Abstract

Inhaled crystalline silica causes inflammatory lung diseases, but the mechanism for its unique activity compared to other oxides remains unclear, preventing the development of potential therapeutics. Here, the molecular recognition mechanism between membrane epitopes and “nearly free silanols” (NFS), a specific subgroup of surface silanols, is identified and proposed as a novel broad explanation for particle toxicity in general. Silica samples having different bulk and surface properties, specifically different amounts of NFS, are tested with a set of membrane systems of decreasing molecular complexity and different charge. The results demonstrate that NFS content is the primary determinant of membrane disruption causing red blood cell lysis and changes in lipid order in zwitterionic, but not in negatively charged liposomes. NFS-rich silica strongly and irreversibly adsorbs zwitterionic self-assembled phospholipid structures. This selective interaction is corroborated by density functional theory and supports the hypothesis that NFS recognize membrane epitopes that exhibit a positive quaternary amino and negative phosphate group. These new findings define a new paradigm for deciphering particle-biomembrane interactions that will support safer design of materials and what types of treatments might interrupt particle-biomembrane interactions.

Keywords: Silica, Quartz, Phospholipid, Liposome, Membrane, Macrophage

1. Introduction

The interaction between organized surfaces of materials and biological matter can be defined by interfacial chemistry and molecular recognition patterns. From a molecular point of view, the occurrence of a few specific chemical and/or structural surface features regulates the interactions between biological environments and exogenous materials [1], from vaccine adjuvants [2], to nanoparticles [3]. Inhaled particles represent a relevant class of materials that result in specific interactions with lung cells and tissues upon deposition in the respiratory tract. The crosstalk that is established between inhaled particles and lung cells defines the fate of the particle within the respiratory tract, and this process might result in particle clearance or long-term retention in the body [4,5].

Silica is one of the most abundant materials on Earth and is extensively used, both in crystalline and amorphous form, for industrial productions and processes, including catalysis and biomedical applications [6,7]. In these surface-driven processes, silica is conveniently exploited because of the vast number of different chemical features that characterizes its surface. Surface features impart specific chemical behavior, including surface charge, acidity, and reactivity. This specific reactivity offers opportunities for industrial application and, at the same time, influences the bioactivity of each silica material and the interactions with lung cells.

It is well known that exposure to respirable crystalline silica can cause pulmonary diseases, such as lung cancer and silicosis, which is still the most common occupational disease in the world [8,9]. However, a great variability of toxic responses to different sources of silica particles has been reported and assigned to the material variability both in its bulk and surface properties. Crystallinity, particle size, crystal fracturing, synthetic routes, surface hydrophobicity and/or reactivity have been suggested to play a role in silica toxicity [10]. The same variability in toxicity effects has been recognized for amorphous silica [11]. Despite amorphous silica being not classifiable as to its carcinogenic activity in humans [12], transient inflammatory responses and increased collagen deposition in the lungs have been observed in mice upon repeated dose administration of one type of amorphous silica, i.e., pyrogenic silica [13,14]. In particular, it has been observed that the toxicity of pyrogenic amorphous silica can vary by adjusting the synthesis conditions [15].

We recently investigated the hypothesis that the variable toxic activity of silica may be related to the heterogeneity of its surface chemistry. Although crystalline and amorphous silica largely differ in their bulk structure, the two forms are similarly disordered at the surface. In fact, the long-range ordering of the quartz crystal lattice is lost at the surface, because of the milling process and thermal treatments that are used to industrially prepare quartz dust [16,17]. The surface of both crystalline and amorphous silica appears to be characterized by similar disordered families of surface moieties, namely the siloxane bridges (☰Si–O–Si☰) and the silanols (☰Si–OH, >Si(OH)2), in a well-characterized relative spatial arrangement [18,19]. Silanols are more reactive than siloxanes and can form variable patterns of mutual silanol-silanol interactions, which depend on their structural (dis-)organization and inter-silanol distance [20].

Knowledge of the biomolecular mechanisms of crystalline and amorphous silica toxicity has dramatically advanced in the last few years [21] and a debate is currently unfolding on which surface feature is responsible for initiating the adverse outcome pathway (AOP) of the lung diseases caused by silica [22–24]. The role of the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in silica-induced inflammation, which is the pathogenic feature underlying silica-associated diseases, has been elucidated [25–27]. When silica is phagocytized by alveolar macrophages (AM), particles are transported into lysosomes. Silica may permeabilize the lysosome membrane, which leads to the release of lysosomal enzymes into the cytoplasm, inflammasome activation, and release of active pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic mediators. The membranolytic activity induced by silica correlates well with inflammation and represents the molecular initiating event of the AOP proposed for silicosis and lung cancer [25,28–30]. Some of us recently outlined a correlation between the membranolytic activity of crystalline and amorphous silica and the presence of a specific surface family of silanols [22]. These silanols were characterized by a very weak mutual inter-silanol interaction and therefore they were called “Nearly Free Silanols” (NFS). The inter-silanol distance of a NFS pair was estimated ranging from 4 to 6 Å and revealed that this specific silanol arrangement offers the optimal interatomic distance for the formation of a double hydrogen bond with the phospholipid headgroup of a model lipid membrane molecule. We suggested that pairs of NFS render the silica particles able to permeabilize the lysosome membranes of AM, and to initiate lung inflammation in a rodent model [22,31]. NFS are generated at the surface of both amorphous and crystalline silica during synthesis and upon fracturing, respectively. NFS-free quartz crystals can be synthesized by sol-gel synthesis [32], and they were shown not to induce membranolysis, nor activate pro-inflammatory responses in in vitro and in vivo tests [31,33].

The pivotal role of NFS in determining the silica-induced membrane damage suggests the existence of a molecular recognition pattern between specific phospholipid headgroups and NFS. To test this hypothesis, we have here utilized a set of crystalline silica particles and one amorphous silica, characterized by differential expression of surface NFS and particle size. The particles were tested with membrane systems of decreasing molecular complexity, from composite cellular membranes to molecular structures of only phospholipids (PLs). Red blood cells (RBCs), a convenient model for non-internalizing cells, were used to assess the direct membranolytic effect of the silica particle set. Zwitterionic and negatively charged, small (100 nm) and medium sized (500 nm) liposomes were used to evaluate the role of membrane charge/steric hindrance on the molecular recognition mechanism between NFS and PL headgroups. The same PLs, assembled in self-assembled structures that mimic the uncontrolled size conditions that can be encountered in the lung fluid upon particle inhalation [34], were adsorbed on the silica surface to assess the specificity and reversibility of the interaction between NFS and polar heads in aqueous media. Density functional theory (DFT) modelling of the interaction between PLs and NFS elucidated their energetics and structures.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Silica particles

As-grown quartz crystals (gQ) were synthesized by hydrothermal synthesis as previously described [32]. Each synthetic lot was verified for crystallinity by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. For gQ, synthetic quartz (1.0 g) was sieved in a 100- and 30-μm meshes double sieve on a vibrating apparatus for 30 min and the fraction < 30 μm was used. For fractured quartz (gQ-f), synthetic quartz (0.5 g) was ground in a mixer mill (Retsch MM200) in an agate jar, with two agate balls of 6 mm diameter, at 27 Hz for 6 h. For fine fractured quartz (gQ-ff), synthetic quartz (1.5 g) was ground in a planetary mill (FRITSCH P6) in a zirconium oxide jar, with zirconium oxide balls (41 g) of 5 mm diameter, at 450 rpm for 1 h. Synthetic amorphous silica (aS) of pyrogenic origin was kindly supplied by industrial manufacturers. The mineral quartz Min-U-Sil 5 (U.S. Silica, Berkeley Springs, WV) was used as a positive reference particle (cQ-f) because of its well-documented membranolytic activity and toxicity [12].

