Abstract

Background

Placental anomalies, including placenta previa (PP), placenta accreta spectrum disorders (PAS), and vase previa (VP), are associated with several adverse foetal-neonatal and maternal complications. However, there is still a lack of robust evidence on the pathogenesis and adverse outcomes of the diseases. Through this umbrella review, we aimed to systematically review existing meta-analyses exploring the factors and outcomes for pregnancy women with placental anomalies.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library from inception to February 2023. We used AMSTAR 2 to assess the quality of the reviews and estimated the pooled risk and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each meta-analysis.

Results

We included 34 meta-analyses and extracted 55 factors (27 for PP, 22 for PAS, and 6 for VP) and 16 outcomes (12 for PP, and 4 for VP) to assess their credibility. Seven factors (maternal cocaine use (for PP), uterine leiomyoma (for PP), prior abortion (spontaneous) (PP), threatened miscarriage (PP), maternal obesity (PP), maternal smoking (PAS), male foetus (PAS)) had high epidemiological evidence. Twelve factors and six outcomes had moderate epidemiological evidence. Twenty-two factors and eight outcomes showed significant association, but with weak credibility.

Conclusions

We found varying levels of evidence for placental anomalies of different factors and outcomes in this umbrella review.

Registration

PROSPERO: CRD42022300160.

Placental anomalies are associated with several adverse foetal-neonatal and maternal complications. They have three principal types: placenta previa (PP), placenta accreta spectrum disorders (PAS), and vase previa (VP) [1]. According to existing systematic reviews, the prevalence of placental anomalies has been increasing over the past two decades due to the growing incidence of assisted reproductive technologies and caesarean section [2–5]. The cause of placental anomalies is multifactorial, as are the related adverse pregnancy outcomes [6]. In particular, several factors and adverse outcomes, such as smoking, endometriosis, caesarean delivery, and perinatal haemorrhage, preterm delivery, foetal death, have been proposed as being relate to placental anomalies [7–9]. However, robust evidence to the pathogenesis and adverse outcomes of the diseases remain largely unknown.

Numerous meta-analysis and systematic reviews have explored the factors and pregnancy outcomes linked to placental anomalies [9–11]. However, most are incomplete and controversial, as they are limited by excess significance and publication bias. To consolidate the data from these meta-analyses, two umbrella reviews reported the risk factors for PP [7] and PAS [8], respectively. Although they identified some risk factors, they were still incomplete due to limited environmental risk factors. They also did not evaluate other common factors for PP (alcohol, obesity, threatened miscarriage, etc.) and non-environmental factors for PAS (prior abortion, prior uterine artery embolization, smoking, etc.), nor did they summarise the adverse pregnancy outcomes for either placental anomaly type.

Therefore, to evaluate the strength of epidemiological evidence of the reported associations of various factors and pregnancy outcomes with placental anomalies, including PP, PAS, and VP, we conducted an umbrella review of the evidence across existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We formed the following PICO question (except for the intervention, which our study did not have): ‘How does the strength of epidemiological evidence for factors and outcomes (O) for placental anomalies (P) compared to normal pregnant women (C)’?

METHODS

We conducted an umbrella review using standardised methodology and reported our findings according to the PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines [12,13]. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022300160).

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library from inception to 8 February 2023 to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that analysed the association between factors and outcomes and placental anomalies, including PP, PAS, and VP. We conceptualised the search strategy around the following keywords: ‘morbidly adherent placenta,’ ‘abnormal placentation,’ ‘placenta previa,’ ‘placenta accreta spectrum disorders,’ or ‘vasa previa,’ combined with ‘systematic review’ or ‘meta-analysis’ (File S1 in the Online Supplementary Document). We did not impose any language limitations when choosing the appropriate studies. We also manually searched the reference lists of relevant reviews and performed forward and backward citation chaining. Two researchers (DF and LL) independently screened and evaluated the full texts of potentially eligible articles. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all meta-analyses of observational studies that investigated the causes and consequences of PP, PAS, and VP, irrespective of their publication date. We excluded systematic reviews without meta-analyses, animal studies, genetic studies, conference abstracts, letters, and editorials (File S2 in the Online Supplementary Document). If we found two similar articles, we included the most recent in the analysis, as it likely comprises more studies and/or is of the highest quality per the AMSTAR 2 tool [14].

Data extraction

Two researchers (DF and JR) extracted the following data independently: first author, journal and year of publication, factor(s) and outcome(s) of interest (PP, PAS, or VP), and number of studies analysed. Where possible, they extracted other data such as estimated value, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), P-values, the number of participants in each groups, analytical data model, heterogeneity, and small-study effects. Disagreements in the extraction process were resolved through consensus.

Quality of meta-analyses

Two investigators (DF and YM) assessed the methodological quality of each included meta-analysis using the AMSTAR 2 tool, a reliable and valid instrument facilitates the quality assessment of meta-analysis and systematic reviews [14–16] (File S3 in the Online Supplementary Document). AMSTAR 2 categorises the quality of a meta-analysis on a scale from critically low to high, based on 16 predefined items [17]. Each item has three responses – yes, partial yes, and no; items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 are key to the evaluation. Overall, the included articles are ranked as high, moderate, low, or critically low.

