Abstract

In this study, we have stated the green biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) by utilizing the extract of Monstera deliciosa leaves (MDL) as a reducing agent. Biosynthesized flat, thin, and single-crystalline gold nanotriangles obtained through centrifugation are then analyzed by different characterization techniques. The UV − visible absorption spectra of AuNPs exhibited maxima bands in the range of 500–590 nm, indicating a characteristic of AuNPs. XRD analysis revealed the formation of the (111)-oriented face-centered cubic (FCC) phase of AuNPs. ATR-IR spectra showed signatures of stretching vibrations of O–H, C-H, C=C, C=O, C–O, and C-N, accompanied by CH3 rocking vibrations present in functional groups of biomolecules. FESEM images confirmed spherical nanoparticles with an average diameter in the range of 53–66 nm and predominantly triangular morphology of synthesized AuNPs within the size range of 420–800 nm. NMR, GC–MS, and HR–MS studies showed the presence of different biomolecules, including phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidants in MDL extracts, which play a crucial role of both, reducing as well as stabilizing and capping agents to form stable AuNPs by a bottom-up approach. They were then investigated for their antibacterial assay against Gram-positive (S. aureus, B. subtilis) and Gram-negative (E. coli, P. aeruginosa) microorganisms, along with testing of antifungal potential against various fungi (Penicillium sp., Aspergillus flavus, Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani) using the well diffusion method. Here, biosynthesized AuNPs showed non-antimicrobial properties against all four used bacteria and fungi, showing their suitability as a contender for biomedical applications in drug delivery ascribed to their inert and biocompatible nature.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03898-0.

Keywords: Gold nanoparticles, Biosynthesis, Non-antimicrobial, Biocompatible

Introduction

Nanotechnology has developed to be highly reassuring in the realm of science over the past few decades due to its significant development in a variety of scientific and technological fields (Ankamwar and Gharpure 2020). Nanoparticles exist on a nanometer scale and have peculiar physicochemical properties that are different from their respective bulkier counterparts. They pose distinctive characteristic properties like a high surface-to-volume ratio, enhanced biocompatible nature, and catalytic potential (Doan et al. 2020; Sk et al. 2020). They are extensively used in diverse fields, including environment, biology, optoelectronics, cosmetics, imaging, automobiles, the food industry, pharmaceuticals, textiles, construction, electronics, sensing, catalysis, etc. Nanoparticles are largely classified into different categories based on their structure, origin, and dimension, which further group them into carbon-based or metal-based nanoparticles. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have notably dominated the field of metal-based nanoparticles since the nineteenth century. This is exactly when Michael Faraday first reported the captivating optical properties of nanogold in his publication (Faraday 1857).

AuNPs are mostly used in biomedical applications due to their distinguishing characteristics like small size, high dispersity, controllable surface chemistry, stability, low toxicity, appropriate surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band, tunable optical absorption and scattering, along with having an inert and highly biocompatible nature (Pechyen et al. 2021). By drawing our attention to the increased specificity of nanoparticles in target drug delivery along with their easy disposal system, they can be proven to be excellent drug carriers (Arvizo et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2021). Decreased cytotoxicity along with increased biocompatibility and therapeutic value can be achieved by efficiently exploiting nanoparticles in drug delivery systems (De Jong and Borm 2008). This can be done in two pathways, which include nanoparticles acting as stable carriers for drug loading and functionalizing independently in detection, diagnosis, and therapy treatments with an active agent used for biomedical purposes (LaVan et al. 2003; Ankamwar and Gharpure 2019). The physiochemical properties of metal nanoparticles highly depend on their shape and size as well. S. Phukan et al. biosynthesized AuNPs using A. assamica leaf extract and lucidly explained the impact of varying concentrations of biological extract and metal ions on the morphology of AuNPs (Phukan et al. 2016). Concentration, pH, light sources, reaction time, and temperature are all factors that contribute to the morphology and stability of biosynthesized AuNPs (Krishnamoorthi et al. 2021). The most distinctive property of AuNPs is the degree to which their optical properties can be altered by tailoring their morphology and their assemblage. If there is a change in the morphology of nanoparticles, a shift in the optical extinction band is seen from the visible to the near infrared region. AuNPs having different shapes like nanospheres, nanowires, nanorods, nanocages, nanotubes, nanoprisms, etc. are already synthesized, having a size range between 1 and 100 nm. These morphological changes show a considerable effect on the properties of nanoparticles (Shankar et al. 2004). Nanoparticles having a polydisperse nature cause difficulties in self-assembly, which have a huge impact on their overall characteristics, including the morphological properties of individual nanoparticles. Therefore, polydispersity should be reduced to synthesize nanoparticles retaining well-defined properties. Many reports have been published associated with the use of various chemical, physical, and biological techniques in the fabrication of AuNPs. Several wet chemical methods used for nanoparticle synthesis yield polydisperse nanoparticles with undesired morphologies (Ankamwar et al. 2017). Also, highly effective purification and separation techniques come in need that can be expensive and barely applicable. Biological methods are more stable, clean, biocompatible, cost-effective, fast, convenient, and simple as compared to physical and chemical methods that require specific instrumentation, a high budget, and use harmful chemicals that generate toxic waste (Abdoli et al. 2021; Arief et al. 2020). Biosynthesis of AuNPs makes use of naturally available biological sources like plant and animal-based products, viruses, algae, bacteria, and fungi, as well as biomacromolecules, for the bio-reduction of gold precursors (Roy et al. 2022; Amina et al. 2020). Synthesis of nanoparticles using plants could be beneficial over any other environment-friendly biological processes since they do not include any intricate processes like preserving and heeding cell cultures (Khan et al. 2022). Plant-mediated synthesis methods are biological “nanofactories” that prove to be a promising option (Ankamwar et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2021). Using this eco-friendly, safe, renewable, scalable, easily adaptable, and stable method is the need of the hour. A vast list of plant parts such as Lemongrass (Shankar et al. 2004), Woman’s tongue tree white flower (Ankamwar and Gharpure 2019), Piper betle leaves (Ankamwar et al. 2016), Ginger root (Yadi et al. 2022), Argemone mexicana L. (Téllez-de-Jesús et al. 2021), Mangifera indica seed (Donga et al. 2020), Sargassum plagiophyllum (Dhas et al. 2020), Croton sparsiflorus leaves extract (Boomi et al. 2020), Barley leaves (Xue et al. 2021), Parsley leaves (El-Borady et al. 2020), Flammulina velutipes (Rabeea et al. 2020), Jasminum auriculatum leaf (Balasubramanian et al. 2020), Lactuca indica leaf (Vo et al. 2020), Crassocephalum rubens (Adewale et al. 2020), Scutellaria baicalensis roots (Chen et al. 2020), Passiflora edulis peels (My-Thao Nguyen et al. 2021), Crataegus monogyna leaf (Shirzadi-Ahodashti et al. 2020), Codonopsis pilosula roots (Doan et al. 2020), Sargassum horneri extract (Song et al. 2022), Ananas comosus and Passiflora edulis (Pechyen et al. 2021), Acacia auriculiformis leaves (Parveen et al. 2022), Sageretia thea leaf (Shah et al. 2022), Prunus cerasifera pissardii nigra leaf (Hatipoğlu 2021), Vitex negundo leaf (Sunayana et al. 2020), Cinnamon bark extract (ElMitwalli et al. 2020), Rosa canina L. (Cardoso-Avila et al. 2021), Pimenta dioica (Kharey et al. 2020), Tecoma capensis (L.) (Hosny et al. 2022), Hygrophila spinosa T. Anders (Satpathy et al. 2020), Malva verticillata leaves (Sk et al. 2020) etc. are reported for biosynthesis of AuNPs having various applications. Plant extract contains biomolecules such as terpenoids, vitamins, steroids, polysaccharides, flavonoids, phenolics, tannins, alkaloids, saponins, amino acids, esters, proteins etc. that form morphologically controlled nanoparticles by working as a reducing and stabilizing agent (Cyril et al. 2020).

Monstera deliciosa is a member of the kingdom Plantae and Araceae family belonging to the flowering plant species having aerial roots (Peters and Lee 1977). It falls under species M. deliciosa and genus Monstera and is a secondary hemiepiphyte, growing in the wild up to 20 m high. Monstera deliciosa bear leaves having indoor heights of only 2–3 m high, whereas they are 25–90 cm and 25–75 cm long and broad, respectively. The name is derived from the Latin word ‘monstrous’ meaning abnormal, as it bears leaves with unusual natural holes and gaps. Leaves are large, pinnate, heart-shaped, and develop holes or gaps as they grow older (Fig. 1). Monstera deliciosa is widely found in many tropical areas and is native to the humid rainforests of extreme South Mexico. This climbing rainforest vine is mostly grown as an ornamental plant near a tree for support. It also efficiently self-pollinates and usually creeps up on a tree, growing towards sunlight. Monstera deliciosa is an evergreen perennial vine compatibly grown in temperate zones, having a popular indoor houseplant name as “Cheese or Swiss Cheese plant”, resembling the gaps in its leaves to the holes of any Swiss cheese. Other common names are split-leaf philodendron, delicious monster, fruit salad plant or tree, ceriman, zampa di leone, monster fruit, monstereo, Mexican breadfruit, balazo, window leaf, foliage house plant, and Penglai banana. It has many uses, from using its aerial roots to make ropes and baskets to proving an efficient remedy for snake bites and relief from symptoms of arthritis. A qualitative study of M. deliciosa extracts recorded the presence of fundamental phytochemicals such as tannins, polyphenols, steroids, flavonoids, alkaloids and saponins of which possess medical importance by showing potential antibacterial, antidiuretic, anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, antianalgesic, anticancer, anti-viral, and antioxidant activities (Rao et al. 2015). Since the leaves of M. deliciosa contain different phytochemicals and bioactivities, their extract can be efficiently used for the biosynthesis of AuNPs which has several bio-applications.