2.1.2. Lipids and other reagents

All phospholipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL) in chloroform or powder form for liposome or PL adsorption tests, respectively. The lipids used were 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine sodium salt (DOPS) (Table S1). The aminonaphthylethenyl–pyridinium dye Di-4-ANEPPDHQ, which served as the fluorescence probe, was from ThermoFisher (Waltham, MA). RBCs were obtained from sheep blood in Alsever’s solution (Oxoid, UK). Phosphate buffer solution (PBS) and Triton-X 100 were purchased from Merck (Sigma-Aldrich, DE), 0.9% NaCl from Eurospital (IT). Ultrapure Milli-Q water (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used throughout.

2.2. Particle physico-chemical characterization

Particle morphology was assessed by Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) with a TESCAN S9000G equipped with a Schottky FEG source at various magnifications and accelerating voltages, commonly 15 kV and 100 pA. Dry silica particles were deposited on conductive stubs and coated with gold to prevent the electron beam from charging the sample. Crystallinity was assessed by XRD in Bragg-Brentano configuration with a Rigaku Miniflex 600. Spectra were collected in the range (3–90°), with a step width of 0.01°, 10 ° min−1 of speed, and Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 15 mA. The diffractograms were compared with the National Institute of Standards and Technology Standard Reference Material 1878b (Respirable Alpha Quartz) pattern. The Specific Surface Area (SSA) of the particles was evaluated by the Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller (BET) method, using an ASAP 2020 apparatus (Micromeritics). Samples were first outgassed at 150 °C for 2 h. Depending on the expected SSA, Kr (SSA ≤ 5 m2 g−1) or N2 (SSA > 5 m2 g−1) adsorption at − 196 °C was measured. For assessment of particle size and surface charge, stock dispersions of each silica sample (1.0–5.0 mg mL−1) were prepared in media just before use. Quartz samples were sonicated for 2 min in an ultrasound bath (FALC Instruments) and aS for 1 min on ice with an ultrasonic probe (horn, 3 mm; frequency, 20 kHz; maximum power output, 25 W; amplitude, 120 μm; Sonopuls HD 3100, Bandelin). The size distribution of quartz samples was measured by Flow Particle Image Analysis using a FPIA-3000S (Malvern Instruments; detection range: 0.8–160 μm). Particle dispersions (1.0 mg mL−1 in water) were injected (ca. 5 mL) into the measurement cell and stirred at 360 rpm. Data were processed by the Sysmex FPIA software (version 00–13). The hydrodynamic diameter of aS and gQ-ff diluted dispersions (0.1 mg mL−1 in water or 0.01 M PBS) was assessed by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments). The same equipment was used to assess the particle surface charge (ζ potential) of silica dispersions diluted in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4) by Electrophoretic Light Scattering (ELS). At least three independent measurements were performed for each sample, three runs for each measurement.

2.3. Hemolytic activity in absence or presence of PLs

The protocol for hemolysis tests refers to [22] with modifications described in the Supplementary material.

2.4. Preparation of liposomes and assessment of time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy

Each respective lipid dissolved in chloroform was dried under a stream of nitrogen gas for ca. 1 h. The dry lipid film was then hydrated with Tris-buffered saline (TBS, 50 mM tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) and sonicated in a bath sonicator for 10 min. The hydrated lipid solution was then passed through an Avanti Mini-Extruder with appropriately sized filter for 15 extrusions. During preparation, the lipids were kept 10 °C above their respective transition T with a heated water bath or heating block. The size and ζ potential of the liposomes was determined using DLS. Silica particle doses ranged from 200 to 600 μg mL−1. This range was determined not to cause confounding light scatter in the anisotropy experiments. Higher doses of silica cause light scatter, which biases the fluorescence decay data. When incubated with silica particles, liposomes were placed at 37 °C with tumbling for 2 h. The fluorescence probe, Di-4-ANEPPDHQ, is solvatochromic and partitions into both the ordered and disordered phases of the membrane. It has also displayed sensitivity to lipid order in cells and model systems [35–38]. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ was prepared in spectral grade dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted to a 250 μM stock in TBS. The final working concentration of Di-4-ANEPPDHQ was at 400 nM (final DMSO concentration <1%) and was added 15 min prior to data collection at room temperature. Fluorescence measurements were taken on a custom-built fluorimeter assembled using parts obtained from Quantum Northwest as previously described [39]. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ was excited with a 470 nm pulsed diode laser (LDH-P-C-470; PicoQuant). Fluorescence emissions passed through a Chroma 500 nm longpass filter and detected using an Edinburgh Instruments photomultiplier tube (H10720–01). All measurements were taken from a temperature-controlled chamber at 20 ± 0.02 °C. Anisotropy decay measurements were fitted and analyzed using FluoFit v4.6.6 (PicoQuant). The anisotropy parameter is determined by Eq. 1.

| (1) |

where and represent the intensities of the vertically and horizontally polarized emission decays, respectively. The anisotropy is defined by the value, r. The total fluorescence intensity is defined by the term .

The range of motion of Di-4-ANEPPDHQ was then calculated by a wobble-in-a-cone angle, as shown in Eq. 2 [40]:

| (2) |

where S, the order parameter, represents the order of a lipid membrane and is calculated by the ratio of . The initial anisotropy in a lipid membrane is , while the residual anisotropy that the fluorescence probe decays to is the term, . This relationship between and can be used to establish a range of motion of the fluorescence probe, or a wobble-in-a-cone angle, .

2.5. IR spectroscopy

IR measurements were carried out in the transmission mode. Aliquots of the sample particles were pressed in self-supporting pellets and placed in a quartz cell equipped with CaF2 windows. The FTIR spectra were recorded with a Bruker INVENIO R FTIR spectrometer (liquid nitrogen cooled MCT detector; resolution, 4 cm−1) by averaging 128 scans to attain a good signal-to-noise ratio. The cell was attached to a conventional vacuum line (residual pressure ≤ 1 × 10−4 mbar) allowing adsorption–desorption experiments to be carried out in situ. As detailed previously [22], the silica samples underwent an hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) isotopic exchange by adsorption/desorption of D2O (99.90% D) to convert surface silanols (☰SiOH) in the ☰SiOD form.

2.6. Computational details

All structures shown in Fig. 4 have been pre-optimized at GFN2 [41] level using the xTB code [42] and subsequently refined at B97–3c [43] level using the ORCA code [44]. This level of theory has been shown to be well suited for structures where non-bonded interactions are dominant, as in the present case. All considered systems have been optimized by embedding in a continuous solvent (water) using the CPMC methods [45], to represent, at least in part, the water environment in which the experiments have been carried out. This approach, albeit unable to consider specific local interactions like hydrogen bonds, allows for a reasonable estimate of the solvation energy.

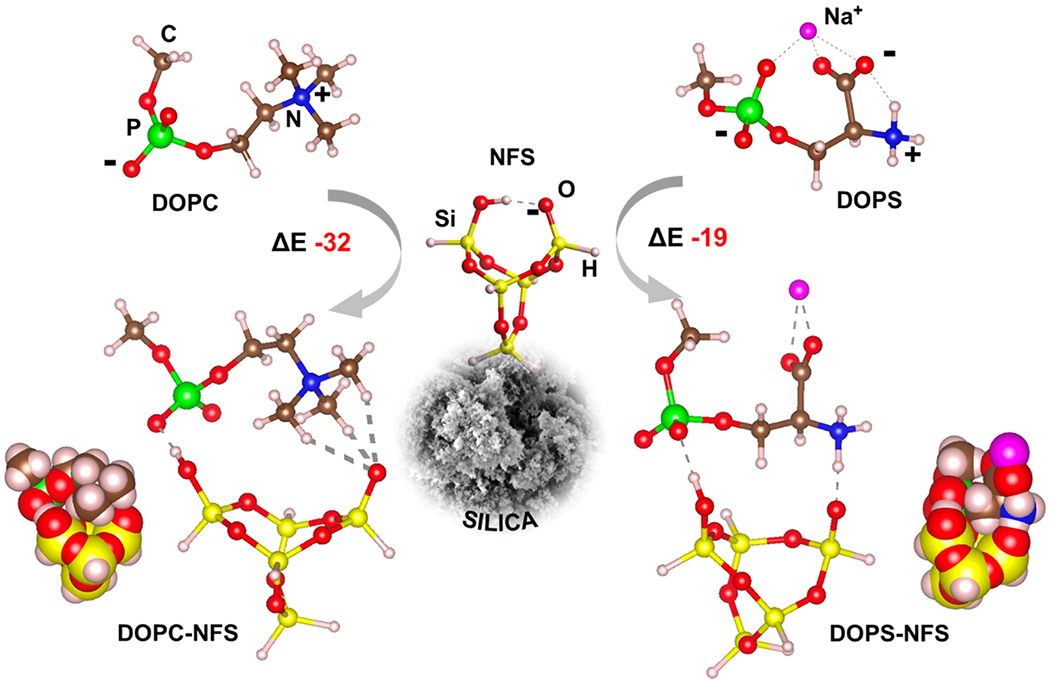

Fig. 4.

