Abstract

Study objective

Earlier intervention for opioid use disorder (OUD) may reduce long‐term health implications. Emergency departments (EDs) in the United States treat millions with OUD annually who may not seek care elsewhere. Our objectives were (1) to compare two screening measures for OUD characterization in the ED and (2) to determine the proportion of ED patients screening positive for OUD and those who endorse other substance use to guide future screening programs.

Methods

A cross‐sectional study of randomly selected adult patients presenting to three Midwestern US EDs were enrolled, with duplicate patients excluded. Surveys were administered via research assistant and documented on tablet devices. Demographics were self‐reported, and OUD positivity was assessed by the DSM 5 checklist and the WHO ASSIST 3.1. The primary outcome was the concordance between two screening measures for OUD. Our secondary outcome was the proportion of ED patients meeting OUD criteria and endorsed co‐occurring substance use disorder (SUD) criteria.

Results

We enrolled 1305 participants; median age of participants was 46 years (range 18–84), with 639 (49.0%) Non‐Hispanic, White, and 693 (53.1%) female. Current OUD positivity was identified in 17% (222 out of 1305) of the participants via either DSM‐5 (two or more criteria) or ASSIST (score of 4 or greater). We found moderate agreement between the measures (kappa = 0.56; Phi coefficient = 0.57). Of individuals screening positive for OUD, 182 (82%) endorsed criteria for co‐occurring SUD.

Conclusions

OUD is remarkably prevalent in ED populations, with one in six ED patients screening positive. We found a high prevalence of persons identified with OUD and co‐occurring SUD, with moderate agreement between measures. Developing and implementing clinically feasible OUD screening in the ED is essential to enable intervention.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Emergency departments (EDs) are the first healthcare point of contact for many with opioid use disorder (OUD). In the United States, the number of ED visits related to opioid use has more than tripled over the past decade, with complications such as overdose, withdrawal, and psychiatric decompensation driving a majority of visits. 1 , 2 Moreover, those with OUD are more likely to seek emergency care, and the number of ED visits increases with the severity and presence of mental health conditions. 3 , 4 , 5 The cost of all substance use disorders (SUDs) on healthcare is high, with annual expenditures in US hospitals reported at $13 billion; however, these costs are likely underestimated due to the constellation of adverse health outcomes related to OUD and the potential for undocumented OUD. 6 Despite the clinical burden that OUD and other SUDs have on emergency care, there are no standard guidelines for screening for these diseases in the ED setting.

1.2. Importance

Although the ED encounter is an opportunity to identify individuals with OUD and SUD, operational barriers such as time constraints, abundant screening questions in ED triage, and ED crowding may impede screening efforts. 7 Yet, patients with SUD may not access healthcare beyond sporadic emergency care visits; thus, the identification of SUD in the ED can play a role in the prevention and treatment response to the current epidemic. Efforts in identifying SUD in the ED leverage models such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment have been implemented; however, these methods require feasible screening methods to identify persons endorsing symptoms of OUD. 8 , 9 There is a critical need to identify and implement rigorous and practical screening methods for identifying individuals with OUD in the ED.

1.3. Goals of this investigation

The fundamental first step in determining the resources needed to implement a rigorous intervention program for OUD is to develop a clinically feasible and accurate measure to identify those with OUD. Previous reports of OUD in the ED have been limited by sampling methods and measures not validated in the ED. 9 We sought to randomly approach patients at three Midwestern US EDs and used two measures to identify OUD, allowing comparison of screening methods. We additionally sought to determine the prevalence of OUD among ED patients, as well as co‐occurring SUD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

This study involved cross‐sectional data collection of randomly approached patients during an ED encounter. Enrollment occurred at The Ohio State University academic health system and University of Cincinnati Medical Center encompassing three urban EDs in the Midwestern United States. Two EDs are academic level one trauma centers with approximately 70,000 visits per year. The third ED is an academic level three trauma center with about 40,000 visits annually. The Institutional Review Boards approved the use of these data for this study.

