Abstract

Introduction

The aim of our work is to assess the prevalence of probable major depressive disorder and/or probable generalized anxiety disorder (pMDD/pGAD) in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and to evaluate the efficacy of tofacitinib on RA symptoms stratified by baseline pMDD/pGAD status.

Methods

Data were pooled from five phase 3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and one phase 3b/4 RCT, assessing tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily (BID), adalimumab (two RCTs), or placebo. pMDD/pGAD was defined as Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) Mental Component Summary (MCS) score ≤ 38. Efficacy outcomes over 12 months included least squares mean change from baseline in SF-36 MCS score and Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, proportions of patients with pMDD/pGAD in those with baseline pMDD/pGAD, and American College of Rheumatology 20/50/70 response, and Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate remission (< 2.6) rates.

Results

A total of 4404 patients with non-missing baseline values were included. Baseline pMDD/pGAD was reported by 44.5%, 39.8%, 45.4%, and 39.1% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg BID, tofacitinib 10 mg BID, adalimumab, and placebo, respectively. SF-36 MCS improvements were greater for tofacitinib versus adalimumab/placebo through month 6, with numerical improvements for tofacitinib versus adalimumab sustained through month 12, when the proportions of patients with baseline pMDD/pGAD who continued to have pMDD/pGAD were reduced. RA efficacy outcomes were generally similar in patients with/without baseline pMDD/pGAD.

Conclusions

The percentage of patients with pMDD/pGAD reduced from baseline over 1 year of treatment with tofacitinib or adalimumab. Effective treatment of underlying RA may lead to improvements in depression and anxiety, based on the SF-36 MCS. Specially designed studies using gold-standard diagnostic tools would be warranted to investigate this further.

Video Abstract available for this article.

Trial Registration

NCT00960440, NCT00847613, NCT00814307, NCT00856544, NCT00853385, NCT02187055.

Video Abstract (MP4 204475 KB)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-023-00612-7.

Keywords: Anxiety, JAK inhibitor, Rheumatoid arthritis, Tofacitinib

Plain Language Summary

Tofacitinib is a medicine used to treat rheumatoid arthritis (swollen and painful joints). A total of 4400 patients with moderate or severe rheumatoid arthritis who were taking part in tofacitinib clinical trials completed a survey about their general health and well-being at that time. We used their answers to determine whether they were likely to have depression or anxiety. We then looked at how common depression or anxiety was in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and whether having depression or anxiety affected how patients responded to tofacitinib treatment. It is important to note that tofacitinib is not approved for the treatment of depression or anxiety, and these clinical trials were not designed to assess whether tofacitinib improved depression or anxiety symptoms. About 40% of patients likely had depression or anxiety when they started a clinical trial. This percentage decreased among patients who received tofacitinib treatment over a year. Patients treated with tofacitinib showed more improvement in their depression or anxiety than those treated with placebo. Over a year of treatment, tofacitinib improved signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, for example, the number of swollen or painful joints and fatigue. Having depression or anxiety did not change the way that patients responded to tofacitinib. This research shows how treating rheumatoid arthritis symptoms may also improve depression and anxiety symptoms. However, specially designed studies are needed to confirm this.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-023-00612-7.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Depression and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have a complex bidirectional relationship, and the prevalence of depression is higher among patients with RA than in the general population. |

| We assessed the prevalence of probable major depressive disorder and/or probable generalized anxiety disorder (pMDD/pGAD) in patients with moderate-to-severe RA who participated in six clinical trials of tofacitinib, and evaluated the efficacy of tofacitinib on RA symptoms by baseline pMDD/pGAD status. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The percentage of patients with pMDD/pGAD reduced from baseline over 1 year of treatment with tofacitinib, and RA efficacy outcomes were generally similar in patients with/without baseline pMDD/pGAD. |

| These findings suggest that effective treatment of underlying RA may lead to improvements in depression and anxiety; specially designed studies using gold-standard diagnostic tools would be warranted to investigate this further. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a video abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24250543.

Introduction

The prevalence of depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is estimated to range from 17% [1, 2] to 55% [3], which is notably higher than the global prevalence of 5% reported in the general population [4]. Moreover, the prevalence of concomitant anxiety in patients with RA and depression is also high at approximately 22% [5], although levels of anxiety may vary across the RA disease course [6].

Depression and RA have a complex bidirectional relationship [7–9]. Reasons for the high prevalence of depression in RA may reflect the chronic nature of the disease, as well as the negative effect of pain and fatigue on patients’ functioning [8]. Furthermore, an association between the severity of depression and disease activity has also been reported [8]. Indeed, the presence of depression and anxiety in patients with RA can lead to worsening of disease activity, with an increased risk of disease flares and a reduced likelihood of remission [7, 10]. Importantly, the presence of depression in patients with RA contributes to worsened medication adherence, quality of life, and functional capacity [8, 11–14].

The mechanisms underlying the association between depression and RA are not fully understood; however, there are common pathophysiologic features present in both diseases [15]. For example, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6, interleukin-17, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, are involved in the pathophysiology of RA and may be associated with depressive symptoms in patients with RA [8, 16]. The activation of intracellular signaling mechanisms by pro-inflammatory mediators may provide a link between immune-related diseases and mood disorders [9].

Several methods are available to diagnose depression, including the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which is the gold-standard diagnostic tool, and patient-reported outcomes [2]. One such patient-reported outcome is the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) that assesses general health status and wellbeing. Although not validated against the gold-standard DSM, a threshold score of ≤ 38 in the SF-36 Mental Component Summary (MCS) score has been used as an identifier of probable major depressive disorder (pMDD) and/or probable generalized anxiety disorder (pGAD), hereafter referred to as pMDD/pGAD, in patients with RA [17].

Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor for the treatment of RA. To date, evidence for the impact of tofacitinib on depression and anxiety in patients with RA is limited. This post hoc analysis, therefore, assessed the prevalence of pMDD/pGAD in clinical trials of tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily (BID) in patients with moderate to severe RA using an SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38 to define the presence of pMDD/pGAD, and evaluated the efficacy of tofacitinib stratified by baseline pMDD/pGAD status.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was a post hoc analysis of pooled data from five phase 3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [ORAL Step (NCT00960440), ORAL Scan (NCT00847613), ORAL Solo (NCT00814307), ORAL Sync (NCT00856544), and ORAL Standard (NCT00853385)], and one phase 3b/4 RCT [ORAL Strategy (NCT02187055)]. Patients with RA were treated with tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID, adalimumab 40 mg once every 2 weeks [only in ORAL Standard (adalimumab included as active comparator; study not designed for non-inferiority or superiority comparisons between tofacitinib and adalimumab) and ORAL Strategy (adalimumab included as active control)], or placebo. All treatments were taken in combination with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (with the exception of ORAL Solo and one arm in ORAL Strategy), specifically methotrexate in ORAL Scan, ORAL Standard, ORAL Step, and ORAL Strategy.

Full details of each study have been published previously [18–23] and are summarized in Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material. Briefly, eligible patients were aged ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of active moderate to severe RA, according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1987 Revised Criteria [24]. Patients had a prior inadequate response to a TNF inhibitor (TNFi) (ORAL Step), methotrexate (ORAL Scan, ORAL Standard, and ORAL Strategy), or ≥ 1 conventional synthetic DMARD or biologic DMARD (ORAL Solo and ORAL Sync).

All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Council for Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and were approved by the institutional review board and/or independent ethics committee for each study center. All patients provided written informed consent. No further ethical approval was required for this post hoc analysis in accordance with the policies of our institutions.

Assessments

Patients with a non-missing baseline SF-36 MCS score were included in this post hoc analysis. A threshold of ≤ 38 in SF-36 MCS score was used to define the presence of pMDD/pGAD in these patients.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics were stratified by baseline pMDD/pGAD status. The following outcomes were reported for each treatment group at months 3, 6, 9, and 12: change from baseline in SF-36 MCS score and the percentage of patients with pMDD/pGAD (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38) over time, in those with baseline pMDD/pGAD. ACR 20/50/70 response rates (the proportion of patients with 20/50/70% improvement in ACR criteria), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, ESR [DAS28-4(ESR)] remission rates (< 2.6), and change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), and Pain [visual analog scale (VAS)] were estimated at months 3, 6, and 12, and compared within treatment groups by baseline pMDD/pGAD status.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic and baseline characteristics data were analyzed descriptively. Binary endpoints were assessed using logistic regression models fit by month, with fixed effects of treatment (including adalimumab and placebo), baseline pMDD/pGAD status (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38 or > 38), treatment-by-baseline-status interaction, study (ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo, ORAL Sync, ORAL Standard, ORAL Step, and ORAL Strategy), geographic region (USA, Canada/Europe, Latin America, and other), and anti-depressant/anti-anxiety medication use (yes or no) on day 1. Missing responses were imputed as failures but only for the duration of the contributing study (e.g., 6 months for ORAL Solo). Odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p values were calculated.

Continuous endpoints were analyzed using a longitudinal mixed-effects linear model, applying the same effects as the logistic regression model, with month as the main effect, and two- and three-way interactions involving month, treatment, and baseline status; also included as an effect was baseline value of the dependent variable. Compound symmetry was used to model covariance. Missing data due to ‘missing at random’ were implicitly imputed by this modeling approach. Least squares (LS) mean changes from baseline, 95% CIs, and p values were calculated.

For both binary- and continuous-endpoint models, for those patients randomized to receive placebo who may have advanced to tofacitinib after month 3, only true placebo observations were included. For the continuous-endpoint models, all visits that a patient achieved were otherwise included.

There was no correction for multiple comparisons; p values are therefore descriptive, with p < 0.05 noted as significant.

Results

Patients

In total, 4404 patients were included in this post hoc analysis; of these, 1953, 1198, 581, and 672 patients received tofacitinib 5 mg BID, tofacitinib 10 mg BID, adalimumab, and placebo, respectively (Table 1). The patient population was obtained from the full analysis sets of each study, excluding 12 patients (0.3%) who had missing SF-36 MCS scores at baseline. Baseline pMDD/pGAD (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38) was reported by 870 (44.5%), 477 (39.8%), 264 (45.4%), and 263 (39.1%) patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg BID, tofacitinib 10 mg BID, adalimumab, and placebo, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics, stratified by treatment group and baseline pMDD/pGAD (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38) status

| SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38 (baseline pMDD/pGAD) | SF-36 MCS score > 38 (no baseline pMDD/pGAD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 870) | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID (N = 477) | Adalimumab 40 mg Q2W (N = 264) | Placebo (N = 263) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 1083) | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID (N = 721) | Adalimumab 40 mg Q2W (N = 317) | Placebo (N = 409) | |

| Age, years | 51.5 (12.0) | 51.4 (11.5) | 50.3 (12.8) | 52.9 (11.5) | 52.2 (12.4) | 53.3 (11.7) | 52.2 (12.8) | 52.2 (12.3) |