Determining the credibility of evidence

We noted which associations met the following criteria to determine the strength of the epidemiologic evidence (i.e. the confidence in the effect estimate): Precision of the estimate (i.e. P-value <0.001, a threshold associated with significantly less false-positive results, and over 1000 cases with the disease); consistency of results (I2<50% and Cochran’s Q test P-value >0.10); and no evidence of small-study effects (P-value >0.10) [18–20].

We ranked the strength of epidemiologic evidence as high (when all the above criteria were satisfied), moderate (if a maximum of one criterion was not satisfied and a P-value <0.001), or weak (P-value <0.05). If the P-value was not reported, we calculated the 95% CI of the pooled effect estimate using a standard method.

Statistical analysis

We displayed the derived random-effects estimates using forest plots to show the relationships between various factors or outcomes and PP, PAS, or VP. We computed and presented the random-effects estimate whenever a fixed-effects model was originally used. In practice, these different measures (rate ratio (RR), odds ratio (OR), and hazard ratio (HR)) of effect yield similar estimates, since PP, PAS, or VP is a rare occurrence. We converted these various measurements to ORs using a standardised methodology [21]. We used the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality of continuous variables and presented data with skewed distribution using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). We considered P-value <0.05 statistically significant, except for heterogeneity and small-study effects. All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata software, version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Search results

We retrieved 689 studies, of which 34 met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). They were published between 2003 and 2023. Twenty-seven articles focussed on PP [9,10,15–17,22–43], eight on PAS [10,11,25,44–48], and only two on VP [9,49]. Two articles [10,25] focussed on PP and PAS and one [9] on PP and VP. We found 55 factors (27 for PP, 22 for PAS, and 6 for VP) and 16 outcomes (12 for PP, and 4 for VP) in the 34 included studies. No meta-analysis evaluated the outcomes for PAS. There was a median of six primary studies per evidence synthesis (IQR = 3–12) with a median number of 1772 cases (IQR = 359–9532) and 278 459 subjects (IQR = 48 209–1 055 206) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature search.

Table 1.

Characteristics, quantitative synthesis, and assessment of the included meta-analyses

| Random effects model |

Heterogeneity |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Factors/outcomes

|

Author (year)

|

Number of studies

|

Number of cases

|

Number of subjects

|

OR (95% CI)