Adopted models for PLs (DOPC and DOPS) and the NFS silica site. For DOPS, Na+ counterion is added to neutralize the structure. NFS cradle (at figure center) shows the deprotonated silanol tail and the strong inter-NFS hydrogen bond (dotted line). The energies of interactions (ΔE) between DOPS/DOPC and NFS are reported in unit of kJ mol−1. The van der Waals representations (bottom sides) highlight the most favorable dispersion interactions of DOPC with respect to DOPS.

2.7. Statistics

The data shown are means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Data were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test, as appropriate. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The GraphPad Prism 9.1.1 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used to perform statistical analysis.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Physico-chemical characteristics of silica particles

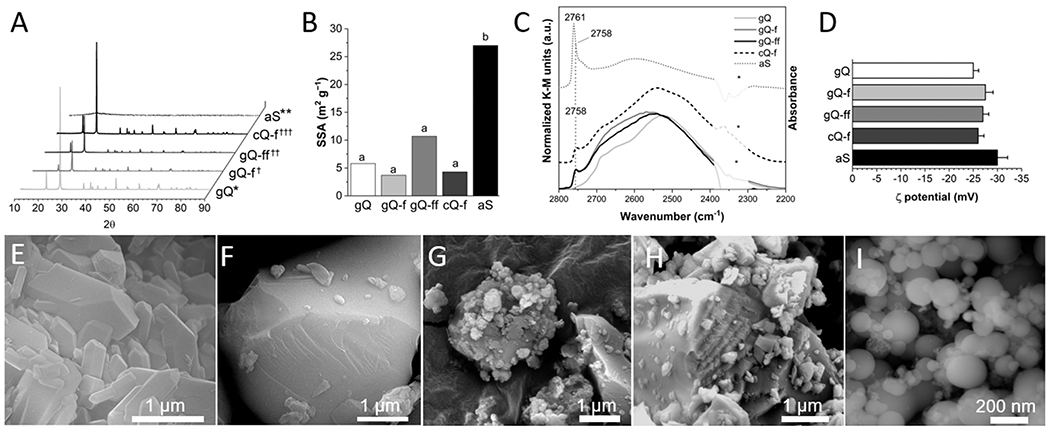

The physico-chemical characteristics that are relevant for silica toxicity originate from a small number of surface properties, including particle size/aggregation, surface charge/functionalization, and silanol distribution. We controlled these properties to produce a set of silica particles with respirable size (d90 < 4 μm) that were differentiated for NFS occurrence and surface area/particle size distribution (Fig. 1 and Supplementary material: Table S2, and Fig. S1 to S3). Pure synthetic quartz (gQ; “g”: as-grown) [32] and its fractured counterpart (gQ-f) showed similar crystal structure (Fig. 1 A), particle size distribution (Table S2) and specific surface area (Fig. 1B) and differed for the low and high amount of surface NFS, respectively (Fig. 1 C). The fractured quartz showed the typical conchoidal planes of breakage on its surface (Fig. 1 F and Fig. S1) that were not observed on the smooth and regular surfaces of as-grown quartz (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1). Synthetic quartz was also fractured in a high-energy ball mill and a crystalline powder (Fig. 1 A), with higher SSA than gQ-f (Fig. 1B), was obtained (gQ-ff). In dry powder form, gQ-ff showed highly aggregated nanoparticles that adhered to larger particles (Fig. 1 G and Fig. S1). Despite its higher surface area, the particle size distribution of gQ-ff was similar to gQ-f (Table S2 and Fig. S2), signaling that the high surface area might not be completely available for interaction with biomolecules in aqueous media. An amorphous silica (aS) (Fig. 1 A) of pyrogenic origin was included as a model for low-hydroxylated (ca. 1.5 OH nm−2) [46], high-SSA (27.0 m2 g−1) (Fig. 1B) silica powder which exhibited primary particle size in the nanometric range, with regular, smooth, and roundish morphology (Fig. 1I and Fig. S1). In aqueous suspension, aS was slightly aggregated with average aggregate size of 350 nm (Fig. S3). A mineral quartz dust of commercial origin (cQ-f) completed the set and was used here as a reference material due to its well-known toxic activity [12]. As expected, when the surface silanol profile was assessed by IR spectroscopy after H/D exchange (thus, the νO-D stretching vibration of only surface silanol is revealed, see [22] for further details), all fractured quartz dusts showed the presence of surface NFS that are generated during fracturing (Fig. 1 C). This is evidenced by an increase of the intensity of the spectral components at νOD > 2735 cm−1. Significantly, the narrow component at 2758 cm −1 was not observed on synthetic as-grown quartz. Amorphous silica, which was not fractured, also expressed surface NFS that are generated during the pyrogenic production process. Pyrogenic silica was previously shown to express surface NFS and exhibited highly membranolytic [22] and inflammatory activity, in vitro and in vivo [23].

Fig. 1.

Main physico-chemical properties of the selected quartz and amorphous silica particles. (A) XRD patterns of quartz and amorphous silica particles, i.e., as-grown synthetic quartz crystals (gQ), fractured as-grown quartz (gQ-f), finely fractured as-grown quartz (gQ-ff), mineral quartz Min-U-Sil 5 (cQ-f), and amorphous pyrogenic silica (aS). Sample origin and processing: *hydrothermal sol-gel synthesis [32], * * pyrolytic synthesis from methylsiloxane and raw silicates; †milled in a mixer mill in agate jars, ††milled in a planetary ball mill in a zirconium oxide jar, †††used as received. (B) SSA analysis: a, Kr-BET method, b, N2-BET method. (C) Surface silanol distribution measured by IR spectroscopy after H/D isotopic exchange. Reflectance IR spectra recorded for quartz particles and reported in Kubelka-Munk function; IR spectra of aS recorded in transmission mode and reported in absorbance (data from [22] - except gQ-ff and aS, from this work). The peak at 2758 cm−1 of gQ-f, gQ-ff, cQ-f, and aS is assigned to nearly free silanols (NFS). In aS, the wavelength of the main peak is shifted at 2761 cm−1 due to the coexistence of NFS and isolated silanols. *not compensated CO2. (D) ζ potential measured by ELS in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4). (E-I) FE-SEM micrographs of (E) gQ, (F) gQ-f, (G) gQ-ff, (H) cQ-f, and (I) aS.

When suspended in culture media at pH 7.4, all investigated silica particles exhibited a markedly negative zeta potential (Fig. 1D) due to the deprotonation of surface silanols. Indeed, when quartz is suspended in aqueous solution an equilibrium is readily established between protonated and dissociated silanols [6], as silanols are weak monoprotic Brønsted acidic sites (Eq. 3).

| (3) |

The pKa values of these surface moieties, which depends on the local characteristics of each silanol group [47], are low enough to determine a large deprotonation ratio at physiological pH and impart net negative charge to the silica surface [10].