| Age > 65 years, n (%) | 102 (11.7) | 48 (10.1) | 33 (12.5) | 36 (13.7) | 145 (13.4) | 97 (13.5) | 45 (14.2) | 53 (13.0) |

| Female, n (%) | 756 (86.9) | 422 (88.5) | 224 (84.8) | 220 (83.7) | 880 (81.3) | 592 (82.1) | 249 (78.5) | 325 (79.5) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| White | 605 (69.5) | 293 (61.4) | 203 (76.9) | 166 (63.1) | 710 (65.6) | 446 (61.9) | 234 (73.8) | 272 (66.5) |

| Asian | 172 (19.8) | 121 (25.4) | 27 (10.2) | 71 (27.0) | 224 (20.7) | 182 (25.2) | 40 (12.6) | 89 (21.8) |

| Black | 32 (3.7) | 12 (2.5) | 7 (2.7) | 9 (3.4) | 40 (3.7) | 23 (3.2) | 14 (4.4) | 15 (3.7) |

| Other | 61 (7.0) | 51 (10.7) | 27 (10.2) | 17 (6.5) | 109 (10.1) | 70 (9.7) | 29 (9.1) | 33 (8.1) |

| Region, n (%) | ||||||||

| Canada/Europe | 351 (40.3) | 185 (38.8) | 130 (49.2) | 86 (32.7) | 380 (35.1) | 233 (32.3) | 139 (43.8) | 159 (38.9) |

| Latin America | 172 (19.8) | 75 (15.7) | 61 (23.1) | 43 (16.3) | 192 (17.7) | 105 (14.6) | 50 (15.8) | 53 (13.0) |

| USA | 146 (16.8) | 86 (18.0) | 33 (12.5) | 60 (22.8) | 233 (21.5) | 169 (23.4) | 67 (21.1) | 100 (24.4) |

| Asia/Australia/Israel/South Africa | 201 (23.1) | 131 (27.5) | 40 (15.2) | 74 (28.1) | 278 (25.7) | 214 (29.7) | 61 (19.2) | 97 (23.7) |

| Duration of RA, years | 8.1 (7.1) | 8.5 (7.4) | 8.5 (7.5) | 9.7 (8.9) | 8.8 (8.3) | 9.5 (8.7) | 7.9 (7.3) | 9.0 (8.1) |

| Anti-depressant or anti-anxiety medication use on day 1, n (%) | 64 (7.4) | 37 (7.8) | 11 (4.2) | 25 (9.5) | 53 (4.9) | 44 (6.1) | 16 (5.1) | 19 (4.7) |

| Corticosteroid use on day 1, n (%) | 520 (59.8) | 282 (59.1) | 154 (58.3) | 164 (62.4) | 631 (58.3) | 399 (55.3) | 179 (56.5) | 225 (55.0) |

| DAS28-4 (ESR) | 6.7 (0.9) | 6.7 (0.9) | 6.7 (0.9) | 6.6 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.2 (0.9) | 6.3 (1.0) |

| CDAI | 40.9 (12.2) | 39.6 (12.5) | 40.8 (13.4) | 40.2 (13.2) | 35.9 (12.3) | 35.6 (12.5) | 35.3 (11.8) | 35.4 (12.3) |

| HAQ-DI | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| CRP, mg/L | 19.2 (24.3) | 19.4 (27.2) | 19.1 (25.1) | 17.5 (18.7) | 16.6 (19.6) | 16.2 (18.7) | 15.1 (18.4) | 15.1 (19.1) |

| FACIT-F total score | 21.4 (8.8) | 22.1 (8.9) | 21.4 (8.6) | 22.9 (9.3) | 32.8 (9.0) | 33.2 (9.2) | 32.3 (8.7) | 33.2 (9.5) |

| Pain (VAS) | 66.9 (21.3) | 66.2 (20.5) | 64.4 (21.8) | 66.1 (21.6) | 54.6 (22.1) | 54.6 (23.6) | 54.7 (22.0) | 52.5 (22.1) |

| MOS Sleep scale | 51.6 (18.7) | 50.8 (18.1) | 53.8 (15.9) | 51.4 (19.2) | 34.7 (17.8) | 35.1 (17.4) | 34.5 (17.9) | 36.0 (17.9) |

| SF-36 PCS | 31.6 (6.8) | 31.9 (6.1) | 31.5 (6.9) | 31.6 (6.6) | 32.7 (8.4) | 32.8 (8.5) | 32.6 (7.5) | 33.2 (8.6) |

| SF-36 MCS | 29.8 (6.4) | 30.3 (6.1) | 30.1 (6.1) | 30.1 (6.3) | 48.7 (7.6) | 49.4 (7.6) | 48.4 (7.6) | 49.5 (7.7) |

Data are reported as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Data were pooled from five phase 3 RCTs and one phase 3b/4 RCT of tofacitinib in patients with RA

BID twice daily, CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, CRP C-reactive protein, DAS28-4(ESR) Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, FACIT-F Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, MCS Mental Component Summary, MOS Medical Outcomes Study, n number of patients with specific characteristic, N number of evaluable patients, PCS Physical Component Summary, pGAD probable generalized anxiety disorder, pMDD probable major depressive disorder, Q2W once every 2 weeks, RA rheumatoid arthritis, RCT randomized controlled trial, SF-36 Short Form-36 Health Survey, VAS visual analog scale

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics of patients stratified by baseline pMDD/pGAD are presented in Table 1. In general, demographic characteristics were similar across treatment groups and in patients with versus without pMDD/pGAD. However, at baseline, patients with pMDD/pGAD had higher CRP levels and worse disability (according to HAQ-DI scores), fatigue (according to FACIT-F scores), pain [according to Pain (VAS)], and sleep (according to Medical Outcomes Study Sleep scale) than patients without pMDD/pGAD (Table 1). In general, more patients with pMDD/pGAD were using anti-depressant or anti-anxiety medications on day 1 of treatment (Table 1).

