Chemical meningitis may not cause any of the classical symptoms and diagnosis is difficult. After resection of a craniopharyngioma, routine follow-up scanning is generally recommended, but the optimum interval between scans remains uncertain.

CASE HISTORY

A roofing worker had been investigated for headaches and signs of hypopituitarism at age 20 and found to have a craniopharyngioma. This was decompressed and removed subtotally by a transfrontal approach. Biopsy showed a squamous lined cystic lesion with associated local inflammation and granulation tissue formation, with giant cell response and palisading. He made a good recovery, with normal visual fields on perimetry, and returned to work. He remained under regular endocrine review and took replacement therapy of thyroxine, hydrocortisone, desmopressin and testosterone, but not growth hormone. After marriage and subsequent investigation for infertility he took chorionic gonadotropin for several years, without success. 5 years postoperatively, CT showed a small cystic pituitary lesion, with some calcification, extending upwards to the base of the third ventricle but not distorting it. Visual fields remained normal and he had no symptoms and remained under regular endocrine review.

At age 34 the patient developed a sudden generalized headache, intermittent and relieved by analgesics. He was admitted to a peripheral hospital after five days, where the headache persisted. There was no vomiting, photophobia, neck stiffness, rash or lymphadenopathy, but because of persistent mild pyrexia he was judged to have an infection and was given intravenous antibiotics and supplementary hydrocortisone. Blood cultures were sterile, and white cell count remained normal (9.36109/L). Lumbar puncture was not performed because of the absence of localizing central nervous signs and his general wellbeing (apart from the headache). CT was not available locally. On the fifth hospital day he suddenly lost consciousness, with subsequent respiratory arrest. After intubation and ventilation he was transferred to the regional intensive care unit where CT revealed hydrocephalus and recurrence of the craniopharyngioma cyst. White cell count taken at the time of the acute deterioration had risen to 256109/L. A ventricular drain was inserted but he remained deeply unconscious with dilated pupils and was pronounced dead after two days.

At necropsy he was found to have moderate hydrocephalus with dilatation of the lateral ventricles but not of the third ventricle; the fourth ventricle was obliterated, with necrosis of the medulla, cerebellar tonsils and cervical spinal cord. External meningeal exudates were absent except at the cerebellum and cervical cord, where there was a subacute inflammatory reaction with eosinophils, macrophages and lymphocytes predominating, suggesting a longer duration than the cerebellar necrosis. The pituitary lesion was 2.5 cm in diameter, cystic and necrotic, without marked suprasellar extension (Figure 1). Evidence of bacterial infection was not found. Probably there had been an active chemical meningitis caused by irritation and leakage from the craniopharyngioma cyst of some duration. This had caused meningeal adhesions and longstanding hydrocephalus with ventricular dilatation, but the terminal acute phase with sudden exacerbation of hydrocephalus and brain stem herniation was due to further rupture of the craniopharyngioma cyst.

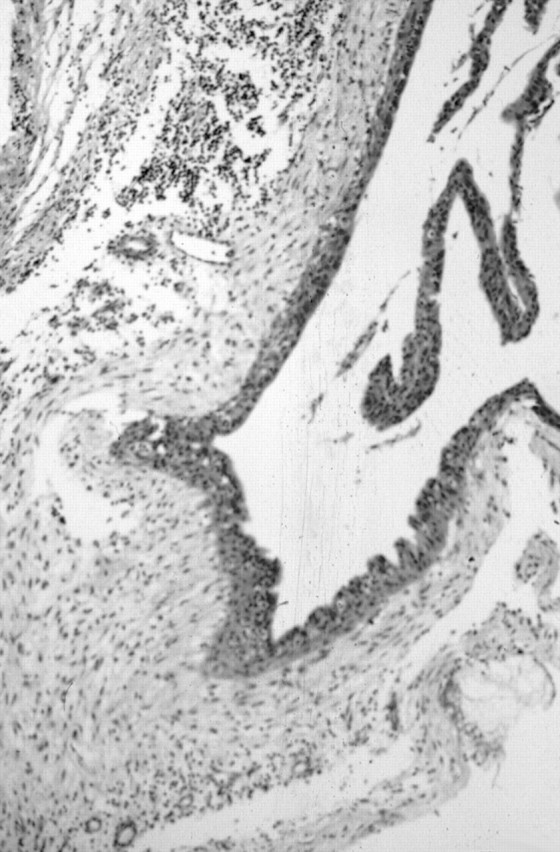

Figure 1.

Craniopharyngioma cyst lined by flattened squamous epithelium. The distinct fibrous capsule shows focal chronic inflammation with keratinous deposits and giant cell reaction. The cyst contents were keratinous with cholesterol deposits and associated inflammatory response. Haematoxylin and eosin ×50

COMMENT

The initial moderate headache and mild pyrexia in the present case was not alarming, in the absence of meningism. CT at that stage might have allowed an attempt at further decompression, but the acute deterioration was not preceded by warning signs. Chemical meningitis has been reported from intracranial rupture of several types of cystic structures, including intracranial dermoid cysts,1 cholesteatoma following radical mastoidectomy, remnant after geniculate ganglion surgery, and epidermoid cysts in the cerebellar pontine angle, as well as from a craniopharyngioma or cyst of Rathke's pouch.2,3 Accumulation of the oily irritant material within a cyst lined by squamous epithelium is an irregular phenomenon: some remain quiescent before and after decompression. Radiotherapy may or may not affect cyst recurrence. Long-term review of these patients is often in the hands of endocrinologists, who need to arrange intermittent scans to identify cyst recurrence.4

References

- 1.Stendal R, Pietila TA, Lehmann K, Kurth R, Suess O, Brock M. Ruptured intracranial dermoid cysts. Surg Neurol 2002;57: 391-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulkarni V, Daniel RT, Pranatartiharan R. Spontaneous intraventricular rupture of craniopharyngioma cyst. Surg Neurol 2000;54: 249-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satoh H, Uozumi T, Arita K, et al. Spontaneous rupture of craniopharyngioma cysts. A report of five cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 1993;40: 414-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton RN, Wass JAH. Pituitary tumours: recommendations for service provision and guidelines for management of patients. Summary of a consensus statement of a working party. J R Coll Phys Lond 1997;31: 628-36 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]