and all areas of need regardless of eligibility domain; (e) provision of assessment data directly related to intervention; (f) assessment of relevant academic domains for SLD; (g) assessment for exclusionary criteria; and (h) assessment of the adequacy of instruction in reading and math.

Norm-Referenced Achievement Tests.

Norm-referenced achievement tests should be targeted to the six academic domains of SLD identified in IDEA as well as DSM-5. These assessments should include a brief assessment of foundational skills involved in basic reading, math calculations, and basic writing, such as spelling, as well as higher order skills such as reading comprehension, math reasoning, and writing composition. These latter assessments take more time because they assess more complex skills, but they are essential for children who are not impaired in basic academic skills but struggling in school. In addition, it is always important to assess automaticity since the inability to work quickly may require adaptative difficulties in classroom instruction. The goal is always to minimize time spent testing and to the extent possible, assess with tests that have the same normative basis. Current achievement levels, as well as individual strengths and weaknesses in reading, math, and written expression, can help instructors individualize an intervention plan and determine the necessary level of intensity.

Assessment of Instructional Response.

Assessing instructional response usually involves the use of curriculum-based assessments of reading, math, and spelling. These methods are given as serial probes and are usually time-constrained. In reading, a student may be asked to read word lists or stories as quickly as possible every 1 to 4 weeks during an instructional period; cloze or maze tasks are used that are more closely related to comprehension, but these tasks are moderately to highly correlated with word reading accuracy and fluency, and comprehension. In math, different grade-appropriate calculations are given in a time limited fashion. In written expression, timed spelling tests, alphabet writing tests, and other procedures are used. As noted earlier, normed-referenced assessments can also be used as final status measures. The critical component for identification is the student’s level at the end of an intervention period or some other point in the instructional period. For identification, the end point is more important than the slope or amount of change because the information on growth is contained in the end point. For modifying instruction, the slope is very important (Fletcher et al., 2019; Kovaleski et al., 2013). Figure 9 provides examples of progress monitoring charts for three actual students who responded to intervention (A), responded but needed more time in intervention (B), and did not respond to intervention (C).

Figure 9.

Individual Growth Curves for Three Adolescent Students Who Show Accelerated Gains (Student A), Average Growth (Student B), and Low Average (Inadequate) Growth (Student C).

Note. Panel A uses equated forms and estimated growth. Panel B shows actual raw score growth, illustrating the importance of form equation and estimated growth for understanding the fluctuations in raw scores. Data from Tolar et al. (2014). From Fletcher et al. (2019, p. 71). Reprinted with permission.

Exclusionary Criteria.

Academic difficulties may be due to other disabilities, such as a sensory problem, ID, or another pervasive disturbance of cognition, like autism spectrum disorder. These disorders have specific identification criteria and require interventions that address a much more pervasive impairment of adaptation that contrasts with the narrow impairment in adaptive skills that characterizes SLD. In addition, contextual factors that may interfere with achievement, such as limited English proficiency, comorbid behavioral problems, and economic disadvantage should also be considered. The goal of this part of the assessment is to determine whether such a condition is a primary cause of low achievement, a comorbid condition, or a result of low achievement. The consideration of these questions can also assist in planning for effective interventions. For example, children with ADHD who receive interventions to address both their attention and academic difficulties achieve better outcomes (Denton et al., 2020). Anxiety might also limit the effectiveness of standalone academic interventions. If a child is struggling to read and exhibits high levels of anxiety, a treatment program that addresses both reading and anxiety may be useful (Grills et al., 2013).

Limited English proficiency is another issue that must be considered, particularly in areas where many children come from homes in which English is not the primary language. Children who grow up in households where the language at home is different from the language of instruction are at greater risk for academic difficulties, primarily due to the difficulties associated with mastering academic content while learning a second language. Yet, there are no clear criteria or assessments that would differentiate a child with achievement difficulties due to SLD from a child who demonstrates limited English proficiency. One assessment strategy is to include assessments of oral language proficiency and achievement in both languages. However, these results must also be considered in context, as many English learners attend English-only classrooms and have not received academic instruction in their first language. Parsing the interconnected issues of academic difficulties and language proficiency takes careful consideration to ensure that students are not identified with SLD simply because they lack the English proficiency to perform well on achievement tests in English.

