Abstract

Pneumococcal adherence to alveolar epithelial cells and nasopharyngeal epithelial cells has been well characterized. However, the interaction of Streptococcus pneumoniae with bronchial epithelial cells has not been studied. We have now shown that pneumococci bind specifically to a human bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B cells). Pneumococci adhered to BEAS-2B cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that the bronchial epithelium may serve as an additional site of attachment for pneumococci and demonstrate the utility of the BEAS-2B cell line for studying mechanisms of pneumococcal infection.

The gram-positive pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of pneumonia, otitis media, septicemia, and meningitis (17, 18). The adherence of S. pneumoniae to eukaryotic cells is the initial step in colonization and infection of the host. In some cases this results in subsequent mucosal invasion and systemic disease. The primary site of colonization for pneumococci is the nasopharynx. Otitis media results from pneumococcal migration from the nasopharynx into the middle ear via the eustachian tube. Bacteria colonizing the nasopharynx may also be aspirated into the alveoli of the lower respiratory tract and cause pneumonia. In some cases, pneumococci may penetrate the mucosal epithelium of the nasopharynx or lung and enter the vascular compartment, causing sepsis and meningitis (4).

The ability of S. pneumoniae to adhere to specific sites on host tissues has been investigated by using various cell culture models, such as human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells (1) and alveolar type II epithelial cells (5), as well as human vascular endothelial cells (6). However, the ability of S. pneumoniae to adhere to bronchial epithelial cells, which pneumococci may encounter as they pass from the nasopharynx to the lower respiratory tract, has not been demonstrated. In this study we investigated the ability of pneumococci to attach to bronchial cells by using a well-characterized, human bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B) (8). Earlier studies have shown that these cells express bronchial-cell-specific characteristics (7, 8, 13).

S. pneumoniae strains used in this study were D39 (serotype 2) (2) and its unencapsulated derivative Rx1 (16), which were provided by H. R. Masure (The Rockefeller University, New York, N.Y.), as well as two clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae (serotypes 4 and 14), which were provided by I. Aaberge (National Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway). For adherence tests, pneumococci were grown to mid-logarithmic phase (optical density at 620 nm, 0.4 to 0.6) in Todd-Hewitt broth with 0.5% yeast extract (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C, centrifuged, and resuspended in bronchial tracheal epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM; Clonetics Corp., San Diego, Calif.) at a density ranging from 1.5 × 107 to 3.6 × 107 CFU/ml. BEAS-2B (12, 13), a transformed human bronchial epithelial cell line (ATCC CRL-9609), was passaged in coated (10) tissue culture flasks in serum-free BEGM without antibiotics at 37°C in 5% CO2. The attachment of S. pneumoniae to BEAS-2B cells was assessed by a 24-well tissue culture plate (Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) adherence assay (15). BEAS-2B cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and grown to confluence (approximately 5 × 105 cells/well). One-milliliter aliquots of bacterial suspensions (adjusted to a final concentration of 2 × 107 CFU/ml) were inoculated onto washed epithelial cell monolayers and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The monolayers were then washed five times with sterile HEPES-buffered saline (pH 7.4) (HBS; Clonetics Corp.), detached by treatment with 0.25% trypsin–0.01% EDTA–0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidine (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.) for 10 min at 37°C, and lysed with 0.025% Triton X-100. The total number of adherent bacteria was determined by serial dilution in HBS and quantitative culture on BBL tryptic soy agar plates containing 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.). The viability of BEAS-2B cells was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion and was found to be ≥95% for each experiment. Differences between groups were tested by Tukey’s studentized range test.

All four S. pneumoniae strains tested were able to bind to bronchial epithelial cells in vitro (Table 1). The unencapsulated Rx1 strain demonstrated the highest level of adherence to human BEAS-2B cells. Encapsulated isogenic strain D39 (serotype 2) and the serotype 14 strain exhibited moderate levels of adherence, whereas the serotype 4 strain demonstrated relatively low levels of adherence to BEAS-2B cells. The adherence of Rx1 and serotype 14 pneumococci to BEAS-2B cells was demonstrated to be time-dependent (with an inoculum of approximately 2 × 107 CFU/well), reaching a plateau within 30 min (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Adherence of S. pneumoniae strains to BEAS-2B cells

| Strain | Serotype | Adherencea (CFU/well) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical isolate | 4 | 415 ± 92 |

| Clinical isolate | 14 | 8,340 ± 1,258 |

| D39 | 2 | 6,030 ± 650 |

| Rx1 | Unencapsulated | 39,500 ± 6,364 |

Adherence was determined after BEAS-2B monolayers (5 × 105 cells/well) were incubated at a bacterial cell/epithelial cell ratio of approximately 40:1 for each of the indicated strains. The total number of pneumococci in each well was determined by quantitative culture. Data are the means ± standard deviations for triplicate wells from a representative experiment of three similar experiments.