|

P-value |

I

2

|

P-value

|

Small study effects

|

AMSTAR 2

|

Credibility of the evidence

|

|

Factors for PP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AMA (>45 y) |

Sugai et al. (2023) [41] |

14 |

101 794 |

14 604 565 |

3.61 (2.70–4.81) |

0.0001 |

81.4% |

0.0001 |

0.459 |

High |

Moderate |

| ART (programmed frozen ET) |

Busnelli et al. (2022) [23] |

10 |

642 |

75 973 |

1.12 (0.88–1.43) |

0.342 |

37.3 |

0.0485 |

0.869 |

Low |

NS |

| IMH |

Zhuo et al. (2022) [42] |

4 |

941 |

36 683 |

1.79 (0.64–5.01) |

0.218 |

63.2 |

0.043 |

0.270 |

Low |

NS |

| Maternal alcohol |

Steane et al. (2021) [10] |

4 |

16 071 |

6 984 743 |

1.27 (1.00–1.60) |

0.047 |

62.5 |

0.046 |

0.482 |

High |

Weak |

| Endometriosis |

Matsuzaki et al. (2021) [24] |

19 |

53 084 |

7 282 776 |

3.53 (3.00–4.16) |

0.0001 |

72.6 |

0.0001 |

0.036 |

High |

Weak |

| Adolescent pregnancy |

Karacam Z, 2021 [26] |

7 |

126 |

25 696 |

0.52 (0.31–0.88) |

0.010 |

0 |

0.580 |

0.562 |

High |

Weak |

| Prior UAE |

Matsuzaki et al. (2021) [25] |

4 |

2220 |

320 906 |

5.66 (1.78–18.02) |

0.003 |

55 |

0.083 |

0.062 |

Low |

Weak |

| Anti-TNF in IBD |

Tandon et al. (2020) [27] |

2 |

5 |

1188 |

1.58 (0.30–8.48) |

0.591 |

0 |

0.554 |

- |

Low |

NS |

| Uterine leiomyoma |

Jenabi et al. (2019) [28] |

9 |

1772 |

255 886 |

2.29 (1.64–3.20) |

0.0001 |

33.2 |

0.152 |

0.281 |

Low |

High |

| ART (endometriosis) |

Horton et al. (2019) [15] |

6 |

164 |

4646 |

3.31 (1.26–8.71) |

0.020 |

80 |

0.0001 |

0.335 |

High |

Weak |

| AMA (>35 y) |

Martinelli et al. (2018) [31] |

23 |

113 990 |

21 961 192 |

3.16 (2.79–3.57) |

0.0001 |

96.5 |

0.0001 |

0.318 |

High |

Moderate |

| ART (singleton pregnancy) |

Karami et al. (2018) [32] |

14 |

3846 |

965 379 |

2.80 (1.99–3.61) |

0.0001 |

72.7 |

0.0001 |

0.986 |

Low |

Moderate |

| ART (twin pregnancy) |

Karami et al. (2018) [32] |

9 |

87 |

17 063 |

2.56 (0.97–4.14) |

0.002 |

0 |

0.990 |

0.706 |

Low |

Weak |

| ART (fresh ET) |

Sha et al. (2018) [30] |

6 |

816 |

72 584 |

1.63(1.13–2.36) |

0.009 |

65 |

0.014 |

0.026 |

Low |

Weak |

| Maternal smoking |

Shobeiri et al. (2017) [33] |

21 |

16 878 |

9 094 443 |

1.35 (1.27–1.44) |

0.0001 |

62.8 |

0.0001 |

0.026 |

Low |

Weak |

| Prior abortion (spontaneous) |

Karami et al. (2017) [16] |

16 |

3036 |

58 713 |

1.77 (1.60–1.94) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.652 |

0.742 |

Low |

High |

| Prior abortion (induced) |

Karami et al. (2017) [16] |

10 |

2946 |

62 459 |

1.36 (1.02–1.69) |

0.0001 |

59.2 |

0.009 |

0.486 |

Low |

Moderate |

| HDP |

Yin et al. (2015) [17] |

7 |

2583 |

505 738 |

0.53 (0.30–0.94) |

0.029 |

85.5 |

0.0001 |

0.590 |

Critically low |

Weak |

| Maternal asthma |

Wang et al. (2014) [34] |

8 |

3793 |

1 359 749 |

1.19 (1.04–1.37) |

0.010 |

0 |

0.599 |

0.412 |

Low |

Weak |

| CHB infection |

Huang et al. (2014) [35] |

7 |

9119 |

1 687 276 |

1.77 (0.69–4.59) |

0.237 |

53.5 |

0.044 |

0.087 |

Low |

NS |

| eSET |

Grady et al. (2012) [36] |

1 |

72 |

15 306 |

6.02 (2.74–13.25) |

0.0001 |

- |

- |

- |

Low |

Weak |

| Prior CS |

Gurol-Urganci et al. (2011) [37] |

37 |

9532 |

399 674 |

1.79 (1.60–1.98) |

0.0001 |

82 |

0.0001 |

0.027 |

Low |

Weak |

| Miscarriage (threatened) |

Saraswat et al. (2010) [38] |

6 |

229 |

64 365 |

1.62 (1.19–2.21) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.477 |

0.706 |

Low |

High |

| Maternal obesity |

Heslehurst et al. (2008) [39] |

7 |

2647 |

756 217 |

0.83 (0.71–0.96) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.526 |

0.305 |

Low |

High |

| Maternal cocaine use |

Faiz et al. (2003) [40] |

3 |

359 |

55 562 |

2.91 (1.90–4.29) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.526 |

0.448 |

Critically low |

High |

| Male foetus |

Faiz et al. (2003) [40] |

7 |

3620 |

798 119 |

1.20 (1.12–1.31) |

0.0001 |

41.9 |

0.215 |

0.0001 |

Critically low |

Weak |

| Preeclampsia |

Faiz et al. (2003) [40] |

3 |

445 |

37 922 |

0.89 (0.51–1.41) |

0.546 |

50.2 |

0.046 |

0.334 |

Critically low |

NS |

|

Outcomes for PP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Blood transfusion (CS) |

