Abstract

As a part of a larger, mixed-methods research study, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 21 adults with depressive symptoms to understand the role that past health care discrimination plays in shaping help-seeking for depression treatment and receiving preferred treatment modalities. We recruited to achieve heterogeneity of racial/ethnic backgrounds and history of health care discrimination in our participant sample. Participants were Hispanic/Latino (n = 4), non-Hispanic/Latino Black (n = 8), or non-Hispanic/Latino White (n = 9). Twelve reported health care discrimination due to race/ethnicity, language, perceived social class, and/or mental health diagnosis. Health care discrimination exacerbated barriers to initiating and continuing depression treatment among patients from diverse backgrounds or with stigmatized mental health conditions. Treatment preferences emerged as fluid and shaped by shared decisions made within a trustworthy patient–provider relationship. However, patients who had experienced health care discrimination faced greater challenges to forming trusting relationships with providers and thus engaging in shared decision-making processes.

Keywords: depression, mental health and illness, race, racism, social issues, qualitative, semi-structured interviews, psychiatry, United States of America

Introduction

Major depression carries the heaviest disability burden among mental and behavioral disorders (Murray et al., 2013) and reduces life expectancy by 7 to 11 years (Chesney et al., 2014). Only 37.6% of Whites and 25% of Black or Hispanic/Latino people who need access to mental health care ultimately receive treatment (Wells et al., 2001). Black and Hispanic/Latino populations are also more likely to receive inadequate treatment (Cook et al., 2014; Satcher, 2000), poorer quality of care (Satcher, 2000), and are less likely to remain in care (Fortuna et al., 2010). These disparities may partly explain why Black and Hispanic/Latino populations report mental health symptoms that are more severe, disabling (Williams et al., 2007), and persistent than Whites (Breslau et al., 2006). Despite efforts to improve key aspects of mental health care, such as access (Creedon & Cook, 2016; Huey et al., 2014; Lie et al., 2011), quality (Satcher, 2000), and cultural competence (Betancourt et al., 2014), treatment initiation disparities have grown (Cook et al., 2016; Creedon & Cook, 2016).

Depression Treatment Preferences and Racial/Ethnic Disparities

Research suggests that an important potential driver of racial/ethnic disparities in depression treatment may be differences in treatment preferences (Jung et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2011; Olfson & Marcus, 2009; Quiñones et al., 2014). Black and Hispanic/Latino populations are often offered treatments that do not match their preferences (Cardemil & Sarmiento, 2009; Dwight-Johnson et al., 2001; Ryan & Lauver, 2002; Swift & Callahan, 2009), which may lower engagement in care and lead to poorer depression treatment outcomes (Kwan et al., 2010). For example, Non-White primary care patients may find medications for depression treatment less acceptable than White patients, which may partly explain why Non-White patients access medication-based treatment less often (Cooper et al., 2003; Dwight-Johnson et al., 2000). However, underlying preferences are often not fully ascertained by medical providers and are less likely to be fully ascertained from people of color (Armstrong et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2002; Katz, 2001). Preferences to avoid certain treatments reflect personal, familial, or cultural values, but may also stem from prior experiences of low-quality treatment, unfair treatment, or discrimination toward oneself or others.

Preferred Depression Treatment and Discrimination

Historic and ongoing discrimination toward Black and Hispanic/Latino communities (Benuto et al., 2019; Casagrande et al., 2007; Corbie-Smith et al., 2002; Dovidio et al., 2008; Gaskin et al., 2009; Thomas, 2018) further exacerbates the mismatch between available and desired treatments. This discrimination is an integral component contributing to higher intrapersonal, interpersonal, and systematic stigma toward those with mental illness in these populations (Alvidrez et al., 2008; Clark et al., 2014; Martinez-Hume et al., 2017; Trivedi & Ayanian, 2006). Discrimination and stigma experienced by communities of color (Corbie-Smith et al., 2002) also contribute to an ongoing lack of trust in health care systems (Dovidio et al., 2008). For example, stigma partially mediates the relationship between Hispanic ethnicity and lower lifetime history of behavioral health service use (Benuto et al., 2019) and Latino-specific societal, community, and intrapersonal barriers to mental health care include immigration status, being made fun of by others, and external and internalized stigma from mental health diagnosis (Martinez Tyson et al., 2016). Even if structural barriers such as lack of insurance or access to medical providers are removed, remembering past experiences of discrimination or experiencing lower quality care in their geographic area may further influence treatment-seeking behaviors among people of color (Casagrande et al., 2007; Gaskin et al., 2009), and may result in preferring to avoid medical care except in an emergency. Yet, little is known about the role of past discrimination in influencing depression treatment preferences.

This study is the second stage of an explanatory sequential mixed-methods study that began with quantitative data collection of individual depression treatment preferences, satisfaction with care, and health care discrimination experiences in a nationally representative sample of 711 individuals with moderate to severe depression symptoms. Quantitative data collection involved a web-based survey that included a discrete choice experiment (Clark et al., 2014) to measure treatment preferences. A validated questionnaire of health care discrimination was also included (Trivedi & Ayanian, 2006) wherein respondents were asked, “Have you ever felt that you were treated unfairly while getting medical care by your medical provider because of the following? (Check all that apply: race/color, ethnicity, language/accent, sexual orientation, and gender).” Survey results showed that health care discrimination experiences were much more common for Black and Hispanic/Latino respondents. Moreover, and contrary to prior studies in primary care settings, this community-based sample reported no significant differences by race/ ethnicity in preferences between medication versus talk therapy for treatment of depression, except in cases where Black respondents had also experienced discrimination (Sonik et al., 2020).

Few studies explore the interrelationship between prior experiences of poor quality of care, health care discrimination, and treatment preferences, which limits our complete understanding of pathways underlying mental health care disparities. In the qualitative component of this sequential explanatory mixed-methods study, we conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with individuals with depressive symptoms to address this gap.

Our objectives were to better understand (a) how past experiences of health care discrimination play a role in the experience of seeking and receiving mental health treatment, (b) whether and how treatment preferences are elicited by providers and then routinely incorporated into clinical care for depression, and (c) to what degree treatment preferences are shaped by experiences of health care discrimination.

Method

Description of Research Team

This study was conducted by a research–practice–community partnership between a safety net academic-clinical center; a community-based participatory research (CBPR) consultant (a researcher and advocate who also has lived experience living with mental illness); a statewide peer advocacy organization for people in recovery from serious mental illness, trauma, or addictions; and outside academic content experts. The safety net academic-clinical center (i.e., clinical center providing care to patients regardless of insurance status or ability to pay, and therefore serving a higher proportion of people who are low-income or on public insurance) included a clinical-research group (health services researchers, mental health and/or primary care clinicians) as well as community members (volunteer community health workers and team members with mental health patient experience). A description of the launch of the research–practice–community partnership has been published elsewhere (Delman et al., 2019). The statewide peer advocacy organization and CBPR consultant were involved in early co-development of the research project grant. After the project’s launch and throughout the research study, partnership members attended regular team meetings to jointly refine research objectives and hypotheses, design data collection instruments and protocols, and to collect, analyze, and interpret data.

Members of the research–practice–community partnership were invited to join a qualitative data collection and analysis subgroup. Six team members of the analysis subgroup conducted semi-structured interviews with 21 individuals with depressive symptoms. A PhD-level senior qualitative researcher and a PhD-level senior mixed-methods health services researcher led the subgroup, which also included two research assistants/coordinators, one student research volunteer, and one volunteer community health worker. Demographically, all six subgroup researchers were female, five of whom were from minority racial/ethnic minorities, and two of whom were native Spanish speakers. This qualitative subgroup worked in close collaboration with the larger research–practice–community partnership on the co-development of interview guides, participant recruitment, data collection, and data analyses and interpretation. The qualitative subgroup met iteratively to train its subgroup members on the research protocol, qualitative data collection methods, and to practice using and then refine the interview guide. Less experienced interviewers observed one to two initial interviews conducted by the senior researchers prior to conducting their first interview.