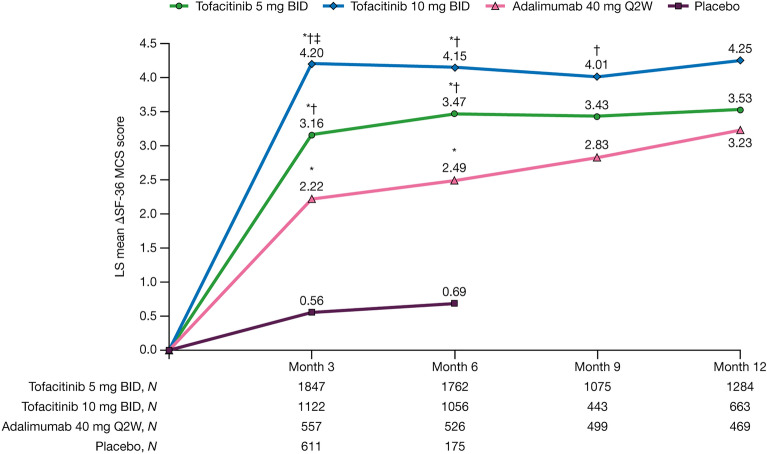

Efficacy Outcomes

SF-36 MCS scores increased from baseline over time to month 12 in all active treatment groups (Fig. 1). Increases in SF-36 MCS scores were significantly greater in patients receiving tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID or adalimumab versus placebo at month 3 and at month 6 (last placebo-controlled time point). Improvements in SF-36 MCS scores from baseline were significantly greater with both tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID compared with adalimumab at months 3 and 6, and with tofacitinib 10 mg BID versus adalimumab at month 9. Change in SF-36 MCS from baseline was significantly higher with tofacitinib 10 mg BID versus tofacitinib 5 mg BID at month 3.

Fig. 1.

Change from baseline in SF-36 MCS scores to month 12. *p < 0.05 versus placebo; †p < 0.05 versus adalimumab; ‡p < 0.05 versus tofacitinib 5 mg BID in difference in LS mean. Data were pooled from five phase 3 RCTs and one phase 3b/4 RCT of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. Patients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID at month 3 or month 6. Higher SF-36 MCS scores represent better mental health. Δ change from baseline, BID twice daily, LS least squares, MCS Mental Component Summary, N number of evaluable patients, Q2W once every 2 weeks, RCT randomized controlled trial, SF-36 Short Form-36 Health Survey

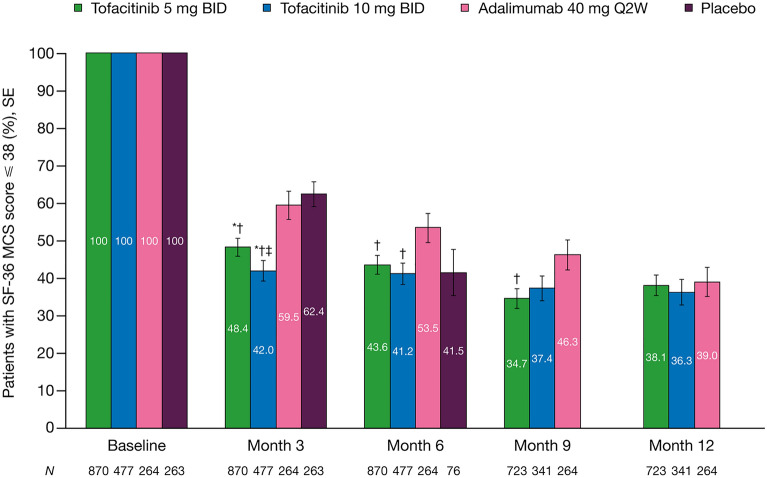

The percentage of patients with baseline pMDD/pGAD (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38) who continued to have pMDD/pGAD was reduced in all treatment groups over time (Fig. 2). The percentage of patients with pMDD/pGAD was significantly lower with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID versus adalimumab at months 3, 6, and 9 (tofacitinib 5 mg BID only at month 9) (Fig. 2). Odds ratios (95% CI) with tofacitinib 5 mg BID were 0.64 (0.48–0.85) at month 3, 0.67 (0.50–0.90) at month 6, and 0.62 (0.46–0.83) at month 9; odds ratios (95% CI) with tofacitinib 10 mg BID were 0.49 (0.35–0.70) at month 3 and 0.61 (0.43–0.86) at month 6. The proportion of patients with pMDD/pGAD in the tofacitinib 5 mg BID (48.4%) and 10 mg BID (42.0%) groups was significantly lower versus placebo (62.4%) at month 3 [odds ratio (95% CI) 0.56 (0.42–0.76) and 0.44 (0.32–0.60), respectively; both p < 0.05].

Fig. 2.