Iqbal et al. (2022) [22] |

17 |

10 903 |

384 949 |

7.62 (5.79–10.03) |

0.0001 |

88.8 |

0.0001 |

0.141 |

Low |

Moderate |

| Preterm delivery (<37 weeks) |

Jansen et al. (2022) [43] |

12 |

2 247 569 |

23 664 492 |

9.51 (7.60–11.91) |

0.0001 |

97.1 |

0.0001 |

0.028 |

High |

Weak |

| Preterm delivery (<34 weeks) |

Jansen et al. (2022) [43] |

5 |

611 191 |

22 444 795 |

6.12 (4.29–8.72) |

0.0001 |

90.5 |

0.0001 |

0.999 |

High |

Moderate |

| Preterm delivery (<32 weeks) |

Jansen et al. (2022) [43] |

4 |

337 186 |

22 861 089 |

8.58 (6.35–11.58) |

0.0001 |

88.7 |

0.0001 |

0.377 |

High |

Moderate |

| Preterm delivery (<28 weeks) |

Jansen et al. (2022) [43] |

4 |

98 186 |

22 792 315 |

5.61 (4.02–7.83) |

0.0001 |

61.6 |

0.050 |

0.193 |

High |

Moderate |

| IUGR |

Balayla et al. (2019) [29] |

13 |

10 575 |

1 593 226 |

1.31 (0.98–1.75) |

0.071 |

92 |

0.0001 |

0.498 |

Low |

NS |

| NICU admission |

Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] |

5 |

48 915 |

844 906 |

4.09 (2.75–6.09) |

0.0001 |

96.6 |

0.0001 |

0.777 |

Low |

Moderate |

| Neonatal death |

Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] |

3 |

57 765 |

22 929 501 |

5.43 (3.03–9.74) |

0.0001 |

88.7 |

0.0001 |

0.594 |

Low |

Moderate |

| Perinatal death |

Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] |

3 |

5422 |

597 163 |

3.00 (1.38–6.54) |

0.006 |

88.6 |

0.0001 |

0.553 |

Low |

Weak |

| SGA |

Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] |

5 |

146 039 |

1 137 103 |

0.97 (0.67–1.41) |

0.875 |

90.5 |

0.0001 |

0.526 |

Low |

NS |

| APGAR-1 < 7 |

Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] |

2 |

20 155 |

278 459 |

3.15 (1.69–5.88) |

0.0001 |

93.9 |

0.0001 |

- |

Low |

Weak |

| APGAR-5 < 7 |

Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] |

3 |

1839 |

635 703 |

2.73 (2.25–3.29) |

0.039 |

98.7 |

0.0001 |

0.652 |

Low |

Weak |

|

Factors for PAS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Maternal smoking |

