Abstract

Objective:

Simulation may be a valuable tool in training laryngology office procedures on unsedated patients. However, no studies have examined whether existing awake procedure simulators improve trainee performance in laryngology. Our objective was to evaluate the transfer validity of a previously published 3D-printed laryngeal simulator in improving percutaneous injection laryngoplasty (PIL) competency compared to conventional educational materials with a single-blinded randomized controlled trial.

Methods:

Otolaryngology residents with fewer than 10 PIL procedures in their case logs were recruited. A pre-training survey was administered to participants to evaluate baseline procedure-specific knowledge and confidence. Participants underwent block randomization by postgraduate year to receive conventional educational materials either with or without additional training with a 3D-printed laryngeal simulator. Participants performed PIL on an anatomically distinct laryngeal model via trans-thyrohyoid and trans-cricothyroid approaches. Endoscopic and external performance recordings were de-identified and evaluated by two blinded laryngologists using an OSATS scale and PIL-specific checklist.

Results:

Twenty residents completed testing. Baseline characteristics demonstrate no significant differences in confidence level or PIL experience between groups. Senior residents receiving simulator training had significantly better respect for tissue during the trans-thyrohyoid approach compared to control (p < 0.0005). There were no significant differences in performance for junior residents.

Conclusions:

In this first transfer validity study of a simulator for office awake procedure in laryngology, we found that a previously described low-cost, high-fidelity 3D-printed PIL simulator improved performance of PIL amongst senior otolaryngology residents, suggesting this accessible model may be a valuable educational adjunct for advanced trainees to practice PIL.

Keywords: surgical simulation, surgical education, validation, 3D printing, injection laryngoplasty, laryngology

Lay Summary:

Simulation platforms are an important tool for skill building in surgical specialties, such as otolaryngology. A previously described 3D-printed percutaneous injection laryngoplasty (PIL) simulator has been proposed as a low-cost, high-fidelity educational tool. We conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine if training with this simulator can improve procedure-specific skills amongst otolaryngology residents compared to traditional reading materials. We found that simulator training may improve PIL technique amongst more experienced residents compared to traditional training.

Introduction:

Recent trends in surgical education, such as the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 80-hour work limit1 and cross-institutional implementation of competency-based benchmarks2, have given rise to unique educational challenges and placed the onus onto surgeon educators to identify novel teaching modalities to optimize surgical training. In this context, surgical simulation has gained popularity across surgical specialties, including otolaryngology – head and neck surgery. This trend was accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the disruption of elective surgical schedules and the need for contingency plans in surgical curricula for residents and medical students3. Although simulation has its own limitations (e.g., simplifications to human anatomy and dearth of validation studies), it has several inherent advantages over the classic surgeon-assistant teaching framework: practice in low-stakes environments, repetition of procedures until success, immediate feedback and objective performance assessment, and simulation of low-volume procedures4.

These training advantages of simulators are particularly pertinent in laryngology with the continuing trend of bringing surgical procedures back in the office5 – a trend driven by cost-effectiveness considerations, increased training and experience among laryngologists and improved technology, such as distal chip laryngoscopes. Office procedures on awake patients rather than under anesthesia in the operating room are challenging to teach. Surgical residents identified several factors negatively impacting learning while training on awake patients, including hesitance towards asking questions and issues with whispering and nonverbal communication6. Among awake procedures in laryngology, percutaneous injection laryngoplasty (PIL) training is particularly challenging to teach, as it relies on subtle visual and tactile cues that are difficult to learn by observation alone, and patient discomfort and potentially untoward immediate effect of the intervention may affect trainee’s comfort and confidence during procedure performance.

Simulators may be a helpful adjunct in PIL training, as they provide a controlled, low-stakes environment with which to practice and ask questions. Several PIL simulators have been created with varying levels of anatomic fidelity and accessibility, including models made from low-cost materials (e.g. toilet paper rolls) and animal cadaveric models7–11. However, there have been no validation studies for existing PIL simulators demonstrating their utility in improving procedural skills, beyond measures of trainees’ subjective comfort and confidence. Without such validation study, the performance of the simulator is impossible to gauge and their inclusion in surgical curricula is of questionable value. Lee, et al12 described a low-cost, open-source 3D-printed model that utilizes a hard plastic framework and soft silicone insert to simulate the laryngeal cartilage and endolaryngeal soft tissue respectively. The simulator was well rated by expert laryngologists using an adapted version of the Michigan Standard Simulation Experience Scale (MiSSES), a standardized scale evaluating the subjective experience with surgical simulators providing information on face and content validity. To demonstrate educational value among trainees, the effectiveness of the simulator in producing a learning effect and improving performance of PIL among residents, i.e. its transfer validity, ought to be investigated. Therefore, our primary objective was to evaluate the transfer validity of this 3D-printed laryngeal simulator. We hypothesized that practicing with a simulator would improve PIL performance compared to conventional training.