To address all potential exclusionary factors and better plan for treatment, the assessment should routinely include parent and teacher rating scales of behavior and academic adjustment, along with parent-completed developmental and medical history forms. These scales may identify behavioral comorbidities and historical factors (e.g., history of brain trauma) that are important to screen. If there is evidence for behavioral comorbidity, the guidelines for identifying these disorders in the DSM-5 should be followed. Simply referring a child for educational interventions without identifying and treating these factors will increase the probability of a poor intervention response.

Conclusions: SLD

As the field of SLD research and practice moves toward the future, we encourage the incorporation of assessments oriented to dimensional and probabilistic conceptions of SLD, such as Bayesian methods (Wagner et al., 2019). Current psychometric approaches are clearly not adequate and probabilistic approaches may help ameliorate the reliability problems inherent to making categorical determinations for a dimensional disorder. Practitioners should utilize psychometrically sound achievement data to help identify interventions of appropriate intensity tied to specific areas of SLD. These interventions should be explicit, customized, and address all of the individual child’s instructional needs, regardless of special education eligibility status or label. Finally, research identifying multivariate risk indicators that inform the early identification of individuals with higher probabilities to develop academic difficulties and SLD (Catts & Petscher, 2022; Wagner et al., 2019) should be prioritized, with an eye toward early intervention. A key change is to move assessment from a static process oriented around eligibility for services and diagnosis to a dynamic process oriented toward treatment and enhanced outcomes for people identified with SLD and others who struggle with academic skills.

Intellectual Disabilities

Diagnosis, Identification, and Clinical Features

In contrast to SLD, there is strong consensus from research and practice on the attributes, criteria, and assessment of ID (AAIDD, 2020). The primary attributes to be considered are intelligence, adaptive behavior, and age of onset. The criteria are test scores that are two standard deviations below average on multifactorial measures of IQ and achievement, with age of onset in the developmental period. Assessment involves measures of IQ and adaptive behavior, along with interviews, reviews of school and community records, and medical and developmental history.

The consensus definition is a three-pronged set of criteria developed by the AAIDD in a series of manuals now in its 12th edition (AAIDD, 2020). These manuals, which are routinely used in research and clinical practice, date back to 1959 and have consistently focused on these three attributes. As the AAIDD (2020) notes, “the three essential elements of ID- limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, and early age of onset- have not changed significantly over the past 60 years” (p. xii). The DSM-5 has similar diagnostic criteria (APA, 2013) as do the IDEA regulations (IDEA, 2006), which adds the need to document adverse effects on educational achievement. There are no substantive differences in the AAIDD and DSM-5 criteria. Rather, definitions are aligned across multiple sources. The AAIDD definition is included in Table 2, along with five assumptions essential to the application that will be discussed in the context of applying the criteria. ID replaces older terms, such as mental retardation and mental deficiency, which have negative and offensive connotations (Schalock et al., 2007). This change was formally adopted by Congress as Rosa’s Law in 2010 and codified in 2013 (Federal Register, 2013).

Table 2.

Definition of Intellectual Disability and Assumptions Regarding Its Application (AAIDD, 2020, p. 1).

| Intellectual disability is characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior as expressed in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive skills. The disability originates during the developmental period, which is defined operationally as before the individual attains age 22. The following five assumptions are essential to the application of this definition:

|

IDs are heterogeneous and have multiple causes. Although genetic causes are most widely understood, about 60% of cases have no known etiology. The causes can include environmental factors, including toxic exposure, brain trauma and infection, and psychosocial deprivation (Ellison et al., 2013). Many causes are genetic and syndromic, exemplified by single gene disorders like Fragile X syndrome (most common), Down syndrome, and Williams syndrome. However, up to one-fifth of cases are due to mutations known as copy number variants that have increased the number of known causes (Ellison et al., 2013). There are many factors related to the development of ID, which are typically discussed as risk factors (see below). In addition, the phenotypic expression of ID is highly variable, especially since ID occurs in association with other disorders, most notably autism spectrum disorder. What is important is that the identification of ID does not require the identification of a cause (AAIDD, 2020). Co-occurring disorders are considered examples of comorbidity, not causes of ID. Further, the presence of a genetic cause of ID does not automatically result in the identification of ID. All three criteria must be present, but the current editions of the AAIDD manual and DSM-5 emphasize the priority of adaptive behavior deficits, partly because of the historical over-emphasis on IQ scores (APA, 2013).

Known causes of ID are more likely to produce moderate and profound levels of ID, whereas mild ID is more likely to occur on the normalized continuum of IQ scores. To understand this phenomenon, it is helpful to examine Zigler’s (1969) idea of developmental versus difference manifestations of ID, which implicitly proposes a bimodal distribution of IQ scores. Zigler argued that some forms of ID were familial and occurred as normal variations on the IQ continuum. He contrasted these forms with “organic” forms of ID due to genetic and environmental events (e.g., trauma) that impaired brain function and would be part of a longer tail on the distribution of IQ scores. There is support for Zigler’s overall framework in many studies (e.g., Weisz & Yeates, 1981). Ironically, one of the reasons leading to the adoption of IQ-discrepancy methods for SLD identification was the Isle of Wight studies by Rutter and Yule (1975). In these studies, Rutter and Yule attempted to estimate the prevalence of “specific reading retardation.” They found that the bivariate distribution of IQ and reading scores had a non-normal distribution, with a long tail that represented “general backwards readers” whose reading levels were not discrepant with IQ. However, Rutter and Yule did not exclude children with known or suspected neurological disorders so backward readers were largely neurologically impaired children with IQ scores more than two standard deviations below average. This observation supports Zigler (1969), but SLD excludes ID and other epidemiological studies that exclude on the basis of low IQ do not find a bimodal distribution (Fletcher et al., 2019). The key issue for any individual suspected of ID is whether they meet the AAIDD/DSM-5 criteria.

Comorbidity

Comorbid conditions, such as personality disorder, psychosocial deprivation, emotional disorders, and conditions like autism spectrum disorder, are common in individuals with ID. It is not necessary to rule out comorbidities as a cause of impairments before a diagnosis of ID can be established. When comorbid diagnoses are present, both ID and co-occurring conditions are identified (APA, 2013, p. 39). Summarizing how the DSM-5 approaches ID, Tassé and Blume (2018) stated,

… regardless of the presence of any other coexisting behavioral or mental illness (such as antisocial personality disorder, to mention one), a diagnosis of intellectual disability should be made if the individual meets all three diagnostic prongs of intellectual disability, regardless of etiology or comorbid condition.

(p. 121)

It is well known that individuals with ID are vulnerable and three times more likely to have a co-occurring behavioral disorder, including substance abuse (Salekin et al., 2010). A comorbidity does not rule out ID.

Risk Factors

Different forms of ID do not have a known cause. There is no diagnostic requirement to specify the cause of the disability, although that is possible in some cases. ID has multiple risk factors, including genetic anomalies, family history, brain injury or microcephaly in the developmental period, drug use, emotional deprivation and abuse, prenatal exposure to alcohol and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, low levels of educational attainment, and other factors. These risk factors cannot usually be organized to demonstrate a cause of the ID, except in cases where a known genetic or brain-related etiology is present and even that in itself does not establish an ID diagnosis (AAIDD, 2020).

Assessment and Identification of ID

Intelligence.

