Abstract

Chronic caffeine ingestion (CCI) by male NIH Swiss strain mice results in a prolonged reduction in locomotor activity and alterations in response to caffeine, other xanthines, and adenosine analogs. Caffeine, the A1 selective 8-cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT), and the A2-selective 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX) remain stimulatory and the bell-shaped locomotor dose-response curves are left-shifted after CCI. The depressant effects of methylxanthines that are potent phosphodiesterase inhibitors remain after CCI. After CCI, mice became more sensitive to depressant effects of A1, mixed A1/A2, and A2 agonists. In the presence of caffeine the A1-selective agonist N6-cyclohexyladenosine (CHA), the mixed A1/A2 agonist 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine and the A2-selective agonist 2-[(2-aminoethylamino)-carbonylethylphenylethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (APEC) all have dose-response curves, appearing to consist of initial depressant effects, then stimulatory effects, and finally pronounced depressant effects. The phasic character is reduced or absent after CCI. Synergistic depressant effects of combinations of CHA and APEC also appear reduced after CCI.

Keywords: adenosine receptors, caffeine, adenosine analogs, behavior, locomotor activity

INTRODUCTION

Caffeine has a variety of biochemical actions, including blockade of adenosine receptors, stimulation of release of intracellular calcium, and inhibition of phosphodiesterase activity [Daly, 1993]. It is generally thought that the stimulatory effects of caffeine on behavior are due to blockade of’ central adenosine receptors. Two major classes of adenosine receptor occur in the central nervous system (CNS), the A1-receptors, and the A2-receptors. One subtype of A2-receptors, the high-affinity A2a-receptor, is primarily associated with the basal ganglia. Caffeine is a non-specific antagonist at A1- and A2-receptors, but selective A1- and A2-receptor agonists and xanthine antagonists have been developed [Jacobson et al., 1992]. Although caffeine and other xanthines can reverse the behavioral depressant effects of adenosine analogs [Choi et al., 1988; Snyder et al., 1981], unexplained interactions occur that suggest a complex interplay in the CNS. Thus, in combination with low doses of caffeine, an adenosine analog can cause stimulation rather than depression of locomotor activity [Coffin et al., 1984; Katims et al., 1983; Snyder et al., 1981]. Certain xanthines, such as 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), are behavioral depressants. It has been proposed that such depressant effects are due to activity of such xanthines as inhibitors of a calcium-independent cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase [Choi et al., 1988]. Even such xanthines can become stimulatory in combination with an adenosine analog [Katims et al., 1983; Snyder et al., 1981] or with caffeine [Phillis et al., 1986].

Chronic effects of caffeine are well-known and include tolerance, withdrawal syndromes and biochemical alterations [see Daly, 1993; Nehlig et al., 1992]. In our own prior studies with male NIH Swiss mice, tolerance to caffeine did not occur [Nikodijević et al., 1993]. Instead, chronic caffeine ingestion (CCI) resulted in a prolonged reduction in locomotor activity and alterations in responses to caffeine, other xanthines, and adenosine analogs, and nicotinic, muscarinic, and dopaminergic agents. The results suggested that chronic treatment with caffeine causes alterations in adenosinergic, cholinergic, and dopaminergic systems. CCI mice have now been used to examine the complex relationships between effects of xanthines alone and in combination with adenosine analogs on open-field locomotor activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs

2-[(2-Aminoethylamino)-carbonylethylphenylethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (APEC) and 1,3-dipropyl-7-methylxanthine (DPMX) and 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX) were synthesized as described [Daly et al., 1986; Jacobson et al., 1989]. Rolipram was from A.G. Schering (Berlin, Germany). Caffeine (free base, Matheson Coleman and Bell, Cincinnati, OH) and other compounds were from standard commercial sources.

Animals

Adult male mice of the NIH Swiss strain weighing 25–30 g were housed in groups of 10 animals per cage with a light-dark cycle of 12:12 h. Mice were 5 weeks old when received and were kept for 5–7 days before initiating any experiment. The animals were given free access to standard pellet food and water. In chronic caffeine-treated mice, a caffeine solution (1 g/liter water) was provided instead of drinking water for seven days. The liquid intake was the same in control and CCI mice as was the weight gain and general appearance [Nikodijević et al., 1993]. The ingestion corresponded to 100 mg/kg of caffeine per mouse over a 24 h period. A 2–4 h period, usually 3 h, without access to caffeine, preceded testing. Animals were acclimatized for 24 h in laboratory conditions prior to testing. Each animal was used only once in the activity monitor. Animals were placed in the activity monitor for a 10 min acclimatization prior to beginning measurement of locomotor activity. Animals were not tested until 1.5 h after beginning of the light period.

Open-Field Locomotor Activity

The locomotor activity of individual animals was studied in a Digiscan activity monitor (Omnitech Electronics Inc., Columbus, OH) equipped with an IBM-compatible computer. The computer-tabulated measurements represent multivariate locomotor analysis with specific measures, such as simultaneous measurements of ambulatory (horizontal activity, total distance traveled), rearing, stereotypical, and rotational behaviors. Data was collected in the morning for three consecutive intervals of 10 min each and then analyzed as a group for a 30 min sampling period, except for the time curve experiments. The results for total distance traveled are reported as mean ± standard error for each point. All drugs were dissolved in a 20:80 v/v mixture of Alkamuls EL-620 (Rhone-Poulenc Chemicals Corp., Wayne, NJ) and phosphate-buffered saline and administered IP in a volume of 5 ml/kg body weight. Where applicable, the antagonist was injected 5 minutes before the agonist.

Data Analysis

Certain curves were subjected to analysis of variance (see Figure legends). ANOVA statistical analysis was performed using the Systat program (Systat Intelligent Software, Evanston, IL) and data points compared using the Bonferroni-adjusted or Fisher-adjusted t-test. In addition, in some instances data points were compared using the Student’s t-test with restriction of significance to P < 0.01. EC50 values were obtained from dose-response curves using the GraphPAD program (GraphPAD Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