3.2. Silica with different NFS contents elicit different membrane perturbation

To investigate the specificity of the interaction between silica and cell membranes, we used RBC, a non-internalizing cell and a well-established model for silica inflammatory activity [28,48,49]. The highly elastic RBC membrane - deformation may be up to 250% of its linear extension - is very sensitive to small increases of surface area [50], and an increase as low as 4%, induced by the interaction with silica, might result in cell lysis. The outer lipid layer of the RBC membrane is constituted by two main phospholipid classes, namely phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin (SM), which exhibit phosphocholine as polar group (Fig. 2B). At physiological pH, both PC and SM are neutral due to the zwitterionic nature of their phosphate and quaternary amine groups. The RBC membrane also contains a number of sialylated glycoproteins. The sialic acid terminal residue (N-acetyl neuraminic acid, NANA) is exposed at the cell surface and the ionization of the carboxyl group of NANA confers to RBC an average negative ζ potential at physiological pH of ca. − 31.8 mV [51] that attracts positive ions (mainly Na+) and polarizes water molecules at the interface. This negative electrochemical potential is at the basis of the well-known intercellular repulsion that prevents agglutination of RBCs [50]. Silica particles, which exhibit size and a surface potential that are comparable with RBC, may experience similar repulsive forces. This implies that, to induce membranolysis, the interaction between silica particles and RBC must somehow overcome the electrostatic repulsion established between charged sialic residues and deprotonated silanols at the silica surface.

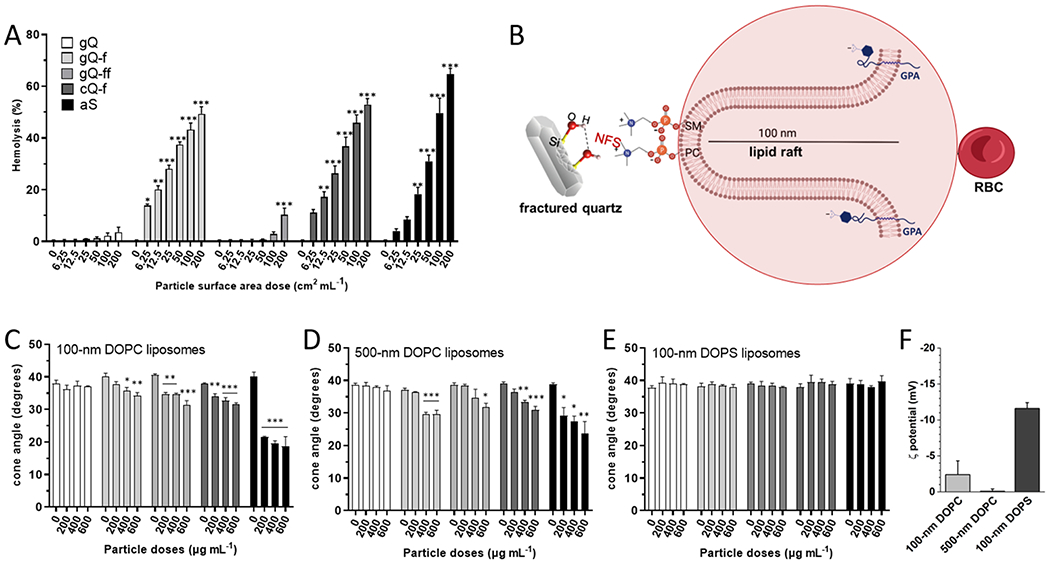

Fig. 2.

Red blood cell membrane lysis and cone angle deformation of DOPC and DOPS liposomes induced by different silica particles. (A) Hemolytic activity of the silica particles incubated with red blood cells. Hemoglobin released from RBCs treated with increasing surface area doses (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 cm2 mL−1) of gQ, gQ-f, gQ-ff, cQ-f (positive reference quartz), and aS for 30 min. Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments and were analyzed with one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, * *p < 0.01, * **p < 0.001 vs. control not exposed to silica particles. (B) Schematic representation of the RBC membrane structure evidencing the major syaloglycoprotein (Glycophorin A, GPA) that confers negative charge to the outer membrane; a sphingomyelin-enriched lipid protrusion deprived of GPA, where SM and PC are evidenced. Phosphocholine polarheads might interact with NFS on silica. (C) Cone angle deformation of liposomes incubated with the silica particles. Cone angle deformation of (C) 100 nm DOPC, (D) 500 nm DOPC, and (E) 100 nm DOPS liposomes treated with gQ’ gQ-f, gQ-ff, cQ-f, and aS for 2 h. Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments and were analyzed with one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, * *p < 0.01, * **p < 0.001 vs. control not exposed to silica particles. (F) ζ potential measured by ELS in experimental medium at pH 7.4.

To test this hypothesis, we investigated the lytic interaction of silica particles with purified RBC (Fig. 2 A). All NFS-rich silica particles exhibited a strong hemolytic activity at doses as low as 6.25 cm2 mL−1. As-grown quartz (gQ), with a low NFS content, was non-hemolytic. Interestingly, finely fractured quartz (gQ-ff) was hemolytic only at the highest dose tested (200 cm2 mL−1). This latter sample differs from gQ-f only by the milling conditions and exhibits a similar NFS sub-population (Fig. 1 C). The hemolysis data imply that particle morphology (i.e., a combination of size, curvature, and/or aggregation) may significantly modulate the lytic activity of NFS-rich silica surfaces. The relatively high surface area of gQ-ff (10.7 m2 g−1, about 2–3 times larger than gQ-f and cQ-f, Fig. 1B) and the similar particle size distribution (Table S2) account for a significant aggregation and polydispersion (Fig. S2) of this sample. Therefore, the hemolytic activity of gQ-ff - assessed by dosing equal surface areas - could be lower than what was expected due to the strong aggregation of the particles that effectively decreases the available surface area for the interaction with RBC membrane. The effect of gQ-ff is consistent with similar conclusions drawn for nanosilica aggregates interacting in vitro with human bronchial epithelial cells, macrophages, and RBC [11,52].

Sphingomyelin-enriched lipid domains were recently observed to form nanoscale protrusions or “lipid rafts”, which can be as high as 100 nm from the RBC surface [53]. RBC lipid rafts, which differ in lipid and protein content from the rest of the membrane [54], are enriched in order-preferring lipids, i.e., sphingomyelin and glycosphingolipids, and depleted in sialylated glycoproteins [55]. Due to the excess of SM, which exhibits a zwitterionic choline, the local charge of lipid rafts is lower than the rest of the RBC membrane. Lipid rafts, that similarly occurs in endosomes/lysosomes, impart differential mechanical properties to cells, and seem to be involved in the cellular interaction with particles [56]. The height and the lower charge of lipid rafts suggest that these protruding domains, enriched with choline residues, might represent a favored region for the interaction with the negatively charged NFS site on silica.

3.3. Silica particles differently interact with zwitterionic (DOPC) and anionic (DOPS) liposomes

To analyze the effect of membrane charge on the interaction with silica, two controlled liposome model systems were used. PLs shared the same lipid chain (dioleoyl, DO) and differed only in the polar headgroups (Table S2). Specifically, phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylserine (PS), which account for ca. 25 and 12 mol% of the PLs in the erythrocyte membrane respectively [57], were used to prepare liposomes. At the experimental pH (7.4), PC and PS are both highly polar but exhibit different net charges (Fig. 2 F). PC is characterized by a positively charged quaternary amine that balances the negative charge of phosphate, thus rendering the PC polar head electrically neutral. The positive charge on PC is mainly formalized on N, though some of the positive charge is also distributed on the three methyl groups [58]. The net negative charge of PS is due to the presence of a carboxylic acid residue on the phosphoethanolamine headgroup. The differentiation in polarity and local charge distribution of the two PLs may, in our hypothesis, lead to different interactions with negatively charged silanols at silica surface and therefore explain the membranolytic effect observed for silica. We measured changes to membrane order that was caused by interaction with silica particles by assessing time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy of a lipophilic fluorescence probe, Di-4-ANEPPDHQ, embedded in liposome membrane. Time-resolved anisotropy measures the rate of fluorescence depolarization of a fluorophore. In lipid membranes, this depolarization can be a measure of lipid order and can be used to describe the ability of particles to alter membrane conformational arrangement [35,36]. A decrease in the fluorophore anisotropy signals a restriction in lipid motion and accounts for an increase in membrane lipid order caused by the interaction of silica with outer polar groups of the PLs. Anisotropy data from 100 nm and 500 nm DOPC, and 100 nm DOPS liposomes (size distribution reported in Fig. S4) incubated with different silica doses for 2 h are reported in Fig. 2 C, D, and E, respectively. All the NFS-rich silica particles, but not the low-NSF gQ, produced a significant decrease of the cone angle of Di-4-ANEPPDHQ incorporated in 100 nm DOPC liposomes. The most pronounced effect was observed for amorphous silica (aS) that reached the maximum perturbative effect on DOPC liposome structure already at the lowest dose (200 μg mL−1). As data were collected per unit mass of silica, the most pronounced effect of aS can be correlated to the high surface area exposed by this nanometric sample (27.0 m2 g−1). The fractured quartz particles (gQ-f, cQ-f) induced lower but statistically significant modifications of the cone angle at similar doses. A larger perturbative effect was expected for gQ-ff, due to its high specific surface area (10.7 m2 g−1). However, the relatively low perturbation induced on 100 nm DOPC liposomes suggests that gQ-ff is able to exert a lower effect on membranes, on a per unit area basis. This consideration is consistent with the low membranolytic activity exhibited by gQ-ff in the hemolysis tests and accounts for the occurrence of large agglomerate particles in this sample. All observed changes to the cone angle of Di-4-ANEPPDHQ were decreased, which indicates increased lipid order. This increase in lipid order is likely generated by the interactions between the silica surface and phospholipid headgroups that restricts motion of the lipids. Similar effects were seen in other studies with engineered nanomaterials and lipid model systems in which lipid order and local gelation occurred as a result of an interaction or adsorption between the material and lipids [36,59].

