Abstract

Conventional selective breeding in aquaculture has been effective in genetically enhancing economic traits like growth and disease resistance. However, its advances are restricted by heritability, the extended period required to produce a strain with desirable traits, and the necessity to target multiple characteristics simultaneously in the breeding programs. Genome editing tools like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) are promising for faster genetic improvement in fishes. CRISPR/Cas9 technology is the least expensive, most precise, and well compatible with multiplexing of all genome editing approaches, making it a productive and highly targeted approach for developing customized fish strains with specified characteristics. As a result, the use of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in aquaculture is rapidly growing, with the main traits researched being reproduction and development, growth, pigmentation, disease resistance, trans-GFP utilization, and omega-3 metabolism. However, technological obstacles, such as off-target effects, ancestral genome duplication, and mosaicism in founder population, need to be addressed to achieve sustainable fish production. Furthermore, present regulatory and risk assessment frameworks are inadequate to address the technical hurdles of CRISPR/Cas9, even though public and regulatory approval is critical to commercializing novel technology products. In this review, we examine the potential of CRISPR/Cas9 technology for the genetic improvement of edible fish, the technical, ethical, and socio-economic challenges to using it in fish species, and its future scope for sustainable fish production.

Keywords: Selective breeding, Aquaculture, Genetic improvement, Genome editing, CRISPR/Cas9, Edible fish

Introduction

Global food security remains the major challenge associated with the intake of nutritious food by the rapidly growing population (FAO 2020). It was found that to meet the demand for high-quality food, about 40% of the land has already been used for terrestrial animals and crop production (FAO 2014), resulting in the loss of species diversity, habitat degradation (Herrero et al. 2015), unmanageable freshwater utilization (Mekonnen and Hoekstra 2012; Herrero et al. 2015), pollution in the biomes (Bouwman et al. 2013), and vast releases of greenhouse gases (Tilman and Clark 2014). The competition for land and its adverse effects constrain the growth of terrestrial livestock and crop production. Subsequently, it has been directed to several environmental and health studies evaluating the advantage of changing diets to other protein sources, including seafood (Springmann et al. 2016).

Seafood consumption has increased quickly, with an annual rate of 3.1%, more than the terrestrial animal production growth of 2.1% from 1961 to 2017. The consumption rate is approximately double that of the global population growth rate of 1.6% per year in the same period (FAO 2020). However, the total production from the capture fisheries has remained comparatively constant for the past two decades, and if the intake continues, it will be imperative to produce more food via an appropriate approach (Springmann et al. 2016). Although there is no one-size-fits-all tactic to meet the projected need for food, aquaculture is considered one of the instant suggestions (Azra et al. 2021).

The sector has several species comprised around 543 diverse groups of finfish and shellfish species, including 362 finfishes, 104 mollusks, 62 crustaceans, and 15 other aquatic animals (Houston et al. 2020). Thus, it contributes to a significant share in providing a variety of products that are copious in protein, vitamins, minerals, and micronutrients (Subasinghe et al. 2009). Furthermore, aquatic products, especially fish, are a good source of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, critical for human health and not abundant in most land-based protein sources (Rimm et al. 2018). Also, the production is highly efficient regarding feed conversion and nutrient retention compared with most terrestrial animal production (Fry et al. 2018). Besides these, the sector offers vast expansion potential since approximately 1% of marine sites are exploited for aquaculture production (Gentry et al. 2017). In 2018, global fish production reached about 179 million tons, of which 82 million tons came from aquaculture production (FAO 2020). It indicates that fish production through aquaculture is almost equal to capture fisheries, and it will be a significant source of seafood in the coming decades.

As the aquaculture industry expands, the sustainability of present and future production is a significant problem. Furthermore, the industry faces other issues, particularly in seed production, disease management, control of environmental stresses, and the production of traits of interest for phenotypically improved strains (Diwan et al. 2017). Therefore, several studies are being made to develop more systematic aquaculture practices, which have produced considerable progress. At this juncture, a significant increase in productivity can be ensured by integrating biotechnological tools with traditional breeding practices (Abushweka 2021). The new CRISPR genome editing mechanism can make specific and targeted changes in the genome, enabling the genetic enhancement of candidate fish species (Gaj et al. 2016). This paper reviews the tremendous potential of CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9) technology for the genetic improvement of edible fish, the major constraints on the technology, and the future scope and contributions that the technology could make to the development of a global, sustainable food production system.

Genetic improvement in edible fishes

Over the past five decades, genetic improvement of terrestrial livestock has been done for diverse species, and selective breeding programs have resulted in rapid, economical, and efficient food production globally (Schultz et al. 2020). For example, the milk production efficiency of cattle has increased by 67%; the eggs per year of chicken have risen by 37%, and similar developments have been made for many beneficial traits in various species (Van der Steen et al. 2005; Van Eenennaam 2017). However, in the case of farmed fishes, even though older traditional fish species are pretty domesticated, the majority of the fishes are either obtained from the wild or yet in the initial stage of domestication. It signifies that there is considerable potential for genetic gain in fish species for various economic traits, and it could be attained by exploiting the untapped genetic potential of farmed fishes for selective breeding programs (Houston et al. 2020). This would enable the genetic enhancement of the desired species and could ultimately result in better production, lower expenses, higher consumption, and, in some cases, enhanced nutritional conditions for some regions of the human population (Ansah et al. 2014). Several genetic improvement programs, such as selective breeding, intraspecific and interspecific crossbreeding, polyploidy, chromosomal set manipulation, and modification breeding, have been employed to enhance the productivity of fish species (Abushweka 2021).

Conventional selective breeding programs in which fish with desired traits are selected and mated to produce better quality progeny (Hulata et al. 1976; Kincaid et al. 1977; Bolivar and Newkirk 2002; Kause et al. 2005; Dunham 2006; Gheyas et al. 2009). The first selective breeding for fish was reported in 1919, using brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) to enhance survival rate through furunculosis. The survival rate of trout has increased from 2 to 69% after three generations (Embody and Hyford 1925). Also, salmonids and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) were used for large-scale breeding programs in the 1970s and 1988 (Pullin et al. 1991; Gjedrem 1997). After that, a series of selection experiments were conducted in many fishes like carp species (Kirpichnikov et al. 1993; Hussain et al. 2002; Gjedrem & Baranski 2009), channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) (Dunham & Smitherman 1983), Nile tilapia (O. niloticus) (Eknath et al. 1998), seabream (Sparus aurata) (Knipp 2000) and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (Hulata 2001) for better growth rate and disease resistance. However, that method cannot easily or deliberately attain a preferred phenotype because natural mutations can happen randomly. Also, establishing a novel strain via selective breeding will require many generations (Dunham and Smitherman 1983).

To solve those problems in the aquaculture industry, researchers have tried a breeding method that instigates random mutagenesis by either physical or chemical mutagens. Physical mutagens include X-rays, gamma rays, UV rays, and particle radiation, while chemical mutagens include alkylating agents (ethyl methanesulfonate or N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea [ENU]) and azides (Kodym and Afza 2003). Chemical mutagenesis was successfully applied in the aquaculture fish fugu (Takifugu rubripes). ENU-induced mutations identified in the myostatin (Mstn) gene produced a beneficial phenotype (e.g., increased muscle mass production and fast growth) (Kuroyanagi et al. 2013). However, that method is also time-consuming as finding mutants that produce the preferred phenotype takes excessive effort.

Next, researchers tried knocking down genes related to production traits using RNA interference (RNAi) technology, and fish were the first vertebrate species to be tested for RNAi-mediated knockdown of gene expression and consequently desirable traits (Wargelius et al. 1999). However, only a limited number of studies have shown successful outcomes due to conflicting results from using long dsRNA in fish (Wargelius et al. 1999; Li et al. 2000; Acosta et al. 2005). The main limitations of RNAi are nonspecific off-target effects, transient knockout effects, variability, and incomplete knockdown; it is also time-consuming and labor-intensive (Wargelius et al. 1999; Arora and Narula 2017).

Transgenesis technology next took the spotlight by quickly producing strains with valuable traits. GMOs are organisms produced by transgenic technologies through the introduction of exogenous DNA, which do not naturally occur in the wild population (Zhang et al. 2016). Thus, GMOs, including edible fish, generally have not been positively accepted by society as healthy food due to concerns about food safety and gene spill from farmed fish into the wild population through unintentional release (Shew et al. 2018).