2.2. Selection of participants

ED beds at each site were randomized and research assistants then approached each randomized bed consecutively, allowing for a representative sample. 10 Patients were systematically approached following this randomization scheme for recruitment eligibility during their ED encounter between June 2020 and November 2021. All adult ED patients during recruitment hours who were not receiving active resuscitation efforts were considered for enrollment. Exclusion criteria were individuals less than 18 years of age, did not speak English, under police custody with guard in the room, were previously enrolled, physically restrained, or were not able to consent. Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection, and participants were informed the parent study was investigating the genetics of OUD.

2.3. Measurements

An in‐depth research assistant guided survey questionnaire was used to collect demographics and assess for criteria of OUD. A clinical psychologist trained the research assistants before study enrollment to increase fidelity of screening measures. Research assistants verbally administered the screening questions to the participants and entered the responses into tablet computers via REDCAP survey. 11 We used two measures to identify individuals meeting criteria for OUD. First, we asked participants whether they had used an opioid in the past 12 months, and then we inquired about nonmedical opioid use (i.e., had used opioids not prescribed to them and/or other than prescribed). 12 We used a survey checklist adapted from the 5th Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5) criteria, and individuals endorsing two or more criteria (yes/no) were categorized as OUD positive. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 A score of 2–3 criteria was classified as mild OUD, 4–5 moderate OUD, and 6 or greater criteria as severe OUD. 13 The second method of OUD identification was based on the World Health Organization's Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (WHO ASSIST) 3.1 criteria. 17 The WHO ASSIST is a long‐standing measure with subscales to detect nonmedical use of opioids (including prescription) as well as tobacco, nicotine (vaping), cannabis (including vaping), alcohol, cocaine, amphetamines, inhalants, sedatives, and hallucinogens. Participants were classified as OUD positive if they scored 4 or greater on the opioid subsections. 17 , 18 , 19 Individuals who scored 4–26 were categorized as moderate risk (11–26 for alcohol) and 27 or greater as high risk, and classified as meeting the criteria for SUD for that substance.

The Bottom Line

Screening for opioid use disorder (OUD) is important in the emergency department (ED). This cross‐sectional study of 1305 patients at three urban EDs tested two OUD screening methods: DSM‐5 and ASSIST. The study identified OUD in one out of six patients, with moderate agreement between the two tools. These findings shine light on the high prevalence of OUD in the ED and the utility of different screening tools.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was the agreement between two screening measures to determine indications of OUD positivity based on self‐reported criteria (DSM 5 checklist versus ASSIST 3.1). The secondary outcomes include characterizing the proportion of ED patients reporting OUD criteria via either measure, which also endorse criteria for co‐occurring SUD based on the WHO ASSIST 3.1 criteria.

2.5. Analysis

We used descriptive analysis to detail the population demographic characteristics and OUD positivity with both instruments, as well as those endorsing criteria for SUD. If an individual did not respond, this was classified as a negative for those criteria. If a participant scored on both the ASSIST opioid and RX opioid subsections, the higher score was used. To determine the magnitude of agreement, kappa and phi coefficients were calculated for concordance of positive screen (yes/no) between the DSM‐5 criteria and ASSIST screening methods for OUD positivity. Additionally, we detailed the frequency of individual positive responses for each measure, examining patterns of severity of opioid use identified with each measure (Supplemental Table). Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 29. 20