Fig. 1.

Photograph of Monstera deliciosa leaf

So here, in this study, we have reported eco-friendly biosynthesized anisotropic AuNPs by using an aqueous extract of Monstera deliciosa leaves and separating them at a speed of 500 rpm for 10 min and again the decanted supernatant was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min, further followed by its characterization. Additionally, the as-synthesized AuNPs were estimated for their anti-microbial potential using various bacteria (E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, B. subtilis) and fungi (Penicillium sp., Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus flavus, Rhizoctonia solani) as an indispensable check for their biocompatibility.

Methods and materials

Materials used

Fresh green leaves of the Monstera deliciosa plant are used in the preparation of leaf extract. Chloroauric Acid i.e., Gold (III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl4⋅3H2O), 99.0% was procured from Himedia, India. Microbial cultures were cultured using Nutrient broth and Sabouraud’s dextrose broth for growing fungal cultures. The antimicrobial activity was evaluated using nutrient agar and Sabouraud’s dextrose agar purchased from Himedia, India. All the used chemicals were utilized directly without any sort of further purification. Also, all experimental procedures were carried out using MilliQ water.

Preparation of Monstera deliciosa leaf extract

Leaves of Monstera deliciosa (MD) were weighed and cleaned thoroughly with double-distilled water to take off all the dirt, which was then again washed with MilliQ water 2–3 times. 50 g of leaves were cut into small pieces and added to an Erlenmeyer flask containing 250 ml of water. Two sets of each such Erlenmeyer flask were prepared, of which one was subjected to 5 min of heating and the other was heated in a hot bath of boiling water for 10 min. It was next permitted to completely cool down to room temperature. Extract consumed for bioreduction of Au3+ ions was obtained by filtering the cooled extract using an eight-folded muslin cloth to remove any leaf matter, followed by centrifuging the extract at 2500 rpm for 10 min to get a debris-free, clear supernatant of leaf extract.

Biosynthesis of AuNPs

From each set, 20 mL of MD extract was mixed with 100 mL of 1 mM HAuCl4 solution. These solutions were kept undisturbed for 22 h at room temperature. The formation of AuNPs was indicated by a change in color from the initial yellowish solution to the final cherry red color. The so-formed AuNPs using the extract from both sets (5 min and 10 min heated) are then centrifuged at a speed of 500 rpm for 10 min. The decanted supernatant was again centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The pellets collected through centrifugation were then subjected to 2–3 washes of MilliQ water. The obtained pellet is then stored for further characterization and possible applications.

Characterization techniques

UV–visible double-beam spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800, 240 V) varying between 200 and 1100 nm was used to analyze the optical properties of AuNPs prepared by utilizing MD leaf extract. X-ray diffraction (XRD) study of AuNPs was carried out using an X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Ultima-IV) operating at room temperature, with 2θ values ranging between 5° and 80°. It uses a scanning speed of 0.005 s−1 and CuKα radiation at a wavelength of 1.54056 Å. AuNPs were further analyzed for their respective morphologies using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) with the help of the model JEOL JSM-6360A, which possesses an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Attenuated Total Reflectance Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-IR) of so-synthesized AuNPs, MD leaf extract, and Chloroauric Acid (HAuCl4) used as gold precursor salt was obtained using a Bruker Platinum ATR Tensor 37 spectrophotometer, ranging from 4000 and 500 cm−1 and operating at a resolution of 4 cm−1. The plausible molecule was detected through Gas Chromatography − Mass Spectrometry (GC − MS) by using methanolic MD extract. It was performed with the help of Shimadzu, GC 2010 Plus, having a column oven temp of 80 °C and injection temp of 260 °C in split mode. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) analysis of MD extract was done using the solvents deuterium oxide (D2O) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) by Bruker Ascend 400 MHz. High Resolution − Mass Spectrometry (HR-MS) analysis was done by directly injecting aliquots of aqueous MD extract in an ESI chamber, which were recorded by a Bruker impact HD Q-TOF spectrometer.

Microorganisms

Microorganisms including Gram-positive (S. aureus, B. subtilis) as well as Gram-negative (E. coli, P. aeruginosa) bacteria were obtained from the Microbiology Department, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, India. These were used for antimicrobial assays. To maintain the viability of bacterial cells, they were subcultured every two weeks periodically by streaking them on nutrient agar slants and preserving them at 4 °C. Fungal cultures such as Penicillium expansum, Aspergillus flavus, Fusarium oxysporum and Rhizoctonia solani were acquired from the Botany Department, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, India. The viability of fungal cells was maintained by periodic subculturings of fungal spore suspension on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar slants.

Estimation of antibacterial assay

Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria were used for estimating the antibacterial potential of AuNPs. Microorganisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis, were chosen as Gram-positive bacteria, whereas Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were chosen as Gram-negative bacteria. These microorganisms were utilized for analyzing the antibacterial activity of AuNPs. AuNPs were synthesized using MD leaf extract, and the resulting nanoparticles were collected at different centrifugation speeds. The well diffusion method was used for different concentrations of AuNPs in the range of 2.5–10 mg/mL. A single bacterial colony was inoculated in 5 mL of nutrient broth and was then allowed to be grown overnight at 37 °C. This was done with constant stirring in a shaker incubator at a speed of 120 rpm for 4 h. The main culture's inoculum was utilized to re-inoculate in 10 mL of nutrient broth, and it was grown at 37 °C and 150 rpm until it reached 0.5 McFarland's Standard. Physiological saline was used to further dilute the broth containing bacterial cells until it reached a final concentration of 105 CFU/mL. A glass spreader was used to spread 100 µL of bacterial cultures across a nutrient agar petri plate. Then, to make wells, nutrient agar petri plates were poked open using a corkborer that had a 5 mm diameter. The two sets of produced AuNPs were dispersed in Milli-Q water, which performs the role of solvent. 50 µL suspension of synthesized AuNPs at three different concentrations (2.5 mg/mL, 5 mg/mL, 10 mg/mL) was added into the punctured wells by sonicating. To ensure optimal diffusion, they were subsequently incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Zones of inhibition were recorded after overnight incubating for 20 h in nutrient agar petri plates at 37 °C.

Estimation of antifungal assay

Various fungal cultures (Penicillium expansum, Fusarium solani, Rhizoctonia solani, Fusarium oxysporum) were utilized to estimate the antifungal activity of MD-mediated biosynthesized AuNPs. 10 mg/mL concentration of nanoparticles was used in the well diffusion method. A completely sterile blade was utilized to cut a 1 mm square of fungal inoculum from a fungal culture that contains Sabouraud’s dextrose agar. It was next moved in a fresh Sabouraud’s dextrose agar petri plate and grown at 30 °C. To release all the fungal spores, 1 ml of physiological saline was added to the tweezed freshly grown fungal culture. A Haemocytometer was used to count the total number of fungal spores. The final concentration of 104–105 CFU/mL was achieved by diluting the fungal spore suspension with physiological saline. A glass spreader was used to spread 100 µL cultures of fungal spore suspension on a petri plate containing fresh Sabouraud’s dextrose agar. Sabouraud’s dextrose agar plates were then bored to form wells using a cork borer that had a 5 mm diameter. The two sets of produced AuNPs were dispersed in Milli-Q water. 50 µL suspensions of synthesized AuNPs at three different concentrations (2.5 mg/mL, 5 mg/mL, 10 mg/mL) were added into punctured wells by sonicating. They were further incubated for half an hour at room temperature to enable proper diffusion. Sabouraud's dextrose agar petri plates containing fungal cultures containing AuNPs were incubated at 30 °C for 7 days, and zones of inhibition were measured.

Results and discussions

Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles

MD leaf was extracted in two sets with different heating periods, i.e., 5 and 10 min. This extract was then used for the biosynthesis of AuNPs by utilizing 0.001 M Chloroauric acid as a gold precursor salt. In addition to MD leaf extract to the precursor salt, a change in color was observed from yellow to cherry red indicating the formation of AuNPs. This color change is due to the presence of several biomolecules present in the extract, which change the oxidation state of gold ions, as published in the reports of many literature surveys (Donga et al. 2020; ElMitwalli et al. 2020; Xue et al. 2021; Huai et al. 2021; Parveen et al. 2022). The biomolecules present in MD extract play the role of both a reducing and stabilizing agent in the bioreduction of Au3+ ions to form AuNPs. These nanoparticles were further characterized with the help of UV–vis spectrometry, XRD, ATR-IR, FESEM, GC–MS, HR-MS, and NMR analysis.