Percentage of patients with pMDD/pGAD (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38) over time, in those with baseline pMDD/pGAD (baseline SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38). *p < 0.05 versus placebo; †p < 0.05 versus adalimumab; ‡p < 0.05 versus tofacitinib 5 mg BID in odds ratio (not shown). Data were pooled from five phase 3 RCTs and one phase 3b/4 RCT of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. Patients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID at month 3 or month 6. BID twice daily, MCS Mental Component Summary, N number of evaluable patients, pGAD probable generalized anxiety disorder, pMDD probable major depressive disorder, Q2W once every 2 weeks, RCT randomized controlled trial, SE standard error, SF-36 Short Form-36 Health Survey

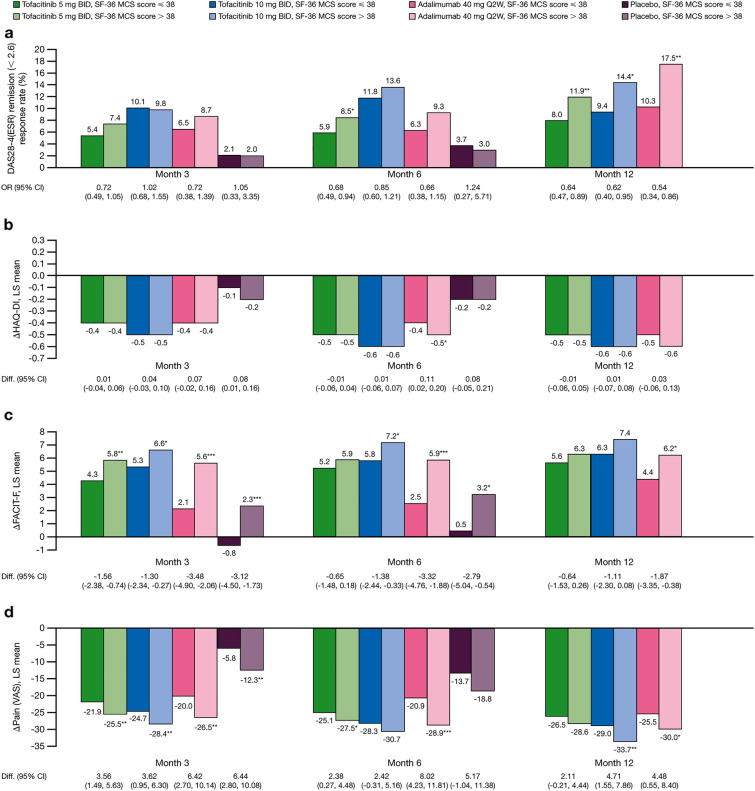

ACR20/50/70 responses were generally similar between active treatment groups at each time point and within treatment groups through month 12, irrespective of baseline pMDD/pGAD status (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38 or > 38, respectively) (Fig. 3a–c). At month 3, rates of DAS28-4(ESR) remission (< 2.6) by baseline pMDD/pGAD status were similar within each treatment group regardless of pMDD/pGAD status (Fig. 4a). DAS28-4(ESR) remission rates were significantly greater in patients without versus with baseline pMDD/pGAD at month 6 with tofacitinib 5 mg BID (p < 0.05) and at month 12 with tofacitinib 5 mg BID (p < 0.01), tofacitinib 10 mg BID (p < 0.05), and adalimumab (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4a). LS mean change from baseline in HAQ-DI was generally similar regardless of baseline pMDD/pGAD status in patients receiving tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID and adalimumab through month 12; however, adalimumab treatment demonstrated significant improvements in HAQ-DI in patients without versus with baseline pMDD/pGAD at month 6 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4b). At month 3, all treatments were associated with significantly greater LS mean changes in FACIT-F scores in patients without versus with baseline pMDD/pGAD, a trend that was also observed at month 6 in the tofacitinib 10 mg BID, adalimumab, and placebo arms, and at month 12 for adalimumab (Fig. 4c). Similarly, in all treatment arms, patients without versus with baseline pMDD/pGAD demonstrated significant improvements in Pain (VAS) scores at month 3; an effect that was also evident at month 6 for tofacitinib 5 mg BID and adalimumab, and at month 12 for tofacitinib 10 mg BID and adalimumab (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of a ACR20, b ACR50, and c ACR70 response ratesa between patients with versus without baseline pMDD/pGAD (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38 versus > 38b) at months 3, 6, and 12, stratified by treatment group. Data were pooled from five phase 3 RCTs and one phase 3b/4 RCT of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. Patients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID at month 3 or month 6. aLogistic regression models were fit by month. The models included fixed effects of treatment, baseline pMDD/pGAD status, treatment-by-baseline-status interaction, study, geographic region, and anti-depressant/anti-anxiety medication use on day 1. Missing responses were imputed as failures. For patients randomized to a placebo sequence in a study where they may have advanced to tofacitinib post-month 3, only true placebo observations were included in the model. bBaseline pMDD/pGAD was defined by SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38. ACR American College of Rheumatology, BID twice daily, MCS Mental Component Summary, OR odds ratio, pGAD probable generalized anxiety disorder, pMDD probable major depressive disorder, Q2W once every 2 weeks, RCT randomized controlled trial, SF-36 Short Form-36 Health Survey

Fig. 4.