As larger liposomes exhibit different curvatures, which can change the orientation of phospholipids within the vicinity of silica surface, DOPC liposomes were also extruded through a 500 nm filter. Fig. 2D displays changes to the cone angle of Di-4-ANEPPDHQ embedded in 500 nm DOPC liposomes upon contact with silica. Crystalline and amorphous NFS-rich silica (gQ-f, cQ-f, and aS) induced similar cone angle decreases on these larger liposomes. Unfractured, low-NFS gQ confirmed the negligible effect on 500 nm DOPC membrane structural arrangement at all doses. The gQ-ff, despite its higher surface area, induced a significant perturbation of the 500 nm liposome membrane only at the highest dose, thus showing a lower perturbative action than what was induced on 100 nm DOPC liposomes. This result supports the lower activity of gQ-ff towards larger membranes, which again is consistent with the outcome of the hemolysis assay. Specifically, this finding indicates that the interaction between NFS and PLs on membranes might be also influenced by membrane curvature.

All silica particles were next tested on DOPS-prepared liposomes extruded at 100 nm (Fig. 2E). All silica particles, including amorphous silica, were not able to induce a significant perturbation in DOPS liposome membrane. These data clearly indicate that negligible molecular interactions are established between the DOPS polar groups and silica surfaces, in the current experimental conditions. The comparison with the dramatic cone angle changes induced by the very same materials on DOPC liposomes indicate that the different charge distribution exhibited by the two PLs strongly modulates the interaction with silica negatively charged surface. This finding supports the proposed hypothesis for the interaction between RBC and silica, with the involvement of lipid rafts (see Fig. 2B) that are either richer in zwitterionic lipids or are far enough from the negative surface of cell membrane. Similarly, other publications have reported that engineered nano-material interactions with lipid membranes are influenced by surface charge of both the material and the phospholipids in the membrane along with salt concentration and pH. These factors can dictate material adsorption to the membrane, changes to lipid order, and membrane leakage [36,59,60].

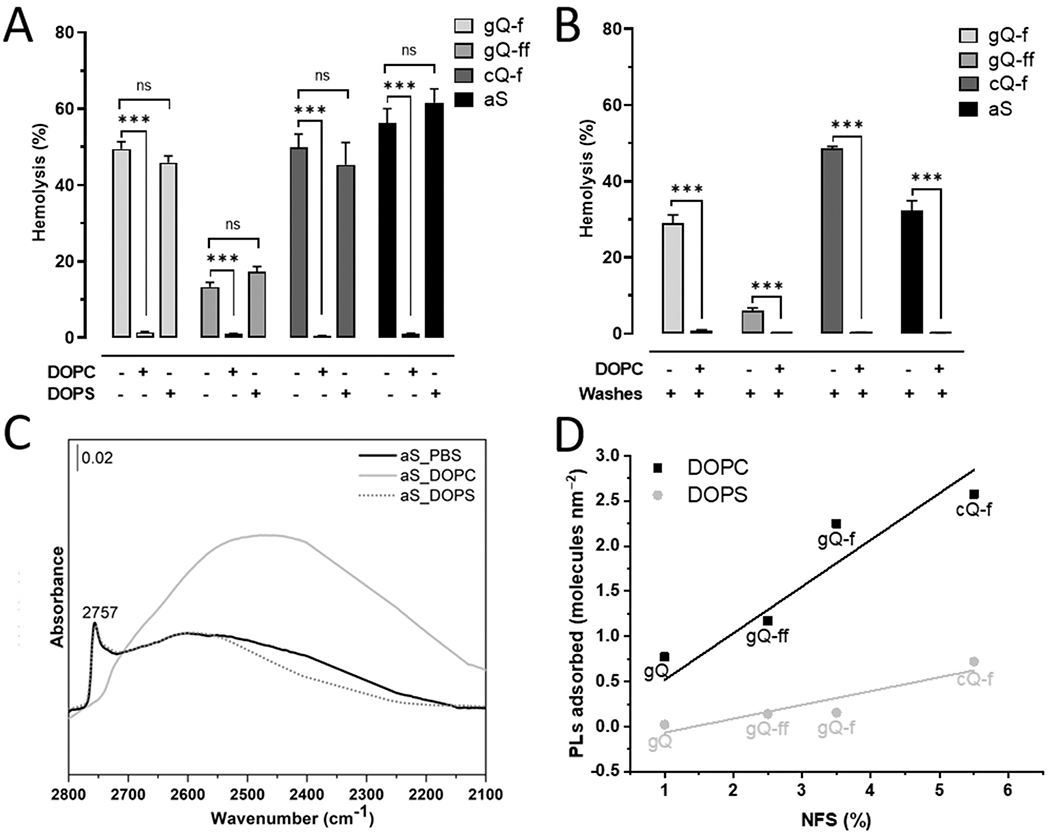

3.4. Silica particles irreversibly adsorb self-assembled DOPC, but not DOPS, and the interaction is specific for NFS

The selective interaction of the DOPC liposomes and, conversely, the negligible interaction of the DOPS liposomes, with the silica surface should result in opposite adsorption affinity of the phospholipids on silica and induce different modifications of the silica bioactivity. Therefore, we tested the hemolytic activity of the particles in presence of self-assembled DOPC or DOPS structures (size distribution for self-assembled lipid structures is reported in Fig. S5). Experimental PL concentrations ranged from 10−5 to 10−1 mg mL−1. DOPC, but not DOPS, reduced the membranolytic activity of the four hemolytic silica particles (gQ-f, gQ-ff, aS, and mQ-f) in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. S6), and completely inhibited hemolysis at the highest concentration tested (Fig. 3A). As expected, DOPS did not significantly reduce the hemolytic activity of the particles, even at the highest concentration (Fig. 3A and Fig. S6). The strong affinity for NFS-rich silica surface that is exhibited by DOPC was confirmed by performing the hemolysis experiment on DOPC-coated silica particles that were washed three times with culture media prior incubation with RBC. Even after washing, the quenching of the hemolytic activity of DOPC-coated silica was observed (Fig. 3B). This finding suggests that DOPC is irreversibly adsorbed on NFS-rich silica surfaces. These results are in line with the liposome cone angle deformation data reported above and support the establishment of a strong chemical interaction between silica and DOPC but not DOPS.

Fig. 3.