Characterization of AuNPs

UV–visible spectroscopic analysis

UV − visible spectroscopic analysis is an efficient technique used to observe the optical properties of nanoparticles. The spectra are recorded in the range of wavelength 200 − 1100 nm for biosynthesized AuNPs. Figure 2 represents the UV–visible-NIR spectra of AuNPs obtained from MD leaf extract. The reduction of Au3+ ions to zerovalent AuNPs is verified by UV–vis-NIR spectral signatures since the interaction of visible light with the free electrons gives a pink-ruby-red color by excitation of SPR (Mulvaney 1996; Kumari and Meena 2020). The range of SPR bands depends on various factors, including particle nature, distance between two particles, reaction conditions and morphological aspects of nanoparticles (Ankamwar et al. 2016). AuNPs showed absorbance bands around 500 to 590 nm for AuNPs(A) and AuNPs(B) whereas AuNPs(C) and AuNPs(D) showed absorption maxima around 544 nm indicating less variation. The results confirm the formation of AuNPs since a maxima band was obtained around 540 nm (Mai et al. 2021). MD extract showed an absorption maximum at 282 nm. It denotes the presence of phenols, flavonoids, and glycosides since they absorb UV window light, as indicated in the literature analysis (Kharey et al. 2020). This weak band can also be from the n → π* electronic transition of phytochemicals that are present in plant extract (Tripathy et al. 2020). Thus, phytochemicals aid the biosynthesis of AuNPs by reducing precursor salts.

Fig. 2.

A Illustrates UV–vis-NIR absorption spectra recorded from Monstera deliciosa leaf extract (curve 4), Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min [AuNPs(A)] (curve 3), Original aqueous gold nanoparticles solution containing AuNPs(A) (curve 2), 1 mM gold chloride solution (curve 1); B Illustrates UV–vis-NIR absorption spectra recorded from Monstera deliciosa leaf extract (curve 4), Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min [AuNPs(B)] (curve 3), original aqueous gold nanoparticles solution containing AuNPs(B) (curve 2), 1 mM gold chloride solution (curve 1); C Illustrates UV–vis-NIR absorption spectra recorded from Monstera deliciosa leaf extract (curve 4), Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min [AuNPs(C)] (curve 3), original aqueous gold nanoparticles solution containing AuNPs(C) (curve 2), 1 mM gold chloride solution (curve 1) and D Illustrates UV–vis-NIR absorption spectra recorded from Monstera deliciosa leaf extract (curve 4), Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min [AuNPs(D)] (curve 3), original aqueous gold nanoparticles solution containing AuNPs(D) (curve 2), 1 mM gold chloride solution (curve 1)

Considering Fig. 2A, B, an increase in maximum absorption wavelength, i.e., a red shift in the absorption peak, is observed, possibly indicating an increase in the size of nanoparticles, mainly due to aggregation or settling of isotropic structures at high centrifugation speed (Amendola and Meneghetti 2009). The peak at 588 nm represents the transverse mode of the surface plasmon, which corresponds to spherical, i.e., isotropic-structured AuNPs. Thus, it signifies that one can alter the morphology of biosynthesized gold nanoparticles by separating and purifying them at different speeds of centrifugation (Ankamwar et al. 2017). In the case of anisotropic structures, the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) peak splits into longitudinal (long axis) and transverse (short axis) modes. When the excitation occurs along the shorter axis with absorption in the visible region, a transverse SPR band is obtained. On the other hand, a much stronger and more sensitive absorption band along the longer axis gives rise to a longitudinal SPR band. In Fig. 2A for AuNPs(A), absorption at longer wavelengths can be seen by a progressive increase in the region of the near-infrared spectrum. Anisotropic nature or aggregation of spherical AuNPs usually results in large near-infrared absorption by the particles. In the NIR absorption region for AuNPs, a longitudinal absorption peak is observed indicating the presence of anisotropic structures like nanowires, nanorods, nanocages, nanotubes, nanoprisms, etc. In our case, the particles formed are apparently anisotropic, having a triangular and hexagonal shape, as seen in the FESEM pictures (Fig. 3). Boomi et al. stated that the absorption maxima of AuNPs varies between 532 and 541 nm (Boomi et al. 2020). In another biosynthesis, the successful formation of AuNPs showed an absorption maximum at 542 nm (Ningaraju et al. 2021). S. Satpathy et al. biosynthesized AuNPs using a very small amount of Hygrophila spinosa T. Anders extract, which showed the desired ruby red color and characteristic SPR peak in the range of 520–560 nm (Satpathy et al. 2020). So, an absorption maximum shown around ∼540 nm is a characteristic of AuNPs and thus validating its synthesis.

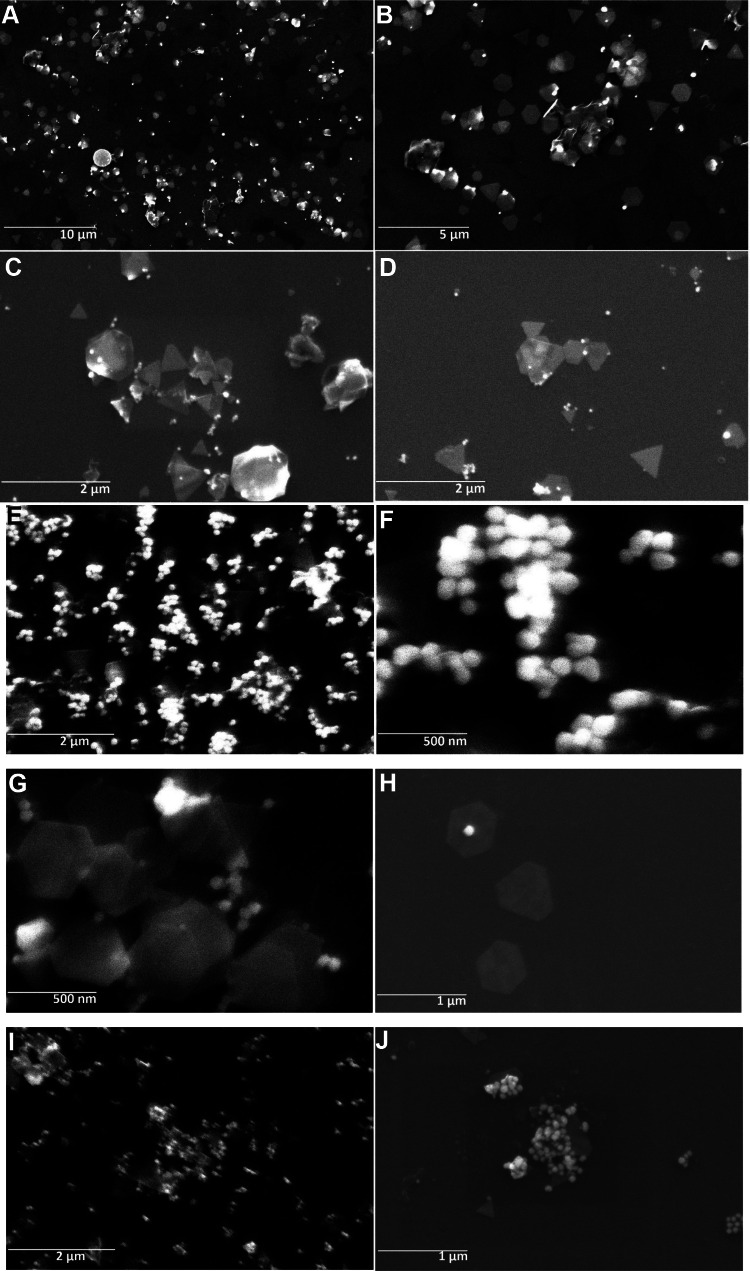

Fig. 3.

Morphological analysis of biosynthesized gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min AuNPs(A), gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min AuNPs(B), gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min AuNPs(C) and gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min AuNPs(D) at different FESEM magnifications

Morphological analysis

Furthermore, the properties like morphology, size, shape, and aggregation of the prepared AuNPs were explored by the FESEM technique. Figure 3 displays FESEM images of formed AuNPs at both lower and higher magnifications. It mostly reveals that AuNPs are well-dispersed, having different shapes such as hexagonal and spherical, and are predominantly triangular in nature at lower rpm. Triangular nanoparticles have three sharp vertices, which notably influence their electronic and optical properties. In a few instances, even the dimensions of a nanotriangle are altered by controlling experimental parameters (Métraux and Mirkin 2005). These triangular-shaped particles are also seen to be present as a combination of both, triangles as well as truncated triangles. Truncation seems to be a generic characteristic mostly in metal nanostructures that resemble disks such as silver or gold nanotriangles, although its formation is not clearly understood. The variation in size and dispersion of AuNPs might be because of several secondary metabolites present in the leaf extract (Mai et al. 2021). Here, at lower centrifugation speeds for AuNPs(A) and AuNPs(C), we got highly anisotropic nanostructures with a predominant triangular morphology consisting of a mixture of triangles, hexagons, and truncated triangles. Synthesized nanotriangles have edge lengths varying in the range of 420–800 nm for AuNPs(A) [Fig. 3A, B, C, D] and 430 to 615 nm for AuNPs(C) [Fig. 3G, H]; Whereas truncated triangles ranged between, smaller around 90–175 nm and larger around 400–450 nm. Some hexagons were also seen in the range of around 400 nm. At higher centrifugation speeds for AuNPs(B) and AuNPs(D), smaller-sized spheres also settle along with anisotropic nanostructures [Fig. 3E, F, I, J]. The particle size of spherical AuNPs ranged from 25 to 120 nm in diameter, with an average diameter in the range of 53–66 nm. Centrifugation, under the influence of a centrifugal field, moves particles away from the axis of rotation with different sedimentation velocities. When the centrifugal force surpasses the countering buoyant and frictional forces, sedimentation of the nanoparticles is observed. This sedimentation rate depends on the size, shape and density of the particles. When centrifuged at a lower speed i.e., at 500 rpm pellets of AuNPs will be obtained, mainly consisting of larger-sized anisotropic nanoparticles, whereas centrifugation at a higher speed i.e., 5000 rpm will sediment particles of smaller-sized nanoparticles. This separation of particles is motivated by the different shapes and sizes of nanoparticles (Sharma et al. 2009). We can thus separate spherical particles from anisotropic nanostructures, by just collecting the sedimentation at lower centrifugation speeds. The FESEM analysis clearly elucidates that the observed intense absorption in the NIR region detected for MD mediated synthesized AuNPs is because of the formed anisotropic nanostructures. It also indicates that the morphology and yield amount of biosynthesized AuNPs could be controlled by tuning the speed of centrifugation used for separation and purification.