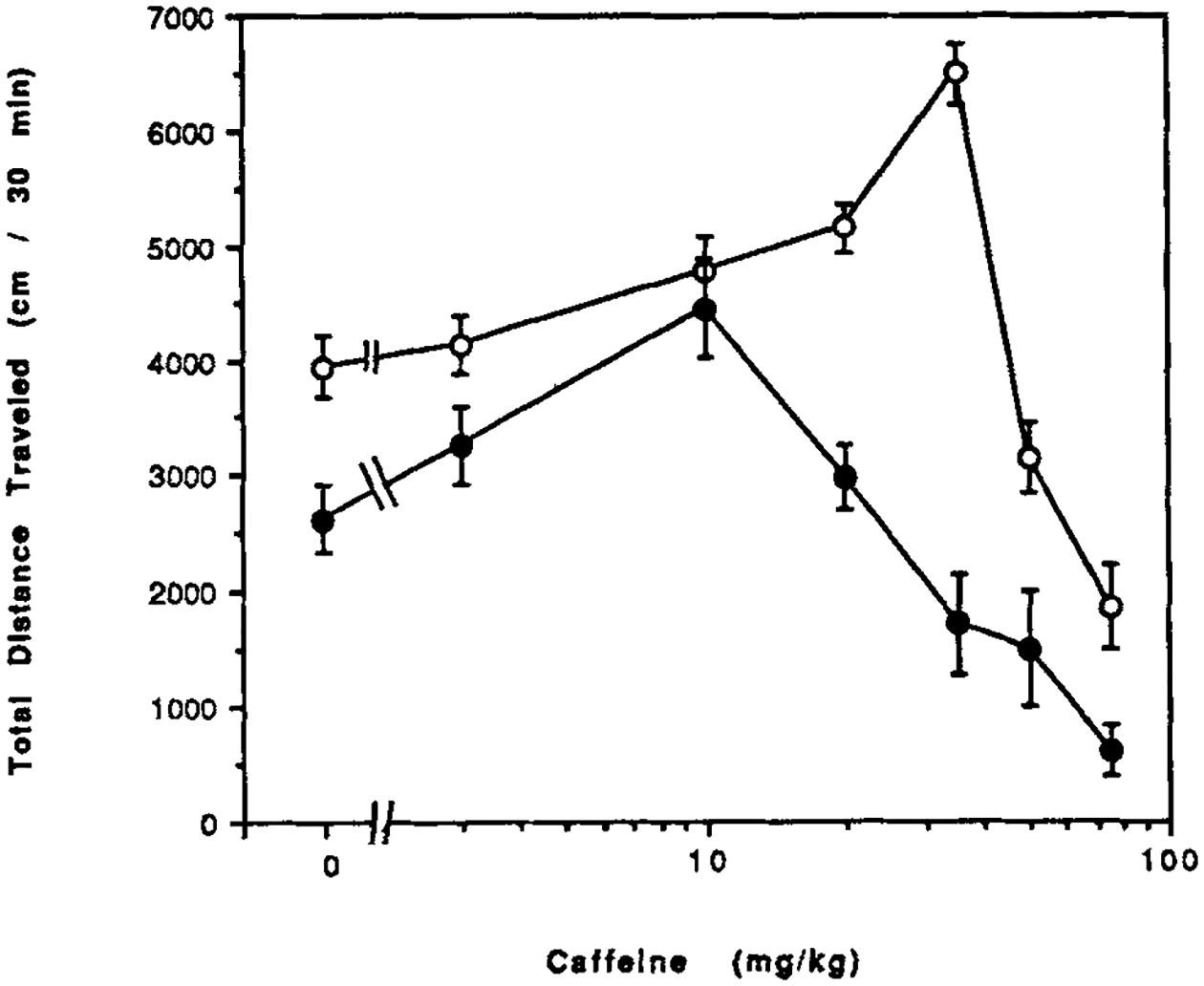

Male NIH Swiss strain mice after seven days of chronic caffeine ingestion have open-field behavior reduced by 41% from a value for total distance traveled of 3,940 ± 260 (n = 66) cm/30 min in control mice to 2,630 ± 300 (n = 53) cm/30 min in CCI mice. Caffeine in such CCI mice causes about the same 1.7-fold stimulation of locomotor activity as it does in control mice (Fig. 1). However, the threshold for stimulatory effects of caffeine is lower in CCI mice than in control mice, and the maximal response occurs at a lower dose (10 mg/kg versus 35 mg/kg). The ED50 values for caffeine were 18 mg/kg in control mice and 4 mg/kg in CCI mice.

Figure 1.

Dose response curves for locomotor effects of caffeine. Caffeine was injected ip in control mice (open circles) and in mice after chronic caffeine ingestion (closed circles). Values are means ± s.e.m. (n = 8–30). The effect of CCI on the dose response curve was statistically significant (ANOVA). At 35 mg/kg, P < 0.001 for CCI vs. water control (Bonferroni). The threshold in water control was 25 mg/kg (P < 0.001) and in CCI mice was 10 mg/kg (P < 0.005) (Bonferroni).