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of study subjects

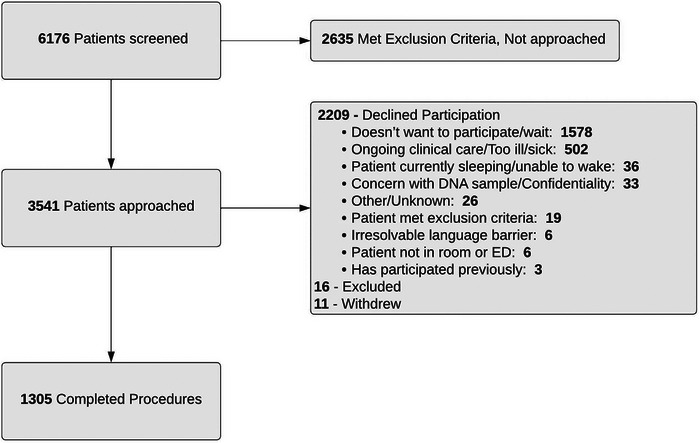

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics and co‐occurring substance use among the full sample, stratified by OUD positivity. Between June 2020 and November 2021, 3541 ED patients were approached for enrollment (Figure 1). Of the 1305 unique participants enrolled in the study sample, 49.0% were White, Non‐Hispanic and 46.1% were Black/African American, 53.1% were female, mean age was 46 years, and 222 (17.0%) were categorized as OUD positive via one of the two screening methods.

TABLE 1.

Self‐reported characteristics of study sample.

| Total cases | OUD positive a | Not OUD positive a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1305 | (%) | N = 222 | (17.0%) | N = 1083 | (83.0%) | |

| Age—years, mean (range) | 46 | (18–84) | 44.8 | (20–70) | 46.3 | (18–84) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 | (0.1) | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.1) |

| Asian | 8 | (0.6) | 0 | (0) | 8 | (0.7) |

| Biracial/multiracial | 32 | (2.5) | 3 | (1.4) | 29 | (2.3) |

| Black/African American | 602 | (46.1) | 77 | (34.7) | 525 | (48.5) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 36 | (2.8) | 4 | (1.8) | 33 | (3.0) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 3 | (0.2) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (0.3) |

| White, non‐Hispanic | 639 | (49.0) | 138 | (62.2) | 501 | (46.3) |

| Other | 19 | (1.5) | 3 | (1.4) | 16 | (1.5) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 693 | (53.1) | 109 | (49.1) | 584 | (53.9) |

| Male | 604 | (46.3) | 112 | (50.5) | 492 | (45.3) |

| Non‐Cis | 8 | (0.6) | 1 | (0.5) | 7 | (0.6) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 287 | (22.0) | 47 | (21.2) | 240 | (22.2) |

| Divorced/separated | 131 | (10.0) | 22 | (9.9) | 109 | (10.1) |

| Widowed | 66 | (5.1) | 14 | (6.3) | 52 | (4.8) |

| Never married/not reported | 821 | (62.9) | 139 | (62.6) | 682 | (63.0) |

| Education | ||||||

| No high school diploma | 201 | (15.4) | 40 | (18.0) | 161 | (14.9) |

| High school diploma, GED equivalent | 431 | (33.0) | 73 | (32.9) | 358 | (33.1) |

| Some college | 384 | (29.4) | 72 | (32.4) | 312 | (28.8) |

| College graduate | 201 | (15.4) | 29 | (13.1) | 172 | (15.9) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 82 | (6.3) | 7 | (3.2) | 75 | (6.9) |

| Unknown | 6 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.5) | 5 | (0.5) |

| History of any injection drug use via ASSIST | ||||||

| Current injection drug use | 35 | (2.7) | 32 | (14.4) | 3 | (0.3) |

| Previous history of injection drug use | 77 | (5.9) | 32 | (14.4) | 45 | (4.2) |

