Abstract

In this case report, we present the clinical management of a 52-year-old female patient with a recurrent right temporo-parietal glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). The patient presented with symptoms of headache and loss of balance and recurrence on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). To evaluate the fibroblast activation protein inhibitor (FAPi) expression in the recurrent lesion, an exploratory [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi PET/CT scan was performed. The imaging results revealed FAPi expression in the lesion located in the right temporo-parietal region. Based on the findings of FAPi expression, the patient underwent [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 treatment. After completing two cycles of [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 therapy, a follow-up [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi PET/CT scan was conducted. The post-treatment imaging showed a significant reduction in FAPi uptake and regression in the size of the lesion, as well as a decrease in perilesional edema, as observed on the MRI. Furthermore, the patient experienced an improvement in symptoms and performance status. These results suggest that [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi monomer imaging and [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 dimer therapeutics hold promise for patients with recurrent GBM when other standard-line therapeutic options have been exhausted. This case highlights the potential of using FAPi-based theranostics in the management of recurrent GBM, providing a potential avenue for personalized treatment in patients who have limited treatment options available.

Keywords: Glioblastoma multiforme; [68 Ga, Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi PET/CT; [177Lu, Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 therapy

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is typically treated with surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. However, the prognosis for GBM remains poor due to the aggressive nature of the disease and limited treatment options. Recent studies have identified elevated levels of fibroblast activation protein (FAP) expression in various subtypes of glioblastomas [1–3].

Several investigations focusing on human gliomas have observed increased FAP protein expression, particularly in the mesenchymal subtypes of gliomas [1–7]. Additionally, a strong positive correlation has been established between FAP expression and the aggressiveness of gliomas, mainly due to its influence on remodeling the tumor microenvironment. FAP has been found to promote glioma cell invasion through brain tissue by facilitating the degradation of the brain parenchyma, suggesting its involvement in tumor cell invasion. Increased FAP expression has also been detected in both tumor cells and the pro-tumorigenic microenvironment of neuroepithelial cancers [4–7]. In a study by Pandya et al., they utilized the U87MG cell line, which naturally expresses FAP, to evaluate the immuno-PET radiopharmaceutical [89Zr]Zr-Df-Bz-F19 mAb in vitro. Their findings demonstrated that FAP shows promise as a biomarker for gliomas [8].

Case Report

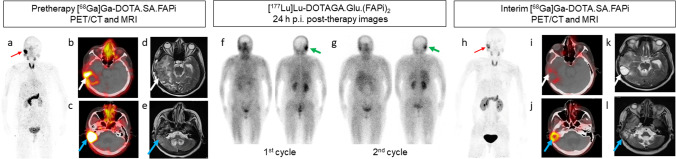

Figure 1 illustrates a case of a 52-year-old female patient who was initially diagnosed with a right temporal space-occupying lesion and underwent craniotomy and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy in December 2017. The histopathological evaluation confirmed the presence of GBM, a high-grade brain tumor (WHO Grade IV). The tumor was characterized as isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) wild type, with a Ki67 index of 10–12%. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis showed positive staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and negative staining for cytokeratin (CK), indicating glial cell origin. The tumor had a wild-type p53 status, IDH1 negativity, and alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX) positivity.

Fig. 1.

Baseline [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi PET/CT of the patient showed focal intense radiotracer uptake (red arrow) in the head region in maximum intensity projection (MIP) images (a), which was localized to the right temporo-parietal region and in the right cerebellar region in the axial PET/CT images (white and blue arrows in b and c, respectively). Axial T2-weighted MRI images of the same lesion were noted (white and blue arrows in d and e, respectively) with significant perilesional edema. Image (f) depicted the post-therapy scan of the 1st cycle, conducted 24 h after administering 7.4 GBq of [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 in the anterior and posterior views. Similarly, image (g) represented the post-therapy scan of the 2nd cycle, performed 24 h after administering 7.4 GBq of [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 in the anterior and posterior views. Both scans revealed the retention of the therapeutic radiotracer (green arrow). Visual analysis of the [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 images revealed that the initial post-treatment scan after the first cycle (f) exhibited higher uptake compared to the post-therapy scan after the second cycle (g). Post-therapy response assessment [.68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi PET/CT revealed a significant reduction in uptake of the tracer in the MIP images (red arrow in h) and a reduction in size and uptake of the right temporo-parietal region and in the right cerebellar region in the axial PET/CT images (white and blue arrows in i and j, respectively). Follow-up T2-weighted MRI axial images of the lesion showed a reduction in the size of the lesion and perilesional edema (white and blue arrows in k and l, respectively)

After the initial treatment, the patient experienced disease recurrence and underwent two subsequent craniotomies with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Following 5 years of uneventful treatment with temozolomide, the patient reported hearing problems in the right ear in 2022. A follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed residual disease, leading to a redo right temporal craniotomy and tumor decompression in June 2022. As other systemic treatment options had been exhausted, the patient was considered for compassionate use of [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi monomer PET/CT-guided [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 dimer radionuclide therapy.

In the baseline [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi PET/CT scan, focal intense radiotracer uptake is observed in the head region, as shown by the red arrow in the maximum intensity projection (MIP) images (Fig. 1a). This uptake is specifically localized to the right temporo-parietal region, indicated by the white arrow with a standardized uptake value (SULpeak) of 7.6 in the axial PET/CT images (Fig. 1b). Additionally, there is intense radiotracer uptake in the right cerebellar region, represented by the blue arrow with a SULpeak of 23.9 in the axial PET/CT images (Fig. 1c).