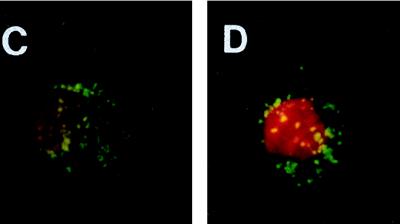

Specific pneumococcal binding to BEAS-2B cells was further confirmed by a novel flow cytometric method (9, 11). Pneumococcal adherence to A549, a human alveolar carcinoma (type II pneumocyte) cell line (ATCC CRL-185), was used as a positive control for these experiments given that pneumococci have been shown to bind to these cells in other assay systems (5). A549 cells were cultured in nutrient mixture Ham’s F-12K medium (Gibco Laboratories) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (BioWhittaker Inc., Walkersville, Md.) without antibiotics at 37°C in 5% CO2. Following their removal from the flask by incubation with 0.1% trypsin, epithelial cells were incubated at 37°C in spinner flasks (Bellco Glass Inc., Vineland, N.Y.) overnight. Pneumococci were harvested from overnight cultures on tryptic soy agar plates containing 5% sheep blood and were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; 1.0 mg/ml; Sigma Chemical Company) as previously described (6). For adherence assays, labeled pneumococci were incubated with 5 × 105 BEAS-2B or A549 cells at bacterial cell/epithelial cell ratios of 1,000:1 to 60:1. After gentle mixing for 30 min at 37°C, samples were assayed by flow cytometry with a Becton Dickinson FACStar Plus. Mean channel fluorescence was used as an indicator of FITC-labeled bacteria bound to viable BEAS-2B or A549 cells.

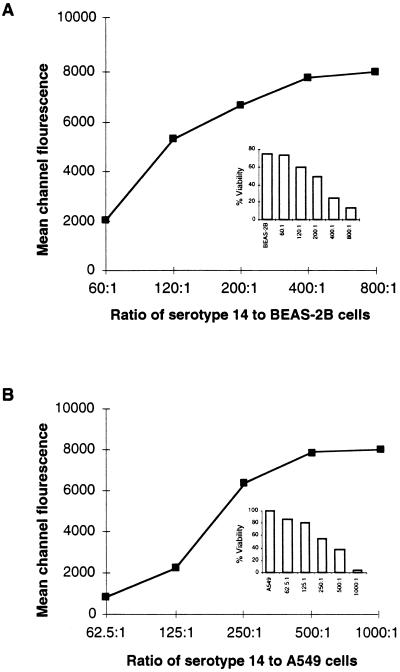

The attachment of FITC-labeled bacteria to BEAS-2B (Fig. 1A) or A549 (Fig. 1B) cells occurred in a dose-dependent and saturable manner. Fluorescence microscopy confirmed the attachment of pneumococci to the cell surfaces of BEAS-2B (Fig. 1C) or A549 cells (Fig. 1D). The viability of the epithelial cells was inversely proportional to the ratio of bacteria to cells, as determined by propidium iodide staining (2.5 μg; Boehringer Mannheim) (Fig. 1, insets). The dose-dependent attachment of serotype 14 pneumococci to BEAS-2B cells was confirmed by the 24-well tissue culture plate adherence assay described above. As the inoculum size increased, the number of organisms recovered increased, until saturation at approximately 2 × 108 CFU/well (data not shown). Similar saturation results were obtained with the unencapsulated Rx1 strain (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Adherence of serotype 14 pneumococci to BEAS-2B (A) and A549 (B) cells. Inset: percent viabilities of BEAS-2B and A549 cells. FITC-labeled serotype 14 pneumococci bound to BEAS-2B (C) or A549 (D) cells at a bacterial cell/epithelial cell ratio of 125:1. Green fluorescent pneumococci can be seen attached to the epithelial cell surface. For contrast, the nucleus of the epithelial cell was stained (red) with propidium iodide. Photographs were taken with a Nikon N6006 camera. Magnification, ×100.

As shown in Table 1, the unencapsulated S. pneumoniae strain Rx1 adhered to a much greater extent to bronchial epithelial cells than the encapsulated parental strain D39 (P < 0.05). This may be due to the fact that adhesins present on the S. pneumoniae surface normally shielded by the capsule are exposed in the unencapsulated strain and are available for binding to the cell surface. Furthermore, preliminary results from recent experiments have shown that the higher levels of adherence by S. pneumoniae may correlate with enhanced invasive capacity of bacteria. What relevance this may have to the pathogenesis of S. pneumoniae in the respiratory tract remains unclear.