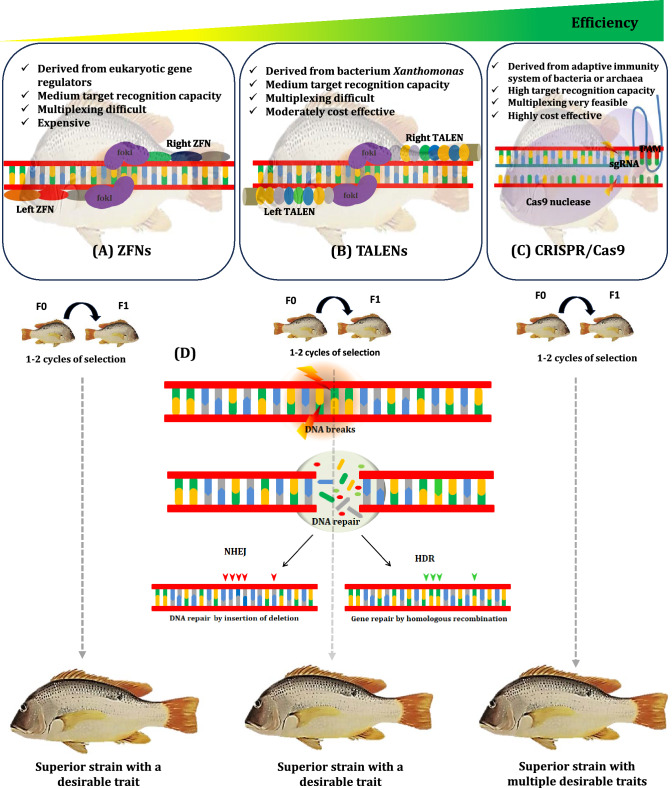

Recently, revolutionary progress has been made in reverse genetics with the advance of genome editing technologies, which could be applied to fish breeding programs. Genome editing tools could significantly expedite the genetic enhancement process in contrast to long-term genetic improvement approaches such as selective breeding (Abdelrahman et al. 2017; Wargelius 2019). In the past few years, more efficient genome editing techniques, such as ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas9, have made a gateway for various fields of biological sciences by constant technological developments (Fig. 1). An artificial endonuclease known as ZFN (zinc finger nuclease) was first introduced in 1996 (Kim et al. 1996), which combines a zinc finger DNA-binding domain with a FokI DNA cleavage domain. Specifically, each zinc finger DNA-binding domain encompasses three to six zinc finger clusters, and each unique module specifically identifies three nucleotides in the target DNA, thereby allowing each DNA-binding domain to identify or target 9 to 18 base pairs (Urnov et al. 2010). Another requirement for target DNA cleavage is the dimerization of two zinc finger binding domains, allowing the FokI enzyme to expose double-strand breaks (DSBs) at the predetermined DNA sequences (Durai et al. 2005). Therefore, ZFN, theoretically, is a perfect genome editing tool for inducing specific edits at target DNA sequences in any organism (Gupta and Musunuru 2014). This method has been applied in farmed fishes, such as killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus) (Aluru et al. 2015), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (Yano et al. 2012; Yano 2014), and channel catfish (I. punctatus) (Qin et al. 2016). However, its application has been narrowed by the design and synthesis of the zinc finger motifs and its low specificity; also, the technology is laborious and expensive (Urnov et al. 2010; Aluru et al. 2015).

Fig. 1.

Fish genome editing in a targeted manner to produce superior strains with desirable features utilizing genome editing tools, such as ZFNs (Zinc finger nucleases), TALENs (Transcription activator-like effector nucleases), and CRISPR/Cas9 (CRISPR-mediated RNA-guided DNA endonucleases). A ZFNs comprise a DNA-binding zinc finger domain and a nuclease domain derived from the restriction enzyme FokI. Zinc fingers recognize triplets, and the associated FokI nuclease dimerizes and cuts in the spacer region between two unique zinc finger target sites. B TALEN differs from ZFN in that the binding array components recognize individual nucleotides, and the two distinct TALENs recognize and bind to specific locations on opposite DNA strands; the assembled FokI dimer cleaves target DNA precisely. C The CRISPR/Cas9 system comprises a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and a nuclease termed Cas9. The DNA site is recognized in the CRISPR-Cas9 system by base complementarity between genomic DNA and sgRNA, connected with tracrRNA, and loaded into Cas9 nuclease, which accomplishes DNA cleavage. Cleavage occurs three bp upstream of the PAM (Protospacer adjacent motif) on both strands. D Nuclease (FokI or Cas9) breaks the target DNA sequence, causing a double-strand break (DSB) that can be repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). Random insertions or deletions (indels) occur at the editing site in the NHEJ pathway, frequently resulting in gene disruption. A donor template containing sequences homologous to the DSB flanking areas can be inserted into genomic DNA, resulting in gene repair. Thus, the better strain of fish generated utilizing three separate genome editing tools, in which the fish developed using CRISPR/Cas9 technology was inexpensive, could target several genes simultaneously for diverse desirable qualities with high targeting efficiency and precision

The second-most applied genome editing method is called TALENs (transcription activator-like effector nucleases), which was developed from the bacterial plant pathogen Xanthomonas with transcription activator-like effector (TALE) proteins (Bedell et al. 2012; Sanjana et al. 2012; Wright et al. 2014). TALEN is similar to ZFN in that it pairs a nonspecific FokI endonuclease domain to a DNA binding domain that identifies arbitrary base sequences at the target site. One of the critical features of TALEN is its highly conserved 33 to 35 tandemly arrayed repeats, with the presence of Repeat Variable Diresidues (RVD), characterized by variations of amino acids found within 12th and 13th amino acid residues. This RVD plays a vital role in the specific identification of a single nucleotide sequence (Moscou and Bogdanove 2009). The formation of DSB at the target locus is accomplished by a random cleavage of the DNA sequences in bi-directions (left and right) of the TALEN target sites, which is carried out by the dimerized FokI (Christian et al. 2010). This technology has been used in various commercially important fishes for different traits of interest, such as tilapia (O. niloticus) for reproduction development (Li et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2016); common carp (Cyprinus carpio), yellow catfish (Tachysurus fulvidraco), and sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus) for growth enhancement (Dong et al. 2014; Zhong et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2018); cavefish (Astyanax mexicanus) (Ma et al. 2015) for albinism; pacific blue-fin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) for slow swimming behavior (Higuchi et al. 2019).

Until the early 2010s, TALEN was a potent genome-editing tool; however, the introduction of a more efficient and versatile genome editing tool called CRISPR/Cas9 in 2013 far outweighs the benefits of using TALEN. Moreover, the design and the synthesis of components for CRISPR/Cas9 are more economical, easier, and efficient compared to ZFN and TALEN, allowing high-throughput genome editing in model organisms (Ansai and Kinoshita 2014; Chen et al. 2018; Varshney et al. 2016; Zhong et al. 2016). Also, the CRISPR/Cas9 system can transfer multiple small guide RNAs (gRNAs) at the same time, which enables multiplexing (Cong et al. 2013; Cleveland et al. 2018; Datsomor et al. 2019b; Zhu and Ge 2018). Mechanistically, CRISPR/Cas9 system has similarities and differences to those applied in ZFN and TALEN. The major difference between CRISPR/Cas9 system and the previous genome-editing techniques (ZFN and TALEN) is using Cas9 as an endonuclease and sgRNA as a DNA binding domain. sgRNA comprises CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA). While crRNA is a small 18–20 base pair molecule that interacts with the target sequence to identify the target DNA, tracrRNA is a long loop that serves as a binding scaffold for the Cas9 nuclease (Asmamaw and Zawdie 2021). The Cas9 protein can introduce DSBs at the target site, and that activates the DNA repair system either via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed DNA repair (HDR) mechanism (Durai et al. 2005). The DNA repair system, such as NHEJ and HDR, is crucial, as mutations due to NHEJ-induced insertion or deletion (indels) often lead to a frameshift in the coding regions, while HDR is employed for specific gene editing or knock-in of a foreign DNA fragment by homologous recombination (Gratz et al. 2014).