Study Design

Theoretical framework and interview guide design.

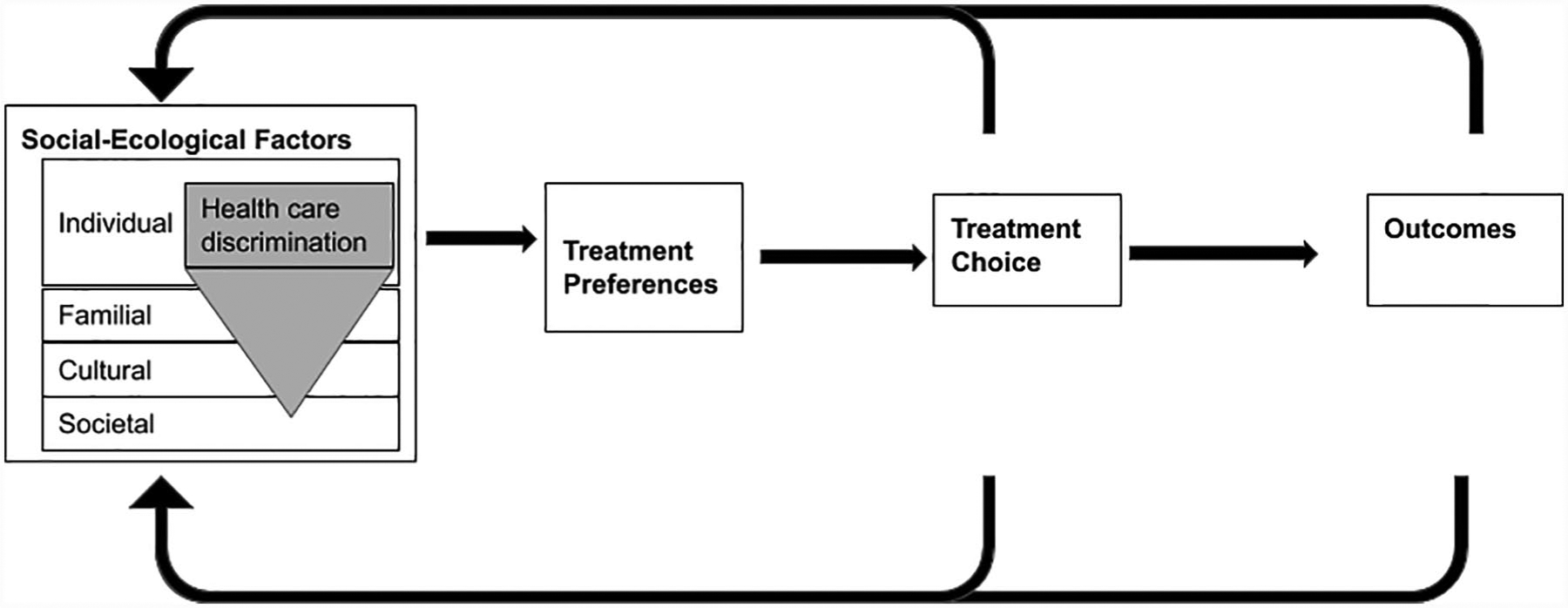

The research–practice–community partnership used a social-ecological framework (Golden & Earp, 2012) to inform a conceptual model of adaptive patient treatment preferences and to design the web-based quantitative survey as well as the qualitative interview guides. In this adaptive model, preferences and beliefs about treatments are updated based on exposure to individual-level, family-level, and sociocultural factors (see Figure 1), including health care discrimination, as well as through seeking and obtaining treatment. This study focused primarily on the role that individual-level experiences of health care discrimination (those most proximal to the individual) have in seeking and receiving mental health treatment, shaping depression treatment preferences, and the degree to which those preferences are routinely elicited and incorporated into treatment plans. As well, both the quantitative and qualitative data collection included questions about awareness of discrimination against family members or friends, as well as whether participants believed that people of color are always treated equally in health care (e.g., awareness of more distal discrimination experiences; see supplemental material for semi-structured interview guide).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of adaptive preferences informed by social-ecological model.

Participant selection.

Twenty-one participants completed semi-structured interviews, including 12 by phone (who had previously taken the nationally representative survey), and nine in person (these participants were not part of the nationally representative survey, but were recruited locally through the community partner organization to supplement the sample size due to an unanticipated change in recruiting and scheduling costs through the third-party online survey organization).

The 12 individuals who had previously participated in the nationally representative survey were purposively sampled to achieve an even mix (four each) of Non-Hispanic/Latino White, non-Hispanic/Latino Black, and Hispanic/Latino participants, 50% of whom had reported health care–based discrimination on the survey and 50% of whom had not. People who had not experienced discrimination were included to be able understand how their depression treatment experiences differed from those who had experienced discrimination. Two of the Hispanic/Latino participants were interviewed in Spanish by native Spanish speakers. Inclusion criteria included being above the age of 18 years and scoring greater than or equal to 10 on the PHQ-9 (representing moderate to severe depressive symptoms; Kroenke et al., 2001). To recruit 12 interviewees, survey participants were invited to participate in the qualitative study on a first-come, first-serve basis (see supplemental material for breakdowns within each category). Interviewers from the research team then phoned participants at times prescheduled by the online survey organization.

The additional nine participants were recruited locally through the mental health recovery advocacy partner organization (The Transformation Center). Information about the study and contact information for a research assistant was distributed through email and word-of-mouth recruitment. If contacted, the research assistant provided additional study information, issued an eligibility screener, and then scheduled the interview. Individuals were eligible if they (a) had ever been told by a doctor or nurse that they had depression, (b) were aged 18 years or above, and (c) identified as Black or African American, Latino/Hispanic, or non-Hispanic/Latino White.

Participants provided written informed consent to be interviewed, either through an online portal (online survey participants only) or in person. The nine participants interviewed in person completed a brief demographic questionnaire as well as the structured survey (a paper version identical to the survey participants had completed online) at the start of the study session. The interview portion followed immediately after administering the survey. All participants received a US$50 gift card. Interviews were approximately 45 minutes long, and conducted between November 6 to 17, 2017 (phone participants) and January 15 to 19, 2018 (in person participants). Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. All aspects of this work were approved by the institutional review Board of Cambridge Health Alliance.

Data analysis.

All transcribed interviews were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach and Dedoose Qualitative Software (Lieber et al., 2011). Six members of the study team coded the interviews (two researchers per interview) and generated summary analytic memos.

The senior qualitative researcher designed an initial qualitative code tree in line with the interview guide codeveloped by the research–practice–community partnership, which was then refined during iterative meetings within the qualitative research subgroup and with feedback from the research–practice–community partnership to determine important and relevant themes. Refining the final coding tree and deriving and summarizing important themes involved both deductive analysis (using codes developed in advance from interview guides) and inductive analysis (using open coding) to capture additional important concepts and patterns that emerged during interviews.

The two senior qualitative subgroup researchers oversaw coding training for researchers. Pairs of researchers then met to discuss coding for individual interviews, review and resolve coding discrepancies, and consolidate codes for each interview. Coding discrepancies that were not easily resolved within the pair of researchers were then brought to the larger six-person qualitative subgroup for discussion and to reach consensus on code application and/or to refine the code tree as needed. Researchers noted whether themes were particularly salient, striking, or emotional for the interviewee (e.g., by listening to all or part of interview audio). For example, stigma related to mental illness emerged as a relevant theme because participants mentioned it often and typically with high emotional charge, as well as because this theme resonated deeply with community partners with lived experience. The deductive methods therefore captured concepts already outlined in the interview guides driven by theory and the quantitative survey. Inductive methods, which are crucial when existing knowledge about a phenomenon is fragmented (Martinez-Hume et al., 2017), allowed researchers to capture additional key concepts driving the relationship between personal health care experiences and treatment preferences.