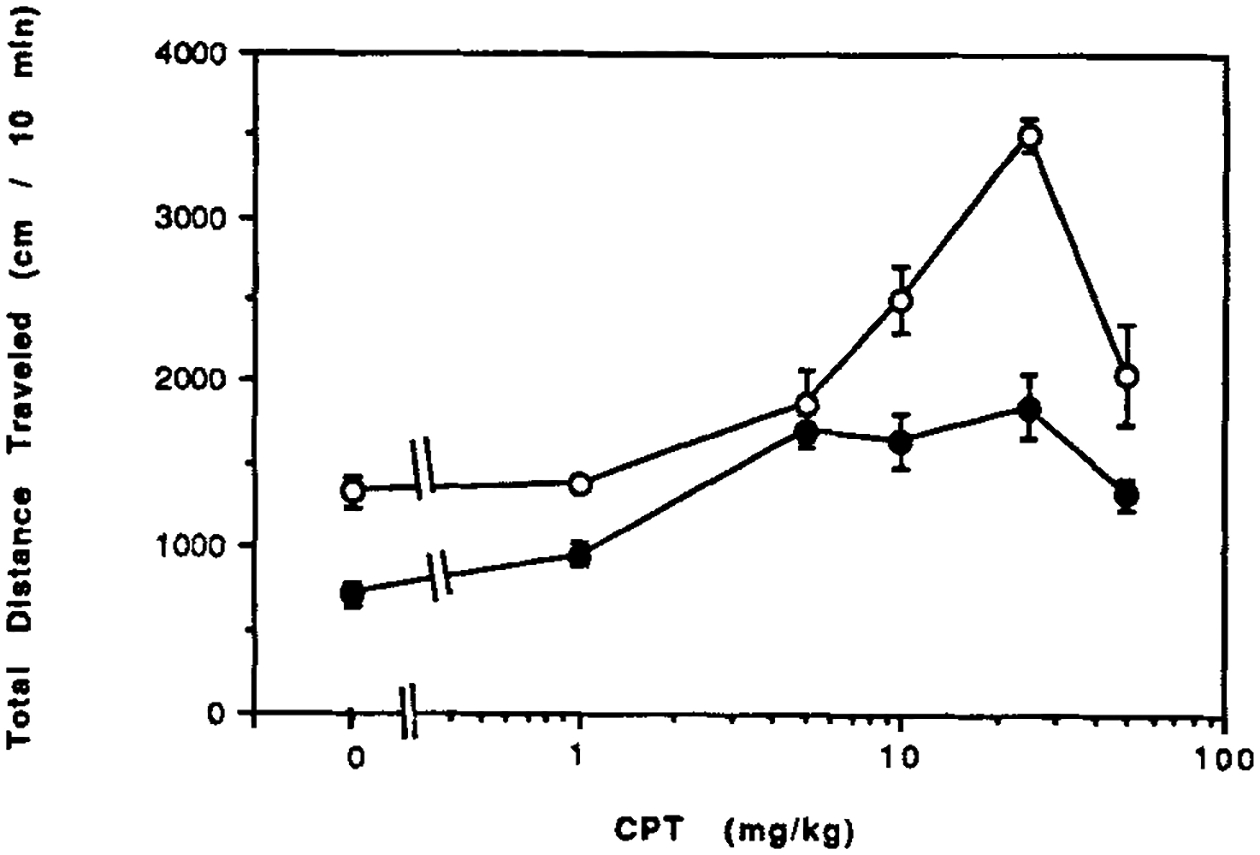

The A1-selective antagonist 8-cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT) causes a marked initial stimulation of locomotor activity, which maximizes at 25 mg/kg with a 2.5-fold stimulation (Fig. 2). The stimulation by CPT at doses of 25 mg/kg or less is transient, being maximal in the first 10 minutes (data not shown). Effects of caffeine are not transient over the 30 min observation time. The maximal 2.5-fold increase in locomotor activity elicited by CPT is similar in control and CCI mice (Fig. 2). However, as was the case for caffeine, the threshold dose is lower in the CCI mice. The ED50 values for CPT were 9 mg/kg in control mice and 2.3 mg/kg in CCI mice. At a dose of 25 mg/kg CPT, this A1-selective antagonist reaches maximal levels of about 50 μM in mouse brain, followed by a rapid clearance [Baumgold et al., 1992]. Such peak levels of CPT would be sufficient to block both A1- and A2-receptors.

Figure 2.

Dose response curves for locomotor effects of an A1-selective xanthine 8-cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT). CPT was injected ip in control mice (open circles) and in mice after chronic caffeine ingestion (closed circles). Locomotor activity is for a 10 min period. Values are means ± s.e.m. (n = 5–14). The effect of CCI on the dose response curve was statistically significant (ANOVA). At 25 mg/kg, P < 0.001 for CCI vs. water control (Bonferroni). The threshold in water control was 10 mg/kg (P < 0.001) and in CCI mice was 5 mg/kg (P < 0.001) (Bonferroni).

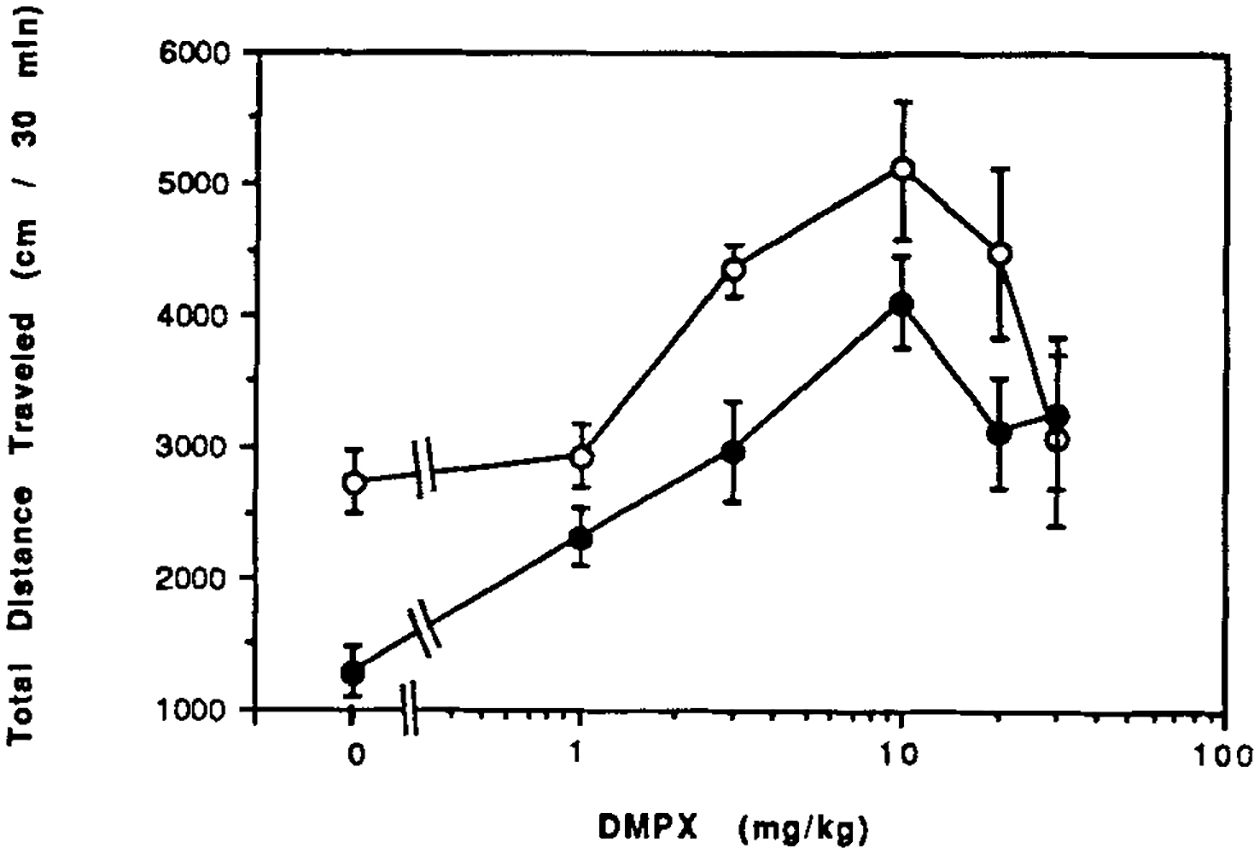

3,7-Dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX), a xanthine about 10-fold selective for A2-receptors [Seale et al., 1988; Ukena et al., 1986], has locomotor effects very similar to caffeine (Fig. 3). Maximal locomotor stimulation occurs at a dose of 10 mg/kg DMPX in both control and CCI mice. The threshold for stimulation appeared reduced in CCI mice, but this was not statistically significant using the Fisher-adjusted t-test. The ED50 values for DMPX were 2.1 mg/kg in control mice and 2.0 mg/kg in CCI mice.