The interaction of silica particles with self-assembled DOPC, but not DOPS, is irreversible and specific for NFS. (A) Hemolytic activity of the silica particles in presence of self-assembled DOPC or DOPS. Hemolytic particles, i.e., gQ-f, gQ-ff, cQ-f (positive reference quartz), and aS were pre-incubated with just the vehicle (0.01 M PBS), or 0.1 mg mL−1 of DOPC or DOPS for 30 min. A suspension of 5% RBC was added and the hemolytic activity assessed after a further incubation of 30 min. Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments and were compared with a two-tailed Student’s t test. * **p < 0.001 vs. group without PLs, containing only silica. (B) Irreversible adsorption of DOPC inhibits the hemolytic activity of the silica particles. Hemolytic particles, i.e., gQ-f, gQ-ff, cQ-f (positive reference quartz), and aS were pre-incubated with the vehicle or 0.1 mg mL−1 of DOPC for 30 min. The mixture was centrifuged, supernatant removed, particles washed three times with PBS, and hemolysis assessed. Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments and were compared with a two-tailed Student’s t test. * **p < 0.001 vs. group without PLs, containing only silica. (C) Surface silanol distribution (transmittance IR spectra reported in absorbance) in the νOD spectral region (after H/D isotopic exchange and νOH spectra subtraction) of aS incubated with just the vehicle (0.01 M PBS), or 0.1 mg mL−1 of DOPC or DOPS for 30 min, washed three times with PBS, and dried. (D) Correlation between % NFS and adsorbed self-assembled PLs (molecules nm−2) for silica particles. Percent NFS relative to total silanols as calculated from deconvolution of IR spectroscopic features were compared by linear regression analysis with DOPC or DOPS (molecules nm−2) adsorption for each silica sample. Parametric linear regression analysis (DOPC: Pearson’s coefficient = 0.99; R2 = 0.97; DOPS: Pearson’s coefficient = 0.92; R2 = 0.78) was applied.

We hypothesized that adsorbed DOPC specifically masks the NFS sites, which are responsible for the silica hemolytic activity. This specific interaction was evidenced for aS, whose high specific surface area allowed to obtain spectra of self-supporting pellets of aS incubated with PBS, DOPC, and DOPS for 30 min, washed three times with PBS, and dried (Fig. 3 C and Fig. S7). The spectrum in the νOD domain of aS+PBS is clearly dominated by the surface NFS stretching band at 2757 cm−1. The relative intensity of the NFS band was reduced virtually to zero when DOPC irreversibly interacted with silica. The suppression of the vibrational mode of NFS indicates that all these molecular species at the silica surface are engaged in new strong interactions which shifted the vibrational frequencies down to lower wavenumbers. Those interactions are clearly related with the occurrence of irreversibly adsorbed DOPC molecules sitting at the silica surface. Consistently with data reported above, the interaction with DOPS did not modify the NFS adsorption band and the spectrum of aS+DOPS is largely superimposable with the aS+PBS spectrum.

We quantified the amount of the two PLs that irreversibly adsorbed on the silica surface by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (Supplementary Materials and Methods, Fig. S8, and Table S3). For all silica particles, DOPC irreversibly adsorbed in significantly larger quantities than DOPS, which confirms the selective interaction and the repulsive electrostatic forces established between surface silanols and PC and PS, respectively. A clear correlation (Pearson’s coefficient = 0.99) between the amount of DOPC irreversibly adsorbed and the relative quantity of NFS exposed at the silica surface was indeed observed. Fig. 3D shows the linear regression obtained by plotting the relative amount of NFS (% NFS, calculated in Table S4, and Fig. S9 and S10) versus the phospholipid molecules adsorbed per nm2 (Table S3) and support the existence of a specific recognition between NFS andDOPC. The relative amount of NFS exposed at gQ and gQ-f surface was 1.0% and 3.5% [22] and the amount of DOPC adsorbed was 0.77 and 2.25 molecules nm−2, respectively. The pyrogenic silica (aS), which exposes 17.3% NFS (Table S4 and Fig. S10), adsorbed a relatively low amount of DOPC and this is consistent with the lower amount of total silanol species of this type of silica (ca. 1.5 OH nm−2) with respect to quartz surface, which might exhibit up to 9.1 OH nm−2 [19]. Conversely, DOPS adsorbed in negligible amounts on all samples.

The opposite behavior of the two PLs is determined by the different functional groups contained in their polarheads. The zwitterionic phosphorylcholine of DOPC is electrically neutral at experimental pH and exhibits a quaternary amine (). The presence of the positively charged amine may suggest that the electrostatic interaction between dissociated NFS and is responsible for the membranolytic activity of silica. Pioneering work highlighted that the hemolytic activity of quartz is inhibited by adsorption of protein coupled with quaternary ammonium groups [61] and suggests that, for NFS-rich silica, a high selectivity for quaternary amines could be the molecular recognition pattern driving the described interaction, as observed for silica nanoparticles [62,63]. In parallel, hydrogen bonds could be established between the Si- OH of NFS and negative oxygen of phosphate groups, as described by experimental and theoretical considerations [64,65].

3.5. DFT modelling of the DOPC and DOPS phospholipids interaction with the NFS site

To gain a molecular insight of the possible interaction between the PLs and the silica surface, we simulated the NFS site by a small cluster containing the key silanol pair (a four membered Si-O ring, see NFS structure in Fig. 4), in which one silanol group of the NFS has been deprotonated, in agreement with the experimental pH condition (pH 7), under which some of the Si-OH of silica are deprotonated (see Fig. 1D). Therefore, the deprotonated silanol group is engaged in a strong hydrogen bond by the nearby Si-OH group. PLs have been represented with idealized structures (DOPC and DOPS in Fig. 4), in which the role of the hydrophobic tail is played by a single CH3 group attached to the PO4 moiety. In this way, we assumed that the dipalmitoyl lipophilic tail, which is identical in both DOPC and DOPS, is not directly involved in the interaction with silica, at least when single molecules are considered. DOPC is an electroneutral molecule, albeit in a zwitterionic state. DOPS molecule, which exhibits a carboxylate group at pH 7, has a negative net charge. This would impart a bias in the molecular simulation when the interaction of DOPC and DOPS is compared with a negatively charged NFS site. Therefore, DOPS structure was simulated by adding a Na+ ion close to the carboxylate group. This approach counterbalances the charge and is consistent with the rich ion environment of the experiments. The interacting structures of both DOPC and DOPS with the NFS sites are shown in Fig. 4 (DOPC-NFS and DOPS-NFS). The relative interaction energies, ΔE = E(PLs-NFS)– (E(PLs)+ E(NFS)) showed that the formation of the NFS-DOPC adduct is a more favorable process than NFS-DOPS, with ΔE of – 32 and – 19 kJ mol−1, respectively. As expected from previous experiments [61], one important component of the ΔE comes from the multiple (three) weak CH…O bonds that are established between the negative end of the NFS and one positive methyl of the group of DOPC. Conversely, a stronger but a single hydrogen bond is formed between DOPS amine and the charged oxygen of NFS. Furthermore, if the role of dispersion (London) interactions is considered, our model indicates that the two CH3 groups of DOPC are hosted within the cradle made by the siloxane bonds of the NFS, when the most energetically favorable configuration is reached (see van del Waals representations in Fig. 4). DOPS can only contribute with a single CH2 group. Therefore, also the London component of the ΔE is expected to be higher for DOPC than DOPS. Both phospholipids are engaged in one hydrogen bond interaction between the Si-OH group and the negative oxygen of the group and, therefore, are almost equally stabilized in that respect. Another factor of distinction could be the role of the explicit water solvation of both silica and the phospholipids. Assuming the same pattern of solvation for the moiety, the difference is entirely due to the solvation pattern and energetic of the vs the moieties. Calculations with the same methodology adopted here for and (as simplified models for the ammonium groups of DOPC and DOPS, respectively) showed a free energy of solvation favorable for the latter moiety by about 77 kJ mol−1. This indicates that de-solvation of the amino moieties is more favorable for DOPC than DOPS. Ultimately, the electrostatic, the dispersion, and the de-solvation contributions of the interactions between PLs and NFS indicate that a more favorable energy of interaction for DOPC than DOPS is likely to be observed in neutral saline environments. This finding is in agreement with the experimental evidence of almost no contact between DOPS and silica.