| Not answered | 5 | (0.4) | 2 | (0.9) | 3 | (0.3) |

| Criteria for SUD via ASSIST | ||||||

| Alcohol | 193 | (14.8) | 45 | (10.3) | 148 | (13.6) |

| Amphetamines | 42 | (3.2) | 28 | (1.9) | 14 | (1.3) |

| Cannabis | 413 | (31.6) | 96 | (21.7) | 317 | (29.3) |

| Cocaine | 89 | (6.8) | 44 | (2.4) | 45 | (4.2) |

| Hallucinogens | 13 | (1.0) | 7 | (3.2) | 6 | (0.5) |

| Sedatives | 55 | (4.2) | 28 | (3.2) | 27 | (2.5) |

| Tobacco | 597 | (45.7) | 150 | (67.6) | 447 | (41.3) |

| Vaping nicotine | 96 | (7.4) | 31 | (14.0) | 65 | (6.0) |

| Vaping cannabis | 99 | (7.6) | 29 | (13.1) | 70 | (6.5) |

| Any substance b | 842 | (64.5) | 182 b | (82.0) | 620 b | (57.2) |

Note: Current injection drug use is defined as injection use within the last 3 months. History of is defined as any injection use outside of the last 3 months.

OUD positive defined as scoring positive on either the DSM criteria (2 or greater) or the ASSIST criteria (4 or greater) for opioids OR prescription opioids.

Any substance use positive defined as scoring positive (4 or more) on the ASSIST criteria for any substance, or 11 or more for alcohol use. Abbreviations: OUD, opioid use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder.

FIGURE 1.

Screening, enrollment, and reasons for declined participation flow diagram. *Excluded cases included later met exclusion criteria or barriers due to clinical care.

3.2. Concordance between DSM‐5 and ASSIST

Of the entire cohort, current OUD positivity was identified in 189 (14.5%) via the DSM‐5 criteria checklist and in 131 (10.0%) via the ASSIST (Table 2). There was moderate agreement between the two screener's identification of persons meeting criteria for OUD (kappa = 0.56, p < 0.001; Phi coefficient = 0.57, p < 0.001). 21 We detailed the level of severity of opioid use identified in both screeners (Table 3). Additionally, we found there was a high number of individuals (94, 29.1%) who did not answer two of the ASSIST questions: (1) “During the past three months, how often has your use of [opioids] led to health, social, legal or financial problems?” and (2) “During the past three months, how often have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of your use of [opioids]?”

TABLE 2.

Persons screening positive for current at‐risk opioid use.

| DSM‐5 criteria checklist a | WHO ASSIST 3.1 a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 189 | (%) | N = 131 | (%) | |

| Age—years, mean (range) | 43.5 | (20–68) | 45.1 | (18–84) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.8) |

| Asian | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| Biracial/multiracial | 2 | (1.1) | 3 | (2.3) |

| Black/African American | 61 | (32.3) | 43 | (32.8) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 | (2.1) | 2 | (1.5) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| White, non‐Hispanic | 122 | (64.6) | 84 | (64.1) |

| Other | 3 | (1.6) | 0 | (0) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 90 | (47.6) | 58 | (44.3) |

| Male | 98 | (51.9) | 73 | (55.7) |

| Non‐Cis | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 38 | (20.1) | 19 | (14.5) |

| Divorced/separated | 20 | (10.6) | 13 | (9.9) |

| Widowed | 10 | (5.3) | 13 | (9.9) |

| Single/not reported | 120 | (63.5) | 86 | (65.6) |

OUD positive defined as scoring either 2 or more on the DSM criteria or 4 or more on the ASSIST criteria for opioids/prescription opioids.

TABLE 3.

Crosstab for DSM‐5 criteria and ASSIST positivit.

| ASSIST Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Moderate | High | Total | ||

| DSM‐5 criteria | Negative | 1083 | 33 | 0 | 1116 |

| Mild | 62 | 9 | 0 | 71 | |

| Moderate | 15 | 9 | 0 | 24 | |

| Severe | 14 | 46 | 34 | 94 | |

| Total | 1174 | 97 | 34 | 1305 |

Note: Positive on DSM‐5 criteria corresponds to a score of 2 or greater. Mild is 2–3, moderate is 4–5, and severe is 6+ criteria. ASSIST positivity corresponds to score of 4 or greater on street and/or prescription opioid use questions. Score is 0–3 low (negative) risk, 4–26 moderate risk, 26+ high risk.