X-ray diffraction studies

The crystallinity of biosynthesized AuNPs was revealed in an X-ray diffraction study, supporting the formation of AuNPs as shown in Fig. 4. The peaks were obtained between 30° and 80°. Comparing the obtained values with the standard one, we can confirm that the synthesized AuNPs have a Face Centered Cubic (FCC) phase with 2θ values in the range of 30°–80°. These values are indexed for AuNPs(A) as 38.08°, 44.28° and 64.5° [Fig. 4A] having sets of lattice planes corresponding to the Bragg reflections as (1 1 1), (2 0 0) and (2 2 0) respectively, indicating AuNPs have a monophasic nature with FCC symmetry (JCPDS No. 011174). Similarly, 2θ values for AuNPs(B) are 38.12°, 44.32°, 64.62°, 77.58° [Fig. 4B]; AuNPs(C) are 38.14°, 44.38°, 64.6°, 77.7° [Fig. 4C] and AuNPs(D) are 38.1°, 44.26°, 64.62°, 77.58° [Fig. 4D] respectively. Bragg reflections having sets of lattice planes as (111), (200), (220) and (311) index the basis of the FCC structure of AuNPs. (111) reflections show an intense and sharp peak as compared to other (200), (220) and (311) Bragg reflections that have relatively broad and weak peaks, suggesting a highly anisotropic nature of MD-mediated AuNPs along with (111)-oriented particles in the XRD analyzed film. Since no undesired peaks were obtained in the XRD spectra, we can conclude that highly pure nanoparticles with a high degree of crystallinity were synthesized. X-ray diffraction strongly suggests the monocrystalline nature of biosynthesized AuNPs. Considering the wavelength of 1.54056 Å of the X-ray source, the obtained 2θ values almost coincide with the JCPDS.NO.004–0784 for gold. This result even agreed well with numerous former studies that reported biosynthesized AuNPs (Ahmad et al. 2013; Donga et al. 2020; Cardoso-Avila et al. 2021; Abdoli et al. 2021; Sathiyaraj et al. 2021; Téllez-de-Jesús et al. 2021; Hosny et al. 2022).

Fig. 4.

Demonstrating X-ray diffraction pattern of AuNPs pellets (A) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min [AuNPs(A)]; (B) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min [AuNPs(B)]; (C) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min [AuNPs(C)]; (D) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min [AuNPs(D)]

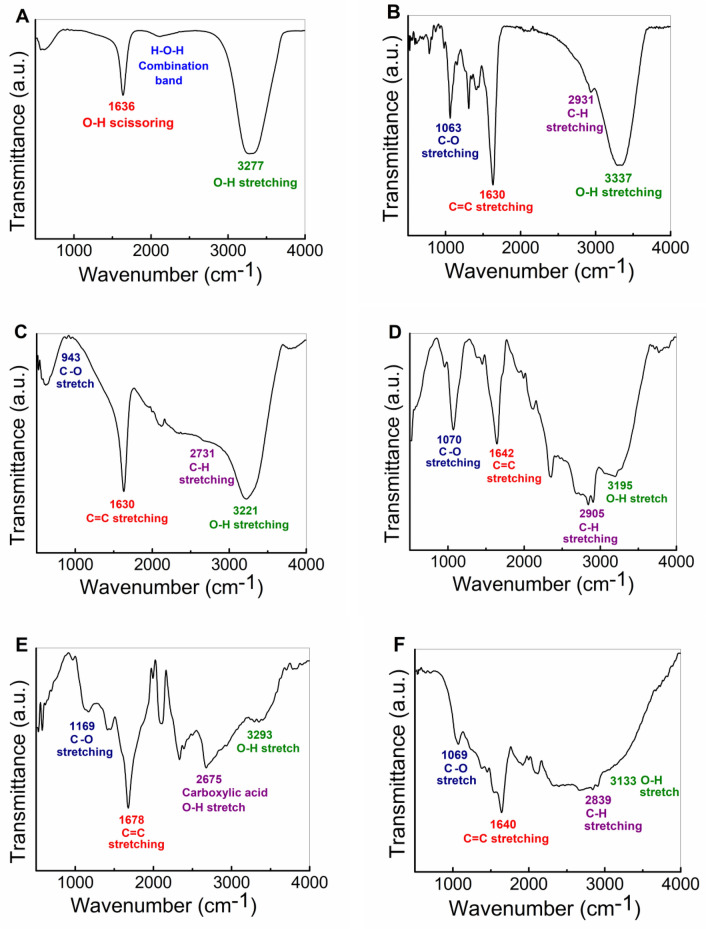

ATR-IR spectra analysis

The probable biomolecules present in MD leaf extract and their functional groups, which play a crucial role in the biosynthesis of AuNPs were revealed by ATR-IR analysis of AuNPs, MD leaf extract, and gold precursor. The ATR-IR spectra of chloroauric acid [Fig. 5A] which is used as a gold precursor, showed sharp peaks at 3277.55 cm−1 and 1636.29 cm−1, which coincided with peaks exhibited by water molecules, indicating the presence of water. 3277.55 cm−1 peak is O–H stretching, whereas 1636.29 cm−1 is O–H scissoring (Bellamy 1975). ATR-IR spectra of MD leaf extract [Fig. 5B] represents notable peaks at 3337.24 cm−1, 2931.30 cm−1, 1630.52 cm−1 and 1063.39 cm−1. The peak at 3337.24 cm−1 showed O–H stretching in alcohols and phenols whereas the 2931.30 cm−1 peak specifies C–H stretching vibration of the alkyl group and O–H stretching, preferably in carboxylic acids. Peaks at 1630.52 cm−1 represent C=C and C=O group stretching, whereas 1063.39 cm−1 represents C–O stretching in alcohols, and ethers, and amines C–N stretching along with CH3 rocking vibration. Small peaks were also observed at 1411.91 cm−1 signifying the presence of aromatic C=C and 1305.79 cm−1 showing the existence of the C–H group of carbohydrate compounds and C–N stretching in amines (Silverstein and Bassler 1962; Furniss et al. 1989). The pure pellet of gold nanoparticles also showed similar peaks at 3221.98 cm−1, 2731.24 cm−1, 1630.96 cm−1 and 943.22 cm−1 for AuNPs(A) [Fig. 5C]; 3195.60 cm−1, 2905.18 cm−1, 1642.81 cm−1 and 1070.93 cm−1 for AuNPs(B) [Fig. 5D]; 3293.15 cm−1, 2675.27 cm−1, 1678.05 cm−1 and 1169.59 cm−1 for AuNPs(C) [Fig. 5E] and 3133.91 cm−1, 2839.35 cm−1, 1640.49 cm−1 and 1069.94 cm−1 for AuNPs(D) [Fig. 5F] respectively. Compared to MD leaf extract, a decrease in wavenumbers is observed for functional groups of AuNPs indicating their association with biosynthesized AuNPs. MD leaf extract prior to bioreduction exhibited a notable peak at 3337.24 cm−1 which indicates the presence of hydroxyl groups (Furniss et al. 1989). For the synthesized pellet of AuNPs after reduction, peaks were shifted to lower wavenumbers, specifically at 3221.98 cm−1, 3195.60 cm−1, 3293.15 cm−1 and 3133.91 cm−1 respectively, signifying phenolic, carboxylic and alcoholic groups present in MD leaf extract. These groups are accountable for the bioreduction of Au3+ ions from precursor salt solutions to form AuNPs (Adewale et al. 2020). It is also reported that gold ions show stronger binding ability towards hydroxyl and carbonyl groups, leading to the formation of Au0 from the bioreduction of Au3+ by oxidation of hydroxyl to carbonyl groups (Pechyen et al. 2021). Similarly, Li et al. also published that shielding layers present at the exterior surface of nanoparticles are formed due to the existence of biomolecules having carboxyl and hydroxyl ions, which helps in the formation of stabilized nanoparticles (Li et al. 2007). This testimony also supports the fact that biological entities are naturally made great bearers of various reducing agents, which is not easily achievable in chemical synthesis.

Fig. 5.