Figure 3.

Dose response curves for locomotor effects of an A2-selective xanthine 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX). DMPX was injected ip in control mice (open circles) and in mice after chronic caffeine ingestion (closed circles). Values are means ± s.e.m. (n = 6–14). The effect of CCI on the dose response curve was statistically significant (ANOVA). At 3 mg/kg, P < 0.02 for CCI vs. water control (Fisher).

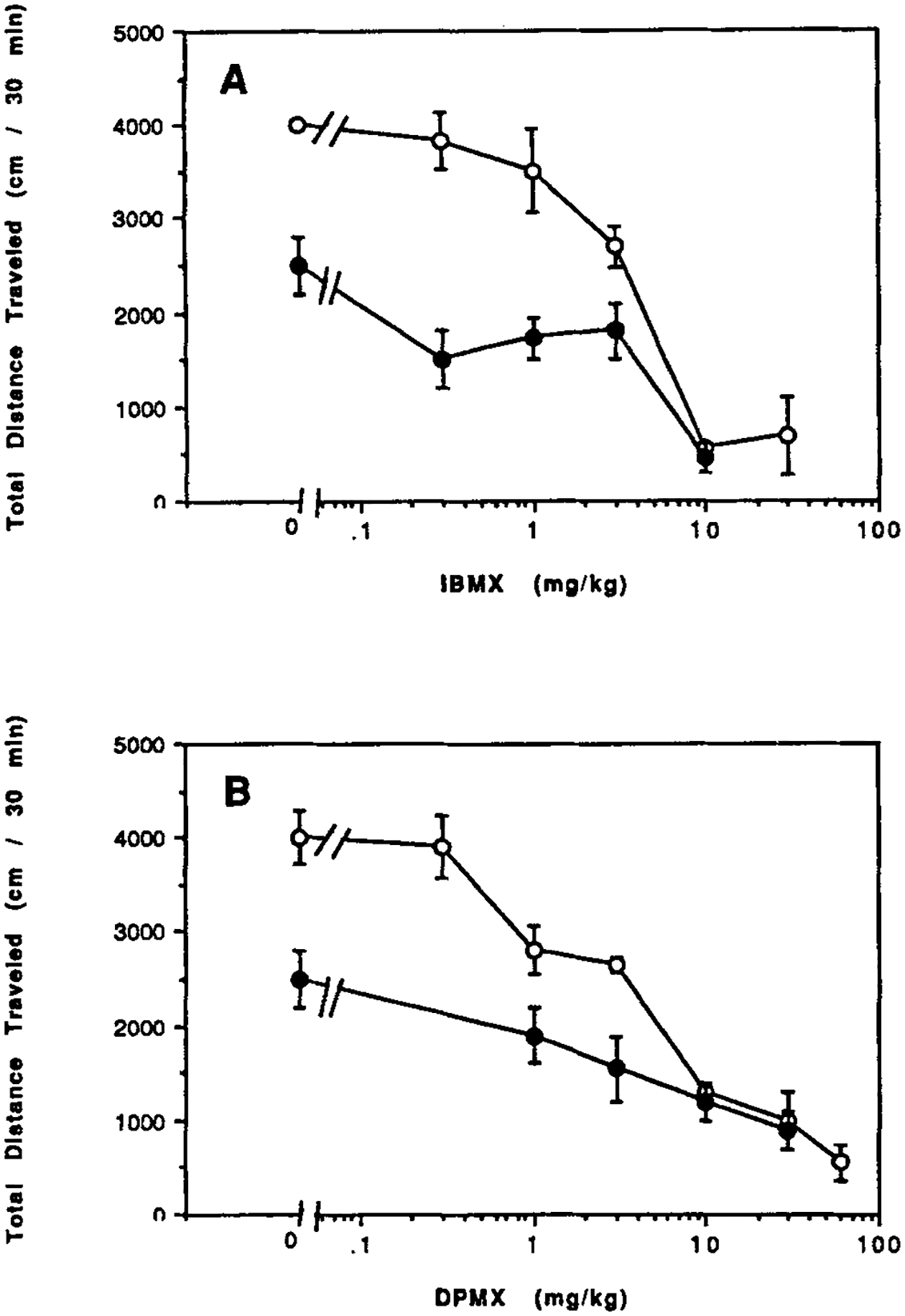

Two xanthines, namely 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) and 1,3-dipropyl-7-methylxanthine (DPMX), that are potent inhibitors of brain calcium-independent cyclic AMP phosphodiesterases [Choi et al., 1988] are behavioral depressants in control mice and CCI mice (Fig. 4A,B). The threshold for depressant effects of IBMX is lower in CCI mice (Fig. 4A). However, the ID50 values for IBMX were nearly the same, namely, 3.8 mg/kg in control mice and 4.0 mg/kg in CCI mice. Differences between effects in control and CCI mice for DPMX are relatively small (Fig. 4B). The ID50 values for DPMX were 2.3 mg/kg in control mice and 1.1 mg/kg in CCI mice. Rolipram, a highly selective inhibitor of brain calcium-independent phosphodiesterases [Wachtel, 1983], has similar depressant effects in control and CCI mice (data not shown). The ID50 values for rolipram were 0.36 mg/kg in control mice and 0.18 mg/kg in CCI mice.

Figure 4.

Dose response curves for locomotor effects of xanthine phosphodiesterase inhibitors: IBMX (A) and DPMX (B) were injected ip in control mice (open circles) and in mice after chronic caffeine ingestion (closed circles). Values are means ± s.e.m. (n = 6–12).