In applying the three-prong definition in Table 2, the first prong is evidence of significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning, which is defined as a score on an individually administered multifactorial intelligence (IQ) test approximately two standard deviations below average. This test performance is usually represented as an IQ score of approximately 70 or below on a test standardized with an average of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. However, the determination of subaverage intellectual functioning is not a bright line. Even the most reliable intelligence tests have measurement error expressed as the standard error of measurement. If a two-standard error of measurement criterion is used, which is standard practice, the measurement error of the test is typically around 5 points on either side of the observed score (AAIDD, 2020). Application of a two standard error of measurement criterion is expressed as a 95% confidence interval. The confidence interval indicates that if a person were tested 100 times, their score would fall into the 95% confidence interval 95/100 times- not that there is a 95% probability that the obtained score is the true score (a common error). In the AAIDD and DSM-5 manuals, this is expressed as an IQ range of 65–75. This range reflects the reality that intelligence is not immutable and different scores may be obtained on the same test over time and across different tests at the same time.

An individually administered, comprehensive multifactorial test that assesses multiple components of intelligence is required (AAIDD, 2020; APA, 2013). The most widely accepted multifactorial IQ tests are different age-appropriate versions of the Wechsler intelligence scales (e.g., Weschler Intelligence Scales for Children-5; Wechsler, 2014), the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Test-5 (Roid, 2003), and the Woodcock-Johnson IV Tests of Cognitive Abilities—Fourth Edition (Schrank et al., 2014). Note that the Stanford-Binet and the adult version of the Wechsler scales are outdated, but newly normed versions are in development. Screening, short form, or group administered tests are not used to determine the level of intelligence for a diagnosis of ID (AAIDD, 2020, p. 29). According to AAIDD, the primary score should be one that incorporates at least three dimensions of intellectual ability and include six subtests, representing a composite score (e.g., Full-Scale IQ) and not a part score (e.g., Verbal or Performance IQ or verbal comprehension and perceptual organization indices, or the general ability index).

It is not uncommon for individuals with ID to have multiple IQ scores over time. Interpreting different IQ scores can be difficult because of differences across tests, such as different task demands and different normative samples. In addition, there is the problem of norms obsolescence, commonly referred to as the Flynn Effect (FE; Flynn, 1987). The FE is the trend for IQ scores to increase over time. The rate is conventionally estimated at 0.3 points per year, or 3 points per decade, which is supported by two major meta-analyses (Pietschnig & Voracek, 2015; Trahan et al., 2014). The FE is why test publishers try to update the normative basis of major IQ tests every 10 years. In the past, the normative standards used to create an age-adjusted, standardized IQ score could be as large as 50 years. As the AAIDD (2020) manual states,

Current best practice guidelines recommend that in cases in which an IQ test with aged norms is used as part of a diagnosis of ID, a correction of the full-scale IQ score of 0.3 points per year since the test norms were collected is warranted …

(p. 42)

Note that these guidelines recommend correcting the actual score so that different tests have comparable normative bases. It is really a correction of the normative basis for comparing scores. The correction is analogous to corrections of money for inflation so that one can compare the cost of goods in, for example, 2010 and 2020.

The scientific consensus about the need to correct for the FE is strong and virtually uniform, leading to a near-unanimous agreement that the FE should be used in determining ID and other eligibility decisions where a critical score is required (e.g., social security, special education placement, and capital punishment). Test manuals for versions of the Wechsler tests published since 2005 contain tables showing differences in scores for the current and previous editions of the child and adult tests and descriptions of the problem of norms obsolescence.

Adaptive Behavior.

For the second prong, there must be evidence of adaptive behavior deficits defined in three domains of daily living: conceptual, social, and practical (APA, 2013, p. 38; AAIDD, 2020, p. 29). Adaptive behavior is a person’s capacity for habitually performing activities of daily living in these three domains. The assessments do not measure capacity but what the person does habitually in a community setting. If a quantitative assessment is used, the score should be at least two standard deviations below the mean, considering the standard error of measurement, and expressed as a 95% confidence interval.

Conceptual deficits include language, reading and writing, math, number and time concepts, money management, and learning from experience. Social deficits represent interpersonal skills, relationships, self-esteem, gullibility and being easily led by others, and naiveté. Practical skills involve activities of daily living, including personal care, work, use of money, health care, and safety.