Comparison of a DAS28-4(ESR)-defined remission ratesa, b change from baseline in HAQ-DIb, c change from baseline in FACIT-Fb, and d change from baseline in Pain (VAS)b between patients with versus without baseline pMDD/pGAD (SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38 versus > 38c) at months 3, 6, and 12, stratified by treatment group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 for patients with baseline SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38 versus > 38. Data were pooled from five phase 3 RCTs and one phase 3b/4 RCT of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. Patients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID at month 3 or month 6. aLogistic regression models were fit by month. The models included fixed effects of treatment, baseline pMDD/pGAD status, treatment-by-baseline-status interaction, study, geographic, and anti-depressant/anti-anxiety medication use on day 1. Missing responses were imputed as failures. For patients randomized to a placebo sequence in a study where they may have advanced to tofacitinib post-month 3, only true placebo observations were included in the model. bA mixed-effects linear model was fit, applying the same effects as in the logistic regression models, except the model was longitudinal and included the effect of month (months 3, 6, and 12) as a main effect, and two- and three-way interactions involving month, treatment, and baseline status, along with baseline value of the dependent variable. Patients were included as a random effect. Missing data were implicitly imputed by this modeling approach. cBaseline pMDD/pGAD was defined by SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38. Δ change from baseline, BID twice daily, DAS28-4(ESR) Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, Diff. difference, FACIT-F Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, LS least squares, MCS Mental Component Summary, OR odds ratio, pGAD probable generalized anxiety disorder, pMDD probable major depressive disorder, Q2W once every 2 weeks, RCT randomized controlled trial, SF-36 Short Form-36 Health Survey, VAS visual analog scale

Discussion

This post hoc analysis of pooled data from five phase RCTs and one phase 3b/4 RCT assessed the prevalence of pMDD/pGAD among patients with moderate to severe RA receiving tofacitinib and assessed the efficacy of tofacitinib on RA outcomes in patients stratified by pMDD/pGAD based on SF-36 MCS score.

In this study, we considered a SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38 to indicate the presence of pMDD/pGAD. This cut-off value has previously been found to have 87.5% sensitivity, 80.3% specificity, and 82.8% accuracy to identify either pMDD or pGAD in patients with RA [17]. Using this cut-off, 39.1–45.4% of patients in our analysis had pMDD/pGAD at baseline, which is consistent with the prevalence of up to 55% seen in other studies of RA [1–3]. As may be expected, patients with moderate to severe RA and pMDD/pGAD had higher CRP levels and worse disability, fatigue, pain, and sleep at baseline than patients without pMDD/pGAD. Our results also demonstrate that through month 6, improvements or increases in SF-36 MCS scores were greater in patients receiving tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID versus adalimumab or placebo, with numerical improvements for tofacitinib versus adalimumab sustained through month 12. It is important to note, however, that only two of the six RCTs in the analysis (ORAL Standard and ORAL Strategy) included an adalimumab treatment arm, and neither of these studies were designed for non-inferiority or superiority comparisons between tofacitinib and adalimumab for SF-36 MCS as an outcome measure. Notably, the minimum clinically important difference in SF-36 MCS is estimated to be at least 2.5 points [25]; in this analysis, mean improvements from baseline exceeded this value at all time points in patients receiving either dose of tofacitinib (although they were numerically greater with 10 mg BID than with 5 mg BID). Furthermore, in patients receiving tofacitinib, the percentage of patients with SF-36 MCS scores ≤ 38 (i.e., identified as having pMDD/pGAD) was consistently reduced during the treatment period, with an approximate reduction from baseline of 60% after month 6 that was similar between doses.

The efficacy of tofacitinib and adalimumab according to ACR20/50/70 response rates and LS mean change from baseline in HAQ-DI was generally similar in patients with and without baseline pMDD/pGAD through month 12. Elevated levels of the inflammatory marker ESR may be associated with the risk of depression in RA [8], and in our analysis, DAS28-4(ESR) remission (< 2.6) rates were significantly greater in patients without versus with baseline pMDD/pGAD at month 6 for patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg BID and at month 12 for patients receiving tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID and adalimumab. Compared with those with baseline pMDD/pGAD, patients without baseline pMDD/pGAD also demonstrated greater LS mean changes in FACIT-F and Pain (VAS) scores through month 12 in the adalimumab treatment arm, and generally through month 6 in the tofacitinib treatment arms (and up to month 12 for Pain in the tofacitinib 10 mg BID arm). This shows the debilitating impact of comorbid depression or anxiety on two important patient-reported parameters in RA. It is interesting to note that differences between patients with versus without pMDD/pGAD in FACIT-F and Pain (VAS) changes from baseline were most pronounced for patients in the adalimumab and placebo treatment groups. The effects of tofacitinib were comparatively more consistent regardless of pMDD/pGAD status, with numerically larger improvements generally, but not uniformly, observed in comparison with adalimumab in patients with pMDD/pGAD.

Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6, are common to patients with RA [16] and those with depression [26]. Peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines are able to cross the blood–brain barrier, thereby activating cerebral inflammatory signaling pathways [27] and impairing synaptic plasticity at morphological and functional levels [28]. Tofacitinib has also been shown to penetrate the blood–brain barrier in mice [29], although evidence of this occurring in humans is indirect and limited to a small study of eight patients with autoimmune encephalitis [30]. It is unlikely that adalimumab, as a large protein molecule, would cross the blood–brain barrier [31]. A potential role for JAK inhibitors such as tofacitinib in the downregulation of central pain processing pathways may be through the blockade of interleukin-6 via selective targeting of the JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway [32, 33]. The JAK-STAT pathway has been implicated in the modulation of nociception, which may suggest an additional mechanism for JAK inhibitors to reduce pain, beyond their effects on inflammation [34]. Although this post hoc analysis could not assess mechanism or causality, it is possible that tofacitinib may modulate the relationship between the central nervous system and peripheral inflammation in patients with RA and neuropsychiatric comorbidities [35].

A recent post hoc analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of pMDD/pGAD on the efficacy of tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID in patients with psoriatic arthritis, using data from two phase 3 trials (OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond) [36]. Approximately 46% of patients with psoriatic arthritis had pMDD/pGAD at baseline. Consistent with this analysis in patients with RA, tofacitinib treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis was associated with reductions in pMDD/pGAD from baseline, although these were only numerically different from placebo [36]. Furthermore, at month 3, greater proportions of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg BID generally had improvements in efficacy outcomes, including FACIT-F and HAQ-DI, regardless of pMDD/pGAD status [36].