4. Conclusions

The differentiation in bioactivity of inorganic particles, which is modulated by the variable chemical topography of particles, is a key topic in particle toxicology and material biocompatibility in general. This work investigated the interaction of silica particles, with variable amounts of membranolytic surface silanols (NFS) and model membranes with different molecular complexity and net charge. We determined the presence of selective epitopes on the phospholipid membrane that are available for the interaction with NFS on silica. We demonstrated that silica selectively interacts with and irreversibly adsorbs phospholipid structures when they exhibit a zwitterionic phosphocholine but not when a negatively charged phosphoserine is exposed. A linear correlation between the amount of adsorbed DOPC and the relative amount of NFS on the various silica particles was observed. Consistent with spectroscopic results, this finding defines NFS as the specific surface site responsible for the interaction with membrane PLs. Our data support the specific and selective interaction that requires concurrently the presence of NFS on silica surface and the presence of a definite molecular conformation and charge distribution of the PL polar head. Quaternary amine and phosphate groups, that are exposed by zwitterionic PC or SM, offer the molecular conformation that maximizes the interaction energy with NFS. This observation suggests that the membranolytic interaction with RBC might occur on SM-enriched lipid rafts, where an excess of zwitterionic residues is exposed and a deficiency in negative glycoproteins confers a less polarized interfacial environment in that portion of the membrane. This work was limited to liposomes made of pure DOPC or DOPS, and calculations were limited to small clusters. A higher level of membrane complexity and computational details will be implemented to further support the current findings. Taken together, data presented in this study shed light on the interaction between silica and membranes for a new paradigm to design safer oxide biomaterials and define potential avenues for treatment of silica-induced inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the European Association of Industrial Silica Producers (Brussels, Belgium) under the research contract “Surface Silanols as Key Descriptor of the Silica Hazard”, the National Institutes of Health (US) grants P20GM103546, P30GM103338, National Science Foundation (US) grant CHE-1531520, the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust. We thank Prof. Bice Fubini and Prof. Dominique Lison for constructive discussion, and Lorenzo Tinacci for running the DFT calculations.

Abbreviations:

- AM

Alveolar Macrophages

- AOP

Adverse Outcome Pathway

- Di-4-ANEPPDHQ

Aminonaphthylethenyl–pyridinium dye

- DFT

Density functional theory

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DOPC

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOPS

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine sodium salt

- GPA

Glycophorin A

- NFS

Nearly Free Silanol

- NLRP3

Nod-like receptor protein 3

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PL

Phospholipid

- RBC

Red blood cell

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- SM

sphingomyelin

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cristina Pavan: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Matthew J. Sydor: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Chiara Bellomo: Investigation. Riccardo Leinardi: Investigation. Stefania Cananà: Investigation. Rebekah L. Kendall: Investigation. Erica Rebba: Investigation. Marta Corno: Investigation, Methodology. Piero Ugliengo: Investigation, Methodology. Lorenzo Mino: Investigation, Methodology. Andrij Holian: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Francesco Turci: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112625.