Individuals with ID typically demonstrate both strengths and weaknesses in adaptive behavior (see Table 2). The determination of whether a person has adaptive behavior difficulties is based on the assessed individual’s deficits, rather than strengths. It is inappropriate to weigh the assessed individual’s strengths against his or her weaknesses when assessing adaptive functioning (AAIDD, 2020): “all people with ID have strengths, but … the diagnosis of ID focuses on their significant limitations” (p. 40).

The identification of ID requires significant weaknesses in at least one of the three domains. A single adaptive behavior deficit is sufficient for identification, indicating that ongoing support is needed to perform adequately in one or more life settings at school, work, home, or in the community (APA, 2013, p. 38). Adaptive behavior is not assessed based on maladaptive behavior, which includes criminal behavior. Even individuals with ID have behavioral problems and engage in criminal behavior. Maladaptive behavior is not an indicator of the capacity for habitually performing activities of daily living (AAIDD, 2020). This capacity is based on standards for community-based living, not controlled, structured environments.

This concern especially applies to reports of strengths in adaptive behavior. Weaknesses in a structured setting raise a different concern. When an individual manifests deficits in a structured environment, these deficits demonstrate that even with the support provided by the institution, the structure is not sufficient for the person to perform independently.

The assessment of adaptive behavior involves the compilation of a variety of sources of information focused on reliable informants who had a position of responsibility or strong knowledge of the persons functioning during the developmental period (e.g., caregivers, family members, close friends, and teachers). Adaptive behavior is not assessed by only interviewing the person suspected of ID because of poor self-report skills and what is known as the “cloak of competence,” where people with mild levels of ID present themselves as more capable than they demonstrate on a daily basis. Self-reports can be corroborated by another source, but are not the primary source for assessing adaptive behavior.

When possible, formal assessments should be completed through the administration of rating scales and semi-structured interviews with reliable caregivers, such as the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-3 (Harrison & Oakland, 2015), the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow et al., 2016), and the Diagnostic Adaptive Behavior Scales (Tasse et al., 2017). The Vineland is well-known for its reliance on a semi-structured interview in which the caregiver is not asked direct questions about adaptive behavior, but is interviewed about key areas in development related to activities of daily living. The interview is designed to reduce responder bias that may be present with direct responses to questions. All three scales can be used as rating scales and also have versions for teachers. Adaptive behavior scales ask about behaviors that are completed habitually (i.e., typically) by the person, not whether the person is capable of a particular behavior. Formal scales are designed for caregivers and others who knew the person in the developmental period and are not completed by the person being assessed because of concerns about the reliability of self-reports.

Sometimes retrospective administrations of a standardized instrument are used with a caregiver or other person who knew the person in the developmental period or at a time when they were older, but trying to function in the community (Tassé, 2009). This practice is supported by the AAIDD (2020, pp. 41–42). It requires asking the interviewee to define a period of time when they were involved in caring or living with the person. The norms appropriate for that age period are used. In many instances it is not possible to conduct retrospective assessments using formal instruments because of sociocultural factors where the semi-structured interview does not make sense to the respondent, a lack of appropriate norms, or the absence of appropriate reporters (AAIDD, 2020, pp. 41–42).

Adaptive behavior assessment is very important for the diagnosis of ID. There is a risk of excessive reliance on IQ tests, which are not sufficient for the identification of ID. Many factors can produce subaverage scores on IQ tests, including other disorders, sociocultural factors, and language minority status. Although IQ tests are reliable and valid for English speakers raised in the United States, there are drawbacks when assessing people born in another country and for whom English is not their native language. There are adaptations of other tests for other countries and languages, but often the normative basis is not as strong as the U.S. versions of multifactorial tests. As the DSM-5 indicates, when there are questions about IQ scores, the adaptive behavior assessments should be given more weight. DSM-5 specifically establishes the severity of ID using adaptive behavior assessment and not IQ levels.

Age of Onset.