Several other studies have investigated the association between baseline depression and the impact of treatment with biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs in patients with RA. A non-interventional study assessing the impact of tocilizumab on depressive symptoms in patients with RA during routine daily care demonstrated improvements in depressive symptoms in approximately two-thirds of patients; however, consistent with this analysis, improvements in disease activity were generally seen regardless of the presence of baseline depression [37]. A meta-analysis of RCTs in patients with RA showed clinically significant improvements from baseline in mental health (SF-36 MCS scores) following JAK inhibitor monotherapy, particularly for tofacitinib, which exceeded improvements reported with other DMARDs [38]. Treatment with a TNFi in combination with methotrexate has also been shown to improve depressive symptoms in a double-blind, randomized trial in patients with RA [39, 40]. In contrast with our analysis, improved disease activity and functioning was observed in significantly more patients without than with baseline depressive symptoms [40].

A limitation of this analysis was that it was performed post hoc and individual studies were not designed to compare patients who were indicative or not indicative of pMDD/pGAD. Furthermore, the individual RCTs included in the pooled analysis were not designed to assess the efficacy of tofacitinib in patients stratified by pMDD/pGAD status. In addition, patients included in this analysis were identified as being at risk for MDD and GAD using SF-36 MCS scores, rather than through a confirmed clinical diagnosis. As such, future research is required to evaluate the correlation between RA and depression, and to replicate the findings using a gold-standard psychiatric interview against which to validate the use of SF-36 MCS score ≤ 38.

The analysis was also limited by the fact that a true placebo comparison in this analysis was only available up to month 3, as patients receiving placebo who were non-responders advanced to tofacitinib at month 3, with all remaining placebo patients advancing at month 6. As such, it is likely that the placebo group at month 6 included patients with improved signs and symptoms of RA and, therefore, the estimate is likely biased. No correction was made for multiple comparisons in these analyses; therefore, the results can only be considered as indicative and exploratory in nature. Finally, findings from analyses using clinical trial data may not be representative of real-world clinical practice, which may limit the clinical relevance of these results.

Conclusions

The results of this analysis demonstrated a high prevalence of pMDD/pGAD in patients with RA. The percentage of patients with pMDD/pGAD consistently reduced from baseline over one year of treatment with tofacitinib or adalimumab. RA efficacy outcomes were generally similar in patients with/without pMDD/pGAD. In patients with moderate to severe RA, treatment of the underlying condition may lead to improvements in depression and anxiety based on the SF-36 MCS. Specially designed studies using gold-standard diagnostic tools would be warranted to investigate this further.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in the ORAL Step, ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo, ORAL Sync, ORAL Standard, and ORAL Strategy clinical studies.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors would like to acknowledge Renato Guzman, Fundación Universitaria Juan N. Corpas e IDEARG, Bogotá, Colombia, for important contributions to this work. Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Karen Irving, PhD, CMC Connect, a division of IPG Health Medical Communications, and Karleen Nicholson, PhD, on behalf of CMC Connect, and was funded by Pfizer, New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022; 175: 1298–1304). Editorial support was provided by Eva Dekker, CMC Connect, and was funded by Pfizer, New York, NY, USA.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval of the version to be submitted.

Author Contributions

Gustavo Citera, Rakesh Jain, Fedra Irazoque, David Gruben, Lisy Wang, Lori Stockert, and Dario Ponce de Leon conceived and/or designed the study. Gustavo Citera, Fedra Irazoque, Hugo Madariaga, David Gruben, Lisy Wang, and Karina Santana acquired the data. Rakesh Jain, David Gruben, Lisy Wang, Karina Santana, Abbas Ebrahim, and Dario Ponce de Leon analyzed the data. All authors interpreted the data, drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer. Medical writing support was funded by Pfizer. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee for this article was also funded by Pfizer.

Data Availability

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Gustavo Citera has received speaker, adviser, and/or investigator fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Gema, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, and Sandoz. Rakesh Jain has received research grants from Allergan, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer Inc, Shire, and Takeda; consulting fees or other remuneration from Acadia, Alfasigma, Allergan, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Evidera, Impel, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Neos Therapeutics, Neurocrine Biosciences, Osmotica, Otsuka, Pamlab, Pfizer Inc, Shire, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva; and speaker fees from Alkermes, Allergan, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Neos Therapeutics, Neurocrine Biosciences, Otsuka, Pamlab, Pfizer Inc, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and Tris Pharmaceuticals. Fedra Irazoque has received speaker, adviser, and principal investigator fees from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pfizer Inc, Roche, and UCB. Hugo Madariaga declares no conflicts of interest. David Gruben, Lisy Wang, Lori Stockert, Karina Santana, Abbas Ebrahim, and Dario Ponce de Leon are employees and stockholders of Pfizer Inc.

Ethical Approval

All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Council for Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and were approved by the institutional review board and/or independent ethics committee for each study center. All patients provided written informed consent. No further ethical approval was required for this post hoc analysis in accordance with the policies of our institutions.

References

- 1.Peterson S, Piercy J, Blackburn S, Sullivan E, Karyekar CS, Li N. The multifaceted impact of anxiety and depression on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019;3:43. doi: 10.1186/s41927-019-0092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:2136–2148. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Englbrecht M, Alten R, Aringer M, et al. New insights into the prevalence of depressive symptoms and depression in rheumatoid arthritis—implications from the prospective multicenter VADERA II study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0217412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Depression fact sheet. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression. Accessed 7 Feb 2023.