Axial T2-weighted MRI images demonstrated two separate lesions. First, there was heterogeneously enhanced nodular lobulated thickening observed in the wall of the post-operative cavity measuring 3.4 × 3.5 cm in temporo-parietal region and was associated with marked perilesional edema (white arrow, Fig. 1d). Second, there was another lobulated heterogeneously enhancing lesion identified, which was contiguous with the post-op cavity. This lesion extended across the tentorium and involved the adjacent right cerebellum. It measured 3.2 × 2.4 × 2.8 cm in size (blue arrow, Fig. 1e).

The patient received two cycles of [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 therapy at a dosage of 7.4 GBq per cycle at 8-week intervals. Post-therapy whole-body scan images were obtained 24 h post-injection (p.i.), as indicated by the green arrow in Fig. 1f and g. These images demonstrated the retention of [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 in the sites corresponding to the [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi and MRI scans.

After completing the second cycle of [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 therapy, an interim post-treatment response assessment was performed using [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi PET/CT imaging after a 5-week period. The assessment showed a substantial reduction in the uptake of the tracer in the MIP images, indicated by the red arrow in Fig. 1h. Additionally, significant reductions in size and uptake were observed in the right temporo-parietal region (SULpeak: 2.5) and the right cerebellar region (SULpeak: 6.1), as depicted by the white and blue arrows in Fig. 1i and j, respectively, on the axial PET/CT images.

Furthermore, follow-up T2-weighted MRI axial images of the lesion confirmed a reduction in the size of the lesion and perilesional edema. This reduction can be observed by the white and blue arrows in Fig. 1k and l respectively, confirming the positive response to the treatment.

Throughout the 10-month treatment and follow-up period, no adverse events were observed. These results highlight the potential of [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 as a comprehensive treatment strategy, particularly for patients with recurrent progressive GBMs who have limited therapeutic options. The theranostic pair [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi monomer/[177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 dimer has emerged as a successful approach for GBM treatment, as demonstrated by our findings. This innovative strategy offers a new dimension to the treatment of GBMs, especially in cases where traditional treatment options are limited. Taken together, our findings strongly support the efficacy and safety of [177Lu]Lu-DOTAGA.Glu.(FAPi)2 as a comprehensive treatment strategy, representing a significant advancement in the management of recurrent progressive GBMs with limited therapeutic options.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data acquisition, collection, and analysis were performed by Sanjana Ballal and Madhav Prasad Yadav. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sanjana Ballal, Madhav Prasad Yadav, and Shobhana Raju. Images were processed and reported by Chandrasekhar Bal and Madhavi Tripathi. Marcel Martin synthesized the precursor and Frank Roesch finalized the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing Interests

Sanjana Ballal, Madhav P. Yadav, Shobhana Raju, Frank Roesch, Marcel Martin, Madhavi Tripathi, and Chandrasekhar Bal have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance received from the institute ethics committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi (Ref No: IEC-483).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to participate in the study, use clinical information to analyze data, and use images for the purpose of publication.

Disclaimer

This work has not been submitted elsewhere and is not under consideration by any other journal.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sanjana Ballal and Madhav P. Yadav contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Yao Y, Tan X, Yin W, Kou Y, Wang X, Jiang X, et al. Performance of 18 F-FAPI PET/CT in assessing glioblastoma before radiotherapy: a pilot study. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;24(22):226. doi: 10.1186/s12880-022-00952-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Windisch P, Röhrich M, Regnery S, Tonndorf-Martini E, Held T, Lang K, et al. Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP) specific PET for advanced target volume delineation in glioblastoma. Radiother Oncol. 2020;150:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habibullah D, Narges J, Reza N, Mykol L, Majid A. PET tracers in glioblastoma: toward neurotheranostics as an individualized medicine approach. Front Nucl Med. 2023;3:1103262. doi: 10.3389/fnume.2023.1103262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balaziova E, Busek P, Stremenova J, Sromova L, Krepela E, Lizcova L, et al. Coupled expression of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV and fibroblast activation protein-alpha in transformed astrocytic cells. Mol Cell Bioche. 2011;354:283–289. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0828-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busek P, Balaziova E, Matrasova I, Hilser M, Tomas R, Syrucek M, et al. Fibroblast activation protein alpha is expressed by transformed and stromal cells and is associated with mesenchymal features in glioblastoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:13961–13971. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busek P, Mateu R, Zubal M, Kotackova L, Sedo A. Targeting fibroblast activation protein in cancer—prospects and caveats. Front. Biosci. 2018;223:1933–68. doi: 10.2741/4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matrasova I, Busek P, Balaziova E, Sedo A. Heterogeneity of molecular forms of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV and fibroblast activation protein in human glioblastomas. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2017;161:252–60. doi: 10.5507/bp.2017.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandya DN, Sinha A, Yuan H, Mutkus L, Stumpf K, Marini FC, et al. Imaging of fibroblast activation protein alpha expression in a preclinical mouse model of glioma using positron emission tomography. Molecules. 2020;25:3672. doi: 10.3390/molecules25163672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.