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has seen significant advancements in genetic engineering, particularly in modifying Cas9 and sgRNA to achieve more precise editing. Cas9n, an inactivating mutation in the endonuclease cleavage domains, can abolish the endonuclease activity of the RuvC or HNH domains. Combining Cas9n with two separate sgRNAs can produce a staggered double-strand break (DSB), enhancing the efficiency and specificity of the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Ran et al. 2013a). Dead Cas9 (dCas9), generated by preventing the enzymatic activities of RuvC and HNH domains in the Cas9 nuclease, can direct transcriptional perturbation of target genes without modifying the DNA. This system, also known as CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), provides two functions: dCas9 fusion-mediated inhibition (CRISPRi) and dCas9 fusion-mediated activation (CRISPRa). dCas9 can block or activate gene expression after being fused to a repressor (such as Krüppel-associated box (KRAB)) or activator (VP64, Rel A, and Rta proteins, known as the VPR system) (Lawhorn et al. 2014).

By integrating epigenetic effectors with specific DNA binding domains, CRISPR can also introduce epigenetic alterations. Chromatin editing is one epigenome engineering strategy that can be maintained across cell divisions. The CRISPRoff system, which uses dead Cas9 proteins linked to enzymes that mediate DNA methylation of restrictive histone modifications, was developed to silence most genes in a heritable manner (Nuñez et al. 2021).

CRISPR/Cas9 tools were also expanded to allow single base replacements, using base editors of a Cas9 nickase and a nucleotide deaminase enzyme. SgRNA-directed Cas9 protein binding opens the double helix, enabling cytidine deaminase base editors (CBEs) or adenosine deaminase base editors (ABEs) to deaminate C-to-U or A-to-I, respectively. Cas9 nickase induces DNA repair by creating a nick in the unedited strand. The new U base-pairs with A and the new I base-pairs with C as the deaminated base serves as a template for DNA polymerization, resulting in modifications from C:G to T:A and A:T to G:C (Horodecka and Düchler 2021). The most advanced technique is ‘prime editing,’ which allows all 12 possible base exchanges in addition to small insertions or deletions without causing double-strand breaks (kantor et al. 2020). Prime editing employs a reverse transcriptase attached to the Cas9 nickase and specific guide RNAs (pegRNAs and prime editing guide RNAs), including the primer-binding site and an RT template sequence. Insertions (up to 40 bp) and deletions (up to 80 bp) are also possible without causing double-strand breaks (Horodecka and Düchler 2021). Thus, the fish mutants that use Cas9 variants will allow genome editing to occur precisely without causing undesired mutations. Currently, there are no reports of base modification methods or Cas9 variants (such as dcas9 or cas9n) being used on fish species. In farmed fishes, most genome editing experiments were performed based on gene knockout, which does not introduce any foreign DNA into the genome of interest species and is a small controlled modification to the original DNA that improves the intended feature by removing the inferior allele. This review has focused more attention on the CRISPR/Cas9-based knockout.

The potential of CRISPR/Cas9 in the genetic improvement of farmed fish

CRISPR/Cas9 technology can reduce the chances of natural mutations compared to classical breeding programs by significantly shortening the generation time and allowing for precise control over genetic modifications (Fig. 2). Key factors contributing to the reduction of natural mutations include precision and targeted editing with reduced genetic variation and generation time, which minimize the likelihood of unintended genetic changes (Huitema 2017; Hryhorowicz et al. 2023). Classical breeding introduces a significant amount of genetic variation with each generation, which can lead to in/del of unexpected traits and undesirable mutations. Precisely, CRISPR/Cas9 creates desired genetic changes in a single generation itself, reducing the number of opportunities for natural mutations to occur (Huitema 2017; Singer et al. 2021). Additionally, CRISPR/Cas9 allows one to have precise control over the genetic modifications they introduce, allowing for the removal of deleterious mutations or the introduction of beneficial ones. This level of control is challenging to achieve through classical breeding, where genetic changes are largely a result of random recombination (Hryhorowicz et al. 2023). Thus, CRISPR/Cas9 is a genetic engineering technology that offers a faster, more precise, and controlled method for achieving desired phenotypes in organisms. It also reduces the risk of natural mutations, unwanted genetic changes, and unpredictable outcomes, making it a powerful tool in genetic engineering (Veillet et al. 2020; Singer et al. 2021; Hryhorowicz et al. 2023).

Fig. 2.

Developing a disease-resistant fish population with a high growth rate for potential commercial application: Comparison of conventional selective breeding and the novel CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system. A For example, in conventional selective breeding, a donor strain of high disease resistance but relatively low growth rate crosses with a strain with a high growth rate but comparatively low disease resistance. The fish population developed in that way will ultimately be highly disease-resistant and have a high growth rate. However, the introgression of desirable traits into the selected fish requires successive backcrossing, followed by the laborious screening of subsequent generations for desirable traits, which requires much time and energy. In addition, undesirable genes from the donor strain will be incorporated along with the desired gene, and genetic dilution of the recipient commercial strain will occur. B In genome editing, the disease susceptibility gene will be disrupted in a strain with a high growth rate using the CRISPR/Cas9 system, and the resulting lines of the fish population will be disease-resistant and have a high growth rate. The homozygous mutant fish population could be produced with 1–2 breeding cycles. Thus, CRISPR/Cas9 technology enhances the speed of the fish breeding process through targeted and precise genome editing without requiring much time, and it avoids the genetic dilution that usually occurs during the conventional breeding process

The CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system has demonstrated its potential in revealing the genetic regulation of economically valuable traits and how such findings have contributed to genetic gains in fish breeding programs. Indeed, this technology could identify the putative genes responsible for underlying quantitative trait loci (QTL) by evaluating the results of gene knockouts on the desirable trait. That could help fix the trait of interest by genome editing and allow the introgression of favorable alleles or de novo variants into candidate fish species (Houston et al. 2020). One of the model examples includes Atlantic salmon (S. salar) farming, in which two major barriers limit expansion in the aquaculture industry. Most Atlantic salmons are farmed in open sea-cages, a production method fraught with sustainability issues such as disease transmission from wild to farmed fish and vice versa, as well as escaped farmed fish affecting wild populations (Taranger et al. 2015). The development and use of sterile salmon in production could be one solution to prevent wild introgression in Atlantic salmon. The gene encoding dead end (dnd) has been targeted to cause sterility in salmon, hindering germ cell development (Wargelius et al. 2016). This was accomplished through targeted mutagenesis against dnd with CRISPR/Cas9, resulting in a gene-edited sterile fish. The second barrier to Atlantic salmon production is high mortality in wild populations of salmon associated with the parasite salmon louse. To treat the disease, drugs that could pose environmental hazards were used, such as Azamethiphos, pyrethroid (such as Cypermethrin and deltamethrin), Emamectin benzoate, Teflubenzuron and diflubenzuron (Wargelius 2019; Cerbule et al. 2020). Chemical treatments have decreased in efficacy over time, leading to increased resistance in salmon louse populations. This pattern is consistent across all countries, with resistance likely developing if new treatments are introduced. For instance, organophosphate azamethiphos treatment significantly differs between sensitive and resistant strains, with sensitive strains suffering almost 100% mortality and resistant strains only 19%. Chemical treatments have also been used in increasing concentrations, with decreasing efficacy, particularly for pyrethroid and organophosphates. Thus, chemical treatments are temporary until resistance develops within a salmon louse population (Cerbule et al. 2020). In this context, genetic modification of the salmon genome to produce resistance to the louse could reduce the mortality of salmonids and the use of pernicious medications (Wargelius 2019). The genetic modification for disease resistance can be attained precisely through CRISPR/Cas9 technology.

Another challenge in commercial fisheries is managing breeding and spawning in confined conditions at economically relevant times. Encouraging maturation using hormonal methods had only limited success. CRISPR/Cas9 can be applied to edit the genes that encode the production of gonad-stimulating hormones at particular times, thereby continuously maintaining an appropriate hormonal titer to speed the maturation process (Diwan et al. 2017). It is also noticeable that silencing the target gene may not always result in the preferred phenotype due to epistasis (Ho et al. 1997; Mohandas 2016). So, focusing on a multiple-trait approach will benefit developing fish populations with superior characteristics. Since CRISPR/Cas9 enables multiplexing, it could effectively focus on multiple traits in the fish population and overcome the difficulties associated with domesticating commercially important fishes (Toomey et al. 2020).