ATR-IR spectra of (A) gold precursor salt, (B) MD leaf extract, Pure pellet of (C) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min [AuNPs(A)], (D) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min [AuNPs(B)], (E) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min [AuNPs(C)], (F) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min [AuNPs(D)]

GC–MS analysis

Identification of probable molecules was done using GC–MS analysis of MD leaf extract (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1). The mass spectrum of MD leaf extract showed nearly ten peaks. The GC–MS spectra were compared with NIST libraries to determine their retention time, area, height, molecular weight, and formula. It indicates the presence of phenolics, carbohydrates, fatty acids, sugars, esters, vitamins, as well as diterpene alcohols performing a significant role in the biosynthesis of AuNPs (Maestri et al. 2006).

HR-MS analysis

Identification of probable molecules was done using HR-MS analysis, of MD leaf extract on the basis of their mass to the charge ratio (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2). MD leaf extract proved the presence of various biomolecules that were seen in GC–MS analysis including long-chain and saturated fatty acids, alcohols, sugars, esters, vitamins, and phenolic groups, playing a vital role in the biosynthesis of AuNPs. MD leaf extract has molecular fragments with mass to the charge ratios 249, 273, 282, 297, 651 and 665 which correspond to pentadecanoic acid, n-Hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, octadecanoic acid, phytol, L-( +)-Ascorbic acid 2,6-dihexadecanoate and tris(2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl) phosphate. A plant metabolite with long-chain fatty acids is pentadecanoic acid. Hexadecanoic acid methyl ester is a fatty acid ester having antioxidant, nematicide, flavor, pesticide, anti-inflammatory, hypocholesterolemic, cancer preventive, antihistaminic, and antiandrogenic properties (Zaky Zayed et al. 2014). Octadecanoic acid (stearic acid) is a fatty acid having anti-inflammatory and recovery activity in rats from hepatic dysfunction of liver damage (Goradel et al. 2016). Phytol is a diterpene alcohol found abundantly in plants; it is one of the major compounds in chlorophyll (Dhifi et al. 2016). Phytol holds anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, antimicrobial, diuretic, and chemopreventive properties. It is consumed as a food additive as well as being used in vaccine formulations (Prabhadevi et al. 2012). It is also extensively used in the treatment of rheumatic arthritis, along with being a remedy for other diseases like parasite-caused schistosomiasis (Ogunlesi et al. 2009). L-( +)-Ascorbic acid 2,6-dihexadecanoate is an antioxidant compound containing vitamin C (Igwe et al. 2014). It is widely used in bronchitis, common cold, tuberculosis, gum disease, wounds, and to prevent and cure skin infections. L-( +)-Ascorbic acid 2,6-dihexadecanoate can also prevent arthritis, making Monstera deliciosa a therapeutic potential remedy for symptoms of arthritis, along with exhibiting anti-scorbutic, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumour, anti-nociceptive, anti-mutagenic, and anti-bacterial properties (Begum et al. 2017). It quenches the free radicals generated in the skin due to ultraviolet radiation and thus acts as an antioxidant (Okwu et al. 2010). Tris (2,4-di-tert- butylphenyl) phosphate is a phenol having strong antioxidative properties that can also act as a reducing agent by reducing Au3+ to stable AuNPs (Vinuchakkaravarthy et al. 2010).

NMR analysis

Identification of probable molecules was done using 1H-NMR analysis of MD leaf extract based on their chemical shifts, which provides information about the environment and number of protons present in the sample with the help of solvent D2O (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3). The broad peak at (∼ 4.8 ppm) indicates the solvent peak. Chemical shifts showed the presence of a distinguishing range of alcohols (3.1–4.1 ppm), alpha protons of nitro groups (4.1–4.3 ppm), alcoholic groups and primary alkyl (∼0.6–1.2 ppm), phenolic hydroxyl groups (∼ 7 ppm), proton attached to alkyl substituents (2.7–2.8 ppm) and C-ring containing aromatic protons (∼6.6–6.8 ppm) (Ward et al. 2007).

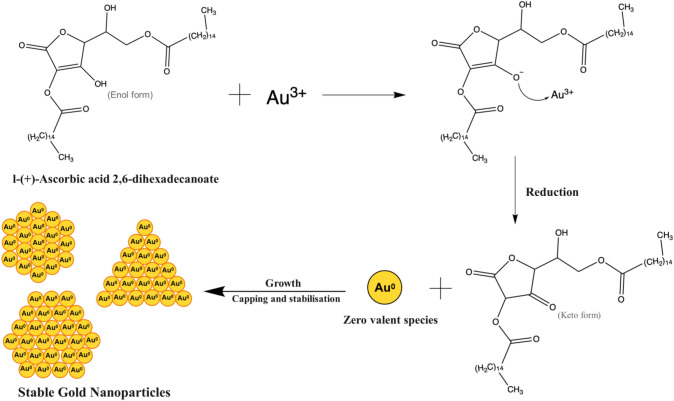

Plausible mechanism of biosynthesis of AuNPs

Figure 6 represents a plausible mechanism observed in the biosynthesis of AuNPs using MD leaf extract. Various fatty acids, esters, terpene alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and a series of normal hydrocarbons, along with additional compounds, are present in the MD source itself (Peppard et al. 1992). The proposed probable mechanism is by a phytochemical, based reaction underlying the formation of AuNPs, incorporates the reduction of chloroauric acid, which is a gold precursor salt, to form AuNPs. Phytochemicals play a significant function as a potent reducing agent, by presumably involving the reduction of chloroauric acid to form AuNPs through donating electrons. This uses MD leaf extract, which contains reducing molecules such as phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidants. These molecules have a higher ability to donate electrons or hydrogen atoms (Brewer 2011). The formation is supposed to begin by initially reducing gold ions (Au3+) to zerovalent ‘seed’ particles (Au0), which form gold clusters and further assist in the reduction of remaining gold ions (Kumari and Meena 2020). L-( +)-Ascorbic acid 2,6-dihexadecanoate is an antioxidant compound present in MD leaf extract that can reduce the gold precursor, thereby directing the biosynthesis of AuNPs. So, a possible hypothetical mechanism includes Au3+ ions accepting electrons from L-( +)-Ascorbic acid 2,6-dihexadecanoate thus resulting in the reduction of these ions to form Au atoms. The bottom-up approach assists in the formation of AuNPs through atoms-to-atoms addition process (Tripathy et al. 2020). During biosynthesis, biomolecules from MD leaf extract stabilize and coat these zero-valent species (Au0) leading to the formation of AuNPs. Secondary metabolites existing in the plant extract act as capping and stabilizing agents. The synthesis mechanism we propose is corroborated by previous reports (Khan et al. 2020, 2021; El-Borady et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2021; Hosny et al. 2022). GC–MS, HR-MS, ATR-IR, and NMR studies have all supported the interaction of biomolecules with AuNPs. The so-formed AuNPs have high stability and are further enhanced by their association with various biomolecules present in MD leaf extract. Despite using the same precursor salt, different physico-chemical properties are seen in biosynthesized AuNPs. This is mainly due to the influence of biomolecules, which cumulatively function in imparting stability and also act as binding units, thereby directing the morphology of the formed AuNPs.

Fig. 6.

Plausible mechanism of biosynthesized AuNPs by utilizing MD leaf extract

Antibacterial assay of AuNPs

The antibacterial activity of AuNPs is not as evident as that of other noble metals like silver nanoparticles (Shamaila et al. 2016; Boruah et al. 2021). The antibacterial potential of biosynthesized AuNPs obtained from MD leaf extract was analysed for both sets that were collected at different centrifugation speeds. Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) microorganisms were used by well-based diffusion technique, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Three different concentrations (2.5 mg/ml, 5 mg/ml and 10 mg/ml) of biosynthesized AuNPs were used to test their antibacterial potential, done in triplicate. The MD leaf extract was also tested for its antibacterial activity, which showed no antibacterial effect on any of the examined microorganisms. Even synthesized AuNPs did not exhibit any antibacterial action against both the Gram-positive as well as Gram-negative microorganisms. Lack of antibacterial properties showing at all concentrations was indisputable in each nanoparticle, indicating their non-antibacterial features. There is no uniformity in researchers views on the antibacterial effects of AuNPs. Many scholars believe AuNPs do not have or do not possess obvious antibacterial properties, whereas some believe they might have antibacterial activity because of the present chemicals coexisting in the form of gold ions and surface coating agents. Several reports have also been published elaborating on the excellent antibacterial activity of AuNPs having well-defined inhibition zones against different bacteria (Arief et al. 2020; Shirzadi-Ahodashti et al. 2020; Huai et al. 2021; Basiratnia et al. 2021; Sathiyaraj et al. 2021; Ahmed et al. 2022; Shah et al. 2022; Yadi et al. 2022). The exact mechanism of inactivating bacterial cells used by these AuNPs is still unknown. The most plausible mechanism includes growth in membrane permeability causing disruption of cell membrane directing to cell death, mostly because of bacterial nucleic acid damage (Jabir et al. 2018), leakage of cytoplasmic contents, change of the structure, degradation, and ROS generation, which is influenced by phytochemicals that are absorbed on the surface of nanoparticles (Khan et al. 2020). The even size and shape of nanoparticles play a significant role in triggering the cell death process (Téllez-de-Jesús et al. 2021). AuNPs cause reversible damage in the cell wall by forming complexes with Sulphur, Nitrogen, Oxygen and Phosphorus atoms upon interaction with proteins which is led by the generation of irregular pits on the cell wall (Donga et al. 2020). AuNPs can also alter the membrane potential of the bacterial surface and inhibit protein and ATP synthesis (Cui et al. 2012). One of the key elements responsible for its antibacterial action is the interaction between the bacterial cell membrane and the biomolecules that are covering the nanoparticles. The toxicity of AuNPs depends on the molecules present in MD leaf extract (Zhang et al. 2015). A possibility of coated biomolecules of AuNPs having affinity issues towards the cell membrane of bacteria might happen, resulting in the failure of antibacterial activities. In such cases, the bacteria remain protected, causing a lack of antibacterial activity since there is no physical damage done to the bacteria due to the inaccessible physical contact between biomolecules and AuNPs. Another possibility includes low concentrations of AuNPs, as they generate just singlet oxygen unlike superoxide and hydroxyl radicals produced by silver nanoparticles that are incapable of passing the bacterial tolerance threshold (Zhang et al. 2013). MD leaf extract contains various phenolics, carbohydrates, fatty acid esters, vitamins, as well as diterpene alcohol groups, which might strongly associate with AuNPs. This strong bonding between biomolecules and AuNPs hampers the bioavailability of gold ions, leading to a negative impact on their toxicity towards bacterial cells. Different parameters like morphology, ligand type, concentration, solubility, illumination conditions, surface modification, surface charge, surface functionalization, defects, and so on affect the toxicity potential and antibacterial properties of AuNPs (Goodman et al. 2004; Feng et al. 2015; Penders et al. 2017). Gram-positive as well as Gram-negative microorganisms both show size and concentration-dependent toxicity. Nanoparticle size is inversely proportional to antibacterial potential. The antibacterial potential of nanoparticles is enhanced by higher ROS, generated by smaller-sized nanoparticles with a large surface area (Ankamwar and Gharpure 2019).