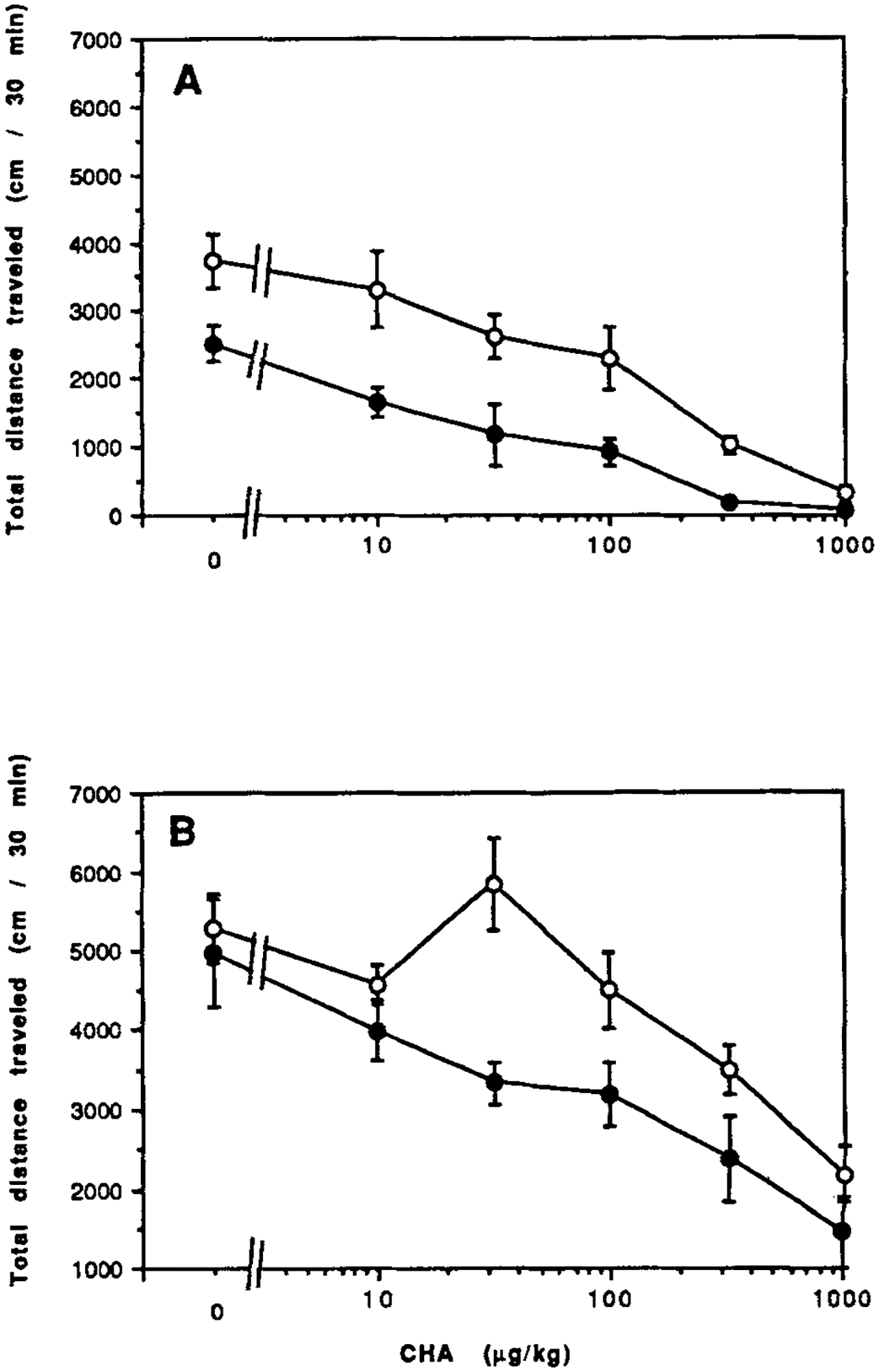

The dose response relationships of the A1-selective agonist N6-cyclohexyladenosine (CHA) are shown in Figure 5A for control and CCI mice. The ID50 of 30 μg/kg in CCI mice is lower than the ID50 of 120 μg/kg in control mice. The effects of CHA in combination with a stimulatory dose of caffeine is shown in Figure 5B. In the presence of caffeine, the dose response curve for CHA shows a stimulatory phase after an initial depressant phase in control mice, but not in CCI mice.

Figure 5.

Dose response curves for locomotor effects of the A1 agonist CHA in the absence (A) or in combination (B) with caffeine (10 mg/kg ip). Data are shown for control mice (open circles) and for mice after chronic caffeine ingestion (closed circles). Values are means ± s.e.m. (n = 6–10). The effect of CCI on the dose response curve (B) was shown to be statistically significant (ANOVA).