Unlike respiratory pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae, that initiate infection in the nasopharynx and often descend into the bronchi causing bronchitis, pneumococci do not typically cause bronchial infections although they have been associated with a minority of cases of chronic bronchitis (3, 14). Nonetheless, pneumococci which migrate from the nasopharynx to the lower respiratory tract must traverse bronchial epithelial cells. Hence, bronchial cells may serve as transient, secondary sites for attachment by virulent pneumococci.

Our finding that pneumococci bind to human bronchial epithelial cells is significant in that understanding more about interactions between pneumococci and human epithelial cells of the respiratory tract may elucidate host-pathogen interactions involved in establishing pneumococcal infection in addition to those already defined. These studies may also aid in the identification of novel therapeutic intervention strategies to block pneumococcal infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Koenig for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson B, Dahmen J, Frejd T, Leffler H, Magnusson G, Noori G, Svanborg Eden C. Identification of an active disaccharide unit of a glycoconjugate receptor for pneumococci attaching to human pharyngeal epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 1983;158:559–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avery T O, MacLeod C M, McCarty M. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types. J Exp Med. 1944;79:137–158. doi: 10.1084/jem.79.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole, P. J. 1987. Significance of Haemophilus influenzae and other microorganisms for the pathogenesis and therapy of chronic respiratory infection. Infection 15(Suppl. 3):S99–S102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Cundell, D., H. R. Masure, and E. I. Tuomanen. 1995. The molecular basis of pneumococcal infection: a hypothesis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 21(Suppl. 3):S204–S212. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cundell D R, Tuomanen E I. Receptor specificity of adherence of Streptococcus pneumoniae to human type II pneumocytes and vascular endothelial cells in vitro. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:361–374. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geelan S, Bhattacharyya C, Tuomanen E. The cell wall mediates pneumococcal attachment to and cytopathology in human endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1538–1543. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1538-1543.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katoh Y, Stoner G D, McIntire K R, Hill T A, Anthony R, McDowell E M, Trump B F, Harris C C. Immunologic markers of human bronchial epithelial cells in tissue sections and in culture. JNCI. 1979;62:1177–1185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ke Y, Reddel R R, Gerwin B I, Miyashita M, McMenamin M, Lechner J F, Harris C C. Human bronchial epithelial cells with integrated SV40 virus T antigen genes retain the ability to undergo squamous differentiation. Differentiation. 1988;38:60–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1988.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langermann S, Palaszynki S, Barnhart M, Auguste G, Pinkner J S, Burlein J, Barren P, Koenig S, Leath S, Jones C H, Hultgren S J. Prevention of mucosal Escherichia coli infection by FimH-adhesin-based systemic vaccination. Science. 1997;276:607–611. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lechner J F, LaVeck M A. A serum-free method for culturing normal human bronchial epithelial cells at clonal density. J Tissue Cult Methods. 1985;9:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Walker D H. Characterization of rickettsial attachment to host cells by flow cytometry. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2030–2035. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2030-2035.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddel R R, Salghetti S E, Willey J C, Ohnuki Y, Ke Y, Gerwin B I, Lechner J F, Harris C C. Development of tumorigenicity in simian virus 40-immortalized human bronchial epithelial cell lines. Cancer Res. 1993;53:985–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddel R R, Ke Y, Gerwin B I, McMenamin M G, Lechner J F, Su R T, Brash D E, Park J B, Rhim J S, Harris C C. Transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells by infection with SV40 or adenovirus-12 SV40 hybrid virus, or transfection via strontium phosphate coprecipitation with plasmid containing SV40 early genes. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1904–1909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds H Y. Bacterial adherence to respiratory tract mucosa—a dynamic interaction leading to colonization. Semin Respir Infect. 1987;2:8–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubens C E, Smith S, Hulse M, Chi E Y, van Belle G. Respiratory epithelial cell invasion by group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5157–5163. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5157-5163.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoemaker N B, Guild W R. Destruction of low efficacy markers is a slow process occurring at a heteroduplex stage of transformation. Mol Gen Genet. 1974;128:283–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00268516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talbot U M, Paton A W, Paton J C. Uptake of Streptococcus pneumoniae by respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3772–3777. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3772-3777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuomanen E I, Austrian R, Masure H R. Pathogenesis of pneumococcal infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1280–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505113321907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]