Methods:

Participant Recruitment and Training

This study was deemed exempt from approval by an institutional review board. Otolaryngology – head and neck surgery residents across multiple institutions in New York, NY with fewer than 10 PIL procedures in their case logs were recruited from March 2020 – October 2022. Those who met inclusion criteria were asked to complete pre- and post-testing surveys to assess their baseline level of experience and confidence relating to PIL. Participants underwent block randomization by postgraduate year and were allocated to either the conventional training group or simulator training group. The conventional training group received educational written resources and free online videos pertaining to the PIL procedure. The simulator training group received the same resources as the conventional group as well as a 3D-printed laryngeal simulator with which to practice PIL on their own for a minimum of one hour (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Flow diagram of study design and participant group allocation.

Creating 3D-Printed PIL Simulator

The design for the 3D-printed simulator was published by Lee, et al.12, and the protocol for producing the model was taken from the accompanying WikiFactory page (https://wikifactory.com/@3dlaryngology/3d-larynx-surgery-trainer). The hard plastic framework and injection molds were printed using an Ender-3 printer (Creality, Shenzhen, China) and a polylactic acid filament (HATCHBOX, Pomona, California, USA). Endolaryngeal structures were created using EcoFlex 00–20 silicone (SmoothOn, Macungie, Pennsylvania, USA).

Performance Evaluation

Proficiency was evaluated by participant performance of PIL on a 3D-printed larynx that was anatomically distinct from the training model. Whereas the training simulator was modeled after a human female larynx, the testing simulator was modeled after male anatomy. The testing larynx was also inset into a head-and-neck manikin with attached borescope to allow for endoscopic visualization. Participants performed two attempts each of the trans-thyrohyoid and trans-cricothyroid approaches, each time narrating out loud their procedural steps. External and endoscopic recordings were collected and de-identified through video editing software by altering vocal pitch and cropping out identifying participant characteristics (Figure 2). Each participant’s de-identified performance was evaluated by two blinded laryngologists (CC and AR). Evaluation metrics were adapted from the objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) scale13, which included items such as “respect for tissue” and “instrument handling” rated on a five-point Likert scale with anchoring statements. PIL approach-specific checklists were also used to rate performance, and ranged from 1 (unable to perform) to 5 (performs expertly) (Table 1).

Figure 2:

Still Image of a De-Identified Performance Video. Identifying physical characteristics have been cropped out of the video, and voice pitch has been changed so participant narration is not identifiable.

Table 1:

Checklists unique to the trans-thyrohyoid and trans-cricothyroid approaches to PIL used to evaluate participant performance. Participants were evaluated by each of these criteria on a Likert scale, where 1 = unable to perform and 5 = performs expertly.

| Trans-Thyrohyoid Approach | Trans-Cricothyroid Approach |

|---|---|

Palpate thyroid notch

|

Palpate cricothyroid membrane

|

Insert needle immediately above thyroid notch and acutely downward until enters airway in the area of the petiole

|

Insert needle through cricothyroid membrane superolateral in a submucosal fashion

|

Inject at appropriate location (just anterior to the vocal process, lateral to the arcuate line)

|

Inject at appropriate location (just anterior to the vocal process, lateral to the arcuate line)

|

Statistical Analysis

Each attempt of the trans-thyrohyoid and trans-cricothyroid approaches were counted independently during analysis. Resident seniority was stratified between junior residents (postgraduate years one and two) and senior residents (postgraduate years three, four, and five). Descriptive statistics were calculated for each evaluation criterion. Statistical significance was calculated using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Interrater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa. Calculations were performed using R statistical software package (version 2022.07.2).