Jenabi et al. (2022) [45] |

14 |

9800 |

3 892 832 |

1.21 (1.02–1.41) |

0.0001 |

4.7 |

0.400 |

0.439 |

Low |

High |

| HDP |

Li et al. (2022) [44] |

6 |

816 |

126 224 |

0.74 (0.38–1.44) |

0.379 |

54.1 |

0.054 |

0.317 |

Low |

NS |

| Prior UAE |

Matsuzaki et al. (2021) [25] |

3 |

55 |

3236 |

25.83 (10.87–61.37) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.677 |

0.062 |

Low |

Moderate |

| ART |

Matsuzaki et al. (2021) [46] |

9 |

1081 |

206 634 |

5.03 (3.34–7.56) |

0.0001 |

76.4 |

0.0001 |

0.008 |

Low |

Weak |

| Maternal alcohol |

Steane et al. (2021) [10] |

1 |

350 |

79 393 |

0.92 (0.46–1.86) |

0.814 |

- |

- |

- |

High |

NS |

| Male foetus |

Hou et al. (2020) [47] |

5 |

1856 |

804 043 |

0.79 (0.74–0.84) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.0001 |

0.953 |

High |

High |

| Multiple gestations |

Hou et al. (2020) [47] |

7 |

147 |

30 458 |

1.79 (0.91–2.66) |

0.0001 |

80.5 |

0.0001 |

0.310 |

High |

Moderate |

| Low SES |

Hou et al. (2020) [47] |

3 |

390 |

244 792 |

0.47 (0.26–0.67) |

0.0001 |

87.3 |

0.0001 |

0.162 |

High |

Moderate |

| Maternal obesity |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

5 |

516 |

554 106 |

1.33 (1.02–1.74) |

0.038 |

0 |

0.543 |

0.893 |

High |

Weak |

| AMA |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

17 |

1152 |

1 055 206 |

2.40 (1.12–5.16) |

0.024 |

96.1 |

0.0001 |

0.038 |

High |

Weak |

| Prior uterine surgery |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

34 |

1869 |

1 057 363 |

3.04 (2.16–4.29) |

0.0001 |

77 |

0.0001 |

0.626 |

High |

Moderate |

| Prior CS |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

33 |

1662 |

656 168 |

3.12 (2.14–4.55) |

0.0001 |

78.3 |

0.0001 |

0.956 |

High |

Moderate |

| PP |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

24 |

1694 |

1 057 222 |

4.75 (2.06–10.93) |

0.0001 |

96.8 |

0.0001 |

0.145 |

High |

Moderate |

| Multiparity |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

19 |

1559 |

1 022 765 |

1.95 (1.43–2.65) |

0.0001 |

70.9 |

0.0001 |

0.718 |

High |

Moderate |

| PP and prior CS |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

12 |

331 |

429 007 |

6.91 (1.29–37.08) |

0.024 |

96.1 |

0.0001 |

0.037 |

High |

Weak |

| Prior curettage |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

16 |

644 |

10 886 |

1.54 (0.91–2.62) |

0.109 |

78.9 |

0.0001 |

0.910 |

High |

NS |

| Prior myomectomy |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

9 |

309 |

938 |

0.76 (0.35–1.66) |

0.486 |

0 |

0.617 |

0.557 |

High |

NS |

| Prior abortion |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

6 |

543 |

36 111 |

1.22 (0.87–1.71) |

0.243 |

40.5 |

0.135 |

0.583 |

High |

NS |

| Prior CS (elective) |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

3 |

506 |

693 724 |

2.47 (0.17–36.67) |

0.512 |

99.2 |

0.0001 |

0.290 |

High |

NS |

| Prior CS (emergency) |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

3 |

316 |

606 098 |

1.41 (0.33–6.03) |

0.642 |

96.2 |

0.0001 |

0.101 |

High |

NS |

| SISP |

Iacovelli et al. (2020) [11] |

2 |

143 |

820 |

1.60 (0.63–4.10) |

0.324 |

78.3 |

0.032 |

- |

High |

NS |

| ART (frozen ET) |

Roque et al. (2018) [48] |

2 |

149 |

48 209 |

3.51 (2.04–6.05) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.553 |

- |

Low |

Moderate |

|

Factors for VP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| STPP |

Ruiter et al. (2016) [49] |

4 |

1231 |

202 296 |

18.97 (6.13–58.68) |

0.0001 |

66 |

0.030 |

0.282 |

High |

Weak |

| VCI |

Ruiter et al. (2016) [49] |

2 |

161 |

20 634 |

93.57 (25.29–346.21) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.580 |

- |

High |

Weak |

| ART |

Ruiter et al. (2016) [49] |

2 |

1997 |

84 881 |

18.95 (6.61–54.34) |

0.0001 |

29 |

0.240 |

- |

High |

Weak |

| Bilobed placenta |

Ruiter et al. (2016) [49] |

2 |

72 |

19 776 |

55.84 (11.89–262.26) |

0.0001 |

0 |

0.999 |

- |

High |

Weak |

| CILTTU |

Ruiter et al. (2016) [49] |

2 |

61 |

5010 |

279.28 (1.51–51547.34) |

0.030 |

86 |

0.007 |

- |

High |

Weak |

| Multiple gestations |

Ruiter et al. (2016) [49] |

3 |

627 |

16 660 |

3.14 (0.97–10.11) |

0.055 |

0 |

0.454 |

- |

High |

NS |

|

Outcomes for VP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Preterm delivery |

Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] |

1 |

21 743 |

246525 |

3.36 (2.76–4.09) |

0.0001 |

- |

- |

- |

Low |

Weak |

| SGA |

Vahanian et al. (2016) [9] |

1 |

5192 |

246 525 |

4.02 (2.64–6.12) |

0.0001 |

- |

- |

- |

Low |

Weak |

| Perinatal death |

Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] |

1 |

3463 |

246 525 |

4.52 (2.77–7.39) |

0.0001 |

- |

- |

- |

Low |

Weak |

| APGAR-5 < 7 | Vahanian et al. (2015) [9] | 1 | 7651 | 246 525 | 2.18 (1.36–3.50) | 0.003 | - | - | - | Low | Weak |

AMA – advanced maternal age, APGAR – appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration, ART – assisted reproductive techniques, CHB – chronic hepatitis B, CS – caesarean section, eSET – elective single embryo transfer, ET – embryo transfer, HDP – hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, NS – not significant, OR – odds ratio, PAS – placenta accreta spectrum disorders, PP – placenta previa, SES – socioeconomic status, SGA – small for gestational age, SISP – short interval between prior caesarean section and subsequent pregnancy (<23 mo), STPP – second trimester placenta previa, TNF – tumour necrosis factor, UAE – uterine artery embolization, VCI – velamentous cord insertion, VP – vasa previa, wk – weeks.

Quality assessment of meta-analyses

Eleven studies were of ‘high’ (32.35%), twenty-one of ‘low’ (61.77%), and two of ‘critically low’ quality (6.45%). The most frequent flaw was the absence of a registered protocol (item 2: 23 meta-analyses (67.65%)) and inadequacy of the literature search (item 4: 2 meta-analyses (5.88%)) (File S3 in the Online Supplementary Document).

Strength of epidemiologic evidence

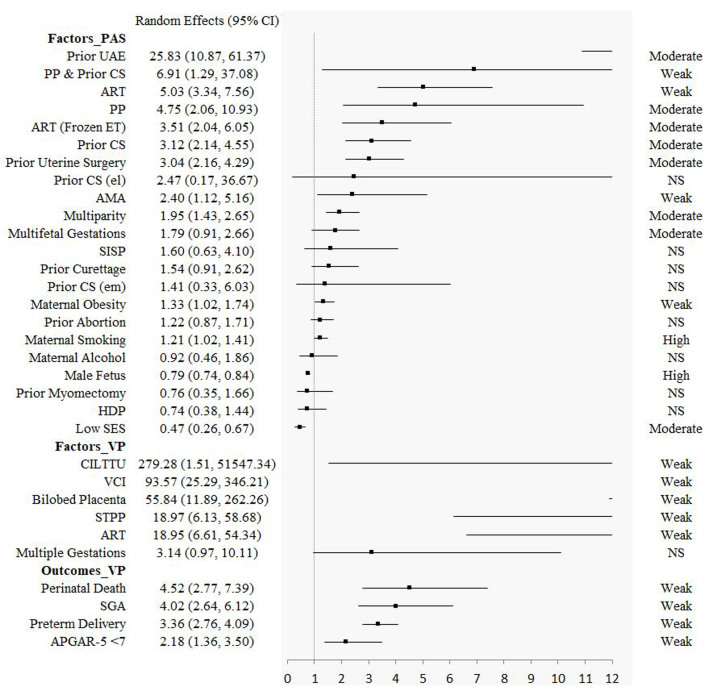

Seven factors (maternal cocaine use (for PP), uterine leiomyoma (for PP), prior abortion (spontaneous) (PP), threatened miscarriage (PP), maternal obesity (PP), maternal smoking (PAS), male foetus (PAS)) had high epidemiological evidence. Twelve factors (advanced maternal age (>45 years) (PP), advanced maternal age (>35 years) (PP), assisted reproductive techniques (singleton pregnancy) (PP), prior abortion (induced) (PP), prior uterine artery embolization (PAS), placenta previa (PAS), assisted reproductive techniques (frozen embryo transfer) (PAS), prior caesarean section (PAS), prior uterine surgery (PAS), multiparity (PAS), multiple gestations (PAS), low socioeconomic status (PAS)) and six outcomes (preterm delivery (<32 weeks) (PP), blood transfusion in caesarean section (PP), preterm delivery (<34 weeks) (PP), preterm delivery (<28 weeks) (PP), neonatal death (PP), neonatal intensive care unit (PP)) had moderate epidemiological evidence. Twenty-two factors (13 for PP, 4 for PAS, and 5 for VP) and eight outcomes (4 for PP, and 4 for VP) showed significant association, but with weak credibility. Other fourteen factors (5 for PP, 8 for PAS, and 1 for VP) and two outcomes (for PP) showed no statistically significant estimates (Table 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3; File S4 in the Online Supplementary Document).