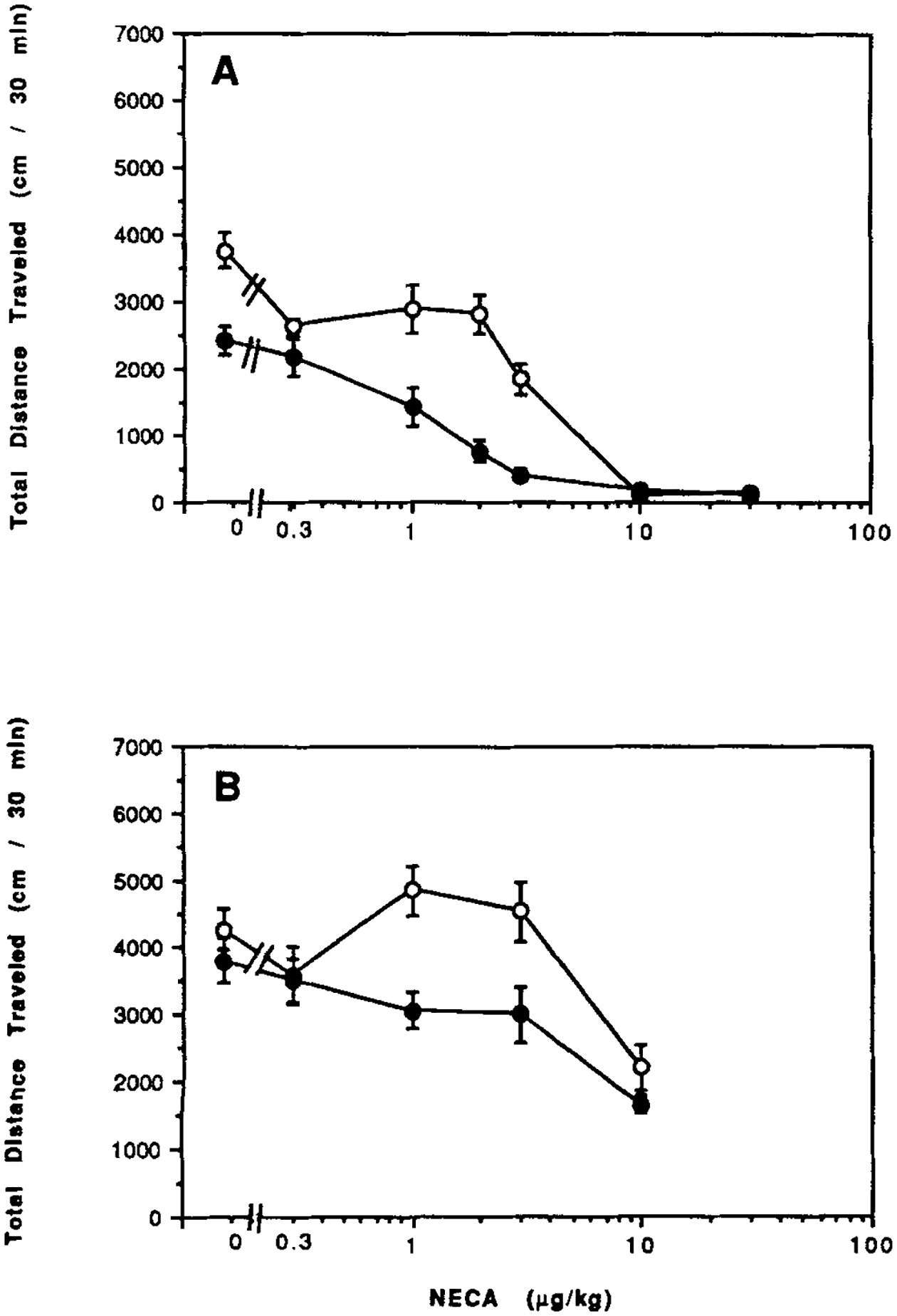

The dose response relationships for the mixed A1/A2 agonist 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) are shown in Figure 6A. The ID50 of 1.4 μg/kg NECA in CCI mice is somewhat lower than the ID50 of 3 μg/kg in control mice. The phasic aspect of the NECA curve is apparent in control mice, but not in the CCI mice. In combination with a stimulatory dose of caffeine, NECA at 1 μg/kg actually causes a stimulation of locomotor activity in control mice, but not in CCI mice (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Dose response curves for locomotor effects of the mixed A1/A2 agonist NECA in the absence (A) or in combination (B) with caffeine (5 mg/kg ip). Data are shown for control mice (open circles) and for mice after chronic caffeine ingestion (closed circles). Values are means ± s.e.m. (n = 6–12). The effect of CCI on the dose response curve (A) was shown to be statistically significant (ANOVA). At 3 μg/kg (A), P < 0.001 for CCI vs. water control (Bonferroni).

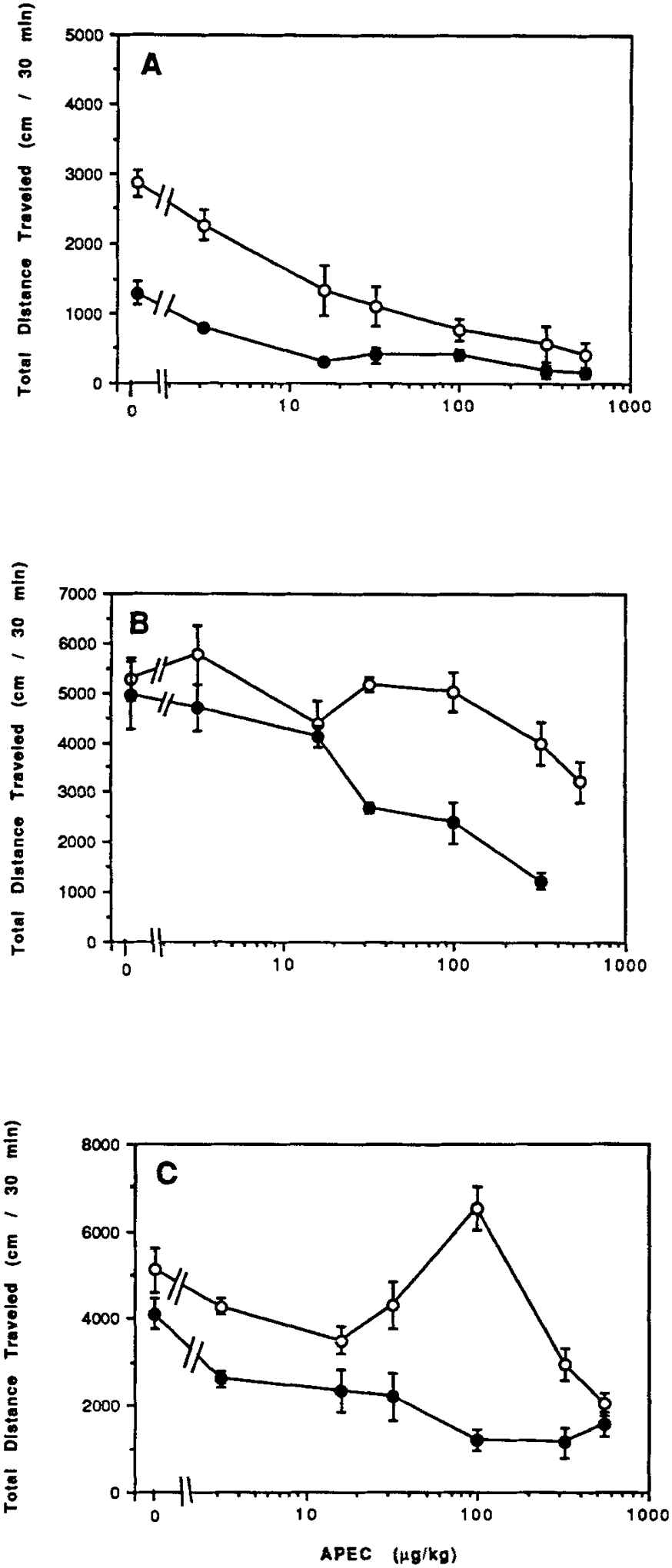

The dose-response relationships for the A2a-selective agonist APEC in the absence of a xanthine is shown in Figure 7A. The ID50 of 4 μg/kg in CCI mice is somewhat lower than the ID50 of 9 μg/kg APEC in control mice. In the presence of a stimulatory dose caffeine, APEC shows a different more flattened curve in control mice than in CCI mice (Fig. 7B). APEC shows stimulatory effects on locomotor activity after initial depressant effects in control mice when combined with a stimulant dose DMPX, while only depressant effects are seen in CCI mice (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Dose response curves for locomotor effects of the A2 adenosine agonist APEC in the absence (A) or in combination (B) with caffeine (10 mg/kg i.p.) or in combination (C) with DMPX (10 mg/kg i.p.). Data are shown for control mice (open circles) and for mice after chronic caffeine ingestion (closed circles). Values are means ± s.e.m. (n = 6–9). The effect of CCI on the dose response curve (B) was shown to be statistically significant (ANOVA). At 100 μg/kg, P = 0.01 for CCI vs. water control (Bonferroni).