Throughout the qualitative analysis, the qualitative research subgroup attended to issues of reflexivity (examination of and minimizing researchers’ own interpretive biases). This was done within the subgroup through debrief sessions and through memos after conducting and coding each interview, and through continuous, iterative engagement with the larger research–practice–community partnership, including intentional reflection on the research process and collaborating to interpret qualitative data and prepare the article.

Results

A description of the sample is found in Table 1. Participants were mostly female (90%) and approximately 50% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Compared qualitatively with those who did not report prior health care discrimination (n = 9), those who did report discrimination (n = 12, or 57%) were more likely to head their household (83% vs. 56%), own their home (42% vs. 11%), and meet cutoff criteria for moderate to severe depression through the K-6 ≥13 cutoff (50% vs. 33%) or the PHQ-9 ≥10 cutoff (75% vs. 67%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Depression Interview Sample by Reports of Discrimination.

| Variable | All (n= 21) | Reported Discrimination (n = 12) | Did not Report Discrimination (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age | |||

| 18–44 years | 10 (48%) | 5 (41%) | 5 (55%) |

| 45–59 years | 6 (29%) | 3 (25%) | 3 (33%) |

| 60+ years | 3 (14%) | 3 (25%) | 0 (0%) |

| Missing | 2 (10%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (11%) |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino White | 9 (42%) | 5 (42%) | 4 (44%) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino Black | 8 (38%) | 3 (25%) | 1 (11%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 (19%) | 4 (33%) | 4 (44%) |

| Sex (female) | 19 (90%) | 11 (92%) | 8 (89%) |

| Bachelor’s degree + | 10 (50%) | 6 (55%) | 4 (44%) |

| Marital status: Single | 15 (71%) | 9 (75%) | 6 (67%) |

| Currently employed | 7 (33%) | 3 (25%) | 4 (44%) |

| Household size | 2.5 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.68) | 3.7 (0.53) |

| (Mean, SE) | |||

| K6 ≥13 | 9 (43%) | 6 (50%) | 3 (33%) |

| PHQ-9 ≥10 | 15 (71%) | 9 (75%) | 6 (67%) |

| Interview method | |||

| In person | 9 (43%) | 6 (50%) | 3 (33%) |

| By phone | 12 (57%) | 6 (50%) | 6 (67%) |

Note. Results from qualitative coding and thematic analysis of interviews are organized by major themes within each of the three overarching study objectives (see Table 2).

Those reporting prior health care discrimination included seven people of color (two Hispanic/Latino women, four Black women, and one Hispanic/Latino man) and five White women (one due to income/social class, three due to mental health diagnosis, and one due to receiving lab testing without her consent that resulted in a large surprise bill to her). Three White women reported health care discrimination only in the interview, but not in the survey (one due to income/social class and two because of mental health diagnosis). The remaining nine participants reported no discrimination, including four Black women, three White women, one White man, and one Hispanic/Latino woman.

Objective 1: How Past Experiences of Health Care Discrimination Shape Seeking and Receipt of Mental Health Treatment

Theme 1a: Challenges to receiving mental health treatment.

Participants shared the many different pathways they undertook in search of mental health treatment. Thematic analysis of these narratives uncovered a common theme that, regardless of experiencing health care discrimination, it was extremely difficult to find a mental health provider who accepted patient’s insurance, had availability in the patient panel, and was accessible to the patient. Participants also struggled to find a provider who was a “good fit,” and to stay in mental health treatment settings with strict attendance policies (e.g., when a patient missing a single visit was deemed “non-compliance,” justifying termination of treatment):

Every time I called, I was told that there’s a wait list, wait list, for several months, several months. At one point, they told me they are not even taking people. They are not taking names, because the wait list is so long … obviously if you are paying out of pocket, there is no problem at all. But if you are going through insurance the demand grossly exceeds the supply and it becomes this wait list nightmare of trying to make an appointment and not being able to make an appointment.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Lack of full consent to expensive treatment)

Participants often initiated mental health treatment through a primary care doctor, and here participants’ experiences demonstrated how the role of a trusting, long-term relationship with a provider was often critical to opening up discussions of mental health treatment, and in continuing to try different treatment modalities over a longer period of time:

This particular doctor did [know where I was coming from]. It took me a while to find this doctor … It made a big impact, this helped a lot … With the talking, it was hard to find somebody that I felt I could trust. That took a lot.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Income/social class)

Theme 1b: Health care discrimination exacerbates already complex mental health care seeking.

Participants primarily described health care discrimination based on race/ethnicity, mental health diagnosis, and social class.

Health care discrimination related to race/ethnicity.

Interviews uncovered that participants who reported personally experiencing discrimination driven by their race/ethnicity often also had friends or family members who had experienced discrimination. In many cases, they linked their personal experiences with historical and ongoing discrimination toward people of color at the societal and structural levels. When participants could recall both personal experiences of discrimination and were also aware of discrimination occurring at multiple social-ecological levels, this awareness often served to amplify their personal experiences and to reinforce the belief that, as people of color, their lives were not valued equally or that they were at risk of maltreatment in medical settings, and thus could not trust health systems and medical providers. This led to participants expressing feelings from extreme disappointment and frustration to, at times, fear and terror of medical settings. Below we highlight two powerful narratives from Black women that illustrate this interplay:

He left me without meds and I was in the waiting room, I was the only Black person in the waiting room … And I was thinking: This man left me without meds, sleep meds … I almost had a nervous breakdown and he’s giving [these white patients] over the amount of meds they need? … Back in the 60s and 70s when Black folks were shooting dope left and right, working the street, nobody was saying nothing … America is involved in the opioid crisis because white folks is dropping dead. It’s just ridiculous, it’s just plain ridiculous.

(Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

… So especially if you’re Black—you’re, they—they experiment on you, they give you these pills, they experiment on you and even if the –even if the FDA don’t approve these medicines they [are] still trying it on black people. And we’re dying off of them, we’re getting sick off of them, we’re getting cancer because of them, all types of things … So I just feel like, you know, Black people, we are just like cattle. You know if they want to kill us, they kill us. If they want our body parts they’ll take them and stuff like that … there’s things that’s happening with me right now and I’m –I’m not even going to the hospital because they killed my –my sister’s man.

(Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

A Black woman who did not feel she had been discriminated against nevertheless described an experience where one of the doctors and several nurses at her clinic saw her reading a health care administration book in the waiting room and had a discussion with her about what she was studying. After this experience, she was treated with more respect by the staff, highlighting the buffering role that perceived social status or education may sometimes play for patients of color:

And it was almost like because they knew that I was educated that I was treated with a lot more respect … and like it was more like I was treated like an ally or a peer, not just a patient. It was like a very weird shift. And I said “that is very, very strange.” … And so people with education it made me to believe, regardless of your race, or even of your personal recovery or whatever, if you have a certain level of education, then you’re in the club.

(Female, Black, No prior discrimination)

Similarly, a Hispanic/Latino participant, who reported past experiences of health care discrimination, highlighted how his choice of clothing led his providers to perceive him as threatening:

They would perceive you as you’re a thug, you’re going to rob them, you’re going to, you’re going to—you know or they are going to treat you this—they are going to talk to you or treat you in a certain way. Or—or—or skip you—skip over you or anything of that nature because you know you’re—you’re dressed that way.