Fig. 7.

Antibacterial assay of biosynthesized (A) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min [AuNPs(A)]; (B) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 5 min [AuNPs(B)]; (C) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging original solution of AuNPs at 500 rpm, synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min [AuNPs(C)]; (D) Gold nanoparticles pellet obtained by centrifuging supernatant of AuNPs at 5000 rpm synthesized using MD extract heated for 10 min [AuNPs(D)]

The so-synthesized AuNPs can turn out to be highly promising options for drug delivery applications. This is due to their special characteristics that facilitate the transportation and release of concerned drugs to the target site (Paciotti et al. 2004; Shittu et al. 2017). Non-antibacterial AuNPs have been proven to be promising drug carriers because of their inert nature, which avoids any cross-reactivity. While exploiting AuNPs for drug delivery and biomedical applications, certain shortfalls are encountered as well. AuNPs can effortlessly penetrate bacterial cell membranes; due to this, their retention within the cell is the main matter of concern. During the formation of biofilm, and interaction with the cell wall, AuNPs are trapped in the biofilm thus causing distortion in the cell wall (Arief et al. 2020). Their presence inside the cell affects its characteristic properties, including its morphology, ligand type, solubility, concentration, surface charge and modification, which play an important part in leading to the cytotoxic and genotoxic states of nanoparticles (Gerber et al. 2013). Behavioural patterns in vivo can be predicted by detailed analysis of these biosynthesized AuNPs to decrease their harmful effects on the human body in the long run.

Antifungal assay of AuNPs

AuNPs can show antifungal properties, and their in vitro fungicidal ability can be estimated by utilizing different fungal species, such as Penicillium expansum, Colletotrichum gloeosporioids, Fusarium solani, Aspergillus flavus, Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani, Candida albicans, and many more. An analysis was done on the antifungal abilities of synthesized AuNPs obtained from MD leaf extract. Different fungi (Penicillium expansum, Fusarium solani, Rhizoctonia solani, Fusarium oxysporum) were used by the well diffusion technique, as shown in Fig. 8. AuNPs with a concentration of 10 mg/mL were used for testing antifungal properties in triplicate. The MD leaf extract was also tested for antifungal activity, which showed no activity against all four fungi. Even biosynthesized AuNPs failed to exhibit antifungal activity against any of these fungi.

Fig. 8.

Antifungal assay of biosynthesized AuNPs

Very few investigations have been done to comprehend the antifungal ability of AuNPs and the different variables impacting its potential. Comparatively, a large amount of research work is reported concentrating on the antibacterial activity of AuNPs (Adebayo et al. 2019; Ahmed et al. 2022). Biosynthesized AuNPs showing antifungal properties depend on several pathways, such as disturbance of fundamental cell structures including cell organelles, wall, and membrane, leakage of cytoplasmic contents, arrest of vital biological pathways allied with associated biomacromolecules, acidification of the intracellular environment, and loss of charge over the antioxidant system via ROS generation (Dananjaya et al. 2020; Balasubramanian et al. 2020). The exact molecular mechanism involved in the antifungal activity of AuNPs is still not fully comprehended, and the pertinent study is still in its infancy. Different parameters affecting its antifungal potential can be derived based on the little available information, which consists of morphology, structure, solubility, concentration, and surface activity. Shape, size, and solubility are also observed notably affecting the antifungal properties of AuNPs. Smaller-sized AuNPs are observed to be more fungicidal than larger ones since they easily penetrate through the fungal cell walls, leading to cell death (Adebayo et al. 2019). The possibility of AuNPs directly interacting with proteins also causes enhanced antifungal activity. The plausible mechanism of fungicidal action, of AuNPs involves cell death caused by intracellular acidification led through the inhibition of H+-APTase (Wani and Ahmad 2013). Surface functionalization enables AuNPs to be more stable, functional, biocompatible, selective, and sensitive regarding their fungicidal action resulting in enhanced antifungal potential. Antifungal potential is adversely affected by direct molecular interaction with biomolecules. This results in the inert nature of AuNPs due to the strong association of biomolecules with nanoparticles. In the present study, a similar result has been observed where a strong association of AuNPs with biomolecules leads to a non-antifungal nature. There is also a possibility of various fungi developing resistance methods, such as changes in stress reactions, to bear suboptimal amounts of AuNPs. Apart from their physicochemical features, the structure of fungal membranes also impacts the antifungal potential of nanoparticles. Macro proteins like β-1,3-D-glucan, β-1,6-D-glucan make up the fungal cell wall, whereas rigidity is induced by other biomolecules, including polysaccharides, mannans, proteins, chitin, lipids, and glucans. It is highly difficult for AuNPs to penetrate inside this rigid fungal cell wall and damage the cell, resulting in a reduction of the antifungal potential of AuNPs.

Conclusions

Thus, we have successfully reported an eco-friendly, simple, and cost-effective approach for the green biosynthesis of stable gold nanoparticles. An aqueous extract of Monstera deliciosa leaves was utilized to synthesize AuNPs, along with separating them at different speeds of centrifugation and further characterised them using various techniques. In biosynthesis, the role of different biomolecules present in plant extracts is underlined by notable differences in the physicochemical properties of AuNPs. Results confirm the formation of stable AuNPs having a substantial proportion of single crystalline, highly (111)-oriented AuNPs with riveting optical absorption in the NIR region of the electromagnetic spectrum. The average diameter of synthesised spherical AuNPs ranged around 53–66 nm whereas the edge length of the obtained triangles varied from 420 to 800 nm. Negligible antibacterial and antifungal activity was shown by all AuNPs against all four organisms, including Gram-positive as well as Gram-negative microorganisms. The lack of antimicrobial properties of AuNPs reported here underlines their inert and biocompatible nature. This makes AuNPs a potential substitute in biomedical applications like drug delivery systems because of their biocompatible carrier system with targeted specificity. Still, more research regarding the biosynthesis of AuNPs is needed to explore the role played and potential use of different biomolecules present in plant extract.

Conflict of interest

The authors would like to declare no competing economic interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

BA extend gratitude to Prof. Avinash C. Pandey, Director, Inter-University Accelerator Centre (IUAC), Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, Near Vasant Kunj, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi, 110067, India and Co-Investigator Dr. Ambuj Tripathi, Scientist ‘H’ IUAC, New Delhi for IUAC Project. All authors thank to Ph.D. student Rachana Yadwade for Antimicrobial Tests. (Financial Support by IUAC Project Ref. No. IUAC/XIII.7/UFR-70316 Dt. August 26, 2021). JS thanks to IUAC for Project Fellowship.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, BA.