The third prong is evidence of the onset of deficits in general intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior in the developmental period, defined by the AAIDD (2020) as up to 22 years. There is no specification of a specific upper limit in the DSM-5 criteria, but it is still understood as manifested in the developmental period. This assessment is usually based on a review of history and interviews with caregivers (Reschly, 2009).

Conclusions: ID

We have relied on the AAIDD and DSM-5 manuals to emphasize the consensus that has emerged over the past 50 years on the identification of ID. In contrast to SLD, the definition and three pronged criteria are widely accepted. It is important for assessment professionals to be familiar with these guidelines because assessments of ID frequently contribute to high-stakes decisions, such as social security eligibility and capital punishment cases. In these cases, it is critical that the assessment consider adaptive behavior in addition to IQ scores, which contain measurement error and may reflect outdated norms. Full consideration of adaptive behavior also assists with treatment planning: people with ID benefit from a range of school and community support services and as Table 2 suggests, improve in adaptation and independence. Appropriate identification can lead to much improved outcomes for people with ID.

Discussion

This review of evidence-based practices for the assessment of SLD and ID yields interesting comparisons. Both SLD and ID depend on psychometric assessment using tests of performance. They are the only two childhood disorders in DSM-5 that require performance-based assessment using tests. However, the criteria for identification and assessment approaches to identify the disorders are very different. There is little consensus on the assessment and identification of SLD. Assessment methods vary and many are in wide use despite lack of evidence for their validity and established problems with reliability. Fundamental measurement issues such as the role of measurement error, the use of fixed thresholds on normal distributions, the increased unreliability of discrepancy scores, and regression to the mean due to correlated tests are often ignored in research and practice. In contrast, the assessment of ID reflects consensus around the definition and criteria. Measurement issues are identified and addressed in practice guidelines. Firm thresholds are not used and confidence intervals express a range of scores considering the standard error of measurement of the tests. There is a clear rationale for multi-pronged criteria and their integration, which is often missing for SLD assessments despite frequent calls to consider multiple criteria and their embodiment in IDEA requirements. For both SLD and ID, the ultimate decision requires clinical judgment based on reliable data. By definition, SLD and ID are exclusionary of one another; the key difference between the two is in adaptive behavior. SLD is a narrow impairment in adaptation, while ID is characterized by more pervasive impairments that interfere with community independence. As such, the two disorders require very different approaches to treatment, with a focus on academic skills in SLD and a focus on independent living in ID. Nonetheless, it would be useful to see more continuity in how issues related to reliability and measurement are treated so that assessment procedures and diagnosis can be more streamlined.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in part by grant P50 HD052117, Texas Center for Learning Disabilities from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Al Otaiba S, & Fuchs D (2002). Characteristics of children who are unresponsive to early literacy intervention: A review of the literature. Remedial and Special Education, 23(5), 300–316. [Google Scholar]

- American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. (2020). Intellectual disabilities: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Support (12th ed.). [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – 5. [Google Scholar]

- Barth AE, Stuebing KK, Anthony JL, Denton CA, Mathes PG, Fletcher JM, & Francis DJ (2008). Agreement among response to intervention criteria for identifying responder status. Learning and Individual Differences, 18, 296–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson NF, Beaujean A, McGill RJ, & Dombroski SC (2018). Critique of the core-selective evaluation process. Journal of the Texas Educational Diagnosticians’ Association, 47, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bentum KE, & Aaron PG (2003). Does reading instruction in learning disability resource rooms really work? A longitudinal study. Reading Psychology, 24(3–4), 361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Danielson L, & Hallahan DP (2002). Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Burns MK, Peterson-Brown S, Haegele K, Rodriguez M, Schmitt B, Cooper K, Clayton SH, Conner C, Hosp A, & VanDerHeyden AM (2016). Meta-analysis of academic interventions derived from neuropsychological data. School Psychology Quarterly, 31, 28–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt C (1937). The backward child. University of London Press. [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW, Compton D, Tomblin B, & Bridges MS (2012). Prevalence and nature of late Emerging poor readers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 10, 166–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]