(Male, Hispanic/Latino, Prior discrimination)

Health care discrimination related to mental health diagnosis.

Participants expressed concern that, because of their mental health diagnoses, they often lost credibility to advocate for themselves. For example, patients felt that providers and staff often judged patients with a mental health diagnosis as having limited competence. In those instances, the role of the physician in a trusting relationship was seen as particularly important:

Like especially in psychiatry and in mental hospitals, I mean like, I’ve been hospitalized when I had no need for it. That’s why I want to keep my doctor in my world because it’s like I can say I’m normal or I’m healthy all I want. No one is going to listen because I’m mentally ill, but if my doctor says “she is fine, she can do this,” they will all back away. They have no choice. So it’s kind of like a necessity of life. An external accommodation or like—I don’t know. So like, basically, you know, they do discriminate.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

Sometimes, I feel like I am being made out to be stupid and it’s, no, I am like depressed and I have an illness, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I am stupid. Like, oh, there was one time when my therapist asked if—it had to do with cooking—and my therapist asked if I could boil water. And I felt like saying, are you like, you know what I mean, when you just want to, like, storm out of the office, no, because I can’t do that because they’ll just up my medication.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

Participants experiencing distress (including in response to health care discrimination) reported that their emotional reactions were often attributed to their mental health condition, and that displaying these emotions put them at risk for increased medication dosages:

I went to [a medical clinic] and I went for a sore throat, but I was told that I had another issue, which is just, you know, a woman, just a woman issue and I got concerned. And she said that I seemed a little worried than usual and that my doctor needs to adjust my medicine. And she just saw that I was on a psychiatric medicine and I said … “It’s not for worrying, it doesn’t need to be adjusted.” And I tried to put in a complaint against them.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

Participants who were concerned about stigma associated with their mental health diagnosis also feared involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations. For one participant, this was especially salient when there was less of an established relationship with the provider:

I am afraid to go to emergency rooms … I have had discrimination based on having a mental health disorder … Like I am traumatized from being discriminated and I get nightmares …

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

Health care discrimination due to perceived social class.

Participants often reported discrimination in health care settings related to their ability to pay for treatment, which often occurred as early as entry into the waiting room and was related to their being on public health insurance:

If they’re going to look down on me because they think I don’t have that kind of money, you know, at that time, you know—if you’re not a moneyed person then you don’t belong in that clinic.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Income/social class)

However, race/ethnicity or mental health diagnosis often intersected with health care discrimination based on perceived social class. One participant described this as being a double disadvantage (“two strikes against you”) right at the front desk, and that it amplified her distrust of the clinical settings she visited for care:

But like if it’s a white nurse up there doing your registration and I felt they look at you really funny especially when you pull out your card and stuff like that, you know. It’s not like I’m trying—I want to be on [this public insurance]. I’m working hard every day. Just like everybody else and if I could, I’d pay for it all insurances and stuff—I will because I don’t want nobody looking down at me so. And it already scares me when I go in there and they are looking at me like that. I don’t even want to go in the back. Because no telling what they might do … You’re going to get a hard time because you have [Medicaid] or Medicare. You walk in with two strikes against you.

(Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

Objective 2: Understand Whether and How Treatment Preferences Are Elicited by Providers and Routinely Incorporated Into Clinical Care for Depression

Theme 2a: Treatment preferences are not often systematically elicited.

Most participants could not recall being asked outright about their treatment preferences in health care or discussing them explicitly with providers. More often, study participants reported being offered a menu of treatment options based on what was available at a particular clinic or by a particular provider:

Interviewer: “So does she know, does she know you want talk therapy, or—?”

Participant: “Well, no, I don’t know what she knew. We never got that far deep as far, really. Having a talk like this, we never did. Which I think is very important. At least one time, you know.” (Female, Hispanic/Latino, Prior discrimination)

Interviewer: “So have you, like, suggested to him that you wanted more—less medication, and more talk therapy?”

Participant: “No, I didn’t.” (Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

Interviewer: “Can you tell me little bit about how do you communicate that preference to your provider? Is it something you talk to him or her about?”

Participant: “No, exactly that. I leave providers that I don’t think are a good fit.” (Female, White, No Prior Discrimination)

Interviewer: “Okay. And what about the doctors that you’ve seen before, do they usually ask you about any of these things [preferences] or kind of, what matters to you most for your care?”

Participant: “No.”

Interviewer: “Okay. Have you ever kind of tried to volunteer that information before to them?”

Participant: “Well, sometimes.” (Female, White, Prior discrimination: Income/social class)

Theme 2b: Regardless of past health care discrimination, patients generally value a trusting relationship with clinicians that facilitates an individualized, fully informed approach to selecting optimal treatments.

Whether they were discriminated or not, participants expected a “good” mental health provider to be someone who listens and who understands them:

It’s just their presence and the way they talk to you, the way they present themselves to you. They don’t come to me or look like they looking down at me, like they are better than me.

(Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

I think a good medical provider is someone who is a good listener, someone who is patient and who is willing to allow the person to make choices instead of taking away their power.

(Female, Black, No prior discrimination)

Two participants also said that, for establishing trust with a provider, it was important that a provider has a good “vibe” or the right “forma de ser” (Spanish for “way of being”), which underscored the extent to which participants perceived good providers to not just display, but also to truly embody, these ideal characteristics:

That’s why I continue seeing her. It’s—it’s a great experience, you know, talking with her because she is the person that I can feel that vibe from that I was talking about before— being open and I feel like I can be, you know, open with her without, you know feeling edgy about it … [later in interview] Like I said I go by vibe sometimes—most times.

(Female, Black, No prior discrimination)

These aspects were seen as hallmarks of a trusting patient–provider relationship, which was, in turn, essential to ensuring an individualized treatment approach. Several participants mentioned this in the context of preferring to avoid providers who would “push” medication on them, either because they had not spent the time to learn if this would be optimal for the patient or because of participants’ belief that this approach was more lucrative for providers:

I think it’s someone who would agree with my concept of getting to know the individual before pushing a medication than you know, having the open discussion over the medication before just pushing it on the individual.

(Male, White, No prior discrimination)

I mean just somebody that’s really sincere. So a person—a doctor that really wants to really help people. So a real doctor that’s not out for money that really wants to help somebody and don’t choke everybody up with pills. Because that’s how they’re making their money. They’re making their money off of marketing everybody’s health and you know that’s what it’s based off of.

(Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

Participants who had not experienced discrimination were somewhat more likely to describe knowledge and clinical skills to be important provider attributes:

Someone who consistently has good outcomes … I like that she makes decisions based on evidence-based medicine.

(Female, White, No prior discrimination)

An ear to listen, definitely. Knowledge in their practicing area is another, sometimes a good recommendation from someone.

(Female, Black, non-Hispanic/Latino, No prior discrimination)

On the contrary, participants who had experienced health care discrimination more often used descriptions like “sincere,” “reliable,” “honest,” and other phrases that described the provider’s intentions:

Well I guess they have to listen and I guess, when it comes to providing advice or feedback or, you want them to, I guess, you want them to be knowledgeable. And you want them to be sincere and you want them to be coming from a place that has your best interests …

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

So somebody who is reliable and honest. Like, I’ve had too many bad experiences. I had this woman and then, like, after a year I was like this doesn’t seem to be going anywhere and she was like, yeah I never understood you, and I’m like excuse me!? … For a year!?

(Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

One participant with prior discrimination also directly contrasted the value of knowledge and skill versus having respect and care in the patient–provider relationship:

Participant: “He is not the best doctor. He is really kind of crappy. He has no knowledge on how to be a therapist, but he is a good person, and he has known me a long time, and he cares about me.”

Interviewer: “So, he is a therapist, not a psychiatrist?”