References

- Abdoli M, Arkan E, Shekarbeygi Z, Khaledian S. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Centaurea behen leaf aqueous extract and investigating their antioxidant and cytotoxic effects on acute leukemia cancer cell line (THP-1) Inorg Chem Commun. 2021;129:108649. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2021.108649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo AE, Oke AM, Lateef A, et al. Biosynthesis of silver, gold and silver–gold alloy nanoparticles using Persea americana fruit peel aqueous extract for their biomedical properties. Nanotechnol Environ Eng. 2019;4:13. doi: 10.1007/s41204-019-0060-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adewale OB, Egbeyemi KA, Onwuelu JO, et al. Biological synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using leaf extracts of Crassocephalum rubens and their comparative in vitro antioxidant activities. Heliyon. 2020;6(11):E05501. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad T, Wani IA, Manzoor N, et al. Biosynthesis, structural characterization and antimicrobial activity of gold and silver nanoparticles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;107:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A, Rauf A, Hemeg HA, et al. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using Opuntia dillenii aqueous extracts: characterization and their antimicrobial assessment. J Nanomater. 2022;2022:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2022/4804116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola V, Meneghetti M. Size evaluation of gold nanoparticles by UV-vis spectroscopy. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:4277–4285. doi: 10.1021/jp8082425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amina SJ, Guo B. A review on the synthesis and functionalization of gold nanoparticles as a drug delivery vehicle. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:9823–9857. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S279094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankamwar B, Kamble V, Sur UK, Santra C. Spectrophotometric evaluation of surface morphology dependent catalytic activity of biosynthesized silver and gold nanoparticles using UV-vis spectra: a comparative kinetic study. Appl Surf Sci. 2016;366:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.01.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ankamwar B, Pansare S, Sur UK. Centrifuge controlled shape tuning of biosynthesized gold nanoparticles obtained from Plumbago zeylanica leaf extract. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2017;17:1041–1045. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2017.12662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankamwar B, Gharpure S (2019) Non-antibacterial biogenic gold nanoparticles an ulterior drug carrier. Mater Res Exp 6:1050c7. 10.1088/2053-1591/AB429F

- Ankamwar B, Gharpure S (2020) Gold and silver nanoparticles used for SERS detection of S. aureus and E. coli. Nano Exp 1:010020. 10.1088/2632-959X/ab85b4

- Ankamwar B, Kirtiwar S, Shukla A (2020) Plant-mediated green synthesis of nanoparticles,1. Springer Singapore, 221–234. 10.1007/978-981-15-2195-9_17

- Arief S, Nasution FW, Zulhadjri LA. High antibacterial properties of green synthesized gold nanoparticles using Uncaria gambir Roxb. leaf extract and triethanolamine. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2020;10:124–130. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2020.10814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arvizo R, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P. Gold nanoparticles: opportunities and challenges in nanomedicine. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;7:753–763. doi: 10.1517/17425241003777010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S, Kala SMJ, Pushparaj TL. Biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Jasminum auriculatum leaf extract and their catalytic, antimicrobial and anticancer activities. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;57:101620. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basiratnia E, Einali A, Azizian-Shermeh O, Mollashahi E, Ghasemi A. Biological synthesis of gold nanoparticles from suspensions of green microalga Dunaliella salina and their antibacterial potential. Bionanoscience. 2021;11:977–988. doi: 10.1007/s12668-021-00897-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Begum S, Priya S, Sundararajan R, Hemalatha S (2017) Novel anticancerous compounds from Sargassum wightii: In silico and in vitro approaches to test the antiproliferative efficacy. J Adv Pharm Edu Res 7(3):272–277. http://www.japer.in/

- Bellamy LJ. The Infra-red spectra of complex molecules. Springer, Dordrecht. 1975 doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-6017-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boomi P, Poorani GP, Selvam S, et al. Green biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Croton sparsiflorus leaves extract and evaluation of UV protection, antibacterial and anticancer applications. Appl Organomet Chem. 2020;34:e5574. doi: 10.1002/aoc.5574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boruah JS, Devi C, Hazarika U, et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using an antiepileptic plant extract: in vitro biological and photo-catalytic activities. RSC Adv. 2021;11:28029–28041. doi: 10.1039/d1ra02669k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MS. Natural antioxidants: sources, compounds, mechanisms of action, and potential applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2011;10:221–247. doi: 10.1111/J.1541-4337.2011.00156.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso-Avila PE, Patakfalvi R, Rodríguez-Pedroza C, et al. One-pot green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using: Rosa canina L. extract. RSC Adv. 2021;11:14624–14631. doi: 10.1039/d1ra01448j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Huo Y, Han YX, et al. Biosynthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles from Scutellaria baicalensis roots and in vitro applications. Appl Phys A Mater Sci Process. 2020;126:424. doi: 10.1007/s00339-020-03603-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Zhao Y, Tian Y, et al. The molecular mechanism of action of bactericidal gold nanoparticles on Escherichia coli. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2327–2333. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyril N, George JB, Nair PV, et al. Catalytic activity of Derris trifoliata stabilized gold and silver nanoparticles in the reduction of isomers of nitrophenol and azo violet. Nano-Struct Nano-Objects. 2020;22:100430. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoso.2020.100430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dananjaya SHS, Thu Thao NT, Wijerathna HMSM, et al. In vitro and in vivo anticandidal efficacy of green synthesized gold nanoparticles using Spirulina maxima polysaccharide. Process Biochem. 2020;92:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2020.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong WH, Borm PJA. Drug delivery and nanoparticles: applications and hazards. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3:133–149. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhas TS, Sowmiya P, Kumar VG, et al. Antimicrobial effect of Sargassum plagiophyllum mediated gold nanoparticles on Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020;26:101627. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhifi W, Bellili S, Jazi S, et al. Essential oils’ chemical characterization and investigation of some biological activities: a critical review. Medicines (basel) 2016;3(4):25. doi: 10.3390/medicines3040025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan VD, Huynh BA, Nguyen TD, et al. Biosynthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Codonopsis pilosula roots for antibacterial and catalytic applications. J Nanomater. 2020;2020:1–18. doi: 10.1155/2020/8492016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donga S, Bhadu GR, Chanda S. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activities of gold nanoparticles green synthesized using Mangifera indica seed aqueous extract. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2020;48:1315–1325. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2020.1843470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Borady OM, Ayat MS, Shabrawy MA, Millet P. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Parsley leaves extract and their applications as an alternative catalytic, antioxidant, anticancer, and antibacterial agents. Adv Powder Technol. 2020;31(10):4390–4400. doi: 10.1016/j.apt.2020.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ElMitwalli OS, Barakat OA, Daoud RM, et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using cinnamon bark extract, characterization, and fluorescence activity in Au/eosin Y assemblies. J Nanopart Res. 2020;22:309. doi: 10.1007/s11051-020-04983-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faraday M (1857) The bakerian lecture: experimental relations of gold (and other metals) to light. RSPT 147:145–181. https://www.jstor.org/stable/108616

- Feng ZV, Gunsolus IL, Qiu TA, et al. Impacts of gold nanoparticle charge and ligand type on surface binding and toxicity to Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Chem Sci. 2015;6:5186–5196. doi: 10.1039/C5SC00792E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furniss BS, Hannaford a J, Smith PWG, Tatchell a R, Vogel’s textbook of practical organic chemistry 5th ED revised. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A, Bundschuh M, Klingelhofer D, Groneberg DA. Gold nanoparticles: recent aspects for human toxicology. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2013;8:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CM, McCusker CD, Yilmaz T, Rotello VM. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles functionalized with cationic and anionic side chains. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:897–900. doi: 10.1021/bc049951i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goradel NH, Eghbal MA, Darabi M, et al (2016) Improvement of liver cell therapy in rats by dietary stearic acid. Iran Biomed J 20:217–222. 10.7508%2Fibj.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hatipoğlu A (2021) Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles from Prunus cerasifera pissardii nigra leaf and their antimicrobial activities on some food pathogens. Prog Nutr 23:e2021241. 10.23751/pn.v23i3.11947

- Hosny M, Fawzy M, El-Badry YA, et al. Plant-assisted synthesis of gold nanoparticles for photocatalytic, anticancer, and antioxidant applications. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2022;26(2):101419. doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2022.101419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huai PC, Harun NA, Pei AUE, et al (2021) Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) by Diopatra claparedii grube, 1878 (polychaeta: Onuphidae) and its antibacterial activity. Sains Malays 50(5):1309–1320. 10.17576/jsm-2021-5005-11

- Igwe OU, Igwe US, Okwunodulu F (2014) Investigation of bioactive phytochemical compounds from the chloroform extract of the leaves of Phyllanthus amarus by GC-MS technique. IJCPS 2(1):554–560. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281776251

- Jabir MS, Taha AA, Sahib UI. Linalool loaded on glutathione-modified gold nanoparticles: a drug delivery system for a successful antimicrobial therapy. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46:345–355. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2018.1457535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Shahid S, Lee CS. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Clerodendrum inerme; characterization, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activities. Biomolecules. 2020;10(6):835. doi: 10.3390/biom10060835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Shahid S, Ayaz A, et al. Phytomolecules-coated NiO nanoparticles synthesis using Abutilon indicum leaf extract: antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer activities. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:1757–1773. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S294012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Ali S, Latif S, Mehmood A. Biological synthesis of nanoparticles and their applications in sustainable agriculture production. Nat Sci. 2022;14:226–234. doi: 10.4236/ns.2022.146022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kharey P, Dutta SB, Gorey A, et al. Pimenta dioica mediated biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles and evaluation of its potential for theranostic applications. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:7901–7908. doi: 10.1002/slct.202001230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthi R, Bharathakumar S, Malaikozhundan B, Mahalingam PU. Mycofabrication of gold nanoparticles: optimization, characterization, stabilization and evaluation of its antimicrobial potential on selected human pathogens. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2021;35:102107. doi: 10.1016/J.BCAB.2021.102107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari P, Meena A. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles from Lawsoniainermis and its catalytic activities following the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2020;606:125447. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaVan DA, McGuire T, Langer R. Small-scale systems for in vivo drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/NBT876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Shen Y, Xie A, et al (2007) Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Capsicum annuum L. extract. Green Chem 9(8):852–858. 10.1039/B615357G