CRISPR/Cas-based genome editing in farmed fishes: Basic methodology

The CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in edible fish involves some critical steps (Fig. 3). First, the desired gene must be chosen for targeted mutagenesis after examining the genome database of targeted species. The sgRNA needs to be developed from the targeted sequence using a sgRNA designing tool, and oligo synthesis of sgRNA must be performed. There are different strategies to conduct the genome editing, such as plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 delivery system, in vitro-transcribed sgRNA and Cas9 system, ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-based system, and can be delivered into one cell stage of embryo either through microinjection or electroporation (Chakrapani et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2021; Clark et al. 2022; Taha et al. 2022). The progeny should be carefully screened using sequence analysis to detect off-target mutations. It is crucial to choose off-target free progeny, breed them with wild type, and create heterozygous mutants. To produce homozygous F2 offspring, the F1 heterozygous fish population should be intercrossed. The ultimate step is the selection of fish species with desired phenotypes and the establishment of genetically improved species in aquaculture (Okoli et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2022).

Fig. 3.

The general procedure for CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing in farmed fishes. After selecting the target gene from the candidate species genome database, sgRNA needs to be generated with the sgRNA design tool, and then sgRNA oligo must be synthesized. The mixture sgRNA and Cas9 protein is delivered into one cell stage of the fish embryo via microinjection or electroporation. Fish mutants are screened using mutagenesis analysis methods, such as heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA), high-resolution melting curve analysis assay (HRMA), mismatch cleavage assay, or sequencing method. The final stage is off-target free mutant selection, crossing with wild populations and producing a specific mutant line, assessing CRISPR-induced mutation-associated phenotype, and generating new varieties with desired traits in aquaculture

Importance of species selection

For transgenic or genome-edited fish study purposes, several parameters should be considered for selecting fish species as each species features differences in superiority over others for different purposes; this includes (1) life cycle length, (2) availability and characteristics of eggs and sperm, (3) duration of embryonic development, (4) culturing conditions, and (5) knowledge of the genetics, physiology, and reproduction of the species (Chen and Chen 2020).

Fish species simplify genome editing due to the high fecundity rate, external fertilization, and the accessibility of the reference genome of most of the key fish species (Yue and Wang 2017; Houston et al. 2020). However, genetic improvements in edible fish have confronted challenges including long generation time (Atlantic salmon (3–4 years), Olive flounder (3 years), common carp (1–4 years)), unreliable spawning, and low survival rate (Jin et al. 2021). Adoption of artificial fertilization using cryopreserved germ cells and integration of the CRISPR/Cas9 mechanism with surrogacy technology could solve the existing limitations of the method (Nagasawa et al. 2019; Jin et al. 2021). Thus, the improved CRISPR/Cas9 with surrogacy technology could effectively be applied in cultured species with a long generation time, species exhibiting unreliable spawning, and species that are difficult to culture in captivity by producing germ cells in easier-to-breed recipient species. The gene-edited embryonic stem (ES) cells, primordial germ stem cells (PGCs), and gonadal germ stem cells could be powerful tools to generate fish with targeted genetic changes. The gene-edited ES cells could be introduced into the recipient fish embryo at the blastocyst stage and produce gene-edited embryos. In the resulting progeny, the ES cell could contribute to the development and give rise to several tissue types, including germline cells, leading to the generation of gene-edited ES cell-derived fish in vivo. Similarly, the germline transmission of gene-edited PGCs and gonadal germ stem cells into the blastula stage of host fish embryo, hatchling, or adult stage could also result in fish with desired traits for the same or different species of fishes with the integration of surrogacy technology (Bradley et al.1984; Hong et al. 2011) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Genome edited fish production via CRISPR/Cas9 based germline mutation and surrogacy technology. The primordial germ stem cells (PGCs)/ germline stem cells (GSCs) from fish will be isolated, cultured, and edited using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. The genome-edited germ stem cell is screened for successful edits and then transplanted into a sterilized (germ cell-less or ablated) surrogate fish with a short generation time via microinjection. The resultant progeny will produce male and female gamete based on the sex of the surrogate fish. Mixing these gametes will generate a fish with improved values in a shorter period

In addition, in the case of farmed fishes, although several important fish species’ genomes are sequenced, for certain species, the reference genome has not yet been fully annotated, which is vital to accomplish genome editing efficiently. For example, in Atlantic salmon, the sequenced genomes are poorly interpreted, limiting the application of genome editing in salmon and demanding additional refinement (Sundaram et al. 2017). However, the advancement in the genetic and molecular methods (such as next-generation sequencing, family QTL mapping, functional and comparative genomics, and pooled CRISPR screen) would result in trait-associated genes being recognized rapidly and genes being well interpreted (Houston et al. 2020).

Over the past few years, due to the technical improvement of CRISPR/Cas9, it has been successfully used in many edible fish species (both in vitro and in vivo), such as Salmonidae (Atlantic salmon (S. salar), Chinnok salmon (O. tshawytscha), and rainbow trout (O.mykiss)), Cyprinidae (rohu (Labeo rohita), common carp (Cyprinus carpio), white crucian carp (Carassius civieri), gilbel carp (C. auratatuscivieri), and grass carp (Ctenopharyngdon Idella)), Siluridae (channel catfish (I. punctatus), southern catfish (Silurus meridionalis), and yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco)), Nile tilapia (O. niloticus), Red sea bream (Pagrus major), Olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus), Sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus), Loach (Paramisgurnus dabryanus), Blunt snout sea bream (Megalobrama amblycephala), cichlid (Astatotilapia calliptera and A. burtoni), and Tiger puffer fish (T. rubripes) to efficiently enhance different traits of interest to aquaculture in a short period (For details and references refer Table 1). Nile tilapia and Atlantic salmon are the most targeted fishes and are employed as aquaculture model species for using CRISPR/Cas9. Reviewing the choice of species selection for the application of CRISPR/Cas9 technology, it was identified that there is a link between species selected and the commercial importance of the particular species in that respective geographical area. For example, Atlantic salmon has high commercial importance in Norway, which accounts for approximately 50% of the world’s Atlantic salmon production, and it is the same country that has done the most research on the application of CRISPR/Cas9 in Atlantic salmon (Industri 2017). Similarly, CRISPR/Cas9 technology has typically been utilized the most on channel catfish in the United States, where the former is considered the major cultured species (Hanson and Sites 2011).

Table 1.

Potential applications of CRISPR/Cas9 in farmed fishes (In vitro and in vivo)

| Species | Target gene | Desirable trait | Mode of CRISPR/Cas9 |

Remarks | Delivery method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Atlantic salmon Salmo salar |

tyr/slc45a2 | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Edvardsen et al. 2014 | |

| tyr/slc45a2 | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | HDR | Microinjection | Straume et al. 2020 | |

| dnd (slc45a2) | Sterility | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Wargelius et al. 2016 | ||

| dnd (slc45a2) | Sterility | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Guralp et al. 2020 | ||

| dnd (slc45a2) | Sterility | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | HDR | Microinjection | Straume et al. 2021 | |

| elov-2 | Omega-3 metabolism | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Datsomor et al. 2019a | ||

| Omega-3 metabolism | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Datsomor et al. 2019b | |||

|

Chinook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha Wlbaum |

egfp | Trans-GFP | Plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system | In vitro | Lentivirus-based transfection | Gratacarp et al. 2019 |

| Megsfp | Trans-GFP | gRNA, plasmid-based cas9 system | In vitro | Chemical-based transfection | Dehler et al. 2016 | |

| stat2 | Disease resistance | gRNA, plasmid-based cas9 system | In vitro | Chemical-based transfection | Dehler et al. 2019 | |

|

Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus |

dmrt1/nanaos2-3/foxl2 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Li et al. 2014 | |

| Gsdf | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Jiang et al. 2016 | ||

| aldh1a2/cyp26a1 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Feng et al. 2015 | ||

| sf-1 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Xie et al. 2016 | ||

| dmrt6 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Zhang et al. 2016 | ||

| Amhy | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Li et al. 2015 | ||

| Amh | Sex determination | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Liu et al. 2020 | ||

| wt1a/wt1b | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Jiang et al. 2017 | ||

| eef1A1b | Fertility | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Chen et al. 2017 | ||

| igf3 | Sex determination | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Li et al. 2020 | ||

| rln3a/3b | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Yang et al. 2020 | ||

| esr1, esr2a, esr2b | Fertility | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Yan et al. 2019 | ||

| cyp11c1 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Zheng et al. 2020 | ||

| piwil2 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Jin et al. 2020 | ||

| foxh1 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Tao et al. 2020 | ||

| tsp1a | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Jie et al. 2020 | ||

| miRNA, Vasa-3’UTR | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Li et al. 2019 | ||

| Mstn | Growth | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | AquaBounty Company | ||

| slc45a2 | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Segev-Hadar A et al. 2021 | ||