Participant: “He acts like that for me. He is a psychiatrist.” Interviewer: “Okay. He is a psychiatrist, but he—okay, he gives you talk therapy?”

Participant: “Yeah … .[later] He was a good person and he accepted me. He probably had compassion for the fact this … front office person couldn’t see me as a human being with a right to choose how I’m going to live … So he respected me, and that’s all that I need, right?” (Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

Objective 3: Understand to What Degree Treatment Preferences Are Shaped by Experiences of Health Care Discrimination

Theme 3a: Regardless of past health care discrimination, treatment preferences are fluid and shaped by shared decision-making with providers whom the patient trusts.

Establishing a balance of power within the patient–provider relationship was seen as essential to facilitating an open discussion of preferences and engaging in full shared decision-making around mental health treatment. Providers were seen as being responsive to patient-specific needs when they moved beyond simply describing the array of treatment options and toward fully utilizing shared decision-making if the patient wanted to have a say in treatment:

I have had providers in the past that I didn’t feel were customizing my therapy. And sometimes I felt like they were annoyed by questions that I asked about medicines they wanted to put me on and concerns that I had … I don’t know if it was a male-female thing, or just the patriarchy of medicine where doctors … just expected to not be questioned and just you know to do what the doctor says no matter what.

(Female, White, No prior discrimination)

Participants’ willingness to try various treatment options (including those outside their originally stated treatment preferences) was heavily contingent on this trusting relationship. One participant considered herself an “anti-medicine person,” but said she would be willing to discuss medication for her depressed mood after exploring other options:

I think she [provider] noticed I wasn’t myself, you know, when they see you over the years or even with the pregnancy when they see you the umpteenth time within the last few months, like almost every week. You know, they kind of get to know your personality … [Later in interview] I would want to explore other avenues to see what we can possibly do before we go down that avenue or at least give other options. I don’t want medicine to ever be just the only option.

(Female, Black, No prior discrimination)

Given that reaching a mental health diagnosis can take time, and that optimal treatment can change over time, narratives revealed that the decision to remain in mental health care also hinged upon maintaining this trusting relationship through which shared decision-making could continue to occur. A case in point is the narrative shared by another participant whose trusted primary care provider recognized her depression and successfully leveraged their established relationship to encourage her to try medications, despite her initial resistance. The medications gave her enough motivation to pursue the arduous task of finding a counselor despite being uninsured at the time. She ultimately found free counseling through her church network. When asked what might have happened had she not sought and ultimately received counseling, her response was blunt:

At the time, I was suicidal. So I would probably be dead.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Income/social class)

Theme 3b: Patients who have experienced health care discrimination face greater challenges to forming trusting relationships with providers to engage in shared decision-making, which serves to both elicit and shapes preferences.

A strong patient–provider relationship was important for all respondents, but for those who had experienced health care discrimination, a trusting relationship with a provider was often critical for more than just establishing an appropriate care plan. For those experiencing mental health diagnosis–based discrimination or stigma, medical providers were often able to restore agency to someone who was otherwise vulnerable to losing it. The disparate balance of power meant that the provider often had control of patients through their offer of treatment or linkage to referrals, but also that providers could affect an individual’s life beyond mental health treatment, including interactions with social and legal entities:

One of the most important things [about my doctor] is that he’ll write letters … to people that I need help from or that I’m getting screwed over by … I get, I buy a little bit of, it’s like, leverage in society. Because I feel like by myself with the label I have, people are just going to walk all over me, but I can have him write a letter and it lifts me up, protects me.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

Issues of trust and power imbalance were often exacerbated when participants faced multiple forms of discrimination, including outside health care settings. When they were not explicitly addressed, true shared decision-making around preferences could not occur:

… I was discriminated against, kind of like, I was told that no, you have quite the mental illness and you need, if you ever want to go to school or get a boyfriend or something, you need medicine. You are going to be on the medicine ’til your 40s or 50s, what you have is chronic … and that’s just the psychiatrist’s opinion thinking that if someone has really bad mental illness that they need medicine.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

Interviewer: “Okay. And while in this case if you talk directly with your doctor or the nurse that sees you about these preferences, would you be comfortable to talk to face-to-face?”

Participant: “Yeah, it depends on who they are and their energy.” (Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

Although most participants reported difficulty finding a medical provider who was a “good fit,” not all participants felt equal agency to change their provider and/or treatments that were not working for them. Below we highlight exemplar quotations demonstrating high versus low agency to advocate for different treatment and/or providers, contrasting differences in agency between those who did and did not experience health care discrimination:

-

High agency in response to poor provider or treatment fit: No Prior Health Care Discrimination

-

aParticipant: “I leave providers that I don’t think are a good fit.”

Interviewer: “And how often do you encounter providers that you don’t think are a good match?”Interviewer: “About half the time.” (Female, White, No prior discrimination)-

bInterviewer: “So if your provider all of a sudden stopped with talk therapy and says, okay, we only have medication, would you move to another [provider]?”

Participant: “I would.” (Female, Black, No prior discrimination)-

c“If I feel like you’re not giving us the best care. If you’re not listening to our issues or if we have an issue and I don’t feel like it’s the best care I get a second opinion, I’m out. I just—I can’t.” (Female, Black, No prior discrimination)

-

d“I say, well, if you’re not happy with your provider, you can always advocate for yourself and ask for a different provider.” (Female, White, No prior discrimination)

-

eInterviewer: “What should happen if your provider or clinic stopped offering the treatments that you like?”

Participant: “I would find somewhere else to go.” [Laughter]Interviewer: “You could change providers?”Participant: “Yeah, yeah, I would change my provider, yeah.” (Female, Black, No prior discrimination) -

a

- Low agency in response to poor provider or treatment fit: Prior Health Care Discrimination

- “You know but it’s –really they got –we don’t have a choice who our doctors are sometimes.” (Female, Black, Prior Discrimination)

- Interviewer: “So if your current provider stopped, like, having medication, then would you switch to another provider? And what about talk therapy?”

Participant: “Probably.”

…

Participant [Later in interview]: “You kind of have to be a bit submissive.” (Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

The need to establish a trusting patient–provider relationship, through which patients could obtain their treatment of choice, was described in more charged language by patients who had previously experienced health care discrimination. In some cases, narratives demonstrated that these participants needed to work harder to find the right provider or the right treatment:

… it doesn’t matter to me to go a little farther if it’s someone who is really worth going farther for.

(Female, Hispanic/Latino, Prior discrimination)

Because all of my emotional upset is being caused by this distorted thought … so I have found CBT to be and EMDR to be two of the most helpful things and so I have to have someone who, even if it is not their orientation, they’re familiar with it and they are going to be actively engaged. Because I can slide into, you know, a very, very, very dark and hopeless place and I haven’t for years because of the work that I have done and then the people I rely on as providers being actively engaged in listening, deep listeners, deep listening.

(Female, Black, Prior discrimination)

For patients who had experienced discrimination, and especially for those experiencing discrimination due to mental health diagnosis, a trusting relationship with a provider was the pathway through which they could exercise agency. If those trusted providers were to remove their patients’ agency, for example, through insisting on prescribing medications for the patient against their preferences which they had established over time with their providers, several participants described the feelings of fear, disappointment, and/or betrayal that would ensue:

Well, he already asks me, you know, this medication will be good or that one will be good, but that’s okay—he can say it. But if he starts saying, “No, you need this,” I’ll be like running for the hills.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

We will be alienated from each other, I’d be frightened and scared and feel alone … I mean it would ruin our whole relation, everything we’ve built for 15 years.