Figure 2.

The results of factors and outcomes for placenta previa. AMA – advanced maternal age, ART – assisted reproductive techniques, CHB – chronic hepatitis B, CI – confidence interval, CS – caesarean section, eSET – elective single embryo transfer, ET – embryo transfer, HDP – hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, IBD – inflammatory bowel disease, IMH – isolated maternal hypothyroxinaemia, IUGR – intrauterine growth restriction, NICU – neonatal intensive care unit, NS – not significant, PP – placenta previa, SGA – small for gestational age, TNF – tumour necrosis factor, UAE – uterine artery embolization.

Figure 3.

The results of factors for placenta accrete spectrum disorders and the factors and outcomes for vasa previa. AMA – advanced maternal age, ART – assisted reproductive techniques, CI – confidence interval, CILTTU – cord insertion in the lower third of the uterus at first trimester ultrasound, CS – caesarean section, ET – embryo transfer, HDP – hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, NS – not significant, PAS – placenta accreta spectrum disorders, PP – placenta previa, SES – socioeconomic status, SGA – small for gestational age, SISP – short interval between prior caesarean section and subsequent pregnancy (<23 months), STPP – second trimester placenta previa, UAE – uterine artery embolization, VCI – velamentous cord insertion, VP – vasa previa.

DISCUSSION

In this umbrella review, we identified seven factors demonstrating high strength of epidemiologic evidence, as well as twelve factors and six outcomes demonstrating moderate strength of epidemiologic evidence. Meanwhile, the estimate of effect’s degree of confidence was weaker another 22 factors and 8 outcomes. The methodological quality across meta-analyses differed slightly.

A previous umbrella study has attempted to explore the risk factors for PP [7] and found seven high and two weak risk factors. We evaluated a further sixteen factors and found two which had two high epidemiological evidence (threatened miscarriage and maternal obesity). We also twelve outcomes – six moderate, four weak, and two of insignificant epidemiologic evidence. Compared to previous study [7], we not only explored risk factors, but also reported outcomes for PP, addressing the existing gap in the literature.

A previously published umbrella review evaluated and found seven environmental risk factors for PAS [8]; in our study, we found another 15 – one of high, five of moderate, three of weak, and six of statistically insignificant epidemiological evidence.

The factors found in the previous umbrella review and our study differ slightly. This includes four factors for PP (hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; assisted reproductive techniques (singleton pregnancy); assisted reproductive techniques (twin pregnancy); and endometriosis) and one for PAS (hypertensive disorders of pregnancy). This is mainly caused by the different included articles. For example – regarding hypertension in pregnancy in PAS, we selected the latest study by Li et al. [44] rather than the one by Wang et al. [50] study. For endometriosis in PP, we chose the study by Matsuzaki et al. [24], not the one by Zullo et al. [51]. We determined by detailed evaluation and comparison that the two studies by Li et al. [44] and Matsuzaki et al. [24] are more recent and have higher quality (per the AMSTAR 2 tool), and are also more in line with our inclusion criteria.

VP is a rare but life-threatening obstetric disease, with an incidence from 0.46 to 0.60 for every 1000 deliveries, according to two systematic reviews [5,49]. Each effect size is relatively large for the six factors and four outcomes in VP. However, the epidemiologic evidence for this estimation was weak, mainly because the sample size of the included studies was too small. Therefore, more research is needed for this rare obstetrical condition. While three other systematic reviews and meta-analyses assessed VP [5,52,53], their topics were not related to and could not be evaluated in this umbrella review.

The previous review noted antepartum haemorrhage, postpartum haemorrhage, and septicaemia (among others) as adverse pregnancy outcomes for placental anomalies [8]. However, we did not find several of these outcomes in our review. Therefore, more systematic reviews and meta-analyses are needed to evaluate the effect of placental anomalies on other adverse pregnancy outcomes in the future.

The AMSTAR 2 tool assisted us in evaluating the methodological quality of the included studies. The most common flaw and reason for downgrading the quality assessment was the lack of protocol (n = 23). The most recent registration among the included studies took place in 2016. While preregistration of study protocols was an uncommon practice until recently, especially in the field of obstetrics, we found that implementing it could improve the quality of published meta-analysis.