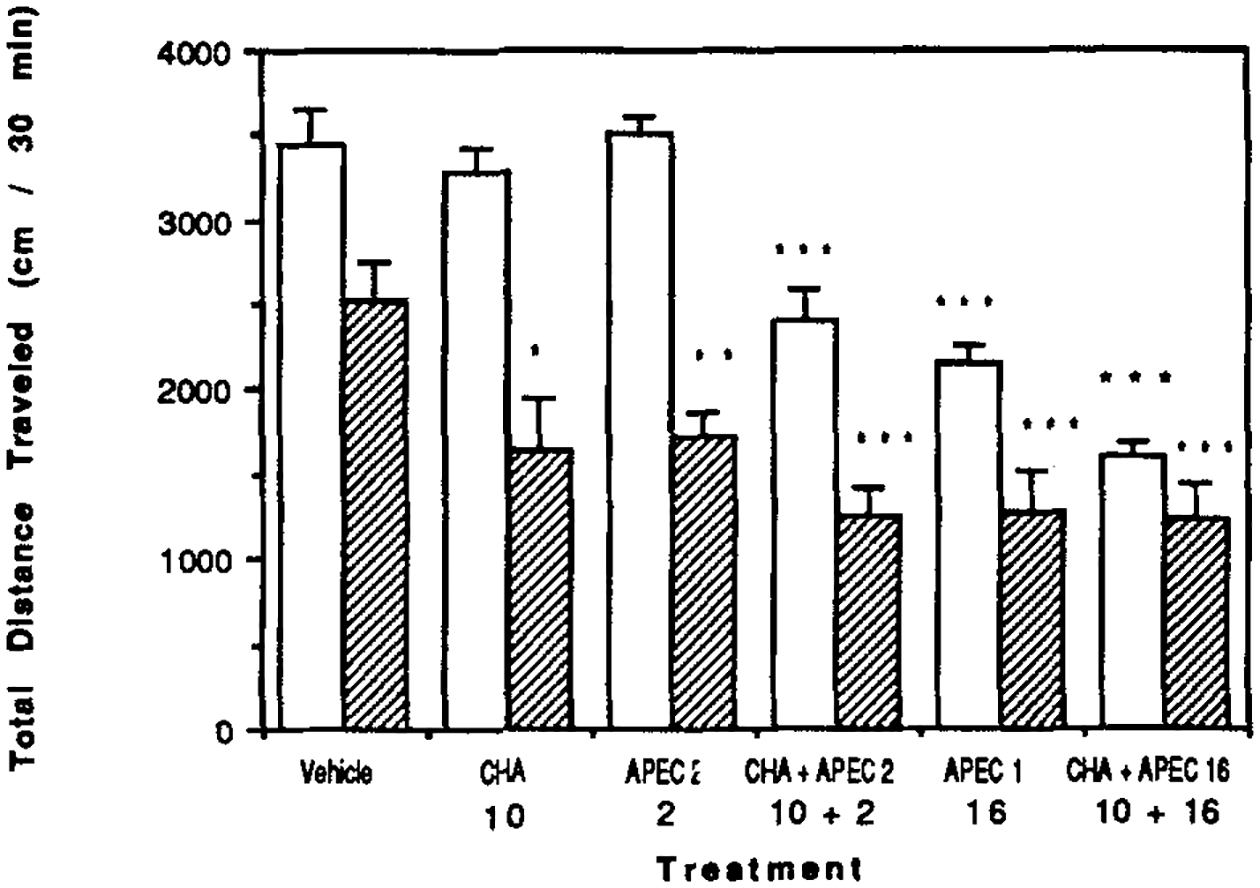

In control mice combinations of the A1-selective agonist CHA and the A2-selective agonist APEC have synergistic depressive effects on locomotor activity (Fig. 8) [see also Nikodijević et al., 1991]. Such synergisms are not present in CCI mice, or are masked by the greater efficacy of CHA and APEC in the CCI mice (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Locomotor effects of CHA and APEC in combination. Data is shown for control mice (open bars) and for mice after chronic caffeine ingestion (hatched bars). The dose of CHA was 10 μg/kg, while the doses of APEC were either 2 or 16 μg/kg as shown. Values are means ± s.e.m. (n = 6–33 for water control and n = 6–16 for CCI). Statistical differences (Student’s t-test) versus vehicle control: * P < 0.025; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Chronic effects of caffeine on responses to caffeine and other agents are well-documented but poorly understood [see review by Daly, 1993]. Tolerance to caffeine develops in rats [Holtzman, 1983; Holtzman et al., 1991] and Swiss Webster mice [Ahlijanian and Takemori, 1986], but not in male NIH Swiss mice [Nikodijević et al., 1991], the strain used in the present study. An increase in brain levels of central A1-adenosine receptors that occurs in rats and mice after chronic caffeine [Ahlijanian and Takemori, 1986; Fredholm, 1982; Ramkumar et al., 1988; Zielke and Zielke, 1987] suggests an up-regulation of adenosine-receptor functions. An increase in A1-adenosine receptors occurs under the present paradigm in cerebral cortex and striatum of NIH Swiss mice [Shi et al., 1993; and unpublished data]. This is consonant with an enhancement in the behavioral depressant effects of adenosine analogs in CCI mice (Figs. 5A, 6A, 7A) [see also Ahlijanian and Takemori, 1986]. An increase in adenosine-receptor function, however, is not consonant with the reduction in thresholds for stimulation by caffeine, CPT, and DMPX of locomotor activity in NIH Swiss strain mice following CCI (Fig. 1–3). Furthermore, not only the A1-selective agonist CHA and the mixed A1/A2 agonist NECA, but also the A2A-selective agonist APEC are more potent as behavioral depressants in CCI mice [Nikodijević et al., 1993] (Figs. 5A, 6A, 7A). There have been conflicting reports on effects of chronic treatment with a xanthine on A2A receptor levels, with one reporting no change in striatal levels after chronic theophylline [Lupica et al., 1991] and the other reporting an increase after chronic caffeine [Hawkins et al., 1988]. Our own studies in NIH Swiss strain mice with the present caffeine ingestion paradigm indicate no change in striatal levels of A2A receptors [Shi et al., 1993].

Depressant effects at high concentrations of caffeine have been proposed to reflect inhibition of a calcium-independent cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase [Choi et al., 1988]. Certainly, xanthines that are potent inhibitors of this isozyme are behavioral depressants, as is the non-xanthine rolipram, a selective inhibitor of this isozyme. The present study suggests no consistent change in the depressant effects for two such xanthines, namely IBMX and DPMX (Fig. 4AB).