| Mozambique tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus | nanos3 | Reproduction and development | Plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system | In vitro | Lipid-based transfection | Hamar and Kultz 2021 |

|

Red sea bream Pagrus major |

Mstn | Muscle Development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Kishimoto et al. 2018 | |

|

Yellowhead catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco |

pfpdz1 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Dan et al. 2018 | |

|

Channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus |

Mstn | Growth | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Khalil et al. 2017 | |

| ticam1/rbl | Disease resistance | gRNA, Cas9 protein | HDR | Microinjection | Elaswad et al. 2018b | |

| ticam1/rbl | Disease resistance | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Elaswad et al. 2018a | ||

| Cath | Disease resistance | gRNA, Cas9 protein | HDR | Microinjection | Simora et al. 2020 | |

|

Southern catfish Silurus meridionalis |

cyp26a1 | Germ cell development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Li et al. 2016 | |

|

Common carp Cyprinus carpio |

sp7a/sp7b/mstnba, runx2, opga, bmp2ab | Muscle development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Zhong et al. 2016 | |

| MCIR | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Mandal et al. 2020 | ||

| ASIP | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Chen et al. 2019 | ||

| Cyp17a | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Zhai et al. 2022 | ||

| Tyr | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Xu et al. 2022 | ||

|

Rohu Labeo rohita |

TLR22 | Disease resistance | Plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system | Microinjection | Chakrapani et al. 2016 | |

|

Grass Carp Ctenopharyngdon Idella |

JAM-A | Disease resistance | Plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system | In vitro | Lipofection (Lipofectamine 2000) | Ma et al. 2018 |

|

Gibel carp Carassius auratatuscivieri |

cgfoxl2a-B, cgfoxl2b-a, cgfoxl2b-B | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Gan et al. 2021 | |

|

Rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss |

igfbp-2b1/2b2 | Growth | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Cleveland et al. 2018 | |

|

Olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus |

Mstn | Growth | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Kim et al. 2019 | |

| myomaker, gsdf | Growth, reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Electroporation | Wang et al. 2021 | ||

| PoMaf1 | Disease resistance | Plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system | In vitro | Chemical-based transfection (ViaFect™ transfection reagent) | Kim et al. 2021 | |

|

White crucian carp Carassius civieri |

Tyr | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Liu et al. 2019 | |

|

Sterlet Acipenser ruthenus |

dnd1 | Reproduction and development | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Baloch et al. 2019 | |

| ntl, egfp | Growth, trans-GFP | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Chen et al. 2018 | ||

|

Loach Paramisgurnus Dabryanus |

Tyr | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Xu et al. 2019 | |

| Blunt snout sea bream Megalobrama amblycephala | mstna, mstn b | Growth | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Sun et al. 2020 | |

|

Tiger pufferfish Takifugu rubripes |

Mstn | Growth | gRNA, Cas9 mRNA | Microinjection | Kishimoto et al. 2019 | |

|

Malawi cichlid Astatotilapia calliptera |

Oca2 | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Clark et al. 2022 | |

|

African cichlid Astatotilapia burtoni |

Tyr | Pigmentation | gRNA, Cas9 protein | Microinjection | Li et al. 2022b |

aldh1a2 (aldehyde dehydrogenase family 1, subfamily A2), amh (anti-Mullerian hormone), ASIP (agouti signaling protein), bmp2ab (bone morphogenetic protein 2), Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated protein 9), cath (cathelicidin), cgfoxl2 (carassius gibelio forkhead box protein L2); CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9), cyp11c1 (cytochrome P450 11c1), cyp17a1 (cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily a, polypeptide 1), cyp26a1 (cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily a, polypeptide 1), dmrt1 (doublesex and mab-3-related transcription factor 1), dmrt6 (doublesex and mab-3-related transcription factor 6), dnd (dead end miRNA-mediated repression inhibitor), eEF1A (Eukaryotic elongation factor 1 alpha, egfp (enhanced green fluorescent protein), elovl-2 (ELOVL fatty acid elongase 2), esr1, esr2a, esr2b (estrogen receptor gene 1, 2a and 2b), fads (fatty acyl desaturases), foxh1 (forkhead box gene h1), foxl2 (forkhead box L2), gRNA (guide ribonucleic acid), gsdf (gonadal somatic cell-derived factor), HDR (homologous directed repair), igf3 (insulin-like growth factor 3), igfbp-2b1/2b2 (IGF-binding protein 2b1/2b2), JAM-A (Junctional adhesion molecule-A), MCIR (melanocortin 1 receptor), megfp (monomeric enhanced green fluorescent protein), miRNA, microRNA (non-coding sequence), mstna/mstnb (myostatin a/b), nanos2 (nanos C2HC-type zinc finger 2), nanos3 (nanos C2HC-type zinc finger 3), ntl (no tail), oca2 (oculocutaneous albinism type 11 gene), opga (osteoprotegerin), pfpdz1 (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco PDZ domain-containing protein), piwil2 (piwi-like RNA-mediated gene silencing 2), PoMaf1 (Paralichthys olivaceus MAF1), rbl (rhamnose-binding lectin), rln3a/b (relaxin 3), runx2 (runt-related transcription factor 2), sf-1(steroidogenic factor 1), sp7a/sp7b, sp7 (specificity protein transcription factor 7), slc45a2 (solute carrier family 45 member 2), stat 2 (signal transducer and activator 2), ticam1 (toll-like receptor adaptor molecule 1), TLR22 (toll-like receptor 22), tsp1a (thrombospondin 1a), trans-gfp (trans-green fluorescent protein), tyr (tyrosinase), vasa-3’UTR (associated with germ cell development), wt1a/b (Wilms tumor 1 transcription factor a/b)

Selecting a trait of interest and target gene

The traits that have already been considered important targets for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome-editing studies of fish are reproduction and development, growth, disease resistance, pigmentation, and omega-3 fatty acid metabolism. In addition to the genes involved in economically valuable traits, exogenous genes, such as EGFP and mCherry, have been used in farmed fish, especially in chinook salmon (O. tshawytscha), for identifying the efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Dehler et al. 2016; Gratacap et al. 2020).

Reproduction

With the advantages offered by the CRISPR/Cas9 system, scientists are now mainly targeting the genes associated with reproduction in fish to understand the genetics that regulate sex differentiation and sex determination. In particular, gonads have been considered a crucial reproductive organ involved in sex-related regulation and the site for differentiation and derivation of germ cells from primordial germ cells (PGCs) in embryos. The genes known to contribute to PGC formation and maintenance are dead end (dnd), nanos C2HC-type zinc finger 2 (nanos2), and nanos C2HC-type zinc finger 3 (nanos3), possibly implicating that knockout of these genes can lead to sterility in fish (Li et al. 2014; Zhu and Ge 2018). For example, the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene silencing of dnd gene in Atlantic salmon exhibited F0 mutant with loss of pigmentation along with the loss of germ cells in the gonads, which further verified the critical role of dnd in germline formation (Edvardsen et al. 2014). Remarkably, the dnd mutant fish still formed ovaries and testes but without germ cells, indicating that gonadal differentiation in Atlantic salmon is germ cell-independent (Wargelius et al. 2016; Zhu and Ge 2018). In addition to dnd, germ cell-deficient gonads have also been shown in tilapia through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of nanos C2HC-type zinc fingers (nano2, nano3) (Li et al. 2014). Besides, in tilapia species, disruption of sex-determining genes caused sex reversal. For example, silencing amhy (anti-Mullerian hormone) caused male-to-female sex reversal (Li et al. 2015). Several sex differentiation genes, such as dmrt1 (doublesex and mab-3-related transcription factor 1), sf-1(steroidogenic factor 1), and gsdf (gonadal somatic cell-derived factor), has also been characterized using CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Li et al. 2014; Jiang et al. 2016; Xie et al. 2016). The knockout of sf-1 caused gonadal dysgenesis and feminization of XY in F0 tilapia. In addition to that in XX fish, the disruption of sf-1 resulted in reduced expression of cyp19a1a (cytochrome P450, family 19, subfamily A, polypeptide 1a), foxl2 (forkhead box L2), and serum estradiol-17 while in XY fish the increased expression of the former genes. It is also identified that the treatment 17-methyltestosterone rescued the gonadal differentiation of sf-1-disrupted XY fish while estradiol-17 only incompletely rescued the gonadal differentiation of sf-1- disrupted XX fish. It indicated that sf-1 has a major role in regulating steroidogenesis and reproduction in tilapia (Xie et al. 2016). Similarly, many genes involved in the functioning of spermatogenesis and folliculogenesis have been studied in tilapia (Feng et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2017; Jiang et al. 2017; Yan et al. 2019; Jin et al. 2020; Tao et al. 2020; Zheng et al. 2020). In addition to tilapia, genes related to reproduction and development also have been investigated on other edible fish species, such as olive flounder, sterlet, gibel carp, southern catfish, and yellow catfish (Li et al. 2016; Dan et al. 2018; Baloch et al. 2019; Gan et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2021). Recently, CRISPR/Cas9-based gene knockout was performed in common carp to generate all females by silencing the cyp17a1 gene (Zhai et al. 2022).