(Female, White, Prior discrimination: Mental health diagnosis)

Discussion

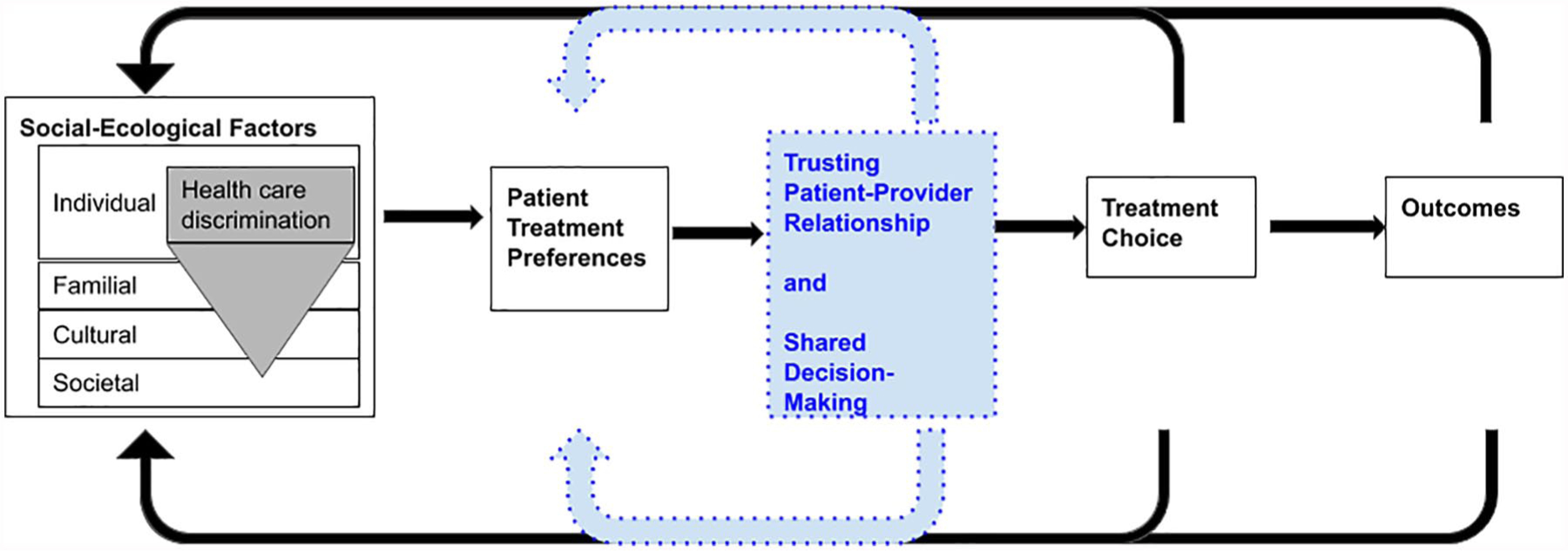

In contrast with past studies examining treatment preferences across diverse racial and ethnic groups (Cooper et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2014; Katz, 2001), our study focused on examining these preferences within the context of past experiences of health care discrimination. Our findings challenged our initial social-ecological conceptualization (see Figure 1), wherein patient treatment preferences were embedded in a unidirectional fashion between multiple socio-ecological factors (including health care discrimination) and treatment choice. Our qualitative findings suggest the need to integrate two other seemingly important factors shaping patient treatment preferences: trusting patient–provider relationships and shared decision-making. Within this revision of our initial model, shared decision-making and trusting patient–provider relationships are recursively related to one another (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Revised conceptual model of adaptive preferences informed by social-ecological model.

Study participants, who were predominantly female in our sample, valued providers who listen and those who they could trust. These relational attributes were crucial to building a strong patient–provider alliance at the outset of treatment and facilitating shared decision-making leading to preferred treatment options. However, the relational nature of mental health treatment that study participants described involved unequal power dynamics between patient and provider, and the course of treatment options and possible outcomes typically came with a large degree of uncertainty. All participants deemed a strong patient–provider alliance that is built upon trust and mutual respect as critical for providers in order for them to understand and continuously respect and incorporate patients’ treatment preferences. However, those participants that had experienced health care discrimination had to work harder to exercise sufficient agency to obtain preferred treatment and responsive providers. For them, the challenge of finding a trustworthy provider became much more arduous, and in some cases was perceived to be insurmountable because their identities were targets of discrimination on multiple levels (i.e., race/ethnicity, mental health diagnosis, and perceived social class).

Previous qualitative studies echo the findings presented here: lower income individuals who were made to feel ashamed during health care treatment for not having insurance or for using preventive services newly covered by public insurance plans after the Affordable Care Act often stopped seeking preventive or routine care (Allen et al., 2014). As in our study, researchers in that study noted that the “stigma was most often the result of a provider-patient interaction that felt demeaning, rather than an internalized sense of shame related to receiving public insurance of charity care” (p.289). This suggests that discriminatory health systems, rather than a priori preferences to avoid preventive or routine treatment, were at least in part responsible for lower income patients’ “unmet health needs, poorer perceptions of quality of care, and worse health across several reported measures” (Allen et al., 2014, p. 289). Also, in another study, the poor quality of care and negative interpersonal interactions that often mark the treatment experiences of people with public insurance was compounded by race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and illness status, and, as in the present study, impacted participants’ ability to access health care as well as their decisions to continue with their care (Martinez-Hume et al., 2017). These findings point to the impact that cumulative burden of multiple marginalized identities, including a psychiatric diagnosis, have on patient–provider relations and shared decision-making, two factors that we found to be key for patients to receive preferred treatment.

Our findings suggest that interventions aimed at reducing financial barriers to accessing mental health treatment (Creedon & Cook, 2016) or that reduce interpersonal stigma felt by patients themselves (Alvidrez et al., 2008) are not sufficient to eliminate racial/ethnic disparities in mental health treatment. These interventions do little to dismantle structural discrimination within the walls of health systems. In a recent study of lower income individuals on public Medicaid insurance in the United States “most already embraced a desire to take responsibility for their health,” but these individuals encountered many barriers to healthy lifestyle choices as well as access to health systems.(Bell et al., 2017, p.275).

Similarly, recommended educational interventions that lower intrapersonal stigma alone to increase retention in treatment (Alvidrez et al., 2008) will not be sufficient because they do not address either the mismatch between available and desired treatments (Dwight-Johnson et al., 2001; Ryan & Lauver, 2002; Swift & Callahan, 2009) or the ongoing instances of discrimination experienced in health care settings. However, our findings suggest that increased attention to preferences may result in better patient outcomes, treatment adherence, and cost-effectiveness across disease categories (Dwight-Johnson et al., 2001; Ryan & Lauver, 2002; Swift & Callahan, 2009).