To our knowledge, this is the first umbrella review to provide a broad overview of the scope and validity of the reported associations of various factors and pregnancy outcomes with placental anomalies, including PP, PAS, and VP. However, some limitations should be considered. First, our results exclusively rely on meta-analyses of observational studies, and are thus subject to the same limitations – including over/under-reporting, recall bias, and reverse causation. Second, because most of included meta-analysis were of low quality according to the AMSTAR 2 assessment, the results should be interpreted with caution. Third, we found an uneven covariate mix across primary studies, which could have affected our findings so that it might be difficult to assess both the effect size or its direction. Fourth, the results may not necessarily correspond well with the clinical studies. Finally, due to the lack of raw data, we are not able to conduct further analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

In this review, we provide a comprehensive overview and critical evaluation of the contributing factors and outcomes of placental anomalies. Across 55 factors and 16 outcomes, seven (five for PP and two for PAS) and 12 factors (four for PP, and eight for PAS) and six outcomes (for PP) showed high/moderate epidemiologic evidence for placental anomalies. The results can be used to reassure women or refer them to to pre-conception counselling clinics or antenatal clinics. Clinicians should consider and communicate these factors and outcomes when counselling their patients. Regarding future research, more broadly implementing the reporting criteria and registering observational studies that test hypotheses could help strengthen the evidence. Likewise, new meta-analyses are needed to obtain, evaluate, and validate the novel and strongest evidence.

Additional material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the efforts of all the researchers whose articles were included in this study.

Ethics statement: This study involved only literature review of previously published studies and the contained data. It involved no primary research on human or animal subjects, or medical records. As such, this work was considered exempt from ethical review.

Data availability: The study data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the 2023 Foshan Health Bureau Medical Scientific Research Project (No. 20230814A010028).