- 5.Covic T, Cumming SR, Pallant JF, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence rates based on a comparison of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) and the Hospital, Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.VanDyke MM, Parker JC, Smarr KL, et al. Anxiety in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:408–412. doi: 10.1002/art.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallerand IA, Patten SB, Barnabe C. Depression and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019;31:279–284. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lwin MN, Serhal L, Holroyd C, Edwards CJ. Rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of mental health on disease: a narrative review. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7:457–471. doi: 10.1007/s40744-020-00217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu MC, Guo HR, Lin MC, Livneh H, Lai NS, Tsai TY. Bidirectional associations between rheumatoid arthritis and depression: a nationwide longitudinal study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20647. doi: 10.1038/srep20647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michelsen B, Kristianslund EK, Sexton J, et al. Do depression and anxiety reduce the likelihood of remission in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis? Data from the prospective multicentre NOR-DMARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1906–1910. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isnardi CA, Capelusnik D, Schneeberger EE, et al. Depression is a major determinant of functional capacity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27:S180–S185. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hattori Y, Katayama M, Kida D, Kaneko A. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Score is an independent factor associated with the EuroQoL 5-Dimensional Descriptive System in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018;24:308–312. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matcham F, Norton S, Scott DL, Steer S, Hotopf M. Symptoms of depression and anxiety predict treatment response and long-term physical health outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:268–278. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturgeon JA, Finan PH, Zautra AJ. Affective disturbance in rheumatoid arthritis: psychological and disease-related pathways. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:532–542. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nerurkar L, Siebert S, McInnes IB, Cavanagh J. Rheumatoid arthritis and depression: an inflammatory perspective. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:164–173. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li YC, Chou YC, Chen HC, Lu CC, Chang DM. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-17 are related to depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:980–985. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matcham F, Norton S, Steer S, Hotopf M. Usefulness of the SF-36 Health Survey in screening for depressive and anxiety disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:224. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1083-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C, et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:451–460. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61424-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Heijde D, Tanaka Y, Fleischmann R, et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: twelve-month data from a twenty-four-month phase III randomized radiographic study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:559–570. doi: 10.1002/art.37816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:508–519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:495–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kremer J, Li Z-G, Hall S, et al. Tofacitinib in combination with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:253–261. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-4-201308200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleischmann R, Mysler E, Hall S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy, tofacitinib with methotrexate, and adalimumab with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (ORAL Strategy): a phase 3b/4, double-blind, head-to-head, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:457–468. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strand V, Boers M, Idzerda L, et al. It's good to feel better but it's better to feel good and even better to feel good as soon as possible for as long as possible. Response criteria and the importance of change at OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1720–1727. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiat. 2010;67:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenger A, Calabrese P. Comparing underlying mechanisms of depression in multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Integr Neurosci. 2021;20:765–776. doi: 10.31083/j.jin2003081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khairova RA, Machado-Vieira R, Du J, Manji HK. A potential role for pro-inflammatory cytokines in regulating synaptic plasticity in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:561–578. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709009924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fukuyama T, Tschernig T, Qi Y, Volmer DA, Baumer W. Aggression behaviour induced by oral administration of the Janus-kinase inhibitor tofacitinib, but not oclacitinib, under stressful conditions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;764:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang Y, Lee WJ, Lee HS, Chu K, Lee SK, Lee ST. Tofacitinib treatment for refractory autoimmune encephalitis. Epilepsia. 2021;62:e53–e59. doi: 10.1111/epi.16848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagarde S, Villeneuve N, Trébuchon A, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy (adalimumab) in Rasmussen's encephalitis: an open pilot study. Epilepsia. 2016;57:956–966. doi: 10.1111/epi.13387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrington R, Al Nokhatha SA, Conway R. JAK inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: an evidence-based review on the emerging clinical data. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:519–531. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S219586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Busch-Dienstfertig M, González-Rodríguez S. IL-4, JAK-STAT signaling, and pain. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e27638. doi: 10.4161/jkst.27638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crispino N, Ciccia F. JAK/STAT pathway and nociceptive cytokine signalling in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39:668–675. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/e7ayu8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Süß P, Rothe T, Hoffmann A, Schlachetzki JCM, Winkler J. The joint-brain axis: insights from rheumatoid arthritis on the crosstalk between chronic peripheral inflammation and the brain. Front Immunol. 2020;11:612104. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.612104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gossec L, Citera G, Sellas-Fernández A, Gruben DC, Valderrama M, Gómez S. Tofacitinib treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis and probable depression and/or anxiety: a post hoc analysis of two Phase 3 clinical trials [abstract] Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(Suppl 1):782. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behrens F, Burmester GR, Feuchtenberger M, et al. Characterisation of depressive symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tocilizumab during routine daily care. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40:551–559. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/yu55rd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shamail GMH, Haridoss M, Natarajan M, Joshua V, Bagepally BS. Association between Janus kinase inhibitors therapy and mental health outcome in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Ther. 2022;9:313–329. doi: 10.1007/s40744-021-00409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kekow J, Moots RJ, Emery P, et al. Patient-reported outcomes improve with etanercept plus methotrexate in active early rheumatoid arthritis and the improvement is strongly associated with remission: the COMET trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:222–225. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kekow J, Moots R, Khandker R, Melin J, Freundlich B, Singh A. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and their association with clinical remission among patients with moderate-to-severe active early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:401–409. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.