The present study also underscores that ongoing exposure to stigma and discrimination interferes with building a strong patient–provider alliance built on mutual trust and respect. The combined effects of stigma, discrimination, and the therapeutic alliance (including patient–provider communication) may be more responsible for differences in access and continued engagement in mental health treatment, rather than a set of fixed treatment preferences or beliefs based on race and ethnicity. For example, one study found that most Hispanic/Latino patients with depression in primary care (61%) thought antidepressants were safe and helpful, but a large portion (39%) feared they could be addictive, and half of them did not tell their provider when they stopped their medication treatment (Green et al., 2017). Other studies point to the value that psychiatric patients deposit on shared decision-making as a cornerstone of quality care (Thomas et al., 2018) and the role of therapists as worthy “co-pilots” to increase engagement in depression treatment (Heilemann et al., 2016).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although approximately half of the participants were sampled from a nationally representative survey, the 21 participant interviews are not nationally representative of experiences of people with depressive symptoms, and their experiences are not generalizable to all individuals with depressive symptoms. Demographics were most likely driven by the recruitment setting, which included one community-based mental health recovery organization in addition to participants from a nationally representative quantitative survey sample. Those individuals recruited through the mental health recovery organization tended to have more extensive mental health treatment histories, lower current PHQ-9 scores, and it was initially thought they may have been more likely to have experienced discrimination or to be willing to discuss their treatment experiences in more detail (possibly because interviews with this group were conducted in person). In fact, both groups disclosed prior discrimination at similar rates, and we found the interviews from both groups to contain equally rich narratives. The participant sample was also largely female. It is possible that women are more likely to perceive discrimination in these contexts, to be willing to discuss them, and/or to value the strength of the relationship with their health care providers, including as a means of conducting shared decision-making around treatment preferences. Although the sample was purposively selected based on equal balance of race/ethnicity and prior experiences of discrimination, unfortunately, there were no Black men represented in these interviews. Existing studies show that men, and particularly men of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, are less likely to seek care in mental health care setting and are more likely to suppress the need for preventive health services (Courtenay, 2000; Hammond et al., 2010; Williams, 2008). Moreover, for Black men, racial discrimination is a pervasive feature of their everyday lived experience that has been associated with higher depressive symptoms and reluctance to seek help in clinical settings (Matthews et al., 2013; Powell et al., 2016; Ward & Mengesha, 2013). Future qualitative studies seeking to capture racial and gender balance in mental health care experiences should expand recruitment to trusted organizations frequented by the target population(s), such as barbershops, hair salons, churches (Hankerson & Weissman, 2012; Luque et al., 2014), community centers, and neighborhood associations (Doornbos et al., 2012). Two interview modalities were used in part to reduce potential bias in either the phone-based sample (who included participants who had self-selected to be regular paid volunteers for surveys and interviews) or the in person sample (who included participants connected to a peer-based mental health advocacy organization). Nonetheless, either group may include individuals more willing to discuss their mental health treatment and discrimination experiences than the general population.

Finally, we recognize that provider communication with patients can be impacted by implicit biases including toward their patients from different racial/ethnic minority backgrounds, and this in turn can influence how they communicate with patients, as well as treatment decisions for the patient. (Chapman et al., 2013; Hall et al., 2015; Merino et al., 2018; Olcon & Gulbas, 2018) Our study points to explicit, observable discrimination experiences reported by participants, whereas examples of implicit bias may be much harder for individuals to observe in the course of their treatment. Despite these limitations, the study’s many strengths help provide an in-depth look into how prior health care discrimination may impede shared decision-making for patient treatment preferences.

Conclusion and Implications

This study uncovered an in-depth understanding of experiences of how health care discrimination among individuals experiencing depressive symptoms shaped their ability to enter treatment, establish trusting relations with providers, explore their preferences for treatment with that provider, and engage in ongoing shared decision-making as treatment continued.

Overall, our findings and prior literature point to the importance of building a trusting therapeutic alliance. Policies that focus on removing barriers to depression care will likely fall short unless disruptive changes can be made to the structure of mental health care delivery, including training to acknowledge patient experiences of discrimination and equity-focused treatment modalities. In addition, finance- and insurance-based policies should be accompanied by other concerted efforts to reduce experiences of discrimination in health care. Collectively, these changes to the status quo of mental health care delivery may provide a path forward for patients to form more trustworthy relationships with their providers and to engage openly and honestly about discrimination in patient care.

Data Sharing

Transcribed interviews contain information that could compromise participant anonymity and thus cannot be shared publicly.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Research Objectives and Major Qualitative Themes.

| No. | Objective | Major Themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Understand how past experiences of health care discrimination play a role in the experience of seeking and receiving mental health treatment | 1a: Challenges to receiving mental health treatment 1b: Health care discrimination exacerbates already complex mental health care seeking |

| 2 | Understand whether and how treatment preferences are elicited by providers and then routinely incorporated into clinical care for depression | 2a: Treatment preferences are not often systematically elicited 2b: Regardless of past health care discrimination, patients generally value a trusting relationship with clinicians that facilitates an individualized, fully informed approach to selecting optimal treatments |

| 3 | Understand to what degree treatment preferences are shaped by experiences of health care discrimination | 3a: Regardless of past health care discrimination, treatment preferences are fluid and shaped by shared decision-making with providers whom the patient trusts 3b: Patients who have experienced health care discrimination face greater challenges to forming trusting relationships with providers to engage in shared decision-making, which serves to both elicit and shape preferences |

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank participants in this study who shared their personal accounts of health and mental health treatment.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded through a Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) award, “Improving Methods of Incorporating Racial/Ethnic Minority Patients’ Treatment Preferences into Clinical Care” (Principal Investigator: Benjamin Lê Cook, ME-1507-31469). The funder required researchers to submit research protocols and changes for review, and to justify any protocol changes to ensure they did not compromise the research plan. Researchers also provided regular progress report updates to the funder. However, all research decisions were made independently by the research team. Authors had full access to the data and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Biographies

Ana M. Progovac is an instructor in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA and Senior Scientist at the Health Equity Research Lab, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge MA, USA.

Dharma E. Cortés is a senior Scientist at the Health Equity Research Lab, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA.

Valeria Chambers is Founder of Black Voices: Pathways 4 Recovery in Boston, MA, USA and is currently also affiliated with the Health Equity Research Lab, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA, USA. She was the Research and Policy Development Coordinator at The Transformation Center at the time this work was conducted.

Jonathan Delman is a research professor at the Department of Psychiatry and Associate Director of Participatory Action Research at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA.

Deborah Delman is an independent Senior Consultant for nonprofit and healthcare sectors with a focus on peer support practice, policy, and integrated health teams. She was Executive Director of The Transformation Center in Roxbury, MA, USA at the time this work was conducted.

Danny McCormick is a is an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and is the director of the Division of Social and Community Medicine in the Department of Medicine at the Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA, USA. He is also a co-director of the Harvard Medical School Fellowship in General Medicine and Primary Care.

Esther Lee is a graduate student in Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health. She was a Research Assistant at Cambridge Health Alliance at the time this work was conducted.

Selma De Castro is a Mobility Mentor at Just A Start Corporation, and Research Assistant at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, MA, USA. She was a Volunteer Health Advisor at Cambridge Health Alliance at the time this work was conducted.

María José Sánchez Román is a doctor by training and a recent public health graduate in community health. She was a research assistant at Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA, USA at the time this work was conducted.

Natasha A. Kaushal is a graduate student in the Boston University School of Public Health.

Timothy B. Creedon is a Research Scientist at the Health Equity Research Lab, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA.

Rajan A. Sonik is the Director of Research at the AltaMed Institute for Health Equity in Los Angeles, CA, USA, and was a postdoctoral fellow at Cambridge Health Alliance at the time this work was conducted.

Catherine Rodriguez Quinerly is the Metro Boston Area Director of Recovery and the Human Rights Coordinator at Solomon Carter Fuller Mental Health Center, Department of Mental Health, Boston, MA, USA. She was the Community Voice Policy Director at The Transformation Center at the time this work was conducted.

Caryn R. R. Rodgers is an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Leslie B. Adams is a David E. Bell Postdoctoral Fellow at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She is currently affiliated with the Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD.

Ora Nakash is professor and director of the Doctoral program at the School for Social Work, Smith College, Northampton, MA, USA.

Afsaneh Moradi is a General Practitioner in the Blair Athol Medical Clinic in Blair Athol, Australia. She was a Volunteer Health Advisor at Cambridge Health Alliance at the time this work was initiated.

Heba Abolaban is a public health physician and a researcher and lab manager at the Muslims and Mental Health Lab at Stanford University in Palo Alto, CA, USA. She was a Muslim Community Health Consultant at Cambridge Health Alliance at the time this work was conducted.

Tali Flomenhoft is the associate director of Parent and Family Giving at Brandeis University in Waltham, MA, USA. She was a research assistant at Cambridge Health Alliance at the time this work was conducted.