Authorship contributions: DF, ZL and XG participated in the design and coordination of the study. DF conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. DF, LS, and LL searched the databases and checked them according to the eligibility criteria and exclusion criteria. YM, DL, PL, ZZ and JR help develop search strategies. GC and JR analysed the data. DF, ZL and XG did the data management. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure of interest: The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jauniaux E, Silver RM.Rethinking Prenatal Screening for Anomalies of Placental and Umbilical Cord Implantation. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:1211–16. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Gronbeck L, Langhoff-Roos J.Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:208–18. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.01.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan D, Li S, Wu S, Wang W, Ye S, Xia Q, et al. Prevalence of abnormally invasive placenta among deliveries in mainland China: A PRISMA-compliant Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6636. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan D, Wu S, Wang W, Xin L, Tian G, Liu L, et al. Prevalence of placenta previa among deliveries in Mainland China: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5107. 10.1097/MD.0000000000005107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavalagantharajah S, Villani LA, D’Souza R.Vasa previa and associated risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100117. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver RM.Abnormal Placentation: Placenta Previa, Vasa Previa, and Placenta Accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:654–68. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenabi E, Salimi Z, Bashirian S, Khazaei S, Ayubi E.The risk factors associated with placenta previa: An umbrella review. Placenta. 2022;117:21–7. 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenabi E, Salimi Z, Salehi AM, Khazaei S.The environmental risk factors prior to conception associated with placenta accreta spectrum: An umbrella review. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022;51:102406. 10.1016/j.jogoh.2022.102406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vahanian SA, Lavery JA, Ananth CV, Vintzileos A.Placental implantation abnormalities and risk of preterm delivery: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:S78–90. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steane SE, Young SL, Clifton VL, Gallo LA, Akison LK, Moritz KM.Prenatal alcohol consumption and placental outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:607.e1–607.e22. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iacovelli A, Liberati M, Khalil A, Timor-Trisch I, Leombroni M, Buca D, et al. Risk factors for abnormally invasive placenta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:471–81. 10.1080/14767058.2018.1493453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horton J, Sterrenburg M, Lane S, Maheshwari A, Li TC, Cheong Y.Reproductive, obstetric, and perinatal outcomes of women with adenomyosis and endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:592–632. 10.1093/humupd/dmz012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karami M, Jenabi E.Placenta previa after prior abortion: a meta-analysis. Biomed Res Ther. 2017;4:1441. 10.15419/bmrat.v4i07.197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin XA, Liu YS.Association between placenta previa and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a meta-analysis based on 7 cohort studies. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:2146–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Nikolopoulos GK, Lytras T, Bonovas S.Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:647–659.e4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsilidis KK, Kasimis JC, Lopez DS, Ntzani EE, Ioannidis JP.Type 2 diabetes and cancer: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMJ. 2015;350:g7607. 10.1136/bmj.g7607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belbasis L, Bellou V, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA, Tzoulaki I.Environmental risk factors and multiple sclerosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:263–73. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70267-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinn S.A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19:3127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iqbal K, Iqbal A, Rathore SS, Ahmed J, Ali SA, Farid E, et al. Risk factors for blood transfusion in Cesarean section: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfus Clin Biol. 2022;29:3–10. 10.1016/j.tracli.2021.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busnelli A, Schirripa I, Fedele F, Bulfoni A, Levi-Setti PE.Obstetric and perinatal outcomes following programmed compared to natural frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2022;37:1619–41. 10.1093/humrep/deac073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuzaki S, Nagase Y, Ueda Y, Lee M, Matsuzaki S, Maeda M, et al. The association of endometriosis with placenta previa and postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3:100417. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuzaki S, Lee M, Nagase Y, Jitsumori M, Matsuzaki S, Maeda M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of obstetric and maternal outcomes after prior uterine artery embolization. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16914. 10.1038/s41598-021-96273-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karaçam Z, Kizilca Çakaloz D, Demir R.The impact of adolescent pregnancy on maternal and infant health in Turkey: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102093. 10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tandon P, Govardhanam V, Leung K, Maxwell C, Huang V.Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk of adverse pregnancy-related outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:320–33. 10.1111/apt.15587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenabi E, Fereidooni B.The uterine leiomyoma and placenta previa: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:1200–4. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1400003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balayla J, Desilets J, Shrem G.Placenta previa and the risk of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinat Med. 2019;47:577–84. 10.1515/jpm-2019-0116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sha T, Yin X, Cheng W, Massey IY.Pregnancy-related complications and perinatal outcomes resulting from transfer of cryopreserved versus fresh embryos in vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:330–342.e9. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinelli KG, Garcia EM, Santos Neto ETD, Gama S.Advanced maternal age and its association with placenta praevia and placental abruption: a meta-analysis. Cad Saude Publica. 2018;34:e00206116. 10.1590/0102-311x00206116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karami M, Jenabi E, Fereidooni B.The association of placenta previa and assisted reproductive techniques: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1940–7. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1332035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shobeiri F, Jenabi E.Smoking and placenta previa: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:2985–90. 10.1080/14767058.2016.1271405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang G, Murphy VE, Namazy J, Powell H, Schatz M, Chambers C, et al. The risk of maternal and placental complications in pregnant women with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:934–42. 10.3109/14767058.2013.847080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang QT, Chen JH, Zhong M, Xu YY, Cai CX, Wei SS, et al. The risk of placental abruption and placenta previa in pregnant women with chronic hepatitis B viral infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Placenta. 2014;35:539–45. 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grady R, Alavi N, Vale R, Khandwala M, McDonald SD.Elective single embryo transfer and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:324–31. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, Smith GC, Onwere C, Mahmood TA, et al. Risk of placenta previa in second birth after first birth cesarean section: a population-based study and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:95. 10.1186/1471-2393-11-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saraswat L, Bhattacharya S, Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya S.Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with threatened miscarriage in the first trimester: a systematic review. BJOG. 2010;117:245–57. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heslehurst N, Simpson H, Ells LJ, Rankin J, Wilkinson J, Lang R, et al. The impact of maternal BMI status on pregnancy outcomes with immediate short-term obstetric resource implications: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2008;9:635–83. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faiz AS, Ananth CV.Etiology and risk factors for placenta previa: an overview and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;13:175–90. 10.1080/jmf.13.3.175.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugai S, Haino K, Yoshihara K, Nishijima K.Pregnancy outcomes at maternal age over 45 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:100885. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.100885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhuo L, Wang Z, Yang Y, Liu Z, Wang S, Song Y.Obstetric and offspring outcomes in isolated maternal hypothyroxinaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023;46:1087–1101. 10.1007/s40618-022-01967-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jansen CH, van Dijk CE, Kleinrouweler CE, Holzscherer JJ, Smits AC, Limpens J, et al. Risk of preterm birth for placenta previa or low-lying placenta and possible preventive interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:921220. 10.3389/fendo.2022.921220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li L, Liu L, Xu Y.Hypertension in pregnancy as a risk factor for placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review incorporating a network meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023;307:1323–1329. 10.1007/s00404-022-06551-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jenabi E, Salehi AM, Masoumi SZ, Maleki A.Maternal Smoking and the Risk of Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res Int. 2022;2022:2399888. 10.1155/2022/2399888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuzaki S, Nagase Y, Takiuchi T, Kakigano A, Mimura K, Lee M, et al. Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum after in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9205. 10.1038/s41598-021-88551-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hou YP, Lommel L, Wiley J, Zhou XH, Yao M, Liu S, et al. Influencing factors for placenta accreta in recent 5 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35:2166–2173. 10.1080/14767058.2020.1779215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roque M, Valle M, Sampaio M, Geber S.Obstetric outcomes after fresh versus frozen-thawed embryo transfers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2018;22:253–60. 10.5935/1518-0557.20180049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruiter L, Kok N, Limpens J, Derks JB, de Graaf IM, Mol B, et al. Incidence of and risk indicators for vasa praevia: a systematic review. BJOG. 2016;123:1278–87. 10.1111/1471-0528.13829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W, Fan D, Wang J, Wu S, Lu Y, He Y, et al. Association between hypertensive disorders complicating pregnancy and risk of placenta accreta: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2018;37:168–74. 10.1080/10641955.2018.1498880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zullo F, Spagnolo E, Saccone G, Acunzo M, Xodo S, Ceccaroni M, et al. Endometriosis and obstetrics complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:667–672.e5. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W, Geris S, Al-Emara N, Ramadan G, Sotiriadis A, Akolekar R.Perinatal outcome of pregnancies with prenatal diagnosis of vasa previa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57:710–9. 10.1002/uog.22166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitchell SJ, Ngo G, Maurel KA, Hasegawa J, Arakaki T, Melcer Y, et al. Timing of birth and adverse pregnancy outcomes in cases of prenatally diagnosed vasa previa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:173–181.e24. 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.