Growth and muscle development

Growth has been considered one of the most valuable traits of interest in aquaculture since fish harvest size can be attained quickly via a higher growth rate. Thus, it is possible to speed up and increase productivity and reduce feed costs. Over the years, researchers have investigated several growth-related candidate genes, such as growth hormone gene (GH), insulin-like growth factors (IGF-I & -II), growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), growth hormone inhibiting hormone (GHIH), and myostatin (Mstn) (Gui and Zhu 2012). Recently, growth-associated traits have been studied using the CRISPR/Cas9 tool, focusing on the myostatin (mstn) gene. Myostatin (mstn) is found to be a negative regulator of skeletal muscle mass and belongs to the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily (Lee and McPherron 2001). It regulates myogenin by binding with smad protein and holds the muscle cells in G0/G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle. This would inhibit muscle differentiation and proliferation (Hill et al. 2002). Mutation of the mstn gene produced skeletal muscle enhancement in mammals (Kambadur et al. 1997; McPherron et al. 1997; Lee 2007) and model fish, such as medaka and zebrafish (Chisada et al. 2011; Gao et al. 2016). Therefore, CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been used for mstn knockout in commercial fish species, such as channel catfish, common carp, red sea bream, olive flounder, and blunt snout bream (Zhong et al. 2016; Khalil et al. 2017; Kishimoto et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2019) to increase their growth and muscle development. Khalil et al. 2017 have produced growth-enhanced strains of channel catfish, and the average body weight of knockout fry has increased by 29.7% than the wildtype. Similarly, mstn mutant strain of red sea bream has been generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology with a 16% increase in skeletal muscle mass, and its homozygous breed has been established within two years, far less than the conventional fish breeding approaches. In olive flounder, disruption of mstn showed greater body thickness with significantly reduced expression of mstn mRNA (Kim et al. 2019). In that case, the mutant attained 75.6% editing efficiency, which was higher than displayed by the Atlantic salmon (22–40%) and tilapia (24–50%) (Edvardsen et al. 2014; Li et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2019). Moreover, Zhong et al. 2016 have generated common carp with increased body size and muscles and highlighted that double genome editing is feasible in common carp using CRISPR/Cas9 technology in a single step.

Disease resistance

Fish are sensitive organisms that are highly susceptible to infectious diseases. In the past few years, efforts to manage infectious diseases in fish have concentrated on developing vaccines and producing genetically improved fish lines resistant to particular infections. Despite establishing proper vaccines against many important fish pathogens, the current vaccination method is laborious, costly, and time-consuming (Assefa and Abunna 2018). Traditional selective breeding techniques for developing disease-resistant strains are also time-consuming, and the result is often random and occasionally unsatisfactory due to a lack of the desired phenotype (Dunham and Smitherman 1983).

Invertebrate parasites, both obligatory and opportunistic, can cause parasitic infections in fish. Healthy fish often have small parasite numbers, but water temperature or salinity changes can increase the number of parasites, leading to disease outbreaks. Cultured fish in captivity is vulnerable to various parasites, including protozoa, platyhelminthes, and crustaceans, which can spread disease and cause significant financial losses. Various therapies and preventative measures are used to deal with parasite attacks, but medications and antibiotics can harm the environment and food safety. CRISPR/Cas9 may be an efficient way to create a species-specific insecticide for parasite infestations. Chilodonella piscicola, Cryptocaryon irritans, and C. uncinata are hypothermic parasites that cause gill and skin diseases in freshwater fish (Ferdous et al. 2022). Li et al. 2022a used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to reduce the survival capacity of C. piscicola by destroying its DNA at a specific location using a combination of Cas9 messenger RNA and single-guide RNAs. The chosen sgRNA sequences effectively reduced the survival rate of the experimental C. piscicola to 40% compared to the blank control group. The study demonstrated that Cas9 can act with a single sgRNA or a combination of two sgRNAs to damage the parasite DNA in a specific area (Li et al. 2022a, b). Majeed et al. 2018 also conducted a study to control the Aphanomyces invadans pathogen, a cause of epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS). They used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to edit the A. invadans genome, targeting the serine protease gene in vitro. They also observed the effect on the virulence and pathogenicity of the A. invadans in vivo. They designed three single-guide RNAs (sgRNA) combined with Cas9 to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex and transfected it into A. invadans protoplasts and zoospores. The in vivo results showed that CRISPR/Cas9-treated A. invadans zoospores did not express any signs of EUS in the fish (Majeed et al. 2018).

Recently, Simora et al. (2020) have produced disease-resistant channel catfish through targeted gene integration using the CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in system. The disease resistance was achieved by inserting an exogenous alligator cathelicidin gene into a targeted non-coding region of chromosome 1. Specific gene disruption by the CRISPR/Cas9 system and the introduction of cathelicidin gene into the fish embryo at the single-cell stage enabled a higher HDR rate, precise integration of the transgene construct, and low levels of somatic mosaicism in channel catfish (Simora et al. 2020). Apart from channel catfish, a model carp has also developed through targeted gene editing of TLR22 gene by homologous recombination using CRISPR/Cas9. It is expected that this area of study will develop as a way to improve and understand disease resistance as a fundamental target trait and the development of a highly efficient system for targeted gene integration in other aquaculture fish species. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are membrane glycoproteins with (LRR) domains for binding pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and Toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain (TIR) for signaling to the cytosol, activating the immune system. Model animals with defective target genes, typically knock-out mice, are used to understand immune-related pathways better. Therefore, TLR targeting could improve our understanding of fish immune responses to infections and allow us to build a highly standardized treatment approach (Chakrapani et al. 2016). Chakrapani et al. 2016 utilized the CRISPR/Cas9 method to deactivate the TLR22 gene in the farmed carp rohu L. rohita. The null mutant lacked TLR22 mRNA expression. This would improve the fundamental understanding of the function being done by TLR22 concerning different bacterial and viral infections, including lice infections.

The hemorrhagic disease of grass carp, caused by grass carp reovirus (GCRV), is causing significant economic losses. To control multiple GCRV genotypes, a practical approach is needed. Junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A), an IgSF member, will be a valuable target for developing strategies against GCRV infection (Ma et al. 2018). A study by Ma et al. 2018 employed CRISPR/Cas9 to knock out the grass carp JAM-A gene and tested in vitro resistance against different GCRV genotypes. The results showed JAM-A is necessary for GCRV infection, suggesting potential for aquaculture viral control (Ma et al. 2018).

Furthermore, an efficient technique for disease resistance has been developed as a pooled CRISPR screen called genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (GeCKO) (Shalem et al. 2014; Doench 2018), which is quite a complex system comprised of a collection of tens of thousands of gRNAs designed to target every gene. Once packaged into a lentivirus vector post-synthesis, Cas9 expressing at a low-dose (approximately one gRNA integration/cell) cell line is transduced, which further gets screened (for example, with a pathogen challenge) and selected (using a selectable marker) for sequencing (Gratacap et al. 2019). The ability to add or delete gRNAs demonstrates the potential for gRNA: Cas9 technology to transform functional genomics (Shalem et al. 2014). Implementation of this approach would enable a large-scale genetic screen for understanding the molecular mechanism behind disease resistance, particularly the host cell response to viral infection. Thus, this platform could offer a pressing opportunity to identify the causative genes and allow the introgression of desirable alleles. However, the main challenge to using this platform in farmed fish is the lack of suitable and well-characterized cell lines for most key fish species (Gratacap et al. 2019). The application of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in fish species is at the early stage, and presently, the only farmed fish cell line that is verified to be feasible for the lentivirus-mediated GeCKO approach is the chinook salmon (O.tshawytscha) CHSE cell line (Gratacap et al. 2020). The development of cas9 stable target fishes may allow primary cell lines feasible for editing and generation of immortalized cell lines that would increase the use of the GeCKO system in a wide range of farmed fishes (Gratacap et al. 2019).