References

- [1].Addadi L, Rubin N, Scheffer L, Ziblat R, Two and three-dimensional pattern recognition of organized surfaces by specific antibodies, Acc. Chem. Res 41 (2) (2008) 254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bachmann MF, Jennings GT, Vaccine delivery: a matter of size, geometry, kinetics and molecular patterns, Nat. Rev. Immunol 10 (11) (2010) 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nel AE, Mädler L, Velegol D, Xia T, Hoek EM, Somasundaran P, Klaessig F, Castranova V, Thompson M, Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano-bio interface, Nat. Mater 8 (7) (2009) 543–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fubini B, Surface reactivity in the pathogenic response to particulates, Environ. Health Perspect 105 (1997) 1013–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bertoli F, Garry D, Monopoli MP, Salvati A, Dawson KA, The intracellular destiny of the protein corona: a study on its cellular internalization and evolution, ACS Nano 10 (11) (2016) 10471–10479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Iler RK, The Chemistry of Silica: Solubility, Polymerization. Colloid and Surface Properties, and Biochemistry, Wiley, New York, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mishra AK, Belgamwar R, Jana R, Datta A, Polshettiwar V, Defects in nanosilica catalytically convert CO2 to methane without any metal and ligand, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117 (2020) 6383–6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cullinan P, Munoz X, Suojalehto H, Agius R, Jindal S, Sigsgaard T, Blomberg A, Charpin D, Annesi-Maesano I, Gulati M, Kim Y, Frank AL, Akgun M, Fishwick D, de la Hoz RE, Moitra S, Occupational lung diseases: from old and novel exposures to effective preventive strategies, Lancet Respir. Med 5 (5) (2017) 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hoy RF, Chambers DC, Silica-related diseases in the modern world, Allergy 00 (2020)1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pavan C, Fubini B, Unveiling the variability of “quartz hazard” in light of recent toxicological findings, Chem. Res. Toxicol 30 (1) (2017) 469–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Murugadoss S, Lison D, Godderis L, Van Den Brule S, Mast J, Brassinne F, Sebaihi N, Hoet PH, Toxicology of silica nanoparticles: an update, Arch. Toxicol 91 (9) (2017) 2967–3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].IARC, IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, World Health Organisation, Lyon: (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sun B, Wang X, Liao YP, Ji Z, Chang CH, Pokhrel S, Ku J, Liu X, Wang M, Dunphy DR, Li R, Meng H, Madler L, Brinker CJ, Nel AE, Xia T, Repetitive dosing of fumed silica leads to profibrogenic effects through unique structure-activity relationships and biopersistence in the lung, ACS Nano 10 (8) (2016) 8054–8066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Croissant JG, Butler KS, Zink JI, Brinker CJ, Synthetic amorphous silica nanoparticles: toxicity, biomedical and environmental implications, Nat. Rev. Mater 5 (12) (2020) 886–909. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rubio L, Pyrgiotakis G, Beltran-Huarac J, Zhang Y, Gaurav J, Deloid G, Spyrogianni A, Sarosiek KA, Bello D, Demokritou P, Safer-by-design flame-sprayed silicon dioxide nanoparticles: the role of silanol content on ROS generation, surface activity and cytotoxicity, Part. Fibre Toxicol 16 (1) (2019) 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nagelschmidt G, Gordon RL, Griffin OG, Surface of finely-ground silica, Nature 169 (1952) 539–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schrader AM, Monroe JI, Sheil R, Dobbs HA, Keller TJ, Li Y, Jain S, Shell MS, Israelachvili JN, Han S, Surface chemical heterogeneity modulates silica surface hydration, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115 (12) (2018) 2890–2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Adsorption on silica surfaces, Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rimola A, Costa D, Sodupe M, Lambert JF, Ugliengo P, Silica surface features and their role in the adsorption of biomolecules: computational modeling and experiments, Chem. Rev 113 (6) (2013) 4216–4313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Burneau A, Gallas J-P, in: Legrand AP (Ed.), The Surface Properties of Silicas, 145–312, Wiley, Chichester, U.K, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pavan C, Delle Piane M, Gullo M, Filippi F, Fubini B, Hoet P, Horwell CJ, Huaux F, Lison D, Lo Giudice C, Martra G, Montfort E, Schins R, Sulpizi M, Wegner K, Wyart-Remy M, Ziemann C, Turci F, The puzzling issue of silica toxicity: are silanols bridging the gaps between surface states and pathogenicity? Part. Fibre Toxicol 16 (1) (2019) 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pavan C, Santalucia R, Leinardi R, Fabbiani M, Yakoub Y, Uwambayinema F, Ugliengo P, Tomatis M, Martra G, Turci F, Lison D, Fubini B, Nearly free surface silanols are the critical molecular moieties that initiate the toxicity of silica particles, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117 (45) (2020) 27836–27846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang H, Dunphy DR, Jiang X, Meng H, Sun B, Tarn D, Xue M, Wang X, Lin S, Ji Z, Li R, Garcia FL, Yang J, Kirk ML, Xia T, Zink JI, Nel A, Brinker CJ, Processing pathway dependence of amorphous silica nanoparticle toxicity: colloidal vs pyrolytic, J. Am. Chem. Soc 134 (38) (2012) 15790–15804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brinker CJ, Butler KS, Garofalini SH, Are nearly free silanols a unifying structural determinant of silica particle toxicity? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117 (48) (2020) 30006–30008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization, Nat. Immunol 9 (8) (2008) 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J, Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica, Science 320 (5876) (2008) 674–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cassel SL, Eisenbarth SC, Iyer SS, Sadler JJ, Colegio OR, Tephly LA, Carter AB, Rothman PB, Flavell RA, Sutterwala FS, The Nalp3 inflammasome is essential for the development of silicosis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105 (26) (2008) 9035–9040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pavan C, Rabolli V, Tomatis M, Fubini B, Lison D, Why does the hemolytic activity of silica predict its pro-inflammatory activity? Part. Fibre Toxicol 11 (2014) 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Biswas R, Bunderson-Schelvan M, Holian A, Potential role of the inflammasome-derived inflammatory cytokines in pulmonary fibrosis, Pulm. Med 2011 (2011), 105707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jessop F, Hamilton RF, Rhoderick JF, Fletcher P, Holian A, Phagolysosome acidification is required for silica and engineered nanoparticle-induced lysosome membrane permeabilization and resultant NLRP3 inflammasome activity, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 318 (2017) 58–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Leinardi R, Pavan C, Yedavally H, Tomatis M, Salvati A, Turci F, Cytotoxicity of fractured quartz on THP-1 human macrophages: role of the membranolytic activity of quartz and phagolysosome destabilization, Arch. Toxicol (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pastero L, Turci F, Leinardi R, Pavan C, Monopoli M, Synthesis of α-quartz with controlled properties for the investigation of the molecular determinants in silica toxicology, Cryst. Growth Des 16 (4) (2016) 2394–2403. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Turci F, Pavan C, Leinardi R, Tomatis M, Pastero L, Garry D, Anguissola S, Lison D, Fubini B, Revisiting the paradigm of silica pathogenicity with synthetic quartz crystals: the role of crystallinity and surface disorder, Part. Fibre Toxicol 13(1) (2016) 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wallace WE, Vallyathan V, Keane MJ, Robinson V, Invitro biologic toxicity of native and surface-modified silica and kaolin, J. Toxicol. Env. Health 16 (3–4) (1985) 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Steele HBB, Sydor MJ, Anderson DS, Holian A, Ross JBA, Using time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy of di-4-ANEPPDHQ and F2N12S to analyze lipid packing dynamics in model systems, J. Fluoresc 29 (2) (2019) 347–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sydor MJ, Anderson DS, Steele HBB, Ross JBA, Holian A, Effects of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nano-materials on lipid order in model membranes, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr 1862 (9) (2020), 183313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sydor MJ, Anderson DS, Steele HBB, Ross JBA, Holian A, Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy and time-resolved anisotropy of nanomaterial-induced changes to red blood cell membranes, Methods Appl. Fluoresc 9 (3) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Owen DM, Rentero C, Magenau A, Abu-Siniyeh A, Gaus K, Quantitative imaging of membrane lipid order in cells and organisms, Nat. Protoc 7 (1) (2011) 24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Minazzo AS, Darlington RC, Ross JB, Loop dynamics of the extracellular domain of human tissue factor and activation of factor VIIa, Biophys. J 96 (2) (2009) 681–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kinosita K Jr., Ikegami A, Kawato S, On the wobbling-in-cone analysis of fluorescence anisotropy decay, Biophys. J 37 (2) (1982) 461–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bannwarth C, Ehlert S, Grimme S, GFN2-xTB—An accurate and broadly parametrized self-consistent tight-binding quantum chemical method with multipole electrostatics and density-dependent dispersion contributions, J. Chem. Theory Comput 15 (3) (2019) 1652–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bannwarth C, Caldeweyher E, Ehlert S, Hansen A, Pracht P, Seibert J, Spicher S, Grimme S, Extended tight-binding quantum chemistry methods, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci 11 (2) (2021), e1493. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Brandenburg JG, Bannwarth C, Hansen A, Grimme S, B97-3c: a revised low-cost variant of the B97-D density functional method, J. Chem. Phys 148 (6) (2018), 064104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Neese F, Wennmohs F, Becker U, Riplinger C, The ORCA quantum chemistry program package, J. Chem. Phys 152 (22) (2020), 224108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Barone V, Cossi M, Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model, J. Chem. Phys. A 102 (11) (1998) 1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhuravlev LT, Concentration of hydroxyl-groups on the surface of amorphous silicas, Langmuir 3 (3) (1987) 316–318. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sulpizi M, Gaigeot M, Sprik M, The silica-water interface: how the silanols determine the surface acidity and modulate the water properties, J. Chem. Theory Comput 8 (3) (2012) 1037–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Clouter A, Brown D, Hohr D, Borm P, Donaldson K, Inflammatory effects of respirable quartz collected in workplaces versus standard DQ12 quartz: particle surface correlates, Toxicol. Sci 63 (1) (2001) 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cho WS, Duffin R, Bradley M, Megson IL, MacNee W, Lee JK, Jeong J, Donaldson K, Predictive value of in vitro assays depends on the mechanism of toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles, Part. Fibre Toxicol 10 (2013) 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mohandas N, Gallagher PG, Red cell membrane: past, present, and future, Blood 112 (10) (2008) 3939–3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bondar OV, Saifullina DV, Shakhmaeva II, Mavlyutova II, Abdullin TI, Monitoring of the zeta potential of human cells upon reduction in their viability and interaction with polymers, Acta Nat. 4 (1) (2012) 78–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Thomassen LC, Rabolli V, Masschaele K, Alberto G, Tomatis M, Ghiazza M, Turci F, Breynaert E, Martra G, Kirschhock CE, Martens JA, Lison D, Fubini B, Model system to study the influence of aggregation on the hemolytic potential of silica nanoparticles, Chem. Res. Toxicol 24 (11) (2011) 1869–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dumitra AC, Poncin MA, Conrard L, Dufrene YF, Tyteca D, Alsteens D, Nanoscale membrane architecture of healthy and pathological red blood cells, Nanoscale Horiz. 3 (3) (2018) 293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Simons K, Ikonen E, Functional rafts in cell membranes, Nature 387 (6633) (1997) 569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Murphy SC, Samuel BU, Harrison T, Speicher KD, Speicher DW, Reid ME, Prohaska R, Low PS, Tanner MJ, Mohandas N, Haidar K, Erythrocyte detergent-resistant membrane proteins: their characterization and selective uptake during malarial infection, Blood 103 (5) (2004) 1920–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Simons K, Gruenberg J, Jamming the endosomal system: lipid rafts and lysosomal storage diseases, Trends Cell Biol. 10 (11) (2000) 459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW, Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol 9 (2) (2008) 112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Yeagle PL, The membranes of cells, Academic Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Liu Y, Liu J, Leakage and rupture of lipid membranes by charged polymers and nanoparticles, Langmuir 36 (3) (2020) 810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wang X, Li X, Wang H, Zhang X, Zhang L, Wang F, Liu J, Charge and coordination directed liposome fusion onto SiO2 and TiO2 nanoparticles, Langmuir 35(5) (2019) 1672–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Depasse J, Leonis J, Inhibition of the hemolytic activity of quartz by a chemically modified lysozyme, Environ. Res 12 (3) (1976) 371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Nazemidashtarjandi S, Vahedi A, Farnoud AM, Lipid chemical structure modulates the disruptive effects of nanomaterials on membrane models, Langmuir 36 (18) (2020) 4923–4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Slowing II, Wu CW, Vivero-Escoto JL, Lin VS, Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for reducing hemolytic activity towards mammalian red blood cells, Small 5 (1) (2009) 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Murray DK, Differentiating and characterizing geminal silanols in silicas by (29)Si NMR spectroscopy, J. Colloid Interface Sci 352 (1) (2010) 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chunbo Y, Daqing Z, Aizhuo L, Jiazuan N, NMR A, study of the interaction of silica with dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine liposomes, J. Colloid Interface Sci 172 (2) (1995) 536–538. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.