Results:

Twenty participants completed PIL performance testing. Baseline characteristics revealed a median postgraduate year of two (interquartile range (IQR) 2), zero prior performed PILs (IQR 1), and two previously observed PILs (IQR 2). There were no significant differences in experience between the simulator training and conventional training groups (Table 2). Baseline average confidence, as assessed by self-reporting on a Likert scale, was neutral for pertinent anatomy, neutral to unconfident for knowledge of equipment and procedure set-up, unconfident for ability to perform PIL, and unconfident to very unconfident to teach PIL to other trainees. There were no significant differences in self-reported baseline confidence between the simulator training and conventional training groups (Table 2).

Table 2:

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Allocated Group. (For confidence measures, 1 = very unconfident, 2 = unconfident, 3 = neutral, 4 = confident, 5 = very confident).

| Simulator Training, median (IQR) | Conventional Training, median (IQR) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postgraduate Year | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 0.41 |

| Number of PIL procedures performed | 0.5 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.47 |

| Number of PIL procedures observed | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2) | 0.79 |

| Confidence Measures | |||

| Knowledge of pertinent anatomy | 3 (0.5) | 3 (1) | 0.73 |

| Knowledge of pertinent equipment and procedure set-up | 3 (0.5) | 2 (1) | 0.11 |

| Ability to perform PIL | 2 (0) | 2 (1) | 0.44 |

| Ability to teach PIL to another trainee | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1) | 0.32 |