3.3. Other substance use

The majority of the cohort (842, 64.5%) met criteria for mild or moderate risk use of any substance, with 193 (14.8%) meeting SUD criteria for alcohol, 597 (45.7%) for tobacco, and 620 (57.2%) with nonopioid SUD. Of the entire cohort, 112 (8.6%) had history of injection drug use (Table 1). Of the persons categorized as OUD positive via either instrument, 182 (82%) reported current at‐risk use of other substances in addition to opioids, with 10.3% also using alcohol and 3.2% reporting sedative use.

4. LIMITATIONS

This report should be taken into context with others identifying the magnitude and severity of opioid and co‐occurring substance use in the ED patient population. Although this study is not without limitations, significant strengths of our work reflect the randomized sampling strategy when approaching ED patients for enrollment. The identification of opioid use and substance use is limited to the respect that substance use was collected self‐report via research assistant guided interview, and there were many questions that may have introduced survey burden to the participants. Additionally, as this was a secondary analysis of a study related to genetic risk factors for OUD, participants may have had reluctance to participate.

5. DISCUSSION

An important step in addressing the opioid overdose crisis is to identify and characterize the extent of the problem. This study found a high number of individuals screening positive for OUD and co‐occurring substance use across three urban EDs. Our results confirm that opioid and other substance use is exceedingly common, and our analysis found differences in the positivity rate of OUD in our sample. These results suggest further need to identify adequate screening methods to identify problematic opioid use in ED patient populations.

Although both screening methods detected a substantial number of individuals with at‐risk opioid use, each screening method also identified persons who were missed by the other. The greater proportion of individuals identified by the DSM‐5 criteria for OUD (14.5%) compared with the ASSIST (10.0%) may be the result of survey fatigue as the ASSIST instrument followed the DSM‐5. However, differences in positivity for OUD in the ASSIST may have also been due to high nonresponse rates for two of the ASSIST questions (“During the past three months, how often has your use of [opioids/RX opioids] led to health, social, legal or financial problems?”; “During the past three months, how often have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of your use of [opioids/RX opioids],”) and the separate subsections for illicit opioids and prescription opioids.

The DSM‐5 criteria checklist was found to be easier to score (yes/no) than the ASSIST screener. Additionally, the DSM‐5 criteria checklist identified a higher number of individuals with a positive screen for potential OUD. The WHO ASSIST took longer for participants to complete; however, it is able to identify substance use other than opioids. When considering screening measures to implement in the ED, the intended application of the screener should be considered. If a quick and simple screener to identify potential patients for either additional OUD screening and/or treatment services are needed, the DSM‐5 criteria checklist may be advantageous. However, if an ED is interested in assessing substance use in addition to opioids, or if the severity of at‐risk use is necessary, the WHO ASSIST would be more appropriate.

We found a large number of individuals who screened positive for OUD as well as other substance use. Our prevalence is higher than most national studies in EDs, ranging from 6.5 to 9%. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 Although we were able to benefit from the application of two screening methods, these findings should be of concern nationally as unidentified opioid and other substance use may be much higher than anticipated. Although this population may be at greater risk due to enrollment in urban academic ED settings, we would anticipate the actual number to be negatively biased due to the social stigma of self‐report of opioids and other substance use.

The identification of at‐risk opioid use and substance use is crucial to identify persons who could benefit from the introduction of secondary prevention interventions (eg, harm reduction, medications for OUD). There are promising interventions for screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment; however, feasible and effective methods to accurately detect and document at‐risk opioid and occurring substance use are urgently needed in order to target prevention and harm reduction interventions adequately.

Supporting information

Biography

Brittany E. Punches, PhD, RN, is an Associate Professor in the College of Nursing and Department of Emergency Medicine at The Ohio State University. Dr. Punches’ clinical and scientific training focuses on applying health service research to develop and test emergency care prevention interventions to address population health. Her primary focus surrounds disparities in pain management, substance use, and trauma recovery.