Pigmentation

Pigmentation is an important economic trait, and it is assumed that its phenotype may influence consumer acceptance (Colihueque and Araneda 2014). Indeed, genes that regulate pigmentation in fish have been widely targeted in fish species by three genome-editing technologies (ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas9) to ultimately standardize various protocols for phenotype analysis (Zhu and Ge 2018). Several genes, including slc24a5 (solute carrier family 24 member 5), are fundamental genes involved in pigmentation and highly conserved genes among vertebrates (Lamason et al. 2005). Specifically, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing of slc45a2 in Atlantic salmon demonstrated loss of gene function, resulting in various pigment loss across the F0 generation (Edvardsen et al. 2014). Recently, the method has been used to disrupt oculocutaneous albinism II (oca2) gene in cavefish and cichlids (Klaassen et al. 2018; Clark et al. 2022) and ASIP gene in Oujiang color common carp (Chen et al. 2019; Mandal et al. 2020). The findings of the studies revealed that the role played by the genes in melanogenesis in fishes encourages the propagation of fishes with color variation (Klaassen et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2019; Mandal et al. 2020; Clark et al. 2022; Xu et al. 2022). Moreover, research on pigmentation traits has significance for biosafety as the different pigmentation patterns can be used to recognize escaped mutant fishes (Edvardsen et al. 2014; Wargelius et al. 2016; Guralp et al. 2020; Straume et al. 2021).

Omega-3-fatty acid metabolism and other traits

Fish oil omega-3 long-chain (C20) polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LC-PUFAs), especially EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid, 20:5n-3) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid, 22:6n-3), have been shown to have beneficial effects on human health. Dietary supplementation remains the best option to fulfill the requirements for LC-PUFA, as humans have a limited capacity for their endogenous production. Cultured fish have lower levels of n-3 LC-PUFAs than wild fish, particularly those given diets that substitute vegetable oils for fish oil and meal, which are becoming increasingly scarce. The primary sources of omega-3 LC-PUFAs for the human diet are fish, especially Atlantic salmon, which can synthesize polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) through the activities of fatty acyl elongases (Elovls) and fatty acyl desaturases (Fads). It would be beneficial to understand the molecular mechanisms of PUFA biosynthesis and control (Datsomor et al. 2019a, b). Datsomor et al. 2019a, b employed CRISPR/Cas9 to knock out the elovl2 gene partially and showed that enzyme is required for multi-tissue synthesis of 22:6n-3 in vivo and that endogenously synthesized PUFAs are required for transcriptional control of lipogenic genes. The elovl2-knockout fish had lower amounts of 22:6n-3 and higher levels of 20:5n-3 and docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-3) in the liver, brain, and white muscle, indicating that elongation was inhibited.

Furthermore, elovl2-knockout salmon accumulated arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) in the brain and white muscles. The decrease in 22:6n-3 production increased the hepatic expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (srebp-1), fatty acid synthase-b, Δ6fad-a, Δ5fad, and elovl5. Thus, the study indicated that elovl2 plays an essential role in the two final phases of PUFA synthesis in vivo and suggested that Srebp-1 is a critical regulator of endogenous PUFA synthesis in Atlantic salmon. This finding could leads to less need for live feed and/or fish oil in the feed, which would be of economic and ecological benefit (Datsomor et al. 2019a, b).

Current CRISPR/Cas9 delivery strategies

Currently, three methods are used to carry out CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in farmed fish. The first and easiest method is to employ a CRISPR/Cas9 system based on a plasmid that encodes both the Cas9 protein and the sgRNA from the same vector, preventing the need for multiple transfections of various components. Delivering a combination of sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA is the second tactic. The third approach is to deliver a mixture of the Cas9 protein and sgRNA (Liu et al. 2017).

The first method, the plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system, is straightforward, affordable, and controlled by avoiding multiple transfections of undesired targets (Ran et al. 2013b). Also, the plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system is considered as the most stable approach compared to the second approach mentioned above (i.e., Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA system). The plasmid approach to delivering CRISPR cargo is similar to the older viral-based delivery mechanism, but the complications that can arise from introducing viral particles into a cell are eliminated. Thus, despite its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, the plasmid approach in both in vivo and in vitro has remained challenging due to the lack of accessibility of appropriate vectors that use active promoters to trigger the efficient expression of both sgRNA and Cas9 protein within a single expression system in edible fish species (Liu et al. 2017; Escobar-Aguirre et al. 2019). Recently, Hamar and Kultz et al. 2021 have developed a vector system for the disruption of nanos3 with the insertion of endogenous tilapia EF1 alpha (OmEF1a) and tilapia U6 (TU6) promoters for the expression of cas9 and sgRNA in OmB cells of tilapia. Thus, it could evade the prerequisite for time-consuming in vitro transcription of gRNA and Cas9 or obtaining costly synthetic RNA or Cas9 protein.

Similarly, Kim et al. 2021 have also adopted a plasmid-based approach for the knockout of the Pomaf1 gene by the introduction of sgRNA/Cas9 dual expression vector pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP after cloning of specific gRNA into HINAE olive flounder embryonic cells. They have successfully developed single-cell-derived PoMaf1 knock-out cells using this approach. In addition to these, this strategy has been used in grass carp (C. idella) and chinook salmon (O. tshawytscha) (Dehler et al. 2016, 2019; Ma et al. 2018; Gratacap et al. 2020). However, delivering plasmid into nucleus and subsequent translation of Cas9 inside the cells, the overall plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system requires more time. Moreover, because it avoids multiple transfections of undesired targets, it also means that the plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system generates relatively high off-target effects and strong immune responses via the constitutive expression of the Cas9 protein (Liu et al. 2017; Hamar and Kultz et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2021). The possible way to reduce off-target effect in this approach is to target multiple sequences on the same gene if a reliable phenotype is detected. Furthermore, plasmid DNA poses a risk of insertional mutagenesis (Yip 2020).

Unlike the first approach based on a plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system, the direct transfer of Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA into a fertilized egg is capable of inducing mutation at the target site through the expression of the Cas9 mRNA and formation of the sgRNA/Cas9 complex. The advantages of using Cas9 mRNA form are the reduced duration of gene-editing via transient expression and reduced off-target effects compared to the plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9 system (Liu et al. 2017). Most previous CRISPR studies in farmed fish were based on the independent use of sgRNA and spCas9 (Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) (Edvardsen et al. 2014; Li et al. 2014; Wargelius et al. 2016; Xie et al. 2016; Baloch et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2018; Datsomor et al. 2019a, b; Liu et al. 2020; Straume et al. 2020; Tao et al. 2020; Straume et al. 2021). However, due to the low stability of the CRISPR components, there are still challenges remaining to apply this approach in fish models and further elucidation on co-delivery and co-expression of the CRISPR components is required (Liu et al. 2017).

The joint transfer of the Cas9 protein and sgRNA into the target cell is the approach most widely studied in recent years, particularly in channel catfish (Khalil et al. 2017; Elaswad et al. 2018a, b; Simora et al. 2020), rainbow trout (Cleveland et al. 2018), and blunt snout sea bream (sun et al. 2020). Purified recombinant Cas9 protein forms complexes with in vitro-transcribed sgRNA, called Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs); upon the RNPs transfection into cells/fish eggs, subsequent induction of small mutations (insertions/deletion) at target loci occurs, which then undergo rapid degradation to reduce off-target effects, toxicity, immune responses, and mosaicism (Kim et al. 2014; Khalil et al. 2017; Cleveland et al. 2018; Elaswad et al. 2018a, b; Simora et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020; Segev-Hadar et al. 2021; Xu et al. 2022; Zhai et al. 2022). Furthermore, this system does not need codon optimization or promoter selection. However, this approach is not economical compared to other methods (Kim et al. 2014).

Methods for delivering genome editing tools in vitro and in vivo

An essential step in any CRISPR-based experiment is delivering the gRNA and Cas9 into the cytoplasm or nucleus of the target cells. Multiple methods have been developed to introduce the desired nucleic acid into cells while maintaining cell viability. The methods can be categorized as physical, chemical, and viral (Lino et al. 2018).