A remarkable behavioral effect of combinations of caffeine or other xanthines, such as theophylline and IBMX, with an adenosine analog was reported in 1981 [Snyder et al., 1981]. In the presence of the xanthine, the adenosine analog now caused a further increase in locomotor activity. A rationale for this unusual reversal of the behavioral depressant effects of adenosine analogs has not been forthcoming [Coffin et al., 1984; Katims et al., 1983; Phyllis et al., 1986]. In the present study on A1, mixed A1/A2 and A2 agonists, the importance of dosage for observance of a stimulatory effect of adenosine analogs is obvious (Figs. 5B, 6B, 7C). Equally clear is the fact that for CHA, NECA, and APEC such behavioral stimulation is absent in CCI mice. On the basis of apparent multiphasic dose response relationships for behavioral effects of adenosine analogs in the presence of caffeine or DMPX or even IBMX, it appears likely that the behavioral output is the result of two or three interactive adenosine-receptor modulated systems. A prior study [Nikodijević et al., 1991] had revealed synergism between A1 and A2-receptor systems with respect to behavioral depression elicited by CHA and APEC. This was confirmed in the present study for control mice. But such synergism appears absent in CCI mice (Fig. 8). Thus, it is possible that the “rebound” stimulation of behavioral activity by adenosine analogs in control but not CCI mice, may be related to the absence of potentiative interactions of A1 and A2 receptor-modulated pathways in the CCI mice. CCI mice, however, also differ in an apparent increase in muscarinic function and in a loss of the depressant effects of nicotine [Nikodijević et al., 1993]. Thus, caffeine treatment appears to affect multiple pathways and delineation of the role of specific alterations on overall behavioral responses is proving difficult. The present study provides relevant data, in particular suggesting that chronic caffeine does not markedly affect the role of phosphodiesterases in regulation of locomotor activity, and that the enigmatic stimulatory effects of adenosine analogs on locomotor activity in the presence of methylxanthines is virtually lost after chronic ingestion of caffeine in male NIH Swiss strain mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research on caffeine has been supported in part by a series of grants from the International Life Science Institute. We thank Dr. Ian Paul for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- Ahlijanian MK, Takemori AE (1986): Cross-tolerance studies between caffeine and (−)-N6-(phenylisopropyl)adenosine (PIA) in mice. Life Sci 38:577–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgold J, Nikodijević O, Jacobson KA (1992): Penetration of adenosine antagonists into mouse brain as determined by ex vivo binding. Biochem Pharmacol 43:889–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi OH, Shamim MT, Padgett WL, Daily JW (1988): Caffeine and theophylline analogues: correlation of behavioral effects with activity as adenosine receptor antagonists and as phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Life Sci 43:387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin VL, Taylor JA, Phillis JW, Altman HJ, Barraco RA (1984): Behavioral interaction of adenosine and methylxanthines on central purinergic systems. Neuroscience Lett 47:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly JW (1993): Mechanisms of action of caffeine. In: Garattini S (ed): Caffeine, Coffee and Health. New York: Raven Press Ltd, pp 97–150. [Google Scholar]

- Daly JW, Padgett WL, Shamim MT (1986): Analogues of caffeine and theophylline: Effect of structural alterations on affinity of adenosine receptors. J Med Chem 29:1305–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB (1982): Adenosine actions and adenosine receptors after 1 week treatment with caffeine. Acta Physiol Scand 115:283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins M, Dugich M, Porter NM, Urancic M, Radulovacki M (1988): Effects of chronic administration of caffeine on adenosine A1 and A2 receptors in rat brain. Brain Res Bull 21:479–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman SG (1983): Complete, reversible, drug-specific tolerance to stimulation of locomotor activity by caffeine. Life Sci 33:779–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman SG, Mante S, Minneman KP (1991): Role of adenosine receptors in caffeine tolerance. J Pharmacol Exp Therap 256:62–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Barrington WW, Pannell LK, Jarvis MJ, Ji X-D, Hutchison AJ, Stiles GL (1989): Agonist-derived molecular probes for A2-adenosine receptors. J Mol Recognition 2:170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, van Galen PJM, Williams M (1992): Adenosine receptors: pharmacology, structure activity relationships and therapeutic potential. J Med Chem 35:407–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katims JJ, Annau Z, Snyder SH (1983): Interactions in the behavioral effects of methylxanthines and adenosine derivatives. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 227:167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupica CR, Jarvis MF, Berman RF (1991): Chronic theophylline treatment in vivo increases high affinity adenosine A1 receptor binding and sensitivity to exogenous adenosine in the in vitro hippocampal slice. Brain Res 542:355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehlig A, Daval J-L, Debry G (1992): Caffeine and the central nervous system: Mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects. Brain Res Rev 17:139–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikodijević O, Sarges R, Daly JW, Jacobson KA (1991): Behavioral effects of A1- and A2-selective adenosine agonists and antagonists: evidence for synergism and antagonism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 259:286–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikodijević O, Jacobson KA, Daly JW (1993): Locomotor activity in mice during chronic treatment with caffeine and withdrawal. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 44:199–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillis JW, Barraco RA, Delon RE, Washington DO (1986): Behavioral characteristics of centrally administered adenosine analogs. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 24:263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar V, Bumgarner JR, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL (1988): Multiple components of the A1 adenosine-adenylate cyclase system are regulated in rat cerebral cortex by chronic caffeine ingestion. J Clin Invest 82:242–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale TW, Abla KA, Shamim MT, Carney JM, Daly JW (1988): 3,7-Dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine: a potent and selective in vivo antagonist of adenosine analogs. Life Sci 43:1671–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi D, Nikodijević O, Jacobson KA, Daly JW (1993): Chronic caffeine alters the density of adenosine, adrenergic, cholinergic, GABA and serotonin receptors and calcium channels in mouse brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol 13:247–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SH, Katims JJ, Annau Z, Bruns RF, Daly JW (1981): Adenosine receptors and behavioral actions of methylxanthines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79:3260–3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukena D, Shamim MT, Padgett W, Daly JW (1986): Analogs of caffeine: Antagonists with selectivity for A2 adenosine receptors. Life Sci 39:743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel H (1983): Potential antidepressant activity of rolipram and other selective cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Neuropharmacology 22:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielke CL, Zielke HK (1987): Chronic exposure to subcutaneously implanted methylxanthines. Differential elevation of A1-adenosine receptors in mouse cerebellar and cerebral cortical membranes. Biochem Pharmacol 36:2533–2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]