Punches BE, Freiermuth CE, Sprague JE, et al. Screening for problematic opioid use in the emergency department: Comparison of two screening measures. JACEP Open. 2024;5:e13106. 10.1002/emp2.13106

Supervising Editor: Christian Tomaszewski, MD, MS

Funding and support: By JACEP Open policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

REFERENCES

- 1. Suen LW, Davy‐Mendez T, LeSaint KT, Riley ED, Coffin PO. Emergency department visits and trends related to cocaine, psychostimulants, and opioids in the United States, 2008–2018. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lovegrove MC, Dowell D, Geller AI, et al. US emergency department visits for acute harms from prescription opioid use, 2016–2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(5):784‐791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewer D, Freer J, King E, et al. Frequency of health‐care utilization by adults who use illicit drugs: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Addiction. 2020;115(6):1011‐1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. John WS, Wu LT. Sex differences in the prevalence and correlates of emergency department utilization among adults with prescription opioid use disorder. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(7):1178‐1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi S, Biello KB, Bazzi AR, Drainoni ML. Age differences in emergency department utilization and repeat visits among patients with opioid use disorder at an urban safety‐net hospital: a focus on young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;200:14‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Luo F. Assessment of annual cost of substance use disorder in US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210242‐e210242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson KD, Punches BE, Smith CR. Perceptions of the essential components of triage: a qualitative analysis. J Emerg Nurs. 2021;47(1):192‐197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Monico LB, Oros M, Smith S, Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, Schwartz R. One million screened: scaling up SBIRT and buprenorphine treatment in hospital emergency departments across Maryland. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1466‐1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Punches BE, Ali AA, Brown JL, Freiermuth CE, Clark AK, Lyons MS. Opioid‐related risk screening measures for the emergency care setting. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2021;43(4):331‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Merchant RC, Clark MA, Seage GR III, Mayer KH, Degruttola VG, Becker BM. Emergency department patient perceptions and preferences on opt‐in rapid HIV screening program components. AIDS Care. 2009;21(4):490‐500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patridge EF, Bardyn TP. Research electronic data capture (REDCap). J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(1):142. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beauchamp GA, Nelson LS, Perrone J, Lyons MS. A theoretical framework and nomenclature to characterize the iatrogenic contribution of therapeutic opioid exposure to opioid induced hyperalgesia, physical dependence, and opioid use disorder. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46(6):671‐683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Vol 21. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association ; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14. D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department–initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636‐1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coupet E, D'Onofrio G, Chawarski M, et al. Emergency department patients with untreated opioid use disorder: a comparison of those seeking versus not seeking referral to substance use treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;219:108428. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. D'Onofrio G, Edelman EJ, Hawk KF, et al. Implementation facilitation to promote emergency department–initiated buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e235439. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.5439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Humeniuk R, Henry‐Edwards S, Ali R, Poznyak V, Monteiro MG, Organization WH, The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): manual for use in primary care. Published online 2010.

- 18. Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST). Addiction. 2008;103(6):1039‐1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Group WAW. The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1183‐1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. IBM Corp. Released 2023. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp

- 21. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. biometrics. 1977:159‐174. Published online. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singleton J, Li C, Akpunonu PD, Abner EL, Kucharska‐Newton AM. Using natural language processing to identify opioid use disorder in electronic health record data. Int J Med Inf. 2023;170:104963. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Punches BE, Ancona RM, Freiermuth CE, Brown JL, Lyons MS. Incidence of opioid use disorder in the year after discharge from an emergency department encounter. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(3):e12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beaudoin FL, Baird J, Liu T, Merchant RC. Sex differences in substance use among adult emergency department patients: prevalence, severity, and need for intervention. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(11):1307‐1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whiteside LK, Cunningham RM, Bonar EE, Blow F, Ehrlich P, Walton MA. Nonmedical prescription stimulant use among youth in the emergency department: prevalence, severity and correlates. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):21‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.