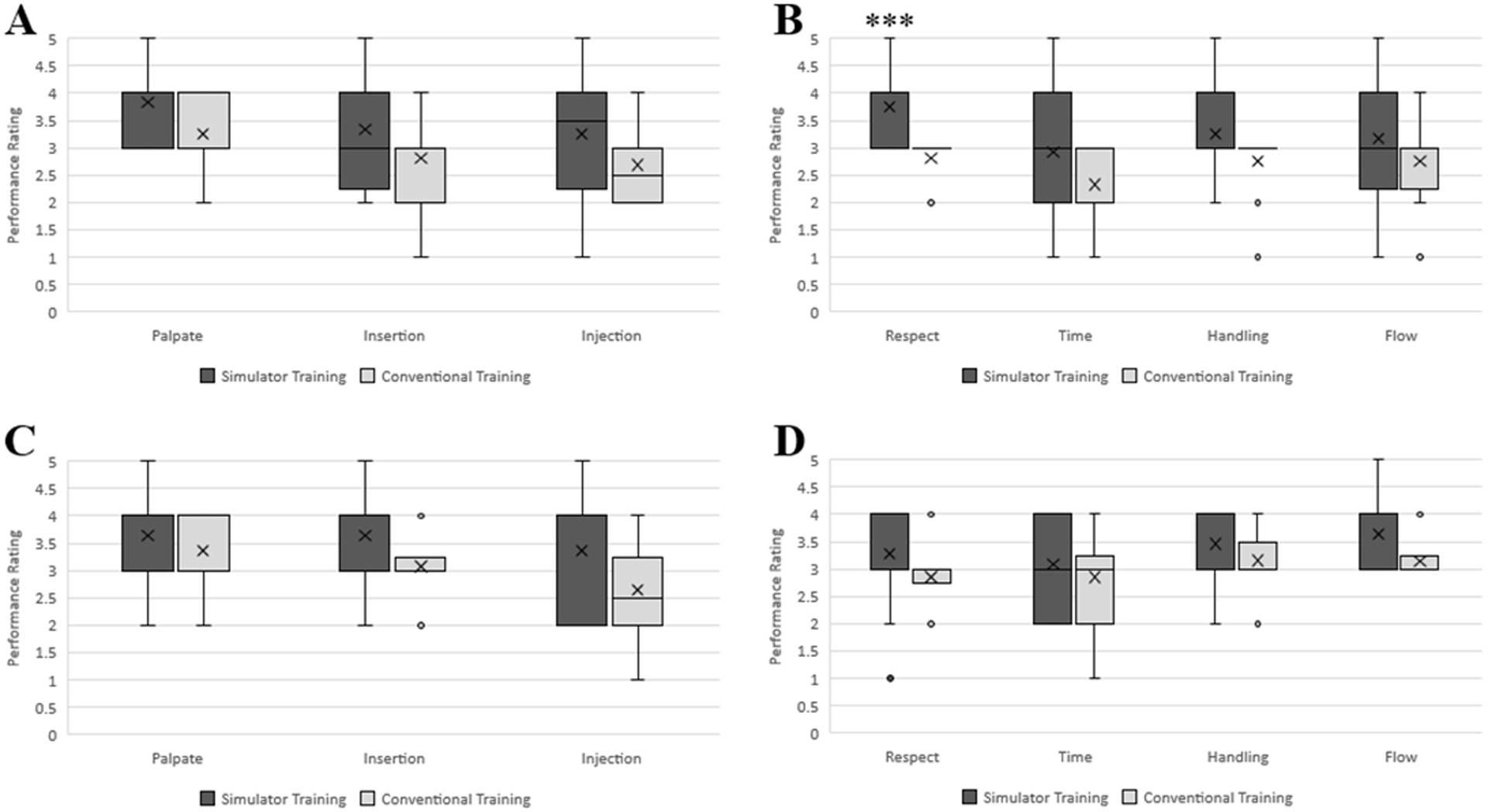

Performance was evaluated for 19 residents. One participant’s performance video became corrupted and could not be assessed. Eleven participants (55%) were in the simulator training group and nine participants (45%) were in the conventional training group. In comparison between the overall simulator training group and the conventional group, there were no significant differences in global or procedure-specific technique in either PIL approach (Figure 3). However, when stratified by resident seniority, senior residents who trained with the simulator had significantly better respect for tissue performing the trans-thyrohyoid approach compared to the conventional group (Figure 4). There were no differences in PIL performance between the training groups amongst junior residents (Figure 5).

Figure 3:

Evaluation of PIL technique of all participants using the trans-thyrohyoid and trans-cricothyroid approaches. Assessment was made using a Likert scale (1 = unable to perform, 5 = performs expertly). (A) Evaluation of skills specific to the trans-thyrohyoid approach. (B) OSATS-derived evaluation of global surgical skills during trans-thyrohyoid approach. (C) Evaluation of skills specific to the trans-cricothyroid approach. (D) OSATS-derived evaluation of global surgical skills during trans-cricothyroid approach. (Palpate = palpate appropriate landmarks; Insertion = appropriate percutaneous insertion of needle; Placement = appropriate placement of needle into vocal fold; Respect = respect for tissues; Time = economy of time/motion; Handling = instrument handling; Flow = flow of operation)

Figure 4:

Evaluation of PIL technique of senior resident participants using the trans-thyrohyoid and trans-cricothyroid approaches. Assessment was made using a Likert scale (1 = unable to perform, 5 = performs expertly). (A) Evaluation of skills specific to the trans-thyrohyoid approach. (B) OSATS-derived evaluation of global surgical skills during trans-thyrohyoid approach. (C) Evaluation of skills specific to the trans-cricothyroid approach. (D) OSATS-derived evaluation of global surgical skills during trans-cricothyroid approach. (Palpate = palpate appropriate landmarks; Insertion = appropriate percutaneous insertion of needle; Placement = appropriate placement of needle into vocal fold; Respect = respect for tissues; Time = economy of time/motion; Handling = instrument handling; Flow = flow of operation). *** indicates p < 0.0005

Figure 5:

Evaluation of PIL technique of junior resident participants using the trans-thyrohyoid and trans-cricothyroid approaches. Assessment was made using a Likert scale (1 = unable to perform, 5 = performs expertly). (A) Evaluation of skills specific to the trans-thyrohyoid approach. (B) OSATS-derived evaluation of global surgical skills during trans-thyrohyoid approach. (C) Evaluation of skills specific to the trans-cricothyroid approach. (D) OSATS-derived evaluation of global surgical skills during trans-cricothyroid approach. (Palpate = palpate appropriate landmarks; Insertion = appropriate percutaneous insertion of needle; Placement = appropriate placement of needle into vocal fold; Respect = respect for tissues; Time = economy of time/motion; Handling = instrument handling; Flow = flow of operation)

For each evaluation criterion, the Cohen’s kappa value ranged from 0.20 to 0.40, indicating fair agreement between the two laryngologists performing the de-identified video ratings (Table 3).