Several chemically based methods can transport genome editing cargo into cells, including calcium phosphate, cationic amino acids, and cationic polymers (Lino et al. 2018). One of the most commonly used methods is lipofection, which introduces CRISPR components into cells using cationic lipid reagents to make lipid-soluble structures, named liposomes, around the CRISPR components. The components are then transported into the cell through endocytosis, and they diffuse through the cytoplasm by skipping the endocytosis pathway and enabling targeted editing (Lino et al. 2018). Nevertheless, chemical-based transfection is primarily limited to in vitro studies, and it has been applied on a few fish cell lines of grass carp, chinook salmon, and olive flounder (Dehler et al. 2016, 2019; Ma et al. 2018; Gratacap et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2021).

A thick acellular and multilayered coat surrounds fertilized fish eggs called chorion that can act as a cellular barrier to transferring CRISPR components (Goto et al. 2019). The physical techniques of microinjection and electroporation of DNA or RNA into newly fertilized eggs have been recognized as the most consistent gene transfer methods in egg-laying fish (Chen and Powers 1990). In microinjection, Cas9 and sgRNAs are injected into a fertilized egg using a microscope and a needle. Because the needle pierces through the chorion membrane to directly deliver the foreign material into the nucleus or cytoplasm, the molecular weight of Cas9, which is a concern in viral vector-mediated delivery, is not a hurdle in microinjection (Wang et al. 2017). Moreover, manual injection enables controlled dosing of the CRISPR components into the egg (Lino et al. 2018). Most CRISPR/Cas9 studies conducted in fish have used microinjection to introduce the gene editing tools into fertilized fish eggs (Edvardsen et al. 2014; Li et al. 2014; Feng et al. 2015; Wargelius et al. 2016; Xie et al. 2016; Jiang et al. 2017; Khalil et al. 2017; Cleveland et al. 2018; Elaswad et al. 2018a, b; Datsomor et al. 2019a, b; Simora et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2021). Also, due to the diverse characteristics of fish eggs, many technical problems must be addressed to practice successful microinjection.

Depending on the yolk distribution, fish eggs can be categorized into two types: one with a single yolk sac and one with multiple yolk granules. In the first case, cytoplasm passes towards animal pole on the exterior of yolk to form blastodisc, while in the second case, cytoplasm passes between yolk granules to animal pole. In eggs with a single-yolk sac, the injection should be done directly into blastodisc because molecules cannot pass across yolk cytoplasm boundary. But, in eggs with multiple yolk granules, injection could be done directly into blastodisc or yolk area (Goto et al. 2019). Recently Khalil et al. 2017 emphasized that in channel catfish, injection of CRISPR reagents into yolk rather than embryo cell is adequate to knock out the genome efficiently. This approach could reduce time and energy dedicated to microinjection and result in less disruption to the embryo, facilitating high mutation and survival rates. In contradiction to this case, in olive flounder, the injection of reagents into cytosol and yolk syncytial layer (YSL) caused cytoplasmic diffusion of the reagents, and injection into yolk triggered sudden embryonic death (Kim et al. 2019). Hence, egg features decide the injection location and, ultimately, the success of microinjection.

Furthermore, in several species, it was found that egg chorion slowly hardens after fertilization. So, it is suggested that either microinjection before hardening the chorion or the chorion can be softened or removed by the proteolytic enzyme (Goto et al. 2019; Kishimoto et al. 2019). In the case of Atlantic salmon, the eggs have been treated with a reduced L-glutathione solution to avoid chorion hardening (Guralp et al. 2020). In general, a custom-made method (such as needle preparation, injection dosage, and treatment of fertilized egg) has to be developed for each target species based on the peculiarities of the fish egg, and more research is required on another delivery method, such as electroporation to achieve reliable results.

Electroporation is a physical delivery method that uses pulses of electrical currents to stimulate the transitory opening of pores in fertilized egg membranes, enabling the transport of CRISPR elements into the egg. The technical challenge associated with electroporation is the presence of a tough chorion layer surrounding fertilized fish eggs, which reduces the efficiency of this method. However, while removing the chorion layer can enhance its efficiency, removal of the chorion layer either physically or chemically could cause stress to the eggs. Despite such pros and cons, electroporation is still one of the most widely used methods in fish because it can deliver genes to many fertilized eggs in a short time. The Beakon 2000 (Baekon Co.), Cell Porator (Gibco-BRL), square wave generator (BTX), and a handheld electrode linked to the BTX square wave generator are commercially available electroporators that can be used efficiently in gene delivery studies in fish (Chen and Chen 2020). Recently this method has been adopted by Wang et al. 2021 for the effective transfer of CRISPR/Cas9 components into olive flounder eggs since it is difficult to introduce the CRISPR reagents into pelagic and telolecithal eggs with hard egg chorion via delivery methods such as microinjection and this could lead to genome editing on a large scale in olive flounder.

Challenges in CRISPR/Cas9-based genetic improvements

Even though CRISPR/Cas9 technology has shown great potential for precise, rapid, and targeted gene editing, producing gene-edited fish involves several challenges, particularly if it is to be used in vivo. Off-target effects, gene duplication events, and mosaicism must be addressed (Edvardsen et al. 2014; Cleveland et al. 2018; Elaswad et al. 2018a, b; Datsomor et al. 2019a, b).

Off-target effects

Off-target effects remain a major challenge since they can lead to non-targeted editing of the fish genome, which could have unexpected consequences, such as embryonic malformation and even fish population mortality (Elaswad et al. 2018a). After the introduction of the cathelicidin gene for disease resistance, it was found that the high mutation rate caused by CRISPR/Cas9 technology had reduced the embryo survival rate in channel catfish, and it became unclear whether this was due to pleiotropic or off-target effects (Simora et al. 2020). Since the change in the number and position of nucleotides is unclear, it is challenging to pinpoint the off-target mutation (Agapito-Tenfen et al. 2018). However, some strategies can eliminate the off-target effects. The precise design of sgRNA using readily available bioinformatics tools and retrieval of data on the genomic sequences of fish species is the main strategy to reduce the off-target effect (Koo et al. 2015; Elaswad et al. 2018a). Before attempting in vivo genome editing, in vitro investigations can use CRISPR components in cell lines from the potential fish species to rapidly recognize highly specific gRNAs. Another effective tactic is to alternate the S. pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) enzyme with a mutant nSpCas9 that causes a single-strand break at the target area. When using mutant nSpCas9, a pair of sgRNAs must be created so that one Cas9 will bind to the sense strand and the other to the antisense strand, flanking the target area to get the desired results. The DSBs formed in this way occur only when the two Cas9 proteins bind in that specific configuration and produce cooperative nicks, reducing off-target effects and doubling the target recognition sequence (Ran et al. 2013a). Optimizing the concentration of gRNA/cas9 protein and the use of short half-life cas9 also will reduce the off-target effects (Elaswad et al. 2018a). Even if the off-target is detected in the offspring, it will likely be eradicated by creating sufficient progenies and selection. The selection can be done via post-editing screening for unexpected mutation. There are several methods available that could be applied to detect off-target effects, including whole genome/exome sequencing, in vitro nuclease-digested genome sequencing, and GUIDE-seq (Koo et al. 2015) after post-editing to ensure the absence of off-target effects in the gene-edited fish.

Gene duplication

When considering teleosts for genome editing, whole genome duplication is an additional challenge that results in an extra set of genes in particular fish species (Tong et al. 2021). The number of chromosomes, ploidy level, and functions of duplicated genes may vary in different species due to multiple rounds of duplication process. The duplicated gene can either share the function of original gene or, allocate a new function or lose the function (Glasauer and Neuhauss 2014). In this situation, the function and sequence of the duplicated genes should be investigated to choose whether all the paralogous genes should be targeted for the desired phenotype. Some studies highlighted that CRISPR/Cas9 technology is amenable to multiplexing, and it is a convenient method for disrupting paralogous genes at a time and assessing the function of duplicated genes (Cleveland et al. 2018; Datsomor et al. 2019a, b). Cleveland et al. 2018 emphasize that both paralogs of the IGFBP-2b gene, such as IGFBP-2b1 and IGFBP-2b2, need to be co-targeted since one gene of the paralogs may carry on the desired function of the gene and eliminate the effect of targeted disruption. Sometimes, a single paralog gene knockout is sufficient for the desired outcome (Chen et al. 2017; Kishimoto et al. 2018). In that situation, the issue could be resolved by comparing genes with different copies in the genome (Cleveland et al. 2018; Datsomor et al. 2019a, b).

Mosaicism