Ruth Nabisere is a Community Health Worker in areas around Boston, MA, USA. She is a patient at Cambridge Health Alliance, and was a senior patient representative for CHA’s Patient Partners’ Program at the time this work conducted.

Ziva Mann is currently the Director of Learning and Development at Ascent Leadership Networks, and faculty for the Institute of Healthcare Improvement. When this work was conducted, she was the Patient Lead at Cambridge Health Alliance, where she led the primary care Patient Partner volunteer program.

Sherry Shu-Yeu Hou is a PhD student in Epidemiology at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She was a Research Coordinator and Project Manager at Cambridge Health Alliance at the time this work was conducted.

Farah N. Shaikh contributed her experience as a Patient Partner at Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA, USA at the time this work was conducted.

Michael Flores is a Research and Evaluation Scientist at the Health Equity Research Lab in the Department of Psychiatry at Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Dierdre Jordan is the associate cooperative education coordinator at the Bouve College Cooperative Education, Department of Health Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA. She was a member of the Cambridge Health Alliance Patient Partners at the time this work was conducted.

Nicholas J. Carson is a clinical research associate at the Health Equity Research Lab and the medical director for child and adolescent outpatient psychiatry at the Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, USA.

Adam C. Carle is an associate professor of Pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati, OH, USA.

Frederick Lu is a Medical student at the Boston University School of Medicine. He was a research assistant at the Cambridge Health Alliance when this work was conducted.

Nathaniel M. Tran is a research assistant at the Health Equity Research Lab, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Margo Moyer is a research assistant at the Health Equity Research Lab, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Benjamin L. Cook is an associate rofessor in Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Director of the Health Equity Research Lab at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, MA, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Jon Delman reports stock ownership in health care stock related to managed care or health care technology. The rest of the authors have no financial relationships to report. The authors deem there to be no relevant conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Ethics Approval

All aspects of this study were approved by the Cambridge Health Alliance Institutional Review Board (CHA-IRB-1038/05/16). All participants gave written informed consent to be interviewed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr.

References

- Allen H, Wright BJ, Harding K, & Broffman L (2014). The role of stigma in access to health care for the poor. The Milbank Quarterly, 92(2), 289–318. 10.1111/1468-0009.12059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, Rao SM, & Boccellari A (2008). Psychoeducation to address stigma in Black adults referred for mental health treatment: A randomized pilot study. Community Mental Health Journal, 45(2), 127–136. 10.1007/s10597-008-9169-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, Hughes-Halbert C, & Asch DA (2006). Patient preferences can be misleading as explanations for racial disparities in health care. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(9), 950–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell HS, Martínez-Hume AC, Baker AM, Elwell K, Montemayor I, & Hunt LM (2017). Medicaid reform, responsibilization policies, and the synergism of barriers to low-income health seeking. Human Organization, 76(3), 275–286. 10.17730/0018-7259.76.3.275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benuto LT, Gonzalez F, Reinosa-Segovia F, & Duckworth M (2019). Mental health literacy, stigma, and behavioral health service use: The case of Latinx and non-Latinx Whites. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 6, 1122–1130. 10.1007/s40615-019-00614-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt JR, Corbett J, & Bondaryk MR (2014). Addressing disparities and achieving equity: Cultural competence, ethics, and health-care transformation. Chest, 145(1), 143–148. 10.1378/chest.13-0634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, & Kessler RC (2006). Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychological Medicine, 36(1), 57–68. 10.1017/s0033291705006161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil EV, & Sarmiento IA (2009). Clinical approaches to working with Latino adults. In Villarruel FA, Carlo G, Grau JM, Azmitia M, Cabrera NJ, & Chahin TJ (Eds.), Handbook of Latino psychology (pp. 329–345). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, & Cooper LA (2007). Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(3), 389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman EN, Kaatz A, & Carnes M (2013). Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(11), 1504–1510. 10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney E, Goodwin GM, & Fazel S (2014). Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry, 13(2), 153–160. 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, Moro D, & de Bekker-Grob EW (2014). Discrete choice experiments in health economics: A review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics, 32(9), 883–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins TC, Clark JA, Petersen LA, & Kressin NR (2002). Racial differences in how patients perceive physician communication regarding cardiac testing. Medical Care, 40(1), I-27–I-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Trinh N-H, Li Z, Hou SS-Y, & Progovac AM (2016). Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004–2012. Psychiatric Services, 68(1), 9–16. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Zuvekas SH, Carson N, Wayne GF, Vesper A, & McGuire TG (2014). Assessing racial/ethnic disparities in treatment across episodes of mental health care. Health Services Research, 49(1), 206–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Wang NY, & Ford DE (2003). The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care, 41, 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, & St George DMM (2002). Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(21), 2458–2463. 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), 1385–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creedon TB, & Cook BLJHA (2016). Access to mental health care increased but not for substance use, while disparities remain. Health Affairs, 35(6), 1017–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delman J, Progovac AM, Flomenhoft T, Delman D, Chambers V, & Cook BL (2019). Barriers and facilitators to community-based participatory mental health care research for racial and ethnic minorities. Health Affairs, 38(3), 391–398. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doornbos MM, Zandee GL, DeGroot J, & Warpinski M (2012). Desired mental health resources for urban, ethnically diverse, impoverished women struggling with anxiety and depression. Qualitative Health Research, 23(1), 78–92. 10.1177/1049732312465018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Norton WE, Gaertner SL, & Shelton JN (2008). Disparities and distrust: The implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 478–486. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, & Wells KB (2000). Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15(8), 527–534. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Tang L, & Wells KB (2001). Can quality improvement programs for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment? Medical Care, 39(9), 934–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna LR, Alegria M, & Gao S (2010). Retention in depression treatment among ethnic and racial minority groups in the United States. Depression and Anxiety, 27(5), 485–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin DJ, Price A, Brandon DT, & LaVeist TA (2009). Segregation and disparities in health services use. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(5), 578–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden SD, & Earp JAL (2012). Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Education & Behavior, 39(3), 364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Watson MR, Kaltman SI, Serrano A, Talisman N, Kirkpatrick L, & Campoli M (2017). Knowledge and preferences regarding antidepressant medication among depressed Latino patients in primary care. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(12), 952–959. 10.1097/nmd.0000000000000754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, Eng E, Day S, & Coyne-Beasley T (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e60–e76. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP, Matthews D, & Corbie-Smith G (2010). Psychosocial factors associated with routine health examination scheduling and receipt among African American men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 102(4), 276–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankerson S, & Weissman M (2012). Church-based health programs for mental disorders among African Americans: A review. Psychiatric Services, 63(3), 243–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilemann MV, Pieters HC, & Dornig K (2016). Reflections of low-income, second-generation Latinas about experiences in depression therapy. Qualitative Health Research, 26(10), 1351–1365. 10.1177/1049732315624411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Tilley JL, Jones EO, & Smith CA (2014). The contribution of cultural competence to evidence-based care for ethnically diverse populations. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 305–338. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K, Lim D, & Shi Y (2014). Racial-ethnic disparities in use of antidepressants in private coverage: Implications for the Affordable Care Act. Psychiatric Services, 65(9), 1140–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JN (2001). Patient preferences and health disparities. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(12), 1506–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan BM, Dimidjian S, & Rizvi SL (2010). Treatment preference, engagement, and clinical improvement in pharmacotherapy versus psychotherapy for depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(8), 799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie DA, Lee-Rey E, Gomez A, Bereknyei S, & Braddock CH III. (2011). Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(3), 317–325. 10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber E, Weisner T, & Taylor J (2011). Dedoose software. Sociocultural Research Consultants. [Google Scholar]