- Liu XY, Wang JQ, Ashby CR, et al. Gold nanoparticles: synthesis, physiochemical properties and therapeutic applications in cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26(5):1284–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestri DM, Nepote V, Lamarque AL, Zygadlo JA (2006) Natural products as antioxidants. In: phytochemistry: advances in research. Research Signpost, Trivandrum, pp 105–135

- Mai XT, Tran MC, Hoang AQ, et al. Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells. Green Process Synth. 2021;10:73–84. doi: 10.1515/gps-2021-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Métraux GS, Mirkin CA. Rapid thermal synthesis of silver nanoprisms with chemically tailorable thickness. Adv Mater. 2005;27(17):412–415. doi: 10.1002/adma.200401086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney P. Surface Plasmon Spectroscopy of Nanosized Metal Particles. Langmuir. 1996;12:788–800. doi: 10.1021/LA9502711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- My-Thao Nguyen T, Anh-Thu Nguyen T, Tuong-Van Pham N, et al. Biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles from waste Passiflora edulis peels for their antibacterial effect and catalytic activity. Arab J Chem. 2021;14:103096. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ningaraju S, Munawer U, Raghavendra VB, et al. Chaetomium globosum extract mediated gold nanoparticle synthesis and potent anti-inflammatory activity. Anal Biochem. 2021;612:113970. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2020.113970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunlesi M, Okiei W, Ofor E, Osibote A (2009) Analysis of the essential oil from the dried leaves of Euphorbia hirta Linn (Euphorbiaceae), a potential medication for asthma. Afr J Biotechnol 8(24):7042–7050. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228355621

- Okwu DE, Ighodaro BU (2010) GC-MS evaluation of bioactive compounds and antibacterial activity of the oil fraction from the leaves of Alstonia boonei De Wild. Der Pharma Chem 2:261 – 272. https://www.scinapse.io/papers/2409628206

- Paciotti GF, Myer L, Weinreich D, et al. Colloidal gold: a novel nanoparticle vector for tumor directed drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2004;11:169–183. doi: 10.1080/10717540490433895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen M, Kumar A, Khan MS, et al. Comparative study of biogenically synthesized silver and gold nanoparticles of Acacia auriculiformis leaves and their efficacy against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;203:292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.01.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechyen C, Ponsanti K, Tangnorawich B, Ngernyuang N. Waste fruit peel – mediated green synthesis of biocompatible gold nanoparticles. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;14:2982–2991. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.08.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penders J, Stolzoff M, Hickey DJ, et al. Shape-dependent antibacterial effects of non-cytotoxic gold nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:2457–2468. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S124442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppard TL. Volatile flavor constituents of Monstera deliciosa. J Agric Food Chem. 1992;40(2):257–262. doi: 10.1021/jf00014a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RE, Lee TH. Composition and physiology of Monstera deliciosa fruit and juice. J Food Sci. 1977;42:1132–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1977.tb12687.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phukan S, Bharali P, Das AK, Rashid MH. Phytochemical assisted synthesis of size and shape tunable gold nanoparticles and assessment of their catalytic activities. RSC Adv. 2016;6:49307–49316. doi: 10.1039/C5RA23535A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhadevi V, Sahaya SS, Johnson M, et al (2012) Phytochemical studies on Allamanda cathartica L. using GC–MS. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2(2):S550–S554. 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60272-X

- Rabeea MA, Owaid MN, Aziz AA, et al. Mycosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using the extract of Flammulina velutipes, Physalacriaceae, and their efficacy for decolorization of methylene blue. J Environ Chem Eng. 2020;8(3):103841. doi: 10.1016/J.JECE.2020.103841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VU, Viteesha V, Suma K, Nagababu P (2015) Evaluation of phytochemical constituents, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Monstera deliciosa liebm. stem extracts. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 4(11):1422–1433. https://storage.googleapis.com/journal-uploads/wjpps/article_issue/1446292103.pdf

- Roy A, Pandit C, Gacem A, et al. Biologically derived gold nanoparticles and their applications. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2022;2022:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2022/8184217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathiyaraj S, Suriyakala G, Dhanesh Gandhi A, et al. Biosynthesis, characterization, and antibacterial activity of gold nanoparticles. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(12):1842–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpathy S, Patra A, Ahirwar B, Hussain MD (2020) Process optimization for green synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by extract of Hygrophila spinosa T. Anders and their biological applications. Physica E Low Dimens Syst Nanostruct 121:113830. 10.1016/j.physe.2019.113830

- Shah S, Shah SA, Faisal S, et al. Engineering novel gold nanoparticles using Sageretia thea leaf extract and evaluation of their biological activities. J Nanostructure Chem. 2022;12:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s40097-021-00407-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shamaila S, Zafar N, Riaz S, et al. Gold nanoparticles: an efficient antimicrobial agent against enteric bacterial human pathogen. Nanomater. 2016;6(4):71. doi: 10.3390/NANO6040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar SS, Rai A, Ankamwar B, et al. Biological synthesis of triangular gold nanoprisms. Nat Mater. 2004;3:482–488. doi: 10.1038/nmat1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V, Park K, Srinivasarao M. Shape separation of gold nanorods using centrifugation. PNAS. 2009;106(13):4981–4985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800599106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirzadi-Ahodashti M, Mortazavi-Derazkola S, Ebrahimzadeh MA. Biosynthesis of noble metal nanoparticles using Crataegus monogyna leaf extract (CML@X-NPs, X= Ag, Au): antibacterial and cytotoxic activities against breast and gastric cancer cell lines. Surf Interfaces. 2020;21:100697. doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shittu KO, Bankole MT, Abdulkareem AS, et al. Application of gold nanoparticles for improved drug efficiency. Adv Nat Sci: Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2017;8:035014. doi: 10.1088/2043-6254/AA7716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein RW, Bassler GC. Spectrometric identification of organic compounds. J Chem Educ. 1962;39:546–553. doi: 10.1021/ED039P546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sk I, Khan MA, Haque A, et al. Synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using Malva verticillata leaves extract: study of gold nanoparticles catalysed reduction of nitro-Schiff bases and antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles. CRGSC. 2020;3:100006. doi: 10.1016/j.crgsc.2020.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song WC, Kim B, Park SY, et al. Biosynthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles using Sargassum horneri extract as catalyst for industrial dye degradation. Arab J Chem. 2022;15(9):104056. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunayana N, Uzma M, Dhanwini RP, et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles from Vitex negundo leaf extract to inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation through in vitro and in vivo. J Clust Sci. 2020;31:463–477. doi: 10.1007/s10876-019-01661-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Téllez-de-Jesús DG, Flores-Lopez NS, Cervantes-Chávez JA, Hernández-Martínez AR. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of encapsulated Au and Ag nanoparticles synthesized using Argemone mexicana L extract, against antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Candida albicans. Surf Interfaces. 2021;27:101456. doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy A, Behera M, Rout AS, et al (2020) Optical, structural, and antimicrobial study of gold nanoparticles synthesized using an aqueous extract of Mimusops elengi raw fruits. Biointerface Res Appl Chem 10(6):7085–7096. 10.33263/BRIAC106.70857096

- Vinuchakkaravarthy T, Sangeetha CK, Velmurugan D. Tris(2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl) phosphate. Acta Crystallogr Sect E: Struct Rep Online. 2010;66:o2207–o2208. doi: 10.1107/S1600536810029673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo TT, Dang CH, Doan VD, et al. Biogenic synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles from Lactuca indica leaf extract and their application in catalytic degradation of toxic compounds. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2020;30:388–399. doi: 10.1007/s10904-019-01197-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Meng Y, Zhu H, et al. Green synthesized gold nanoparticles using Viola betonicifolia leaves extract: characterization, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytobiocompatible activities. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:7319–7337. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S323524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani IA, Ahmad T. Size and shape dependant antifungal activity of gold nanoparticles: a case study of Candida. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;101:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JL, Baker JM, Beale MH. Recent applications of NMR spectroscopy in plant metabolomics. FEBS J. 2007;274:1126–1131. doi: 10.1111/J.1742-4658.2007.05675.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue NC, Zhou CH, Chu ZY, et al. Barley leaves mediated biosynthesis of Au nanomaterials as a potential contrast agent for computed tomography imaging. Sci China Technol Sci. 2021;64:433–440. doi: 10.1007/s11431-019-1546-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yadi M, Azizi M, Dianat-Moghadam H, et al. Antibacterial activity of green gold and silver nanoparticles using ginger root extract. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2022;45:1905–1917. doi: 10.1007/s00449-022-02780-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaky Zayed M, Ahmad F, Ho W-S, et al (2014) GC-MS analysis of phytochemical constituents in leaf extracts of Neolamarckia cadamba (rubiaceae) from Malaysia. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 6(9):123–127. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266735552

- Zhang W, Li Y, Niu J, Chen Y. Photogeneration of reactive oxygen species on uncoated silver, gold, nickel, and silicon nanoparticles and their antibacterial effects. Langmuir. 2013;29:4647–4651. doi: 10.1021/la400500t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Shareena Dasari TP, Deng H, Yu H. Antimicrobial activity of gold nanoparticles and ionic gold. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 2015;33:286–327. doi: 10.1080/10590501.2015.1055161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, BA.