Table 3:

Interrater Reliability for PIL Performance Evaluation Criteria

| Cohen’s kappa | |

|---|---|

| Trans-thyrohyoid approach | |

| Palpate appropriate landmarks | 0.38 |

| Needle insertion | 0.44 |

| Injection into appropriate location | 0.52 |

| Trans-cricothyroid approach | |

| Palpate appropriate landmarks | 0.29 |

| Needle insertion | 0.37 |

| Injection into appropriate location | 0.33 |

| Global surgical technique | |

| Respect for tissues | 0.36 |

| Time/motion | 0.40 |

| Instrument handling | 0.29 |

| Flow of operation | 0.30 |

Discussion:

Validation of surgical simulator systems are necessary to ensure simulators actually improve the technical skills they are designed for and to help educators decide incorporate specific simulators into surgical curricula. Unfortunately, across surgical subspecialties, there is a dearth of literature exploring simulator validation. A 2017 systematic review of simulators in otolaryngology revealed that amongst the 64 otolaryngologic simulators described in the literature, only 20 studies examined whether a given simulator has transfer validity and improved procedure-specific skills.14 Other types of validation studies of surgical simulators in otolaryngology focused on face validity (degree to which the simulation represents a realistic scenario), content validity (whether the simulation measures the criteria that it is intended to assess), and construct validity (whether the simulation can distinguish between the performance of users of differing expertise)14, which, while important, do not examine the direct effect of these models on procedural skills among trainees. Transfer validity is thus a research focus of crucial importance to determine as the number of simulators are multiplying in otolaryngology, with a lower barrier to access thanks to technological advances such as inexpensive 3D printing technology and ubiquitous virtual and augmented goggles.

We presented here the results of the first transfer validity study of a laryngeal simulator for office awake procedure, looking at the effectiveness of a previously described low-cost, high-fidelity 3D-printed PIL simulator12 in improving trainee performance. We found that the model significantly improved one aspect of surgical technique, i.e. respect for tissues, in the trans-thyrohyoid approach to PIL amongst senior residents when compared to conventional training modalities. However, there was no statistically significant effect of simulator training on proficiency in the trans-cricothyroid approach with senior residents or in either approach with junior residents. This isolated effect on senior residents may be attributable to factors including more advanced skillsets and a more thorough understanding of the challenges in performing PIL compared to junior residents, allowing for more meaningful practice with the simulator during the training phase. Junior residents may lack the hands-on experience and basic knowledge of PIL, such that self-directed at-home training was less effective.

There is only one other validation study for injection laryngoplasty, though focusing on the transoral operative approach. Dedmon, et al. conducted a construct validity study of a porcine laryngeal model comparing surgical performance of microlaryngoscopy for several interventions including injection laryngoplasty in expert laryngologists against novices8. For operative injection laryngoplasty, they found that there was no significant difference between the performance of experts compared to novices, indicating a lack of construct validity15. Proposed explanations included difficulty in differentiating performance in this relatively short procedure with few steps and a possibly accelerated learning curve, making the performance of an expert indistinguishable from a novice8. Of note, this model differs significantly from the one used in our study as it simulates a surgical, rather than in-office, procedure. However, this procedure has analogous steps to PIL, and thus explanations similar to those proposed by Dedmon, et al. may have played a role. In particular, we posit the short duration and limited number of steps of PIL may have limited the evaluators’ ability to accurately discriminate proficiency in participants who trained with a simulator compared to the control group in every category assessed.

There are several limitations to this study which may affect the strength of our findings. First, we used performance on an anatomically distinct 3D-printed larynx model as a proxy for procedural proficiency on an awake patient. This methodology allowed for multiple attempts via multiple approaches for each participant without risk to actual patients. While we hypothesize that performance on this model would correlate with performance on an actual patient, we cannot say with absolute certainty that our results are generalizable to in-office practice with awake patients. However, testing performance on patients would not be feasible due to the number of participants included in this study, as well as the presence of confounders. Another possible limitation is the lack of standardization or supervision of the simulator training for our experimental group. We asked participants to undergo self-directed practice without a formal training program, which may have created variability in the training itself, affecting ultimate performance. A third limitation is the lack of fundamental difference between the countertop simulator and manikin insert except for size, giving an advantage to subjects who trained with the former in the validation study. A fourth limitation is that our study uses a relatively small sample size, affecting the power of our statistical analysis and external validity. Fifth, Dedmon et al.8 did not find a difference on the transoral vocal fold injection module of their simulation experiment, but showed differences with more complicated tasks such as lesion excision. It is possible that a longer and more complicated series of tasks on the simulator may show greater differences in performance between subjects. Lastly, laryngology experts reviewing de-identified videos in our protocol may have reached higher correlation in their ratings if they had reviewed sample videos together along with evaluation scales. Future directions may include evaluating skillsets on patients, creating a standardized method by which to practice with the simulator, increasing participant sample size, and establishing construct validity.

Conclusion:

Simulation of awake procedures in laryngology offers the opportunity for practice and repetition in a controlled, low-stakes environment. With our study of a 3D-printed laryngeal simulator for PIL performance, we present the first transfer validity study of a simulator for an awake laryngology procedure. Our findings suggest the simulator improved proficiency of PIL amongst senior otolaryngology residents only. Future directions include standardized simulation training protocol, construct validity study and skills evaluation in actual clinical scenarios.

Funding and Conflicts of Interest:

Anaïs Rameau was supported by a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging (K76 AG079040) from the National Institute on Aging and by the Bridge2AI award (OT2 OD032720) from the NIH Common Fund. Anaïs Rameau owns equity of Perceptron Health, Inc. The other authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Meeting: Podium Presentation, American Laryngological Association 2023 Annual Meeting, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; May 5–7, 2023

References:

- 1.Ahmed N, Devitt KS, Keshet I, et al. A systematic review of the effects of resident duty hour restrictions in surgery: impact on resident wellness, training, and patient outcomes. Ann Surg. Jun 2014;259(6):1041–53. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonnadara RR, Mui C, McQueen S, et al. Reflections on competency-based education and training for surgical residents. J Surg Educ. Jan-Feb 2014;71(1):151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James J, Irace AL, M AD, Kim AH, Gudis DA, Overdevest JB. Thinking Beyond the Temporal Bone Lab: A Systematic Process for Expanding Surgical Simulation in Otolaryngology Training. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Aug 1 2022:34894221115753. doi: 10.1177/00034894221115753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammoud MM, Nuthalapaty FS, Goepfert AR, et al. To the point: medical education review of the role of simulators in surgical training. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2008;199(4):338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess M, Fleischer S Office-Based Procedures. Textbook of Surgery of Larynx and Trachea. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022:155–173. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith CS, Nolan R, Guyton K, Siegler M, Langerman A, Schindler N. Resident Perspectives on Teaching During Awake Surgical Procedures. J Surg Educ. Nov - Dec 2019;76(6):1492–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salazar J, Gras JR, Sanchez-Guillen L, Sanchez-Del-Campo F, Arroyo A. Phonosurgery Training in Human Larynx Preserved with Thiel’s Embalming Method. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2021;83(6):412–419. doi: 10.1159/000512725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dedmon MM, Paddle PM, Phillips J, Kobayashi L, Franco RA, Song PC. Development and Validation of a High-Fidelity Porcine Laryngeal Surgical Simulator. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Sep 2015;153(3):420–6. doi: 10.1177/0194599815590118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamdan AL, Haddad G, Haydar A, Hamade R. The 3D Printing of the Paralyzed Vocal Fold: Added Value in Injection Laryngoplasty. J Voice. Jul 2018;32(4):499–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabrera-Muffly C, Clary MS, Abaza M. A low-cost transcervical laryngeal injection trainer. Laryngoscope. Apr 2016;126(4):901–5. doi: 10.1002/lary.25561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ainsworth TA, Kobler JB, Loan GJ, Burns JA. Simulation model for transcervical laryngeal injection providing real-time feedback. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Dec 2014;123(12):881–6. doi: 10.1177/0003489414539922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M, Ang C, Andreadis K, Shin J, Rameau A. An Open-Source Three-Dimensionally Printed Laryngeal Model for Injection Laryngoplasty Training. Laryngoscope. Mar 2021;131(3):E890–E895. doi: 10.1002/lary.28952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin JA, Regehr G, Reznick R, et al. Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br J Surg. Feb 1997;84(2):273–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1997.02502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musbahi O, Aydin A, Al Omran Y, Skilbeck CJ, Ahmed K. Current Status of Simulation in Otolaryngology: A Systematic Review. J Surg Educ. Mar-Apr 2017;74(2):203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aucar JA, Groch NR, Troxel SA, Eubanks SW. A review of surgical simulation with attention to validation methodology. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. Apr 2005;15(2):82–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000160289.01159.0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]